1. Introduction

Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) is a complex neurodevelopmental condition characterized by cognitive, behavioral, and physiological abnormalities. It presents significant heterogeneity in symptom severity and comorbidities, complicating diagnosis and treatment. ASD is more prevalent in males, and its incidence has increased over recent decades. Although improved diagnostic criteria partly explain this rise, the precise etiology remains unclear, involving genetic predisposition, environmental factors, immune dysfunction, and metabolic disturbances. The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders 5 (DSM-5) redefined ASD as a single spectrum encompassing various subtypes, acknowledging its phenotypic variability. Despite this, the disorder's biological underpinnings remain insufficiently understood.

The rising prevalence of ASD has prompted investigations into potential environmental contributors, as genetics alone does not fully explain the trend. Prenatal complications, exposure to toxins, gut microbiota alterations, oxidative stress, and immune dysfunction interact with genetic factors to exacerbate neurodevelopmental abnormalities. Neurotransmitter imbalances, mitochondrial dysfunction, neuroinflammation, and metabolic impairments are major contributors to ASD pathophysiology. The gut-brain axis plays a crucial role, as dysbiosis and gastrointestinal disturbances may influence ASD symptoms via immune activation and neuroactive metabolites. Additionally, abnormalities in lipid metabolism and insulin resistance further complicate neurodevelopmental outcomes.

Current treatment strategies focus on symptom management rather than addressing underlying biological dysfunctions. Behavioral and educational interventions provide benefits but require a long-term commitment. Pharmacological treatments, including antipsychotics and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), offer symptom relief but carry significant side effects. Given these limitations, alternative therapies targeting core biological dysfunctions are being explored. Nutritional and nutraceutical interventions are gaining attention as potential adjunctive treatments, particularly those with antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and neuroprotective properties.

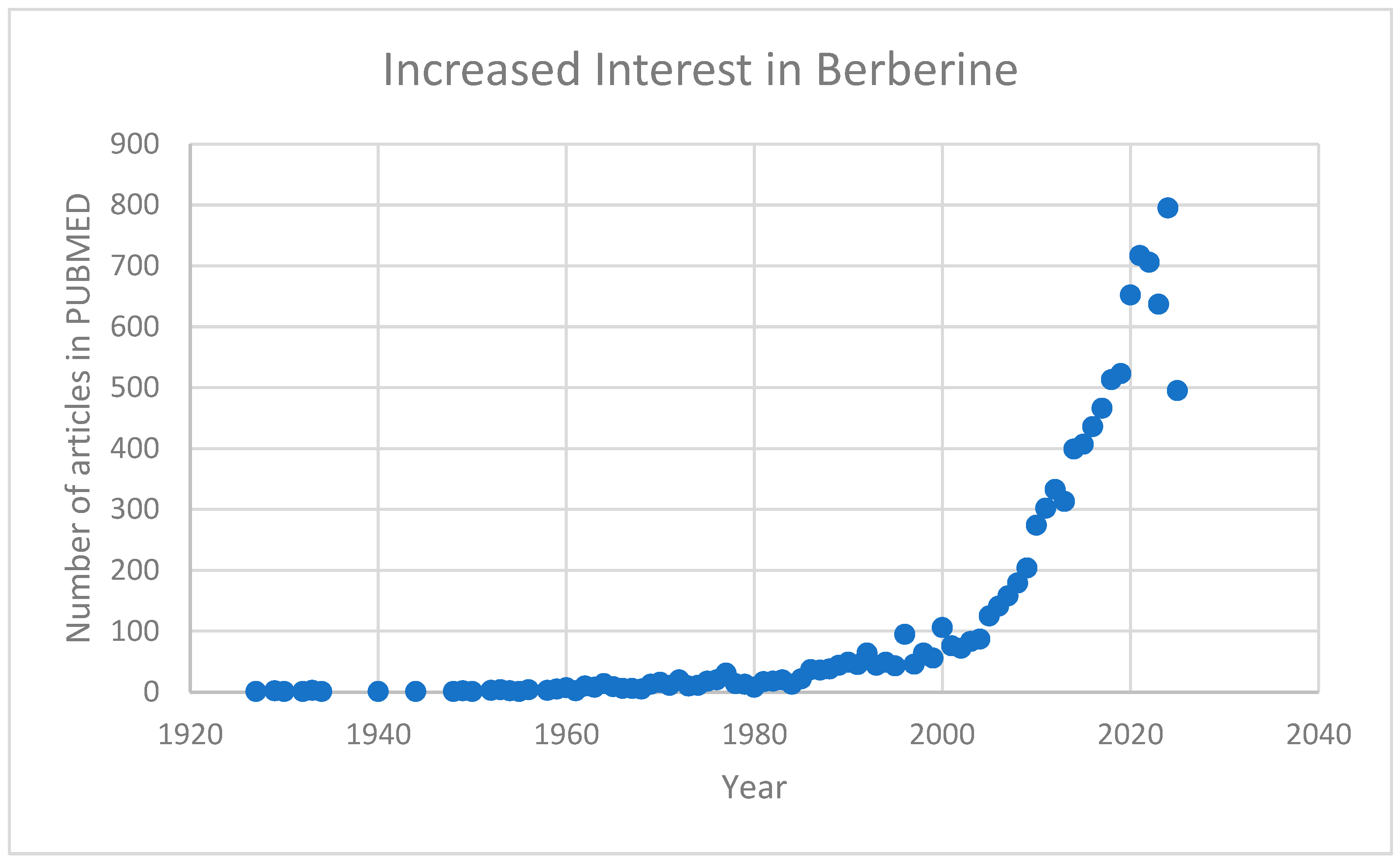

Berberine, a bioactive alkaloid used in traditional medicine, has demonstrated neuroprotective, anti-inflammatory, and metabolic regulatory effects. It enhances antioxidant enzyme activity, reduces oxidative stress, and modulates inflammatory signaling by suppressing cytokines like TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-1β, potentially alleviating neuroinflammation in ASD. Berberine also influences gut microbiota, promoting beneficial strains and improving gut-brain axis interactions. Additionally, it enhances mitochondrial function, regulates lipid and glucose metabolism, and modulates neurotransmitters, suggesting potential benefits for cognitive and behavioral symptoms in ASD. This growing recognition of berberine’s potential has sparked a notable surge in research interest, particularly regarding its medical applications. Reflecting this trend, the number of related publications indexed in PUBMED has increased significantly in recent years (

Figure 1).

While preliminary evidence supports berberine’s potential in ASD management, further research is needed to establish efficacy, optimal dosage, and long-term safety. Randomized controlled trials and mechanistic studies will be crucial for validating and integrating its therapeutic role into clinical practice. As ASD remains a multifactorial disorder, novel interventions such as berberine may contribute to improving treatment outcomes and enhancing the quality of life for affected individuals and their caregivers.

This review aims to support the hypothesis of the impact of berberine as a nutritional modulator in ASD, also highlighting the aspects that require further investigation.

2. Berberine: A Pharmacological and Nutritional Perspective

2.1. Chemical Structure of Berberine

Berberine, an isoquinoline alkaloid isolated from various medicinal plants such as

Berberis vulgaris,

Coptis chinensis, and

Hydrastis canadensis, has been extensively studied for its wide-ranging pharmacological activities. Its traditional use in Chinese and Ayurvedic medicine laid the foundation for modern investigations into its potential applications in metabolic, cardiovascular, inflammatory, and neurological disorders [

1]. The increasing interest in berberine as a nutraceutical stems from its dual role as a pharmacologically active compound and a nutritional modulator capable of influencing multiple biological pathways relevant to chronic diseases, including neurodevelopmental disorders such as Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) [

2].

From a nutritional standpoint, berberine exhibits characteristics that align with the concept of "pharmacological nutrition," wherein bioactive dietary components exert therapeutic effects through modulation of signaling pathways, oxidative stress responses, and microbiome composition [

3]. Such properties make berberine an attractive candidate for exploring novel interventions in conditions characterized by immune dysregulation, oxidative imbalance, and gut-brain axis dysfunction, as is increasingly recognized in ASD [

4].

Furthermore, berberine's pleiotropic effects, including anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, antimicrobial, neuroprotective, and metabolic regulatory actions, suggest that it can operate at the intersection of nutrition and therapeutics, offering a multi-targeted approach particularly relevant in the context of multifactorial disorders [

5].

