Submitted:

30 July 2025

Posted:

31 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Ethics

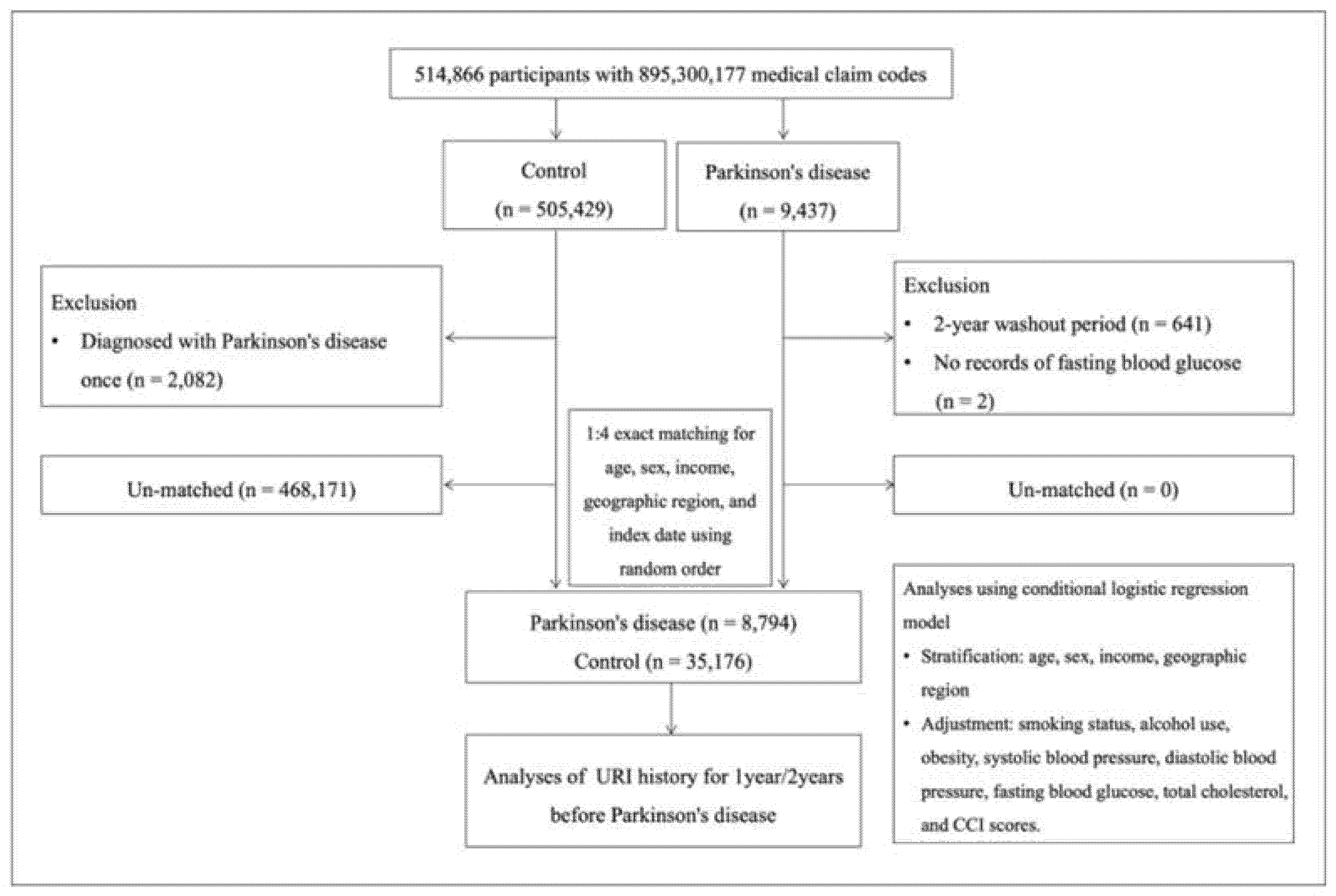

2.2. Study Design and Population

2.3. Exposure

2.4. Outcome

2.5. Covariates

2.6. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

| Characteristics | No. of PD |

No. of Control |

Odds Ratios for PD (95% Confidence Interval) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (exposure/total, %) | (exposure/total, %) |

Crude† | P-value | Model 1†‡ | P-value | Model 2†§ | P-value | ||

| Total (n = 43,970) | |||||||||

| No URI | 4,706/8,794 (53.5%) | 18,170/35,176 (51.7%) | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| ≥1 URI | 4,088/8,794 (46.5%) | 17,006/35,176 (48.4%) | 0.93 (0.89-0.97) |

0.002* |

0.92 (0.88-0.96) |

0.001* |

0.93 (0.88-0.97) |

0.001* |

|

| Age <65 years old (n = 8,380) | |||||||||

| No URI | 948/1,676 (56.6%) | 3,665/6,704 (54.7%) | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| ≥1 URI | 728/1,676 (43.4%) | 3,039/6,704 (45.3%) | 0.93 (0.83-1.03) |

0.163 |

0.93 (0.88-0.98) |

0.005* |

0.90 (0.80-1.00) |

0.059 |

|

| Age ≥65 years old (n = 35,590) | |||||||||

| No URI | 3,758/7,118 (52.8%) | 14,505/28,472 (50.9%) | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| ≥1 URI | 3,360/7,118 (47.2%) | 13,967/28,472 (49.1%) | 0.93 (0.88-0.98) |

0.005* |

0.94 (0.89-0.99) |

0.014* |

0.93 (0.88-0.98) |

0.009* |

|

| Men (n = 21,020) | |||||||||

| No URI | 2,308/4,204 (54.9%) | 9,215/16,816 (54.8%) | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| ≥1 URI | 1,896/4,204 (45.1%) | 7,601/16,816 (45.2%) | 1.00 (0.93-1.07) |

0.906 |

1.00 (0.94-1.08) |

0.905 |

0.99 (0.92-1.06) |

0.722 |

|

| Women (n = 22,950) | |||||||||

| No URI | 2,398/4,590 (52.2%) | 8,955/18,360 (48.8%) | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| ≥1 URI | 2,192/4,590 (47.8%) | 9,405/18,360 (51.2%) | 0.87 (0.82-0.93) |

<0.001* |

0.88 (0.82-0.94) |

<0.001* |

0.88 (0.82-0.94) |

<0.001* |

|

| Low income (n = 18,740) | |||||||||

| No URI | 2,044/3,748 (54.5%) | 7,757/14,992 (51.7%) | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| ≥1 URI | 1,704/3,748 (45.5%) | 7,235/14,992 (48.3%) | 0.89 (0.83-0.96) |

0.002* |

0.90 (0.84-0.97) |

0.005* |

0.88 (0.82-0.95) |

0.001* |

|

| High income (n = 25,230) | |||||||||

| No URI | 2,662/5,046 (52.8%) | 10,413/20,184 (51.6%) | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| ≥1 URI | 2,384/5,046 (47.3%) | 9,771/20,184 (48.4%) | 0.95 (0.90-1.02) |

0.139 |

0.96 (0.90-1.02) |

0.213 |

0.95 (0.90-1.02) |

0.148 |

|

| Urban residents (n = 16,630) | |||||||||

| No URI | 1,864/3,326 (56.0%) | 1,864/3,326 (56.0%) | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| ≥1 URI | 1,462/3,326 (44.0%) | 1,462/3,326 (44.0%) | 0.88 (0.82-0.95) |

0.001* |

0.89 (0.82-0.96) |

0.002* |

0.88 (0.81-0.95) |

0.001* |

|

| Rural residents (n = 27,340) | |||||||||

| No URI | 2,842/5,468 (52.0%) | 11,132/21,872 (50.9%) | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| ≥1 URI | 2,626/5,468 (48.0%) | 10,740/21,872 (49.1%) | 0.96 (0.90-1.02) |

0.154 |

0.97 (0.91-1.02) |

0.251 |

0.95 (0.90-1.01) |

0.122 |

|

| Underweight (n = 1,601) | |||||||||

| No URI | 179/318 (56.3%) |

720/1,283 (56.1%) | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| ≥1 URI | 139/318 (43.7%) |

