Submitted:

01 August 2025

Posted:

06 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Edible Oils

2.1. Source and Composition

2.2. Classification of Fats and Oils

3. Vegetable Oils

3.1. Components of Vegetable Oils

3.2. Purification of Vegetable Oils

3.2.1. Traditional Oil Refining

3.2.2. Industrial Oil Refining

- Physical Refining Method

- 2.

- Chemical Refining Method

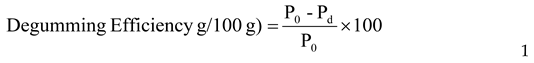

Degumming

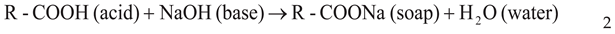

Neutralization/ Deacidification

Washing and Drying

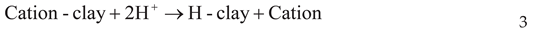

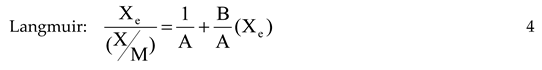

Bleaching/ Decolorization

Deodorization

4. Conclusion

References

- Gunstone, F.D. (2011). Vegetable Oils in Food Technology: Composition, Properties and Uses, Second Edition, Wiley-Blackwell, Hoboken, New Jersey, USA.

- Gunstone, F. (2009). The Chemistry of Oils and Fats: Sources, Composition, Properties and Uses. Wiley-Blackwell Publishers.

- Dijkstra, A.J. Encyclopedia of Food and Health || Vegetable Oils: Composition and Analysis. Elsevier Publishers 2016, 357–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bockisch, M. Fats and Oils Handbook; AOCS Press: Urbana, Illinois, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Mielke, T. (2018). World Markets for Vegetable Oils and Animal Fats. In: Kaltschmitt, M.; Neuling, U. (eds) Biokerosene. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg. [CrossRef]

- Gharby, S. Refining Vegetable Oils: Chemical and Physical Refining, The Scientific World Journal 2022, 2022, 1–10. [CrossRef]

- Oboulbiga, Y.; Sawadogo-Lingani, H.; Traoré, Y. Evaluation of traditional processing techniques of groundnut oil in Burkina Faso. African Journal of Food Science 2021, 15, 293–301. [Google Scholar]

- Adeyeye, S.A.O.; Oyewole, O.B.; Obadina, A.O.; Omemu, A.M.; Olasupo, N.A. Microbiological safety and quality of traditional oils in Nigeria. Food Control 2020, 110, 107024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Z.; Liu, Z.; Ma, Y. Advances in edible oil refining technology: A review. Journal of Oleo Science 2021, 70, 133–145. [Google Scholar]

- Mba, O.I.; Dumont, M.J.; Ngadi, M. Palm oil: Processing, characterization and utilization in the food industry, A review. Food Bioscience 2015, 10, 26–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fashina, P.; Adeleke, T.; Taiwo, W. Food Processing Technology: Principles and Practice, 3rd Edition ed; Woodhead Publishers: Cambridge, Cambridgeshire, United Kingdom, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Haro, A.; Tetteh, G.A.; Fiawoto, A.M. Traditional edible oil production in sub-Saharan Africa: A review of processing techniques and nutritional implications. Journal of Food Research and Nutrition 2020, 4, 45–54. [Google Scholar]

- Raffan, S.; Halford, N.G. Processing of vegetable oils: A review on the impact of refining practices on quality. Food Science and Human Wellness 2019, 8, 218–229. [Google Scholar]

- WHO/FAO. Codex standard for named vegetable oils (Codex Stan 210-1999); World Health Organization/Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 2024; Available online: https://www.fao.org/fao-whocodexalimentarius/.