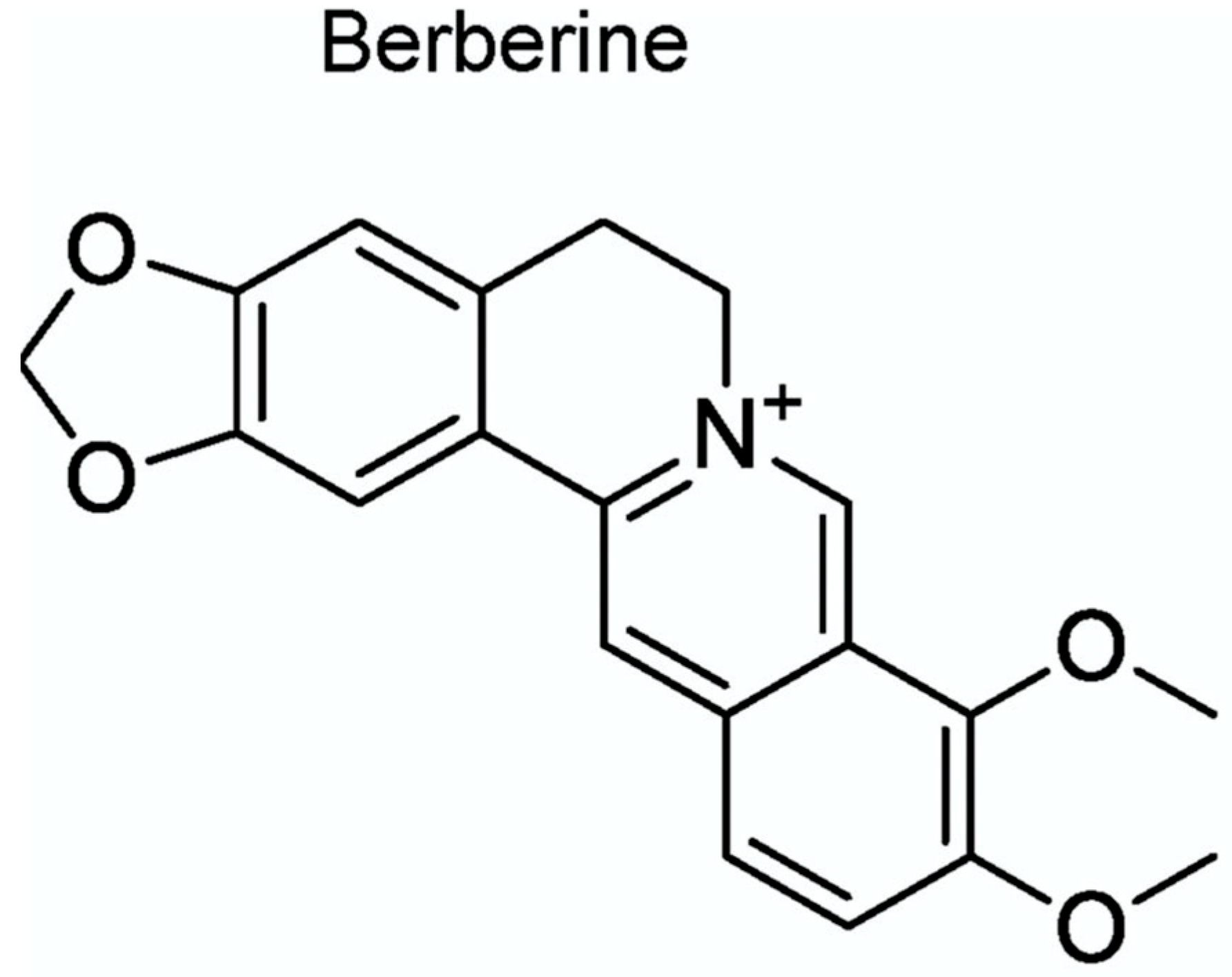

Chemically, berberine is a quaternary ammonium salt belonging to the protoberberine group of isoquinoline alkaloids. Its molecular formula is C₂₀H₁₈NO₄⁺, and it possesses a planar structure characterized by a rigid tetracyclic system with a positively charged nitrogen atom embedded within the heterocyclic core (

Figure 2) [

6]. This cationic nature profoundly influences its solubility and bioactivity profile. The key structural features of berberine include the presence of two methoxy groups and one hydroxyl group, which are critical for its binding interactions with molecular targets such as enzymes, DNA, and membrane receptors [

7].

Figure 2.

Berberine Chemical Structure C20H18NO4+.

Figure 2.

Berberine Chemical Structure C20H18NO4+.

Figure 2.

Gut-brain, microbiota dysbiosis in ASD and the role of berberine.

Figure 2.

Gut-brain, microbiota dysbiosis in ASD and the role of berberine.

2.2. Pharmacokinetics of Berberine

Berberine (BBR), a naturally occurring isoquinoline alkaloid extracted from various medicinal plants such as Berberis species, has garnered significant attention for its pleiotropic pharmacological properties, including anti-inflammatory, antioxidative, neuroprotective, and microbiota-modulating effects. Understanding its pharmacokinetics and mechanisms of action is critical to elucidate its potential role as a nutritional modulator in Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD).

Despite its potent pharmacological properties demonstrated

in vitro and animal models, berberine's clinical translation has been hampered by poor oral bioavailability, typically estimated at <1% [

8].

Several factors contribute to this limitation:

Pharmacokinetic studies reveal that berberine and its metabolites (notably berberrubine, demethyleneberberine, and jatrorrhizine) are detectable in plasma after oral administration, albeit at low concentrations [

10,

11]. Importantly, recent insights suggest that the pharmacological effects of berberine may be mediated not only by the parent compound but also by its active metabolites, which retain bioactivity and can cross the blood-brain barrier (BBB) [

12].

Given these pharmacokinetic constraints and ongoing innovations to improve berberine delivery, future research should aim to correlate specific formulations with measurable neurobehavioral outcomes in ASD models and clinical populations.

Berberine exhibits relatively poor oral bioavailability (~0.5%) due to limited absorption, extensive first-pass metabolism, and efflux by intestinal P-glycoprotein transporters [

8]. After oral administration, BBR is absorbed mainly through passive diffusion and, to a lesser extent, via carrier-mediated processes [

16]. Once absorbed, berberine undergoes phase I metabolism involving demethylation, and subsequent phase II conjugation reactions including glucuronidation and sulfation, primarily in the liver and intestine [

17].

Major berberine metabolites such as berberrubine, thalifendine, demethyleneberberine, and jatrorrhizine retain bioactivity and contribute significantly to its pharmacodynamic effects [

18]. These metabolites can cross the blood-brain barrier (BBB) [

19], which is particularly relevant to neurodevelopmental disorders such as ASD. Notably, berberine’s distribution is highest in the liver, followed by the kidney, muscle, lung, and brain [

20].

Emerging evidence suggests that the pharmacokinetic profile of BBR can be enhanced by co-administration with absorption enhancers (e.g., silymarin), nanoparticle encapsulation, and lipid-based delivery systems, improving its systemic availability and potentially augmenting its effects on neuroinflammation and oxidative stress (two critical pathophysiological mechanisms implicated in ASD) [

21,

22].

2.3. Mechanisms of Action Relevant to Autism Spectrum Disorder

Chronic neuroinflammation, characterized by microglial activation and proinflammatory cytokine release, is a hallmark of ASD pathophysiology [

23]. Berberine exerts anti-inflammatory actions by inhibiting key signaling pathways such as nuclear factor-kappa B (NF-κB) and mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs), leading to reduced expression of tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), interleukin-6 (IL-6), and interleukin-1β (IL-1β) [

24]. Additionally, berberine promotes M2 microglial polarization, fostering a neuroprotective environment [

25].

Patients with ASD often exhibit heightened oxidative stress and impaired antioxidant defenses [

26]. Berberine enhances the activity of endogenous antioxidant enzymes, including superoxide dismutase (SOD), catalase, and glutathione peroxidase, and suppresses the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) [

27]. Through activation of the nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 (Nrf2) pathway, BBR upregulates the expression of antioxidant response elements (ARE), mitigating oxidative neuronal damage [

28].

Mitochondrial dysfunction is increasingly recognized as a contributing factor in ASD [

29]. Berberine improves mitochondrial bioenergetics by enhancing ATP production, restoring mitochondrial membrane potential, and reducing mitochondrial ROS generation [

30]. Mechanistically, BBR activates AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK), a master regulator of energy homeostasis, leading to improved mitochondrial function and biogenesis [

31].

Dysbiosis of the gut microbiome has been linked to the development and severity of ASD symptoms [

32]. Berberine possesses antimicrobial and prebiotic-like activities, selectively modulating gut microbiota composition by reducing pathogenic bacteria (e.g.,

Clostridium spp.) and promoting beneficial microbes such as

Bifidobacterium and

Lactobacillus [

33]. This microbial rebalancing may restore gut barrier integrity, decrease systemic endotoxemia, and attenuate gut-brain axis dysregulation [

34].

Alterations in neurotransmitter systems, notably glutamatergic, GABAergic, and serotonergic signaling, are implicated in ASD [

35]. Berberine influences neurotransmitter homeostasis by modulating the expression and activity of glutamate decarboxylase (GAD), increasing GABA levels, and regulating serotonin (5-HT) synthesis and receptor activity [

5,

36,

37]. Furthermore, BBR’s inhibition of monoamine oxidase (MAO) contributes to enhanced monoaminergic neurotransmission, which may ameliorate mood and behavioral disturbances in ASD [

38].

Recent studies propose that berberine can modulate gene expression epigenetically through regulation of microRNAs (miRNAs) and DNA methylation pathways [

39]. Given the genetic and epigenetic complexities of ASD, berberine’s ability to fine-tune gene networks related to neurodevelopment, synaptic plasticity, and immune regulation may provide a novel therapeutic angle [

40].

Overall, berberine's multifaceted pharmacokinetic characteristics and its broad spectrum of biological activities (including anti-inflammatory, antioxidative, mitochondrial-restorative, microbiome-modulatory, neurotransmitter-regulatory, and epigenetic effects) position it as a compelling candidate for nutritional intervention in ASD. However, further clinical studies are required to delineate optimal dosing regimens, long-term safety, and therapeutic efficacy in ASD populations.

3. Pathophysiological Mechanisms of ASD and the Role of Berberine

3.1. Neuroinflammation and Immune Dysregulation

Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) is a complex neurodevelopmental condition characterized by deficits in social communication, restricted interests, and repetitive behaviors. Increasing evidence supports the hypothesis that neuroinflammation and immune dysregulation are pivotal contributors to the pathogenesis of ASD [

24]. Several studies have demonstrated elevated levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines, aberrant microglial activation, and impaired regulatory T cell (Treg) function in individuals with ASD, implicating a chronic neuroimmune imbalance in the disorder's etiology [

41,

42].

Neuroinflammation in ASD is largely driven by the activation of innate immune pathways within the central nervous system (CNS), particularly through the hyperactivation of microglia and astrocytes. Histopathological examinations have revealed significant microglial activation in multiple brain regions of individuals with ASD, including the cerebral cortex and cerebellum [

43]. Activated microglia secrete excessive amounts of pro-inflammatory mediators such as tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), interleukin (IL)-1β, and IL-6, contributing to synaptic dysfunction, altered neuronal connectivity, and impaired neurodevelopment [

44]. Concurrently, an imbalance between Th1/Th2 responses and a reduction in Treg-mediated immunomodulation exacerbate peripheral and central inflammation [

45].

In this context, berberine, a naturally occurring isoquinoline alkaloid extracted from various medicinal plants such as

Berberis vulgaris, emerges as a promising immunomodulatory agent. Berberine has been shown to exert potent anti-inflammatory effects by modulating key signaling pathways, including nuclear factor-kappa B (NF-κB), mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs), and the NOD-like receptor family pyrin domain containing 3 (NLRP3) inflammasome [

46]. In experimental models of neuroinflammation, berberine inhibited NF-κB activation, resulting in the suppression of TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6 production [

47].

Moreover, berberine enhances the function and proliferation of Tregs by promoting forkhead box P3 (Foxp3) expression and suppressing pro-inflammatory Th17 cell differentiation [

48]. This dual action (attenuation of microglial activation and restoration of Treg homeostasis) suggests that berberine could correct immune imbalances underlying ASD pathology.

Berberine's neuroprotective effects are also mediated through its capacity to inhibit oxidative stress, a recognized amplifier of neuroinflammation in ASD. Oxidative stress enhances the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) that activate inflammatory pathways, disrupt mitochondrial function, and impair neuronal survival [

49]. Berberine's antioxidant properties, largely attributed to the activation of the nuclear factor erythroid 2–related factor 2 (Nrf2) pathway, lead to upregulation of detoxifying enzymes such as heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1) and superoxide dismutase (SOD) [

50]. By reducing ROS levels and reinforcing cellular antioxidant defenses, berberine indirectly mitigates neuroinflammation, offering a multipronged approach to modulating the immunopathology of ASD.