563/1,283 (43.9%) | 0.99 (0.78-1.27) |

0.956 |

1.02 (0.79-1.31) |

0.871 |

0.98 (0.76-1.26) |

0.876 |

|

| Normal weight (n = 15,619) | |||||||||

| No URI | 1,659/3,098 (53.6%) | 6,563/12,521 (52.4%) | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| ≥1 URI | 1,439/3,098 (46.5%) | 5,958/12,521 (47.6%) | 0.96 (0.88-1.03) |

0.258 |

0.96 (0.89-1.04) |

0.357 |

0.96 (0.88-1.04) |

0.264 |

|

| Overweight (n = 11,597) | |||||||||

| No URI | 1,235/2,308 (53.5%) | 4,718/9,289 (50.8%) | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| ≥1 URI | 1,073/2,308 (46.5%) | 4,571/9,289 (49.2%) | 0.90 (0.82-0.98) |

0.019* |

0.90 (0.82-0.99) |

0.025* |

0.91 (0.84-0.99) |

0.022* |

|

| Obese (n = 15,153) | |||||||||

| No URI | 1,633/3,070 (53.2%) | 6,169/12,083 (51.1%) | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| ≥1 URI | 1,437/3,070 (46.8%) | 5,914/12,083 (48.9%) | 0.92 (0.85-0.99) |

0.034* |

0.92 (0.85-1.00) |

0.049* |

0.91 (0.84-0.99) |

0.022* |

|

| Nonsmokers (n = 32,653) | |||||||||

| No URI | 3,585/6,765 (53.0%) | 13,021/25,888 (50.3%) | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| ≥1 URI | 3,180/6,765 (47.0%) | 12,867/25,888 (49.7%) | 0.90 (0.85-0.95) |

<0.001* |

0.91 (0.86-0.96) |

<0.001* |

0.91 (0.86-0.96) |

<0.001* |

|

| Past and current smokers (n = 11,317) | |||||||||

| No URI | 1,121/2,029 (55.3%) | 5,149/9,288 (55.4%) | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| ≥1 URI | 908/2,029 (44.8%) | 4,139/9,288 (44.6%) | 1.01 (0.91-1.11) |

0.877 |

1.01 (0.92-1.12) |

0.784 |

0.99 (0.89-1.09) |

0.765 |

|

| Alcohol use <1 time a week (n = 29,538) | |||||||||

| No URI | 3,288/6,243 (52.7%) | 11,775/23,295 (50.6%) | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| ≥1 URI | 2,955/6,243 (47.3%) | 11,520/23,295 (49.5%) | 0.92 (0.87-0.97) |

0.003* |

0.93 (0.88-0.98) |

0.011* |

0.92 (0.87-0.98) |

0.005* |

|

| Alcohol use ≥1 time a week (n = 14,432) | |||||||||

| No URI | 1,418/2,551 (55.6%) | 6,395/11,881 (53.8%) | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| ≥1 URI | 1,133/2,551 (44.4%) | 5,486/11,881 (46.2%) | 0.93 (0.85-1.02) |

0.105 |

0.93 (0.85-1.02) |

0.105 |

0.93 (0.85-1.01) |

0.090 |

|

| SBP <140 mmHg and DBP <90 mmHg (n = 30,119) | |||||||||

| No URI | 2,937/5,669 (51.8%) | 12,343/24,450 (50.5%) | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| ≥1 URI | 2,732/5,669 (48.2%) | 12,107/24,450 (49.5%) | 0.95 (0.90-1.00) |

0.072 |

0.95 (0.90-1.01) |

0.077 |

0.93 (0.88-0.99) |

0.024* |

|

| SBP ≥140 mmHg or DBP ≥90 mmHg (n = 13,851) | |||||||||

| No URI | 1,769/3,125 (56.6%) | 5,827/10,726 (54.3%) | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| ≥1 URI | 1,356/3,125 (43.4%) | 4,899/10,726 (45.7%) | 0.91 (0.84-0.99) |

0.024* |

0.93 (0.86-1.01) |

0.096 |

0.93 (0.86-1.01) |

0.074 |

|

| Fasting blood glucose <100 mg/dL (n = 24,741) | |||||||||

| No URI | 2,409/4,613 (52.2%) | 10,164/20,128 (50.5%) | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| ≥1 URI | 2,204/4,613 (47.8%) | 9,964/20,128 (49.5%) | 0.93 (0.88-0.99) |

0.035* |

0.94 (0.88-1.00) |

0.043* |

0.93 (0.87-0.99) |

0.021* |

|

| Fasting blood glucose ≥100 mg/dL (n = 19,229) | |||||||||

| No URI | 2,297/4,181 (54.9%) | 8,006/15,048 (53.2%) | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| ≥1 URI | 1,884/4,181 (45.1%) | 7,042/15,048 (46.8%) | 0.93 (0.87-1.00) |

0.047* |

0.93 (0.87-1.00) |

0.056 |

0.92 (0.86-0.99) |

0.024* |

|

| Total cholesterol <200mg/dL (n = 25,002) | |||||||||

| No URI | 2,765/5,169 (53.5%) | 10,264/19,833 (51.8%) | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| ≥1 URI | 2,404/5,169 (46.5%) | 9,569/19,833 (48.3%) | 0.93 (0.88-0.99) |

0.026* |

0.94 (0.89-1.01) |

0.072 |

0.93 (0.88-0.99) |

0.034* |

|

| Total cholesterol ≥200mg/dL (n = 18,968) | |||||||||

| No URI | 1,941/3,625 (53.5%) | 1,941/3,625 (53.5%) | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| ≥1 URI | 1,684/3,625 (46.5%) | 1,684/3,625 (46.5%) | 0.92 (0.86-0.99) |

0.029* |

0.92 (0.86-0.99) |

0.033* |

0.91 (0.85-0.98) |

0.016* |

|

| CCI scores = 0 (n = 19,476) | |||||||||

| No URI | 1,404/2,649 (53.0%) | 8,765/16,827 (52.1%) | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| ≥1 URI | 1,245/2,649 (47.0%) | 8,062/16,827 (47.9%) | 0.96 (0.89-1.05) |

0.383 |

0.97 (0.90-1.06) |

0.537 |

0.97 (0.89-1.05) |

0.402 |

|

| CCI score = 1 (n = 8,897) | |||||||||

| No URI | 1,090/2,030 (53.7%) | 3,479/6,867 (50.7%) | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| ≥1 URI | 940/2,030 (46.3%) | 3,388/6,867 (49.3%) | 0.89 (0.80-0.98) |

0.016* |

0.89 (0.80-0.98) |

0.022* |

0.88 (0.80-0.98) |

0.015* |

|

| CCI score ≥2 (n = 15,597) | |||||||||

| No URI | 2,212/4,115 (53.8%) | 5,926/11,482 (51.6%) | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| ≥1 URI | 1,903/4,115 (46.3%) | 5,556/11,482 (48.4%) | 0.92 (0.85-0.99) |

0.018* |

0.91 (0.85-0.98) |

0.009* |

0.90 (0.84-0.97) |

0.005* |

|

| Characteristics | No. of PD |

No. of Control |

Odds Ratios for PD (95% Confidence Interval) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (exposure/total, %) | (exposure/total, %) | Crude† | P-value | Model 1†‡ | P-value | Model 2†§ | P-value | ||

| Total (n = 43,970) | |||||||||

| No URI | 6,168/8,794 (70.1%) | 24,047/35,176 (68.4%) | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| ≥2 URIs | 2,626/8,794 (29.9%) | 11,129/35,176 (31.6%) | 0.92 (0.87-0.97) |

0.001* |

0.91 (0.87-0.96) |

0.001* |

0.91 (0.87-0.96) |

0.001* |

|

| Age <65 years old (n = 8,380) | |||||||||

| No URI | 1,237/1,676 (73.8%) | 4,858/6,704 (72.5%) | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| ≥2 URIs | 439/1,676 (26.2%) | 1,846/6,704 (27.5%) | 0.93 (0.83-1.05) |

