Submitted:

01 August 2025

Posted:

04 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Structural Features of the CRC Protein

2.2. Regulatory Roles of WUSCHEL, AGAMOUS, and CRABS CLAW in Floral Meristem Termination

2.3. Regulation of Floral Meristem Termination by AG and CRC via Auxin Metabolism Control

2.4. Molecular Network and Gene Interactions Involving CRC

2.5. Polymorphisms and Functional Mutations in the CRC Gene

2.6. Phylogenetic Insights into CRC Gene Lineage

3. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Orashakova, S.; Lange, M.; Lange, S.; Wege, S.; Becker, A. The CRABS CLAW ortholog from California poppy (Eschscholzia californica, Papaveraceae), EcCRC, is involved in floral meristem termination, gynoecium differentiation and ovule initiation. Plant J. 2009, 58, 682–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, C.; Thong, Z.; Yu, H. Coming into bloom: the specification of floral meristems. Development. 2009, 136, 3379–3391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castañeda, L.; Giménez, E.; Pineda, B.; García-Sogo, B.; Ortiz-Atienza, A.; Micol-Ponce, R.; Angosto, T.; Capel, J.; Moreno, V.; Yuste-Lisbona, F.J.; Lozano, R. Tomato CRABS CLAW paralogues interact with chromatin remodelling factors to mediate carpel development and floral determinacy. New Phytol. 2022, 234, 1059–1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bowman, J.L.; Smyth, D.R. CRABS CLAW, a gene that regulates carpel and nectary development in Arabidopsis, encodes a novel protein with zinc finger and helix-loop-helix domains. Development. 1999, 126, 2387–2396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golz, J.F.; Hudson, A. Plant development: YABBYs claw to the fore. Curr Biol. 1999, 9, R861–R863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, K.; Lai, M.; Zhao, T.; Yang, X.; An, X.; Chen, Z. Plant YABBY transcription factors: a review of gene expression, biological functions, and prospects. Crit Rev Biotechnol. 2025, 45, 214–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamaguchi, T.; Nagasawa, N.; Kawasaki, S.; Matsuoka, M.; Nagato, Y.; Hirano, H.Y. The YABBY gene DROOPING LEAF regulates carpel specification and midrib development in Oryza sativa. Plant Cell. 2004, 16, 500–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohmori, Y.; Toriba, T.; Nakamura, H.; Ichikawa, H.; Hirano, H.Y. Temporal and spatial regulation of DROOPING LEAF gene expression that promotes midrib formation in rice. Plant J. 2011, 65, 77–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abiko, M.; Ohmori, Y.; Hirano, H.Y. Genome-wide expression profiling and identification of genes under the control of the DROOPING LEAF gene during midrib development in rice. Genes Genet Syst. 2008, 83, 237–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, E.; Wang, X.; Li, T.; Guo, F.; Ito, T.; Sun, B. Robust control of floral meristem determinacy by position-specific multifunctions of KNUCKLES. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 2021, 118, e2102826118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, B.; Zhou, Y.; Cai, J.; Shang, E.; Yamaguchi, N.; Xiao, J.; Looi, L.S.; Wee, W.Y.; Gao, X.; Wagner, D.; Ito, T. Integration of Transcriptional Repression and Polycomb-Mediated Silencing of WUSCHEL in Floral Meristems. Plant Cell. 2019, 31, 1488–1505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamaguchi, N.; Huang, J.; Tatsumi, Y.; Abe, M.; Sugano, S.S.; Kojima, M.; Takebayashi, Y.; Kiba, T.; Yokoyama, R.; Nishitani, K.; Sakakibara, H.; Ito, T. Chromatin-mediated feed-forward auxin biosynthesis in floral meristem determinacy. Nat Commun. 2018, 9, 5290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamaguchi, N.; Huang, J.; Xu, Y.; Tanoi, K.; Ito, T. Fine-tuning of auxin homeostasis governs the transition from floral stem cell maintenance to gynoecium formation. Nat Commun. 