1. Introduction

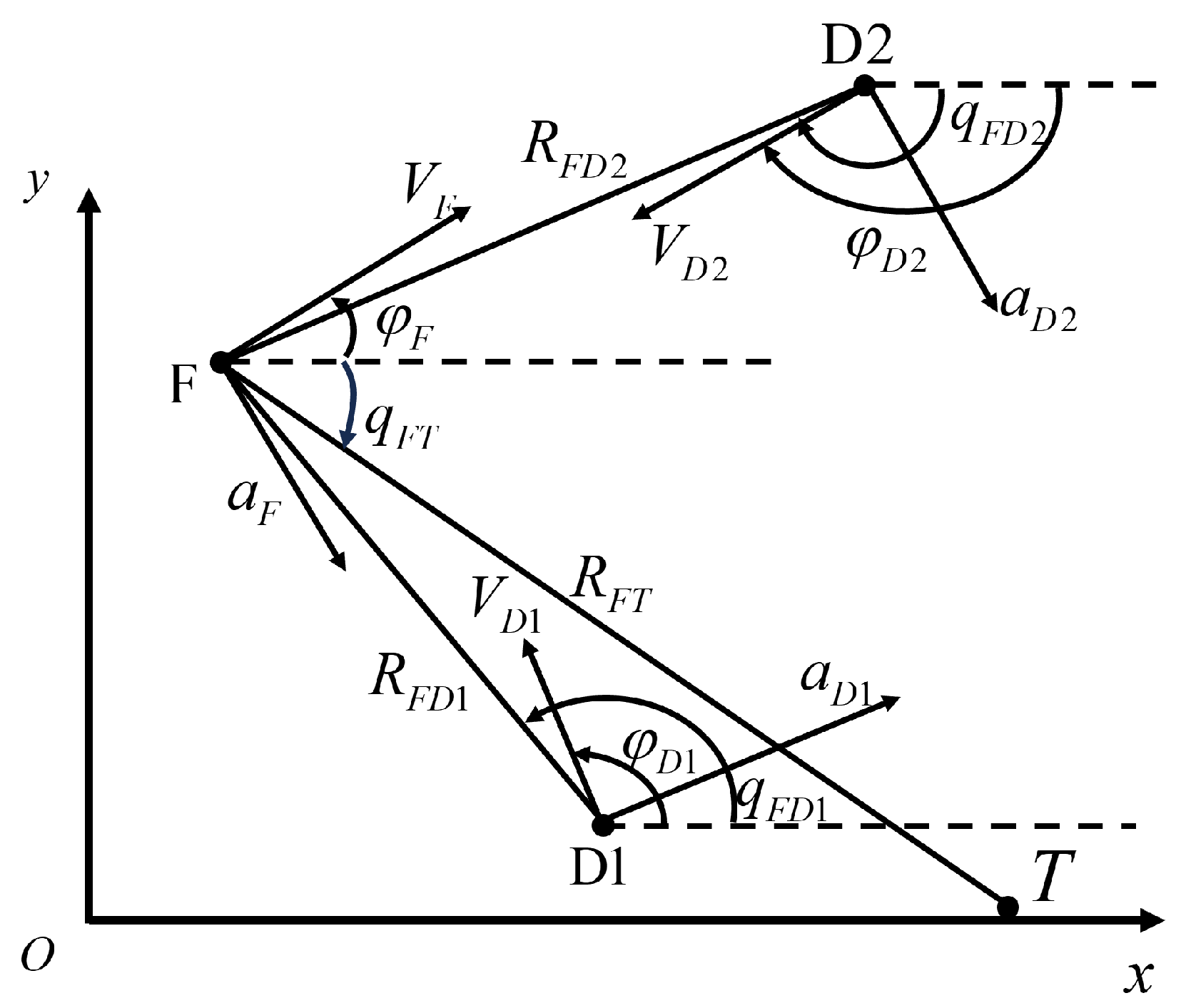

The precise strike capabilities of hypersonic missiles significantly affect modern warfare. In practice, the flight trajectory of the hypersonic missile can be divided into three phases: the boost phase, midcourse phase, and terminal phase. The terminal phase is crucial, as it directly determines the success of the mission and influences the missile’s final flight path and strike accuracy. Recently, global military powers have been researching interception technologies for hypersonic missiles and missile defense systems, intensively [

1,

2,

3,

4]. The terminal phase dive, characterized by low altitude limited acceleration, and high detectability, has become a critical interception zone for defense systems [

5,

6]. Enhancing missile maneuverability during the terminal phase to improve penetration and achieve high-precision strikes has become a key area of missile guidance research [

7,

8,

9].

Currently, missile maneuver penetration techniques can be classified into two main categories: programmatic maneuver penetration and game-theoretic maneuver penetration [

10]. Programmatic maneuver penetration involves determining the timing and program of terminal maneuvers before the missile is launched, without accounting for potential interference from enemy interception systems. Consequently, when faced with high-precision interception systems, successful penetration becomes challenging. As a result, autonomous maneuvering has become a primary focus in the development of penetration guidance laws [

11,

12,

13,

14].

In contrast, game-theoretic maneuver penetration refers to a scenario where, upon detecting an incoming interceptor, the attack missile acquires the interceptor’s flight parameters and, using its onboard computation module, calculates real-time maneuver commands to perform penetration maneuvers. This strategy allows the missile to select the optimal approach to penetration based on the interception method, thereby significantly improving the likelihood of successful penetration. Shinar applied a two-dimensional linearized kinematic method to analyze the penetration problem of interceptor missiles under proportional guidance and identify the key factors influencing the miss distance. A simple search algorithm was also used to determine the optimal timing and direction of the maneuver [

15]. Ref.16 addresses the issue of strategy implementation for attacking missiles under limited observation by introducing a network adaptation feedback strategy and inverse game theory. It also selects strategies that meet consistency standards through optimization methods [

16]. Ref.17 introduced a Linear-Quadratic (LQ) differential game approach to model the missile offense-defense interaction [

17]. By combining the Hamilton-Jacobi adjoint vector with the conjugate method, the authors proposed a novel conjugate decision-making strategy and provided an analytical solution for the optimal parameters. Ref.18 presents an optimal guidance solution based on the linear quadratic differential game method and the numerical solution of the Riccati differential equation. It studies the interception problem of ballistic missiles with active defense capabilities and proposes an optimal guidance solution based on differential game strategies [

18]. Ref.19 designs a cooperative guidance law by establishing a zero-sum two-player differential game framework, allowing the attack missile to intercept the target while evading the defender, and satisfying the constraint on the relative interception angle [

19]. Ref.20 derived a penetration guidance law with a controllable miss distance, using optimal control theory to fit guidance parameters via a Back Propagation (BP) neural network and achieve optimal energy expenditure during the guidance process [

20]. Compared with traditional pre-programmed maneuver strategies, maneuver penetration based on differential games possesses intelligent characteristics and provides real-time decision-making capabilities. However, it also presents challenges, including high computational complexity, difficulties in mathematical modeling, and the need for precise problem formulation.

