Submitted:

31 July 2025

Posted:

01 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Epidemiology of Obesity and Chronic Pain Syndromes

1.1. Obesity and Its Comorbidities

1.2. Obesity and Chronic Pain

2. Mechanisms Underlying Obesity and Osteoarthritis: Role of Oxidative Stress and Meta-Neuroinflammation

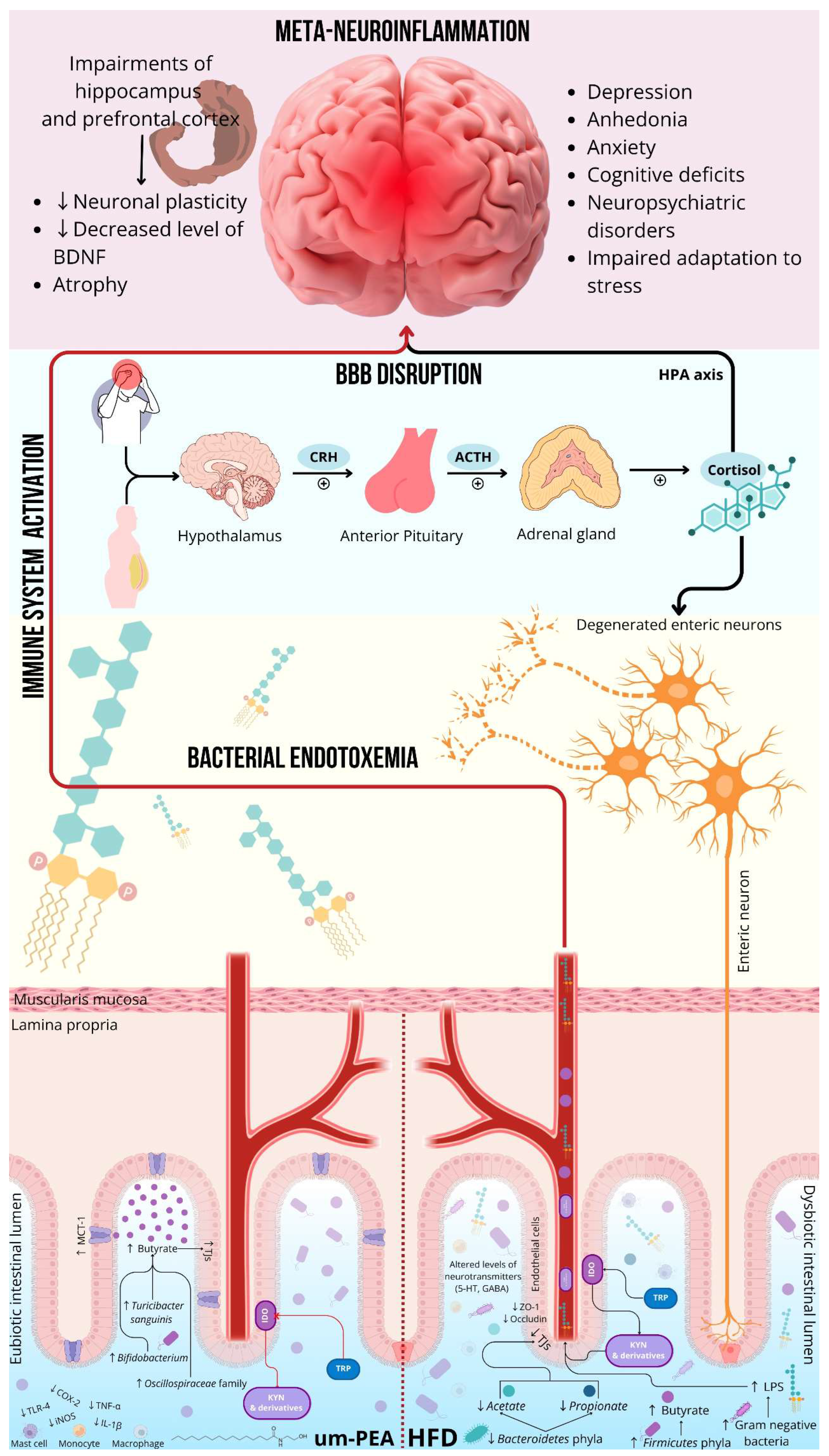

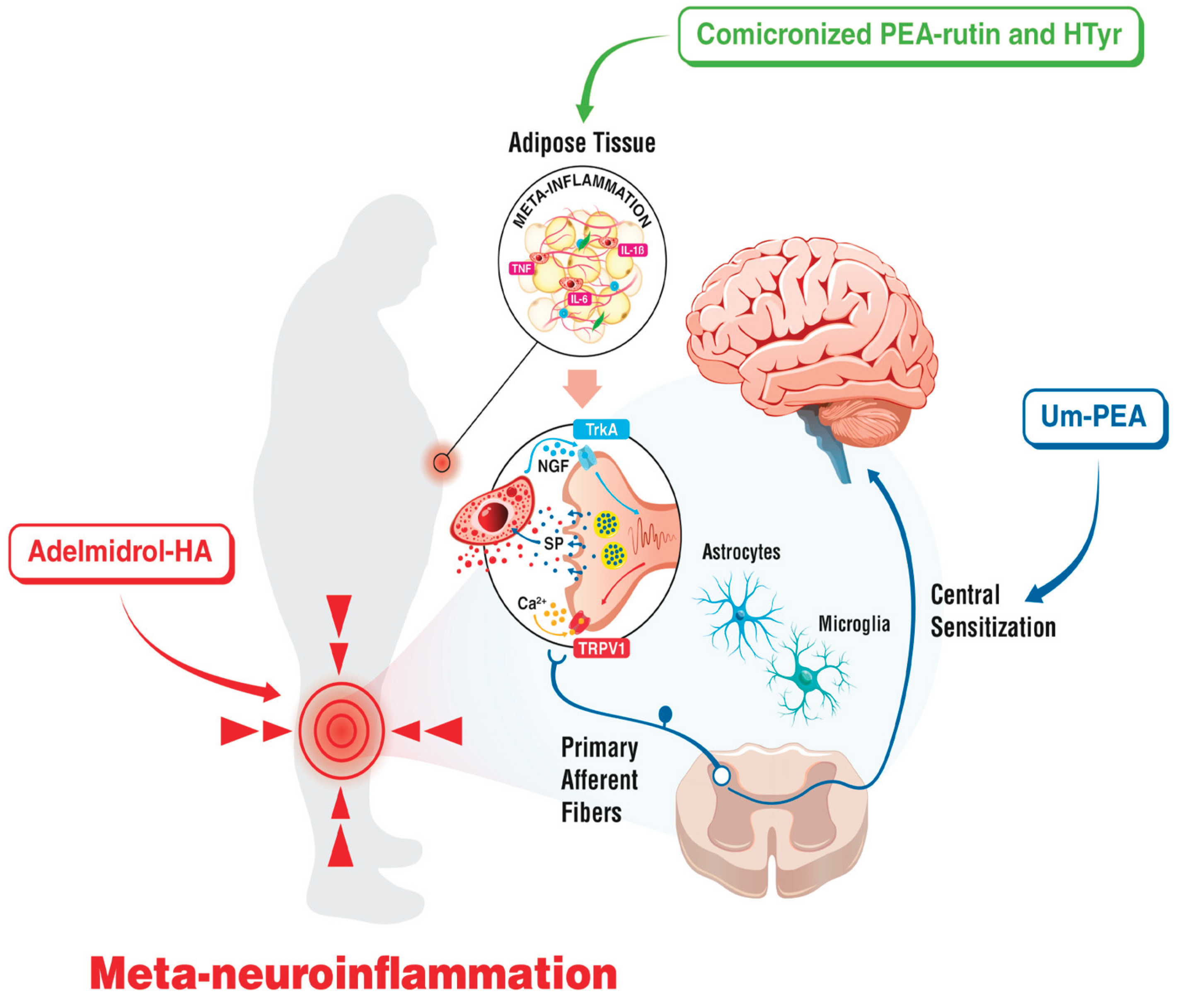

2.1. Obesity and Neuroinflammation

2.2. Obesity, Oxidative Stress and Osteoarthritis

2.3. Osteoarthritis

2.3.1. Osteoarthritis and Neuroinflammation

2.3.2. Osteoarthritis and Oxidative Stress

3. Therapeutic Perspectives

3.1. Palmitoylethanolamide

3.1.1. Palmitoylethanolamide and Osteoarthritis

3.1.2. Palmitoylethanolamide and Neuroinflammation

3.1.3. Palmitoylethanolamide and Low Back Pain

3.1.4. Palmitoylethanolamide and Gut Dysbiosis

3.2. Adelmidrol

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AD | Alzheimer’s disease |

| ADAMTS | Disintegrin and Metalloproteinase with Thrombospondin Motifs |

| ADM | Adelmidrol |

| AGEs | Advanced glycation end-products |

| APP | Amyloid Precursor Protein |

| AT | Adipose tissue |

| Aβ | Amyloidbeta-protein |

| BAT | Beige adipose tissue |

| BBB | Blood–brain barrier |

| BDNF | Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor |

| BM | Basement membrane |

| BMI | Body Mass Index |

| Brd4 | Bromodomain-containing protein 4 |

| CB | Cannabinoid Receptors |

| CFA | Complete Freund’s Adjuvant |

| CKD | Chronic kidney disease |

| CNS | Central nervous system |

| CRH | Corticotropin-Releasing Hormone |

| CVDs | Cardiovascular diseases |

| DALYs | Disability-Adjusted Life-Years |

| DM | Diabetes mellitus |

| DMM | Medial meniscus |

| DRG | Dorsal root ganglia |

| ECM | Extracellular matrix |

| ECMGC | Glycation of the extracellular matrix |

| EnNaCs | Endothelial Na2+ Channels |

| eNOS | Endothelial Nitric Oxide Synthase |

| ENS | Enteric nervous system |

| FAAH | Fatty Acid Amide Hydrolase |

| FFAs | Free fatty acids |

| FLS | Fibroblast-Like Synoviocytes |

| FNDC5 | Fibronectin type III domain containing 5 |

| GM-CSF | Granulocyte-Macrophage Colony-Stimulating Factor |

| GPx | Glutathione Peroxidase |

| GSH | Glutathione |

| HA | Hyaluronic acid |

| HFDs | High-fat diets |

| HIF-1 | Hypoxia-Inducible Factor 1 |

| HO-1 | Heme Oxygenase-1 |

| HTyr | Hydroxytyrosol |

| ICAM-1 | Intercellular Adhesion Molecule-1 |

| IDO | Indoleamine-2,3-Dioxygenase |

| IKK | Inhibitor of Kappa β Kinase |

| IL | Interleukin |

| JAM-A | Junctional Adhesion Molecule-A |

| KLFs | Krüppel-Like Transcription Factors |

| KYN | Kynurenine |

| LBP | low back pain |

| LepR | Leptin receptor |

| lncRNAs | Long non-coding RNAs |

| LPS | Lipopolysaccharide |

| m-PEA | Micronized palmitoylethanolamide |

| M1 | Pro-inflammatory macrophages |

| M2 | Anti-inflammatory macrophages |

| MCP1 | Monocyte Chemoattractant Protein 1 |

| MCs | Mast cells |

| MetS | Metabolic syndrome |

| MHC | Major Histocompatibility Complex |

| MIA | Monosodium iodoacetate |

| MMPs | Matrix metalloproteinases |

| m-PEA– rutin | Comicronized palmitoylethanolamide with rutin |

| mTOR | Mechanistic Target of Rapamycin |

| NAA | N-acetylaspartate |

| NADPH | Nicotinamide Adenine Dinucleotide Phosphate |

| NAE | N-acylethanolamine |

| NF-κβ | Nuclear Factor kappa β |

| NGF | Neurotrophin Nerve Growth Factor |

| NLRP3 | NLR Family Pyrin Domain Containing 3 |

| NO | Nitric oxide |

| NOS2 | Inducible nitric oxide synthase |

| NQO1 | NAD(P)H Oxidoreductase 1 |

| Nrf | Nuclear Respiratory Factor |

| OA | Osteoarthritis |

| PEA | Palmitoylethanolamide |

| PECAM | Platelet Endothelial Cell Adhesion Molecule |

| PGC-1α | Peroxisome Proliferative Activated Receptor-γ Coactivator-1α |

| PK | Prokineticin |

| PKC | Protein Kinase C |

| PKR | Prokineticin receptor |

| PPAR | Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptor |

| PSGL-1 | P-selectin glycoprotein ligand-1 |

| pTau | Hyperphosphorylated Tau |

| QoL | Quality of Life |

| RAGE | Advanced glycation end-products receptor |

| RANK | Receptor Activator of Nuclear Factor-kappa β |

| ROCK | Rho-kinase |

| ROS | Reactive Oxygen Species |

| SCFAs | Short-Chain Fatty Acids |

| SERCA | Sarcoplasmic Reticulum Calcium ATPase |

| Sesn2 | Sestrin2 |

| SF | Synovial fluid |

| SIRT1 | NAD-Dependent Deacetylase Sirtuin 1 |

| SO | Sarcopenic obesity |

| SOD | Superoxide Dismutase |

| TGF-β | Transforming Growth Factor-β |

| TIMPs | Tissue Inhibitor of Metalloproteinases |

| TJs | Tight junctions |

| TLRs | Toll-Like Receptors |

| TNF-α | Tumor Necrosis Factor-α |

| TRK | Tropomyosin-Related Kinase |

| Trp | Tryptophan |

| TWEAK | Tumour Necrosis Factor-Like Weak Inducer of Apoptosis |

| um-PEA | Ultramicronized palmitoylethanolamide |

| VEGF | Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor |

| WAT | White adipose tissue |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

