Submitted:

31 July 2025

Posted:

01 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

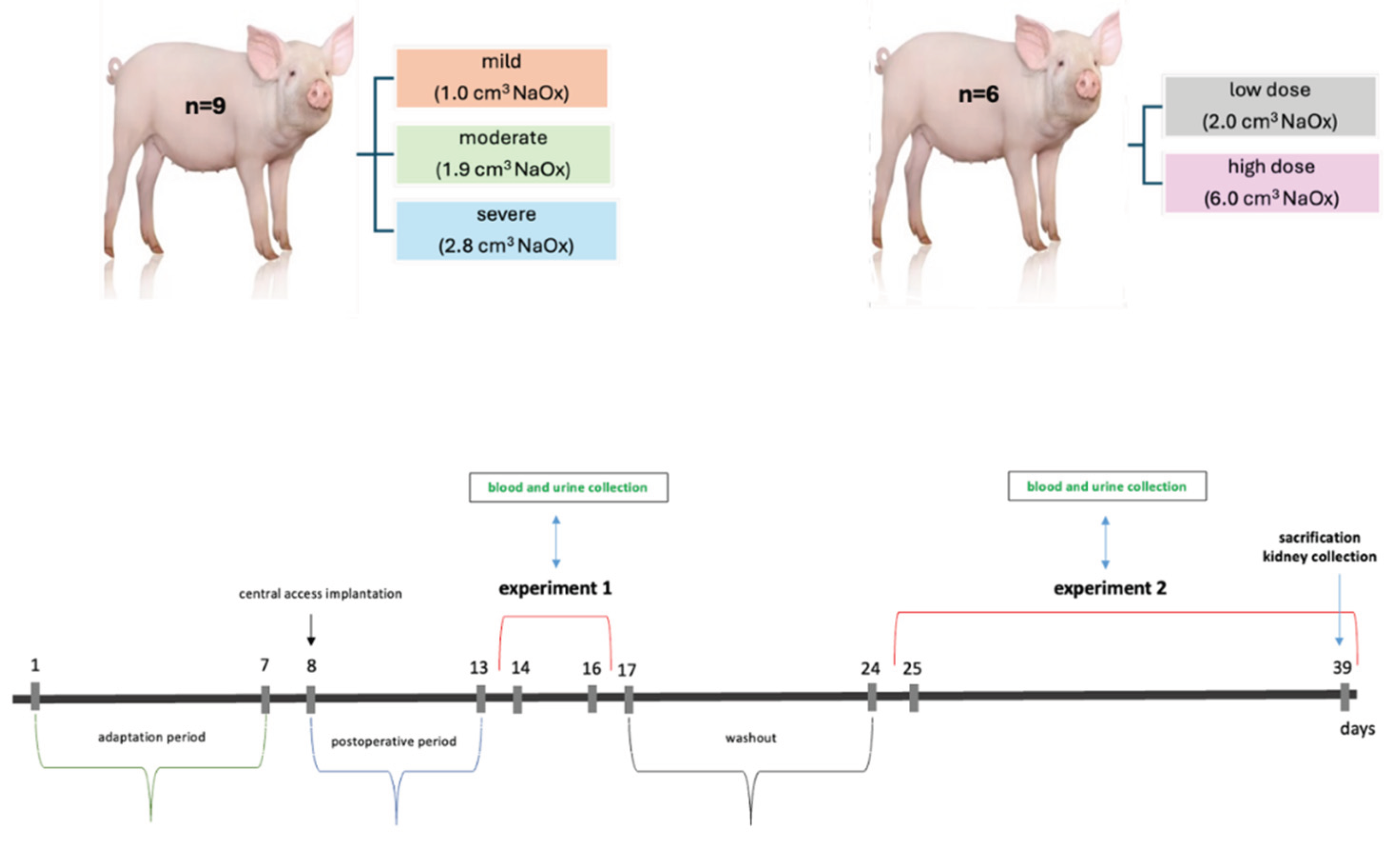

2.1. In Vivo Model of Mild, Moderate and Severe Hyperoxalemia

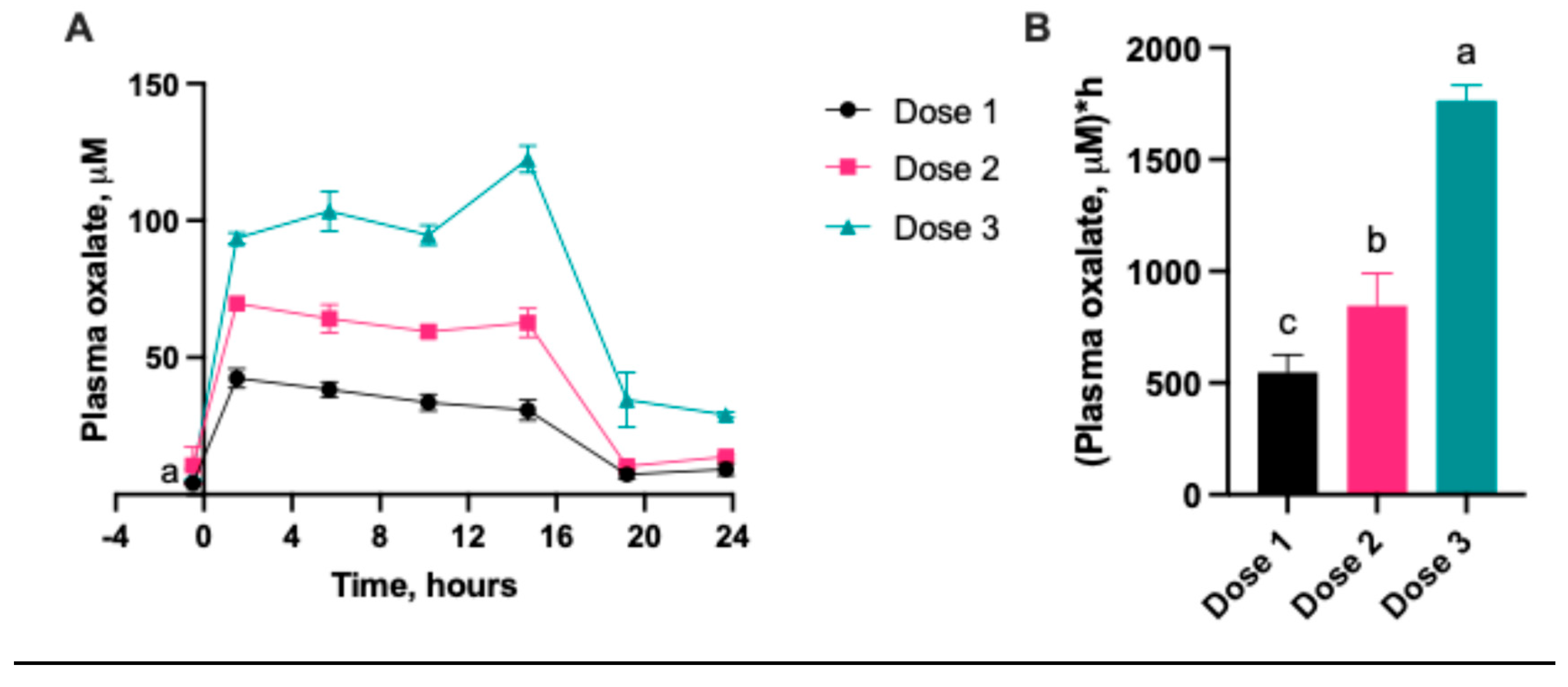

