1. Introduction

Pediatric Intermediate Care Units (PIMCUs) play a crucial role in managing children who require closer monitoring than in general pediatric wards but do not yet require full Pediatric Intensive Care Unit (PICU) support [

1,

2]. Their relevance has increased with the growing complexity of pediatric illnesses and technological advancements that enable better outcomes for critically ill children while easing pressure on PICU resources.

The definition of PIMCU remains heterogeneous. Also referred to as high-dependency, progressive, or step-up units, PIMCUs offer intensive observation and treatment for children at risk of physiological deterioration. They can also function as step-down units for patients recovering from critical illness or surgery [

3].

By bridging the gap between general wards and intensive care, PIMCUs offer higher nurse-patient ratios, specialized staff, and support for interventions such as non-invasive ventilation [

4]. Patient safety is a key target for PIMCU activity. Ensuring patient safety involves the timely recognition of deterioration, targeted interventions, appropriate admission criteria, and the efficient allocation of resources.

The American Academy of Pediatrics first published admission and discharge criteria for children requiring admission to PIMCU in 2004 [

1], with a recent update in 2022 [

3].

Most studies that have explored the reasons for clinical deterioration and the clinical profile of pediatric inpatients have primarily focused on children admitted to general wards or the Emergency Department (ED) [

5,

6,

7,

8,

9]. These studies highlighted that among children subsequently admitted to intensive care, those transferred from general wards had higher crude mortality rates than those admitted directly from the ED. In response, many pediatric hospitals have implemented Medical Emergency Teams (METs) to facilitate early recognition and treatment of deteriorating children [

10,

11,

12].

An additional, yet underexplored, strategy is the development of Pediatric Intermediate Care Units (PIMCUs), which enable closer monitoring and surveillance, potentially allowing for earlier detection of clinical decline and reducing the need for unplanned PICU transfers.

Despite their growing role, research on the functioning of PIMCUs and the identification of specific predictive factors for clinical deterioration or prolonged hospitalization remains limited [

13,

14,

15]. Understanding which characteristics at admission are associated with adverse outcomes or longer stays is critical both for clinical decision-making and for optimal resource allocation.

The present study aimed to evaluate the characteristics of patients admitted to an independent PIMCU in a large tertiary Italian pediatric hospital. Specifically, we sought to identify (1) which initial factors were associated with early unplanned transfer to the PICU within the first 48 hours, and (2) which variables at admission correlated with a longer length of stay in PIMCU. These insights may support improved triage decisions, tailored monitoring strategies, and more efficient use of intermediate care resources.

2. Materials and Methods

We conducted a retrospective observational single-center cohort study, including all children admitted to the PIMCU of IRCCS Gaslini Children’s Hospital (Genoa, Italy) from 1 January 2022 to 30 June 2023.

For each patient, demographic data (age, sex, origin), clinical characteristics (pre-existing condition, the main reason for admission, vital parameters adjusted for age [blood pressure, breathing rate, heart rate, SatO2, body temperature], respiratory support, medical device, bedside pediatric early warning score [BPEWS]), and blood tests on admission, and 28-day mortality after PIMCU discharge were collected.

Vital parameters were assessed based on the Pediatric Advanced Life Support (PALS) algorithm [

16]. Medical devices were included according to the national classification of medical devices (CND) [

17]. The BPEWS is a warning score system largely validated as a tool for early recognition of pediatric patient deterioration [

18].

The PIMCU was introduced in 2020 as a standalone unit adjacent to a quaternary-level PICU, offering critical care transport and extracorporeal membrane oxygenation retrieval capabilities. Further details on staff, equipment, and organization have already been published [

19].

