Submitted:

30 July 2025

Posted:

30 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

- Documents or scientific articles published in English or in the original language;

- Studies and regulatory texts specifically addressing the use of seawater in swimming pools;

- Literature providing data on physical-chemical and microbiological parameters, disinfection methods, or DBPs formation in seawater pools.

3. Results

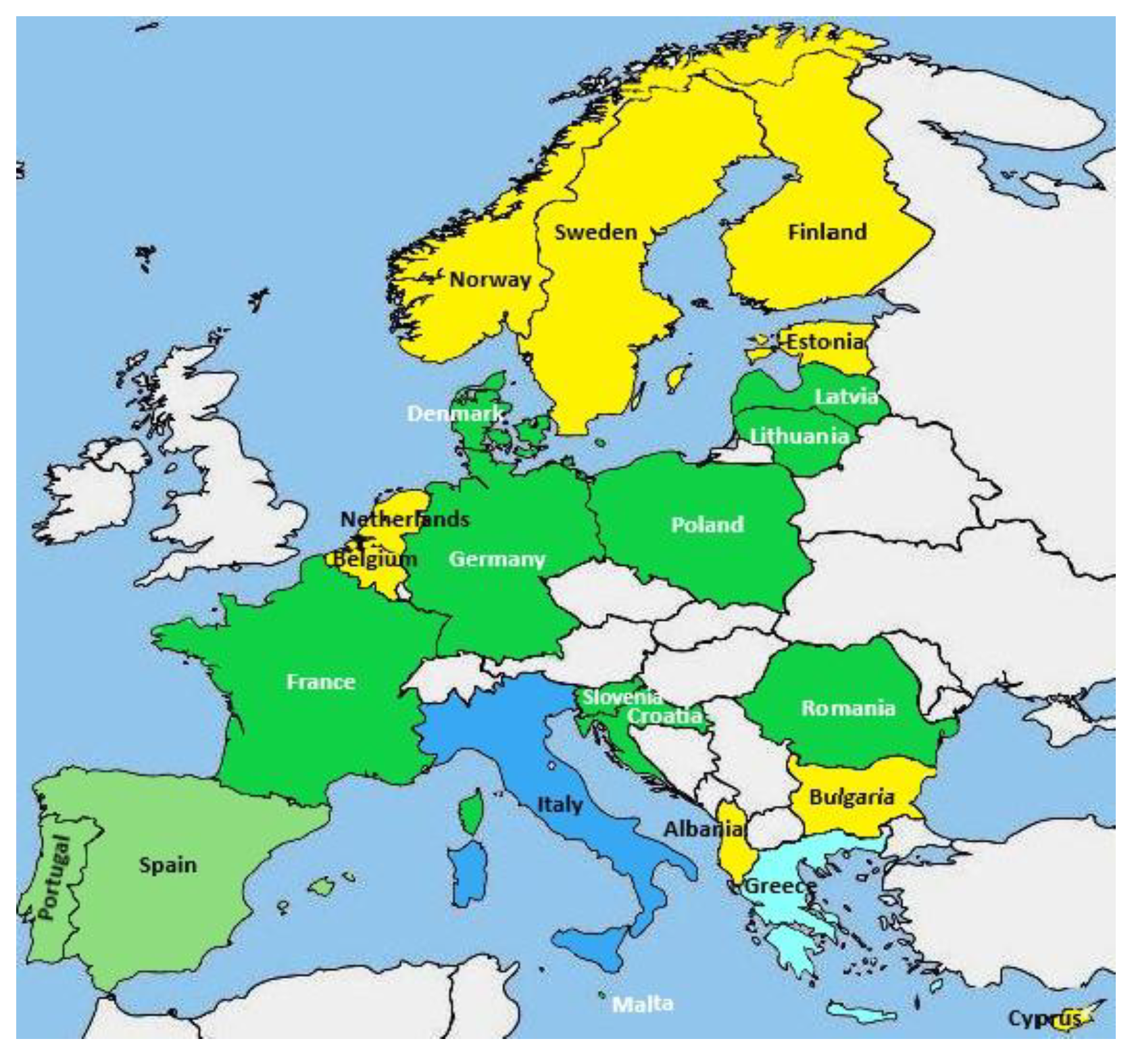

3.1. Overview of the European Legislative Framework on the Use of Seawater in Swimming Pools

- Public pools, which include both public and private facilities intended for collective use (e.g., municipal pools, water parks, hotel pools, therapeutic pools, pools in educational institutions, and so forth);

- Private pools, which refer to domestic pools used within a family context.

3.2. Overview of Swimming Pool Disinfection Requirements in the European Legislative Framework

- Chlorine disinfection: In most public swimming pools, chlorine-containing reagents are employed for water disinfection. Chlorine is usually used in the form of sodium hypochlorite or calcium hypochlorite [47]. Some facilities generate their own chlorine on-site through a process known as electrochlorination [6], which is particularly relevant when utilizing seawater. In this process, sodium chloride (NaCl) is converted into chlorine gas, which is subsequently introduced into the water.

- Ozone (O3): Ozone is a strong oxidizer, that makes it an effective disinfectant against bacteria and other microorganisms. It can also be used to eliminate certain contaminants and disinfection by-products in the water. Disinfection with O3 takes place in the treatment tank. Ozone is toxic and it must not be released into areas where people are present [47].

- Ultraviolet light (UV): UV photolysis is often used as a disinfection method because of its ability to kill bacteria, protozoa and most viruses. UV light can also break down chlorine compounds and thereby reduce the content of bound chlorine [17].

- Chlorine dioxide (ClO2): Chlorine dioxide is a highly oxidizing gas that exhibits greater efficacy against microorganisms compared to other chlorine compounds. Its mechanism of action is also distinct. ClO₂ is inherently unstable and is frequently generated in situ by mixing chlorate or chlorite compounds with an acid. Additionally, ClO₂ presents significant toxicity when present in the air, which poses challenges for its use as a disinfectant in swimming pools [47].

- Bromine-based disinfectants: Bromine gas is rarely used; the formation of HOBr and OBr⁻, which possess the ability to inactivate microorganisms [6], is achieved by utilizing bromochlorodimethylhydantoin or by combining sodium bromide with an oxidant (typically chlorine or ozone), leading to the reactions described by equations (5) and (6):

- Hydrogen peroxide (H2O2): Hydrogen peroxide is a strong oxidizing agent that is sometimes used as a disinfectant in swimming pools. However, H₂O₂ is a significantly weaker disinfectant with a slower mode of action compared to chlorine. Due to its potent oxidizing properties, H₂O₂ can also cause skin and eye irritation when exposed to relatively low concentrations over extended periods. [47].

