1. Introduction

Prostate cancer (PC)is the second most frequently diagnosed malignancy among men worldwide. In Spain alone, 32 ,967 new cases were reported in 2022, according to GLOBOCAN data [

1]. Since the introduction of the GS score (GS) , serum prostate-specific antigen (PSA) testing, and the ability to perform clinical staging through digital rectal examination or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), these parameters have been widely used to predict disease progression and to guide therapeutic decision-making—whether surgery, radiotherapy (RT) , or active surveillance [

2,

3].

The combination of these three factors has enabled the identification of validated risk groups based on the likelihood of biochemical recurrence (BCR) [

4]. These risk-stratification systems now constitute the backbone of major international clinical guidelines [

5,

6,

7]. In addition to the classic predictors (PSA, clinical stage, and GS score), other markers have been proposed as potential predictors of BCR, such as the absolute number as well as the percentage of positive biopsy cores and the presence of perineural invasion (PNI), among others [

8,

9]. However, most of the available evidence for these factors comes from surgical series, and their prognostic value in patients treated with RT remains less well established and has been insufficiently investigated to date [

10,

11].

External-beam radiotherapy (EBRT), either alone or in combination with androgen-deprivation therapy (ADT), is a well-established and effective treatment modality for localized PC across all risk groups [

12,

13,

14]. Nevertheless, despite modern image-guided and intensity-modulated techniques, a significant proportion of patients treated with curative intent will experience BCR in the years following therapy. It is estimated that 15–35 % of cases recur biochemically within the first five years after EBRT [

15].

The detection of BCR has important clinical implications, as it frequently precedes overt disease progression. Identifying recurrence early, particularly at PSA levels near the Phoenix threshold, can allow for timely intervention during a less advanced stage of tumor evolution [

16].

In this context, the high sensitivity and specificity of current imaging techniques—particularly prostate-specific membrane antigen positron-emission tomography (PSMA-PET)—have enabled targeted salvage treatments, such as focal or oligometastasis-directed therapies, with the goal of delaying or preventing progression to metastatic disease. These advances have significantly reshaped the personalized management of patients with recurrence after RT [

16,

17].

Even in patients who progress to metastatic stages, PC survival can be prolonged for several years, especially with the incorporation of novel hormonal agents such as androgen-receptor pathway inhibitors (ARPI) [

18,

19]. Nevertheless, early detection remains a cornerstone in optimizing long-term outcomes and guiding treatment decisions.

