1. Introduction

Early Childhood Caries (ECC) is the early onset of dental caries lesions in young children that often progress rapidly, ultimately resulting in complete destruction of the primary dentition [

1]. ECC is defined as the presence of one or more decayed (non-cavitated or cavitated lesions), missing, or filled surfaces in any primary tooth of a child under the age of six [

1]. Dental caries disease, in its severe stage, is a clinical indicator (dental caries lesion) observed in the tooth surface. Untreated dental caries affects approximately 514 million children worldwide [

2].

Epidemiological data on dental caries in young children across Latin America is limited, particularly for those under 2 years old, with most information coming from small study samples. However, existing evidence shows moderate to high prevalence (>50%) among 5–6 and 12-year-olds [

3,

4]. ECC has serious consequences, including pain [

5], infections [

6], sleep [

7] and nutritional problems [

8], and impaired physical, social, and academic development [

9,

10], negatively impacting both the child and their family. The burden of severe dental caries falls disproportionately on socially disadvantaged groups, where poor oral hygiene, unhealthy diets, and limited access to care, driven by social determinants, worsen outcomes.

Dental caries in children is a complex and multifactorial disease with various contributing factors. Notably, during the early years of life, maternal influences such as attitudes, beliefs, and behaviors regarding feeding and nutrition can significantly impact a child's overall and oral health in the long term [

7]. The first 1000 days of life are a critical period for human development, and exposures during this time can program metabolism, leading to modifications in organ/system structure and function and impacting health status later in life [

11]. Also, microbiome formation and stabilization for later health coping is extremely sensitive during this time period [

12]. Therefore, maternal and family influences, shaped by behavior and conditioned by the environment, play a crucial role in oral health. However, most research has focused on the management of dental caries lesions in secondary and tertiary care, and limited scientific evidence is available regarding a comprehensive approach to health and disease prevention, starting with an understanding of how maternal behaviors might affect disease onset and progression.

In order to enhance the management of dental caries disease in children under six years old, it is crucial to improve the implementation of evidence-based practices and promote behavioral changes at the public health level. PRECEDE stands for ‘Predisposing, Reinforcing and Enabling Causes in Educational Diagnosis and Evaluation’ in planning health education [

13]. The PRECEDE-PROCEED model is a planning framework that adopts an ecological approach to health promotion, encompassing all aspects of an individual's environment as potential intervention targets, as well as their own cognitions, skills, and behaviors [

13]. This model enables the evaluation of socio-psychological health behaviors and provides guidance for the development of the logic model of the health problem, facilitating effective health programming [

14]. Despite its effectiveness in assessing health problems, few studies have utilized this model in dental care. For instance, this model has been used in dentistry, with a primary focus in adult, elderly and aboriginal populations in countries such as US, Canada, Australia, Iran, and China [

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20]. However, the implementation of the model to analyze the factors that influence dental caries disease in children under age 6, especially during the 1000 days of life in Latin American populations is unknown.

In recent years, interest has grown in exploring children’s oral health outcomes using a broader framework, incorporating psychosocial, behavioral and environmental predictors, with biological measures, to prove a comprehensive concept of oral health and its preservation.

From a clinical and public health perspective, implementing theory and evidence based, oral health programs with a clear framework for addressing dental caries in children is essential [

21]. This study comprises the first step (building a Logic Model of the Problem and conducting a needs assessment) of a parent research that applies the Intervention Mapping Framework to develop a theory- and evidence-based Health Promotion Program “Smiley Baby” (HPP-SB) to enhancing child-family health behaviors during the first 1000 days of life. HPP-SB was developed as an innovative, behaviorally-informed intervention that integrates educational and community strategies to promote healthy diet behaviors, oral hygiene practices, and access to health services, while addressing psychosocial and environmental barriers to behavior change. Its components, professional training, mother-infant health promotion, and family support, are guided by behavioral constructs such as knowledge, self-efficacy, and outcome expectations. To inform the development and contextual relevance of this program, formative work is required to understand the factors influencing dental caries risk. Thus, the aim of the study is to apply the PRECEDE-PROCEED as a conceptual framework to describe the social, behavioral, and environmental factors associated with onset of dental caries disease in Latin American children.

2. Materials and Methods

The PRECEDE component of the PRECEDE–PROCEED framework was used as an educational diagnostic model to develop the logic assessment of the problem.

The model development in this study followed 3 phases:

- (1)

Social assessment: The priority population was defined in three domains: 1) Demographic factors of age, gender, ethnicity, location, socioeconomic status, and education, 2) the oral health problem including its short- and long-term effects, and 3) quality of life outcomes.

- (2)

Behavioral, and environmental assessment: The behavioral and environmental factors linked to the oral health issue in the target population were identified.

- (3)

Educational and Ecological assessment: Determinants of health behaviors were identified and classified as predisposing (e.g., knowledge, attitudes, self-efficacy), reinforcing (e.g., social support, peer influence), and enabling (e.g., availability, skills, resources) factors.

Data to inform the model was gathered through a secondary quantitative and qualitative data analysis from a longitudinal pilot study among Latino mother-children dyads in Caracas, Venezuela conducted in 2020 and an in-depth literature review.

2.1. Pilot Study

The Smiley Baby Pilot Project (SBP) was a 2-year longitudinal study (2019–2022) conducted at the Central University of Venezuela, Faculty of Dentistry, to evaluate the impact of an educational program on dental caries and its risk factors among 0-24 months-old infants. The pilot study included five encounters (at 0–2, 6, 12, 18, and 24 months of age) involving microbiological sampling, oral health education, and clinical and risk factor assessments. Microbiological results have been previously published [

22].

