1. Introduction

Wearable sensors and embedded systems have demonstrated potential to revolution- ize the way healthcare is delivered, enabling continuous monitoring of physiological parameters outside of traditional clinical settings. These technologies are becoming integral in a wide range of applications, including disease diagnosis, chronic disease management, disease prevention, fitness tracking, and personalized health interven- tions [

1,

2]. Central to this transformation is the integration of Artificial Intelligence (AI) with biosensors, which enhances the capabilities of wearable devices by enabling real-time data analysis, pattern recognition, and predictive modeling.

AI-powered biosensors are equipped with advanced algorithms that can process data directly from the sensor to provide actionable insights, detect anomalies, and predict health events in real-time [

3]. This paradigm shift has the potential to not only improve the accuracy and efficiency of health monitoring but also contribute to personalized medicine by adapting to individual needs and preferences [

4]. With the increasing availability of data and the rise of machine learning techniques, AI has become an indispensable tool in enhancing the functionality and usability of wearable sensors.

However, the application of AI in wearable sensors presents unique challenges. These include ensuring model robustness in the presence of distribution shifts, where sensor data can vary across different environments and populations, and developing personalized models that can adapt to individual users over time [

5,

6]. Further- more, the integration of edge AI and human-in-the-loop systems adds another layer of complexity, requiring seamless interaction between the device and its user to refine predictions based on user feedback.

This review explores the latest developments in AI-powered wearable biosensors and bio instrumentation, focusing on key advancements, challenges, and future direc- tions in this rapidly evolving field. We will examine how AI is being used to address issues related to model personalization, robustness, and edge computing, as well as how human feedback can further optimize system performance and user experience.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

This scoping review was conducted following the guidelines of the Preferred Report- ing Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) [

7], a framework that standardizes reporting to improve transparency and comprehensiveness in scoping reviews. Unlike systematic reviews, which focus on narrowly defined clinical questions, scoping reviews aim to map the breadth of litera- ture, identify key concepts, methodologies, and evidence gaps, and clarify definitions in emerging fields.

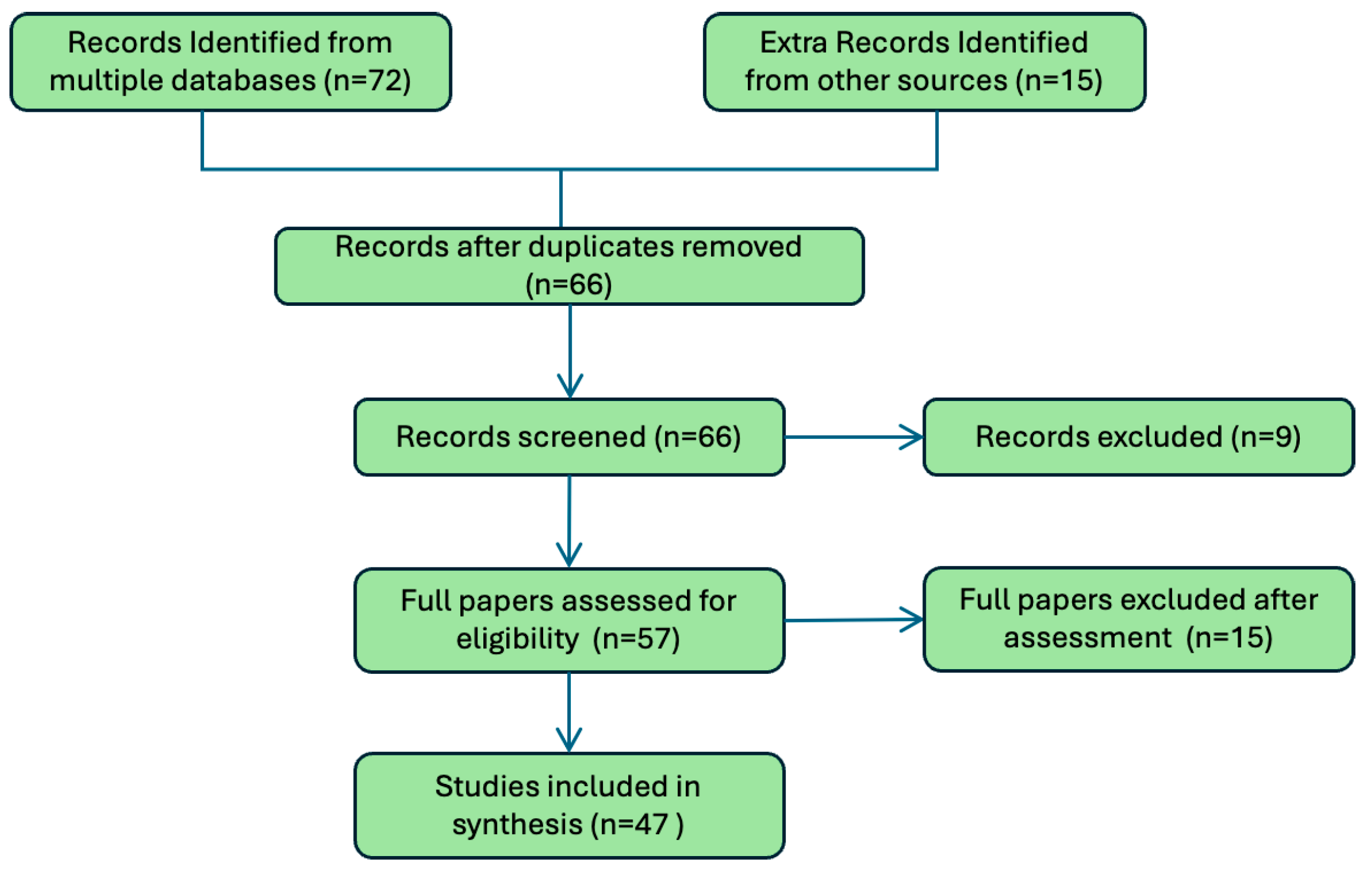

Figure 1 provides an overview of the screening process, detailing the number of records identified, screened, and included in the final synthesis. These guide- lines provided a structured approach to ensure the review’s comprehensiveness and rigor, focusing on the integration of AI-powered biosensors in wearable devices across diverse health applications.