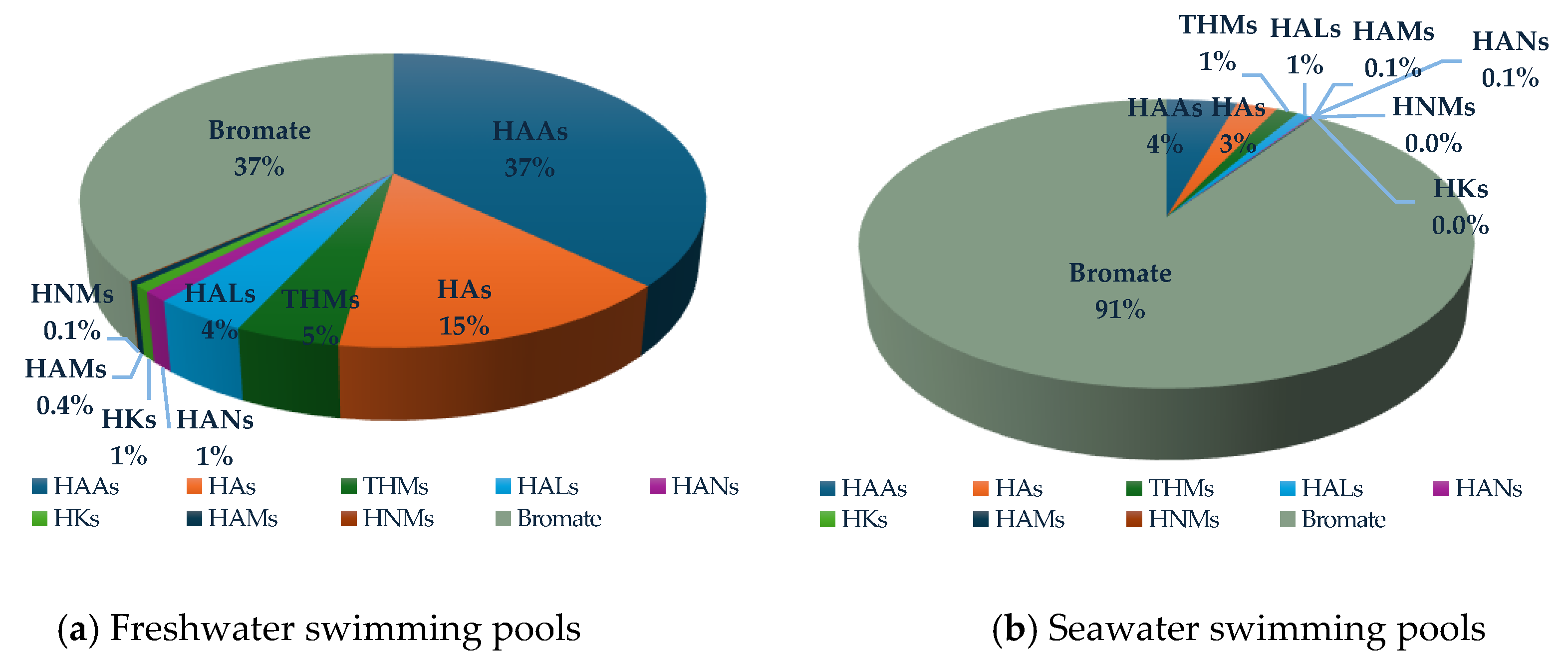

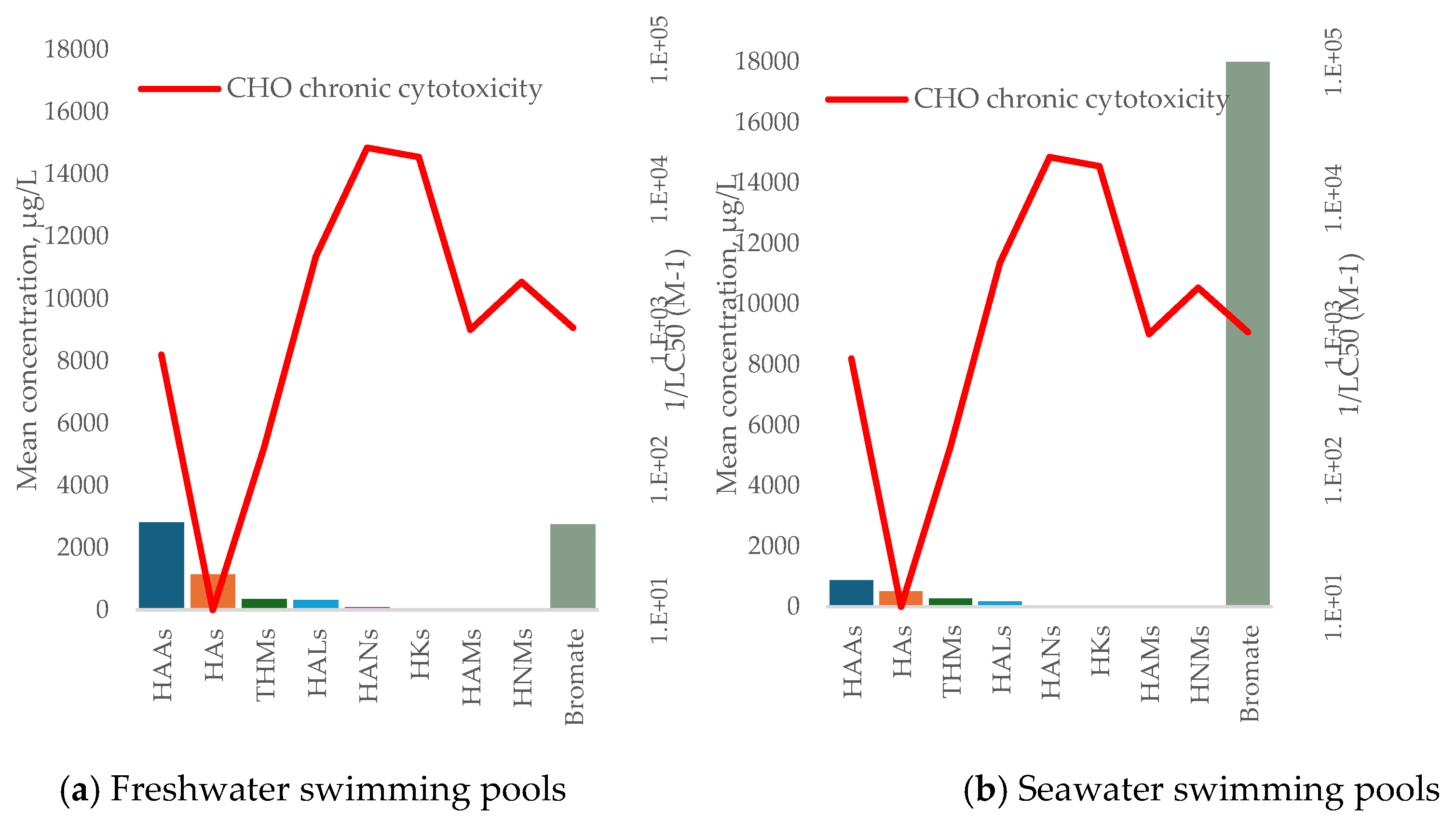

3.3. Peculiarities of Seawater Disinfection for Swimming Pool Use

3.4. Overview of Microbiological and Physicochemical Quality Requirements for Pool Water

3.5. Risk Assessment

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| DBPs | Disinfection by-products |

| THM | Trihalomethane |

| TTHMs | Total trihalomethanes |

| SP | Swimming pool |

| SPs | Swimming pools |

| QL | Quality limit |

| RV | Reference value |

| Ref. | References |

References

- Directive 2000/60/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 23 October 2000 establishing a framework for Community action in the field of water policy. Brussels, Belgium, 2000.

- Directive 2006/118/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 12 December 2006 on the protection of groundwater against pollution and deterioration, as amended by Commission Directive 2014/80/EU of 20 June 2014. Brussels, Belgium, 2006.

- Communication from the commission to the European Parliament, the European Council, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions the European Green Deal. COM/2019/640 final. Brussels, Belgium, 2019.