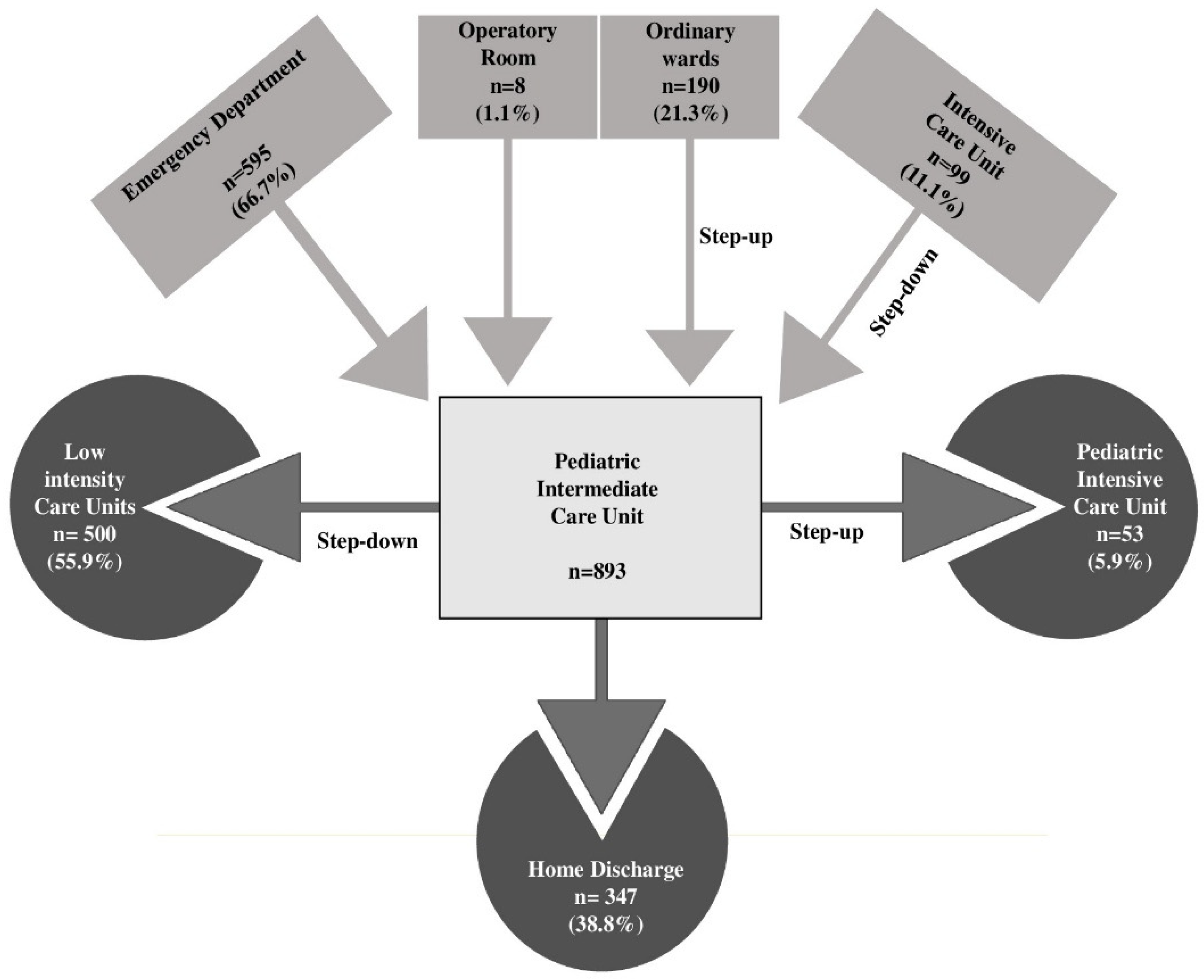

PIMCU receives acute patients from the ED, patients from general pediatric wards or other regional pediatric hospitals requiring care intensification, post-surgical patients from the operating rooms, and children from the PICU as the initial step-down phase of care. When clinical stability is achieved, children are transferred to general wards or may be directly discharged home in case of rapid clinical improvement. Conversely, children who develop clinical deterioration are admitted to the PICU. The admission and discharge criteria for both PIMCU and PICU were developed with input from multiple stakeholders and reflect the availability of resources, clinical experience, and guidance from the American Academy of Pediatrics document on the structuring of PIMCUs (3) (

Supplementary Materials 1).

