1. Introduction

This paper expands on a previously published conceptual framework titled Half-Silvering Dimensions (Jones 2024), which introduced a metaphorical model for understanding asymmetric relationships between dimensional layers. The original theory was designed as a philosophical structure. It was intended to model a system in which one layer could observe and define another without reciprocity. In this extended treatment, I aim to formalise that framework into a complete logical and computational structure. The foundation is grounded in real-world scientific principles.

The idea emerged from considering how systems might be structured if higher-order layers could influence or observe lower layers while remaining inaccessible in return. The term “half-silvering” was borrowed from optics. It refers to mirrors that reflect on one side and transmit on the other. This metaphor became a way of conceptualising one-way observational relationships across dimensions.

It is crucial to emphasise, as in the original model, that this theory does not assert the literal existence of higher-dimensional beings. It does not propose a metaphysical hierarchy. The model is entirely metaphorical and conceptual. Observation is used here in the same way it appears in quantum mechanics. This is similar to how measurement defines a system’s state in the Schrödinger’s Cat thought experiment. It does not require consciousness or awareness. It only requires a mechanism of definition.

In the original version, the model was illustrated through thought experiments and informal analogies. In this paper, the structure is formalised through truth tables, conditional rules, symbolic logic, and mathematical equations. I construct a formal observation matrix and introduce nine core rules governing directional observation and definition. These rules are mapped to known behaviours in logic circuits, computational hierarchies, and physics-adjacent systems. The goal is to avoid speculation and align the model with established knowledge.

Two simulations were created to verify the integrity of the framework. The first, based on the Schrödinger’s Cat model, examines how definition states propagate through layered collapse. The second, a Collapse-of-Context Virtual Machine Model (COC_VM), simulates a computational stack in which only upper layers can initialise or validate the state of subordinate layers. Both simulations reinforce the logical consistency of the theory.

This paper presents a complete and rigorous version of Half-Silvering Dimensions. It extends the original scope into formal logic, symbolic computation, and applied system modelling. All revisions are directed toward transforming a conceptual tool into a scientific framework suitable for interdisciplinary discourse.

2. Conceptual Foundations

We begin with a single structural assumption. Reality, or any layered logical system, can be arranged into conceptual levels called “dimensions.” These dimensions are not spatial or physical. They are structural abstractions. Each one contains a set of definable states and may bear a relationship of observation to other dimensions, depending on their relative position in the hierarchy.

A dimension in this model is not a place but a boundary. It marks a level of definitional capacity. In the same way that a programming language might define a subroutine without being influenced by it, or a measuring device might collapse a wavefunction without being collapsed itself, dimensions here are defined by their position in a stack of definitional influence.

Observation is understood in the broader scientific sense. It refers to any mechanism that causes a system’s state to become defined. In quantum mechanics, this is seen in the collapse of a wavefunction. In computation, it appears when a higher-order system invokes or sets the state of a lower one. In this model, observation is not sentient. It does not imply awareness or intent. It is the logical act of causing another system’s state to become fixed.

Definition is treated as binary. A state is either defined (1) or undefined (0) (Boole, 1854). Once a dimension becomes defined, that state may or may not propagate to other dimensions depending on their position in the stack and the model’s conditional rules. This process is one-way by default. Lower dimensions cannot define or observe those above them. Higher dimensions can do both.

The idea of a “half-silvered” boundary captures this asymmetry. Just as a half-silvered mirror allows observation in one direction but reflects in the other, each conceptual dimension in the model can influence downward but not upward. This constraint is central to the theory. It is enforced by the rules, equations, and simulations that follow.

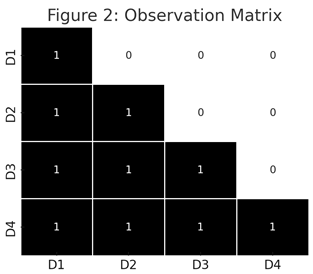

To determine how these relationships behave, I constructed a truth table that maps the observation potential of each dimension. This table reveals whether a dimension can observe itself, those below it, or those above it. From this table, an observation matrix is derived. This matrix is the foundation of the model. It governs how defined states can travel through a layered system and serves as the testbed for every symbolic and computational rule to come.