Infants were eligible if they met the following criteria: gestational age >35 weeks, birth weight ≥2500 g, age 0–2 months, and middle-class socioeconomic status. Exclusion criteria included systemic disease or immune deficiency, presence of teeth, oral pathologies, age >2 months, or birth weight <2500 g. Parental or guardian written consent was obtained. The study was approved by the Bioethical Committee of the Central University of Venezuela, Faculty of Dentistry (CB-106-2019).

Information on gestational age, delivery mode, health status, feeding practices, medical history, and antibiotic use was collected through parental interviews and recorded in a study-specific clinical chart. Mothers' knowledge and perceptions of dental caries were assessed with three questions at baseline and at 24 months. Dental caries risk was evaluated using a validated questionnaire (CVI=89.6, α=0.925) and follow-up phone interviews were conducted. Risk levels were classified as low (no risk factors), medium (one), high (two), or severe (all). After each encounter, an oral health educational program was delivered.

As part of this pilot an in-depth literature review was conducted. Electronic publication from databases of Medline, PubMed, and Scielo. The literature review focused on empirical and theoretical associations between dental caries disease, oral health outcomes and quality of life, common risk factors for dental caries and other chronic diseases, maternal behaviors related to poor oral health outcomes, salient behavioral theories associated with improved oral health practice, and oral health determinants and inequalities among Latin American populations. Consensus among researchers was sought to select relevant studies for review. Inclusion criteria include papers published between 2010 – 2025, English or Spanish language. Commentaries, editorials and short reviews were excluded.

2.2. Statistical Analysis

Secondary quantitative data was analyzed through descriptive statistics obtaining measures of center (means, medians) and spread (percentiles and SD). Association between variables was conducted using Fisher’s test with an alpha of 0.05. STATA software version 17.0 was used for statistical analysis. For qualitative data obtained through the interviews and health charts an inductive thematic analysis was performed. Two members of the research team coded the data and agreed on main themes and sub-themes to summarize the findings.

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of Mother-Infant Dyads

Demographic characteristics of mother-infant dyads are depicted in

Table 1. Mother’s mean age was 29.0±7.4years. Most of the sample belonged to the middle-high socioeconomic group (40%), while equal proportions were found amongst the other groups except for middle-low whom no one was classified, and half of the mothers completed graduate studies. The majority reported having regular medical visits with the gynecologist during pregnancy, while only 20% reported going to the dental professional for a preventive visit.

All the infants in this study were born after 37 weeks of gestation with low variation (38.6±0.97), and the gender ratio was 1:1. Four infants were delivered vaginally and six by cesarean section. Six of the infants were exclusively fed breast milk directly from the mother’s breast (EB), three were fed using a combination of breastmilk and formula using a bottle (C), and only one was exclusively fed with breastmilk using both a bottle and mother’s breast (EBB). The infants’ 50th percentile was 3,240 grams (range 3,000 to 4,200 grams) with a variability of IQR=330g. Half of the infants at baseline were at high risk of dental caries lesion, while 20% of the sample had severe risk and only 10% had either medium or low risk. (

Table 1.) Conversely, at the last follow up (24 months) around 60% of infants were at a low risk. Dental caries lesions were significantly associated with risk factor level. (

Table 2.)

3.2. Maternal Behaviors

Maternal perceptions and knowledge are reported in

Table 3. Most of the sample (60%) considered that taking the infant to the pediatric dentist should be done when the child has all of its primary dentition. Most (<60%) understood that a child’s oral care starts during the first trimester.

Themes and subthemes regarding behavioral constructs are presented in

Table 4. Major themes include health beliefs, social norms, self-efficacy and separate systems of oral and medical care.