0.270 |

0.93 (0.82-1.05) |

0.263 |

0.90 (0.79-1.02) |

0.096 |

|

| Age ≥65 years old (n = 35,590) | |||||||||

| No URI | 4,931/7,118 (69.3%) | 19,189/28,472 (67.4%) | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| ≥2 URIs | 2,187/7,118 (30.7%) | 9,283/28,472 (32.6%) | 0.92 (0.87-0.97) | 0.002* | 0.92 (0.87-0.98) | 0.005* | 0.92 (0.87-0.97) | 0.003* | |

| Men (n = 21,020) | |||||||||

| No URI | 3,011/4,204 (71.6%) | 11,980/16,816 (71.2%) | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| ≥2 URIs | 1,193/4,204 (28.4%) | 4,836/16,816 (28.8%) | 0.98 (0.91-1.06) |

0.626 |

0.99 (0.92-1.07) |

0.770 |

0.97 (0.90-1.05) |

0.413 |

|

| Women (n = 22,950) | |||||||||

| No URI | 3,157/4,590 (68.8%) | 12,067/18,360 (65.7%) | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| ≥2 URIs | 1,433/4,590 (31.2%) | 6,293/18,360 (34.3%) | 0.87 (0.81-0.93) |

<0.001* |

0.88 (0.82-0.94) |

<0.001* |

0.87 (0.81-0.94) |

<0.001* |

|

| Low income (n = 18,740) | |||||||||

| No URI | 2,653/3,748 (70.8%) | 10,245/14,992 (68.3%) | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| ≥2 URIs | 1,095/3,748 (29.2%) | 4,747/14,992 (31.7%) | 0.89 (0.82-0.96) |

0.004* |

0.89 (0.83-0.97) |

0.006* |

0.87 (0.81-0.95) |

0.001* |

|

| High income (n = 25,230) | |||||||||

| No URI | 3,515/5,046 (69.7%) | 13,802/20,184 (68.4%) | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| ≥2 URIs | 1,531/5,046 (30.3%) | 6,382/20,184 (31.6%) | 0.94 (0.88-1.01) |

0.080 |

0.95 (0.89-1.01) |

0.120 |

0.94 (0.88-1.01) |

0.087 |

|

| Urban residents (n = 16,630) | |||||||||

| No URI | 2,380/3,326 (71.6%) | 9,219/13,304 (69.3%) | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| ≥2 URIs | 946/3,326 (28.4%) | 4,085/13,304 (30.7%) | 0.90 (0.82-0.98) |

0.011* |

0.90 (0.83-0.98) |

0.016* |

0.89 (0.82-0.97) |

0.008* |

|

| Rural residents (n = 27,340) | |||||||||

| No URI | 3,788/5,468 (69.3%) | 14,828/21,872 (67.8%) | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| ≥2 URIs | 1,680/5,468 (30.7%) | 7,044/21,872 (32.2%) | 0.93 (0.88-1.00) |

0.036* |

0.94 (0.88-1.00) |

0.054 |

0.93 (0.87-0.99) |

0.022* |

|

| Underweight (n = 1,601) | |||||||||

| No URI | 224/318 (70.4%) |

915/1,283 (71.3%) | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| ≥2 URIs | 94/318 (29.6%) |

368/1,283 (28.7%) | 1.04 (0.80-1.37) |

0.756 |

1.07 (0.82-1.41) |

0.623 |

1.04 (0.79 - 1.37) |

0.790 |

|

| Normal weight (n = 15,619) | |||||||||

| No URI | 2,193/3,098 (70.8%) | 8,702/12,521 (69.5%) | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| ≥2 URIs | 905/3,098 (29.2%) | 3,819/12,521 (30.5%) | 0.94 (0.86-1.03) |

0.162 |

0.95 (0.87-1.03) |

0.219 |

0.94 (0.86 - 1.02) |

0.143 |

|

| Overweight (n = 11,597) | |||||||||

| No URI | 1,615/2,308 (70.0%) | 6,234/9,289 (67.1%) | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| ≥2 URIs | 693/2,308 (30.0%) | 3,055/9,289 (32.9%) | 0.88 (0.79-0.97) |

0.009* |

0.88 (0.80-0.97) |

0.011* |

0.87 (0.79 - 0.96) |

0.006* |

|

| Obese (n = 15,153) | |||||||||

| No URI | 2,136/3,070 (69.6%) | 8,196/12,083 (67.8%) | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| ≥2 URIs | 934/3,070 (30.4%) | 3,887/12,083 (32.2%) | 0.92 (0.85-1.00) |

0.064 |

0.92 (0.85-1.01) |

0.066 |

0.91 (0.84 - 0.99) |

0.036* |

|

| Nonsmokers (n = 32,653) | |||||||||

| No URI | 4,716/6,765 (69.7%) | 17,404/25,888 (67.2%) | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| ≥2 URIs | 2,049/6,765 (30.3%) | 8,484/25,888 (32.8%) | 0.89 (0.84-0.94) |

<0.001* |

0.90 (0.85-0.96) |

0.001* |

0.90 (0.85-0.95) |

<0.001* |

|

| Past and current smokers (n = 11,317) | |||||||||

| No URI | 1,452/2,029 (71.6%) | 6,643/9,288 (71.5%) | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| ≥2 URIs | 577/2,029 (28.4%) | 2,645/9,288 (28.5%) | 1.00 (0.90-1.11) |

0.971 |

1.00 (0.90-1.11) |

0.994 |

0.97 (0.87-1.08) |

0.567 |

|

| Alcohol use <1 time a week (n = 29,538) | |||||||||

| No URI | 4,326/6,243 (69.3%) | 15,618/23,295 (67.0%) | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| ≥2 URIs | 1,917/6,243 (30.7%) | 7,677/23,295 (33.0%) | 0.90 (0.85-0.96) |

0.001* |

0.91 (0.86-0.97) |

0.002* |

0.90 (0.85-0.96) |

0.001* |

|

| Alcohol use ≥1 time a week (n = 14,432) | |||||||||

| No URI | 1,842/2,551 (72.2%) | 8,429/11,881 (71.0%) | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| ≥2 URIs | 709/2,551 (27.8%) | 3,452/11,881 (29.1%) | 0.94 (0.85-1.03) |

0.202 |

0.94 (0.85-1.04) |

0.215 |

0.94 (0.85-1.03) |

0.202 |

|

| SBP <140 mmHg and DBP <90 mmHg (n = 30,119) | |||||||||

| No URI | 3,912/5,669 (69.0%) | 16,491/24,450 (67.5%) | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| ≥2 URIs | 1,757/5,669 (31.0%) | 7,959/24,450 (32.6%) | 0.93 (0.87-0.99) |

0.024* |

0.93 (0.88-0.99) |

0.027* |

0.92 (0.86-0.98) |

0.007* |

|

| SBP ≥140 mmHg or DBP ≥90 mmHg (n = 13,851) | |||||||||

| No URI | 2,256/3,125 (72.2%) | 7,556/10,726 (70.5%) | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| ≥2 URIs | 869/3,125 (27.8%) | 3,170/10,726 (29.6%) | 0.92 (0.84-1.00) |

0.059 |

0.93 (0.85-1.02) |

0.117 |

0.93 (0.85-1.01) |

0.092 |

|

| Fasting blood glucose <100 mg/dL (n = 24,741) | |||||||||

| No URI | 3,184/4,613 (69.0%) | 13,599/20,128 (67.6%) | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| ≥2 URIs | 1,429/4,613 (31.0%) | 6,529/20,128 (32.4%) | 0.93 (0.87-1.00) |

0.056 |

0.94 (0.87-1.00) |

0.063 |

0.93 (0.86-0.99) |

0.034* |

|

| Fasting blood glucose ≥100 mg/dL (n = 19,229) | |||||||||

| No URI | 2,984/4,181 (71.4%) | 10,448/15,048 (69.4%) | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| ≥2 URIs | 1,197/4,181 (28.6%) | 4,600/15,048 (30.6%) | 0.91 (0.84-0.98) |

0.016* |

0.91 (0.84-0.98) |

0.016* |

0.90 (0.83-0.97) |

0.005* |

|

| Total cholesterol <200mg/dL (n = 25,002) | |||||||||

| No URI | 3,614/5,169 (69.9%) | 13,573/19,833 (68.4%) | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| ≥2 URIs | 1,555/5,169 (30.1%) | 6,260/19,833 (31.6%) | 0.93 (0.87-1.00) |