2017, 8, 1125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herrera-Ubaldo, H.; Campos, S.E.; López-Gómez, P.; Luna-García, V.; Zúñiga-Mayo, V.M.; Armas-Caballero, G.E.; González-Aguilera, K.L.; DeLuna, A.; Marsch-Martínez, N.; Espinosa-Soto, C.; de Folter, S. The protein-protein interaction landscape of transcription factors during gynoecium development in Arabidopsis. Mol Plant. 2023, 16, 260–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Müller, C.J.; Larsson, E.; Spíchal, L.; Sundberg, E. Cytokinin-Auxin Crosstalk in the Gynoecial Primordium Ensures Correct Domain Patterning. Plant Physiol. 2017, 175, 1144–1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Wang, R.; Zi, H.; Li, Y.; Cao, X.; Li, D.; Guo, L.; Tong, J.; Pan, Y.; Jiao, Y.; Liu, R.; Xiao, L.; Liu, X. AUXIN RESPONSE FACTOR3 Regulates Floral Meristem Determinacy by Repressing Cytokinin Biosynthesis and Signaling. Plant Cell. 2018, 30, 324–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.; Dai, X.; Zhao, Y. Auxin biosynthesis by the YUCCA flavin monooxygenases controls the formation of floral organs and vascular tissues in Arabidopsis. Genes Dev. 2006, 20, 1790–1799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majda, M.; Robert, S. The Role of Auxin in Cell Wall Expansion. Int J Mol Sci. 2018, 19, 951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roudier, F.; Gissot, L.; Beaudoin, F.; Haslam, R.; Michaelson, L.; Marion, J.; Molino, D.; Lima, A.; Bach, L.; Morin, H.; Tellier, F.; Palauqui, J.C.; Bellec, Y.; Renne, C.; Miquel, M.; Dacosta, M.; Vignard, J.; Rochat, C.; Markham, J.E.; Moreau, P. ; Napier, J; Faure, J. D. Very-long-chain fatty acids are involved in polar auxin transport and developmental patterning in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2010, 22, 364–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, T.; He, Y.; Niu, S.; Zhang, Y. A YABBY gene CRABS CLAW a (CRCa) negatively regulates flower and fruit sizes in tomato. Plant Sci. 2022, 320, 111285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, G.; Huang, J.; Lei, S.K.; Sun, X.G.; Li, X. Comparative gene expression profile analysis of ovules provides insights into Jatropha curcas L. ovule development. Sci Rep. 2019, 9, 15973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Q.; Niu, L.; Chen, M.S.; Tao, Y.B.; Wang, X.; He, H.; Pan, B.Z.; Xu, Z.F. De novo transcriptome assembly and comparative analysis between male and benzyladenine-induced female inflorescence buds of Plukenetia volubilis. J Plant Physiol. 2018, 221, 107–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, M.H.; Zhao, K.; Lv, J.H.; Huo, J.L.; Zhang, Z.Q.; Zhu, H.S.; Zou, X.X.; Wen, J.F. Flower transcriptome dynamics during nectary development in pepper (Capsicum annuum L.). Genet Mol Biol. 2020, 43, e20180267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katzer, A.M.; Wessinger, C.A.; Anaya, B.M.; Hileman, L.C. CRABS CLAW-independent floral nectary development in Penstemon barbatus. Am J Bot. 2025, 112, e70058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, J.; Li, P.; Li, M.; Zhu, D.; Ma, H.; Xu, H.; Li, S.; Wei, J.; Bian, X.; Wang, M.; Lai, Y.; Peng, Y.; Li, H.; Rahman, A.; Wu, S. Heat stress impairs floral meristem termination and fruit development by affecting the BR-SlCRCa cascade in tomato. Plant Commun. 2024, 5, 100790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bollier, N.; Sicard, A.; Leblond, J.; Latrasse, D.; Gonzalez, N.; Gévaudant, F.; Benhamed, M.; Raynaud, C.; Lenhard, M.; Chevalier, C.; Hernould, M.; Delmas, F. At-MINI ZINC FINGER2 and Sl-INHIBITOR OF MERISTEM ACTIVITY, a Conserved Missing Link in the Regulation of Floral Meristem Termination in Arabidopsis and Tomato. Plant Cell. 2018, 30, 83–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, Y.; Chen, B.; Qiao, L.; Chen, F.; Zhao, J.; Cheng, Z.; Weng, Y. Phenotypic Characterization and Fine Mapping of a Major-Effect Fruit Shape QTL FS5. 