| ZO-1 | Zonula occludens-1 |

| σ1 | Sigma-1 |

References

- Lingvay, I.; Cohen, R.V.; Roux, C.W.L.; Sumithran, P. Obesity in adults. Lancet 2024, 404, 972–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, A.; Sultana, H.; Nazmul Hassan Refat, M.; Farhana, Z.; Abdulbasah Kamil, A.; Meshbahur Rahman, M. The global burden of overweight-obesity and its association with economic status, benefiting from STEPs survey of WHO member states: A meta-analysis. Prev Med Rep 2024, 46, 102882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Lorenzo, A.; Gratteri, S.; Gualtieri, P.; Cammarano, A.; Bertucci, P.; Di Renzo, L. Why primary obesity is a disease? J Transl Med 2019, 17, 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koskinas, K.C.; Van Craenenbroeck, E.M.; Antoniades, C.; Bluher, M.; Gorter, T.M.; Hanssen, H.; Marx, N.; McDonagh, T.A.; Mingrone, G.; Rosengren, A.; et al. Obesity and cardiovascular disease: an ESC clinical consensus statement. Eur Heart J 2024, 45, 4063–4098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elagizi, A.; Kachur, S.; Carbone, S.; Lavie, C.J.; Blair, S.N. A Review of Obesity, Physical Activity, and Cardiovascular Disease. Curr Obes Rep 2020, 9, 571–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russo, S.; Kwiatkowski, M.; Govorukhina, N.; Bischoff, R.; Melgert, B.N. Meta-Inflammation and Metabolic Reprogramming of Macrophages in Diabetes and Obesity: The Importance of Metabolites. Front Immunol 2021, 12, 746151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Favaretto, F.; Bettini, S.; Busetto, L.; Milan, G.; Vettor, R. Adipogenic progenitors in different organs: Pathophysiological implications. Rev Endocr Metab Disord 2022, 23, 71–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdullah, A.; Wolfe, R.; Stoelwinder, J.U.; de Courten, M.; Stevenson, C.; Walls, H.L.; Peeters, A. The number of years lived with obesity and the risk of all-cause and cause-specific mortality. Int J Epidemiol 2011, 40, 985–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kloock, S.; Ziegler, C.G.; Dischinger, U. Obesity and its comorbidities, current treatment options and future perspectives: Challenging bariatric surgery? Pharmacol Ther 2023, 251, 108549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Basilicata, M.; Pieri, M.; Marrone, G.; Nicolai, E.; Di Lauro, M.; Paolino, V.; Tomassetti, F.; Vivarini, I.; Bollero, P.; Bernardini, S.; et al. Saliva as Biomarker for Oral and Chronic Degenerative Non-Communicable Diseases. Metabolites 2023, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhee, C.M.; Ahmadi, S.F.; Kalantar-Zadeh, K. The dual roles of obesity in chronic kidney disease: a review of the current literature. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens 2016, 25, 208–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czaja-Stolc, S.; Potrykus, M.; Stankiewicz, M.; Kaska, L.; Malgorzewicz, S. Pro-Inflammatory Profile of Adipokines in Obesity Contributes to Pathogenesis, Nutritional Disorders, and Cardiovascular Risk in Chronic Kidney Disease. Nutrients 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin-Taboada, M.; Vila-Bedmar, R.; Medina-Gomez, G. From Obesity to Chronic Kidney Disease: How Can Adipose Tissue Affect Renal Function? Nephron 2021, 145, 609–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Wang, Z.; Chen, Y.; Dong, Y. Kidney Damage Caused by Obesity and Its Feasible Treatment Drugs. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taccone-Gallucci, M.; Noce, A.; Bertucci, P.; Fabbri, C.; Manca-di-Villahermosa, S.; Della-Rovere, F.R.; De Francesco, M.; Lonzi, M.; Federici, G.; Scaccia, F.; et al. Chronic treatment with statins increases the availability of selenium in the antioxidant defence systems of hemodialysis patients. J Trace Elem Med Biol 2010, 24, 27–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jastreboff, A.M.; Kotz, C.M.; Kahan, S.; Kelly, A.S.; Heymsfield, S.B. Obesity as a Disease: The Obesity Society 2018 Position Statement. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2019, 27, 7–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Restivo, M.R.; McKinnon, M.C.; Frey, B.N.; Hall, G.B.; Syed, W.; Taylor, V.H. The impact of obesity on neuropsychological functioning in adults with and without major depressive disorder. PLoS One 2017, 12, e0176898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amianto, F.; Martini, M.; Olandese, F.; Davico, C.; Abbate-Daga, G.; Fassino, S.; Vitiello, B. Affectionless control: A parenting style associated with obesity and binge eating disorder in adulthood. Eur Eat Disord Rev 2021, 29, 178–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmer, Z.; Fraser, K.; Grol-Prokopczyk, H.; Zajacova, A. A global study of pain prevalence across 52 countries: examining the role of country-level contextual factors. Pain 2022, 163, 1740–1750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okifuji, A.; Hare, B.D. The association between chronic pain and obesity. J Pain Res 2015, 8, 399–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Min, M.; Du, L.; Gao, Y.; Xie, L.; Gao, J.; Li, L.; Zhong, Z. Trajectories of obesity indices and their association with pain in community-dwelling older adults: Findings from the English longitudinal study of ageing. Arch Gerontol Geriatr 2025, 129, 105690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Disease, G.U.B.o.; Forecasting, C. Burden of disease scenarios by state in the USA, 2022–2050: a forecasting analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. Lancet 2024, 404, 2341–2370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.T.; Liu, Z.; Liu, Y.L.; Zhao, J.J.; Liu, D.W.; Tian, Q.B. Obesity as a Risk Factor for Low Back Pain: A Meta-Analysis. Clin Spine Surg 2018, 31, 22–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heuch, I.; Heuch, I.; Hagen, K.; Zwart, J.A. Overweight and obesity as risk factors for chronic low back pain: a new follow-up in the HUNT Study. BMC Public Health 2024, 24, 2618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vincent, H.K.; Raiser, S.N.; Vincent, K.R. The aging musculoskeletal system and obesity-related considerations with exercise. Ageing Res Rev 2012, 11, 361–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Hao, Q.; Zhou, J.; Wu, J. A comprehensive meta-analysis of risk factors associated with osteosarcopenic obesity: a closer look at gender, lifestyle and comorbidities. Osteoporos Int 2024, 35, 759–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.I.; Ahn, S.H.; Kim, Y.; Lee, J.E.; Choi, E.; Seo, S.K. Effects of sarcopenia and sarcopenic obesity on joint pain and degenerative osteoarthritis in postmenopausal women. Sci Rep 2022, 12, 13543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawal, Y.; Mshelia-Reng, R.; Omonua, S.O.; Odumodu, K.; Shuaibu, R.; Itanyi, U.D.; Abubakar, A.I.; Kolade-Yunusa, H.O.; David, Z.S.; Ogunlana, B.; et al. Predictors of Peripheral Neuropathy Among Persons with Diabetes Mellitus: A Multicenter Cross-Sectional Study. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc 2025, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chai, N.C.; Scher, A.I.; Moghekar, A.; Bond, D.S.; Peterlin, B.L. Obesity and headache: part I--a systematic review of the epidemiology of obesity and headache. Headache 2014, 54, 219–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ursini, F.; Naty, S.; Grembiale, R.D. Fibromyalgia and obesity: the hidden link. Rheumatol Int 2011, 31, 1403–1408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, E.X.; Yazdi, C.; Islam, R.K.; Anwar, A.I.; Alvares-Amado, A.; Townsend, H.; Allen, K.E.; Plakotaris, E.; Hirsch, J.D.; Rieger, R.G.; et al. Diabetic Neuropathy: A Guide to Pain Management. Curr Pain Headache Rep 2024, 28, 1067–1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, R.L.; Chen, N.; Chen, Y.; Wu, X.; Ko, C.Y.; Chen, X.Y. Visceral Adiposity as an Independent Risk Factor for Diabetic Peripheral Neuropathy in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: A Retrospective Study. J Diabetes Res 2024, 2024, 9912907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bigal, M.E.; Liberman, J.N.; Lipton, R.B. Obesity and migraine: a population study. Neurology 2006, 66, 545–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jahromi, S.R.; Martami, F.; Morad Soltani, K.; Togha, M. Migraine and obesity: what is the real direction of their association? Expert Rev Neurother 2023, 23, 75–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D’Onghia, M.; Ciaffi, J.; Lisi, L.; Mancarella, L.; Ricci, S.; Stefanelli, N.; Meliconi, R.; Ursini, F. Fibromyalgia and obesity: A comprehensive systematic review and meta-analysis. Semin Arthritis Rheum 2021, 51, 409–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aparicio, V.A.; Ortega, F.B.; Carbonell-Baeza, A.; Camiletti, D.; Ruiz, J.R.; Delgado-Fernandez, M. Relationship of weight status with mental and physical health in female fibromyalgia patients. Obes Facts 2011, 4, 443–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fruhbeck, G.; Gomez-Ambrosi, J.; Muruzabal, F.J.; Burrell, M.A. The adipocyte: a model for integration of endocrine and metabolic signaling in energy metabolism regulation. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 2001, 280, E827–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.V.; Scherer, P.E. Adiponectin, the past two decades. J Mol Cell Biol 2016, 8, 93–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koenen, M.; Hill, M.A.; Cohen, P.; Sowers, J.R. Obesity, Adipose Tissue and Vascular Dysfunction. Circ Res 2021, 128, 951–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuszkiewicz, J.; Kukulska-Pawluczuk, B.; Piec, K.; Jarek, D.J.; Motolko, K.; Szewczyk-Golec, K.; Wozniak, A. Intersecting Pathways: The Role of Metabolic Dysregulation, Gastrointestinal Microbiome, and Inflammation in Acute Ischemic Stroke Pathogenesis and Outcomes. J Clin Med 2024, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.; Lu, F.; Gao, J.; Yuan, Y. Inflammation-mediated metabolic regulation in adipose tissue. Obes Rev 2024, 25, e13724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liebner, S.; Czupalla, C.J.; Wolburg, H. Current concepts of blood-brain barrier development. Int J Dev Biol 2011, 55, 467–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abbott, N.J.; Patabendige, A.A.; Dolman, D.E.; Yusof, S.R.; Begley, D.J. Structure and function of the blood-brain barrier. Neurobiol Dis 2010, 37, 13–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nehme, Z.; Roehlen, N.; Dhawan, P.; Baumert, T.F. Tight Junction Protein Signaling and Cancer Biology. Cells 2023, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anthony, D.P.; Hegde, M.; Shetty, S.S.; Rafic, T.; Mutalik, S.; Rao, B.S.S. Targeting receptor-ligand chemistry for drug delivery across blood-brain barrier in brain diseases. Life Sci 2021, 274, 119326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thiel, V.E.; Audus, K.L. Nitric oxide and blood-brain barrier integrity. Antioxid Redox Signal 2001, 3, 273–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Engelhardt, B.; Sorokin, L. The blood-brain and the blood-cerebrospinal fluid barriers: function and dysfunction. Semin Immunopathol 2009, 31, 497–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mou, Y.; Du, Y.; Zhou, L.; Yue, J.; Hu, X.; Liu, Y.; Chen, S.; Lin, X.; Zhang, G.; Xiao, H.; et al. Gut Microbiota Interact With the Brain Through Systemic Chronic Inflammation: Implications on Neuroinflammation, Neurodegeneration, and Aging. Front Immunol 2022, 13, 796288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheikh, M.H.; Errede, M.; d’Amati, A.; Khan, N.Q.; Fanti, S.; Loiola, R.A.; McArthur, S.; Purvis, G.S.D.; O’Riordan, C.E.; Ferorelli, D.; et al. Impact of metabolic disorders on the structural, functional, and immunological integrity of the blood-brain barrier: Therapeutic avenues. FASEB J 2022, 36, e22107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boumiza, S.; Chahed, K.; Tabka, Z.; Jacob, M.P.; Norel, X.; Ozen, G. MMPs and TIMPs levels are correlated with anthropometric parameters, blood pressure, and endothelial function in obesity. Sci Rep 2021, 11, 20052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Guan, B.; Chen, S.; Yang, D.; Shen, J. Peroxynitrite activates NLRP3 inflammasome and contributes to hemorrhagic transformation and poor outcome in ischemic stroke with hyperglycemia. Free Radic Biol Med 2021, 165, 171–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Dyken, P.; Lacoste, B. Impact of Metabolic Syndrome on Neuroinflammation and the Blood-Brain Barrier. Front Neurosci 2018, 12, 930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turksen, K.; Aubin, J.E.; Sodek, J.; Kalnins, V.I. Localization of laminin, type IV collagen, fibronectin, and heparan sulfate proteoglycan in chick retinal pigment epithelium basement membrane during embryonic development. J Histochem Cytochem 1985, 33, 665–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Angiari, S.; Constantin, G. Selectins and their ligands as potential immunotherapeutic targets in neurological diseases. Immunotherapy 2013, 5, 1207–1220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takata, F.; Nakagawa, S.; Matsumoto, J.; Dohgu, S. Blood-Brain Barrier Dysfunction Amplifies the Development of Neuroinflammation: Understanding of Cellular Events in Brain Microvascular Endothelial Cells for Prevention and Treatment of BBB Dysfunction. Front Cell Neurosci 2021, 15, 661838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.; Wu, C.; Korpos, E.; Zhang, X.; Agrawal, S.M.; Wang, Y.; Faber, C.; Schafers, M.; Korner, H.; Opdenakker, G.; et al. Focal MMP-2 and MMP-9 activity at the blood-brain barrier promotes chemokine-induced leukocyte migration. Cell Rep 2015, 10, 1040–1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Junker, U.; Jaggi, C.; Bestetti, G.; Rossi, G.L. Basement membrane of hypothalamus and cortex capillaries from normotensive and spontaneously hypertensive rats with streptozotocin-induced diabetes. Acta Neuropathol 1985, 65, 202–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cross, K.; Vetter, S.W.; Alam, Y.; Hasan, M.Z.; Nath, A.D.; Leclerc, E. Role of the Receptor for Advanced Glycation End Products (RAGE) and Its Ligands in Inflammatory Responses. Biomolecules 2024, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diaz-Castro, B.; Robel, S.; Mishra, A. Astrocyte Endfeet in Brain Function and Pathology: Open Questions. Annu Rev Neurosci 2023, 46, 101–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, H.G.; Lee, J.H.; Flausino, L.E.; Quintana, F.J. Neuroinflammation: An astrocyte perspective. Sci Transl Med 2023, 15, eadi7828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanmarco, L.M.; Wheeler, M.A.; Gutierrez-Vazquez, C.; Polonio, C.M.; Linnerbauer, M.; Pinho-Ribeiro, F.A.; Li, Z.; Giovannoni, F.; Batterman, K.V.; Scalisi, G.; et al. Gut-licensed IFNgamma(+) NK cells drive LAMP1(+)TRAIL(+) anti-inflammatory astrocytes. Nature 2021, 590, 473–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proescholdt, M.A.; Heiss, J.D.; Walbridge, S.; Muhlhauser, J.; Capogrossi, M.C.; Oldfield, E.H.; Merrill, M.J. Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) modulates vascular permeability and inflammation in rat brain. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 1999, 58, 613–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Candelario-Jalil, E.; Dijkhuizen, R.M.; Magnus, T. Neuroinflammation, Stroke, Blood-Brain Barrier Dysfunction, and Imaging Modalities. Stroke 2022, 53, 1473–1486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avignon, A.; Sultan, A. PKC-B inhibition: a new therapeutic approach for diabetic complications? Diabetes Metab 2006, 32, 205–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goto, K.; Kondo, H. Diacylglycerol kinase in the central nervous system--molecular heterogeneity and gene expression. Chem Phys Lipids 1999, 98, 109–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yee, Y.H.; Chong, S.J.F.; Kong, L.R.; Goh, B.C.; Pervaiz, S. Sustained IKKbeta phosphorylation and NF-kappaB activation by superoxide-induced peroxynitrite-mediated nitrotyrosine modification of B56gamma3 and PP2A inactivation. Redox Biol 2021, 41, 101834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kadir, R.R.A.; Alwjwaj, M.; McCarthy, Z.; Bayraktutan, U. Therapeutic hypothermia augments the restorative effects of PKC-beta and Nox2 inhibition on an in vitro model of human blood-brain barrier. Metab Brain Dis 2021, 36, 1817–1832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ait-Aissa, K.; Nguyen, Q.M.; Gabani, M.; Kassan, A.; Kumar, S.; Choi, S.K.; Gonzalez, A.A.; Khataei, T.; Sahyoun, A.M.; Chen, C.; et al. MicroRNAs and obesity-induced endothelial dysfunction: key paradigms in molecular therapy. Cardiovasc Diabetol 2020, 19, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Argaw, A.T.; Asp, L.; Zhang, J.; Navrazhina, K.; Pham, T.; Mariani, J.N.; Mahase, S.; Dutta, D.J.; Seto, J.; Kramer, E.G.; et al. Astrocyte-derived VEGF-A drives blood-brain barrier disruption in CNS inflammatory disease. J Clin Invest 2012, 122, 2454–2468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katusic, Z.S.; Austin, S.A. Endothelial nitric oxide: protector of a healthy mind. Eur Heart J 2014, 35, 888–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iova, O.M.; Marin, G.E.; Lazar, I.; Stanescu, I.; Dogaru, G.; Nicula, C.A.; Bulboaca, A.E. Nitric Oxide/Nitric Oxide Synthase System in the Pathogenesis of Neurodegenerative Disorders-An Overview. Antioxidants (Basel) 2023, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Wei, W.; Zhao, M.; Ma, L.; Jiang, X.; Pei, H.; Cao, Y.; Li, H. Interaction between Abeta and Tau in the Pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s Disease. Int J Biol Sci 2021, 17, 2181–2192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henderson, B.W.; Gentry, E.G.; Rush, T.; Troncoso, J.C.; Thambisetty, M.; Montine, T.J.; Herskowitz, J.H. Rho-associated protein kinase 1 (ROCK1) is increased in Alzheimer’s disease and ROCK1 depletion reduces amyloid-beta levels in brain. J Neurochem 2016, 138, 525–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.B.; Ren, R.J.; Zhang, Y.F.; Huang, Y.; Cui, H.L.; Ma, C.; Qiu, W.Y.; Wang, H.; Cui, P.J.; Chen, H.Z.; et al. Rho-associated coiled-coil kinase 1 activation mediates amyloid precursor protein site-specific Ser655 phosphorylation and triggers amyloid pathology. Aging Cell 2019, 18, e13001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, Q.; Leng, X.; Xie, N.; Zhang, Z.; Yang, D.; Hoi, M.P.M. Endothelial Dysfunctions in Blood-Brain Barrier Breakdown in Alzheimer’s Disease: From Mechanisms to Potential Therapies. CNS Neurosci Ther 2024, 30, e70079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dragano, N.R.; Haddad-Tovolli, R.; Velloso, L.A. Leptin, Neuroinflammation and Obesity. Front Horm Res 2017, 48, 84–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obradovic, M.; Sudar-Milovanovic, E.; Soskic, S.; Essack, M.; Arya, S.; Stewart, A.J.; Gojobori, T.; Isenovic, E.R. Leptin and Obesity: Role and Clinical Implication. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2021, 12, 585887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, S.; Byun, M.S.; Yi, D.; Ahn, H.; Jung, G.; Jung, J.H.; Chang, Y.Y.; Kim, K.; Choi, H.; Choi, J.; et al. Plasma Leptin and Alzheimer Protein Pathologies Among Older Adults. JAMA Netw Open 2024, 7, e249539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Littlejohns, T.J.; Kos, K.; Henley, W.E.; Cherubini, A.; Ferrucci, L.; Lang, I.A.; Langa, K.M.; Melzer, D.; Llewellyn, D.J. Serum leptin and risk of cognitive decline in elderly italians. J Alzheimers Dis 2015, 44, 1231–1239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tezapsidis, N.; Johnston, J.M.; Smith, M.A.; Ashford, J.W.; Casadesus, G.; Robakis, N.K.; Wolozin, B.; Perry, G.; Zhu, X.; Greco, S.J.; et al. Leptin: a novel therapeutic strategy for Alzheimer’s disease. J Alzheimers Dis 2009, 16, 731–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daniele, G.; Campi, B.; Saba, A.; Codini, S.; Ciccarone, A.; Giusti, L.; Del Prato, S.; Esterline, R.L.; Ferrannini, E. Plasma N-Acetylaspartate Is Related to Age, Obesity, and Glucose Metabolism: Effects of Antidiabetic Treatment and Bariatric Surgery. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2020, 11, 216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coplan, J.D.; Fathy, H.M.; Abdallah, C.G.; Ragab, S.A.; Kral, J.G.; Mao, X.; Shungu, D.C.; Mathew, S.J. Reduced hippocampal N-acetyl-aspartate (NAA) as a biomarker for overweight. Neuroimage Clin 2014, 4, 326–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Sousa, R.A.L. Exercise-produced irisin effects on brain-related pathological conditions. Metab Brain Dis 2024, 39, 1679–1687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paoletti, I.; Coccurello, R. Irisin: A Multifaceted Hormone Bridging Exercise and Disease Pathophysiology. Int J Mol Sci 2024, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Cui, F.; Ning, K.; Wang, Z.; Fu, P.; Wang, D.; Xu, H. Role of irisin in physiology and pathology. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2022, 13, 962968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Della Guardia, L.; Shin, A.C. Obesity-induced tissue alterations resist weight loss: A mechanistic review. Diabetes Obes Metab 2024, 26, 3045–3057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vints, W.A.J.; Kusleikiene, S.; Sheoran, S.; Valatkeviciene, K.; Gleizniene, R.; Himmelreich, U.; Paasuke, M.; Cesnaitiene, V.J.; Levin, O.; Verbunt, J.; et al. Body fat and components of sarcopenia relate to inflammation, brain volume, and neurometabolism in older adults. Neurobiol Aging 2023, 127, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, C.W.; Yu, K.; Shyh-Chang, N.; Li, G.X.; Jiang, L.J.; Yu, S.L.; Xu, L.Y.; Liu, R.J.; Guo, Z.J.; Xie, H.Y.; et al. Circulating factors associated with sarcopenia during ageing and after intensive lifestyle intervention. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 2019, 10, 586–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Senol, O.; Gundogdu, G.; Gundogdu, K.; Miloglu, F.D. Investigation of the relationships between knee osteoarthritis and obesity via untargeted metabolomics analysis. Clin Rheumatol 2019, 38, 1351–1360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonet, M.L.; Granados, N.; Palou, A. Molecular players at the intersection of obesity and osteoarthritis. Curr Drug Targets 2011, 12, 2103–2128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Courties, A.; Gualillo, O.; Berenbaum, F.; Sellam, J. Metabolic stress-induced joint inflammation and osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2015, 23, 1955–1965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tootsi, K.; Martson, A.; Kals, J.; Paapstel, K.; Zilmer, M. Metabolic factors and oxidative stress in osteoarthritis: a case-control study. Scand J Clin Lab Invest 2017, 77, 520–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Xie, W.; Li, H.; Liu, X.; Lu, Y.; Lu, B.; Deng, Z.; Li, Y. Novel perspectives on leptin in osteoarthritis: Focus on aging. Genes Dis 2024, 11, 101159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hui, W.; Litherland, G.J.; Elias, M.S.; Kitson, G.I.; Cawston, T.E.; Rowan, A.D.; Young, D.A. Leptin produced by joint white adipose tissue induces cartilage degradation via upregulation and activation of matrix metalloproteinases. Ann Rheum Dis 2012, 71, 455–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loef, M.; Schoones, J.W.; Kloppenburg, M.; Ioan-Facsinay, A. Fatty acids and osteoarthritis: different types, different effects. Joint Bone Spine 2019, 86, 451–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obeidat, A.M.; Miller, R.E.; Miller, R.J.; Malfait, A.M. The nociceptive innervation of the normal and osteoarthritic mouse knee. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2019, 27, 1669–1679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Li, M.; Li, X.; Liao, T.; Ma, Z.; Zhang, L.; Xing, R.; Wang, P.; Mao, J. Characteristics of sensory innervation in synovium of rats within different knee osteoarthritis models and the correlation between synovial fibrosis and hyperalgesia. J Adv Res 2022, 35, 141–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, Y.; Cho, D.; Kim, S.K.; Chun, J.S. STING mediates experimental osteoarthritis and mechanical allodynia in mouse. Arthritis Res Ther 2023, 25, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuyinu, E.L.; Narayanan, G.; Nair, L.S.; Laurencin, C.T. Animal models of osteoarthritis: classification, update, and measurement of outcomes. J Orthop Surg Res 2016, 11, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, R.E.; Malfait, A.M. Osteoarthritis pain: What are we learning from animal models? Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol 2017, 31, 676–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, R.E.; Tran, P.B.; Ishihara, S.; Syx, D.; Ren, D.; Miller, R.J.; Valdes, A.M.; Malfait, A.M. Microarray analyses of the dorsal root ganglia support a role for innate neuro-immune pathways in persistent pain in experimental osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2020, 28, 581–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tonello, R.; Silveira Prudente, A.; Hoon Lee, S.; Faith Cohen, C.; Xie, W.; Paranjpe, A.; Roh, J.; Park, C.K.; Chung, G.; Strong, J.A.; et al. Single-cell analysis of dorsal root ganglia reveals metalloproteinase signaling in satellite glial cells and pain. Brain Behav Immun 2023, 113, 401–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nigrovic, P.A.; Lee, D.M. Mast cells in inflammatory arthritis. Arthritis Res Ther 2005, 7, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magarinos, N.J.; Bryant, K.J.; Fosang, A.J.; Adachi, R.; Stevens, R.L.; McNeil, H.P. Mast cell-restricted, tetramer-forming tryptases induce aggrecanolysis in articular cartilage by activating matrix metalloproteinase-3 and -13 zymogens. J Immunol 2013, 191, 1404–1412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lambert, C.; Zappia, J.; Sanchez, C.; Florin, A.; Dubuc, J.E.; Henrotin, Y. The Damage-Associated Molecular Patterns (DAMPs) as Potential Targets to Treat Osteoarthritis: Perspectives From a Review of the Literature. Front Med (Lausanne) 2020, 7, 607186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giannetti, A.; Filice, E.; Caffarelli, C.; Ricci, G.; Pession, A. Mast Cell Activation Disorders. Medicina (Kaunas) 2021, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loucks, A.; Maerz, T.; Hankenson, K.; Moeser, A.; Colbath, A. The multifaceted role of mast cells in joint inflammation and arthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2023, 31, 567–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa-Valente, J.; Calvo, L.; Vacca, V.; Simeoli, R.; Arevalo, J.C.; Malcangio, M. Role of TrkA signalling and mast cells in the initiation of osteoarthritis pain in the monoiodoacetate model. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2018, 26, 84–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barker, P.A.; Mantyh, P.; Arendt-Nielsen, L.; Viktrup, L.; Tive, L. Nerve Growth Factor Signaling and Its Contribution to Pain. J Pain Res 2020, 13, 1223–1241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tran, P.B.; Miller, R.E.; Ishihara, S.; Miller, R.J.; Malfait, A.M. Spinal microglial activation in a murine surgical model of knee osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2017, 25, 718–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohashi, Y.; Uchida, K.; Fukushima, K.; Satoh, M.; Koyama, T.; Tsuchiya, M.; Saito, H.; Takahira, N.; Inoue, G.; Takaso, M. NGF Expression and Elevation in Hip Osteoarthritis Patients with Pain and Central Sensitization. Biomed Res Int 2021, 2021, 9212585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obeidat, A.M.; Donner, A.; Miller, R.E. An update on targets for treating osteoarthritis pain: NGF and TRPV1. Curr Treatm Opt Rheumatol 2020, 6, 129–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- I, O.S.; Kc, R.; Singh, G.; Das, V.; Ma, K.; Li, X.; Mwale, F.; Votta-Velis, G.; Bruce, B.; Natarajan Anbazhagan, A.; et al. Sensory Neuron-Specific Deletion of Tropomyosin Receptor Kinase A (TrkA) in Mice Abolishes Osteoarthritis (OA) Pain via NGF/TrkA Intervention of Peripheral Sensitization. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23. [CrossRef]