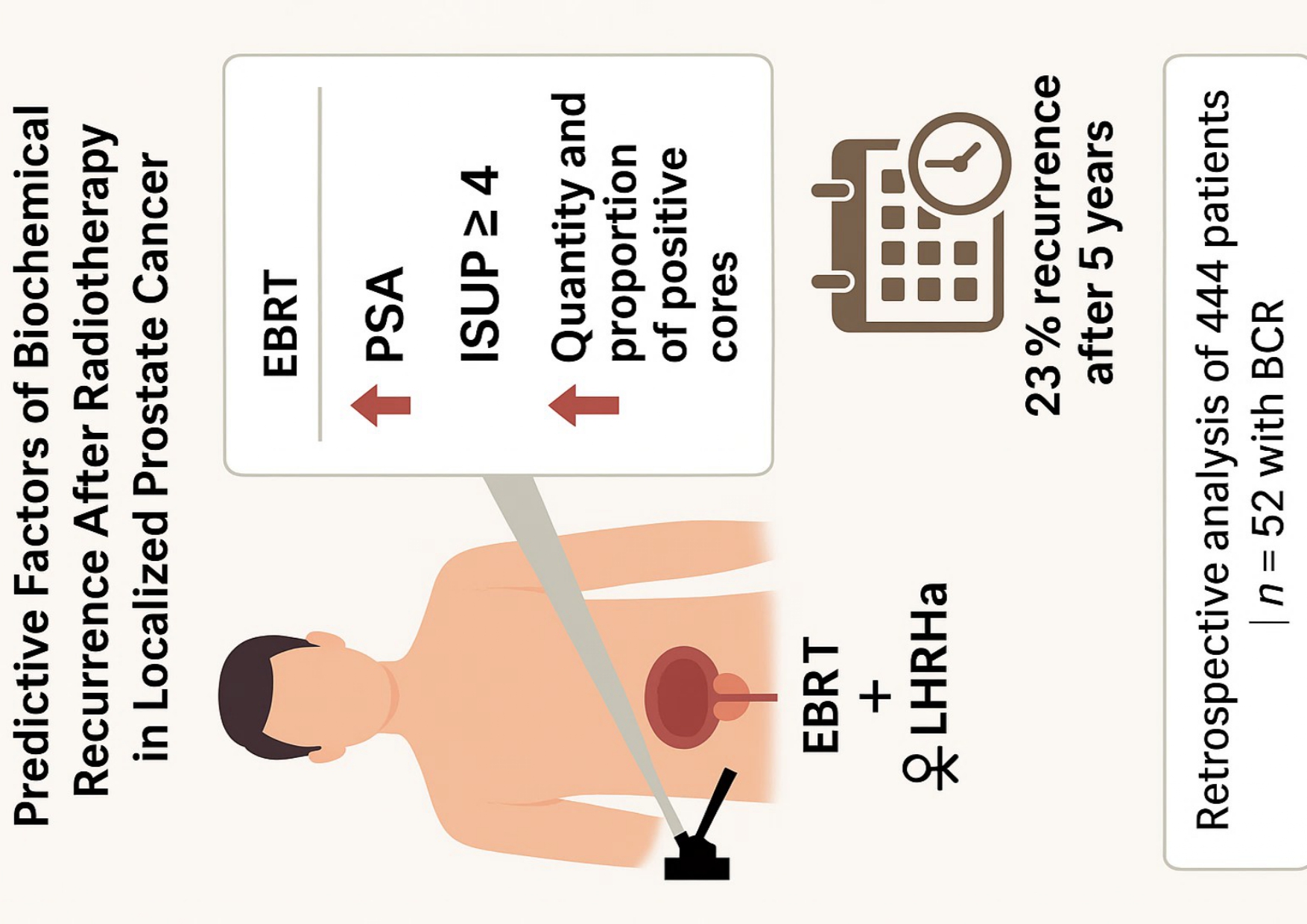

In this study, we retrospectively analyzed a cohort of patients with localized PC—without lymph-node involvement or distant metastasis—who underwent definitive treatment with EBRT ± ADT. Our objective was to identify clinical and pathological factors associated with BCR. We evaluated both traditional prognostic indicators and histopathological features obtained from diagnostic biopsies, as we believe these samples may hold more prognostic information than is currently incorporated into radiotherapy-based treatment decisions. Our aim was to explore whether integrating such data could improve risk-group stratification.

Furthermore, we assessed the patterns of recurrence, focusing on the anatomical sites and timing of recurrence events throughout follow-up, with the goal of providing evidence to optimize long-term surveillance strategies.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Patient Selection

We conducted a retrospective cohort study including 629 patients diagnosed with localized PC and treated exclusively with EBRT, with or without ADT: (Luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone [LHRH] agonists), between December 2013 and December 2019 at a single institution. A total of 444 patients met the eligibility criteria, which included a minimum follow-up of three years and at least four post-treatment PSA assessments. All cases were reviewed by a multidisciplinary tumor board, and written informed consent was obtained from all participants. The study was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Clinical Research Ethics Committee of Hospital Universitario de Terrassa (approval code: 02-21-100-020). The study is also registered under ClinicalTrials.gov identifier NCT06092918.

2.2. Risk Stratification

Patients were categorized into three risk groups based on established criteria:

Low-risk: International Society of Urological Pathology (ISUP)Grade 1, PSA <10 ng/mL, and clinical stage T1–T2a.

Intermediate-risk: ISUP Grade 2–3, PSA 10–20 ng/mL, or clinical stage T2b–T2c.

High-risk: ISUP Grade 4–5, PSA >20 ng/mL, or clinical stage ≥T3a.Patients classified as high-risk—or intermediate-risk with a Gleason Score (GS) pattern of 4 + 3 (ISUP 3)—underwent staging with axial computed tomography (CT) combined with either whole-body bone scintigraphy or a PET/CT scan using [^18F]-choline, in order to exclude pelvic or distant metastases. [^18F]-choline PET/CT and [^68Ga]-PSMA PET/CT were employed at the time of BCR, depending on availability and institutional protocol.

2.3. Technical Parameters of Radiotherapy Planning and Treatment

RT planning was conducted using CT-based simulation with 3 mm slice thickness for accurate delineation of target volumes and organs at risk. Patients were treated with one of three techniques: three-dimensional conformal radiotherapy (3D-CRT), intensity-modulated radiotherapy (IMRT), or volumetric-modulated arc therapy (VMAT), delivered in either normofractionated or hypofractionated schedules. Specifically, 3D-CRT was delivered using six-field plans with 15 MV or a combination of 6 MV and 15 MV photon beams; IMRT was implemented as step-and-shoot plans using five to seven 6 MV fields; and VMAT employed one or two full arcs with 6 MV photons. Image guidance consisted of weekly portal imaging for 3D-CRT and daily cone-beam CT for IMRT and VMAT.

For target volume delineation, when the clinical target volume (CTV) included only the prostate or the prostate and seminal vesicles (with the latter omitted in low-risk patients), an isotropic margin of 10 mm (for 3D-CRT) or 8 mm (for IMRT/VMAT) was used to define the planning target volume (PTV). In cases involving elective pelvic nodal irradiation, an isotropic margin of 7 mm was applied across all techniques. Pelvic lymph nodes were irradiated in all high-risk patients aged under 75 years and in intermediate-risk patients with a predicted nodal involvement risk greater than 15 %, as estimated by the Partin nomogram.

Regarding dose schedules, hypofractionated regimens consisted of either 2.5 Gray (Gy) per fraction to the prostate—with or without inclusion of the seminal vesicles—and an optional simultaneous dose of 1.8 Gy to the pelvic lymph nodes, or 3 Gy per fraction to the prostate and seminal vesicles alone, up to a total dose of 60 Gy. Normofractionated regimens were delivered as 2 Gy per fraction to a total dose of 78 Gy.

2.4. ADT (Androgen Deprivation Therapy)

LHRHa (luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone agonists) were administered according to international guidelines: 6 months for intermediate-risk patients and 18–36 months for high-risk patients, combined with oral antiandrogens during the first 30 days. Treatment began approximately two months prior to CT simulation.

2.5. PSA Monitoring and Definitions

Nadir PSA (nPSA) was the lowest level recorded after treatment. BCR was defined according to the Phoenix criteria: a rise of ≥2 ng/mL above the nPSA. PSA levels were monitored at 3, 6, and 12 months post-EBRT, and every 6 months thereafter.

2.6. Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were reported as means with standard deviations or medians with interquartile ranges (IQR, Q1–Q3) for continuous variables, and as absolute and relative frequencies for categorical variables. Group comparisons were performed using the Chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables. For continuous variables, Student’s t-test was applied when assumptions of normality and homogeneity of variances were met; otherwise, non-parametric tests were used.

