Submitted:

30 July 2025

Posted:

31 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

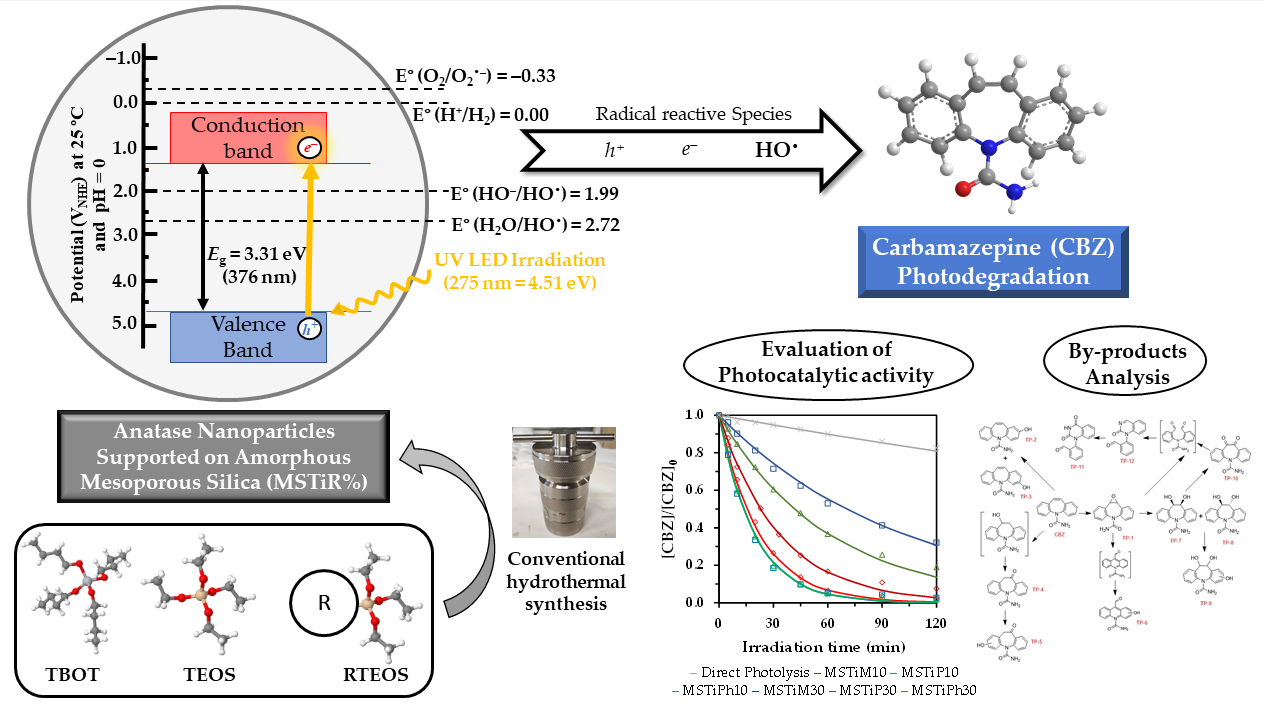

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Reactives

2.2. Synthesis of the Anatase Supported on Mesoporous Silica (MSTiR%)

2.3. Characterization Techniques

2.3. Photodegradation Experiments

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Characterization Analysis of the MSTiR% Materials

