1. Introduction

Peripheral arterial occlusive disease (PAOD) is a condition characterized by atherosclerosis in the peripheral blood vessels. The risk factors include hypertension, diabetes, dyslipidemia, advanced age, and smoking [

1]. The prevalence of PAOD ranges from 3% to 10% and rises with advancing age [

1]. Most cases of PAOD may progress to coronary artery disease (CAD) [

1,

2], lead to cardiovascular death.

The majority of PAOD cases are asymptomatic, while symptomatic PAOD can be categorized into intermittent claudication, ischemic pain at rest, and small or large area necrosis [

3]. Symptomatic PAOD is caused by acute thrombotic obstruction of blood flow in the lower limbs, leading to pain or tissue necrosis, with a mechanism similar to that of CAD. Tissue necrosis and infection in the lower limbs require amputation to avoid death from sepsis.

The first COVID-19 infection was reported in Wuhan, China, leading to the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) [

4]. COVID-19 was not only a viral pneumonia but also had many extrapulmonary complications, such as thrombosis, as highlighted in various studies [

5].

Bellosta et al. was the first to report peripheral arterial occlusion following COVID-19 infection [

6]. In a single-center study in France in 2021, 30 out of 531 hospitalized patients with COVID-19 infection developed arterial thrombosis [

7]. A previous study in New York City involving four hospitals found arterial thrombosis in 365 out of 3,334 patients [

8]. COVID-19 infection has been linked to acute limb ischemia (ALI) [

9], although the exact mechanism of thrombosis formation remains unclear. The infection increases IL-1 levels, which stimulates IL-6. This leads to inflammatory cells invading the tissue, causing endothelial injury, and increasing fibrinogen production [

10]. A hypercoagulable and procoagulant state may contribute to arterial thrombosis [

6,

8,

10]. Additionally, the virus could infect endothelial cells through angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) receptors, with inflammation causing endothelial injury, which might also subsequently contribute to the formation of free-floating aortic thrombus [

11,

12]. These thrombi could lead to ALI.

ALI following COVID-19 infection predominantly occurred in males, accounting for approximately 50-90% of cases [

6,

8,

9,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17]. Previous studies have found that ALI after COVID-19 infection is associated with a high mortality rate, ranging from 23-40% [

6,

8,

9,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17]. Two studies specifically reported a high amputation rate [

13,

14]. The occurrence of ALI in patients with pre-existing PAOD might increase mortality rates.

Recent study by Xie et al. indicated that unvaccinated individuals are more likely to develop ALI following COVID-19 infection [

5]; however, the study was limited by a small sample size (36 individuals). The protective effect of the COVID-19 vaccine in preventing ALI in PAOD patients with COVID-19 infection is unknown. To evaluate the potential benefit of the COVID-19 vaccine in improving prognosis in PAOD patients, we conducted a study by using the US Collaborative Network from 48 healthcare organizations (HCOs) in the TriNetX Research Network. We hypothesized that COVID-19 vaccination may provide protection for PAOD patients.

2. Methods

2.1. Data Source

The dataset utilized in this study was collected on July 17, 2024, from the TriNetX US Network. TriNetX is a global federated health research network providing access to electronic medical records (diagnoses, procedures, medications, laboratory values, genomic information) across large healthcare organizations (HCOs). This report was generated using the US Collaborative Network, which includes 66 HCOs. TriNetX, LLC adheres to the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA), a U.S. federal law designed to protect the privacy and security of healthcare data, along with other relevant data privacy regulations applicable to the contributing healthcare organizations. TriNetX is ISO 27001:2013 certified and maintains an Information Security Management System (ISMS) to ensure the protection of healthcare data and compliance with the HIPAA Security Rule.

All data displayed on the TriNetX Platform in aggregate form or included in any patient-level data set generated by the platform is de-identified according to the de-identification standards outlined in Section §164.514(a) of the HIPAA Privacy Rule. The de-identification process is verified through a formal determination by a qualified expert as defined in Section §164.514(b)(1) of the HIPAA Privacy Rule. Consequently, as this study involved only de-identified patient records and did not include the collection, use, or transmission of individually identifiable data, it was exempt from Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval. Additionally, the use of TriNetX in this research was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Chung Shan Medical University Hospital (CSMUH), under the approval number CS2-21176.

