1. Introduction

Human papillomavirus (HPV) is a small, double-stranded DNA virus that infects basal epithelial cells and is the primary etiologic agent in cervical cancer and other anogenital and oropharyngeal malignancies [1,2]. Globally, cervical cancer remains the fourth most common cancer in women with approximately 604,000 new cases and 342,000 deaths reported in 2020 [3]. High-risk HPV genotypes—particularly HPV16 and HPV18—account for over 70% of cervical cancer cases and are known to drive oncogenesis through integration into the host genome and persistent expression of the viral oncoproteins E6 and E7 [4,5,6]. These viral proteins promote malignant transformation by inactivating the tumor suppressors p53 and retinoblastoma protein (pRb), leading to uncontrolled proliferation, genomic instability, and immune evasion [7,8].

Persistent infection with high-risk HPV and viral genome integration are key steps in cancer development. [9]. Epidemiological data suggest that more than 80% of sexually active individuals acquire HPV at some point during their lifetime; although the majority of infections are transient and resolve spontaneously, a subset of high-risk infections progress to high-grade intraepithelial neoplasia and invasive cancer if left untreated [10].

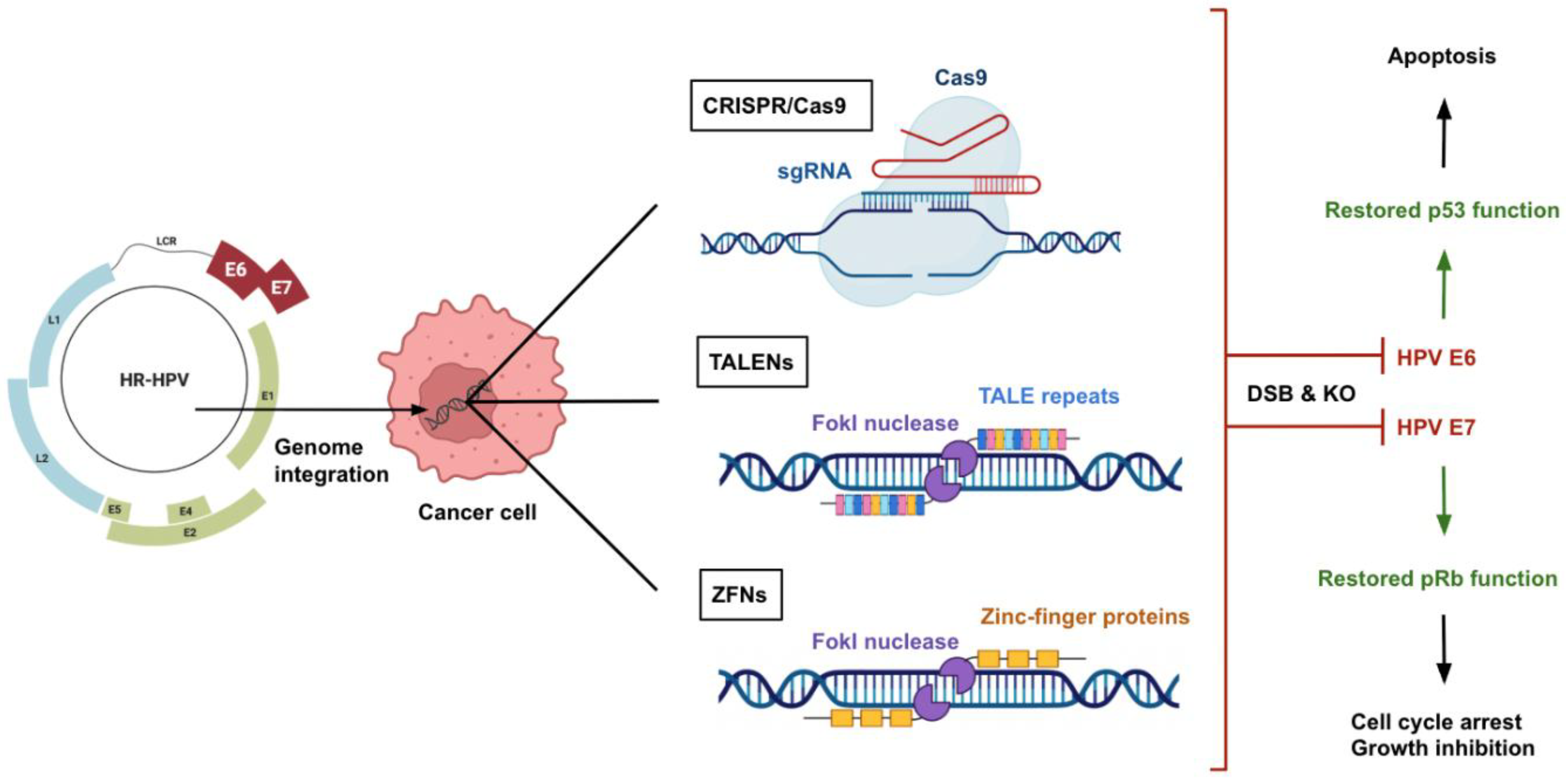

While prophylactic HPV vaccines (e.g., Gardasil and Cervarix) have shown high efficacy in preventing new HPV infections, they offer no benefit to individuals already infected or those with established HPV-related lesions [11,12]. Similarly, cervical screening and surgical excision of high-grade lesions have reduced cancer incidence in high-income regions, yet they fail to eliminate persistent HPV infection and are less accessible in low-resource settings, where the burden of disease remains disproportionately high [13,14]. For individuals with persistent HPV infection or low-grade lesions, current management often involves a dilemma between overtreatment and the psychological burden of surveillance [15]. Thus, novel therapeutic strategies that directly eliminate HPV from infected or transformed cells are urgently needed. Genome editing technologies including CRISPR/Cas9, transcription activator-like effector nucleases (TALENs), and zinc-finger nucleases (ZFNs) have emerged as promising tools to disable HPV oncogenes or excise viral DNA [16,17,18]. These systems enable targeted DNA cleavage and repair, offering a potential molecular cure for HPV-associated diseases. Recent preclinical studies have demonstrated the feasibility of targeting HPV DNA or oncogenes with genome editing tools in cell culture and animal models [19,20,21]. As such, genome editing represents a transformative approach that may complement or surpass traditional treatments by eradicating the root molecular drivers of HPV-mediated carcinogenesis. This review examines the current landscape of genome editing technologies applied to HPV-related cancers, emphasizing their mechanisms, therapeutic applications, preclinical and clinical progress, and the challenges to translation into routine oncology practice.

2. Genome Editing Technologies

Modern genome editing relies on programmable nucleases that create targeted DNA double-strand breaks (DSBs), triggering cellular DNA repair processes that can introduce mutations or integrate new DNA [21,22,23]. The three primary platforms are zinc-finger nucleases (ZFNs), transcription activator-like effector nucleases (TALENs), and CRISPR-Cas9 (clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats-associated nuclease). All three systems ultimately achieve gene editing via the same mechanism – DSB induction and the cell’s subsequent repair by non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) or homology-directed repair (HDR) but they differ in how they recognize DNA targets and, in their practicality, and precision.

2.1. CRISPR/Cas9

The CRISPR/Cas9 system, adapted from a bacterial adaptive immune mechanism, has revolutionized genome editing with its simplicity and efficiency [24]. In CRISPR/Cas9, a programmable single-guide RNA directs the Cas9 endonuclease to a complementary DNA sequence, where Cas9 introduces a DSB. Designing a CRISPR experiment is as straightforward as changing the 20-nucleotide guide sequence in the sgRNA, in contrast to the protein engineering required for ZFNs and TALENs. This RNA-guided flexibility makes CRISPR extremely versatile and fast for testing many targets [25]. CRISPR can also deliver multiple sgRNAs to target several sites simultaneously, which is useful for knocking out both E6 and E7 oncogenes together or multiple viral genome sites in one go [26].

CRISPR’s main advantages are its ease of design, high efficiency, and scalability. Thousands of guides can be cheaply synthesized and tested, enabling large genetic screens or personalized target adaptation. In HPV research, the ability to quickly craft sgRNAs for different HPV genotypes (e.g. HPV16 vs HPV18) means therapies can be tailored to the patient’s specific virus [27]. Several studies have reported that wild-type Cas9 can induce indels in the majority of target HPV DNA sequences in a cell population [28]. Moreover, CRISPR has been leveraged to reactivate silenced tumor suppressor pathways in HPV-positive cancer cells – for example, by knocking out E6, thereby freeing p53, or knocking out E7 to restore pRB function [29]. Another advantage in the HPV context is that CRISPR can target integrated viral DNA within the host genome, something conventional antivirals or RNA interference cannot permanently do [30].

The major concern for CRISPR/Cas9 is off-target activity, where the Cas9-sgRNA complex cuts at unintended genomic sites that resemble the target sequence. Off-target mutations could potentially inactivate other genes or cause genomic instability – a significant safety issue for any therapeutic application. However, off-target profiles can be improved by using high-fidelity Cas9 variants and by careful guide sequence design using bioinformatic tools. Indeed, bioinformatic improvements have largely mitigated off-target risks by enabling the selection of highly specific sgRNAs and by providing methods to empirically detect off-target cuts (e.g. GUIDE-seq) [31,32]. Another limitation is delivery. the SpCas9 protein (≈160 kDa) plus its sgRNA (≈100 nt) are large in size, making it challenging to package into some vectors (for instance, the popular AAV vectors have a ~4.7 kb cargo limit, which just accommodates Cas9 and a short sgRNA). Various studies explored smaller Cas9 orthologs (like SaCas9) or transient mRNA/protein delivery to address this [33,34]. There is also the possibility of immune responses against Cas9, since it is a foreign bacterial protein; antibodies to Cas9 have been detected in humans, presumably from prior exposure to Cas9-bearing bacteria, but strategies like transient local delivery or using human-compatible delivery vehicles aim to minimize this risk [35]. Overall, CRISPR/Cas9 has proven to be a game-changing tool, combining relative precision with unparalleled programmability, which is why it has become the preferred genome editing method in recent HPV research and therapeutic development.

2.1. TALENs

TALENs were one of the first “user-friendly” genome editing systems, developed shortly before CRISPR. A TALEN is composed of a DNA-binding domain built from TALE repeats (derived from plant pathogen transcription activator-like effectors) fused to the FokI nuclease domain. Each TALE repeat is a 33–35 amino acid module that recognizes one base pair via two hypervariable residues (repeat-variable diresidues, RVDs). By assembling ~15–20 repeats with appropriate RVDs, one can target a specific ~15–20 bp sequence. Two TALENs are designed to bind opposite strands with a spacer in between; when both bind, the FokI halves dimerize and create a DSB. This one-to-one code of RVDs to DNA bases made TALEN design more straightforward than ZFNs [37].

