1. Introduction

Periodontitis is defined as a chronic, multifactorial, inflammatory disease associated with dysbiotic plaque biofilms and progressive destruction of the tooth-supporting apparatus [

1,

2]. Its primary features include the loss of periodontal tissue support manifested through clinical attachment loss (CAL), radiographically assessed alveolar bone loss, and the presence of periodontal pocketing and gingival bleeding [

1]. Periodontitis may develop in a susceptible host if specific bacteria are present in the structure of subgingival dental plaque [

3,

4].

In the last world workshop on the classification of periodontal and peri-implant diseases, severity and complexity (stage I–IV) and speed of progression (grade A–C) were the basis of the new classification system. The rapid rate of progression is a characteristic feature of grade C periodontitis [

5]. This disease affects specific teeth with early onset and aggressive progression. It occurs in systemically healthy patients, mostly African descendants, at an early age, with familial involvement, minimal biofilm accumulation, and minor inflammation. Severe and rapidly progressive bone loss is observed around the first molars and incisors [

6].

In some cases, periodontitis and dental caries lead to tooth loss, and individuals must adapt to decreased function and aesthetics; moreover, sometimes comorbidities occur. Additionally, periodontal disease is associated with compromised cardiovascular and mental health [

7].

Subgingival instrumentation (SI) with adjunctive use of systemic antibiotics (ATBs) generally provides better clinical treatment results than does SI alone [

8,

9]. However, the European Federation of Periodontology (EFP) S3 Level Clinical Practice Guidelines for treating stage I to III periodontitis do not recommend the routine use of systemic ATBs as an adjunct to SI in patients with periodontitis because of concerns about the impact of systemic ATB use on patients’ and public health. After benefits and possible adverse events are weighed, the adjunctive use of specific systemic ATBs may be considered for particular patient categories, e.g., stage III/IV generalized periodontitis in young adults [

1,

10].

Several studies have shown that nonsurgical therapy leads to significant improvements in the clinical and microbiological parameters of periodontal patients [

3]. However, this modality does not completely eliminate microorganisms and cannot guarantee long-term clinical outcomes, except in cases where modern technologies such as periodontal endoscopy have been used simultaneously [

4,

11].

SI may not be sufficient in hard-to-reach areas such as furcation areas or infrabony pockets. Some periodontal pathogens may also invade periodontal soft tissues or colonize the surface of the tongue and tonsils. Therefore, patient responses often vary. Adjunctive systemic ATB therapy with the correct choice of ATBs can eliminate inaccessible pathogens [

4]. According to Herrera et al., adjunctive use of systemic ATBs leads to better treatment results–, such as probing depth (PD) reduction and CAL reversal in aggressive periodontitis (AgP) patients [

12]. However, some other authors reported no statistically significant difference in the CAL of patients treated with systemic ATBs combined with deep scaling (DS) and root planing (RP; SRP) and those treated with SRP only; however, a significant reduction in the PD occurred for patients treated with systemic ATBs [

13]. In our study, we aimed to compare the periodontal PD (PPD), CAL, bleeding on probing (BOP) status, and plaque index (PI, according to O’Leary et al. (1972)) measured in two groups of patients.

We hypothesized that stage III grade C generalized periodontitis would respond better to the adjunctive use of metronidazole (MTZ) and amoxicillin (AMX) than to SRP alone.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample Size

The calculations were based on data from a randomized controlled study comparing different types of periodontal therapy in patients with advanced periodontal disea.[

14] On the basis of a mean difference in the PPD of 0.5 mm between the groups at 6 months, a standard deviation of 0.55 mm for both groups, an alpha error of 5% and a statistical power of 80%, it was determined that a sample size of 17 patients per group was needed.

2.2. Subject Population and Inclusion/Exclusion Criteria

Altogether, 21 women and 19 men aged 18 to 35 years were enrolled in this prospective comparative study.

The criteria for inclusion in this study were a diagnosis of stage III grade C generalized periodontitis with loss of alveolar bone ranging from 20 to 50% as assessed via intraoral radiograms, more than 30% of sites with CAL and an active periodontal pocket, a minimum of 20 teeth present, at least one active periodontal pocket with a PPD of 6 mm or more in every quadrant, positive BOP, CAL of 6 mm or less and sufficient patient cooperation together with participation in reevaluation and supportive periodontal treatment.

The exclusion criteria for patients included systemic diseases, smoking, DS and RP during the 1.5-year period before initial patient examination, previous periodontal surgeries, systemic administration of ATBs for 6 months before the initial periodontal examination, orthodontic treatment, ATB medication to treat systemic disease during participation in the study, pregnancy and breastfeeding.

On the basis of the new Classification of Periodontal and Peri-implant Diseases,[

2,

10] staging and grading were performed for all patients using secondary evidence (i.e., quotient of relative bone loss at the worst site by age).

2.3. Experimental Design, Randomization, Treatment Protocol and Allocation Concealment

For this prospective, comparative, double-blinded, placebo-controlled RCT, the study coordinator (T.S.) used a computer program (

https://www.randomizer.org). The participants were randomly divided into two groups. Before the first session of the SRP, the subjects were randomly assigned by a computer-generated list to receive one of the two treatments (SRP and systemic antimicrobials or SRP and placebo). Using this list, treatment assignments were distributed in numbered opaque envelopes. Plastic bags containing two identical opaque bottles (20 bottles with amoxicillin 500 mg, 20 with metronidazole 250 mg, 20 with amoxicillin placebo and 20 with metronidazole placebo) were sent to the clinician responsible for the research (B.S.). She opened the sealed envelope and marked the subject’s number on the neutral bottles containing the test or the placebo medications. The plastic bags were given by a study assistant to each patient. The treatment codes of the study were not available to the treating investigator and the examiner until the data were analyzed by the statistician.

