1. Introduction

Monogamous prairie voles,

Microtus ochrogaster, are a non-traditional animal model used to study the impacts of social monogamy and pair bonding in translational research [

1,

2]. In animals, a pair bond is a lifelong bond with biological correlates that forms between two mating partners [

1]. In humans, a pair bond is a lifelong bond with biological correlates that is created during long term romantic or sexual partnerships, long term friendships, and selective caregiver attachments in humans [

3,

4,

5]. The similarities between animal pair bonds and human pair bonds, along with the importance of human relationships to our social wellbeing, combine to make prairie voles an excellent model species for studying human behavior [

6]. However, prairie voles are vastly understudied due to a lack of commercial availability and transgenic tools.

Microglia are the resident immune cells of the brain, existing as the only macrophages in the brain parenchyma [

7]. Microglia in the central nervous system support neurons and are important for cleanup of cellular debris, assistance with inflammatory responses, and pruning of synapses [

8,

9]. While microglia have been well studied in mice, rats, and humans, little is known about microglia in prairie voles [

10].

Studies from the past three years have begun to investigate vole microglia but have focused on the effects of cohousing vs. isolation housing, not on the effects of pair bonding [

11,

12]. Isolated adult voles show differences in microgliosis when compared to cohoused voles, corresponding also to differences in depressive symptoms, neuronal activation and neurochemical expression [

11]. These results were replicated in adolescent voles using a model of post-weaning isolation housing to demonstrate brain region specific changes in microglia density, an index of microgliosis [

12]. However, no studies to date have investigated whether these results persist when comparing paired and unpaired voles.

Due to the lack of microglia research in prairie voles, findings from mouse, rat, and human postmortem research must be used to make predictions about prairie vole microglia histology [

13]. Two basic classifications of microglia are homeostatic microglia and reactive microglia. Homeostatic microglia (often called “ramified”) are characterized by small triangular somas and many long, arborized processes. They function by contributing to several homeostatic functions such as surveillance, neurogenesis, and synapse monitoring and pruning [

8,

14]. In contrast, reactive microglia are characterized by larger, rounder somas with fewer and shorter processes [

14]. Formerly referred to as “activated” microglia, reactive microglia are present during a brain’s inflammatory response and are localized in brain areas with high levels of inflammatory signaling. While the correlation between reduced branching and inflammation has long been assumed, a study by Madry et al. recently demonstrated a mechanistic link between reduced microglia branching and microglia cytokine release [

15].

At the intersection of microglia as an understudied cell type and prairie voles as a socially monogamous model species lies the potential role of microglia in disorders of social behavior. The neuroplasticity of vole brains during pair bonding marks the pair bond as a key developmental timepoint when changes to social behavior may occur [

6,

16]. Microglia are also hypothesized to play distinct functional roles in mediating social behaviors [

17,

18,

19,

20]. The present study commences at this intersection by comparing microglia in pair bonded prairie voles to microglia of unpaired prairie voles to elucidate microglia changes that occur in the presence of a biological pair bond.

The most common brain areas previously examined in voles are the nucleus accumbens (NAc) and the amygdala (AG) [

11,

12]. While these brain areas are important for processing social and stressful stimuli, the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) and the prefrontal cortex (PFC) are much more involved in social information processing, especially in humans [

21,

22]. The present study uses quantitative immunohistochemistry (IHC) to characterize microglia morphology in the ACC and PFC of

Microtus ochrogaster, and to elucidate the relationship between pair bonding status and microglia reactivity in prairie voles. We tested the hypothesis that there is a sexually dimorphic relationship between pair bonding status and microglia morphology. Our results supported our hypothesis and made methodological contributions to the literature, supporting that murine IHC protocols can be successfully implemented in

Microtus ochrogaster to histologically stain and quantify microglia morphology.