TALENs generally offer very high targeting specificity. Because each TALE repeat recognizes a single nucleotide, a properly assembled TALEN pair can discriminate even single-base changes. There is no requirement for a PAM sequence, so TALENs have broad targetable range across the genome (useful if an ideal CRISPR site is lacking). In early comparisons, TALENs showed better specificity and equal or greater efficiency than first-generation ZFNs [38]. In the HPV context, TALENs can be engineered to target conserved regions of HPV genomes; for example, TALENs targeting HPV16 E7 have been created and shown to cut the viral DNA and kill HPV-positive cells [39]. An important in vivo advantage is that TALENs, being proteins, can be delivered as mRNA or protein which acts transiently, potentially reducing off-target exposure compared to a continuously expressed CRISPR plasmid [40] One preclinical study demonstrated that intravaginal delivery of HPV-targeted TALEN plasmids in a transgenic mouse model of cervical neoplasia led to regional gene editing and therapeutic effect, highlighting feasibility of local TALEN application for HPV lesions [41].

The practicality of TALENs is hampered by the labor-intensive protein engineering required. Although modular, assembling numerous repeats (each ~100 bp of DNA code) into a plasmid is non-trivial, especially since the repeats are highly similar and prone to recombination during cloning. Methods like Golden Gate assembly have simplified this, but it remains more complex than designing a new sgRNA for CRISPR [42]. The large size of TALEN genes (each TALEN is >3 kb) means delivering a TALEN pair (≈6 kb total) often requires viral vectors with large cargo capacities or non-viral methods [42]. Off-target effects for TALENs are typically lower than early CRISPR or ZFN systems, but can occur, particularly if there are multiple similar sequences (due to TALEN’s tolerance for one or two mismatches) [43]. Interestingly, increasing TALEN DNA-binding affinity (for instance, using TALEN variants with different N-terminal domains or RVDs to boost binding) can increase off-target cutting as one study showed. Thus, there is a trade-off between TALEN activity and specificity, and careful design is needed [44]. In summary, TALENs are a powerful tool with proven efficacy in HPV gene targeting, but their use has been somewhat eclipsed by CRISPR’s ease of use. They may still hold niche value, especially where CRISPR off-target concerns, or PAM site absences make a protein-based approach advantageous.

2.1. ZFNs

Zinc-finger nucleases were the first widely adopted engineered nucleases, consisting of a DNA-binding domain made of C2H2 zinc-finger modules linked to a FokI nuclease domain. Each zinc-finger protein (ZFP) module typically recognizes a 3–4 bp DNA se-quence; by concatenating 3–6 fingers, ZFNs can be designed to bind ~9–18 bp per monomer. [45]. Like TALENs, ZFNs function as dimers that cut when two FokI domains dimerize on adjacent target sites [46]. Custom ZFN design is complex: the DNA recognition of each finger can be influenced by its neighbors, and engineering a new ZFN often required expert or selection-based methods to identify fingers that bind the desired sequence with high fidelity [47]. Despite these challenges, ZFNs paved the way for clinical gene editing – for example, a ZFN therapy to disrupt the CCR5 gene in T-cells was the first gene-editing approach tested in humans (for HIV infection) and showed safety and some efficacy [48].

ZFNs are smaller in gene size than TALENs or Cas9, which is useful for delivery constraints. A pair of ZFNs can often fit into a single AAV vector (since each ZFN is roughly 1 kb, compared to a ~4 kb Cas9) [49]. Early-generation ZFNs, once successfully engineered, achieved effective genome editing and helped establish proof-of-concept for therapeutic gene editing. In theory, ZFNs can target any sequence (no PAM needed), though in practice engineering challenges made some sequences inaccessible. For HPV, ZFNs were less commonly reported than CRISPR/TALENs, but researchers have at-tempted to create ZFNs against HPV oncogenes [50]. One study designed ZFNs targeting HPV16/18 E7, demonstrating cleavage of the viral gene in cervical cancer cells. In combination with other therapies, such ZFNs showed potential to suppress HPV+ tumor cell growth [51].

The primary drawback of ZFNs is the difficulty and cost of custom design for new targets. Unlike TALENs (with a simpler one-repeat-per-base code) or CRISPR (guide RNA), ZFN engineering often required extensive protein optimization [52,53]. Off-target effects were a notable problem with some ZFNs; a comparative analysis using GUIDE-seq found that certain ZFNs generated hundreds of off-target cleavages throughout the genome. Interestingly, that study noted the off-target frequency of ZFNs correlated with certain amino acid compositions of the zinc-finger array (for instance, more “G” residues in the finger–DNA interface led to more off-target cuts). TALENs and CRISPR in the same comparison showed far fewer off-target events (on the order of 0–7 off-target sites) than ZFNs which in one case had ~1856 off-target sites [50]. This indicates that while ZFNs can be made very specific, some designs are quite error-prone, underscoring the need for thorough validation. In HPV research, ZFNs have taken a backseat due to these challenges. As more user-friendly tools emerged, new work on HPV tends to favor CRISPR or TALEN. Nonetheless, historical ZFN studies proved that targeting HPV genes could yield anti-tumor effects, and they provided a foundation on which the newer technologies improved.

Overall, CRISPR/Cas9 has become the predominant technology for genome editing in HPV-related research because of its programmability and efficiency. TALENs and ZFNs have been important in establishing feasibility and remain valuable where CRISPR is less ideal. In fact, a head-to-head comparison in 2021 specifically examining HPV16-targeted ZFNs, TALENs, and CRISPR/Cas9 concluded that SpCas9 was more efficient and more specific than either ZFNs or TALENs for HPV gene targeting. As shown by GUIDE-seq analysis, CRISPR/Cas9 had the fewest off-target events in HPV16 E6/E7 regions (0–4 off-target sites) compared to TALENs (1–36) and ZFNs (dozens to hundreds). The authors recommended CRISPR/Cas9 as the preferable platform for clinical development in HPV gene therapy, while noting their data could help improve ZFN/TALEN designs [54].

Table 1 compares the key features of these major genome editing platforms.

3. Therapeutic Applications of Genome Editing for HPV

Genome editing holds promise both as an antiviral strategy to eliminate HPV infection and as a targeted anti-cancer strategy to disable HPV oncogenes in tumors. Unlike conventional treatments that indirectly affect HPV (such as immune therapies) or nonspecifically kill dividing cells (chemotherapy, radiation), genome editing directly modifies the genetic drivers of HPV-related disease. Below, we discuss three major therapeutic applications: (1) eliminating or suppressing HPV infection in affected tissues, (2) targeting the E6/E7 oncogenes in established cancers, and (3) customizing these approaches for personalized medicine.

3.1. Editing the HPV to Eliminate Infection

One approach is to treat an HPV infection at its source by directly cleaving the viral DNA in infected cells. High-risk HPV genomes exist either as episomal circular DNA or integrated segments in host chromosomes [55]. In both cases, introducing DSBs in essential viral genes can incapacitate the virus. If the viral DNA is episomal, a nuclease-induced break can cause the small viral genome to be destroyed or misrepaired such that it can no longer replicate. If the viral DNA is integrated, cutting within E6/E7 can disrupt their expression and also potentially cause the fragment to be excised from the host genome (if two cuts are made flanking the integration site) [56]. Genome editing thus offers a radical possibility: curing an HPV infection by eradicating the viral genome from the patient’s cells. This is conceptually similar to efforts using CRISPR to eliminate latent HIV or HBV infections [57], and indeed HPV shares the challenge that current antivirals cannot purge latent viral genomes.

Preclinical studies have shown promising results in using CRISPR to eliminate HPV. In vitro, CRISPR/Cas9 targeting HPV16 E6/E7 and HPV16/18 E6 selectively eliminated HPV-positive cells, while sparing HPV-negative cells [58,59]. Moreover, CRISPR targeting HPV16 E7 had no effect on HPV-negative or even HPV18-positive cells (HeLa), demonstrating genotype-specific action [60]. In an animal model of cervical HPV infection (K14-HPV16 mice), topical application of a CRISPR/Cas9 vector led to local HPV16 gene disruptions and elimination of precancerous lesions [60].

Several strategies can enhance viral genome clearance. Using dual sgRNAs to cut out a large segment of the HPV genome (such as the entire E6/E7 region) can cause the fragment to be deleted and degraded, as demonstrated with HPV18 where dual CRISPR cuts deleted E6/E7 with high efficiency [61]. Base-editing approaches could also be used to introduce stop codons or inactivate key viral genes without DSBs, which might mitigate concerns about chromosomal translocations in integrated HPV. Although still experimental, the adaptability of CRISPR systems means base editors or prime editors could be repurposed to target HPV sequences [62]. Another possibility is prophylactic gene editing. In high-risk populations (e.g., immunosuppressed individuals), gene editing might be used to prevent progression from persistent infection to neoplasia [63].

Delivery remains a major challenge, particularly for infections in the anogenital tract. Non-invasive methods such as nanoparticle-encapsulated Cas9 RNPs [64] or lentiviral sprays [65] are being developed. One study used a pH-sensitive cationic liposome to deliver Cas9 mRNA and sgRNAs to cervical cancer cells, achieving ~70% editing efficiency of HPV16 E7 in vitro [66]. Such formulations could potentially be applied to an infected epithelium in vivo to produce localized editing. Indeed, CRISPR as an antiviral is being tested for other viruses (e.g., a clinical trial uses CRISPR to excise HIV proviral DNA [67]), highlighting a growing precedent for this strategy.

3.2. Targeting HPV Oncogenes (E6 Aand E7)

HPV-driven cancers are dependent on continuous expression of E6 and E7 oncoproteins [68]. These viral proteins disable p53 and Rb, and their silencing leads to reactivation of tumor suppressor pathways and subsequent cell cycle arrest or apoptosis [69,70,71,72]. Genome editing enables specific knockout of these oncogenes, selectively killing HPV-positive cancer cells while sparing HPV-negative cells [60,71,73].

Multiple proof-of-concept studies have confirmed that editing E6/E7 has potent anti-tumor effects. For instance, using CRISPR/Cas9 to disrupt HPV16 E7 in cervical cancer cells led to upregulation of pRB and sharp inhibition of cell growth [74]. Similarly, CRISPR editing of HPV16 E6 caused apoptosis via reactivation of p53 pathways [20]. Hu et al. showed that a single sgRNA targeting HPV16 E7 reduced E7 expression and restored pRB-mediated cell cycle control [75]. In another study, multiplexed sgRNAS targeting HPV16 E6/E7 caused robust reactivation of p53 and pRB, leading to cancer cell death [61].

In vivo studies corroborate these findings. Jubair et al. systemically delivered CRISPR/Cas9 in HPV16-positive tumor-bearing mice and achieved tumor regression [70].

