1. Introduction

Capillary barrier cover (CBC) layer is a geotechnical structure which the coarse-grained soil layer covered by fine-grained soil layer. Under unsaturated conditions, the difference hydraulic properties at the fine-coarse grained layer interface hinders downward water infiltration. Infiltration water is intercepted, stored, or lateral drainage within the fine-grained layer, if the evaporation, transpiration, and lateral drainage exceed the infiltration amount, the water flow will not leak into coarse-grained layer [

1,

2,

3]. In recent years, three-layer CBC with unsaturated drainage layer [

4,

5,

6,

7] or clay interlayer CBC [

8], and four layers(fine-coarse-fine-coarse) CBC [

9] have been proposed to improve CBC’s water storage capacity and lateral diversion. Therefore, CBC can be used in a wider range of engineering projects like landfill cover [

10,

11,

12,

13]

, farmland water storage [

14,

15,

16,

17]

, slope drainage layer [

18,

19,

20]

.

The CBC’s water storage capacity and lateral diversion are primarily controlled by the unsaturated hydraulic characteristics between fine-grained layer and coarse-grained layer. Specifically, the greater the difference in water-entry values between fine-grained layer and the coarse-grained layer, the stronger the water storage capacity and lateral diversion of the CBC. The water-entry value is mainly determined by the soil average pore size. Therefore, in engineering practice, significant differences in particle sizes are adopted for fine-grained layer, functional layer, and coarse-grained layer to achieve higher water storage capacity and stronger lateral diversion [

21,

22]. To prevent particles from the fine-grained layer and the functional layer from entering into the coarse-grained layer reduced water storage capacity and lateral diversion, geotechnical material isolation layers (referred to as the isolation layer) are typically installed between the fine-grained layer and the functional layer, as well as between the functional layer and the coarse-grained layer. However, coarse-grained layer may inevitably mixed with various fine-grained materials during transportation, stacking, and handling. Additionally, CBCs uneven settlement during construction and service, as well as agricultural activities and erosion by plants and animals, may damage isolation layer between different particle layers, leading to the mixture of fine particles into coarse-grained layer. Sun [

23] conducted indoor soil column tests to study the effect of different particle sizes of fine particles mixed into coarse particle layers on the water storage function of capillary barriers. Nevertheless, existing research has paid limited attention to the influence of different types of fine particles mixed into the coarse-grained layer on CBC water storage capacity.

In this paper, silt commonly used in the fine-grained layer of capillary barrier landfill covers and agricultural water retention layers, fine sand typically used in the fine-grained layer of slope surfaces, and diatomite, a water-retaining material in agriculture, were selected as the fine particles to be mixed with the coarse-grained layer to simulate fine particles entering the coarse-grained layer. Through one-dimensional (1D) permeability tests, the impact of mixing different types and amounts of fine particles into the coarse-grained layer on the water storage capacity was investigated. Based on the volumetric water content (VWC) variation patterns in the fine-grained layer and the distribution of matric potential, a failure criterion for CBC was proposed. Additionally, a rapid selection method for coarse-grained layer materials suitable for CBC engineering applications was developed.

2. Test Materials and Methods

2.1. Test Materials

In this paper, 0.25-0.5mm quartz sand was used as a fine-grained layer, and 2-5mm quartz sand was used as a coarse-grained layer base material. The fine particles mixed into the coarse-grained layer base material included 0.075-0.1mm quartz sand, silt from the Yellow River Delta(silt), and AG800 diatomite(diatomite), they all have similar particle sizes and had sizes smaller than the fine-grained layer particles size. The test materials’ basic physical properties are summarized in

Table 1.

2.2. Unsaturated Hydraulic Characteristics

The soil-water characteristic curves (SWCCs) and unsaturated hydraulic conductivity curves for test materials used are shown in

Figure 1. The SWCC were measured using capillary rise method, while the unsaturated hydraulic conductivity curves were fitted by the van Genuchten-Mualem model.

