Submitted:

01 August 2025

Posted:

05 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

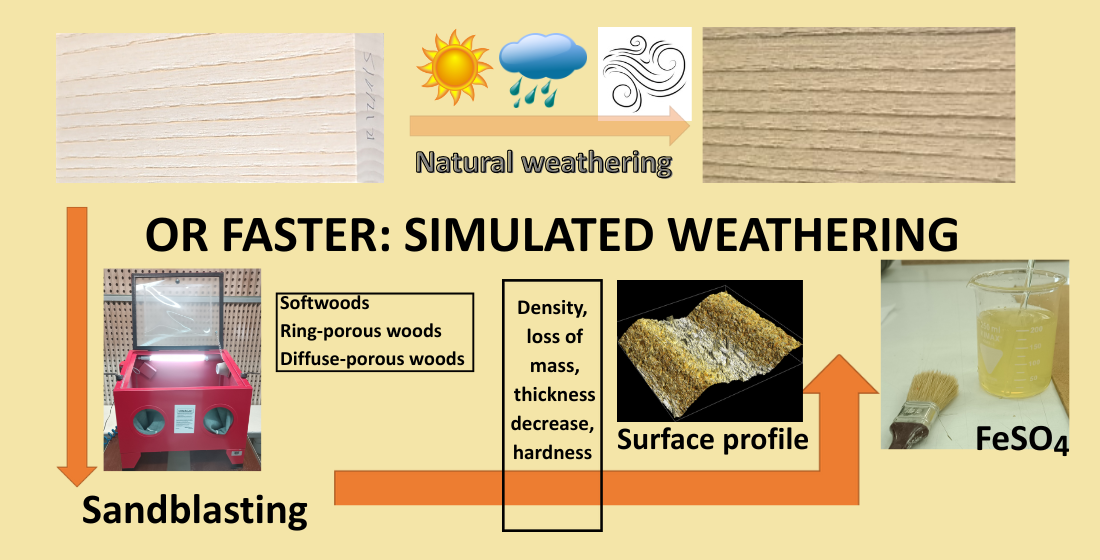

2. Materials and Methods

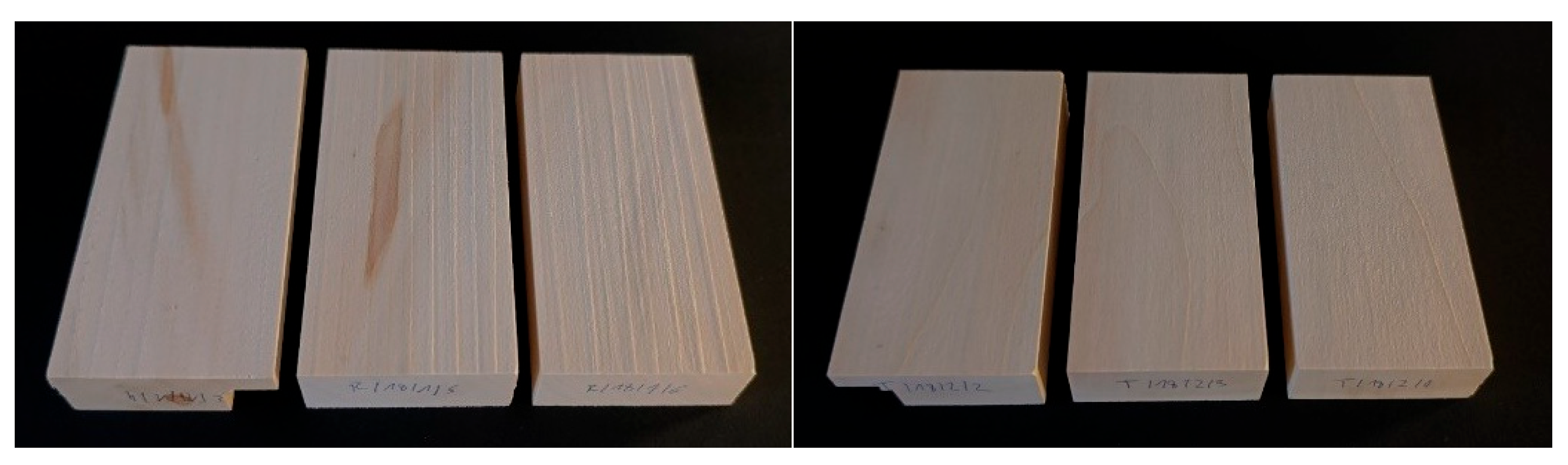