The test group consisted of 20 patients who were treated with SRP and adjunctive ATB treatment with 500 mg AMX three times a day and 250 mg MTZ three times a day for a period of 7 days. The control group included 20 patients who were treated with SRP and placebo. Patients in the test group started taking these medications immediately after the first session.

All patients were treated by one trained periodontist (B.S.) who was blinded to the designation of the groups and was not aware of which subjects were receiving the medications. This investigator provided the clinical treatment modalities and took the measurements. The treating investigator did not know which group each patient belonged to until after the data were completely analyzed by a statistician (M.G.).

During the initial periodontal examination (baseline, time 0) and at 6 and 12 months from baseline, the PPD, CAL, BOP and PI were examined. The PPD and CAL indices were measured by a millimeter-calibrated periodontal probe (PCP UNC 15, Hu Friedy) at six sites around each tooth and marked in the periodontal chart of each patient. For statistical analysis of PPD and CAL, an average of the six measurements made at six sites on every tooth was determined for each tooth.

BOP and the PI were measured at four sites on each tooth, and the percentage of sites with positive BOP and the percentage of tooth surfaces with dental plaque presence were determined.

All patients in both groups received full-mouth nonsurgical periodontal treatment delivered over a 24 h period via an ultrasonic device (Cavitron Select SPC, Dentsply professional, York, PA, USA) and manual curettes (Hu-Friedy, Chicago, IL, USA). Whole-mouth SRP was performed at two sequential visits under local anesthesia. Each patient was instructed on proper oral hygiene.

Persistent/recurrent sites (PD ≥ 4 mm, BOP+ or PD ≥ 5 mm) were reinstrumented by ultrasonic devices and hand instruments during the 6–month follow-up session without additional use of ATBs. All study personnel were blinded to the treatment assignment. The subjects received clinical monitoring at baseline, 3 and 6 months, and 1 year posttherapy. In addition, all the subjects received periodontal maintenance and oral hygiene instructions (OHI) every 3 months posttreatment.

In this study, the PPD, CAL, BOP and PI were examined and compared between the test and control groups at baseline and at 6 and 12 months. These indices were also compared between females and males.

2.4. Evaluation of Adverse Events and Compliance

The study assistant called each subject every 2 days by telephone to remind the subject to take the antimicrobial medications. Adverse effects and compliance with medication intake were recorded by the same study assistant, who was not involved in the randomization process. The subjects were asked to return the bottles of medication the day after the last capsule had been taken, and the missing capsules were registered. At the same time, the subjects were asked to complete a questionnaire about side effects that may be associated with the medication.

3. Statistical Analysis

In this study, data exploration and analysis were conducted using jamovi [

15], version 2.4, built on the R platform [

16]. The GAMLj add-on [

17] played a pivotal role in the analysis process. The analyses were performed by a professional statistician (M.G.) who was blinded to the treatment modality. Data entry was performed by one blinded examiner (B.S.) and checked for errors by an additional blinded examiner (M.B.). Data analysis was performed using the patient as the experimental unit. Data from all patients were utilized, as an intention-to-treat analysis was conducted. Continuous variables such as PPD, CAL, BOP, PI, and age were summarized using key statistical measures, including the mean, standard deviation, and minimum and maximum values. To gain insights into their distribution, visual assessments were performed through boxplots overlaid with swarm plots and quantile‒quantile plots. Additionally, a scatterplot was used to visually explore the relationship between a continuous variable and age. The age composition of the cohort, categorized by sex and group, was thoroughly examined via boxplots and quantile‒quantile plots. Two-way ANOVA (

age ~ sex*group) was conducted to assess whether the population mean age differed significantly among subpopulations on the basis of the interaction of group and sex. To model the associations between the response variables (PPD, CAL, BOP, and PI) and predictors (sex, age, group, and time), accounting for the longitudinal study design, a linear mixed model was employed. The model had the form

response ~ 1 + sex + time + age + group + sex:time + sex:group + time:group + sex:time:group (1|id), where

id serves as the identifier for each subject. Post hoc pairwise comparisons, incorporating Bonferroni (and Holm) corrections, were performed to test null hypotheses of the equality of means in the subpopulations. Estimated marginal means were obtained from the model and visualized using marginal means plots, accompanied by 95% confidence intervals. Standard diagnostics were applied to the model, including checks of the distribution of residuals, residual vs. fitted plots, and identification of outliers. A notable outlier was identified in the control group (id #5) with respect to BOP and was subsequently removed from the dataset. The model was refitted without this outlier, ensuring the robustness of the analysis. P values less than 0.05 were considered to indicate statistical significance.