With the integration of artificial intelligence technologies into differential pursuit-escape problems, novel approaches have emerged for missile terminal penetration. For the three-body pursuit-escape problem in a two-dimensional plane, Ref.21 utilized the Twin Delayed Deep Deterministic policy gradient (TD3) algorithm to train the attacker’s agent, enabling it to learn a guiding strategy in response to the defender’s actions, thus achieving successful target capture [

21]. In the missile penetration scenario during an missile’s dive phase, Ref.22 employed an enhanced Prioritized Experience Replay-Deep Deterministic Policy Gradient (PER-DDPG) algorithm, which emphasized learning from successful penetration experiences. This approach notably accelerated the convergence of the training process [

22]. Ref.23 introduced a maneuvering game-based guidance law based on Deep Reinforcement Learning (DRL), which, in comparison to traditional programmatic maneuvering penetration, significantly enhanced the stability of the penetration [

23]. Ref.24 proposes a hypersonic missile penetration strategy optimized using Reinforcement Meta Learning (RML), which increases the difficulty of interception through multiple random transitions [

24]. Ref.25 treated the penetration process as a linear system and derived an analytical solution for the miss distance [

25]. However, the penetration strategy obtained in this manner requires complete knowledge of the interceptor’s guidance parameters, which is highly challenging to obtain in practical confrontation scenarios.

Most existing penetration guidance laws mainly focus on the confrontation between the attacker and defender, while neglecting the impact of penetration on strike accuracy. While penetration is critical, excessive maneuvering may cause the missile to miss the target despite successful evasion. Therefore, an integrated penetration guidance strategy is needed: one that accounts for both penetration and strike accuracy, while staying within the missile’s acceleration and performance limits, and minimizing energy consumption during the penetration process. Ref. 26 innovatively designs a reward function incorporating an energy consumption factor to balance miss distance and energy efficiency. Additionally, a regression neural network is utilized to enhance the generalization capability of the penetration strategy and achieve evasion of interpret missile and precise strikes on the target [

26]. Regarding the issue of missile penetration time, Ref.27 proposed an integrated guidance and strike penetration law based on optimal control, which ensures that the Line-of-sight (LOS) angular velocity between the attack missile and the defending interceptor reaches a specified value within a given time, thereby achieving penetration [

27].

In summary, existing penetration strategies predominantly focus on the one-on-one adversarial scenario between the attacking missile and interceptor missiles, and heavily rely on the engagement context between them, often neglecting the subsequent guidance tasks. To address these issues, this paper explores the integration of optimal control and DRL, designing a guidance law that combines intelligent penetration and steering. The main contributions of this paper are as follows:

To address the attacking-multi interceptor-target adversarial scenario, a Markov Decision Process (MDP) model is constructed. This model takes the observable states of both sides as input and outputs the penetration acceleration commands for the attacking missile, enabling intelligent maneuvering penetration decisions in a continuous state space.

To tackle the coupling problem between penetration maneuvers and guidance tasks, a multi-objective reward function is designed. It maximizes the penetration success rate while constraining the maneuvering range through an energy consumption penalty term, ensuring terminal strike accuracy.

To overcome the training efficiency bottleneck caused by sparse rewards, a fusion of Generative Adversarial Imitation Learning (GAIL) and Proximal Policy Optimization (PPO) algorithms is proposed. Expert trajectory priors are utilized to guide exploration, significantly improving policy sampling efficiency and asymptotic performance.

The organization of this study is as follows:

Section 2 establishes the mathematical model of the adversarial scenario and derives the optimal BANG-BANG penetration strategy.

Section 3 constructs the MDP model for the penetration process and designs a GAIL-PPO-based hybrid training framework.

Section 4 presents the training and testing experimental results. Finally,

Section 5 summarizes the research conclusions.

3. GAIL-PPO Penetration Strategy

In Section II, we derived the BANG-BANG penetration strategy that maximizes the miss distance. However, this derivation was conducted under a one-on-one engagement scenario. When facing multiple interceptor missiles simultaneously, penetration can only be achieved by switching targets, which does not guarantee a high success rate. Additionally, energy consumption during the penetration process was not considered. To address these issues, this section proposes an intelligent penetration strategy based on GAIL-PPO.

3.1. Construction of the MDP Model for the Penetration Process

In order to use DRL to solve the problem of generating penetration strategies, the penetration problem must be transformed into a DRL framework. First, a MDP model for missile penetration is constructed to define how the agent interacts with the environment to make decisions. The model primarily consists of elements such as S, A, P, R, and , where S represents the finite state space, with any state ; A represents the finite action space, with any action ; P is the state transition probability; R is the reward function; and is the discount factor and , used to calculate the accumulated reward. In the context of this missile penetration problem, the state transition probability is defined, and the state space, action space, and reward function are outlined as follows:

3.1.1. Definition of the State Space

The penetration process must consider subsequent guidance tasks, requiring the state space design to account for the states of the attack missile, intercept missile, and target. The penetration direction of the attack missile has a significant impact on its flight altitude after penetration. Different LOS angle require different flight altitudes after penetration. Smaller LOS angle prefers a lower flight altitude after penetration, while larger LOS angle prefer a higher flight altitude. Hence, we incorporate LOS-related terms into the state space to optimize the penetration direction. In order to enhance learning stability, accelerate convergence, and alleviate numerical issues, we have normalized the state space. The state space is therefore constructed as follows:

where

,

,

,

,

,

,

represents the distance between the attack missile and the intercept missile at the beginning of the penetration, and

represents the initial distance between the attack missile and the target.

3.1.2. Definition of the Action Space

In selecting the action space, the missile’s penetration acceleration is often directly used as the output. However, due to the small sampling step size typically used during training, directly outputting the acceleration can lead to significant fluctuations in the acceleration curve during penetration, which are difficult to realize in real-world scenarios. To mitigate this issue, we select the derivative of the missile’s acceleration as the action space output:

3.1.3. Definition of the Reward Function

The reward function defines the immediate feedback provided by the environment after the agent takes an action in a particular state. It influences the agent’s behavior and guides it toward achieving its goal. Therefore, a well-designed reward function directly impacts the generation of penetration commands. Unlike previous approaches that use the miss distance between the attack missile and the intercept missile as the reward function, this paper chooses to use the acceleration of the intercept missile as the reward function. When the interceptor’s acceleration reaches a saturation point, it indicates that the interception task has surpassed the interceptor’s operational capacity. Consequently, the goal of the attack missile’s penetration is to drive the interceptor’s acceleration toward saturation as much as possible, thus bypassing the interceptor and achieving successful penetration. At the same time, the attack missile should aim to minimize its maneuvering range. Based on this objective, we design the instantaneous reward function as follows:

where

and

represent the accelerations sizes of two intercept missiles, respectively.

The terminal reward function is designed based on whether the task is successful:

where

represents the energy consumption term,

represents the kill radius of the intercept missile,

represents the kill radius of the attack missile. When the attack missile is intercepted or the mission fails, a large penalty is applied. Conversely, when the attack missile successfully hits the target, a large reward is given.

