1. Introduction

Recent advances in single-nucleus RNA sequencing (snRNA-seq) have significantly enhanced our understanding of cellular diversity in the spinal cord. This technology enables high-resolution profiling of gene expression at the level of individual nuclei circumventing limitations associated with dissociation and allowing access to fragile cell types. These features make snRNA-seq particularly valuable for studying central nervous system (CNS) tissues.

One of the most comprehensive efforts to date was conducted by Russ

et al. (2022), who generated an integrated reference atlas of the mouse spinal cord by harmonizing data across multiple studies, developmental stages, and anatomical regions. Notably, they introduced SeqSeek (

https://seqseek.ninds.nih.gov/), an open-access platform that allows researchers to compare and classify transcriptomic profiles against a standardized reference. Subsequent studies by Matson

et al. (2022), Kathe

et al. (2022), and Squair et al. (2021, 2023) focused on the lower thoracic- lumbar segments, applying snRNA-seq to characterize cellular responses to traumatic injury, rehabilitation, and epidural electrical stimulation. These efforts revealed both conserved and injury-induced transcriptional states, particularly in excitatory and inhibitory interneurons, and highlighted the complexity of spinal cell types under different physiological and pathological contexts. More recently, Skinnider

et al. (2024) employed single-nucleus and spatial transcriptomics to examine lesion-associated heterogeneity in the spinal cord. Their findings demonstrated context-dependent shifts in cellular composition and gene expression, underscoring the dynamic and region-specific architecture of spinal tissue. Notably, they leveraged all obtained data into

Tabulae Paralytica (

http://tabulaeparalytica.com/), a web-based platform that provides interactive insights into the gene expression changes following spinal cord injury.

Together, these studies provide a robust foundation for transcriptomic mapping of the spinal cord. However, the high cost of snRNA-seq has constrained previous studies to analyzing data from restricted numbers of individuals (typically fewer than four replicates per condition). Russ et al. (2022) demonstrated the feasibility of data integration across studies, successfully combining samples from different ages, regions, and sequencing technologies. Building on this foundation, the availability of various publicly accessible snRNA-seq datasets now enables a unified analysis of over 80,000 nuclei from 19 individuals, specifically targeting the adult low-thoracic lumbar spinal cord–a region critical for locomotion, proprioception, and lower-body reflexes. This level of coverage offers a unique opportunity to construct a region-specific atlas with greater depth and statistical power.

Additionally, the 2021 update to the mouse genome (GRCm39) supposed an increase from nearly 50,000 genes of GRCm38 to 56,884 in the new version, with their associated annotations, including more than 35,000 non-coding genes (ncRNAs) from nearly 22,000. While most existing atlases focus on protein-coding genes, the mammalian genome is predominantly transcribed into ncRNAs–including long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs), antisense RNAs, and pseudogenes–that regulate diverse biological processes. In the CNS, ncRNAs are implicated in neural development, synaptic plasticity, cell-type specification, and injury response (Wang et al., 2022). Although numerous studies have reported differential ncRNA expression following injury or in neurodegenerative models, their role in defining cell identity under baseline conditions remains largely unexplored.

Incorporating ncRNAs into a physiological grounded, integrative atlas of the adult lumbar spinal cord thus presents a novel opportunity to uncover previously overlooked layers of transcriptional regulation. Unlike conventional atlases, our approach captures the full transcriptomic landscape by analyzing coding-only, non-coding-only, and combined gene sets, allowing us to assess the distinct contributions of ncRNAs to cell-type discrimination and clustering resolution.

Here, we present an integrated snRNA-seq atlas of the adult lumbar-low thoracic spinal cord, based on harmonized data from six studies. We developed a unified computational pipeline for quality control, doublet removal, normalization, batch correction, dimensionality reduction, clustering, and multimodal annotation. By explicitly incorporating non-coding gene expression into our analysis, we evaluate whether ncRNAs carry biologically meaningful signatures that refine our understanding of spinal cord cell types and functional organization.

Our results provide compelling evidence that non-coding RNAs contribute robust, subtype-specific signals that are not redundant with protein-coding profiles. In particular, certain ncRNAs display restricted expression in inhibitory, sensory, or neuropeptidergic populations, suggesting that they may act as lineage markers or regulatory switches. Moreover, by integrating codifying and non-codifying transcriptomes, we achieve enhanced resolution in neuronal subclusterization, improving the discrimination of functionally distinct subtypes.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Selection and Preprocessing

To construct a single-nucleus transcriptomic atlas of the adult mouse lumbar spinal cord under physiological conditions, we curated snRNA-seq datasets available until 2024 meeting these criteria: (1) origin from low thoracic-lumbar spinal cord, (2) healthy, adult, non-injured mice, (3) availability of raw FASTQ or processed count matrices, and (4) use of 10X Genomics Chromium technology without FACS/FANS.

Supplementary Table S1 summarizes sequencing depth, platforms, and metadata.

Each sample was processed independently to accommodate dataset-specific characteristics. Sequencing quality of concatenated runs of each sample downloaded from SRA was assessed using FastQC (v0.12.1) (Andrews, 2010). Demultiplexing and alignment were carried out with STARsolo (v2.4.1) (Dobin

et al., 2013; Kaminow

et al., 2024) using the Cumulus workflow (

https://cumulus.readthedocs.io/en/latest/starsolo.html) on TERRA Platform (

https://app.terra.bio/). All samples were aligned to the same genomic reference built using GRCm39 mouse genome assembly and the GeneCode basic CHR gene annotation M33 (

https://www.gencodegenes.org/mouse/release_M33.html). Ambient RNA contamination and empty droplets were addressed with CellBender (v0.3.0) (Fleming

et al., 2023) on TERRA platform (

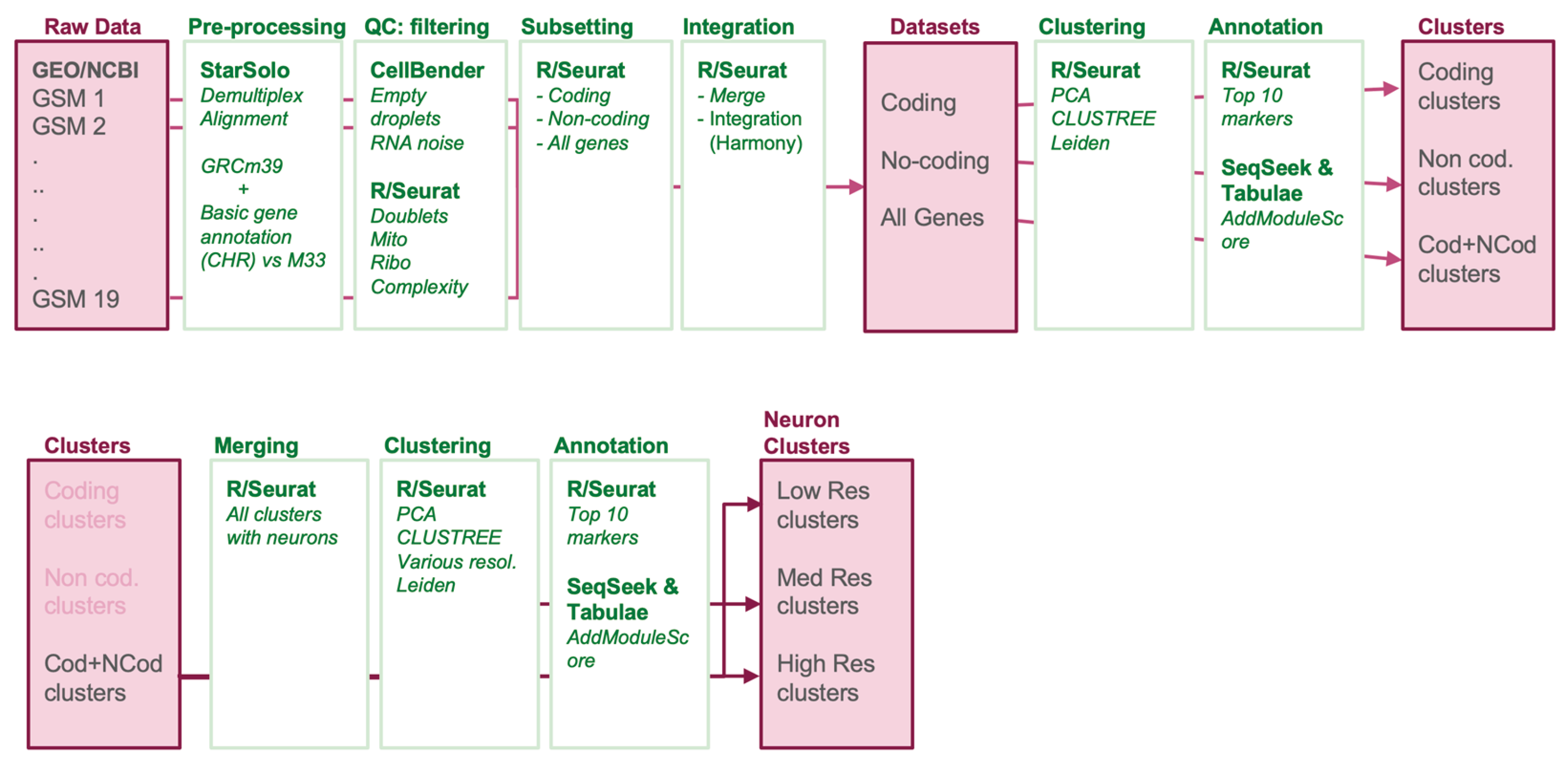

Figure 1).

2.2. Quality Control and Cell Filtering

Count matrices (in H5 format) were imported into the R (R Core Team, 2024) package Seurat v5.3.0 (Hao et al., 2024) for quality control (QC). Cells with ≥200 detected genes and genes present in ≥3 cells were retained. QC was performed independently per sample. Mitochondrial/ribosomal content and log10-transformed genes per unique molecular identifier (UMI) were used to identify potential multiplets or low-quality nuclei. Sample sex was determined when possible (only Russ et al., (2022) reported it specifically). Doublets were detected using scDBlFinder (v1.13.4) (Germain et al., 2022) with 10 stochastic runs per sample; only consistently flagged doublets were removed. Cell cycle phase scores (S and G2M) were estimated using Seurat’s CellCycleScoring function and regressed out during data scaling to reduce confounding effects. The effectiveness of quality controls was confirmed by visual inspection of Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection (UMAP) embeddings.

