1. Introduction

Currently, more than 55% of the world’s population lives in urban areas—a figure projected to rise to nearly 70% by 2050—placing unprecedented strain on transport networks and exacerbating traffic congestion, longer travel times, elevated fuel consumption, and higher greenhouse-gas emissions (Sayed, Abdel-Hamid, & Hefny, 2023). Beyond environmental harms, congestion inflicts heavy economic losses: in many megacities, urban delays translate into billions of dollars in wasted productivity annually (Sayed et al., 2023). In response, researchers have turned to dynamic traffic-flow forecasting as a key enabler for smarter, energy-efficient routing.

A wealth of forecasting techniques has emerged in recent years. Classical statistical models (e.g., ARIMA, Kalman filtering) have gradually given way to machine-learning methods—Random Forests, XGBoost and their variants—that capture nonlinear traffic patterns more effectively (Sayed et al., 2023). Deep-learning approaches have further advanced accuracy: Afandizadeh, Abdolahi, and Mirzahossein (2024) demonstrate that LSTM and graph neural network architectures consistently outperform classical baselines on large urban datasets. Mystakidis, Koukaras, and Tjortjis (2025) survey emerging hybrid and attention-based models, highlighting their capacity to fuse spatio-temporal features for improved short-term prediction. Most recently, Wu et al. (2025) introduced a multi-information fusion framework that integrates weather, event, and sensor data, achieving state-of-the-art performance in metropolitan traffic forecasting.

Concurrently, eco-routing algorithms aim to minimize energy consumption—particularly for electric vehicles—by dynamically selecting paths that balance distance, expected speed profiles, road grade, and real-time traffic conditions. Sebai et al. (2022) review optimal EV route-planning methods that incorporate live incident data, showing up to 20% theoretical energy savings over static routing. However, existing surveys tend to treat traffic forecasting and eco-routing in isolation. While comprehensive reviews exist for AI-based traffic prediction (Sayed et al., 2023) and for EV-specific routing strategies (Sebai et al., 2022), there remains no unified treatment of how dynamic flow forecasts can be systematically integrated within global, energy-aware route-planning frameworks.

To address this gap, this paper presents A Review of Dynamic Traffic Flow Prediction Methods for Global Energy-Efficient Route Planning. Our contributions are threefold:

Taxonomy of Forecasting Methods: We classify dynamic traffic-flow prediction techniques—statistical, machine-learning, deep-learning, and hybrid—published between 2020 and 2025, and propose a unified evaluation framework (e.g., RMSE, MAPE, computational latency).

Integration Framework: We develop a theoretical architecture for coupling real-time flow forecasts with multi-objective cost functions (distance, time, energy) in classical path-search algorithms (A*, Dijkstra, genetic algorithms).

Research Gaps and Future Directions: We identify open challenges in data quality, real-time scalability in IoT/5G environments, and extensions to multi-modal, personalized routing, and we outline promising avenues for future work.

The remainder of this review is structured as follows.

Section 2 traces the evolution of dynamic traffic-flow prediction and eco-routing concepts.

Section 3 surveys and categorizes forecasting methods according to their underlying paradigms.

Section 4 develops the theoretical integration framework and compares coupling schemes reported in the literature.

Section 5 discusses current challenges, emerging opportunities—such as connected automated vehicles and digital-twin integration—and concludes with recommendations for future research.

2. Research Background and Development Trajectory

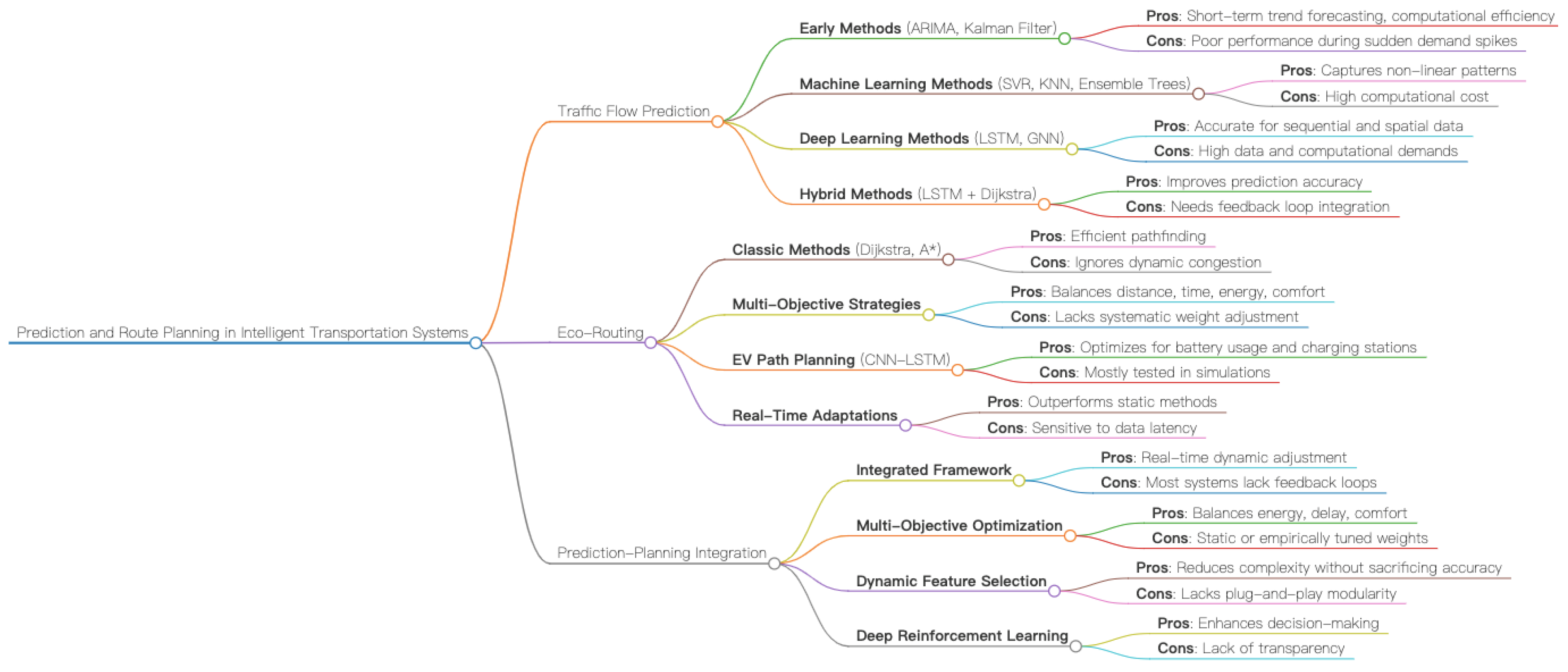

Urbanization has driven the expansion of transportation networks, but it has also intensified energy consumption and carbon emissions. Traditional approaches that rely on single-point technologies are no longer sufficient. In response, the academic community has increasingly treated literature reviews as tools of “knowledge production,” employing critical dialogue to map the consensus, controversies, and gaps across the research landscape—thereby laying the foundation for an integrated and dynamic "prediction–planning" coupled system.To provide a bird’s-eye view of this evolving landscape,

Figure 1 visualizes the three research pillars—Traffic Flow Prediction, Eco-Routing, and Prediction–Planning Integration—along with their key methods and challenges.

This mind map takes Traffic Flow Prediction, Eco-Routing, and Prediction-Planning Integration as the first-level branches, sorting out the various method categories and their main advantages and disadvantages, providing an overview framework for the detailed discussions in Sections 2.1 to 2.3.