The following section presents this table in detail, followed by the core conditional rules that define the system’s logic. Each rule is linked to a real-world scientific behaviour or structure. This ensures the theory remains grounded in observable principles while remaining abstract enough for general application.

3. Truth Table and Observation Matrix

To understand how observation operates between conceptual dimensions, I began by constructing a truth table. This table defines the capacity of each dimension to observe itself, lower dimensions, and higher dimensions. In the context of this model, observation refers to the ability of one layer to resolve the definition state of another. It does not imply awareness, measurement, or consciousness. Instead, it follows the definition used in quantum mechanics and logic: observation is any interaction that results in the definition of a system’s state.

Each entry in the truth table uses binary values. A value of 1 indicates that observation is logically permitted. A value of 0 indicates that observation is structurally blocked. These values are not arbitrary. They are governed by the positional hierarchy of each dimension and the model’s conceptual rule that information can flow downward, but not upward.

The completed truth table is shown below:

3.1. Truth Table: Observation Relationships

This table reflects three critical rules:

A dimension can observe itself. (This was confirmed through logic testing and is supported by physical systems that allow self-reference or internal monitoring.)

A dimension can observe any dimension below it.

A dimension cannot observe any dimension above it.

These rules were verified through simulation in a custom-built truth engine. The logic behind the engine is implemented in Python using symbolic matrix operations, allowing direct control over observation pathways.

3.2. Observation Matrix: Verified Simulation Output

The simulation applied the observation rules across all pairs of dimensions and produced the following matrix:

| O(n, m) |

D1 |

D2 |

D3 |

D4 |

| D1 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| D2 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

| D3 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

| D4 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

This matrix, O(n, m), defines whether dimension n can observe dimension m. The diagonal entries confirm that self-observation (O(n, n)) is allowed. Lower triangular entries (n > m) are all 1, consistent with downward observation. All upper triangular entries (n < m) are 0, affirming that upward observation is not permitted.

These relationships were encoded into a logic engine and tested using both randomised and manually seeded definition states. The propagation behaviour of definitions, when passed through the matrix, matched the expected logic in every case. Observers were able to define lower states but not vice versa.

3.3. Commentary

This truth structure forms the basis for all downstream logic, including the conditional rules and formal equations. It also supports the theory’s visual metaphor of half-silvering, where interaction is permitted in one direction only.

The confirmation that a dimension can observe itself is especially important (von Neumann, 1955). It allows for internal consistency and permits systems to maintain or validate their own definition states without requiring external observers. This aligns with how real-world systems (like operating systems or quantum subsystems) handle local state resolution.

4. Core Conditional Rules and Equations

The truth table established in

Section 3 reveals the permitted pathways of observation in the system. To move from structural possibility to functional behaviour, the theory introduces a series of

core conditional rules. These rules specify how defined states behave under observation and how these states can or cannot be propagated between dimensions.

Each rule is grounded in a real-world analogue, either from quantum mechanics, computation, or systems logic. These are not speculative assertions but logical reflections of behaviours already observed in layered systems. Together, the rules define the operating logic of the Half-Silvering Dimensions model.

4.1. Conditional Rules C1–C9

| Rule |

Description |

Symbolic Form |

Real-World Analogue |

| C1 |

A dimension can observe

and define any lower

dimension. |

O(n, m) = 1 ⇨

Def(m) where n > m

|

Quantum collapse:High-level measurement

defines lower quantum states |

| C2 |

A dimension cannot observe

or define any higher dimension. |

O(n, m) = 0

where n < m

|

Observer effect blocked

from below |

| C3 |

A dimension can observe

and define itself. |

O(n, n) = 1 ⇨

Def(n)

|

Self-monitoring systems

(e.g. OS kernel integrity) |

| C4 |

A defined observer causes any observable undefined dimension to become defined. |