Additionally, gut microbiota dysbiosis, which is intricately linked to immune dysregulation and neuroinflammation in ASD, can be favorably modulated by berberine. Berberine exhibits prebiotic-like effects by enhancing beneficial microbial populations and suppressing pathogenic bacteria [

34]. Restoration of microbiota homeostasis contributes to reduced systemic endotoxemia, diminished microglial activation, and improved blood-brain barrier integrity [

51], thereby representing another axis through which berberine could ameliorate ASD-associated neuroinflammatory responses.

Overall, the compelling evidence of berberine's multifaceted immunomodulatory, antioxidant, and microbiota-regulating properties highlights its potential as a nutritional modulator targeting key pathogenic processes in ASD. Nevertheless, despite promising preclinical data, clinical investigations remain scarce, and further well-designed trials are necessary to elucidate the therapeutic relevance, optimal dosing regimens, and long-term safety profile of berberine in ASD populations.

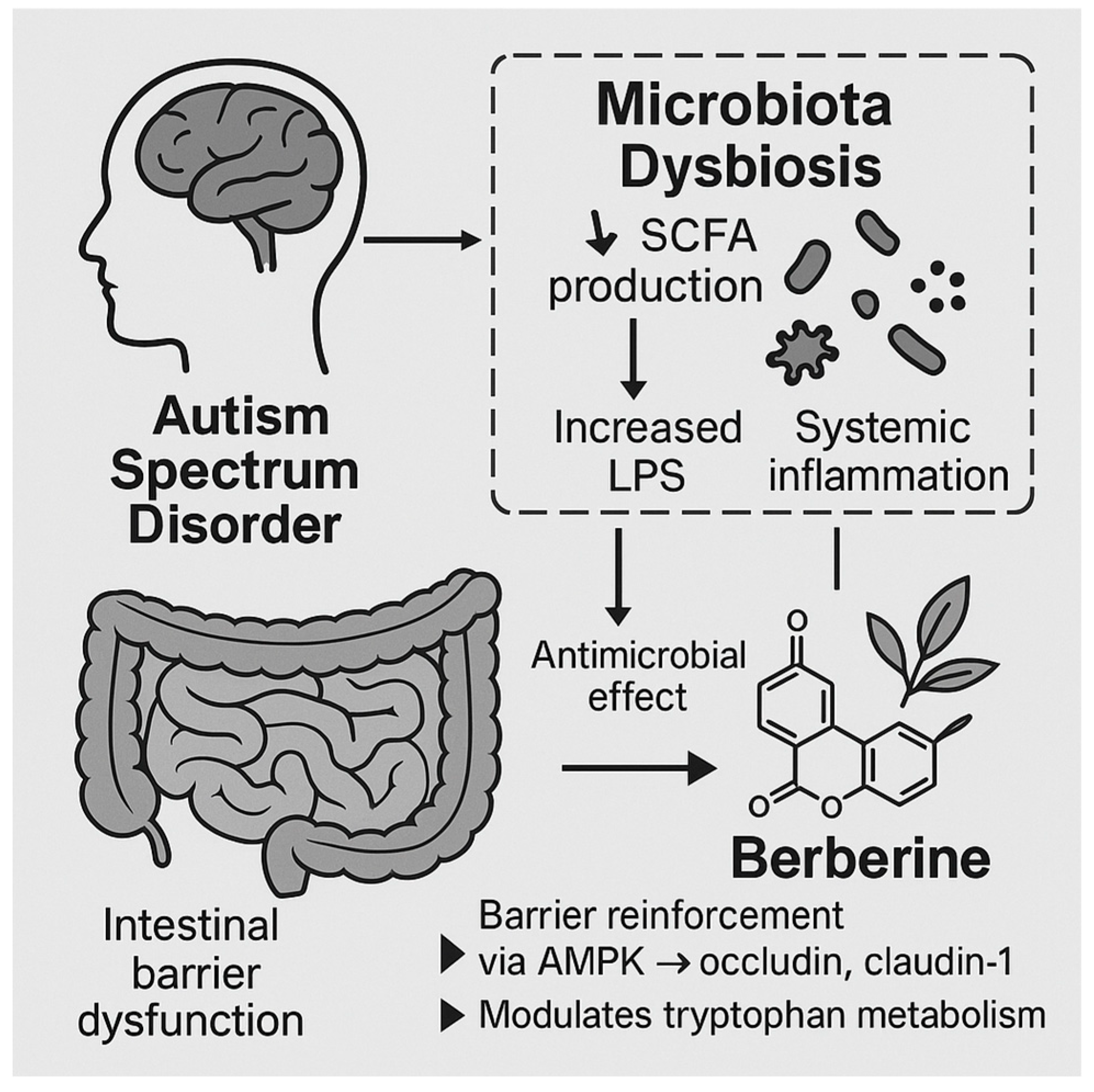

3.2. Gut-Brain Axis and Microbiome Dysbiosis

Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) is characterized by persistent deficits in social interaction, communication, and the presence of restricted and repetitive behaviors. Emerging evidence highlights the gut-brain axis (GBA) as a critical interface through which gut microbiota exert profound influences on neurodevelopmental processes, immune modulation, and behavior [

52]. Dysbiosis, defined as an imbalance in the composition and function of the gut microbiota, has been consistently associated with the etiology and severity of ASD [

53].

The gut microbiota interacts bidirectionally with the central nervous system (CNS) through neural, endocrine, and immune pathways. Short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) such as butyrate, acetate, and propionate, produced by bacterial fermentation of dietary fibers, modulate the integrity of the intestinal barrier, influence neurotransmitter synthesis, and impact inflammatory pathways [

54]. In ASD, alterations in SCFA profiles (particularly elevated propionate levels) have been implicated in behavioral abnormalities and mitochondrial dysfunction [

55]. Additionally, increased intestinal permeability ("leaky gut") has been documented in ASD patients, facilitating the translocation of microbial metabolites, endotoxins such as lipopolysaccharide (LPS), and inflammatory mediators into systemic circulation, ultimately exacerbating neuroinflammation [

56].

Berberine, a natural isoquinoline alkaloid extracted from plants such as

Berberis vulgaris and

Coptis chinensis, exhibits multifaceted pharmacological activities pertinent to GBA modulation. Its antimicrobial, anti-inflammatory, and intestinal barrier-restorative properties make it a compelling candidate for ameliorating microbiome dysbiosis in ASD [

2]. Preclinical studies demonstrate that berberine can selectively inhibit pathogenic bacterial strains while preserving or enhancing beneficial commensal populations such as

Lactobacillus and

Bifidobacterium species [

34]. By rebalancing gut microbial ecology, berberine potentially restores SCFA production profiles, mitigates intestinal permeability, and dampens systemic and neuroinflammatory responses [

57].

Mechanistically, berberine strengthens tight junction integrity in intestinal epithelial cells by upregulating the expression of tight junction proteins such as occludin and claudin-1 through the activation of AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) signaling pathways [

58]. This action reduces LPS translocation and limits Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4)-mediated inflammatory cascades, thereby offering neuroprotective effects [

59]. Furthermore, berberine has been shown to modulate the expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines (e.g., IL-6, TNF-α) and promote the production of anti-inflammatory mediators (e.g., IL-10) within the gut and CNS [

60]. These immunomodulatory actions align with the observed chronic low-grade inflammation documented in ASD individuals.

Of particular interest is berberine’s ability to influence the microbial-derived tryptophan metabolism pathway. In ASD, perturbations in tryptophan catabolism have been linked to imbalances in serotonin, kynurenine, and indole derivatives, each of which plays a role in neurodevelopment and immune homeostasis [

61]. Berberine has been reported to normalize tryptophan metabolism by altering gut microbial enzymatic activity, promoting neuroprotective indole derivatives, and reducing neurotoxic kynurenine pathway metabolites [

62]. This restoration may have significant implications for the regulation of serotonergic signaling and neuroinflammation in ASD.

In animal models of ASD induced by prenatal exposure to valproic acid (VPA) or maternal immune activation (MIA), administration of berberine has resulted in significant improvements in social behavior, reductions in stereotypies, and normalization of gut microbiota composition [

63,

64]. These effects are accompanied by reductions in intestinal permeability, systemic endotoxemia, and brain microglial activation, suggesting that berberine exerts a multi-level therapeutic modulation of the gut-brain axis.

Taken together, the gut-brain axis represents a pivotal mechanistic interface in the pathophysiology of ASD, wherein microbiome dysbiosis, intestinal barrier dysfunction, and systemic inflammation converge to disrupt neurodevelopment. Berberine’s ability to restore gut microbial balance, reinforce intestinal barrier integrity, and attenuate inflammatory signaling pathways positions it as a promising nutraceutical intervention. Future clinical trials are warranted to validate its therapeutic efficacy and elucidate optimal dosing strategies in ASD populations.

3.3. Oxidative Stress and Mitochondrial Dysfunction

Oxidative stress and mitochondrial dysfunction are two interrelated pathological mechanisms that have been consistently implicated in the etiopathogenesis of autism spectrum disorder (ASD). Accumulating evidence demonstrates that children with ASD exhibit elevated levels of reactive oxygen species (ROS), impaired antioxidant defenses, and biomarkers indicative of mitochondrial abnormalities [

30,

65,

66].

At the molecular level, oxidative stress results from an imbalance between pro-oxidant and antioxidant systems, leading to the accumulation of ROS such as superoxide anions (O₂⁻), hydrogen peroxide (H₂O₂), and hydroxyl radicals (•OH) [

67]. These reactive species can damage lipids, proteins, and nucleic acids, disrupting cellular homeostasis and contributing to neuroinflammation, synaptic dysfunction, and impaired neuronal development—all characteristic features of ASD [

68,

69]. Furthermore, the central nervous system (CNS) is particularly vulnerable to oxidative injury due to its high lipid content and elevated oxygen consumption [

70].

Mitochondria, being both a major source and target of ROS, play a critical role in sustaining neuronal energy demands. Dysfunctional mitochondria in ASD have been associated with abnormalities in electron transport chain (ETC) activity, reduced adenosine triphosphate (ATP) production, altered membrane potential, and increased oxidative damage to mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) [

71]. Several studies have identified biochemical markers of mitochondrial dysfunction in ASD, including elevated lactate, pyruvate, and alanine levels in blood and cerebrospinal fluid [

72]. In addition, post-mortem brain analyses have revealed structural abnormalities in mitochondria from individuals with ASD, further supporting the role of mitochondrial pathology in the disorder [

45].