Descriptive analysis was performed, reporting median and interquartile range (IQR) for all continuous variables due to their non-normal distribution, and absolute and relative frequencies for categorical variables. To identify factors associated with IMCU LOS in days, a Generalized Linear Model (GLM) with a Negative Binomial distribution and a log link function was employed, accounting for the count nature and right-skewed distribution of LOS. To assess risk factors for PICU transfer within 48 hours of IMCU admission, initial comparisons between patient groups were conducted using the Mann-Whitney U test for continuous variables and chi-square/Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables. Variables showing a p-value < 0.05 in univariable analysis were subsequently included in a multivariable binary logistic regression model. For both the GLM and logistic regression models, collinearity among predictors was assessed using the Variance Inflation Factor (VIF), with a cutoff of VIF > 5 indicating problematic collinearity. In our multivariable model for PIMCU length of stay, various blood test parameters (e.g., C-reactive protein, procalcitonin, white blood cells, etc.) were initially considered for inclusion. However, these variables were ultimately excluded from the final multivariable model, as their addition negatively impacted the model’s overall fit and explanatory power, resulting in a reduction in the pseudo R-squared. Furthermore, from a clinical standpoint, their independent contribution to predicting length of stay was considered less direct compared to objective physiological or device-related markers present at admission. All statistical analyses were conducted using Jamovi (version 2.6.23) with the GAMLj3 add-on.

3. Results

3.1. Patient Characteristics and Flow

Overall, 928 patients were managed in the PIMCU during the study period. We excluded 35 children who had a planned admission directly from their homes, as these were complex patients admitted in anticipation of procedures or surgical interventions and therefore had a markedly higher baseline risk of requiring subsequent admission to intensive care. The remaining 893 patients were included in the analysis, with a median age of 4.0 years (IQR 6–128 months) and a slight predominance of males (55% vs. 45%).

Most children came from the Emergency Department (66.7%), followed by patients from general pediatric wards or local hospitals (21.3%) and those transferred from the PICU (11.1%) (

Figure 1).

More than half of the primary reasons for PIMCU admission were respiratory (26.7%), neurologic (19.6%), and infectious (13.8%) conditions.

A significant proportion of the PIMCU population (67.5%) had a pre-existing condition, with the most frequent being neurological (17%) and hematological (12.9%) diseases. At least one medical device was present on admission in 31.7% of patients, with central venous catheters being the most common (16.7%).

Overall, children spent a median of 4 days (IQR 2–7) in the PIMCU. Fifty-three (5.9%) patients required PICU admission for further clinical deterioration, 25 (2.8%) of them within the first 48 hours. Among the others, 55.8% were moved to a lower-intensity care unit after clinical improvement, and 38.9% were directly discharged home (

Figure 1). One patient died during the PIMCU stay in a palliative care program, while 11 (1.2%) died within 28 days of IMCU discharge.

3.2. Analysis of Risk Factors for PICU Admission

No significant differences were observed between children who required early transfer to the PICU and those who did not, in terms of age, sex, origin, or reason for admission. However, patients requiring ICU admission showed greater clinical complexity, with a higher prevalence of pre-existing conditions (p < 0.001) and medical devices at admission (p < 0.001).

In the multivariate analysis (

Table 1) we found that tachypnea adjusted for age (OR = 2.80; 95% CI: 1.19–6.56; p = 0.018) and nasogastric tube on admission (OR = 3.72; 95% CI: 1.30–10.57; p = 0.014) were independently associated with increased risk of early ICU transfer.

No significant associations were found with the BPEWS and lab tests at admission.

3.3. Factors Influencing PIMCU Length of Stay

The GLM showed that the need for respiratory support (IRR = 1.36; 95% CI: 1.02–1.81; p = 0.035) and the presence of a medical device on admission were strongly associated with prolonged PIMCU hospitalization. Among medical devices, nasogastric tube (IRR = 1.63 (95% CI: 1.15–2.30; p = 0.005), central venous line (IRR = 1.73 (95% CI: 1.31–2.27; p < 0.001), and thoracic or abdominal drainage (IRR = 3.17 (95% CI: 1.81–5.56; p < 0.001) were all independently associated with longer PIMCU stays (

Table 2).

4. Discussion

Our study analyzed the activity of an independent Pediatric Intermediate Care Unit (PIMCU) in a tertiary Italian pediatric hospital, focusing on identifying admission factors predictive of two critical outcomes: early unplanned transfer to the Pediatric Intensive Care Unit (PICU) and prolonged length of stay (LOS) in the PIMCU. Understanding these aspects is essential for optimizing patient safety, quality of care, and resource allocation.

Unplanned PICU transfers are a sensitive marker of clinical deterioration and can reflect the adequacy of triage decisions and the quality and intensity of care in PIMCUs [

15]. Most literature addressing the risk of clinical deterioration has focused on general wards or emergency settings [

9,

20,

21], with less attention paid to the PIMCU population, whose characteristics differ significantly. Our findings provide important insight into this understudied group.