2.3. Experiment Apparatus

The 1D infiltration test apparatus, as illustrated in

Figure 2, is composed of three integral components: an acrylic glass column, a water supply system, and a data acquisition system.

The acrylic glass column has an inner diameter of 14.4 cm and a height of 50 cm. Five circular holes are symmetrically positioned on each side of the column wall for the installation of moisture meters and tensiometers. However, due to the large particle size of the coarse-grained layer, which could potentially damage the ceramic tips of the tensiometers, the tensiometers were not installed in this layer. Instead, the holes designated for tensiometers in the coarse-grained layer were sealed with waterproof tape. The moisture meters utilized are the SM150T from Delta-T, while the tensiometers are the T5x from METER. The specific performance indicators of the moisture meters and tensiometers are detailed in

Table 2.

The water supply system consists of a Mariotte bottle, a test bench, and a collection tank connected to the drainage outlet at the bottom of the acrylic glass column. The seepage velocity is controlled by adjusting the height of the test bench and the degree of valve opening. Water flows uniformly into the soil column through the permeable stone and porous plate at the top of the column, and eventually drains into the collection tank via the drainage outlet at the bottom of the acrylic glass column.

The data acquisition system utilizes the GP2 data logger from Delta-T to automatically collect data on VWC and matric suction. The moisture meters and tensiometers are secured in the circular holes on both sides of the acrylic glass column using neutral silicone sealant. The GP2 data logger is connected to a computer to enable real-time monitoring of the experimental data.

For the convenience of data processing and analysis in the following paper, the bottom of the soil column is taken as the reference plane, and the heights of the moisture meter and tensiometer profiles in the fine-grained layer from the reference plane are 15cm, 25cm, 35cm, and 45cm, respectively, referred to as the 15cm profile, 25cm profile, 35cm profile, and 45cm profile. Since the 15 cm profile is located 5 cm above the interface between the fine-grained and coarse-grained layers, the VWC and matric suction measured at this profile can be considered representative of the conditions at the fine-coarse grained layers interface. The moisture meter in the coarse-grained layer is located 5 cm below the interface between the fine-grained layer and the coarse-grained layer. The measurement range of the SM150T moisture meter is 3 cm around the probe, so the time when the moisture meter detects the VWC is considered the breakthrough time (Tbt) of the CBC.

2.4. Experiment Methods

In this paper, three types of admixtures were used: 0.075-0.1 mm quartz sand, silt, and diatomite, the three admixtures had similar particle sizes, all ranging from 0.075-0.1mm. For each admixture, the base material with four mixing ratios (by volume) was established: 1:0.1, 1:0.3, 1:0.6, and 1:1. Additionally, two control groups were set up: a capillary barrier column (CB) using 2-5 mm quartz sand as a coarse-grained layer and a homogeneous column (H) using 0.25-0.5 mm quartz sand. The objective was to investigate the impact of mixing different types and proportions of fine particles into the coarse-grained layer on CBC water storage capacity. The specific experimental design is detailed in

Table 3.

The fundamental physical properties of the coarse-grained layer after mixing the base material with the admixtures are presented in

Table 4. Following the proportion of admixtures into the base material, the saturated hydraulic conductivity decreases as the proportion of admixtures increases. The most significant reduction in saturated hydraulic conductivity is observed when silt is added. The maximum compaction density increases with the proportion of added 0.075-0.1 mm quartz sand and silt. In contrast, the maximum compaction density decreases with the proportion of added diatomite. This is attributed to the fact that the density of diatomite is approximately one-third that of quartz sand and silt, leading to a decrease in maximum compaction density as the proportion of diatomite increases.

3. Influence on Volumetric Water Content Changes and Distribution

Figure 3 delineates the variation in VWC within the coarse-grained layer (5 cm profile) during the permeation test, as influenced by the admixture of different proportions of 0.075-0.1 mm quartz sand, silt, and diatomite into the coarse-grained layer. As the proportion of these three admixtures in the coarse-grained layer increases, so does the VWC of the layer. When the admixtures are 0.075-0.1 mm quartz sand and silt, the VWC lies between that of the CB column and the H column. However, when the admixture is diatomite and the admixture ratio reaches 1:1, the VWC surpasses that of the H column.