2.2. Study Population

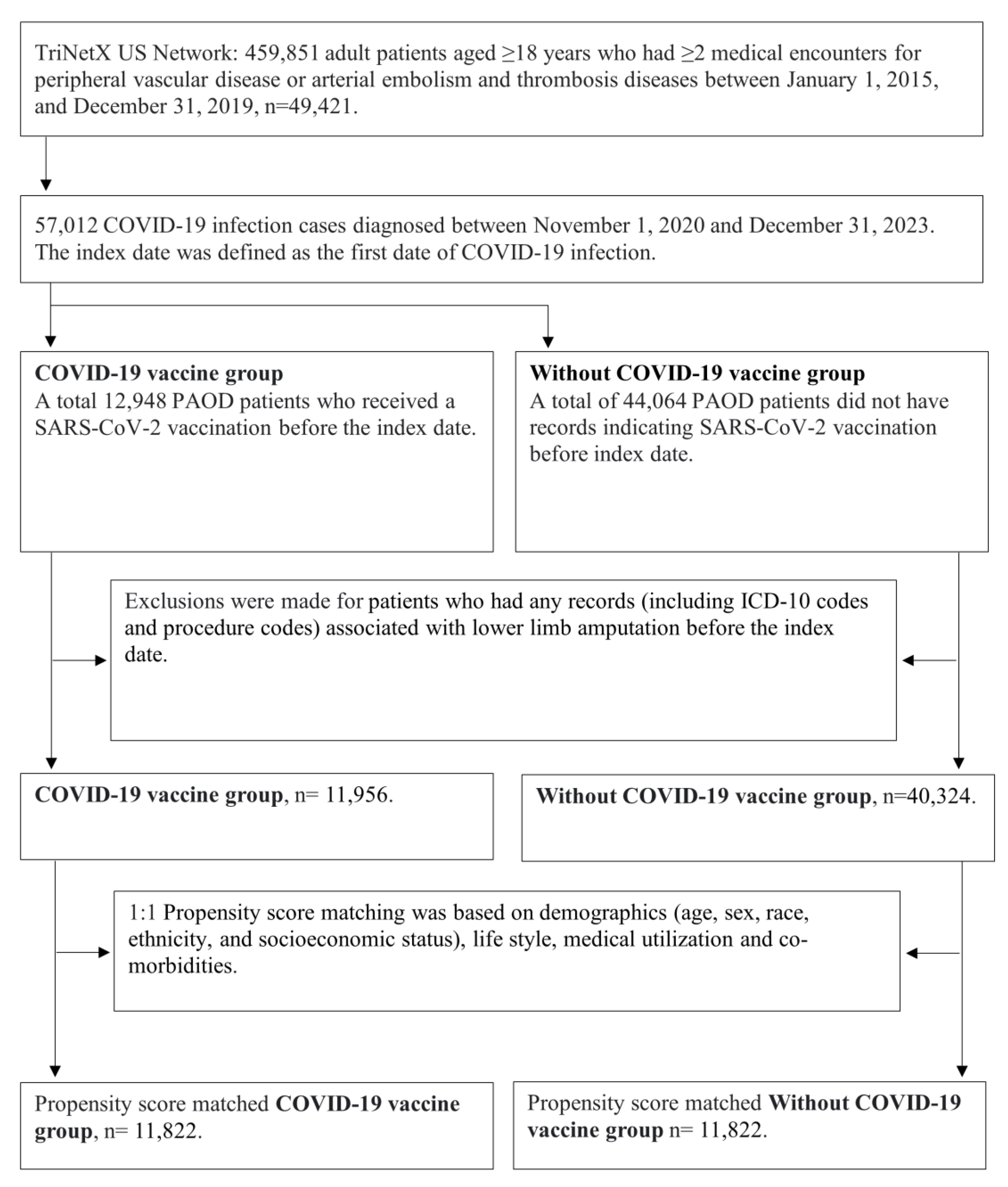

Initially, we identified 459,851 adult patients aged ≥18 years who had ≥2 medical encounters for peripheral vascular disease (ICD-10: I73.0, I73.1, I73.8, I73.9) or arterial embolism and thrombosis diseases (ICD-10: I74) between January 1, 2015, and December 31, 2019. Subsequently, we selected 57,012 COVID-19 infection cases (defined as ICD-10-CM U07.1 or PCR positive for SARS-CoV-2 RNA) that occurred between November 2020 and December 2023. Since the SARS-CoV-2 vaccine was first approved in the United States around November 2020, we only included patients who were infected with COVID-19 during the period from November 2020 to December 2023. The index date was defined as the first date of COVID-19 infection.

2.3. COVID-19 Vaccine Group

We identified 12,948 PAOD patients who received a SARS-CoV-2 vaccination before the index date. After excluding patients who had any records (including ICD-10 codes and procedure codes) associated with lower limb amputation before the index date, there were 11,956 patients with COVID-19 vaccination available for analysis.

2.4. Without COVID-19 Vaccine Group

A total of 44,064 PAOD patients did not have records indicating SARS-CoV-2 vaccination before index date. After excluding patients who had any records (including ICD-10 codes and procedure codes) associated with lower limb amputation before the index date, there were 40,324 patients with COVID-19 vaccination available for analysis.

2.5. Outcomes

The primary outcome is the 3-year risk of lower limb amputation between COVID-19 vaccinated PAOD patients and PAOD patients without COVID-19 vaccination before COVID-19 infection. The secondary outcome is the 3-year risk of ischemic stroke. For each participant, follow-up started at the index date (defined as the date of COVID-19 diagnosis) and ended at the earliest occurrence of the study outcomes or censoring at the last recorded fact within the 3-year time window in the patient’s record.

2.6. Additional Variables