2.3. Gene Set Definition: Coding, Non-Coding, and Combined

Filtered samples were merged into a unified dataset. Before subsequent analyses, three datasets were identified based on the information of Gene biotypes:

Combined (ALL): Dataset with all transcripts included in the M33 annotation of the genome;

Coding genes (CG): a subset of the transcripts annotated as “protein_coding”;

Non-coding genes (NCG): a subset of the transcripts annotated as “lncRNAs”, “antisense”, “pseudogenes”, “TECs”, and “non-coding isoforms”.

2.4. Normalization and Integration

Normalization was performed using Seurat’s LogNormalize (v4.3.0), followed by HVG selection using the ‘vst’ method. Dimensionality reduction was performed with principal component analysis (PCA). Harmony integration (RunHarmony, 50 PCs) was applied to align datasets while preserving local structure (Korsunsky et al., 2019). Harmony was selected for its performance and scalability in single-nucleus analyses.

2.5. Clustering

To comprehensively resolve the cellular diversity of the adult mouse spinal cord, we implemented a two-step clustering strategy:

i) Coarse clustering of major spinal cord cell types. To define the major cellular compartments of the mouse spinal cord, we performed low-resolution clustering on the three datasets: CG, NCG, and ALL. For each subset, the top 30 Harmony-corrected principal components, selected based on visual inspection of the ElbowPlot, were used to construct a k-nearest neighbor (k-NN) graph with k=20. Clustering was then performed using the Leiden algorithm with Seurat’s default implementation (Traag, Waltman, & van Eck, 2019). To ensure comparability across datasets, we explored clustering at multiple resolutions using Clustree (Zappia & Oshlack, 2018) and selected the resolution that produced a consistent number of clusters across all subsets: 11 clusters each for the ALL (resolution = 0.07), CG (resolution = 0.07), and NCG (resolution = 0.2) datasets.

ii) Harmonized subclustering of neuronal populations. To further resolve the transcriptional diversity of spinal neurons, we performed a dedicated subclustering analysis starting from the coarse-level clusters obtained in the initial integration. Instead of extracting neuronal cells from the original count matrices, as done by Russ et al. (2022), we applied multiple rounds of hierarchical clustering directly on the fully integrated atlas, following the approach proposed by Skinnider et al. (2024). This strategy involves performing successive clustering at increasingly fine resolutions, enabling the identification of both major cell types and more granular neuronal subtypes.

2.6. Cell Type Annotation

Annotation combined manual and automated approaches. Marker genes (via FindAllMarkers) were cross-referenced with SeqSeek, Tabulae Paralytica, and literature. AddModuleScore was used to compute cell type-specific gene program scores using Russ et al. (2022) marker sets. Automated annotation was performed using SingleR (Aran et al., 2019) with the Tabulae Paralytica reference.

2.7. Compositional Analysis

Number of cells per cluster was compared among studies, sexes, and chemistries using scCODA (Büttner et al., 2021) to identify potential effects. The scCODA framework models cell type counts while considering negative correlative bias via joint modeling of all measured cell type proportions. Each factor (Chemistry, Study, and Sex) was defined as a covariate and analyzed independently. We set the reference cell type to be automatically identified by the model. The script and all outputs for each dataset are available at OSF.

2.8. Data Analysis

Comparisons among groups were carried out using t-test, ANOVA or Kruskal-Wallis test for non-parametric data. In comparing annotations, we used Simpson and Shannon diversity indexes (DeJong, 1975) to quantify the dispersion of populations among clusters. Data is expressed as mean ± standard deviation unless specified. Statistical analyses were carried out using R or JASP (JASP Team, 2024).

Scripts and detailed procedures are provided in Supplementary Methods and at

https://osf.io/dbgxt/. Editing support was provided by the Scientific Writing Assistant (OpenAI, 2025).

3. Results

3.1. Quality Control

19 samples of naïve, wildtype, adult mouse low thoracic-lumbar spinal cords from six studies were identified (

Table 1). All samples were originally processed with 10X Genomics and the sequencing data and associated metadata are available at the NCBI’s GEO and SRA repositories (see also Supplementary Data). Inspection of sequencing data with FastQC platform did not reveal any relevant quality issue (each sample report is available at OSF:

https://osf.io/dbgxt/). The three samples from the GSE165003 study (Squair et al., 2021) were excluded from the analysis because they were equal to samples in the GSE184370 study. All other samples were demultiplexed and aligned to the mouse genome assembly (GRCm39) and the full annotation M33 (basic annotation (CRH) M33) covering 21,403 coding genes and 35,481 non-coding genes and pseudogenes.

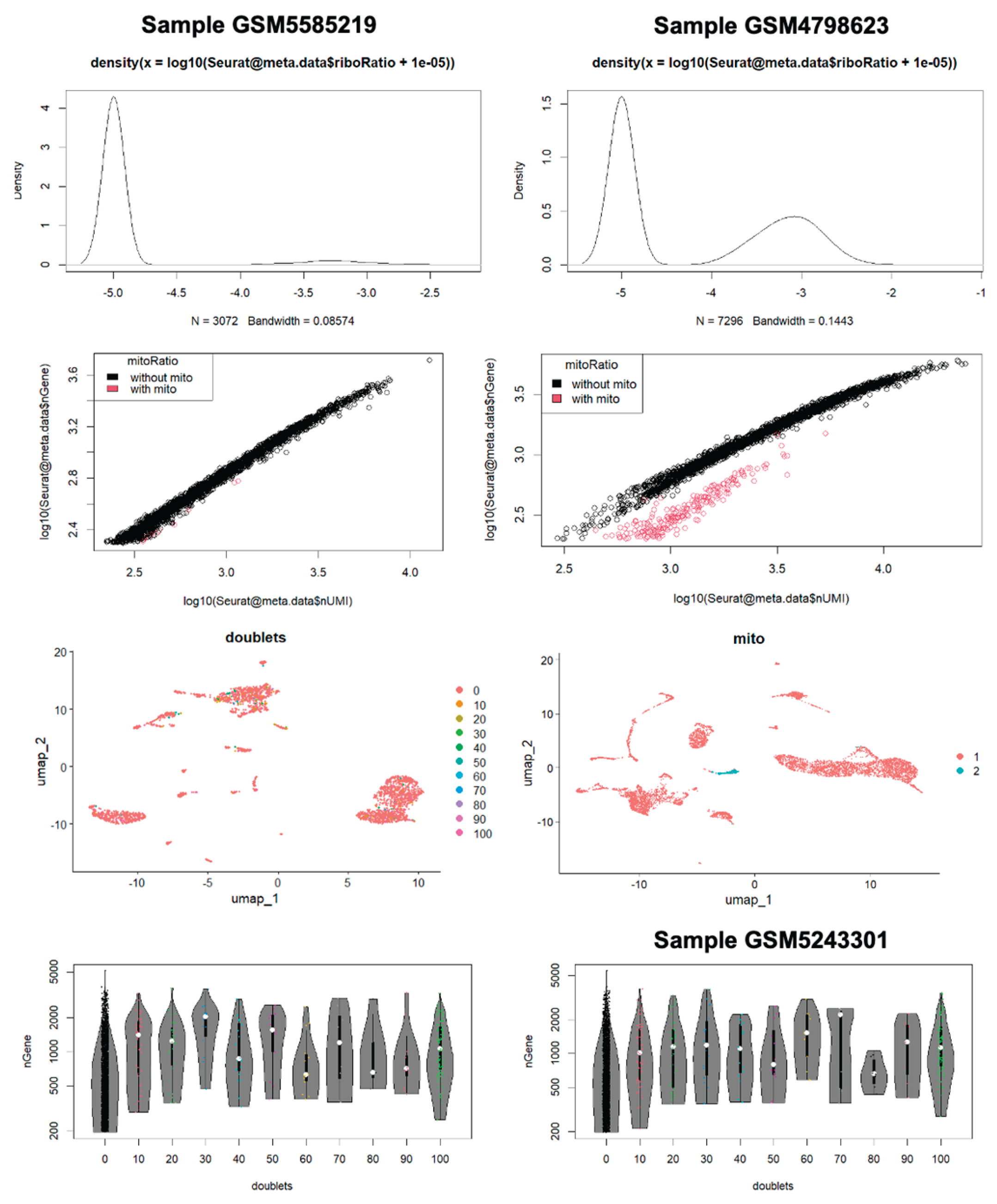

The resulting count matrices for each sample were subjected to quality controls to exclude background signal noise, empty droplets, cell doublets and compromised cells using CellBender and various functions from Seurat (

Figure 2). In general, all samples consisted predominantly of high-quality cells, with doublets accounting for 3–8% of the events (10–14% in Matson et al., 2022). In the Russ et al. (2022) dataset, three of the four samples (GSM4798623, GSM4798624 and GSM4798626) displayed a defined cluster of cells with high mitochondrial content and low complexity. These clusters comprised 147, 223 and 99 cells, respectively. By contrast, the remaining sample did not show a clear cluster, retaining only residual proportions of cells with these features. In Squair et al. (2023) dataset, sample GSM5961591 exhibited a cluster of 206 cells with high mitochondrial content. In Skinnider et al. (2024), all three samples contained very few cells with low complexity and high ribosomal content. In addition, two of them (GSM7474501 and GSM7474503) showed small clusters with high mitochondrial content, comprising 142 and 64 cells, respectively. Following QC assessment, anomalous cells were discarded –including removal of cells expressing fewer than 200 genes and genes detected in fewer than three cells–.