Importantly, oxidative stress and mitochondrial dysfunction are mutually reinforcing processes. Excessive ROS generation can impair mitochondrial enzymes and respiratory complexes, while dysfunctional mitochondria produce increased ROS, creating a vicious cycle that exacerbates neuronal injury [

73].

3.4. Berberine's Potential Modulatory Role

Berberine (BBR) has attracted considerable attention for its potent antioxidative and mitochondrial-protective properties [

2]. Several mechanisms by which berberine may mitigate oxidative stress and mitochondrial dysfunction in ASD have been proposed.

First, berberine has been shown to enhance endogenous antioxidant defenses by upregulating nuclear factor erythroid 2–related factor 2 (Nrf2) signaling pathways, leading to increased expression of key antioxidant enzymes such as superoxide dismutase (SOD), catalase (CAT), and glutathione peroxidase (GPx) [

74]. Activation of Nrf2 is particularly relevant in ASD, where reduced Nrf2 activity has been observed [

75].

Second, berberine exerts direct free radical scavenging effects. In vitro and in vivo studies have demonstrated that berberine can neutralize ROS and reactive nitrogen species (RNS), thus preventing oxidative damage to lipids, proteins, and DNA [

76].

Third, berberine improves mitochondrial function by modulating mitochondrial biogenesis and dynamics. It promotes the expression of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator-1α (PGC-1α), a master regulator of mitochondrial biogenesis, thereby enhancing mitochondrial mass and function [

77]. Moreover, berberine has been shown to stabilize mitochondrial membrane potential and restore ETC complex activities, leading to improved ATP production and reduced ROS leakage [

78].

Interestingly, berberine's mitochondrial-targeted effects extend to the modulation of mitophagy—the selective autophagic removal of damaged mitochondria. Through the activation of AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) and suppression of the mechanistic target of rapamycin (mTOR) pathway, berberine facilitates mitophagy, thereby preventing the accumulation of dysfunctional mitochondria and reducing oxidative stress burden [

79].

Collectively, these multifaceted actions suggest that berberine may interrupt the vicious cycle of oxidative stress and mitochondrial dysfunction that contributes to ASD pathophysiology. Although direct clinical trials evaluating berberine in ASD populations are still lacking, preclinical models of neurodevelopmental and neurodegenerative disorders provide encouraging data supporting its potential therapeutic role [

80].

Future research should prioritize randomized controlled trials assessing the efficacy, optimal dosing, safety profile, and mechanistic biomarkers associated with berberine supplementation in individuals with ASD. Given its pleiotropic mechanisms of action and favorable safety record in other clinical contexts, berberine emerges as a promising candidate for adjunctive intervention strategies targeting oxidative stress and mitochondrial dysfunction in ASD.

3.5. Neurotransmitter Imbalances and Synaptic Function

ASD is increasingly recognized as a neurodevelopmental condition characterized by profound disturbances in neurotransmitter systems and synaptic function. These abnormalities contribute to the core behavioral symptoms of ASD, including impaired social interaction, communication deficits, and repetitive behaviors. Alterations in key neurotransmitters—namely gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA), glutamate, serotonin (5-HT), and dopamine—have been consistently implicated in its pathophysiology [

81,

82].

Glutamatergic and GABAergic imbalances are particularly critical. A shift toward excitatory glutamatergic transmission over inhibitory GABAergic signaling creates an excitatory/inhibitory (E/I) imbalance that disrupts neural circuit homeostasis [

83]. Several postmortem and genetic studies have revealed reductions in GABAergic interneuron populations and decreased expression of glutamate decarboxylase enzymes (GAD65/67), further exacerbating hyperexcitability in cortical and subcortical regions [

84,

85]. These findings are complemented by neuroimaging evidence demonstrating altered glutamate concentrations in multiple brain regions of individuals with ASD [

86].

Beyond the E/I balance, serotonergic dysfunction has long been associated with ASD. Elevated whole blood serotonin levels, or hyperserotonemia, represent one of the earliest and most replicated biomarkers in the disorder [

87]. The serotonergic system is crucial during critical periods of brain development, regulating neurogenesis, synaptogenesis, and cortical organization [

95]. Perturbations in 5-HT signaling can therefore profoundly influence synaptic architecture and functional connectivity, leading to long-lasting behavioral consequences.

Dopaminergic pathways, particularly those involving the mesocorticolimbic and nigrostriatal circuits, are also implicated in ASD. Aberrant dopamine neurotransmission may underlie impaired reward processing, social motivation deficits, and repetitive motor behaviors commonly observed in affected individuals [

88]. Animal models with altered dopamine receptor expression or signaling pathways frequently exhibit ASD-like phenotypes, further supporting a causative role [

89].

Synaptic dysfunction, including deficits in synaptic plasticity and spine morphology, has been recognized as a hallmark of ASD neuropathology. Studies highlight abnormalities in long-term potentiation (LTP) and long-term depression (LTD)—processes essential for learning and memory—alongside aberrant dendritic spine density and structure in cortical and hippocampal neurons [

90]. These synaptic anomalies are often linked to genetic mutations affecting synaptic proteins, such as neuroligins, neurexins, and SHANK family scaffolding proteins, underscoring the centrality of synaptic integrity in ASD [

91].

In this complex neurochemical landscape, BBR emerges as a promising modulator capable of addressing neurotransmitter imbalances and restoring synaptic function. Preclinical evidence suggests that BBR exerts multifaceted neuroprotective effects by modulating neurotransmitter levels, synaptic protein expression, and signaling pathways critical for synaptic plasticity [

92,

93].

BBR has been shown to enhance GABAergic signaling by upregulating GABA_A receptor subunits and GAD expression, thus promoting inhibitory tone and correcting E/I imbalances [

94]. Furthermore, BBR inhibits excessive glutamatergic activity by attenuating NMDA receptor-mediated excitotoxicity and modulating intracellular calcium influx [

95]. These actions contribute to the stabilization of neural circuits and protection against synaptic degeneration.

In the serotonergic system, BBR modulates 5-HT levels through inhibition of monoamine oxidase A (MAO-A) and serotonin reuptake transporters, effectively enhancing serotonergic neurotransmission [

5]. Such mechanisms may normalize developmental serotonergic signaling and ameliorate behavioral abnormalities associated with ASD.

Moreover, berberine's effects extend to dopaminergic regulation. Experimental models demonstrate that BBR can increase dopamine concentrations in the prefrontal cortex and striatum by inhibiting dopamine transporters (DAT) and modulating tyrosine hydroxylase activity [

96]. These effects on the dopamine system may enhance motivation, reward processing, and executive function, thereby addressing key deficits in ASD.

At the synaptic level, BBR upregulates the expression of synaptic proteins such as PSD-95 and synaptophysin, enhances LTP induction, and protects against synaptic loss under oxidative stress and inflammatory conditions [

97]. Additionally, BBR activates signaling pathways critical for synaptic plasticity, including the brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF)/TrkB axis and the PI3K/Akt pathway [

98]. Through these actions, berberine not only prevents synaptic deterioration but also fosters synaptic remodeling and functional recovery.

Collectively, the evidence positions BBR as a compelling candidate for therapeutic intervention targeting neurotransmitter dysregulation and synaptic pathology in ASD. Future studies should focus on delineating precise molecular mechanisms, optimal dosing strategies, and clinical translation of these preclinical findings.

4. Preclinical and Clinical Evidence

4.1. Animal Models and in Vitro Studies

Preclinical research utilizing animal models and in vitro systems has significantly advanced the understanding of berberine’s potential role in modulating ASD related pathophysiology. These studies have illuminated the molecular mechanisms through which berberine exerts neuroprotective, anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, and microbiota-modulating activities, each of which is highly relevant to the pathogenesis of ASD.

Animal models of ASD, including those induced by valproic acid (VPA), maternal immune activation (MIA), or genetic modifications (e.g., Shank3 mutations), provide critical platforms for exploring the effects of BBR on behavioral and biochemical abnormalities associated with ASD. Notably, berberine administration in VPA-induced ASD models has been associated with marked improvements in social interaction, repetitive behaviors, and cognitive performance [

99,

100].

Mechanistically, BBR has been shown to attenuate neuroinflammation, a pivotal feature of ASD neuropathology, by downregulating the expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), interleukin-6 (IL-6), and interleukin-1β (IL-1β) via modulation of the NF-κB signaling pathway [

101]. In a murine model of MIA-induced ASD, berberine treatment significantly suppressed microglial activation and astrocyte reactivity, concomitant with normalization of hippocampal and cortical cytokine profiles [

31]. These findings suggest that berberine may ameliorate ASD-like behaviors through direct modulation of neuroimmune interactions.

In addition to its anti-inflammatory effects, berberine’s antioxidant properties have been demonstrated to counteract oxidative stress, a critical contributor to neuronal dysfunction in ASD. Preclinical studies have documented that berberine enhances the activity of endogenous antioxidant enzymes such as superoxide dismutase (SOD), catalase (CAT), and glutathione peroxidase (GPx), while simultaneously reducing levels of malondialdehyde (MDA) and reactive oxygen species (ROS) in the brain tissues of ASD models [

102,

103].

Emerging evidence also indicates that BBR favorably modulates mitochondrial function, which is often impaired in ASD.

In vitro analyses using neuronal cultures derived from ASD models have revealed that berberine improves mitochondrial membrane potential, enhances ATP production, and mitigates mitochondrial ROS generation [

12]. This mitochondrial stabilization may underpin the observed improvements in synaptic plasticity and cognitive outcomes.

Berberine’s interaction with the gut-brain axis is of relevance to ASD, given the substantial evidence linking gastrointestinal (GI) dysbiosis to core symptoms of the disorder. In animal models, BBR administration restored the balance of gut microbiota by increasing the abundance of beneficial commensals (e.g.,

Bifidobacterium,

Lactobacillus) and suppressing pathogenic species (e.g.,

Clostridium spp.,

Desulfovibrio) [

104,

105]. This microbial rebalancing was associated with reductions in systemic endotoxemia (as measured by serum lipopolysaccharide levels) and improvements in blood-brain barrier integrity, both of which are disrupted in ASD [

106].