To account for potential confounders, our study included covariates assessed on the index date or within 6 months prior to the index date. These covariates included demographic details (age, sex, ethnicity, race, and socioeconomic status); lifestyle factors such as BMI, nicotine dependence as an indicator of smoking habits, and alcohol-related disorders as an indicator of alcohol consumption habits; and baseline medical utilization (including preventive medicine services, inpatient encounters, and emergency visits). Additionally, we considered comorbidities including hypertensive diseases, ischemic heart diseases, heart failure, cerebrovascular diseases, diabetes mellitus, dyslipoproteinemia, chronic lower respiratory diseases, liver diseases, chronic kidney disease, chronic ulcer of the lower limb, gangrene, osteoporosis, and rheumatoid arthritis. The definitions of the study covariates are listed in

Table 1.

2.7. Statistical Analysis

Patient cohorts were propensity-score matched for baseline covariates, including demographics, lifestyle factors, medical utilization, and comorbidities. Propensity score matching was performed, and the system generated a propensity score for each patient in each cohort. The propensity score ranges between 0 and 1 and indicates the predicted probability of a patient being in the non-eradication cohort given the patient’s covariates. Logistic regression was used to generate the propensity scores through an implementation of the well-tested, standard software package scikit-learn. Data were pooled across all healthcare organizations (HCOs), so all patients in the analysis are represented as rows in one of these matrices. All missing values in each matrix were imputed as the mean from that column, depending on the variable type (binary, categorical, or continuous). We used “greedy nearest neighbor matching” with a caliper of 0.1 pooled standard deviations. A caliper of 0.1 pooled standard deviations of the propensity scores ensures that patients with very different propensity scores are not matched. TriNetX pulls data from a federated data network composed of many healthcare organizations worldwide. Each site computes a covariate matrix for the patients they contribute to the analysis and sends it to a central processing point to be pooled and analyzed as a single matrix. The order of the rows in the matrix should not impact the propensity scores generated for each patient. To eliminate any potential bias, we randomized the order of the records in the covariate matrix.