Considering both the penetration effect and task completion status, the function is designed as follows:

3.2. GAIL-PPO Algorithm

3.2.1. GAIL Training Network Construction

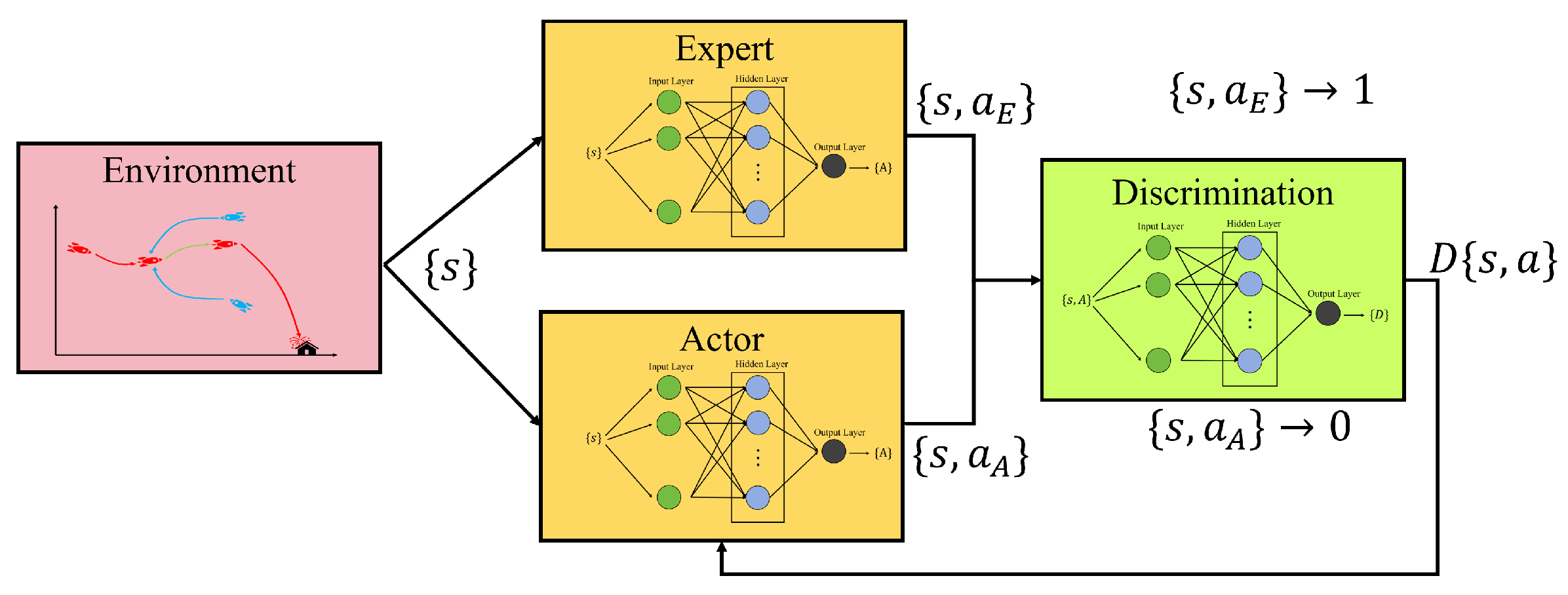

Generative Adversarial Imitation Learning (GAIL) learns a policy through a generative adversarial approach, aiming to make the generated behavior as similar as possible to the expert behavior. Its main structure is shown in

Figure 3:

Figure 3.

GAIL structure.

Figure 3.

GAIL structure.

GAIL primarily consists of an Actor Network and a Discriminator Network. When the environment provides a state, both the Actor and the Expert generate corresponding actions. These state-action pairs are fed into the Discriminator, which outputs a real number between (0, 1). The Discriminator’s task is to push the Expert’s output closer to 0 and the Actor’s output closer to 1, while the Actor’s objective is to deceive the Discriminator as much as possible. Consequently, the loss functions for both the Actor and the Discriminator are formulated as follows:

where

and

denote the state-action pairs generated by the Expert and the Actor, respectively, and

represents the Discriminator’s probability prediction that the state-action pair belongs to the Expert.

The Actor and the Discriminator form an adversarial process. Ultimately, the data distribution generated by the imitator policy will approach the real expert data distribution, achieving the goal of imitation learning.

3.2.2. PPO Training Network Construction

Proximal Policy Optimization (PPO) is a reinforcement learning algorithm designed for efficient and stable policy optimization [

28]. Its core objective is to train agents that maximize cumulative rewards by updating policy parameters via gradient ascent. PPO-CLIP achieves this through two key innovations:

PPO-CLIP uses a probability ratio to measure policy changes:

where

and

denote the current policy and the old policy, respectively.

A clipped objective function controls update magnitude:

where

is the advantage function and

(typically 0.1-0.2) clips excessive policy changes. This prevents destructive updates while allowing monotonic improvement.

To reduce variance in advantage estimation, we use Generalized Advantage Estimation (GAE):

with temporal difference error:

where

is the discount factor and

balances bias-variance tradeoff.

The critic network

is optimized by minimizing mean squared error:

This provides stable value estimates for advantage calculation and policy updates.

In the GAIL-PPO algorithm, both networks share a single Actor Network. Taking into account the state space and action space of the model, the parameter settings for the three networks are summarized in

Table 2 as follows:

where the BatchNorm layer reduces internal covariate shift by normalizing the input distribution. It accelerates training, enhances convergence stability, reduces sensitivity to weight initialization and learning rates, and alleviates the issues of gradient vanishing and exploding.