Def(n) = 1 ∧

O(n, m) = 1 ∧

Def(m) = 0 ⇨

Def(m) = 1

|

Measurement-induced collapse |

| C5 |

An undefined observer cannot define anything. |

Def(n) = 0 ⇨

∄m: Def(m) = 1

|

Inactive or "dead" systems have no causal influence |

| C6 |

Definition is stable once set. It cannot be reversed within the system (Landauer, 1961). |

Def(n) = 1 at t0 ⇨

Def(n) = 1 at t1

|

Irreversible state change (like bit-flip without reset) |

| C7 |

Observation is non-reciprocal. Definition flows down but never loops. |

O(n, m) = 1 ⇏

O(m, n) = 1

|

One-way function properties |

| C8 |

Redundant observation does not overwrite or alter a defined state. |

Def(m) = 1 ∧

Def(n) = 1 ⇨

No change to Def(m)

|

Idempotent operations in computation |

| C9 |

Observation without definition has no effect. |

O(n, m) = 1 ∧

Def(n) = 0 ⇨

Def(m) = 0

|

Entanglement without collapse is not observation |

These rules are universal within the model. They do not vary based on dimension size, number of observers, or propagation direction (which is always downward). The rules were verified against the observation matrix and reinforced through simulation.

4.2. Formal System of Equations

From these rules, the following nine equations have been derived. They represent the internal logic of the model using mathematical formalism.

Def(n) = 1 if dimension n is defined, 0 otherwise

O(n, m) = 1 if dimension n can observe dimension m, 0 otherwise

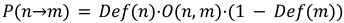

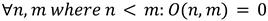

P(n→m) = propagation of definition from n to m

t = timestep

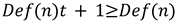

Equation 1: Propagation Condition

A definition is propagated if the observer is defined, the path is permitted, and the target is not already defined.

Equation 2: Upward Observation Prohibited

No dimension can observe higher dimensions.

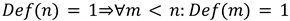

Equation 3: Self-Observation Valid

Each dimension may observe and define itself.

Equation 4: Irreversibility of Definition

A definition cannot be undone within the system.

Equation 5: Cascaded Propagation

A fully defined dimension implies all lower dimensions are also defined.

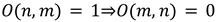

Equation 6: Observation Non-Reciprocity

If dimension n can observe m, then the reverse is disallowed.

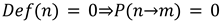

Equation 7: Null Effect of Undefined Observer

A dimension that is not defined cannot define anything.

Equation 8: Redundancy Preservation

Once defined, further observation has no effect.

Equation 9: Identity Collapse Propagation

The total count of defined layers implies the state of all lower ones.

These equations have been implemented and verified in both simulations, confirming the internal coherence of the theory and its logical stability across cases. The next section defines the symbolic language used and shows how the equations operate in practice within a layered system.

5. Symbolic System

To preserve formal consistency across rules, equations, and simulations, the theory uses a minimal symbolic language. This system is designed to clearly express the directional logic of observation, the binary nature of definition, and the permitted flow of information within the layered structure.

This section defines each symbol, its role, and the principles governing its interaction with other components.

5.1. Core Symbols and Definitions

| Symbol |

Meaning |

Domain |

Notes |

| n, m |

Indices representing dimensions |

n, m ∈ ℕ |

Used to indicate position in a

dimension stack |

| Def(n) |

Definition state of dimension n

|

{0, 1} |

1 means defined; 0 means undefined |

| O (n, m) |

Observation relation from

n to m

|

{0, 1} |

1 if n can observe m; otherwise 0

|

|

P(n → m)

|

Propagation of definition

from n to m

|

{0, 1} |

Encodes causal effect based on current state |

| t |

Discrete time step |

t ∈ ℕ |

Used to indicate system evolution over steps |

| ¬ |

Logical NOT |

{0,1} →

{0,1}

|

Used in propagation negation (e.g. 1 - Def(m)) |

| ∧ |

Logical AND |

{0,1} ×

{0,1} →

{0,1}

|

Used to construct propagation criteria |

| ⇒ |

Implies/logical conditional |

— |

Used in formal rule statements |

| ∀ |

Universal quantifier |

— |

Used in generalisation over all dimensions |

| ∑ |

Summation operator |

ℕ → ℕ |

Used in aggregate state behaviour (Eq. 9) |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