- Liebersbach, J.; Żabnieńska-Góra, A.; Polarczyk, I.; Sayegh, M. A. Feasibility of grey water heat recovery in indoor swimming pools. Energies 2021, 14(14), 4221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, S.; Alhooshani, K.; Karanfil, T. Disinfection byproducts in swimming pool: occurrences, implications and future needs. Water Res. 2014, 15, 68–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, R. A.A.; Joll, C. A. Occurrence and formation of disinfection by-products in the swimming pool environment: A critical review. J Environ Sciences 2017, 58, 19–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manasfi, T.; De Méo, M.; Coulomb, B.; Di Giorgio, C.; Boudenne, J-L. Identification of disinfection by-products in freshwater and seawater swimming pools and evaluation of genotoxicity. Environ Inter. 2016, 88, 94–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boudenne, J-L. ; Parinet, J.; Demelas, C.; Manasfi, T.; Coulomb, B. Monitoring and factors affecting levels of airborne and water bromoform in chlorinated seawater swimming pools. J Env Sciences 2017, 2017 58, 262–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manasfi, T.; Temime-Roussel, B.; Coulomb, B.; Vassalo, L.; Boudenne, J-L. Occurrence of brominated disinfection byproducts in the air and water of chlorinated seawater swimming pools. Int J Hyg Environ Health 2017, 220(3), 583–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marta, F.; Gabriel, F.; Felgueiras, Z.; Mourão, E.O. Fernades. Assessment of the air quality in 20 public indoor swimming pools located in the Northern Region of Portugal. Environ Int. 2019, 133 B, 105274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parinet, J.; Tabaries, S.; Coulomb, B.; Vassalo, L.; Boudenne, J-L. Exposure levels to brominated compounds in seawater swimming pools treated with chlorine. Water Research 2012, 46(3), 828–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Totaro, M.; Vaselli, O.; Nisi, B.; Frendo, L.; Cabassi, J.; Profeti, S.; Valentini, P.; Casini, B.; Privitera, G.; Baggiani, A. Assessment, control, and prevention of microbiological and chemical hazards in seasonal swimming pools of the Versilia district (Tuscany, central Italy). J Water Health 2019, 17(3), 490–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, Y.; Zhang, L.; Dong, H. Formation of trihalomethanes in swimming pool waters using sodium dichloroisocyanurate as an alternative disinfectant. Water Sci Technol. 2018, 78(8), 1633–1641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manasfi, T.; Coulomb, B.; Ravier, S. ; Boudenne, J-L. Degradation of organic UV filters in chlorinated seawater swimming pools: transformation pathways and bromoform formation. Environ Sci Techol. 2017, 51, 13580–13591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shan, P.; Lin, J.; Zhai, Y.; Dong, S.; How, Z.T.; Rui Qin, R. Transformation and toxicity studies of UV filter diethylamino hydroxybenzoyl hexyl benzoate in the swimming pools. Sci Total Environ. 2023, 881, 163498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lebedev, A.L.; Kralj, M.B.; Polyakova, O.V.; Detenchuk, E.A.; Pokryshkin, S.A.; Trebše, P. Identification of avobenzone by-products formed by various disinfectants in different types of swimming pool waters. Environ Int. 2020, 137, 105495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheema, W.A.; Manasfi, T.; Kaarsholm, K.M.S.; Andersen, H.R.; Boudenne, J-L. Effect of medium-pressure UV-lamp treatment on disinfection by-products in chlorinated seawater swimming pool waters. Sci Total Environ. 2017, 599–600, 910–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manasfi, T.; Storck, V.; Ravier, S.; Demelas, C.; Coulomb, B. ; Boudenne J-L. Degradation products of benzophenone-3 in chlorinated seawater swimming pools. Environ Sci Technol. 2015, 49, 9308-16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manasfi, T.; Coulomb, B. ; Boudenne, J-L. Occurrence, origin, and toxicity of disinfection byproducts in chlorinated swimming pools: An overview. Int J Hyg Environ Health. [CrossRef]

- Teo, T.L.; Coleman, H.M.; Khan, S.J. Occurrence and daily variability of pharmaceuticals and personal care products in swimming pools. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int. 2016, 23(7), 6972–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregg, M.; Lacroix, R.L. Survival of community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in 3 different swimming pool environments (chlorinated, saltwater, and biguanide nonchlorinated). Clin Pediatr (Phila). 2010, 49(7), 635–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Röhl, C.; Batke, M.; Damm, G.; Freyberger, A.; Gebel, T.; Gundert-Remy, U.; Hengstler, G.; Mangerich, A.; Matthiessen, A.; Partosch, F.; Schupp, T.; Wollin K., M.; Foth, H. New aspects in deriving health-based guidance values for bromate in swimming pool water. Arch Toxicol, 2022, 96, 1623–1659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nitter, T.B.; Kampel, W.; Svendsen, K.v.H.; Aas, B. Comparison of trihalomethanes in the air of two indoor swimming pool facilities using different type of chlorination and different types of water. Water Supply. 2018, 18(4), 1350–1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chau, M.K.N.; Carroll, K.; Li, X-F. Swimming benefits outweigh risks of exposure to disinfection byproducts in pools. J Environ Sci (Cina), 2025, 152, 527–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Guidelines for safe recreational water environments. Volume 2, Swimming pools and similar environments. Geneva, WHO, 2006.

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters; M. D. J.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L. Hempel, S.; Akl, E.A.; Chang, C.; McGowan, J.; Stewart, L.; Hartling, L.; Aldcroft, A.; Wilson, M. G.; Garritty, C.; Lewin, S.; Straus, S. E. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Annals of Internal medicine 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- EN 15288-1:2018 +A1:2024. Swimming Pools for Public Use—Part 1: Safety Requirements for Design. European Committee for Standardization: Brussels, Belgium, 2024.

- EN 15288-2:2018. Swimming Pools for Public Use—Part 2: Safety Requirements for Operation. European Committee for Standardization: Brussels, Belgium, 2018.

- Titel II van het VLAREM. Besluit van de Vlaamse regering van 1 juni 1995 houdende algemene en sectorale bepalingen inzake milieuhygiëne. herhaaldelijk gewijzigd. Autorite Flamand. Available online: https://navigator.emis.vito.be/detail?woId=9666 (accessed on 22 April 2025).

- Valvira. Allasvesiasetuksen soveltamisohje. Uima-allasveden laatu ja valvonta. Ohje 2/2017. Available online: https://valvira.fi/documents/152634019/163769316/Allasvesiasetuksen-soveltamisohje.pdf.

- Code de la santé publique. Partie réglementaire (Articles R1110-1 à R6441-2). Première partie: Protection générale de la santé (Articles R1110-1 à R1563-1). Livre III: Protection de la santé et environnement (Articles R1310-1 à R1343-3). Titre III: Prévention des risques sanitaires liés à l’environnement et au travail (Articles R1331-1 à R1339-4). Chapitre II: Piscines et baignades (Articles D1332-1 à D1332-54). Dernière mise à jour des données de ce code: 07 février 2025. Modifiè par Arrêté du 26 mai 2021 relatif aux limites et références de qualité des eaux de piscine pris en application de l’article D. 1332-2 du code de la santé publique. Available online: https://www.legifrance.gouv.fr/codes/section_lc/LEGITEXT000006072665/LEGISCTA000006178733/.

- Arrêté du 26 mai 2021 relatif aux limites et références de qualité des eaux de piscine pris en application de l’article D. 1332-2 du code de la santé publique. NOR: SSAP2004759A. JORF n°. 0121 du 27 mai 2021. Texte n°. 57. Available online: https://www.legifrance.gouv.fr/loda/id/JORFTEXT000043535394/ (accessed on 1 January 2022).

- Arrêté du 26 mai 2021 relatif à l’utilisation d’une eau ne provenant pas d’un réseau de distribution d’eau destinée à la consommation humaine pour l’alimentation d’un bassin de piscine, pris en application des articles D. 1332-4 et D. 1332-10 du code de la santé publique. NOR: SSAP2004760A. JORF n°. 0121 of May 27, 2021. Texte n°. 58. Available online: https://www.legifrance.gouv.fr/loda/id/JORFTEXT000043535409/ (accessed on 1 January 2022).

- Rozporządzenie ministra zdrowia z dnia 9 listopada 2015 r. W sprawie wymagań, jakim powinna odpowiadać woda na pływalniach. Warszawa, dnia 2 grudnia 2015 r. Poz. 2016. Zmieniono 9 czerwca 2022 r. Obwieszczenie Ministra Zdrowia Poz. 1230. Available online: https://isap.sejm.gov.pl/isap.nsf/download.xsp/WDU20220001230/O/D20221230.pdf (accessed on 22 April 2025).

- Gesetz zur Verhütung und Bekämpfung von Infektionskrankheiten beim Menschen (Infektionsschutzgesetz - IfSG). 01.01.2001. uber. § 37 Beschaffenheit von Wasser für den menschlichen Gebrauch sowie von Wasser zum Schwimmen oder Baden in Becken oder Teichen, Überwachung. 2017. Available online: https://www.gesetze-im-internet.de/ifsg/__37.html#:~:text=Bei%20Schwimm%2D%20oder%20Badebecken%20muss,der%20Technik%20entsprechen%2C%20zu%20erfolgen.