A significant proportion of patients admitted to PIMCU had pre-existing conditions and medical devices, both of which were independently associated with increased risk of PICU transfer and longer PIMCU stays. These findings underscore the PIMCU’s role in managing medically complex children who, while not in critical condition, require a higher level of surveillance and tailored care plans. However, such patients remain at elevated risk of deterioration due to their fragile clinical status [

22,

23,

24].

Among the most relevant predictors of adverse outcomes, tachypnea at admission was independently associated with early PICU transfer. Tachypnea is often one of the earliest and most sensitive indicators of respiratory or systemic distress in children, frequently preceding other signs of clinical deterioration such as hypoxemia, altered mental status, or hemodynamic instability.

In the pediatric population, where compensatory mechanisms are initially effective, an elevated respiratory rate may reflect an early stage of decompensation that is not yet clinically overt. Our observations underline the prognostic value of respiratory rate as a dynamic clinical parameter and support its integration into early warning systems and triage protocols, also within intermediate care settings. Furthermore, this finding may suggest a need for better training of medical and nursing staff on the therapeutic management and monitoring of patients with respiratory impairment and a different allocation of resources.

In addition, the need for respiratory support at admission was a strong predictor of prolonged PIMCU stay. This likely reflects both the underlying severity of the patient’s condition and the resource-intensive nature of managing respiratory insufficiency. Patients requiring respiratory support, especially high-flow nasal cannula or non-invasive ventilation often require extended monitoring, specialized nursing care, and a longer stabilization period before being eligible for step-down or discharge.

These findings emphasize the importance of early identification of respiratory compromise and appropriate allocation of resources, including skilled personnel and equipment, to support these patients effectively within the PIMCU.

The presence of a NGT on admission also emerged as a significant predictor of both adverse outcomes. This observation may reflect the NGT’s role as a proxy indicator of both underlying clinical severity and impaired oral feeding capacity, particularly in patients with respiratory distress, neurological compromise, or hemodynamic instability. The placement of an NGT often indicates the need for nutritional support in patients who are unable to maintain adequate oral intake due to altered mental status, respiratory fatigue, or the risk of aspiration. These conditions are frequently markers of more complex clinical trajectories and may predispose patients to rapid deterioration requiring escalation of care. Furthermore, the presence of an NGT may correlate with other signs of fragility, such as increased work of breathing or persistent vomiting, which are not always fully captured by standard clinical scores but can significantly impact the patient’s stability. Accordingly, the enteral tube has been previously recognized as part of a 7-item score associated with the clinical deterioration of hospitalized children [

25].

Interestingly, our analysis did not identify age or laboratory values at admission as independent predictors of adverse outcomes. Younger age is largely known as a critical factor associated with a higher risk of clinical deterioration, according to a combination of several factors (physiological immaturity, higher vulnerability to infections, potentially delayed recognition of serious conditions, etc.) [

26,

27,

28]. Although children < 1 year of age accounted for a relevant part of our PIMCU population (31%), they were not significantly associated with poor outcomes. This emphasizes the role of the PIMCU as an appropriate setting for the care of young children by a healthcare team trained in the interpretation of age-related vital signs and the recognition of early signs of decompensation.

Similarly, while laboratory markers are often used to assess disease severity, they may not capture early physiological changes that precede overt clinical decompensation, highlighting the need for a holistic and dynamic clinical assessment.

Our findings support a multifactorial approach to risk prediction that integrates vital signs, device presence, and clinical context rather than relying solely on static laboratory values. Implementing structured early warning systems and training teams to interpret early signs of deterioration could enhance the PIMCU’s role in preventing unplanned ICU transfers.

The median PIMCU stay of 4 days aligns with literature values [

13,

14,

29], confirming its function as a setting for intensive yet time-limited care. Our low rate of PICU transfer (5.3%) suggests that patients are appropriately triaged to PIMCU and managed safely, with escalation of care occurring when clinically justified. This is relevant when we examine the benefits of introducing a PIMCU to the PICU’s operations. A safe and well-functioning PIMCU may reduce ICU admissions and overcrowding, favoring a better utilization of critical beds [

30]. Furthermore, PIMCU also played a significant role as a step-down unit offering a crucial transition space in the initial phase of care reduction, potentially decreasing ICU stays, and healthcare costs, and enhancing patient comfort.