2. Results

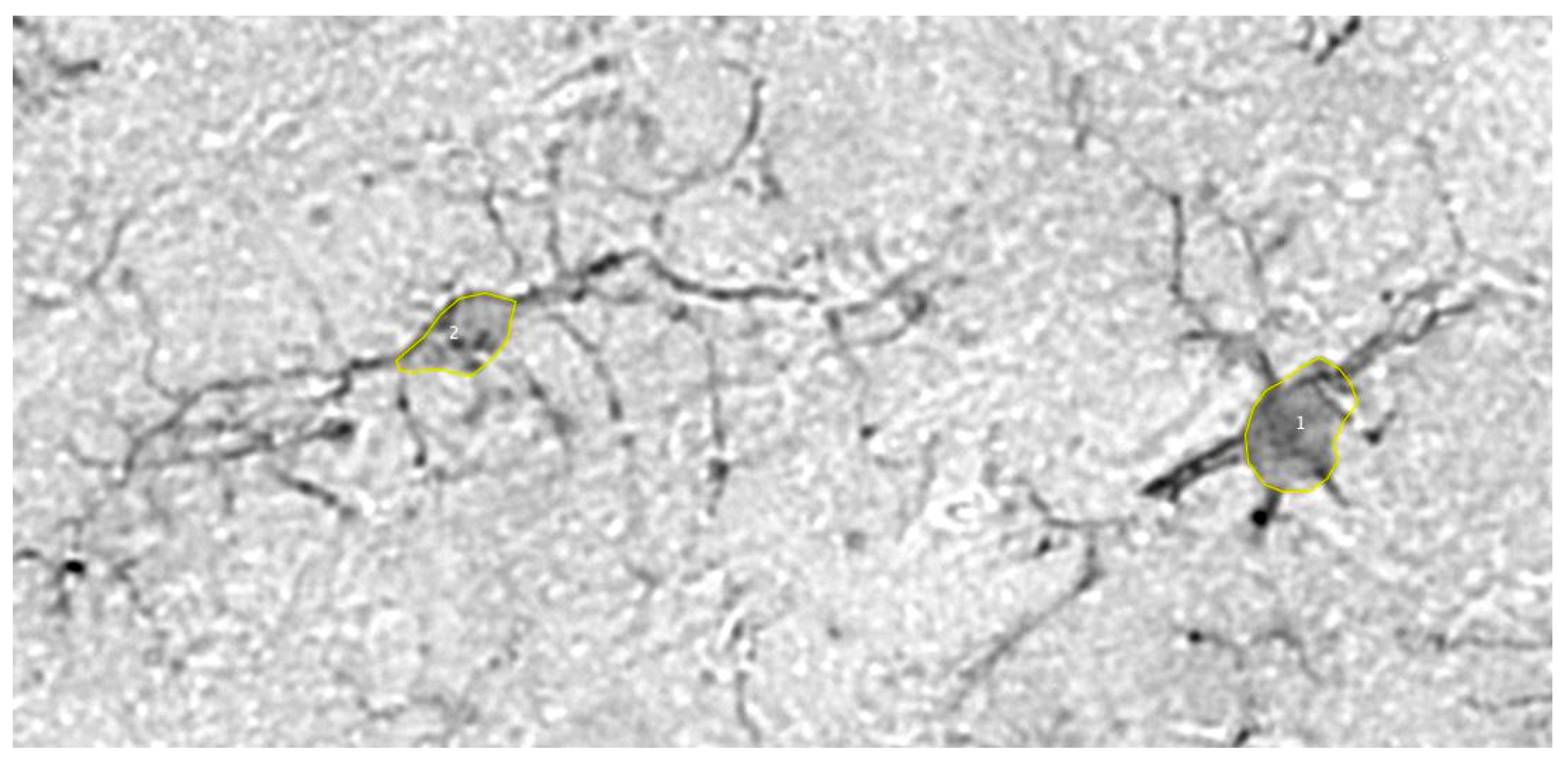

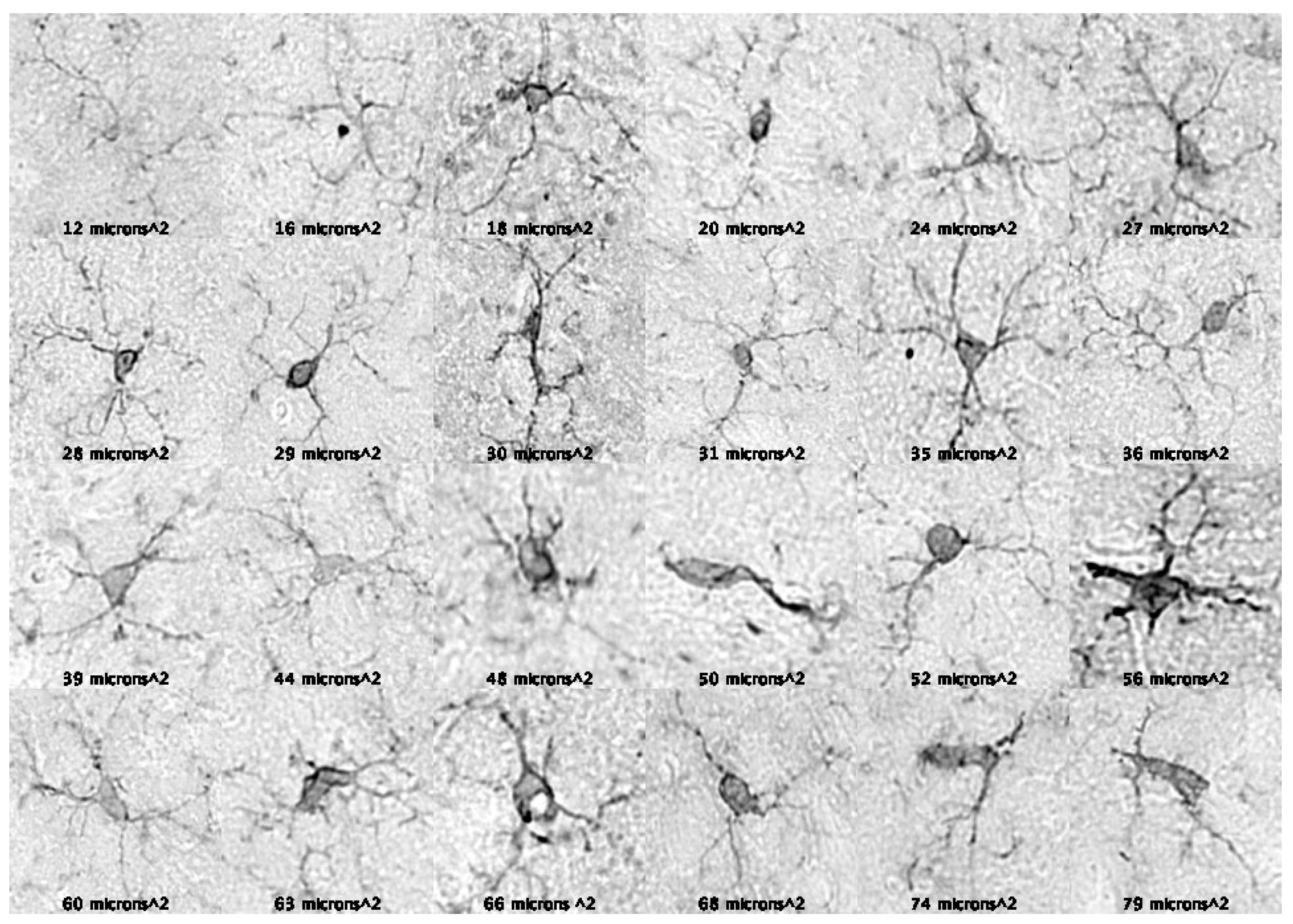

2.1. Characterizing Microglia in Prairie Voles

A total of 12,539 microglia were identified and their soma sizes measured. An area of 24.668 square millimeters (mm

2) in the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) and 13.756 mm

2 in the prefrontal cortex (PFC) were analyzed for a total combined area of 38.424 mm

2. Only somas which fell within the threshold of 10-80 square microns were counted and measured (See Materials and Methods for description of how threshold was determined). The existence of both homeostatic and reactive microglia in the vole tissue was confirmed (

Figure 1). Photomicrographs of microglia across the entire soma threshold support the notion that microglia with smaller somas contain longer and more numerous processes, while microglia with larger somas contain shorter and fewer processes (

Figure 2).

Across all subjects and brain regions, microglia were found at a density of 326.33 cells per mm2 (approximately 1 cell per 3000 square microns) and the mean soma area was 29.693 square microns. Densities across female and male voles were 319 cells per mm2 and 223 cells per mm2, densities across unpaired and paired voles were 313 cells per mm2 and 249 cells per mm2, and densities across ACC and PFC regions were 319 cells per mm2and 340 cells per mm2, respectively. Densities are reported for descriptive purposes, but testing for differences in cell density between groups was not performed.

