Submitted:

29 July 2025

Posted:

30 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Materials and Methods

L. orientalis Mill. Oil

Bacterial Strains

Control of Bacterial and Fungal Contamination

Evaluation of Antibacterial Activity

Disc Diffusion Test

Agar Well Diffusion Test

Statistical Analysis

Results

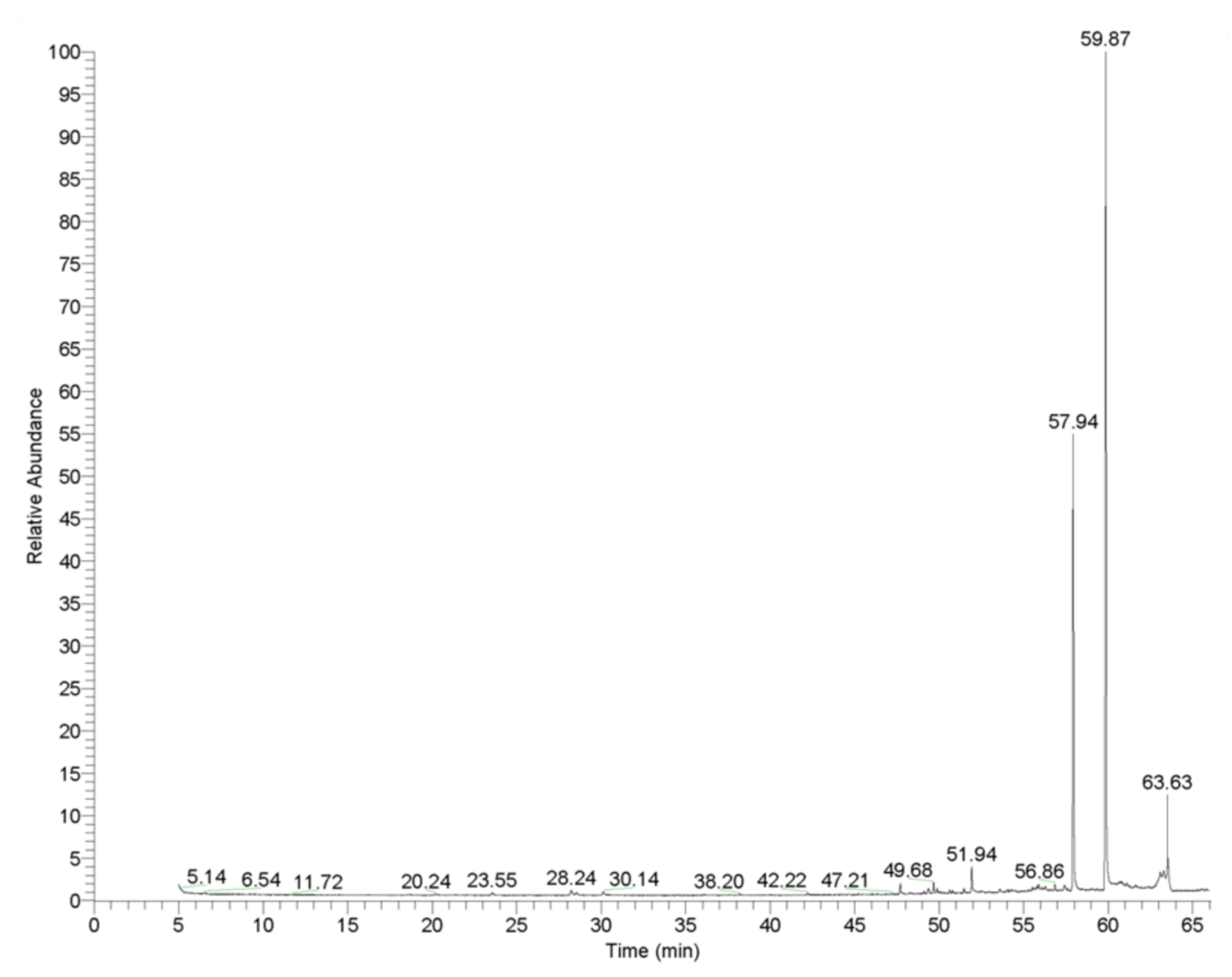

GC-MS Analysis of L. orientalis Mill. Essential Oil

Antibacterial Activity of L. orientalis Mill. Essential Oil

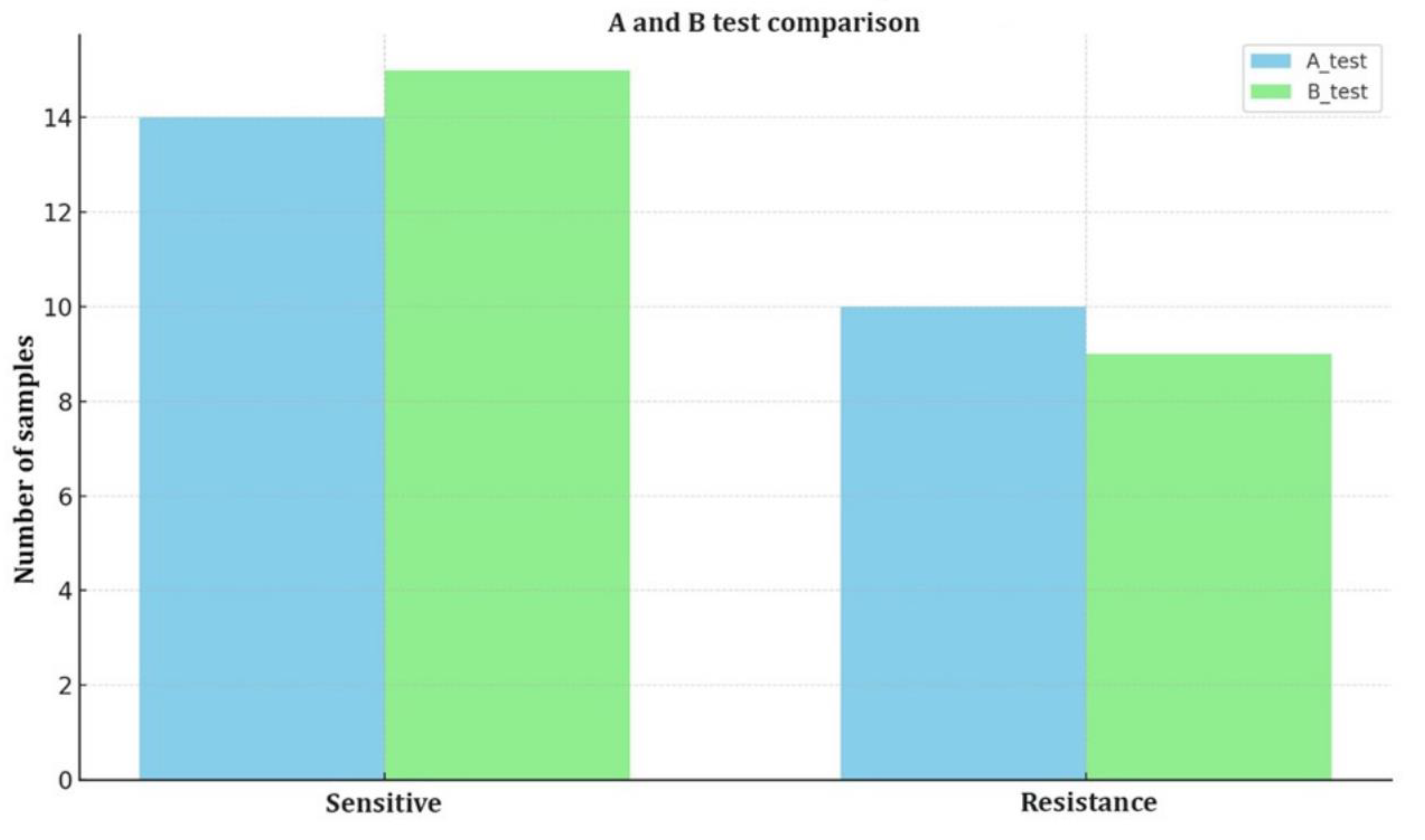

Statistical Analysis

Discussion

Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Ethical Approval

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hoey, M. T.; Parks, C. R. Isozyme divergence between Eastern Asian, North American, and Turkish species of Liquidambar (Hamamelidaceae). Am. J. Bot. 1991, 78, 938–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Öztürk, M.; Çelik, A.; Güvensen, A.; Hamzaoğlu, E. Ecology of tertiary relict endemic Liquidambar orientalis Mill. forests. For. Ecol. Manag. 2008, 256, 510–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sağdıç, O.; Özkan, G.; Özcan, M.; Özçelik, S. A study on inhibitory effects of sığla tree (Liquidambar orientalis Mill. var. orientalis) storax against several bacteria. Phytother. Res. 2005, 19, 549–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özbek, A. G.; Bilek, S. E. Properties and usage of Liquidambar orientalis. Clin. Nutr. Metab. 2018, 1, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Büyükkılıç Altınbaşak, B.; Issa, G.; Zengin Kurt, B. Biological activities and chemical composition of Turkish sweetgum balsam (Styrax liquidus) essential oil. Bezmialem Sci. 2022, 10, 709–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keskin, D.; Güvensen, N. Investigation of antimicrobial properties and chemical