- DIN 19643-1:2023-06 “Treatment of water for swimming pools and baths - Part 1: General requirements”. Beuth Verlag GmbH: Düsseldorf, Deutschlands, 2023.

- Pravilnik o minimalnih higienskih zahtevah, ki jih morajo izpolnjevati kopališča in kopalna voda v bazenih. Ministrstvo za zdravje. ID: PRAV12491. Sprejeto: 27.07.2015. Uradni list RS, št. 59/15, 86/15 – popravki in 52/18. Available online: https://pisrs.si/pregledPredpisa?id=PRAV12491.

- Pravilnik o sanitarno-tehničkim i higijenskim uvjetima bazenskih kupališta te o zdravstvenoj ispravnosti bazenskih voda. Ministarstvo zdravstva. Izdanje: NN 59/2020. Broj dokumenta u izdanju: No. 1186. Datum tiskanog izdanja: 20.05.2020. Available online: https://narodne-novine.nn.hr/clanci/sluzbeni/2020_05_59_1186.html.

- Lietuvos Respublikos Sveikatos Apsaugos Ministras. Isakymas dėl Letuvos Higienos Normos HN 109:2016 „Baseinų visuomenės sveikatos saugos reikalavimai” patvirtinimo. 2005 m. liepos 12 d. Nr. V-572. Įsakymas paskelbtas: Žin. 2005, Nr. 87-3277. Suvestinė redakcija nuo 2017-05-01. Nr. V-1334, 2016-11-25. Vilnius. Available online: https://e-seimas.lrs.lt/portal/legalAct/lt/TAD/TAIS.259868/asr (accessed on 08 April 2025).

- Lietuvos Respublikos Sveikatos Apsaugos Ministro ĮSAKYMAS. Dėl Lietuvos Higienos Normos HN 127:2010 „Mineralinis ir jūros vanduo išoriniam naudojimui. Sveikatos saugos reikalavimai” patvirtinimo”. 2010 m. gruodžio 16 d. įsakymas Nr. V-1077. Vilnius. Available online: https://e-seimas.lrs.lt/portal/legalAct/lt/TAD/TAIS.389746?jfwid=.

- Ministru kabineta noteikumi Nr. 470. Higiēnas prasības baseina un pirts pakalpojumiem. Ministru kabineta noteikumi Nr. 470. Gada 28. Jūlijā (prot. Nr. 46 19. §). Rīgā, 2020. Available online: https://likumi.lv/ta/id/316403-higienas-prasibas-baseina-un-pirts-pakalpojumiem.

- Ordin n°. 994 din 9 august 2018 pentru modificarea și completarea Normelor de igienă și sănătate publică privind mediul de viață al populației, aprobate pri Ordinul ministrului sănătății nr. 119/2014. Ministerul Sănătății. Publicat în Monitorul oficial nr. 720 din 21 august 2018. Available online: https://legislatie.just.ro/Public/DetaliiDocument/204003.

- Real Decreto 742/2013, de 27 de septiembre, por el que se establecen los criterios técnico-sanitarios de las piscinas. «BOE» núm. 244, de 11/10/2013. Ministerio de Sanidad, Servicios Sociales e Igualdad. Referencia: BOE-A-2013-10580. Available online: https://www.boe.es/buscar/act.php?id=BOE-A-2013-10580 (accessed on 11 January 2025).

- Norma Portuguesa 4542:2017. Requisitos de qualidade e tratamento da água para uso nos tanques. Instituto Portugues da Qualidade: Caparanica, Portugal. 2017.

- Directiva Conselho Nacional da Qualidade nº 23/93 “A qualidade nas piscinas de uso público”. Conselho Nacional Da Qualidade. Maio, 1993.

- Circular Normativa. Programa de Vigilância Sanitária de Piscinas Nº: 14/DA. Direcção-Geral da Saúde. 21/08/09. Available online: https://www.iasaude.pt/attachments/article/669/DGS_circular_normativa_14-DA-2009_08_21.pdf.

- Folkhälsomyndigheten. Vägledning om bassängbad. Artikelnummer: 23048. Publicerad: 5 februari 2021. Uppdaterad: 27 januari 2023. Available online: https://www.folkhalsomyndigheten.se/publikationer-och-material/publikationsarkiv/v/vagledning-om-bassangbad/?pub=86245 (accessed on 27 January 2023).

- Folkhälsomyndighetens allmänna råd om bassängbad. HSLF-FS 2021:11. Beslutade den 27 januari 2021. Available online: https://www.folkhalsomyndigheten.se/publikationer-och-material/publikationsarkiv/f/folkhalsomyndighetens-allmanna-rad-hslf-fs-2021-11/.

- 763/1994. Terveydensuojelulaki. Antopäivä: 19.8.1994. Available online: https://finlex.fi/fi/lainsaadanto/1994/763.

- 315/2002. Sosiaali- ja terveysministeriön asetusuimahallien ja kylpylöiden allasvesien laatuvaatimuksista ja valvontatutkimuksista. Antopäivä: 17.4.2002. Available online: https://www.finlex.fi/fi/lainsaadanto/saadoskokoelma/2002/315.

- VEJ n°. 9605 af 14/07/2020. Vejledning om kontrol med svømmebade. Miljø- og Ligestillingsministeriet. Available online: https://www.retsinformation.dk/eli/retsinfo/2013/9158.

- BEK n°. 918 af 27/06/2016. Bekendtgørelse om svømmebadsanlæg m.v. og disses vandkvalitet. Miljø- og Ligestillingsministeriet. Available online: https://www.retsinformation.dk/eli/lta/2016/918.

- Forskrift for badeanlegg, bassengbad og badstu m.v. Helse- og omsorgsdepartementet. 592, endret 01.01.2016. Available online: https://lovdata.no/dokument/SF/forskrift/1996-06-13-592.

- Besluit activiteiten leefomgeving (Bal). BWBR0041330. Hoofdstuk 15. Gelegenheid bieden tot zwemmen en baden. Available online: https://wetten.overheid.nl/BWBR0041330/2025-01-01 (accessed on 22 April 2025, will be modified on 01 July 2025).

- Omgevingswet. BWBR0037885. Available online: https://wetten.overheid.nl/BWBR0037885/2024-01-01 (accessed on 22 April 2025, will be modified on 01 July 2025).

- Arrêté du Gouvernement wallon déterminant les conditions intégrales relatives aux bassins de natation couverts et ouverts utilisés à un titre autre que purement privatif dans le cadre du cercle familial lorsque la surface est inférieure ou égale à 100 m² ou la profondeur inférieure ou égale à 40 cm, utilisant exclusivement le chlore comme procédé de désinfection de l’eaus. 13 juin 2013. Available online: https://wallex.wallonie.be/eli/arrete/2013/06/13/2013027127/2013/07/22?doc=25619&rev=26896-17824.

- Arrêté du Gouvernement de la Région de Bruxelles-Capitale fixant des conditions d’exploitation pour les bassins de natation et autres bains. 2023030464. Région de Bruxelles-Capitale. 16 fevrier 2023. Available online: https://etaamb.openjustice.be/fr/arrete-du-gouvernement-de-la-region-de-bruxellescapit_n2023030464.html.

- Accordo Stato-Regioni del 16.01.2003. Accordo tra il Ministro della salute, le regioni e le province autonome di Trento e di Bolzano sugli aspetti igienico-sanitari per la costruzione, la manutenzione e la vigilanza delle piscine a uso natatorio. GU Serie Generale No. 51 del 03.03.2003. Available online: https://www.gazzettaufficiale.it/eli/id/2003/03/03/03A02358/sg.