2.2. Evaluating the Normality of Microglia Soma Size Distributions in Prairie Voles

Since the expected distribution of microglia soma size was unknown, a quartile-quartile (Q-Q) plot and histogram were created to visualize the distribution of each of the four main variables: Unpaired Male Somas (n=2), Unpaired Female Somas (n=2), Paired Male Somas (n=2), and Paired Female Somas (n=2). These distributions were created for each of the four groups in three different brain areas: anterior cingulate cortex (ACC), prefrontal cortex (PFC), and both cortices combined into one group. The Q-Q plots and histograms were used to determine whether the data were normally distributed (

Supplementary Figures S1-S6). All distributions displayed positive skewness. However, the distributions appeared to still be normally distributed, just shifted to the left, indicating that the lower half of the dataset may have been missing from the soma detection threshold. To quantify the significance of this skewed visualization, skewness and kurtosis were calculated and normality was quantified using chi-squared goodness of fit testing. These results are summarized in

Supplementary Tables S1-S4. While the chi-squared normality testing indicated that all distributions are significantly unlikely to come from a normal distribution (p < 0.001), the skewness (s) and excess kurtosis (k) calculations did not indicate any significant levels of non-normality (-2 < s < +2 ; -2 < k < +2). Attempted transformations of the data using logarithmic (log10(x), log2(ex) and ln(x)), square-root (sqrt(x)), and reciprocal (1/x) transformations were unsuccessful. As a result, both parametric and non-parametric statistical tests were performed to account for the mixed results of model fit.

Parametric tests performed on the data included Independent Samples t-tests, One-Way Analysis of Variance (ANOVAs), and Multiple Comparison tests of means. The t-tests assumed unequal variance as indicated by the Q-Q plots in

Supplementary Figures S1-S6. Results of parametric testing are summarized in

Supplementary Tables S1-S5. Nonparametric tests performed on the data included Mann-Whitney U tests (Wilcoxon rank-sum tests), Kruskal-Wallis tests, and Multiple Comparison tests of medians (

Supplementary Tables S6-S9).

Comparisons between the Independent Samples t-tests and Mann-Whitney U tests elucidate that the t-tests remained robust to any deviations from normality present in the data due to the large sample sizes. Both types of central-difference tests identified that the only comparison group with both a significant p-value and significant (or largest) effect size was Unpaired Males vs. Unpaired Females. This was true for the ACC (pparametric < 0.001, d = 0.34, pnonparametric < 0.001, median difference = 3.57), the PFC (pparametric < 0.001, d = 0.25, pnonparametric< 0.001, median difference = 1.56), and the combined regions (pparametric < 0.001, d = 0.32, pnonparametric< 0.001, median difference = 2.98).

Comparisons between the One-Way ANOVAs and Kruskal-Wallis tests elucidate that the one-way ANOVA remained robust to any deviations from normality present in the data due to the large sample sizes. Both types of one-way variance tests identified that group measures of central tendency were significantly different from one another. This was true for the ACC, PFC, and combined regions (pparametric < 0.001, pnonparametric< 0.001). Multiple comparison testing using the mean and median data from the ANOVAs and Kruskal-Wallis test revealed that the difference in means/medians of male paired and female paired microglia was not significant in any of the tested brain regions. All other possible group pairings showed at least one instance of significantly different means/medians.

To better understand the strong evidence for differences in the unpaired male and unpaired female groups produced by the multiple comparison tests, a three-way ANOVA was performed on the data (

Supplementary Table S10). Although a three-way ANOVA assumes normality, the test was still considered valid due to the large sample size. The results produced evidence for a significant main effect of sex (p < 0.001) and a significant interaction effect of sex x pairing status (p < 0.001) on microglia soma size. There was no evidence of main effects for pairing status or brain region. The interaction effects of pairing status x brain region and sex x brain region were not significant.