Treated tumors showed apoptosis as confirmed by TUNEL staining, indicating that loss of E6/E7 triggered cell death. Importantly, that study used PEGylated lipid nanoparticles to deliver the CRISPR-Cas9 plasmid to tumors, an approach that could be translatable to humans as a form of gene therapy infusion. Direct intratumoral injection of CRISPR or TALENs has also been effective in preclinical HPV models [66].

E6/E7 are ideal gene-editing targets. Unlike conventional drugs, genome editing can break non-enzymatic targets like E6/E7, which are otherwise undruggable due to their protein-protein interaction mechanisms [76]. This approach has the potential to overcome the limitations of current therapies, which do not directly eliminate viral oncogenes.

Preclinical data support a model where a CRISPR/Cas9 vector targeting HPV oncogenes is delivered into a cervical, oropharyngeal or anal tumor. Cells harboring E6/E7 are edited, leading to apoptosis and tumor shrinkage [60,74,75]. In SiHa xenograft models, intratumoral CRISPR delivery significantly inhibited tumor growth [37]. In HPV16-transgenic mice, topical application of CRISPR regressed lesions and restored normal epithelial histology [73]. These dramatic results underscore the therapeutic potential of attacking the HPV oncogene “Achilles’ heel” of these cancers.

Figure 1 shows different genome editing platforms used to target HPV E6/E7.

3.3. Potential for Personalized Medicine

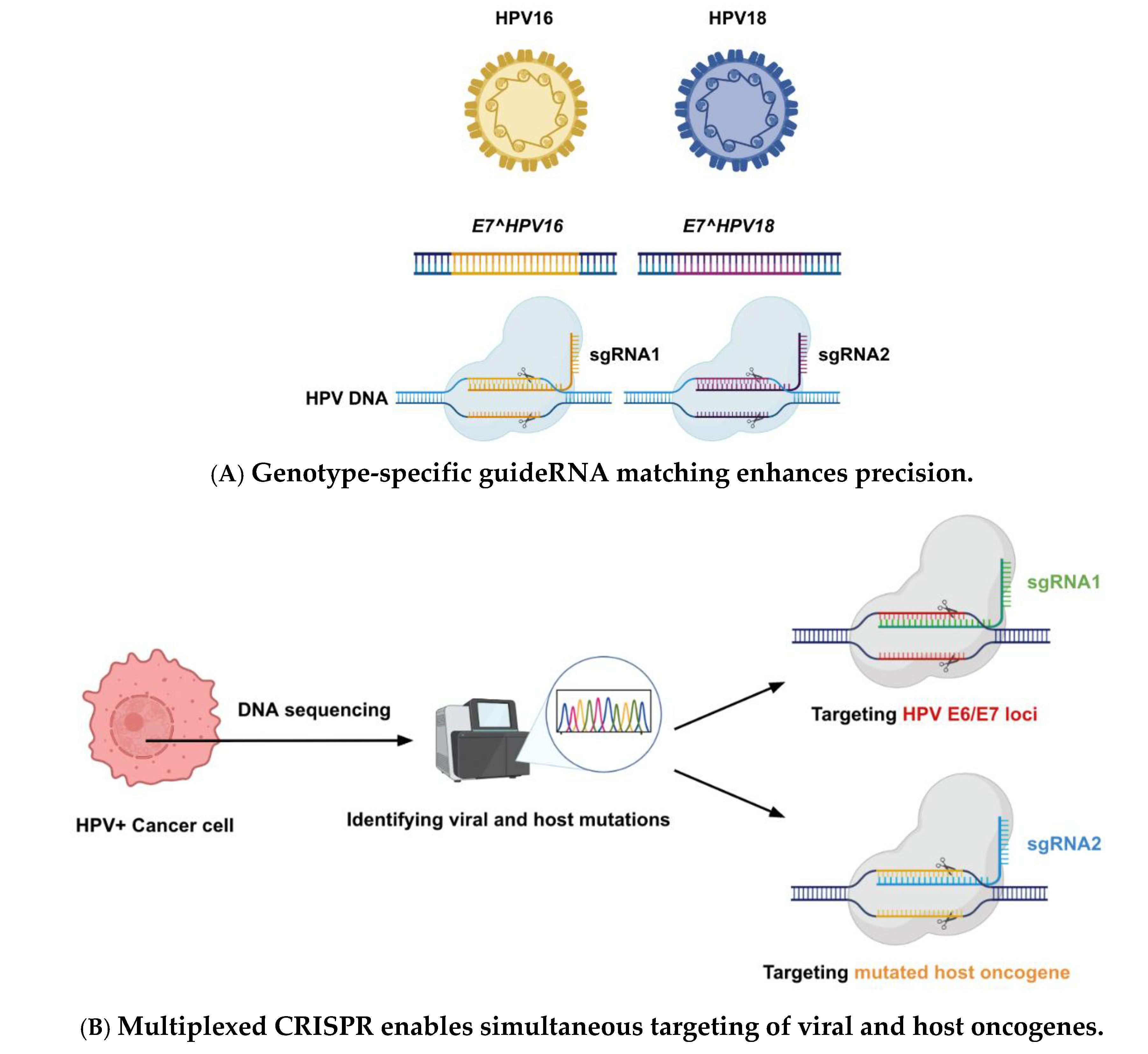

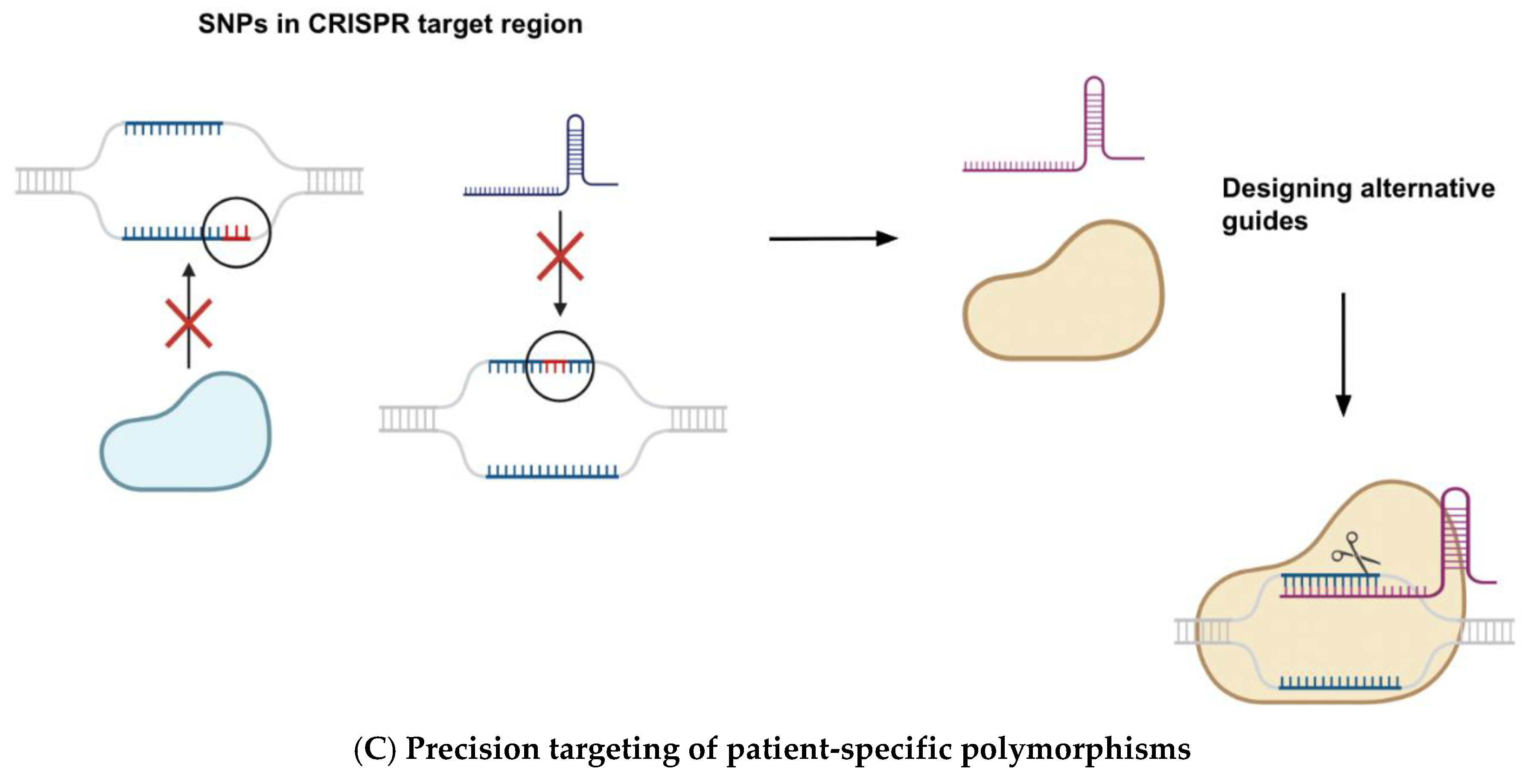

Personalized medicine entails tailoring treatment to the individual characteristics of each patient’s disease. Genome editing therapies for HPV can be personalized on several fronts. First, they can be customized to the patient’s HPV genotype. There are many high-risk HPV types (16, 18, 31, 33, etc.), each with slightly different DNA sequences for E6 and E7. A “one-size” CRISPR will not fit all – for example, a guide RNA targeting HPV16 E6 or E7 will not bind HPV18 oncoproteins due to sequence mismatches [71]. However, it is straightforward to sequence a patient’s HPV and then design an sgRNA (or a set of sgRNAs) that specifically target that genotype’s oncogenes. This means a CRISPR therapy could be crafted to precisely match the patient’s virus, maximizing efficacy and minimizing off-target issues. The high specificity of CRISPR is illustrated by the earlier example: a guide for HPV16 had no effect on HPV18-positive cells, so treatment must be genotype-specific. In practice, one could have a panel of pre-validated guides for the most common HPV types. After testing the patient’s biopsy and confirming, say, HPV33 is present, the clinician would choose the HPV33-specific CRISPR vector for therapy.

Second, beyond HPV type, personalized editing might consider the patient’s tumor genetics. Some HPV-associated cancers accumulate additional mutations (in host genes) that could influence response. It is conceivable to edit not just HPV genes but also certain host genes to enhance treatment. For instance, if a tumor has a particular activated oncogene that is drug-resistant, an adjunct CRISPR could knock that out too. While primarily speculative, CRISPR’s multiplexing ability allows simultaneously targeting multiple DNA sites. In a personalized context, one could target HPV E6/E7 and a host checkpoint gene in the same treatment, tailoring to that tumor’s unique profile.