2.1.1. Serum Oxalate Concentration

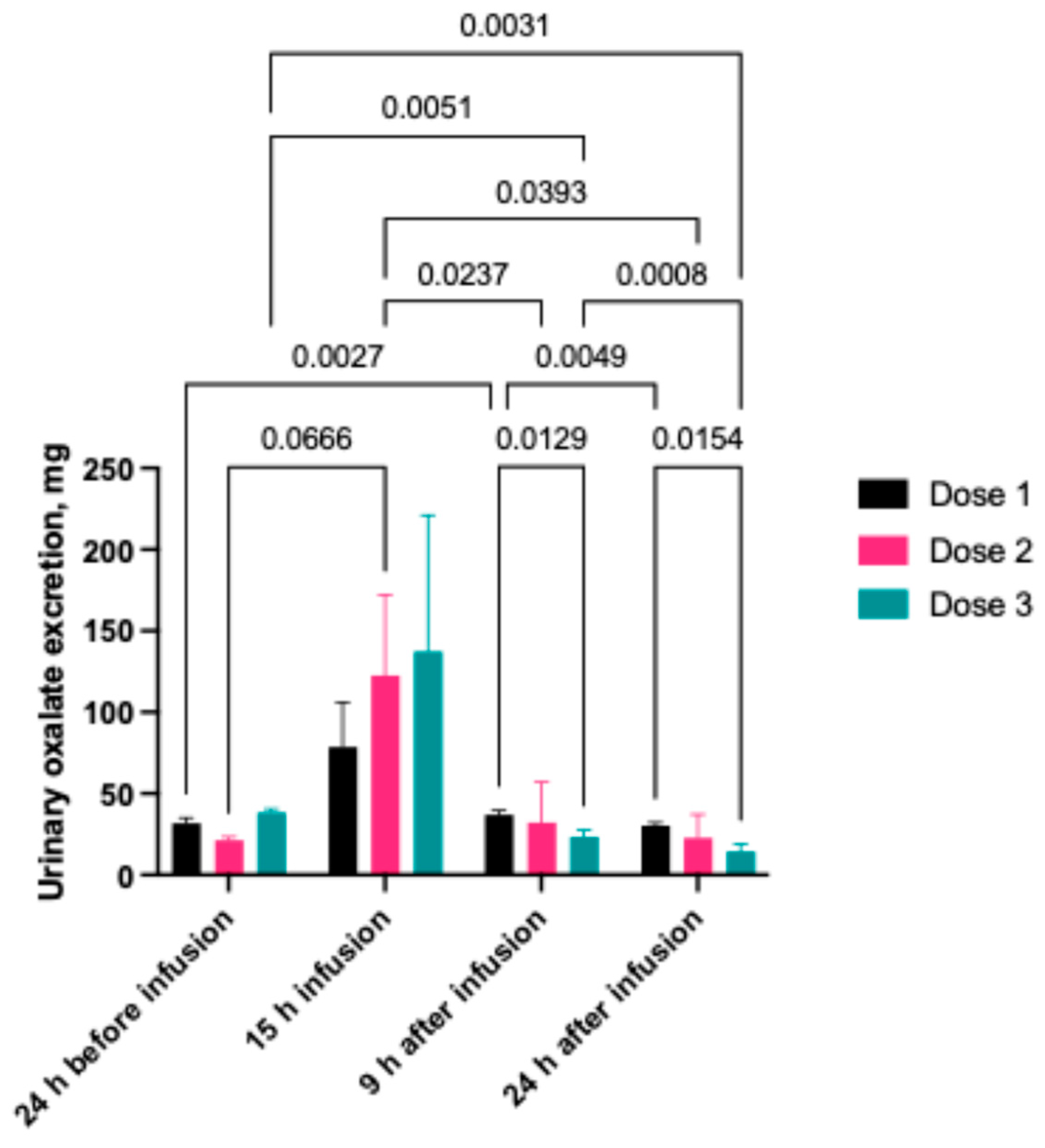

2.1.2. Urinary Oxalate Concentration

2.2. In Vivo Model of Chronic Hyperoxaluria

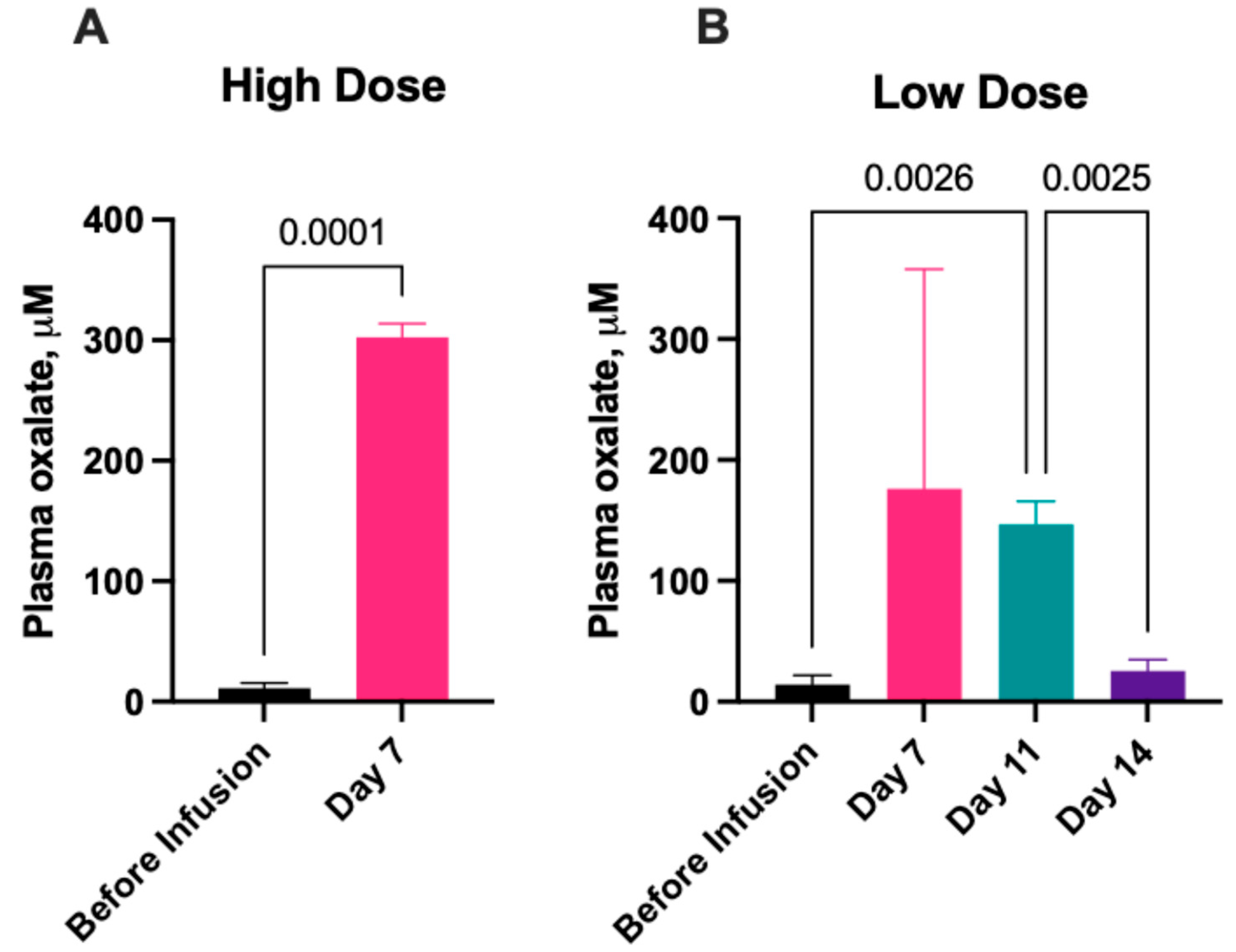

2.2.1. Serum Oxalate Concentration