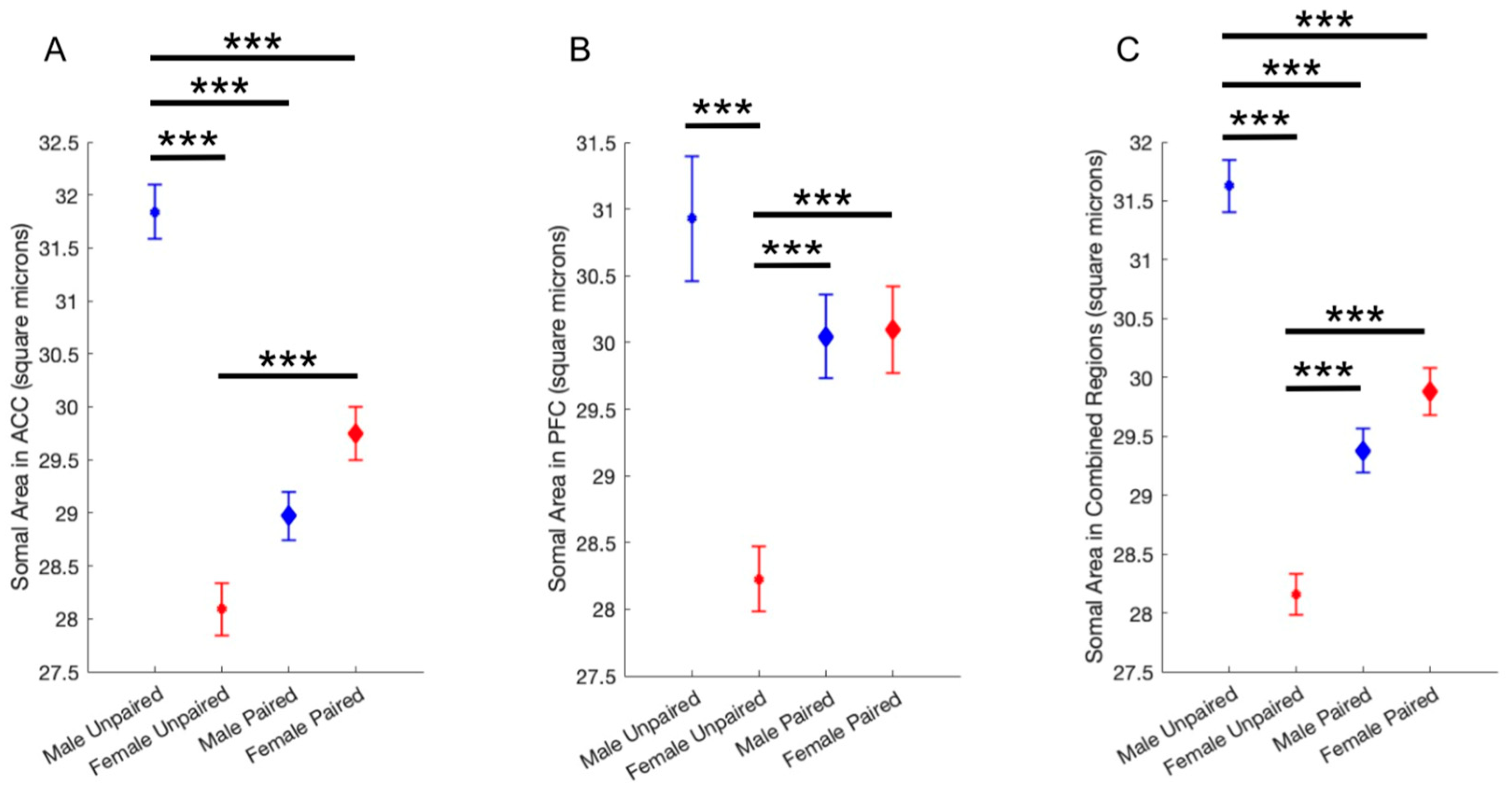

2.3. The Effect of Pair Bonding on Microglia Morphology

Analyses revealed a significant effect of both sex and pairing status on microglia soma size. In both the ACC and the PFC, unpaired males had significantly larger somas than unpaired females. The difference between paired males and females was not significant. However, the somas of paired males and females were significantly different from the somas of unpaired males and females, but in opposite directions (

Figure 3). The data suggests that pair bonding status affects microglia morphology in a sexually dimorphic manner.

3. Discussion

Robust sex differences in microglia reactivity are well-established in mice, rats, and humans [

23,

24]. Soma area can be used to measure microglia reactivity from histological images, as reactive microglia are characterized by large, round somas and few short processes. In the present study, analysis of over 12,000 microglia cells revealed a significant interaction between sex and pairing status with microglia reactivity in the ACC and PFC of prairie voles. A robust array of statistical analyses indicated that microglia in unpaired male voles were significantly more reactive than microglia in unpaired female voles in all tested subjects. While the difference in soma size between unpaired males and unpaired females was the largest, there were also statistically significant differences between paired females and unpaired females, and between paired males and unpaired males. Females showed significant differences in both the ACC and PFC, whereas males showed significant differences in only the ACC. Results revealed no significant differences between paired female and paired male microglia in any brain region. Most importantly, there are no significant differences between all paired and all unpaired microglia: the differences only appear when microglia are separated by sex.