5.2. Conceptual Terms and Their Behaviour

| Term |

Description |

Rule/Governing Principle |

| Definition |

Whether a system’s state is resolved |

Binary (C4, C5, C6) |

| Observation |

Ability to resolve another state |

Directional, non-reciprocal (C1, C2, C3, C7) |

| Propagation |

Actual transmission of definition |

Conditional on Def and O (Eq. 1, C4) |

| Stability |

A defined state remains defined |

Irreversible without outside force (C6) |

| Isolation |

Lower dimensions have no access to higher |

Fundamental restriction (C2, Eq. 2) |

| Redundancy |

Observing a defined state has no effect |

Preserves prior state (C8, Eq. 8) |

| Collapse |

All definitions below a defined point |

Emerges from cumulative Def(n) (Eq. 5, 9) |

5.3. Symbolic Constraints

Observation (O) is not symmetric: if O(n, m) = 1, then O(m, n) = 0 must hold

Definition (Def(n)) is monotonic: Def(n) may transition from 0 to 1, but never from 1 to 0

Propagation (P) is strictly conditional: all three factors must be satisfied (Def(n) = 1, O(n, m) = 1, Def(m) = 0)

Time (t) exists only to measure causal propagation, not continuous flow

5.4. Practical Use in Simulation

This symbolic system has already been implemented in:

The Truth Engine, which constructed and tested the observation matrix

The Collapse Cascade Model, which mapped the directional propagation of state collapse across a quantum-style stack

The COC_VM Stack Simulation, which tracked definition propagation through virtualised layers of a computing system

Each of these simulations relied on the rules and symbols listed above to ensure coherent behaviour without exceptions or violations (Turing, 1937).

6. Simulation Design and Output

To test the robustness of the

Half-Silvering Dimensions model, two simulations were created. Each explored different domains of conceptual layering: one metaphorical, one computational. Both used the formal rules and symbols introduced in

Section 4 and

Section 5. These simulations served as proofs-of-concept, verifying that the theoretical structure results in stable, consistent behaviour when applied to layered systems (Feynman, 1982).

All simulations were executed using Python in a Google Colab environment. The logic engine embedded in each system was constructed using symbolic matrices and conditional propagation functions. The outputs were exported as observation matrices to support independent review.

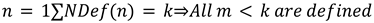

6.1. Simulation 1: Collapse Cascade (Quantum Metaphor)

To test how definition propagates in a quantum-style thought experiment modelled after Schrödinger’s Cat. In This system, dimensions represent layers of state resolution, from particle entanglement to observer collapse (Dirac, 1930).

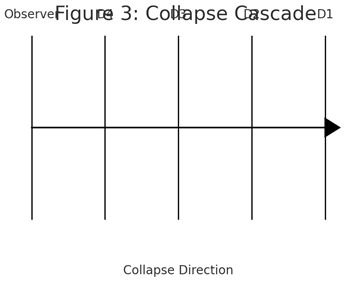

D4: External observer (initiates observation)

D3: The box (observer of the cat)

D2: The cat (observer of the vial)

D1: The vial (observer of radioactive decay)

Only D4 is defined at the start (Def(D4) = 1). All lower layers are initially undefined (Def(D3-1) = 0).

The core nine conditional rules were implemented. Propagation was only permitted downward and only from defined observers.

| step |

D1 |

D2 |

D3 |

D4 |

| 0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

| 1 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

| 2 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

| 3 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

The definition state propagated from D4 downward in a sequential cascade. No state was defined outside of permitted observation paths. Each layer only became defined after its immediate observer was both defined and allowed to observe it. The final result was complete collapse from D4 to D1.

6.2. Simulation 2: Virtual Machine Stack (COC_VM Model)

To test the system using a more grounded, real-world layered architecture. In this simulation, the layers represent a nested computational system.