0.041* |

0.94 (0.88-1.01) |

0.092 |

0.93 (0.87-1.00) |

0.041* |

|

| Total cholesterol ≥200mg/dL (n = 18,968) | |||||||||

| No URI | 2,554/3,625 (70.5%) | 10,474/15,343 (68.3%) | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| ≥2 URIs | 1,071/3,625 (29.5%) | 4,869/15,343 (31.7%) | 0.90 (0.83-0.98) |

0.011* |

0.90 (0.83-0.97) |

0.009* |

0.89 (0.82-0.96) |

0.004* |

|

| CCI scores = 0 (n = 19,476) | |||||||||

| No URI | 1,853/2,649 (70.0%) | 11,669/16,827 (69.4%) | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| ≥2 URIs | 796/2,649 (30.1%) | 5,158/16,827 (30.7%) | 0.97 (0.89-1.06) |

0.532 |

0.99 (0.90-1.08) |

0.787 |

0.98 (0.9 - 1.07) |

0.664 |

|

| CCI score = 1 (n = 8,897) | |||||||||

| No URI | 1,440/2,030 (70.9%) | 4,590/6,867 (66.8%) | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| ≥2 URIs | 590/2,030 (29.1%) | 2,277/6,867 (33.2%) | 0.83 (0.74-0.92) |

0.001* |

0.82 (0.74-0.92) |

0.001* |

0.82 (0.73 - 0.91) |

<0.001* |

|

| CCI score ≥2 (n = 15,597) | |||||||||

| No URI | 2,875/4,115 (69.9%) | 7,788/11,482 (67.8%) | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| ≥2 URIs | 1,240/4,115 (30.1%) | 3,694/11,482 (32.2%) | 0.91 (0.84-0.98) |

0.016* |

0.90 (0.84-0.98) |

0.010* |

0.90 (0.83 - 0.97) |

0.006* |

|

| Characteristics | No. of PD |

No. of Control |

Odds Ratios for PD (95% Confidence Interval) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (exposure/total, %) |

(exposure/total, %) | Crude† | P-value | Model 1†‡ | P-value | Model 2†§ | P-value | ||

| Total (n = 43,970) | |||||||||

| No URI | 7,005/8,794 (79.7%) | 27,600/35,176 (78.5%) | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| ≥3 URIs | 1,789/8,794 (20.3%) | 7,576/35,176 (21.5%) | 0.93 (0.88-0.99) | 0.015* | 0.92 (0.87-0.98) | 0.006* | 0.92 (0.87-0.98) | 0.008* | |

| Age <65 years old (n = 8,380) | |||||||||

| No URI | 1,411/1,676 (84.2%) | 5,541/6,704 (82.7%) | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| ≥3 URIs | 265/1,676 (15.8%) | 1,163/6,704 (17.4%) | 0.89 (0.77-1.04) |

0.135 |

0.90 (0.77-1.04) |

0.151 |

0.87 (0.75-1.01) |

0.074 |

|

| Age ≥65 years old (n = 35,590) | |||||||||

| No URI | 5,594/7,118 (78.6%) | 22,059/28,472 (77.5%) | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| ≥3 URIs | 1,524/7,118 (21.4%) | 6,413/28,472 (22.5%) | 0.94 (0.88-1.00) |

0.044* |

0.94 (0.88-1.00) |

0.067 |

0.94 (0.88-1.00) |

0.041* |

|

| Men (n = 21,020) | |||||||||

| No URI | 3,399/4,204 (80.9%) | 13,544/16,816 (80.5%) | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| ≥3 URIs | 805/4,204 (19.2%) | 3,272/16,816 (19.5%) | 0.98 (0.90-1.07) |

0.651 |

0.99 (0.91-1.08) |

0.853 |

0.98 (0.89-1.06) |

0.581 |

|

| Women (n = 22,950) | |||||||||

| No URI | 3,606/4,590 (78.6%) | 14,056/18,360 (76.6%) | 1 |

1 |

1 |

||||

| ≥3 URIs | 984/4,590 (21.4%) | 4,304/18,360 (23.4%) | 0.89 (0.82-0.96) |

0.004* |

0.89 (0.83-0.97) |

0.005* |

0.89 (0.82-0.96) |

0.003* |

|

| Low income (n = 18,740) | |||||||||

| No URI | 2,997/3,748 (80.0%) | 11,766/14,992 (78.5%) | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| ≥3 URIs | 751/3,748 (20.0%) | 3,226/14,992 (21.5%) | 0.91 (0.84-1.00) |