After propensity score matching, there were 11,822 pairs of PAOD patients with and without the COVID-19 vaccine (

Figure 1). The Kaplan-Meier analysis estimated the cumulative probability of lower limb amputation incidence at daily time intervals (

Figure 2). To account for patients who exited the cohort during the analysis period and therefore should not be included in the analysis, censoring was applied. In this analysis, patients were censored at the last recorded fact within the time window in the patient’s record. Cox’s proportional hazards model was used to compare the two matched cohorts. The proportional hazard assumption was tested using the generalized Schoenfeld approach. The TriNetX Platform calculated the hazard ratios and associated confidence intervals using R’s Survival package v3.2-3. All statistical tests were conducted within the TriNetX Analytics Platform, with significance set at p < 0.05 (two-sided).

3. Results

After propensity score matching, a total of 11,822 pairs of PAOD patients with and without COVID-19 vaccination were compared (

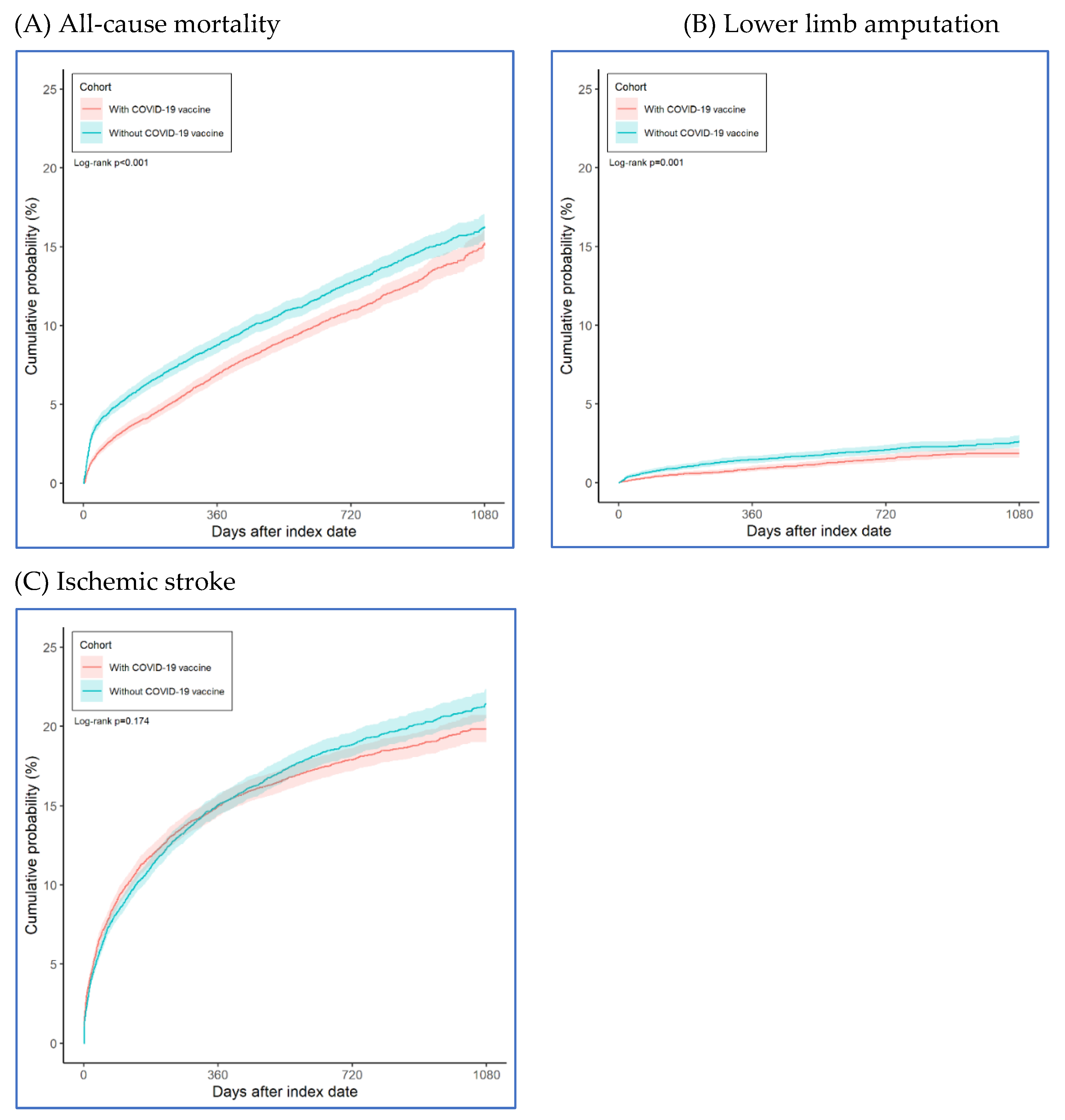

Figure 1). Compared to unvaccinated PAOD patients, those who received the COVID-19 vaccine had a significantly lower risk of 3-year all-cause mortality (log-rank test, p < 0.001) and lower limb amputation (log-rank test, p = 0.001), though there was no significant difference in ischemic stroke (log-rank test, p = 0.174). The hazard ratios were 0.857 (95% confidence interval [CI], 0.796–0.922) for all-cause mortality, 0.716 (95% CI, 0.587–0.873) for lower limb amputation, and 0.958 (95% CI, 0.902–1.019) for ischemic stroke (

Table 2).

Figure 2 illustrated the cumulative incidence of risk. PAOD patients who received the COVID-19 vaccine showed a lower risk of both all-cause mortality and lower limb amputation. However, there was no observed association between vaccination and a reduced risk of ischemic stroke in these patients.

4. Discussion