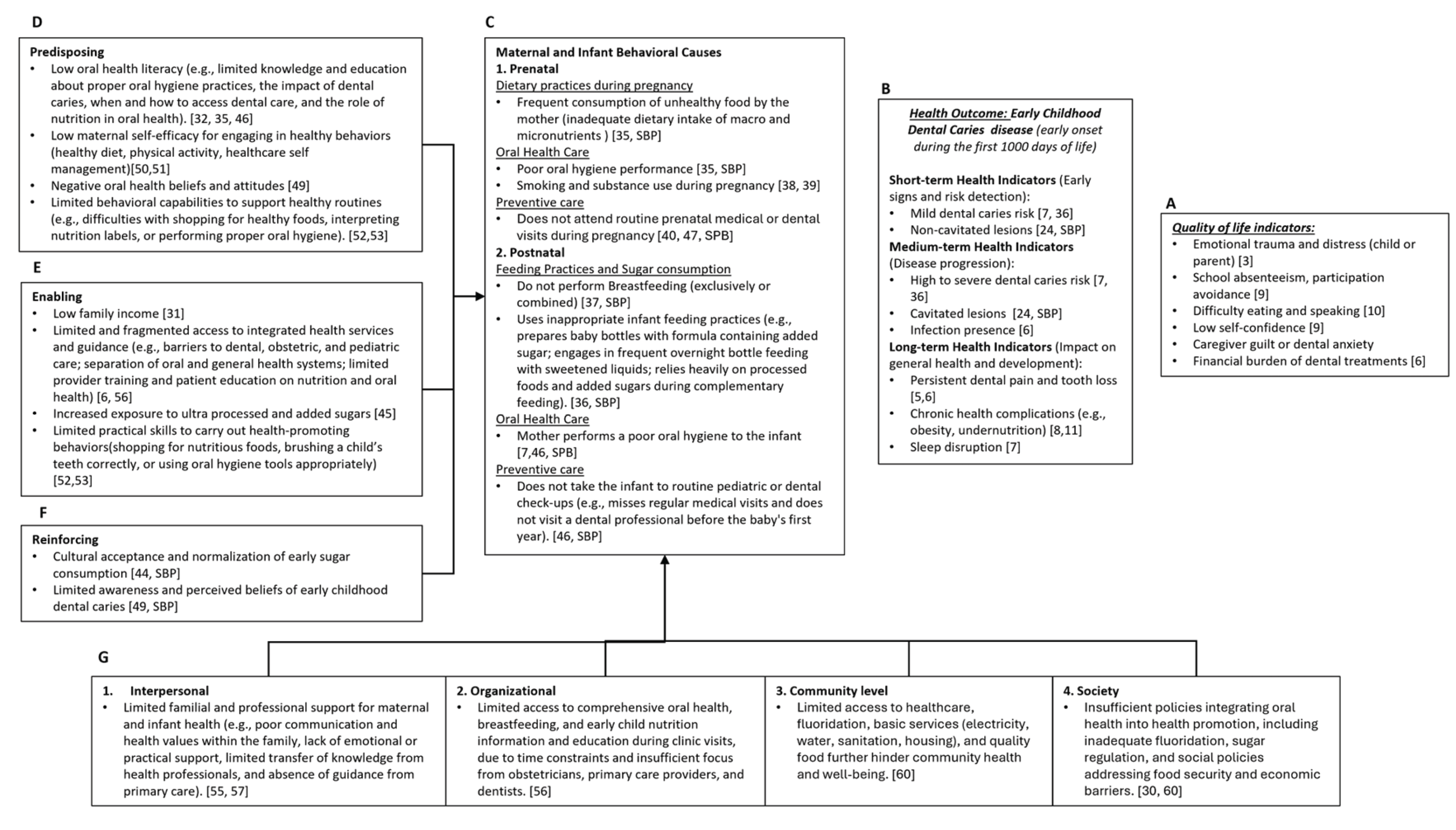

3.3. PRECEDE Model of Maternal Behaviors and Early Childhood Dental Caries

The model emergent from this study can be seen in

Figure 1.

3.3.1. Epidemiology and Social Assessment

The model illustrates how quality of life (QOL), including physical, social, and family-related dimensions (1.A) is affected by early-onset dental caries during the first 1000 days of life (1.B). In the short term, early indicators include mild caries risk and non-cavitated lesions, often associated with poor oral hygiene and dietary practices. As the disease progresses, medium-term indicators emerge, such as high to severe caries risk, cavitated lesions, visible tooth decay, oral infections, and declining oral health, which interfere with basic functions like eating, sleeping, and hygiene. Long-term indicators reflect the cumulative impact of untreated disease and include persistent dental pain, tooth loss, sleep disruption, and chronic health conditions such as obesity and undernutrition. Psychosocial effects, such as speech difficulties, emotional distress, and reduced self-esteem, further compromise child development, while caregivers face significant emotional and financial burdens. Globally and locally, childhood dental caries remains a major health burden, affecting 50–80% of children aged 5–7 [

2,

3].

3.3.2. Behavioral Assessment

Maternal behavioral causes (1.C) are grouped as: (1) Prenatal (e.g., prenatal diet, maternal oral health, preventive care use); and (2) Postnatal (e.g., feeding practices, infant oral care, healthcare utilization).

3.3.3. Behavioral Determinants and Environmental Assessment

Predisposing factors (1.D) include psychosocial and cognitive determinants such as low oral health literacy, low maternal self-efficacy to engage in health behaviors, negative oral health beliefs and attitudes, and limited behavioral capabilities to support healthy routines. Enabling factors (1.E) encompass structural and systemic conditions including low family income, limited and fragmented access to integrated health services, inadequate provider training and patient education, increased exposure to ultra-processed and added sugars, and limited practical skills to carry out health-promoting. Reinforcing factors (1.F) involve prevailing social norms and perceptions, such as the cultural normalization of early sugar consumption and limited awareness and perceived severity of early childhood dental caries.

4. Discussion

Dental caries is a preventable disease, yet its global burden remains persistently high [

23]. Although interest in broader oral health frameworks is increasing, a deeper understanding of its multifactorial origins is still needed. Traditionally viewed through a bio-ecological lens, most prevention targets moderate to severe stages marked by clinical indicators (caries lesions) [

24,

25,

26,

27,

28]. However, behavioral, psychosocial, and socio-ecological factors influencing early disease onset remain underexplored.

Given these considerations, understanding the socio-ecological context (behavioral and environmental factors) in dental caries onset and progression is essential for prevention and health promotion [

29]. The model emergent in this study represents a first step toward addressing this gap and is, to the authors' knowledge, the first conceptual model linking maternal behaviors to dental caries during the first 1000 days of life in a Latin American population.

The Health Problem and the Priority Population

This model targets Latin American mother–child dyads (ages 0–2) living in low-income, underdeveloped settings like Venezuela, where socioeconomic vulnerability heightens the risk for oral health disparities. Low socioeconomic status is positively associated with dental caries (OR = 1.21 [1.03–1.41]; OR = 1.48 [1.34–1.63]) [

30], emphasizing the need for early intervention. Although the exact origins of dental caries remain unclear, assessing risk factors before tooth eruption is critical, as shared maternal–infant environments and behaviors during this window may contribute to disease development [

11,

12].