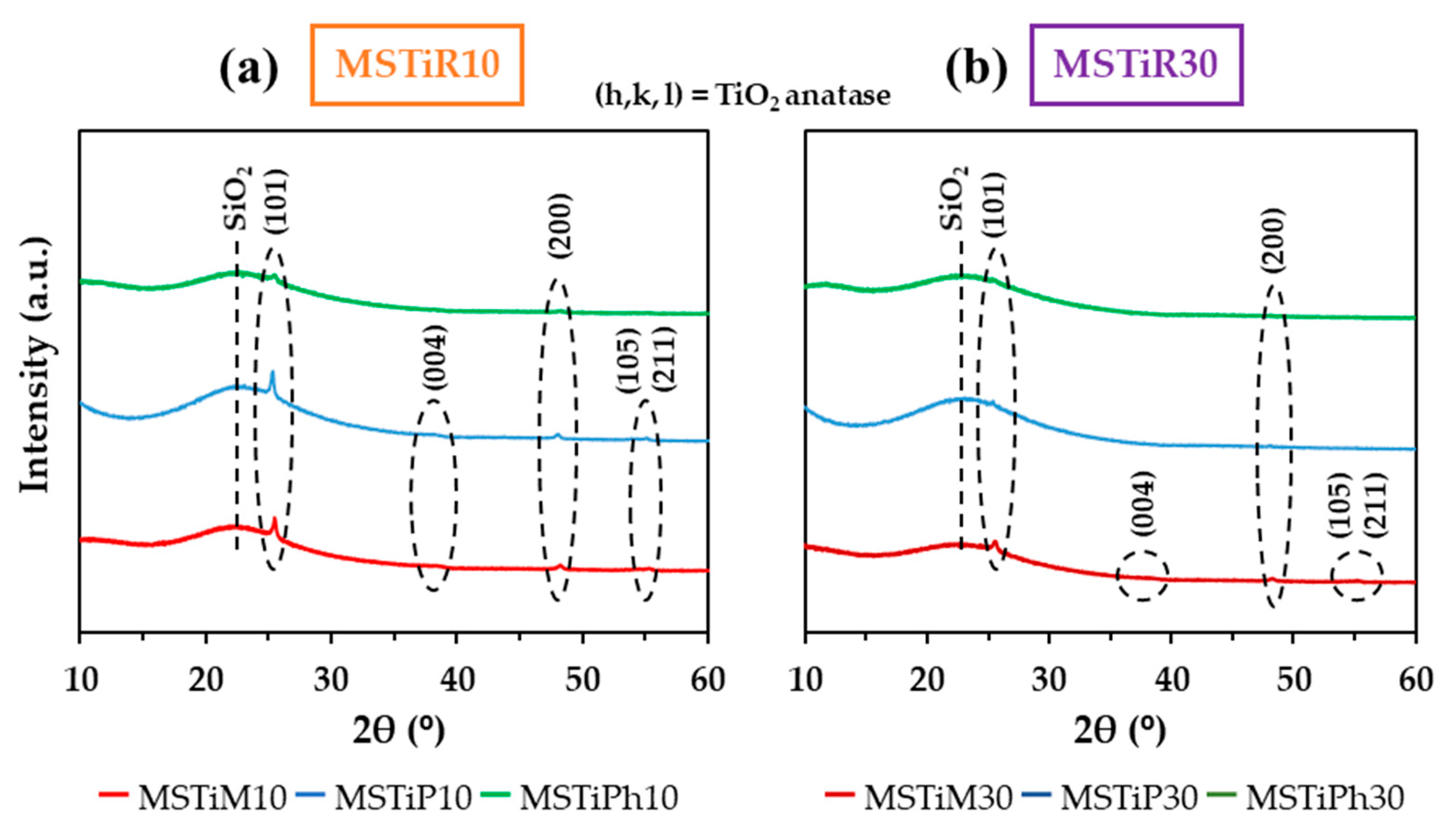

3.1.1. X-Ray Diffraction (XRD)

| MSTiR% | (h, k, l) | 2θ | d(h, k, l)a | D(101)b | Degree of Crystallinityc | |

| (°) | (nm) | (nm) | (%) | |||

| MSTiM10 | (101) | 25.48 | 0.350 | 8.39 | 13.19 | |

| (004) | 38.45 | 0.234 | ||||

| (200) | 48.23 | 0.189 | ||||

| (105) | 54.46 | 0.168 | ||||

| (211) | 55.27 | 0.166 | ||||

| MSTiP10 | (101) | 25.37 | 0.351 | 9.06 | 11.39 | |

| (004) | 38.15 | 0.236 | ||||

| (200) | 48.05 | 0.189 | ||||

| (105) | 54.39 | 0.169 | ||||

| (211) | 55.08 | 0.167 | ||||

| MSTiPh10 | (101) | 25.47 | 0.350 | 8.95 | 9.15 | |

| (200) | 48.28 | 0.189 | ||||

| MSTiM30 | (101) | 25.53 | 0.349 | 8.77 | 11.08 | |

| (004) | 38.15 | 0.236 | ||||

| (200) | 48.24 | 0.189 | ||||

| (105) | 54.52 | 0.168 | ||||

| (211) | 55.18 | 0.166 | ||||

| MSTiP30 | (101) | 25.39 | 0.351 | 9.06 | 8.14 | |

| (200) | 48.05 | 0.189 | ||||

| MSTiPh30 | (101) | 25.34 | 0.351 | 10.67 | 6.90 | |

| (200) | 48.13 | 0.189 |

3.1.2. Fourier-Transformed Infrared Spectroscopy (FT-IR)

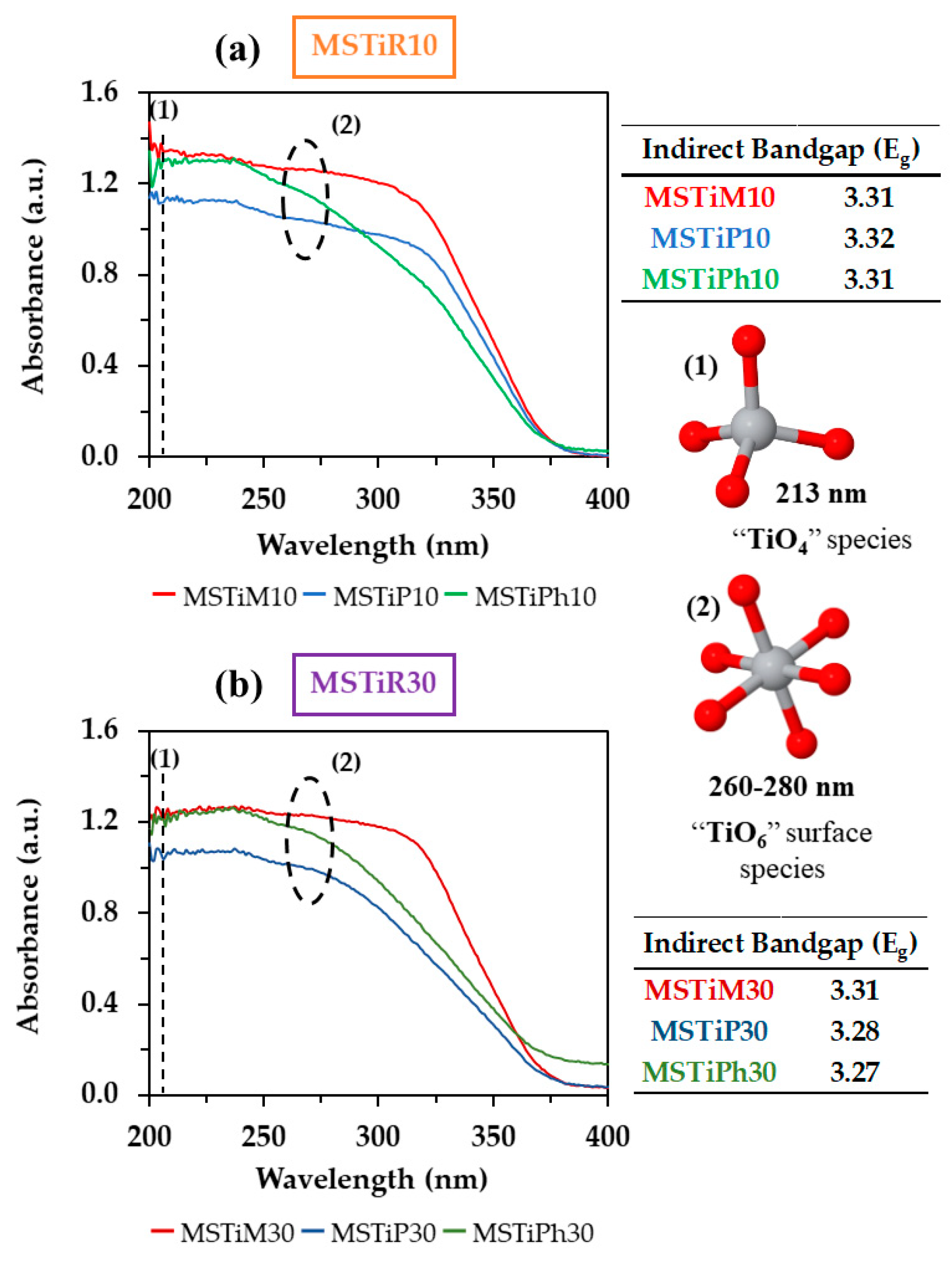

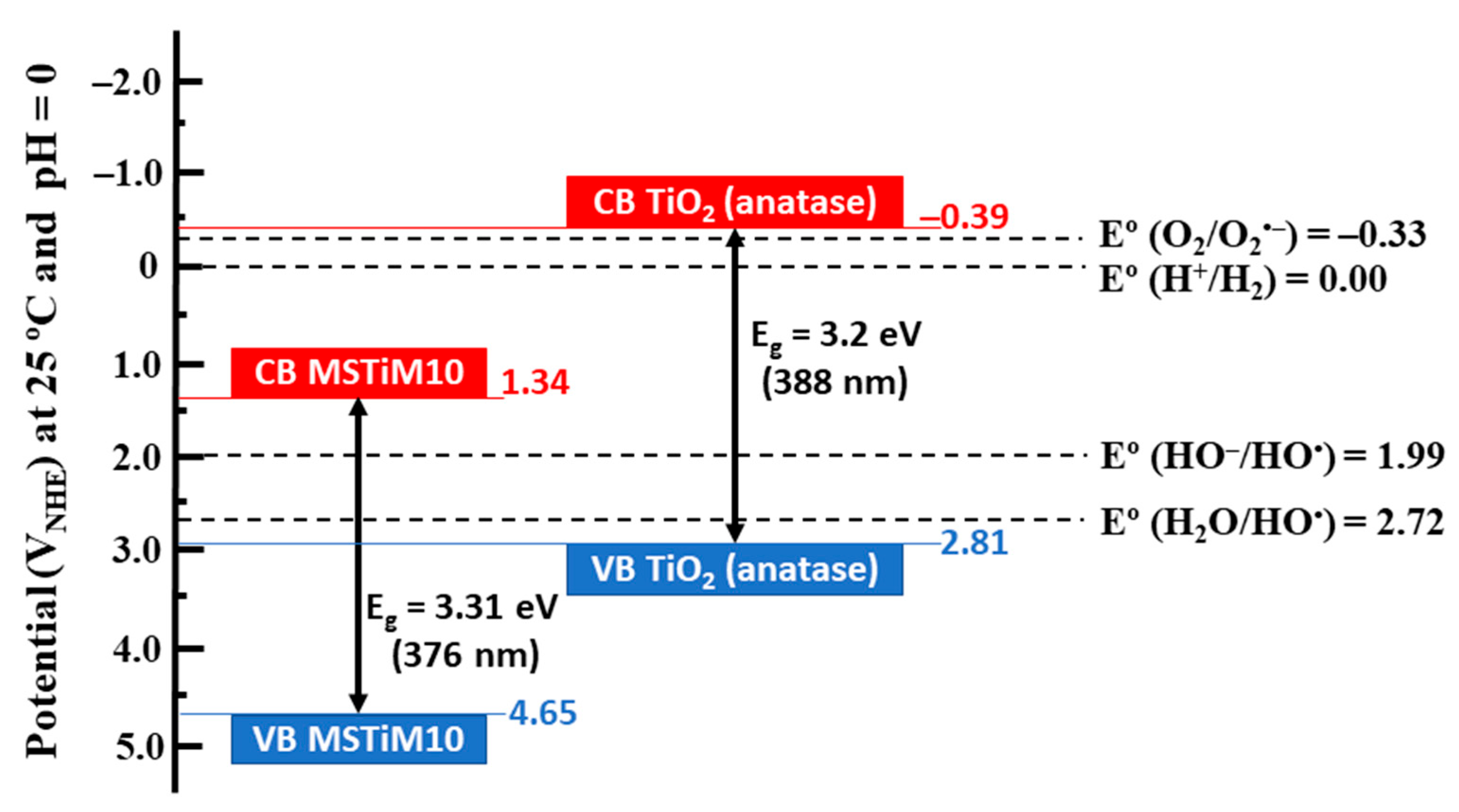

3.1.3. UV-Vis Diffuse Reflectance (DR) and X-Ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS)

| MSTiR% | C1s | O1s | Si2p | Ti2p | ||||

| Atomic (%) | ||||||||

| MSTiM10 | 6.01 | 65.54 | 28.27 | 0.18 | ||||

| MSTiP10 | 6.82 | 65.24 | 27.71 | 0.23 | ||||

| MSTiPh10 | 6.04 | 66.17 | 27.48 | 0.31 | ||||

| MSTiM30 | 9.09 | 63.32 | 27.45 | 0.14 | ||||

| MSTiP30 | 7.17 | 65.20 | 27.53 | 0.10 | ||||

| MSTiPh30 | 7.16 | 65.17 | 27.49 | 0.18 | ||||

| MSTiR% |

Bandgap Energy (Eg) |

Valence Band maximum Edge Potential (EVBM) | Conduction Band Minimum Edge Potential (ECBM) | |||