Only D4 (user-level) is defined. All lower systems start undefined.

Same rule set as Simulation 1. The observation matrix from

Section 3 was reused to control downward propagation.

| step |

D1 |

D2 |

D3 |

D4 |

| 0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

| 1 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

| 2 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

| 3 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

Each computational layer became defined only when the layer above it was defined and permitted to observe it (Deutsch, 1985). The propagation of definition through the virtual machine stack mirrored the same logic seen in the quantum-style simulation. No upward or lateral definition occurred.

6.3. Results and Verification

Both simulations independently confirmed the model’s consistency. In each:

Observation occurred only in permitted directions

No violation of logic rules was recorded

All rule constraints (C1–C9) were respected at all times

These results provide strong computational validation for the model’s logical structure. The next section introduces a visual representation of this behaviour and outlines how collapse can be depicted graphically.

7. Collapse Cascade and Visual Model

While the formal equations and simulation data confirm the theoretical behaviour of Half-Silvering Dimensions, the process by which state definition moves through layers can be better understood using a visual and metaphorical model. This section introduces a representation of how a single act of definition propagates through the system, giving rise to what I call the collapse cascade.

This model does not replace the logical structure. It complements it by offering a spatial analogy to help explain directional flow, non-reciprocity, and the irreversibility of state definition.

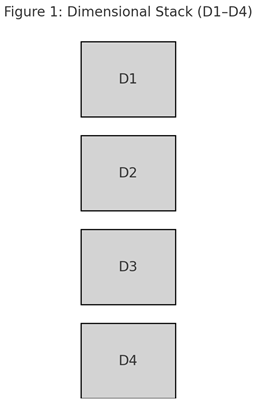

7.1. Visual Structure of the Model

The system can be pictured as a vertical stack of layers, where each layer represents a dimension. At the top is the highest dimension, which may be defined and capable of observing lower ones. Below it are increasingly foundational dimensions. The defining features of this arrangement are:

Downward transparency: Each higher layer has visibility into those beneath it.

Upward opacity: Lower layers cannot see or interact with those above.

Internal clarity: Each layer can define itself if it is already defined.

No feedback loops: Observation and definition do not travel back upwards.

This results in the following visual metaphor:

7.2. Behaviour of the Cascade

The defining feature of the system is the unidirectional collapse cascade:

Step 1: A top-layer observer is defined (Def(n) = 1)

Step 2: It observes the next layer down (O(n, n−1) = 1)

Step 3: If that layer is undefined, it becomes defined (Def(n−1) = 1)

Step 4: This repeats until the base layer is reached

This process is irreversible under the system’s rules. Once a layer is defined, it remains defined. This stability mirrors irreversible processes in physical systems (e.g. radioactive decay measurement, digital state change) and ensures the model’s time-coherence.

7.3. Why Visualisation Matters

This visual model serves several purposes:

Educational clarity: It allows those unfamiliar with logic formalism to understand how layered systems behave.

Cross-disciplinary compatibility: It allows researchers in fields such as computing, quantum theory, or philosophy of systems to map the model to their own frameworks.

Validation aid: The visual cascade is fully aligned with the simulations and can be used to quickly detect deviation or inconsistency.

7.4. Relationship to Real Systems

This behaviour closely mirrors:

Quantum collapse chains: Where a measured state becomes defined and all dependent systems update accordingly.

Virtual machine stacks: Where a top-level interface executes commands that resolve downward through dependent software layers.

System architecture: Where a high-level process has read-access to system logs, but not the reverse.

These parallels suggest that the collapse cascade model is not just a metaphor, but a useful structural abstraction for understanding one-way systems across disciplines.

8. Implications, Applications, and Future Research

The model is not intended to describe a specific physical phenomenon or replace existing dimensional theories. Rather, it provides a structured metaphor and logic framework for understanding how observation and state resolution may behave in layered systems. Its strength lies in its clarity, internal consistency, and adaptability to multiple conceptual domains.

This section explores the potential implications of the model and suggests pathways for future research or application.