2.1. Materials

2.2. Sandblasting and Greying

2.3. Characterisation and Analyses

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

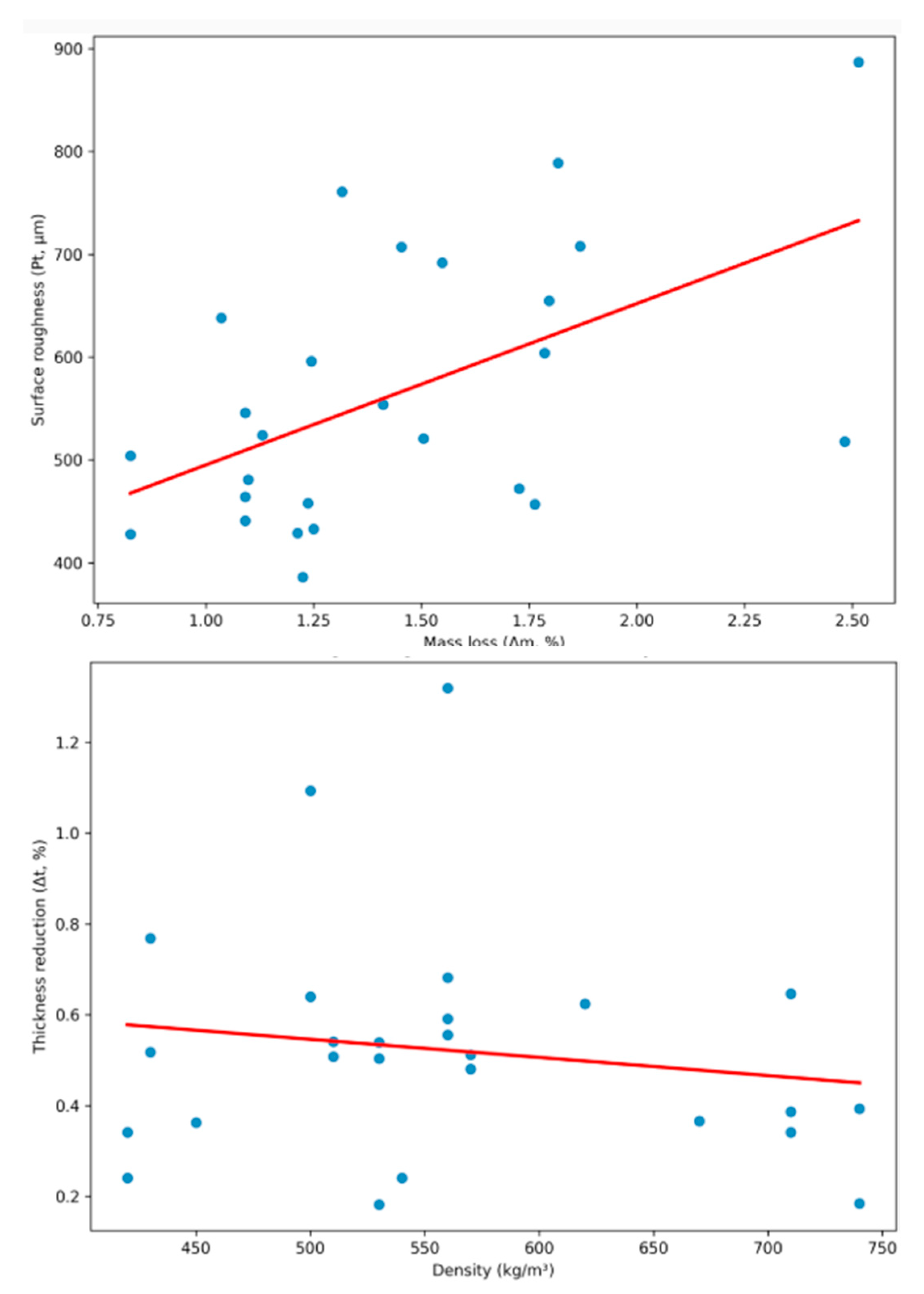

3.1. Sandblasting Results