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

For this review, we included peer-reviewed articles that explored the application of AI-powered wearable biosensors in health monitoring, diagnostics, and personalized medicine. Eligible studies were required to demonstrate empirical findings, providing quantitative or qualitative insights into the performance, efficacy, and challenges of these technologies. Articles had to be published within the last decade (January 1, 2014 to December 31, 2024) to reflect advancements in AI and wearable biosensor technologies and written in English to ensure accessibility and thorough analysis.

While the focus of the synthesis was on empirical studies, we also included selected review papers and methodological guidelines when they provided essential context, broader perspectives, or state-of-the-art summaries relevant to AI-powered biosen- sors. Commentaries, theoretical models without empirical or technical evaluation, and studies outside the timeframe remained excluded.

The timeframe of 2014 onwards was chosen as a critical starting point due to the rapid evolution of AI applications in wearables during this period, driven by advance- ments in edge computing, federated learning, and biosensor miniaturization. This window ensures a comprehensive examination of the field’s recent developments and trends.

2.3. Information Sources

Relevant studies were identified by conducting systematic searches across major elec- tronic databases, including PubMed, Scopus, IEEE Xplore, and Web of Science. The search strategy employed a combination of keywords and Boolean operators to ensure the retrieval of relevant studies. Keywords included “AI-powered biosensors,” “wear- able technology,” “health monitoring,” “real-time diagnostics,” and “personalized medicine.” Database searches were completed on November 15, 2024.

2.4. Search and Selection of Sources of Evidence

A standardized data extraction protocol was developed to ensure consistency and accuracy in capturing relevant information from the included studies. Key data points included publication details (authors, year), study location, sample size, sensor types and configurations, AI methodologies, health domains addressed, and main outcomes. Data extraction was independently conducted by two reviewers to minimize bias and improve reliability. Any discrepancies were resolved through discussion or consultation with a third reviewer.

To address the study’s objectives, the research question was framed using the PICO (Population, Intervention, Comparison, Outcome) framework [

8]. The popula- tion included users of wearable biosensors, the intervention focused on AI-powered biosensor applications, and the outcomes centered on advancements in health mon- itoring, personalization, and diagnostic accuracy. Search terms such as “AI-powered biosensors”, “wearable health monitoring”, “edge AI in wearables”, and “personalized health diagnostics” were employed to identify studies showcasing the role of biosensors in dynamic and real-time health monitoring scenarios. The review aimed to synthesize findings on how wearable biosensors combined with AI enhance user safety, opti- mize health interventions, and address issues like privacy, personalization, and model robustness.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Included Studies.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Included Studies.

| Study(Year) |

Sample Size

/Setting |

Sensor(s) |

AI Method |

Domain |

Outcome |

External

Validation |

| [9](2023) |

Review (100+ |

ECG, |

PPG, |

ML/DL |

General |

Overview of |

No |

| |

studies) |

EMG |

|

|

health |

AI wearables |

|

| [10](2024) |

4 public |

HR, |

sleep, |

LLMs |

Mental, |

HealthAlpaca |

Yes |

| |

datasets |

metabolic |

|

metabolic, |

SOTA |

|

| |

|

|

|

sleep |

|

|

| [11](20224) |

26 |

IMUs |

Transformer |

Parkinson’s |

Reduced |

Yes |

| |

|

|

|

FoG |

false posi- |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

tives |

|

| [12](2025) |

Field study in |

Sweat sensor |

Regression |

Hydration |

Real-time |

Yes |

| |

workers |

|

|

|

sodium |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

alerts |

|

3. Recent Advancements in Mobile Health

With AI systems getting more and more powerful, in the recent days, mobile health has become an integral part of our daily lives, even without always realizing it. About 21% of American adults wear smartwatches according to a 2019 consumer report (source: Statista [

13]). Recent advancements in wearables and smartwatches have significantly enhanced their capabilities, transforming them into powerful tools for health monitor- ing, fitness tracking, and beyond [

14]. Modern devices integrate cutting-edge sensors that measure vital signs such as heart rate, blood oxygen levels, and even electrocar- diograms (ECGs) with clinical-grade accuracy [

15]. Innovations in artificial intelligence and machine learning allow these wearables to provide personalized insights, detect anomalies like arrhythmias, and predict health trends over time [

9]. Additionally, wearable ecosystems now include stress monitoring, sleep quality assessment, and men- strual health tracking, catering to diverse user needs [

16,

17,

18]. With longer battery life, improved water resistance, and sleek designs, wearables are becoming indispensable in daily life. Continuous Glucose Monitors (CGMs) are revolutionizing diabetes manage- ment by offering real-time insights into glucose levels without the need for fingerstick tests. These wearable devices use tiny sensors inserted under the skin to measure inter- stitial glucose levels, enabling users to track fluctuations and trends throughout the day and night. Advanced CGMs provide predictive alerts for high or low glucose levels and integrate seamlessly with smartphones, insulin pumps, and health apps, empow- ering users to make data-driven decisions. A significant milestone in their adoption is the recent FDA approval of certain CGMs for over-the-counter sales, making them more accessible to individuals with diabetes or those looking to monitor their glucose for general health purposes [

19]. This shift highlights the growing recognition of CGMs as essential tools for proactive health monitoring, promoting broader usage beyond clinical settings.