2.1. Traffic Flow Prediction

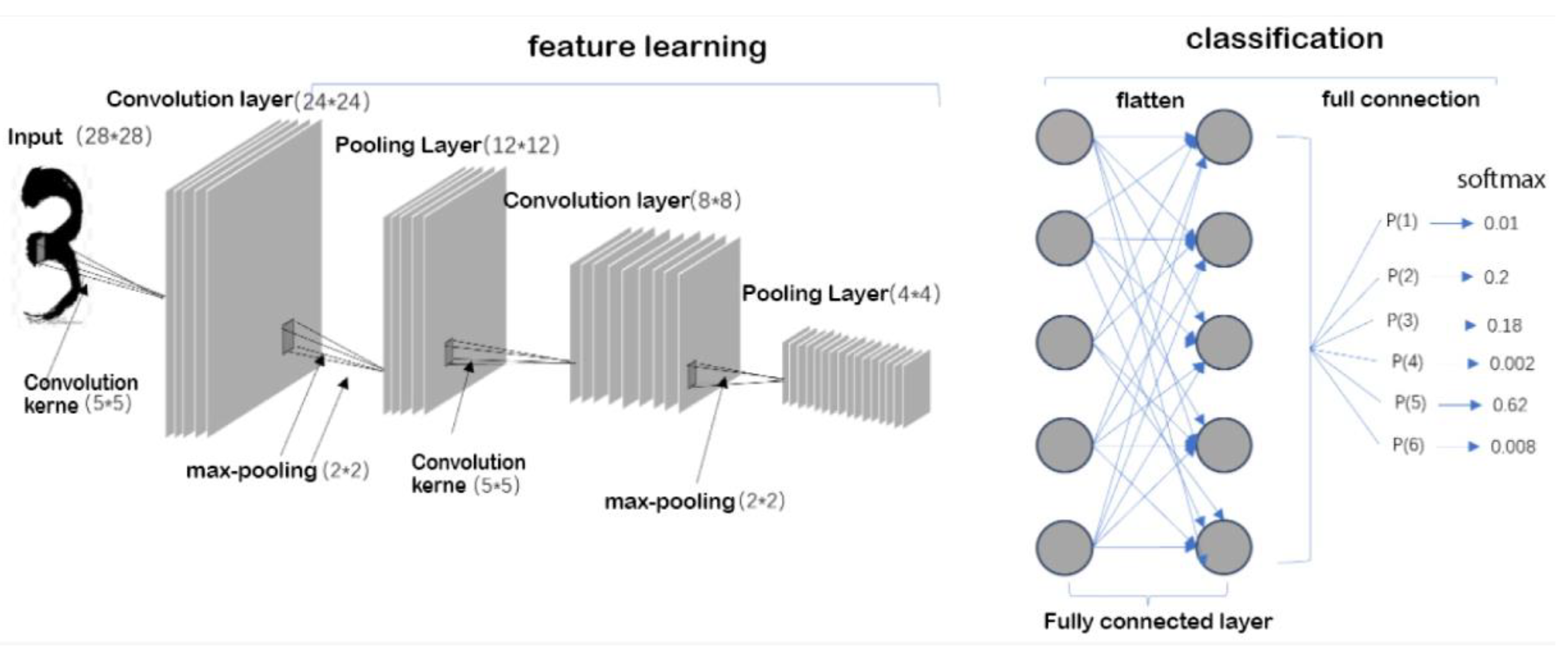

In recent years, traffic flow prediction has progressed from linear, statistics-based methods toward complex, data-driven frameworks, yet the field continues to grapple with a fundamental trade-off between model sophistication and real-world applicability. Early time-series approaches such as ARIMA and Kalman filtering laid the groundwork by effectively modeling short-term linear trends but repeatedly fell short when confronted with sudden demand spikes or nonlinear interactions (Shunping et al., 2009). The machine learning wave that followed—most notably support vector regression (SVR), k-nearest neighbors (KNN) and ensemble tree algorithms—leveraged richer datasets to capture nonlinearity: for instance, Chen et al. (2022) demonstrated how IoT sensor feeds could empower SVR to outperform classical baselines in short-term forecasts, and Lin, Lin, and Gu (2022) achieved notable gains by integrating maximum information coefficient (MIC) feature selection with SVR–KNN ensembles. Concurrently, evolutionary optimizers such as fruit fly and particle swarm algorithms were embedded to fine-tune model parameters (Yan et al., 2021), and Srivastava, Singh, and Nandi (2024) reinforced SVR’s robustness within sustainable mobility contexts.Before delving into temporal models such as LSTM, Figure 3 sketches a typical Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) pipeline, illustrating how stacked convolutions and pooling layers extract spatial features that later feed a fully–connected predictor—an architecture now frequently repurposed for road-segment speed maps and camera-based traffic sensing.

The advent of deep learning—LSTM networks for temporal patterns (Abduljabbar et al., 2021) and graph neural networks (GNNs) with attention for spatial–temporal congestion mapping (Mystakidis et al., 2025)—has further improved accuracy but at a high computational and data-intensity cost. Efforts to reconcile precision with speed have spawned hybrid architectures: Alsolami, Mehmood, and Albeshri (2020) formalized a statistical–machine-learning fusion that preserves lightweight deployment, while MSK (2023) innovatively channeled LSTM outputs into Dijkstra’s algorithm to inform eco-routing decisions. Yet these advances remain largely validated in isolated testbeds rather than in cross-city scenarios, and the crucial link between prediction modules and downstream control systems still lacks the iterative feedback loops necessary for a truly closed-loop solution.

Figure 2.

Convolutional Neural Network pipeline for traffic-related feature extraction.

Figure 2.

Convolutional Neural Network pipeline for traffic-related feature extraction.

Typical CNN workflow for traffic data. The left branch shows stacked convolution (5 × 5) and max-pooling (2 × 2) layers that reduce an input matrix (e.g., image-like speed map) from 28 × 28 to 4 × 4 while preserving salient spatial patterns. The flattened feature vector is then passed through fully-connected layers and a soft-max classifier to estimate class probabilities or continuous traffic metrics.

2.2. Eco-Routing

Eco-routing research has similarly evolved from static energy-weighted shortest-path computation toward dynamic, multi-objective strategies tailored to real-time conditions and electric-vehicle (EV) constraints, but significant challenges remain. Foundational work by Yi and Bauer (2018) applied classic Dijkstra/A* algorithms to minimize energy consumption on fixed networks; however, this approach failed to account for congestion variability, resulting in suboptimal emission reductions under fluctuating traffic. To address this, Alfaseeh and Farooq (2020) proposed a multifactor taxonomy balancing distance, travel time, emissions and comfort, yet their heuristic weightings often lacked systematic justification. Real-time adaptations, such as those by Sebai et al. (2022), have shown that incident-driven rerouting can outperform static baselines, but only when data latency and sensor accuracy are tightly controlled. With the rise of EVs, Zhang et al. (2024) developed a CNN–LSTM hybrid to predict segment-level energy use, thereby guiding route planning specific to battery depletion and charging station availability, while Khatua et al. (2024) implemented federated genetic algorithms to optimize routing under privacy constraints using vehicle-to-infrastructure (V2X) data. Liu et al. (2023) further demonstrated that software-defined networking (SDN) and edge-cloud integration can preallocate computational resources for multimodal eco-routing, highlighting the promise of distributed architectures. Despite these breakthroughs, most eco-routing proposals have been tested predominantly in simulated environments; empirical assessments of real-world energy savings and emission metrics remain scarce, and the influence of driver preferences and compliance behaviors has yet to be systematically incorporated into algorithmic frameworks.

2.3. Prediction–Planning Integration

The integration of traffic prediction with eco-routing planning promises a self-optimizing framework in which forecasts dynamically inform routing decisions and, reciprocally, feedback from routing outcomes refines predictive models, yet the field has only just scratched the surface of this “prediction–planning” paradigm. Sheng, He, and Guo (2017) first articulated how dynamic urbanization trends could adjust routing cost functions in real time, and Chandra (2025) advanced this vision by conceptualizing dual “data-driven” and “value-driven” control loops for sustainable traffic management. Nevertheless, most existing systems implement a unidirectional pipeline—predictions feed into routing—without closing the loop through iterative model updates. Moreover, multi-objective optimizations typically rely on static or empirically tuned weight vectors that lack rigorous theoretical underpinning, undermining their adaptability when balancing energy, delay, and user comfort. Encouragingly, Madupuri et al. (2023) applied swarm intelligence techniques to dynamically calibrate both forecasting and routing modules online, and Lin et al. (2022) demonstrated that adaptive feature selection can dramatically reduce system complexity without sacrificing accuracy. Yet an overarching, modular architecture—one that supports plug-and-play integration across heterogeneous urban platforms—is still absent. Deep and reinforcement learning techniques offer powerful decision-making capabilities but suffer from “black-box” opacity, limiting stakeholder trust and practical adoption. Lastly, the resilience of integrated systems under “long-tail” scenarios—such as major accidents, extreme weather, or sudden demand surges—has yet to undergo rigorous stress testing. Addressing these gaps through a unified, interpretable, and empirically validated framework will be essential to transform the literature’s cumulative insights into operational, future-proof mobility solutions.

3. Review of Dynamic Traffic Flow Prediction Methods

3.1. Statistical Models

3.1.1. ARIMA and SARIMA

The Autoregressive Integrated Moving Average (ARIMA) model and its seasonal extension, SARIMA, have long been key tools in the field of traffic flow prediction, particularly when dealing with stationary time series data. ARIMA constructs models by combining Autoregressive (AR), Integration (I), and Moving Average (MA) components to capture trends and periodic variations in the data. Similarly, SARIMA enhances this model by incorporating seasonal components, improving the fitting capability for data exhibiting seasonal fluctuations (Dubey et al., 2021). Both ARIMA and SARIMA have held significant positions in early traffic flow prediction research due to their simple structure, computational efficiency, and applicability for forecasting stable data.

However, a major limitation of ARIMA and SARIMA lies in their high requirements for data stationarity, which makes them less effective when facing sudden events or short-term fluctuations. For instance, when dealing with non-linear events such as sudden traffic congestion or accidents, ARIMA and SARIMA models tend to exhibit delayed responses (Sirisha et al., 2022). In the application of energy-efficient route planning, although ARIMA and SARIMA can provide baseline predictions for long-term stable road segments, they show considerable limitations in predicting dynamic and non-stationary traffic flows. Therefore, while these methods still hold value in certain contexts, they fall short in supporting real-time traffic management and energy optimization decision-making.

3.1.2. Kalman Filter

The Kalman Filter is a state estimation technique based on recursive Bayesian estimation, enabling dynamic updates even in the presence of incomplete data and substantial system noise (Chen & Chen, 2024). It combines the system's state-space model with observation data to perform real-time traffic flow prediction updates. Compared to ARIMA and SARIMA, the Kalman Filter's advantages lie in its low latency and online update capabilities, making it particularly suitable for handling noisy and uncertain traffic data (Yi & Bauer, 2018). Additionally, by using recursive calculations, it reduces storage requirements and improves computational efficiency.