Univariable analyses were first conducted to assess the association between each variable and BCR. Subsequently, a multivariable logistic regression model was constructed to identify independent predictors of BCR. Categorical variables with more than two levels were transformed into dummy variables. Model outputs included regression coefficients (estimates), standard errors, z-values, and p-values, indicating the strength and direction of association between each predictor and the outcome. All statistical analyses were performed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS), version 27 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). A p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

Of the 629 men recruited, 185 were excluded because of having less than 4 PSA determinations and/or less than 3 years of follow-up.

A total of 444 patients were included finally. The median age was 71 years (range 51–85), with a median follow-up of 72 months. Overall, 52 patients (11.7%) experienced BCR during follow-up. Baseline clinical and pathological characteristics are shown in

Table 1.

3.1. Predictors Factors

No statistically significant differences were observed in age at diagnosis between patients with and without BCR (median: 72 [range: 54–83] vs. 70 years [51–85], respectively; p = 0.355).

PSA levels at diagnosis were significantly higher in patients who developed BCR (median: 10.8 ng/mL; mean: 30.3 ng/mL) compared to those without recurrence (median: 9.3 ng/mL; mean: 12.9 ng/mL; p = 0.045).

Regarding the ISUP Grade Group, the cohort included 76 patients with ISUP grade 1, 255 with ISUP grades 2–3, and 113 with ISUP grades 4–5. A significantly higher proportion of high-grade tumors was observed in the BCR group (p = 0.011). Similarly, patients with BCR were more frequently classified as high clinical risk (61.5% vs. 42.6%; p = 0.035).

The majority of cases (91.4%) were cT2. Although cT3b lesions showed numerically more failures (18.4 %), MRI stage did not reach significance (p = 0.380). Similarly, no significant differences were found regarding the administration of exclusive EBRT, with a BCR rate of 13.3% among patients who did not receive ADT (p = 0.189), nor among those treated with ADT, who presented a BCR rate of 12.6% (p = 0.36).

A total of 19 recurrences were recorded among 114 patients treated with the oldest radiotherapy technique (3D-CRT), representing a recurrence rate of 16.7%, the highest among all techniques. This was followed by IMRT with 5 recurrences in 35 patients (14.3%) and VMAT with 28 recurrences in 295 patients (9.5%). However, no statistically significant differences were observed according to the radiotherapy technique employed (p = 0.242). Likewise, no significant differences were found according to the fractionation schedule (p = 0.119).

PNI was more prevalent among patients with recurrence, with 18 cases of BCR among 103 patients with PNI and 8 cases among 116 patients without it (p = 0.036).

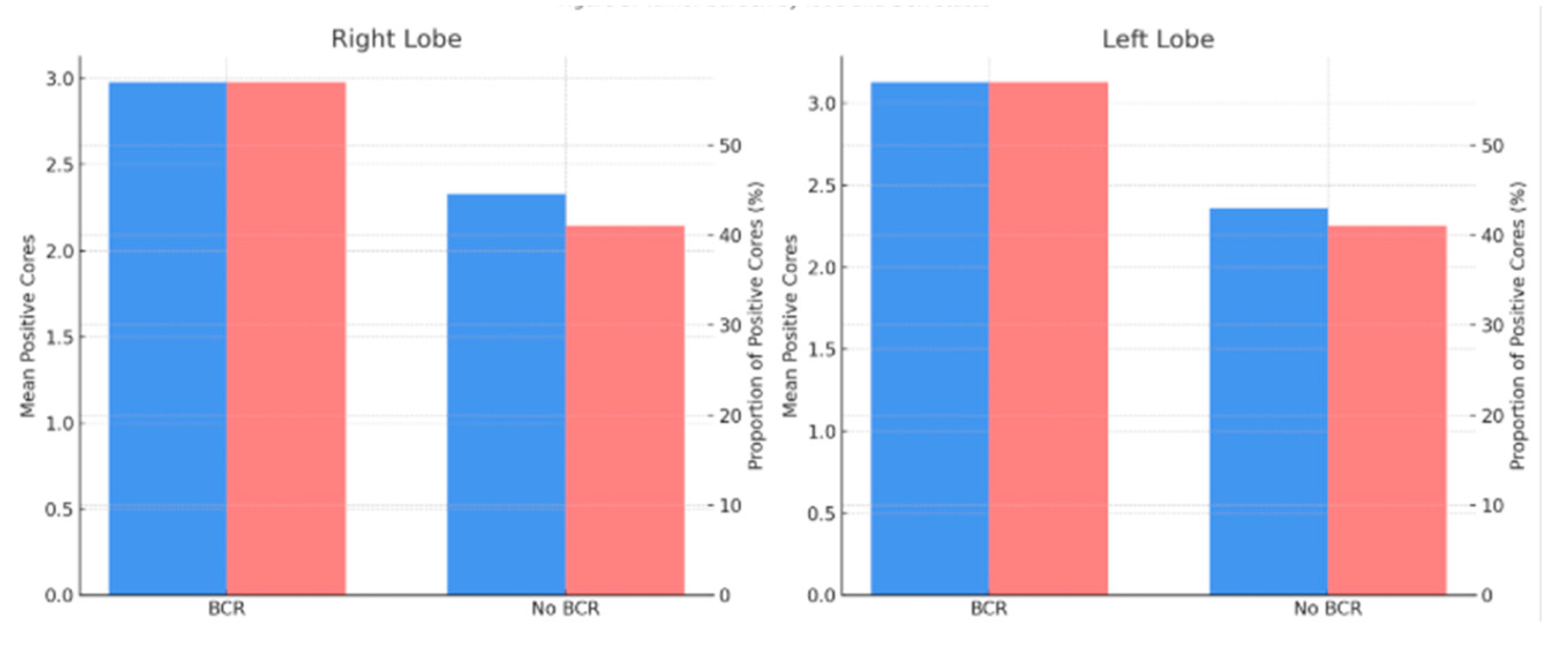

A higher tumor burden was observed in biopsy samples from patients with BCR, both in terms of the mean number of positive cores per lobe and the proportion of positive cores relative to the total number of sampled cores. The proportion of positive cores was consistently higher in the BCR group compared to the non-BCR group across both lobes (57% vs. 41%, respectively). Specifically, in the right lobe, the mean number of positive cores was 2.98 in the BCR group vs. 2.33 in the non-BCR group (