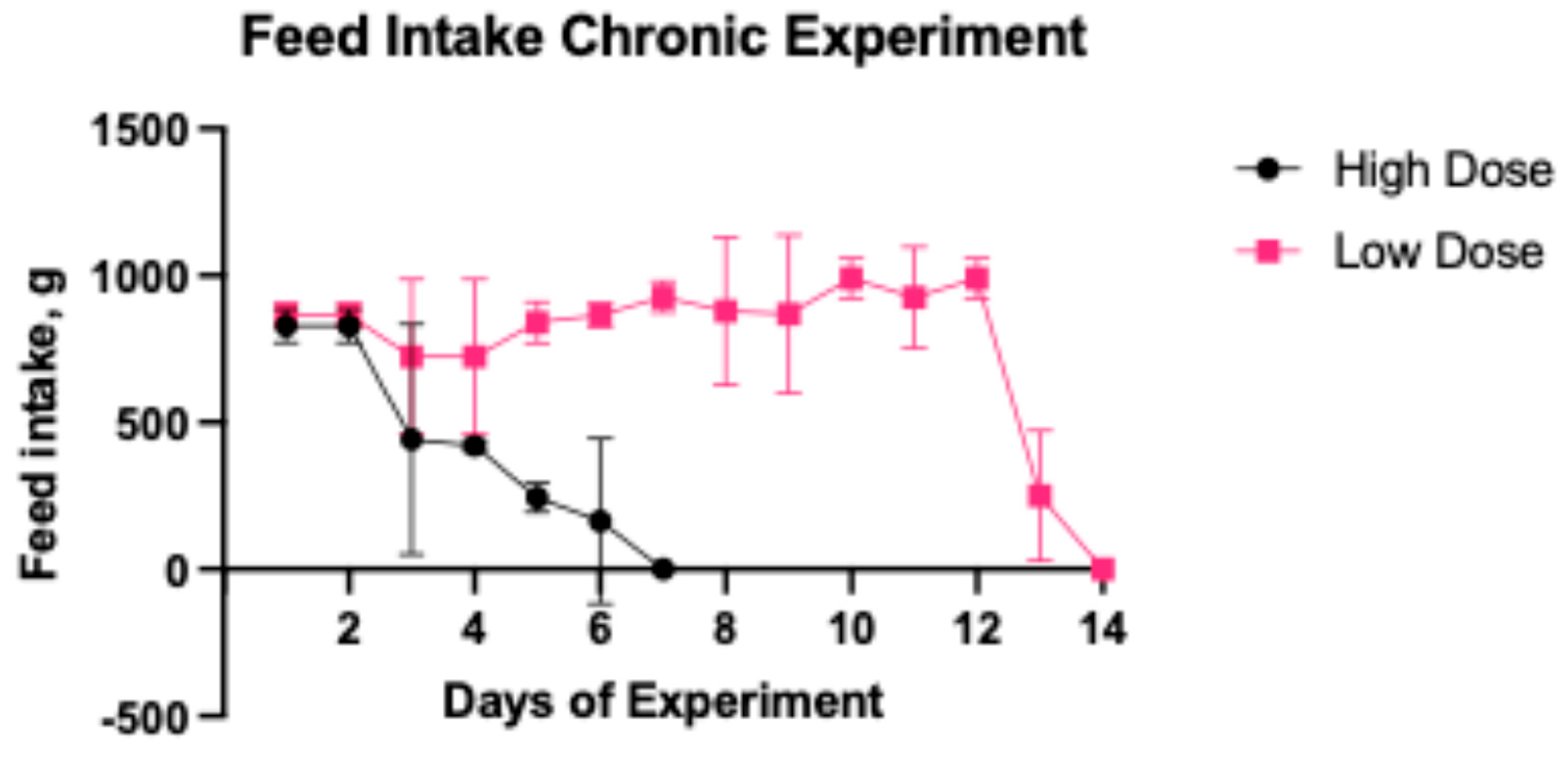

2.2.2. Daily Feed Intake

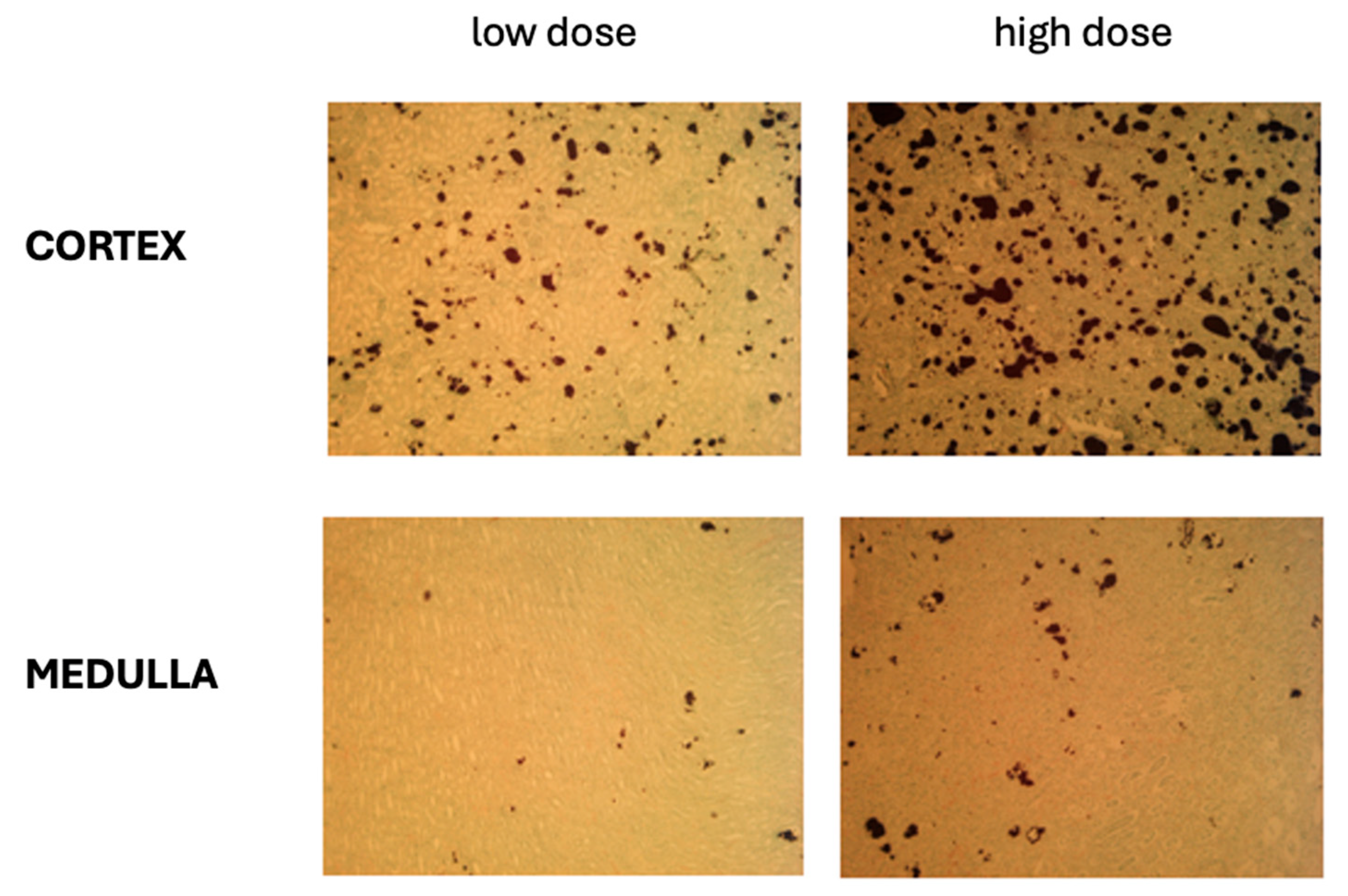

2.2.3. Oxalate Deposits in the Kidney Tissues

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Animals, Housing Conditions, Surgical Procedures

4.1.1. Bioethics

4.1.2. Animals and Housing

4.1.3. Feed

4.1.4. Implantation of Central Access to the External Jugular Vein

4.2. Experimental Design and Sample Collection

4.2.1. Experiment 1 – Animal Model of Acute Hyperoxalemia

4.2.2. Experiment 2 – Animal Model of Chronic Hyperoxaluria

4.3. Ion Chromatography

4.4. Histological Evaluation of Kidneys

4.5. Statistical Analysis

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PH | Primary hyperoxaluria |

| CaOx | Calcium oxalate |

| CKD | Chronic kidney disease |

| KSD GFR NaOx EG HYP POx AKI ESRD |

Kidney stones Glomerular filtration rate Sodium oxalate Ethylene glycol Hydroxyproline Plasma oxalate concentration Acute kidney injury End-stage renal disease |