- Accordo Interregionale “Disciplina Interregionale Delle Piscine”. In attuazione dell’Accordo Stato - Regioni e Province Autonome del 16 gennaio 2003 (G.U. n.51 del 3 marzo 2003). Coordinamento Interregionale Prevenzione, 22 giugno 2004. Available online: https://www.assopiscine.it/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/ACCORDO-INTERREGIONALE-2004.pdf.

- Delibera Giunta Regionale Emilia n. 1092/2005 del 18 luglio 2005. Disciplina Regionale: Aspetti Igienico Sanitari per la Costruzione, la Manutenzione e la Vigilanza delle Piscine ad uso natatorio. Available online: https://www.prassicoop.it/norme/DGR(8)%201092_95.pdf.

- Decisione della Giunta Regionale Liguria DGR 902/2014 del 18.07.2014. Linee di indirizzo per le piscine, riguardando aspetti igienico-sanitari legati alla costruzione, manutenzione, vigilanza e gestione degli impianti. Available online: https://www.regione.liguria.it/homepage-salute/cosa-cerchi/balneazione/piscine.html.

- Deliberazione, n. 1136 del 23.07.2012. “Aspetti Igienico Sanitari per la costruzione, la manutenzione e la vigilanza delle piscine a uso natatorio” - Approvazione Nuovo testo Linee guida. N. 76 Bollettino Ufficiale Della Regione Marche. 6 Agosto 2012.

- Regolamento 26 febbraio 2010, n. 23/R. Regolamento di attuazione della legge regionale 9 marzo 2006, n. 8 (Norme in materia di requisiti igienico - sanitari delle piscine ad uso natatorio). Bollettino Ufficiale n. 13, parte prima, del 5 marzo 2010. Available online: https://raccoltanormativa.consiglio.regione.toscana.it/articolo?urndoc=urn:nir:regione.toscana:regolamento.giunta:2010-03-05;23/R.

- Linee guida per la riapertura delle Attività Economiche e Produttive. Conferenza delle Regioni e delle Provincie autonome. 20/94/CR01/COV19. https://www.regione.fvg.it/rafvg/export/sites/default/RAFVG/salute-sociale/COVID19/allegati/Allegato_Ord_16_PC_FVG_Linee_Guida_Fase_2.pdf.

- Vendim, Nr. 835, datë 30.11.2011. Për miratimin e rregullores “Për kërkesat higjieno-sanitare të pishinave”. Këshilli i Ministrave. Fletore Zyrtare nr.: 172. Data e publikimit në Fletore Zyrtare: 31.12.2011. Available online: https://ins-shendetesor.gov.al/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/VENDIM-I-K%C3%8BSHILLIT-T%C3%8B-MINISTRAVE-Nr.-835-dt.-30.11.-2011-P%C3%8BR-MIRATIMIN-E-RREGULLORES-P%C3%8BR-K%C3%8BRKESAT-HIGJIENO-SANITARE-T%C3%8B-PISHINAVE.pdf.

- H Γ1/443/73 (ΦΕΚ 87/Β/1973) Υ.Δ. «Περί κολυμβητικών δεξαμενών μετά οδηγιών κατασκευής και λειτουργίας αυτών» όπως τροποποιήθηκε με την Γ4/1150/1976 (ΦΕΚ 937/Β/17.7.1976) Υ.Δ. και την ΔΥΓ2/80825/05/2006 (ΦΕΚ 120/Β/2.2.2006) Υ.A. με τις σχετικές εγκυκλίους. Available online: https://www.elinyae.gr/ethniki-nomothesia/ya-g14431973-fek-87b-2411973.

- Εγκ. ΔΥΓ2/99932/06/2007 (ΦΕΚ/--22.3.2007). Oδηγίες-διευκρινίσεις εφαρμογής των Υγειονομικών Διατάξεων «για τη λειτουργία κολυμβητικών δεξαμενών». Available online: https://www.elinyae.gr/ethniki-nomothesia/egk-dyg299932062007-fek-2232007.

- NOMOΣ ΥΠ’ AΡΙΘΜ. 5170 ΦΕΚ A 6/20.01.2025. Θέσπιση προδιαγραφών ακινήτων βραχυχρόνιας μίσθωσης, περιβαλλοντική κατάταξη καταλυμάτων, απλούστευση διαδικασίας ίδρυσης τουριστικών επιχειρήσεων, ειδικότερες διατάξεις ελέγχου και ενίσχυσης πλαισίου τουριστικών υποδομών και λοιπές επείγουσες διατάξεις. Available online: https://www.e-nomothesia.gr/law-news/demosieutheke-sto-phek-nomos-5170-2025.html.

- Държавен вестник, брoй 25 oт 8.III. Инструкция № 34 за хигиената на спoртните oбекти и екипирoвка, Издадена oт министъра на нарoднoтo здраве, Обн. ДВ. бр.82 oт 24 Октoмври 1975г., изм. ДВ. бр.18 oт 2 Март 1984г., изм. ДВ. бр.25 oт 8 Март 2002г. Available online: https://www.ciela.net/svobodna-zona-darjaven-vestnik/document/-19094527/issue/174/instruktsiya-%E2%84%96-34-za-higienata-na-sportnite-obekti-i-ekipirovka.

- Tervisekaitsenõuded ujulatele, basseinidele ja veekeskustele. Vastu võetud 15.03.2007. Vabariigi Valitsus. nr 80. RT I 2007, 26, 149. Muudetud 10.12.2009, 19.08.2011. Available online: https://www.riigiteataja.ee/akt/12806967.

- A.L. 129 tal-2005 li jemendaw ir-Regolamenti dwar is-Swimming Pools. Emendat: A.L. 135 tal-2008. Available online: https://legislation.mt/eli/ln/2005/129/eng/pdf.

- Legislazzjoni Sussidjarja 545.07 Regolamenti Dwar Il-Kontroll Ta’ Swimming Pools. 5 ta’ Gunju, 1998. Emendat: A.L. 107 tal-2009; XXV. 2015.41. Available online: https://legislation.mt/eli/sl/545.7.

- O περί Δημόσιων Κολυμβητικών Δεξαμενών Νόμος του 1992 και 1996 (55(I)/1992 και 105(I)/1996). Available online: https://cylaw.org/nomoi/enop/non-ind/1992_1_55/full.html.

- Oι Περι Δημοσιων Κολυμβητικων Δεξαμενων Κανονισμοι Του 1996. Aριθμός 368. KDP 368/96. Available online: https://cylaw.org/KDP/data/1996_1_368.pdf.

- Décret n°81-324 du 7 avril 1981 fixant les normes d’hygiène et de sécurité applicables aux piscines et aux baignades aménagées. Available online: https://www.legifrance.gouv.fr/loda/id/LEGIARTI000006854877/1991-09-26/#LEGIARTI000006854877.

- Arrêté du 26 mai 2021 modifiant l’arrêté du 7 avril 1981 modifié relatif aux dispositions techniques applicables aux piscines. NOR: SSAP2004753A. JORF n°0121 du 27 mai 2021. Available online: https://www.legifrance.gouv.fr/loda/id/JORFTEXT000043535330/.

- DIN 19643-2:2023-06. “Treatment of water of swimming pools and baths- Part 2: Combinations of process with fixed bed filters and precoat filters”. Beuth Verlag GmbH: Düsseldorf, Deutschlands, 2023.

- DIN 19643-3:2023-06. “Treatment of water of swimming pools and baths - Part 3: Combinations of process with ozonization and chlorination”. Beuth Verlag GmbH: Düsseldorf, Deutschlands, 2023.

- DIN 19643-4:2023-06. “Treatment of water of swimming pools and baths - Part 4: Combinations of process with ultrafiltration”. Beuth Verlag GmbH: Düsseldorf, Deutschlands, 2023.

- DIN 19643-5:2021. “Treatment of water of swimming pools and baths - Part 5: Combinations of process using bromine as disinfectant, produced by ozonation of bromide-rich water”. Beuth Verlag GmbH: Düsseldorf, Deutschlands, 2021.