p = 0.014); in the left lobe, 3.13 vs. 2.36 (

p = 0.007); and for the total number of positive cores, 6.11 vs. 4.71 (

p = 0.01). The differences in proportions between groups were also statistically significant (right lobe:

p = 0.046; left lobe:

p = 0.048; total:

p = 0.005). (

Figure 1)

In the multivariable analysis, several independent factors remained statistically significantly associated with an increased risk of BCR.

PSA at diagnosis was confirmed as a significant predictor (OR: 1.01; 95% CI: 1.00–1.02; p = 0.05), indicating that higher PSA values are associated with an increased probability of recurrence, even after adjustment for other covariates.

Tumor burden in biopsy samples—expressed both as the absolute number and the proportion of positive cores—showed a strong and consistent association with BCR across all models. The number of positive cores in the right lobe (OR: 3.02; 95% CI: 1.25–7.32; p = 0.014), in the left lobe (OR: 2.70; 95% CI: 1.15–6.32; p = 0.022), and the total number of positive cores (OR: 8.26; 95% CI: 2.36–28.94; p = 0.0009) were all independently associated with a higher risk of recurrence.

Likewise, histological grade ISUP ≥ 4 was confirmed as a significant predictor in the adjusted model (OR: 2.25; 95% CI: 1.05–4.84; p = 0.036), reinforcing its prognostic value beyond the univariable analysis.

In contrast, the presence of PNI, although previously associated in the univariable analysis, did not reach statistical significance in the multivariable model (OR: 2.58; 95% CI: 1.02–6.81;

p = 0.234), suggesting that its effect may be mediated or attenuated by other variables included in the model or possibly influenced by missing data. A summary of this analysis is presented in

Table 2.

3.2. Recurrence Patterns

Among the patients with biochemical recurrence, the extension study was negative in 12 cases. In 9 patients, recurrence was confined to the prostate only.

A total of 9 patients presented with M1a-exclusive disease (extra pelvis node metastases), while 6 patients had osseous-only metastases, and 5 showed exclusive pelvic nodal involvement.

The remaining 11 patients exhibited a mixed pattern of recurrence, involving two or more of the above sites.