0.047* |

0.92 (0.84-1.01) |

0.072 |

0.91 (0.83-0.99) |

0.032* |

|

| High income (n = 25,230) | |||||||||

| No URI | 4,008/5,046 (79.4%) | 15,834/20,184 (78.5%) | 1 |

1 |

1 |

||||

| ≥3 URIs | 1,038/5,046 (20.6%) | 4,350/20,184 (21.6%) | 0.94 (0.87-1.02) |

0.128 |

0.95 (0.88-1.02) |

0.168 |

0.94 (0.87-1.01) |

0.104 |

|

| Urban residents (n = 16,630) | |||||||||

| No URI | 2,677/3,326 (80.5%) | 10,464/13,304 (78.7%) | 1 |

1 |

1 |

||||

| ≥3 URIs | 649/3,326 (19.5%) | 2,840/13,304 (21.4%) | 0.89 (0.81-0.98) |

0.020* |

0.90 (0.82-0.99) |

0.031* |

0.89 (0.80-0.98) |

0.014* |

|

| Rural residents (n = 27,340) | |||||||||

| No URI | 4,328/5,468 (79.2%) | 17,136/21,872 (78.4%) | 1 |

1 |

1 |

||||

| ≥3 URIs | 1,140/5,468 (20.9%) | 4,736/21,872 (21.7%) | 0.95 (0.89-1.02) |

0.195 |

0.96 (0.89-1.03) |

0.252 |

0.95 (0.88-1.02) |

0.148 |

|

| Underweight (n = 1,601) | |||||||||

| No URI | 255/318 (80.2%) |

1,042/1,283 (81.2%) | 1 |

1 |

1 |

||||

| ≥3 URIs | 63/318 (19.8%) |

241/1,283 (18.8%) | 1.07 (0.78-1.46) |

0.676 |

1.09 (0.80-1.49) |

0.585 |

1.05 (0.77 - 1.44) |

0.769 |

|

| Normal weight (n = 15,619) | |||||||||

| No URI | 2,496/3,098 (80.6%) | 9,934/12,521 (79.3%) | 1 |

1 |

1 |

||||

| ≥3 URIs | 602/3,098 (19.4%) | 2,587/12,521 (20.7%) | 0.93 (0.84-1.02) |

0.129 |

0.94 (0.85-1.03) |

0.189 |

0.92 (0.84 - 1.02) |

0.122 |

|

| Overweight (n = 11,597) | |||||||||

| No URI | 1,833/2,308 (79.4%) | 7,155/9,289 (77.0%) | 1 |

1 |

1 |

||||

| ≥3 URIs | 475/2,308 (20.6%) | 2,134/9,289 (23.0%) | 0.87 (0.78-0.97) |

0.014* |

0.87 (0.78-0.97) |

0.015* |

0.86 (0.77 - 0.96) |

0.010* |

|

| Obese (n = 15,153) | |||||||||

| No URI | 2,421/3,070 (78.9%) | 9,469/12,083 (78.4%) | 1 |

1 |

1 |

||||

| ≥3 URIs | 649/3,070 (21.1%) | 2,614/12,083 (21.6%) | 0.97 (0.88-1.07) |

0.554 |

0.97 (0.88-1.07) |

0.550 |

0.96 (0.87 - 1.06) |

0.143 |

|

| Nonsmokers (n = 32,653) | |||||||||

| No URI | 5,355/6,765 (79.2%) | 20,129/25,888 (77.8%) | 1 |

1 |

1 |

||||

| ≥3 URIs | 1,410/6,765 (20.8%) | 5,759/25,888 (22.3%) | 0.92 (0.86-0.98) |

0.013* |

0.93 (0.87-0.99) |

0.032* |

0.92 (0.86-0.99) |

0.017* |

|

| Past and current smokers (n = 11,317) | |||||||||

| No URI | 1,650/2,029 (81.3%) | 7,471/9,288 (80.4%) | 1 |

1 |

1 |

||||

| ≥3 URIs | 379/2,029 (18.7%) | 1,817/9,288 (19.6%) | 0.94 (0.84-1.07) |

0.362 |

0.95 (0.84-1.07) |

0.397 |

0.92 (0.81-1.05) |

0.208 |

|

| Alcohol use <1 time a week (n = 29,538) | |||||||||

| No URI | 4,945/6,243 (79.2%) | 18,091/23,295 (77.7%) | 1 |

1 |

1 |

||||

| ≥3 URIs | 1,298/6,243 (20.8%) | 5,204/23,295 (22.3%) | 0.91 (0.85-0.98) |

0.009* |

0.92 (0.86-0.99) |

0.022* |

0.91 (0.85-0.98) |

0.008* |

|

| Alcohol use ≥1 time a week (n = 14,432) | |||||||||

| No URI | 2,060/2,551 (80.8%) | 9,509/11,881 (80.0%) | 1 |

1 |

1 |

||||

| ≥3 URIs | 491/2,551 (19.3%) | 2,372/11,881 (20.0%) | 0.96 (0.86-1.06) |

0.410 |

0.96 (0.86-1.07) |

0.419 |

0.95 (0.85-1.06) |

0.389 |

|

| SBP <140 mmHg and DBP <90 mmHg (n = 30,119) | |||||||||

| No URI | 4,471/5,669 (78.9%) | 19,009/24,450 (77.8%) | 1 |

1 |

1 |

||||

| ≥3 URIs | 1,198/5,669 (21.1%) | 5,441/24,450 (22.3%) | 0.94 (0.87-1.00) |

0.067 |

0.94 (0.87-1.00) |

0.065 |

0.92 (0.86-0.99) |

0.021* |

|

| SBP ≥140 mmHg or DBP ≥90 mmHg (n = 13,851) | |||||||||

| No URI | 2,534/3,125 (81.1%) | 8,591/10,726 (80.1%) | 1 |

1 |

1 |

||||

| ≥3 URIs | 591/3,125 (18.9%) | 2,135/10,726 (19.9%) | 0.94 (0.85-1.04) |

0.219 |

0.96 (0.87-1.06) |

0.426 |

0.95 (0.86-1.06) |

0.351 |

|

| Fasting blood glucose <100 mg/dL (n = 24,741) | |||||||||

| No URI | 3,655/4,613 (79.2%) | 15,699/20,128 (78.0%) | 1 |

1 |

1 |

||||

| ≥3 URIs | 958/4,613 (20.8%) | 4,429/20,128 (22.0%) | 0.93 (0.86-1.01) |

0.066 |

0.93 (0.86-1.01) |

0.083 |

0.92 (0.85-1.00) |

0.048* |

|

| Fasting blood glucose ≥100 mg/dL (n = 19,229) | |||||||||

| No URI | 3,350/4,181 (80.1%) | 11,901/15,048 (79.1%) | 1 |

1 |

1 |

||||

| ≥3 URIs | 831/4,181 (19.9%) | 3,147/15,048 (20.9%) | 0.94 (0.86-1.02) |

0.143 |

0.94 (0.86-1.02) |

0.152 |

0.92 (0.85-1.01) |

0.067 |

|

| Total cholesterol <200mg/dL (n = 25,002) | |||||||||

| No URI | 4,130/5,169 (79.9%) | 15,669/19,833 (79.0%) | 1 |

1 |

1 |

||||

| ≥3 URIs | 1,039/5,169 (20.1%) | 4,164/19,833 (21.0%) | 0.95 (0.88-1.02) |

0.158 |

0.96 (0.89-1.04) |

0.295 |

0.95 (0.88-1.02) |

0.158 |

|

| Total cholesterol ≥200mg/dL (n = 18,968) | |||||||||

| No URI | 2,875/3,625 (79.3%) | 11,931/15,343 (77.8%) | 1 |

1 |

1 |

||||

| ≥3 URIs | 750/3,625 (20.7%) | 3,412/15,343 (22.2%) | 0.91 (0.83-1.00) |

0.043* |

0.90 (0.83-0.99) |

0.028* |

0.90 (0.82-0.98) |

0.018* |

|

| CCI scores = 0 (n = 19,476) | |||||||||

| No URI | 2,104/2,649 (79.4%) | 13,397/16,827 (79.6%) | 1 |

1 |

1 |

||||

| ≥3 URIs | 2,104/2,649 (79.4%) | 13,397/16,827 (79.6%) | 1.01 (0.91-1.12) |

0.821 |

1.03 (0.93-1.14) |

0.524 |

1.03 (0.93 - 1.14) |

0.587 |

|

| CCI score = 1 (n = 8,897) | |||||||||

| No URI | 1,616/2,030 (79.6%) | 5,307/6,867 (77.3%) | 1 |

1 |

1 |

||||

| ≥3 URIs | 414/2,030 (20.4%) | 1,560/6,867 (22.7%) | 0.87 (0.77-0.98) |

0.027* |

0.88 (0.78-0.99) |

0.034* |

0.87 (0.77 - 0.99) |

0.029* |

|

| CCI score ≥2 (n = 15,597) | |||||||||

| No URI | 3,285/4,115 (79.8%) | 8,896/11,482 (77.5%) | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| ≥3 URIs | 830/4,115 (20.2%) | 2,586/11,482 (22.5%) | 0.87 (0.80-0.95) |

0.002* |

0.86 (0.79-0.94) |

0.001* |

0.86 (0.78 - 0.94) |

0.001* |

|

| Characteristics | No. of PD |

No. of Control |

Odds Ratios for PD (95% Confidence Interval) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (exposure/total, %) |

(exposure/total, %) |

Crude† | P-value | Model 1†‡ | P-value | Model 2†§ | P-value | ||

| Total (n = 43,970) | |||||||||

| No URI | 3,149/8,794 (35.8%) | 12,374/35,176 (35.2%) | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| ≥1 URI | 5,645/8,794 (64.2%) | 22,802/35,176 (64.8%) | 0.97 (0.93-1.02) |

0.267 |

0.96 (0.91-1.01) |

0.093 |

0.97 (0.92-1.01) |

0.162 |

|

| Age <65 years old (n = 8,380) | |||||||||

| No URI | 643/1,676 (38.4%) | 2,556/6,704 (38.1%) | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| ≥1 URI | 1,033/1,676 (61.6%) | 4,148/6,704 (61.9%) | 0.99 (0.89-1.11) |

0.857 |

1.00 (0.89-1.11) |

0.945 |

0.96 (0.85-1.07) |

0.449 |

|

| Age ≥65 years old (n = 35,590) | |||||||||

| No URI | 2,506/7,118 (35.2%) | 9,818/28,472 (34.5%) | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| ≥1 URI | 4,612/7,118 (64.8%) | 18,654/28,472 (65.5%) | 0.97 (0.92-1.02) |

0.250 |

0.98 (0.93-1.03) |

0.425 |

0.97 (0.92-1.02) |

0.256 |

|

| Men (n = 21,020) | |||||||||

| No URI | 1,608/4,204 (38.3%) | 6,475/16,816 (38.5%) | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| ≥1 URI | 2,596/4,204 (61.8%) | 10,341/16,816 (61.5%) | 1.01 (0.94-1.08) |

0.761 |

1.02 (0.95-1.10) |

0.526 |

1.00 (0.93-1.07) |

0.986 |

|

| Women (n = 22,950) | |||||||||

| No URI | 1,541/4,590 (33.6%) | 5,899/18,360 (32.1%) | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| ≥1 URI | 3,049/4,590 (66.4%) | 12,461/18,360 (67.9%) | 0.94 (0.87-1.00) |