3.2.3. Training Procedure of the GAIL-PPO Algorithm

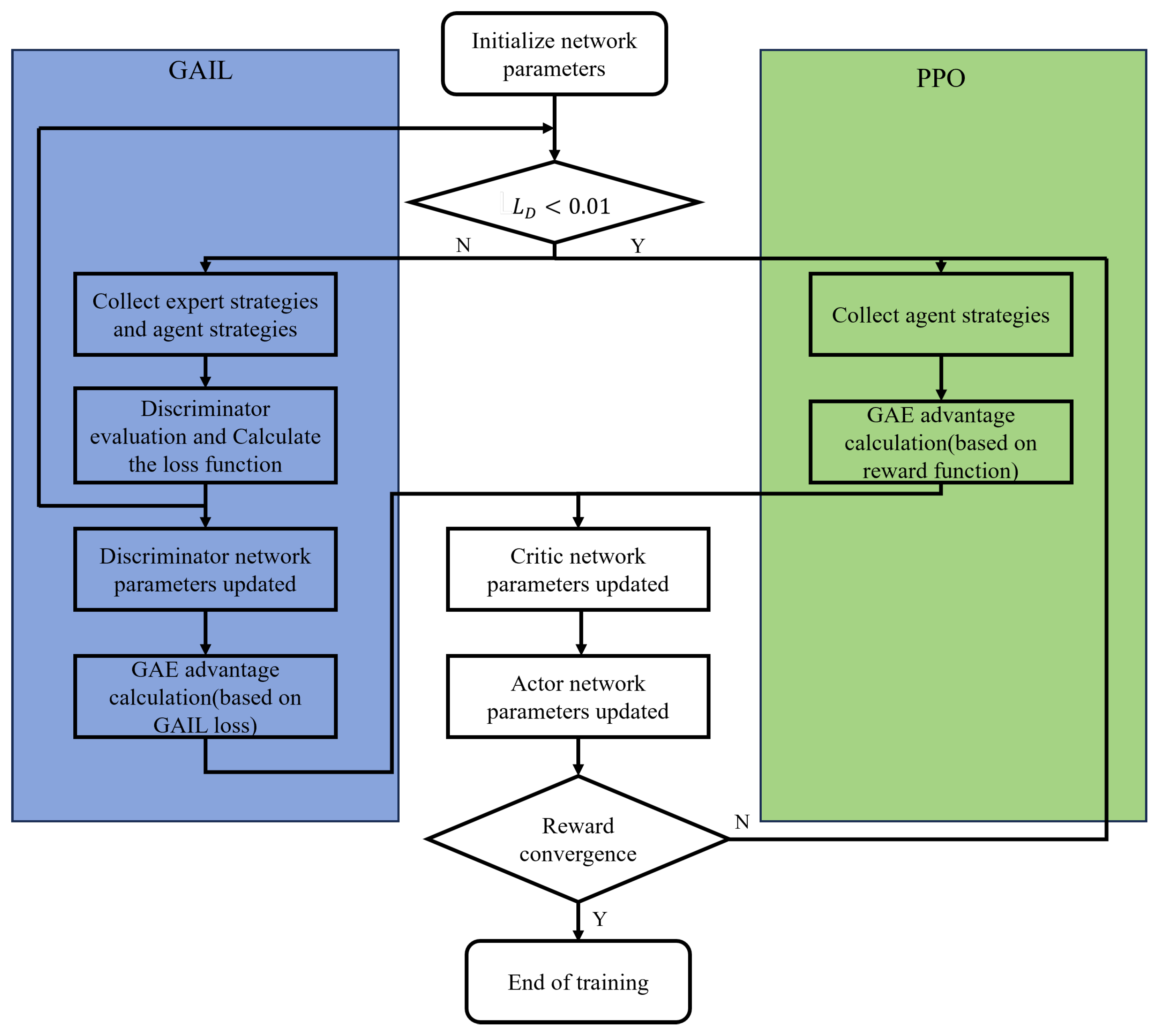

The training process of the GAIL-PPO algorithm is illustrated in

Figure 4:

Figure 4.

Training Procedure

Figure 4.

Training Procedure

First, the parameters of the Discriminator, Actor, and Critic networks are initialized. Subsequently, the training enters the GAIL pre-training phase. In this phase, when the Discriminator loss is , expert trajectories and agent trajectories are collected first. The Discriminator parameters are then updated by calculating the cross-entropy loss. Following this, the GAIL reward is computed based on the Discriminator’s output, and the advantage function is estimated using GAE. The Critic parameters are updated with the Mean Squared Error (MSE) loss, while the Actor parameters are updated using the PPO clipped objective function. When the Discriminator loss reaches , the training transitions to the PPO fine-tuning phase. At this stage, only agent trajectories are collected, and the environment’s true reward replaces the GAIL reward. The GAE advantage function is recomputed, and the Actor-Critic network is updated again using the same PPO clipped objective function. The training terminates when the average reward remains below a threshold for consecutive iterations.

The GAIL-PPO algorithm is shown in

Table 3:

This training process leverages GAIL pre-training to rapidly learn expert behavior patterns and then employs PPO with true rewards to optimize the performance upper bound, combining the advantages of imitation learning and reinforcement learning.

4. Training Results and Performance Validation

In this section, the training method proposed in section 3 is first applied, using the BANG-BANG penetration strategy introduced in

Section 2 as the expert experience to train the GAIL-PPO algorithm. Subsequently, the trained strategy is compared with traditional methods, and the effects of different parameters on penetration performance are evaluated. The engagement scenarios are consistent with those defined in Section II, and the parameter settings remain the same as in Section II unless otherwise specified.

4.1. Training Results

Before starting the training, the necessary parameters are set:

Table 4.

Parameters for Training

Table 4.

