Submitted:

31 July 2025

Posted:

06 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Related Works

3. Methodology

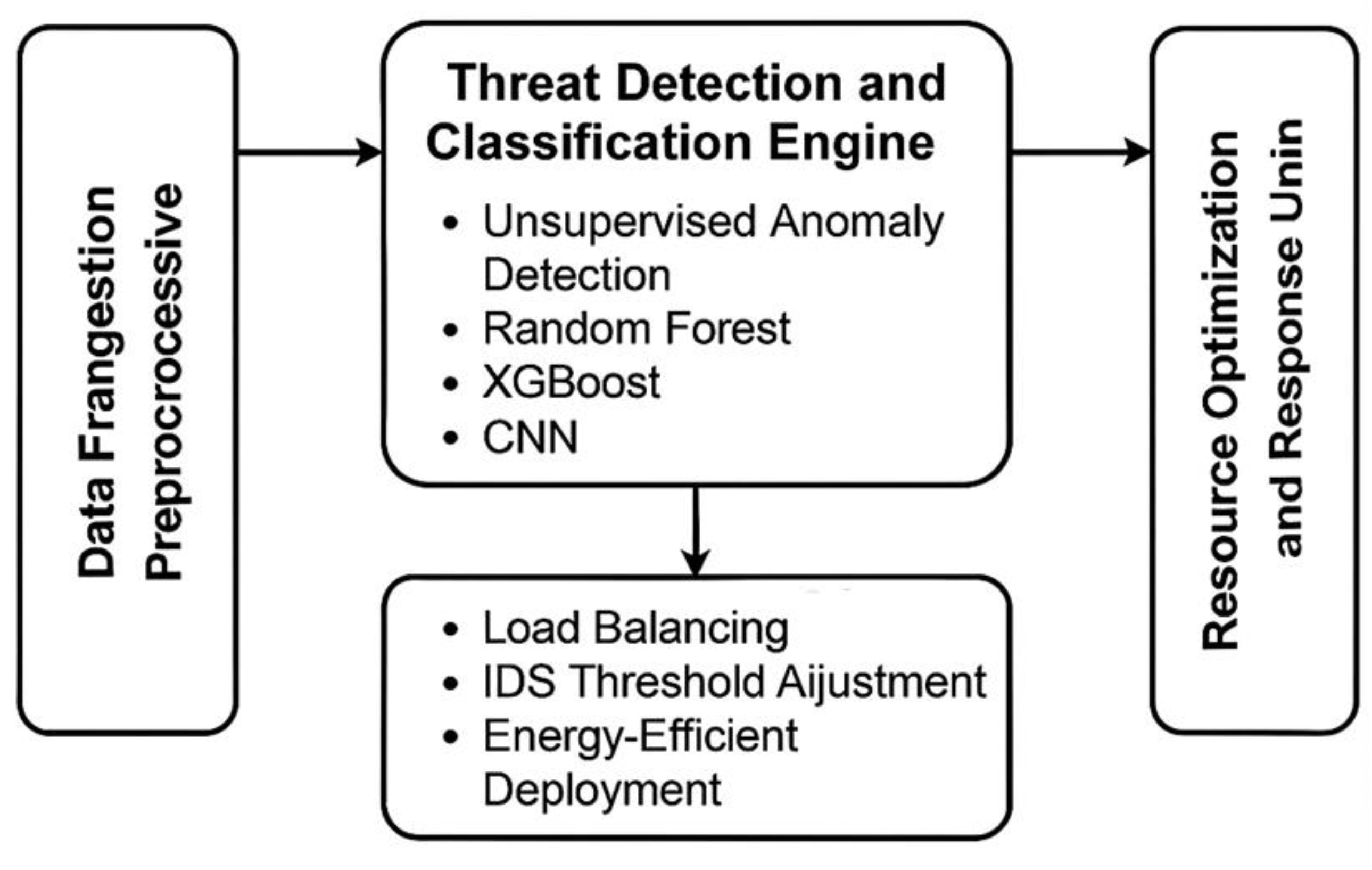

3.1. Framework Overview

3.2. Data Preprocessing

3.3. Threat Detection Module

3.4. Optimization Engine