3.2. Clustering of Spinal Cell Types

The filtered nuclei from each sample were merged and integrated into three different datasets containing all transcriptomics information (ALL), or subsets with only information on coding (CG) or non-coding genes (NCG). The three datasets were processed independently to obtain a coarse clusterization of the cells for each type of data. The number of nuclei included remained the same in the three datasets (86,378). Median gene counts per nucleus were highest in the combined dataset (1,574.6), followed by coding (1,430.2) and non-coding (144.2).

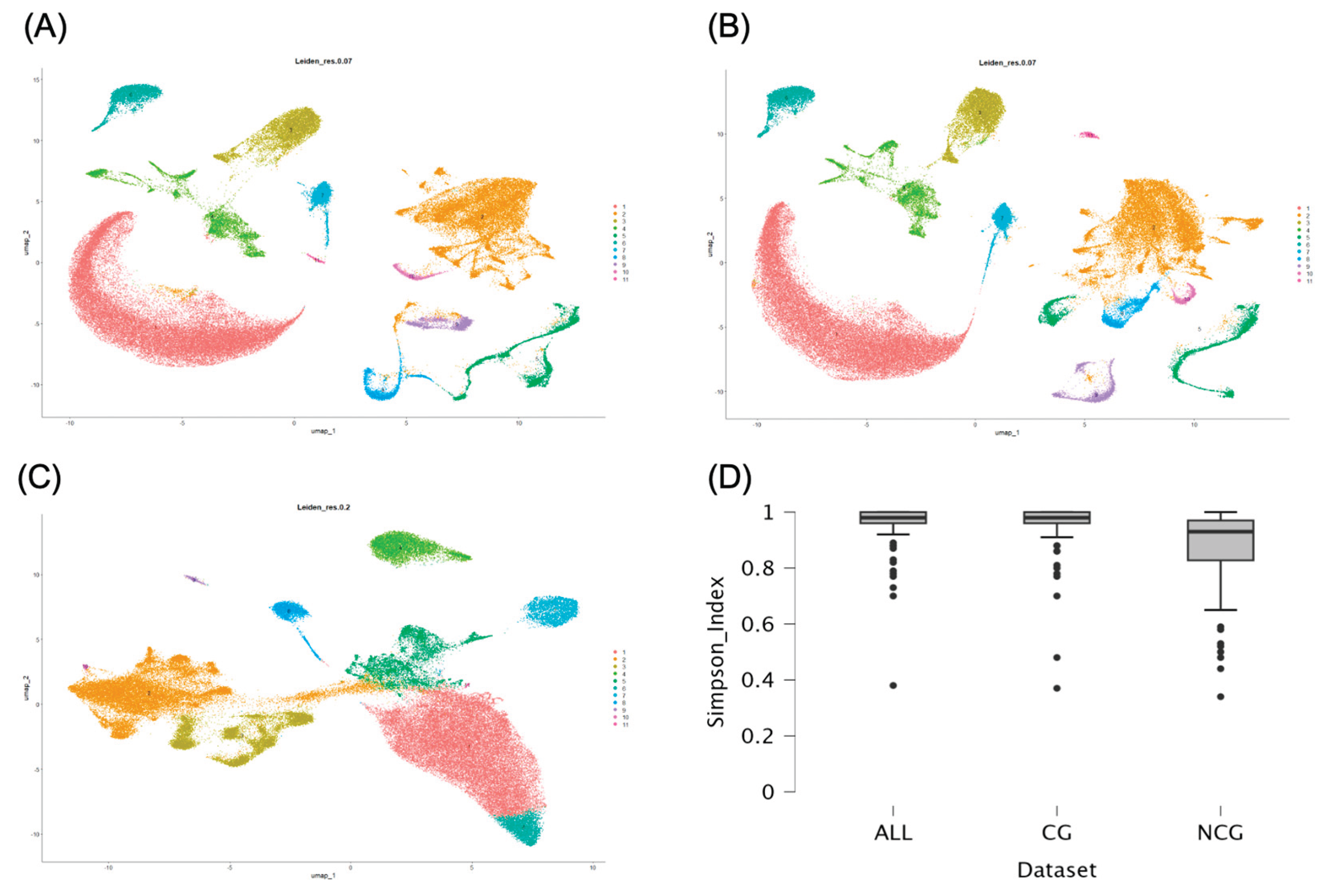

We employed the Leiden clustering method on 30 PCA components from each subset to identify coarse clusters segregating the main spine cell types. According to Clustree (see

Supplementary Figure S1). NCG dataset showed lower cluster resolution than CG and ALL datasets, therefore, we employed 0.07 resolution for CG and ALL datasets and 0.2 for NCG dataset to cluster the cells into 11 groups in the three datasets (

Figure 3).

3.3. Annotation of Major Clusters

To assign cell types to each identified cluster we employed the automated annotations obtained using SingleR with

Tabulae Paralytica reference atlas and AddModuleScore with the SeqSeek cell markers.

Tabulae annotation classified all cells in the dataset among 92 cell populations whereas in SeqSeek annotation the number of potential populations was reduced to 81. Inspection of the distribution of these populations in the clusters identified here revealed that most populations identified according to

Tabulae annotations were restricted to one cluster (ALL dataset, Simpson diversity index=0.96; Shannon index=0.10) whereas the populations identified using SeqSeek annotation were more evenly distributed among clusters (ALL dataset, Simpson diversity index=0.58; Shannon index=0.84; both p<0.01 relative to

Tabulae values;

Figure 3D). These disparities likely result from differences in the

Tabulae Paralytica or SeqSeek references and not to the annotation method because we observed similar mixed clusters in a follow up analysis using SingleR with SeqSeek reference. Therefore, for the current set of cells we considered that

Tabulae Paralytica + SingleR annotation outperformed the SeqSeek annotation and was selected for the following analyses.

3.4. Comparison of Clusterings Among ALL, CG, and NCG Datasets

According to the annotation from

Tabulae Paralytica, the 11 clusters obtained from each of the three datasets consistently corresponded to the major spinal cord cell lineages with some interesting differences. Both the complete (ALL) and the protein coding (CG) datasets yielded the same clusters (

Table 2), namely, one cluster of mature and differentiating oligodendrocytes and one cluster of oligodendrocyte precursor cells (OPCs), one cluster of astrocytes, one cluster of vascular cells, one cluster of microglia and other immune cells, one cluster of ependymal cells, and five clusters of neurons. Neuronal clustering at this coarse level separated three clusters of different dorsal horn excitatory neurons, one cluster of dorsal horn inhibitory neurons expressing galanin neuropeptide (DI_Gal in

Tabulae Paralytica terms), and a large cluster containing all other types of neurons, including a few populations of dorsal horn excitatory neurons, most dorsal horn inhibitory neurons, and all ventral neurons, including motoneurons (

Table 2).

Non-coding information gave rise to a clustering pattern that in broad terms and in some clusters such as those of astrocytes and ependymal cells is highly coherent with the ALL and CG patterns. However, the clustering of NCG dataset yields three oligodendrocyte clusters, two of mature and differentiating cells and one of OPCs. This supposed the split of the ALL and CG mature oligodendrocyte clusters into two clusters (numbers 1 and 6), the second one containing half of the mature oligodendrocytes annotated as ischemic whereas the other half is included in Cluster 1. A second major difference concerns neurons, which are split in only three clusters, a large one (Cluster 2) with all types of neurons except dorsal horn excitatory neurons, which cluster together in a second group (Cluster 3, all dorsal excitatory (DE) except for DE Maf-Rorb-Cpne4). The third cluster (number 10) is composed of ventral neurons from three populations mainly represented in Cluster 2. The third major difference concerns immune cells, which appear divided into peripheral and central (microglial) populations, the former one associated with vascular cells. There is also a small cluster, corresponding to cells from sample GSM5243303 without consistent assignment to any population.

Despite these differences, as a whole, the clustering patterns from the three datasets are mainly consistent with one another, differentiating among the major neural cell lineages, the vascular, and the immune cells. The distribution of the 83,000 cells within clusters across datasets is similar in both the number of cells in each major cluster and in the cells that form part of the cluster, irrespectively of the employed datasets (

Table 2,

Figure 4).

Clustering patterns are also similar to those obtained in previous studies (Squair et al., 2021; Matson et al., 2022; Skinnider et al., 2024). The patterns here observed are highly similar to the 14 clusters present in layer 2 of Tabulae Paralytica, including an early split in the oligodendrocyte lineage among OPCs and mature and differentiating oligodendrocytes, or the loose grouping of astrocytes and ependymal cells. However, the clustering patterns clearly differ in neurons, which in Tabulae appears as a single cluster that is divided into dorsal and ventral populations at higher resolution, whereas in our analyses appear dispersed in up to five clusters, with a major division between DE neurons and the rest of neuronal populations. Relative to SeqSeek atlas (Russ et al., 2022) and the studies that employed it (Matson et al., 2022), the basic grouping remain consistent but with some differences, particularly in the presence of meningeal and Schwann cell clusters and a consistent neuronal cluster that it is not supported in our results.