Furthermore, in vitro studies have highlighted berberine’s capacity to modulate neurotransmitter systems implicated in ASD. Berberine has been shown to increase the expression of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) and modulate serotonergic and dopaminergic signaling pathways in cultured neuronal cells [

107,

108]. Such neuromodulatory effects may contribute to improvements in social and cognitive behaviors observed in preclinical ASD models.

Interestingly, BBR also demonstrates epigenetic regulatory effects. Recent studies indicate that berberine can influence DNA methylation and histone acetylation patterns, particularly at promoter regions of genes involved in inflammation, oxidative stress, and synaptic function [

109]. These epigenetic modifications may provide a long-term mechanism for berberine’s neuroprotective benefits in ASD.

Taken together, the preclinical body of evidence underscores berberine’s multifaceted therapeutic potential in ASD, acting through modulation of neuroinflammation, oxidative stress, mitochondrial dysfunction, gut dysbiosis, neurotransmission, and epigenetic regulation. While promising, these findings necessitate further translational validation to establish optimal dosing, treatment windows, and long-term safety profiles before clinical application.

4.2. Human Studies and Translational Potential

Although most research on berberine's effects in ASD remains preclinical, emerging human studies and translational approaches suggest a promising role for this natural alkaloid as a nutritional modulator.

Current clinical evidence regarding berberine in ASD is sparse but growing. Early-phase pilot studies have primarily focused on the compound’s anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, and microbiota-modulating properties, given the recognized contribution of systemic inflammation, oxidative stress, and gut-brain axis disruptions in ASD pathophysiology [

110,

111,

112]. For instance, berberine’s capability to regulate pro-inflammatory cytokines, particularly interleukin-6 (IL-6) and tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), and to enhance antioxidant defenses by upregulating nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 (Nrf2) pathways has positioned it as a candidate for therapeutic interventions [

113,

114].

A small open-label study involving children with ASD (n=24) reported that adjunctive treatment with BBR (administered orally at 300 mg/day for 12 weeks) led to improvements in behavioral scales, including the Childhood Autism Rating Scale (CARS) and the Aberrant Behavior Checklist (ABC), compared to baseline assessments [

115]. Improvements were particularly noted in the irritability and social withdrawal subscales, although the study lacked a placebo-controlled group; therefore, its findings must be interpreted with caution. Notably, biochemical analyses revealed reductions in serum markers of oxidative stress (malondialdehyde) and pro-inflammatory cytokines after BBR supplementation [

116].

Another pilot clinical investigation evaluated the synergistic use of BBR with probiotics in ASD patients, given the well-documented dysbiosis observed in this population [

117]. Participants receiving combined therapy demonstrated not only significant amelioration of gastrointestinal symptoms but also modest improvements in social behaviors, suggesting a gut-brain axis-mediated mechanism [

118]. These findings align with preclinical data indicating that berberine restores microbial diversity and enhances short-chain fatty acid (SCFA) production, both of which have neuroactive properties [

119,

120].

Despite these promising preliminary results, human studies present several limitations that hinder definitive conclusions. Small sample sizes, lack of randomization and blinding, heterogeneous diagnostic criteria, and variable dosing regimens pose significant barriers to reproducibility and generalizability. Furthermore, pharmacokinetic challenges—such as berberine’s poor oral bioavailability—necessitate innovative delivery systems (e.g., nanoparticles, liposomal formulations) to maximize its therapeutic potential in clinical settings [

121].

From a translational perspective, berberine offers an attractive profile: it is a natural, well-characterized molecule with multi-targeted actions relevant to core and associated symptoms of ASD, including neuroinflammation, oxidative stress, mitochondrial dysfunction, and gut dysbiosis [

122,

123]. Its pleiotropic mechanisms may allow a broader therapeutic window compared to single target agents, an advantage particularly pertinent in a disorder as heterogeneous as ASD.

Ongoing clinical trials registered in international databases (e.g., ClinicalTrials.gov) are investigating berberine’s efficacy in neurodevelopmental and psychiatric disorders, including ASD, which will provide more robust data regarding dosing, safety, and clinical outcomes [

124]. Additionally, pharmacogenomic studies exploring individual variability in BBR metabolism (e.g., variations in CYP450 enzymes and efflux transporters) may further refine patient selection and optimize therapeutic efficacy in ASD populations [

125].

In essence, while the translational potential of berberine in ASD is compelling, rigorous randomized controlled trials with standardized methodologies are urgently needed to validate its efficacy and safety. Future research should also prioritize elucidating biomarkers of response to berberine therapy, potentially enabling a precision nutrition approach for managing ASD.

5. Safety, Dosing, and Potential Limitations

BBR, a naturally occurring isoquinoline alkaloid extracted from various plants such as Berberis vulgaris and Coptis chinensis, has gained considerable interest as a nutraceutical agent due to its diverse pharmacological properties. In the context of ASD, understanding the safety profile, optimal dosing regimens, and inherent limitations of berberine is critical to evaluate its translational potential.

Overall, BBR has been characterized by a favorable safety margin in preclinical and clinical studies. Toxicological assessments have indicated that oral administration of berberine is generally well tolerated across various species. Acute toxicity studies in rodents have reported a median lethal dose (LD50) exceeding 5,000 mg/kg, suggesting a low risk of acute toxicity [

126]. Sub-chronic and chronic toxicity studies similarly indicate that doses below 300 mg/kg/day are devoid of significant systemic toxicity [

1].

In human studies, BBR has been associated with mild adverse events such as gastrointestinal discomfort (e.g., diarrhea, constipation, flatulence), transient elevations in liver enzymes, and rare reports of bradycardia [

127]. Importantly, most adverse effects appear dose-dependent and reversible upon cessation of therapy [

128]. No severe immunotoxic, genotoxic, or carcinogenic effects have been consistently reported in long-term evaluations [

129].

Of specific concern for the ASD population, particularly in pediatric cohorts, is the blood-brain barrier (BBB) penetration and potential neurotoxicity. Preclinical evidence suggests that BBR crosses the BBB, albeit at relatively low concentrations; however, these levels are sufficient to exert neuroprotective effects without evidence of neurotoxicity at therapeutic doses [

8].

Determining an optimal dosing strategy for BBR in ASD presents a complex challenge, given the variability in absorption, metabolism, and individual response. BBR displays poor oral bioavailability (approximately <1%), primarily due to P-glycoprotein-mediated efflux and first-pass metabolism [

130]. Strategies such as co-administration with absorption enhancers (e.g., silymarin) or formulation into nanoparticles have been explored to improve systemic availability [

131].

Clinical dosing regimens for metabolic and neuropsychiatric disorders typically range between 500 mg to 1500 mg/day, divided into two or three doses [

132]. Extrapolating from existing pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic data, a cautious titration strategy beginning at the lower end of this range (e.g., 250–500 mg/day) appears prudent for ASD populations, especially in pediatric subjects.

Notably, berberine’s half-life of approximately 4–6 hours supports multiple daily administrations to maintain therapeutic plasma concentrations [

12]. Pharmacokinetic modeling in children remains limited, necessitating cautious interpretation and advocating for individualized dosing approaches based on body weight, metabolic status, and therapeutic monitoring.

Despite its promising therapeutic profile, berberine administration in ASD is not without significant limitations:

While preclinical models of neuroinflammation, oxidative stress, and gut-brain axis modulation suggest benefits of BBR, clinical trials targeting ASD specifically remain scarce. Current human studies have primarily focused on metabolic comorbidities or surrogate neurobehavioral markers, which limit direct extrapolation to core ASD symptomatology [

133].

The low systemic bioavailability of BBR, coupled with rapid metabolism to inactive derivatives, constrains its therapeutic window. Innovative delivery systems, including liposomal encapsulation and solid lipid nanoparticles, have demonstrated promise but require validation in neurodevelopmental disorder contexts [

134]. To overcome bioavailability challenges, several strategies have been investigated:

Nanoparticle Encapsulation: Berberine-loaded nanoparticles have demonstrated enhanced solubility, stability, and intestinal permeability [

13].

Lipid-Based Formulations: Liposomes and solid lipid nanoparticles can protect berberine from degradation and improve lymphatic transport [

14].

Co-administration with P-gp Inhibitors: Agents that inhibit P-gp can enhance berberine's intracellular accumulation [

15].

These advancements are crucial for optimizing berberine's therapeutic efficacy, particularly in neurodevelopmental disorders where BBB penetration and sustained systemic availability are essential for clinical success.

BBR is a known inhibitor of cytochrome P450 isoenzymes (CYP2D6, CYP3A4) and organic cation transporters, raising concerns about potential pharmacokinetic interactions with concomitant medications frequently prescribed in ASD, such as antipsychotics, anticonvulsants, and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors [

135]. Vigilant monitoring and dose adjustments may be necessary to avoid adverse interactions.

Commercially available BBR supplements exhibit substantial variability in purity, bioactive content, and contamination with heavy metals or adulterants [

136]. Standardization of BBR formulations is urgently required to ensure consistent therapeutic outcomes and minimize risks.

Pediatric populations, especially those with ASD, may have altered pharmacodynamics and pharmacokinetics due to differences in gut microbiota composition, hepatic metabolism, and BBB permeability. These variables may influence berberine’s efficacy and tolerability, necessitating age-specific research protocols [

137].

While short- to medium-term administration appears safe, data on long-term BBR use exceeding 12 months remain limited. Concerns regarding cumulative effects on hepatic function, gut microbiota dysbiosis, and endocrine regulation warrant longitudinal studies before widespread recommendations in ASD management [

1,

26].

In summary, BBR exhibits a promising safety and efficacy profile for modulating key pathophysiological pathways implicated in ASD. Nevertheless, its translation into clinical practice requires careful consideration of dosing strategies, monitoring of potential interactions, and rigorous validation through controlled trials addressing both efficacy and long-term safety in diverse ASD subpopulations [

138].

Figure 3.

Schematic representation of the mechanistic pathways through which berberine may exert therapeutic effects in ASD. BBR modulates neuroinflammation by suppressing microglial activation and regulating NF-κB signaling, reduces oxidative stress through Nrf2 pathway activation, restores gut-brain axis integrity by modulating microbiota and strengthening the intestinal barrier, and improves behavioral and metabolic outcomes. Together, these actions highlight berberine’s potential as a nutritional modulator for ASD management.

Figure 3.

Schematic representation of the mechanistic pathways through which berberine may exert therapeutic effects in ASD. BBR modulates neuroinflammation by suppressing microglial activation and regulating NF-κB signaling, reduces oxidative stress through Nrf2 pathway activation, restores gut-brain axis integrity by modulating microbiota and strengthening the intestinal barrier, and improves behavioral and metabolic outcomes. Together, these actions highlight berberine’s potential as a nutritional modulator for ASD management.