Figure 4 depicts the temporal variation in VWC at the fine-coarse grained layers interface of CBC, mixing different proportions of 0.075-0.1 mm quartz sand, silt, and diatomite into the coarse-grained layer. At the moment of breakthrough, the CB column interface VWC has reached a steady state, whereas the H column has not achieved a stable VWC at breakthrough, which is one of the significant indicators of the presence of capillary barrier effects. When the proportion of 0.075-0.1 mm quartz sand, silt, and diatomite mixed into the coarse-grained layer is less or equal to 1:0.3, the interface VWC reaches a steady state at breakthrough time, but this stable VWC is less than CB column, indicating that the capillary barrier effect is weakened due to the addition of admixtures to coarse-grained layer. However, when the admixture ratio of 0.075-0.1 mm quartz sand, silt, and diatomite exceeds 1:0.3, the interface VWC fails to reach a steady state at the time of breakthrough, signifying the disappearance of the capillary barrier effect.

Figure 5,

Figure 6 and

Figure 7 depict the temporal variation in VWC at the 25 cm, 35 cm, and 45 cm profiles of CBC mixing different proportions of 0.075-0.1 mm quartz sand, silt, and diatomite into the coarse-grained layer. As the profile location gradually moves away from the fine-coarse grained layer interface, the difference in stable VWC between the CB column and the H column progressively diminishes, until at the 45 cm profile, the VWC of both becomes essentially the same, indicating the complete disappearance of the capillary barrier effect. The stable VWC of the CBC with the admixture of 0.075-0.1 mm quartz sand, silt, and diatomite to the coarse-grained layer lies between that of the H column and the CB column. The time required to reach stable VWC is longest for the admixture of silt, followed by diatomite, and shortest for the admixture of 0.075-0.1 mm quartz sand. This is because the permeability coefficient is the smallest after the admixture of silt into the coarse-grained layer, requiring a longer drainage time after the permeation test, whereas the permeability coefficient remains relatively large after the admixture of 0.075-0.1 mm quartz sand, necessitating a shorter drainage time (

Table 4).

In summary, the stabilization of VWC at the interface between fine-coarse grained layer interface at the time of breakthrough is a critical characteristic indicative of the presence of the capillary barrier effect. When the admixing fine particle size into the coarse-grained layer is smaller than the fine-grained layer, and the admixture ratio exceeds 1:0.3, the capillary barrier effect is invariably negated. The scope of the capillary barrier effect is confined to a certain area above the fine-coarse grained layer interface, and the closer to this interface, the more pronounced the capillary barrier effect becomes.

4. The Influence of Admixture Mixed into Coarse-Grained Layer on Fine-Grained Layer Matrix Potential Distribution

Figure 8 illustrates the matric potential distribution pattern in the fine-grained layer when the coarse-grained layer mixed with 0.075-0.1 mm quartz sand, silt, and diatomite. The matric potential distribution in the fine-grained layer of the H column forms a nearly vertical line (homogeneous linear type) with a large angle to the X-axis, indicating a relatively uniform distribution of VWC within the soil column. In contrast, the matric potential distribution in the fine-grained layer of the CB column forms a line at an approximate 45°angle to the X-axis (CBC linear type), suggesting that VWC is concentrated at the fine-coarse grained layer interface, consistent with the matric potential distribution pattern observed by Stormont and Morris (1998) in their study of CBC systems at steady state.