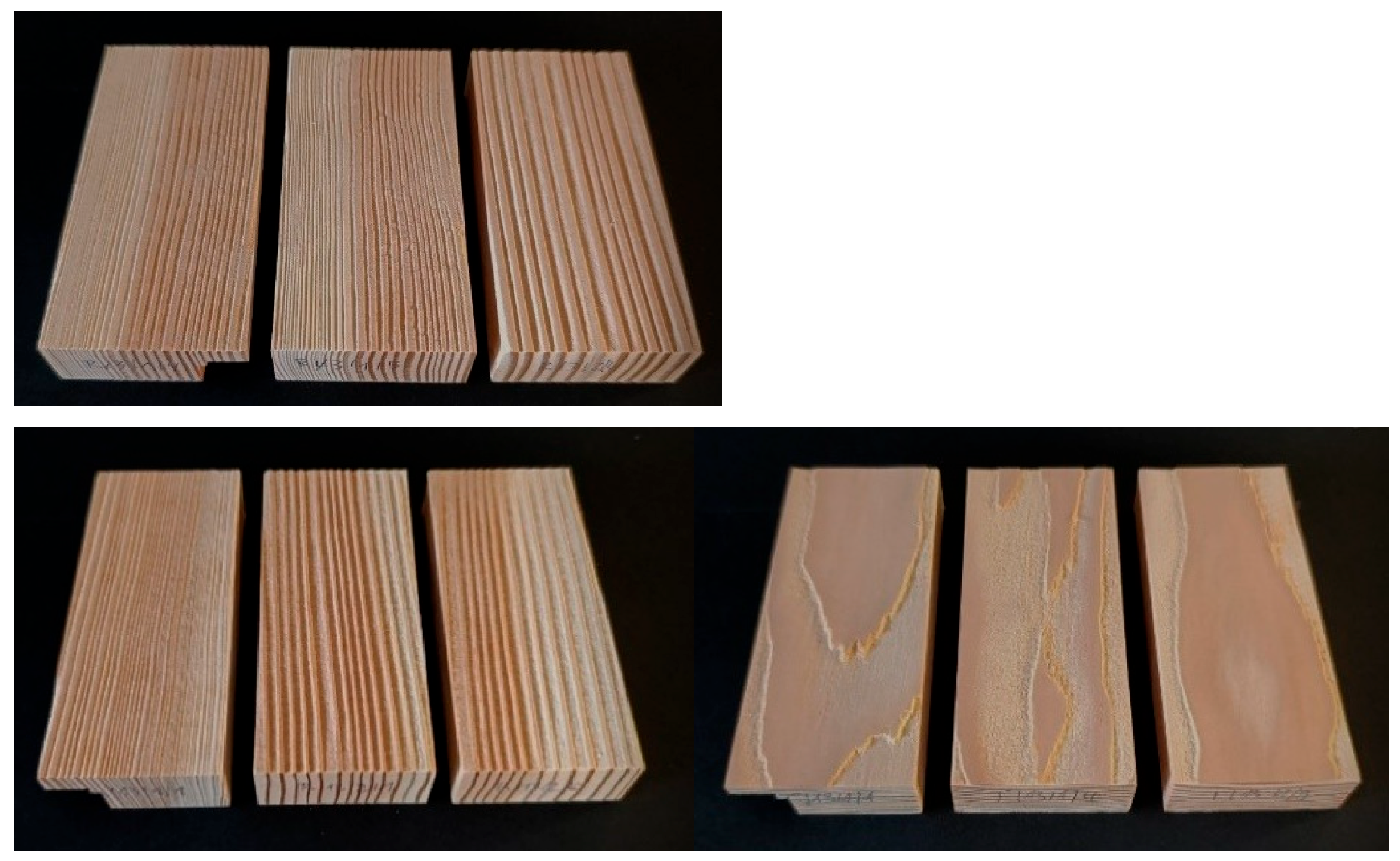

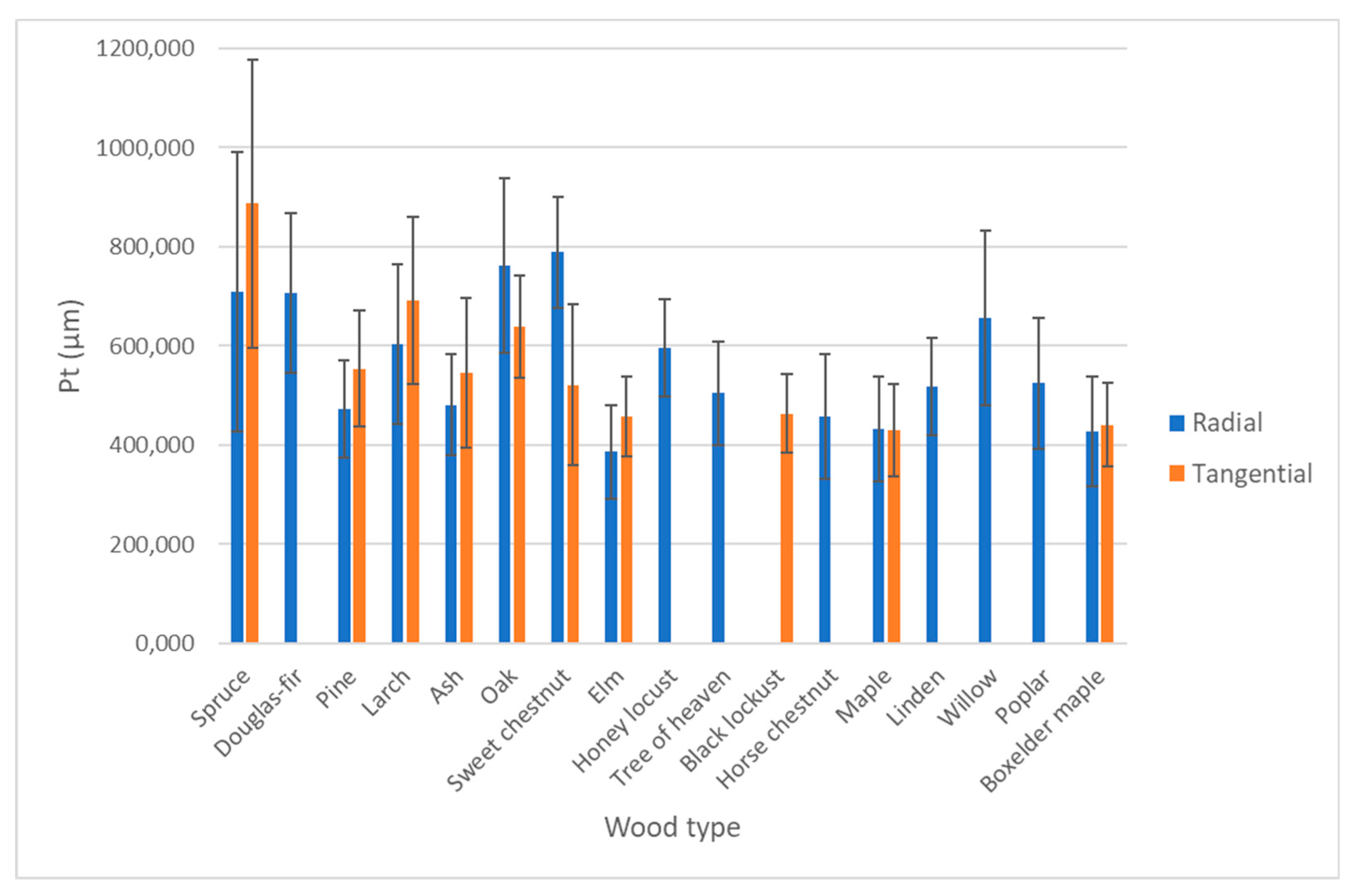

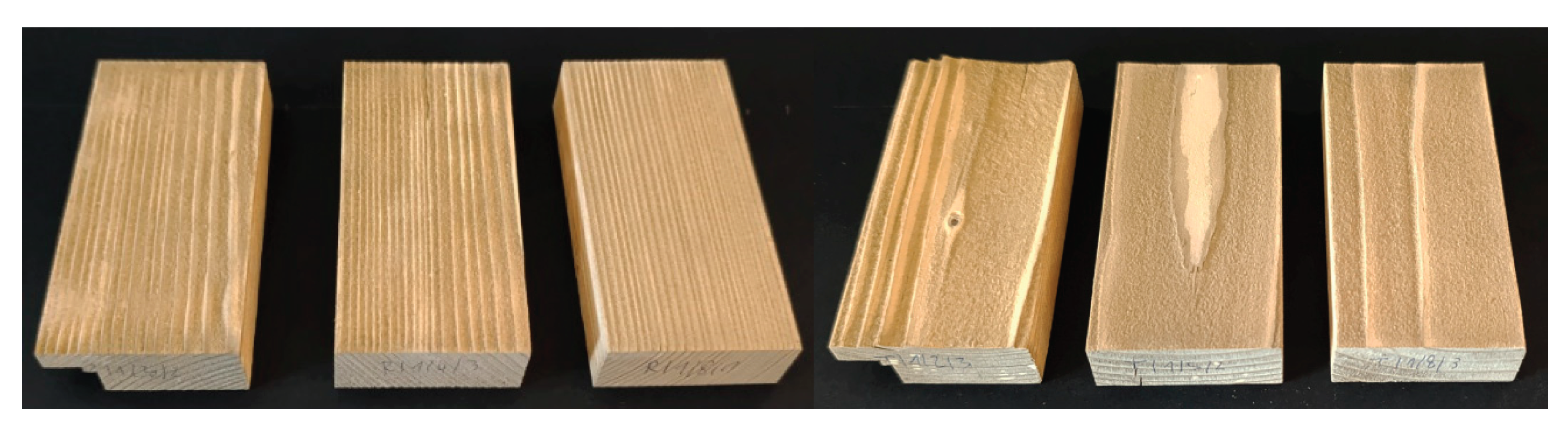

3.1.1. Visual Appearance and Profiles of Sandblasted Surfaces