2 in Cucumber, Cucumis sativus L., with Near-Isogenic Line-Derived Segregating Populations. Int J Mol Sci. 2022, 23, 13384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morel, P.; Heijmans, K.; Ament, K.; Chopy, M.; Trehin, C.; Chambrier, P.; Rodrigues Bento, S.; Bimbo, A.; Vandenbussche, M. The Floral C-Lineage Genes Trigger Nectary Development in Petunia and Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2018, 30, 2020–2037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peréz-Mesa, P.; Ortíz-Ramírez, C.I.; González, F.; Ferrándiz, C.; Pabón-Mora, N. Expression of gynoecium patterning transcription factors in Aristolochia fimbriata (Aristolochiaceae) and their contribution to gynostemium development. Evodevo. 2020, 11, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, X.; Xie, W.; Chen, X.; Zhang, H.; Zhao, T.; Huang, J.; Zhang, R.; Li, X. Morphological and molecular mechanisms of floral nectary development in Chinese Jujube. BMC Plant Biol. 2024, 24, 1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Che, G.; Pan, Y.; Liu, X.; Li, M.; Zhao, J.; Yan, S.; He, Y.; Wang, Z.; Cheng, Z.; Song, W.; Zhou, Z.; Wu, T.; Weng, Y.; Zhang, X. Natural variation in CRABS CLAW contributes to fruit length divergence in cucumber. Plant Cell. 2023, 35, 738–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, L.; Li, C.; Duan, Y.; Qu, W.; Wang, H.; Miao, H.; Zhang, H. A SNP Mutation of SiCRC Regulates Seed Number Per Capsule and Capsule Length of cs1 Mutant in Sesame. Int J Mol Sci. 2019, 20, 4056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prunet, N.; Morel, P.; Thierry, A.M.; Eshed, Y.; Bowman, J.L.; Negrutiu, I.; Trehin, C. REBELOTE, SQUINT, and ULTRAPETALA1 function redundantly in the temporal regulation of floral meristem termination in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell. 2008, 20, 901–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.Y.; Baum, S.F.; Alvarez, J.; Patel, A.; Chitwood, D.H.; Bowman, J.L. Activation of CRABS CLAW in the Nectaries and Carpels of Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2005, 17, 25–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gross, T.; Becker, A. Transcription Factor Action Orchestrates the Complex Expression Pattern of CRABS CLAW in Arabidopsis. Genes (Basel). 2021, 12, 1663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kidokoro, S.; Konoura, I.; Soma, F.; Suzuki, T.; Miyakawa, T.; Tanokura, M.; Shinozaki, K.; Yamaguchi-Shinozaki, K. Clock-regulated coactivators selectively control gene expression in response to different temperature stress conditions in Arabidopsis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2023, 120, e2216183120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Z.J.; Yan, J.Y.; Li, G.X.; Wu, Z.C.; Zhang, S.Q.; Zheng, S.J. WRKY41 controls Arabidopsis seed dormancy via direct regulation of ABI3 transcript levels not downstream of ABA. Plant J. 2014, 79, 810–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfannebecker, K.C.; Lange, M.; Rupp, O.; Becker, A. Seed Plant-Specific Gene Lineages Involved in Carpel Development. Mol Biol Evol. 2017, 34, 925–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

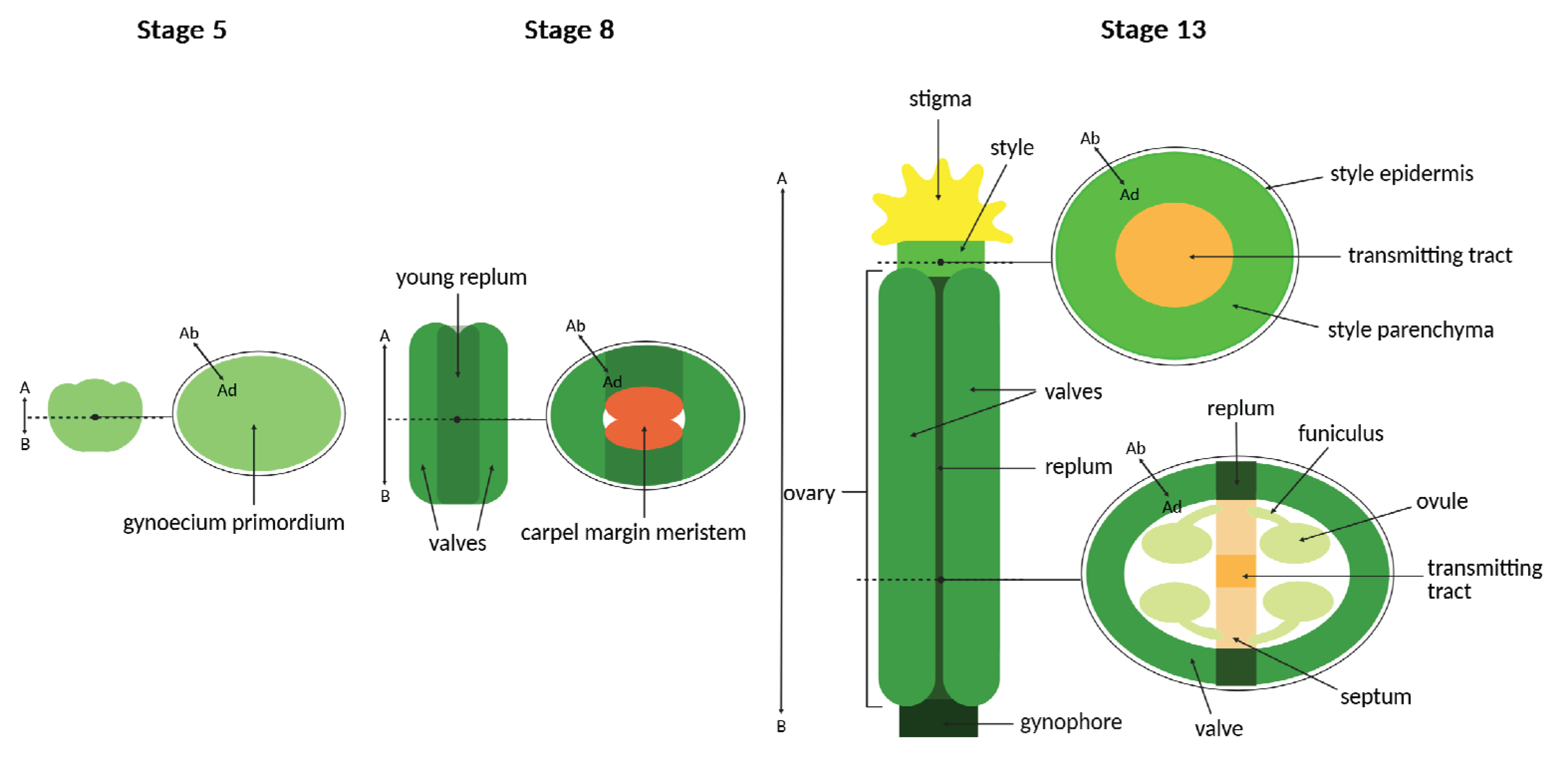

- Zúñiga-Mayo, V.M.; Gómez-Felipe, A.; Herrera-Ubaldo, H.; de Folter, S. Gynoecium development: networks in Arabidopsis and beyond. J Exp Bot. 2019, 70, 1447–1460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scutt, C.P.; Vinauger-Douard, M.; Fourquin, C.; Finet, C.; Dumas, C. An evolutionary perspective on the regulation of carpel development. J Exp Bot. 2006; 57, 2143–2152. [CrossRef]

- Yamada, T.; Yokota, S.; Hirayama, Y.; Imaichi, R.; Kato, M.; Gasser, C.S. Ancestral expression patterns and evolutionary diversification of YABBY genes in angiosperms. Plant J. 2011, 67, 26–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakayama, H.; Yamaguchi, T.; Tsukaya, H. Expression patterns of AaDL, a CRABS CLAW ortholog in Asparagus asparagoides (Asparagaceae), demonstrate a stepwise evolution of CRC/DL subfamily of YABBY genes. Am J Bot. 2010, 97, 591–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarez, J.; Smyth, D.R. CRABS CLAW and SPATULA, two Arabidopsis genes that control carpel development in parallel with AGAMOUS. Development. 