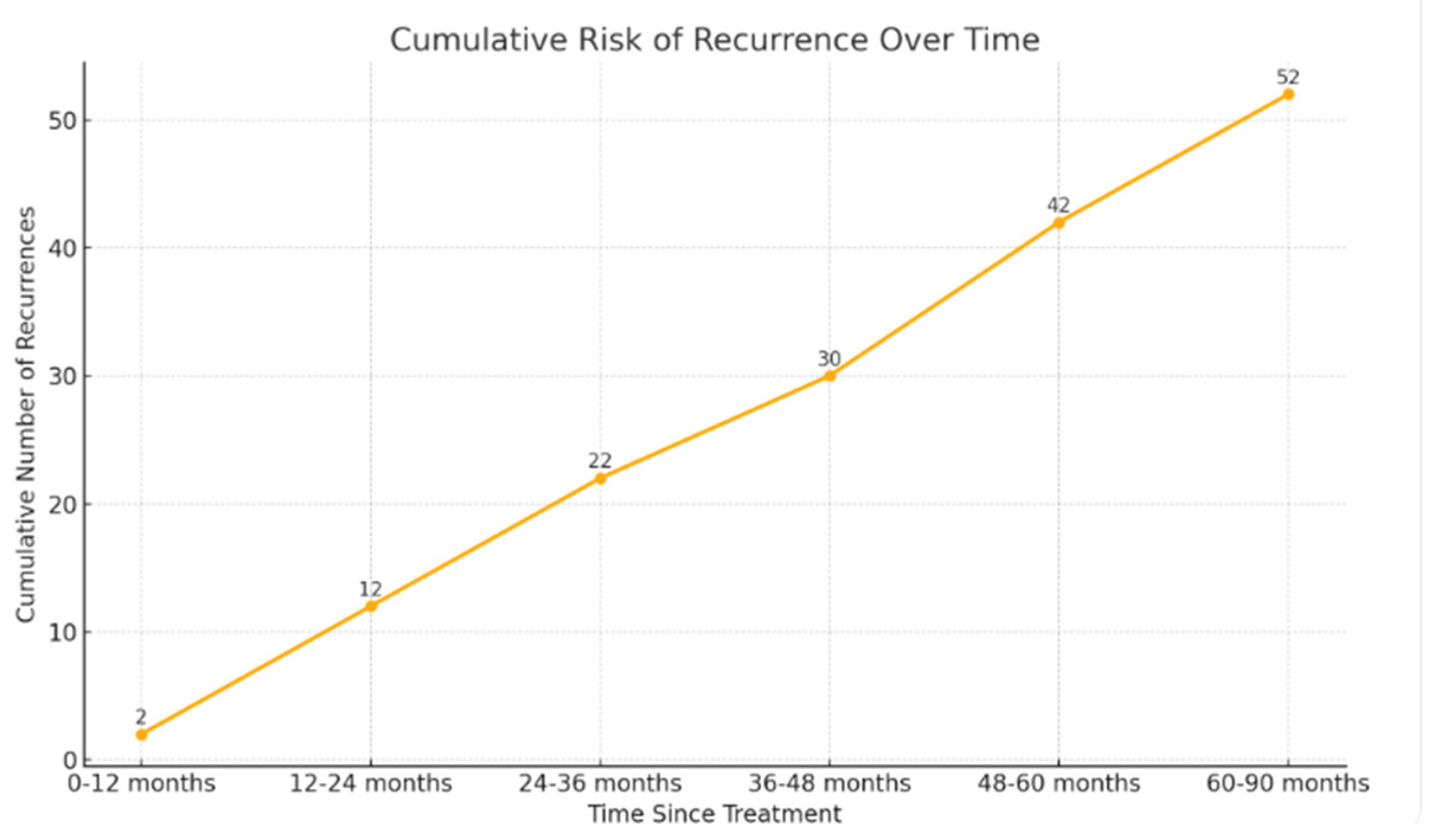

3.3. Time of Recurrence

Only two BCR (4.4%) occurred within the first year after treatment completion. In the second and third years, relapses were observed in 10 patients each (21.7% per year). Eight patients (17.4%) relapsed during the fourth year, and 12 (26.1%) during the fifth year. In total, approximately 20% of BCR occurred more than five years after RT.

Figure 2

4. Discussion

In this retrospective study, we analyzed a cohort of 444 patients with localized PC, without nodal involvement or distant metastases at the time of diagnosis, treated with modern RT techniques and standardized protocols regarding the indication and duration of ADT. The main objective was to confirm and/or identify clinical, pathological, and treatment-related factors that may influence the prediction of BCR, with the aim of enabling a more individualized risk stratification within the currently established risk groups. To this end, we explored the prognostic relevance of key variables such as baseline PSA, PNI, GS/ISUP, and the number- percentage of positive biopsy cores, as well as the timing and patterns of recurrence.

4.1. Prostate-Specific Antigen (PSA)

PSA remains one of the fundamental pillars in the diagnosis, risk stratification, and follow-up of PC. Baseline PSA at diagnosis has consistently been shown to be an independent predictor of BCR in multiple studies involving both surgical and RT-treated cohorts [

20,

21,

22]. In our cohort, patients who developed BCR exhibited twice the mean PSA values compared to those without recurrence. Importantly, PSA remained statistically significant in the multivariable analysis, underscoring its prognostic value even after adjusting for other variables.

There is a proportional relationship between PSA levels and intraprostatic tumor burden, which may partially explain its predictive value for BCR observed in our cohort. However, exceptions do occur. Well-differentiated tumors, for instance, may not produce significantly elevated PSA levels, making the GS score essential for proper interpretation in such cases [

23]. Conversely, elevated PSA levels may sometimes reflect false positives, most often due to lower urinary tract infections or other benign conditions [

24].

PSA is a reliable, accessible, and quantifiable biomarker, but its use should always be complemented by prostate biopsy for diagnosis, and by appropriate imaging for staging or evaluation of recurrence.

Among the numerous studies assessing PSA as a prognostic factor, the retrospective study conducted at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, published in 2010, stands out. Despite its retrospective design, the study employed modern radiation doses (>81 Gy) and found pretreatment PSA to be an independent predictor of BCR. Specifically, each 1 ng/mL increase in baseline PSA was associated with a 2% increase in the risk of biochemical failure (HR: 1.02; 95% CI: 1.01–1.03;

p = 0.0004) [

25].

4.2. Perineural Invasion (PNI)

In our cohort, the presence of PNI was more frequently observed in patients who developed BCR, reaching statistical significance in the univariable analysis (p = 0.036). However, this association did not remain significant in the multivariable logistic regression model (p = 0.234), suggesting that its effect may be attenuated by other covariates or limited by incomplete pathological reporting.

The biological relevance of PNI has been described in various solid tumors, including PC, where tumor cell infiltration of perineural spaces is thought to facilitate local tumor spread [

26]. Several mechanistic hypotheses support its association with more aggressive behavior, including enhanced cellular proliferation and survival within the perineural niche [

27,

28].

Although PNI is widely recognized as a poor prognostic factor in surgical series [

29], its role in patients treated with radiotherapy remains controversial. Some studies and pooled analyses suggest a potential association with BCR in this setting, yet evidence remains inconsistent [

30,

31]. This uncertainty may stem from heterogeneous definitions of PNI, variability in biopsy sampling, and limited quantification (e.g., percentage of nerves involved, number of foci).

In our study, PNI was not reported in nearly half of the biopsy reports, limiting the power of the multivariable analysis and reinforcing the need for standardized and systematic PNI documentation in pathology assessments. While our findings suggest that PNI may have prognostic value in radiotherapy-treated patients, further prospective studies with complete reporting are needed to clarify its independent contribution.

4.3. Positive Core Number-Percentage

The percentage of positive biopsy cores serves as an indirect marker of tumor burden or overall disease extent within the prostate, and therefore, it is expected that higher values correlate with an increased risk of BCR [

32,

33].

In our cohort, both the absolute number and the proportion of positive biopsy cores—whether analyzed by lobe or in total—were significantly associated with BCR. Patients who developed BCR had a higher mean number of positive cores in both lobes (right lobe: 2.98 vs. 2.33; left lobe: 3.13 vs. 2.36), as well as a greater proportion of positive cores (57% vs. 41%).