3.5. Cluster Composition is Retained Among Samples

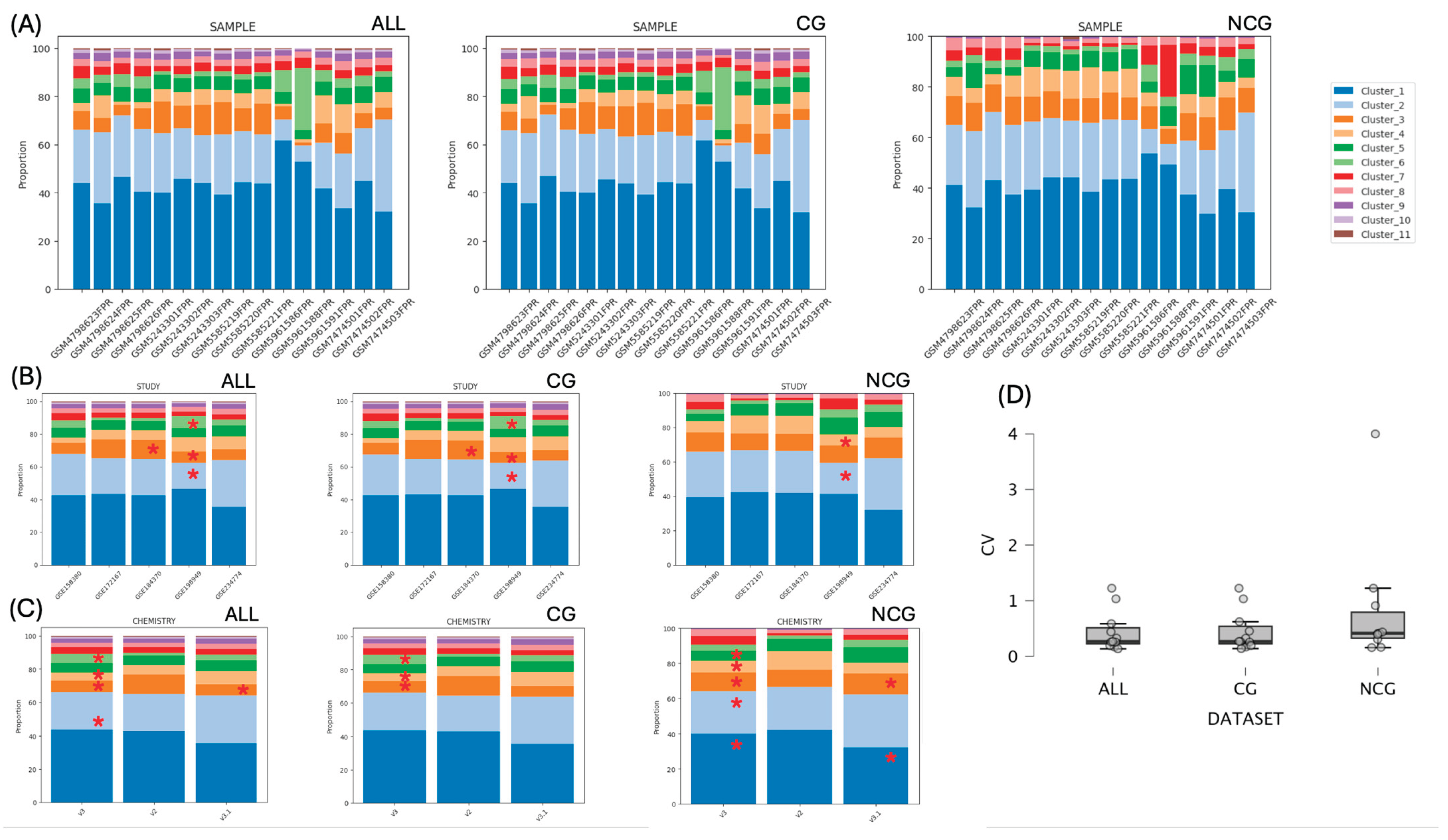

One objective of this study is to test whether the composition, in terms of cell typologies and abundances, is preserved between samples, with their specific methodological conditions (

Table 1). A visual inspection of the cluster abundance in the different samples (illustrated in

Figure 5) reveals that all clusters are present in all samples with consistent abundances. Lack of consistency is observed in the clustering obtained using the NCG dataset, where cluster 11 is exclusively composed of cells from sample GSE5243303 and cluster 10 is absent in four samples.

To evaluate the consistency across datasets, we calculated the coefficient of variation (CV) of the abundance of each cluster in all samples of each dataset. As shown in

Figure 5D, CVs are low to moderate for most clusters (<0.5), whereas those corresponding to vascular, immune, and ependymal cells show higher variations (>0.5). CV values are in the range described by Bjugn (1993) for five individuals in their stereological analysis of the spinal cord cell composition (range: 0.109 to 0.750 depending on the cell and location). The employed dataset does not seem to deeply affect the consistency among samples (H Kruskal-Wallis=0.962, p=0.612).

To further explore the potential effects of the Study, Chemistry or Sex we employed scCODA, a bayesian modelling specifically designed to perform compositional data analysis in scRNA-seq. Analyses in the three datasets confirm that Sex does not affect the cellular composition of any of the clusters. On the contrary, both the Chromium chemistry version and the Study affected the composition (

Supplementary Table S2). The analysis of the effects of the study indicates that the samples included in study GSE198949 (Squair

et al., 2021) have a credible effect (according to scCODA terminology) on the abundance of the astrocyte and the large neuronal clusters in the three datasets (ALL, CG, and NCG), as well as on the immune cluster in ALL and CG datasets. This is in agreement with our visual observations on the anomalous abundances in the clusters of samples GSM5961586 and GSM5961588, both from GSE198949 study (

Figure 5A). These two samples contain the lowest number of reads and number of cells in any of the samples and are included in an analysis devoted to analyze the relative performance of different methods of differential expression and their ability to account for variation between biological replicates in which the three included undamaged spinal cord samples show strong differences in the number of reads and cells. Additional effects were observed on the astrocyte cluster in study GSE184370. The scCODA analyses also revealed effects of the Chromium version on the same astrocyte, vascular, neuronal, and immune cell clusters in the three datasets. Major effects are identified in the Chemistry vs 3, which was employed in study GSE198949.

Overall, results suggest that both samples GSM5961586 and GSM5961588 can be considered as outliers and better removed to estimate cell abundances in the spinal cord. Following removal, the resulting values (

Table 3) indicate that the lumbar spinal cord is composed mainly of glial cells (median %: 53.9%, with oligodendrocytes contributing to a 41.1% of the total spinal cells), whereas neurons account for nearly one third (median 36.5%), with immune and endothelial cells contributing together to a 10%, and non-neuronal to neuronal (nNNR) and glial to neuron ratios of 1.8 and 1.6, respectively.

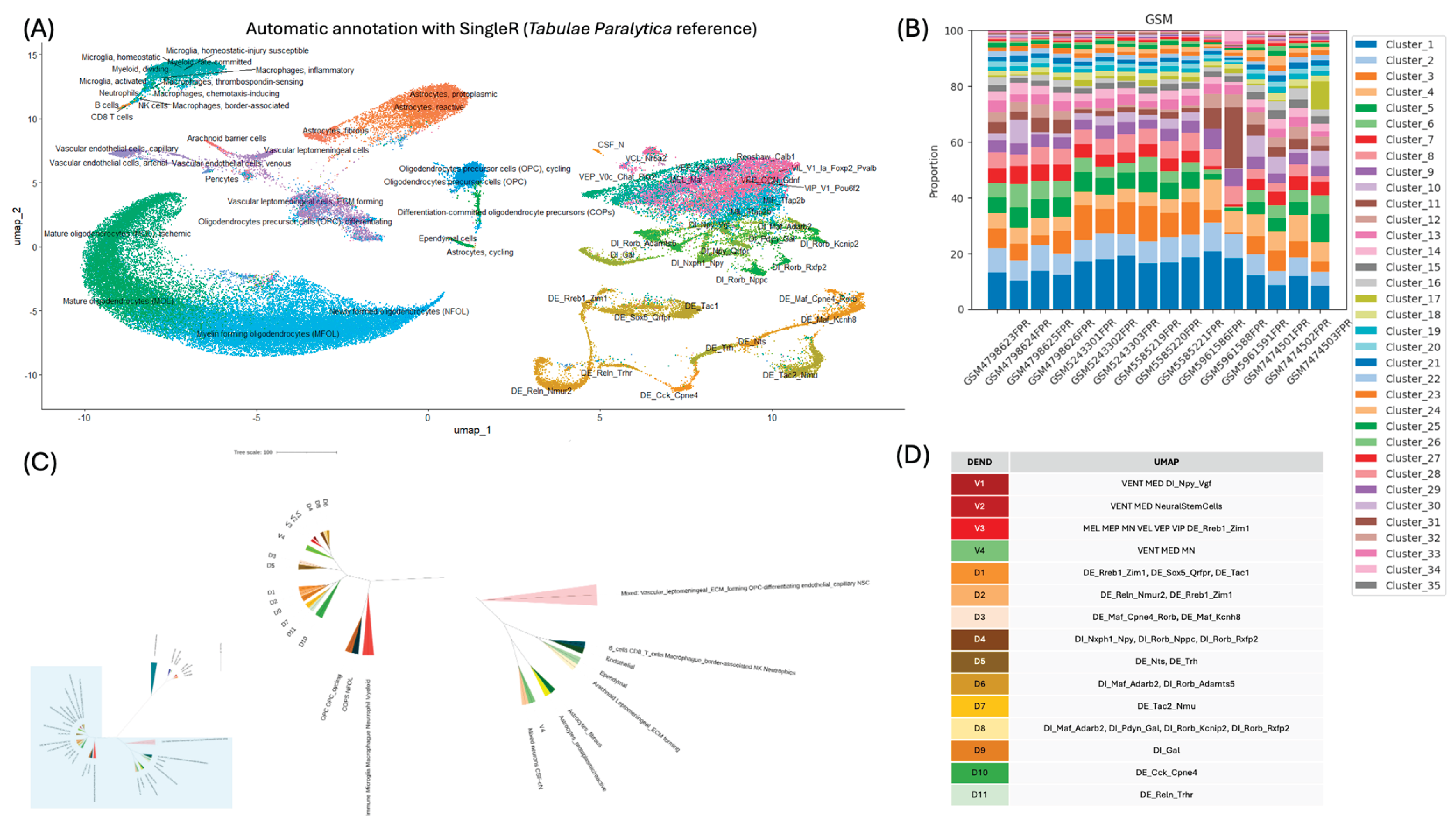

3.6. Fine Clustering and Neuronal Populations

To achieve finer cell clustering, we analyzed the ALL dataset, covering both coding and non-coding genes, at a resolution of 1. The analysis identified 35 clusters, nine corresponding to oligodendrocyte and OPCs, three to the astro-ependymal lineage, two to immune cells, three to endothelial cells, one is a mixed cluster, and the remaining 17 correspond to neuronal populations (see

Figure 6A and

Supplementary Table S3). Focusing on the neuronal clusters, we can identify seven clusters of dorsal excitatory neurons that comprise all cells within the 11 DE populations established in

Tabulae Paralytica. Three of these populations (DE_Tac2_Nmu, DE_Cck_Cpne4, and DE_Reln_Trhr) appear in their own clusters, isolated from the other neurons, whereas the remaining DE populations appear in clusters comprising 2 or more DR populations. Only the population DE_Rreb1_Zim1 appears distributed among different clusters including a mixed cluster comprising ventral and medial neurons along with cells from this population. Some of the clusters combining two or more populations agree with the hierarchical clustering available at

Tabulae Paralytica such as cluster 18, which comprises DE_Maf_Cpne4_Rorb DE_Maf_Kcnh8 cells. These two populations appear closely related in

Tabulae Paralytica. The other group of spinal neurons that appear clearly defined are the dorsal inhibitory (DI) neurons, which appear grouped in five clusters. Two of them correspond to single populations from the

Tabulae Paralytica, namely DI_Gal and DI_Npy_Qrfpr. DI_Gal neurons appear clearly separated from the rest of neurons and appear as an individual cluster even at coarse resolution. The remaining eight DI populations described in

Tabulae Paralytica appear distributed in the remaining three DI clusters, except for the DI_Npy_Vgf population that appears in a mixed neuron cluster.