4. Results

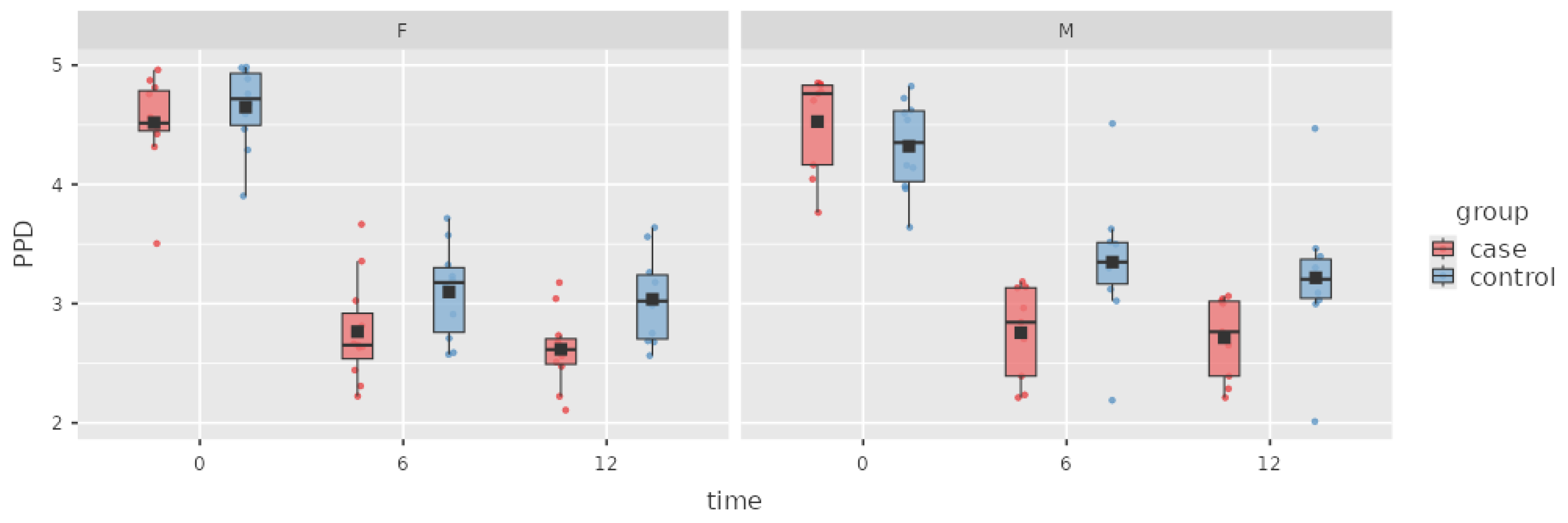

Of the 40 patients enrolled initially in the trial, 40 completed the 12-month follow-up period. In the control group, one patient with grossly outlying BOP data was removed from the analysis. The baseline comparisons of PPD, CAL, BOP and PI-O-Leary scores in both groups with respect to sex are presented in

Table 1. At baseline, no statistically significant intergroup differences in clinical periodontal parameters were detected for sex or group (

Table 1).

In the case group that received adjunctive ATB treatment, the difference in the PPD index was (mean ± SD) 1.76 ± 0.08 mm from baseline to the 6 M appointment, which was statistically significant. During the next period, the PPD further decreased 0.1 ± 0.08 mm in the case group, but this result was not significant.

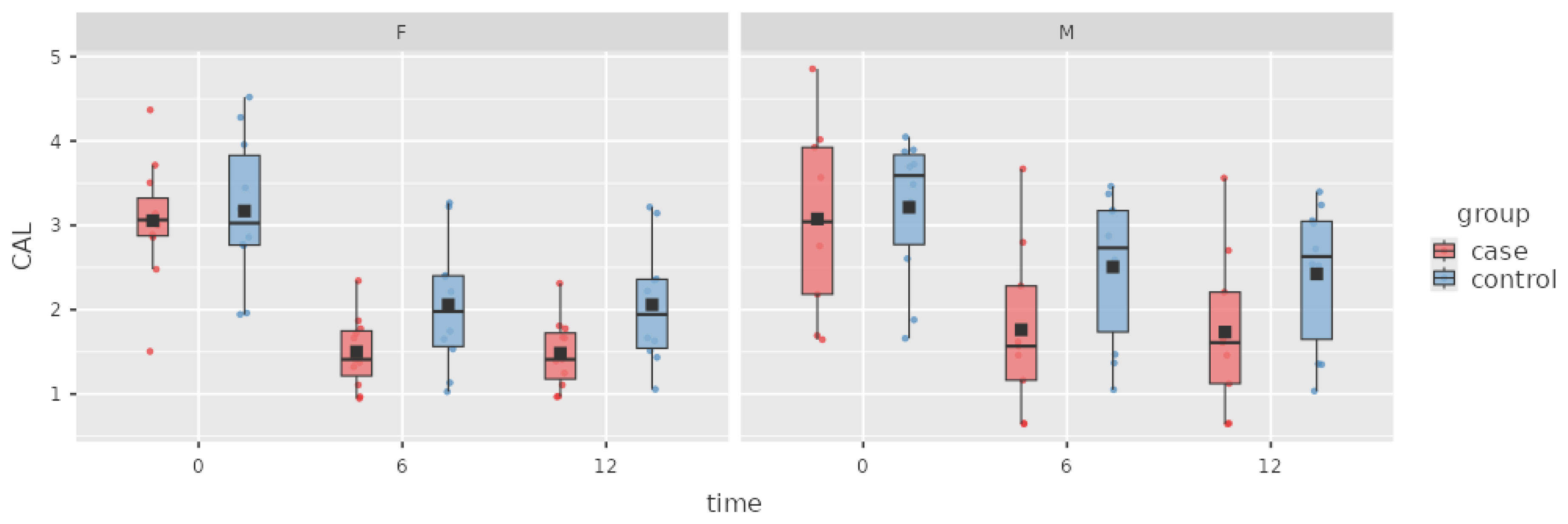

The treatment also led to a statistically significant decrease in CAL (1.43 ± 0.08 mm). At the 12 M appointment, a further decrease in CAL of 0.02 ± 0.08 mm was observed in the case group, and this decrease was not statistically significant.