Lastly, we observed a notable subgroup of patients who were transferred from the PICU and subsequently re-admitted to intensive care (7%). Although not statistically significant, this trend highlights the importance of cautious patient selection and close monitoring during step-down phases. Coordinated communication between PICU and PIMCU teams is essential to ensure safe transitions.

Our study has several limitations, including its retrospective design and heterogeneous patient population. Furthermore, we did not assess the specific treatments required post-transfer to the PICU, nor the reasons for deterioration in detail. The novelty of the PIMCU at our institution may also have influenced our results, as practices and expertise continue to evolve.

We conducted a limited comparison with existing literature, considering that research focusing on pediatric IMCU is minimal. In Italy, this may be linked to the lack of specific regulatory legislation, resulting in significant variability in terms of setting, equipment, and staffing of PIMCUs [

31]. Following this, the single-center nature of the study may also limit the generalizability of our findings, because of site-specific practices and policies, including the availability of staff and equipment, and the hospital organization.

Nevertheless, this study contributes to the limited but growing body of knowledge on pediatric intermediate care and highlights practical factors that can improve triage, care delivery, and patient outcomes.

5. Conclusions

We identified a set of admission characteristics—including tachypnea, need for respiratory support, and presence of medical devices—that are associated with early unplanned PICU transfer and prolonged PIMCU stay. These findings reinforce the role of clinical observation and early recognition of physiological compromise in guiding patient management. A well-functioning PIMCU contributes to improved outcomes, reduced PICU crowding, and more efficient use of healthcare resources. Further multicenter studies are needed to validate these predictors and develop standardized approaches to pediatric intermediate care.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org, Document 1: Admission and discharge criteria for PIMCU and PICU.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Giacomo Brisca, Carlotta Pepino and Daniela Pirlo; Data curation, Marcello Mariani and Rossana Taravella; Formal analysis, Carlotta Pepino, Marcello Mariani, Giacomo Tardini, Marta Romanengo, Emanuele Giacheri, Marisa Mallamaci, Isabella Buffoni, Valentina Carrato, Marina Strati, Stefania Santaniello, Rossana Taravella, Laura Puzone, Lisa Rossoni and Michela Di Filippo; Investigation, Giacomo Tardini, Marta Romanengo, Emanuele Giacheri, Marisa Mallamaci, Isabella Buffoni, Valentina Carrato, Marina Strati, Stefania Santaniello, Rossana Taravella, Laura Puzone, Lisa Rossoni and Michela Di Filippo; Methodology, Marcello Mariani; Resources, Daniela Pirlo; Supervision, Andrea Moscatelli; Validation, Giacomo Brisca, Daniela Pirlo and Andrea Moscatelli; Writing – original draft, Giacomo Brisca, Carlotta Pepino, Rossana Taravella, Laura Puzone, Lisa Rossoni and Michela Di Filippo; Writing – review & editing, Giacomo Brisca, Giacomo Tardini, Marta Romanengo, Emanuele Giacheri, Marisa Mallamaci, Isabella Buffoni, Valentina Carrato, Marina Strati, Stefania Santaniello, Daniela Pirlo and Andrea Moscatelli.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration. According to Italian legislation, the study did not need ethical approval, as it was a purely observational retrospective study on routinely collected anonymous data.

Informed Consent Statement

It was not possible to request informed consent for participation in the study, given the nature of the study. In any case, consent to completely anonymous use of clinical data for research/epidemiological purposes is requested during clinical routine at the time of admission/diagnostic procedure.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

PIMCU, Pediatric Intermediate Care Unit; PICU, Pediatric Intensive Care Unit; ED, Emergency Department; MET, Medical Emergency Team; BPEWS, Bedside Pediatric Early Warning Score; PALS, Pediatric Advanced Life Support; CND, National Classification of Medical Devices; GLM, Generalized Linear Model; LOS, Length of Stay; ICU, Intensive Care Unit; VIF, Variance Inflation Factor; CRP, C-Reactive Protein; PCT, Procalcitonin; WBC, White Blood Cell count; IQR, Interquartile Range; OR, Odds Ratio; CI, Confidence Interval; IRR, Incidence Rate Ratio; NGT, Nasogastric Tube.