Nonetheless, the Kalman Filter has limitations in that it assumes noise follows a Gaussian distribution, which may hinder its performance when dealing with complex, non-Gaussian traffic flow characteristics. For non-linear dynamics in traffic flows, the Kalman Filter’s prediction accuracy may be compromised. In the context of energy-efficient route planning, the Kalman Filter is suitable for real-time traffic monitoring at intersection levels and micro-level dynamic adjustments. However, its performance is often less effective than machine learning or deep learning models when applied to large-scale, long-term forecasts. Thus, the Kalman Filter is better suited for small-scale, high-real-time-demand scenarios rather than global energy-efficient route optimization that requires more complex models.

3.1.3. Fourier Series and Other Methods

Fourier series and other frequency-domain methods can effectively decompose traffic flow data into periodic components, which is particularly useful for scenarios where traffic flow follows strong cyclic patterns (Mystakidis et al., 2025). Fourier transform has an advantage in extracting frequency components from data, helping to identify patterns during peak traffic periods and providing valuable insights for energy-efficient route planning. However, the main issue with frequency-domain methods is their limited ability to respond to sudden traffic events, as they focus on periodic patterns and are often ineffective in predicting non-periodic traffic events.

Wavelet transform methods, which possess strong localization properties, can handle non-stationary data and have shown promising results in some dynamic traffic flow forecasting tasks. However, the preprocessing steps involved in frequency-domain analysis or wavelet transform typically introduce additional latency, which can be detrimental for real-time traffic management. Overall, while these methods provide certain advantages in forecasting periodic traffic flow, they often need to be combined with other techniques to yield more accurate predictions in the face of complex, non-periodic, or sudden traffic events.

3.2. Machine Learning Models

3.2.1. Linear Regression and Support Vector Regression (SVR)

Linear regression and Support Vector Regression (SVR) are classical machine learning methods frequently used in traffic flow prediction. Linear regression builds a linear relationship between features and target variables, making it easy to understand and implement, suitable for situations where the relationship between features and target is relatively linear. However, linear regression struggles to handle non-linear relationships, and as the complexity of the data increases, its prediction accuracy tends to drop significantly (Chen et al., 2022). SVR, by introducing kernel functions, can effectively address complex non-linear issues, performing well especially on medium-sized datasets, and exhibiting strong generalization ability and robustness.

Despite the advantages, SVR’s main drawback lies in its high sensitivity to the selection of hyperparameters and its substantial computational cost, particularly when working with large datasets and high-frequency updates. In energy-efficient route planning applications, SVR can perform well in medium-term predictions, but it faces significant challenges when handling large-scale, real-time updating traffic flows.

3.2.2. Random Forest (RF)

Random Forest (RF) is an ensemble learning method that aggregates predictions from multiple decision trees, offering strong non-linear modeling capabilities and good overfitting resistance (Alfaseeh & Farooq, 2020). RF automatically selects features and evaluates feature importance when dealing with high-dimensional, complex data. However, RF incurs a significant computational cost, especially when dealing with large datasets, as the choice of tree depth and number directly impacts the model's response speed. In real-time traffic flow prediction, RF may face issues with computational efficiency.

Nonetheless, RF still holds advantages in energy-efficient route planning, especially when multiple features (such as traffic conditions, weather, road conditions, etc.) need to be considered. By integrating various information sources, RF can provide accurate traffic flow predictions and support energy-efficient route planning. However, in intelligent transportation systems with high real-time demands, RF’s high computational complexity may become a performance bottleneck.

3.2.3. XGBoost and LightGBM

XGBoost and LightGBM are gradient boosting tree models that have excelled in various machine learning competitions (Sun et al., 2021). XGBoost optimizes decision tree structures through gradient boosting algorithms, demonstrating strong predictive power and computational efficiency. LightGBM, an improved version of XGBoost, enhances model speed and memory efficiency by optimizing data splitting algorithms and parallelization strategies (Zheng et al., 2024). These models perform excellently in large-scale datasets and high-frequency update scenarios, providing effective support for real-time traffic flow prediction.

However, the main challenge with XGBoost and LightGBM lies in the complexity of model tuning, especially when dealing with missing values and hyperparameter selection. Their performance is highly sensitive to these factors. In energy-efficient route planning, XGBoost and LightGBM can efficiently integrate traffic flow, road information, and energy efficiency demands for predictions, making them particularly useful in real-time dynamic adjustments for intelligent transportation systems. Nonetheless, when faced with large-scale traffic data and frequent updates, optimizing computational efficiency and reducing model tuning time remains a key challenge for future research.

3.3. Deep Learning Models

In recent years, deep learning has achieved significant progress in traffic flow prediction, particularly in handling complex spatiotemporal data. Models such as Convolutional Neural Networks (CNN), Long Short-Term Memory networks (LSTM), Gated Recurrent Units (GRU), and Spatiotemporal Graph Neural Networks (GNN) have emerged as key research focuses. These models are capable of capturing nonlinear characteristics of traffic flow and effectively modeling spatial and temporal dependencies within transportation networks, thereby providing robust technical support for tasks such as route planning and congestion forecasting in intelligent transportation systems.

3.3.1. Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs)

Originally developed for image processing tasks, CNNs have gained increasing attention for their ability to extract spatial features from time series data. Their strength lies in efficiently capturing local patterns through convolutional operations, making them well-suited for learning the spatial structure of road networks. However, CNNs are inherently limited in capturing temporal dependencies, often necessitating integration with other models, such as LSTM, to enhance their temporal modeling capabilities.

For instance, Zhang et al. (2024) proposed a CNN-LSTM hybrid model that effectively combines spatial feature extraction (via CNN) with temporal sequence modeling (via LSTM). This architecture has proven particularly effective for predicting traffic flow and energy consumption, which is crucial for electric vehicle route planning. By accounting for both traffic volumes and energy usage, the model enhances decision-making accuracy. Nevertheless, the CNN-LSTM combination faces challenges in processing high-dimensional data due to CNN’s computational complexity and prolonged training times, which may limit its practical applicability.

3.3.2. Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) and Gated Recurrent Units (GRU)

LSTM and GRU are advanced variants of Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs) designed to capture long-range dependencies in sequential data.

Figure 3 visually contrasts their internal gating mechanisms, helping clarify why GRU is computationally lighter yet functionally comparable to LSTM. LSTM's gated mechanisms mitigate the vanishing-gradient problem associated with traditional RNNs, making it highly effective for dynamic traffic-flow prediction. However, LSTM models often require large datasets and are sensitive to noise, which can hinder performance in data-scarce or noisy environments.

Abduljabbar et al. (2021) demonstrated the application of LSTM in short-term traffic forecasting, highlighting its strength in modeling complex temporal patterns, particularly in spatiotemporal speed-prediction tasks. Although LSTM excels at capturing short-term traffic fluctuations, it may underperform in extreme or unexpected scenarios compared with simpler machine-learning methods. In contrast, the GRU cell shown in

Figure 3(b) removes the separate output gate and merges input–forget gates into an update gate, thereby reducing parameter count by roughly 30 % while maintaining sequence-modelling capacity. Pirani et al. (2022) emphasized GRU’s efficiency and effectiveness in short-term forecasting, making it a strong candidate for real-time traffic-prediction applications.

(a) Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) cell with input (*i*), forget (*f*) and output (*o*) gates plus cell state. (b) Gated Recurrent Unit (GRU) cell that merges input–forget gates into an update gate and eliminates the output gate, yielding fewer parameters and faster convergence while preserving long-range-dependency learning.

3.3.3. Spatiotemporal Graph Neural Networks (GNNs)

GNNs have recently emerged as a powerful approach for modeling structured graph data, demonstrating considerable potential in transportation networks, which naturally form graph structures comprising nodes (intersections) and edges (roads). By leveraging Graph Convolutional Networks (GCNs) to extract spatial features and incorporating temporal modeling, GNNs can capture both spatial and temporal dependencies in traffic data.

Afandizadeh et al. (2024) reviewed GNN-based approaches in traffic prediction and highlighted their unique advantages in modeling spatiotemporal dependencies. Unlike conventional deep learning models, GNNs simultaneously model the topological and temporal dynamics of large-scale transportation networks, making them particularly suitable for real-time traffic forecasting and congestion detection. However, their high computational complexity and slower inference speed, especially when processing large datasets, remain key obstacles to widespread deployment.

3.4. Hybrid and Enhanced Approaches

Despite the progress achieved with individual deep learning models, no single approach can fully address the diverse and dynamic nature of traffic data. Consequently, researchers have increasingly explored hybrid and enhanced methods that integrate the strengths of different models to improve predictive accuracy and robustness.

3.4.1. Wavelet Denoising + XGBoost

The combination of wavelet denoising and Extreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost) has gained traction in traffic prediction tasks. Wavelet denoising effectively removes noise from traffic data, thereby improving data quality, while XGBoost—an efficient gradient boosting framework—performs well in learning from noisy datasets. Alsolami et al. (2020) reviewed this integrated approach, noting that wavelet denoising can eliminate high-frequency noise components, allowing XGBoost to better capture underlying traffic patterns and enhance prediction accuracy.

This method is particularly suited to scenarios involving noisy or low-signal traffic data. By reducing noise during the preprocessing stage, the subsequent prediction model (e.g., XGBoost) achieves better performance. However, its main drawback lies in the computational overhead required for denoising and modeling, which may hinder its applicability in real-time systems.