4. Experimental Setup

4.1. Dataset Details

4.2. Training Environment

5. Results and Discussion

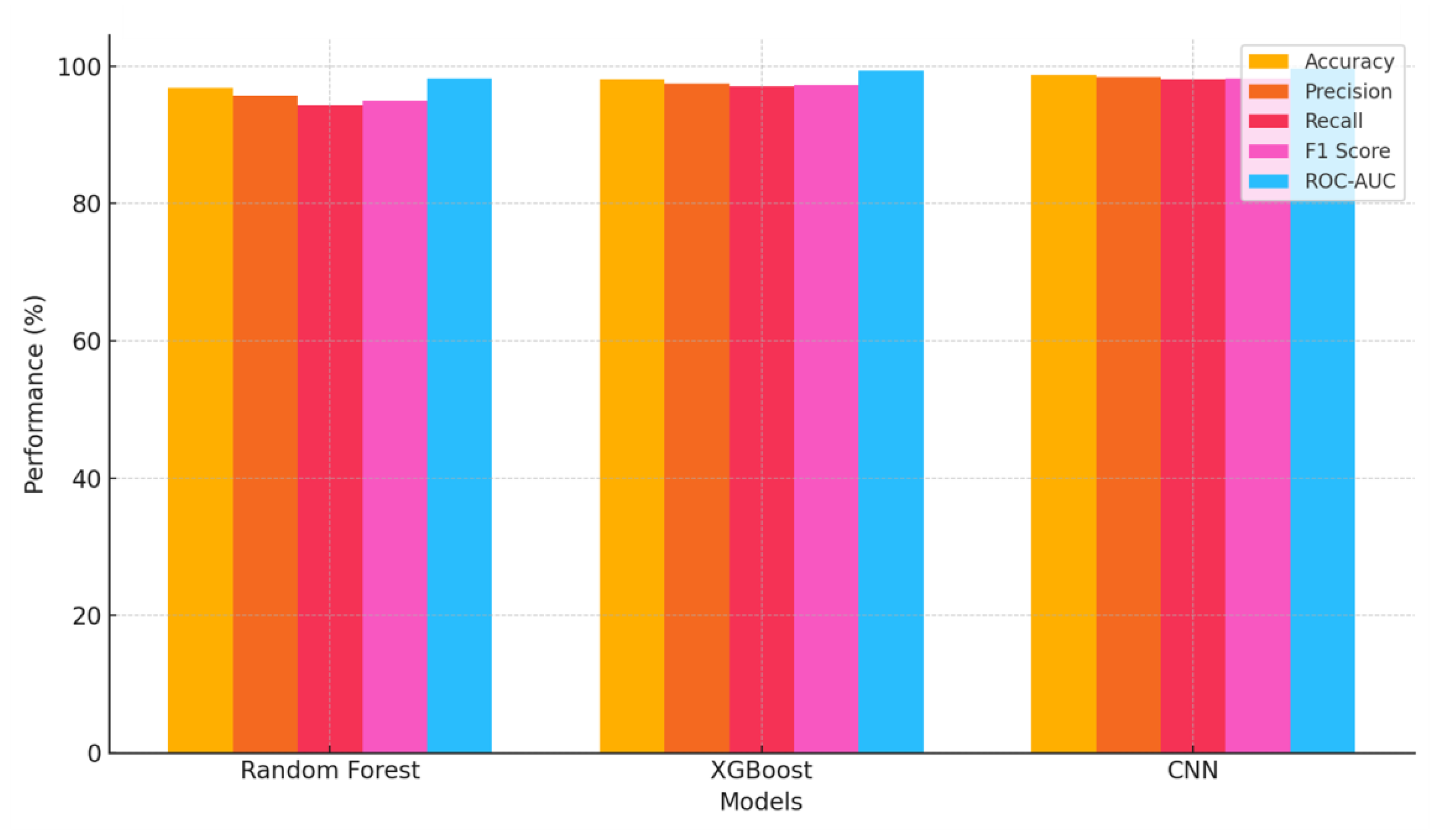

5.1. Detection Performance

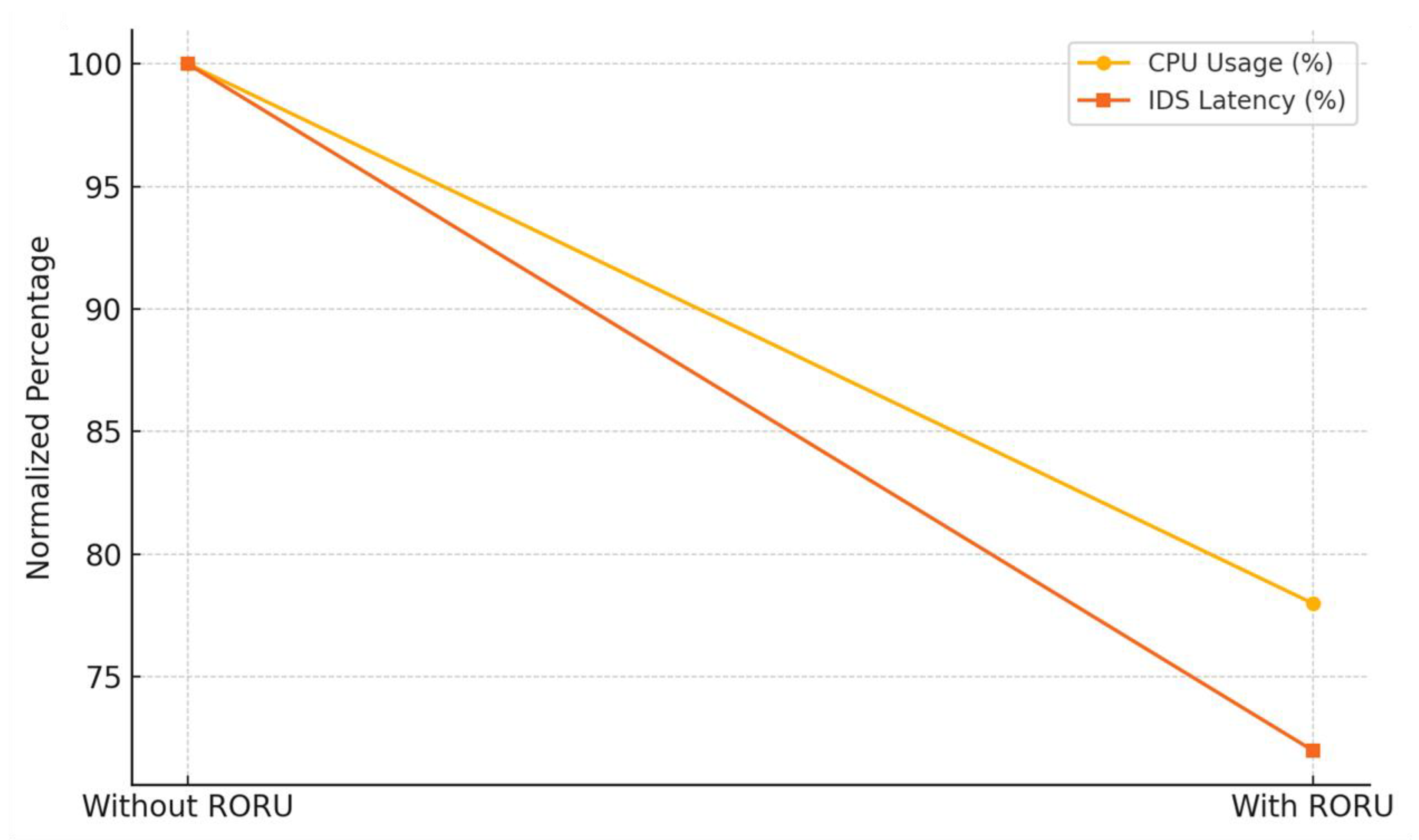

5.2. Optimization Performance

| Metric | Baseline (No RORU) | With RORU | Improvement |