The model reframes the health issue as Early Childhood Dental Caries during the first 1,000 days (1000ECDC), referring to the early onset of a chronic, multifactorial, non-communicable disease, biologically regulated, behaviorally modulated (maternal/family influences), and socio-ecologically conditioned (non-medical drivers of health) that begins with microbiome imbalance and the rupture of homeostatic stability in the first 1000 days due to adverse bio- and socio-ecological factors. If unaddressed, maternal psycho-social instability persists, influencing dysbiosis [

22,

29]. With tooth eruption under such conditions, severe dental caries lesions may emerge before age six [

1].

Redefining the health problem responds to several conceptual gaps: the need to clarify terminology by distinguishing between dental caries as a disease (affecting the individual) and as a lesion (affecting the tooth); the importance of focusing on disease determinants rather than late-stage clinical indicators; and the need to recognize that health encompasses physical, mental, and social well-being, which are all relevant in the context of maternal–infant health and dental caries prevention.

Currently, no tools exist to detect 1000ECDC in its early stages. Surveillance systems rely on clinical symptoms, overlooking the behavioral and psychosocial drivers. Additionally, data from regions like Latin America are limited and non-generalizable, underscoring the need for more context-specific research. This model provides a broader conceptualization of the problem to inform the development of improved risk assessment tools that account for behavioral, social, and environmental factors. It also highlights the broader quality-of-life impacts of 1000ECDC, beyond visible tooth damage, including pain, poor nutrition, low self-esteem, and social disruption. For infants, maternal perception becomes essential in recognizing distress and seeking care. As shown in this study, findings from the SBP emphasize the importance of maternal emotional and social responsiveness, reinforcing the need for holistic, early-stage interventions.

Behavioral Assessment

The model explores the mother–infant dyad through two components (maternal and infant) and three behavioral factors across two stages: prenatal (270 days) and postnatal (birth to age two, 730 days). Maternal health and behaviors during the first 1,000 days may predict early oral microbiome dysbiosis in the infant, while infant health indicators reflect the presence of early childhood dental caries (1000ECDC). In both cases, maternal behaviors are key determinants.

The three behavioral factors, (1) dietary and feeding behaviors, (2) oral health care behaviors, and (3) healthcare service utilization, are considered in both stages. In the prenatal stage, maternal behaviors (e.g., diet, oral hygiene, preventive care, tobacco use, physical activity) affect both her own health directly and the infant indirectly. Postnatally, maternal behaviors directly impact the infant, beginning with delivery mode and continuing with feeding practices, oral care, preventive care, and other health-related actions (e.g., medication adherence, sanitation).

Research has predominantly focused on postnatal behaviors, where maternal actions shape the child’s oral health care, diet, dental visits, and treatment decisions [

31,

32]. Negative parental behaviors (e.g., poor feeding or toothbrushing practices) are linked to higher rates of untreated dental caries in young children (PRa = 1.213; 95% CI: 1.032–1.427, p = 0.019) [

33]. These behaviors are influenced by maternal education, stress, beliefs, attitudes, and cultural norms. In contrast, prenatal behaviors are often overlooked in dental caries research despite evidence linking poor maternal nutrition, inadequate oral care, and limited dental service use to biological conditions like chronic disease and microbiome dysbiosis, which may predispose infants to chronic diseases, including 1000ECDC.

Prenatal and Postnatal Risk Behavioral Factors

The model highlights how maternal behaviors, both during pregnancy and after childbirth, influence the development of 1000ECDC. One key risk behavioral factor involves dietary and feeding practices. In the prenatal stage, mothers may have an inadequate intake of essential macronutrients, while in the postnatal stage, they often engage in non-nutritive or unhealthy feeding practices for the child, such as not breastfeeding, using bottles with added sugars, overnight feeding, and inadequate complementary feeding. These behaviors result in both deficient intake of critical nutrients and excessive consumption of simple and added sugars, often exceeding 5-10% of the recommended daily caloric intake [

34], while failing to include protective foods like fiber, prebiotics, nitrate-rich vegetables, and good-quality proteins. This dietary imbalance disrupts the oral microbiome and contributes to dental caries development. Evidence supports the association between poor maternal diet and increased caries risk in children (e.g., OR 1.63 [1.15–2.31]) [

35], and unhealthy snacking in young children has also been linked to moderate dental caries lesions (OR 2.54 [1.25–5.13]) [

36]. Breastfeeding up to one year, in contrast, appears protective (OR 0.50 [0.25–0.99]) [

37] and has been considered a protective behavior to maintain the stability of the oral microbiome [

22]. Although data specific to Latin American children under two are limited, findings from the SBP suggest early sugar exposure may be a high-risk factor, with about 50% of participants at high risk and 25% already developing lesions at follow-up.

The other two risk behavioral factors, oral health care behaviors and dental care utilization, are interconnected yet distinct factors of 1000ECDC. While both influence oral health outcomes, they operate through different mechanisms: one through daily practices, the other through engagement with professional care.

Oral health care behaviors refer to routine hygiene and self-care actions. In the prenatal stage, this includes maternal risk behaviors such as infrequent tooth brushing and flossing, as well as harmful practices like smoking, substance use, and inappropriate antibiotic consumption. In the postnatal stage, these behaviors affect the child directly, for instance, disregarding brushing the child’s teeth, not using adequate fluoridated toothpaste, or failing to instill consistent oral hygiene routines [

7,

31,

32]. Evidence shows that mothers with poor oral hygiene are 2.49 times more likely to have children with dental caries lesions in their primary teeth [

35]. Additionally, maternal smoking during pregnancy significantly increases dental caries risk (OR 1.57 [1.47–1.67]; RR 1.26 [1.07–1.48]) [

38], and maternal substance use is associated with nearly twice the risk of lesions in offspring (OR 1.96 [1.80–2.14]) [

39].