Contrary to the dorsal neurons, the ventral and medial neurons are not resolved in this analysis. These neurons appear distributed in five clusters that combine multiple populations, in many cases overlapping with other clusters. A compositional analysis using scCODA indicates that the three largest of these clusters are influenced by the sample of origin (

Figure 6B;

Supplementary Table S4) indicating that the transcriptional differences among ventral and medial neuron populations are small, lesser than the transcriptional differences derived from the methodological differences between studies or samples. Compositional analyses also identified effects of the study or the employed chemistry in other four neuronal clusters, namely cluster 4 composed of a combination of all kind of neurons including all CSF-cN in the sample, and clusters 14, 19, and 23, which are clusters of various DE and DI populations. It is interesting that only the study GSE198949 (Squair

et al., 2021) was identified to affect the neuronal clusters, which was the study that also identified to affect the composition of the coarse clusters, likely due to the inclusion of two anomalous samples. Trying to resolve these mixed populations and to reduce the effects of the study and chemistry on the clustering, we also performed a dedicated subclustering analysis on all cells labeled as “neurons” in the coarse clustering, following Russ

et al. (2022) pipeline (the subsets of neuronal cells from each sample were merged and integrated using Harmony before clustering). However, the resulting clusters were even more heavily influenced by the study design and sample chemistry, with many clusters showing no clear association with cellular populations. We also attempted to subcluster the neuronal cells from the ALL dataset, with even worse results.

To investigate the transcriptional relationships between the identified neuronal populations, we focused on the neuronal portion of the dataset and performed hierarchical clustering based on the average gene expression of each neuronal cluster, using Euclidean distance and the Ward.D2 method. The resulting unrooted dendrogram (

Figure 6C) reveals that nearly all neuronal clusters group together into a single coherent branch, suggesting shared transcriptional programs among spinal neurons. Notably, two clusters appear separated from the main neuronal grouping: one composed predominantly of ventral neurons, and another mixed cluster that includes heterogeneous neuronal types along with CSF-contacting neurons (CSF-cN). To facilitate interpretation, an additional panel (

Figure 6D) displays the correspondence between the full population names an-notated in the UMAP and the abbreviated labels used in the dendrogram. The detailed composition of each cluster is provided

Supplementary Table S3.

3.7. Non-Coding RNA Markers of Spinal Populations

Differential expression analyses were conducted using the FindAllMarkers function within our integrated Seurat dataset to identify the top ten most differentially expressed markers per cluster. Our analysis primarily highlighted the presence of non-coding RNAs, including pseudogenes and long non-coding RNAs, demonstrating significant cell-type specificity.

Our current findings, detailed in Supplementary Table 5, reinforce the fundamental role of ncRNAs in defining cell subtype identities across various lineages. Specifically, the oligodendrocyte lineage exhibited a substantial presence of pseudogenes and lncRNAs, particularly within clusters 1 through 9. Markers such as Gm42413, 6030407O03Rik, and Gm37459 suggest potential roles in differentiation and specific oligodendrocyte states, including ischemic conditions (clusters 4 and 9).

Neuronal populations showed significant diversity in ncRNA markers, with pseudogenes and lncRNAs widely distributed across clusters. Notably, Cluster 17 ("mixed neurons") exhibited an exceptionally diverse ncRNA profile, including microRNAs (miRNAs; e.g., Mir6236), long intergenic non-coding RNAs (lincRNAs; e.g., Meg3), and ribosomal RNAs (rRNAs; e.g., Rn18s-rs5). It is worth mentioning that, according to scCODA compositional analyses, there are differences in the composition of this cluster depending on the version of 10X Chromium employed. Moreover, a closer look at the composition of this cluster indicates that it is particularly enriched on cells from sample GSM7474503 of Skinnider et al. (2024) study.

Astroglial clusters (3, 27, and 30) and immune-related clusters (11 and 34) also presented pseudogenes and lncRNAs as distinctive markers. Vascular endothelial cluster 35 uniquely featured an antisense lncRNA (Tbx3os1), indicating specific regulatory functions. Cluster 10, characterized by mixed vascular, endothelial, and neural stem cell populations, featured a singular mitochondrial ribosomal RNA (mt-Rnr1), potentially reflecting specialized metabolic or regulatory states. In contrast, clusters 13 (OPCs), 24 (arachnoid leptomeningeal cells), 26 (endothelial), and 32 (neuronal DI_Npy_Qrfpr) lacked notable ncRNA markers.

4. Discussion

The findings presented herein provide a comprehensive and high-resolution view of the cellular architecture of the adult mouse lumbar spinal cord under physiological conditions. By harmoniously integrating over 86,000 nuclei from five public datasets, we constructed a single-nucleus transcriptomic atlas that identifies all major spinal cord cell lineages and resolves 17 transcriptionally distinct neuronal subtypes. This broad coverage and analytical depth complement previous studies such as those by Russ et al. (2022) and Skinnider et al. (2024), by systematically incorporating non-coding information and enhancing statistical power through the integration of a larger number of nuclei.

In constructing this atlas, we also identified technical and curatorial challenges inherent to the integration of datasets from independent sources. For instance, we excluded the samples from GSE165003 (Squair et al., 2021) because they were exact duplicates of those in GSE184370–an issue not clearly annotated in public repositories, which could have introduced a bias in cell-type proportions and pseudoreplication artifacts. Additionally, we observed that cells with low complexity and/or high mitochondrial and ribosomal RNA content tended to co-cluster across several samples, suggesting a shared underlying low-quality phenomenon likely related to stress-induced transcription of partial RNA degradation. These findings reinforce the importance of thorough quality control beyond standard filters, particularly when working with archived datasets.

A key methodological innovation of this study was the systematic inclusion of ncRNAs–including lncRNAs, pseudogenes, antisense transcripts, lincRNAs, and ribosomal RNAs–in clustering and differential expression analyses. This approach uncovered transcriptional patterns that are not detectable when analyzing coding genes alone and substantially improved the resolution of neuronal subtypes. For example, pseudogenes such as Gm42413 and Gm37459, lncRNAs such as 6030407O03Rik, and other non-coding elements such as Mir6236, Meg3, and Tbx3os1 exhibited highly restricted expression across specific cell populations, suggesting their potential roles as lineage markers or as functional elements in transcriptional regulatory networks. Notably, the specific expression of Tbx3os1 in endothelial cells may reflect specialized regulatory functions within the spinal vascular microenvironment.

Despite the lower gene counts per nucleus in the non-coding dataset, we found that this information retained sufficient transcriptional variability to allow effective clustering. Interestingly, when comparing the clustering structures derived from coding, non-coding, and combined data, we observed that the inclusion of non-coding genes contributed to a more hierarchical and consistent partitioning of major spinal cell types. This suggests that non-coding RNAs enhance the robustness of transcriptomic classification, not only by increasing resolution at the subtype level but also by stabilizing broader lineage-level distinctions across analytical resolutions.

In addition to expanding the resolution of major lineages, our analysis highlights the underexplored yet critical role of non-coding RNAs as molecular markers in the spinal cord. The absence of these ncRNAs in conventional marker lists based on coding genes underscores their value as complementary classifiers, particularly for distinguishing fine subtypes within the oligodendrogial and neuronal lineages. The diversity of ncRNA markers–ranging from pseudogenes and lincRNAs to microRNAs and antisense transcripts–observed in specific neuronal and glial clusters suggests the presence of complex regulatory networks. This is especially evident in mixed neuronal clusters, where ncRNAs may reflect distinct physiological states or technical artifacts related to read depth and chemistry, as suggested by the enrichment of certain clusters in samples with low coverage. Conversely, the absence of ncRNA markers in specific clusters may indicate a predominant reliance on protein-coding or other regulatory transcripts for subtype specification. Together, these findings reinforce the importance of systematically including non-coding elements in transcriptomic atlases and downstream functional studies.

The annotation of clusters based on two independent references–Tabulae Paralytica and SeqSeek–also revealed differences in granularity and consistency. While Tabulae-based annotations tended to assign each cluster to a dominant and coherent cell type (e.g., astrocytes, mature oligodendrocytes), SeqSeek-derived annotations resulted in a more fragmented distribution, with many clusters containing apparent mixtures of cell types. These differences likely reflect the structure and resolution of the underlying reference datasets, rather than the annotation method itself. Based on these observations, and supported by additional analyses using SingleR with SeqSeek reference, we selected Tabulae Paralytica as the most appropriate reference for this dataset due to its higher cell-type specificity and lower annotation entropy.