When 0.075-0.1 mm quartz sand is mixed into the coarse-grained layer (

Figure 8a), the matric potential distribution in the fine-grained layer at steady state transitions from CBC linear to homogeneous linear and back to CBC linear as the admixture ratio increases. At admixture ratios less than 1:0.3, the matric potential distribution is of the CBC linear type. When the admixture ratio reaches 1:0.6, it presents a homogeneous linear distribution, and the steady-state matric potential is significantly lower than that of the H column, because, the 2-5mm quartz sand used as coarse-grained layer in this paper’s porosity is 0.48, the admixture 1:0.6 is closest to its porosity resulting in the most uniform distribution of admixtures in the coarse-grained layer after mixing, Therefore, it has the greatest impact on the capillary barrier effect. As the admixture ratio further increases to 1:1, the steady-state matric potential distribution reverts to the CBC linear type. As shown in

Figure 4a, the capillary barrier effect disappears when the admixture ratio exceeds 1:0.3. At an admixture ratio of 1:0.6, the coarse-grained layer saturated hydraulic conductivity is similar to fine-grained layer (

Table 4), hence the matric potential exhibits a homogeneous linear distribution. When the admixture ratio reaches 1:1, the saturated hydraulic conductivity of the coarse-grained layer (1.06×10

-4cm/s) is two orders of magnitude lower than the fine-grained layer (4.11×10

-2cm/s), forming a hydraulic barrier (Li and Chang et al., 2013). The hydraulic barrier also serves to enhance water storage capacity, and its matric potential distribution exhibits a CBC linear pattern.

When silt (

Figure 8b) and diatomite (

Figure 8c) are mixed into the coarse-grained layer, the matric potential distribution in the fine-grained layer at steady state remains of the CBC linear type as the admixture ratio increases. This is because, at admixture ratios greater than 1:0.3, the saturated hydraulic conductivity of the coarse-grained layer with silt or diatomite is more than two orders of magnitude lower than the fine-grained layer (

Table 2 and

Table 4), forming a hydraulic barrier. Unlike the case with 0.075-0.1 mm quartz sand, there is no scenario where the coarse-grained layer saturated hydraulic conductivity becomes similar to the fine-grained layer. Therefore, the matric potential distribution in the fine-grained layer at steady state remains of the CBC linear type when silt or diatomite are mixed into the coarse-grained layer.

In summary, as the admixture ratio increases, the saturated hydraulic conductivity of the coarse-grained layer decreases. When the coarse-grained layer saturated hydraulic conductivity is similar to the fine-grained layer, the matric potential distribution in the fine-grained layer at steady state exhibits a homogeneous linear pattern. When the saturated hydraulic conductivity of the coarse-grained layer is either greater or less than that the fine-grained layer by one order of magnitude, the matric potential distribution in the fine-grained layer at steady state exhibits a CBC linear pattern.