composition of different extracts of sweet gum leaves (Liquidambar orientalis). Int. J. Agric. Environ. Food Sci. 2022, 6, 13–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sıcak, Y.; Erdoğan Eliuz, E. A. Chemical composition and antimicrobial activity of Anatolian sweetgum (Liquidambar orientalis Mill.) leaf oil. Turk. J, Life Sci. 2018, 3, 277–281. [Google Scholar]

- Bertagnolio, S. , Dobreva, Z., Centner, C. M., Olaru, I. D., Donà, D., Burzo, S., Huttner, B. D., Chaillon, A., Gebreselassie, N., Wi, T., Hasso-Agopsowicz, M. WHO global research priorities for antimicrobial resistance in human health. Lancet Microbe 2024, 5, 100902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salam, M. A.; Al-Amin, M. Y.; Salam, M. T.; Pawar, J. S.; Akhter, N.; Rabaan, A. A.; Alqumber, M. A. Antimicrobial resistance: A growing serious threat for global public health. Healthc 2023, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddique, H.; Pendry, B.; Rashid, M. A.; Rahman, M. M. Medicinal plants used to treat infectious diseases in Bangladesh. J. Herb. Med. 2021, 29, 100484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stan, D.; Enciu, A. M.; et al. Natural compounds with antimicrobial and antiviral effect and nanocarriers. Front. Pharmacol. 2021, 12, 723233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulusoy, H.; Ceylan, S.; Peker, H. Antioxidant and antimicrobial activity of sweetgum leaf. Polímeros 2021, 31, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nabti, E.; Meziane, R.; Dob, T. Environmental and genetic factors influencing plant secondary metabolites. Biol. Res. 2020, 53, 45–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quinn, P. J.; Markey, B. K.; Leonard, F. C.; Fitzpatrick, E. S.; Fanning, S.; Hartigan, P. J. Veterinary Microbiology and Microbial Disease; 2nd ed.; Wiley-Blackwell: West Sussex, UK, 2011.