In our study analyzing data from 11,822 COVID-19 vaccine recipients and 11,822 matched controls, significant findings emerged regarding the benefits of vaccination for patients with preexisting PAOD. The results revealed that COVID-19 vaccination was associated with a reduced risk of lower limb amputation (HR=0.716, 95% CI=0.587-0.873). Additionally, vaccinated individuals demonstrated a lower risk of all-cause mortality (HR=0.857, 95% CI=0.796-0.922). Interestingly, the analysis showed no significant relationship between COVID-19 vaccination and the risk of ischemic stroke in this patient population (HR=0.958, 95% CI=0.902-1.019). These findings highlight the potential protective benefits of COVID-19 vaccination in reducing severe outcomes for patients with PAOD.

It was well established that older individuals with SARS-CoV-2 experience more severe adverse effects, more severe COVID-19, and higher mortality compared to younger people [

19]. The elderly had a relatively higher risk of cardiovascular disease, complications and mortality. In our study, the mean age was 66.5 years, consistent with previous research, which reported an age range of 60-75 years [

6,

8,

9,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17].

Our study found that patients who received the COVID-19 vaccine had lower cumulative all-cause mortality rates over time compared to previously reported data. Specifically, the 1-year, 2-year, and 3-year mortality rates were 6.9%, 10.9%, and 15.3%, respectively. These figures are significantly lower than the previously reported 23–40% mortality rate associated with acute limb ischemia following COVID-19 infection [

6,

8,

9,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17]. Our study aligns with prior research in terms of the age distribution of patients but observes a notably lower mortality rate. PAOD typically affects older individuals, and our findings may highlight the protective benefits of SARS-CoV-2 vaccination in this population. Specifically, vaccination appears to reduce mortality risk, underscoring its value as a preventative measure for patients with PAOD. This reduction may be linked to decreased occurrences of major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) or acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), both of which contribute to mortality in this population.