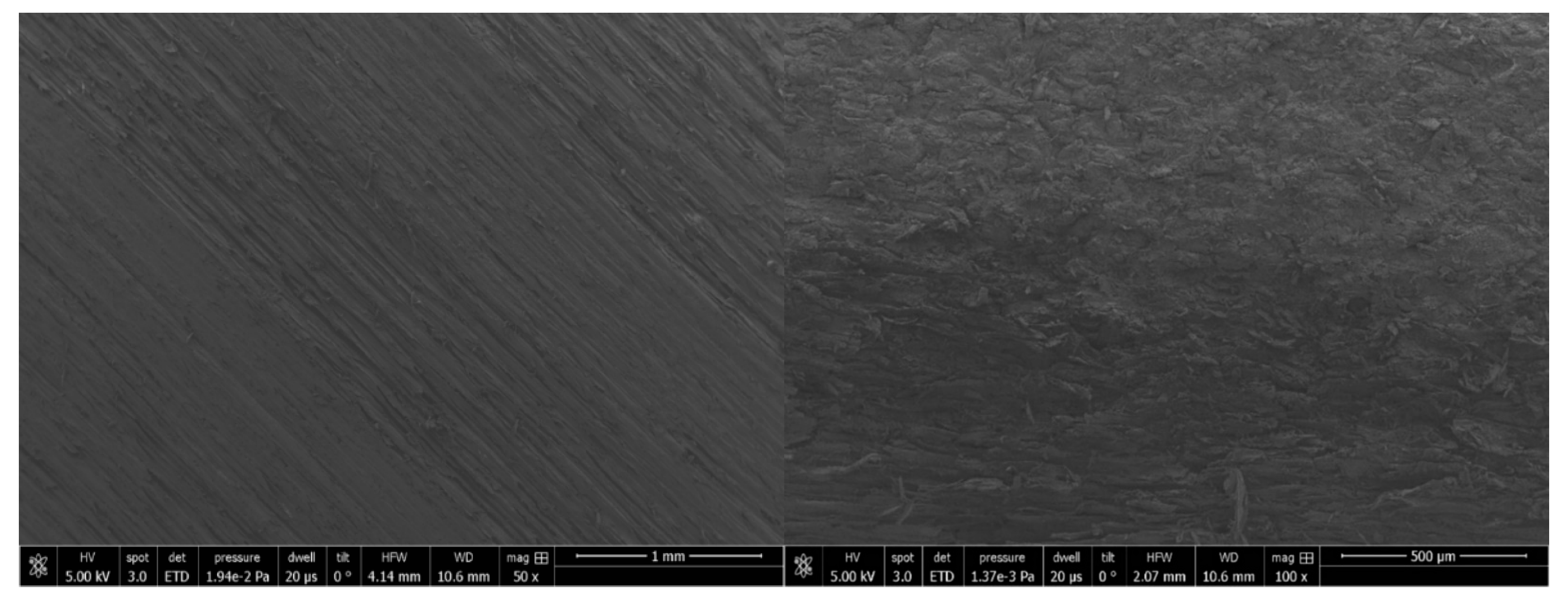

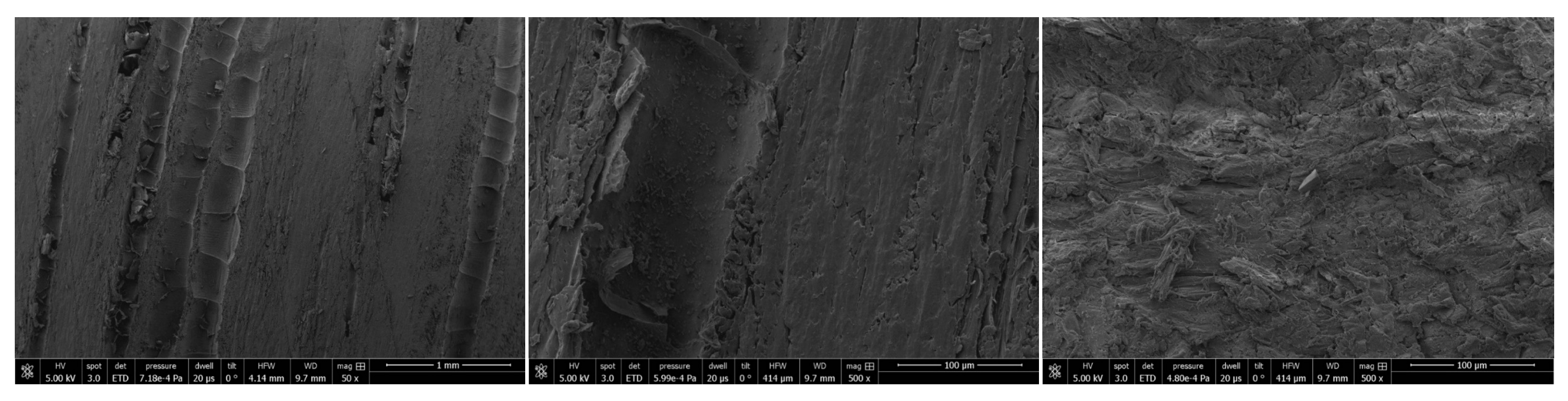

3.1.2. SEM Images of Spruce and Oak Wood Samples

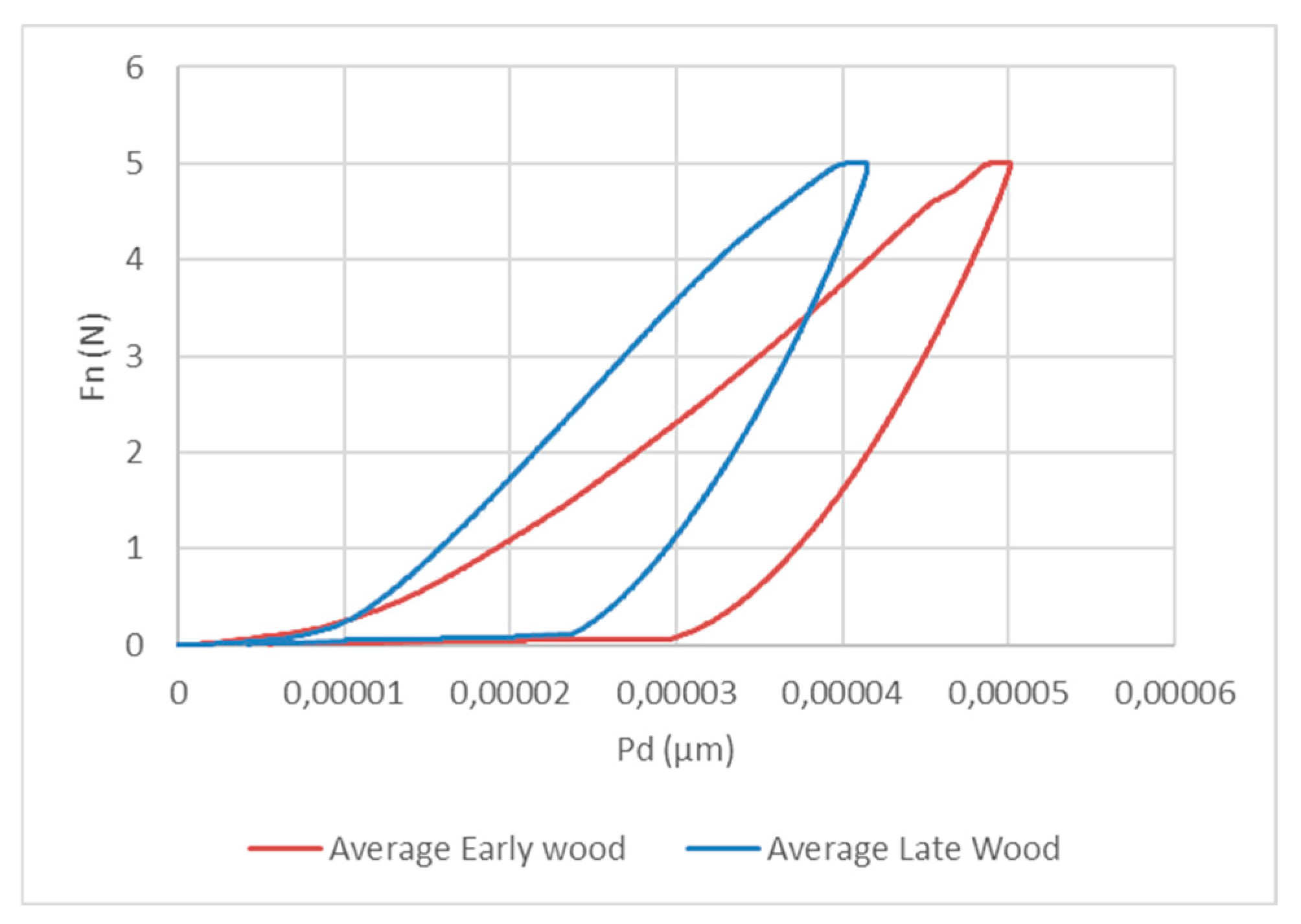

3.1.3. Indentation Hardness and Reduction of Mass and Thickness by Sandblasting

| Sample | Radial surface | Tangential surface | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Early wood | Late wood | Early wood | Late wood | ||||||