- Larone, D. H. Larone, D. H. Medically Important Fungi: A Guide to Identification. 5th ed.; ASM Press, Washington, 2011.

- Bauer, A. W.; Kirby, W. M.; Sherris, J. C.; Turck, M. Antibiotic susceptibility testing by a standardized single disk method. Am. J. Clin. Pathol. 1966, 45, 493–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- CLSI. Performance standards for antimicrobial disk susceptibility tests, M02, 13th ed. Clin. Lab. Stand. Inst. M02, Wayne, PA.4, 2018.

- Aureli, P.; Costantini, A.; Zolea, S. Antimicrobial activity of some plant essential oils against Listeria monocytogenes. J. Food Prot. 1992, 55, 344–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pérez, C.; Anesini, C. Antibacterial activity of alimentary plants against Staphylococcus aureus growth. Am. J. Chin. Med. 1994, 22, 169–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shankar, K. R.; Das, S.; Bujala, P. Phytochemical screening and in vitro antibacterial activity of ethanol and aqueous extracts of Dregea volubilis leaves. Biosci. Biotechnol. Res. Asia 2016, 7, 975–979. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, B.; Xin, H.; Shang, H.; Zhang, W.; Hei, H. Study on extraction and antibacterial activity of essential oil from Liquidambar formosana. J. Essent. Oil Bear. Plants 2023, 26, 176–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mancarz, G.F.F.; Lobo, A.C.P.; Baril, M.B.B.; De Assis Franco, F.; Nakashima, T. Antimicrobial and antioxidant activity of the leaves, bark and stems of Liquidambar styraciflua L. (Altingiaceae). Int. J. Curr. Microbiol. App. Sci. 2016, 5, 306–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parsak, C. K.; Sakman, G.; Çelik, Ü. Wound healing, wound care and complications. Arch. Med. Res. 2007, 16, 145–159. [Google Scholar]