3.4.2. MLR-LSTM

Combining Multiple Linear Regression (MLR) with LSTM represents another widely used hybrid strategy. MLR captures linear relationships in traffic flow, while LSTM models nonlinear and complex temporal dependencies. Zhang et al. (2024) proposed an MLR-LSTM hybrid for predicting energy consumption in electric vehicles, where MLR is used for linear feature extraction and LSTM captures nonlinearity in sequential data. This integration effectively leverages the simplicity of traditional statistical models and the representational power of deep learning, making it suitable for various traffic prediction scenarios.

3.4.3. Dual Error Model (DEM)

The Dual Error Model (DEM) incorporates both model and observational errors to enhance the stability and accuracy of traffic prediction. Khatua et al. (2024) introduced a DEM-based federated learning framework that integrates data from multiple sources to improve prediction outcomes. This approach is well-suited for addressing the uncertainty and complexity inherent in traffic data. Nevertheless, a key challenge lies in efficiently fusing multiple sources of error while maintaining computational efficiency.

To better understand the strengths, limitations, and appropriate use cases of these methods, the following

Table 1. provides a comprehensive overview of various dynamic traffic flow prediction techniques, summarizing their key characteristics, advantages, and challenges based on recent research.

4. Theoretical Integration of Prediction Results in Energy-Saving Route Planning

4.1. Overview of the Theoretical Integrated Architecture

The theoretical integrated architecture in energy-efficient route planning is the core mechanism for achieving global energy optimization. By combining traffic flow prediction, dynamic cost function design, and path search algorithms, this approach can effectively respond to the dynamic changes in complex traffic networks, optimizing key indicators such as energy consumption, travel time, and carbon emissions. This section will provide a detailed explanation of the various components of this integrated architecture, analyze the findings and limitations of existing literature, and lay the foundation for further research in energy-efficient route planning.

4.1.1. Prediction Module

Traffic flow prediction is fundamental to energy-efficient route planning, as it provides real-time and future traffic status information essential for path optimization. In recent years, the rapid development of artificial intelligence (AI) technologies has significantly enhanced prediction accuracy, particularly in handling spatiotemporal correlations. Deep learning models such as Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) networks and Graph Convolutional Networks (GCN) have been widely applied in traffic flow prediction, as LSTM and GCN are effective at capturing the dynamic characteristics of traffic flow, making them suitable for both short-term and mid-term forecasting (Sayed et al., 2023).

However, existing models often rely on historical traffic data and sensor data, which still have limitations when addressing external factors like weather changes. The multi-source data fusion framework proposed by Al Duhayyim et al. (2022) has enhanced prediction robustness, but the reliance on extensive external data can lead to information overload, especially in complex urban traffic situations. Additionally, Kadkhodayi et al. (2023) emphasized the application of AI models in dynamic environments; however, their high computational complexity poses a challenge, with balancing prediction accuracy and computational efficiency remaining a key issue.

Although AI technologies excel in prediction accuracy, compared to traditional methods like ARIMA, the computational complexity of AI approaches is higher, and they demand more from hardware, which could limit their widespread real-time application. Therefore, finding the balance between prediction accuracy and computational efficiency is a crucial area for future research.

In practice, the input to the prediction module includes historical traffic data (such as flow and speed), real-time sensor data, and external variables (such as weather and events), while the output consists of predictions for traffic status on road segments for a future period. For example, LSTM may predict the road segment speed for the next 30 minutes, while GCN captures spatial dependencies through road network topology. These predictions provide input to the dynamic cost function, enabling the planning system to avoid congested areas, thereby reducing energy consumption and time costs. In comparison to traditional methods (like ARIMA), AI approaches excel in processing nonlinear data but require careful consideration of the trade-off between accuracy and computational efficiency (Sayed et al., 2023).

4.1.2. Dynamic Cost Function Design

The dynamic cost function is crucial in integrating the prediction results into energy-efficient route planning. It needs to comprehensively account for multiple objectives, such as travel time, energy consumption, distance, and carbon emissions. Unlike traditional path-planning algorithms, which primarily optimize a single objective (e.g., shortest path), energy-efficient route planning faces significant challenges in multi-objective optimization. Zhang et al. (2023) proposed an electric vehicle (EV) route planning algorithm based on dynamic programming, which adjusts the cost function in real-time to adapt to traffic changes and optimize both energy consumption and charging demand. Basso et al. (2022) used reinforcement learning to design a dynamic stochastic cost function, capable of adjusting weights in response to traffic uncertainties. However, effectively balancing different objectives, such as time and energy consumption, remains a critical issue.

The flexibility of this dynamic cost function design is advantageous but also faces the challenge of adjusting weights according to real-world scenarios. In the case of EV route planning, Lee et al. (2022) highlighted the importance of speed prediction for accurate energy consumption estimation, while Schoenberg & Dressler (2022) proposed a model that incorporates waiting times at charging stations, showing that adaptability in dynamic environments is still an area requiring in-depth exploration.

The dynamic cost function can be formalized as:

Where TTT represents travel time, EEE is energy consumption, and D is the distance. w1,w2,w3 are dynamic weights influenced by the predicted traffic state. For example, during congestion, w1 could be increased, or adjustments to E could reflect the higher energy consumption due to lower speeds. The flexibility of this design allows for real-time adaptation, but selecting the correct weights and balancing multiple objectives need to be fine-tuned according to specific scenarios (e.g., EV logistics or urban navigation) (Basso et al., 2022).

4.1.3. Path Search Algorithm Overview

The efficiency of path search algorithms in dynamic environments directly impacts the effectiveness of energy-efficient route planning. Dai et al. (2021) proposed the Parallel Traffic Condition-Driven Path Planning (PARP) model, which dynamically updates weights and quickly adapts to traffic changes, though its computational load remains substantial. Enhancing the computational efficiency of such algorithms remains a challenge. Moreover, genetic algorithms have shown promise in global searches for multi-objective optimization, particularly in balancing energy consumption and travel time (Aung et al., 2023), but efficiently finding the optimal path in complex traffic networks still requires further work.

The A* algorithm is widely used in real-time navigation due to its heuristic search properties, with its performance depending on the design of the heuristic function h(n), which can be optimized using traffic predictions (Jose & Grace, 2022). Genetic algorithms excel in multi-objective optimization, particularly in balancing energy consumption, time, and distance (Aung et al., 2023). Wu et al. (2022), based on dynamic nonlinear model predictive control, proposed a smart transportation system path planning method that emphasizes the role of prediction data in enhancing algorithm efficiency. However, the Dijkstra algorithm's performance in dynamic environments is limited by frequent weight updates, and therefore needs to integrate prediction modules to reduce recalculation frequency.

Collectively, the prediction module provides traffic status forecasts, the cost function guides the path search algorithm, and the combined system ultimately achieves energy-saving goals. The selection of algorithms must balance real-time requirements and solution quality, with A* suitable for rapid responses and genetic algorithms more appropriate for global optimization (Dai et al., 2021; Aung et al., 2023).

4.2. Review of Classical Path Search Algorithms

Path search algorithms play a critical role in energy-efficient route planning, directly influencing how predictive results are translated into practical decisions for optimizing energy consumption, travel time, and carbon emissions. With well-established theoretical foundations and extensive application scenarios, classical algorithms remain highly relevant in dynamic traffic environments. The A* algorithm is known for its efficiency, Dijkstra’s algorithm guarantees global optimality, and multi-objective genetic algorithms (MOGA) are adept at balancing competing objectives. By analyzing their principles, applications, and limitations, and incorporating recent research, it is clear that current approaches face a notable trade-off between real-time performance and global optimization. This underscores the need for exploring hybrid strategies to enhance energy efficiency.

4.2.1. A* Algorithm

A* is a best-first heuristic search that combines the cumulative cost from the start node to a given node g(n)g(n)g(n) and an estimated cost from that node to the goal h(n) into a single priority function f(n)=g(n)+h(n). Here, h(n) may be computed using Euclidean distance, Manhattan distance, Chebyshev distance, or even domain-specific estimators, provided it never overestimates the true cost (admissibility) and ideally remains consistent (monotonicity). By directing the search toward the goal, A* can reduce node expansions by roughly 30 %–50 % compared with uninformed approaches such as Dijkstra’s algorithm, thereby significantly lowering computation time in real-time applications.

In dynamic routing scenarios, A* has proven remarkably adaptable. For electric-vehicle path planning, Sebai et al. (2022) integrated traffic-flow predictions and real-time incident data into both the cost and heuristic models; against Dijkstra and D* Lite benchmarks, their method achieved over 20 % reductions in both energy consumption and travel time. Likewise, Gan et al. (2022) enhanced inland-vessel routing by embedding a safety-potential field into the heuristic function, which lowered collision-risk metrics by 35 % while maintaining efficient voyage times. More recently, Chen et al. (2023) demonstrated that incorporating live traffic-signal status into A*’s evaluation can help vehicles avoid red-light delays, cutting average journey times by 15 %.

Despite these successes, A*’s performance remains heavily dependent on the quality of its heuristic. If h(n) violates admissibility or consistency, the algorithm may re-expand nodes and suffer ballooning search costs. Ben Abbes et al. (2022) emphasize that overly simplistic heuristics in complex network topologies can yield suboptimal routes, while high-frequency cost updates in large-scale graphs can render real-time operation infeasible. Consequently, although A* excels in moderately complex, latency-sensitive tasks such as urban navigation, it may not be the best choice when strict global optimality or extreme scalability is required. In such contexts, incremental planners like D* or LPA* or sampling-based methods such as RRT* and PRM* often offer more robust guarantees.