1999, 126, 2377–2386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gross, T.; Broholm, S.; Becker, A. CRABS CLAW Acts as a Bifunctional Transcription Factor in Flower Development. Front Plant Sci. 2018, 9, 835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bobb, A.J.; Eiben, H.G.; Bustos, M.M. PvAlf, an embryo-specific acidic transcriptional activator enhances gene expression from phaseolin and phytohemagglutinin promoters. Plant J. 1995, 8, 331–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitchell, P.J.; Tjian, R. Transcriptional regulation in mammalian cells by sequence-specific DNA binding proteins. Science. 1989, 245, 371–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romanova, M.A.; Maksimova, A.I.; Pawlowski, K.; Voitsekhovskaja, O.V. YABBY Genes in the Development and Evolution of Land Plants. Int J Mol Sci. 2021, 22, 4139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Li, C.; Li, D.; Liu, Y.; Yang, X. Roles of YABBY transcription factors in the modulation of morphogenesis, development, and phytohormone and stress responses in plants. J Plant Res. 2020, 133, 751–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosugi, S.; Hasebe, M.; Matsumura, N.; Takashima, H.; Miyamoto-Sato, E.; Tomita, M.; Yanagawa, H. Six classes of nuclear localization signals specific to different binding grooves of importin alpha. J Biol Chem. 2009, 284, 478–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cross, E.M.; Akbari, N.; Ghassabian, H.; Hoad, M.; Pavan, S.; Ariawan, D.; Donnelly, C.M.; Lavezzo, E.; Petersen, G.F.; Forwood, J.K.; Alvisi, G. A functional and structural comparative analysis of large tumor antigens reveals evolution of different importin α-dependent nuclear localization signals. Protein Sci. 2024, 33, e4876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.W.; Couñago, R.M.; Williams, S.J.; Bodén, M.; Kobe, B. Distinctive conformation of minor site-specific nuclear localization signals bound to importin-α. Traffic. 2013, 14, 1144–1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strader, L.; Weijers, D.; Wagner, D. Plant transcription factors—Being in the right place with the right company. Curr. Op. Plant Biol. 2022, 65, 102136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amoutzias, G.D.; Robertson, D.L.; Van de Peer, Y.; Oliver, S.G. Choose your partners: Dimerization in eukaryotic transcription factors. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2008, 33, 220–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Wang, Y.; Yan, M.; Liu, C.; Yuan, Z. BELL1 interacts with CRABS CLAW and INNER NO OUTER to regulate ovule and seed development in pomegranate. Plant Physiol. 2023, 191, 1066–1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Boer, C.G.; Vaishnav, E.D.; Sadeh, R.; Abeyta, E.L.; Friedman, N.; Regev, A. Deciphering eukaryotic gene-regulatory logic with 100 million random promoters. Nat. Biotechnol. 2020, 38, 56–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Louphrasitthiphol, P.; Siddaway, R.; Loffreda, A.; Pogenberg, V.; Friedrichsen, H.; Schepsky, A.; Zeng, Z.; Lu, M.; Strub, T.; Freter, R.; et al. Tuning transcription factor availability through acetylation-mediated genomic redistribution. Mol. Cell 2020, 79, 472–487.e10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grau, J.; Schmidt, F.; Schulz, M.H. Widespread effects of DNA methylation and intra-motif dependencies revealed by novel transcription factor binding models. Nucleic Acids Res. 2023, 51, e95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahein, A.; López-Malo, M.; Istomin, I.; Olson, E.J.; Cheng, S.; Maerkl, S.J. Systematic analysis of low-affinity transcription factor binding site clusters in vitro and in vivo establishes their functional relevance. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 5273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fontana, M.; Roosjen, M.; Crespo García, I.; van den Berg, W.; Malfois, M.; Boer, R.; Weijers, D.; Hohlbein, J. Cooperative action of separate interaction domains promotes high-affinity DNA binding of Arabidopsis thaliana ARF transcription factors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2023, 120, e2219916120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, E.; Ito, T.; Sun, B. Control of floral stem cell activity in Arabidopsis. Plant Signal Behav. 2019;14(11):1659706. [CrossRef]