Bilaloglu et al. conducted a study across four hospitals in New York City, analyzing 3,334 patients with COVID-19. Among these, 365 experienced arterial thrombosis, while 207 had venous thrombosis. The overall mortality rate among these patients was 24.5% [

8]. Gonzalez-Fajardo et al. conducted a retrospective review in Spain, reviewing 2,943 COVID-19 patients. Among them, 106 developed ALI, with a reported mortality rate of 23.6% [

16]. Bautista Sánchez et al. conducted a study across six hospitals in Peru, examining 30 patients with both COVID-19 and ALI. The study reported a mortality rate of 23.3%, and 9 patients (30%) required amputation [

13]. Bellosta et al. conducted a study in Italy that reported a mortality rate of 40% among 20 COVID-19 patients with ALI [

6]. Ilonzo et al. conducted a study in New York, which found that 21 COVID-19 patients with ALI had a mortality rate of 33.3% [

17]. Goldman noted that COVID-19 patients with worse respiratory symptoms accompanied by lower limb arterial thrombosis had a high amputation rate of 25% and a mortality rate of 38% [

14]. In our study, patients who received the COVID-19 vaccine had cumulative lower limb amputation rates of 0.9% at 1 year, 1.5% at 2 years, and 1.9% at 3 years. These rates are notably lower than those reported in previous research. This finding suggests that COVID-19 vaccination may play a role in reducing lower limb amputation rates in patients with PAOD. This effect could be partially attributed to the vaccine’s potential anticoagulant properties, which may also contribute to the protection of vital organs such as the heart, lungs, kidneys, and extremities, may mitigate the risk of limb-threatening events in patients with preexisting PAOD.

Table 3 presents findings from multiple studies on the impact of COVID-19 infection on acute limb ischemia, highlighting both mortality and amputation rates.

Klok et al. reported on 184 ICU patients with COVID-19 in the Dutch, finding that 41 died, with pulmonary embolism (PE) being the most common thrombotic event. [

20]

Ackermann et al. reported autopsy studies of COVID-19 patients have shown extensive damage to the blood vessel lining, known as endothelial injury, accompanied by inflammation. These findings also include heightened blood vessel formation (angiogenesis) and widespread vascular thrombosis, indicating severe disruption of vascular integrity, including microvascular clotting and alveolar capillary obstruction [

21]. Previous research has shown that thromboembolic events and mortality were associated with the severity of COVID-19 infection [

8]. In addition to arterial thrombosis, Nopp et al. from Austria conducted a systematic review of 86 studies involving 33,970 patients with COVID-19, finding that COVID-19 infection also increased the risk of venous thromboembolism (VTE). The overall VTE prevalence was 14.1%, and subgroup analysis showed 22.7% among ICU patients [

22]. Coagulation abnormalities and coagulopathy may also contribute to the development of VTE and deep vein thrombosis (DVT). A hypercoagulable state can impair kidney function, lead to lower limb edema due to poor venous return, and exacerbate ischemia. COVID-19 further complicates this condition by causing interstitial pneumonia, reducing cardiopulmonary function, and promoting physical inactivity. This sedentary state increases the risk of DVT, further worsening vascular complications in the lower limbs. The damage to the respiratory system from these conditions often leads to ARDS, which is a life-threatening complication and a major cause of death. [

6,

13,

17].

In our study, vaccinated individuals revealed nonsignificant lower the risk of Ischemic stroke (HR=0.958, 95% CI=0.902-1.019). Covid-19 infection enters through ACE2, which was highly expressed in human tissues such as the lungs, heart, kidneys, intestines, and vascular endothelium [

18,

23]

. However, ACE2 expression was less pronounced in the brain [

23,

24], which may explain the lower incidence of ischemic stroke in COVID-19 patients. Wang et al. using data from TriNetX, reported that 4,131,717 COVID-19 survivors faced a higher risk of stroke, including both hemorrhagic and ischemic types [

25]. Lu et al. conducted a study on 5,397,278 older adults in the United States who received the COVID-19 bivalent vaccine. Both findings showed no significant increase in stroke risk during the period immediately following vaccination [

26].

5. Strengths and Limitations

The strength of our study is the first large-scale study to evaluate the impact of the COVID-19 vaccine on reducing complications in PAOD patients, including amputation rate and mortality. Given that COVID-19 infection is associated with a hypercoagulable state leading to arterial or venous thrombosis, the COVID-19 vaccine provides indirect protection and preventive effects for PAOD patients.