Another aspect is using gene editing to engineer personalized immune cells. Although not direct editing of HPV genes, it’s worth noting that CRISPR is being used to create personalized cell therapies (e.g., editing a patient’s T cells to enhance their cancer-fighting ability [77]). For HPV-related cancers, one might extract T cells from the patient, use CRISPR to insert a T-cell receptor that recognizes an HPV E6 peptide (or knock out inhibitory receptors), and reinfuse them – a personalized adoptive cell therapy approach. In fact, a recent trial used T cells engineered with an HPV16 E6-specific T-cell receptor in patients with cervical cancer, and a subset of patients saw tumor regression [78]. Those T cells were not edited by CRISPR (they were transduced), but future iterations could use CRISPR to improve their safety (e.g., knock out native TCR or PD-1). This blurs into immunotherapy, but it highlights how gene editing can personalize treatment: either by directly editing the tumor’s vulnerabilities or by tailoring the patient’s immune weaponry.

Lastly, personalized medicine is about precision – treating the disease with minimal collateral damage. Genome editing’s precision aligns well with this goal. With improved target specificity, a CRISPR treatment for HPV could be extremely precise (hitting only cells with the virus). Even among those cells, if, say, a patient had a rare single-nucleotide polymorphism in the target region that could block guide binding, the treatment could be adjusted (a different guide or base editor chosen). Such fine-tuning is not possible with conventional drugs. In summary, genome editing therapies for HPV can be individualized by HPV type and potentially by patient-specific factors, embodying the personalized medicine paradigm of delivering the right treatment to the right patient at the right genetic target.

Figure 2 shows some of the personalized genome editing strategies like genome-specific guideRNA creation, multiplexed CRISPR and targeting patient-specific polymorphisms.

4. Preclinical and Clinical Research Progress

4.1. Preclinical Efficacy in Models

Preclinical studies have laid the groundwork for genome editing therapies targeting HPV, providing compelling evidence that disruption of viral oncogenes can suppress tumor growth and induce apoptosis in HPV-positive cells. Zhen et al. demonstrated that CRISPR/Cas9-mediated targeting of HPV16 E6 and E7 led to suppression of tumor growth in both in vitro and in vivo cervical cancer models, validating the approach as a promising therapeutic strategy [58]. Similarly, Hu et al. employed TALENs in HPV-transgenic mouse models, resulting in lesion regression, underscoring the therapeutic utility of earlier genome editing platforms [21].

Subsequent advancements introduced dual-targeting strategies, using paired sgRNAs to simultaneously disrupt both E6 and E7, preventing the compensatory survival effect that might occur if only one oncogene is inactivated. Jubair et al. applied this dual-targeting approach in a murine cervical cancer model and achieved complete tumor regression. Mechanistic analysis revealed increased expression of apoptotic markers, confirming oncoprotein inactivation as the principal mechanism of action [70].

In addition to efficacy, delivery and safety have been central concerns in preclinical models. Various delivery vehicles have been explored, including plasmid vectors, mRNA, viral systems, and ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complexes. Notably, nanoparticle-based delivery of Cas9 mRNA targeting HPV E6/E7 significantly suppressed tumor growth in murine models when combined with docetaxel [79]. These formulations hold promise for systemic administration, akin to traditional chemotherapeutics, and may eventually enable broader application in metastatic settings.

Off-target effects remain a key safety consideration. Cui et al. compared zinc finger nucleases (ZFNs), TALENs, and CRISPR-Cas9 targeting HPV16 sequences using genome-wide unbiased identification of DSBs enabled by sequencing (GUIDE-seq). Their results showed CRISPR-Cas9 exhibited the most favorable specificity profile, with minimal off-target activity in E6/E7 regions [50]. This finding supports the continued refinement of sgRNA designs and highlights the importance of specificity profiling in translational pipelines.

Beyond cervical cancer, genome editing is being explored in other HPV-related malignancies, including head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC). While delivery to deep-seated oropharyngeal tumors presents logistical challenges, early studies suggest viral vector-mediated delivery, such as oncolytic adenoviruses carrying CRISPR-Cas9, may be feasible [80]. Moreover, patient-derived xenograft (PDX) models from HPV-positive cancers are increasingly used to assess the efficacy and safety of genome editing approaches, providing a platform for preclinical validation in anatomically and genetically relevant systems [81].

Table 2 and

Table 3 summarize the in vitro & in vivo representative preclinical studies utilizing these genome editing technologies against HPV, demonstrating the progression from early ZFN/TALEN attempts to recent CRISPR successes.

4.2. Clinical Trials and Studies

Clinical translation of HPV-targeted genome editing is in its infancy, with only a limited number of trials currently underway. The first registered clinical trial (NCT03057912) evaluating gene editing for HPV was initiated by Sun Yat-sen University in China. This open-label Phase I study aims to assess the safety and efficacy of CRISPR/Cas9 or TALEN plasmids targeting E6/E7, administered intravaginally in women with persistent HPV16 or HPV18 infection and cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN) grade I [82]. While the trial status is currently “unknown,” its initiation marks a milestone in the clinical application of CRISPR-based antivirals for oncogenic viruses.

The design of this trial capitalizes on the localized and accessible nature of CIN lesions, providing a low-risk environment for first-in-human evaluation. The gene therapy is delivered topically, minimizing systemic exposure, and the primary endpoints include lesion regression and HPV clearance. If successful, this study would provide the first human evidence of CRISPR-mediated viral genome eradication, supporting a new class of antiviral therapeutics.

Other clinical efforts involve gene-edited immune cells in HPV-positive cancers. For instance, a trial in China (NCT02793856) employed CRISPR to knock out the PD-1 gene in autologous T cells, which were then reinfused into patients with HPV-positive metastatic non-small cell lung cancer. The trial reported no serious adverse events linked to gene editing, establishing preliminary safety of CRISPR-engineered cell therapies in cancer patients [83].

Additionally, immunotherapies engineered to recognize HPV antigens have entered clinical development. A notable example includes the use of T cells engineered with an HPV16 E6-specific T-cell receptor (TCR) in patients with metastatic cervical cancer. In a Phase I/II trial, 2 of 12 patients demonstrated objective responses [78]. Although these cells were transduced rather than edited, future iterations are expected to incorporate CRISPR for precise engineering—such as endogenous TCR knockout to prevent mispairing or PD-1 deletion to enhance persistence.

While no genome editing therapies for HPV have received regulatory approval to date, analogous advances in other viral targets provide important precedence. Trials targeting integrated HIV DNA with CRISPR (e.g., EBT-101 for excision of latent HIV) have entered clinical stages [67], suggesting that similar strategies could be applicable to persistent HPV infection. The success of such trials will inform delivery platforms, safety assessments, and regulatory pathways for HPV-directed editing.

Moreover, therapeutic vaccines such as VGX-3100 (targeting HPV16/18 E6/E7 DNA) have demonstrated efficacy in CIN2/3 [84,85], VIN2/3 [88], AIN2/3 and PAIN2/3 [89,90] regression, providing a clinical benchmark. In a Phase II trial, VGX-3100 achieved 49.5% histopathologic regression in cervical HSIL versus 30.6% with placebo [85]. Therefore, any CRISPR-based HPV therapy must match or exceed these efficacy rates and safety profiles to justify clinical deployment.

Table 4 gives an overview of the ongoing and completed clinical trials utilizing gene editing tools to combat HPV-associated malignancies.

In summary, the preclinical-to-clinical pipeline for genome editing in HPV-associated disease is progressing steadily. While the field is in early stages, the biological rationale, preclinical data, and emerging trial activity suggest a promising future. Continued efforts in optimizing delivery, guide design, and patient stratification will be critical for clinical success.

5. Oncological Perspectives and Integration into Treatment

Genome editing offers a novel therapeutic strategy for HPV-related diseases by integrating directly into the oncology care paradigm. Its unique mechanism—disrupting viral oncogenes—complements or potentially surpasses current therapeutic modalities including surgery, radiotherapy, chemotherapy, immunotherapy, and therapeutic vaccines [91]. Strategic deployment of gene editing must consider the disease stage, anatomical accessibility, and patient-specific factors to optimize benefit. [62]

5.1. Complement to Existing Therapies:

A promising application of genome editing lies in intercepting premalignant HPV-related lesions. For patients with persistent or multifocal cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN), CRISPR-based therapy could offer an alternative to repeated surgical excisions, which are associated with cervical insufficiency and adverse pregnancy outcomes [92]. In particular, locally applied CRISPR therapeutics (e.g., a gel-based formulation) targeting E6/E7 oncogenes could eradicate infection and dysplastic cells while preserving cervical integrity [93].

For CIN1 cases where lesions often regress spontaneously, gene editing may facilitate lesion clearance in persistent cases, reducing the psychosocial burden associated with HPV diagnosis. In this setting, genome editing would function as a preventive or interceptive intervention, rather than replacing standard cancer therapies.

In invasive cervical or head and neck cancers, genome editing may function as an adjunct to standard therapies. Preclinical studies suggest that inactivating HPV oncogenes restores p53/Rb pathways, sensitizing tumors to radiation and chemotherapy [79,94,95]. For example, pre-treatment with E6/E7-targeted CRISPR may enhance tumor cell susceptibility to DNA damage-induced apoptosis. Additionally, adjuvant delivery of gene editing agents post-surgery could target microscopic residual HPV-positive cells, reducing recurrence risk without systemic toxicity.

5.2. Comparison with Immunotherapy:

Checkpoint inhibitors such as pembrolizumab have modest efficacy in HPV-positive cancers, with objective response rates of approximately 14% in cervical cancer [96]. Adoptive T-cell therapies, including tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) or engineered T cells expressing HPV-specific TCRs, have shown early promise but are dependent on patient immune status [97]. In contrast, genome editing directly induces cytotoxicity in HPV-positive cells and may be effective in immunocompromised individuals, such as transplant recipients or HIV-positive patients with HPV-associated lesions [91].

Importantly, genome editing may also synergize with immunotherapies. The immunogenic cell death following CRISPR-mediated E6/E7 knockout can release viral antigens and prime an anti-tumor immune response. This "in situ vaccination" effect may enhance the efficacy of checkpoint inhibitors [98]. Furthermore, gene editing-induced tumor cell death may shift the tumor microenvironment towards an inflamed, immuno-permissive state, improving immunotherapy outcomes [99].

5.3. Versus Chemoradiation:

Chemoradiation remains the standard of care for locally advanced cervical cancer [100]. However, recurrence rates remain significant in patients with bulky or high-risk tumors. Genome editing offers a tumor-specific alternative, potentially avoiding systemic side effects such as nephrotoxicity, neurotoxicity, nausea, and infertility associated with cisplatin-based regimens [101].

Compared to radiotherapy, gene editing may induce less off-target damage to adjacent normal tissues, provided precise delivery is achieved. This could preserve organ function and reduce long-term sequelae such as fibrosis, vaginal stenosis, and bowel injury [102]. However, challenges remain in ensuring that gene editing agents reach the same breadth of tumor burden as ionizing radiation, especially in diffusely infiltrative disease.