Parameters for Training

| Parameters |

Value |

| Discount Factor |

0.99 |

| Clip Factor |

0.1 |

| Entropy Loss Weight |

0.05 |

| GAE Factor |

0.95 |

| Mini Batch Size |

128 |

| Experience Horizon |

1024 |

| Sample Time |

0.01 |

| Interceptor 1 Initial Position(m) |

([45000,50000], -10000) |

| Interceptor 2 Initial Position(m) |

([45000,50000], 10000) |

| Target Position(m) |

([50000,55000], -10000) |

| LOS angle(rad) |

[,] |

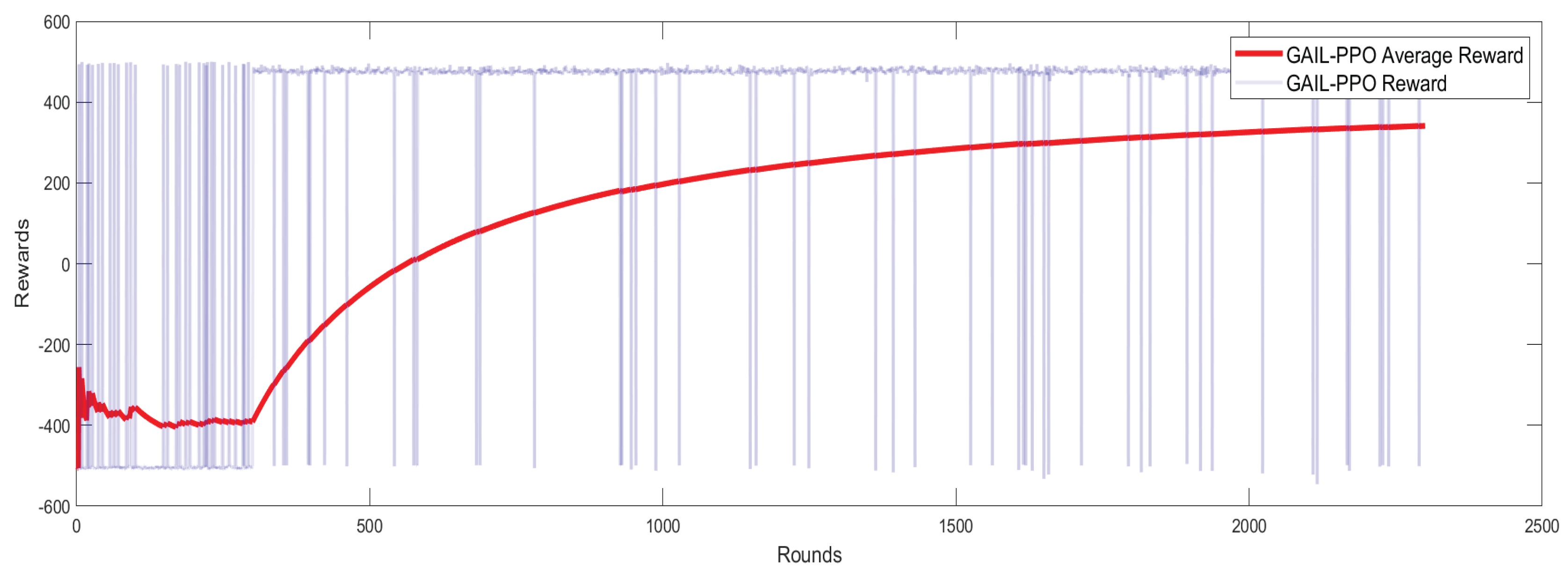

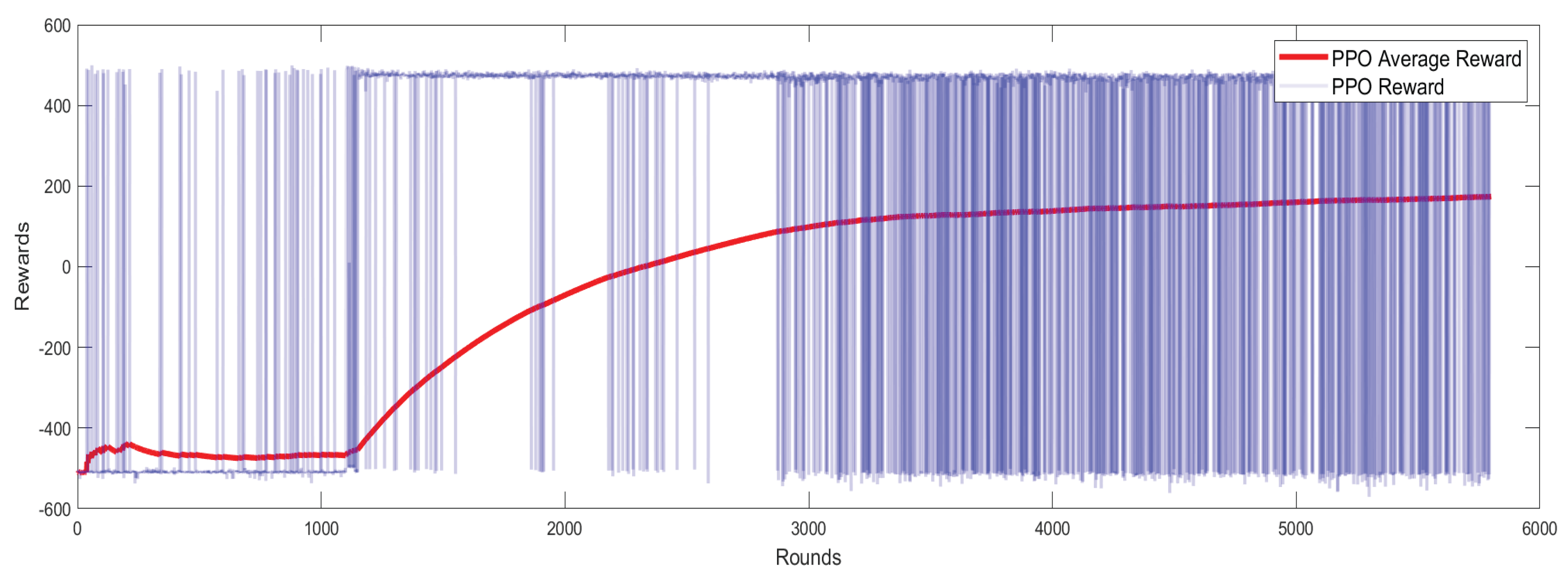

As shown in

Figure 5 and

Figure 6, the blue curve represents the per-step reward, while the red curve represents the moving average reward. The GAIL-PPO algorithm, leveraging expert trajectories from imitation learning, achieves significant improvements in training efficiency, final performance, and policy stability.In terms of convergence speed, the GAIL-PPO algorithm achieves an average reward of 300 at 1,700 training steps, while pure PPO requires 3,400 steps to reach the same reward level under identical hardware conditions. This represents a 50% reduction in training steps. This suggests that GAIL provides effective exploration priors for PPO by imitating expert behavior, thereby reducing ineffective attempts during random exploration. Regarding final performance, in the later stages of training, the average reward of GAIL-PPO stabilizes at 350, which is 94.4% higher than the 180 achieved by pure PPO. Additionally, the fluctuation range of the per-step reward for GAIL-PPO is significantly narrower, demonstrating more consistent action selection under similar states and reducing errors caused by random exploration. These characteristics directly correlate with task performance: higher average rewards with reduced fluctuations imply that GAIL-PPO can more stably reproduce high-reward successful penetration behaviors, resulting in a significantly higher penetration success rate compared to the pure PPO algorithm.

Figure 5.

GAIL-PPO Training Reward

Figure 5.

GAIL-PPO Training Reward

Figure 6.

PPO Training Reward

Figure 6.

PPO Training Reward

The above results fully validate the effectiveness of the GAIL-PPO framework. Imitation learning provides RL with expert priors, addressing the core challenges in missile penetration tasks—sparse rewards (only successful penetration yields high rewards) and high exploration costs (incorrect actions incur heavy penalties). This significantly improves training efficiency, final performance, and policy stability. The imitation-reinforcement hybrid paradigm offers an optimized solution for training intelligent agents in complex tasks such as missile penetration.