| Average CPU Usage | 68% | 53% | 22%↓ |

| IDS Response Latency (ms) | 210 | 151 | 28%↓ |

| Energy Usage in Edge (kWh/day) | 4.2 | 3.49 | 17%↓ |

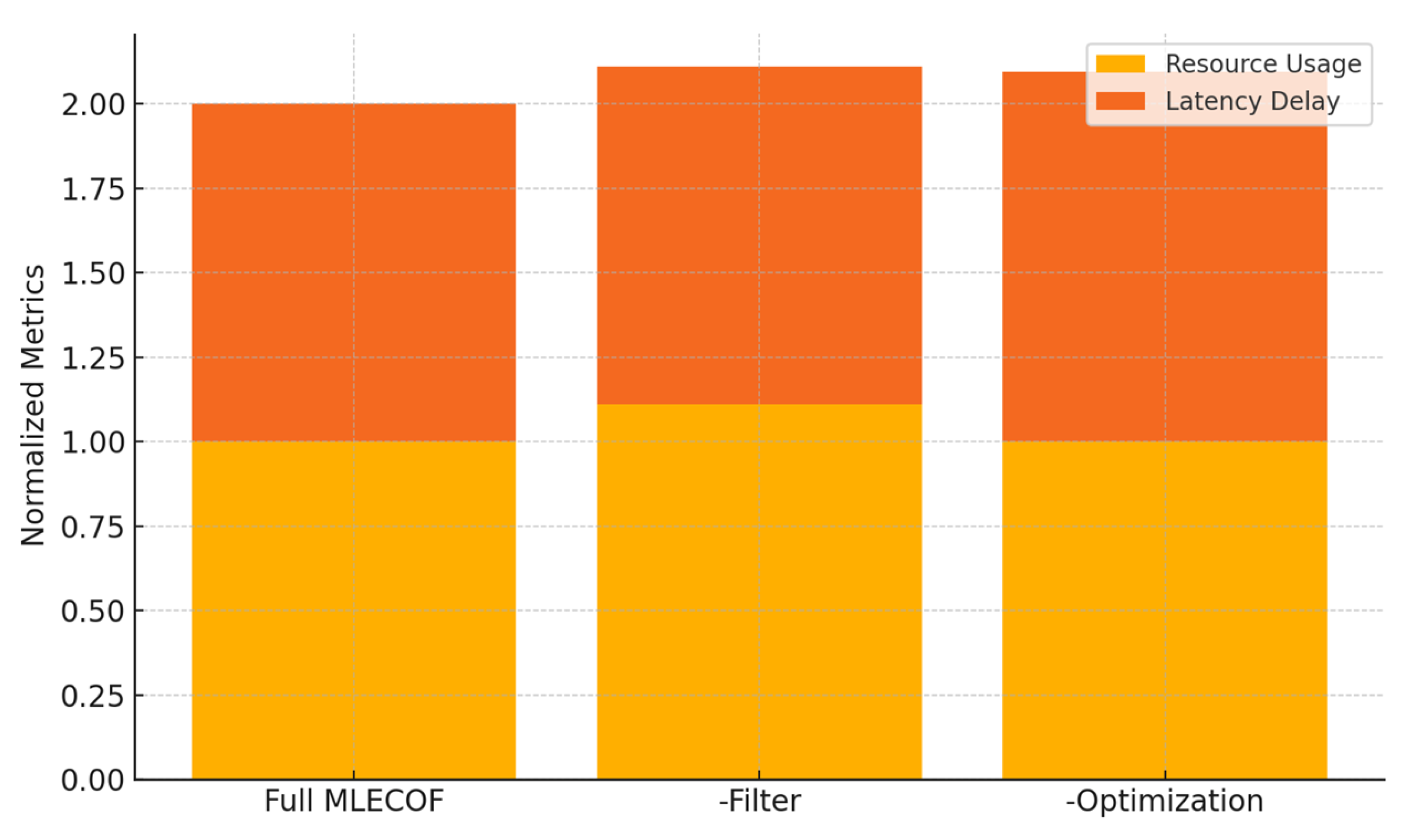

5.3. Ablation Study

6. Conclusions

References

- Singh, B. (2025). Oracle Database Vault: Advanced Features for Regulatory Compliance and Control. Available at SSRN 5267938.

- Dalal, A. (2025). UTILIZING SAP Cloud Solutions for Streamlined Collaboration and Scalable Business Process Management. Available at SSRN 5268108.