5.4. Unique Benefit – Viral Specificity:

One perspective often voiced in oncology is that virally-induced tumors present unique targets (the viral genes) that non-virally-induced tumors lack. This has been exploited by therapeutic vaccines and by T-cell therapies [103]. Genome editing is another way to exploit the virus-specific target. It’s akin to a magic bullet that only cancer cells (with the virus) will absorb. This is particularly relevant in multifocal disease – for example, HPV can cause field cancerization in the urogenital tract; after one lesion is treated, new ones can appear [104]. A systemic or regional gene editing treatment might simultaneously treat all lesions, something surgery or localized radiation cannot do easily. In patients with HPV-driven oropharyngeal cancer, often multiple tumors or extensive carcinoma in situ can be present (like spreading along the mucosa) [105]; gene editing delivered by a viral vector that diffuses through the mucosa could potentially treat a broad area.

5.5. Safety Considerations in Oncology:

Oncologists will be cautious about gene editing toxicity. Off-target cuts in the human genome that hit, say, a tumor suppressor or essential gene in normal cells could theoretically initiate secondary malignancies or other issues. Long-term follow-up will be needed for any gene therapy to ensure we’re not causing new problems while curing HPV. That said, traditional treatments like radiation also cause DNA damage and carry a risk of secondary cancers [106]; the hope is a targeted gene editor will actually be safer in that regard by focusing the breaks where you intend them. Preclinical data so far, as mentioned, show minimal off-target effects with properly designed CRISPR in the HPV context, which is encouraging.

5.6. Patient Acceptance and Feasibility:

From a patient-centered perspective, gene editing could be appealing as a non-invasive or minimally invasive outpatient therapy. Cervical injections, topical gels, or intravenous infusions of nanoformulated CRISPR may reduce treatment burdens compared to hospital-based radiation or surgical procedures [107]. Moreover, reduced systemic toxicity could improve quality of life during therapy.

Nonetheless, public perception of gene editing remains a potential barrier. Misconceptions about germline modification or irreversible DNA damage may evoke fear or resistance. Effective communication strategies must emphasize the somatic and therapeutic nature of the intervention, and the virus-specific targeting of cancer cells.

6. Challenges and Future Prospects

While the promise of genome editing for HPV is great, several challenges must be overcome before these therapies become routine.

6.1. Technical Hurdles:

The foremost technical challenge is delivery. Getting the genome editing molecules to the right cells in the patient – and enough of those cells – is non-trivial [108] . For cervical lesions, direct application is possible (e.g., using a cervical spray or injection) [109], but for internal tumors like oropharyngeal cancer or metastatic disease, one might need systemic delivery [110]. Viral vectors (such as adenovirus or AAV) can deliver genes efficiently, but they come with size limits and potential immune reactions [111]. Non-viral methods like lipid nanoparticles or polymer nanoparticles are being actively developed; Poly (β-Amino Ester)-based nanoparticles were used successfully to deliver CRISPR to HPV tumors [112,113,114]. Optimizing these carriers for human use is ongoing – for example, designing pH-responsive or tissue-targeted nanoparticles to improve uptake by cervical or tumor tissues [66].

6.2. Efficiency of Editing

In a tumor, if only, 50% of cells get edited, the remaining 50% might continue to proliferate (though they might have less growth advantage if their neighbors are dying and releasing cytokines). A high editing rate will be important for robust efficacy. Strategies like using base editors or Cas nucleases fused to cytidine deaminase (which can induce mutations without needing a cut on every allele) could help amplify the effect even if delivery is not 100%. [115]

Off-target effects and genomic safety remain significant technical and scientific challenges. Although improved guide design has reduced off-target cutting, we cannot assume zero off-targets. Each new guide intended for clinical use will require comprehensive screening (perhaps with unbiased methods like GUIDE-seq or DISCOVER-seq in relevant human cell types) to ensure it doesn't significantly hit other genomic sites. It’s reassuring that well-designed guides for 3 HPV16 critical target genes in one study showed very minimal detectable off-target activity [50]. Additionally, since the target cells (e.g., cervical epithelium) can be biopsied, there is potential to verify editing events after treatment to ensure only the desired edits occurred. If undesired mutations are found, it would raise flags. Another nuance is if the HPV genome is integrated in a critical location in the host genome – cutting it out might cause a large deletion in a host chromosome. For example, if HPV inserted within a tumor suppressor gene, using CRISPR to cut out HPV might also excise part of that suppressor. This scenario is unpredictable and rare, but possible. It might be mitigated by understanding common integration sites (HPV often integrates in fragile sites or in certain loci; if one knows the integration, one could plan the cut strategy accordingly).

6.3. Immune Responses and Safety:

Delivering a bacterial protein like Cas9 or foreign TALE proteins could provoke an immune response [116]. This is double-edged: on one hand, a localized immune response might help kill tumor cells (good for efficacy), but on the other hand it could limit repeated dosing or cause inflammatory side effects. Immune responses against AAV or adenoviral vectors are well-documented, and repeated dosing can be problematic if neutralizing antibodies form [117]. For a one-time therapy in a localized site, this might be acceptable. Using human protein-based editors (e.g., a human-derived endonuclease, though none are in clinical use yet) is an interesting idea but not currently practical. Immune suppression during treatment is another approach (e.g., giving a short course of steroids or immunosuppressants to allow the editor to do its job without being cleared too fast). The balance between harnessing inflammation to attack the virus-infected cells and avoiding systemic autoimmunity will need careful management.

6.4. Ethical and Regulatory Concerns:

Ethically, somatic genome editing for life-threatening conditions is generally accepted, but caution is paramount. It is crucial to emphasize that these interventions would not affect germline DNA – especially important for therapies in the reproductive tract like cervical treatments, to reassure that we are not altering eggs or sperm. In preclinical models, CRISPR delivered to the cervix did not result in detectable edits in the ovaries or distant tissues, suggesting localization can be achieved. Regulators will require extensive safety data, likely including animal studies in non-human primates or other models, to show that the gene therapy does not cause unintended consequences. Long-term follow-up of trial participants (for many years) will be mandated to monitor for any delayed adverse effects like secondary cancers. Another ethical aspect is informed consent and patient understanding – “gene editing” might sound frightening; clear education is needed so patients understand the therapy’s intent and risks.

Cost and access are also considerations for the future. Gene therapies tend to be expensive. If a CRISPR-based HPV cure costs significantly more than, say, surgery or standard chemo, that could limit adoption, especially in low-resource settings where HPV disease is most prevalent. Simplifying the treatment (maybe one or two outpatient applications) and scaling manufacturing could help reduce cost. The good news is that plasmids or RNAs are relatively inexpensive to produce compared to monoclonal antibodies or cell therapies. If the field can produce “off-the-shelf” CRISPR kits for common HPV types, it might be cost-effective in the long run, especially considering the healthcare savings from preventing cancers.

6.5. Future Research Directions:

Future work will likely explore refined genome editors – such as base editors (which can introduce stop codons in E6/E7 without a DSB) or prime editors (which could precisely insert disruptive sequences or corrections) [62]. These next-generation tools might avoid DSB-associated risks like chromosomal rearrangements. Base editing of HPV, for instance, could mutate the start codon of E7 or create nonsense mutations in E6, permanently inactivating them without cutting the DNA – an elegant solution if it can be delivered efficiently. Already, researchers have noted that given the small size of HPV genes, even a single base change can knock out oncoprotein function, so base editors could be very effective.

Another area is expanding targetable sites. Cas9 requires a PAM (NGG) [118], which might not be optimally placed to cut some HPV genes. Using other nucleases like Cas12a/Cpf1 (which has a different PAM and staggered cut) could open up more targeting options. Indeed, one study reported using CRISPR/Cas12a to detect HPV DNA [119]; the same enzyme could be used to cut HPV DNA with a TTTV PAM requirement. Additionally, the concept of repurposing CRISPR as a suppressor (CRISPRi) could be explored: instead of cutting, a dCas9 fused to a repressor could sit on the HPV promoter region and shut off E6/E7 transcription [120]. This might be safer (no breaks at all), but would require continuous presence or expression, which is a different therapeutic model (more akin to a drug you have to keep taking, rather than a one-and-done edit).

6.6. Translational Potential:

The next few years will be telling as initial clinical data emerges. If the early CIN trial shows positive results, we might see rapid moves to test such therapies in high-grade lesions (CIN3) or even as an adjunct in early cervical cancers to preserve fertility (e.g., treating with CRISPR instead of doing a radical trachelectomy for a small tumor). For head and neck cancers, perhaps a local injection during endoscopy could be trialed. There’s also interest in HPV-associated anal intraepithelial neoplasia (AIN) in high-risk groups (like HIV-positive individuals) – a gene editing approach could be very useful there since those lesions are often multifocal and recurrent.

Regulatory approval will depend on demonstrating that the benefits (cancer prevention or treatment) outweigh the risks of off-target effects. Given that current treatments for advanced HPV cancers still have significant failure rates, a successful new modality would be welcome. We might imagine a future where persistent HPV infection is treated akin to how we treat Helicobacter pylori to prevent stomach cancer [121] – i.e., you diagnose an HPV infection that isn’t clearing, and instead of just monitoring, you give a gene therapy to knock it out.

7. Conclusions

HPV-driven cancers present a unique opportunity for genome editing interventions, and considerable progress has been made toward realizing this potential. In this review, we discussed how CRISPR/Cas9, TALENs, and ZFNs can be harnessed to target HPV’s oncogenic DNA, and we surveyed a decade’s worth of studies that have built the case for using these technologies in HPV infection and cancer therapy. The key takeaway is that genome editing allows us to go after the source of HPV’s oncogenicity – the viral genes – with precision and permanence unmatched by conventional treatments. Preclinical successes, from cell lines to animal models, have demonstrated that cutting HPV E6/E7 reinstates tumor suppressor pathways and can eliminate tumors. Early clinical endeavors are now testing safety and feasibility in humans, marking the start of translating benchside breakthroughs to bedside reality. CRISPR/Cas9 has emerged as the leading platform due to its simplicity and efficiency, although TALENs and ZFNs provided crucial groundwork and remain part of the toolkit. Therapeutically, genome editing could be deployed to clear persistent HPV infections, thereby preventing cancer before it starts, or to disable HPV oncogenes in existing cancers, providing a targeted treatment that complements or enhances current modalities. Its integration into oncology could range from treating precancerous lesions to improving outcomes in refractory metastatic disease. We also addressed the significant challenges ahead: delivering the editors safely and effectively to patients, ensuring on-target activity with minimal off-target effects, and navigating regulatory and ethical considerations. These challenges, while non-trivial, are being actively tackled through advances in vector engineering (like smarter nanoparticles and high-fidelity nucleases) and thorough preclinical validation. Ethical deployment of this technology will require transparent clinical trials and long-term monitoring, but the path is being paved by related gene therapy efforts in other diseases. Looking to the future, it is plausible that within the next decade, if clinical trials are successful, we will see the first approved genome editing treatment for HPV-related condition. This might initially be a gene therapy for high-grade cervical dysplasia or a life-saving option for patients with HPV-positive cancers unresponsive to other treatments. Continued research is likely to yield even safer and more powerful editing tools – for example, base editors that could knock out HPV genes without even cutting DNA, or novel delivery systems that can target affected tissues with high specificity. Combining genome editing with immunotherapy or other targeted therapies could produce synergistic effects, turning HPV tumors’ viral dependence into a fatal weakness. In summary, genome editing in HPV and HPV-associated cancers stands at a promising frontier. It exemplifies the convergence of virology, molecular biology, and clinical oncology to address a major global health issue in a novel way. Should ongoing studies confirm its safety and efficacy, genome editing could become a paradigm-changing addition to how we manage HPV-related diseases – moving us closer to the day when persistent HPV infections and the cancers they cause can be not just treated, but cured at the genetic level. The work so far provides strong justification for continued investment and investigation in this approach, with the ultimate goal of reducing the burden of HPV cancers worldwide through precise, gene-targeted therapy.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org, Figure S1: title; Table S1: title; Video S1: title.