| HIT | EIT | HIT | EIT | HIT | EIT | HIT | EIT | ||

| Spruce | 165(27) | 1.98(0.16) | 229(58) | 2.51(0.32) | 62.5(43) | 3.27(0.81) | 183(39) | 1.88(0.30) | |

| Douglas-fir | 94.9(6) | 1.72(0.08) | 424(147) | 4.91(1.01) | |||||

| Pine | 140(57) | 1.94(0.51) | 275(67) | 2.78(0.53) | 210(110) | 2.49(0.77) | 379(148) | 3.35(1.00) | |

| Larch | 283(81) | 3.47(0.54) | 547(170) | 5.82(0.95) | 329(132) | 6.30(2.19) | 689(42) | 9.29(1.67) | |

| Ash | 389(65) | 4.68(0.34) | 414(203) | 6.18(4.2) | 448(97) | 5.04(0.28) | 476(161) | 5.60(1.78) | |

| Oak | 272(112) | 3.42(1.06) | 488(116) | 4.04(0.69) | 776(125) | 8.11(1.18) | 949(151) | 10.8(1.20) | |

| Sweet chestnut | 205(84) | 3.02(1.46) | 374(48) | 3.31(0.81) | 208(38) | 3.59(0.55) | 458(84) | 5.41(0.45) | |

| Elm | 480(136) | 7.63(0.67) | 661(370) | 11.2(2.10) | 409(71) | 5.31(0.23) | 778(249) | 9.53(0.71) | |

| Honey locust | 504(142) | 6.11(0.92) | 748(69) | 9.30(0.71) | |||||

| Tree of heaven | 353(47) | 5.49(0.48) | 366(134) | 4.81(0.74) | |||||

| Black locust | 419(88) | 6.13(1.32) | 518(209) | 6.69(1.34) | |||||

| Horse chestnut | 225(30) | 3.07(0.31) | 263(75) | 3.22(0.32) | |||||

| Maple | 237(117) | 2.94(0.79) | 366(45) | 4.50(0.52) | 519(82) | 5.14(0.31) | 838(98) | 6.89(0.74) | |

| Linden | 98(40) | 2.79(2.04) | 142(48) | 1.78(0.25) | 113(53) | 1.73(0.37) | 184(15) | 2.10(0.33) | |

| Willow | 136(72) | 1.96(0.84) | 162(23) | 2.63(0.30) | |||||

| Poplar | 213(106) | 2.62(0.96) | 367(82) | 3.67(0.47) | |||||

| Boxelder maple | 289(45) | 4.88(0.40) | 415(134) | 6.10(1.06) | 860(65) | 10.3(0.67) | 876(152) | 9.65(1.70) | |

| Wood | Orientation | Density (g/cm3)1 | Mass loss (%) | Decrease of thickness (%) | ΔHIT2 (MPa) | Pt (µm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spruce | radial | 430 [35] | 1.868 | 0.518 | 64 | 708 |