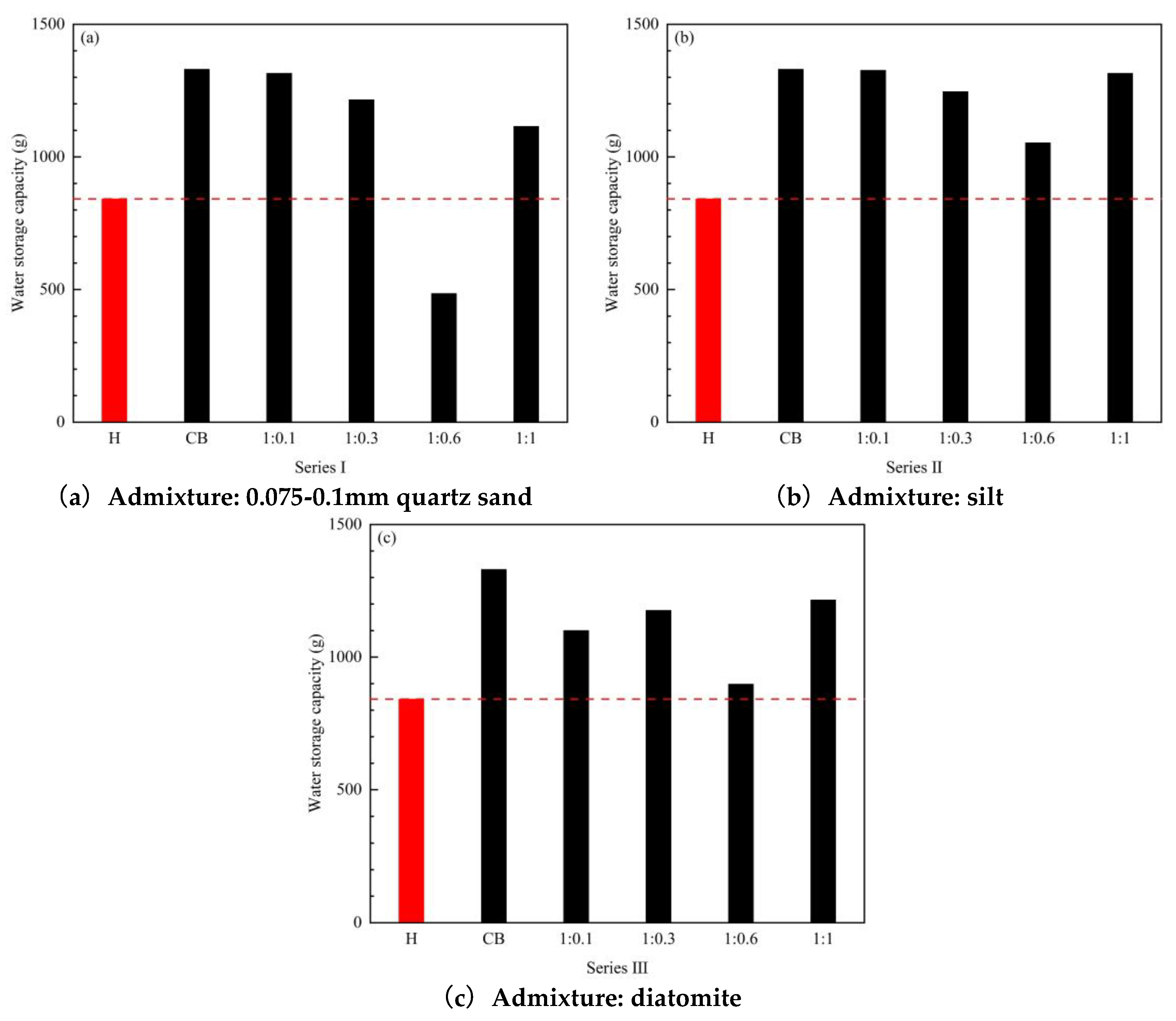

5. Variation of Water Storage Capacity

Figure 9 illustrates the impact of mixing 0.075-0.1mm quartz sand, silt, and diatomite into the coarse-grained layer on the water storage capacity of the CBC. As the admixture ratio increases, the water storage capacity initially decreases and then increases, reaching its minimum at an admixture ratio of 1:0.6. This indicates the existence of a most unfavorable admixture ratio at which the water storage capacity of the CBC is at its lowest, and this most unfavorable admixture ratio is independent of the admixture material.

When 0.075-0.1mm quartz sand is mixed into the coarse-grained layer (

Figure 9a), the water storage capacity at an admixture ratio of 1:0.6 is less than the homogeneous soil column. At this point, the hydraulic conductivity of the coarse-grained layer is similar to that of the 0.25-0.5 mm quartz sand used, and the matric potential distribution in the fine-grained layer at steady state is of the homogeneous linear type (

Figure 8a). At this stage, the CBC of the soil column fails, no hydraulic barrier is formed, and the matric potential is lower than that of the H column, resulting in a water storage capacity that is less than the homogeneous soil column.

When silt (

Figure 9b) and diatomite (

Figure 9c) are mixed into the coarse-grained layer, the water storage capacity is always greater than the homogeneous soil column. This is because, after the admixture ratio exceeds 1:0.3, the saturated hydraulic conductivity of the coarse-grained layer rapidly decreases to more than one order of magnitude lower than the fine-grained layer, forming a hydraulic barrier. Since the hydraulic barrier also serves to enhance water storage capacity, the water storage capacity with the admixture of silt and diatomite is always greater than homogeneous soil column.