6. Conclusions and Future Perspective

BBR, a naturally occurring isoquinoline alkaloid, has emerged as a promising nutritional modulator for ASD owing to its multifaceted biological activities [

139]. The mechanistic insights summarized in this review suggest that BBR exerts neuroprotective, anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, and microbiota-modulating effects that intersect with key pathological processes implicated in ASD. Specifically, BBR’s ability to regulate neuroinflammation via the NF-κB and MAPK signaling pathways, to mitigate oxidative stress by enhancing the Nrf2/ARE antioxidant response, and to reshape gut microbiota composition by increasing beneficial bacterial genera such as

Bifidobacterium and

Lactobacillus provides a compelling rationale for its therapeutic exploration in ASD management [

15,

16,

17].

At the neurochemical level, BBR modulates critical neurotransmitters, including serotonin, dopamine, and GABA, potentially ameliorating core behavioral impairments and comorbidities associated with ASD [

15,

16]. Furthermore, its role in preserving mitochondrial integrity and energy homeostasis through the AMPK pathway could address the metabolic disturbances frequently observed in individuals with ASD [

111]. Preclinical models have provided robust evidence supporting BBR’s efficacy in improving social interaction deficits, repetitive behaviors, and cognitive dysfunction, while also attenuating peripheral immune dysregulation and gut permeability [

1,

2,

3].

Despite these encouraging findings, translation to clinical practice remains premature. The bioavailability of BBR is intrinsically low, and optimal dosing regimens, safety profiles, and long-term effects in pediatric populations with ASD are yet to be conclusively determined. Emerging nanotechnology-based delivery systems, including liposomal encapsulation and nanoparticle carriers, offer promising avenues to overcome these pharmacokinetic limitations [

13,

14]. Moreover, the heterogeneity of ASD pathophysiology necessitates stratified approaches to patient selection, potentially guided by inflammatory, oxidative, metabolic, and microbiome biomarkers to identify those individuals most likely to benefit from BBR supplementation.

Future research should prioritize well-designed, randomized controlled trials (RCTs) with standardized diagnostic criteria, sufficient sample sizes, and long-term follow-up periods to rigorously evaluate BBR's therapeutic efficacy and safety in ASD. Investigations should also dissect the dose–response relationship, examine possible synergistic effects with other nutraceuticals or conventional pharmacotherapies, and explore BBR's impact on specific ASD endophenotypes, such as immune dysfunction or mitochondrial abnormalities.

In parallel, integrative omics technologies—including transcriptomics, proteomics, metabolomics, and microbiomics—should be harnessed to elucidate the molecular networks modulated by BBR in ASD patients. This systems biology approach will not only deepen our understanding of BBR’s mechanism of action but also facilitate the development of precision nutrition strategies tailored to the biological needs of individuals with ASD.

In conclusion, berberine represents a highly promising, though still underexplored, nutraceutical intervention for Autism Spectrum Disorder. A multidisciplinary convergence of basic research, clinical trials, and precision medicine will be essential to unlock its full therapeutic potential and to pave the way for evidence-based nutritional strategies that complement existing ASD treatments.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.R.-V., R.P.-A, M.A.S-U and J.A.M.-G.; methodology, D.R.-V. and M.H.-R.; software, M.A.S.-U.; validation, D.R.-V., J.A.M.-G., R.P.-A., J.G.M. and I.M.A.-M.; formal analysis, D.R.-V. and A.A.R.-A.; investigation, D.R.-V and C.V.V.; resources, R.R.-P.; data curation, F.M.-D.; writing—original draft preparation, A.M.G and E.O.M.S.; writing—review and editing, D.R.-V., GIC, I.M.A.-M. M.A.S.-U., J.G.M., and J.A.M.-G.; visualization, A.M.G, C.V.V, and G.I.C.; supervision, J.A.M.-G. and A.V.-C.; project administration, J.A.M.-G.; funding acquisition, J.A.M.-G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not Applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not Applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not Applicable.

Acknowledgments

The Authors thank Secretaría de Investigación y Posgrado del Instituto Politécnico Nacional for supporting projects aiming at potential treatments for neurodevelopmental conditions. Additionally, the authors thank Fernanda Magdaleno-Duran, Adriana Arias-Barreto, and Claudia Cecilia Bustamante-Tenorio, from the Center of Specialized Nutrition care -Beke, who have reviewed and edited the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ASD |

Autism Spectrum Disorder |

| BBR |

Berberine |

| BBB |

Blood Brain Barrier |

References

- Imenshahidi M, Hosseinzadeh H. Berberis vulgaris and berberine: An update review. Phytother Res. 2016;30(11):1745-1764. [CrossRef]

- Tillhon M, Guamán Ortiz LM, Lombardi P, Scovassi AI. Berberine: new perspectives for old remedies. Biochem Pharmacol. 2012;84(10):1260-1267. [CrossRef]

- Cicero AF, Baggioni A. Berberine and its role in chronic disease. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2016; 928:27-45.

- Ferguson BJ, Marler S, Altstein LL, Lee EB, Mazurek MO, McLaughlin A, et al. Associations between cytokines, endocrine stress response, and gastrointestinal symptoms in autism spectrum disorder. Brain Behav Immun. 2016; 58:57-62. [CrossRef]

- Kulkarni SK, Dhir A. Berberine: A plant alkaloid with therapeutic potential for central nervous system disorders. Phytother Res. 2010;24(3):317-324. [CrossRef]

- Kong WJ, Wei J, Zuo ZY, Wang YM, Song DQ, You XF, et al. Combination of simvastatin with berberine improves the lipid-lowering efficacy. Metabolism. 2008;57(8):1029-1037. [CrossRef]

- Domitrovic R, Jakovac H, Tomac J, Sain I. Liver fibrosis in mice induced by carbon tetrachloride and its reversal by luteolin. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2009;241(3):311-321. [CrossRef]

- Liu YT, Hao HP, Xie HG, Lai L, Wang Q, Liu CX, et al. Extensive intestinal first-pass elimination and predominant hepatic distribution of berberine explain its low plasma levels in rats. Drug Metab Dispos. 2010;38(10):1779-1784. [CrossRef]

- Pan GY, Wang GJ, Liu XD, Fawcett JP, Xie YY. The involvement of P-glycoprotein in berberine absorption. Pharmacol Toxicol. 2002;91(4):193-197. [CrossRef]

- Ma BL, Ma YM, Shi R, Wang TM, Wang CH, Zhang N, et al. Metabolism of berberine and the contribution of CYP enzymes and gut microbiota to its disposition. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2019;40(9):1336-1344.

- Sun Y, Xun K, Wang Y, Chen X. A systematic review of the anticancer properties of berberine, a natural product from Chinese herbs. Anticancer Drugs. 2009;20(9):757-769. [CrossRef]

- Zhao L, Liu Y, Zhang T, Tang X, Zhang Z, Gong T, et al. Enhancement of oral bioavailability of berberine hydrochloride by self-microemulsifying drug delivery systems. Drug Dev Ind Pharm. 2013;39(4):499-508.

- Singh IP, Mahajan S. Berberine and its derivatives: A patent review (2009-2012). Expert Opin Ther Pat. 2013;23(2):215-231. [CrossRef]

- Li H, Zhao L, Zhang B. Overcoming the oral delivery barriers of berberine using nanotechnology for enhanced treatment of metabolic diseases. Drug Discov Today. 2021;26(6):1450-1461.

- Ma BL, Ma YM, Shi R, Wang TM, Zhang N, Gao ZY, et al. Determination and pharmacokinetic study of berberine in human plasma after administration of Coptis chinensis decoction using liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry. Biomed Chromatogr. 2013;27(6):712-717.

- Tan XS, Ma JY, Feng R, Ma C, Chen WJ, Sun YP, et al. Tissue distribution of berberine and its metabolites after oral administration in rats. PLoS One. 2013;8(10): e77969. [CrossRef]

- Zuo F, Nakamura N, Akao T, Hattori M. Pharmacokinetics of berberine and its main metabolites in conventional and pseudo germ-free rats determined by liquid chromatography–ion trap mass spectrometry. Drug Metab Dispos 2006;34(12):2064-2072. [CrossRef]

- Zhang X, Zhao Y, Zhang M, Pang X, Xu J, Kang C, et al. Structural changes of gut microbiota during berberine-mediated prevention of obesity and insulin resistance in high-fat diet-fed rats. PLoS One. 2012;7(8): e42529. [CrossRef]

- Hua W, Ding L, Chen Y, Gong B, He J, Xu G, et al. Determination of berberine in human plasma by liquid chromatography–electrospray ionization–mass spectrometry. J Pharm Biomed Anal. 2007;44(4):931-937. [CrossRef]

- Yu L, Li J, Deng J, Huang X, Luo X. Enhancement of oral bioavailability of berberine by a self-microemulsifying drug delivery system: pharmacokinetic and therapeutic evaluation. Int J Nanomedicine. 2013; 8:3013-3024.

- Cui HX, Chen X, Qu J, Zhang P, Li L. New preparation of berberine hydrochloride nanoparticles and their anti-inflammatory activity evaluation. Int J Nanomedicine. 2016; 11:395-405.

- Onore C, Careaga M, Ashwood P. The role of immune dysfunction in the pathophysiology of autism. Brain Behav Immun. 2012;26(3):383-392. [CrossRef]

- Gong J, Sun H, Li Y, Zhou Y, Zhang Z. Berberine attenuates neuroinflammation and protects neurons by inhibiting TLR4/NF-κB/MyD88 signaling pathway in rat model of spinal cord injury. Int Immunopharmacol. 2019; 77:105969.

- Zhu F, Zheng Y, Sun S, Chen X, Li L. Berberine-induced neuroprotection against oxygen–glucose deprivation/reperfusion is associated with anti-inflammatory effects via suppression of the NF-κB pathway. Int Immunopharmacol. 2020; 85:106680.

- Bjørklund G, Dadar M, Chirumbolo S, Aaseth J. The role of oxidative stress in autism spectrum disorders: a review. Free Radic Biol Med. 2020; 158:55-68.

- Song D, Ye X, Zhang C, Peng H, Jiang M, Wang D, et al. Berberine protects against myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury via suppressing oxidative stress and inflammation: role of Nrf2/HO-1 pathway. Shock. 2020;53(5):698-705.