Dental care utilization, in contrast, refers to the timely use of preventive or therapeutic oral health services. During pregnancy, many women do not seek dental care, despite being more susceptible to oral problems due to hormonal changes, altered diet, and oral hygiene challenges [

40]. Postnatally, mothers often delay or forgo early dental visits for their infants, missing critical windows for prevention [

41]. For example, global data indicate that only 24% of pregnant women access dental services during pregnancy, although there is evidence that suggested a protective effect of prenatal oral health care against dental caries onset before 4 years of age (OR 0.12 (0.02, 0.77) at 1 year of age) [

42]. Additionally, SBP findings reveal that 90% of participating mothers did not attend a preventive dental visit while pregnant. This underutilization of care limits opportunities for early diagnosis, counseling, and intervention.

Behavioral Determinants

In the context of 1000ECDC-related behaviors, behavioral determinants operate at both individual and environmental levels. At the individual level, maternal knowledge, beliefs, attitudes, and cultural practices act as predisposing factors that shape behaviors around infant nutrition, oral hygiene, and healthcare utilization [

43]. For example, a mother's understanding of the importance of proper dietary practices, oral health care, and regular healthcare service utilization during pregnancy and infancy can significantly influence her behaviors. Cultural norms surrounding infant feeding practices and oral hygiene also play a pivotal role in shaping predisposing factors [

44], while increased exposure to ultra processed and added sugars [

45] and limited behavioral capabilities to support healthy routines [

42] work as enablers. Meanwhile, environmental factors, including socioeconomic conditions and access to healthcare, act as enabling or constraining forces. In Venezuela, similar to other Latin American countries, ongoing economic instability, widespread shortages, and an underfunded health system limit families’ access to nutritious food, oral care products, and basic medical services. These constraints make it difficult for mothers to implement healthy behaviors, despite having the knowledge or intention to do so. Reinforcing factors, such as social support, peer influence, and cultural norms, further shape behavioral patterns [

44]. In the absence of supportive networks or in the presence of societal norms that deprioritize oral health, negative behaviors can persist. However, community-driven efforts, peer encouragement, and cultural shifts toward recognizing the importance of early oral health can reinforce and sustain positive changes.

At the individual level, knowledge plays a foundational role in shaping behaviors, particularly regarding oral health and dietary choices. Low health literacy is strongly linked to poor nutritional behaviors and suboptimal oral health outcomes [

46]. Research has shown that pregnant women who receive educational interventions about oral hygiene and nutrition are more likely to have children with fewer dental caries lesions [

47]. Furthermore, studies consistently associate low parental education and income with worse oral health outcomes in children, underscoring the importance of improving oral health literacy among expectant mothers [

31]. Findings from SBP data indicate notable gaps in parental understanding, especially around the timing of dental visits and the importance of early preventive care. While increasing knowledge is essential, it is not sufficient on its own; behavioral change requires a broader, multifaceted approach. In fact, despite having adequate knowledge, many mothers face a behavioral challenge in translating that knowledge into action. Without the presence of other constructs, such as self-efficacy, motivation and ability to adopt health-promoting behaviors may remain limited. Studies show that knowledge alone does not consistently lead to behavior change unless accompanied by the confidence and perceived capability to act on that knowledge [

48].

Self-efficacy, or a mother’s belief in her ability to manage her and her child’s health, is a key psychosocial determinant of behavior. Latina mothers with high self-efficacy are more confident in performing preventive practices, such as brushing their child’s teeth and limiting sugary snacks [

49]. Studies show an inverse relationship between self-efficacy and poor dietary behaviors, as well as with inconsistent oral hygiene routines like toothbrushing and flossing [

50,

51]. In the context of the SBP study, mothers reflected on their perceived ability to care for their child’s oral health, highlighting the importance of strengthening self-efficacy to enable behavior change.

Skill level determinants also influence health behaviors. Many caregivers lack the practical skills to enact health behaviors, for instance, reading nutrition labels or correctly performing oral hygiene. Research shows that while Hispanic families may be familiar with food labels, fewer than half feel confident using them to make healthier choices [

52]. Similarly, low oral care skills, such as improper toothbrushing technique, can lead to poor oral health outcomes even when knowledge is present [

53]. These skill gaps contribute to the persistence of unhealthy behaviors and increase the risk of dental caries.

At the environmental level, interpersonal and societal factors create both opportunities and barriers for behavior change. Social support systems, such as family encouragement and provider guidance, are critical [

54,

55]. Positive interpersonal interactions, particularly within the healthcare system, can promote early dental visits and consistent care [

56]. Hispanic mothers with strong family support and are significantly more likely to access dental services [

57]. However, the lack of coordinated communication among healthcare professionals often limits the effectiveness of interventions. Studies have shown that when providers use behavioral techniques like motivational interviewing or anticipatory guidance, patients are more likely to adopt positive oral health behaviors and have fewer dental lesions [

58].