- Kapucuk, F. S.; Dinç, H. Some aromatic plants used in wound treatment in complementary medicine and their usage methods. Exp. Appl. Med. Sci. 2021, 2(4), 257–264. [Google Scholar]

- Saraç, N.; Şen, B. Antioxidant, mutagenic, antimutagenic activities, and phenolic compounds of Liquidambar orientalis Mill. var. orientalis. Ind. Crops Prod. 2014, 53, 60–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gürbüz, I.; Yeşilada, E.; Demirci, B.; Sezik, E.; Demirci, F.; Başer, K. H. Characterization of volatiles and anti-ulcerogenic effect of Turkish sweetgum balsam (Styrax liquidus). J. Ethnopharmacol. 2013, 148, 332–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kıyıcı, R.; Akkan, H. A.; Karaayvaz, B. K.; Karaca, M.; Özmen, O.; Kart, A.; Garlı, S. Effects of sweetgum oil on experimental chronic gastritis in rat model. Indian J. Anim. Res. 2024, 58, 1493–1502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özcan Aykol, Ş. M.; Doğanay, D. Antibacterial effect of Liquidambar orientalis Miller resin on nosocomial infection agents. Int. J. Basic Clin. Stud. 2022, 11, 58–66. [Google Scholar]

- Galińska, E. M.; Zagórski, J. Brucellosis in humans – etiology, diagnostics, clinical forms. Ann. Agric. Environ. Med. 2013, 20, 233–238. [Google Scholar]

- Qureshi, K. A.; Parvez, A.; Fahmy, N. A.; Abdel Hady, B. H.; Kumar, S.; Ganguly, A.; Atiya, A.; Elhassan, G.O.; Alfadly, S.O.; Parkkila, S.; Aspatwar, A. Brucellosis: Epidemiology, pathogenesis, diagnosis and treatment–a comprehensive review. Ann. Med. 2023, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayat, Z.; Khan, H.; Ahmad, I.; Habib, H.; Hayat, K. Antibiotics in the management of brucellosis. Gomal J. Med. Sci. 2018, 16, 114–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- İlhan, Z.; Solmaz, H.; Ekin, I. H. In vitro antimicrobial susceptibility of Brucella melitensis isolates from sheep in an area endemic for human brucellosis in Turkey. J. Vet. Med. Sci. 2013, 75, 1035–1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Mariri, A.; Safi, M. The antibacterial activity of selected Labiatae (Lamiaceae) essential oils against Brucella melitensis. Iran. J. Med. Sci. 2013, 38, 44–50. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- DeCarlo, A.; Zeng, T.; Dosoky, N. S.; Satyal, P.; Setzer, W. N. The essential oil composition and antimicrobial activity of Liquidambar formosana oleoresin. Plants 2020, 9, 822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, G.; Wang, Q.; Wang, Y.; Wen, X.; Peng, H.; Peng, R.; Shi, Q.; Xie, X.; Li, L. Outer membrane porins contribute to antimicrobial resistance in Gram-negative bacteria. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 1690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burt, S. Essential oils: their antibacterial properties and potential applications in foods—a review. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2004, 94, 223–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hulankova, R. Methods for determination of antimicrobial activity of essential oils in vitro—A review. Plants 2024, 13, 2784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Bacteria | Source | |

| 1 | Escherichia coli | ATCC 25932 |

| 2 | Multi-drug resistant Escherichia coli (MDR E. coli) | Animal |

| 3 | Escherichia coli | Human |

| 4 | Escherichia coli | Animal |

| 5 | Staphylococcus aureus subsp. aureus | ATCC 6538 |

| 6 | Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) | ATCC 43300 |

| 7 | Multi-drug resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MDR S. aureus) | Animal |