These associations remained significant in the multivariable logistic regression model. The total number of positive cores showed the strongest association with recurrence (OR: 8.25; 95% CI: 2.36–28.94; p = 0.009). Positive cores in the right and left lobes were also independently associated with BCR (OR: 3.04; 95% CI: 1.25–7.32; p = 0.014 and OR: 2.69; 95% CI: 1.15–6.32; p = 0.022, respectively). These findings confirm tumor burden, as measured by positive cores, as a robust and independent predictor of recurrence.

The proportion of positive cores was also remarkably consistent across lobes (57% in the BCR group vs. 41% in non-BCR), supporting its relevance as a global surrogate for intraprostatic tumor extent.

Although this variable is not routinely incorporated into standard risk models [

34], its consistent and independent association with recurrence in our study suggests that the positive core percentage offers prognostic value beyond traditional indicators such as PSA, Gleason score, and clinical T stage.

Prior studies have also supported the prognostic utility of this marker. Kestin et al. (2002) were among the first to demonstrate the predictive role of positive core percentage in a cohort of 160 patients treated with EBRT and high-dose-rate brachytherapy. They reported a BCR rate below 7% in patients with <33% positive cores, compared to 25% in those with >66% [

35]. Similarly, D’Amico et al. (2004) found that ≥50% positive cores significantly increased prostate cancer–specific mortality in patients with low- or intermediate-risk disease, leading to the recommendation of treatment intensification [

36].

Despite these findings, positive core percentage has not yet been systematically integrated into widely used prognostic models—particularly in radiotherapy-based cohorts. Our results support its inclusion in modern risk stratification frameworks, especially in the context of contemporary EBRT strategies.

4.4. Gleason Score (GS) - ISUP Grade

Histological grading based on the GS, introduced in the 1960s, remains the most widely established predictor of prostate cancer aggressiveness [

37]. Although the system has undergone multiple refinements over time, its core principle persists: higher GS scores reflect less differentiated tumor architecture, which is associated with primary tumors that are more difficult to eradicate—either by surgery or RT—and a higher likelihood of distant metastasis [

38,

39,

40].

In our cohort, the GS score was confirmed as a relevant predictor of BCR following definitive radiotherapy. In univariable analysis, stratification into three groups (G1: 3+3; G2: 3+4/4+3; G3: ≥4+4) showed a significant association with BCR risk (p = 0.011). This trend was sustained in multivariable analysis using separate categories, where group G3 exhibited a significantly higher risk compared to G1 and G2 (p = 0.037), while the joint model showed marginal significance (p = 0.067), due to interactions with other clinical variables.

These findings are consistent with large population-based studies, which used SEER data and identified the GS score as an independent predictor of both cancer-specific and overall survival in high-risk patients [

38]. Notably, a progressive increase in risk was observed with higher scores (HR 2.66 for GS 10 vs. GS 8). Similarly, current international guidelines (EAU, ASCO, NCCN) define patients with GS 8–10 as a high-risk subgroup in the context of biochemical recurrence [

5,

6,

7].

Taken together, these findings reinforce and confirm the robust prognostic value of the GS score as a cornerstone for initial risk stratification in PC.

4.5. Chronology of Recurrence

A particularly noteworthy finding was that 23% of biochemical recurrences occurred more than five years after the completion of radiotherapy. This observation reinforces two key points. First, the need for prolonged follow-up, even in patients who remain disease-free during the initial years after treatment [

41,

42]. Second, it highlights the advantage of PSA as a robust, cost-effective, and widely accessible biomarker for long-term monitoring.

However, we believe that PSA kinetics alone are insufficient and should be interpreted in conjunction with appropriate initial clinical risk stratification, as the likelihood of recurrence is influenced by pre-treatment clinicopathological features and treatment-related variables. This underscores the importance of early identification of patients at higher risk of biochemical recurrence, enabling targeted surveillance and helping to prevent unnecessary overburdening of clinical services.

4.6. Limitations and Future Directions

This study has several limitations, including its retrospective, single-center design, and incomplete reporting of certain pathological variables—most notably perineural invasion (PNI). Treatment heterogeneity and the lack of molecular profiling further limit the generalizability of the findings.

As a future step, we aim to construct a predictive model for biochemical recurrence (BCR) incorporating the clinical and pathological variables found to be independently associated in this cohort. Prospective validation and integration of emerging biomarkers will be essential to refine risk stratification and support personalized follow-up strategies.

5. Conclusions

Biochemical recurrence in localized prostate cancer after radiotherapy is significantly associated with higher PSA at diagnosis, higher Gleason score, presence of perineural invasion, and increased proportion of positive biopsy cores. These findings support the integration of detailed biopsy data into recurrence risk assessment.

The identification and understanding of these prognostic factors can guide decision-making prior to treatment and support individualized follow-up strategies in patients undergoing curative-intent radiotherapy for prostate cancer.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, [Nicolas Feltes Benitez]; methodology, [Esther Jovell-Fernandez]; validation, []Esther Jovell-Fernandez; formal analysis, [Author 3]; investigation, [Author 1], [Author 2]; data curation, [Author 2]; writing—original draft preparation, [Author 1]; writing—review and editing, [Author 1], [Author 2], [Author 3]; visualization, [Author 3]; supervision, [Author 2]; project administration, [Author 1]. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Clinical Research Ethics Committee of the of Hospital Universitario de Terrassa (approval code: 02-21-100-020). The study is also registered under ClinicalTrials.gov identifier NCT06092918.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

| PSA |

Prostate-Specific Antigen |

| BCR |

Biochemical Recurrence |

| PC |

Prostate Cancer |

| GY |

Gray |

| EBRT |

External-Beam Radiotherapy |

| RT |

Radiotherapy |

| ADT |

Androgen-Deprivation Therapy |

| LHRH |

Luteinizing Hormone-Releasing Hormone |

| MRI |

Magnetic Resonance Imaging |

| PNI |

Perineural Invasion |

| GS |

Gleason Score |

| OR |

Odds Ratio |

| CI |

Confidence Interval |

| IQR |

Interquartile Range |

| ISUP |

International Society of Urological Pathology (ISUP) |

| PSMA-PET |

Prostate-Specific Membrane Antigen Positron-Emission Tomograph |

References

- Bray F, Laversanne M, Sung H, et al. Global cancer statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2024;74(3):229–263. [CrossRef]