| (eV) | (VVacuum) | (VNHE) | (VVacuum) | (VNHE) | ||

| MSTiM10 | 3.31 | –9.09 | 4.65 | –5.78 | 1.34 | |

| MSTiP10 | 3.32 | –8.88 | 4.44 | –5.56 | 1.12 | |

| MSTiPh10 | 3.31 | –9.05 | 4.61 | –5.74 | 1.30 | |

| MSTiM30 | 3.31 | –9.05 | 4.61 | –5.74 | 1.30 | |

| MSTiP30 | 3.28 | –9.28 | 4.84 | –6.00 | 1.56 | |

| MSTiPh30 | 3.27 | –9.32 | 4.88 | –6.05 | 1.61 | |

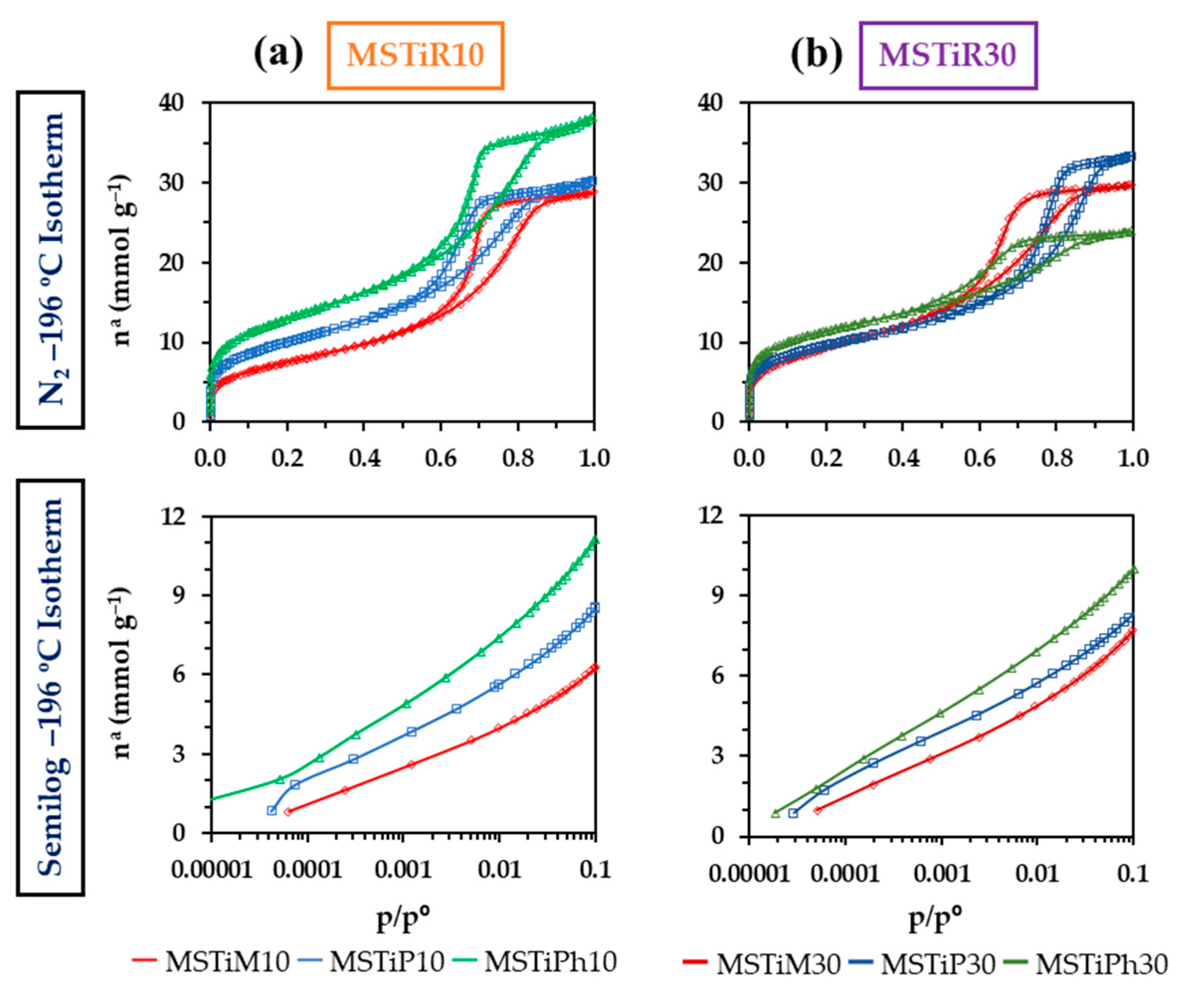

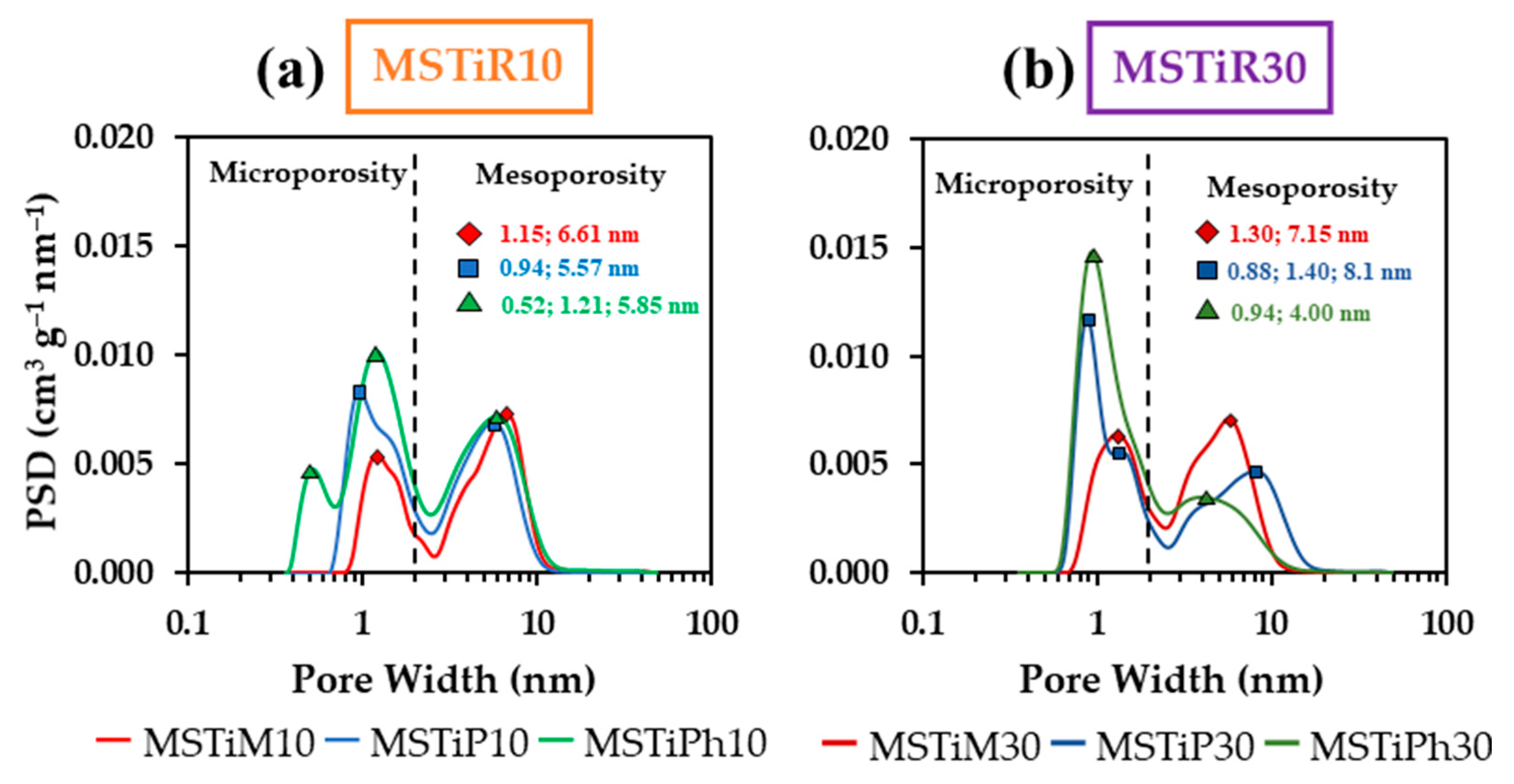

3.1.4. N2 Isotherms (–196 °C)

| Material | aBET | aDR | Vmicroa | Vmesob | Vmacroc | Vtotald | BJH APSe | Ecf | |||