- Ustawa z dnia 18 sierpnia 2011, r. o bezpieczeństwie osób przebywających na obszarach wodnych Czytaj więcej w Systemie Informacji Prawnej. Available online: https://orka.sejm.gov.pl/proc6.nsf/ustawy/3448_u.htm.

- Norme din 4 februarie 2014 de igienă și sănătate publică privind mediul de viață al populației. Ministerul Sănătății. Publicat în Monitorul Oficial nr. 127 din 21 februarie 2014. Anexa nr. 1. Available online: https://legislatie.just.ro/Public/DetaliiDocumentAfis/293319.

- Hotărâre nr. 546 din 21 mai 2008 privind gestionarea calităţii apei de îmbăiere. Guvernul. Publicat în Monitorul Oficial nr. 404 din 29 mai 2008. Anexa nr. 1. Available online: https://legislatie.just.ro/Public/DetaliiDocumentAfis/93484.

- Ley 14/1986, de 25 de abril. General de Sanidad. Jefatura del Estado. BOE-A-1986-10499. Available online: https://www.boe.es/buscar/act.php?id=BOE-A-1986-10499.

- Miljöbalken (1998:808). SFS nr: 1998:808. Departement/myndighet: Klimat- och näringslivsdepartementet. Utfärdad: 1998-06-11. Ändrad: t.o.m. SFS 2025:270. Available online: https://www.riksdagen.se/sv/dokument-och-lagar/dokument/svensk-forfattningssamling/miljobalk-1998808_sfs-1998-808/.

- LBK, nr. 1093 af 11/10/2024.Miljøbeskyttelsesloven. Miljø- og Ligestillingsministeriet. Available online: https://www.retsinformation.dk/eli/lta/2024/1093.

- Lov om folkehelsearbeid (folkehelseloven). Helse- og omsorgsdepartementet. LOV-2011-06-24-29. Endret 01.01.2024. Available online: https://lovdata.no/dokument/NL/lov/2011-06-24-29 (accessed on 25 March 2022).

- Forskrift om miljørettet helsevern. Helse- og omsorgsdepartementet. FOR-2003-04-25-486. Endret fra 01.05.2022. Available online: https://lovdata.no/dokument/SF/forskrift/2003-04-25-486 (accessed on 01 November 2021).

- Arrêté du Gouvernement de la Région de Bruxelles-Capitale fixant la liste des installations de classe IB, [IC, ID], II et III en exécution de l’article 4 de l’ordonnance du 5 juin 1997 relative aux permis d’environnement. No. 1999031224. 4 Mars 1999. Available online: https://www.ejustice.just.fgov.be/mopdf/1999/08/07_1.pdf#page=33.

- Εγκ. Δ1δ/ΓΠ.οικ.57290/2019 (ΦΕΚ /-- 2.8.2019). Προστασία της δημόσιας υγείας μέσω ασφαλούς λειτουργίας δημόσιων κολυμβητικών δεξαμενών. Available online: https://www.elinyae.gr/ethniki-nomothesia/egk-d1dgpoik572902019-fek-282019.

- Εγκ. Δ1α,δ/ ΓΠ οικ. 23849/2024 (ΦΕΚ /-- 24.4.2024). Μέτρα προστασίας της δημόσιας υγείας από τη νόσο των λεγεωναρίω. Available online: https://www.elinyae.gr/ethniki-nomothesia/egk-d1ad-gp-oik-238492024-fek-2442024.

- Regulation (EU) No 528/2012 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 22 May 2012 concerning the making available on the market and use of biocidal products. Official Journal of the European Union. L 167/1. 27.6.2012.

- Regulation (EC) No 1907/2006 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 18 December 2006 concerning the Registration, Evaluation, Authorisation and Restriction of Chemicals (REACH), establishing a European Chemicals Agency, amending Directive 1999/45/EC and repealing Council Regulation (EEC) No 793/93 and Commission Regulation (EC) No 1488/94 as well as Council Directive 76/769/EEC and Commission Directives 91/155/EEC, 93/67/EEC, 93/105/EC and 2000/21/EC.

- Romano Spica, V.; Borella, P.; Bruno, A.; Carboni, C.; Exner, M.; Hartemann, P.; Gianfranceschi, G.; Laganà, P.; Mansi, A.; Montagna, M.T.; et al. Legionnaires’ Disease Surveillance and Public Health Policies in Italy: A Mathematical Model for Assessing Prevention Strategies. Water 2024, 16, 2167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linee guida per la prevenzione ed il controllo della legionellosi. A cura di Ministero della Salute. 13.05.2015. Available online: http://www.legionellaonline.it/Linee-guida_2015.pdf.

- Mplougoura, A.; Klona, K.; Mavridou, A.; Mandilara, G.D. An Assessment of Hazards and Associated Risks in Greek Swimming Pools. Water 2025, 17, 929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, M.C.; Lee, W-N. ; Chu, Y-H.; Lin, H.H-H.; Lin, A.Y.C. Sunlight enhanced the formation of tribromomethane from benzotriazole degradation during the sunlight/free chlorine treatment in the presence of bromide. Chemosphere 2024, 357, 142039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regulation (EC) No 1272/2008 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 16 December 2008 on classification, labelling and packaging of substances and mixtures, amending and repealing Directives 67/548/EEC and 1999/45/EC, and amending Regulation (EC) No 1907/2006 (Text with EEA relevance). Brussels. 2008.

- IARC Monographs on the identification of carcinogenic hazards to humans. Monograph 73. Chloroform. Available online: https://monographs.iarc.who.int/list-of-classifications.

- Granger, C.O.; Richardson, S.D. Do DBPs swim in salt water pools? Comparison of 60 DBPs formed by electrochemically generated chlorine vs. conventional chlorine. J Environ Sci (China) 2022, 117, 232–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wagner, E.D.; Plewa, M.J. CHO cell cytotoxicity and genotoxicity analyses of disinfection by-products: An updated review. J Environ Sci (China) 2017, 58, 64–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qiu, T.; Shi, W.; Chen, J.; Li, J. Haloketones: A class of unregulated priority DBPs with high contribution to drinking water cytotoxicity. Water Res. 2024, 259, 121866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- countries where regulations

explicitly permit and regulate seawater use;

- countries where regulations

explicitly permit and regulate seawater use;  - countries where regulations indirectly mention seawater use;

- countries where regulations indirectly mention seawater use;  -

countries where seawater use is neither expressly regulated nor forbidden;

-

countries where seawater use is neither expressly regulated nor forbidden;  -

countries where regulations allow the seawater use but explicitly delegate

governance to regional legislation;

-

countries where regulations allow the seawater use but explicitly delegate

governance to regional legislation;  - countries whose legislation allows the

use of seawater in some facilities, without specifying its quality criteria;

- countries whose legislation allows the

use of seawater in some facilities, without specifying its quality criteria;  -

countries whose regulations have not been examined.

-

countries whose regulations have not been examined.

- countries where regulations

explicitly permit and regulate seawater use;

- countries where regulations

explicitly permit and regulate seawater use;  - countries where regulations indirectly mention seawater use;

- countries where regulations indirectly mention seawater use;  -

countries where seawater use is neither expressly regulated nor forbidden;

-

countries where seawater use is neither expressly regulated nor forbidden;  -

countries where regulations allow the seawater use but explicitly delegate

governance to regional legislation;

-

countries where regulations allow the seawater use but explicitly delegate

governance to regional legislation;  - countries whose legislation allows the

use of seawater in some facilities, without specifying its quality criteria;

- countries whose legislation allows the

use of seawater in some facilities, without specifying its quality criteria;  -

countries whose regulations have not been examined.