| tangential | 2.514 | 0.768 | 120 | 887 | ||

| Douglas-fir | radial | 530 [35] | 1.454 | 0.504 | 329 | 707 |

| Pine | data | 510 [35] | 1.727 | 0.541 | 135 | 472 |

| data | 1.411 | 0.508 | 360 | 554 | ||

| Larch | radial | 530 [35] | 1.786 | 0.539 | 264 | 604 |

| tangential | 1.548 | 0.182 | 360 | 692 | ||

| Ash | radial | 710 [35] | 1.098 | 0.646 | 25 | 481 |

| tangential | 1.091 | 0.387 | 28 | 546 | ||

| Oak | radial | 740 [35] | 1.316 | 0.393 | 216 | 761 |

| tangential | 1.036 | 0.185 | 173 | 638 | ||

| Sweet chestnut | radial | 560 [35] | 1.817 | 0.682 | 169 | 789 |

| tangential | 1.505 | 0.556 | 250 | 521 | ||

| Elm | radial | 570 [35] | 1.225 | 0.481 | 181 | 386 |

| tangential | 1.237 | 0.512 | 369 | 458 | ||

| Honey locust | radial | 670 [35] | 1.245 | 0.366 | 244 | 596 |

| Tree of heaven | radial | 540 [36] | 0.825 | 0.241 | 13 | 504 |

| Black locust | tangential | 710 [36] | 1.091 | 0.341 | 99 | 464 |

| Horse chestnut | radial | 500 [35] | 1.763 | 1.093 | 38 | 457 |

| Maple | radial | 620 [35] | 1.250 | 0.624 | 129 | 433 |

| tangential | 1.213 | 0.591 | 319 | 429 | ||

| Linden | radial | 560 [35] | 2.482 | 1.319 | 44 | 518 |

| tangential | 1.548 | 0.905 | 71 | 3 | ||

| Willow | radial | 500 [35] | 1.796 | 0.640 | 26 | 655 |

| Poplar | radial | 450 [35] | 1.131 | 0.363 | 154 | 524 |

| Boxelder maple | radial | 420 [36] | 0.825 | 0.241 | 126 | 428 |

| tangential | 1.091 | 0.341 | 16 | 441 |

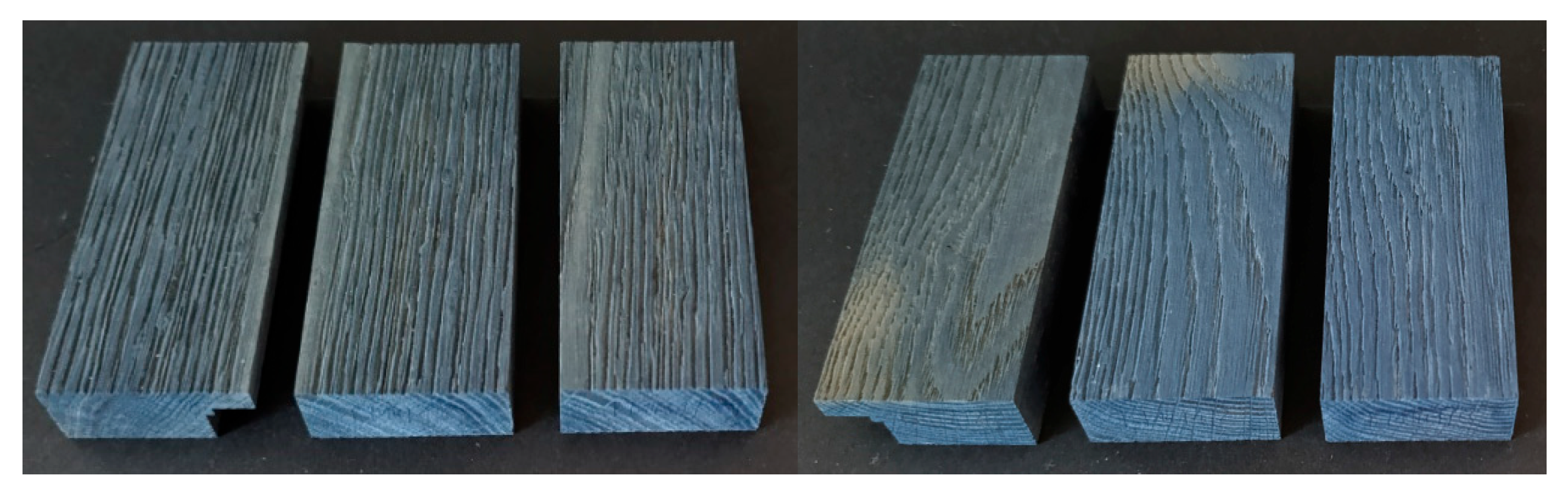

3.2. Greying

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| R | Radial surface |

| T | Tangential surface |

| A | Alien invasive species |

| Pt | Surface profile parameter: the total height of the profile |

| |r| | the average absolute correlation (mean |r|) |

| HIT | Indentation hardness |

| EIT | Indentation modulus |

| ΔHIT | Difference of indentation hardnesses of late and early wood |

References

- Kropat, M.; Hubbe, M.A.; Laleicke, F. Natural, Accelerated, and Simulated Weathering of Wood: A Review. BioRes 2020, 15, 9998–10062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Gao, Y.; Duan, H.; Xu, X. Progress in the Experimental Design and Performance Characterization of Artificial Accelerated Photodegradation of Wood. Coatings 2024, 14, 1600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kus Sahin, C.; Topay, M.; Ali Var, A. A Study on Suitability of Some Wood Species for Landscape Applications: Surface Color, Hardness and Roughness Changes at Outdoor Conditions. Wood Res. 2020, 65, 395–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jirouš-Rajković, V.; Miklečić, J. Enhancing Weathering Resistance of Wood—A Review. Polymers 2021, 13, 1980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Windt, I.; Van Den Bulcke, J.; Wuijtens, I.; Coppens, H.; Van Acker, J. Outdoor Weathering Performance Parameters of Exterior Wood Coating Systems on Tropical Hardwood Substrates. Eur. J. Wood Prod. 2014, 72, 261–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mi, X.; Li, Y.; Qin, X.; Li, J. Effects of Natural Weathering on Aged Wood from Historic Wooden Building: Diagnosis of the Oxidative Degradation. Herit Sci 2023, 11, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cogulet, A.; Blanchet, P.; Landry, V. The Multifactorial Aspect of Wood Weathering: A Review Based on a Holistic Approach of Wood Degradation Protected by Clear Coating. BioResources 2017, 13, 2116–2138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; Pan, X.; Xu, M.; Yang, W.; Wang, J.; Zhuang, X. Surface Chemical Changes Analysis of UV-Light Irradiated Moso Bamboo (Phyllostachys Pubescens Mazel). R.Soc.Open Sci 2018, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, P.D. Weathering of Wood.; Canadian Wood Preservation Association, 36th Annual Meeting: Ottawa, Ontario, October 27 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Kubovský, I.; Oberhofnerová, E.; Kačík, F.; Pánek, M. Surface Changes of Selected Hardwoods Due to Weather Conditions. Forests 2018, 9, 557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, C.; Kymäläinen, M.; Rautkari, L. Review of the Use of Solid Wood as an External Cladding Material in the Built Environment. J Mater Sci 2022, 57, 9031–9076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, T.; Qin, Z.; Luan, R. Discoloration of Heat-Treated and Untreated Red Alder Wood in Outdoor, Transitional and Indoor Space. Wood Material Science & Engineering 2024, 19, 589–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, R.S.; Knaebe, M.T.; Feist, W.C. EROSION RATES OF WOOD DURING NATURAL WEATHERING. PART 11. EARLYWOOD AND LATEWOOD EROSION RATES. Wood Fiber Sci. 33, 43–49.