References

- Jaimovich DG; American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Hospital Care and Section on Critical Care. Admission and discharge guidelines for the pediatric patient requiring intermediate care. Pediatrics. 2004 May;113(5):1430-3. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geneslaw AS, Jia H, Lucas AR, Agus MSD, Edwards JD. Pediatric intermediate care and pediatric intensive care units: PICU metrics and an analysis of patients that use both. J Crit Care. 2017;41:268–274.

- Ettinger NA, Hill VL, Russ CM, Rakoczy KJ, Fallat ME, Wright TN, Choong K, Agus MSD, Hsu B; SECTION ON CRITICAL CARE, COMMITTEE ON HOSPITAL CARE, SECTION ON SURGERY; Mack E, Day S, Lowrie L, Siegel L, Srinivasan V, Gadepalli S, Hirshberg EL, Kissoon N, October T, Tamburro RF, Rotta A, Tellez S, Rauch DA, Ernst K, Vinocur C, Lam VT, Romito B, Hanson N, Gigli KH, Mauro M, Leonard MS, Alexander SN, Davidoff A, Besner GE, Browne M, Downard CD, Gow KW, Islam S, Saunders Walsh D, Williams RF, Thorne V. Guidance for Structuring a Pediatric Intermediate Care Unit. Pediatrics. 2022 May 1;149(5):e2022057009. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Plate JDJ, Leenen LPH, Houwert M, Hietbrink F. Utilisation of intermediate care units: a systematic review. Crit Care Res Pract. 2017;2017:8038460.

- Brilli RJ, Gibson R, Luria JW, Wheeler TA, Shaw J, Linam M, Kheir J, McLain P, Lingsch T, Hall-Haering A, McBride M. Implementation of a medical emergency team in a large pediatric teaching hospital prevents respiratory and cardiopulmonary arrests outside the intensive care unit. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2007 May;8(3):236-46; quiz 247. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gregory CJ, Nasrollahzadeh F, Dharmar M, Parsapour K, Marcin JP. Comparison of critically ill and injured children transferred from referring hospitals versus in-house admissions. Pediatrics. 2008 Apr;121(4):e906-11. PMID: 18381519.Odetola FO, Rosenberg AL, Davis MM, et al.: Do outcomes vary according to the source of admission to the pediatric intensive care unit? Pediatr Crit Care Med 2008; 9:20–25. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mansel KO, Chen SW, Mathews AA, Gothard MD, Bigham MT. Here and Gone: Rapid Transfer From the General Care Floor to the PICU. Hosp Pediatr. 2018 Sep;8(9):524-529. Epub 2018 Aug 7. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miles AH, Spaeder MC, Stockwell DC. Unplanned ICU Transfers from Inpatient Units: Examining the Prevalence and Preventability of Adverse Events Associated with ICU Transfer in Pediatrics. J Pediatr Intensive Care. 2016 Mar;5(1):21-27. Epub 2015 Nov 21. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Maharaj R, Raffaele I, Wendon J: Rapid response systems: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit Care 2015; 19:254.

- Chan PS, Jain R, Nallmothu BK, Berg RA, Sasson C. Rapid Response Teams: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Arch Intern Med. 2010 Jan 11;170(1):18-26. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Humphreys S, Totapally BR. Rapid Response Team Calls and Unplanned Transfers to the Pediatric Intensive Care Unit in a Pediatric Hospital. Am J Crit Care. 2016 Jan;25(1):e9-13. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chapman SM, Grocott MP, Franck LS. Systematic review of paediatric alert criteria for identifying hospitalized children at risk of critical deterioration. Intensive Care Med. 2010;36(4):600–61.

- Cheng DR, Hui C, Langrish K, Beck CE. Anticipating Pediatric Patient Transfers From Intermediate to Intensive Care. Hosp Pediatr. 2020 Apr;10(4):347-352. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamze-Sinno R, Abdoul H, Neve M, Tsapis M, Jones P, Dauger S. Can we easily anticipate on admission pediatric patient transfers from intermediate to intensive care? Minerva Anestesiol. 2011 Oct;77(10):1022-3. [PubMed]

- Vincent JL, Rubenfeld GD. Does intermediate care improve patient outcomes or reduce costs? Crit Care. 2015 Mar 2;19(1):89. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

-

https://www.acls-pals-bls.com/algorithms/pals/Accessed on 10 June 2025.