Further analysis of clustering differences among datasets revealed potential biological signals and limitations. Notably, the inclusion of non-coding information resulted in the separation of the mature oligodendrocyte population into two distinct clusters, one of which was enriched in cells annotated as ischemic. Although speculative, this pattern may reflect distinct regulatory states within the mature oligodendrocyte lineage. Similarly, a small subset of ventral neurons clustered independently of their main population, potentially indicating transcriptional deviations or technical artifacts. Additionally, one minor cluster from a single sample could not be consistently assigned to any known population, suggesting cell stress or data quality issues. Importantly, while clustering patterns were broadly consistent with those reported in previous atlases such as Tabulae Paralytica and SeqSeek, our results diverged in the organization of neuronal populations. In contrast to the coarse dorsal-ventral division in Tabulae or the unified neuronal cluster observed in some earlier studies (Dobrott, Sathyamurthy & Levine, 2019), our analysis identified up to five transcriptionally distinct neuronal clusters, including a specific separation between dorsal excitatory neurons and all other neuronal subtypes. These differences highlight the added resolution provided by our integrative approach and underscore the influence of reference datasets and clustering resolution on cell-type definition.

Our fine-resolution analysis further demonstrated that several dorsal excitatory and inhibitory neuronal subtypes formed well-defined and transcriptionally distinct clusters, in some cases mirroring the hierarchical structure described in Tabulae Paralytica. In contrast, ventral and medial neurons showed greater heterogeneity and lower resolution, appearing scattered across multiple overlapping clusters. Compositional analysis using scCODA suggested that the transcriptional differences among these ventral subtypes were smaller than the variance introduced by methodological factors such as study origin or sequencing chemistry. This was especially evident in clusters influenced by the GSE198949 dataset. Attempts to resolve these populations through additional subclustering approaches–both Harmony-based integration and direct reclustering of the neuron subset–proved ineffective, likely due to residual batch effects and low intrinsic variability between subtypes. These findings emphasize both the strengths and current limitations of single-nucleus transcriptomics for resolving complex neuronal diversity, particularly when integrating data across multiple studies

Comparison with previous atlases highlights notable distinctions. Unlike the Tabulae Paralytica resource, in which dorsal and ventral neuronal populations are grouped together at low resolution, our analysis disaggregates these populations into multiple functionally defined clusters. Furthermore, the estimated cellular proportions–predominantly glial (~54%), followed by neurons (~36%) and immune-vascular cells (~10%)–are consistent with stereological data (Bjugn, 1993) and more recent transcriptomic estimates (Skinnider et al., 2024), yet they differ substantially from earlier datasets such as that of Sathyamurthy et al. (2018), whose overestimation of neuronal fractions was later corrected by Russ et al. (2022).

Analysis of the compositional consistency across samples revealed an overall preservation of major cell type proportions, with low-to-moderate variability across most clusters. However, two samples from the GSE198949 study (GSM5961586 and GSM5961588) displayed anomalous cluster abundances and lower sequencing depth, which likely influenced their divergence in cell composition and were accordingly considered outliers. The application of scCODA confirmed credible effects of both the study and the Chromium chemistry version on the abundance of astrocytic, neuronal, vascular, and immune clusters, reinforcing the need to account for technical covariates in multi-study analyses. After excluding the outliers, the estimated cell-type proportions aligned closely with stereological benchmarks (Bjugn, 1993) and with recent single-cell studies such as Skinnider et al. (2024), indicating a predominance of glial cells (~54%) followed by neurons (~36%) and a minor fraction of vascular and immune cells (~10%). These estimates differ substantially from earlier atlases such as Zeisel et al. (2018) and Sathyamurthy et al. (2018), whose neuron counts appear respectively underestimated and overestimated–discrepancies that were partly resolved in the reanalyses conducted by Russ et al. (2022). This supports the reliability of the current integration framework and highlights the value of rigorous QC and statistical modeling in establishing accurate cell composition references.

Altogether, this atlas represents a valuable reference resource for neurobiological research, offering a novel integration of the non-coding transcriptome within the central nervous system. Beyond providing a robust tool for the physiological characterization of the spinal cord, this work lays a solid foundation for future investigations into synaptic plasticity, spinal cord injury responses, and the identification of therapeutic targets grounded in transcriptional and epigenetic regulation. Future studies should aim to functionally assess the most specific ncRNAs and explore their dynamic expression in models of spinal cord injury and regeneration.

Limitations and Caveats

The integration pipeline effectively reduced technical variability across studies; however, important limitations persist. Residual methodological differences–such as the version of the 10X Genomics sequencing chemistry–were evident in specific clusters associated with outlier samples, which were excluded from quantitative analyses. Although batch correction mitigated inter-study variation, differences in sequencing depth may still influence the detection of low-abundance ncRNAs. Furthermore, the study lacks functional validation (e.g., in situ hybridization, perturbation assays) to confirm the cell-type specificity of the identified ncRNAs. Finally, the atlas is restricted to healthy adult tissue, limiting insight into the dynamics of ncRNA signatures during development or in pathological states. In addition, our current clustering approach did not resolve transcriptionally distinct subtypes within ventral neuronal populations, which remained dispersed across overlapping clusters. This may reflect insufficient transcriptional variability, batch effects, or limitations inherent to the resolution of single-nucleus data in specific neuronal lineages.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org. Figure S1: Clustree results of the three datasets (ALL, coding and non-coding) showing the clusters obtained at resolutions from 0.01 to 0.05. The red square indicates the chosen resolution for each dataset. The three resolutions lead to 11 clusters to ease comparisons; Table S1: Spreadsheet summarizing information on the samples and runs, including sequencing depth, platforms, accession numbers for each sample and run, etc; Table S2: Compositional analysis of the coarse clusters in ALL (coding and non-coding), CG (coding) and NCG (non-coding) datasets. The table shows the clusters affected by Study and Chemistry according to scCODA. DE: dorsal excitatory neurons.; Table S3: Annotation clusters made according to the populations in Tabulae Paralytica; Table S4: Compositional analysis of the fine clusters. The table shows the clusters affected by Study (left) and Chemistry (right) according to scCODA. Neuronal clusters are marked with an asterisk (*); Table S5: Non-coding RNA marker genes by cell cluster and their annotation.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.R-A., R.M.M., F.J.E., and M.N-D.; methodology, P.R-A., R.M.M., and M.N-D.; software, P.R-A., E.V., R.M.M., F.J.E., and M.N-D.; validation, P.R-A., and M.N-D.; formal analysis, all authors; investigation, P.R-A., E.V., R.M.M., F.J.E., and M.N-D.; resources, M.N-D.; data curation, all authors; writing—original draft preparation, P.R-A., E.V., F.J.E., and M.N-D.; writing—review and editing, all authors.; visualization, P.R-A., E.V., and M.N-D.; supervision, F.J.E. and M.N-D.; project administration, M.N-D.; funding acquisition, M.N-D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the Council of Education, Culture and Sports of the Regional Government of Castilla La Mancha (Spain) and co-financed by the European Union (FEDER) “A way to make Europe” (project references SBPLY/17/000376 and SBPLY/21/180501/000097). F.J.E. receives funding for research from the University of Jaén (PAIUJA-EI_CTS02_2023), from the Junta de Andalucía (BIO-302), and is partially financed by the Ministry of Science and Innovation, the State Research Agency (AEI), and the European Regional Development Fund (ERDF—Ref: PID2021-122991NB-C21). P.R-A. is funded by the Council of Education, Culture, and Sports of the Regional Government of Castilla La Mancha (Spain). C.P.A. and J.G.F. were funded by the Council of Education, Culture, and Sports of the Regional Government of Castilla La Mancha (Spain).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this manuscript/study, the author(s) used Scientific Writing Assistant for the purposes of grammar text revision. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ALL |

Coding + non-coding genes dataset |

| CG |

Coding genes dataset |

| CNS |

Central nervous system |

| CV |

Coefficient of variation |

| DE |

Dorsal excitatory neurons |

| DI |

Dorsal inhibitory neurons |

| GNR |

Glial neuronal ratio |

| IF |

Isotropic Fractionator |

| k-NN |

k-nearest neighbor |

| lincRNAs |

Long intervening non-coding RNAs |

| lncRNAs |

Long non-coding RNAs |

| NCG |

Non-coding genes dataset |

| ncRNAs |

Non-coding RNAs |

| nNNR |

Non-neuronal to neuronal ratio |

| OPCs |

Oligodendrocyte precursor cells |

| PC |

Principal Component |

| PCA |

Principal Component Analysis |

| QC |

Quality control |

| SCI |

Spinal cord injury |

| snRNA-seq |

Single-nucleus RNA sequencing |

| snT |

Single nucleus transcriptomics |

| STE |

Stereology |

| UMAP |

Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection |

| UMI |

Unique molecular identifier |

| |

|

References

- Andrews, S. FastQC: A quality control tool for high throughput sequence data [Software]. 2010. https://www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/fastqc/.