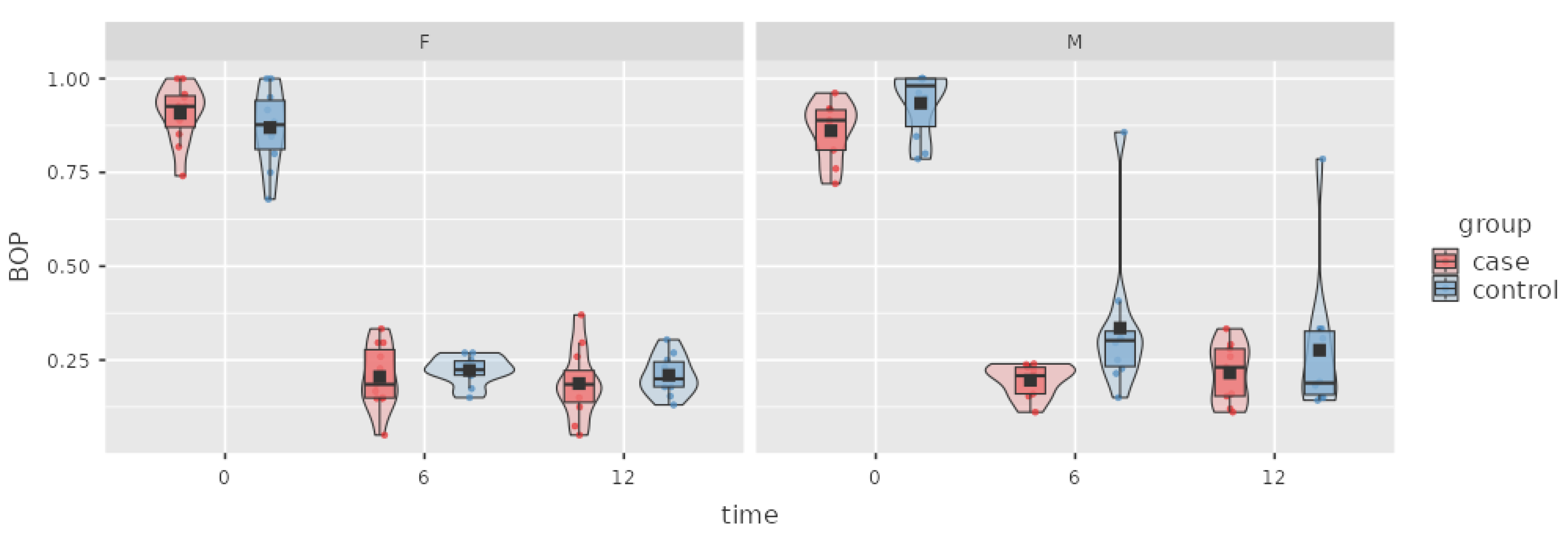

BOP is an important index that indicates the inflammation of periodontal tissue and disease activity. In the case group, the decrease in BOP (0.68 ± 0.02 SD) was statistically significant from baseline to 6 M, but no change was observed at the 12 M appointment.

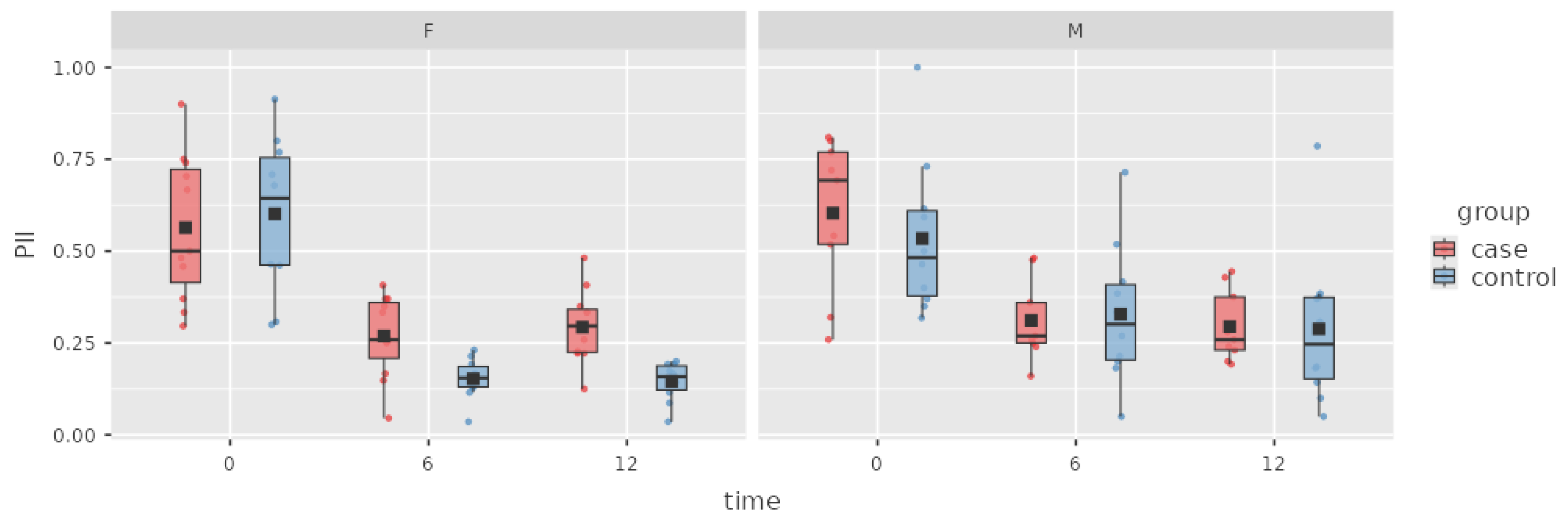

The subjects in the case group managed to improve their oral hygiene habits, which led to a decrease in the PI between baseline and 6 M, with a difference of 0.29 ± 0.04 SD. The patients’ oral hygiene level remained stable at 12 months. The difference in plaque indices between baseline and the 6 M appointment was statistically significant, and no significant difference was observed between the 6 M and 12 M PI values.