| (m2 g–1) | (cm3 g–1) | (nm) | (KJ mol–1) | ||||||||

| MSTiM10 | 608 | 668 | 0.24 | 0.60 | 0.14 | 0.98 | 6.83 | 12.19 | |||

| MSTiP10 | 810 | 902 | 0.32 | 0.59 | 0.11 | 1.02 | 6.12 | 12.88 | |||

| MSTiPh10 | 1047 | 1191 | 0.42 | 0.67 | 0.20 | 1.28 | 6.31 | 12.57 | |||

| MSTiM30 | 753 | 837 | 0.30 | 0.60 | 0.12 | 1.02 | 6.02 | 11.83 | |||

| MSTiP30 | 774 | 879 | 0.31 | 0.47 | 0.35 | 1.13 | 7.91 | 13.28 | |||

| MSTiPh30 | 921 | 1062 | 0.38 | 0.34 | 0.10 | 0.82 | 5.26 | 13.35 | |||

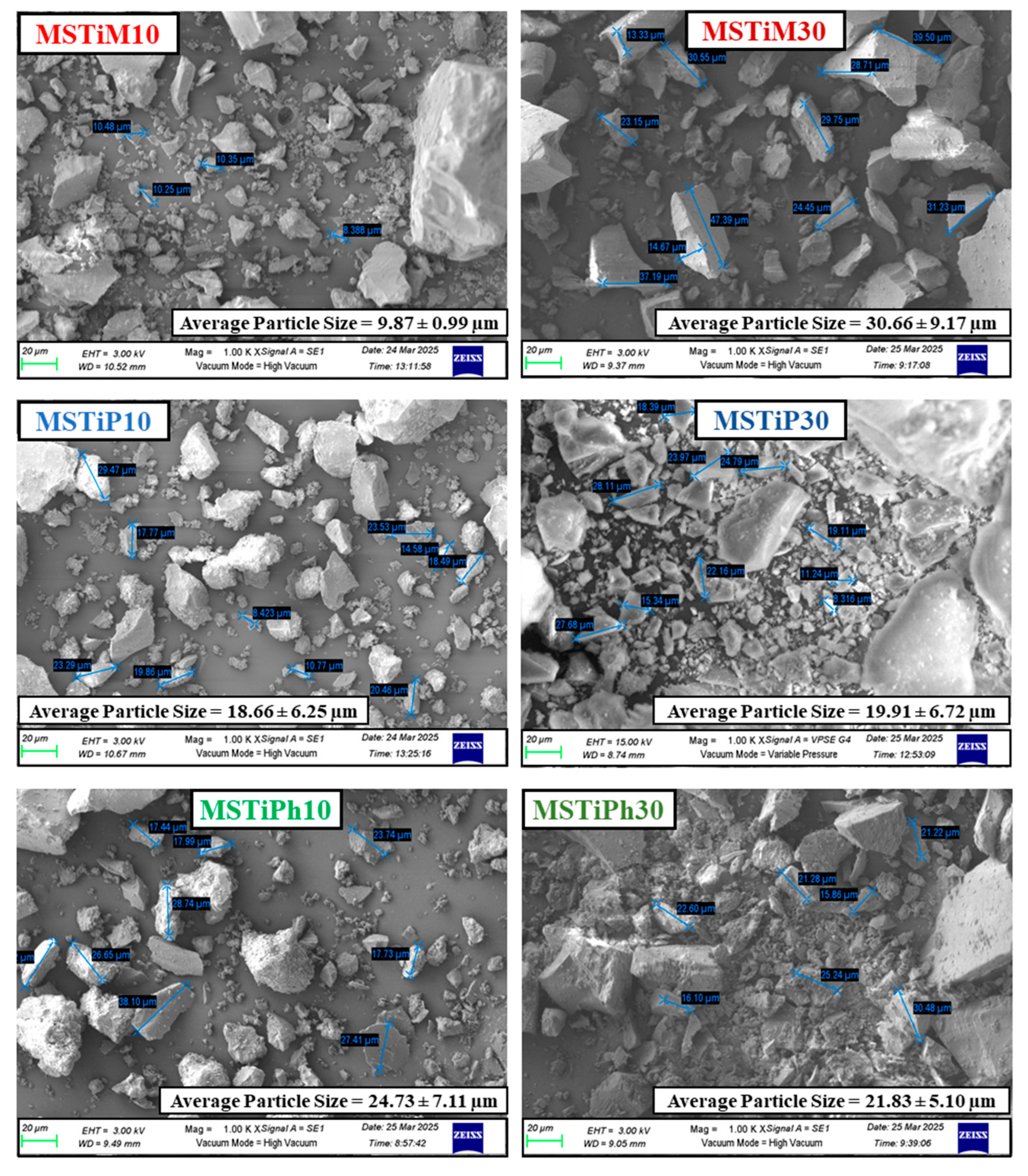

3.1.5. Field-Emission Scanning Electron Microscopy (FE-SEM)

| MSTiR% | O | Si | Ti | ||||||

| Weight | Atomic | Weight | Atomic | Weight | Atomic | ||||

| (%) | (%) | (%) | |||||||

| MSTiM10 | 59.33 | 72.26 | 39.00 | 27.06 | 1.67 | 0.68 | |||

| MSTiP10 | 64.20 | 76.19 | 34.55 | 23.31 | 1.25 | 0.49 | |||

| MSTiPh10 | 61.52 | 74.01 | 37.02 | 25.40 | 1.47 | 0.59 | |||

| MSTiM30 | 62.73 | 74.91 | 36.33 | 24.72 | 0.94 | 0.37 | |||

| MSTiP30 | 60.01 | 72.64 | 39.25 | 27.07 | 0.73 | 0.29 | |||

| MSTiPh30 | 61.70 | 74.07 | 37.08 | 25.44 | 1.22 | 0.49 | |||

3.2. Photocatalytic Degradation of CBZ in the Presence of MSTiR%

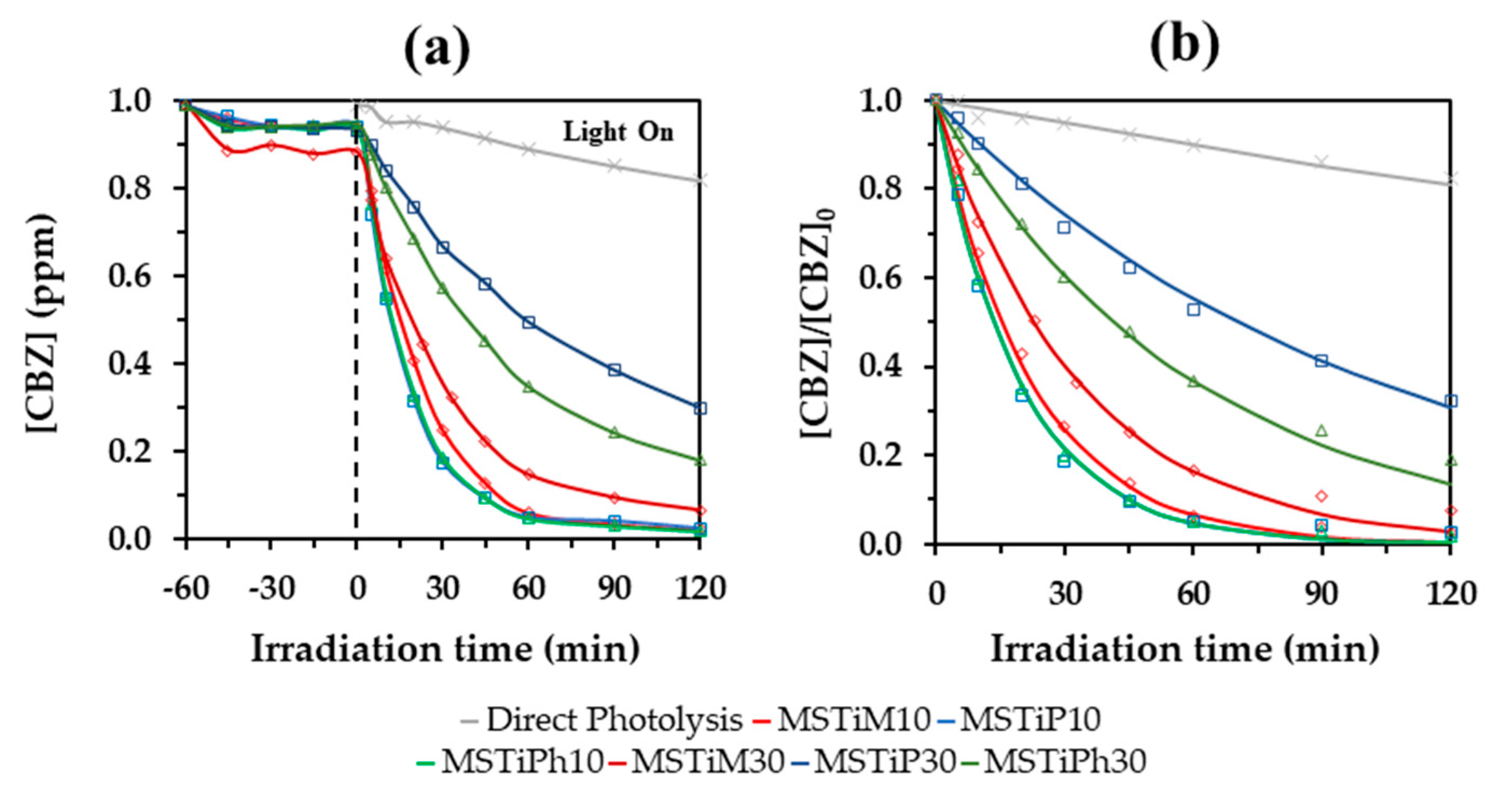

3.2.1. Evaluation of the Photocatalytic Activity of the MSTiR% Materials

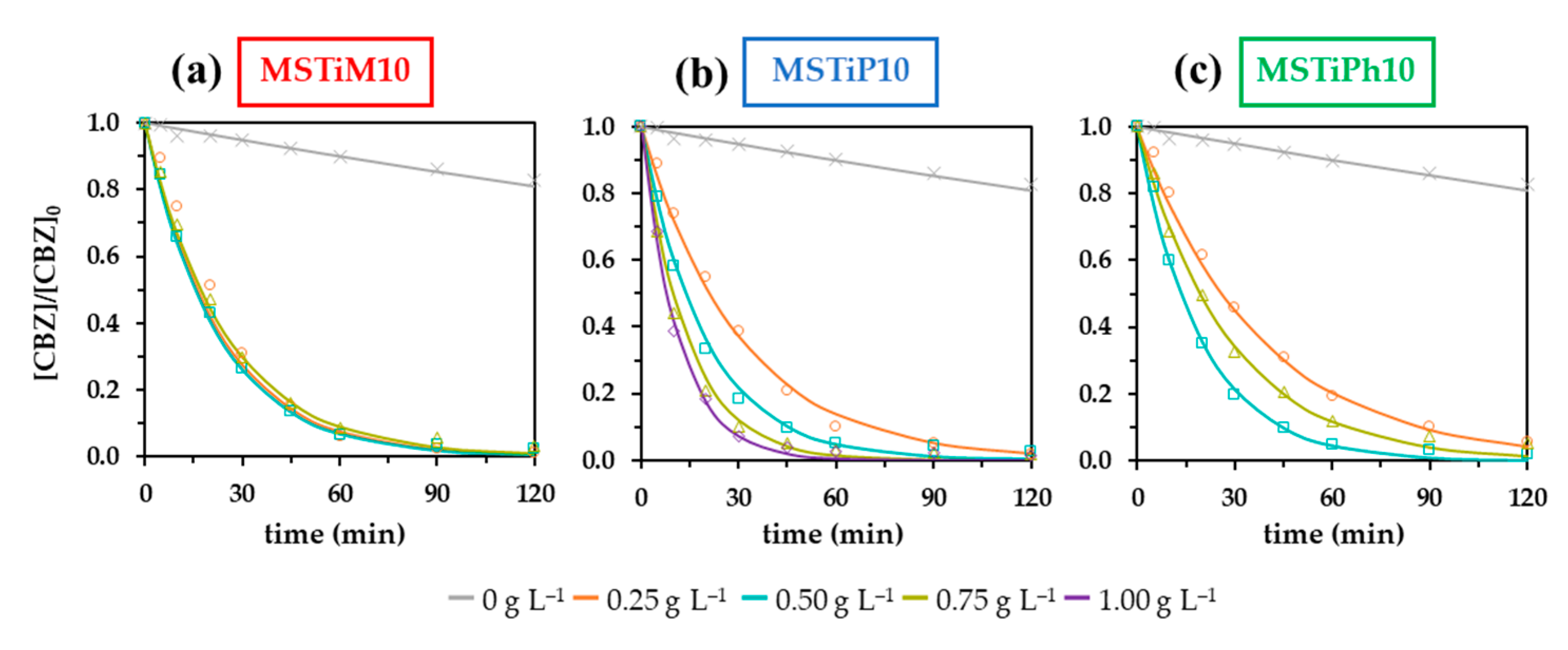

3.2.2. Influence of the MSTiR% Dose

| MSTiR% | MSTiR% | CBZ Removal | First-Order Kinetic Adjustment | |||||

| Dose | Adsorbeda | Degradedb | Total | kappc | t1/2d | R2 | ||

| (g L–1) | (%) | (min–1) | (min) | |||||

| None | 0.00 | - | 17.36 | 17.36 | 0.0018 | 391.28 | 0.9958 | |

| MSTiM10 | 0.25 | 1.78 | 96.92 | 98.70 | 0.0430 | 16.12 | 0.9812 | |

| 0.50 | 5.00 | 92.58 | 97.58 | 0.0448 | 15.46 | 0.9984 | ||

| 0.75 | 6.47 | 90.19 | 96.66 | 0.0404 | 17.14 | 0.9985 | ||

| MSTiP10 | 0.25 | 0.00 | 97.92 | 97.92 | 0.0331 | 20.92 | 0.9912 | |

| 0.50 | 4.91 | 92.50 | 97.41 | 0.0512 | 13.54 | 0.9939 | ||

| 0.75 | 6.49 | 91.70 | 98.19 | 0.0707 | 9.80 | 0.9844 | ||

| 1.00 | 7.73 | 90.85 | 98.58 | 0.0877 | 7.90 | 0.9972 | ||

| MSTiPh10 | 0.25 | 1.78 | 92.63 | 94.41 | 0.0265 | 26.11 | 0.9948 | |

| 0.50 | 5.70 | 92.48 | 98.18 | 0.0511 | 13.57 | 0.9980 | ||

| 0.75 | 8.32 | 86.40 | 94.72 | 0.0356 | 19.48 | 0.9988 | ||

| MSTiM30 | 0.50 | 10.97 | 81.41 | 92.38 | 0.0302 | 22.95 | 0.9993 | |

| MSTiP30 | 0.50 | 5.85 | 61.78 | 67.63 | 0.0099 | 70.32 | 0.9947 | |

| MSTiPh30 | 0.50 | 4.24 | 76.51 | 80.75 | 0.0166 | 35.53 | 0.9997 | |

| a–Percentage of CBZ adsorbed after 60 min at dark; b–Percentage of CBZ degraded after 120 min of irradiation; c–Apparent First-order kinetic constant; d–Half-life calculated from kapp. | ||||||||