-

countries whose regulations have not been examined.

| Country | Regulation | Scope of application | Permitted type of fill water | Ref. |

| France | • Public Health Code. Part 1. Book III. Title III. Chapter II: Swimming pools and bathing areas. Articles D1332-1 - D1332-54. | Applies to public/collective swimming pools. Does not apply, except for disinfection provisions, to thermal SPs supplied by natural mineral water used for therapeutic purposes in thermal facilities. | Water from a public distribution network or from water taken from the natural environment, seawater included, after authorization. | [31] |

| • Decree of 26 May 2021 on swimming pool water quality standards and reference values, pursuant to Article D.1332-2 of the Public Health Code (PHC). | [32] | |||

| • Order of 26 May 2021 on the use of non-potable water sources for supplying swimming pools, pursuant to articles D. 1332-4 and D. 1332-10 of the PHC. | [33] | |||

| • Decree No. 81-324 of 7 April 1981 on the hygiene and safety standards for swimming pools and designated bathing areas. | [75] | |||

| • Order of 26 May 2021 amending the Decree of 7 April 1981 on technical provisions applied to swimming pools. | [76] | |||

| Germany | • Infection Protection Act (IfSG). § 37. Quality of water for human consumption and for swimming or bathing in pools or ponds, monitoring. | Apply to public baths, commercial, other non-private-use swimming facilities. Does not apply to private baths; systems with biological water treatment, water playgrounds, floating systems and/or pools; discontinuous water treatments | [35] | |

| • DIN 19643-1:2023-06. Part 1. | Water, including sea, mineral, medicinal, artificially produced brine and thermal water | [36] | ||

| • DIN 19643-2:2023-06. Part 2. | [77] | |||

| • DIN 19643-3:2023-06. Part 3. | [78] | |||

| • DIN 19643-4:2023-06. Part 4. | [79] | |||

| • DIN 19643-5:2021. Part 5. | [80] | |||

| Slovenia | Rules on minimum hygiene requirements that must be met by swimming pools and bathing water in pools. | Apply to bathing areas and water in conventional and biological SPs. Do not apply to natural bathing areas and SPs used by individuals or their family | Freshwater and seawater | [37] |

| Croatia | Rules on sanitary, technical and hygienic conditions of swimming pools and on the health safety of swimming pool waters. No. 1186. | Do not apply to non-public SPs; SPs with medically indicated, therapeutic water (e.g., thermal) not disinfected with residual effect; saunas and hot tubs in which the water is used once; lagoons, flow pools and seawater water slides. | Filling water from a public water supply system, seawater, or other types. | [38] |

| Poland | • Disposal of the Minister of Health of 9 November 2015 on water quality requirements for swimming pools. Amended on 10.05.2022, Item 1230. | Does not apply to swimming pools in which the pool basins are filled with water with medicinal properties. | Freshwater (surface or groundwater) meeting the drinking water requirements, Salty (i.e. sea and brine water) with 5-15 g/L of mineral content, Thermal, with outlet temperature ≥ 20 °C (excluding mine drainage water). |

[34] |

| • Act of 18 August 2011 on the safety of persons staying in water areas. | [81] | |||

| Lithuania | • Hygiene standard HN 109:2016 “Public Health Safety requirements for swimming pools”. | Not specified | Freshwater for pools must meet drinking water quality requirements before use. Mineral and seawater used to supply SPs must meet HN 127:2010 standard before use. |

[39] |

| • Hygiene standard HN 127:2010 “Mineral and seawater for external use. Health safety requirements”. | [40] | |||

| Latvia | Regulation No. 470 “Hygiene requirements for pool and sauna services”. | Pools or saunas, including those in educational, social care, healthcare institutions, sports, entertainment or recreation facilities, and hotels. | Potable water with the mandatory safety requirements for drinking water, sea or mineral water. | [41] |

| Romania | •Order No. 994 of 9 August 2018, amending and supplementing the Public Hygiene and Health Norms No. 119/2014 on the population’s living environment. | Public swimming pools | Drinking or sea water. Filling water not coming from public drinking water network, must comply with legal provisions. | [42] |

| Rules of 4 February 2014 on hygiene and public health for the population’s living environment. Annex I. | For freshwater | [82] | ||

| Decision No. 546 of 21 May 2008 on the management of bathing water quality. Annex I.. | For seawater | [83] | ||

| Spain | Royal Decree 742/2013 of 27 September, establishing the technical and health criteria for swimming pools. | Applies to public SPs. Single-family private SPs and SPs in homeowners’ associations, agrotourism’s, colleges or similar must comply with some provisions of this Decree. Does not apply to natural, thermal or mineral-medicinal pools. | Contains a request to provide periodic reports to the Ministry of Health with basic information on sources of filling water in SPs, which may include public and non-public networks or seawater. | [43] |

| Law 14/1986 of 25 April, General Health Law. BOE-A-1986-10499. | [84] | |||

| Portugal | NP 4542:2017 | Public swimming pools | Water from a public water network. Alternative water sources use requires the authorizations | [44] |

| Circular-Normative No. 14/DA. | Public/semipublic swimming pools | [46] | ||

| CNQ Directive No. 23/93 | Applies to public SPs and aquatic recreational facilities. Does not apply to therapeutic or thermal facilities, SPs used by families or in condominiums with less of 20 units | Mention seawater use | [45] | |

| Finland | Instructions for the application of the swimming pool water regulation: Swimming pool water quality and monitoring. 2/2017. | Apply to public SPs and spas. Do not apply to residential SPs, SPs in which the water is changed after each use, hotels jacuzzi self-filled by users, wading pools without continuous water treatment, portable SPs and rented by customer’s hot tubs. | Nor specified | [30] |

| Health Protection Act 763/1994. 19.8.1994. | [49] | |||

| Decree “On the quality requirements and monitoring studies of pool water in swimming pools and spas” 315/2002. | Applies to public SPs; spa; water parks; recreation and rehabilitation facilities. | Mention filling water rich of bromine | [50] | |

| Sweden | Guidance on swimming pools. No. 23048. | Applies to public SPs, i.e. pools and tubs for swimming, which can be part of pools such as indoor SPs, spas and water parks, or be independent both outdoors and indoors. | Nor specified | [47] |

| General Advice on swimming pools. HSLF-FS 2021:11. | [48] | |||

| Environmental Code. 1988:808 | [85] | |||

| Denmark | Executive Order on swimming pool facilities and their water quality. BEK No. 918. |

Applies to public and hot water SPs, i.e. spas, water parks, recreational, therapy and treatment pools and similar. Does not apply to private SPs, paddling pools where the water is discarded after a few hours, steam, thermal baths and similar. | Potable water and surface water (seawater included) | [52] |

| Guidance on controlling swimming pools. VEJ No. 9605. | [51] | |||

| Environmental Protection Act. LBK No. 1093. |

[86] | |||

| Norway | Regulation of 13 June 1996 on bathing facilities, swimming pools and saunas, etc. | Covers all public SPs, bathing facilities and saunas | Filling water must be hygienically satisfactory | [53] |

| Public Health Act. No. 29. | [87] | |||

| Regulation No. 486 on environmental health protection. | [88] | |||

| Netherlands | Environmental Activities Decision (Bal). Chapter 15. | Does not apply to household SPs, SPs installed for up to 24 consecutive hours, intended for human-animal contact, or installed on vessels not permanently moored. | Water that meets the quality requirements for drinking water. | [54] |

| Environment and Planning Act. | [55] | |||

| Belgium Flanders |

Title II of VLAREM. Government Decree of 1 June 1995 containing general and sectoral provisions regarding environmental hygiene. Art. 5.32.8.1. | Applies to permanent and natural SPs, hot tubes, plunge, splash and therapy pools, open swimming areas, recreation zones. Does not apply to private and hotels SPs not open to the public, which must comply with the provisions on the water treatment and the chemicals storage | Freshwater or salt water | [29] |

| Belgium Walloon |

Government Order of 13 June 2013 determining full conditions for indoor and outdoor swimming pools used for a purpose other than purely private within the family circle. | Applies to indoor and outdoor SPs used non-privately within the family, when the surface area ≤ 100 m² or the depth is ≤ 40 cm, with chlorine used for disinfection | Drinking water from the distribution network. If the filling and supplementary water do not come from the network, it meets the tap water standards | [56] |