- Epstein JI, Walsh PC, Carmichael M, Brendler CB. Pathologic and clinical findings to predict tumor extent of nonpalpable (stage T1c) prostate cancer. Am J Surg Pathol. 2005;29(2):200–206. [CrossRef]

- Kang DE, Fitzsimons NJ, Presti JC Jr, Gill H, Brooks JD, Colella DV. Risk stratification of men with clinically localized prostate cancer: contribution of tumor volume, grade and location. J Urol. 2004;171(4):1479–1484. [CrossRef]

- D’Amico AV, Whittington R, Malkowicz SB, et al. Biochemical outcome after radical prostatectomy, external beam radiation therapy, or interstitial radiation therapy for clinically localized prostate cancer. JAMA. 1998;280(11):969–974. [CrossRef]

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology: Prostate Cancer. Version 2.2025. 2025.

- Cornford P, van den Bergh RCN, Briers E, Van den Broeck T, Brunckhorst O, Darraugh J, et al. EAU-EANM-ESTRO-ESUR-ISUP-SIOG Guidelines on Prostate Cancer-2024 Update. Part I: Screening, Diagnosis, and Local Treatment with Curative Intent. Eur Urol. 2024;86(2):148–163. [CrossRef]

- Fossati N, Briganti A, Cornford P, et al. European Association of Urology guidelines on prostate cancer: novel insights and clinical recommendations. Eur Urol. 2023;84(1):51–62.

- Dinis Fernandes C, Dinh CV, Walraven I, Heijmink SW, Smolic M, van Griethuysen JJM, et al. Biochemical recurrence prediction after radiotherapy for prostate cancer with T2w magnetic resonance imaging radiomic features. Phys Imaging Radiat Oncol. 2018;7:9–15. [CrossRef]

- Freedland SJ, Gerber L, Reid J, Welbourn W, Tikishvili E, Park J, et al. Prognostic utility of cell cycle progression score in men with prostate cancer after primary external beam radiation therapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2013;86(5):848–853. [CrossRef]

- Tosoian JJ, Chappidi M, Feng Z, Humphreys EB, Han M, Pavlovich CP, et al. Prediction of pathological stage based on clinical stage, serum prostate-specific antigen, and biopsy Gleason score: Partin Tables in the contemporary era. BJU Int. 2017;119(5):676–683. [CrossRef]

- Stephenson AJ, Scardino PT, Eastham JA, Bianco FJ Jr, Dotan ZA, Fearn PA, et al. Preoperative nomogram predicting the 10-year probability of prostate cancer recurrence after radical prostatectomy. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2006;98(10):715–717. [CrossRef]

- Herr DJ, Elliott DA, Duchesne G, Stensland KD, Caram MEV, Chapman C, et al. Outcomes after definitive radiation therapy for localized prostate cancer in a national health care delivery system. Cancer. 2023;129(20):3326–3333. [CrossRef]

- Kishan AU, Sun Y, Hartman H, Pisansky TM, Bolla M, Neven A, et al. Androgen deprivation therapy use and duration with definitive radiotherapy for localised prostate cancer: an individual patient data meta-analysis. Lancet Oncol. 2022;23(2):304–316. [CrossRef]

- Dearnaley D, Syndikus I, Mossop H, Khoo V, Birtle A, Bloomfield D, et al. Conventional versus hypofractionated high-dose intensity-modulated radiotherapy for prostate cancer: 5-year outcomes of the randomised, non-inferiority, phase 3 CHHiP trial. Lancet Oncol. 2016;17(8):1047–1060. [CrossRef]

- Roach M 3rd, Hanks G, Thames H Jr, Schellhammer P, Shipley WU, Sokol GH, et al. Defining biochemical failure following radiotherapy with or without hormonal therapy in men with clinically localized prostate cancer: recommendations of the RTOG-ASTRO Phoenix Consensus Conference. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2006;65(4):965–974. [CrossRef]

- van Altena, E.J.E.; Jansen, B.H.E.; Korbee, M.L.; Knol, R.J.J.; Luining, W.I.; Nieuwenhuijzen, J.A.; Oprea-Lager, D.E.; van der Pas, S.L.; van der Voort van Zyp, J.R.N.; van der Zant, F.M.; van Leeuwen, P.J.; Wondergem, M.; Vis, A.N. Prostate-Specific Membrane Antigen Positron Emission Tomography before Reaching the Phoenix Criteria for Biochemical Recurrence of Prostate Cancer after Radiotherapy: Earlier Detection of Recurrences. Eur. Urol. Oncol. 2025, 8, 417–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou J, Gou Z, Wu R, Yuan Y, Yu G, Zhao Y, et al. Comparison of PSMA-PET/CT, choline-PET/CT, NaF-PET/CT, MRI, and bone scintigraphy in the diagnosis of bone metastases in patients with prostate cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Skelet Radiol. 2019;48:1915–1924. [CrossRef]