- Raffan, S.; Halford, N.G. Edible oil processing and nutritional quality: Current challenges and future directions. Frontiers in Plant Science 2019, 10, 1295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adeyeye, S.A.O.; Oyedele, O.A.; Abegunde, T.O. Safety and shelf life evaluation of traditionally and industrially processed vegetable oils in Nigeria. Journal of Food Safety 2020, 40, E12868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurr, M.I.; Harwood, J.L. Lipids: An Outline of Their Chemistry and Biochemistry 5th Edition; Chapman and Hall (CRC) Publishers: UK, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Gunstone, F.D. Structured and Modified Lipids; Marcel Dekker Publishers: New York City, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Chow, C.K. Fatty Acids in Foods and Their Health Implications, 3rd Edition ed; CRC Press: Florida, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahena, F.; Zaidul, I.S.M.; Jinap, S.; Karim, A.A.; Abbas, K.A.; Norulaini, N.A.N.; Omar, A.K.M. Application of supercritical CO2 in lipid extraction–A review. Journal of Food Engineering 2009, 95, 240–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibon, V. Palm Oil and Palm Kernel Oil Refining and Fractionation Technology: Palm Oil; Lai, O.M.; Tan, C.P. and Akoh, C.C. (Editors). AOCS Press: Urbana, Illinois, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gharby, S.; Hajib, A.; Ibourki, M.; Sakar, E.H.; Nounah, I.; Moudden, H.E.; Elibrahimi, M.; Harhar, H. Induced changes in olive oil subjected to various chemical refining steps: a comparative study of quality indices, fatty acids, bioactive minor components, and oxidation stability kinetic parameters. Chemical Data Collections 2021, 22, 100702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reeves, C.J.; Menezes, P.L.; Jen, T.C. Lovell, M.R. The influence of fatty acids on tribological and thermal properties of natural oils as sustainable biolubricants. Tribology International 2015, 90, 123–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syed, A. Oxidative Stability and Shelf Life of Vegetable Oils: Oxidative Stability and Shelf Life of Foods Containing Oils and Fats; Min Hu, Charlotte Jacobsen (Editors). AOCS Press 2016, 187–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheil, D.; Casson, A.; Meijaard, E.; van Noordwijk, M.; Gaskell, J.; Sunderland-Groves, J.; Werts, K.; Kanninen, M. The impact and opportunities of oil palm in Southeast Asia: What do we know and what do we need to know? Paper 51; Center for International Forestry Research (CIFOR) Publications: Bogor, Indonesia, 2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schnieder, S.L. Tropical Oils: Composition, Properties and Uses; Springer Science and Business Media: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Ayu, D.F.; Andarwulan, N.; Hariyadi, P.; Purnomo, E.H. Photo-oxidative changes of red palm oil as affected by light intensity. International Food Research Journal 2017, 24, 1270–1277. [Google Scholar]

- Hui, Y.H. (2005). Bailey’s Industrial Oil and Fat Products: Edible Oil and Fat Products - Processing Technologies, 6th Edition, Volume 5, Wiley-Interscience Publishers, New York City, USA.

- Lamas, D.L.; Constenla, D.T.; Raab, D. Effect of degumming process on physicochemical properties of sunflower oil. Biocatalysis and Agricultural Biotechnology 2016, 6, 138–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evrard, J.; Pages-Xatart-Pares, X.; Argenson, C. and Morin, O. Processes for obtaining and nutritional compositions of sunflower, olive and rapeseed oils. Nutrition and Dietetics Notebooks 2007, 42, 13–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adeyeye, S.A.O.; Adebayo-Oyetoro, A.O.; Ogunbanwo, S.T. Microbiological quality, physicochemical characteristics and sensory evaluation of traditionally processed palm oil. Journal of Food Safety and Hygiene 2020, 6, 107–115. [Google Scholar]

- Nzeka, U.M. Nigeria edible oils sector update. USDA Foreign Agricultural Service, Global Agricultural Information Network (GAIN) Report. Retrieved from https://www.fas.usda.gov/. 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Ajayi, O.B.; Adeleke, R.A.; Ogunniyi, D.S. Hybrid innovations for sustainable oil extraction from underutilized seeds in sub-Saharan Africa. Renewable Agriculture and Food Systems 2023, 38, e14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chew, S.C.; Nyam, K.L. Refining of edible oils: Lipids and Edible Oils; Charis, M. Galanakis (Editor). Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2020; pp. 213–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tasan, M.; Demirci, M. Total and individual tocopherol contents of sunflower oil at different steps of refining. European Food Research and Technology 2005, 220(3-4), 251–254, https://doi. org/10.1007/s00217-004-1045-8, 2-s2.0-17144397594.