Results from this study are the first to suggest that prairie vole microglia exhibit a sexually dimorphic morphology in both the ACC and PFC. This supports previous work which found evidence for a sexually dimorphic baseline of microglia morphology in the vole PFC, cerebellum, and amygdala [

25]. Additionally, it supports findings by Pohl et al. in which voles separated from their pair-bonded partner exhibited changes in microglia reactivity in the Paraventricular Nucleus (PVN), with sexual dimorphism emerging just four days after partner separation [

26]. Taken together, this evidence for sexual dimorphism of microglia morphology in prairie voles can inform models of how social stress and isolation affect microglia in the prairie vole system.

Compared to non-monogamous rodents, the additional categorical variable of pair bonding status makes identifying the “control” group for prairie voles more challenging. While the present study included two possible pairing statuses for voles (unpaired (sexually naive) and paired), additional research utilizing a third group which has been separated after pair bonding is needed. Results from such study would provide better framing for which pairing status should be considered the homeostatic control group for prairie voles. Additionally, it’s important to note that morphological data on microglia is not to be used or interpreted in isolation. While this study provides proof of concept that sexual dimorphism in prairie vole microglia reactivity likely exists, future transcriptomic studies using single nucleus RNA-sequencing are needed to investigate how microglia morphology relates to microglia function during pair bonding.

Findings from this study are only the fifth set of published experiments to successfully apply murine IHC protocols for Iba1 staining to prairie voles. Our research provides important methodological contributions to the field by documenting a protocol that is affordable and can be easily replicated by other scientists. Additionally, our study uses a different Iba1 antibody than the four previously published studies, broadening the scope of commercially produced antibodies that can be used in prairie voles in the future. The utility of using prairie voles to study diseases of social functioning cannot be understated; thus, future research should continue piloting murine experimental protocols in prairie vole tissue to increase the accessibility and affordability of using prairie voles in research.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Tissue Fixation and Sectioning

Prior to donation of the tissue to the authors, adult prairie voles were euthanized and transcardially perfused using 1x Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS) followed by 4% Paraformaldehyde (PFA). Brains were post-fixed in PFA at 4 degrees Celsius for short-term storage and shipping to the authors. 30-micron coronal sections were obtained serially using a freezing microtome. Sections were stored in PBS with 0.05% sodium azide for long-term storage.

4.2. Immunohistochemistry

Due to prolonged storage in 4% paraformaldehyde during storage and shipping, antigen retrieval was necessary to remove cross-linked formalins. Samples were incubated in 1x Tris-EDTA (TE) Buffer (Fisher BioReagents BP2477-500, pH 7.4) in a water bath at 95-100 degrees Celsius for 40 minutes. Samples were returned to room temperature while submerged in the TE Buffer before being moved to PBS for rinsing. Tissue carriers (Corning NetWell CLS3479, 24mm diameter, 74μm mesh) six well plates, and paint brushes were used for free-floating immunohistochemistry (IHC). Sections were immunostained for Iba1 to label microglia. Reagents were used according to the Abcam Rabbit specific horseradish peroxidase (HRP) / diaminobenzidine (DAB) Detection IHC Kit (ab64261). Sections were washed in 1x PBS. Endogenous peroxidase activity was blocked with the hydrogen peroxide block in 0.3% Triton X-100 and PBS for 15 min at room temperature. Nonspecific binding was blocked with the Protein Block in 0.1% Triton-X 100 and PBS for 30 min at room temperature. Tissue was incubated in primary buffer containing Iba-1 polyclonal antibody (Thermo Fisher Invitrogen PA5-27436 Rabbit IgG) (1:500) for 48 hours at 4 degrees Celsius and a secondary buffer containing biotinylated goat anti-rabbit IgG (H+L) (1:25) for 90 minutes at room temperature. Following incubation in the streptavidin peroxidase for one hour at room temperature, tissue was washed in sterile deionized water and moved to a solution of sterile deionized water containing a 1:25 dilution of 50x DAB Chromogen in DAB Substrate. Sections reacted with DAB for 10 minutes before being moved to a final rinse in PBS. Sections were mounted aqueously onto gel coated slides. Cover slips were placed using aqueous mounting medium (Abcam AB64230) and glass coverslips.

4.3. Imaging and Quantification

Images of the ACC and PFC were captured on an LED microscope using a 10x Leica Objective, Basler camera (acA3088-57uc), and Basler imaging software. Regions of Interest (ROIs) were determined using the Allen Mouse Brain Atlas to approximate vole brain regions. Microglia in the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) and prefrontal cortex (PFC) were counted and traced using the “Analyze Particles” feature in Fiji/ImageJ. PFC was considered as a composite region including the Prelimbic Areas and Infralimbic Areas. Particle threshold was determined to be 10-80 square microns by measuring the soma diameter of 15 random cells, determining the minimum and maximum diameter values, and taking the square of each. Data containing soma area and ROI area for each image were exported and analyzed.