Author Contributions

For research articles with several authors, a short paragraph specifying their individual contributions must be provided. The following statements should be used “Conceptualization, X.X. and Y.Y.; methodology, X.X.; software, X.X.; validation, X.X., Y.Y. and Z.Z.; formal analysis, X.X.; investigation, X.X.; resources, X.X.; data curation, X.X.; writing—original draft preparation, X.X.; writing—review and editing, X.X.; visualization, X.X.; supervision, X.X.; project administration, X.X.; funding acquisition, Y.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.” Please turn to the CRediT taxonomy for the term explanation. Authorship must be limited to those who have contributed substantially to the work reported.

Funding

Please add: “This research received no external funding” or “This research was funded by NAME OF FUNDER, grant number XXX” and “The APC was funded by XXX”. Check carefully that the details given are accurate and use the standard spelling of funding agency names at

https://search.crossref.org/funding. Any errors may affect your future funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

In this section, you should add the Institutional Review Board Statement and approval number, if relevant to your study. You might choose to exclude this statement if the study did not require ethical approval. Please note that the Editorial Office might ask you for further information. Please add “The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of NAME OF INSTITUTE (protocol code XXX and date of approval).” for studies involving humans. OR “The animal study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of NAME OF INSTITUTE (protocol code XXX and date of approval).” for studies involving animals. OR “Ethical review and approval were waived for this study due to REASON (please provide a detailed justification).” OR “Not applicable” for studies not involving humans or animals.

Informed Consent Statement

Any research article describing a study involving humans should contain this statement. Please add “Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.” OR “Patient consent was waived due to REASON (please provide a detailed justification).” OR “Not applicable.” for studies not involving humans. You might also choose to exclude this statement if the study did not involve humans. Written informed consent for publication must be obtained from participating patients who can be identified (including by the patients themselves). Please state “Written informed consent has been obtained from the patient(s) to publish this paper” if applicable.

Data Availability Statement

We encourage all authors of articles published in MDPI journals to share their research data. In this section, please provide details regarding where data supporting reported results can be found, including links to publicly archived datasets analyzed or generated during the study. Where no new data were created, or where data is unavailable due to privacy or ethical restrictions, a statement is still required. Suggested Data Availability Statements are available in section “MDPI Research Data Policies” at

https://www.mdpi.com/ethics.

Acknowledgments

In this section, you can acknowledge any support given which is not covered by the author contribution or funding sections. This may include administrative and technical support, or donations in kind (e.g., materials used for experiments).

Conflicts of Interest

Declare conflicts of interest or state “The authors declare no conflicts of interest.” Authors must identify and declare any personal circumstances or interest that may be perceived as inappropriately influencing the representation or interpretation of reported research results. Any role of the funders in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results must be declared in this section. If there is no role, please state “The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results”.

References

- Stanley, M. Pathology and epidemiology of HPV infection in females. Gynecol Oncol. 2010;117(2 Suppl):S5–10. [CrossRef]

- zur Hausen, H. Papillomaviruses and cancer: from basic studies to clinical application. Nat Rev Cancer. 2002 May;2(5):342–50. [CrossRef]

- Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A, Bray F. Global cancer statistics 2020. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021;71(3):209–249. [CrossRef]

- Moody CA, Laimins LA. Human papillomavirus oncoproteins: pathways to transformation. Nat Rev Cancer. 2010;10(8):550–60. [CrossRef]

- McLaughlin-Drubin ME, Münger K. The human papillomavirus E7 oncoprotein. Virology. 2009;384(2):335–344. [CrossRef]

- Münger K, Howley PM. Human papillomavirus immortalization and transformation functions. Virus Res. 2002;89(2):213–228. [CrossRef]

- Doorbar, J. Molecular biology of human papillomavirus infection and cervical cancer. Clin Sci (Lond). 2006;110(5):525–41. [CrossRef]

- Koutsky, L. Epidemiology of genital human papillomavirus infection. Am J Med. 1997 ;102(5A):3–8. 5 May. [CrossRef]

- Arbyn M, Castellsagué X, de Sanjosé S, Bruni L, Saraiya M, Bray F, Ferlay J. Worldwide burden of cervical cancer in 2008. Ann Oncol. 2011;22(12):2675–86. [CrossRef]

- Garland SM, Hernandez-Avila M, Wheeler CM, Perez G, Harper DM, Leodolter S, et al. Quadrivalent vaccine against HPV to prevent high-grade cervical lesions. N Engl J Med. 2007;356(19):1928–43. [CrossRef]

- Drolet M, Bénard É, Pérez N, Brisson M, HPV Vaccination Impact Study Group. Population-level impact and herd effects following the introduction of human papillomavirus vaccination programmes: updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2019;394(10197):497–509. [CrossRef]

- Pimple SA, Mishra GA. Global strategies for cervical cancer prevention and screening. Minerva Ginecol. 2022;74(5):372–381. [CrossRef]

- Jemal A, Center MM, DeSantis C, Ward EM. Global patterns of cancer incidence and mortality rates and trends. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2010;19(8):1893–907. [CrossRef]

- Joung JK, Sander JD. TALENs: a widely applicable technology for targeted genome editing. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2013;14(1):49–55. [CrossRef]

- Sander JD, Joung JK. CRISPR-Cas systems for editing, regulating and targeting genomes. Nat Biotechnol. 2014;32(4):347–355. [CrossRef]

- Urnov FD, Rebar EJ, Holmes MC, Zhang HS, Gregory PD. Genome editing with engineered zinc finger nucleases. Nat Rev Genet. 2010;11(9):636–646. [CrossRef]

- Wang JW, Roden RBS. L2, the minor capsid protein of papillomavirus. Virology. 2013;445(1–2):175–86. [CrossRef]

- Smith TT, Friedman J, Yu J, Carnahan RH, Reynolds KL, et al. Targeted genome editing in human papillomavirus-associated cancer. Int J Cancer. 2021;148(5):1176–1185. [CrossRef]

- Liu Y, Zhao Y, Lin J, Chen C, Tao Q, Li S, et al. Therapeutic genome editing of HPV genes using CRISPR/Cas9. Mol Ther Oncolytics. 2020;17:282–291. [CrossRef]

- Zhen S, Hua L, Takahashi Y, Narita S, Liu YH, Li Y. In vitro and in vivo growth suppression of human papillomavirus 16-positive cervical cancer cells by CRISPR/Cas9. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2014;450(4):1422–6. [CrossRef]

- Hu Z, Yu L, Zhu D, Ding W, Wang X, Zhang C, et al. Disruption of HPV16-E7 by TALEN leads to growth inhibition and apoptosis in HPV16-positive human cervical cancer cells. J Biomed Res. 2015;29(3):193–202. [CrossRef]

- Natarajan N, Sellers TA. Human papillomavirus entry and genome delivery. Human papillomavirus entry and genome delivery. StatPearls. 2023. [PubMed]

- zur Hausen, H. Papillomaviruses and cancer: from basic studies to clinical application. Nat Rev Cancer. [CrossRef]

- Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A, Bray F. Global cancer statistics 2020. CA Cancer J Clin. [CrossRef]

- WHO. Cervical cancer fact sheet. 2023.

- Moody CA, Laimins LA. Human papillomavirus oncoproteins: pathways to transformation. Nat Rev Cancer. [CrossRef]

- McLaughlin-Drubin ME, Münger K. The human papillomavirus E7 oncoprotein. Virology. [CrossRef]

- Egawa N, Doorbar J. The low-risk papillomaviruses. Virus Res. [CrossRef]

- Koutsky, L. Epidemiology of genital human papillomavirus infection. Am J Med. [CrossRef]

- Moscicki AB, Schiffman M, Kjaer S, et al. Human papillomavirus infection and clearance: a meta-analysis. J Infect Dis. 1340.

- Garland SM, Hernandez-Avila M, Wheeler CM, et al. Quadrivalent vaccine against HPV to prevent high-grade cervical lesions. N Engl J Med. 1928. [CrossRef]

- Arbyn M, de Sanjosé S, Saraiya M, et al. HPV outcome and screening in low-resource settings. Lancet Oncol. [CrossRef]

- Joung JK, Sander JD. TALENs: a widely applicable technology for genome editing. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. [CrossRef]

- Sander JD, Joung JK. CRISPR–Cas systems for editing human genomes. Nat Biotechnol. [CrossRef]

- Urnov FD, Rebar EJ, Holmes MC, Zhang HS, Gregory PD. Genome editing with ZFNs. Nat Rev Genet. [CrossRef]

- Komor AC, Badran AH, Liu DR. CRISPR-based technologies for eukaryotic genome manipulation. Cell. [CrossRef]

- Zhen S, Hua L, Takahashi Y, et al. CRISPR/Cas9 mediated HPV E6/E7 disruption inhibits tumor growth in vivo. BBRC. 1422. [CrossRef]

- Hu Z, Yu L, Zhu D, et al. TALEN-mediated E7 disruption suppresses cervical cancer. J Biomed Res. [CrossRef]

- Liu Y, Zhao Y, Lin J, et al. CRISPR/Cas9 targeting HPV in human cervical cancer. Mol Ther Oncolytics. [CrossRef]

- Li M, Lee K, Henderson J, et al. mRNA-based delivery of genome editors enables transient expression and reduced off-target effects. Nat Biotechnol.

- Kennedy EM, Kornepati AVR, Cullen BR. TALEN-mediated targeting of HPV oncogenes E6/E7 in K14-HPV16 transgenic mice reverses cervical neoplasia. Mol Ther, 1006.

- Cermak T, Doyle EL, Christian M, et al. Efficient design and assembly of custom TALEN and TALE-based constructs for DNA targeting. Nucleic Acids Res.