References

- Bhasin, B.; Ürekli, H.M.; Atta, M.G. Primary and secondary hyperoxaluria: Understanding the enigma. World Journal of Nephrology 2015, 6, 235–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Penniston, K.L.; Patel, S.R.; Schwahn, D.J.; Nakada, S.Y. Studies using a porcine model: what insights into human calcium oxalate stone formation mechanisms has this model facilitated?.Urolithiasis 45, 109–125 (2017). [CrossRef]

- De Araújo, L.; Costa-Pessoa, J. M.; de Ponte, M. C.; Oliveira-Souza, M. Sodium-oxalate induced acute kidney injury associated with glomerular and tubulointerstitial damage in rats. Frontiers in Physiology 2020, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meydan, N.; Barutca, S.; Caliskan, S.; Camsari, T. Urinary stone disease in diabetes mellitus. Scandinavian Journal of Urology and Nephrology 2003, 37, 64–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carbone, A.; Al Salhi, Y.; Tasca, A.; Palleschi, G.; Fuschi, A.; De Nunzio, C.; Mazzaferro, S.; Pastore, A.L. Obesity and kidney stone disease: a systematic review. Minerva Urology and Nephrology 2018, 70, 393–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waikar, S.S.; Srivastava, A.; Palsson, R.; Shafi, T.; Hsu, C.Y.; Sharma, K.; Lash, J.P.; Chen, J.; He, J.; Lieske, J.; Xie, D.; Zhang, X.; Feldman, H.I.; Curhan, G.C. Association of urinary oxalate excretion with the risk of chronic kidney disease progression. JAMA Internal Medicine 2019, 179, 542–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayer, J. A.; Carr, G.; Simmons, N.L. Nephrocalcinosis: molecular insights into calcium precipitation within the kidney. Clinical Science 2004, 106, 549–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, X.; Wan, J.; Xu, J.; Liu, C.; Zhong, M.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, S. Epidemiological trends of Urolithiasis at the Global, Regional, and national levels: a Population-based study. International Journal of Clinical Practice 2022, 202, 6807203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, J.; Narendrula, A.; El-Zawahry, A.; Sindhwani, P.; Ekwenna, O. Global trends in Incidence and Burden of Urolithiasis from 1990 to 2019: an analysis of global burden of Disease Study Data. European Urology Open Science 2022, 35, 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanstock, S.; Ferreira, D.; Adomat, H.; Eltit, F.; Wang, Q.; Othman, D.; Nelson, B.; Chew, B.; Miller, A.; Lunken, G.; Lange, D. A mouse model for the study of diet-induced changes in intestinal microbiome composition on renal calcium oxalate crystal formation. Urolithiasis 2025, 53, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanks, N.; Greek, R.; Greek, J. Are animal models predictive for humans? Philosophy, Ethics, and Humanities in Medicine 2009, 4, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagetti Filho, H.J.; Pereira-Sampaio, M.A.; Favorito, L.A.; Sampaio, F.J. Pig kidney: anatomical relationships between the renal venous arrangement and the kidney collecting system. The Journal of Urology 2008, 179, 1627–1630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giraud, S.; Favreau, F.; Chatauret, N.; Thuillier, R.; Maiga, S.; Hauet, T. Contribution of large pig for renal ischemia-reperfusion and transplantation studies: the preclinical model. BioMed Research International 2011, 2011, 532127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tzou, D.T.; Taguchi, K.; Chi, T.; Stoller, M.L. Animal models of urinary stone disease. International Journal of Surgery 2016, 36, 596–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verhulst, A.; Dehmel, B.; Lindner, E.; Akerman, M.E.; D’Haese, P.C. C. Oxalobacter formigenes treatment confers protective effects in a rat model of primary hyperoxaluria by preventing renal calcium oxalate deposition. Urolithiasis 2022, 50, 119–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crestani, T.; Crajoinas, R.O.; Jensen, L.; Dima, L.L.; Burdeyron, P.; Hauet, T.; Giraud, S.; Steichen, C. A sodium oxalate-rich diet induces chronić kidney disease and cardiac dysfunction in rats. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2021, 22, 9244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaplon, D.M.; Penniston, K.L.; Darriet, C.; Crenshaw, T.D.; Nakada, S.Y. Hydroxyproline-induced hyperoxaluria using acidified and traditional diets in the porcine model. Journal of Endourology 2010, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, S.R.; Finlayson, B.; Hackett, R.L. Histologic study of the early events in oxalate induces intranephronic calculosis. Investigative Urology 1979, 17, 199–202. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Khan, S.R.; Finlayson, B.; Hackett, R.L. Experimental calcium oxalate nephrolithiasis in the rat. Role of the renal papilla. The American Journal of Pathology 1982, 107, 59–69. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, S.R.; Shevock, P.N.; Hackett, R.L. Acute hyperoxaluria, renal injury and calcium oxalate urolithiasis. The Journal of Urology 1992, 147, 226–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robijn, S.; Hoppe, B.; Vervaet, B.A.; D’Haese, P.C.; Verhulst, A. Hyperoxaluria: a gut-kidney axis? Kidney International 2011, 80, 1146–1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knauf, F.; Velazquez, H.; Pfann, V.; Jiang, Z.; Aronson, P.S. Characterization of renal NaCl and oxalate transport in Slc26a6. American Journal of Physiology – Renal Physiology 2019, 01, 128–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fargue, S.; Wood, K.D.; Cirvelli, J.J.; Assimos, D.G.; Oster, R.A.; Knight, J. Endogenous oxalate synthesis and urinary oxalate excretion. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology 2023, 39, 1505–1507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoppe, B.; Kemper, M.J.; Bökenkamp, A.; Portale, A.A.; Cohn, R.A.; Langman, C.B. Plasma calcium-oxalate supersaturation in children with primary hyperoxaluria and end stage renal disease. Kidney International 1999, 56, 268–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoppe, B.; Beck, B.B.; Milliner, D.S. The primary hyperoxalurias. Kidney International 2009, 75, 1264–1271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perinpam, M.; Enders, F.T.; Mara, K.C.; Vaughan, L.E.; Mehta, R.A.; Voskoboev, N.; Milliner, D.S.; Lieske, J.C. Plasma oxalate in relation to eGFR in patients with primary hyperoxaluria, enteric hyperoxaluria and urinary stone disease. Clinical Biochemistry 2018, 50, 1014–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, S.R. Nephrocalcinosis in animal models with and without Stones. Urological Research 2010, 38, 429–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehra, Y.; Viswanathan, P. Early Evidence of Global DNA Methylation and Hydroxymethylation Changes in Rat Kidneys Consequent to Hyperoxaluria-Induced Renal Calcium Oxalate Stones. Cytology and Genetics 2022, 56, 458–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandel, N.S.; Henderson Jr, J.D.; Hung, L.Y.; Wille, D.F.; Wiessner, J.H. A porcine model of calcium oxalate kidney stone disease. The Journal of Urology 2004, 171, 1301–1303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evan, A.P.; Lingeman, J.E.; Coe, F.L.; Parks, J.H.; Bledsoe, S.B.; Shao, Y.; Sommer, A.J.; Paterson, R.F.; Kuo, R.L.; Grynpas, M. Randall’s plaque of patients with nephrolithiasis begins in basement membranes of thin loops of Henle. Journal of Clinical Investigation 2003, 111, 607–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canela, V.H. .; Bledsoe, S.B.; Lingeman, J.E.; Gerber, G.; Worcester, E.M.; El-Achkar, T.M.; Williams Jr, J.C. Demineralization and sectioning of human kidney stones: A molecular investigation revealing the spatial heterogneity of the stone matrix. Physiological Reports 2021, 9, e14658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).