4.4. Statistical Analysis

All statistical analyses were completed using MATLAB R2023a. Independent samples t-tests, one-way ANOVAs, and two-way ANOVAs were completed to test for statistically significant differences in soma size between microglia in males and females and between microglia in paired and unpaired voles.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on

Preprints.org, Figure S1: Male ACC distribution visualizations; Figure S2: Female ACC distribution visualizations; Figure S3: Male PFC distribution visualizations; Figure S4: Female PFC distribution visualizations; Figure S5: Male combined regions distribution visualizations; Figure S6: Female combined regions distribution visualizations; Table S1: Descriptive Statistics of Distributions of Microglia Soma Areas; Table S2: Independent Samples T-Tests: Microglia Soma Size in Vole Anterior Cingulate Cortex (ACC); Table S3: Independent Samples T-Tests: Microglia Soma Size in Vole Prefrontal Cortex (PFC); Table S4: Independent Samples T-Tests: Microglia Soma Size in Combined Regions; Table S5: One-way ANOVA Summary Table for Microglia Soma Area; Table S6: Mann-Whitney U tests: Microglia Soma Size in Vole Anterior Cingulate Cortex (ACC); Table S7: Mann-Whitney U tests: Microglia Soma Size in Vole Prefrontal Cortex (PFC); Table S8: Mann-Whitney U tests: Microglia Soma Size in Combined Regions; Table S9: Kruskal-Wallis Test of One-way Variance Summary Table for Microglia Soma Area; Table S10: Three-way ANOVA Summary Table for Microglia Soma Area

Author Contributions

Methodology, software, formal analysis, investigation, resources, data curation, writing—original draft preparation, T.K.; Conceptualization, validation, writing—review and editing, funding acquisition, T.K. and K.G.; Supervision, project administration, K.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Boston University Undergraduate Research Opportunities Program, Global Challenges Research Award. This research was also funded by Boston University Arvind & Chandan Nandlal Kilachand Honors College, Keystone Project Funds.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Adam Smith at the University of Kansas and Dr. Karen Bales at the University of California Davis for their generous donations of the Microtus ochrogaster brain tissue used in this study. We thank Drs. Tuan Leng Tay, Kristen Bushell, and Mario Muscedere at Boston University for their language editing of the manuscript and helpful discussions related to data analysis and presentation. We thank Dr. Zoe Donaldson for helpful discussions. We thank Liam Quidore at Boston University for his technical assistance with laboratory maintenance tasks during experiment preparation and execution. We thank the Undergraduate Program in Neuroscience at Boston University for donating the laboratory space for experiment execution.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| PFC |

Prefrontal Cortex |

| ACC |

Anterior Cingulate Cortex |

| Iba1 |

Ionized calcium-binding adaptor molecule I |

| IHC |

Immunohistochemistry |

| NAc |

Nucleus Accumbens |

| AG |

Amygdala |

| mm2 |

Square millimeters |

| Q-Q |

Quartile-quartile |

| s |

Skewness |

| k |

Kurtosis |

| ANOVA |

Analysis of Variance |

| PVN |

Paraventricular Nucleus |

| PBS |

Phosphate Buffered Saline |

| PFA |

Paraformaldehyde |

| TE |

Tris-EDTA |

| HRP |

Horseradish Peroxidase |

| DAB |

Diaminobenzidine |

| ROI |

Region of Interest |

References

- Young, K.A., et al., The neurobiology of pair bonding: insights from a socially monogamous rodent. Front Neuroendocrinol, 2011. 32(1): p. 53-69. [CrossRef]

- Aragona, B.J. and Z. Wang, The prairie vole (Microtus ochrogaster): an animal model for behavioral neuroendocrine research on pair bonding. ILAR J, 2004. 45(1): p. 35-45. [CrossRef]

- Gunnar, M.R., Quality of early care and buffering of neuroendocrine stress reactions: potential effects on the developing human brain. Prev Med, 1998. 27(2): p. 208-11. [CrossRef]

- Ditzen, B., et al., Adult attachment and social support interact to reduce psychological but not cortisol responses to stress. J Psychosom Res, 2008. 64(5): p. 479-86. [CrossRef]