- Manjula, S.; Subramanian, R. Membrane technology in degumming, dewaxing, deacidifying, and decolorizing edible oils. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition 2006, 46, 569–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumont, M.J.; Narine, S.S. Soapstock and Deodorizer Distillates from North American Vegetable Oils: review on their Characterization, extraction and utilization. Food Research International 2007, 40, 957–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Giovacchino, L.; Mucciarella, M.R.; Costantini, N.; Ferrante, M.L.; Surricchio, G. Use of nitrogen to improve stability of virgin olive oil during storage. Journal of the American Oil Chemists Society 2002, 79, 339–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.-G.; Wang, Y.-H.; Yang, B.; Mainda, G.; Guol, Y. Degumming of vegetable oil by a new microbial lipase. Food Technology and Biotechnology 2006, 44, 101–104. [Google Scholar]

- Gharby, S.; Harhar, H.; Mamouni, R.; Matthäus, B.; Ait Addi, E.H.; Charrouf, Z. Chemical characterization and kinetic parameter determination under rancimat test conditions of four monovarietal virgin olive oils grown in Morocco. Oilseeds and fats, Crops and Lipids 2016, 23, A401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, S.M.; Sampaio, K.A.; Ceriani, R.; Verhé, R.; Stevens, C.; De Greyt, W. and Meirelles, A.J.A. Effect of type of bleaching earth on the final color of refined palm oil. LWT - Food Science and Technology 2014, 59, 1258–1264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega-García, J.; Gámez-Meza, N.; Noriega-Rodriguez, J.A.; Dennis-Quiñonez, O.; García-Galindo, H.S.; Angulo-Guerrero, J.O.; Medina-Juárez, L.A. Refining of high oleic safflower oil: effect on the sterols and tocopherols content, European Food Research and Technology. 223 2006, 775–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghazani, S.M.; Marangoni, A.G.G. Minor components in canola oil and effects of refining on these constituents: a review. Journal of the American Oil Chemists Society 2013, 90, 923–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van-Nieuwenhuyzen, W.; Tomas, M.C. Update on vegetable lecithin and phospholipid technologies. European Journal of Lipid Science and Technology 2008, 110, 472–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgado, A.; Al-Hamimi, S.; Ramadan, M.F.; De-Wit, M.; Durazzo, A.; Nyam, K.L.; Issaoui, M. Contribution of tocols to food sensorial properties, stability, and overall quality. Journal of Food Quality 2020, 2020, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zufarov, O.; Schmidt, S.; Sekretar, S. Degumming of Rapeseed and sunflower oils. Acta Chimica Slovaca 2008, 1, 321–328. [Google Scholar]

- Dijkstra, A.J. Enzymatic degumming. European Journal of Lipid Science and Technology 2010, 112, 1178–1189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De, B.K.; Patel, J.D. Effect of different degumming processes and some nontraditional neutralizing agent on refining of RBO. Journal of Oleo Science 2010, 59, 121–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Issaoui, M.; Delgado, A.M. Grading, labeling and Standardization of edible oils. In Fruit Oils - Chemistry and Functionality; Ramadan, M.F., Ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Hashim, K.; Tahiruddin, S.; Asis, A.J. Palm and Palm Kernel Oil Production and Processing in Malaysia and Indonesia: Palm Oil; Lai, O.M.; Tan, C.P. and Akoh, C.C. (Editors). AOCS Press, 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dijkstra, A.; Man, Y.B.C. Physicochemical properties and stability of palm kernel oil. Food Chemistry 2008, 123, 659–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wibisono, Y.; Nugroho, W.A.; Chung, T.-W. Dry Degumming of corn-oil for biodiesel using a tubular ceramic membrane. Procedia Chemistry 2014, 9, 210–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clausen, K. Enzymatic oil-degumming by a novel microbial Phospholipase. European Journal of Lipid Science and Technology 2001, 103, 333–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dijkstra, A.J. About water degumming and the hydration of non-hydratable phosphatides. European Journal of Lipid Science and Technology 2017, 119, pp. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gharby, S.; Harhar, H.; Farssi, M.; Taleb, A.A.; Guillaume, D.; Laknifli, A. Influence of roasting olive fruit on the chemical composition and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon content of olive oil. Oilseeds and fats, Crops and Lipids 2018, 25, A303, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Essid, K.; Chtourou, M.; Trabelsi, M.; Frikha, M.H. Influence of the neutralization step on the oxidative and thermal stability of acid olive oil. Journal of Oleo Science 2009, 58, 339–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-M’endez, M.V.; M’arquez-Ruiz, G.; Dobarganes, M.C. Relationships between quality of crude and refined edible oils based on quantitation of minor glyceridic compounds. Food Chemistry 1997, 60, 549–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yahaya, L.E.; Ajao, A.A.; Jayeola, C.O.; Igbinadolor, R.O.; Mokwunye, F.C. Soap Production from Agricultural Residues - a Comparative Study. American Journal of Chemistry 2012, 2, 7–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajongbolo, K. Chemical Properties of Local Black Soap Produced from Cocoa Pod Ash and Palm Oil Waste. International Journal of Trend in Scientific Research and Development 2020, 4, 713–715. [Google Scholar]