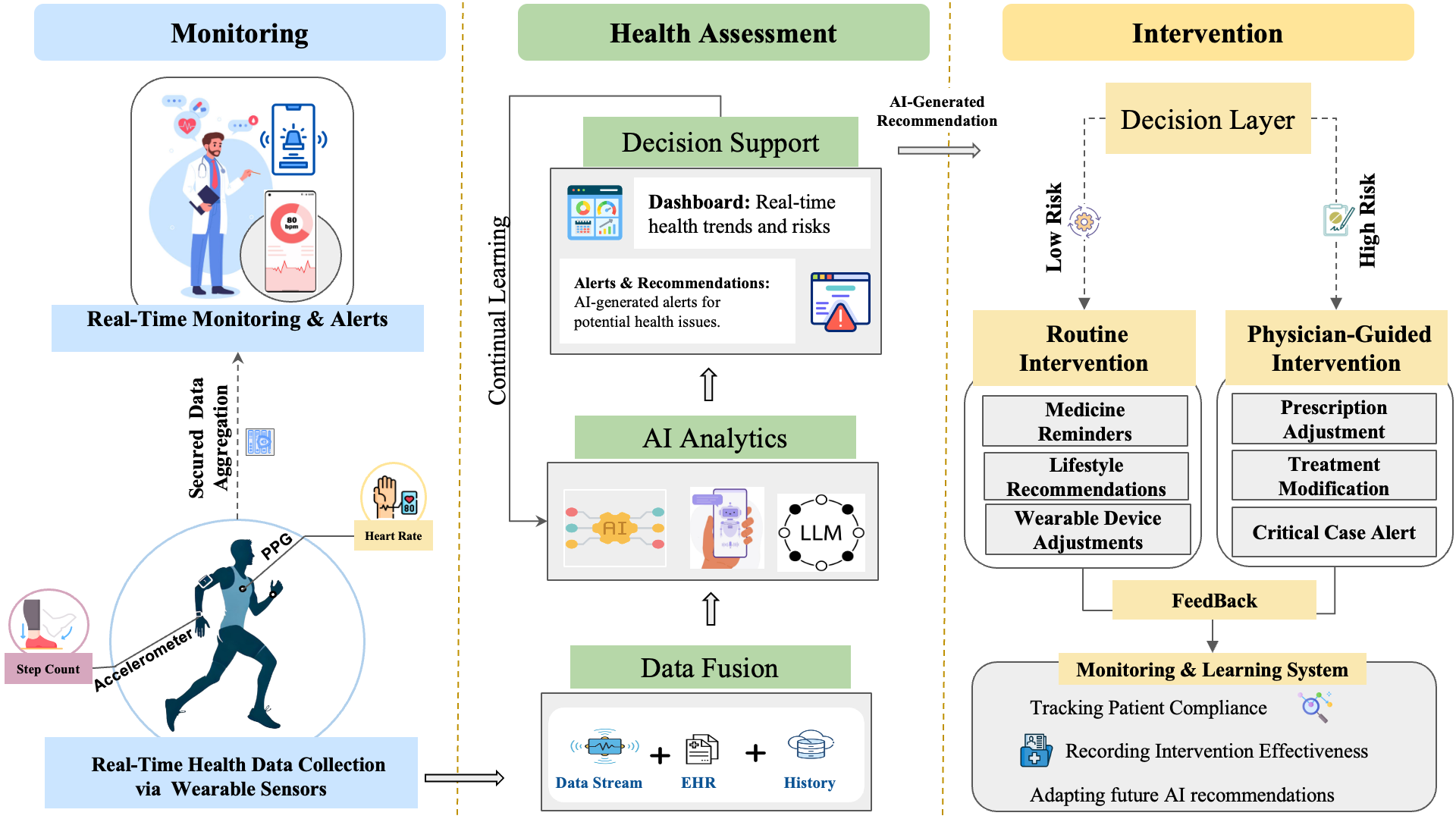

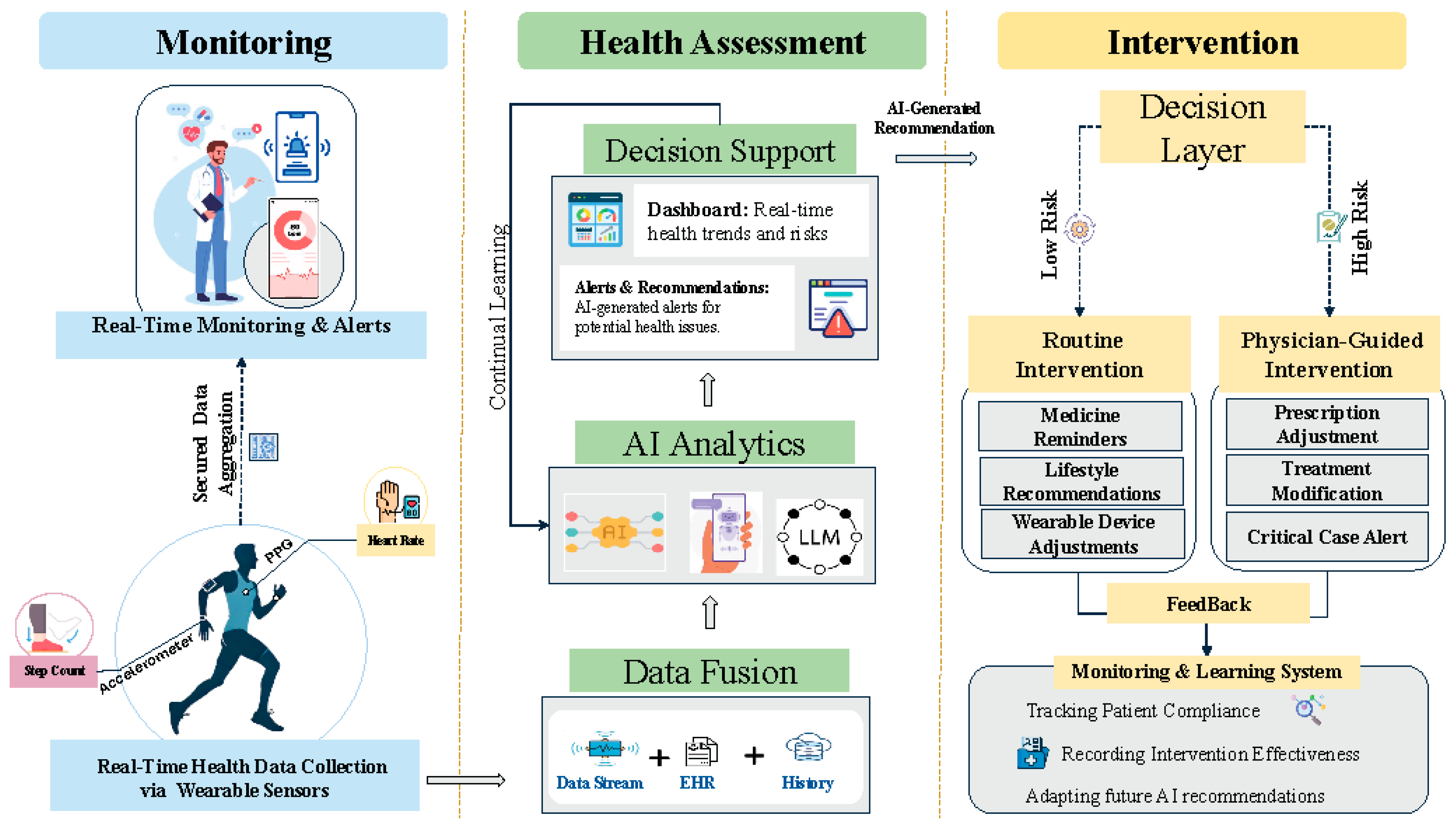

Figure 2 provides a conceptual overview of AI-powered wearable biosensors and their role in healthcare. The framework is structured into three pillars: monitoring, health assessment, and intervention. The monitoring pillar captures real-time physiologi- cal and behavioral data through wearable and implantable biosensors, which is then processed using AI-driven algorithms. The health assessment pillar enables pattern recognition, anomaly detection, and predictive modeling, incorporating techniques like federated learning, transfer learning, and