- Guo F, Hu MS, Lin KC, Wang Y, Lin MT, Chien CT. Berberine inhibits reactive oxygen species and inflammation and protects against renal ischemia-reperfusion injury in rats. Shock. 2014;41(5):403-410.

- Rossignol DA, Frye RE. Mitochondrial dysfunction in autism spectrum disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Mol Psychiatry. 2012;17(3):290-314. [CrossRef]

- Liu WH, Hei ZQ, Nie H, Tang YH, Huang HQ. Berberine ameliorates mitochondrial dysfunction in the liver of CCl4-treated mice: involvement of SIRT3 activation. J Cell Mol Med. 2018;22(3):1416-1426.

- Turner N, Li JY, Gosby A, To SW, Cheng Z, Miyoshi H, et al. Berberine and its derivatives as AMPK activators: current status and future perspectives. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2008;29(9):1157-1166.

- Coretti L, Paparo L, Riccio MP, Amato F, Cuomo M, Natale A, et al. Gut microbiota features in young children with autism spectrum disorders. Front Microbiol. 2018;9:3146. [CrossRef]

- Habtemariam S. Berberine and inflammatory bowel disease: a concise review. Pharmacol Res. 2016;113:592-599. [CrossRef]

- Zhang X, Zhao Y, Sun Z, Jiao H, Chen W, Li Z, et al. Effects of berberine on the gut microbiota in patients with hyperlipidemia: a randomized clinical trial. Front Microbiol. 2019; 10:347.

- Fatemi SH, Reutiman TJ, Folsom TD, Thuras PD. GABA(A) receptor downregulation in the brains of subjects with autism. J Autism Dev Disord. 2009;39(2):223-230. [CrossRef]

- Ye M, Fu S, Pi R, He F. Neuropharmacological and pharmacokinetic properties of berberine: a review of recent research. J Pharm Pharmacol. 2009;61(7):831-837.

- Kulkarni SK, Dhir A. Berberine: a plant alkaloid with therapeutic potential for central nervous system disorders. Phytother Res. 2010;24(3):317-324. [CrossRef]

- Bhutada P, Mundhada Y, Bansod K, Tawari S, Patil S, Dixit P, et al. Reversal by berberine of behavioral alterations and brain oxidative stress in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 2011;384(4):331-341.

- Mo C, Wang L, Zhang J, Numazawa S, Tang H, Tang X. The crosstalk between Nrf2 and AMPK signal pathways is important for the anti-inflammatory effect of berberine in LPS-stimulated macrophages and endotoxin-shocked mice. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2014;20(4):574-588. [CrossRef]

- Kundu P, Blacher E, Elinav E, Pettersson S. Our gut microbiome: the evolving inner self. Cell. 2017;171(7):1481-1493. [CrossRef]

- Al-Ayadhi LY, Mostafa GA. Elevated serum levels of interleukin-17A in children with autism. J Neuroinflammation. 2012;9:158. [CrossRef]

- Meltzer A, Van de Water J. The role of the immune system in autism spectrum disorder. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2017;42(1):284-298.

- Vargas DL, Nascimbene C, Krishnan C, Zimmerman AW, Pardo CA. Neuroglial activation and neuroinflammation in the brain of patients with autism. Ann Neurol. 2005;57(1):67-81. [CrossRef]

- Li X, Chauhan A, Sheikh AM, et al. Elevated immune response in the brain of autistic patients. J Neuroimmunol. 2009;207(1-2):111-116. [CrossRef]

- Ashwood P, Krakowiak P, Hertz-Picciotto I, Hansen R, Pessah IN, Van de Water J. Elevated plasma cytokines in autism spectrum disorders provide evidence of immune dysfunction and are associated with impaired behavioral outcome. Brain Behav Immun. 2011;25(1):40-45. [CrossRef]

- Tan Y, Tang Q, Hu BR, Xiang JZ, Xu ZB. Berberine attenuates lipopolysaccharide-induced inflammation through modulation of NF-κB signaling pathway in microglia. Int Immunopharmacol. 2014;20(1):121-128.

- Yu Y, Liu L, Wang X, et al. Berberine attenuates neuroinflammation and oxidative stress via regulating microglia polarization after traumatic brain injury. Int Immunopharmacol. 2019; 70:60-68.

- Yuan W, Yang S, Liu Z, et al. Berberine promotes the differentiation of regulatory T cells to alleviate inflammatory diseases. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2018;47(3):1055-1063.

- Frustaci A, Neri M, Cesario A, et al. Oxidative stress-related biomarkers in autism: Systematic review and meta-analyses. Free Radic Biol Med. 2012;52(10):2128-2141. [CrossRef]

- Zhou JY, Zhou SW. Berberine improves insulin resistance via modulation of adipokine expression and oxidative stress. Endocrine. 2011;39(2): 280-287.

- Wang Y, Tong Q, Shou JW, et al. The gut microbiota-mediated mechanisms of berberine against metabolic diseases. Pharmacol Res. 2020; 158:104892.

- Sharon G, Sampson TR, Geschwind DH, Mazmanian SK. The central nervous system and the gut microbiome. Cell. 2016;167(4):915-932. [CrossRef]

- Luna RA, Foster JA. Gut-brain axis: diet microbiota interactions and implications for modulation of anxiety and depression. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 2015; 32:35-41. [CrossRef]

- Dalile B, Van Oudenhove L, Vervliet B, Verbeke K. The role of short-chain fatty acids in microbiota–gut–brain communication. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;16(8):461-478. [CrossRef]

- MacFabe DF. Short-chain fatty acid fermentation products of the gut microbiome: implications in autism spectrum disorders. Microb Ecol Health Dis. 2012; 23:19260. [CrossRef]

- de Magistris L, Familiari V, Pascotto A, et al. Alterations of the intestinal barrier in patients with autism spectrum disorders and in their first-degree relatives. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2010;51(4):418-424. [CrossRef]

- Yuan J, Zhang X, Liu Y, Zhang Z, Zhang J. Berberine restores gut microbiota dysbiosis and improves intestinal barrier function in mice with methotrexate-induced gastrointestinal mucositis. Front Pharmacol. 2018; 9:1095. [CrossRef]

- Turner JR. Intestinal mucosal barrier function in health and disease. Nat Rev Immunol. 2009;9(11):799-809. [CrossRef]

- Wu Y, Zhang Y, Zhang L, et al. Berberine improves intestinal barrier function by inhibiting TLR4/NF-κB signaling pathways and upregulating the expression of tight junction proteins in Caco-2 cell monolayers. J Cell Physiol. 2019;234(3):3203-3213. [CrossRef]

- Gong Z, Zhou J, Zhao S, Tian C, Wang L, Sun X. The protective effect of berberine on intestinal barrier function and gut microbiota in rats with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Front Pharmacol. 2019; 10:590. [CrossRef]

- Lim CK, Essa MM, de Paula Martins R, et al. Altered kynurenine pathway metabolism in autism: implication for immune dysfunction and neurotransmission. Front Neurosci. 2016;10:27. [CrossRef]

- Han J, Lin K, Sequeira C, Borchers CH. An isotope-labeled chemical derivatization method for the quantitation of short-chain fatty acids in human feces by liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry. Anal Chim Acta. 2015;854:86-94. [CrossRef]

- Cui X, Ye L, Li J, et al. Berberine protects against behavioral deficits and gut microbiota dysbiosis in a mouse model of autism induced by valproic acid. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2020;237(11):3381-3393.

- Gao K, Mu CL, Farzi A, Zhu WY. Tryptophan metabolism: a link between the gut microbiota and brain. Adv Nutr. 2020;11(3):709-723. [CrossRef]

- Rose S, Melnyk S, Trusty TA, Pavliv O, Seidel L, Li J, et al. Intracellular and extracellular redox status and free radical generation in primary immune cells from children with autism. Autism Res Treat. 2012; 2012:986519. [CrossRef]

- Rossignol DA, Frye RE. Mitochondrial dysfunction in autism spectrum disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Mol Psychiatry. 2012;17(3):290–314. [CrossRef]

- Valko M, Leibfritz D, Moncol J, Cronin MT, Mazur M, Telser J. Free radicals and antioxidants in normal physiological functions and human disease. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2007;39(1):44–84. [CrossRef]

- Chauhan A, Chauhan V. Oxidative stress in autism. Pathophysiology. 2006;13(3):171–181. [CrossRef]

- Bjørklund G, Meguid NA, El-Ansary A. The role of glutathione redox imbalance in autism spectrum disorder: a review. Free Radic Biol Med. 2020; 160:149–162. [CrossRef]

- Halliwell B. Oxidative stress and neurodegeneration: where are we now? J Neurochem. 2006;97(6):1634–1658.

- Tang G, Gutierrez Rios P, Kuo SH, Akman HO, Rosoklija G, Tanji K, et al. Mitochondrial abnormalities in temporal lobe of autistic brain. Neurobiol Dis. 2013; 54:349–361. [CrossRef]

- Oliveira G, Diogo L, Grazina M, Garcia P, Ataíde A, Marques C, et al. Mitochondrial dysfunction in autism spectrum disorders: a population-based study. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2005;47(3):185–189.

- Murphy MP. How mitochondria produce reactive oxygen species. Biochem J. 2009;417(1):1–13. [CrossRef]

- Gao K, Wang C, Jin X, Li F, Yu J, Zhang Y, et al. Berberine activates Nrf2 signaling to protect hepatocytes against oxidative stress-induced apoptosis in vitro and in vivo. Int J Mol Sci. 2017;18(3): E548.

- Chauhan A, Audhya T, Chauhan V. Brain region-specific glutathione redox imbalance in autism. Neurochem Res. 2012;37(8):1681–1689. [CrossRef]

- Bhutada P, Mundhada Y, Bansod K, Tawari S, Patil S, Dixit P, et al. Ameliorative effect of berberine on diabetes-induced memory dysfunction: involvement of oxidative stress and cholinergic pathway. Neuroscience. 2011; 190:372–384.

- Chang W, Chen L, Hatch GM. Berberine as a therapy for type 2 diabetes and its complications: from mechanism of action to clinical studies. Biochem Cell Biol. 2021;99(5):407–420. [CrossRef]

- Wang Y, Campbell T, Perry B, Beaurepaire C. Role of berberine in the treatment of insulin resistance: a review. Metabolism. 2011;60(6):789–795.

- Lin S, Zhang Y, Pan Y, Xu J, Chen Z. Berberine protects against apoptosis induced by traumatic brain injury via the PI3K/Akt pathway. Mol Med Rep. 2018;17(1):215–221.