4.2.2. Dijkstra Algorithm

Dijkstra’s algorithm adopts a greedy strategy, expanding the search step-by-step to ensure the globally shortest path in graphs without negative weights. Although its time complexity is O(V²), it can be optimized to O((V + E) log V) using priority queues, making it well-suited for static networks due to its simplicity and optimality. Ben Abbes et al. (2022) applied it to electric vehicle routing by integrating energy models and charging station locations, resulting in optimized path selection. Asna et al. (2021) also confirmed its reliability in fast-charging station planning in the UAE, especially under static conditions.

However, dynamic traffic environments expose Dijkstra’s limitations. Bac et al. (2021) noted that each traffic state change (e.g., congestion or time window adjustments) requires recomputation of the entire network, significantly reducing efficiency, especially in scenarios involving partial charging or large-scale networks. Chen et al. (2023) attempted to alleviate this burden using traffic flow prediction, yet the computational load of global search remains a challenge. In my view, Dijkstra is more appropriate for relatively stable conditions and needs to be augmented with predictive techniques when applied to real-time dynamic settings.

4.2.3. Multi-Objective Genetic Algorithm (MOGA)

Multi-objective genetic algorithms (MOGAs) have emerged as a unifying framework for reconciling the competing demands of energy consumption, travel time, emissions and safety in intelligent transportation systems. Rather than a mere collection of evolutionary operators, MOGA serves as a narrative thread: it weaves together disparate studies into a coherent exploration of trade-offs, even as it confronts the dual challenges of translating Pareto-optimal solutions into real-world practice and meshing time-intensive offline search with the urgency of live operations.

Early applications of MOGA in vehicle scheduling illustrate both its promise and its limitations. For instance, Zhao et al. (2023) integrate short-term traffic-flow forecasts directly into the algorithm’s fitness evaluations, cutting energy use by 12 percent at the cost of only a five-minute delay. Their work exemplifies prediction-informed evolution, yet stops short of addressing the leap from simulation to live fleet dispatch. Ma et al. (2022) extend the approach to highway work zones, optimizing safety margins alongside energy metrics; however, their scenarios remain geographically narrow, leaving open the question of network-wide applicability.

Beyond routing, MOGA’s versatility shows in infrastructure design problems such as charging-station placement and electric multiple-unit energy management. Asna et al. (2021) and Fischer et al. (2025) employ Pareto fronts to illuminate the trade-offs among cost, demand and grid stability, yet seldom reconnect those insights to the operational algorithms that handle real-time rerouting or dispatch. Aghili’s (2025) case study in Isfahan begins to bridge this gap by jointly considering station siting and fleet routing, though it still leaves unanswered how fluctuating ridership patterns might dynamically reshape the Pareto landscape.

Underneath MOGA’s broad applicability lie significant computational hurdles. Its native ability to handle four or more objectives distinguishes it from scalarization-based methods, but at the price of heavy fitness-evaluation workloads (Mu et al. 2021; Gao et al. 2025). Attempts to streamline the search—whether by task slicing and cache optimization (Sifeng et al. 2025), surrogate models that approximate expensive evaluations (Xiong et al. 2024), or federated multi-agent architectures that distribute computation to edge nodes (Mamond et al. 2025)—offer incremental relief but often introduce new challenges, from approximation error to data-heterogeneity and convergence consistency.

Two overarching research gaps stand out. First, no existing pipeline convincingly delivers city-scale MOGA solutions in sub-minute times under live traffic conditions: warm-starts with A* or Dijkstra heuristic searches help, but convergence criteria remain ad hoc rather than principled. Second, studies tend to isolate a single planning layer—dispatch, infrastructure design or traffic prediction—whereas real urban mobility requires an end-to-end, dynamically coordinated ecosystem. The next frontier lies in architecting a modular, layered framework: fast heuristics would seed solutions in real time, genetic search would refine long-term strategies, and surrogate models would prevent staleness. Embedding MOGA as an evolving, interactive component—rather than treating it as a standalone black box—promises to unlock both its academic potential and its practical impact.

4.3. Integration Mode Comparison from Literature: A Critical Analysis

This section provides a comprehensive comparison of integration modes, emphasizing the importance of linking theoretical frameworks to practical applications in route planning systems. By analyzing relevant case studies, this section not only examines existing literature but also critiques the strengths, limitations, and potential improvements of different integration strategies. Through a synthesis of previous work, we aim to identify gaps in current methodologies and propose pathways for advancing research in this field.

4.3.1. "Prediction → A" Fast Response Mode*

The "Prediction → A*" fast response mode, a commonly employed strategy in real-time traffic management, leverages real-time traffic predictions to dynamically adjust routing decisions using the A* algorithm. This model is frequently applied in scenarios where immediate adjustments to traffic conditions are required, such as real-time navigation. For instance, Sebai et al. (2022) in Optimal Electric Vehicles Route Planning with Traffic Flow Prediction and Real-Time Traffic Incidents demonstrate the practical application of this model in adaptive routing for electric vehicles.

Workflow: The model operates by first predicting traffic flow and subsequently updating the graph weights accordingly. Using the updated graph, the A* algorithm identifies a new optimal path.

Critical Analysis: The A* algorithm, while efficient, faces inherent limitations. One of the key concerns is its susceptibility to converging on local optima, especially in complex and highly dynamic environments. The real-time nature of this model makes it computationally attractive; however, this speed comes at the expense of solution quality. The trade-off between computation time and solution quality is an ongoing challenge in real-time systems. While the model excels in scenarios demanding quick decisions, its ability to consistently provide the best possible route in complex traffic conditions remains an area for improvement.

Contribution: This approach is best suited for applications requiring rapid response times, such as GPS navigation and real-time route adjustments for electric vehicles. However, future work could explore hybrid models that combine the speed of A* with global optimization methods to address its limitations in complex scenarios.

4.3.2. "Prediction → Genetic Optimization" Global Optimal Mode

In contrast, the "Prediction → Genetic Optimization" model seeks to optimize long-term route planning by utilizing traffic flow predictions as input to a genetic algorithm, which evolves potential solutions over time. Zhao et al. (2023) in Path Planning Based on Traffic Flow Prediction for Vehicle Scheduling provide an in-depth exploration of this model, applying it to vehicle scheduling for large-scale logistics.

Workflow: This model begins by predicting long-term traffic trends and utilizes a genetic algorithm to optimize solutions. The algorithm iteratively evolves a population of routes, optimizing multiple objectives such as energy consumption, travel time, and traffic congestion.

Critical Analysis: While this model excels in optimizing multi-objective functions and providing global optimal solutions, its major drawback is the significant computational overhead required. Genetic algorithms are inherently slower than methods like A*, and this limits their practical application in real-time scenarios. The time required for genetic optimization to converge on a global optimum makes it impractical for fast-response applications. Furthermore, the complexity of multi-objective optimization introduces additional challenges in balancing conflicting goals, such as minimizing energy consumption while reducing travel time.

Contribution: This approach is best suited for scenarios requiring long-term planning, such as fleet management and large-scale logistics optimization. Future research could explore hybrid methods that incorporate genetic algorithms for offline optimization while using faster, real-time models for immediate route adjustments.

4.3.3. Comparative Theoretical Analysis of Methods

The comparison of the two integration modes—"Prediction → A*" and "Prediction → Genetic Optimization"—is summarized in

Table 2. This table synthesizes findings from existing studies, providing a clearer understanding of the computational efficiency, solution quality, and applicable scenarios for each mode.

Critical Insights: The "Prediction → A*" mode is highly efficient but sacrifices solution quality in complex environments, making it ideal for real-time navigation where speed is paramount. However, it is clear that the application of A* is limited in scenarios that require more than quick fixes—complex traffic conditions demand methods that can optimize for global solutions. In contrast, the "Prediction → Genetic Optimization" mode offers superior global optimization capabilities, making it suitable for complex, multi-objective problems. However, its computational expense makes it unsuitable for real-time applications where rapid decisions are essential.

Contributions to the Field: This section highlights a critical gap in current research—the need for hybrid approaches that combine the strengths of both modes. Real-time applications would benefit from models that integrate the speed of the A* algorithm with the optimality of genetic optimization. Further exploration of hybrid models, such as combining A* with machine learning techniques for global optimization or integrating genetic algorithms with faster heuristic methods, could provide a promising avenue for future work.

Conclusion and Recommendations: The integration mode chosen must align with the application's requirements. For real-time scenarios, the "Prediction → A*" fast response mode remains the most practical due to its computational efficiency. For long-term planning, especially in logistics or fleet management, the "Prediction → Genetic Optimization" model is preferred, though it requires careful consideration of its computational demands. Future work should focus on developing hybrid models that can leverage the advantages of both approaches to achieve real-time performance while maintaining global optimality.

5. Research Gaps, Challenges, and Future Directions

The interdisciplinary field of energy-efficient route planning and traffic flow prediction has experienced rapid advancement in recent years. However, limitations in data quality, algorithmic efficiency, technological integration, and personalized demand remain substantial barriers to large-scale real-world deployment. This section provides an in-depth discussion of these critical issues, evaluates current research limitations, and synthesizes insights from recent literature to propose forward-looking recommendations aimed at enhancing the effectiveness and sustainability of intelligent transportation systems.