continual learning to enhance model robust- ness. Finally, the intervention pillar translates AI-driven insights into personalized health recommendations, clinical decision support, and adaptive interventions. This modular approach illustrates how AI, human-in-the-loop systems, and digital twin technologies work together to optimize personalized medicine and real-time health monitoring (

Figure 2).

4. Applications of Biosensors

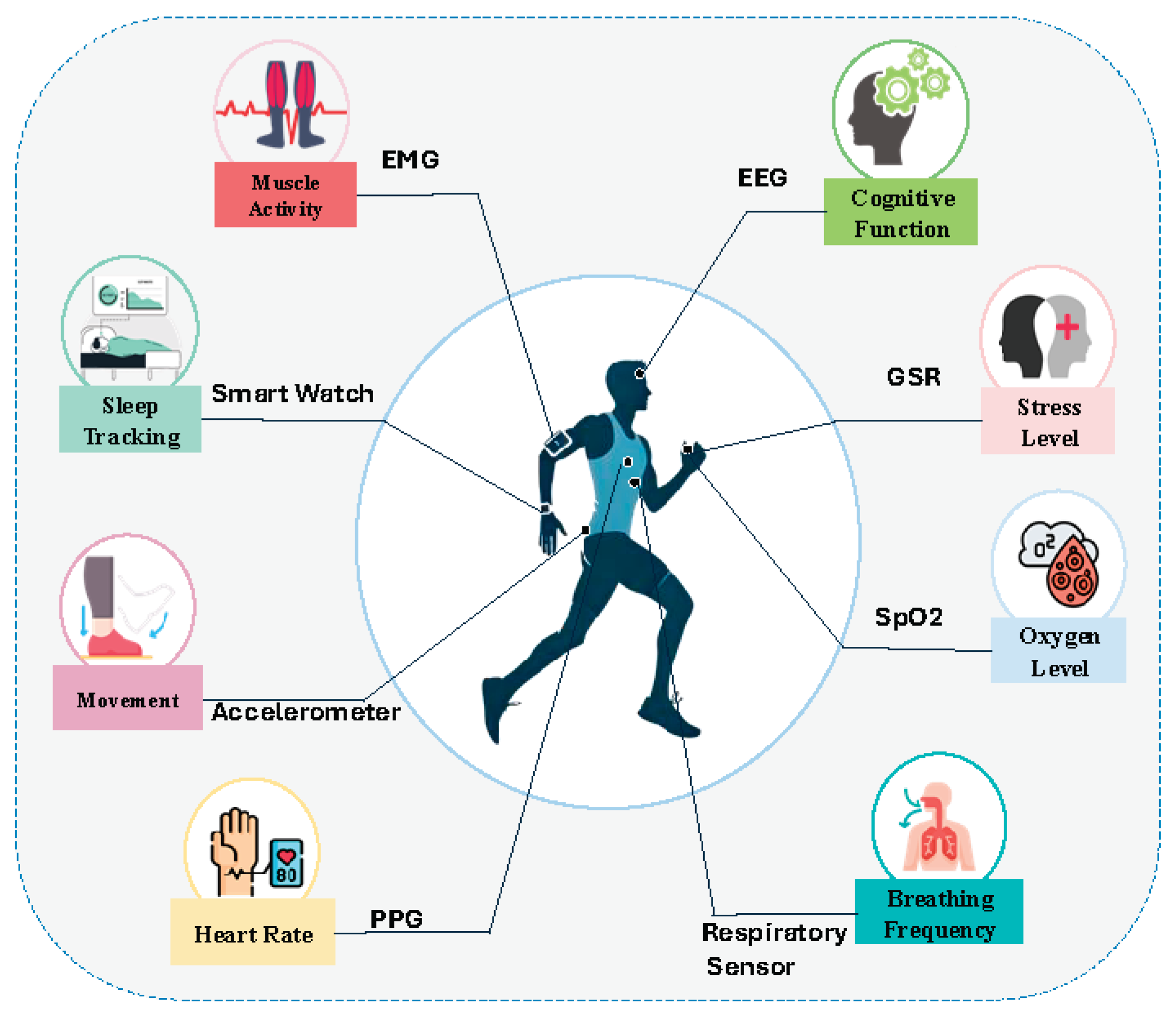

Wearable biosensors have become essential tools for continuous health monitoring, enabling the measurement of multiple physiological and behavioral parameters.