- Nafisah, U.; Nugroho, P.S.A.; Setyorini, W. (2024). Liquid Soap Formulation from Cocoa Pod Husk Extract (Theobroma Cacao L.) and Antioxidant Activity. International Journal of Pharmaceutical and.

- Gharby, Y. Palm oil production through sustainable plantations. European Journal of Lipid Science and Technology 2022, 109, 289–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monte, M.L.; Monte, M.L.; Pohndorf, R.S.; Crexi, V.T.; Pinto, L.A.A. Bleaching with blends of bleaching earth and activated carbon reduces color and oxidation products of carp oil. European Journal of Lipid Science and Technology 2015, 117, 829–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zschau, W. Bleaching of edible fats and oils. European Journal of Lipid Science and Technology 2001, 103, 505–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

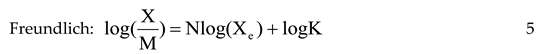

- Liu, Y.; Huang, J.; Wang, X. Adsorption isotherms for bleaching soybean oil with activated attapulgite. Journal of The American Oil Chemists Society 2008, 85, 979–984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amari, A.; Gannouni, H.; Khan, M.I.; Almesfer, M.K.; Elkhaleefa, A.M.; Gannouni, A. Effect of Structure and Chemical Activation on the Adsorption Properties of Green Clay Minerals for the Removal of Cationic Dye. Applied Sciences 2018, 8, 2302–2311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usman, M.A.; Ekwueme, V.I.; Alaje, T.O.; Mohammed, A.O. Characterization, acid activation and bleaching performance of Ibeshe clay, Lagos, Nigeria. ISRN Ceramics 2012, 2012, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gnanaprakasam, A.; Sivakumar, V.M.; Surendhar, A.; Thirumarimurugan, M.; Kannadasan, T. Recent Strategy of Biodiesel Production from Waste Cooking Oil and Process Influencing Parameters: A Review. Journal of Energy 2013, 2013, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musah, M.; Azeh, Y.; Mathew, J.T.; Umar, M.T.; Abdulhamid, Z.; Muhammad, A.I. Adsorption Kinetics and Isotherm Models: A Review. Aliphate Journal of Science and Technology 2022, 1, 20–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omar, S.; Girgis, B.; Taha, F. Carbonaceous materials from seed hulls for bleaching of vegetable oils. Food Research International 2003, 36, 11–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amany, A.M.M.; Arafat, S.A. and Soliman, H.M. Effectiveness of olive-waste ash as an adsorbent material for the regeneration of fried sunflower oil. Current Science International 2014, 3, 311–319. [Google Scholar]

- Ismail, M.I.; Muhammad, H.; Hamidon, M.; Zulhilmie, M.; Sofi, S. Renewable bleaching alternatives (RBA) for palm oil refining from waste materials. Journal of Applied Environmental and Biological Sciences 2016, 6, 52–57. [Google Scholar]