- Arora, A. (2025). Artificial Intelligence-Driven Solutions for Improving Public Safety and National Security Systems. Available at SSRN 5268151.

- Singh, H. (2025). Enhancing Cloud Security Posture with AI-Driven Threat Detection and Response Mechanisms. Available at SSRN 5267878.

- Kumar, T. V. (2019). Cloud-Based Core Banking Systems Using Microservices Architecture.

- Sidharth, S. (2020). The Growing Threat of Deepfakes: Implications for Security and Privacy.

- Dalal, A. (2025). Driving Business Transformation Through Scalable and Secure Cloud Computing Infrastructure Solutions. Available at SSRN 5268120.

- Singh, B. (2025). Integrating Threat Modeling in DevSecOps for Enhanced Application Security. Available at SSRN 5267976.

- Arora, A. (2025). Transforming Cybersecurity Threat Detection and Prevention Systems Using Artificial Intelligence. Available at SSRN 5268166.

- Sidharth, S. (2019). Quantum-Enhanced Encryption Techniques for Cloud Data Protection.

- Singh, H. (2025). Cybersecurity for Smart Cities: Protecting Infrastructure in the Era of Digitalization. Available at SSRN 5267856.

- Kumar, T. V. (2020). Generative AI Applications in Customizing User Experiences in Banking Apps.

- Dalal, A., et al. (2025, February). Developing a Blockchain-Based AI-IoT Platform for Industrial Automation and Control Systems. In IEEE CE2CT (pp. 744–749). [CrossRef]

- Shuriya, B., & Rajendran, A. (2019). A Fuzzy Responsibility-Based Access Organizer for Leukemia Record Protection using KWatts Algorithm. Appl. Math, 13(6), 1047-1052. [CrossRef]

- Singh, B. (2025). DevSecOps: A Comprehensive Framework for Securing Cloud-Native Applications. Available at SSRN 5267982.

- Sidharth, S. (2021). Multi-Cloud Environments: Reducing Security Risks in Distributed Architectures.

- Arora, A. (2025). Securing Multi-Cloud Architectures Using Advanced Cloud Security Management Tools. Available at SSRN 5268184.

- Shuriya, B., & Rajendran, A. (2017). Tranquilize Role Mining using HR (Heuristic Random) Approach. Asian Journal of Research in Social Sciences and Humanities, 7(1), 744-753. [CrossRef]

- Dalal, A. (2025). Revolutionizing Enterprise Data Management Using SAP HANA for Improved Performance and Scalability. Presented May 2025.

- Singh, B. (2025). Building Secure Software Faster with DevSecOps Principles, Practices, and Implementation Strategies. (May 23, 2025).

- Kumar, T. V. (2017). Cross-Platform Mobile Application Architecture for Financial Services.

- Sidharth, S. (2022). The Role of Zero Trust Architecture in Modern Cybersecurity Frameworks.

- Mouna, P. S., Sivaprakash, P., Kumar, K. A., Samuel, P., Shuriya, B., & Sharma, V. (2024). Data Modeling and Analysis for the Internet of Medical Things. In Wireless Communication Technologies (pp. 197-223). CRC Press.

- Singh, H. (2025). The Role of Multi-Factor Authentication and Encryption in Securing Data Access of Cloud Resources in a Multitenant Environment. Available at SSRN 5267886.

- Arora, A. (2025). Improving Public Sector Cybersecurity Through AI-Augmented Monitoring Platforms. Available at SSRN 5268174.

- Dalal, A. (2025). Leveraging Blockchain to Strengthen AI Model Integrity and Data Provenance in Federated Learning. Available at SSRN 5268136.

- Singh, B. (2025). From CI/CD to CI/CT: Integrating Threat Intelligence into Continuous Development Pipelines. Available at SSRN 5268001.

- Sidharth, S. (2024). Enhancing Smart Grid Resilience Against Cyberattacks Using Machine Learning.

- Kumar, T. V. (2021). Securing Fintech APIs Using Lightweight Cryptography.

- Singh, H. (2025). Policy-Driven AI Governance in Cloud-Native Enterprises. Available at SSRN 5267899.