Figure 3 illustratesthese applications, while

Table 2 provides a categorized overview of health conditions where biosensors are most widely applied. These include physiological and behavioral health monitoring, gait and motor function, neurodegenerative diseases, metabolic and hydration health, and maternal/neonatal care.

4.1. Metabolic and Neonatal Health

In recent years biosensors have become transformative tools in metabolic health, where they are extensively used to manage conditions such as diabetes and obesity. CGMs provide real-time insights into glucose fluctuations, enabling better glycemic control and early detection of irregularities. Recent work shows that LLM-based counter- factual generation (e.g., GPT-4o-mini) can enhance explainability and robustness in metabolic health prediction tasks [

42,

43]. Beyond diabetes, biosensors are being used to monitor metabolic biomarkers like lactate and ketones, aiding in personalized diet and exercise regimens [

9].

In neonatal health, biosensors are deployed to monitor vital parameters such as oxygen saturation, heart rate, and respiration in real-time, providing critical sup- port in neonatal intensive care units (NICUs). These devices can alert clinicians to potential adverse events, such as hypoxia or bradycardia, ensuring timely interven- tions and better outcomes for premature or at-risk infants [

17]. Integrating AI with biosensors further enhances their utility, enabling predictive analytics and personalized recommendations in these domains.

4.2. Cardiovascular Health

In cardiovascular health, biosensors play a pivotal role in monitoring heart rate, blood pressure, and other hemodynamic parameters, aiding in the early detection of arrhyth- mias, hypertension, and heart failure. Devices such as smartwatches, ECG patches, and chest straps enable continuous and non-invasive monitoring, empowering individuals to manage their cardiovascular health proactively. AI-driven algorithms strengthen these applications by detecting anomalies and predicting adverse events, thereby empower- ing individuals to manage their cardiovascular health more proactively [

15,

23].

4.3. Neurological and Cognitive Health

Biosensors are also transforming neurological and cognitive health monitoring, espe- cially in chronic disorders such as Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s diseases. In Parkinson’s disease, wearable sensors can capture motor symptoms such as tremors, gait abnor- malities, and freezing of gait [

44], supporting both early diagnosis and therapy adjustments [

11,

26]. In Alzheimer’s care, biosensors are used to monitor sleep patterns, cognitive function, and physiological stress markers, offering insights into disease pro- gression and the effectiveness of interventions.

Table 3 complements this by outlining the main methodologies and corresponding biomarkers that enable these applications.

5. Challenges with AI-Powered Biosensors

AI-powered biosensors, widely used for health monitoring and diagnostics, often face challenges related to data privacy, personalization, and model robustness. Traditional centralized learning methods require aggregating user data in a single location, rais- ing significant privacy and security concerns. Federated learning is a decentralized approach in which models are trained locally on users’ devices and only model updates (not raw data) are shared. This addresses this by enabling biosensors to collabora- tively train AI models locally on their devices, ensuring sensitive health data remains private. Edge-AI- the deployment of AI algorithms directly on local devices such as smartphones, wearables, and IoT sensors-transforms how data is processed and uti- lized. By performing computations locally on the device rather than relying on cloud servers, Edge-AI minimizes latency, enhances data privacy, and reduces the band- width needed for data transmission. This is particularly beneficial for time-sensitive applications like health monitoring with biosensors, autonomous vehicles, and real- time industrial automation [

45]. Edge-AI systems leverage specialized hardware such as AI accelerators and optimized algorithms to ensure efficient performance within the resource constraints of edge devices. Moreover, the technology supports offline func- tionality, enabling critical operations even in areas with poor connectivity. As Edge-AI continues to evolve, advancements in energy-efficient neural networks and federated learning further enhance its potential, making it a cornerstone for next-generation AI applications across diverse industries [

44].

Another common issue is the heterogeneity of biosensor devices, such as differ- ences in sensor quality, user behaviors, and environmental conditions. Transfer learning can mitigate these issues by leveraging pre-trained models to adapt quickly to new devices or scenarios, reducing the need for extensive retraining. Moreover, biosensors frequently deal with noisy, incomplete, or imbalanced datasets, which can impair AI performance, especially in detecting rare but critical health conditions [

25,

38,

39].

Continual learning and human-in-the-loop systems are pivotal in addressing chal- lenges associated with adaptability and interpretability. Biosensors operate in dynamic environments where users’ physiological patterns may change due to aging, illness, or lifestyle adjustments, requiring models to adapt continuously without catastrophic forgetting of prior knowledge. Continual learning enables this by allowing mod- els to incrementally learn from new data while retaining previous knowledge [

27]. Human-in-the-loop systems further enhance the reliability of AI-powered biosensors by incorporating user feedback and expert annotations. These systems help correct errors, refine predictions, and improve user trust in the technology. By combining federated learning, continual learning, transfer learning, and human-in-the-loop approaches, AI- powered biosensors can overcome critical challenges, paving the way for more robust, personalized, and secure health monitoring solutions.

Despite advancements in AI-powered biosensors, fundamental differences between biological systems and wearable electronics pose additional challenges. Biology and electronics differ significantly in their materials, functional principles, fabrication tech- niques, and operational environments, creating a complex interface for integration. For instance, biological systems are inherently flexible, soft, and dynamic, whereas wearable electronics are often rigid, brittle, and optimized for static conditions. These differences, summarized in

Table 4, highlight the need for innovative design approaches to bridge the gap between biological and electronic systems effectively.