At the societal level, structural inequalities, including economic hardship, inadequate education systems, and disjointed healthcare infrastructure, profoundly shape maternal behaviors and children’s oral health outcomes. In urban Venezuela, poverty and food insecurity limit access to healthy diets, mirroring challenges seen in rural populations and similarly reflected in other Latin American countries [

59,

60]. These conditions not only restrict families’ ability to adopt healthy behaviors but also perpetuate oral health disparities across generations. Although these societal-level factors are difficult to address directly, interventions at the interpersonal level, such as empowering dental teams to communicate effectively, identify risk behaviors, and apply behavior change strategies, offer actionable pathways to support maternal and child oral health during the first 1,000 days.

Limitations

These findings should be interpreted in light of the study’s limitations. The small sample size of 10 in-depth interviews, while sufficient to guide the development of the SBP in this pilot phase, limits the generalizability of the results. Future studies in other contexts and Latin American countries are indicated. Additionally, the current work is largely a theoretical conceptualization, reflecting the novelty of applying behavioral science to dentistry, with evolving concepts that are still under research. Despite these limitations, this study serves as the first of its kind to propose a comprehensive behavioral model for understanding the early onset of dental caries in a Latin American population. As such, it offers a valuable and novel contribution, providing a contextualized framework that can inform future research and intervention development in other settings across the region.

Future research should aim to validate and expand this model through mixed-methods and longitudinal designs with larger, more diverse samples across Latin America, evaluating its predictive value, adaptability, and utility in guiding intervention design. The model offers strong potential to inform the development of culturally tailored, theory-driven interventions rooted in implementation science, supporting the integration of oral health into maternal and child health programs. It also holds policy relevance, underscoring the need for intersectoral collaboration and upstream actions such as early childhood oral health integration, nutrition regulation, and provider training. Advancing this work will require multidisciplinary efforts to co-design and scale sustainable, equitable interventions that improve oral health from the earliest stages of life.

5. Conclusions

Early Childhood Dental Caries during the first 1,000 days (1000ECDC) is a complex health problem attributable to a series of risk factors. In particular, maternal influences, both at prenatal and postnatal stages, are of great importance. Maternal attitudes, skills, self-efficacy and beliefs impact behaviors that can play a pivotal role in the mother’s own health as well as the infant’s long-term general and oral health. Unraveling the determinants of behaviors related to 1000ECDC involves a comprehensive exploration of predisposing, enabling, and reinforcing factors. Interventions aimed at improving oral health outcomes must address these determinants comprehensively, considering the unique challenges posed by the environmental context. This approach ensures a more nuanced and effective strategy for promoting positive behaviors and mitigating the risk factors associated with the early onset of dental caries in children. Additionally, study findings supported the contention that the design and implementation of an 1000ECDC program for maternal to infant healthcare that promotes lifelong oral health needs to account for multiple quality of life, epidemiologic, behavioral, and psychosocial factors that contribute to oral health. The PRECEDE model provides a comprehensive, theory- and evidence-informed framework to guide the development of targeted, early-life oral health promotion interventions, an approach that may hold valuable utility for application in other Latin American communities

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, AGQ, AFP, SF, AA.; methodology, AGQ.; data curation, ST.; writing—original draft preparation, AGQ.; writing—review and editing, RS and EH. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The Smiley Baby Pilot received funding from the David Scott Fellowship from the International Association for Dental and Craniofacial Research (IADR).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Bioethical Committee of the Central University of Venezuela, Faculty of Dentistry (CB-106-2019).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data availability can be requested through the investigator team contacting the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge Centro Social Don Bosco and its community of “Damas Salesians” their support during the recruitment of participants in the Smiley Baby Pilot.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| 1000ECDC |

Early Childhood Dental Caries during the first 1,000 days |

| ECC |

Early Childhood Caries |

| SPB |

Smiley Baby Pilot |

References

- Machiulskiene, V.; Campus, G.; Carvalho, J.C.; et al. Terminology of Dental Caries and Dental Caries Management: Consensus Report of a Workshop Organized by ORCA and Cariology Research Group of IADR. Caries Res. 2020, 54(1), 7–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Global Oral Health Status Report: Towards Universal Health Coverage for Oral Health by 2030; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Paiva, S.M.; Abreu-Placeres, N.; Camacho, M.E.I.; Frias, A.C.; Tello, G.; Perazzo, M.F.; et al. Dental caries experience and its impact on oral health-related quality of life in Latin American and Caribbean countries. Braz. Oral Res. 2021, 35 (Suppl 1), e052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gimenez, T.; Bispo, B.A.; Souza, D.P.; et al. Does the Decline in Caries Prevalence of Latin American and Caribbean Children Continue in the New Century? PLoS ONE 2016, 11(10), e0164903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rathee, M.; Sapra, A. Dental Caries. In StatPearls [Internet]; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Casamassimo, P.S.; Thikkurissy, S.; Edelstein, B.L.; Maiorini, E. Beyond the dmft: The Human and Economic Cost of Early Childhood Caries. J. Am. Dent. Assoc. 2009, 140(6), 650–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tinanoff, N.; Baez, R.J.; Diaz Guillory, C.; et al. Early Childhood Caries Epidemiology, Aetiology, Risk Assessment, Societal Burden, Management, Education, and Policy: Global Perspective. Int. J. Paediatr. Dent. 2019, 29(3), 238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshall, T.A.; Eichenberger-Gilmore, J.; Broffitt, B.A.; Warren, J.J.; Levy, S.M. Dental Caries and Childhood Obesity: Roles of Diet and Socioeconomic Status. Community Dent. Oral Epidemiol. 2007, 35(6), 449–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruff, R.R.; Senthi, S.; Susser, S.R.; Tsutsui, A. Oral Health, Academic Performance, and School Absenteeism in Children and Adolescents: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Am. Dent. Assoc. 2019, 150, 111–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granville-Garcia, A.F.; Gomes, M.C.; Perazzo, M.F.; Martins, C.C.; Abreu, M.H.N.G.; Paiva, S.M. Impact of caries severity/activity and psychological aspects of caregivers on oral health-related quality of life among 5-year-old children. Caries Res. 2018, 52, 570–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Indrio, F.; Martini, S.; Francavilla, R.; et al. Epigenetic Matters: The Link between Early Nutrition, Microbiome, and Long-Term Health Development. Front. Pediatr. 2017, 5, 178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romano-Keeler, J.; Sun, J. The First 1000 Days: Assembly of the Neonatal Microbiome and Its Impact on Health Outcomes. Newborn 2022, 1(2), 219–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gielen, A.C.; McDonald, E.M.; Gary, T.L.; Bone, L.R. Using the PRECEDE-PROCEED Model to Apply Health Behavior Theories. In Health Behavior and Health Education: Theory, Research, and Practice, 4th ed.; Glanz, K., Rimer, B.K., Viswanath, K., Eds.; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2008; pp. 407–433. [Google Scholar]