Our study had several limitations: First, it is a retrospective study using the US global network TriNetX database, and it did not include patients from Eastern countries. Second, during the COVID-19 pandemic, patients were often reluctant to visit hospitals due to fear of being diagnosed with COVID-19 and having to undergo quarantine policies. In the United States, the vast geographic distribution of healthcare facilities presents challenges for older adults, particularly those with PAOD. Limited mobility and pain caused by PAOD make it difficult for these patients to seek timely medical care, leading to delays in diagnosis and treatment.

This was especially true for PAOD patients, who were often mobility-impaired. Consequently, some patients may have died at home without seeking medical care, potentially leading to an underestimation of the study numbers. Third, critically ill patients who were sedated and intubated in the intensive care unit could not express issues related to lower limb pain or PAOD symptoms, which may lead to an underestimation of the study numbers. Fourth, there was potential for misclassification bias and residual confounding factors due to the use of electronic health records in the study. Fifth, we were unable to evaluate the number of vaccine doses administered using the US global network TriNetX database. Sixth, we did not know whether the Symptomatic PAOD patient was treated with thrombectomy, stent placement or bypass or only low-molecular weight heparin was used. Finally, the TriNetX database provided information only on all-cause mortality. It did not specify whether deaths following COVID-19 infection were due to MACE or ARDS, leaving the exact cause of death unclear.

6. Conclusions

In summary, our study demonstrate that patients with PAOD who received the COVID-19 vaccine had lower rates of both amputation and mortality. This protective effect may be linked to reduce cytokine storm and the vaccine’s potential anticoagulant properties, which help safeguard vital organs such as the heart, lungs, kidneys, and extremities. We recommend promoting regular physical activity and discouraging a sedentary lifestyle among PAOD patients. Additionally, encouraging COVID-19 vaccination in this population could help prevent further complications and reduce the risk of death.

Author Contributions

ST-S: YH-H, JY-H, and JCCW had full access to the study data and verified the underlying study data. ST-S led the conception, and JY-H led the data collection and data analysis. ST-S, YH-H, and JY-H wrote the original draft of this paper. ST-S, YH-H, JY-H, and JCCW contributed to the conception and writing with review and editing of this paper. All authors were involved in study design, data analysis, interpretation, and report writing, and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

Funding

There were none funding.

Data sharing statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the TriNetX Analytics Network.

https://trinetx.com./

Declaration of competing interests:

The authors declare no competing interests.

Acknowledgments

Not applicable.

References

- Hu PJ, Chen CH, Wong CS, et al. Influenza vaccination reduces incidence of peripheral arterial occlusive disease in elderly patients with chronic kidney disease. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):4847. [CrossRef]

- Hur DJ, Kizilgul M, Aung WW, et al. Frequency of coronary artery disease in patients undergoing peripheral artery disease surgery. Am J Cardiol. 2012;110(5):736-740. [CrossRef]

- Lawall H, Huppert P, Espinola-Klein C, et al. The diagnosis and treatment of peripheral arterial vascular disease. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2016;113(43):729-736. [CrossRef]

- Zhu N, Zhang D, Wang W, et al. A novel coronavirus from patients with pneumonia in China, 2019. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(8):727-733. [CrossRef]

- Xie B, Semaan DB, Binko MA, et al. COVID-associated acute limb ischemia during the Delta surge and the effect of vaccines. J Vasc Surg. 2023;77(4):1165-1173.e1. [CrossRef]

- Bellosta R, Luzzani L, Natalini G, et al. Acute limb ischemia in patients with COVID-19 pneumonia. J Vasc Surg. 2020;72(6):1864-1872. [CrossRef]

- Fournier M, Faille D, Dossier A, et al. Arterial thrombotic events in adult inpatients with COVID-19. Mayo Clin Proc. 2021;96(2):295-303. [CrossRef]

- Bilaloglu S, Aphinyanaphongs Y, Jones S, et al. Thrombosis in hospitalized patients with COVID-19 in a New York City health system. JAMA. 2020;324(8):799-801. [CrossRef]