5.1. Data Dimension: Quality, Coverage, and Privacy Compliance

High-quality data constitute the foundation of accurate traffic prediction and route planning. Nevertheless, current datasets exhibit significant deficiencies that impair model generalizability and performance. Abduljabbar et al. (2021) and Afandizadeh et al. (2024) highlighted considerable spatiotemporal gaps in existing traffic datasets, especially under rural road conditions or extreme weather events, where noise and missing values are prevalent, leading to reduced prediction accuracy. For instance, while urban arterial roads are well-represented in datasets, data scarcity in remote areas causes performance imbalances when models are applied to entire road networks (Chen et al., 2024). Alsolami et al. (2020) further pointed out that technical and regulatory barriers hinder cross-regional data integration, limiting opportunities for global optimization.

Privacy concerns further complicate data acquisition. With the enforcement of regulations such as the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), the collection of vehicle trajectories and user behavioral data faces strict constraints (Khatua et al., 2024). While federated learning and differential privacy have been proposed as potential solutions, their application in transportation remains nascent, with data sharing efficiency still limited (Madupuri et al., 2024). Future research should prioritize the development of high-quality heterogeneous datasets that encompass multimodal transport (e.g., walking, public transit, vehicular traffic) and cover both urban and rural areas, while integrating privacy-preserving technologies to ensure regulatory compliance. For example, the federated learning approach proposed by Khatua et al. (2024) facilitates cross-national collaborative model training, and the open multimodal datasets advocated by Chen et al. (2022) offer a solid foundation for energy-efficient planning.

5.2. Algorithmic Dimension: Trade-Offs in Real-Time Performance, Scalability, and Interpretability

Algorithm design for energy-efficient route planning encounters multiple challenges. Deep learning models such as Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) networks and Transformers demonstrate superior accuracy (Abduljabbar et al., 2021; ArunKumar et al., 2022; Dubey et al., 2021), but their high computational cost limits their suitability for real-time applications. In electric vehicle navigation, where traffic conditions change rapidly, lightweight models such as Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) respond quickly but often sacrifice accuracy (Pirani et al., 2022). Many existing algorithms are designed for small-scale networks; when scaled to interregional networks or fleet-level dispatching, computational efficiency and memory requirements become significant bottlenecks (Dai et al., 2021; Li et al., 2022a; Li et al., 2022b).

The "black-box" nature of AI models undermines trust in critical applications such as traffic control and autonomous driving (D’Angelo & Palmieri, 2021). Insufficient interpretability not only impedes real-world deployment but also restricts the optimization of decision-making processes (Knigge et al., 2023). Hybrid frameworks may offer a viable solution—for instance, integrating the transparency of A* algorithms with the predictive power of deep learning (Sebai et al., 2022; Jose & Vijula Grace, 2022), or leveraging edge computing to enhance real-time responsiveness (Chen et al., 2022). Advancements in scalability, such as the development of distributed algorithms for large-scale networks (Dai et al., 2021; Li et al., 2022b), could significantly enhance the practical utility of energy-efficient planning.

5.3. Integration of Emerging Technologies: IoT/5G, Vehicular Networks, and Digital Twins

The Internet of Things (IoT) and 5G technologies provide massive real-time data and low-latency communication capabilities (Liu et al., 2023). Vehicular networks (V2X) enable cooperative sensing among vehicles for optimized routing (Aung et al., 2023), while digital twin systems offer virtual simulations that enhance prediction accuracy (Chandra, 2025; Irfan et al., 2024). Despite their promise, the full potential of these technologies has yet to be realized. While IoT and 5G contribute rich data, efficient processing and cybersecurity remain unresolved challenges (Madupuri et al., 2024). Vehicular networks face privacy issues and a lack of interoperability due to slow progress in standardizing communication protocols (Khatua et al., 2024). Software-defined vehicular networks, however, offer a flexible approach to optimize traffic efficiency through data-driven V2X coordination (Shahriar et al., 2024), supporting real-time path planning in frameworks like “Prediction → A*.”

Digital twins, although promising, entail high computational costs for accurate modeling (Chandra, 2025). For example, real-time construction of a digital twin for urban traffic requires extensive sensor input and physical modeling, which is currently only feasible in pilot-scale implementations (Chen et al., 2024). Recent advances leverage LiDAR data to create localized digital twins for data-driven traffic simulation, reducing computational overhead while maintaining accuracy (Wibisana, 2024). Specific applications include adaptive traffic signal control under limited synchronization conditions, where digital twins enhance prediction robustness for urban networks (Zhu et al., 2024), and traffic guidance for autonomous driving, integrating V2X data for energy-efficient routing (Liao et al., 2024). These developments align with the article’s proposed integration of prediction and optimization models.

Future directions may include the development of 5G-based vehicular data platforms (Liu et al., 2023) or the application of digital twins to dynamic traffic forecasting across diverse scenarios, such as extreme weather or peak-hour congestion (Chandra, 2025; Irfan et al., 2024). Addressing security, standardization, and computational challenges will be critical to advancing the intelligence level of energy-efficient planning.

5.4. Multimodal Transportation and Personalized Route Planning

Urban mobility is increasingly characterized by truly multimodal journeys—users may cycle to a metro station, ride the train, and then transfer to a bus within a single trip. Yet most studies remain confined to a single transport mode, lacking the ability to orchestrate real-time data streams, energy-conscious spatial constraints, and regulatory considerations in an integrated fashion (Alfaseeh & Farooq, 2020; Sachanbińska-Dobrzyńska, 2023). For example, in the “bike→metro→bus” scenario, existing algorithms struggle to balance transfer wait times, network-wide energy consumption, and passenger comfort (Agrahari et al., 2024; Stremke & Koh, 2010; Stoeglehner & Narodoslawsky, 2012), and they rarely account for legal frameworks or ecological design guidelines that shape urban form and energy potential (Van den Dobbelsteen et al., 2012; Sachanbińska-Dobrzyńska, 2023).

Moreover, individual travelers prioritize different objectives—some seek minimum energy use, others shortest travel time or highest comfort—yet general-purpose models lack the dynamic, profile-driven adaptability to satisfy these divergent needs (Tiwari et al., 2023; Jiang et al., 2022; Golrezaei et al., 2014). To address these gaps, we advocate for a unified multimodal transport-data platform augmented by personalized, reinforcement-learning and real-time optimization modules. For instance:

- (1)

Dynamic route adaptation: Basso et al. (2022) demonstrate how a reinforcement-learning agent can continuously recalibrate route recommendations to optimize both energy use and travel time.

- (2)

Real-time synchronization: Chen et al. (2023) show that techniques drawn from industrial online scheduling can improve transfer timing and fleet utilization (Oberwinkler & Stundner, 2005; Diehl, 2001).

- (3)

Holistic sustainability framework: By embedding quantitative indices of environmental, legal and social performance (Goldman & Gorham, 2006; Boschmann & Kwan, 2008; Gudmundsson & Regmi, 2017), the platform can simultaneously satisfy energy-efficiency, compliance, and equity objectives.

Table 3.

Literature summary on Energy Optimization and Urban Transportation Systems.

Table 3.

Literature summary on Energy Optimization and Urban Transportation Systems.

| Reference |

Core Method / Perspective |

Application & Value |

| Stremke & Koh (2010) |

Ecological design strategies for energy-conscious spatial planning |

Provides principles for land-use layouts that reduce energy demand and support multimodal hubs |

| Sachanbińska-Dobrzyńska (2023) |

Comparative legal analysis |

Highlights Poland/Germany regulatory frameworks to ensure algorithmic planning remains compliant |

| Stoeglehner & Narodoslawsky (2012) |

Strategic planning for energy-optimized urban structures |

Austrian case studies illustrating coordination of urban form with district-scale energy systems |

| Van den Dobbelsteen et al. (2012) |

Energy-potential and thermal-mapping techniques |

Develops GIS-based maps to identify low-energy corridors and transfer nodes |

| Jiang et al. (2022) |

Flexible job-shop scheduling with transport and deterioration |

Introduces dual constraints of travel time and equipment aging, inspiring multimodal scheduling |

| Oberwinkler & Stundner (2005) |

Real-time production optimization |

Adapts industrial online scheduling algorithms for dynamic transit vehicle dispatch |

| Golrezaei et al. (2014) |

Real-time optimization of personalized assortments |

Validates user-profile-driven decision frameworks in retail, offering insights for transport choices |

| Diehl (2001) |

Online optimization for large-scale nonlinear processes |

Offers algorithmic foundations for high-dimensional, constrained real-time optimization |

| Goldman & Gorham (2006) |

Four innovative directions in sustainable urban transport |

Proposes macro-strategies (e.g. demand management, technological integration) for multimodal systems |

| Boschmann & Kwan (2008) |

Social sustainability in urban transportation |

Emphasizes equity and accessibility metrics to enrich user-satisfaction dimensions |

| Gudmundsson & Regmi (2017) |

Sustainable Urban Transport Index (SUTI) |

Constructs a composite indicator for benchmarking multimodal network performance |

5.5. Recommendations: Standardized Evaluation Platforms and Open-Source Toolkits

Imagine a city planner logging into a single portal that instantly benchmarks her new routing algorithm against a standardized metric suite—from base-level travel-time and energy-use indicators (Marsh, 1995; Sears et al., 2013) to passenger-perception scores drawn from a validated survey instrument (Verma, 2025). Behind the scenes, each experiment also feeds into a prioritization module (Turochy, 2001) that ranks proposed network upgrades by cost, social benefit and CO₂ reduction, and an investment-appraisal dashboard modeled on the Dutch standardized framework (Annema et al., 2007).