- Arora, A. (2025). Architecting AI Workloads for High-Security Cloud Environments. Available at SSRN 5268193.

- Dalal, A. (2025). Real-Time Risk Assessment in Cloud Platforms Using Adaptive Machine Learning Algorithms. Available at SSRN 5268141.

- Singh, B. (2025). Continuous Compliance in DevSecOps Pipelines Through Automated Policy Validation. Available at SSRN 5268012.

- Sidharth, S. (2020). Ethical Hacking in Critical Infrastructure: A Framework for Evaluation.

- Kumar, T. V. (2018). Data Migration Challenges in Hybrid Cloud Environments.

- Singh, H. (2025). Federated Threat Intelligence Sharing for Inter-Cloud Cyber Defense. Available at SSRN 5267905.

- Arora, A. (2025). Synthetic Data in Cybersecurity: Balancing Privacy and Accuracy. Available at SSRN 5268201.

- Dalal, A. (2025). Interoperable Cloud Security Tools: A Vendor-Neutral Approach for SMEs. Available at SSRN 5268149.

- Singh, B. (2025). Threat-Informed Defense for AI-Powered SaaS Platforms. Available at SSRN 5268025.

- Umamaheswari, S., Jagannath, V., & Shuriya, B. (2025, April). Integrated Wearable System for Enhanced Soldier Health Monitoring and Battlefield Awareness. In 2025 3rd International Conference on Advancements in Electrical, Electronics, Communication, Computing and Automation (ICAECA) (pp. 1-6). IEEE. [CrossRef]

- Sidharth, S. (2023). Adaptive Honeypot Deployment for IIoT Security Enhancement.

- Kumar, T. V. (2017). Enabling Blockchain-Based Identity in Banking Applications.

- Singh, H. (2025). Data-Centric Security in the Cloud: From Classification to Policy Enforcement. Available at SSRN 5267914.

- Umamaheswari, S., Lingeswaran, G., & Shuriya, B. (2025, April). Integrated Real-Time Monitoring for Soldier Health and Operational Efficiency: A Multi-Metric Approach. In 2025 3rd International Conference on Advancements in Electrical, Electronics, Communication, Computing and Automation (ICAECA) (pp. 1-6). IEEE. [CrossRef]

- Arora, A. (2025). Container Security Solutions: Evaluating Threat Models in Kubernetes Clusters. Available at SSRN 5268212.

- Dalal, A. (2025). Enabling Smart Manufacturing Using AI-Integrated Edge Security Protocols. Available at SSRN 5268160.

- Singh, B. (2025). Improving Supply Chain Security with Cloud-Enabled Predictive Analytics. Available at SSRN 5268036.

- Sidharth, S. (2022). AI-Based Surveillance Systems and the Privacy Conundrum.

- Kumar, T. V. (2020). Intelligent Load Balancing in Multi-Tenant Cloud Infrastructures.

- Umamaheswari, S., Lingeswaran, G., & Shuriya, B. (2025, April). Integrated Real-Time Monitoring for Soldier Health and Operational Efficiency: A Multi-Metric Approach. In 2025 3rd International Conference on Advancements in Electrical, Electronics, Communication, Computing and Automation (ICAECA) (pp. 1-6). IEEE. [CrossRef]

- Singh, H. (2025). Vulnerability Prioritization in Cloud Workloads Using Reinforcement Learning. Available at SSRN 5267922.

- Arora, A. (2025). Attack Graph Analysis for Proactive Cybersecurity in Cloud-First Organizations. Available at SSRN 5268225.

- Dalal, A. (2025). Industrial Edge Cloud Security with Lightweight AI Agents. Available at SSRN 5268171.

- Singh, B. (2025). Intelligent Automation for Red Team Operations in DevSecOps Pipelines. Available at SSRN 5268047.

- Sidharth, S. (2023). IoT and SCADA System Security in Water Treatment Facilities.

- Kumar, T. V. (2016). Platform-Independent Secure Banking Portals Using WebAssembly.

- Singh, H. (2025). Anomaly Detection in Encrypted Traffic Using Self-Supervised Models. Available at SSRN 5267932.