6. Conclusions

This paper investigates the impact of admixing fine particles of different soil types into a coarse-grained layer on the water storage capacity of CBC through one-dimensional infiltration experiments. The main conclusions drawn are as follows:

(1) A rapid assessment method for the failure of capillary barrier has been proposed, based on the variation pattern of VWC at the fine-coarse grained layer interface. The strength of the capillary barrier effect can be quickly determined by observing the VWC changes at this interface upon breakthrough. If the VWC in the fine-grained layer within a 5 cm range above the interface does not change over time post-breakthrough, the capillary barrier effect is present, and its strength is proportional to the VWC. This scenario occurs when the admixture ratio of fine to coarse-grained materials is less than 0.3:1.

(2) A method for selecting materials for CBC based on saturated hydraulic conductivity has been introduced. An effective CBC can be formed when the saturated hydraulic conductivity of the coarse-grained layer is at least one order of magnitude greater than that of the fine-grained layer.

(3) When the mixed fine particle size in the coarse-grained layer is smaller than the fine-grained layer particle size, the CBC’s water storage performance is only affected by the proportion of fine particles added and is independent of the soil type in which the fine particles are mixed. The particle sizes of 0.075-0.1mm quartz sand, Yellow River Delta silt, and AG800 diatomite are similar, and the effect of mixing in coarse-grained layer on the CBC water storage capacity is also similar.

In summary, the VWC variation at fine-coarse grained layer interface can be used to quickly determine whether a CBC has failed. The CBC fails when the particle size of the fine particles in the coarse-grained layer is smaller than that in the fine-grained layer and the volume admixture ratio exceeds 0.3:1. If the absolute difference in saturated hydraulic conductivity between the fine and coarse-grained layers is less than one order of magnitude under these conditions, the matric potential distribution in the fine-grained layer at stability resembles that of a homogeneous soil column (homogeneous line type). As the fine particle content in the coarse-grained layer further increases (admixture ratio greater than 1:0.6), the saturated hydraulic conductivity of the coarse-grained layer becomes more than one order of magnitude less than that of the fine-grained layer, forming a hydraulic barrier.

Funding

The authors thank the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Nos.: 51779235 and 52078474) and Natural Science Foundation of Shandong Province (Grant No.: ZR2021MD021) for their support and assistance.

References

- Stormont, J.C.; Morris, C.E. Method to Estimate Water Storage Capacity of Capillary Barriers. Journal of Geotechnical and Geoenvironmental Engineering 1998, 124, 297–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Chang, S.; Salifu, F. Soil texture and layering effects on water and salt dynamics in the presence of a water table: A review. 2013.

- Zhan, L.T.; Qiu, Q.W.; Xu, W.J.; Chen, Y.M. Field measurement of gas permeability of compacted loess used as an earthen final cover for a municipal solid waste landfill. Journal of Zhejiang University-SCIENCE A.