- Bartholomew, L.K.; Mullen, P.D. Five Roles for Using Theory and Evidence in the Design and Testing of Behavior Change Interventions. J. Public Health Dent. 2011, 71 (Suppl 1), S20–S33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binkley, C.J.; Johnson, K.W. Application of the PRECEDE-PROCEED Planning Model in Designing an Oral Health Strategy. J. Theory Pract. Dent. Public Health 2013, 1(3). Available online: http://www.sharmilachatterjee.com/ojs-2.3.8/index.php/JTPDPH/article/view/89.

- Knazan, Y.L. Application of PRECEDE to Dental Health Promotion for a Canadian Well-Elderly Population. Gerodontics 1986, 2(5), 180–185. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Dimitropoulos, Y.; Holden, A.; Gwynne, K.; et al. An Assessment of Strategies to Control Dental Caries in Aboriginal Children Living in Rural and Remote Communities in New South Wales, Australia. BMC Oral Health 2018, 18(1), 177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghaffari, M.; Rakhshanderou, S.; Asadpour, M.; et al. Design, Implementation, and Evaluation of a PRECEDE-PROCEED Model-Based Intervention for Oral and Dental Health among Primary School Students of Rafsanjan City: A Mixed Method Study. BMC Public Health 2021, 21(1), 1609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nomura, Y.; Matsuyama, T.; Fukai, K.; et al. PRECEDE-PROCEED Model Based Questionnaire and Saliva Tests for Oral Health Checkup in Adult. J. Oral Sci. 2019, 61(4), 544–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Cao, J.; Lin, H.; et al. Community Health Needs Assessment with PRECEDE-PROCEED Model: A Mixed Methods Study. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2009, 9, 181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Quintana, A.; Díaz, S.; Cova, O.; et al. Caries Experience and Associated Risk Factors in Venezuelan 6-12-Year-Old Schoolchildren. Braz. Oral Res. 2022, 36, e026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Quintana, A.; Frattaroli-Pericchi, A.; Feldman, S.; et al. Initial Oral Microbiota and the Impact of Delivery Mode and Feeding Practices in 0 to 2 Month-Old Infants. Braz. Oral Res. 2023, 37, e078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kassebaum, N.J.; Smith, A.G.C.; Bernabé, E.; et al. Global Burden of Untreated Caries: A Systematic Review and Metaregression. J. Dent. Res. 2015, 94 (5), 650–658. GBD 2017 Oral Disorders Collaborators. Global, Regional, and National Burden of Oral Conditions in 195 Countries, 1990–2017: A Systematic Analysis. J. Dent. Res. 2020, 99 (4), 362–373.

- Pitts, N.B.; Zero, D.T.; Marsh, P.D.; et al. Dental Caries. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2017, 3, 17030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsh, P.D. Microbiology of Dental Plaque Biofilms and Their Role in Oral Health and Caries. Dent. Clin. North Am. 2010, 54(3), 441–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, N.; Nyvad, B. Caries Ecology Revisited: Microbial Dynamics and the Caries Process. Caries Res. 2008, 42(6), 409–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, N.; Nyvad, B. The Role of Bacteria in the Caries Process: Ecological Perspectives. J. Dent. Res. 2011, 90(3), 294–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, L.; Zhang, L.; Yue, L.; et al. Expert Consensus on Dental Caries Management. Int. J. Oral Sci. 2022, 14(1), 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acevedo, A.; García-Quintana, A.; Frattaroli-Pericchi, A.; Feldman, S. An Extended Concept of Dental Caries and Update of Cariology Terminology. Glob. J. Med. Res. 2022, 22(J2), 1–5. Available online: https://medicalresearchjournal.org/index.php/GJMR/article/view/101754.