- Schmid-Burgk JL, Schmidts A, Guell M, et al. Genome-wide tolerance of TALENs to mismatches: off-target profiling in human cells. Genome Res.

- Kleinstiver BP, Sousa AA, Alwin S, et al. Modulating TALEN DNA-binding affinity reveals trade-offs in cutting specificity. Sci Rep, 1239.

- Davis, D. , and Stokoe, D. (2010). Zinc finger nucleases as tools to understand and treat human diseases. BMC Medicine, 8(1). [CrossRef]

- Cradick, T. J.; et al. (2011). Zfn-site searches genomes for zinc finger nuclease target sites and off-target sites. BMC Bioinformatics, 12(1). [CrossRef]

- Zhu, C.; et al. (2013). Using defined finger–finger interfaces as units of assembly for constructing zinc-finger nucleases. Nucleic Acids Research, 41(4), 2455-2465. [CrossRef]

- Tebas, P.; et al. (2014). Gene editing ofccr5in autologous cd4 t cells of persons infected with hiv. New England Journal of Medicine, 370(10), 901-910. [CrossRef]

- Katayama, S.; et al. (2024). Engineering of zinc finger nucleases through structural modeling improves genome editing efficiency in cells. Advanced Science, 11(23). [CrossRef]

- Cui Z, Liu H, Zhang H, Huang Z, Tian R, Li L, Fan W, Chen Y, Chen L, Zhang S, Das BC, Severinov K, Hitzeroth II, Debata PR, Jin Z, Liu J, Huang Z, Xie W, Xie H, Lang B, Ma J, Weng H, Tian X, Hu Z. The comparison of ZFNs, TALENs, and SpCas9 by GUIDE-seq in HPV-targeted gene therapy. Mol Ther Nucleic Acids. 2021 Aug 19;26:1466-1478. [CrossRef]

- Ding, W. , Hu, Z., Zhu, D., Jiang, X., Yu Lan and Wang, X., Zhang, C., Wang, L., Ji, T., Li, K., He, D., Xia, X., Liu, D., Zhou, J., Ma, D., & Wang, H. (2014). Zinc Finger Nucleases Targeting the Human Papillomavirus E7 Oncogene Induce E7 Disruption and a Transformed Phenotype in HPV16/18-Positive Cervical Cancer Cells. CLINICAL CANCER RESEARCH, 6503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shankar, S.; et al. (2018). Genome editing of oncogenes with zfns and talens: Caveats in nuclease design. Cancer Cell International, 18(1). [CrossRef]

- Davis, D. , and Stokoe, D. (2010). Zinc finger nucleases as tools to understand and treat human diseases. BMC Medicine, 8(1). [CrossRef]

- Cui, Z. , Liu, H., Zhang, H., Huang, Z., Tian, R., Li, L., Fan, W., Chen, Y., Chen Lijie and Zhang, S., Das, B. C., Severinov, K., Hitzeroth, I. I., Debata, P. R., Jin, Z., Liu, J., Huang, Z., Xie, W., Xie, H., Lang, B., … Hu, Z. (2021). The comparison of ZFNs, TALENs, and SpCas9 by GUIDE-seq in HPV-targeted gene therapy. MOLECULAR THERAPY-NUCLEIC ACIDS, 1478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, D.; et al. (2017). Viral e6 is overexpressed via high viral load in invasive cervical cancer with episomal hpv16. BMC Cancer, 17(1). [CrossRef]

- Bi, Y.; et al. (2014). High-efficiency targeted editing of large viral genomes by rna-guided nucleases. PLoS Pathogens, 10(5), e1004090. [CrossRef]

- Bhowmik, R. , and Chaubey, B. (2022). Crispr/cas9: A tool to eradicate hiv-1. AIDS Research and Therapy, 19(1). [CrossRef]

- Zhen, S. , Lu, J.-J., Wang, L.-J., Sun, X.-M., Zhang, J.-Q., Li, X., Luo, W.-J., & Zhao, L. (2016). In Vitro and In Vivo Synergistic Therapeutic Effect of Cisplatin with Human Papillomavirus16 E6/E7 CRISPR/Cas9 on Cervical Cancer Cell Line. TRANSLATIONAL ONCOLOGY, 9(6), 498–504. [CrossRef]

- Ehrke-Schulz, E. , Heinemann, S., Schulte, L., Schiwon, M., & Ehrhardt, A. (2020). Adenoviral Vectors Armed with PAPILLOMAVIRUs Oncogene Specific CRISPR/Cas9 Kill Human-Papillomavirus-Induced Cervical Cancer Cells. CANCERS. [CrossRef]

- Gao, C. , Wu, P., Yu, L., Liu, L., Liu, H., Tan, X., Wang, L., Huang, X., & Wang, H. (2022). The application of CRISPR/Cas9 system in cervical carcinogenesis. CANCER GENE THERAPY. [CrossRef]

- Ling, K.; et al. (2020). Gene targeting of hpv18 e6 and e7 synchronously by nonviral transfection of crispr/cas9 system in cervical cancer. Human Gene Therapy, 31(5-6), 297-308. [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.; et al. (2024). From bench to bedside: Cutting-edge applications of base editing and prime editing in precision medicine. Journal of Translational Medicine, 22(1). [CrossRef]

- Haddad, C. O.; et al. (2021). Targeting the kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus genome with the crispr-cas9 platform in latently infected cells. Virology Journal, 18(1). [CrossRef]

- Tsuchida, C. A.; et al. (2024). Targeted nonviral delivery of genome editors in vivo. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 121(11). [CrossRef]

- Sinn, P. L.; et al. (2008). Lentivirus vector can be readministered to nasal epithelia without blocking immune responses. Journal of Virology, 82(21), 10684-10692. [CrossRef]

- Zhen, S. , Liu, Y., Lu, J., Tuo, X., Yang, X., Chen, H., Chen, W., & Li, X. (2020). Human Papillomavirus Oncogene Manipulation Using Clustered Regularly Interspersed Short Palindromic Repeats/Cas9 Delivered by pH-Sensitive Cationic Liposomes. HUMAN GENE THERAPY, 31(5–6), 309–324. [CrossRef]

- Excision BioTherapeutics. Clinical trial EBT-101 for HIV CRISPR treatment (NCT05144386). ClinicalTrials.gov. 2022. Available at: https://clinicaltrials. 0514.

- Baba, S. K.; et al. (2025). Human papilloma virus (hpv) mediated cancers: An insightful update. Journal of Translational Medicine, 23(1). [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, E. M. , Kornepati, A. V. R., Goldstein, M., Bogerd, H. P., Poling, B. C., Whisnant, A. W., Kastan, M. B., & Cullen, B. R. (2014). Inactivation of the Human Papillomavirus E6 or E7 Gene in Cervical Carcinoma Cells by Using a Bacterial CRISPR/Cas RNA-Guided Endonuclease. JOURNAL OF VIROLOGY, 88(20), 11965–11972. [CrossRef]

- Jubair, L. , Fallaha, S., & McMillan, N. A. J. (2019). Systemic Delivery of CRISPR/Cas9 Targeting HPV Oncogenes Is Effective at Eliminating Established Tumors. MOLECULAR THERAPY, 27(12), 2091–2099. [CrossRef]

- Khairkhah, N. , Bolhassani, A., Rajaei, F., & Najafipour, R. (2023). Systemic delivery of specific and efficient CRISPR/Cas9 system targeting HPV16 oncogenes using LL-37 antimicrobial peptide in C57BL/6 mice. JOURNAL OF MEDICAL VIROLOGY, 95(7). [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y. , Jiang, H., Wang, T., He, D., Tian Rui and Cui, Z., Tian, X., Gao, Q., Ma, X., Yang, J., Wu, J., Tan, S., Xu, H., Tang Xiongzhi and Wang, Y., Yu, Z., Han, H., Das, B. C., Severinov, K., Hitzeroth, I. I., Debata, P. R., … You, Z. (2020). In vitro and in vivo growth inhibition of human cervical cancer cells via human papillomavirus E6/E7 mRNAs’ cleavage by CRISPR/Cas13a system. ANTIVIRAL RESEARCH. [CrossRef]

- Hu, Z. , Ding, W., Zhu, D., Yu, L., Jiang Xiaohui and Wang, X., Zhang, C., Wang, L., Ji, T., Liu, D., He, D., Xia, X., Zhu, T., Wei, J., Wu, P., Wang, C., Xi, L., Gao, Q., Chen, G., Liu, R., … Wang, H. (2015). TALEN-mediated targeting of HPV oncogenes ameliorates HPV-related cervical malignancy. JOURNAL OF CLINICAL INVESTIGATION, 125(1), 425–436. [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, D. A. , McMillan, N. A. J., & Idris, A. (2022). Genetic deletion of HPV E7 oncogene effectively regresses HPV driven oral squamous carcinoma tumour growth. BIOMEDICINE & PHARMACOTHERAPY, 155. [CrossRef]

- Hu, Z. , Yu, L., Zhu, D., Ding, W., Wang Xiaoli and Zhang, C., Wang, L., Jiang, X., Shen Hui and He, D., Li, K., Xi, L., Ma, D., & Wang, H. (2014). Disruption of HPV16-E7 by CRISPR/Cas System Induces Apoptosis and Growth Inhibition in HPV16 Positive Human Cervical Cancer Cells. BIOMED RESEARCH INTERNATIONAL, 2014. [CrossRef]

- McLaughlin-Drubin ME, Münger K. Oncogenic activities of human papillomaviruses. Virus Res. 2009 Aug;143(2):195-208. [CrossRef]

- Liz, T. Tony, Andrea Stabile, Marc P. Schauer, Michael Hudecek, Justus Weber; CAR-T Cell Therapy for Solid Tumors. Transfus Med Hemother ; 52 (1): 96–108. 11 February. [CrossRef]

- Xinqiao Hospital of Chongqing. HPV-E6-Specific Anti-PD1 TCR-T Cells in the Treatment of HPV-Positive NHSCC or Cervical Cancer (NCT03578406). ClinicalTrials.gov.2019. Available at: https://clinicaltrials. 0357.

- Li, X.; et al. (2021). Crispr/cas9 nanoeditor of double knockout large fragments of e6 and e7 oncogenes for reversing drugs resistance in cervical cancer. Journal of Nanobiotechnology, 19(1). [CrossRef]

- Ghanaat M, Goradel NH, Arashkia A, Ebrahimi N, Ghorghanlu S, Malekshahi ZV, Fattahi E, Negahdari B, Kaboosi H. Virus against virus: strategies for using adenovirus vectors in the treatment of HPV-induced cervical cancer. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2021 Dec;42(12):1981-1990. [CrossRef]

- Hsu, D. S. , Kornepati, A. V. R., Glover, W., Kennedy, E. M., & Cullen, B. R. (2018). Targeting HPV16 DNA using CRISPR/Cas inhibits anal cancer growth in vivo. FUTURE VIROLOGY, 13(7), 475–482. [CrossRef]

- First Affiliated Hospital, Sun Yat-Sen University. A Safety and Efficacy Study of TALEN and CRISPR/Cas9 in the Treatment of HPV-related Cervical Intraepithelial Neoplasia (NCT03057912). ClinicalTrials.gov. 2017. Available at: https://clinicaltrials. 0305.