- Arora, A. (2025). Zero-Day Attack Detection in Multi-Cloud Systems Using Hybrid AI Models. Available at SSRN 5268233.

- Dalal, A. (2025). Framework for AI-Powered Adaptive Defense in Multi-Vendor Cloud Environments. Available at SSRN 5268181.

- Singh, B. (2025). Continuous Monitoring of Security Controls in Cloud DevSecOps Pipelines. Available at SSRN 5268058.

- Sidharth, S. (2020). AI-Augmented Behavioral Biometrics for Secure Access in Cloud Environments.

- Kumar, T. V. (2019). Secure Onboarding of Mobile Devices in Enterprise Wi-Fi Networks.

- Singh, H. (2025). Multi-Cloud Compliance Automation Using Policy-as-Code. Available at SSRN 5267940.

- Arora, A. (2025). Hybrid Cloud Migration Security: AI-Based Assessment of Risk Postures. Available at SSRN 5268240.

- Dalal, A. (2025). Reinforcement Learning Approaches for Dynamic Security Group Management in IaaS Platforms. Available at SSRN 5268195.

- Singh, B. (2025). Securing Kubernetes with AI-Based Pod Anomaly Detection. Available at SSRN 5268069.

- Sidharth, S. (2022). Blockchain in Cyber Forensics: A Review and Implementation.

- Kumar, T. V. (2018). Deploying AI Assistants in Secured Financial Service Environments.

- Singh, H. (2025). Explainable AI for Security Event Correlation in Cloud SIEMs. Available at SSRN 5267952.

- Shuriya, B., Kumar, S. V., & Bagyalakshmi, K. (2024). Noise-Resilient Homomorphic Encryption: A Framework for Secure Data Processing in Health care Domain. arXiv preprint arXiv:2412.11474. [CrossRef]

- Arora, A. (2025). Reducing Insider Threats Through AI-Based Behavioral Analysis. Available at SSRN 5268256.

- Dalal, A. (2025). Smart Contract Verification Framework for Secure IoT-Cloud Integration. Available at SSRN 5268208.

- Shuriya, B., & Thenmozhi, S. (2015). RBAM with Constraint Satisfaction Problem in Role Mining. International Journal of Innovative Research and Development, 4(2).

- Singh, B. (2025). Auto-Remediation of Cloud Misconfigurations Using Predictive Analytics. Available at SSRN 5268081.

- Sidharth, S. (2021). Intrusion Detection in SCADA Systems Using Deep Learning Models.

- Kumar, T. V. (2019). Adaptive Security Frameworks for Mobile Financial Applications.

- Singh, H. (2025). Cyber Risk Quantification Using Bayesian AI Models. Available at SSRN 5267965.

- Shuriya, B., Prakash, P., & Kiruthikka, D. C. (2022, March). Qos Based Aes Cryptography Network Model. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Innovative Computing & Communication (ICICC).

- Arora, A. (2025). Scalable Threat Modeling for Distributed Cloud-Native Applications. Available at SSRN 5268265.

- Dalal, A. (2025). Integrating OT and IT Security With Edge AI in Industrial Systems. Available at SSRN 5268217.

- Singh, B. (2025). Proactive Cloud Security Posture Management Using AI-Based Attack Simulations. Available at SSRN 5268092.

- Sidharth, S. (2023). Use of Digital Twins in Cyber-Physical System Security.

- Kumar, T. V. (2020). A Framework for AI-Based Compliance in Fintech Startups.

- Singh, H. (2025). Threat Hunting in Cloud Using AI-Enhanced SIEM. Available at SSRN 5267971.

| Model | Accuracy | Precision | Recall | F1-score | ROC-AUC |

| Random Forest | 96.8% | 95.7% | 94.3% | 95.0% | 0.982 |

| XGBoost | 98.1% | 97.5% | 97.0% | 97.2% | 0.993 |

| CNN | 98.7% | 98.4% | 98.1% | 98.2% | 0.996 |

| Configuration | Resource Usage Increase | Response Latency Increase |

| Without Anomaly Detection Filter | +11.0% | — |

| Without Optimization Engine | — | +9.5% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).