- Raoof, R.; Martin Gil, C.; Lafeber, F.; de Visser, H.; Prado, J.; Versteeg, S.; Pascha, M.N.; Heinemans, A.L.P.; Adolfs, Y.; Pasterkamp, J.; et al. Dorsal Root Ganglia Macrophages Maintain Osteoarthritis Pain. J Neurosci 2021, 41, 8249–8261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Z.; Xie, W.; Chen, S.; Strong, J.A.; Print, M.S.; Wang, J.I.; Shareef, A.F.; Ulrich-Lai, Y.M.; Zhang, J.M. High-fat diet increases pain behaviors in rats with or without obesity. Sci Rep 2017, 7, 10350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geraghty, T.; Winter, D.R.; Miller, R.J.; Miller, R.E.; Malfait, A.M. Neuroimmune interactions and osteoarthritis pain: focus on macrophages. Pain Rep 2021, 6, e892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adaes, S.; Almeida, L.; Potes, C.S.; Ferreira, A.R.; Castro-Lopes, J.M.; Ferreira-Gomes, J.; Neto, F.L. Glial activation in the collagenase model of nociception associated with osteoarthritis. Mol Pain 2017, 13, 1744806916688219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogbonna, A.C.; Clark, A.K.; Malcangio, M. Development of monosodium acetate-induced osteoarthritis and inflammatory pain in ageing mice. Age (Dordr) 2015, 37, 9792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin Gil, C.; Raoof, R.; Versteeg, S.; Willemen, H.; Lafeber, F.; Mastbergen, S.C.; Eijkelkamp, N. Myostatin and CXCL11 promote nervous tissue macrophages to maintain osteoarthritis pain. Brain Behav Immun 2024, 116, 203–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bourassa, V.; Deamond, H.; Yousefpour, N.; Fitzcharles, M.A.; Ribeiro-da-Silva, A. Pain-related behavior is associated with increased joint innervation, ipsilateral dorsal horn gliosis, and dorsal root ganglia activating transcription factor 3 expression in a rat ankle joint model of osteoarthritis. Pain Rep 2020, 5, e846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Yang, Y.; Guo, J.; Guo, X.; Feng, Z.; Zhao, X. Spinal NF-kB upregulation contributes to hyperalgesia in a rat model of advanced osteoarthritis. Mol Pain 2020, 16, 1744806920905691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, J.; Wang, X.H.; Song, F.H.; Li, D.Y.; Gao, S.J.; Zhang, L.Q.; Wu, J.Y.; Liu, D.Q.; Wang, L.W.; Zhou, Y.Q.; et al. Inhibition of Brd4 alleviates osteoarthritis pain via suppression of neuroinflammation and activation of Nrf2-mediated antioxidant signalling. Br J Pharmacol 2023, 180, 3194–3214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teleanu, D.M.; Niculescu, A.G.; Lungu, II.; Radu, C.I.; Vladacenco, O.; Roza, E.; Costachescu, B.; Grumezescu, A.M.; Teleanu, R.I. An Overview of Oxidative Stress, Neuroinflammation, and Neurodegenerative Diseases. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, J.; Song, F.H.; Wu, J.Y.; Zhang, L.Q.; Li, D.Y.; Gao, S.J.; Liu, D.Q.; Zhou, Y.Q.; Mei, W. Sestrin2 overexpression attenuates osteoarthritis pain via induction of AMPK/PGC-1alpha-mediated mitochondrial biogenesis and suppression of neuroinflammation. Brain Behav Immun 2022, 102, 53–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.D.; Yue, Y.F.; Chen, T.; Wang, Z.D.; Ding, J.Q.; Xie, M.; Li, D.; Zhu, H.L.; Cheng, M.L. Alleviating effect of lycorine on CFA-induced arthritic pain via inhibition of spinal inflammation and oxidative stress. Exp Ther Med 2023, 25, 241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.Y.; Sun, X.; Zhen, S.Q.; Yu, L.Z.; Ding, J.Q.; Liu, L.; Xie, M.; Zhu, H.L. GSK-3beta inhibition alleviates arthritis pain via reducing spinal mitochondrial reactive oxygen species level and inflammation. PLoS One 2023, 18, e0284332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laitner, M.H.; Erickson, L.C.; Ortman, E. Understanding the Impact of Sex and Gender in Osteoarthritis: Assessing Research Gaps and Unmet Needs. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2021, 30, 634–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tschon, M.; Contartese, D.; Pagani, S.; Borsari, V.; Fini, M. Gender and Sex Are Key Determinants in Osteoarthritis Not Only Confounding Variables. A Systematic Review of Clinical Data. J Clin Med 2021, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mun, C.J.; Letzen, J.E.; Nance, S.; Smith, M.T.; Khanuja, H.S.; Sterling, R.S.; Bicket, M.C.; Haythornthwaite, J.A.; Jamison, R.N.; Edwards, R.R.; et al. Sex Differences in Interleukin-6 Responses Over Time Following Laboratory Pain Testing Among Patients With Knee Osteoarthritis. J Pain 2020, 21, 731–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perruccio, A.V.; Badley, E.M.; Power, J.D.; Canizares, M.; Kapoor, M.; Rockel, J.; Chandran, V.; Gandhi, R.; Mahomed, N.M.; Davey, J.R.; et al. Sex differences in the relationship between individual systemic markers of inflammation and pain in knee osteoarthritis. Osteoarthr Cartil Open 2019, 1, 100004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kosek, E.; Finn, A.; Ultenius, C.; Hugo, A.; Svensson, C.; Ahmed, A.S. Differences in neuroimmune signalling between male and female patients suffering from knee osteoarthritis. J Neuroimmunol 2018, 321, 49–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weerasekera, A.; Morrissey, E.; Kim, M.; Saha, A.; Lin, Y.; Alshelh, Z.; Torrado-Carvajal, A.; Albrecht, D.; Akeju, O.; Kwon, Y.M.; et al. Thalamic neurometabolite alterations in patients with knee osteoarthritis before and after total knee replacement. Pain 2021, 162, 2014–2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amodeo, G.; Franchi, S.; Galimberti, G.; Comi, L.; D’Agnelli, S.; Baciarello, M.; Bignami, E.G.; Sacerdote, P. Osteoarthritis Pain in Old Mice Aggravates Neuroinflammation and Frailty: The Positive Effect of Morphine Treatment. Biomedicines 2022, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muchhala, K.H.; Jacob, J.C.; Dewey, W.L.; Akbarali, H.I. Role of beta-arrestin-2 in short- and long-term opioid tolerance in the dorsal root ganglia. Eur J Pharmacol 2021, 899, 174007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carcole, M.; Kummer, S.; Goncalves, L.; Zamanillo, D.; Merlos, M.; Dickenson, A.H.; Fernandez-Pastor, B.; Cabanero, D.; Maldonado, R. Sigma-1 receptor modulates neuroinflammation associated with mechanical hypersensitivity and opioid tolerance in a mouse model of osteoarthritis pain. Br J Pharmacol 2019, 176, 3939–3955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bufalo, M.C.; Almeida, M.E.S.; Jensen, J.R.; DeOcesano-Pereira, C.; Lichtenstein, F.; Picolo, G.; Chudzinski-Tavassi, A.M.; Sampaio, S.C.; Cury, Y.; Zambelli, V.O. Human Sensory Neuron-like Cells and Glycated Collagen Matrix as a Model for the Screening of Analgesic Compounds. Cells 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galimberti, G.; Amodeo, G.; Magni, G.; Riboldi, B.; Balboni, G.; Onnis, V.; Ceruti, S.; Sacerdote, P.; Franchi, S. Prokineticin System Is a Pharmacological Target to Counteract Pain and Its Comorbid Mood Alterations in an Osteoarthritis Murine Model. Cells 2023, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amodeo, G.; Franchi, S.; D’Agnelli, S.; Galimberti, G.; Baciarello, M.; Bignami, E.G.; Sacerdote, P. Supraspinal neuroinflammation and anxio-depressive-like behaviors in young- and older- adult mice with osteoarthritis pain: the effect of morphine. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2023, 240, 2131–2146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wistrom, E.; Chase, R.; Smith, P.R.; Campbell, Z.T. A compendium of validated pain genes. WIREs Mech Dis 2022, 14, e1570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schumacher, M.A. Peripheral Neuroinflammation and Pain: How Acute Pain Becomes Chronic. Curr Neuropharmacol 2024, 22, 6–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, F.; Jiao, P.; Wang, J.; Li, Y.; Bao, B.; Luoreng, Z.; Wang, X. Role of Long Noncoding RNAs in the Regulation of Cellular Immune Response and Inflammatory Diseases. Cells 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.; Zhao, J.; Dai, T.; Li, X.; Chen, L.; He, Z.; Guo, M.; Zhao, J.; Xu, L. A review of KLF4 and inflammatory disease: Current status and future perspective. Pharmacol Res 2024, 207, 107345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ansari, M.Y.; Ahmad, N.; Haqqi, T.M. Oxidative stress and inflammation in osteoarthritis pathogenesis: Role of polyphenols. Biomed Pharmacother 2020, 129, 110452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolduc, J.A.; Collins, J.A.; Loeser, R.F. Reactive oxygen species, aging and articular cartilage homeostasis. Free Radic Biol Med 2019, 132, 73–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lepetsos, P.; Papavassiliou, A.G. ROS/oxidative stress signaling in osteoarthritis. Biochim Biophys Acta 2016, 1862, 576–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapoor, M.; Martel-Pelletier, J.; Lajeunesse, D.; Pelletier, J.P.; Fahmi, H. Role of proinflammatory cytokines in the pathophysiology of osteoarthritis. Nat Rev Rheumatol 2011, 7, 33–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molnar, V.; Matisic, V.; Kodvanj, I.; Bjelica, R.; Jelec, Z.; Hudetz, D.; Rod, E.; Cukelj, F.; Vrdoljak, T.; Vidovic, D.; et al. Cytokines and Chemokines Involved in Osteoarthritis Pathogenesis. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grigolo, B.; Roseti, L.; Fiorini, M.; Facchini, A. Enhanced lipid peroxidation in synoviocytes from patients with osteoarthritis. J Rheumatol 2003, 30, 345–347. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Franz, A.; Joseph, L.; Mayer, C.; Harmsen, J.F.; Schrumpf, H.; Frobel, J.; Ostapczuk, M.S.; Krauspe, R.; Zilkens, C. The role of oxidative and nitrosative stress in the pathology of osteoarthritis: Novel candidate biomarkers for quantification of degenerative changes in the knee joint. Orthop Rev (Pavia) 2018, 10, 7460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Hou, L.; Guo, Z.; Wang, G.; Xu, J.; Zheng, Z.; Sun, K.; Guo, F. Lipid peroxidation in osteoarthritis: focusing on 4-hydroxynonenal, malondialdehyde, and ferroptosis. Cell Death Discov 2023, 9, 320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.; Ji, P.; Shang, X.; Zhou, Y. Connection between Osteoarthritis and Nitric Oxide: From Pathophysiology to Therapeutic Target. Molecules 2023, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentz, M.; Zaouter, C.; Shi, Q.; Fahmi, H.; Moldovan, F.; Fernandes, J.C.; Benderdour, M. Inhibition of inducible nitric oxide synthase prevents lipid peroxidation in osteoarthritic chondrocytes. J Cell Biochem 2012, 113, 2256–2267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akool el, S.; Kleinert, H.; Hamada, F.M.; Abdelwahab, M.H.; Forstermann, U.; Pfeilschifter, J.; Eberhardt, W. Nitric oxide increases the decay of matrix metalloproteinase 9 mRNA by inhibiting the expression of mRNA-stabilizing factor HuR. Mol Cell Biol 2003, 23, 4901–4916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mastbergen, S.C.; Bijlsma, J.W.; Lafeber, F.P. Synthesis and release of human cartilage matrix proteoglycans are differently regulated by nitric oxide and prostaglandin-E2. Ann Rheum Dis 2008, 67, 52–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katsuyama, K.; Shichiri, M.; Marumo, F.; Hirata, Y. NO inhibits cytokine-induced iNOS expression and NF-kappaB activation by interfering with phosphorylation and degradation of IkappaB-alpha. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 1998, 18, 1796–1802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, W.; Szomor, Z.; Wang, Y.; Murrell, G.A. Nitric oxide enhances collagen synthesis in cultured human tendon cells. J Orthop Res 2006, 24, 159–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubbo, H. Nitric oxide and peroxynitrite in lipid peroxidation. Medicina (B Aires) 1998, 58, 361–366. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Zhao, X.; Lotz, M.; Terkeltaub, R.; Liu-Bryan, R. Mitochondrial biogenesis is impaired in osteoarthritis chondrocytes but reversible via peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator 1alpha. Arthritis Rheumatol 2015, 67, 2141–2153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abu Shelbayeh, O.; Arroum, T.; Morris, S.; Busch, K.B. PGC-1alpha Is a Master Regulator of Mitochondrial Lifecycle and ROS Stress Response. Antioxidants (Basel) 2023, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esteras, N.; Abramov, A.Y. Nrf2 as a regulator of mitochondrial function: Energy metabolism and beyond. Free Radic Biol Med 2022, 189, 136–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Canto, C.; Auwerx, J. PGC-1alpha, SIRT1 and AMPK, an energy sensing network that controls energy expenditure. Curr Opin Lipidol 2009, 20, 98–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngo, V.; Duennwald, M.L. Nrf2 and Oxidative Stress: A General Overview of Mechanisms and Implications in Human Disease. Antioxidants (Basel) 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noce, A.; Ferrannini, M.; Fabrini, R.; Bocedi, A.; Dessi, M.; Galli, F.; Federici, G.; Palumbo, R.; Di Daniele, N.; Ricci, G. Erythrocyte glutathione transferase: a new biomarker for hemodialysis adequacy, overcoming the Kt/V(urea) dogma? Cell Death Dis 2012, 3, e377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheng, W.; Yue, Y.; Qi, T.; Qin, H.; Liu, P.; Wang, D.; Zeng, H.; Yu, F. The Multifaceted Protective Role of Nuclear Factor Erythroid 2-Related Factor 2 in Osteoarthritis: Regulation of Oxidative Stress and Inflammation. J Inflamm Res 2024, 17, 6619–6633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, S.; Buttari, B.; Panieri, E.; Profumo, E.; Saso, L. An Overview of Nrf2 Signaling Pathway and Its Role in Inflammation. Molecules 2020, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; He, C. Nrf2-mediated anti-inflammatory polarization of macrophages as therapeutic targets for osteoarthritis. Front Immunol 2022, 13, 967193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Liang, Y.; Zhou, X.; Tian, Y.; Miao, Z.; Ko, C.C.; Hu, X. Nrf2 differentially regulates osteoclast and osteoblast differentiation for bone homeostasis. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2023, 674, 19–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jie, P.; Wu, Y.; Song, C.; Cheng, Y.; Liu, Y.; Chen, K. Mechanism of Nrf2/miR338-3p/TRAP-1 pathway involved in hyperactivation of synovial fibroblasts in patients with osteoarthritis. Heliyon 2023, 9, e21412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartok, B.; Firestein, G.S. Fibroblast-like synoviocytes: key effector cells in rheumatoid arthritis. Immunol Rev 2010, 233, 233–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Xing, R.; Huang, Z.; Ding, L.; Zhang, L.; Li, M.; Li, X.; Wang, P.; Mao, J. Synovial Fibrosis Involvement in Osteoarthritis. Front Med (Lausanne) 2021, 8, 684389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, A.; Hossain, T.; Eckmann, D.M. Mitochondrial dynamics involves molecular and mechanical events in motility, fusion and fission. Front Cell Dev Biol 2022, 10, 1010232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Klionsky, D.J. Mitochondria removal by autophagy. Autophagy 2011, 7, 297–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowalczyk, P.; Sulejczak, D.; Kleczkowska, P.; Bukowska-Osko, I.; Kucia, M.; Popiel, M.; Wietrak, E.; Kramkowski, K.; Wrzosek, K.; Kaczynska, K. Mitochondrial Oxidative Stress-A Causative Factor and Therapeutic Target in Many Diseases. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, Z.; Zhu, J.; Cai, W.; Lou, C.; Li, Z. The role and intervention of mitochondrial metabolism in osteoarthritis. Mol Cell Biochem 2024, 479, 1513–1524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, C.; Tu, S.; Feng, Y.; Wan, C.; Ai, H.; Chen, Z. Mitochondrial quality control dysfunction in osteoarthritis: Mechanisms, therapeutic strategies & future prospects. Arch Gerontol Geriatr 2024, 125, 105522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, K.; Zhou, H.; Zuo, Q.; Gu, Y.; Cheng, J.; Yan, K.; Zhang, H.; Song, H.; Liang, W.; Zhou, J.; et al. GATD3A-deficiency-induced mitochondrial dysfunction facilitates senescence of fibroblast-like synoviocytes and osteoarthritis progression. Nat Commun 2024, 15, 10923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, Z.; Qi, W.; Zhan, J.; Lin, Z.; Lin, J.; Xue, X.; Pan, X.; Zhou, Y. Activating Nrf2 signalling alleviates osteoarthritis development by inhibiting inflammasome activation. J Cell Mol Med 2020, 24, 13046–13057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.; Zhang, S.; Xiao, Y.; Zhang, W.; Wu, S.; Qin, T.; Yue, Y.; Qian, W.; Li, L. NLRP3 Inflammasome and Inflammatory Diseases. Oxid Med Cell Longev 2020, 2020, 4063562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Zheng, Y.; Li, H. NLRP3 Inflammasome Plays an Important Role in the Pathogenesis of Collagen-Induced Arthritis. Mediators Inflamm 2016, 2016, 9656270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva Santos Ribeiro, P.; Willemen, H.; Versteeg, S.; Martin Gil, C.; Eijkelkamp, N. NLRP3 inflammasome activation in sensory neurons promotes chronic inflammatory and osteoarthritis pain. Immunother Adv 2023, 3, ltad022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, D.H.; Cha, H.J.; Lee, H.; Hong, S.H.; Park, C.; Park, S.H.; Kim, G.Y.; Kim, S.; Kim, H.S.; Hwang, H.J.; et al. Protective Effect of Glutathione against Oxidative Stress-induced Cytotoxicity in RAW 264.7 Macrophages through Activating the Nuclear Factor Erythroid 2-Related Factor-2/Heme Oxygenase-1 Pathway. Antioxidants (Basel) 2019, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, S.; Makosa, D.; Miller, B.; Griffin, T.M. Glutathione as a mediator of cartilage oxidative stress resistance and resilience during aging and osteoarthritis. Connect Tissue Res 2020, 61, 34–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Setti, T.; Arab, M.G.L.; Santos, G.S.; Alkass, N.; Andrade, M.A.P.; Lana, J. The protective role of glutathione in osteoarthritis. J Clin Orthop Trauma 2021, 15, 145–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kimura, Y.; Goto, Y.; Kimura, H. Hydrogen sulfide increases glutathione production and suppresses oxidative stress in mitochondria. Antioxid Redox Signal 2010, 12, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucarini, E.; Micheli, L.; Martelli, A.; Testai, L.; Calderone, V.; Ghelardini, C.; Di Cesare Mannelli, L. Efficacy of isothiocyanate-based compounds