- Sichuan University. PD-1 Knockout Engineered T Cells for Metastatic Non-small Cell Lung Cancer (NCT02793856). ClinicalTrials.gov.2021. Available at: https://clinicaltrials. 0279.

- Inovio Pharmaceuticals. Phase I of Human Papillomavirus (HPV) DNA Plasmid (VGX-3100) + Electroporation for CIN 2 or 3 (NCT00685412). ClinicalTrials.gov.2017. Available at: https://clinicaltrials. 0068.

- Inovio Pharmaceuticals. A Study of VGX-3100 DNA Vaccine With Electroporation in Patients With Cervical Intraepithelial Neoplasia Grade 2/3 or 3 (HPV-003) (NCT01304524). ClinicalTrials.gov. 2018. Available at: https://clinicaltrials. 0130.

- Inovio Pharmaceuticals. REVEAL 1 (Evaluation of VGX-3100 and Electroporation for the Treatment of Cervical HSIL) (NCT03185013). ClinicalTrials.gov. 2023. Available at: https://clinicaltrials. 0318.

- Inovio Pharmaceuticals. REVEAL 2 Trial (Evaluation of VGX-3100 and Electroporation for the Treatment of Cervical HSIL) (NCT03721978). ClinicalTrials.gov. 2024. Available at: https://clinicaltrials. 0372.

- Inovio Pharmaceuticals. Evaluation of VGX-3100 and Electroporation Alone or in Combination With Imiquimod for the Treatment of HPV-16 and/or HPV-18 Related Vulvar HSIL (Also Referred as: VIN 2 or VIN 3) (NCT03180684). ClinicalTrials.gov. 2023. Available at: https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT03180684AIDS Malignancy Consortium.

- VGX-3100 and Electroporation in Treating Patients With HIV-Positive High-Grade Anal Lesions (NCT03603808). ClinicalTrials.gov. 2025. Available at: https://clinicaltrials. 0360.

- Inovio Pharmaceuticals. VGX-3100 Delivered Intramuscularly (IM) Followed by Electroporation (EP) for the Treatment of HPV-16 and/or HPV-18 Related Anal or Anal/Peri-Anal, High Grade Squamous Intraepithelial Lesion (HSIL) in Individuals Seronegative for Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV)-1/2 (NCT03499795). ClinicalTrials.gov. 2023. Available at: https://www.clinicaltrials. 0349.

- Kermanshahi, A. Z.; et al. (2025). Hpv-driven cancers: A looming threat and the potential of crispr/cas9 for targeted therapy. Virology Journal, 22(1). [CrossRef]

- Wiik, J.; et al. (2022). Associations between cervical intraepithelial neoplasia during pregnancy, previous excisional treatment, cone-length and preterm delivery: A register-based study from western sweden. BMC Medicine, 20(1). [CrossRef]

- Zhen, S. , Chen, H., Lu, J., Yang, X., Tuo, X., Chang, S., Tian, Y., & Li, X. (2023). Intravaginal delivery for CRISPR-Cas9 technology: For example, the treatment of HPV infection. Journal of Medical Virology, 8552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, W. , Cai, W., & Wang, H. (2024). P53 and pRB induction improves response to radiation therapy in HPV-positive laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma. CLINICS, 79. [CrossRef]

- Inturi, R. , & Jemth, P. (2021). CRISPR/Cas9-based inactivation of human papillomavirus oncogenes E6 or E7 induces senescence in cervical cancer cells. VIROLOGY, 562, 92–102. [CrossRef]

- Chung, H. C. , Ros, W., Delord, J.-P., Perets, R., Italiano, A., Shapira-Frommer, R., Manzuk, L., Piha-Paul, S. A., Xu, L., Zeigenfuss, S., Pruitt, S. K., & Leary, A. (2019). Efficacy and Safety of Pembrolizumab in Previously Treated Advanced Cervical Cancer: Results From the Phase II KEYNOTE-158 Study. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 37(17), 1470–1478. [CrossRef]

- Doran, S. L.; et al. (2019). T-cell receptor gene therapy for human papillomavirus–associated epithelial cancers: A first-in-human, phase i/ii study. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 37(30), 2759-2768. [CrossRef]

- Liu, N.; et al. (2025). Nanomaterials-driven in situ vaccination: A novel frontier in tumor immunotherapy. Journal of Hematology & Oncology, 18(1). [CrossRef]

- Zheng, S.; et al. (2024). Tumor battlefield within inflamed, excluded or desert immune phenotypes: The mechanisms and strategies. Experimental Hematology & Oncology, 13(1). [CrossRef]

- García, E. , Ayoub, N., and Tewari, K. S. (2024). Recent breakthroughs in the management of locally advanced and recurrent/metastatic cervical cancer. Journal of Gynecologic Oncology, 35(1). [CrossRef]

- Qi, L.; et al. (2019). Advances in toxicological research of the anticancer drug cisplatin. Chemical Research in Toxicology, 32(8), 1469-1486. [CrossRef]

- Viswanathan, A. N.; et al. (2014). Complications of pelvic radiation in patients treated for gynecologic malignancies. Cancer, 120(24), 3870-3883. [CrossRef]

- Coventry, B. J. (2019). Therapeutic vaccination immunomodulation: Forming the basis of all cancer immunotherapy. Therapeutic Advances in Vaccines and Immunotherapy, 7. [CrossRef]

- Zolfi, E.; et al. (2025). A review of the carcinogenic potential of human papillomavirus (hpv) in urological cancers. Virology Journal, 22(1). [CrossRef]

- Caley, A.; et al. (2014). Multicentric human papillomavirus–associated head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Head & Neck, 37(2), 202-208. [CrossRef]

- Khanna, L.; et al. (2021). Second malignancies after radiation therapy: Update on pathogenesis and cross-sectional imaging findings. RadioGraphics, 41(3), 876-894. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, P. , Liu, W., Cheng, Y., & Qian, D. (2021). Nanoparticle-based applications for cervical cancer treatment in drug delivery, gene editing, and therapeutic cancer vaccines. WIREs Nanomedicine and Nanobiotechnology, 13(5). [CrossRef]

- Calderón, M. , and Hedtrich, S. (2021). The delivery challenge of genome editing in human epithelia. Advanced Healthcare Materials, 10(19). [CrossRef]

- Mutombo, A. B.; et al. (2019). Efficacy of commercially available biological agents for the topical treatment of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia: A systematic review. Systematic Reviews, 8(1). [CrossRef]

- Bahrami, K.; et al. (2023). Design of nanoparticle-based systems for the systemic delivery of chemotherapeutics: Alternative potential routes via sublingual and buccal administration for systemic drug delivery. Drug Delivery and Translational Research, 14(5), 1173-1188. [CrossRef]

- Kotterman, M. A. , Chalberg, T. W., and Schaffer, D. V. (2015). Viral vectors for gene therapy: Translational and clinical outlook. Annual Review of Biomedical Engineering, 17(1), 63-89. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, D. , Shen, H., Tan, S., Hu, Z., Wang Liming and Yu, L., Tian, X., Ding, W., Ren, C., Gao Chun and Cheng, J., Deng, M., Liu, R., Hu, J., Xi Ling and Wu, P., Zhang, Z., Ma, D., & Wang, H. (2018). Nanoparticles Based on Poly (β-Amino Ester) and HPV16-Targeting CRISPR/shRNA as Potential Drugs for HPV16-Related Cervical Malignancy. MOLECULAR THERAPY, 26(10), 2443–2455. [CrossRef]

- Gao, X. , Jin, Z., Tan, X., Zhang, C., Zou, C., Zhang, W., Ding, J., Das, B. C., Severinov, K., Hitzeroth, I. I., Debata, P. R., He, D., Ma, X., Tian, X., Gao, Q., Wu, J., Tian, R., Cui, Z., Fan, W., … Hu, Z. (2020). Hyperbranched poly(β-amino ester) based polyplex nanopaticles for delivery of CRISPR/Cas9 system and treatment of HPV infection associated cervical cancer. JOURNAL OF CONTROLLED RELEASE, 321, 654–668. [CrossRef]

- Xiong, J. , Tan, S., Yu, L., Shen, H., Qu Shen and Zhang, C., Ren, C., Zhu, D., & Wang, H. (2021). E7-Targeted Nanotherapeutics for Key HPV Afflicted Cervical Lesions by Employing CRISPR/ Cas9 and Poly (Beta-Amino Ester). INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF NANOMEDICINE, 16, 7609–7622. [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; et al. (2022). Efficient c-to-g base editing with improved target compatibility using engineered deaminase–ncas9 fusions. The CRISPR Journal, 5(3), 389-396. [CrossRef]

- Wilbie, D. , Walther, J., and Mastrobattista, E. (2019). Delivery aspects of crispr/cas for in vivo genome editing. Accounts of Chemical Research, 52(6), 1555-1564. [CrossRef]

- Mingozzi, F. , and High, K. A. (2017). Overcoming the host immune response to adeno-associated virus gene delivery vectors: The race between clearance, tolerance, neutralization, and escape. Annual Review of Virology, 4(1), 511-534. [CrossRef]

- Cencic, R.; et al. (2014). Protospacer adjacent motif (pam)-distal sequences engage crispr cas9 dna target cleavage. PLoS ONE, 9(10), e109213. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; et al. (2024). A multiplex rpa-crispr/cas12a-based poct technique and its application in human papillomavirus (hpv) typing assay. Cellular & Molecular Biology Letters, 29(1). [CrossRef]

- Mills, C.; et al. (2022). A novel crispr interference effector enabling functional gene characterization with synthetic guide rnas. The CRISPR Journal, 5(6), 769-786. [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; et al. (2025). The relationship between the eradication of helicobacter pylori and the occurrence of stomach cancer: An updated meta-analysis and systemic review. BMC Gastroenterology, 25(1). [CrossRef]

- Hu, Z. , Liu, W., Liu, J., Zhou, H., Sun, C., Tian, C., Guo, X., Zhu, C., Shao, M., Wang, S., Wei, L., Liu, M., Li Shuzhen and Wang, J., Xu, H., Zhu, W., Li, X., & Li, J. (2024). The anti-tumor efficacy of a recombinant oncolytic herpes simplex virus mediated CRISPR/Cas9 delivery targeting in HPV16-positive cervical cancer. ANTIVIRAL RESEARCH, 232. [CrossRef]