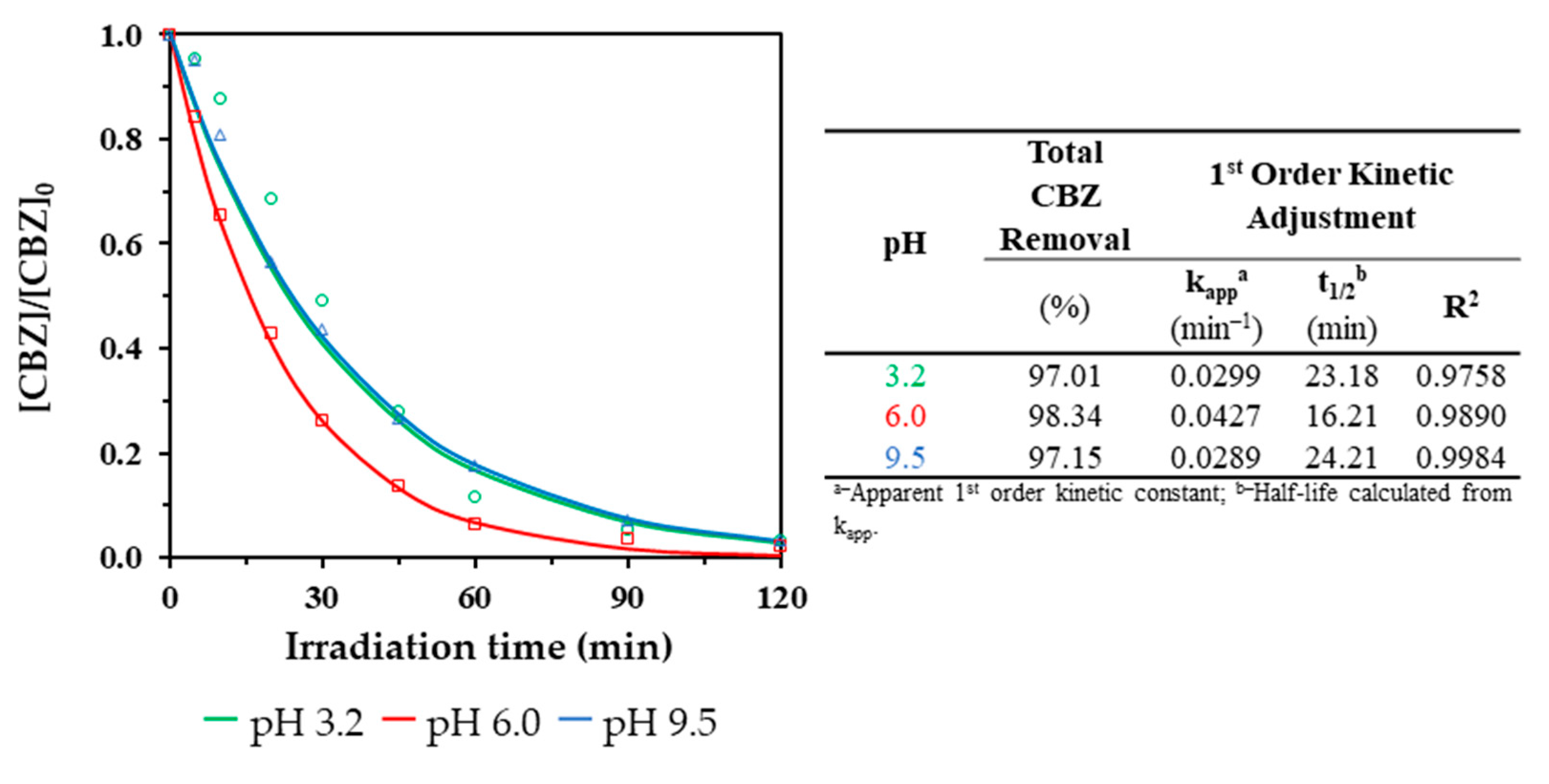

3.2.3. Influence of the Initial pH

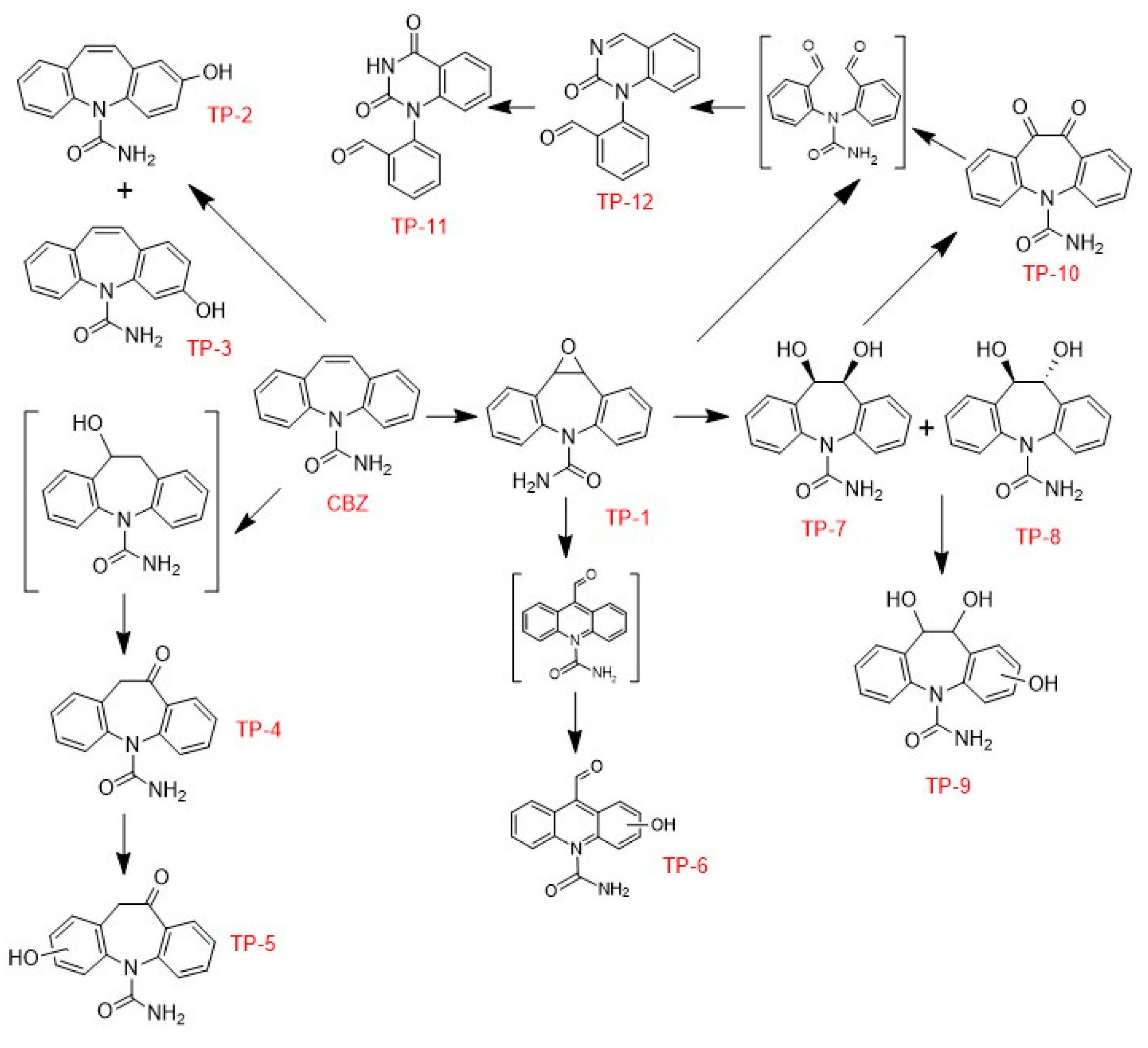

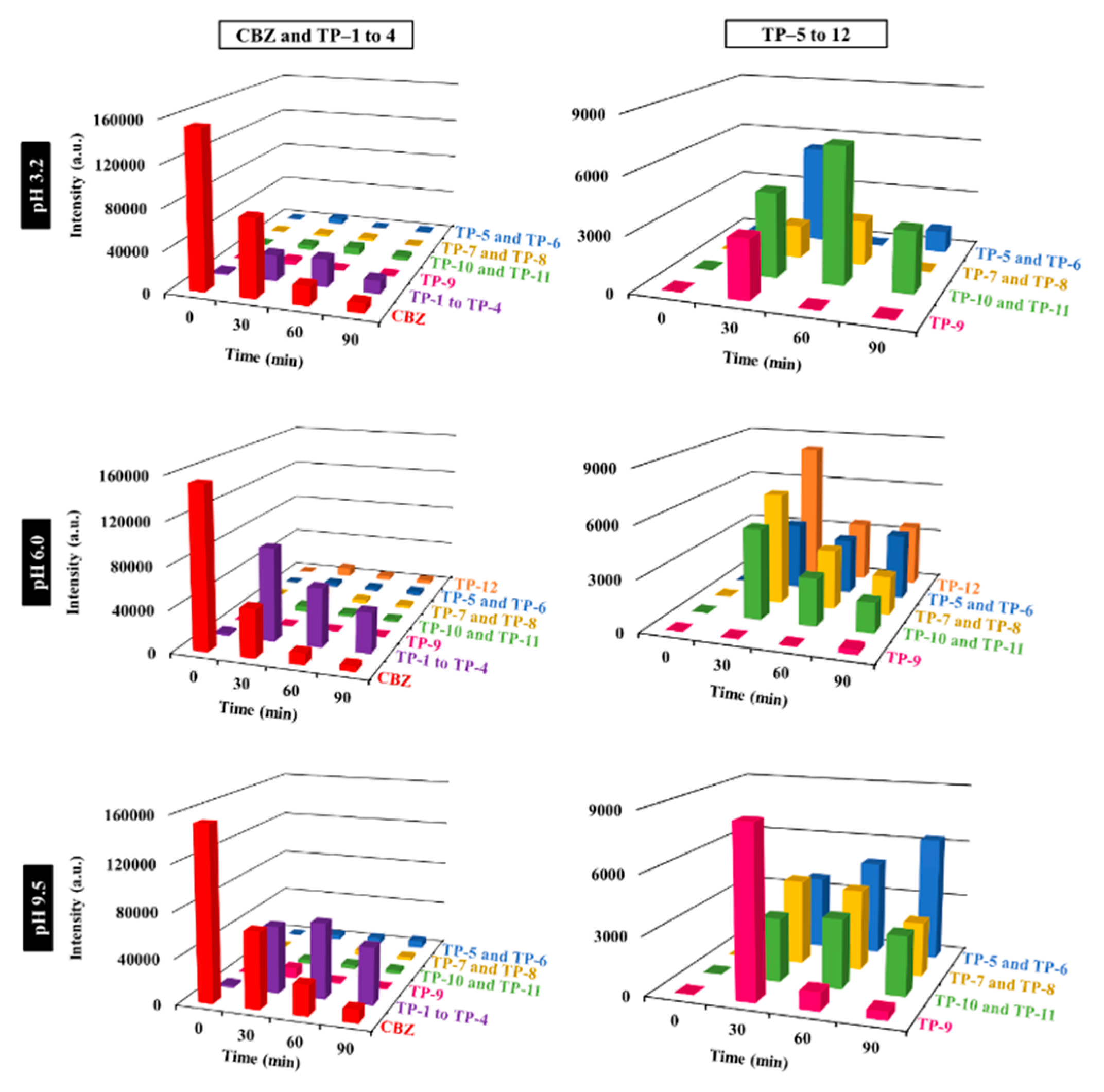

3.2.4. Identification and Evolution of CBZ and Its Transformation Products (TPs)

| Compound | Name | Molecular formula | m/z |

tr (min) |

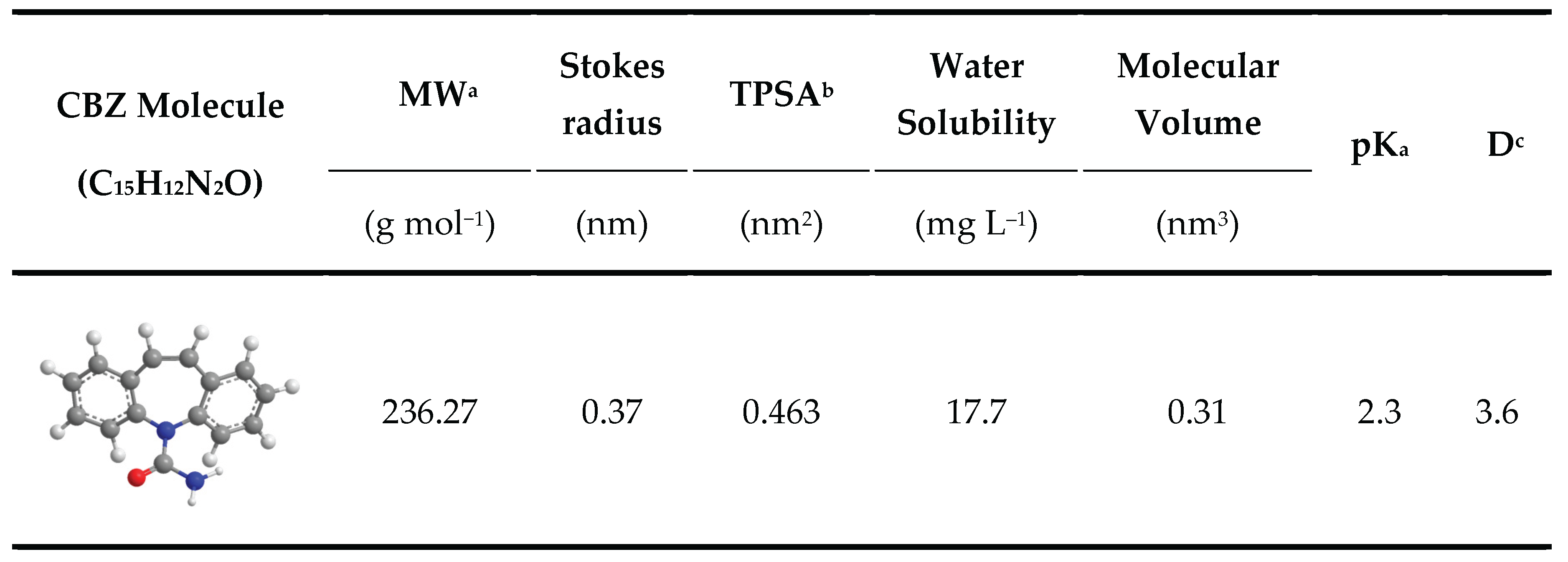

| CBZ | Carbamazepine | C15H12N2O | 237.1021 | 4.47 |

| TP-1 | CBZ-10,11-epoxide | C15H12N2O2 | 253.0969 – 253.0972 | 3.58 – 4.08 |

| TP-2 | 2-hydroxy-CBZ | |||

| TP-3 | 3-hydroxy-CBZ | |||

| TP-4 | Oxcarbazepine | |||

| TP-5 | Hydroxylation of oxcarbazepine | C15H12N2O3 | 269.0922 – 269.0924 | 3.36 – 3.80 |

| TP-6 | Hydroxylated derivative of N-amino-carbonylacridine-9-carboxaldehyde | |||

| TP-7 | Derivatives 10,11-dihydrodiol-CBZ | C15H14N2O3 | 271.1077 – 271.1079 | 3.03 – 3.60 |

| TP-8 | ||||

| TP-9 | Trihydroxylated form of CBZ | C15H14N2O4 | 287.1027 | 3.66 |

| TP-10 | 11-keto oxcarbazepine | C15H10N2O3 | 267.0765 - 2670766 | 3.64 – 3.74 |

| TP-11 | Fragmentation of 1-(2-benzaldehyde)-(1H,3H)-quinazoline-2,4-dione | |||

| TP-12 | 1-(2-benzaldehyde)-4-hydro-(1H,3H)-quinazoline-2-one | C15H10N2O2 | 251.0821 | 2.29 |