- Chi KN, Agarwal N, Bjartell A, Chung BH, Pereira de Santana Gomes AJ, Given R, et al. Apalutamide for metastatic, castration-sensitive prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2019;381:13–24. [CrossRef]

- Davis ID, Martin AJ, Stockler MR, et al. Enzalutamide with standard first-line therapy in metastatic prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2019;381:121–131. [CrossRef]

- Dave P, Carlsson SV, Watts K. Randomized trials of PSA screening. Urol Oncol. 2025;43(1):23–28. [CrossRef]

- Hugosson J, et al. A 16-yr follow-up of the European randomized study of screening for prostate cancer. Eur Urol. 2019;76(1). [CrossRef]

- Cuzick, J. Prevention and early detection of prostate cancer. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15(11). [CrossRef]

- Zhou, M. High-grade prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia, PIN-like carcinoma, ductal carcinoma, and intraductal carcinoma of the prostate. Mod Pathol. 2018;31(S1):S71–S79. [CrossRef]

- Merriel SWD, Funston G, Hamilton W, et al. Prostate cancer in primary care. Adv Ther. 2018;35(9):1285–1294. [CrossRef]

- Fuchsjäger MH, Pucar D, Zelefsky MJ, Zhang Z, Mo Q, Ben-Porat LS, et al. Predicting post-external beam radiation therapy PSA relapse of prostate cancer using pretreatment MRI. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2010;78(3):743–750. [CrossRef]

- Jobling P, Pundavela J, Oliveira SM, Roselli S, Walker MM, Hondermarck H. Nerve–cancer cell cross-talk: a novel promoter of tumor progression. Cancer Res. 2015;75(9):1777–1781. [CrossRef]

- Niu Y, Förster S, Muders M. The role of perineural invasion in prostate cancer and its prognostic significance. Cancers (Basel). 2022;14:4065. [CrossRef]

- Ayala GE, Dai H, Ittmann M, Li R, Powell M, Frolov A, et al. Growth and survival mechanisms associated with perineural invasion in prostate cancer. Cancer Res. 2004;64(17):6082–6090. [CrossRef]

- Zhang LJ, Wu B, Zha ZL, Qu W, Zhao H, Yuan J, et al. Perineural invasion as an independent predictor of biochemical recurrence in prostate cancer following radical prostatectomy or radiotherapy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Urol. 2018;18:5. [CrossRef]

- Harnden P, Shelley MD, Clements H, Coles B, Tyndale-Biscoe RS, Naylor B, et al. The prognostic significance of perineural invasion in prostatic cancer biopsies: a systematic review. Cancer. 2007;109(1):13–24. [CrossRef]

- Zhang LJ, Wu B, Zha ZL, et al. Perineural invasion as an independent predictor of biochemical recurrence in prostate cancer following radical prostatectomy or radiotherapy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Urol. 2018;18:5. [CrossRef]

- Ozawa Y, Nohara S, Nakamura K, Hattori S, Yagi Y, Nishiyama T, et al. Fewer systematic prostate core biopsies in clinical stage T1c prostate cancer leads to biochemical recurrence after brachytherapy as monotherapy. Prostate. 2024;84(5):502–510. [CrossRef]

- Oikawa M, Tanaka T, Narita T, Noro D, Iwamura H, Tobisawa Y, et al. Impact of the proportion of biopsy positive core in predicting biochemical recurrence in patients with pathological pT2 and negative resection margin status after radical prostatectomy. Pathol Oncol Res. 2020;26(4):2115–2121. [CrossRef]

- Berney DM, Beltran L, Sandu H, Soosay G, Møller H, Scardino P, et al. The percentage of high-grade prostatic adenocarcinoma in prostate biopsies significantly improves on Grade Groups in the prediction of prostate cancer death. Histopathology. 2019;75(4):589–597. [CrossRef]

- Kestin LL, Goldstein NS, Vicini FA, Martinez AA. Percentage of positive biopsy cores as predictor of clinical outcome in prostate cancer treated with radiotherapy. J Urol. 2002;168(5):1994–1999. [CrossRef]

- D’Amico AV, Renshaw AA, Cote K, Hurwitz M, Beard C, Loffredo M, et al. Impact of the percentage of positive prostate cores on prostate cancer-specific mortality for patients with low or favorable intermediate-risk disease. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22(18):3726–3732. [CrossRef]

- Gleason DF, Mellinger GT. Prediction of prognosis for prostatic adenocarcinoma by combined histological grading and clinical staging. J Urol. 1974;111(1):58–64. [CrossRef]

- Cao G, Li Y, Wang J, Wu X, Zhang Z, Zhanghuang C, et al. Gleason score, surgical and distant metastasis are associated with cancer-specific survival and overall survival in middle-aged high-risk prostate cancer: a population-based study. Front Public Health. 2022;10:1028905. [CrossRef]

- Safdieh JJ, Schwartz D, Weiner JP, Nwokedi E, Schreiber D. The need for more aggressive therapy for men with Gleason 9-10 disease compared to Gleason ≤ 8 high-risk prostate cancer. Tumori. 2016;102:168–173. [CrossRef]

- Epstein, JI. An update of the Gleason grading system. J Urol. 2010;183(2):433–440. [CrossRef]

- Ward JF, Blute ML, Slezak J, Bergstralh EJ, Zincke H. The long-term clinical impact of biochemical recurrence of prostate cancer 5 or more years after radical prostatectomy. J Urol. 2003;170(5):1872–1876. [CrossRef]

- Benchikh El Fegoun A, Villers A, Moreau JL, Richaud P, Rebillard X, Beuzeboc P. PSA et suivi après traitement du cancer de la prostate. Prog Urol. 2008;18(3):137–144. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).