0.062 |

0.94 (0.88-1.01) |

0.092 |

0.94 (0.87-1.00) |

0.061 |

|

| Low income (n = 18,740) | |||||||||

| No URI | 1,373/3,748 (36.6%) | 5,362/14,992 (35.8%) | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| ≥1 URI | 2,375/3,748 (63.4%) | 9,630/14,992 (64.2%) | 0.96 (0.89-1.04) |

0.321 |

0.97 (0.90-1.05) |

0.477 |

0.95 (0.88-1.02) |

0.153 |

|

| High income (n = 25,230) | |||||||||

| No URI | 1,776/5,046 (35.2%) | 7,012/20,184 (34.7%) | 1 |

1 |

1 |

||||

| ≥1 URI | 3,270/5,046 (64.8%) | 13,172/20,184 (65.3%) | 0.98 (0.92-1.05) |

0.543 |

0.99 (0.93-1.06) |

0.734 |

0.98 (0.92-1.04) |

0.488 |

|

| Urban residents (n = 16,630) | |||||||||

| No URI | 1,264/3,326 (38.0%) | 4,897/13,304 (36.8%) | 1 |

1 |

1 |

||||

| ≥1 URI | 2,062/3,326 (62.0%) | 8,407/13,304 (63.2%) | 0.95 (0.88-1.03) |

0.202 |

0.95 (0.88-1.03) |

0.235 |

0.94 (0.87-1.02) |

0.133 |

|

| Rural residents (n = 27,340) | |||||||||

| No URI | 1,885/5,468 (34.5%) | 7,477/21,872 (34.2%) | 1 |

1 |

1 |

||||

| ≥1 URI | 3,583/5,468 (65.5%) | 14,395/21,872 (65.8%) | 0.99 (0.93-1.05) |

0.688 |

1.00 (0.94-1.06) |

0.998 |

0.98 (0.92-1.05) |

0.553 |

|

| Underweight (n = 1,601) | |||||||||

| No URI | 135/318 (42.5%) |

505/1,283 (39.4%) | 1 |

1 |

1 |

||||

| ≥1 URI | 183/318 (57.6%) |

778/1,283 (60.6%) | 0.88 (0.69-1.13) |

0.314 |

0.90 (0.70-1.16) |

0.437 |

0.88 (0.68-1.13) |

0.309 |

|

| Normal weight (n = 15,619) | |||||||||

| No URI | 1,083/3,098 (35.0%) | 4,525/12,521 (36.1%) | 1 |

1 |

1 |

||||

| ≥1 URI | 2,015/3,098 (65.0%) | 7,996/12,521 (63.9%) | 1.05 (0.97-1.14) |

0.220 |

1.06 (0.98-1.15) |

0.153 |

1.05 (0.96-1.14) |

0.103 |

|

| Overweight (n = 11,597) | |||||||||

| No URI | 823/2,308 (35.7%) | 3,160/9,289 (34.0%) | 1 |

1 |

1 |

||||

| ≥1 URI | 1,485/2,308 (64.3%) | 6,129/9,289 (66.0%) | 0.93 (0.85-1.02) |

0.138 |

0.93 (0.85-1.03) |

0.166 |

0.92 (0.84-1.02) |

0.103 |

|

| Obese (n = 15,153) | |||||||||

| No URI | 1,108/3,070 (36.1%) | 4,184/12,083 (34.6%) | 1 |

1 |

1 |

||||

| ≥1 URI | 1,962/3,070 (63.9%) | 7,899/12,083 (65.4%) | 0.94 (0.86-1.02) |

0.129 |

0.94 (0.87-1.03) |

0.178 |

0.93 (0.85-1.01) |

0.077 |

|

| Nonsmokers (n = 32,653) | |||||||||

| No URI | 2,366/6,765 (35.0%) | 8,689/25,888 (33.6%) | 1 |

1 |

1 |

||||

| URI ≥ 1 | 4,399/6,765 (65.0%) | 17,199/25,888 (66.4%) | 0.94 (0.89-0.99) |

0.029* |

0.95 (0.90-1.01) |

0.086 |

0.95 (0.89-1.00) |

0.054 |

|

| Past and current smokers (n = 11,317) | |||||||||

| No URI | 783/2,029 (38.6%) | 3,685/9,288 (39.7%) | 1 |

1 |

1 |

||||

| ≥1 URI | 1,246/2,029 (61.4%) | 5,603/9,288 (60.3%) | 1.05 (0.95-1.15) |

0.367 |

1.06 (0.96-1.17) |

0.285 |

1.02 (0.92-1.13) |

0.692 |

|

| Alcohol use <1 time a week (n = 29,538) | |||||||||

| No URI | 2,190/6,243 (35.1%) | 7,914/23,295 (34.0%) | 1 |

1 |

1 |

||||

| ≥1 URI | 4,053/6,243 (64.9%) | 15,381/23,295 (66.0%) | 0.95 (0.90-1.01) |

0.102 |

0.97 (0.91-1.03) |

0.255 |

0.95 (0.90-1.01) |

0.109 |

|

| Alcohol use ≥1 time a week (n = 14,432) | |||||||||

| No URI | 959/2,551 (37.6%) | 4,460/11,881 (37.5%) | 1 |

1 |

1 |

||||

| ≥1 URI | 1,592/2,551 (62.4%) | 7,421/11,881 (62.5%) | 0.95 (0.90-1.01) |

0.109 |

1.00 (0.92-1.10) |

0.969 |

0.99 (0.90-1.08) |

0.822 |

|

| SBP <140 mmHg and DBP <90 mmHg (n = 30,119) | |||||||||

| No URI | 1,902/5,669 (33.6%) | 8,295/24,450 (33.9%) | 1 |

1 |

1 |

||||

| ≥1 URI | 3,767/5,669 (66.5%) | 16,155/24,450 (66.1%) | 1.02 (0.96-1.08) |

0.591 |

1.02 (0.96-1.08) |

0.541 |

1.00 (0.94-1.06) |

0.989 |

|

| SBP ≥140 mmHg or DBP ≥90 mmHg (n = 13,851) | |||||||||

| No URI | 1,247/3,125 (39.9%) | 4,079/10,726 (38.0%) | 1 |

1 |

1 |

||||

| ≥1 URI | 1,878/3,125 (60.1%) | 6,647/10,726 (62.0%) | 0.92 (0.85-1.00) |

0.058 |

0.95 (0.87-1.03) |

0.186 |

0.93 (0.86-1.01) |

0.094 |

|

| Fasting blood glucose <100 mg/dL (n = 24,741) | |||||||||

| No URI | 1,587/4,613 (34.4%) | 6,898/20,128 (34.3%) | 1 |

1 |

1 |

||||

| ≥1 URI | 3,026/4,613 (65.6%) | 13,230/20,128 (65.7%) | 0.99 (0.93-1.06) |

0.865 |

1.00 (0.93-1.07) |

0.961 |

0.99 (0.92-1.06) |

0.677 |

|

| Fasting blood glucose ≥100 mg/dL (n = 19,229) | |||||||||

| No URI | 1,562/4,181 (37.4%) | 5,476/15,048 (36.4%) | 1 |

1 |

1 |

||||

| ≥1 URI | 2,619/4,181 (62.6%) | 9,572/15,048 (63.6%) | 0.96 (0.89-1.03) |

0.248 |

0.96 (0.90-1.04) |

0.309 |

0.94 (0.88-1.01) |

0.101 |

|

| Total cholesterol <200mg/dL (n = 25,002) | |||||||||

| No URI | 1,861/5,169 (36.0%) | 7,019/19,833 (35.4%) | 1 |

1 |

1 |

||||

| ≥1 URI | 3,308/5,169 (64.0%) | 12,814/19,833 (64.6%) | 0.97 (0.91-1.04) |

0.411 |

0.99 (0.93-1.06) |

0.761 |

0.97 (0.91-1.04) |

0.419 |

|

| Total cholesterol ≥200mg/dL (n = 18,968) | |||||||||

| No URI | 1,288/3,625 (35.5%) | 5,355/15,343 (34.9%) | 1 |

1 |

1 |

||||

| ≥1 URI | 2,337/3,625 (64.5%) | 9,988/15,343 (65.1%) | 0.97 (0.90-1.05) |

0.474 |

0.97 (0.90-1.05) |

0.443 |

0.95 (0.88-1.03) |

0.234 |

|

| CCI scores = 0 (n = 19,476) | |||||||||

| No URI | 1,288/3,625 (35.5%) | 5,355/15,343 (34.9%) | 1 |

1 |

1 |

||||

| ≥1 URI | 2,337/3,625 (64.5%) | 9,988/15,343 (65.1%) | 1.03 (0.94-1.12) |

0.566 |

1.04 (0.95-1.13) |

0.394 |

0.96 (0.94-0.99) |

0.559 |

|

| CCI score = 1 (n = 8,897) | |||||||||

| No URI | 735/2,030 (36.2%) | 2,326/6,867 (33.9%) | 1 |

1 |

1 |

||||

| ≥1 URI | 1,295/2,030 (63.8%) | 4,541/6,867 (66.1%) | 0.90 (0.81-1.00) |

0.052 |

0.91 (0.82-1.01) |

0.075 |

0.90 (0.81 – 1.00) |

0.045* |

|

| CCI score ≥ 2 (n = 15,597) | |||||||||

| No URI | 1,477/4,115 (35.9%) | 3,999/11,482 (34.8%) | 1 |

1 |

1 |

||||

| ≥1 URI | 2,638/4,115 (64.1%) | 7,483/11,482 (65.2%) | 0.95 (0.89-1.03) |

0.218 |

0.94 (0.87-1.02) |

0.124 |

0.93 (0.87-1.01) |

0.074 |

|

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chaudhuri, K.R. and A.H. Schapira, Non-motor symptoms of Parkinson's disease: dopaminergic pathophysiology and treatment. The Lancet Neurology, 2009. 8(5): p. 464-474. [CrossRef]