Table 2.

Indices at baseline and treatment results in the case group.

Table 2.

Indices at baseline and treatment results in the case group.

| |

0 m |

6 m |

12 m |

| PPD (mm) |

4.53 ± 0.1 |

2.77 ± 0.10* |

2.67 ± 0.10 |

| CAL (mm) |

3.08 ± 0.18 |

1.65 ± 0.18* |

1.63 ± 0.18 |

| BOP (%) |

88 ± 0.01 |

20 ± 2* |

20 ± 2 |

| PI (%) |

58 ± 0.04 |

29 ± 4* |

29 ± 4 |

PPD in the control group decreased by 1.26 ± 0.09 mm from baseline to the 6 M appointment, with statistical relevance. At the 12 M appointment, a further PPD decrease of 0.1 ± 0.08 mm was observed, but this result was not statistically significant.

In the control group, at the 6 M appointment, CAL was significantly decreased by 0.91 ± 0.08 mm from baseline. During the period from 6 to 12 months, CAL decreased 0.04 ± 0.08 mm, but this change was not statistically significant.

A statistically significant decrease in BOP of 0.65 ± 0.02 was observed from baseline to 6 M, but the further decrease of 0.04 ± 0.02 at the 12 M follow-up was nonsignificant.

The subjects in the control group improved their oral hygiene habits, which caused a decrease in the PI of 0.33 ± 0.04 SD between baseline and 6 M. A minor change of 0.02 ± 0.04 SD was observed at the 12 M appointment, but this result was not statistically significant.

Table 3.

Indices at baseline and treatment results in the control group.

Table 3.

Indices at baseline and treatment results in the control group.

| |

0 m |

6 m |

12 m |

| PPD (mm) |

4.48 ± 0.09 |

3.22 ± 0.09* |

3.12 ± 0.09 |

| CAL (mm) |

3.17 ± 0.18 |

2.26 ± 0.18* |

2.22 ± 0.18 |

| BOP (%) |

9 ± 0.02 |

25 ± 2* |

21 ± 2 |

| PI (%) |

57 ± 0.04 |

24 ± 04* |

22 ± 4 |

In the intergroup comparison, the decrease in PPD in the case group was 0.45 ± 0.13 mm greater than that in the control group at 6 M, with a statistically significant beneficial effect of ATBs on the decrease in PPD. The difference in PPD remained stable at 12 M and was not statistically different from that at 6 M.

The difference in CAL between the case and control groups was -0.61 ± 0.13 mm (p= 0.121). A nonsignificant change of -0.59 ± 0.25 mm was observed at 12 M. There was no significant between-group difference in BOP or

The PI at any time point.

Table 4.

Comparison of indices at baseline and treatment results between groups over time.

Table 4.

Comparison of indices at baseline and treatment results between groups over time.

| Parameter |

Group |

0 m |

6 m |

12 m |

| PPD (mm) |

case |

4.53 ± 0.10 |

2.77 ± 0.10 |

2.67 ± 0.1 |

| PPD (mm) |

control |

4.48 ± 0.09 |

3.22 ± 0.09 |

3.12 ± 0.09 |

| Intergroup p value

|

|

0.712 |

0.002 |

0.008 |

| CAL (mm) |

case |

3.08 ± 0.18 |

1.65 ± 0.18 |

1.63 ± 0.18 |

| CAL (mm) |

control |

3.17 ± 0.18 |

2.26 ± 0.18 |

2.22 ± 0.18 |

| Intergroup p value

|

|

1.000 |

0.122 |

0.121 |

| BOP (%) |

case |

88 ± 2 |

20 ± 2 |

20 ± 2 |

| BOP (%) |

control |

90 ± 2 |

25 ± 2 |

21 ± 2 |

| Intergroup p value

|

|

1.000 |

0.187 |

0.909 |

| PI (%) |

case |

0.58 ± 0.04 |

29 ± 4 |

29 ± 4 |

| PI (%) |

control |

0.57 ± 0.04 |

24 ± 4 |

22 ± 4 |

| Intergroup p value

|

|

1.000 |

1.000 |

1.000 |

Figure 1.

Box plot of the PPD index in the case and control groups over time.

Figure 1.

Box plot of the PPD index in the case and control groups over time.

Figure 2.

Box plot of the CAL index in the case and control groups over time.

Figure 2.

Box plot of the CAL index in the case and control groups over time.

Figure 3.

Box plot of the BOP index in the case and control groups over time.

Figure 3.

Box plot of the BOP index in the case and control groups over time.

Figure 4.

Box plot of the PI in the case and control groups over time.

Figure 4.

Box plot of the PI in the case and control groups over time.

5. Discussion

Effective management of aggressive forms of periodontitis is often challenging for dental professionals. The results of several randomized controlled trials (RCTs) suggest that AMX/MET is the most effective antimicrobial adjunct to DSRP for PPD reduction and CAL reversal [

4,

18,

19]. In our study as well as in other studies, antimicrobials in the case group were prescribed empirically (i.e., without prior analysis of intraoral bacteria) [

20].

A systematic review and meta-analysis by Karrabi et al. supported the adjunctive use of AMX/MET since it substantially improved the clinical parameters of moderate and severe pockets in patients with AgP, 0.85 mm (95% CI = -1.082.78; I

2 = 91%) [

4]. In this study, a comparison of the efficacy of AMX/MET at the 3- and 6-month follow-ups revealed considerable improvements in PPD and CAL at the 3-month follow-up. However, no significant change occurred after the 3-month follow-up from 3 to 6 months. This shows deceleration or stagnation of the healing process in periodontal pockets. The effect of ATB therapy with AMX/MTZ after a period of 3 months is therefore questionable, and the overall effect of AMX/MTZ in periodontitis treatment may be considered short-term [

4].