- Schwendicke, F.; Dörfer, C.E.; Schlattmann, P.; et al. Socioeconomic Inequality and Caries: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Dent. Res. 2015, 94(1), 10–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rai, N.K.; Tiwari, T. Parental factors influencing the development of early childhood caries in developing nations: A systematic review. Front. Public Health 2018, 6, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martignon, S.; Roncalli, A.G.; Alvarez, E.; Aránguiz, V.; Feldens, C.A.; Buzalaf, M.A.R. Risk factors for dental caries in Latin American and Caribbean countries. Braz. Oral Res. 2021, 35 (Suppl 1), e053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, M.D.; et al. Untreated early childhood caries: The role of parental eating behavior. Braz. Oral Res. 2022, 36, e010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trumbo, P.; Schlicker, S.; Yates, A.A.; Poos, M. Dietary reference intakes for energy, carbohydrate, fiber, fat, fatty acids, cholesterol, protein and amino acids. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 2002, 102, 1621–1630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phillips, M.; Masterson, E.; Sabbah, W. Association between child caries and maternal health-related behaviours. Community Dent. Health 2016, 33(2), 133–137. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Fontana, M.; Jackson, R.; Eckert, G.; et al. Identification of caries risk factors in toddlers. J. Dent. Res. 2011, 90(2), 209–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tham, R.; Bowatte, G.; Dharmage, S.C.; et al. Breastfeeding and the risk of dental caries: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Acta Paediatr. 2015, 104(467), 62–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, Y.; Tang, Q.; Tan, B.; Huang, R. Correlation between maternal smoking during pregnancy and dental caries in children: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Oral Health 2021, 2, 673449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auger, N.; Low, N.; Lee, G.; Ayoub, A.; Nicolau, B. Prenatal substance use disorders and dental caries in children. J. Dent. Res. 2020, 99(4), 395–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocha, J.S.; Arima, L.Y.; Werneck, R.I.; Moysés, S.J.; Baldani, M.H. Determinants of dental care attendance during pregnancy: A systematic review. Caries Res. 2018, 52(1–2), 139–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padung, N. First dental visit: age, reasons, oral health status, and dental treatment needs among children aged 1 month to 14 years. Int. J. Clin. Pediatr. Dent. 2022, 15(4), 394–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, J.; Alkhers, N.; Kopycka-Kedzierawski, D.T.; et al. 2019. Prenatal oral health care and early childhood caries prevention: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Caries Res. 2019, 53(4), 411–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shimpi, N.; Glurich, I.; Maybury, C.; et al. Knowledge, attitudes, behaviors of women related to pregnancy, and early childhood caries prevention: A cross-sectional pilot study. J. Prim. Care Community Health 2021, 12, 21501327211013302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butani, Y.; Weintraub, J.A.; Barker, J.C. Oral health-related cultural beliefs for four racial/ethnic groups: assessment of the literature. BMC Oral Health 2008, 8, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cascaes, M.; da Silva, N.R.J.; Fernandez, M.D.S.; Bomfim, R.A.; Vaz, J.D.S. Ultra-processed food consumption and dental caries in children and adolescents: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br. J. Nutr. 2022, 129(8), 1370–1379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gassmann, F.; de Groot, R.; Dietrich, S.; et al. Determinants and drivers of young children’s diets in Latin America and the Caribbean: Findings from a regional analysis. PLOS Glob. Public Health 2022, 2(7), e0000260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucey, S. Oral health promotion initiated during pregnancy successful in reducing early childhood caries. Evid. Based Dent. 2009, 10, 100–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.V.; Deason, J.E.; Wang, M.; et al. Association of parental oral health knowledge and self-efficacy with early childhood caries and oral health quality of life in Texas schoolchildren. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22(4), 513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiwari, T.; Wilson, A.R.; Mulvahill, M.; Rai, N.; Albino, J. Maternal factors associated with early childhood caries in urban Latino children. JDR Clin. Transl. Res. 2018, 3(1), 83–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karami, Z.; Nekuei, N.; Kazemi, A.; Paknahad, Z. Psychosocial factors related to dietary habits in women undergoing preconception care. Iran. J. Nurs. Midwifery Res. 2018, 23, 311–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buglar, M.E.; White, K.M.; Robinson, N.G. The role of self-efficacy in dental patients’ brushing and flossing: Testing an extended Health Belief Model. Patient Educ. Couns. 2010, 78(2), 269–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mazariegos, M.; Barnoya, J. Nutrition label use in a Latin American middle-income country: Guatemala. Food Nutr. Bull. 2017, 38(1), 128–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gund, M.P.; Bucher, M.; Hannig, M.; Rohrer, T.R.; Rupf, S. Oral hygiene knowledge versus behavior in children: A questionnaire-based, interview-style analysis and on-site assessment of toothbrushing practices. Clin. Exp. Dent. Res. 2022, 8, e607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callaghan, P.; Morrissey, J. Social support and health: A review. J. Adv. Nurs. 1993, 18(2), 203–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lally, C.; Maliq, N.N.; Schreiber, M.; Wilson, A.; Tiwari, T. Association of parental social support and dental caries in Hispanic children. Front. Oral Health 2023, 4, 1261111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kennedy, B.M.; Rehman, M.; Johnson, W.D.; et al. Healthcare providers versus patients' understanding of health beliefs and values. Patient Exp. J. 2017, 4(3), 29–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nahouraii, H.; Wasserman, M.; Bender, D.E.; Rozier, R.G. Social Support and Dental Utilization among Children of Latina Immigrants. J. Health Care Poor Underserved 2008, 19(2), 428–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watt, S.B.; Marshman, Z. Can Motivational Interviewing Help Prevent Dental Caries in Secondary School Children? Based Dent. 2022, 23(2), 56–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, K.R.; Doocy, S.; Reyna Ganteaume, F.; Castro, J.S.; Spiegel, P.; Beyrer, C. Venezuela’s Public Health Crisis: A Regional Emergency. Lancet 2019, 393(10177), 1254–1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruano, A.L.; Rodríguez, D.; Rossi, P.G.; Maceira, D. Understanding Inequities in Health and Health Systems in Latin America and the Caribbean: A Thematic Series. Int. J. Equity Health 2021, 20(1), 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).