- Indes JE, Koleilat I, Hatch AN, et al. Early experience with arterial thromboembolic complications in patients with COVID-19. J Vasc Surg. 2021;73(2):381-389.e1. [CrossRef]

- Libby P, Lüscher T. COVID-19 is, in the end, an endothelial disease. Eur Heart J. 2020;41(32):3038-3044. [CrossRef]

- Silingardi R, Gennai S, Migliari M, et al. Acute limb ischemia in COVID-19 patients: Could aortic floating thrombus be the source of embolic complications? J Vasc Surg. 2020;72(3):1152-1153. [CrossRef]

- Arbelaez DG, Sanchez GI, Gutierrez AG, et al. COVID-19-related aortic thrombosis: A report of four cases. Ann Vasc Surg. 2020;67:10-13. [CrossRef]

- Sánchez JB, Alcalde JDC, Isidro RR, et al. Acute limb ischemia in a Peruvian cohort infected by COVID-19. Ann Vasc Surg. 2021;72:196-204. [CrossRef]

- Goldman IA, Ye K, Scheinfeld MH, et al. Lower-extremity arterial thrombosis associated with COVID-19 is characterized by greater thrombus burden and increased rate of amputation and death. Radiology. 2020;297(2):E263-E269. [CrossRef]

- Cantador E, Nunez A, Sobrino P, et al. Incidence and consequences of systemic arterial thrombotic events in COVID-19 patients. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2020;50(3):543-547. [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez-Fajardo JA, Ansuategui M, Romero C, et al. Mortality of COVID-19 patients with vascular thrombotic complications. Med Clin (Engl Ed). 2021;156(3):112-117. [CrossRef]

- Ilonzo N, Rao A, Safir S, et al. Acute thrombotic manifestations of coronavirus disease 2019 infection: Experience at a large New York City health care system. J Vasc Surg. 2021;73(3):789-796. [CrossRef]

- Hu B, Huang S, Yin L. The cytokine storm and COVID-19. J Med Virol. 2021;93(1):250-256.

- Vahia IV, Jeste DV, Charles F, et al. Older adults and the mental health effects of COVID-19. JAMA. 2020;324(22):2253-2254. [CrossRef]

- Kloka FA, Kruip MJHA, van der Meer NJM, et al. Confirmation of the high cumulative incidence of thrombotic complications in critically ill ICU patients with COVID-19: An updated analysis. Thromb Res. 2020;191:148-150. [CrossRef]

- Ackermann M, Verleden SE, Kuehnel M, et al. Pulmonary vascular endothelialitis, thrombosis, and angiogenesis in COVID-19. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(2):120-128. [CrossRef]

- Nopp S, Moik F, Jilma B, et al. Risk of venous thromboembolism in patients with COVID-19: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Res Pract Thromb Haemost. 2020;4(7):1178-1191. [CrossRef]

- Beyerstedt S, Casaro EB, Rangel ÉB. COVID-19: Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) expression and tissue susceptibility to SARS-CoV-2 infection. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2021;40(5):905-919. [CrossRef]

- Mohammed M, Berdasco C, Lazartigues E. Brain angiotensin converting enzyme-2 in central cardiovascular regulation. Clin Sci (Lond). 2020;134(19):2535-2547. [CrossRef]

- Wang W, Wang CY, Wang SI, Wei JCC. Long-term cardiovascular outcomes in COVID-19 survivors among non-vaccinated populations: A retrospective cohort study from the TriNetX US collaborative networks. EClinicalMedicine. 2022;53:101619. [CrossRef]

- Lu Y, Matuska K, Nadimpalli G, et al. Stroke risk after COVID-19 bivalent vaccination among US older adults. JAMA. 2024;331(11):938-950. [CrossRef]

- Etkin Y, Conway AM, Silpe J, et al. Acute arterial thromboembolism in patients with COVID-19 in the New York City area. Ann Vasc Surg. 2021;70:290-294. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).