on different forms of persistent pain. J Pain Res 2018, 11, 2905–2913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Che, H.; Shao, Z.; Ding, J.; Gao, H.; Liu, X.; Chen, H.; Cai, S.; Ge, J.; Wang, C.; Wu, J.; et al. The effect of allyl isothiocyanate on chondrocyte phenotype is matrix stiffness-dependent: Possible involvement of TRPA1 activation. Front Mol Biosci 2023, 10, 1112653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Xue, R.; Jin, X.; Tan, X. Antiarthritic Activity of Diallyl Disulfide against Freund’s Adjuvant-Induced Arthritic Rat Model. J Environ Pathol Toxicol Oncol 2018, 37, 291–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Yang, P.; Zhou, Z.; Song, T.; Jia, L.; Ye, X.; Yan, W.; Sun, J.; Ye, T.; Zhu, L. GYY4137-induced p65 sulfhydration protects synovial macrophages against pyroptosis by improving mitochondrial function in osteoarthritis development. J Adv Res 2025, 71, 173–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batalle, G.; Cabarga, L.; Pol, O. The Inhibitory Effects of Slow-Releasing Hydrogen Sulfide Donors in the Mechanical Allodynia, Grip Strength Deficits, and Depressive-Like Behaviors Associated with Chronic Osteoarthritis Pain. Antioxidants (Basel) 2019, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keppel Hesselink, J.M.; de Boer, T.; Witkamp, R.F. Palmitoylethanolamide: A Natural Body-Own Anti-Inflammatory Agent, Effective and Safe against Influenza and Common Cold. Int J Inflam 2013, 2013, 151028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bachur, N.R.; Masek, K.; Melmon, K.L.; Udenfriend, S. Fatty Acid Amides of Ethanolamine in Mammalian Tissues. J Biol Chem 1965, 240, 1019–1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siracusa, R.; Fusco, R.; Cordaro, M.; Peritore, A.F.; D’Amico, R.; Gugliandolo, E.; Crupi, R.; Genovese, T.; Evangelista, M.; Di Paola, R.; et al. The Protective Effects of Pre- and Post-Administration of Micronized Palmitoylethanolamide Formulation on Postoperative Pain in Rats. Int J Mol Sci 2020, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petrosino, S.; Cordaro, M.; Verde, R.; Schiano Moriello, A.; Marcolongo, G.; Schievano, C.; Siracusa, R.; Piscitelli, F.; Peritore, A.F.; Crupi, R.; et al. Oral Ultramicronized Palmitoylethanolamide: Plasma and Tissue Levels and Spinal Anti-hyperalgesic Effect. Front Pharmacol 2018, 9, 249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fowler, C.J.; Jonsson, K.O.; Tiger, G. Fatty acid amide hydrolase: biochemistry, pharmacology, and therapeutic possibilities for an enzyme hydrolyzing anandamide, 2-arachidonoylglycerol, palmitoylethanolamide, and oleamide. Biochem Pharmacol 2001, 62, 517–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaczocha, M.; Glaser, S.T.; Chae, J.; Brown, D.A.; Deutsch, D.G. Lipid droplets are novel sites of N-acylethanolamine inactivation by fatty acid amide hydrolase-2. J Biol Chem 2010, 285, 2796–2806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piomelli, D.; Scalvini, L.; Fotio, Y.; Lodola, A.; Spadoni, G.; Tarzia, G.; Mor, M. N-Acylethanolamine Acid Amidase (NAAA): Structure, Function, and Inhibition. J Med Chem 2020, 63, 7475–7490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Congiu, M.; Micheli, L.; Santoni, M.; Sagheddu, C.; Muntoni, A.L.; Makriyannis, A.; Malamas, M.S.; Ghelardini, C.; Di Cesare Mannelli, L.; Pistis, M. N-Acylethanolamine Acid Amidase Inhibition Potentiates Morphine Analgesia and Delays the Development of Tolerance. Neurotherapeutics 2021, 18, 2722–2736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takizawa, M.; Hatta, T.; Iitsuka, H.; Katashima, M.; Sato, Y.; Kuroishi, K.; Nagashima, H. Safety, Tolerability, Pharmacokinetics, and Pharmacodynamics of ASP3652, a Reversible Fatty Acid Amide Hydrolase Inhibitor, in Healthy, Nonelderly, Japanese Men and Elderly, Japanese Men and Women: A Randomized, Double-blind, Placebo-controlled, Single and Multiple Oral Dose, Phase I Study. Clin Ther 2020, 42, 906–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhouayek, M.; Bottemanne, P.; Subramanian, K.V.; Lambert, D.M.; Makriyannis, A.; Cani, P.D.; Muccioli, G.G. N-Acylethanolamine-hydrolyzing acid amidase inhibition increases colon N-palmitoylethanolamine levels and counteracts murine colitis. FASEB J 2015, 29, 650–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonezzi, F.T.; Sasso, O.; Pontis, S.; Realini, N.; Romeo, E.; Ponzano, S.; Nuzzi, A.; Fiasella, A.; Bertozzi, F.; Piomelli, D. An Important Role for N-Acylethanolamine Acid Amidase in the Complete Freund’s Adjuvant Rat Model of Arthritis. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 2016, 356, 656–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhouayek, M.; Bottemanne, P.; Makriyannis, A.; Muccioli, G.G. N-acylethanolamine-hydrolyzing acid amidase and fatty acid amide hydrolase inhibition differentially affect N-acylethanolamine levels and macrophage activation. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Cell Biol Lipids 2017, 1862, 474–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larauche, M.; Mulak, A.; Ha, C.; Million, M.; Arnett, S.; Germano, P.; Pearson, J.P.; Currie, M.G.; Tache, Y. FAAH inhibitor URB597 shows anti-hyperalgesic action and increases brain and intestinal tissues fatty acid amides in a model of CRF(1) agonist mediated visceral hypersensitivity in male rats. Neurogastroenterol Motil 2024, 36, e14927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, P.; Xiang, L.; Yang, Y.; Wu, Y.; Hu, T.; Liu, X.; Lin, F.; Xiu, Y.; Wu, K.; Lu, C.; et al. N-Acylethanolamine acid amidase (NAAA) inhibitor F215 as a novel therapeutic agent for osteoarthritis. Pharmacol Res 2019, 145, 104264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sagheddu, C.; Scherma, M.; Congiu, M.; Fadda, P.; Carta, G.; Banni, S.; Wood, J.T.; Makriyannis, A.; Malamas, M.S.; Pistis, M. Inhibition of N-acylethanolamine acid amidase reduces nicotine-induced dopamine activation and reward. Neuropharmacology 2019, 144, 327–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bottemanne, P.; Guillemot-Legris, O.; Paquot, A.; Masquelier, J.; Malamas, M.; Makriyannis, A.; Alhouayek, M.; Muccioli, G.G. N-Acylethanolamine-Hydrolyzing Acid Amidase Inhibition, but Not Fatty Acid Amide Hydrolase Inhibition, Prevents the Development of Experimental Autoimmune Encephalomyelitis in Mice. Neurotherapeutics 2021, 18, 1815–1833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greco, R.; Demartini, C.; Zanaboni, A.; Casini, I.; De Icco, R.; Reggiani, A.; Misto, A.; Piomelli, D.; Tassorelli, C. Characterization of the peripheral FAAH inhibitor, URB937, in animal models of acute and chronic migraine. Neurobiol Dis 2021, 147, 105157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vacondio, F.; Bassi, M.; Silva, C.; Castelli, R.; Carmi, C.; Scalvini, L.; Lodola, A.; Vivo, V.; Flammini, L.; Barocelli, E.; et al. Amino Acid Derivatives as Palmitoylethanolamide Prodrugs: Synthesis, In Vitro Metabolism and In Vivo Plasma Profile in Rats. PLoS One 2015, 10, e0128699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manzo, E.; Schiano Moriello, A.; Tinto, F.; Verde, R.; Allara, M.; De Petrocellis, L.; Pagano, E.; Izzo, A.A.; Di Marzo, V.; Petrosino, S. A Glucuronic Acid-Palmitoylethanolamide Conjugate (GLUPEA) Is an Innovative Drug Delivery System and a Potential Bioregulator. Cells 2021, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gugliandolo, E.; Peritore, A.F.; Piras, C.; Cuzzocrea, S.; Crupi, R. Palmitoylethanolamide and Related ALIAmides: Prohomeostatic Lipid Compounds for Animal Health and Wellbeing. Vet Sci 2020, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roa-Coria, J.E.; Navarrete-Vazquez, G.; Fowler, C.J.; Flores-Murrieta, F.J.; Deciga-Campos, M.; Granados-Soto, V. N-(4-Methoxy-2-nitrophenyl)hexadecanamide, a palmitoylethanolamide analogue, reduces formalin-induced nociception. Life Sci 2012, 91, 1288–1294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Impellizzeri, D.; Di Paola, R.; Cordaro, M.; Gugliandolo, E.; Casili, G.; Morittu, V.M.; Britti, D.; Esposito, E.; Cuzzocrea, S. Adelmidrol, a palmitoylethanolamide analogue, as a new pharmacological treatment for the management of acute and chronic inflammation. Biochem Pharmacol 2016, 119, 27–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallace, V.C.; Segerdahl, A.R.; Lambert, D.M.; Vandevoorde, S.; Blackbeard, J.; Pheby, T.; Hasnie, F.; Rice, A.S. The effect of the palmitoylethanolamide analogue, palmitoylallylamide (L-29) on pain behaviour in rodent models of neuropathy. Br J Pharmacol 2007, 151, 1117–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clayton, P.; Hill, M.; Bogoda, N.; Subah, S.; Venkatesh, R. Palmitoylethanolamide: A Natural Compound for Health Management. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gabrielsson, L.; Mattsson, S.; Fowler, C.J. Palmitoylethanolamide for the treatment of pain: pharmacokinetics, safety and efficacy. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2016, 82, 932–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhukov, O.D. [Distribution of N-([1-14C]-palmitoyl)ethanolamine in rat tissues]. Ukr Biokhim Zh (1999) 1999, 71, 124–125. [Google Scholar]