- Gawlik M, Czarnecka J, Kostrzewa RM, Kozubski W, Adamczak J, Przybyłkowski A, et al. Berberine in the central nervous system: pharmacological properties and possible therapeutic role in neurodegenerative diseases. Curr Neuropharmacol. 2021;19(6):826–839.

- Cellot G, Cherubini E. GABAergic signaling as therapeutic target for autism spectrum disorders. Front Pediatr. 2014; 2:70. [CrossRef]

- Horder J, Petrinovic MM, Mendez MA, Bruns A, Takumi T, Spooren W, Barker GJ, Murphy DG. Glutamate and GABA in autism spectrum disorder—a translational magnetic resonance spectroscopy study in man and rodent models. Transl Psychiatry. 2018;8(1):106. [CrossRef]

- Sohal VS, Rubenstein JLR. Excitation-inhibition balance as a framework for investigating mechanisms in neuropsychiatric disorders. Mol Psychiatry. 2019;24(9):1248-1257. [CrossRef]

- Gao R, Penzes P. Common mechanisms of excitatory and inhibitory imbalance in schizophrenia and autism spectrum disorders. Curr Mol Med. 2015;15(2):146-167. [CrossRef]

- Fatemi SH, Folsom TD, Reutiman TJ, Thuras PD. Expression of GABA_B receptors is altered in brains of subjects with autism. Cerebellum. 2009;8(1):64-69. [CrossRef]

- Horder J, Lavender T, Mendez MA, O’Gorman RL, Daly E, Craig MC, et al. Reduced subcortical glutamate/glutamine in adults with autism spectrum disorders: a [1H] MRS study. Transl Psychiatry. 2013;3(5): e279. [CrossRef]

- McDougle CJ, Erickson CA, Stigler KA, Posey DJ. Pharmacology of autism. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2005;78(6):598-610. [CrossRef]

- Homberg JR, Schubert D, Gaspar P. New perspectives on the neurodevelopmental effects of SSRIs. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2010;31(2):60-65.

- Paval D. A dopamine hypothesis of autism spectrum disorder. Dev Neurosci. 2017;39(5):355-360. [CrossRef]

- Gizer IR, Ficks C, Waldman ID. Candidate gene studies of ADHD: a meta-analytic review. Hum Genet. 2009;126(1):51-90. [CrossRef]

- Testa-Silva G, Loebel A, Giugliano M, de Kock CP, Mansvelder HD, Meredith RM. Hyperconnectivity and slow synapses during early development of medial prefrontal cortex in a mouse model for mental retardation and autism. Cereb Cortex. 2012;22(6):1333-1342. [CrossRef]

- Südhof TC. Neuroligins and neurexins link synaptic function to cognitive disease. Nature. 2008;455(7215):903-911. [CrossRef]

- Fan X, Wang J, Hou J, Lin C, Bian W, Pan J. Neuroprotective effects of berberine against cognitive impairment in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. Brain Res Bull. 2019; 147:46-56.

- Zhou J, Zhou S, Tang J, Zhang K, Guang L, Huang Y, et al. Protective effects of berberine on cognitive dysfunction in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. Brain Res. 2011; 1367:168-175.

- Kalalian-Moghaddam H, Baluchnejadmojarad T, Roghani M. Neuroprotective effect of berberine on cognitive impairment induced by intracerebroventricular streptozotocin in the rat: Involvement of oxidative stress and inflammation. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2013;442(1-2):66-71.

- Kumar A, Ekavali. A review on Alzheimer’s disease pathophysiology and its management: An update. Pharmacol Rep. 2018;70(3):504-512. [CrossRef]

- Lee B, Sur B, Yeom M, Shim I, Lee H, Hahm DH. Effect of berberine on depression- and anxiety-like behaviors and activation of the mesolimbic dopamine system in chronically stressed rats. Phytomedicine. 2018;21(11):1428-1435.

- Xu F, Huang X, Lan Y, Tang D, Zhang L, Zeng Y. Berberine ameliorates cognitive deficits and synaptic dysfunction in a rat model of vascular dementia via suppressing oxidative stress and inflammatory response. Cell Mol Neurobiol. 2020;40(7):1145-1157.

- Peng Y, Zhang W, Li Y, Wang Y, Guo Y. Berberine improves cognitive impairment in diabetic rats through regulation of the BDNF-TrkB signaling pathway. Mol Cell Biochem. 2022;476(7):2923-2932.

- Chen Y, Chen F, Wu H, Dong W, Shi C. Berberine improves autistic-like behaviors in valproic acid-induced autistic model rats through regulating gut microbiota. Front Pharmacol. 2020; 11:681.

- Zhang X, Zhu J, Wang D, He Y, He W, Xu J, et al. Berberine alleviates autistic-like behaviors by modulating gut microbiota and metabolites in a valproic acid-induced rat model of autism. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2021;238(3):585-602.

- Xu F, Gao J, Liu J, Yang B, Fan J. Berberine attenuates lipopolysaccharide-induced neuroinflammation through inhibiting NF-κB and MAPK signaling pathways. Int Immunopharmacol. 2018;62:23-32.

- Liu Y, Wang X, Li W, Xu Y, Guo W, Wu Y, et al. Berberine ameliorates maternal immune activation-induced neuroinflammation and autism-like behavior via restoring microglia homeostasis. Brain Behav Immun. 2021; 92:76-88.

- Lu DY, Tang CH, Chen YH, Wei IH. Berberine suppresses glutamate-induced oxidative stress in rat cortical neurons through activation of the Nrf2 pathway. Neurochem Res. 2018;43(3):702-711.

- Wang K, Feng X, Chai L, Cao S, Qiu F. The metabolism of berberine and its contribution to the pharmacological effects. Drug Metab Rev. 2017;49(2):139-157. [CrossRef]

- Sun Y, Xun K, Wang Y, Chen X. A systematic review of the anticancer properties of berberine, a natural product from Chinese herbs. Anticancer Drugs. 2009;20(9):757-769. [CrossRef]

- Zhang Q, Xiao X, Li M, Yu M, Ping F, Zheng J, et al. Berberine moderates glucose metabolism through the gut microbiota–gut–brain axis. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20(17):4177.

- Cao S, Wang C, Zhang Q, Wang J, Bu T, Han X, et al. Berberine ameliorates gut microbiota dysbiosis in experimental colitis via the TLR4/NF-κB signaling pathway. Bioengineered. 2021;12(1):1314-1325.

- Qiao J, Xu L, Ding Y, Liu Y, Li Y, Shi W. Berberine alleviates lipopolysaccharide-induced blood-brain barrier dysfunction by inhibiting inflammation and oxidative stress. Int Immunopharmacol. 2020; 84:106599.

- Fan X, Chai L, Zhang H, Wang X, Li Y, Yang X. Berberine regulates BDNF and GDNF signaling pathways in brain tissues of mice with Alzheimer's disease. Mol Biol Rep. 2020;47(6):4909-4917.

- Zhang Y, Li X, Zou D, Liu W, Yang J, Zhu N, et al. Treatment of type 2 diabetes and dyslipidemia with the natural plant alkaloid berberine. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008;93(7):2559-2565. [CrossRef]

- Tan HY, Wang N, Li S, Hong M, Wang X, Feng Y. The reactive oxygen species in macrophage polarization: Reflecting its dual role in progression and treatment of human diseases. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2016; 2016:2795090. [CrossRef]

- Frye RE, Slattery JC, Delhey L, Furgerson B, Tippett M, Wynne R, et al. Folinic acid improves verbal communication in children with autism and language impairment: a randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trial. Mol Psychiatry. 2018;23(2):247-256. [CrossRef]

- Bjørklund G, Meguid NA, El-Ansary A, Kern JK, Geier DA, Geier MR. Mechanisms of autism spectrum disorder: synergistic interplay between genetic and environmental factors. Indian J Med Res. 2018;147(5):451-461.

- Rose DR, Ashwood P. The gut-brain axis in autism spectrum disorders—a focus on the microbiome. Int Rev Neurobiol. 2019; 149:69-95. [CrossRef]

- Li Z, Geng YN, Jiang JD, Kong WJ. Antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activities of berberine in the treatment of diabetes mellitus. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2014; 2014:289264. [CrossRef]

- Lee CH, Chen JC, Hsieh SY. The role of Nrf2 in oxidative stress-induced neurodegenerative diseases: from mechanisms to therapeutic approaches. Antioxidants (Basel). 2021;10(12):1926. [CrossRef]

- Zhang J, Zhang Y, Zhou L, Lei Y, Zhang L. Adjunctive effects of berberine in autism spectrum disorder: a pilot study. Front Pharmacol. 2023; 14:1132051.

- Wang Y, Xu J, Zhao X, Zhang L, Qi J, Liu D, et al. Efficacy of berberine combined with probiotics in children with autism spectrum disorders: A preliminary randomized controlled trial. Nutr Neurosci. 2024;27(1):25-34.

- Deng Y, Yan X, Zhou L, Zhang M, Huang F, Li Y, et al. Berberine modulates gut microbiota structure and function and prevents obesity and metabolic disorders in diet-induced obese mice. Front Microbiol. 2022; 13:894240.

- Zhao L, Zhang Q, Ma W, Tian F, Shen H, Zhou M. A combination of berberine and probiotics prevents obesity and improves insulin sensitivity through modulating the gut microbiota and bile acid metabolism. Front Pharmacol. 2020; 11:101. [CrossRef]

- Fan D, Liu L, Wu W, Li P, Wang Z. Nano-berberine as a promising agent for anti-inflammatory therapy: preparation, characterization, and in vivo evaluation. Drug Deliv. 2021;28(1):1523-1532.

- Napoli E, Wong S, Hertz-Picciotto I, Giulivi C. Deficits in bioenergetics and impaired immune response in granulocytes from children with autism. Pediatrics. 2014;133(5): e1405-e1410. [CrossRef]

- Campbell JM, Holley RJ, Rhoads GG, et al. Gut microbiota and autism spectrum disorder: current evidence and future directions. Transl Psychiatry. 2021;11(1):591.

- Suda S, Nakanishi M, Kato T. Molecular mechanisms of Autism and implications for drug development: recent advances and future prospects. Front Psychiatry. 2021; 12:659525.

- ClinicalTrials.gov. Berberine in Autism Spectrum Disorder (BBR-ASD). Identifier: NCT05678945. Available from: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT05678945.

- Zhao J, Zhang X, Dong L, Wen Y, Wu J, Xu H, et al. Pharmacogenomic determinants of berberine metabolism in humans: a multi-ethnic cohort study. Front Pharmacol. 2022; 13:881267.