4.2. Performance Validation

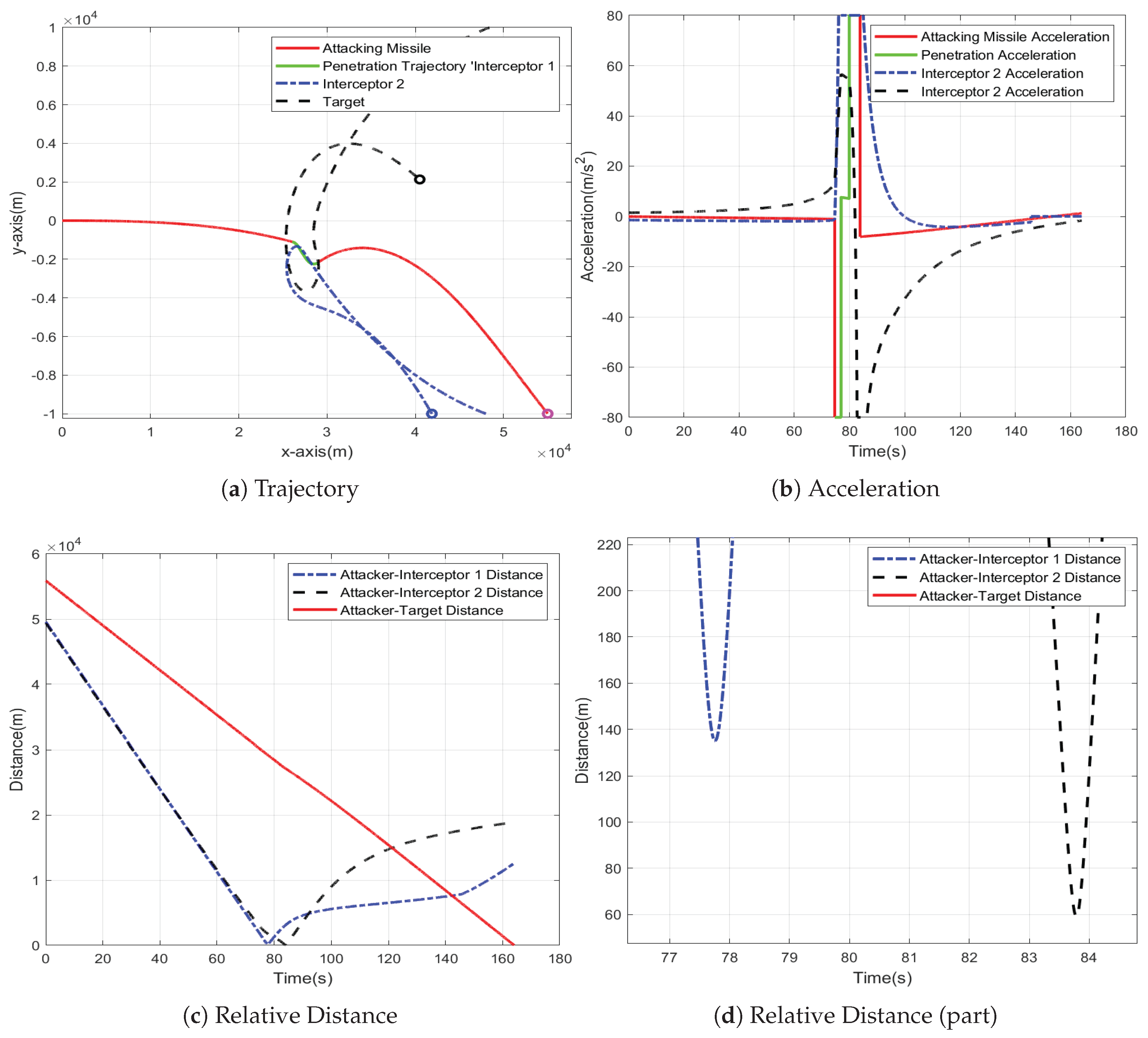

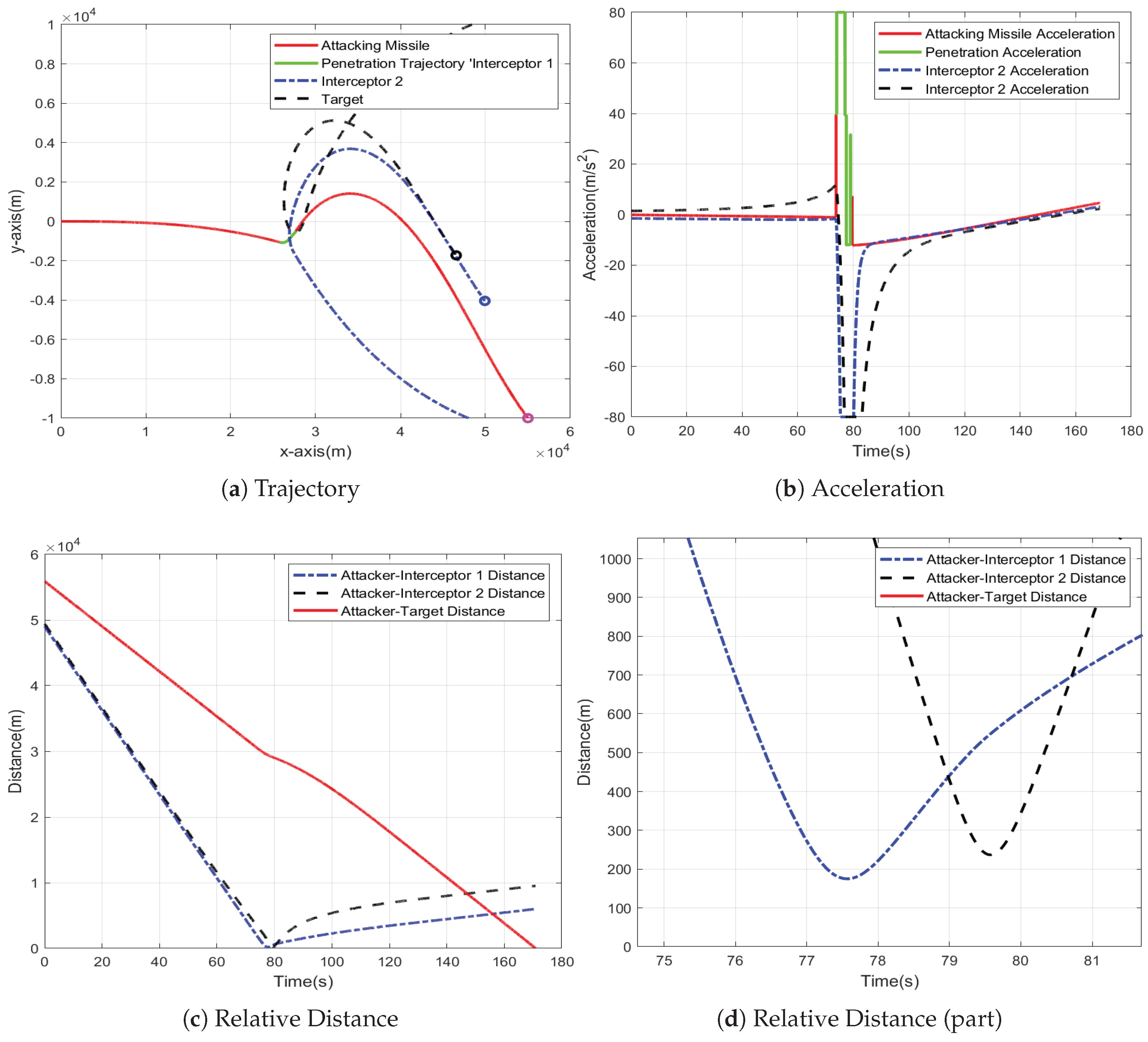

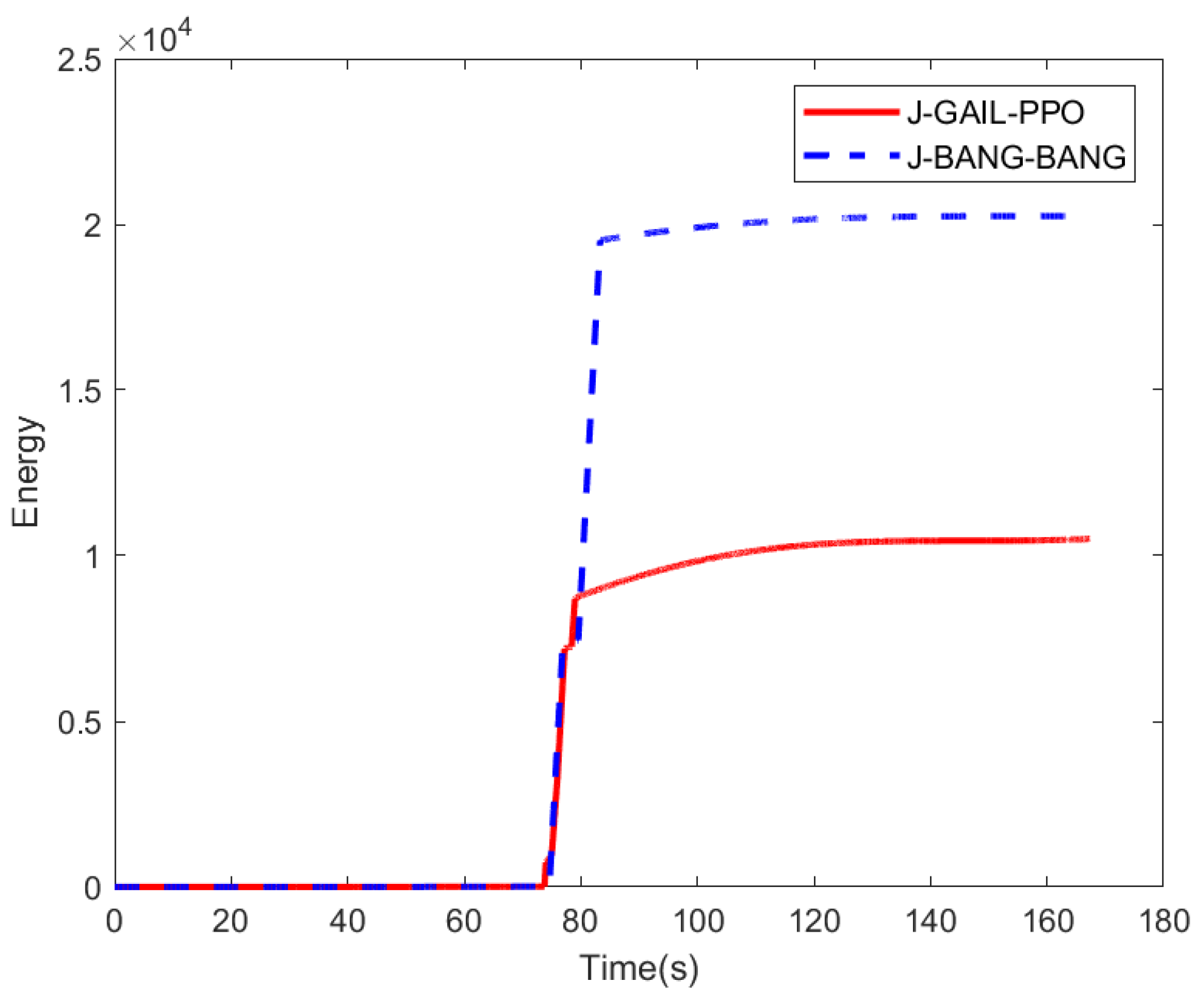

To validate the performance of the GAIL-PPO penetration strategy, the same simulation parameters as those used for the BANG-BANG strategy are adopted. The results are shown in

Figure 7, while

Figure 8 presents the energy consumption calculated based on Equation (

29) over the entire mission for both strategies.

Compared to the BANG-BANG strategy, which requires stepwise maneuvers against each interceptor, the GAIL-PPO strategy achieves synchronized avoidance of multiple interceptor missiles through a single continuous maneuver. This eliminates the structural acceleration risk caused by sustained saturated acceleration in the BANG-BANG strategy. Additionally, the GAIL-PPO strategy significantly reduces the maneuvering range. This not only results in a 51% reduction in energy consumption compared to the BANG-BANG strategy but also creates more favorable conditions for guidance tasks following penetration.

Figure 7.

Simulation Results of Performance Validation

Figure 7.

Simulation Results of Performance Validation

Figure 8.

Energy Consumption

Figure 8.

Energy Consumption

4.3. Monte Carlo Simulation

The previous section demonstrated, through a single-case simulation, the advantages of the GAIL-PPO strategy in terms of trajectory accuracy, maneuver efficiency, and energy consumption. However, it did not account for the inevitable uncertainties present in real penetration tasks. To systematically evaluate the robustness and statistical significance of the GAIL-PPO strategy, this section conducts 1,000 Monte Carlo simulations under both training parameters and non-training parameters. Key metrics, including penetration success rate, average energy consumption, mission time, and minimum interception distance, are compared between the GAIL-PPO and BANG-BANG strategies to quantitatively validate the comprehensive performance advantages of GAIL-PPO.