In addition to technical hurdles, regulatory and reimbursement barriers remain major obstacles. The regulatory landscape lacks unified standards for evaluating algo- rithmic fairness, safety, and efficacy, and agencies such as the FDA require rigorous clinical evidence and explainability before approval [

46]. On the reimbursement side, fragmented payer policies and the absence of standardized codes create financial uncer- tainty and limit adoption, as insurers often demand costly, longitudinal evidence of improved outcomes before coverage. [

47]

6. Future of AI-Powered Biosensors

The future of AI-powered biosensors lies in their integration with cutting-edge technologies like Large Language Models (LLMs), digital twins, and counterfactual explanations, enabling more intelligent and personalized healthcare solutions. One emerging area is precise diet and hydration recommendations, where biosensors can track fluid intake and optimize hydration levels in real-time. Hydration plays a vital role in both physical performance and cognitive health, yet current wearable technolo- gies lack the ability to monitor both fluid type and volume simultaneously [

12,

31]. LLMs can serve as a critical component of the biosensor ecosystem by processing and contextualizing vast amounts of health data. They can generate personalized health insights, offer recommendations based on user-specific patterns, and act as conver- sational agents for patients and clinicians. For instance, LLMs can synthesize data from wearables and biosensors to identify correlations between lifestyle factors and health metrics, guiding users in optimizing their behaviors [30? ]. Moreover, their nat- ural language capabilities enable users to interact intuitively with health systems, ask questions about their data, and receive comprehensible explanations, bridging the gap between complex AI outputs and human understanding [

10,

48].

Digital twins and counterfactual explanations promise to revolutionize how biosen- sor data is analyzed and utilized. A digital twin is a computational model or virtual replica of an individual’s physiological systems that continuously integrates real-time data from wearable sensors with historical and contextual health information. Unlike static models, digital twins are dynamic and adaptive, allowing them to simulate the effects of interventions such as medication adjustments, lifestyle changes, or exercise routines, and predict how these changes would impact health outcomes over time. Biosensors will feed real-time data into these digital twins, ensuring that the simu- lations are dynamic and accurately reflect the user’s current health status [

49,

50]. Meanwhile, counterfactual explanations will enhance trust and transparency in AI- powered biosensors by illustrating alternative scenarios. For example, they can explain to users how changes in diet, exercise, or medication would affect health outcomes, offering actionable insights. Together, these innovations will empower individuals and healthcare providers with predictive, explainable, and actionable intelligence, advanc- ing precision medicine and preventative care. The convergence of these technologies ensures a future where AI-powered biosensors are not just tools for monitoring but also partners in health decision-making.

7. Conclusion

In summary, advancements in AI-powered technologies like wearables, CGMs, and biosensors are revolutionizing healthcare by enabling personalized, real-time monitor- ing and decision-making. The growing accessibility of devices, such as over-the-counter CGMs, underscores their expanding role beyond clinical settings, empowering individ- uals to take control of their health. However, these innovations come with challenges such as data privacy, device heterogeneity, and the need for robust, adaptable AI models. Techniques like federated learning, continual learning, transfer learning, and human-in-the-loop systems address these issues by enhancing privacy, adaptability, and reliability. Similarly, the rise of Edge-AI is driving efficiency and responsiveness by processing data locally on devices, ensuring real-time functionality even in constrained environments. Together, these advancements are shaping a future where AI-powered health technologies are more accessible, secure, and effective, paving the way for a smarter and healthier society.

Special and Outstanding Interest — Papers of special interest are highlighted with one asterisk (*) and those of outstanding interest with two asterisks (**). Annotated references were selected from the past two years to emphasize studies of particular novelty, methodological rigor, or significant impact in the field of AI-powered wearable biosensors.

References

- Alinia P, Sah RK, McDonell M, Pendry P, Parent S, Ghasemzadeh H, et al. Asso- ciations between physiological signals captured using wearable sensors and self- reported outcomes among adults in alcohol use disorder recovery: development and usability study. JMIR Formative Research. 2021;5(7):e27891. [CrossRef]

- Zhang Y, Hu Y, Jiang N, Yetisen AK. Wearable artificial intelligence biosensor networks. Biosensors and Bioelectronics. 2023;219:114825. [CrossRef]

- Arefeen A, Akbari A, Mirzadeh SI, Jafari R, Shirazi BA, Ghasemzadeh H. Inter- beat interval estimation with tiramisu model: a novel approach with reduced error. ACM Transactions on Computing for Healthcare. 2024;5(1):1–19. [CrossRef]

- Katsoulakis E, Wang Q, Wu H, Shahriyari L, Fletcher R, Liu J, et al. Digital twins for health: a scoping review. NPJ Digital Medicine. 2024;7(1):77. [CrossRef]

- Wilson G, Doppa JR, Cook DJ. CALDA: Improving Multi-Source Time Series Domain Adaptation With Contrastive Adversarial Learning. IEEE Trans Pat- tern Anal Mach Intell. 2023 Dec;45(12):14208–14221. [CrossRef]

- Yu H, Sano A. Semi-supervised learning for wearable-based momentary stress detection in the wild. Proceedings of the ACM on Interactive, Mobile, Wearable and Ubiquitous Technologies. 2023;7(2):1–23. [CrossRef]

- Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. bmj. 2021;372. [CrossRef]

- Miller SA, Forrest JL. Enhancing your practice through evidence-based decision making: PICO, learning how to ask good questions. Journal of Evidence Based Dental Practice. 2001;1(2):136–141.