- Aran, D.; Looney, A.P.; Liu, L.; Wu, E.; Fong, V.; Hsu, A.; Chak, S.; Naikawadi, R.P.; Wolters, P.J.; Abate, A.R.; Butte, A.J.; Bhattacharya, M. Reference-based analysis of lung single-cell sequencing reveals a transitional profibrotic macrophage. Nat Immunol. 2019, 20, 163–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bjugn, R. The use of the optical disector to estimate the number of neurons, glial and endothelial cells in the spinal cord of the mouse--with a comparative note on the rat spinal cord. Brain Res. 1993, 627, 25–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Büttner, M.; Ostner, J.; Müller, C.L.; Theis, F.J.; Schubert, B. scCODA is a Bayesian model for compositional single-cell data analysis. Nat Commun. 2021, 12, 6876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DeJong, T.M. A comparison of three diversity indices based on their components of richness and evenness. Oikos 1975, 222–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobin, A.; Davis, C.A.; Schlesinger, F.; Drenkow, J.; Zaleski, C.; Jha, S.; Batut, P.; Chaisson, M.; Gingeras, T.R. STAR: ultrafast universal RNA-seq aligner. Bioinformatics 2013, 29, 15–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobrott, C.I.; Sathyamurthy, A.; Levine, A.J. Decoding Cell Type Diversity Within the Spinal Cord. Curr Opin Physiol. 2019, 8, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleming, S.J.; Chaffin, M.D.; Arduini, A.; Akkad, A.D.; Banks, E.; Marioni, J.C.; Philippakis, A.A.; Ellinor, P.T.; Babadi, M. Unsupervised removal of systematic background noise from droplet-based single-cell experiments using CellBender. Nat Methods. 2023, 20, 1323–1335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Y.; Rusznák, Z.; Herculano-Houzel, S.; Watson, C.; Paxinos, G. Cellular composition characterizing postnatal development and maturation of the mouse brain and spinal cord. Brain Struct Funct. 2013, 218, 1337–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Y.; Yu, Y.; Paxinos, G.; Watson, C.; Rusznák, Z. Aging-dependent changes in the cellular composition of the mouse brain and spinal cord. Neuroscience 2015, 290, 406–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Germain, P.L.; Lun, A.; Garcia Meixide, C.; Macnair, W.; Robinson, M.D. Doublet identification in single-cell sequencing data using scDblFinder. F1000Res. 2022, 10, 979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, Y.; Stuart, T.; Kowalski, M.H.; Choudhary, S.; Hoffman, P.; Hartman, A.; Srivastava, A.; Molla, G.; Madad, S.; Fernandez-Granda, C.; Satija, R. Dictionary learning for integrative, multimodal and scalable single-cell analysis. Nat Biotechnol. 2024, 42, 293–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- JASP team. JASP (Version 0.19.3) Computer software. 2024.

- Kaminow, B.; Yusunov, D.; Dobin, A. STARsolo: accurate, fast and versatile mapping/quantification of single-cell and single-nucleus RNA-seq data. bioRxiv 2024. [CrossRef]

- Kathe, C.; Skinnider, M.A.; Hutson, T.H.; Regazzi, N.; Gautier, M.; Demesmaeker, R.; Komi, S.; Ceto, S.; James, N.D.; Cho, N.; Baud, L.; Galan, K.; Matson, K.J.E.; Rowald, A.; Kim, K.; Wang, R.; Minassian, K.; Prior, J.O.; Asboth, L.; Barraud, Q.; Lacour, S.P.; Levine, A.J.; Wagner, F.; Bloch, J.; Squair, J.W.; Courtine, G. The neurons that restore walking after paralysis. Nature 2022, 611, 540–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korsunsky, I.; Millard, N.; Fan, J.; Slowikowski, K.; Zhang, F.; Wei, K.; Baglaenko, Y.; Brenner, M.; Loh, P.R.; Raychaudhuri, S. Fast, sensitive and accurate integration of single-cell data with Harmony. Nat Methods. 2019, 16, 1289–1296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matson, K.J.E.; Russ, D.E.; Kathe, C.; Hua, I.; Maric, D.; Ding, Y.; Krynitsky, J.; Pursley, R.; Sathyamurthy, A.; Squair, J.W.; Levi, B.P.; Courtine, G.; Levine, A.J. Single cell atlas of spinal cord injury in mice reveals a pro-regenerative signature in spinocerebellar neurons. Nat Commun. 2022, 13, 5628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Open, AI. ChatGPT. Large language model. 2025. https://chat.openai.com/.

- R Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. 2024. https://www.R-project.org/.

- Russ, D.E.; Cross, R.B.P.; Li, L.; Koch, S.C.; Matson, K.J.E.; Yadav, A.; Alkaslasi, M.R.; Lee, D.I.; Le Pichon, C.E.; Menon, V.; Levine, A.J. Author Correction: A harmonized atlas of mouse spinal cord cell types and their spatial organization. Nat Commun. 2021, 13, 1033–10.1038, Erratum for: Nat Commun. 2021, 12, 5722.. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sathyamurthy, A.; Johnson, K.R.; Matson, K.J.E.; Dobrott, C.I.; Li, L.; Ryba, A.R.; Bergman, T.B.; Kelly, M.C.; Kelley, M.W.; Levine, A.J. Massively Parallel Single Nucleus Transcriptional Profiling Defines Spinal Cord Neurons and Their Activity during Behavior. Cell Rep. 2018, 22, 2216–2225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skinnider, M.A.; Gautier, M.; Teo, A.Y.Y.; Kathe, C.; Hutson, T.H.; Laskaratos, A.; de Coucy, A.; Regazzi, N.; Aureli, V.; James, N.D.; Schneider, B.; Sofroniew, M.V.; Barraud, Q.; Bloch, J.; Anderson, M.A.; Squair, J.W.; Courtine, G. Single-cell and spatial atlases of spinal cord injury in the Tabulae Paralytica. Nature 2024, 631, 150–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Squair, J.W.; Gautier, M.; Kathe, C.; Anderson, M.A.; James, N.D.; Hutson, T.H.; Hudelle, R.; Qaiser, T.; Matson, K.J.E.; Barraud, Q.; Levine, A.J.; La Manno, G.; Skinnider, M.A.; Courtine, G. Confronting false discoveries in single-cell differential expression. Nat Commun. 2021, 12, 5692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Squair, J.W.; Milano, M.; de Coucy, A.; Gautier, M.; Skinnider, M.A.; James, N.D.; Cho, N.; Lasne, A.; Kathe, C.; Hutson, T.H.; Ceto, S.; Baud, L.; Galan, K.; Aureli, V.; Laskaratos, A.; Barraud, Q.; Deming, T.J.; Kohman, R.E.; Schneider, B.L.; He, Z.; Bloch, J.; Sofroniew, M.V.; Courtine, G.; Anderson, M.A. Recovery of walking after paralysis by regenerating characterized neurons to their natural target region. Science 2023, 381, 1338–1345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Traag, V.A.; Waltman, L.; van Eck, N.J. From Louvain to Leiden: guaranteeing well-connected communities. Sci Rep. 2019, 9, 5233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.Y.; Wen, Z.J.; Xu, H.M.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Y.F. Exosomal noncoding RNAs in central nervous system diseases: biological functions and potential clinical applications. Front Mol Neurosci. 2022, 15, 1004221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zappia, L.; Oshlack, A. Clustering trees: a visualization for evaluating clusterings at multiple resolutions. Gigascience 2018, 7, giy083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeisel, A.; Hochgerner, H.; Lönnerberg, P.; Johnsson, A.; Memic, F.; van der Zwan, J.; Häring, M.; Braun, E.; Borm, L.E.; La Manno, G.; Codeluppi, S.; Furlan, A.; Lee, K.; Skene, N.; Harris, K.D.; Hjerling-Leffler, J.; Arenas, E.; Ernfors, P.; Marklund, U.; Linnarsson, S. Molecular Architecture of the Mouse Nervous System. Cell 2018, 174, 999–1014.e22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Data Processing Pipeline. Each raw FastQ file from NCBI was aligned to the GRCm39 mouse genome with M33 annotation, including coding and non-coding genes. Post-alignment, we performed rigorous quality controls to remove gene- and cell-level noise and artifacts. Samples were then merged to produce three datasets: coding-only, non-coding only, and combined. Each dataset was independently integrated, followed by Leiden clustering and manual annotation to compare major clusters. The combined dataset was further analyzed to identify discrete neuronal subpopulations using the same clustering strategy applied to neuron-bearing clusters.

Figure 1.

Data Processing Pipeline. Each raw FastQ file from NCBI was aligned to the GRCm39 mouse genome with M33 annotation, including coding and non-coding genes. Post-alignment, we performed rigorous quality controls to remove gene- and cell-level noise and artifacts. Samples were then merged to produce three datasets: coding-only, non-coding only, and combined. Each dataset was independently integrated, followed by Leiden clustering and manual annotation to compare major clusters. The combined dataset was further analyzed to identify discrete neuronal subpopulations using the same clustering strategy applied to neuron-bearing clusters.

Figure 2.

Quality control. Left side shows (from top to bottom): (i) the distribution of cells by mitochondrial gene content, (ii) a complexity plot (UMIs vs. genes), (iii) a UMAP visualization of cell distribution, and (iv) the distribution of predicted doublets for sample GSM5585219), which is representative of samples without significant quality control issues. Right side depicts sample GSM4798623, which presents a population of anomalous cells characterized by high mitochondrial gene expression and low complexity. The lowest right graph shows doublet distribution in sample GSE7474501, which presents the highest percentage of doublets in all analyzed samples (14%).

Figure 2.

Quality control. Left side shows (from top to bottom): (i) the distribution of cells by mitochondrial gene content, (ii) a complexity plot (UMIs vs. genes), (iii) a UMAP visualization of cell distribution, and (iv) the distribution of predicted doublets for sample GSM5585219), which is representative of samples without significant quality control issues. Right side depicts sample GSM4798623, which presents a population of anomalous cells characterized by high mitochondrial gene expression and low complexity. The lowest right graph shows doublet distribution in sample GSE7474501, which presents the highest percentage of doublets in all analyzed samples (14%).

Figure 3.

Coarse clustering. UMAPs for ALL (A), coding (B), and non-coding (C) datasets. D) Boxplots comparing the distribution of cell populations according to Tabulae Paralytica and SeqSeek references among the clusters here identified. The Simpson diversity index was used to assess whether each annotated population was restricted to specific clusters (values close to 1) or more broadly distributed (values closer to 0).

Figure 3.

Coarse clustering. UMAPs for ALL (A), coding (B), and non-coding (C) datasets. D) Boxplots comparing the distribution of cell populations according to Tabulae Paralytica and SeqSeek references among the clusters here identified. The Simpson diversity index was used to assess whether each annotated population was restricted to specific clusters (values close to 1) or more broadly distributed (values closer to 0).

Figure 4.

Comparison of the cells included in the clusters from coding + non-coding (ALL), coding (CG), and non-coding (NCG) datasets. Venn diagrams illustrate the shared cells among the major clusters. OPCs: oligodendrocyte precursor cells.

Figure 4.