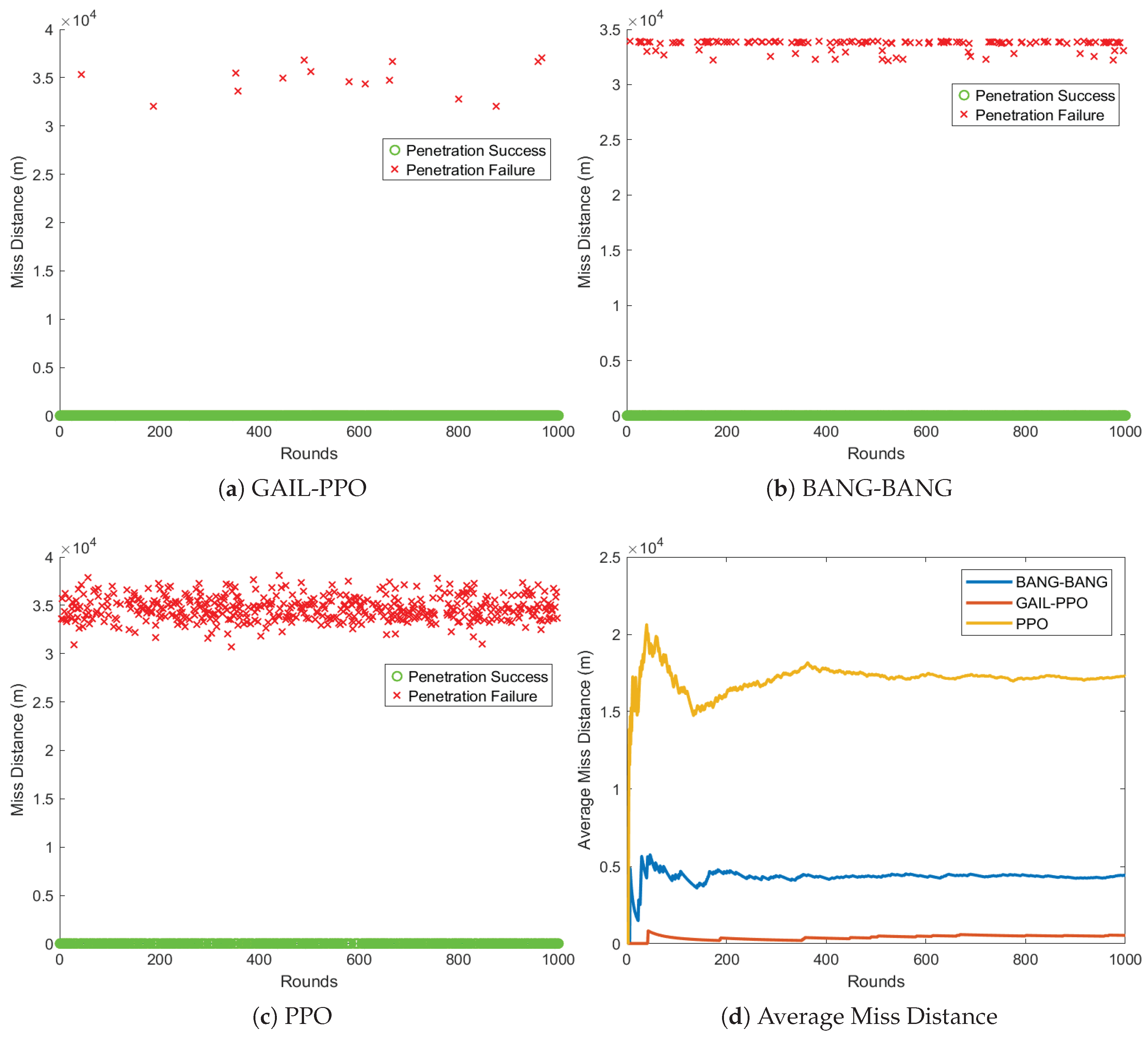

4.3.1. Testing in Training Parameters

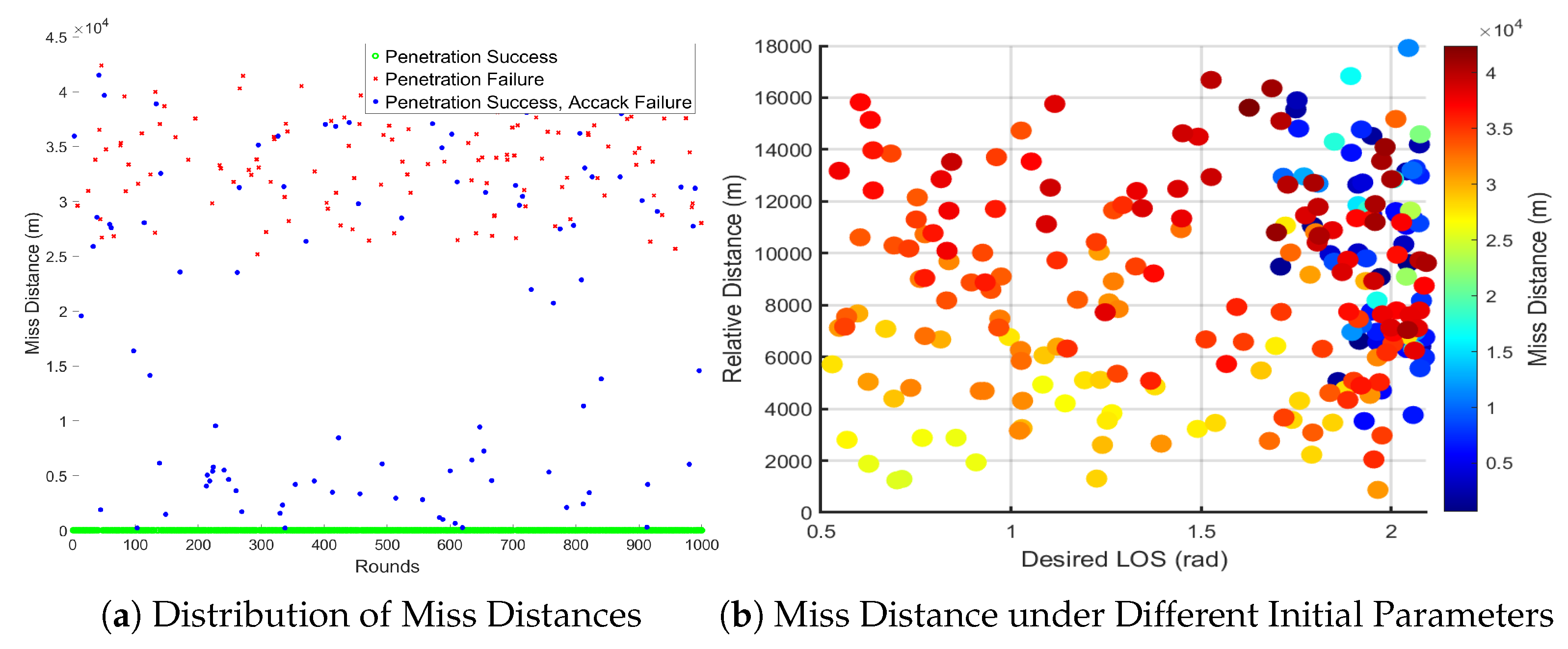

Figure 9 shows the results of 1,000 Monte Carlo simulations, demonstrating that the GAIL-PPO strategy achieves a successful penetration rate of 98.5%, significantly higher than the 86.9% for the BANG-BANG strategy and 50.2% for the PPO strategy. In terms of the average miss distance over 1,000 simulations, the GAIL-PPO strategy stabilizes at 540 m, which is much lower than the 4,419 m for the BANG-BANG strategy and 17,273 m for the PPO strategy. These results indicate that the GAIL-PPO strategy exhibits significant advantages in three key metrics: penetration success rate, miss distance accuracy, and policy stability.

Figure 9.

Monte Carlo simulation results under the training scenario

Figure 9.

Monte Carlo simulation results under the training scenario

4.3.2. Testing Under Non-Training Parameters

To evaluate the robustness and generalization ability of the proposed penetration strategy, it is applied to scenarios beyond the training data. The corresponding simulation parameters are summarized in

Table 5. Untrained scenarios preserve the same dynamics but vary key parameters (initial relative position, LOS angle) to probe generalization. To enhance the penetration challenge, a disturbance error is introduced into the launch angle of the attacking missile. Furthermore, the target is no longer stationary but moves with a constant linear velocity along the horizontal plane in the direction of the attacking missile, simulating an evasive maneuver. The acceleration command for the intercept missile is governed by an interception guidance law specifically designed for high-speed maneuvering targets, as detailed in Reference [

29].

Figure 10 displays the results of 1000 Monte Carlo simulation runs under the untrained scenario. Figure (a) presents the distribution of miss distances from the simulation results. It shows that the GAIL-PPO penetration strategy proposed in this paper performs well even in more complex adversarial scenarios. Despite facing more sophisticated interceptor missiles and certain disturbances, the penetration success rate reaches 86.3%. Figure (b) illustrates the relationship between miss distance, desired LOS, and the initial relative position of the target and interceptor. As shown in the figure, regions with a larger desired LOS angle are populated with numerous cases of smaller miss distances, which aligns with the distribution of cases where penetration is successful but the mission fails, as observed in Figure (a). This indicates that when dealing with large desired LOS angle, even if the attacking missile successfully penetrates, the subsequent strike mission becomes highly challenging due to insufficient altitude after penetration. Nevertheless, the attack success rate still achieves 77%.These simulation results validate that the comprehensive penetration guidance law, designed based on deep reinforcement learning in this paper, maintains excellent performance across various complex environments. The proposed method demonstrates strong robustness and good generalization capabilities, even when encountering adversarial scenarios with unknown characteristics, achieving a high mission success rate.

Figure 10.

Monte Carlo simulation results under the Non-Training Scenarios

Figure 10.

Monte Carlo simulation results under the Non-Training Scenarios