In a double-blinded randomized clinical trial by Mestnik et al., thirty subjects were randomly assigned to receive SRP alone or combined with MTZ (400 mg/TID) and AMX (500 mg/TID) for 14 days.

There were no statistically significant differences between groups for any parameter at baseline (p > 0.05). At 6 months and 1 year, the full-mouth mean PPD was significantly lower in the test group than in the control group. The PPD reduction from 0–6 months was 0.94 ± 0.38 mm in the control group and 1.58 ± 0.51 mm (p=0.00084) in the case group. The PPD reduction from 0–1 year was 0.92 ± 0.47 mm in the control group and 1.61 ± 0.60 mm (p=0.00230) in the case group. These results revealed no significant changes in full-mouth PPD reduction during the period from 6 to 12 months in any group [

21].

This corresponds with our finding that the average PPD reduction was 1.76 mm (p < .001) at the 6 M follow-up and another 0.1 mm (p=0.710) at the 12 M follow-up in the case group and that the average PPD reduction at the 6 M follow-up was 1.26 mm (p< .001) and another 0.1 mm (p=0.710) at the 12 M follow-up in the control group. At 6 months, the full-mouth mean PPD was significantly lower in the test group than in the control group (0.45) (p-holm=0.008).

Some studies have shown that severe periodontitis at a younger age is an indicator of increased susceptibility and rapid disease progression. Therefore, younger periodontitis patients (grade C periodontitis) may benefit more from adjunctive ATB therapy than older patients with comparable disease severity [

22,

23,

24,

25].

In a systematic review and meta-analysis by Mendes et al. using data from four studies [

21,

26,

27,

28], no statistically significant difference was observed in the CAL between the use of AMX/MTZ combined with SRP and SRP alone (p = 0.52, mean deviation [MD]: 0.21, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.04–0.46). There was a statistically significant difference in the PD between the use of systemic ATBs with SRP and the use of SRP alone (p = 0.02, MD: 0.40, 95% CI: 0.02–0.78). The reversal of CAL was not significantly greater when systemic ATBs were used with SRP than when SRP without ATBs was used to treat aggressive periodontitis [

29].

According to a meta-analysis by Karrabi et al. including studies comparing groups with DSRP plus AMX/MTZ with DSRP alone during a time period of 6 months, a statistically significant difference in CAL reversal was noted only in moderate pockets when 400 to 500 mg MTZ MD = 1.82 was used (95% CI = 1.11 to 2.53; P < 0.0001; I

2 = 36%). The lack of a statistically significant difference showed that 250 mg of MTZ did not improve CAL when administered to patients with moderate pockets. There was no statistically significant difference in CAL for patients with deep pockets after treatment with any of the evaluated MTZ doses (MD = 2.2; 95% CI = 0.37 to 4.78; P = 0.09; I

2 = 94%; MD = 0.79; 95% CI = 0.21 to 1.79; P = 0.12; I

2 = 70%). Higher doses of MTZ (400 to 500 mg) may be required for better efficacy regarding CAL reversal [

4].

These results correspond with those of our study, where the results of the intergroup comparison of CAL reversal at 6 and 12 months were not statistically significant.

BOP is an essential index in the evaluation of periodontal inflammation, and the absence of BOP is an important predictor of periodontal stability [

30,

31].

Several studies have shown the potential short-term effects of adjunctive AMX+MTZ treatment [

32,

33,

34]. In our study, there was no significant difference in the BOP index between the groups, which may be caused by the inadequate presence of deep periodontal pockets in the test group.

No significant change was observed in the BOP index in the case and control groups between the 6 M and 12 M periods, supporting the findings of the study by Karrabi et al., who reported that AMX/MTZ has positive short-term effects as an adjunct to SRP for the treatment of stage—II–III grade C periodontitis [

4].

Sufficient dental biofilm control is essential in the treatment of any periodontitis case. All participants except one managed to keep plaque levels low at the 6- and 12-month follow-ups. This subject was excluded from the data analysis. A large decrease in the PI was recorded in both groups at the 6-month follow-up, and it was statistically significant. Patients in both groups had acceptable plaque levels at the 12-month follow-up, with only a small statistically significant difference between plaque levels at the 6- and 12-month follow-ups. There was also no significant difference in plaque level between the case and control groups.

A study by Dos Santos et al. analyzing data from 1042 patients diagnosed with stage III/IV grade B/C generalized periodontitis showed a slightly inferior clinical response to periodontal therapy in men in a limited number of subanalyses than in women. These small differences do not appear to be clinically relevant, but the authors suggest that future research should continue to explore this topic [

35].

Tavakoli et al. conducted a study on 79 participants diagnosed with grade C molar incisor periodontitis (C/MIP), where PD, CAL, BOP, visible plaque and immunological parameters from blood and gingival crevicular fluid were analyzed one year after treatment. There was no statistically significant difference among all the clinical parameters when both sexes from the C/MIP group were compared [

36].

In our study, no relevant difference in patient compliance or treatment results for any index was observed between males and females. One male subject was excluded from the database before data analysis because of unsatisfactory compliance and dental hygiene.

Despite the significant additional benefits demonstrated in numerous randomized controlled trials [

37], the European Federation of Periodontology (EFP) clinical practice S3 guidelines for the treatment of stage I–III periodontitis do not recommend the routine use of systemic ATBs as adjuncts to SI in patients with periodontitis. This is due to concerns about the impact of the use of systemic ATBs on patients’ health and on public health in general. After the benefits and possible adverse events are weighed, the adjunctive use of specific systemic ATBs may be considered for particular patient categories (e.g., stage III/IV generalized periodontitis in young adults) [

2,

10,

38,

39,

40].