| 8 | Staphylococcus aureus | Human |

| 9 | Staphylococcus aureus | Animal |

| 10 | Enterococcus faecalis | ATCC 29212 |

| 11 | Enterococcus faecium | ATCC 6057 |

| 12 | Klebsiella pneumoniae | Human |

| 13 | Klebsiella pneumoniae | Animal |

| 14 | Acinetobacter baumannii | Human |

| 15 | Acinetobacter baumannii | Human |

| 16 | Listeria monocytogenes | ATCC 7644 |

| 17 | Salmonella enterica subsp. enterica serotype Typhimurium | NCTC 12416 |

| 18 | Pseudomonas aeruginosa | Human |

| 19 | Multi-drug resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa (MDR P. aeruginosa) | Animal |

| 20 | Mannheimia haemolytica | Human |

| 21 | Mannheimia haemolytica | Animal |

| 22 | Brucella melitensis strain 16M (biotype 1) | ATCC 23456 |

| 23 | Brucella melitensis | Animal |

| 24 | Corynebacterium pseudotuberculosis | Animal |

| Compounds | Retention time (min) | Relative abundance (×106) | Amount (%) | |

| 1 | α-Pinene | 6.54 | 9.40 | 0.13 |

| 2 | Camphene | 7.07 | 0.90 | 0.01 |

| 3 | Benzaldehyde | 8.36 | 1.50 | 0.02 |

| 4 | Sabinene | 9.50 | 2.85 | 0.04 |

| 5 | p-Cymene | 10.14 | 1.70 | 0.02 |

| 6 | dl-Limonene | 11.61 | 1.80 | 0.03 |

| 7 | Benzyl alcohol | 12.54 | 2.10 | 0.03 |

| 8 | 3-Phenyl-1-propanol | 18.59 | 20.50 | 0.29 |

| 9 | Cinnamaldehyde | 28.24 | 3.40 | 0.05 |

| 10 | Cinnamyl alcohol | 28.56 | 28.00 | 0.40 |

| 11 | Ethyl cinnamate | 30.14 | 5.10 | 0.07 |

| 12 | Geraniol acetate | 47.70 | 3.40 | 0.05 |

| 13 | Torreyol | 49.37 | 2.20 | 0.03 |

| 14 | Benzyl cinnamate | 49.68 | 8.90 | 0.13 |

| 15 | 3-Methyl-3-phenyl-azetidin | 51.94 | 10.00 | 0.14 |

| 16 | 4-Methylcoumarine-7-cinnamate | 52.55 | 6.60 | 0.09 |

| 17 | Acetyl tributyl citrate | 56.86 | 5.60 | 0.08 |

| 18 | (1-methylcyclobutyl) benzene | 57.94 | 2201.00 | 31.30 |

| 19 | Cinnamyl cinnamate | 59.87 | 4400.00 | 62.56 |

| 20 | Squalene | 63.63 | 208.00 | 2.96 |

| 21 | Other compounds | - | 110.00 | 1.56 |

| Total | - | - | 100.00 | |

|

Bacteria and their source |

Concentration of L. orientalis Mill. essential oil (µg/mL) |

Antibiotic discs |

|||||||

| 62.5 | 31.25 | 15.62 | 7.8 | 3.9 | 1.9 | CN | S | ||

| Inhibition zone diameter (mm) | |||||||||

| 1 | E. coli (ATCC 25932) | 8 | 8 | 7 | 7 | 6 | 6 | 20 | 16 |

| 2 | MDR E. coli (Animal) | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 10 | 12 |

| 3 | E. coli (Human) | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 6 | 6 | 14 | 12 |

| 4 | E. coli (Animal) | 10 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 6 | 10 | 12 |

| 5 | S. aureus (ATCC 6538) | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 26 | 22 |

| 6 | MRSA (ATCC 43300) | 8 | 8 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 20 | 12 |

| 7 | MDR S. aureus (Animal) | 7 | 7 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 10 | 6 |

| 8 | S. aureus (Human) | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 18 | 8 |