- Artamonov, M.; Zhukov, O.; Shuba, I.; Storozhuk, L.; Khmel, T.; Klimashevsky, V.; Mikosha, A.; Gula, N. Incorporation of labelled N-acylethanolamine (NAE) into rat brain regions in vivo and adaptive properties of saturated NAE under x-ray irradiation. Ukr Biokhim Zh (1999) 2005, 77, 51–62. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- di Marzo, V.; Skaper, S.D. Palmitoylethanolamide: biochemistry, pharmacology and therapeutic use of a pleiotropic anti-inflammatory lipid mediator. CNS Neurol Disord Drug Targets 2013, 12, 4–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takada, I.; Makishima, M. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor agonists and antagonists: a patent review (2014-present). Expert Opin Ther Pat 2020, 30, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katsiki, N.; Nikolic, D.; Montalto, G.; Banach, M.; Mikhailidis, D.P.; Rizzo, M. The role of fibrate treatment in dyslipidemia: an overview. Curr Pharm Des 2013, 19, 3124–3131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keller, H.; Mahfoudi, A.; Dreyer, C.; Hihi, A.K.; Medin, J.; Ozato, K.; Wahli, W. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors and lipid metabolism. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1993, 684, 157–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Youssef, J.; Badr, M. Role of Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptors in Inflammation Control. J Biomed Biotechnol 2004, 2004, 156–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Annunziata, C.; Pirozzi, C.; Lama, A.; Senzacqua, M.; Comella, F.; Bordin, A.; Monnolo, A.; Pelagalli, A.; Ferrante, M.C.; Mollica, M.P.; et al. Palmitoylethanolamide Promotes White-to-Beige Conversion and Metabolic Reprogramming of Adipocytes: Contribution of PPAR-alpha. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melini, S.; Pirozzi, C.; Lama, A.; Comella, F.; Opallo, N.; Del Piano, F.; Di Napoli, E.; Mollica, M.P.; Paciello, O.; Ferrante, M.C.; et al. Co-Micronized Palmitoylethanolamide and Rutin Associated With Hydroxytyrosol Recover Diabesity-Induced Hepatic Dysfunction in Mice: In Vitro Insights Into the Synergistic Effect. Phytother Res 2024, 38, 6035–6047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornali, K.; Di Lauro, M.; Marrone, G.; Masci, C.; Montalto, G.; Giovannelli, A.; Schievano, C.; Tesauro, M.; Pieri, M.; Bernardini, S.; et al. The Effects of a Food Supplement, Based on Co-Micronized Palmitoylethanolamide (PEA)-Rutin and Hydroxytyrosol, in Metabolic Syndrome Patients: Preliminary Results. Nutrients 2025, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skaper, S.D.; Facci, L. Mast cell-glia axis in neuroinflammation and therapeutic potential of the anandamide congener palmitoylethanolamide. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 2012, 367, 3312–3325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrosino, S.; Schiano Moriello, A.; Verde, R.; Allara, M.; Imperatore, R.; Ligresti, A.; Mahmoud, A.M.; Peritore, A.F.; Iannotti, F.A.; Di Marzo, V. Palmitoylethanolamide counteracts substance P-induced mast cell activation in vitro by stimulating diacylglycerol lipase activity. J Neuroinflammation 2019, 16, 274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Filippis, D.; Luongo, L.; Cipriano, M.; Palazzo, E.; Cinelli, M.P.; de Novellis, V.; Maione, S.; Iuvone, T. Palmitoylethanolamide reduces granuloma-induced hyperalgesia by modulation of mast cell activation in rats. Mol Pain 2011, 7, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muccioli, G.G.; Stella, N. Microglia produce and hydrolyze palmitoylethanolamide. Neuropharmacology 2008, 54, 16–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo Verme, J.; Fu, J.; Astarita, G.; La Rana, G.; Russo, R.; Calignano, A.; Piomelli, D. The nuclear receptor peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-alpha mediates the anti-inflammatory actions of palmitoylethanolamide. Mol Pharmacol 2005, 67, 15–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aghaei, I.; Rostampour, M.; Shabani, M.; Naderi, N.; Motamedi, F.; Babaei, P.; Khakpour-Taleghani, B. Palmitoylethanolamide attenuates PTZ-induced seizures through CB1 and CB2 receptors. Epilepsy Res 2015, 117, 23–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Im, D.S. GPR119 and GPR55 as Receptors for Fatty Acid Ethanolamides, Oleoylethanolamide and Palmitoylethanolamide. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guida, F.; Luongo, L.; Boccella, S.; Giordano, M.E.; Romano, R.; Bellini, G.; Manzo, I.; Furiano, A.; Rizzo, A.; Imperatore, R.; et al. Palmitoylethanolamide induces microglia changes associated with increased migration and phagocytic activity: involvement of the CB2 receptor. Sci Rep 2017, 7, 375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambrosino, P.; Soldovieri, M.V.; Russo, C.; Taglialatela, M. Activation and desensitization of TRPV1 channels in sensory neurons by the PPARalpha agonist palmitoylethanolamide. Br J Pharmacol 2013, 168, 1430–1444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coluzzi, F.; Scerpa, M.S.; Alessandri, E.; Romualdi, P.; Rocco, M. Role of TRP Channels in Cancer-Induced Bone Pain. Int J Mol Sci 2025, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrosino, S.; Schiano Moriello, A.; Cerrato, S.; Fusco, M.; Puigdemont, A.; De Petrocellis, L.; Di Marzo, V. The anti-inflammatory mediator palmitoylethanolamide enhances the levels of 2-arachidonoyl-glycerol and potentiates its actions at TRPV1 cation channels. Br J Pharmacol 2016, 173, 1154–1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capasso, R.; Orlando, P.; Pagano, E.; Aveta, T.; Buono, L.; Borrelli, F.; Di Marzo, V.; Izzo, A.A. Palmitoylethanolamide normalizes intestinal motility in a model of post-inflammatory accelerated transit: involvement of CB(1) receptors and TRPV1 channels. Br J Pharmacol 2014, 171, 4026–4037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karwad, M.A.; Macpherson, T.; Wang, B.; Theophilidou, E.; Sarmad, S.; Barrett, D.A.; Larvin, M.; Wright, K.L.; Lund, J.N.; O’Sullivan, S.E. Oleoylethanolamine and palmitoylethanolamine modulate intestinal permeability in vitro via TRPV1 and PPARalpha. FASEB J 2017, 31, 469–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Icco, R.; Greco, R.; Demartini, C.; Vergobbi, P.; Zanaboni, A.; Tumelero, E.; Reggiani, A.; Realini, N.; Sances, G.; Grillo, V.; et al. Spinal nociceptive sensitization and plasma palmitoylethanolamide levels during experimentally induced migraine attacks. Pain 2021, 162, 2376–2385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skaper, S.D.; Facci, L.; Giusti, P. Glia and mast cells as targets for palmitoylethanolamide, an anti-inflammatory and neuroprotective lipid mediator. Mol Neurobiol 2013, 48, 340–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scuderi, C.; Esposito, G.; Blasio, A.; Valenza, M.; Arietti, P.; Steardo, L., Jr.; Carnuccio, R.; De Filippis, D.; Petrosino, S.; Iuvone, T.; et al. Palmitoylethanolamide counteracts reactive astrogliosis induced by beta-amyloid peptide. J Cell Mol Med 2011, 15, 2664–2674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beggiato, S.; Borelli, A.C.; Ferraro, L.; Tanganelli, S.; Antonelli, T.; Tomasini, M.C. Palmitoylethanolamide Blunts Amyloid-beta42-Induced Astrocyte Activation and Improves Neuronal Survival in Primary Mouse Cortical Astrocyte-Neuron Co-Cultures. J Alzheimers Dis 2018, 61, 389–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Agostino, G.; Russo, R.; Avagliano, C.; Cristiano, C.; Meli, R.; Calignano, A. Palmitoylethanolamide protects against the amyloid-beta25-35-induced learning and memory impairment in mice, an experimental model of Alzheimer disease. Neuropsychopharmacology 2012, 37, 1784–1792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiani, A.K.; Miggiano, G.A.D.; Aquilanti, B.; Velluti, V.; Matera, G.; Gagliardi, L.; Bertelli, M. Food supplements based on palmitoylethanolamide plus hydroxytyrosol from olive tree or Bacopa monnieri extracts for neurological diseases. Acta Biomed 2020, 91, e2020007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Facchinetti, R.; Valenza, M.; Bronzuoli, M.R.; Menegoni, G.; Ratano, P.; Steardo, L.; Campolongo, P.; Scuderi, C. Looking for a Treatment for the Early Stage of Alzheimer’s Disease: Preclinical Evidence with Co-Ultramicronized Palmitoylethanolamide and Luteolin. Int J Mol Sci 2020, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brotini, S.; Schievano, C.; Guidi, L. Ultra-micronized Palmitoylethanolamide: An Efficacious Adjuvant Therapy for Parkinson’s Disease. CNS Neurol Disord Drug Targets 2017, 16, 705–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jung, J.I.; Lee, H.S.; Jeon, Y.E.; Kim, S.M.; Hong, S.H.; Moon, J.M.; Lim, C.Y.; Kim, Y.H.; Kim, E.J. Anti-inflammatory activity of palmitoylethanolamide ameliorates osteoarthritis induced by monosodium iodoacetate in Sprague-Dawley rats. Inflammopharmacology 2021, 29, 1475–1486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seol, T.K.; Lee, W.; Park, S.; Kim, K.N.; Kim, T.Y.; Oh, Y.N.; Jun, J.H. Effect of palmitoylethanolamide on inflammatory and neuropathic pain in rats. Korean J Anesthesiol 2017, 70, 561–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Della Rocca, G.; Re, G. Palmitoylethanolamide and Related ALIAmides for Small Animal Health: State of the Art. Biomolecules 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruccu, G.; Stefano, G.D.; Marchettini, P.; Truini, A. Micronized Palmitoylethanolamide: A Post Hoc Analysis of a Controlled Study in Patients with Low Back Pain - Sciatica. CNS Neurol Disord Drug Targets 2019, 18, 491–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scaturro, D.; Asaro, C.; Lauricella, L.; Tomasello, S.; Varrassi, G.; Letizia Mauro, G. Combination of Rehabilitative Therapy with Ultramicronized Palmitoylethanolamide for Chronic Low Back Pain: An Observational Study. Pain Ther 2020, 9, 319–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Passavanti, M.B.; Fiore, M.; Sansone, P.; Aurilio, C.; Pota, V.; Barbarisi, M.; Fierro, D.; Pace, M.C. The beneficial use of ultramicronized palmitoylethanolamide as add-on therapy to Tapentadol in the treatment of low back pain: a pilot study comparing prospective and retrospective observational arms. BMC Anesthesiol 2017, 17, 171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chirchiglia, D.; Paventi, S.; Seminara, P.; Cione, E.; Gallelli, L. N-Palmitoyl Ethanol Amide Pharmacological Treatment in Patients With Nonsurgical Lumbar Radiculopathy. J Clin Pharmacol 2018, 