3.2.5. Comparison with Other CBZ Photocatalysts

| Catalyst | Experimental conditions | Irradiation Source | Performance | Ref. | ||||

| Bi4O5Br2 | 1 g L–1 of catalyst 10 mg L–1 of CBZ 50 mL reaction |

Visible light, 420 nm single-wavelength irradiation |

90% of CBZ was degraded after 120 min of irradiation (Kapp = 0.0196 min–1) |

Mao et al. 2021 [39] |

||||

| g-C3N4/TiO2 | 0.1–3 g L–1 of catalyst 1–40 mg L–1 of CBZ 1–20 mM PMS pH = 3–11 |

24 W UV light Philips PL-L lamp (λMax = 285 nm) |

~95% of 1 mg L–1 of CBZ was degraded after 60 min using 1 g L–1 of catalyst (Kapp = 0.0558 min–1) |

Meng et al. 2022 [40] |

||||

| Mesoporous Fe3O4 modified Al-doped ZnO (Al-ZnO/Fe) | 1 g L–1 of catalyst Hospital wastewater spiked with 1 mg L–1 of CBZ |

15 W UV-A lamps. Light Intensity: 32 W m–2 | 5:1 Al-ZnO/Fe achieved a 99% removal of CBZ after 60 min of irradiation with a rate of 0.076 min−1 | Majumder et al. 2022 [41] | ||||

| Cu/TiO2/Ti3C2 composite (0.5 wt% Cu) |

2 g L–1 of catalyst 14 mg L–1 of CBZ 25 cm3 glass reactor |

Simulated Solar Light irradiation, 300 W Xenon Lamp | Complete CBZ degradation was achieved after 60 min of irradiation, and in 20 min when 0.5 mM of Peroxymonosulfate were added | Grzegórska et al. 2023 [42] |

||||

| Pd-modified-TiO2 and Ce-modified ZnO |

1 g L–1 of catalyst 15 mg L–1 of CBZ 80 mL reaction |

Visible light. (λMax = 575 nm) |

80%, 53%, 20% and 9% of CBZ was removed by ZnO, Ce-modified-ZnO, TiO2 and Pd-modified-TiO2, respectively, after 3 h of irradiation. Ce-modified-ZnO released less Zn+2 than ZnO. | Rossi et al. 2023 [43] |

||||

| Cu2O; WO3; and Cu2O/WO3 | 0.4 g L–1 of catalyst 20 mg L–1 of CBZ 100 mL reaction |

Visible light, 50 W LED bulb | After Cu2O, WO3 and Cu2O/WO3 removed 41.14 %; 30.36 %; and 94% of CBZ in 60 min with Kapp = 0.0199; 0.0138; and 0.0572 min–1, respectively. | Mandyal et al. 2024 [44] |

||||

| TiO2 and Y–TiO2 (0.25–1 wt%) hydrothermally and micro-wave assisted synthesised |

1 g L–1 of catalyst 20 mg L–1 of CBZ |

UV-LED (λ = 395 nm) |

60% and 70% of CBZ removal was achieved after 2 h photodegradation using conventional and microwave-assisted synthesised TiO2, respectively. 91% (Kapp = 0.0108 min–1) and 96% (Kapp = 0.0135 min–1) removal rate were achieved using conventional and micro-assisted synthesised 1 wt% Y-TiO2, respectively. | Kubiak et al. 2024 [45] |

||||

| Ag2O/TiO2 heterostructure |

0.5 g L–1 of catalyst 1 mg L–1 of CBZ and Atenolol (ATL) 500 mL of tap water and of filtered Secondary effluent collected from a water waste treatment plant |

Natural sunlight, Intensity = 765 W m−2 | Tap water = catalyst completely degraded ATL in 1 h and CBZ in 3 h of irradiation (Kapp = 0.073 and 0.0240 min–1, respectively) Filtered Secondary effluent = After 3 h of irradiation 100% and ~85% of ATL and CBZ were removed, respectively (Kapp = 0.0305 and 0.0118 min–1, respectively) |

Durán-Alvárez et al. 2024 [46] |

||||

| TiO2/BiPO4 (80/20) composite |

0.5 g L–1 of catalyst 100 mg L–1 of CBZ |

300 W UV-visible light Xenon lamp with two filters | 88% of the CBZ was degraded after 6 h of irradiation (Kapp = 0.0547 min–1) |

Mohammed-Amine et al. 2025 [47] |

||||

| Potassium and oxygen co-doped g-C3N4 (OCN-3) |

0.4 g L–1 of catalyst 0.1–10 mg L–1 of CBZ |

300 W UV light mercury lamp. Intensity = 15 mW cm–2 | ~100% of 1 mg L–1 of CBZ was degraded after 30 min of irradiation. OCN-3 also completely degraded 5 mg L–1 with a Kapp of 0.1753 min–1 | Wang et al. [48] | ||||

| MSTiP10 | 1 g L–1 of catalyst 1 mg L–1 of CBZ 100 mL reaction |

UV-LEDs (λ = 275 nm) |

MSTiP10 removed 98.58% of CBZ after 2 h of irradiation (Kapp = 0.0877 min–1) |

This Work | ||||

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Jiang, T.; Wu, W.; Ma, M.; Hu, Y.; Li, R. Occurrence and Distribution of Emerging Contaminants in Wastewater Treatment Plants: A Globally Review over the Past Two Decades. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 951, 175664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fekadu, S.; Alemayehu, E.; Dewil, R.; Van der Bruggen, B. Pharmaceuticals in Freshwater Aquatic Environments: A Comparison of the African and European Challenge. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 654, 324–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Geißen, S.-U.; Gal, C. Carbamazepine and Diclofenac: Removal in Wastewater Treatment Plants and Occurrence in Water Bodies. Chemosphere 2008, 73, 1151–1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Directorate-General for Environment of the European Commission, Proposal for a DIRECTIVE OF THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT AND OF THE COUNCIL: “Amending Directive 2000/60/EC Establishing a Framework for Community Action in the field of Water Policy, Directive 2006/118/EC on the Protection of Groundwater against pollution and Deterioration and Directive 2008/105/EC on Environmental Quality in the Field of Water Policy”; Brussels, 2022; https://environment.ec.europa.eu/publications/proposal-amending-water-directives_en.

- Saravanan, A.; Deivayanai, V. C.; Kumar, P.S.; Rangasamy, G.; Hemavathy, R. V.; Harshana, T.; Gayathri, N.; Alagumalai, K. A Detailed Review on Advanced Oxidation Process in Treatment of Wastewater: Mechanism, Challenges and Future Outlook. Chemosphere 2022, 308, 136524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Wang, C.; Wang, G. Photocatalytic Advanced Oxidation Processes for Water Treatment: Recent Advances and Perspective. Chem. Asian J. 2020, 15, 3239–3253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peiris, S.; de Silva, H. B.; Ranasinghe, K.N.; Bandara, S. V.; Perera, I. R. Recent Development and Future Prospects of TiO2 Photocatalysis. J. Chin. Chem. Soc. 2021, 68, 738–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Li, T.; Zhou, Q. Impact of Titanium Dioxide (TiO2) Modification on Its Application to Pollution Treatment—A Review. Catalysts 2020, 10, 804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Zhang, S.; Tan, Q.; Wu, X.; Li, Y.; Li, Q.; Fan, J.; Lv, K. Insulator in Photocatalysis: Essential Roles and Activation Strategies. Chem. Eng. J. 2021, 426, 130772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Zheng, W.; Liu, W. Enhanced Photocatalytic Activity of Supported TiO2: Dispersing Effect of SiO2. J. Photochem. Photobiol., A 1999, 122, 57–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Sun, S.; Ding, H.; Chen, W.; Liang, Y. Preparation of a Composite Photocatalyst with Enhanced Photocatalytic Activity: Smaller TiO2 Carried on SiO2 Microsphere. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2019, 493, 146–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz-Quesada, G.; Sampaio, M. J.; Espinal-Viguri, M.; López-Ramón, M. V.; Garrido, J. J.; Silva, C. G.; Faria, J. L. Design of Novel Photoactive Modified Titanium Silicalites and Their Application for Venlafaxine Degradation under Simulated Solar Irradiation. Sol. RRL 2024, 8, 2300593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BIZI, M. Activated Carbon and the Principal Mineral Constituents of a Natural Soil in the Presence of Carbamazepine. Water 2019, 11, 2290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, R. K.; Ghi, P. Y.; Puschmann, H.; Apperley, D. C.; Griesser, U. J.; Hammond, R. B.; Ma, C.; Roberts, K. J.; Pearce, G. J.; Yates, J. R.; Pickard, J. Structural Studies of the Polymorphs of Carbamazepine, Its Dihydrate, and Two Solvates. Org. Process Res. Dev. 2005, 9, 902–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunter, C. A.; McCabe, J. F.; Spitaleri, A. Solvent Effects of the Structures of Prenucleation Aggregates of Carbamazepine. CrystEngComm 2012, 14, 7115–7117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chemspider database, CSID:2457. Available online: https://www.chemspider.com/Chemical-Structure.2457.html (accessed on 20 February 2025).

- Nghiem, L. D.; Schäfer, A. I.; Elimelech, M. Pharmaceutical Retention Mechanisms by Nanofiltration Membranes. Environ Sci Technol 2005, 39, 7698–7705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Center for Biotechnology Information (2025). PubChem Compound Summary for CID 2554, Carbamazepine. Available online: https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/compound/Carbamazepine. (accessed on 20 February 2025).