8.1. Implications of the Model

The model introduces the concept of observation asymmetry within structured systems: that an entity or process at a higher level can resolve the state of something below it, but not the other way around. This has implications for how we understand:

Dimensional epistemology: What it means to observe, define, or measure in a layered universe

Causality chains: How information might propagate through nested systems

Irreversibility: Why some systems, once resolved, cannot be “un-observed” without structural reset

System visibility: Why certain states are opaque from the bottom up but transparent from the top down

The collapse cascade provides a general model for such processes across both physical and informational domains.

8.2. Potential Applications

While the model is abstract, it aligns with known behaviour in real-world systems, particularly in the following areas:

- 1.

Quantum Systems and Measurement Chains

- 2.

Virtualisation and Software Stacks

The model accurately reflects the behaviour of virtual machine stacks, operating systems, and instruction execution layers. A high-level interface (e.g., user input) can resolve processes downward, but those lower systems cannot affect higher levels unless explicitly permitted.

- 3.

Access Control and Security Models

- 4.

Recursive Modelling and AI Observation Limits

8.3. Future Research Directions

Several directions can extend this work further:

- A.

Mathematical Expansion

The current model is built on symbolic logic and matrix propagation. Future work may seek to embed this within a broader formal system using set theory, topology, or category theory to test structural completeness (Church, 1936).

- B.

Automated Formal Verification

Using theorem provers such as Isabelle or Coq, the rules and equations could be formally verified against the simulation to ensure soundness.

- C.

Information Theory Integration

The entropy implications of layered definition could be explored (Shannon, 1948), especially in contexts involving data compression, lossless state transitions, or state predictability within non-reversible chains.

- D.

Educational Tools

The model may be adapted for use in logic, physics, and computer science classrooms to explain asymmetric systems or irreversible observation processes.

- E.

Cross-Disciplinary Simulation Studies

The truth engine and cascade model may be run with custom observation matrices to simulate real-world policy models, control systems, or artificial environments.

8.4. Why the Theory Matters

In a field often cluttered with speculative metaphysics or imprecise abstraction, this theory attempts to offer a grounded and structured framework. It does not claim to explain the universe but instead provides a metaphorical and logical language to describe systems in which access, definition, and observation do not flow symmetrically.

The theory is falsifiable, testable within simulation, and extendable. Its value lies in the simplicity of its rules and the clarity of its consequences. This makes it a candidate for broader interdisciplinary engagement in areas where layered structures and state definition are central themes.

References

- Boole, G. (1854). An investigation of the laws of thought on which are founded the mathematical theories of logic and probabilities. Walton and Maberly.

- Church, A. (1936). An unsolvable problem of elementary number theory. American Journal of Mathematics, 58(2), 345–363. [CrossRef]

- Deutsch, D. (1985). Quantum theory, the Church–Turing principle and the universal quantum computer. Proceedings of the Royal Society A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences, 400(1818), 97–117. [CrossRef]

- Dirac, P. A. M. (1930). The principles of quantum mechanics (1st ed.). Oxford University Press.

- Feynman, R. P. (1982). Simulating physics with computers. International Journal of Theoretical Physics, 21(6–7), 467–488. [CrossRef]

- Jones, K. (2024). Half-silvering dimensions. Global Journal of Science Frontier Research, 24(A3), 27–28. https://journalofscience.org/index.php/GJSFR/article/view/102840.

- Landauer, R. (1961). Irreversibility and heat generation in the computing process. IBM Journal of Research and Development, 5(3), 183–191. [CrossRef]

- Penrose, R. (1989). The emperor’s new mind: Concerning computers, minds, and the laws of physics. Oxford University Press.

- Turing, A. M. (1937). On computable numbers, with an application to the Entscheidungsproblem. Proceedings of the London Mathematical Society, 2(42), 230–265. [CrossRef]

- von Neumann, J. (1955). Mathematical foundations of quantum mechanics (R. T. Beyer, Trans.). Princeton University Press. (Original work published 1932).

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).