To bring this vision to life, we recommend three intertwined pillars:

Unified Evaluation Backbone

Core metrics registry: Adopt a minimal yet extensible set of “must-report” indicators (Marsh, 1995; Shi, 2018) covering throughput, delay, energy-use per passenger-km, emissions, and service quality ratings (Verma, 2025).

Pluggable appraisal engines: Embed modules for cost–benefit analysis (Annema et al., 2007), energy-efficiency utility modeling (Sears et al., 2013), and multi-criteria ranking (Turochy, 2001), so every study yields comparable scores.

Open-Source, Modular Toolkit

Data & model registry: A repository of canonical datasets (urban/rural/ highway), reference algorithms (GCNs, A*, RL planners) and pre-built connectors to GIS and traffic simulators, all versioned and containerized (Shi, 2018).

Survey & perception plug-in: Standardized forms and analytics scripts for gathering and integrating commuter feedback (Verma, 2025; Chatterjee et al., 2025).

Community-Driven Governance & Evolution

Rotating steering group of academics, practitioners, and policymakers to ratify new metrics, datasets, and modules—ensuring the platform reflects emerging needs (Shi, 2018).

Living documentation and hackathons to crowdsource additions, troubleshoot reproducibility gaps, and showcase real-world deployments.

By weaving together decades of methodological advances—from base-level metric standardization (Marsh, 1995) and investment evaluation (Annema et al., 2007) to energy-utility modeling (Sears et al., 2013) and legal/operational management systems (Shi, 2018)—this ecosystem will transform isolated proofs-of-concept into a shared, evolving infrastructure. Researchers gain immediate comparability; practitioners access turn-key tools; and policymakers receive transparent, data-backed ranking of every proposed improvement. In effect, the field transcends ad hoc experiments and enters a new era of rapid, reproducible innovation and real-world impact.

6. Conclusion

This review comprehensively examined recent advancements in traffic flow prediction and energy-efficient route planning, underscoring the pivotal role of AI technologies in enhancing prediction accuracy and route optimization—particularly through deep learning models. Through a critical comparison with traditional pathfinding algorithms, it was found that while deep learning models excel in accuracy, their limitations in real-time responsiveness and interpretability necessitate integration with conventional methods. Emerging technologies such as IoT, 5G, and digital twins have introduced novel pathways for innovation, although practical deployment remains constrained by technical and regulatory challenges. The unique contribution of this study lies in its proposal of an integrated theoretical framework that emphasizes the importance of data quality, algorithmic efficiency, and personalized demand in cross-domain system design for energy-efficient planning.

Nonetheless, as a literature-based review, the study did not conduct empirical validation or algorithmic benchmarking, which may limit the generalizability of some conclusions, especially in light of regional disparities in transportation systems. Future studies incorporating case-based analysis and quantitative experiments are expected to enhance the credibility of findings. In summary, future research in intelligent transportation should focus on improving data quality and coverage, exploring privacy-preserving technologies for data sharing, developing lightweight and interpretable AI models, and integrating traditional algorithms to improve real-time and global performance. Furthermore, the convergence of IoT, 5G, and digital twins should be advanced to overcome challenges related to security and standardization. Building multimodal and personalized planning systems will address diverse user needs, while standardized evaluation platforms and open-source tools will catalyze technological advancement. These directions will collectively contribute to a high-efficiency, low-emission, and secure future for intelligent transportation systems, aligned with the goals of sustainable urban development.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Pengyang Qi and Chaofeng Pan; Methodology, Pengyang Qi and Chaofeng Pan; Literature Search & Data Curation, Pengyang Qi, Xing Xu, and Jian Wang; Writing–Original Draft Preparation, Pengyang Qi; Writing–Review & Editing, Pengyang Qi, Chaofeng Pan, Jun Liang, and Weiqi Zhou; Supervision, Jian wang; Funding Acquisition, Chaofeng Pan. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China, grant number 52272367.

References

- Abduljabbar, R.L.; Dia, H.; Tsai, P.-W.; Liyanage, S. Short-Term Traffic Forecasting: An LSTM Network for Spatial-Temporal Speed Prediction. Futur. Transp. 2021, 1, 21–37. [CrossRef]

- Afandizadeh, S.; Abdolahi, S.; Mirzahossein, H.; Li, R. Deep Learning Algorithms for Traffic Forecasting: A Comprehensive Review and Comparison with Classical Ones. J. Adv. Transp. 2024, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Agrahari, A.; Dhabu, M.M.; Deshpande, P.S.; Tiwari, A.; Baig, M.A.; Sawarkar, A.D. Artificial Intelligence-Based Adaptive Traffic Signal Control System: A Comprehensive Review. Electronics 2024, 13, 3875. [CrossRef]

- Alfaseeh, L.; Farooq, B. Multi-Factor Taxonomy of Eco-Routing Models and Future Outlook. J. Sensors 2020, 2020, 1–10. [CrossRef]

- Al Duhayyim, M.; Albraikan, A.A.; Al-Wesabi, F.N.; Burbur, H.M.; Alamgeer, M.; Hilal, A.M.; Hamza, M.A.; Rizwanullah, M. Modeling of Artificial Intelligence Based Traffic Flow Prediction with Weather Conditions. Comput. Mater. Contin. 2022, 71, 3953–3968. [CrossRef]

- Alsolami, B.; Mehmood, R.; Albeshri, A. (2020). Hybrid statistical and machine learning methods for road traffic prediction: A review and tutorial. In Smart Infrastructure and Applications: Foundations for Smarter Cities and Societies (pp. 115–133).

- ArunKumar, K.; Kalaga, D.V.; Kumar, C.M.S.; Kawaji, M.; Brenza, T.M. Comparative analysis of Gated Recurrent Units (GRU), long Short-Term memory (LSTM) cells, autoregressive Integrated moving average (ARIMA), seasonal autoregressive Integrated moving average (SARIMA) for forecasting COVID-19 trends. Alex. Eng. J. 2022, 61, 7585–7603. [CrossRef]

- Asna, M.; Shareef, H.; Achikkulath, P.; Mokhlis, H.; Errouissi, R.; Wahyudie, A. Analysis of an Optimal Planning Model for Electric Vehicle Fast-Charging Stations in Al Ain City, United Arab Emirates. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 73678–73694. [CrossRef]

- Aung, N.; Dhelim, S.; Chen, L.; Lakas, A.; Zhang, W.; Ning, H.; Chaib, S.; Kechadi, M.T. VeSoNet: Traffic-Aware Content Caching for Vehicular Social Networks Using Deep Reinforcement Learning. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2023, 24, 8638–8649. [CrossRef]

- Bac, U.; Erdem, M. Optimization of electric vehicle recharge schedule and routing problem with time windows and partial recharge: A comparative study for an urban logistics fleet. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2021, 70. [CrossRef]

- Basso, R.; Kulcsár, B.; Sanchez-Diaz, I.; Qu, X. Dynamic stochastic electric vehicle routing with safe reinforcement learning. Transp. Res. Part E: Logist. Transp. Rev. 2022, 157. [CrossRef]

- Ben Abbes, S., Rejeb, L., & Baati, L. (2022). Route planning for electric vehicles. IET Intelligent Transport Systems, 16(7), 875–889.

- Chandra, S. (2025). Sustainable Urban Mobility and Smart Traffic Management: Balancing Optimization With Environmental Sustainability Goals. In Machine Learning and Robotics in Urban Planning and Management (pp. 227–244). IGI Global.

- Chen, R., & Chen, B. (2024, October). Traffic State Estimation Using Basic Safety Messages Based on Kalman Filter Technique. In 2024 IEEE 6th International Conference on Civil Aviation Safety and Information Technology (ICCASIT) (pp. 1601–1610). IEEE.

- Chen, S., Wen, H., & Wu, J. (2022). Artificial intelligence based traffic control for edge computing assisted vehicle networks. Journal of Internet Technology, 23(5), 989–996.

- Chen, W., Liu, B., Han, W., Li, G., & Song, B. (2023, October). Dynamic path planning based on traffic flow prediction and traffic light status. In International Conference on Algorithms and Architectures for Parallel Processing (pp. 419–438). Springer.

- Chen, X.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, J. Traffic prediction forInternet of Thingsthrough support vector regression model. Internet Technol. Lett. 2021, 5, e336. [CrossRef]

- D’aNgelo, G.; Palmieri, F. Network traffic classification using deep convolutional recurrent autoencoder neural networks for spatial–temporal features extraction. J. Netw. Comput. Appl. 2021, 173. [CrossRef]

- Dai, T.; Li, B.; Yu, Z.; Tong, X.; Chen, M.; Chen, G. PARP: A Parallel Traffic Condition Driven Route Planning Model on Dynamic Road Networks. ACM Trans. Intell. Syst. Technol. 2021, 12, 1–24. [CrossRef]

- Dubey, A.K.; Kumar, A.; García-Díaz, V.; Sharma, A.K.; Kanhaiya, K. Study and analysis of SARIMA and LSTM in forecasting time series data. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assessments 2021, 47. [CrossRef]

- Gan, L.; Yan, Z.; Zhang, L.; Liu, K.; Zheng, Y.; Zhou, C.; Shu, Y. Ship path planning based on safety potential field in inland rivers. Ocean Eng. 2022, 260. [CrossRef]

- Gao, Z.; Wu, Z.; Hao, W.; Long, K.; Byon, Y.-J.; Long, K. Optimal Trajectory Planning of Connected and Automated Vehicles at On-Ramp Merging Area. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2021, 23, 12675–12687. [CrossRef]

- He, M.; Lake, P. Artificial Intelligence-Based Traffic Signal Control for Urban Transportation Systems. 2024 IEEE Integrated STEM Education Conference (ISEC). pp. 1–1.