- Yadav, S.; Kumar, H.; Mahajan, M.; Sahu, S.K.; Singh, S.K.; Yadav, R.K. Local auxin biosynthesis promotes shoot patterning and stem cell differentiation in Arabidopsis shoot apex. Development. 2023, 150, dev202014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwaśniewska, K.; Breathnach, C.; Fitzsimons, C.; Goslin, K.; Thomson, B.; Beegan, J.; Finocchio, A.; Prunet, N.; Ó'Maoiléidigh, D.S.; Wellmer, F. Expression of KNUCKLES in the Stem Cell Domain Is Required for Its Function in the Control of Floral Meristem Activity in Arabidopsis. Front Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 704351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, L.; Cao, X.; Liu, Y.; Li, J.; Li, Y.; Li, D.; Zhang, K.; Gao, C.; Dong, A.; Liu, X. A chromatin loop represses WUSCHEL expression in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 2018, 94, 1083–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ÓMaoiléidigh, D.S.; Wuest, S.E.; Rae, L.; Raganelli, A.; Ryan, P.T.; Kwasniewska, K.; Das, P.; Lohan, A.J.; Loftus, B.; Graciet, E.; Wellmer, F. Control of reproductive floral organ identity specification in Arabidopsis by the C function regulator AGAMOUS. Plant Cell. 2013, 25, 2482–2503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Shpak, E.D.; Hong, T. A mathematical model for understanding synergistic regulations and paradoxical feedbacks in the shoot apical meristem. Comput Struct Biotechnol J. 2020, 18, 3877–3889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Liu, X.; Zhou, Y. Transcriptional circuits in control of shoot stem cell homeostasis. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2020, 53, 50–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daum, G.; Medzihradszky, A.; Suzaki, T.; Lohmann, J.U. A mechanistic framework for noncell autonomous stem cell induction in Arabidopsis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014, 111, 14619–14624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; DeGennaro, D.; Lin, G.; Chai, J.; Shpak, E.D. ERECTA family signaling constrains CLAVATA3 and WUSCHEL to the center of the shoot apical meristem. Development. 2021, 148, dev189753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, K.; Kao, L.; Cerbantez-Bueno, V.E.; Delgadillo, C.; Nguyen, D.; Ullah, S.; Delgadillo, C.; Reddy, G.V. HAIRY MERISTEM proteins regulate the WUSCHEL protein levels in mediating CLAVATA3 expression. Physiol Plant. 2024, 176, e14505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Y.H.; Zhou, C.; Li, Y.J.; Yu, Y. Tang, L. P, Zhang WJ, Yao WJ, Huang R, Laux T, Zhang XS. Integration of pluripotency pathways regulates stem cell maintenance in the Arabidopsis shoot meristem. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2020, 117, 22561–22571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, C.; Zhu, Y.; Cui, Y.; Cheng, K.; Liang, W.; Wei, Z.; Zhu, M.; Yin, H.; Zeng, L.; Xiao, Y.; Lv, M.; Yi, J.; Hou, S.; He, K.; Li, J.; Gou, X. A group of receptor kinases are essential for CLAVATA signalling to maintain stem cell homeostasis. Nat Plants. 2018, 4, 205–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- 72 Wang, Y.; Jiao, Y. Cell signaling in the shoot apical meristem. Plant Physiol. 2023, 193, 70–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clark, S.E.; Running, M. P, Meyerowitz EM. CLAVATA1, a regulator of meristem and flower development in Arabidopsis. Development. 1993, 119, 397–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clark, S.E.; Running, M.P.; Meyerowitz, E.M. CLAVATA3 is a specific regulator of shoot and floral meristem development affecting the same processes as CLAVATA1. Development. 1995, 121: 2057–2067.