6. Study Limitations

This study clearly has its limitations. Some of these limitations highlight the need for RCTs that, from their inception, implement the 2018 Classification of Periodontal and Peri-implant Diseases and Conditions. These studies could include only specific diagnoses (e.g., stage III or grade C) or, ideally, could stratify randomization by stage and grade. However, the latter would require a relatively large overall sample size. Although this was a prospective comparative study and patients were enrolled randomly, measures were not implemented to control for compliance with the actual intake of ATBs in the case group. The study was not double-blinded, as patients in the control group did not receive systemic ATB administration. Theoretically, with the use of adjunctive systemic ATBs, patients in the control group could have achieved better clinical results; however, this did not occur according to the comparison of CAL, BOP, and the PI in our study. The current understanding is that the presence of periodontitis in stages I-IV does not influence the decision for adjunctive administration of systemic ATBs along with SI [

2,

39]. However, this study reports data from a highly standardized clinical trial; thus, the results have a broad and solid basis.

7. Conclusions

Given the background and risk of increasing microbial resistance, systemic ATBs should be prescribed cautiously for the treatment of so-called nonlife-threatening diseases. This stance is clearly expressed in the EFP’s clinical guidelines for the treatment of stage I, II, and III periodontitis. The increased occurrence of bacterial resistance is strongly associated with the frequency of ATB use. Therefore, it would be appropriate to identify diagnoses and individuals who could provide a decision criterion for indications of adjunctive systemic antimicrobial therapy. Within the limitations of this analysis, we can conclude that patients with stage III grade C generalized periodontitis experienced greater clinically relevant benefits from systemic adjunctive administration of AMX/MTZ with SI than did the control group of patients, specifically in terms of the PPD index. For other indices, such as CAL and BOP, no statistically significant differences were observed. Therefore, even in the context of EFP and AAP recommendations, we can consider these findings as additional aids in the decision-making process for the use of systemic AMX/MTZ. Regarding generalizability, it would be interesting to investigate whether these newly identified findings are also suitable for patients with periodontitis who smoke and patients with diabetes mellitus. The development of a treatment plan on the basis of the results of clinical studies on the efficacy of periodontal therapy, which considers the current understanding of periodontitis as a complex inflammatory disease with multiple causative factors, is currently preferred. We can diagnose, classify, and treat patients with periodontitis to prevent long-term tooth loss and improve their quality of life.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, B.S. and T.S.; methodology B.S., T.S.; software, M.G.; validation, M.B. and M.G.; formal analysis, D.S and M.B.; data curation, M.G and M.B.; writing—original draft preparation, B.S.; writing—review and editing, T.S and B.S.; visualization, M.G.; supervision, D.S.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the Declaration of Helsinki (1964, revision 2008), and its protocol was approved by the Ethical Committee of the Jessenius Faculty of Medicine in Martin (Protocol number: EK 41/2022) before commencement. Approved 03.10.2022.

Ethics Approval

All the subjects were patients seeking dental treatment at the Department of Stomatology and Maxillofacial Surgery, Jessenius Faculty of Medicine in Martin, Comenius University in Bratislava, Slovakia.

Informed Consent Statement

All patients were informed about the nature of the study, and written, freely given informed consent was obtained prior to the commencement of the study.Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. Written informed consent has been obtained from the patients to publish this paper.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author due to privacy and ethical restrictions.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| PPD |

Periodontal probing depth |

| BOP |

Bleeding on probing |

| CAL |

Clinical attachment loss |

| PI |

Plaque index O’Leary et al.1972 |

| DS |

Deep scaling |

| RP |

Root planing |

| ATBs |

Antibiotics |

| AMX |

Amoxicillin |

| MTZ |

Metronidazole |

| AgP |

Aggressive periodontitis |

| EFP |

European Federation of Periodontology |

| SD |

Standard deviation |

References

- Papapanou, P. N., Sanz, M., Buduneli, et al. (2018). Periodontitis: Consensus report of workgroup 2 of the 2017 World Workshop on the Classification of Periodontal and Peri-Implant Diseases and Conditions. Journal of Clinical Periodontology, 45(Suppl. 20), S162–S170. [CrossRef]

- Sanz M, Herrera D, Kebschull M, et al.; On behalf of the EFP Workshop Participants and Methodological Consultants. Treatment of stage I–III periodontitis—The EFP S3 level clinical practice guideline. J Clin Periodontol. 2020;47:4–60. [CrossRef]

- Eva Skalerič, Milan Petelin, Boris Gašpirc,: Antimicrobial photodynamic therapy in treatment of aggressive periodontitis (stage III, grade C periodontitis): A comparison between photodynamic therapy and antibiotic therapy as an adjunct to non-surgical periodontal treatment, Photodiagnosis and Photodynamic Therapy, Volume 41, 2023, 103251, ISSN 1572-1000. [CrossRef]

- Karrabi M, Baghani Z. Amoxicillin/Metronidazole Dose Impact as an Adjunctive Therapy for Stage II–III Grade C Periodontitis (Aggressive Periodontitis) at 3- And 6-Month Follow-Ups: a Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Oral Maxillofac Res. 2022 Mar 31;13(1):e2. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Caton JG, Armitage G, Berglundh T, et al.; A new classification scheme for periodontal and peri-implant diseases and conditions—Introduction and key changes from the 1999 classification. J Clin Periodontol. 2018 Jun;45 Suppl 20:S1-S8. [Medline: 29926489]. [CrossRef]