- *Shajari S, Kuruvinashetti K, Komeili A, Sundararaj U. The emergence of AI-based wearable sensors for digital health technology: a review. Sensors. 2023;23(23):9498. This review provides a comprehensive overview of AI-powered wearable sensors, emphasizing their role in personalized health monitoring, disease diagnosis, and real-time data acquisition. It highlights key challenges such as calibration, data accuracy, and security risks, while underscoring their transformative potential for preventive healthcare.

- *Kim Y, Xu X, McDuff D, Breazeal C, Park HW. Health-llm: Large lan- guage models for health prediction via wearable sensor data. arXiv preprint arXiv:240106866. 2024; This study introduces Health-LLM, evaluating 12 LLMs across 10 consumer health tasks. The fine-tuned HealthAlpaca model outperformed GPT-4 and Gemini-Pro in most tasks, demonstrating the potential of LLMs for personalized health predictions while raising important concerns about privacy and clinical validity.

- **Koltermann K, Clapham J, Blackwell G, Jung W, Burnet EN, Gao Y, et al. Gait-Guard: Turn-aware Freezing of Gait Detection for Non-intrusive Intervention Systems. In: 2024 IEEE/ACM Conference on Connected Health: Applications, Systems and Engineering Technologies (CHASE). IEEE; 2024. p. 61–72. This paper presents Gait-Guard, a wearable closed-loop system for real-time detection and intervention of freezing of gait in Parkinson’s disease. The work was recognized with the Best Paper Award at CHASE 2024, highlighting its clinical significance in improving patient mobility.

- **Spinelli JC, Suleski BJ, Wright DE, Grow JL, Fagans GR, Buckley MJ, et al. Wearable microfluidic biosensors with haptic feedback for continuous monitoring of hydration biomarkers in workers. npj Digital Medicine. 2025;8(1):76. This work introduces a multimodal wearable biosensor that combines electrochemical and biophysical sensing with haptic feedback to monitor sweat loss and sodium levels. Field trials in extreme environments demonstrate its utility for real-time hydration management in occupational health.

- Statista Research Department.: Wearables in the U.S. - Statistics & Facts. Accessed: September 13, 2025. https://www.statista.com/topics/12075/ wearables-in-the-us/#topicOverview.

- Huhn S, Axt M, Gunga HC, Maggioni MA, Munga S, Obor D, et al. The impact of wearable technologies in health research: scoping review. JMIR mHealth and uHealth. 2022;10(1):e34384. [CrossRef]

- Odeh VA, Chen Y, Wang W, Ding X. Recent Advances in the Wearable Devices for Monitoring and Management of Heart Failure. Reviews in Cardiovascular Medicine. 2024;25(10):386. [CrossRef]

- Sah RK, Cleveland MJ, Ghasemzadeh H. Stress Monitoring in Free-Living Environments. IEEE Journal of Biomedical and Health Informatics. 2023;. [CrossRef]

- Lyzwinski L, Elgendi M, Menon C. Innovative approaches to menstruation and fertility tracking using wearable reproductive health technology: systematic review. Journal of Medical Internet Research. 2024;26:e45139. [CrossRef]

- Neupane S, Saha M, Ali N, Hnat T, Samiei SA, Nandugudi A, et al. Momentary Stressor Logging and Reflective Visualizations: Implications for Stress Manage- ment with Wearables. In: Proceedings of the CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems; 2024. p. 1–19.

- FDA.: FDA Clears First Over-the-Counter Continuous Glucose Monitor. Accessed: 2024. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Avail- able from: https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/ fda-clears-first-over-counter-continuous-glucose-monitor.

- Azghan RR, Glodosky NC, Sah RK, Cuttler C, McLaughlin R, Cleveland MJ, et al. CUDLE: Learning Under Label Scarcity to Detect Cannabis Use in Uncontrolled Environments using Wearables. IEEE Sensors Journal. 2025;p. 1–1. [CrossRef]

- Holder R, Sah RK, Cleveland M, Ghasemzadeh H. Comparing the predictability of sensor modalities to detect stress from wearable sensor data. In: 2022 IEEE 19th Annual Consumer Communications & Networking Conference (CCNC). IEEE; 2022. p. 557–562.

- Hosseini S, Gottumukkala R, Katragadda S, Bhupatiraju RT, Ashkar Z, Borst CW, et al. A multimodal sensor dataset for continuous stress detection of nurses in a hospital. Scientific Data. 2022;9(1):255. [CrossRef]

- Hughes A, Shandhi MMH, Master H, Dunn J, Brittain E. Wearable devices in cardiovascular medicine. Circulation research. 2023;132(5):652–670. [CrossRef]

- Vos G, Trinh K, Sarnyai Z, Azghadi MR. Generalizable machine learning for stress monitoring from wearable devices: A systematic literature review. International Journal of Medical Informatics. 2023;173:105026. [CrossRef]

- Soumma SB, Mangipudi K, Peterson D, Mehta S, Ghasemzadeh H.: Self- Supervised Learning and Opportunistic Inference for Continuous Monitoring of Freezing of Gait in Parkinson’s Disease. Available from: https://arxiv.org/abs/2410.21326.

- Pardoel S, AlAkhras A, Jafari E, Kofman J, Lemaire ED, Nantel J. Real- Time Freezing of Gait Prediction and Detection in Parkinson’s Disease. Sensors. 2024;24(24):8211. [CrossRef]

- Jha S, Schiemer M, Zambonelli F, Ye J. Continual learning in sensor-based human activity recognition: An empirical benchmark analysis. Information Sciences. 2021;575:1–21. [CrossRef]

- Shi B, Tay A, Au WL, Tan DM, Chia NS, Yen SC. Detection of freezing of gait using convolutional neural networks and data from lower limb motion sensors. IEEE Transactions on Biomedical Engineering. 2022;69(7):2256–2267. [CrossRef]

- Mamun A, Arefeen A, Racette SB, Sears DD, Whisner CM, Buman MP, et al. LLM-Powered Prediction of Hyperglycemia and Discovery of Behavioral Treat- ment Pathways from Wearables and Diet. Sensors. 2025;25(17). [CrossRef]