- Federico, A., et al., Screening for mild cognitive impairment in Parkinson’s disease: comparison of the Italian versions of three neuropsychological tests. Parkinson’s disease, 2015. 2015(1): p. 681976. [CrossRef]

- Varalta, V., et al., Relationship between Cognitive Performance and Motor Dysfunction in Patients with Parkinson’s Disease: A Pilot Cross-Sectional Study. BioMed Research International, 2015. 2015(1): p. 365959. [CrossRef]

- Schrag, A., A. Sauerbier, and K.R. Chaudhuri, New clinical trials for nonmotor manifestations of Parkinson's disease. Movement Disorders, 2015. 30(11): p. 1490-1504. [CrossRef]

- Wang, H., et al., Bacterial, viral, and fungal infection-related risk of Parkinson's disease: Meta-analysis of cohort and case–control studies. Brain and behavior, 2020. 10(3): p. e01549. [CrossRef]

- Jain, N., R. Lodha, and S. Kabra, Upper respiratory tract infections. The Indian Journal of Pediatrics, 2001. 68: p. 1135-1138.

- Thomas, M. and P.A. Bomar, Upper respiratory tract infection. 2018.

- Desforges, M., et al., Human coronaviruses and other respiratory viruses: underestimated opportunistic pathogens of the central nervous system? viruses, 2019. 12(1): p. 14. [CrossRef]

- Hirsch, E.C. and S. Hunot, Neuroinflammation in Parkinson's disease: a target for neuroprotection? The Lancet Neurology, 2009. 8(4): p. 382-397. [CrossRef]

- Hirsch, E.C., S. Vyas, and S. Hunot, Neuroinflammation in Parkinson's disease. Parkinsonism & related disorders, 2012. 18: p. S210-S212.

- Lv, Y., et al., Phytic acid attenuates inflammatory responses and the levels of NF-κB and p-ERK in MPTP-induced Parkinson’s disease model of mice. Neuroscience letters, 2015. 597: p. 132-136. [CrossRef]

- Alam, Q., et al., Inflammatory process in Alzheimer’s and Parkinson's diseases: central role of cytokines. Current pharmaceutical design, 2016. 22(5): p. 541-548.

- Alby, K. and I. Nachamkin, Gastrointestinal infections. Microbiology Spectrum, 2016. 4(3): p. 10.1128/microbiolspec. dmih2-0005-2015. [CrossRef]

- Cookson, M.R., Mechanisms of mutant LRRK2 neurodegeneration. Leucine-Rich Repeat Kinase 2 (LRRK2), 2017: p. 227-239. [CrossRef]

- Deusenbery, C., Y. Wang, and A. Shukla, Recent innovations in bacterial infection detection and treatment. ACS Infectious Diseases, 2021. 7(4): p. 695-720. [CrossRef]

- Cannon, T. and S. Gruenheid, Microbes and Parkinson’s disease: from associations to mechanisms. Trends in Microbiology, 2022. 30(8): p. 749-760. [CrossRef]

- SCHULTZ, D.R., J.S. BARTHAL, and C. GARRETT, Western equine encephalitis with rapid onset of parkinsonism. Neurology, 1977. 27(11): p. 1095-1095. [CrossRef]

- Jang, H., et al., Viral parkinsonism. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA)-Molecular Basis of Disease, 2009. 1792(7): p. 714-721.

- Sulzer, D., et al., COVID-19 and possible links with Parkinson’s disease and parkinsonism: from bench to bedside. npj Parkinson's Disease, 2020. 6(1): p. 18. [CrossRef]

- Martyn, C. and C. Osmond, Parkinson's disease and the environment in early life. Journal of the neurological sciences, 1995. 132(2): p. 201-206. [CrossRef]

- Vlajinac, H., et al., Infections as a risk factor for Parkinson's disease: a case–control study. International Journal of Neuroscience, 2013. 123(5): p. 329-332. [CrossRef]

- Harris, M.A., et al., Association of Parkinson's disease with infections and occupational exposure to possible vectors. Movement disorders, 2012. 27(9): p. 1111-1117. [CrossRef]

- Cocoros, N.M., et al., Long-term risk of Parkinson disease following influenza and other infections. JAMA neurology, 2021. 78(12): p. 1461-1470. [CrossRef]

- Choi, H.G., et al., Tonsillectomy does not reduce upper respiratory infections: a national cohort study. PLoS One, 2016. 11(12): p. e0169264. [CrossRef]

- Von Economo, C., Encephalitis Lethargica, Us Sequelae and Treatment. Southern Medical Journal, 1931. 24(11): p. 1014.

- Ferrari, C.C. and R. Tarelli, Parkinson′ s disease and systemic inflammation. Parkinson’s disease, 2011. 2011(1): p. 436813. [CrossRef]

- Sawada, H., et al., Subclinical elevation of plasma C-reactive protein and illusions/hallucinations in subjects with Parkinson’s disease: case–control study. PLoS One, 2014. 9(1): p. e85886. [CrossRef]

- Bu, X.-L., et al., The association between infectious burden and Parkinson's disease: a case-control study. Parkinsonism & related disorders, 2015. 21(8): p. 877-881. [CrossRef]

- SASCO, A.J. and R.S. PAFFENBARGER JR, Measles infection and Parkinson's disease. American journal of epidemiology, 1985. 122(6): p. 1017-1031. [CrossRef]

- Levine, K.S., et al., Virus exposure and neurodegenerative disease risk across national biobanks. Neuron, 2023. 111(7): p. 1086-1093. e2. [CrossRef]

- Dardiotis, E., et al., H. pylori and Parkinson’s disease: Meta-analyses including clinical severity. Clinical neurology and neurosurgery, 2018. 175: p. 16-24. [CrossRef]

- Poskanzer, D.C. and R.S. Schwab, Cohort analysis of Parkinson's syndrome: evidence for a single etiology related to subclinical infection about 1920. Journal of chronic diseases, 1963. 16(9): p. 961-973. [CrossRef]

- Dourmashkin, R., What caused the 1918–30 epidemic of encephalitis lethargica? Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine, 1997. 90(9): p. 515-520.

- Bond, M., et al., A role for pathogen risk factors and autoimmunity in encephalitis lethargica? Progress in Neuro-Psychopharmacology and Biological Psychiatry, 2021. 109: p. 110276. [CrossRef]

- Estupinan, D., S. Nathoo, and M.S. Okun, The demise of Poskanzer and Schwab’s influenza theory on the pathogenesis of Parkinson’s disease. Parkinson’s Disease, 2013. 2013(1): p. 167843. [CrossRef]

- Smeyne, R.J., et al., Infection and risk of Parkinson’s disease. Journal of Parkinson's disease, 2021. 11(1): p. 31-43.