-

https://www.dati.salute.gov.it/it/dataset/classificazione-nazionale-dei-dispositivi-medici-cnd/Accessed on

10 June 2025.

- Parshuram CS, Duncan HP, Joffe AR, Farrell CA, Lacroix JR, Middaugh KL, Hutchison JS, Wensley D, Blanchard N, Beyene J, Parkin PC. Multicentre validation of the bedside paediatric early warning system score: a severity of illness score to detect evolving critical illness in hospitalised children. Crit Care. 2011 Aug 3;15(4):R184. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Brisca G, Tardini G, Pirlo D, Romanengo M, Buffoni I, Mallamaci M, Carrato V, Lionetti B, Molteni M, Castagnola E, Moscatelli A. Learning from the COVID-19 pandemic: IMCU as a more efficient model of pediatric critical care organization. Am J Emerg Med. 2023 Feb;64:169-173. Epub 2022 Dec 17. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Delgado MK, Liu V, Pines JM, Kipnis P, Gardner MN, Escobar GJ. Risk factors for unplanned transfer to intensive care within 24 hours of admission from the emergency department in an integrated healthcare system. J Hosp Med. 2013 Jan;8(1):13-9. Epub 2012 Sep 28. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reese J, Deakyne SJ, Blanchard A, Bajaj L. Rate of preventable early unplanned intensive care unit transfer for direct admissions and emergency department admissions. Hosp Pediatr. 2015 Jan;5(1):27-34. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan T, Rodean J, Richardson T, Farris RWD, Bratton SL, Di Gennaro JL, Simon TD. Pediatric Critical Care Resource Use by Children with Medical Complexity. J Pediatr. 2016 Oct;177:197-203.e1. Epub 2016 Jul 21. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Russell CJ, Simon TD. Care of children with medical complexity in the hospital setting. Pediatr Ann. 2014 Jul;43(7):e157-62. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heneghan JA, Goodman DM, Ramgopal S. Variable Identification of Children With Medical Complexity in United States PICUs. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2023 Jan 1;24(1):56-61. Epub 2022 Nov 18. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonafide CP, Holmes JH, Nadkarni VM, Lin R, Landis JR, Keren R. Development of a score to predict clinical deterioration in hospitalized children. J Hosp Med. 2012 Apr;7(4):345-9. Epub 2011 Nov 17. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jensen CS, Kirkegaard H, Aagaard H, Olesen HV. Clinical profile of children experiencing in-hospital clinical deterioration requiring transfer to a higher level of care. J Child Health Care. 2019 Dec;23(4):522-533. Epub 2018 Aug 19. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krmpotic K, Lobos AT, Chan J, Toppozini C, McGahern C, Momoli F, Plint AC. A Retrospective Case-Control Study to Identify Predictors of Unplanned Admission to Pediatric Intensive Care Within 24 Hours of Hospitalization. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2019 Jul;20(7):e293-e300. https://doi.org/10.1097/PCC.0000000000001977. Erratum in: Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2019 Nov;20(11):1108. https://doi.org/10.1097/PCC.0000000000002142. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krmpotic K, Lobos AT. Clinical profile of children requiring early unplanned admission to the PICU. Hosp Pediatr. 2013 Jul;3(3):212-8. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lampin ME, Duhamel A, Béhal H, Leteurtre S, Leclerc F, Recher M. Patient Characteristics and Severity Trajectories in a Pediatric Intermediate Care Unit. Indian J Pediatr. 2025 Feb;92(2):150-156. Epub 2023 Nov 16. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Solberg BC, Dirksen CD, Nieman FH, van Merode G, Ramsay G, Roekaerts P, Poeze M. Introducing an integrated intermediate care unit improves ICU utilization: a prospective intervention study. BMC Anesthesiol. 2014 Sep 6;14:76. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Sfriso F, Biban P, Paglietti MG, Giuntini L, Rufini E, Mondardini MC, Zaglia F, Cutrera R, De Zan F, Amigoni A; of the Paediatric Intermediate Care Unit Working Group of the Medical and Nursing Academy of Paediatric Emergency and Intensive Care. Distribution and characteristics of Italian paediatric intermediate care units in Italy: A national survey. Acta Paediatr. 2020 May;109(5):1062-1063. Epub 2019 Nov 29. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).