- Badanes, L.S., J. Dmitrieva, and S.E. Watamura, Understanding Cortisol Reactivity across the Day at Child Care: The Potential Buffering Role of Secure Attachments to Caregivers. Early Child Res Q, 2012. 27(1): p. 156-165. [CrossRef]

- Hiura, L.C. and Z.R. Donaldson, Prairie vole pair bonding and plasticity of the social brain. Trends Neurosci, 2023. 46(4): p. 260-262. [CrossRef]

- Li, Q. and B.A. Barres, Microglia and macrophages in brain homeostasis and disease. Nat Rev Immunol, 2018. 18(4): p. 225-242. [CrossRef]

- Sierra, A., R.C. Paolicelli, and H. Kettenmann, Cien Anos de Microglia: Milestones in a Century of Microglial Research. Trends Neurosci, 2019. 42(11): p. 778-792. [CrossRef]

- Umpierre, A.D. and L.J. Wu, Microglia Research in the 100th Year Since Its Discovery. Neurosci Bull, 2020. 36(3): p. 303-306. [CrossRef]

- Loth, M.K. and Z.R. Donaldson, Oxytocin, Dopamine, and Opioid Interactions Underlying Pair Bonding: Highlighting a Potential Role for Microglia. Endocrinology, 2021. 162(2). [CrossRef]

- Donovan, M., et al., Social isolation alters behavior, the gut-immune-brain axis, and neurochemical circuits in male and female prairie voles. Neurobiol Stress, 2020. 13: p. 100278. [CrossRef]

- Donovan, M.L., et al., Post-weaning Social Isolation in Male and Female Prairie Voles: Impacts on Central and Peripheral Immune System. Front Behav Neurosci, 2021. 15: p. 802569. [CrossRef]

- Leyh, J., et al., Classification of Microglial Morphological Phenotypes Using Machine Learning. Front Cell Neurosci, 2021. 15: p. 701673. [CrossRef]

- Paolicelli, R.C., et al., Microglia states and nomenclature: A field at its crossroads. Neuron, 2022. 110(21): p. 3458-3483. [CrossRef]

- Madry, C., et al., Microglial Ramification, Surveillance, and Interleukin-1beta Release Are Regulated by the Two-Pore Domain K(+) Channel THIK-1. Neuron, 2018. 97(2): p. 299-312 e6. [CrossRef]

- Shamay-Tsoory, S.G., I.Z. Marton-Alper, and A. Markus, Post-interaction neuroplasticity of inter-brain networks underlies the development of social relationship. iScience, 2024. 27(2): p. 108796. [CrossRef]

- Tay, T.L., et al., Microglia Gone Rogue: Impacts on Psychiatric Disorders across the Lifespan. Front Mol Neurosci, 2017. 10: p. 421. [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.J., et al., Deficient autophagy in microglia impairs synaptic pruning and causes social behavioral defects. Mol Psychiatry, 2017. 22(11): p. 1576-1584. [CrossRef]

- Piirainen, S., et al., Microglia contribute to social behavioral adaptation to chronic stress. Glia, 2021. 69(10): p. 2459-2473. [CrossRef]

- Nelson, L.H. and K.M. Lenz, Microglia depletion in early life programs persistent changes in social, mood-related, and locomotor behavior in male and female rats. Behav Brain Res, 2017. 316: p. 279-293. [CrossRef]

- Eisenberger, N.I., Meta-analytic evidence for the role of the anterior cingulate cortex in social pain. Soc Cogn Affect Neurosci, 2015. 10(1): p. 1-2. [CrossRef]

- Lai, C.H., Promising Neuroimaging Biomarkers in Depression. Psychiatry Investig, 2019. 16(9): p. 662-670. [CrossRef]

- Barko, K., et al., Brain region- and sex-specific transcriptional profiles of microglia. Front Psychiatry, 2022. 13: p. 945548. [CrossRef]

- Bollinger, J.L., C.M. Bergeon Burns, and C.L. Wellman, Differential effects of stress on microglial cell activation in male and female medial prefrontal cortex. Brain Behav Immun, 2016. 52: p. 88-97. [CrossRef]

- Marinello, W.P., et al., Effects of developmental exposure to FireMaster(R) 550 (FM 550) on microglia density, reactivity and morphology in a prosocial animal model. Neurotoxicology, 2022. 91: p. 140-154. [CrossRef]

- Pohl, T.T., et al., Microglia react to partner loss in a sex- and brain site-specific manner in prairie voles. Brain Behav Immun, 2021. 96: p. 168-186. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).