- Shi, Y.; Chen, L.; li, J.; Hu, Q.; Ji, G.; Lu, Y.; Hu, X.; Zhu, B.; Huang, W. Co Supported on Interparticle Porosity Dominated Hierarchical Porous TS-1 as Highly Efficient Heterogeneous Catalyst for Epoxidation of Styrene. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2021, 762, 138116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, Q.; Chi, W.; Zhang, P.; Ling, Y.; Liu, X.; Cui, G.; Liu, W.; Shi, X.; Tang, B. Optimization of Bi2O3/TS-1 Preparation and Photocatalytic Reaction Conditions for Low Concentration Erythromycin Wastewater Treatment Based on Artificial Neural Network. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2022, 157, 297–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Desoky, M. M.; Morad, I.; Wasfy, M. H.; Mansour, A. F. Synthesis, Structural and Electrical Properties of PVA/TiO2 Nanocomposite Films with Different TiO2 Phases Prepared by Sol–Gel Technique. J. Mater. Sci.:Mater. Electron. 2020, 31, 17574–17584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz-Quesada, G.; Espinal-Viguri, M.; López-Ramón, M. V.; Garrido, J. J. Hybrid Xerogels: Study of the Sol-Gel Process and Local Structure by Vibrational Spectroscopy. Polymers 2021, 13, 2082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moriones, P.; Ríos, X.; Echeverría, J. C.; Garrido, J. J.; Pires, J.; Pinto, M. Hybrid Organic-Inorganic Phenyl Stationary Phases for the Gas Separation of Organic Binary Mixtures. Colloids Surf., A 2011, 389, 69–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fois, E.; Gamba, A.; Tabacchi, G. Influence of Silanols Condensation on Surface Properties of Micelle-Templated Silicas: A Modelling Study. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2008, 116, 718–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soekiman, C. N.; Miyake, K.; Hayashi, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Ota, M.; Al-Jabri, H.; Inoue, R.; Hirota, Y.; Uchida, Y.; Tanaka, S.; Kong, C. Y.; Nishiyama, N. Synthesis of Titanium Silicalite-1 (TS-1) Zeolite with High Content of Ti by a Dry Gel Conversion Method Using Amorphous TiO2–SiO2 Composite with Highly Dispersed Ti Species. Mater. Today Chem. 2020, 16, 100209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, K. M.; Manorama, S. V; Reddy, A.R. Bandgap Studies on Anatase Titanium Dioxide Nanoparticles. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2002, 78, 239–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujisawa, J.- i.; Eda, T.; Hanaya, M. Comparative Study of Conduction-Band and Valence-Band Edges of TiO2, SrTiO3, and BaTiO3 by Ionization Potential Measurements. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2017, 685, 23–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, T. E. Jr.; Fulton, C. C.; Mecouch, W. J.; Tracy, K. M.; Davis, R. F.; Hurt, E. H.; Lucovsky, G.; Nemanich, R. J. Measurement of the Band Offsets of SiO2 on Clean n- and p-Type GaN(0001). J. Appl. Phys. 2003, 93, 3995–4004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, L.; Huang, H.; Yu, S.; Zhang, D.; Huang, H.; Zhang, Y. Role of Transition Metal Oxides in G-C3N4-Based Heterojunctions for Photocatalysis and Supercapacitors. J. Energy Chem. 2022, 64, 214–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thommes, M.; Kaneko, K.; Neimark, A. V.; Olivier, J. P.; Rodriguez-Reinoso, F.; Rouquerol, J.; Sing, K. S. W. Physisorption of Gases, with Special Reference to the Evaluation of Surface Area and Pore Size Distribution (IUPAC Technical Report). Pure Appl. Chem. 2015, 87, 1051–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buxton, G. V; Greenstock, C. L.; Helman, W. P.; Ross, A. B. Critical Review of Rate Constants for Reactions of Hydrated Electrons, Hydrogen Atoms and Hydroxyl Radicals (·OH/·O-) in Aqueous Solution. J Phys Chem Ref Data 1988, 17, 513–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Escudero, C. M.; Garrido, I.; Contreras, F.; Hellín, P.; Flores, P.; León-Morán, L.O.; Arroyo-Manzanares, N.; Campillo, N.; Viñas, P.; Fenoll, J. Photocatalytic Oxidation of Carbamazepine in Water Using TiO2 with LED Lamps: Study of Intermediate Degradation Products by Liquid Chromatography Mass Spectrometry after Dispersive Liquid–Liquid Microextraction. J. Photochem. Photobiol., A 2024, 452, 115551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jelic, A.; Michael, I.; Achilleos, A.; Hapeshi, E.; Lambropoulou, D.; Perez, S.; Petrovic, M.; Fatta-Kassinos, D.; Barcelo, D. Transformation Products and Reaction Pathways of Carbamazepine during Photocatalytic and Sonophotocatalytic Treatment. J. Hazard. Mater. 2013, 263, 177–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, N.; Lei, Z.-D.; Wang, T.; Wang, J.-J.; Zhang, X.-D.; Xu, G.; Tang, L. Radiolysis of Carbamazepine Aqueous Solution Using Electron Beam Irradiation Combining with Hydrogen Peroxide: Efficiency and Mechanism. Chem. Eng. J. 2016, 295, 484–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brezina, E.; Prasse, C.; Meyer, J.; Mückter, H.; Ternes, T. A. Investigation and Risk Evaluation of the Occurrence of Carbamazepine, Oxcarbazepine, Their Human Metabolites and Transformation Products in the Urban Water Cycle. Environ. Pollut. 2017, 225, 261–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mcdowell, D. C.; Huber, M. M.; Wagner, M.; von Gunten, U.; Ternes, T. A. Ozonation of Carbamazepine in Drinking Water: Identification and Kinetic Study of Major Oxidation Products. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2005, 39, 8014–8022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmed, M. M.; Chiron, S. Solar Photo-Fenton like Using Persulphate for Carbamazepine Removal from Domestic Wastewater. Water Res. 2014, 48, 229–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.; Chen, Y.; Gu, Y.; Wu, F.; Lu, W.; Xu, T.; Chen, W. Catalytic Degradation of Recalcitrant Pollutants by Fenton-like Process Using Polyacrylonitrile-Supported Iron (II) Phthalocyanine Nanofibers: Intermediates and Pathway. Water Res 2016, 93, 296–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, X.; Li, M.; Li, M. Fabrication of Bi4O5Br2 Photocatalyst for Carbamazepine Degradation under Visible-Light Irradiation. Water Sci. Technol. 2021, 84, 77–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, Y.; Li, Z.; Tan, J.; Li, J.; Wu, J.; Zhang, T.; Wang, X. Oxygen-Doped Porous Graphitic Carbon Nitride in Photocatalytic Peroxymonosulfate Activation for Enhanced Carbamazepine Removal: Performance, Influence Factors and Mechanisms. Chem. Eng. J. 2022, 429, 130860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majumder, A.; Gupta, A. K.; Sillanpää, M. Insights into Kinetics of Photocatalytic Degradation of Neurotoxic Carbamazepine Using Magnetically Separable Mesoporous Fe3O4 Modified Al-Doped ZnO: Delineating the Degradation Pathway, Toxicity Analysis and Application in Real Hospital Wastewater. Colloids Surf., A 2022, 648, 129250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grzegórska, A.; Karczewski, J.; Zielińska-Jurek, A. Modelling and Optimisation of MXene-Derived TiO2/Ti3C2 Synthesis Parameters Using Response Surface Methodology Based on the Box–Behnken Factorial Design. Enhanced Carbamazepine Degradation by the Cu-Modified TiO2/Ti3C2 Photocatalyst. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2023, 179, 449–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, L.; Villabrille, P. I.; Marino, D. J.; Rosso, J. A.; Caregnato, P. Degradation of Carbamazepine in Surface Water: Performance of Pd-Modified TiO2 and Ce-Modified ZnO as Photocatalysts. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2023, 30, 116078–116090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandyal, P.; Sharma, R.; Sambyal, S.; Islam, N.; Priye, A.; Kumar, M.; Chauhan, V.; Shandilya, P. Cu2O/WO3: A Promising S-Scheme Heterojunction for Photocatalyzed Degradation of Carbamazepine and Reduction of Nitrobenzene. JWPE 2024, 59, 105008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubiak, A.; Cegłowski, M. Unraveling the Impact of Microwave-Assisted Techniques in the Fabrication of Yttrium-Doped TiO2 Photocatalyst. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durán-Álvarez, J. C.; Cortés-Lagunes, S.; Mahjoub, O.; Serrano-Lázaro, A.; Garduño-Jiménez, A.; Zanella, R. Tapping the Tunisian Sunlight’s Potential to Remove Pharmaceuticals in Tap Water and Secondary Effluents: A Comparison of Ag2O/TiO2 and BiOI Photocatalysts and Toxicological Insights. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2024, 335, 126221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed-Amine, E.; Kaltoum, B.; El Mountassir, E. M.; Abdelaziz, A. T.; Stephanie, R.; Stephanie, L.; Anne, P.; Pascal, W.-W. C.; Alrashed, M. M.; Salah, R. Novel Sol-Gel Synthesis of TiO2/BiPO4 Composite for Enhanced Photocatalytic Degradation of Carbamazepine under UV and Visible Light: Kinetic, Identification of Photoproducts and Mechanistic Insights. JWPE 2025, 70, 107098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Yao, Y.; Xiang, Y.; Zhu, X. Performance and Mechanic Insights into Potassium-Oxygen Co-Doping Graphic Carbon Nitride for UV Photocatalytic Oxidation of Carbamazepine. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2025, 353, 128577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández, M.; Fernández, M.; Laca, A.; Laca, A.; Díaz, M. Seasonal Occurrence and Removal of Pharmaceutical Products in Municipal Wastewaters. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2014, 2, 495–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).