- Morris, C.E.; Stormont, J.C. Parametric Study of Unsaturated Drainage Layers in a Capillary Barrier. Journal of Geotechnical and Geoenvironmental Engineering 1999, 125, 1057–1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong; Yang; Rahardjo; H. ; Leong; E.; C.; Fredlund; D.; G. A study of infiltration on three sand capillary barriers. Canadian Geotechnical Journal 2004, 41, 629–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, L.H.; Zhan, L.T.; Chen, Y.M.; Jia, G.W. Model tests on capillary-barrier cover with unsaturated drainage layer. Yantu Gongcheng Xuebao/Chinese Journal of Geotechnical Engineering 2012, 34, 75–80. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.; Li, X.; Wu, Y.; Gao, L. A novel unsaturated drainage layer in capillary barrier cover for slope protection. Bulletin of engineering geology and the environment 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, C.W.W.; Liu, J.; Chen, R.; Xu, J. Physical and numerical modeling of an inclined three-layer (silt/gravelly sand/clay) capillary barrier cover system under extreme rainfall. Waste Management 2015, 38, 210–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harnas, F.R.; Rahardjo, H.; Leong, E.C.; Wang, J.Y. Experimental study on dual capillary barrier using recycled asphalt pavement materials. Canadian Geotechnical Journal 2014, 51, 1165–1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kämpf, M.; Montenegro, H. On the performance of capillary barriers as landfill cover. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 1997, 1, 925–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bussière, B.; Aubertin, M.; Zhan, G. Design of Inclined Covers with Capillary Barrier Effect by S.-E. Parent and A. Cabral. Geotechnical and Geological Engineering 2007, 25, 673–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahardjo, H.; Satyanaga, A.; Harnas, F.R.; Leong, E.C. Use of Dual Capillary Barrier as Cover System for a Sanitary Landfill in Singapore. Indian Geotechnical Journal 2016, 46, 228–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hey, C.; Simms, P. Preliminary assessment of biosolids in covers with capillary barrier effects. Engineering Geology 2021, 280, 105973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ityel, E.; Ben-Gal, A.; Silberbush, M.; Lazarovitch, N. Increased root zone oxygen by a capillary barrier is beneficial to bell pepper irrigated with brackish water in an arid region. Agricultural Water Management 2014, 131, 108–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyake, M.; Otsuka, M.; Fujimaki, H.; Inoue, M.; Saito, H. Evaluation of an Artificial Capillary Barrier to Control Infiltration and Capillary Rise at Root Zone Areas. 2015.

- Menezes-Blackburn, D.; Al-Ismaily, S.; Al-Mayahi, A.; Al-Siyabi, B.; Al-Kalbani, A.; Al-Busaid, H.; Al-Naabi, I.; Al-Mazroui, M.; Al-Yahyai, R. Impact of a Nature-Inspired Engineered Soil Structure on Microbial Diversity and Community Composition in the Bulk Soil and Rhizosphere of Tomato Grown Under Saline Irrigation Water. Journal of Soil Science and Plant Nutrition 2021, 21, 173–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noguchi, K.; Saito, H.; Saefuddin, R.; Šimůnek, J. Evaluation of Subsurface Drip Irrigation Designs in a Soil Profile with a Capillary Barrier. Water 2021, 13, 1300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahardjo, H.; Krisdani, H.; Leong, E.C. APPLICATION OF UNSATURATED SOIL MECHANICS IN CAPILLARY BARRIER SYSTEM. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 3rd Asian Conference on Unsaturated Soils: 3rd Asian Conference on Unsaturated Soils April 21-23, 2007 Nanjing, China, 2007.

- Satyanaga, A.; Zhai, Q.; Rahardjo, H.; Gitirana, G.; Moon, S.-W.; Kim, J. Performance of capillary barrier as a sustainable slope protection; 2021; Volume 337.

- Ma, S.-k.; He, B.-f.; Ma, M.; Huang, Z.; Chen, S.-j.; Yue, H. Novel protection systems for the improvement in soil and water stability of expansive soil slopes. Journal of Mountain Science 2023, 20, 3066–3083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, M.J.; Azevedo, M.M.; Zornberg, J.G.; Palmeira, E.M. Capillary barriers incorporating non-woven geotextiles. Environmental Geotechnics 2018, 5, 168–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Zhou, X.; Liu, J. Long-Term Performance of the Water Infiltration and Stability of Fill Side Slope against Wetting in Expressways. Applied Sciences 2022, 12, 5809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, C.; Yang, J.; Liu, Q.; Wu, Y.; Miao, J. A Laboratory Investigation into the Effect of Coarse-Grained Layer Mixing with Fine Particles on the Water Storage Capacity of a Capillary Barrier Cover. Water 2025, 17, 183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).