- Healey E, Tan ALM, Flint KL, Ruiz JL, Kohane I. A case study on using a large language model to analyze continuous glucose monitoring data. Scientific Reports. 2025;15(1):1143. [CrossRef]

- Pedram M, Mirzadeh SI, Rokni SA, Fallahzadeh R, Woodbridge DMK, Lee SI, et al. LIDS: mobile system to monitor type and volume of liquid intake. IEEE Sensors Journal. 2021;21(18):20750–20763. [CrossRef]

- Stecher C, Pfisterer B, Harden SM, Epstein D, Hirschmann JM, Wunsch K, et al. Assessing the pragmatic nature of Mobile health interventions promoting physi- cal activity: systematic review and meta-analysis. JMIR mHealth and uHealth. 2023;11:e43162. [CrossRef]

- *Hirten RP, Danieletto M, Sanchez-Mayor M, Whang JK, Lee KW, Landell K, et al. Physiological Data Collected from Wearable Devices Identify and Predict Inflammatory Bowel Disease Flares. Gastroenterology. 2025; This study shows that physiological data from consumer wearables can identify and predict IBD flares weeks in advance by tracking changes in metrics like heart rate and activity. It highlights a promising, non-invasive approach for continuous disease monitoring and personalized management. [CrossRef]

- Cohen R, Fernie G, Roshan Fekr A. Monitoring fluid intake by commercially available smart water bottles. Scientific Reports. 2022;12(1):4402. [CrossRef]

- Pruksanusak N, Chainarong N, Boripan S, Geater A. Comparison of the predic- tive ability for perinatal acidemia in neonates between the NICHD 3-tier FHR system combined with clinical risk factors and the fetal reserve index. Plos one. 2022;17(10):e0276451. [CrossRef]

- Mamun A, Devoe LD, Evans MI, Britt DW, Klein-Seetharaman J, Ghasemzadeh H. Use of What-if Scenarios to Help Explain Artificial Intelligence Models for Neonatal Health. arXiv preprint arXiv:241009635. 2024;.

- Evans MI, Britt DW, Evans SM, Devoe LD. Changing perspectives of electronic fetal monitoring. Reproductive Sciences. 2022;29(6):1874–1894. [CrossRef]

- Fallahzadeh R, Ashari ZE, Alinia P, Ghasemzadeh H. Personalized activity recognition using partially available target data. IEEE Transactions on Mobile Computing. 2021;22(1):374–388. [CrossRef]

- Mamun A, Mirzadeh SI, Ghasemzadeh H. Designing deep neural networks robust to sensor failure in mobile health environments. In: 2022 44th Annual Inter- national Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine & Biology Society (EMBC). IEEE; 2022. p. 2442–2446.

- Pedram M, Sah RK, Ghasemzadeh H. Efficient Sensing and Classification for Extended Battery Life. In: Activity Recognition and Prediction for Smart IoT Environments. Springer; 2024. p. 111–140.

- Sah RK, Ghasemzadeh H. Adversarial Transferability in Embedded Sensor Sys- tems: An Activity Recognition Perspective. ACM Transactions on Embedded Computing Systems. 2024;23(2):1–31.

- Soumma SB, Arefeen A, Carpenter SM, Hingle M, Ghasemzadeh H.: SenseCF: LLM-Prompted Counterfactuals for Intervention and Sensor Data Augmentation. Available from: https://arxiv.org/abs/2507.05541.

- Arefeen A, Soumma SB, Ghasemzadeh H.: RealAC: A Domain-Agnostic Frame- work for Realistic and Actionable Counterfactual Explanations. Available from: https://arxiv.org/abs/2508.10455.

- Soumma SB, Alam SMR, Rahman R, Mahi UN, Mamun A, Mostafavi SM, et al.: Freezing of Gait Detection Using Gramian Angular Fields and Federated Learning from Wearable Sensors. Available from: https://arxiv.org/abs/2411.11764.

- Chawla N, Dalal S. Edge AI with Wearable IoT: A Review on Leveraging Edge Intelligence in Wearables for Smart Healthcare. Green Internet of Things for Smart Cities. 2021;p. 205–231.

- Pawnikar V, Patel M. Biosensors in wearable medical devices: Regulatory framework and compliance across US, EU, and Indian markets. In: Annales Pharmaceutiques Franc¸aises. Elsevier; 2025. . [CrossRef]

- Mathias R, McCulloch P, Chalkidou A, Gilbert S. Digital health technologies need regulation and reimbursement that enable flexible interactions and groupings. NPJ Digital Medicine. 2024;7(1):148. [CrossRef]

- *Clusmann J, Kolbinger FR, Muti HS, Carrero ZI, Eckardt JN, Laleh NG, et al. The future landscape of large language models in medicine. Communications medicine. 2023;3(1):141. This review systematically examines the potentials and risks of LLMs in medicine, emphasizing their applications in clinical care, research, and education. It raises concerns about misinformation, bias, and accountability, while advocating for open-source development and stronger ethical frameworks. [CrossRef]

- Cappon G, Facchinetti A. Digital Twins in Type 1 Diabetes: A Systematic Review. Journal of Diabetes Science and Technology. 2024;p. 19322968241262112. [CrossRef]

- **Cappon G, Sparacino G, Facchinetti A. AGATA: a toolbox for automated glucose data analysis [published online ahead of print January 5, 2023]. J Diabetes Sci Technol; AGATA is a comprehensive, open-source toolbox for automated analysis of continuous glucose monitoring (CGM) data, offering robust preprocessing, visualization, and standardized metric calculation. Its versatility and ease of use make it a valuable resource for both clinical and research applications, enabling reproducible and efficient glucose data analysis. I selected AGATA for its exemplary contribution to advancing diabetes technology research.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).