| 9 | S. aureus (Animal) | 14 | 14 | 10 | 8 | 8 | 6 | 24 | 30 |

| 10 | E. faecalis (ATCC 29212) | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 26 | 18 |

| 11 | E. faecalis (ATCC 6057) | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 6 | 14 | 22 |

| 12 | K. pneumoniae (Animal) | 10 | 8 | 8 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 14 | 10 |

| 13 | K. pneumoniae (Human) | 7 | 7 | 7 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 16 | 8 |

| 14 | A. baumannii (Human) | 10 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 24 | 20 |

| 15 | A. baumannii (Human) | 10 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 18 | 8 |

| 16 | L. monocytogenes (ATCC 7644) | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 14 | 8 |

| 17 | S. typhimurium (NCTC 12416) | 7 | 7 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 20 | 10 |

| 18 | P. aeruginosa (Human) | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 20 | 16 |

| 19 | MDR P. aeruginosa (Animal) | 8 | 8 | 8 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 14 | 20 |

| 20 | M. haemolytica (Animal) | 10 | 8 | 8 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 28 | 30 |

| 21 | M. haemolytica (Animal) | 7 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 22 | 24 |

| 22 | B. melitensis (16M) (Animal) | 12 | 12 | 10 | 8 | 8 | 6 | 24 | 26 |

| 23 | B. melitensis (Animal) | 10 | 10 | 8 | 8 | 6 | 6 | 26 | 30 |

| 24 | C. pseudotuberculosis (Animal) | 12 | 10 | 10 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 22 | 18 |

|

Bacteria (source) |

Concentration of L. orientalis Mill. essential oil (µg/mL) | Antibiotics | |||||||

| 62.5 | 31.25 | 15.62 | 7.8 | 3.9 | 1.9 | GS | SS | ||

| Inhibition zone diameter (mm) | |||||||||

| 1 | E. coli (ATCC 25932) | 14 | 14 | 12 | 12 | 8 | 8 | 18 | 16 |

| 2 | MDR E. coli (Animal) | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 22 | 22 |

| 3 | E. coli (Human) | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 18 | 20 |

| 4 | E. coli (Animal) | 12 | 12 | 12 | 10 | 10 | 8 | 28 | 26 |

| 5 | S. aureus (ATCC 6538) | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 32 | 26 |

| 6 | MRSA (ATCC 43300) | 12 | 12 | 12 | 10 | 10 | 8 | 20 | 22 |

| 7 | MDR S. aureus (Animal) | 12 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 10 | 26 | 24 |

| 8 | S. aureus (Human) | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 12 | 8 |

| 9 | S. aureus (Animal) | 14 | 10 | 8 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 20 | 18 |

| 10 | E. faecalis (ATCC 29212) | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 14 | 8 |

| 11 | E. faecalis (ATCC 6057) | 14 | 12 | 10 | 10 | 8 | 8 | 24 | 26 |

| 12 | K. pneumoniae (Animal) | 14 | 12 | 10 | 10 | 8 | 8 | 16 | 22 |

| 13 | K. pneumoniae (Human) | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 14 | 18 |

| 14 | A. baumannii (Human) | 12 | 10 | 10 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 26 | 24 |

| 15 | A. baumannii (Human) | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 12 |

| 16 | L. monocytogenes (ATCC 7644) | 12 | 12 | 12 | 10 | 10 | 8 | 24 | 22 |

| 17 | S. typhimurium (NCTC 12416) | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 10 | 8 |

| 18 | P. aeruginosa (Human) | 12 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 10 | 10 | 22 | 14 |

| 19 | MDR P. aeruginosa (Animal) | 10 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 26 | 22 |

| 20 | M. haemolytica (Animal) | 14 | 14 | 14 | 12 | 12 | 10 | 16 | 14 |

| 21 | M. haemolytica (Animal) | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 18 | 16 |

| 22 | B. melitensis (16M) (Animal) | 16 | 16 | 14 | 12 | 10 | 10 | 24 | 20 |

| 23 | B. melitensis (Animal) | 12 | 10 | 10 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 24 | 18 |

| 24 | C. pseudotuberculosis (Animal) | 12 | 12 | 10 | 10 | 8 | 8 | 22 | 24 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).