Comparison of the cells included in the clusters from coding + non-coding (ALL), coding (CG), and non-coding (NCG) datasets. Venn diagrams illustrate the shared cells among the major clusters. OPCs: oligodendrocyte precursor cells.

Figure 5.

(A) Bar diagrams showing cellular abundance in each cluster in the three datasets: ALL (coding + non-coding), coding, and non-coding datasets, respectively. (B) Bar diagrams showing the effects of Study on cluster abundance in ALL (coding + non-coding), coding, and non-coding datasets, respectively. (C) Bar diagrams showing the effects of Chemistry on cluster abundance in ALL (coding + non-coding), coding, and non-coding datasets, respectively. (D) Boxplot showing the distribution of the coefficient of variation of the abundance of each cluster in all simples of each dataset; ALL: coding + non-coding; CG: coding; NCG: non-coding. The credible effects detected with scCODA are marked with red asterisks in panels B and C.

Figure 5.

(A) Bar diagrams showing cellular abundance in each cluster in the three datasets: ALL (coding + non-coding), coding, and non-coding datasets, respectively. (B) Bar diagrams showing the effects of Study on cluster abundance in ALL (coding + non-coding), coding, and non-coding datasets, respectively. (C) Bar diagrams showing the effects of Chemistry on cluster abundance in ALL (coding + non-coding), coding, and non-coding datasets, respectively. (D) Boxplot showing the distribution of the coefficient of variation of the abundance of each cluster in all simples of each dataset; ALL: coding + non-coding; CG: coding; NCG: non-coding. The credible effects detected with scCODA are marked with red asterisks in panels B and C.

Figure 6.

Fine clustering analysis and relationships between neuronal populations in the integrated spinal cord atlas. (A) UMAP representation of the integrated dataset showing automatic cell type annotation using SingleR and the Tabulae Paralytica reference. (B) Radial plot showing the proportion of cells from each study within each cluster, highlighting inter-study variability in neuronal cluster composition. (C) Left: Unrooted dendrogram generated by hierarchical clustering (Euclidean distance, Ward.D2 method) of the average gene expression per cluster, focused on neuronal populations (blue area, magnified figure in right side). (D) Correspondence between the full names of neuronal populations displayed in the UMAP (panel A) and the shortened names used in the dendrogram (panel C), to facilitate visualization.

Figure 6.

Fine clustering analysis and relationships between neuronal populations in the integrated spinal cord atlas. (A) UMAP representation of the integrated dataset showing automatic cell type annotation using SingleR and the Tabulae Paralytica reference. (B) Radial plot showing the proportion of cells from each study within each cluster, highlighting inter-study variability in neuronal cluster composition. (C) Left: Unrooted dendrogram generated by hierarchical clustering (Euclidean distance, Ward.D2 method) of the average gene expression per cluster, focused on neuronal populations (blue area, magnified figure in right side). (D) Correspondence between the full names of neuronal populations displayed in the UMAP (panel A) and the shortened names used in the dendrogram (panel C), to facilitate visualization.

Table 1.

Samples included in the study. Additional data is available at

Supplementary Table S1. M: male; F: female.

Table 1.

Samples included in the study. Additional data is available at

Supplementary Table S1. M: male; F: female.

| GEO series ID |

GEO samples ID

(number of runs in SRA)

|

10X Genomics Chromium version |

Reads

(M)

|

Sex |

Age

(weeks)

|

Publication |

| GSE158380 |

GSM4798623 (6)

GSM4798624 (6)

GSM4798625 (6)

GSM4798626 (6) |

Single Cell 3’ Kit Version 3 |

172.4

166.0

174.2

178.7 |

M

M

F

F |

9 |

Russ et al. (2022) |

| GSE165003 |

GSM5024317 (8)*

GSM5024318 (8)*

GSM5024319 (8)* |

Single Cell Kit Version 2 |

267.2

282.8

274.5 |

F

F

F |

12-30 |

Squair et al. (2021) |

| GSE198949 |

GSM5961586 (1)

GSM5961588 (2)

GSM5961591 (8) |

Single Cell 3’ Kit Version 3 |

84.1

100.6

903.2 |

F

F

F |

8-15 |

Squair et al. (2023) |

| GSE172167 |

GSM5243301 (15)

GSM5243302 (15)

GSM5243303 (15) |

Single Cell Kit Version 2 |

505.6

593.9

648 |

F

F

F |

12-30 |

Matson et al. (2022) |

| GSE184370 |

GSM5585219 (8)

GSM5585220 (8)

GSM5585221 (8) |

Single Cell Kit Version 2 |

267.2

282.8

274.5 |

F

F

F |

12-30 |

Kathe et al. (2022) |

| GSE234774 |

GSM7474501 (8)

GSM7474502 (8)

GSM7474503 (8) |

Single Cell Kit Version 3.1 |

698.2

465

480.2 |

F

F

F |

8 |

Skinnider et al. (2024) |

Table 2.

Coarse clustering of spinal cord cells using coding, non-coding, and complete (Cod + Non Cod) datasets. Cluster annotation based on the automatic annotation using SingleR and Tabulae Paralytica reference. For each cell type, the number of included clusters, the number of cells in each cluster (between brackets), and the % of cells in common with equivalent clusters in the other 2 datasets are indicated. VE: ventral excitatory; VI: ventral inhibitory; DI: dorsal inhibitory; DE: dorsal excitatory; DI-Gal: Dorsal inhibitory expressing galanin neuropeptide.

Table 2.

Coarse clustering of spinal cord cells using coding, non-coding, and complete (Cod + Non Cod) datasets. Cluster annotation based on the automatic annotation using SingleR and Tabulae Paralytica reference. For each cell type, the number of included clusters, the number of cells in each cluster (between brackets), and the % of cells in common with equivalent clusters in the other 2 datasets are indicated. VE: ventral excitatory; VI: ventral inhibitory; DI: dorsal inhibitory; DE: dorsal excitatory; DI-Gal: Dorsal inhibitory expressing galanin neuropeptide.

| Lineage |

Coding |

Non-coding |

Cod + Non Cod |

| Oligodendrocytes |

1 (34,836) 98.9% |

2 (32,302/3,021) 97.6% |

1 (34,834) 98.9% |

| Oligodendrocyte precursor cells |

1 (2,968) 89.2% |

1 (2,697) 98.2% |

1 (2,986) 88.7% |

| Astrocytes |

1 (6,635) 93.9% |

1 (6,313) 98.7% |

1 (6,728) 92.6% |

| Ependymal |

1 (491) 93.7% |

1 (492) 93.5% |

1 (494) 93.1% |

| Vascular |

1 (5,603) 89.7%* |

2 (6,158/2,893) 89.2% |

1 (5,485) 90.8% |

| Microglia/immune |

1 (3,405) |

1 (3,407) |

| Neurons |

5 (32,440) 98.7% |

3 (32,464) 98.6% |

5 (32,444) 98.7% |

| VE, VI, DI |

1 (21,168) |

1 (22,903) |

1 (21,396) |

| DE |

3 (5,141/2,601/2,542) |

1 (9,455) |

3 (5,179/2,573/2,307) |

| DI-Gal |

1 (988) |

|

1 (989) |

| VE-VI |

|

1 (106) |

|

| Other |

|

1 (38**) |

|

| Total clusters |

11 (86,378) |

Table 3.

Descriptive statistics of the ALL clusters vs. abundance. Comparison with previously published abundance data. For average abundance calculations, values from samples GSM5961586 and GSM5961588 were excluded. snT: single nucleus transcriptomics; IF: isotropic fractionator; STE: stereology. OLIG: oligodendrocytes; NEUR: neurons; ASTRO: astrocytes; VASC: vascular cells; IMM: immune cells; OPC: oligodendrocyte precursor cells; EPEND: ependymal cells; nN/N: non-neuronal/neuronal ratio; GNR: glial neuronal ratio; TECH: technology.

Table 3.

Descriptive statistics of the ALL clusters vs. abundance. Comparison with previously published abundance data. For average abundance calculations, values from samples GSM5961586 and GSM5961588 were excluded. snT: single nucleus transcriptomics; IF: isotropic fractionator; STE: stereology. OLIG: oligodendrocytes; NEUR: neurons; ASTRO: astrocytes; VASC: vascular cells; IMM: immune cells; OPC: oligodendrocyte precursor cells; EPEND: ependymal cells; nN/N: non-neuronal/neuronal ratio; GNR: glial neuronal ratio; TECH: technology.

| SOURCE |

OLIGO |

NEUR |

ASTRO |

VASC |

IMM |

OPC |

EPEND

|

OTHER |

nN/N |

GNR |

TECH |

| ALL Dataset (Median) |

43.0 |

35.5 |

9.0 |

6.0 |

2.5 |

4.0 |

1.0 |

|

1.8 |

1.6 |

snT |

| ALL Dataset (Mean) |

41.1 |

36.5 |

8.9 |

6.1 |

3.1 |

3.4 |

0.6 |

|

1.7 |

1.5 |

snT |

| Fu et al., 2015 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

3.7 |

|

IF |

| Fu et al., 2013 – 4w |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

3.2 |

|

IF |

| Fu et al., 2013 – 40w |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

4.1 |

|

IF |

| Bjugn, 1993 |

39.3 |

33.6 |

|

19.1 |

|

|

|

8.0 |

2.0 |

1.2 |

STE |

| Zeisel (Russ) |

40.4 |

9.2 |

18.0 |

18.6 |

5.2 |

6.4 |

2.0 |

0.1 |

9.9 |

7.3 |

snT |

| Skinnider et al., 2024 |

49.7 |

35.3 |

3.4 |

4.2 |

3.1 |

3.3 |

0.7 |

|

1.8 |

1.6 |

snT |

| Sathyamurthy (Russ) |

24.8 |

28.0 |

13.6 |

7.9 |

2.4 |

1.6 |

2.4 |

19.3 |

2.6 |

1.5 |

snT |

| Sathyamurthy paper |

16.0 |

52.0 |

9.0 |

5.0 |

1.0 |

1.0 |

|

14.0 |

0.9 |

0.5 |

snT |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).