| Belgium Brussels-Capital Region |

Government Order of 16 February 2023 setting operating conditions for swimming pools and other baths. | Apply to SPs and other baths listed in Annex 1 of [83]: excluding domestic SPs with a pool area ≤ 200 m2, other bathing facilities, SPs with a pool area over 200 m2. Does not apply to SPs and other baths with alternative water treatment other than chemical disinfection or biological treatment. | Drinking water from distribution network. When supplied water is not coming from the drinking water distribution network, authorization or environmental permit are requested | [57] |

| Government Order of 4 March 1999 listing class IB, [IC, ID], II and III installations, issued under Article 4 of the 5 June 1997 Environmental Permits Ordinance. | [89] | |||

| Italy | State-Regions Agreement of 16 January 2003 on the health and hygiene aspects for the construction, maintenance and supervision of swimming pools. | Applies to public/collective SPs for swimming, training, diving, underwater, recreational activities, for children, multipurpose use. Does not apply to SPs for rehabilitation, curative and thermal use. The systems supplied with thermal and seawater to be regulated by specific regional provisions. | Freshwater (surface or underground) that meets the requirements of potability. If the supply water does not come from a public aqueduct, it is necessary to verify its suitability for human consumption. | [58] |

| Interregional Regulation on swimming pools of 22 June 2004. | [59] | |||

| Guidelines for the reopening of economic and productive activities. 11 June 2020. | Mention seawater use | [64] | ||

| Albania | Regulation “Hygienic and sanitary requirements for swimming pools”. No. 835. | Apply to public/collective SPs for competition, training, diving, underwater activities, recreational, multifunctional and children use, in the hotels, tourist complexes/villages, colleges, schools, universities, gyms, beauty salons, residence complexes with over 4 units. Does not apply to private SPs, residence complexes with up to 4 units, thermal and therapeutic SP. | Potable water. If the water supply is not provided by the water supply company, the water must be tested seasonally for the parameters for assessing the suitability of drinking water. |

[65] |

| Greece | Sanitary Order Γ1/443/1973 “On swimming pools with instructions for their construction and operation”. Amended by Decrees: Γ4/1150/1976, ΔΥΓ2 /80825/05.2006. | Public swimming pools | [66] | |

| Circular Εγκ. ΔΥΓ2/99932/06/2007 “Instructions for the implementation of the Health Provisions “On the operation of swimming pools”. | SPs supply with seawater does not contradict the provisions if the water quality meets the parameters specified in Art.15 of [66] | [67] | ||

| Law 5170/2025 “Establishment of specifications for short-term rental properties and other urgent provisions”. | [68] | |||

| Circular Δ1δ/ΓΠ.οικ. 57290/2019 “On protection of public health through safe operation of public swimming pools”. | [90] | |||

| Circular Εγκ. Δ1α,δ/ ΓΠ οικ. 23849/2024 “Measures to protect public health from Legionnaires’ disease”. | [91] | |||

| Bulgaria | Instruction No. 34 on hygiene of sports facilities and equipment. Amended on: 02.03.1984, 08.03.2002. | Applies to the facilities where sports competitions and training are held | Not specified | [69] |

| Estonia | Health protection requirements for swimming pools, pools and aquatic centres. No. 80 of March 15, 2007. Amended on: 10.12.2009, 19.08.2011 |

Applies to SPs, pools and aquatic centres, in public and private legal entities providing services related to swimming and bathing, including schools and preschool institutions. Do not apply to natural mineral water and hydrotherapy SPs, natural cold-water pools, bathing facilities with flow-through surface water. |

Water used in SP must meet the requirements established for drinking water. | [70] |

| Malta | Public Health Act “Swimming Pools Regulations, 2005”. L.N. 129. Amended by L.N. 135 of 2008. | Applies to public or commercial SPs, including artificial basins, for recreational bathing, swimming, diving, or therapeutic use, located indoors or outdoors. Does not apply to non-public or non-commercial SPs. | Controlled water supply. | [71] |

| Subsidiary Legislation 545.07 on Control of swimming pools regulations. 5 June 1998, amended by: L.N. 107 of 2009; XXV. 2015.41 |

SPs located more than 100 meters from the sea may be filled only with freshwater collected as surface run-off or from public supply network. SPs within 100 m of the sea may be filled by seawater, only if the pool water is discharged to the sea through waterproof pipes |

[72] | ||

| Cyprus | Public Swimming Pools Regulations 368/96. | Applies to SPs: pools used exclusively or principally for the conduct of competitions or for the training or education of athletes; indoor SPs located within an enclosed covered area; public swimming pools. | Filling water should be chemically and microbiologically suitable. Authorities may allow brackish water use for tanks and sanitary facilities. Water renewal from a safe non-chlorinated natural source is allowed with at least 2000 liters per bather. | [73] |

| Public Swimming Pools Laws of 1992 and 1996 (55(I)/1992 and 105(I)/1996). | [74] |

| Parameter | Freshwater pools | Seawater pools | Ref. | Reference values | Ref. | |||||||

| Country | RV | QL | Note | |||||||||

| THMs, μg/L | ||||||||||||

| Total THMs (4TTHM) | 7–577 | [6] | France | 20 | 100 | The lowest possible value should be achieved without compromising disinfection efficacy | [32] | |||||

| 80.2 | 50.4–91.8 | [7] | ||||||||||

| 51.8-105.8 | [9] | Portugal | 100 | [46] | ||||||||

| 16.8-29.4 | [10] | Germany | 20 | For indoor pools. In outdoor SPs higher QL is permitted. (*Calculated as chloroform) | [36] | |||||||

| 77.7- 995.6 | [11] | Slovenia | 50 | [37] | ||||||||

| 307.6-327.8 | [13] | Poland | 100 | SPs feed with fresh, sea and thermal water | [34] | |||||||

| 122.4-435.5 | [23] | Sweden | 100 | [48] | ||||||||

| 777 | 260-322 | [100] | Denmark | 25 50 |

-Indoor SPs with T ≤ 34°C, -SPs with T > 34°C, outdoor SPs, hot tubs |

[52] | ||||||

| Netherlands | 50 | Calculated as chloroform | [54] | |||||||||

| Croatia | 100 | For conventional pools | [38] | |||||||||

| Chloroform | 0.2–243 | 0.1-6 | [6] | Poland |

20 30 |

SPs feed with fresh, sea and thermal water: -SPs for children up to 3 years old, -Other swimming pools |

[34] | |||||

| 69.8 | N.D. | [7,9] | ||||||||||

| 0.1 (mean)- 0.9 (max) | [8] | |||||||||||

| Finland | 50 | Not applicable to outdoor pools | [30] | |||||||||

| 0.01-0.29 | [11] | Lithuania | 100 | If chlorine-based compounds are used for disinfection | [39] | |||||||

| Bromodichloromethane | 0.13-167 | 0.29-5 | [6] | |||||||||

| 7.9 | N.D. | [7,9] | ||||||||||

| 0.3 (mean) - 2.2 (max) | [8] | |||||||||||

| 0.05-1.10 | [11] | |||||||||||

| Dibromochloromethane | 0.49-120 | 3.57–27 | [6] | |||||||||

| 1.9 | 1.6-5.2 | [7] | ||||||||||

| 18.9 (mean) - 81.0 (max) | [8] | |||||||||||

| 2.1– 5.5 | [9] | |||||||||||

| 3.2-63.6 | [11] | |||||||||||

| Bromoform | 0.04-47 | 50-651 | [6] | |||||||||

| 0.6 | 48.9-86.7 | [7] | ||||||||||

| 300 (mean) - 1029 (max) | [8] |

|||||||||||

| 49.7–101.3 | [9] | |||||||||||

| 73.5-930.7 | [11] | |||||||||||

| Inorganic anions, mg/L | ||||||||||||

| Bromate | 3 | <0.2-34 | [6] | Germany | 2 | [36] | ||||||

| < 0.02-5.0 | [22] | Netherlands | 0.1 | [54] | ||||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).