- Wu, W.Y., et al., Hepatitis C virus infection: a risk factor for P arkinson's disease. Journal of viral hepatitis, 2015. 22(10): p. 784-791.

- Abushouk, A.I., et al., Evidence for association between hepatitis C virus and Parkinson’s disease. Neurological Sciences, 2017. 38(11): p. 1913-1920. [CrossRef]

- McGee, D.J., X.-H. Lu, and E.A. Disbrow, Stomaching the possibility of a pathogenic role for Helicobacter pylori in Parkinson’s disease. Journal of Parkinson's disease, 2018. 8(3): p. 367-374. [CrossRef]

- Lotz, S.K., et al., Microbial infections are a risk factor for neurodegenerative diseases. Frontiers in Cellular Neuroscience, 2021. 15: p. 691136. [CrossRef]

- Limphaibool, N., et al., Infectious etiologies of parkinsonism: pathomechanisms and clinical implications. Frontiers in Neurology, 2019. 10: p. 652. [CrossRef]

- Maharaj, D., et al., Acetaminophen and aspirin inhibit superoxide anion generation and lipid peroxidation, and protect against 1-methyl-4-phenyl pyridinium-induced dopaminergic neurotoxicity in rats. Neurochemistry international, 2004. 44(5): p. 355-360. [CrossRef]

- Aubin, N., et al., Aspirin and salicylate protect against MPTP-induced dopamine depletion in mice. Journal of neurochemistry, 1998. 71(4): p. 1635-1642. [CrossRef]

- Sairam, K., et al., Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug sodium salicylate, but not diclofenac or celecoxib, protects against 1-methyl-4-phenyl pyridinium-induced dopaminergic neurotoxicity in rats. Brain Research, 2003. 966(2): p. 245-252. [CrossRef]

- Teismann, P. and B. Ferger, Inhibition of the cyclooxygenase isoenzymes COX-1 and COX-2 provide neuroprotection in the MPTP-mouse model of Parkinson's disease. Synapse, 2001. 39(2): p. 167-174.

- Teismann, P., et al., Cyclooxygenase-2 is instrumental in Parkinson's disease neurodegeneration. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 2003. 100(9): p. 5473-5478. [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Pernaute, R., et al., Selective COX-2 inhibition prevents progressive dopamine neuron degeneration in a rat model of Parkinson's disease. Journal of neuroinflammation, 2004. 1: p. 1-11. [CrossRef]

- Wang, T., et al., MPP+-induced COX-2 activation and subsequent dopaminergic neurodegeneration. The FASEB journal, 2005. 19(9): p. 1134-1136. [CrossRef]

- Carrasco, E., D. Casper, and P. Werner, Dopaminergic neurotoxicity by 6-OHDA and MPP+: differential requirement for neuronal cyclooxygenase activity. Journal of neuroscience research, 2005. 81(1): p. 121-131. [CrossRef]

- Przybyłkowski, A., et al., Cyclooxygenases mRNA and protein expression in striata in the experimental mouse model of Parkinson's disease induced by 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1, 2, 3, 6-tetrahydropyridine administration to mouse. Brain research, 2004. 1019(1-2): p. 144-151. [CrossRef]

- Bornebroek, M., et al., Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and the risk of Parkinson disease. Neuroepidemiology, 2007. 28(4): p. 193-196. [CrossRef]

- Bloem, B.R., M.S. Okun, and C. Klein, Parkinson's disease. The Lancet, 2021. 397(10291): p. 2284-2303. [CrossRef]

| Characteristics | Total Participants | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PD | Control | Standardized Difference | ||

| Age (years old) (n, %) | 0.00 | |||

| 40-44 | 5 (0.06) | 20 (0.06) | ||

| 45-49 | 66 (0.75) | 264 (0.75) | ||

| 50-54 | 224 (2.55) | 896 (2.55) | ||

| 55-59 | 498 (5.66) | 1,992 (5.66) | ||

| 60-64 | 883 (10.04) | 3,532 (10.04) | ||

| 65-69 | 1,347 (15.32) | 5,388 (15.32) | ||

| 70-74 | 1,950 (22.17) | 7,800 (22.17) | ||

| 75-79 | 2,122 (24.13) | 8,488 (24.13) | ||

| 80-84 | 1,293 (14.70) | 5,172 (14.70) | ||

| 85+ | 406 (4.62) | 1,624 (4.62) | ||

| Sex (n, %) | 0.00 | |||

| Male | 4,204 (47.81) | 16,816 (47.81) | ||

| Female | 4,590 (52.19) | 18,360 (52.19) | ||

| Income (n, %) | 0.00 | |||

| 1 (lowest) | 1,624 (18.47) | 6,496 (18.47) | ||

| 2 | 952 (10.83) | 3,808 (10.83) | ||

| 3 | 1,172 (13.33) | 4,688 (13.33) | ||

| 4 | 1,691 (19.23) | 6,764 (19.23) | ||

| 5 (highest) | 3,355 (38.15) | 13,420 (38.15) | ||

| Geographic region (n, %) | 0.00 | |||

| Urban | 3,326 (37.82) | 13,304 (37.82) | ||

| Rural | 5,468 (62.18) | 21,872 (62.18) | ||

| Obesity† (n, %) | 0.02 | |||

| Underweight | 318 (3.62) | 1,283 (3.65) | ||

| Normal | 3,098 (35.23) | 12,521 (35.60) | ||

| Overweight | 2,308 (26.25) | 9,289 (26.41) | ||

| Obese I | 2,772 (31.52) | 10,988 (31.24) | ||

| Obese II | 298 (3.39) | 1,095 (3.11) | ||

| Smoking status (n, %) | 0.09 | |||

| Nonsmoker | 6,765 (76.93) | 25,888 (73.60) | ||

| Past smoker | 1,200 (13.65) | 5,142 (14.62) | ||

| Current smoker | 829 (9.43) | 4,146 (11.79) | ||

| Alcohol use (n, %) | 0.10 | |||

| <1 time a week | 6,243 (70.99) | 23,295 (66.22) | ||

| ≥1 time a week | 2,551 (29.01) | 11,881 (33.78) | ||

| Systolic blood pressure (n, %) | 0.00 | |||

| <120 mmHg | 2,122 (24.13) | 8,156 (23.19) | ||

| 120-139 mmHg | 3,967 (45.11) | 17,428 (49.55) | ||

| ≥140 mmHg | 2,705 (30.76) | 9,592 (27.27) | ||

| Diastolic blood pressure (n, %) | 0.11 | |||

| <80 mmHg | 3,651 (41.52) | 16,604 (47.20) | ||

| 80-89 mmHg | 3,090 (35.14) | 12,529 (35.62) | ||

| ≥90 mmHg | 2,053 (23.35) | 6,043 (17.18) | ||

| Fasting blood glucose (n, %) | 0.11 | |||

| <100 mg/dL | 4,613 (52.46) | 20,128 (57.22) | ||

| 100-125 mg/dL | 2,918 (33.18) | 11,078 (31.49) | ||

| ≥126 mg/dL | 1,263 (14.36) | 3,970 (11.29) | ||

| Total cholesterol (n, %) | 0.05 | |||

| <200 mg/dL | 5,169 (58.78) | 19,833 (56.38) | ||

| 200-239 mg/dL | 2,501 (28.44) | 10,815 (30.75) | ||

| ≥240 mg/dL | 1,124 (12.78) | 4,528 (12.87) | ||

| CCI score (n, %) | 0.29 | |||

| 0 | 2,649 (30.12) | 16,827 (47.84) | ||

| 1 | 2,030 (23.08) | 6,867 (19.52) | ||

| ≥2 | 4,115 (46.79) | 11,482 (32.64) | ||

| The number of URIs (Mean, Standard deviation) | ||||

| within 1 year | 1.72 (3.89) | 1.67 (3.28) | 0.01 | |

| within 2 years | 3.50 (6.75) | 3.35 (5.66) | 0.02 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).