- Lemaster, R.L.; Shih, A.J.; Yu, Z. Blasting and Erosion Wear of Wood Using Sodium Bicarbonate and Plastic Media. Forest Prod J 2005, 55, 59–64. [Google Scholar]

- Jankowska, A.; Kwiatkowski, A. Effectiveness of European Oak Wood Staining with Iron (II) Sulphate during Natural Weathering. Maderas, Cienc. Tecnol. 2022, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dagher, R.; Stevanovic, T.; Landry, V. Wood Color Modification with Iron Salts Aqueous Solutions: Effect on Wood Grain Contrast and Surface Roughness. Holzforschung 2023, 77, 356–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hundhausen, U.; Mai, C.; Slabohm, M.; Gschweidl, F.; Schwarzenbrunner, R. The Staining Effect of Iron (II) Sulfate on Nine Different Wooden Substrates. Forests 2020, 11, 658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lesar, B.; Humar, M. Performance of Iron(II)-Sulphate-Treated Norway Spruce and Siberian Larch in Laboratory and Outdoor Tests. Forests 2022, 13, 1497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humar, M.; Osvald, F.; Lesar, B. Colour Changes of Weathered Wood Surfaces Before and After Treatment with Iron (II) Sulphate. Drv. ind. (Online) 2024, 75, 5–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Copilot (GPT-4, July 2025 Version). Available online: https://copilot.microsoft.com (accessed on 28 July 2025).

- Virtanen, P.; Gommers, R.; Oliphant, T.E.; Haberland, M.; Reddy, T.; Cournapeau, D.; Burovski, E.; Peterson, P.; Weckesser, W.; Bright, J.; et al. SciPy 1.0: Fundamental Algorithms for Scientific Computing in Python. Nat Methods 2020, 17, 261–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKinney, W. Data Structures for Statistical Computing in Python. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 9th Python in Science Conference (SciPy 2010).

- Waskom, M. Seaborn: Statistical Data Visualization. JOSS 2021, 6, 3021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bobbit, Z. How to Report Pearson’s r in APA Format (With Examples) Available online:. Available online: https://www.statology.org/how-to-report-pearson-correlation/ (accessed on 28 July 2025).

- Hunter, J.D. Matplotlib: A 2D Graphics Environment. Comput. Sci. Eng. 2007, 9, 90–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surface Roughness Parameters Available online:. Available online: https://www.keyence.eu/ss/products/microscope/roughness/line/parameters.jsp (accessed on 28 July 2025).

- Anton Paar GmbH Software Reference Guide: Indentation; From Indentation Software Version 10 for 64 Bits Windows® 10.

- Broitman, E. Indentation Hardness Measurements at Macro-, Micro-, and Nanoscale: A Critical Overview. Tribol Lett 2017, 65, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forest Products Laboratory. Wood Handbook—Wood as an Engineering Material. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Forest Products Laboratory: Madison, Wisconsin, 2021.

- Petric, M.; Levanic, J.; Paul, D. Investigations of Surface-Treated Wood by a Micro-Indentation Approach: A Short Review and a Case Study. Bulletin of the Transilvania University of Brașov, Series II: Forestry, Wood Industry, Agricultural Food Engineering 2023, 177–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyurin, A.I.; Korenkov, V.V.; Gusev, A.A.; Vasyukova, I.A.; Yunak, M.A. Comparison of the Viscoelastic Properties and Plasticity of Early and Late Wood of Pine and Spruce by Continuous Stiffness Measurement during Nanoindentation. Nanotechnol Russia 2024, 19, 116–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golovin, Yu.I.; Tyurin, A.I.; Gusev, A.A.; Matveev, S.M.; Golovin, D.Yu.; Samodurov, A.A.; Vasyukova, I.A.; Yunak, M.A.; Kolesnikov, E.A.; Zakharova, O.V. Scanning Nanoindentation as an Instrument of Studying Local Mechanical Properties Distribution in Wood and a New Technique for Dendrochronology. Tech. Phys. 2023, 68, S156–S168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirata, S.; Ohta, M.; Honma, Y. Hardness Distribution on Wood Surface. J Wood Sci 2001, 47, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, H.; Jiang, J.; Zhan, T.; Lu, J. Influence of Density and Equilibrium Moisture Content on the Hardness Anisotropy of Wood. Forest Products Journal 2016, 66, 443–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Engineering ToolBox. Available online: https://www.engineeringtoolbox.com/wood-density-d_40.html (accessed on 28 July 2025).

- Nowak, D.J. Understanding I-Tree: Summary of Programs and Methods – Appendix 11: Wood Density Values; U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Northern Research Station: Madison, Wisconsin, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Laskowska, A.; Piwek, A.; Lipska, K.; Kłosińska, T.; Rybak, K.; Boruszewski, P. Evaluation of the Selected Surface Properties of European Oak and Norway Maple Wood Sanded with Aluminum Oxide Sandpapers of Different Grits. Coatings 2025, 15, 813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).