- Schoof, H.; Lenhard, M.; Haecker, A.; Mayer, K.F.; Jürgens, G.; Laux, T. The stem cell population of Arabidopsis shoot meristems in maintained by a regulatory loop between the CLAVATA and WUSCHEL genes. Cell. 2000, 100, 635–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brand, U.; Fletcher, J.C.; Hobe, M.; Meyerowitz, E.M.; Simon, R. Dependence of stem cell fate in Arabidopsis on a feedback loop regulated by CLV3 activity. Science. 2000, 289, 617–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schlegel, J.; Denay, G.; Wink, R.; Pinto, K.G.; Stahl, Y.; Schmid, J.; Blümke, P.; Simon, R.G. Control of Arabidopsis shoot stem cell homeostasis by two antagonistic CLE peptide signalling pathways. Elife. 2021, 10, 70934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenhard, M.; Jürgens, G.; Laux, T. The WUSCHEL and SHOOTMERISTEMLESS genes fulfil complementary roles in Arabidopsis shoot meristem regulation. Development. 2002, 129, 3195–3206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Causier, B.; Ashworth, M.; Guo, W.; Davies, B. The TOPLESS interactome: a framework for gene repression in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2012, 158, 423–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kagale, S.; Rozwadowski, K. EAR motif-mediated transcriptional repression in plants: an underlying mechanism for epigenetic regulation of gene expression. Epigenetics. 2011, 6, 141–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenhard, M.; Bohnert, A.; Jürgens, G.; Laux, T. Termination of stem cell maintenance in Arabidopsis floral meristems by interactions between WUSCHEL and AGAMOUS. Cell. 2001, 105, 805–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sieburth, L.E.; Running, M.P.; Meyerowitz, E.M. Genetic separation of third and fourth whorl functions of AGAMOUS. Plant Cell. 1995, 7, 1249–1258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lohmann, J.U.; Hong, R.L.; Hobe, M.; Busch, M.A.; Parcy, F.; Simon, R.; Weigel, D. A molecular link between stem cell regulation and floral patterning in Arabidopsis. Cell. 2001, 105, 793–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Kim, Y.J.; Müller, R.; Yumul, R.E.; Liu, C.; Pan, Y.; Cao, X.; Goodrich, J.; Chen, X. AGAMOUS terminates floral stem cell maintenance in Arabidopsis by directly repressing WUSCHEL through recruitment of Polycomb Group proteins. Plant Cell. 2011, 23, 3654–3670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, B.; Xu, Y.; Ng, K.H.; Ito, T. A timing mechanism for stem cell maintenance and differentiation in the Arabidopsis floral meristem. Genes Dev. 2009, 23, 1791–1804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, S.; Liu, X.; Zhou, C.; Zhou, Q.; Zhao, Y.; Li, G.; Zhou, D.X. Cooperation between the H3K27me3 Chromatin Mark and Non-CG Methylation in Epigenetic Regulation. Plant Physiol. 2016, 172, 1131–1141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gómez-Mena, C.; de Folter, S.; Costa, M.M.; Angenent, G.C.; Sablowski, R. Transcriptional program controlled by the floral homeotic gene AGAMOUS during early organogenesis. Development. 2005, 132, 429–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Engelhorn, J.; Moreau, F.; Fletcher, J.C.; Carles, C.C. ULTRAPETALA1 and LEAFY pathways function independently in specifying identity and determinacy at the Arabidopsis floral meristem. Ann Bot. 2014, 114, 1497–1505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carles, C.C.; Choffnes-Inada, D.; Reville, K.; Lertpiriyapong, K.; Fletcher, J.C. ULTRAPETALA1 encodes a SAND domain putative transcriptional regulator that controls shoot and floral meristem activity in Arabidopsis. Development. 2005, 132, 897–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uemura, A.; Yamaguchi, N.; Xu, Y.; Wee, W.; Ichihashi, Y.; Suzuki, T.; Shibata, A.; Shirasu, K.; Ito, T. Regulation of floral meristem activity through the interaction of AGAMOUS, SUPERMAN, and CLAVATA3 in Arabidopsis. Plant Reprod. 2018, 31, 89–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Prunet, N.; Gan, E.S.; Wang, Y.; Stewart, D.; Wellmer, F.; Huang, J.; Yamaguchi, N.; Tatsumi, Y.; Kojima, M.; Kiba, T.; Sakakibara, H.; Jack, T.P.; Meyerowitz, E.M.; Ito, T. SUPERMAN regulates floral whorl boundaries through control of auxin biosynthesis. EMBO J. 2018, 37, e97499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakai, H. ; Krizek, B,A. ; Jacobsen, S.E.; Meyerowitz, E.M. Regulation of SUP expression identifies multiple regulators involved in arabidopsis floral meristem development. Plant Cell. 2000, 12, 1607–1618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelayo, M.A.; Yamaguchi, N.; Ito, T. One factor, many systems: the floral homeotic protein AGAMOUS and its epigenetic regulatory mechanisms. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2021, 61, 102009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zúñiga-Mayo, V.M.; Reyes-Olalde, J.I.; Marsch-Martinez, N.; de Folter, S. Cytokinin treatments affect the apical-basal patterning of the Arabidopsis gynoecium and resemble the effects of polar auxin transport inhibition. Front Plant Sci. 2014, 5, 191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerbantez-Bueno, V.E.; Zúñiga-Mayo, V.M.; Reyes-Olalde, J.I.; Lozano-Sotomayor, P.; Herrera-Ubaldo, H.; Marsch-Martinez, N.; de Folter, S. Redundant and Non-redundant Functions of the AHK Cytokinin Receptors During Gynoecium Development. Front Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 568277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, N.; Zhu, H.; Li, F.; Wang, M.; Tian, Z.; Wei, J.; Zhang, Z. Genome-wide identification of YABBY genes and functional characterization of CRABS CLAW (AktCRC) in flower development of Akebia trifoliata. Int J Biol Macromol. 2025, 311, 143892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Wu, Z.; Sun, B. KNUCKLES regulates floral meristem termination by controlling auxin distribution and cytokinin activity. Plant Cell. 2024, 37, koae312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hawar, A.; Chen, W.; Zhu, T.; Wang, X.; Liu, J.; Xiong, S.; Ito, T.; Chen, D.; Sun, B. The histone acetyltransferase GCN5 regulates floral meristem activity and flower development in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2025, 37, koaf135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, X.; Yang, H.; Shang, C.; Ma, S.; Liu, L.; Cheng, J. The Roles of Auxin Biosynthesis YUCCA Gene Family in Plants. Int J Mol Sci. 2019, 20, 6343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carabelli, M.; Turchi, L.; Morelli, G.; Østergaard, L.; Ruberti, I.; Moubayidin, L. Coordination of biradial-to-radial symmetry and tissue polarity by HD-ZIP II proteins. Nat Commun. 2021, 12, 4321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, X.; Yin, L.; Xue, H. Co-expression analysis identifies CRC and AP1 the regulator of Arabidopsis fatty acid biosynthesis. J Integr Plant Biol. 2012, 54, 486–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Zhang, A.; Liu, C.; Saeed, M.; Li, J.; Wu, Y.; Wu, Y.; Gu, H.; Yuan, J.; Wang, B.; Li, P.; Fang, H. A Comprehensive Analysis In Silico of KCS Genes in Maize Revealed Their Potential Role in Response to Abiotic Stress. Plants (Basel). 2024, 13, 3507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takasugi, T.; Ito, Y. Altered expression of auxin-related genes in the fatty acid elongase mutant oni1 of rice. Plant Signal Behav. 2011, 6, 887–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyes-Olalde, J.I.; Zúñiga-Mayo, V.M.; Serwatowska, J.; Chavez Montes, R.A.; Lozano-Sotomayor, P.; Herrera-Ubaldo, H.; Gonzalez-Aguilera, K.L.; Ballester, P.; Ripoll, J.J.; Ezquer, I.; Paolo, D.; Heyl, A.; Colombo, L.; Yanofsky, M.F.; Ferrandiz, C.; Marsch-Martínez, N.; de Folter, S. The bHLH transcription factor SPATULA enables cytokinin signaling, and both activate auxin biosynthesis and transport genes at the medial domain of the gynoecium. PLoS Genet. 2017, 13, e1006726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jamil, I.; Giri, A.; Moubayidin, L. Organ symmetry establishment during gynoecium development. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2025, 85, 102732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eshed, Y.; Baum, S.F.; Bowman, J.L. Distinct mechanisms promote polarity establishment in carpels of Arabidopsis. Cell. 1999, 99, 199–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azhakanandam, S.; Nole-Wilson, S.; Bao, F.; Franks, R.G. SEUSS and AINTEGUMENTA mediate patterning and ovule initiation during gynoecium medial domain development. Plant Physiol. 2008, 146, 1165–1181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zúñiga-Mayo, V.M.; Marsch-Martínez, N.; de Folter, S. JAIBA, a class-II HD-ZIP transcription factor involved in the regulation of meristematic activity, and important for correct gynoecium and fruit development in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 2012, 71, 314–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zúñiga-Mayo, V.M.; Marsch-Martínez, N.; de Folter, S. The class II HD-ZIP JAIBA gene is involved in meristematic activity and important for gynoecium and fruit development in Arabidopsis. Plant Signal Behav. 2012, 11, 1501–1503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuusk, S.; Sohlberg, J.J.; Long, J.A.; Fridborg, I.; Sundberg, E. STY1 and STY2 promote the formation of apical tissues during Arabidopsis gynoecium development. Development. 2002, 129, 4707–4717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohlberg, J.J.; Myrenås, M.; Kuusk, S.; Lagercrantz, U.; Kowalczyk, M.; Sandberg, G.; Sundberg, E. STY1 regulates auxin homeostasis and affects apical-basal patterning of the Arabidopsis gynoecium. Plant J. 2006, 47, 112–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowman, J.L.; Sakai, H.; Jack, T.; Weigel, D.; Mayer, U.; Meyerowitz, E.M. SUPERMAN, a regulator of floral homeotic genes in Arabidopsis. Development. 