- Salawudeen, T.O.; Alade, A.O.; Arinkoola, A.O.; Jimoh, M.O. Potential application of oyster shell as adsorbent in vegetable oil refining. Advances in Research 2016, 6, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chairgulprasert, V.; Madlah, P. Removal of Free Fatty Acid from Used Palm Oil by Coffee Husk Ash. Science and Technology Asia 2018, 23, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Butt, F.; Syed, M.A.; Shaik, F. Palm Oil Bleaching Using Activated Carbon Prepared from Neem Leaves and Waste Tea. International Journal of Engineering Research and Technology 2020, 13, 620–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, H.; Liu, L.; Li, Y. Advances in deodorization technology in vegetable oil refining. LWT–Food Science and Technology 2021, 136, 110354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, L. A comparative analysis of bleaching and deodorization stages in vegetable oil refining. Food Processing and Preservation 2021, 45, e15120. [Google Scholar]

- Hussain-Sherazi, S.T.; Mahesar, S.A.; Sirajuddin, A. Vegetable Oil Deodorizer Distillate: A Rich Source of the Natural Bioactive Components. Journal of Oleo Science 2016, 65, 957–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siragakis, G.; Antonopoulos, K.; Valet, N.; Spiratos, D. Olive oil and pomace olive oil processing. Grasas y Aceites. 2006, 57, 56–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chew, S.-C.; Tan, C.-P.; Long, K.; Nyam, K.-L. Effect of chemical refining on the quality of kenaf (Hibiscus cannabinus) seed oil. Industrial Crops and Products. 89 2016, 59–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Z.; Liu, G.; Wang, L. Glycidyl fatty acid esters in refined edible oils: a review on formation, occurrence, analysis, and elimination methods. Comprehensive Reviews in Food Science and Food Safety 2017, 16, 263–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chew, S.-C.; Tan, C.-P.; Nyam, K.-L. Application of response surface methodology for optimizing the deodorization parameters in chemical refining of kenaf seed oil, Separation and Purification Technology. 184 2017, 144–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haro, M.A.; Rubio, M.; Pérez-Bibbins, B. Nutritional comparison of traditionally and industrially refined oils. Foods 2020, 9, 134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Oil Type | Properties | Applications in Food System | Observations | Author/ Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Soybean Oil | High in polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs); contains linoleic and linolenic acids; prone to oxidation |

Used in frying, baking, margarine production, and salad dressings | Requires degumming due to high phospholipid content; often hydrogenated to improve stability |

[2,3] |

| Palm Oil | High in saturated and monounsaturated fats; rich in carotenoids and tocotrienols |

Used in frying oils, margarine, shortening, processed snacks |

Needs bleaching and modified deodorization due to carotenoid content and distinctive odor | [10] |

| Groundnut/Peanut Oil | Rich in oleic and linoleic acids; good oxidative stability |

Used in deep frying, cooking oil, confectionery | Popular for flavor and shelf stability; susceptible to aflatoxin contamination if poorly stored | [12] |

| Sunflower Oil | High in linoleic acid (standard type) or oleic acid (high-oleic type); contains vitamin E | Common in salad oil, mayonnaise, frying, and cooking | Refined to remove waxes and stabilize for longer shelf life |

[5] |

| Coconut Oil | High in medium-chain saturated fatty acids (e.g., lauric acid); stable at high temperatures |

Used in baking, confectionery, and traditional cooking | Virgin oil is minimally processed; refined oil is stable with low unsaturation | [14] |

| Rapeseed/ Canola Oil | Low in saturated fat; high in oleic acid and omega3 fatty acids | Used in salad dressings, baking, and cooking | Mild flavor and favorable fatty acid profile; requires mild deodorization | [2] |

| Olive Oil | Rich in monounsaturated oleic acid; contains polyphenols and antioxidants | Used in salads, sautéing, and Mediterranean dishes | Extra virgin oil is cold-pressed and unrefined; flavor and bioactives preserved | [9] |

| Rice Bran Oil | Contains γoryzanol, phytosterols, and tocopherols; moderate PUFA and MUFA composition |

Used in frying, salad oils, and health-focused products | Good oxidative stability; requires dewaxing and high-temp deodorization |

[6] |

| Avocado Oil | High in oleic acid and vitamin E; low in saturated fats | Used in cooking, salad dressing, and cosmetics | Increasing interest as a premium oil; cold-pressed varieties retain nutrients and flavor | [16] |

| Mango Kernel Oil | Moderate in saturated and unsaturated fats; potential in nonconventional oil sources | Used experimentally in margarine, soap, and biodiesel production | Underutilized by-product with economic potential; refining techniques under development | [17] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).