- Jia, S., Peng, H., & Liu, S. (2009). Review of transportation and energy consumption related research. Journal of Transportation Systems Engineering and Information Technology, 9(3), 6–16.

- Jose, C.; Grace, K.S.V. Optimization based routing model for the dynamic path planning of emergency vehicles. Evol. Intell. 2020, 15, 1425–1439. [CrossRef]

- Kadkhodayi, A., Jabeli, M., Aghdam, H., & Mirbakhsh, S. (2023). Artificial intelligence-based real-time traffic management. Journal of Electrical Electronics Engineering, 2(4), 368–373.

- Khatua, S.; De, D.; Maji, S.; Maity, S.; Nielsen, I.E. A federated learning model for integrating sustainable routing with the Internet of Vehicular Things using genetic algorithm. Decis. Anal. J. 2024, 11. [CrossRef]

- Knigge, D. M., Romero, D. W., Gu, A., Gavves, E., Bekkers, E. J., Tomczak, J. M., ... & Sonke, J. J. (2023). Modelling long range dependencies in nd: From task-specific to a general purpose CNN. arXiv preprint arXiv:2301.10540.

- Lee, H.; Kim, K.; Kim, N.; Cha, S.W. Energy efficient speed planning of electric vehicles for car-following scenario using model-based reinforcement learning. Appl. Energy 2022, 313. [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Dai, T.; Chen, W.; Song, X.; Zang, Y.; Huang, Z.; Lin, Q.; Cai, K. T-PORP: A Trusted Parallel Route Planning Model on Dynamic Road Networks. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2022, 24, 1238–1250. [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Liu, Z.; Wang, X. Public charging station localization and route planning of electric vehicles considering the operational strategy: A bi-level optimizing approach. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2022, 87. [CrossRef]

- Liang, G.; U, K.; Ning, X.; Tiwari, P.; Nowaczyk, S.; Kumar, N. Semantics-Aware Dynamic Graph Convolutional Network for Traffic Flow Forecasting. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2023, 72, 7796–7809. [CrossRef]

- Lin, B.; Du, Z. How China׳s urbanization impacts transport energy consumption in the face of income disparity. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2015, 52, 1693–1701. [CrossRef]

- Lin, G.; Lin, A.; Gu, D. Using support vector regression and K-nearest neighbors for short-term traffic flow prediction based on maximal information coefficient. Inf. Sci. 2022, 608, 517–531. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Huo, L.; Zhang, X.; Wu, J. A Multi-Objective Resource Pre-Allocation Scheme Using SDN for Intelligent Transportation System. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2023, 25, 571–586. [CrossRef]

- Madupuri, R.P.; Sobin, C.; Enduri, M.K.; Anamalamudi, S. (2024). Swarm Intelligence in IoT and Edge Computing. In Swarm Intelligence (pp. 32–54). CRC Press.

- Ma, W.; Chen, B.; Yu, C.; Qi, X. Trajectory Planning for Connected and Autonomous Vehicles at Freeway Work Zones under Mixed Traffic Environment. Transp. Res. Rec. J. Transp. Res. Board 2022, 2676, 207–219. [CrossRef]

- Mirbakhsh, S. (2023). Artificial intelligence-based real-time traffic management review article. Journal of Electrical and Electronics Engineering, 2(4), 368–373.

- B, P.K.; K, H.; M.S.K., M. Hybrid long short-term memory deep learning model and Dijkstra’s Algorithm for fastest travel route recommendation considering eco-routing factors. Transp. Lett. 2023, 15, 926–940. [CrossRef]

- Mu, C.; Du, L.; Zhao, X. Event triggered rolling horizon based systematical trajectory planning for merging platoons at mainline-ramp intersection. Transp. Res. Part C: Emerg. Technol. 2021, 125. [CrossRef]

- Mystakidis, A.; Koukaras, P.; Tjortjis, C. Advances in Traffic Congestion Prediction: An Overview of Emerging Techniques and Methods. Smart Cities 2025, 8, 25. [CrossRef]

- Peng, N.; Xi, Y.; Rao, J.; Ma, X.; Ren, F. Urban Multiple Route Planning Model Using Dynamic Programming in Reinforcement Learning. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2021, 23, 8037–8047. [CrossRef]

- Pirani, M., Thakkar, P., Jivrani, P., Bohara, M. H., & Garg, D. (2022). A comparative analysis of ARIMA, GRU, LSTM and BiLSTM on financial time series forecasting. 2022 IEEE International Conference on Distributed Computing and Electrical Circuits and Electronics (ICDCECE), 1–6.

- Reza, I.; Ratrout, N.T.; Rahman, S.M. Artificial Intelligence-Based Protocol for Macroscopic Traffic Simulation Model Development. Arab. J. Sci. Eng. 2021, 46, 4941–4949. [CrossRef]

- Sayed, S.A.; Abdel-Hamid, Y.; Hefny, H.A. Artificial intelligence-based traffic flow prediction: a comprehensive review. J. Electr. Syst. Inf. Technol. 2023, 10, 1–42. [CrossRef]

- Schoenberg, S.; Dressler, F. Reducing Waiting Times at Charging Stations With Adaptive Electric Vehicle Route Planning. IEEE Trans. Intell. Veh. 2022, 8, 95–107. [CrossRef]

- Sebai, M.; Rejeb, L.; Denden, M.A.; Amor, Y.; Baati, L.; Ben Said, L. Optimal Electric Vehicles Route Planning with Traffic Flow Prediction and Real-Time Traffic Incidents. Int. J. Electr. Comput. Eng. Res. 2022, 2, 1–12. [CrossRef]

- Sheng, P.; He, Y.; Guo, X. The impact of urbanization on energy consumption and efficiency. Energy Environ. 2017, 28, 673–686. [CrossRef]

- Sirisha, U.M.; Belavagi, M.C.; Attigeri, G. Profit Prediction Using ARIMA, SARIMA and LSTM Models in Time Series Forecasting: A Comparison. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 124715–124727. [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, A., Singh, M., & Nandi, S. (2024). Support Vector Regression Based Traffic Prediction Machine Learning Model. In 2024 8th International Conference on Computational System and Information Technology for Sustainable Solutions (CSITSS) (pp. 1–6). IEEE.

- Sun, B.; Sun, T.; Jiao, P.; Tang, J. Spatio-Temporal Segmented Traffic Flow Prediction with ANPRS Data Based on Improved XGBoost. J. Adv. Transp. 2021, 2021, 1–24. [CrossRef]

- Szczepanski, R.; Tarczewski, T.; Erwinski, K. Energy Efficient Local Path Planning Algorithm Based on Predictive Artificial Potential Field. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 39729–39742. [CrossRef]

- Tiwari, A. K., Pandey, R. K., Singh, S., Tiwari, G., Kumar, A., & Mishra, P. (2023, November). Artificial intelligence-based smart traffic control system. In International Conference on Innovations in Data Analytics (pp. 249–258). Springer.

- Wang, Z.; Wang, S. Real-Time Dynamic Route Optimization Based on Predictive Control Principle. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 55062–55072. [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Li, S.; Zhang, Q.; Sun-Woo, K.; Yan, L. Route Planning and Tracking Control of an Intelligent Automatic Unmanned Transportation System Based on Dynamic Nonlinear Model Predictive Control. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2022, 23, 16576–16589. [CrossRef]

- Xia, D.; Zheng, L.; Tang, Y.; Cai, X.; Chen, L.; Sun, D. Dynamic traffic prediction for urban road network with the interpretable model. Phys. A: Stat. Mech. its Appl. 2022, 605. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S., & James, J. Q. (2021). Electric vehicle dynamic wireless charging system: Optimal placement and vehicle-to-grid scheduling. IEEE Internet of Things Journal, 9(8), 6047–6057.

- Zhang, Y.; Cao, W.; Zhao, H.; Gao, S. Route planning algorithm based on dynamic programming for electric vehicles delivering electric power to a region isolated from power grid. Artif. Life Robot. 2023, 28, 583–590. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, N.; Zhang, F.; Yang, Y.; Coskun, S.; Lin, X.; Hu, X. Dynamic Traffic Prediction-Based Energy Management of Connected Plug-In Hybrid Electric Vehicles with Long Short-Term State of Charge Planning. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2023, 72, 5833–5846. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y., Mo, L., & Liu, J. (2023, August). Path planning based on traffic flow prediction for vehicle scheduling. In *2023 IEEE/CIC International Conference on Communications in China (ICCC)* (pp. 1–5). IEEE.

- Irfan, M.S.; Dasgupta, S.; Rahman, M. Toward Transportation Digital Twin Systems for Traffic Safety and Mobility: A Review. IEEE Internet Things J. 2024, 11, 24581–24603. [CrossRef]