1992, 114, 599–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfannebecker, K.C.; Lange, M.; Rupp, O.; Becker, A. An Evolutionary Framework for Carpel Developmental Control Genes. Mol Biol Evol. 2017, 34, 330–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dreni, L.; Kater, M.M. MADS reloaded: evolution of the AGAMOUS subfamily genes. New Phytol. 2014, 201, 717–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phukela, B.; Geeta, R.; Das, S.; Tandon, R. Ancestral segmental duplication in Solanaceae is responsible for the origin of CRCa-CRCb paralogues in the family. Mol Genet Genomics. 2020, 295, 563–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fourquin, C.; Primo, A.; Martínez-Fernández, I.; Huet-Trujillo, E.; Ferrándiz, C. The CRC orthologue from Pisum sativum shows conserved functions in carpel morphogenesis and vascular development. Ann Bot. 2014, 114, 1535–1544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ishikawa, M.; Ohmori, Y.; Tanaka, W.; Hirabayashi, C.; Murai, K.; Ogihara, Y.; Yamaguchi, T.; Hirano, H.Y. The spatial expression patterns of DROOPING LEAF orthologs suggest a conserved function in grasses. Genes Genet Syst. 2009, 84, 137–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fourquin, C.; Vinauger-Douard, M.; Fogliani, B.; Dumas, C.; Scutt, C.P. Evidence that CRABS CLAW and TOUSLED have conserved their roles in carpel development since the ancestor of the extant angiosperms. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005, 102, 4649–4654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fourquin, C.; Vinauger-Douard, M.; Chambrier, P.; Berne-Dedieu, A.; Scutt, C.P. Functional conservation between CRABS CLAW orthologues from widely diverged angiosperms. Ann Bot. 2007, 100, 651–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.Y.; Baum, S.F.; Oh, S.H.; Jiang, C.Z.; Chen, J.C.; Bowman, J.L. Recruitment of CRABS CLAW to promote nectary development within the eudicot clade. Development. 2005, 132, 5021–5032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Endress, P.K. The flowers in extant basal angiosperms and inferences on ancestral flowers. Int. J. Plant Sci. 2001, 162, 1111–1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.Y.; Hsiao, Y.Y.; Li, C.I.; Yeh, C.M.; Mitsuda, N.; Yang, H.X.; Chiu, C.C.; Chang, S.B.; Liu, Z.J.; Tsai, W.C. The ancestral duplicated DL/CRC orthologs, PeDL1 and PeDL2, function in orchid reproductive organ innovation. J Exp Bot. 2021, 72, 5442–5461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, P.; Song, C.; Liu, H.; Li, P.; Zhang, M.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, S.; He, C. Physalis floridana CRABS CLAW mediates neofunctionalization of GLOBOSA genes in carpel development. J Exp Bot. 2021, 72, 6882–6903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, P.; Gao, J.; Shen, W.; Wu, Z.; Dai, C.; Wen, J.; Yi, B.; Ma, C.; Shen, J.; Fu, T.; Tu, J. BnaCRCs with domestication preference positively correlate with the seed-setting rate of canola. Plant J. 2022, 111, 1717–1731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Nolan, T.M.; Yin, Y.; Bassham, D.C. Identification of transcription factors that regulate ATG8 expression and autophagy in Arabidopsis. Autophagy. 2020, 16, 123–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shivhare, D.; Musialak-Lange, M.; Julca, I.; Gluza, P.; Mutwil, M. Removing auto-activators from yeast-two-hybrid assays by conditional negative selection. Sci Rep. 2021, 11, 5477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strickler, S.R.; Bombarely, A.; Mueller, L.A. Designing a transcriptome next-generation sequencing project for a nonmodel plant species. Am J Bot. 2012, 99, 257–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klepikova, A.V.; Penin, A.A. Gene Expression Maps in Plants: Current State and Prospects. Plants (Basel). 2019, 8, 309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, M.; Qian, Q.; Lu, M.; Chen, M.; Fan, Z.; Shang, Y.; Bu, C.; Du, Z.; Song, S.; Zeng, J.; Xiao, J. PlantPan: A comprehensive multi-species plant pan-genome database. Plant J. 2025, 122, e70144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elmore, J.M.; Velásquez-Zapata, V.; Wise, R.P. Next-Generation Yeast Two-Hybrid Screening to Discover Protein-Protein Interactions. Methods Mol Biol. 2023, 2690, 205–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velásquez-Zapata, V.; Elmore, J.M.; Banerjee, S.; Dorman, K.S.; Wise, R.P. Next-generation yeast-two-hybrid analysis with Y2H-SCORES identifies novel interactors of the MLA immune receptor. PLoS Comput Biol. 2021, 17, e1008890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jingwen, W.; Jingxin, W.; Ye, Z.; Yan, Z.; Caozhi, L.; Yanyu, C.; Fanli, Z.; Su, C.; Yucheng, W. Building an improved transcription factor-centered yeast one hybrid system to identify DNA motifs bound by protein comprehensively. BMC Plant Biol. 2023, 23, 236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).