58, 733–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Germini, F.; Coerezza, A.; Andreinetti, L.; Nobili, A.; Rossi, P.D.; Mari, D.; Guyatt, G.; Marcucci, M. N-of-1 Randomized Trials of Ultra-Micronized Palmitoylethanolamide in Older Patients with Chronic Pain. Drugs Aging 2017, 34, 941–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paladini, A.; Varrassi, G.; Bentivegna, G.; Carletti, S.; Piroli, A.; Coaccioli, S. Palmitoylethanolamide in the Treatment of Failed Back Surgery Syndrome. Pain Res Treat 2017, 2017, 1486010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, B.; Comelli, F.; Bettoni, I.; Colleoni, M.; Giagnoni, G. The endogenous fatty acid amide, palmitoylethanolamide, has anti-allodynic and anti-hyperalgesic effects in a murine model of neuropathic pain: involvement of CB(1), TRPV1 and PPARgamma receptors and neurotrophic factors. Pain 2008, 139, 541–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adak, A.; Khan, M.R. An insight into gut microbiota and its functionalities. Cell Mol Life Sci 2019, 76, 473–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asadi, A.; Shadab Mehr, N.; Mohamadi, M.H.; Shokri, F.; Heidary, M.; Sadeghifard, N.; Khoshnood, S. Obesity and gut-microbiota-brain axis: A narrative review. J Clin Lab Anal 2022, 36, e24420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farzi, A.; Frohlich, E.E.; Holzer, P. Gut Microbiota and the Neuroendocrine System. Neurotherapeutics 2018, 15, 5–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chidambaram, S.B.; Essa, M.M.; Rathipriya, A.G.; Bishir, M.; Ray, B.; Mahalakshmi, A.M.; Tousif, A.H.; Sakharkar, M.K.; Kashyap, R.S.; Friedland, R.P.; et al. Gut dysbiosis, defective autophagy and altered immune responses in neurodegenerative diseases: Tales of a vicious cycle. Pharmacol Ther 2022, 231, 107988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malesza, I.J.; Malesza, M.; Walkowiak, J.; Mussin, N.; Walkowiak, D.; Aringazina, R.; Bartkowiak-Wieczorek, J.; Madry, E. High-Fat, Western-Style Diet, Systemic Inflammation, and Gut Microbiota: A Narrative Review. Cells 2021, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weiss, G.A.; Hennet, T. Mechanisms and consequences of intestinal dysbiosis. Cell Mol Life Sci 2017, 74, 2959–2977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levy, M.; Kolodziejczyk, A.A.; Thaiss, C.A.; Elinav, E. Dysbiosis and the immune system. Nat Rev Immunol 2017, 17, 219–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Lauro, M.; Guerriero, C.; Cornali, K.; Albanese, M.; Costacurta, M.; Mercuri, N.B.; Di Daniele, N.; Noce, A. Linking Migraine to Gut Dysbiosis and Chronic Non-Communicable Diseases. Nutrients 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Renzo, L.; Gualtieri, P.; Romano, L.; Marrone, G.; Noce, A.; Pujia, A.; Perrone, M.A.; Aiello, V.; Colica, C.; De Lorenzo, A. Role of Personalized Nutrition in Chronic-Degenerative Diseases. Nutrients 2019, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noce, A.; Marrone, G.; Di Daniele, F.; Ottaviani, E.; Wilson Jones, G.; Bernini, R.; Romani, A.; Rovella, V. Impact of Gut Microbiota Composition on Onset and Progression of Chronic Non-Communicable Diseases. Nutrients 2019, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noce, A.; Marchetti, M.; Marrone, G.; Di Renzo, L.; Di Lauro, M.; Di Daniele, F.; Albanese, M.; Di Daniele, N.; De Lorenzo, A. Link between gut microbiota dysbiosis and chronic kidney disease. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci 2022, 26, 2057–2074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canale, M.P.; Noce, A.; Di Lauro, M.; Marrone, G.; Cantelmo, M.; Cardillo, C.; Federici, M.; Di Daniele, N.; Tesauro, M. Gut Dysbiosis and Western Diet in the Pathogenesis of Essential Arterial Hypertension: A Narrative Review. Nutrients 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coluzzi, F.; Scerpa, M.S.; Loffredo, C.; Borro, M.; Pergolizzi, J.V.; LeQuang, J.A.; Alessandri, E.; Simmaco, M.; Rocco, M. Opioid Use and Gut Dysbiosis in Cancer Pain Patients. Int J Mol Sci 2024, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvaro, D.; Caraceni, A.T.; Coluzzi, F.; Gianni, W.; Lugoboni, F.; Marinangeli, F.; Massazza, G.; Pinto, C.; Varrassi, G. What to Do and What Not to Do in the Management of Opioid-Induced Constipation: A Choosing Wisely Report. Pain Ther 2020, 9, 657–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herman, J.P.; McKlveen, J.M.; Ghosal, S.; Kopp, B.; Wulsin, A.; Makinson, R.; Scheimann, J.; Myers, B. Regulation of the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenocortical Stress Response. Compr Physiol 2016, 6, 603–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dicks, L.M.T. Gut Bacteria and Neurotransmitters. Microorganisms 2022, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rusch, J.A.; Layden, B.T.; Dugas, L.R. Signalling cognition: the gut microbiota and hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2023, 14, 1130689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, S.; Yang, L.; Cheng, F.; Zhang, Z.; Li, J.; Liu, W.; Li, Y.; Chen, Y.; Bao, Y.; Chen, L.; et al. Gut Microbiota Are Associated With Psychological Stress-Induced Defections in Intestinal and Blood-Brain Barriers. Front Microbiol 2019, 10, 3067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertollo, A.G.; Santos, C.F.; Bagatini, M.D.; Ignacio, Z.M. Hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal and gut-brain axes in biological interaction pathway of the depression. Front Neurosci 2025, 19, 1541075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suda, T. Adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH). Jpn J Med 1989, 28, 789–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McEwen, B.S.; Nasca, C.; Gray, J.D. Stress Effects on Neuronal Structure: Hippocampus, Amygdala, and Prefrontal Cortex. Neuropsychopharmacology 2016, 41, 3–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- P. , S.; Vellapandian, C. Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal (HPA) Axis: Unveiling the Potential Mechanisms Involved in Stress-Induced Alzheimer’s Disease and Depression. Cureus 2024, 16, e67595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anand, N.; Gorantla, V.R.; Chidambaram, S.B. The Role of Gut Dysbiosis in the Pathophysiology of Neuropsychiatric Disorders. Cells 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Numakawa, T.; Kajihara, R. Involvement of brain-derived neurotrophic factor signaling in the pathogenesis of stress-related brain diseases. Front Mol Neurosci 2023, 16, 1247422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamamah, S.; Aghazarian, A.; Nazaryan, A.; Hajnal, A.; Covasa, M. Role of Microbiota-Gut-Brain Axis in Regulating Dopaminergic Signaling. Biomedicines 2022, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Jian, Y.P.; Zhang, Y.N.; Li, Y.; Gu, L.T.; Sun, H.H.; Liu, M.D.; Zhou, H.L.; Wang, Y.S.; Xu, Z.X. Short-chain fatty acids in diseases. Cell Commun Signal 2023, 21, 212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braniste, V.; Al-Asmakh, M.; Kowal, C.; Anuar, F.; Abbaspour, A.; Toth, M.; Korecka, A.; Bakocevic, N.; Ng, L.G.; Kundu, P.; et al. The gut microbiota influences blood-brain barrier permeability in mice. Sci Transl Med 2014, 6, 263ra158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chakraborty, P.; Gamage, H.; Laird, A.S. Butyrate as a potential therapeutic agent for neurodegenerative disorders. Neurochem Int 2024, 176, 105745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maldonado, R.F.; Sa-Correia, I.; Valvano, M.A. Lipopolysaccharide modification in Gram-negative bacteria during chronic infection. FEMS Microbiol Rev 2016, 40, 480–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basnet, T.B.; Gc, S.; Basnet, R.; Fatima, S.; Safdar, M.; Sehar, B.; Alsubaie, A.S.R.; Zeb, F. Interaction between gut microbiota metabolites and dietary components in lipid metabolism and metabolic diseases. Access Microbiol 2023, 5, acmi000403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohr, A.E.; Crawford, M.; Jasbi, P.; Fessler, S.; Sweazea, K.L. Lipopolysaccharide and the gut microbiota: considering structural variation. FEBS Lett 2022, 596, 849–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammad, S.; Thiemermann, C. Role of Metabolic Endotoxemia in Systemic Inflammation and Potential Interventions. Front Immunol 2020, 11, 594150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, S.; Zhao, Q.; Guan, Y.; Sun, Z.; Li, W.; Guo, S.; Zhang, A. The communication mechanism of the gut-brain axis and its effect on central nervous system diseases: A systematic review. Biomed Pharmacother 2024, 178, 117207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russo, R.; Cristiano, C.; Avagliano, C.; De Caro, C.; La Rana, G.; Raso, G.M.; Canani, R.B.; Meli, R.; Calignano, A. Gut-brain Axis: Role of Lipids in the Regulation of Inflammation, Pain and CNS Diseases. Curr Med Chem 2018, 25, 3930–3952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Couch, D.G.; Cook, H.; Ortori, C.; Barrett, D.; Lund, J.N.; O’Sullivan, S.E. Palmitoylethanolamide and Cannabidiol Prevent Inflammation-induced Hyperpermeability of the Human Gut In Vitro and In Vivo-A Randomized, Placebo-controlled, Double-blind Controlled Trial. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2019, 25, 1006–1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pirozzi, C.; Coretti, L.; Opallo, N.; Bove, M.; Annunziata, C.; Comella, F.; Turco, L.; Lama, A.; Trabace, L.; Meli, R.; et al. Palmitoylethanolamide counteracts high-fat diet-induced gut dysfunction by reprogramming microbiota composition and affecting tryptophan metabolism. Front Nutr 2023, 10, 1143004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correia, A.S.; Vale, N. Tryptophan Metabolism in Depression: A Narrative Review with a Focus on Serotonin and Kynurenine Pathways. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Batacan, R., Jr.; Briskey, D.; Bajagai, Y.S.; Smith, C.; Stanley, D.; Rao, A. Effect of Palmitoylethanolamide Compared to a Placebo on the Gut Microbiome and Biochemistry in an Overweight Adult Population: A Randomised, Placebo Controlled, Double-Blind Study. Biomedicines 2024, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Filippis, D.; D’Amico, A.; Cinelli, M.P.; Esposito, G.; Di Marzo, V.; Iuvone, T. Adelmidrol, a palmitoylethanolamide analogue, reduces chronic inflammation in a carrageenin-granuloma model in rats. J Cell Mol Med 2009, 13, 1086–1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]