- Miguel MMV, Shaddox LM. Grade C Molar-Incisor Pattern Periodontitis in Young Adults: What Have We Learned So Far? Pathogens. 2024 Jul 12;13(7):580. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Al-Bitar KM, Garcia JM, Han S and Guentsch A (2024) Association between periodontal health status and quality of life: a cross-sectional study. Front. Oral. Health 5:1346814. [CrossRef]

- Teughels W, Feres M, Oud V, Martín C, Matesanz P, Herrera D. Adjunctive effect of systemic antimicrobials in periodontitis therapy: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Periodontol. 2020 Jul;47 Suppl 22:257-281. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eickholz, P., Koch, R., Göde, M.,et al. (2023). Clinical benefits of systemic amoxicillin/metronidazole may depend on periodontitis stage and grade: An exploratory sub-analysis of the ABPARO trial. Journal of Clinical Periodontology, 50(9), 1239–1252. [CrossRef]

- Kebschull, M., Jepsen, S., Kocher, T., et al. (2020). Die Behandlung von Parodontitis Stadium I bis III. Die deutsche Implementierung der S3-Leitlinie “Treatment of Stage I–III Periodontitis” der European Federation of Periodontology (EFP). S3-Leitlinie. https://www.awmf.org/ uploads/tx_szleitlinien/083-043l_S3_Behandlung-von-Parodontitis- Stadium-I-III_2021-02_2.pdf:AWMF.

- Wu J, Lin L, Xiao J, et al.; Efficacy of scaling and root planning with periodontal endoscopy for residual pockets in the treatment of chronic periodontitis: a randomized controlled clinical trial. Clin Oral Investig. 2022 Jan;26(1):513-521. [Medline: 34145479]. [CrossRef]

- Herrera D, Alonso B, León R, Roldán S, Sanz M. Antimicrobial therapy in periodontitis: the use of systemic antimicrobials against the subgingival biolm. J Clin Periodontol. 2008 Sep;35(8 Suppl):45-66. [Medline: 18724841]. [CrossRef]

- Cácio Lopes Mendes, Paulo de Assis, Hermínia Annibal, et al.; Metronidazole and amoxicillin association in aggressive periodontitis: A systematic review and meta-analysis, The Saudi Dental Journal, Volume 32, Issue 6, 2020, Pages 269-275, ISSN 1013-9052(https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1013905219311101). [CrossRef]

- Siebert, T. Parodontitída. 1st ed. Plzeň: Vydavatelství a nakladatelství Aleš Čeněk, 2022. ISBN 978-80-7380-895-2.

- The jamovi project (2023). jamovi. (Version 2.4) [Computer Software]. Retrieved from https://www.jamovi.org.

- R Core Team (2022). R: A Language and environment for statistical computing. (Version 4.1) [Computer software]. Retrieved from https://cran.r-project.org. (R packages retrieved from CRAN snapshot 2023-04-07).

- Gallucci, M. (2019). GAMLj: General analyses for linear models. [jamovi module]. Retrieved from https://gamlj.github.io/.

- Haffajee AD, Socransky SS, Gunsolley JC. Systemic anti-infective periodontal therapy. A systematic review. Ann Periodontol. 2003 Dec;8(1):115-81. [CrossRef]

- Heitz-Mayfield LJ. Systemic antibiotics in periodontal therapy. Aust Dent J. 2009 Sep;54 Suppl 1:S96-101. [CrossRef]

- Eickholz, P., Koch, R., Kocher, T., et al. (2019). Clinical benefits of systemic amoxicillin/metronidazole may depend on periodontitis severity and patients’ age: An exploratory sub-analysis of the ABPARO trial. Journal of Clinical Periodontology, 46, 491–501. [CrossRef]

- Mestnik MJ, Feres M, Figueiredo LC, et al.; The effects of adjunctive metronidazole plus amoxicillin in the treatment of generalized aggressive periodontitis. A 1-year double-blinded, placebo-controlled, randomized clinical trial. J Clin Periodontol 2012; 00: 000–000. [CrossRef]

- Branco-de-Almeida, L. S., Velsko, I. M., de Oliveira, I. C. V., de Oliveira, R. C. G., & Shaddox, L. M. (2023). Impact of treatment on host responses in young individuals with periodontitis. Journal of Dental Research, 102, 473–488. [CrossRef]

- Eickholz, P., Koch, R., Gode, M., et al. (2023). Clinical benefits of systemic amoxicillin/metronidazole may depend on periodontitis stage and grade: An exploratory sub-analysis of the ABPARO trial. Journal of Clinical Periodontology, 50, 1239–1252. [CrossRef]

- Faveri M, Retamal-Valdes B, Mestnik MJ, et al.; Microbiological effects of amoxicillin plus metronidazole in the treatment of young patients with Stages III and IV periodontitis: A secondary analysis from a 1-year double-blinded placebo-controlled randomized clinical trial. J Periodontol. 2023 Apr;94(4):498-508. Epub 2023 Jan 30. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Winkler, P. C., Benz, L., Nickles, K.,Petsos, H. C., Eickholz, P., & Dannewitz, B. (2024). Decision-making on systemic antibiotics in the management of periodontitis: A retrospective comparison of two concepts. Journal of Clinical Periodontology, 51(9), 1122–1133. [CrossRef]

- Berglundh, T., Krok, L., Liljenberg, B., et al., 1998. The use of metronidazole and amoxicillin in the treatment of advanced periodontal disease. A prospective, controlled clinical trial. J Clin Periodontol 25, 354–362. [CrossRef]

- Taiete, T., Casati, M.Z., Ribeiro, E.D.P., et al., 2016. Amoxicillin/metronidazole associated with nonsurgical therapy did not promote additional benefits in immunologic parameters in generalized aggressive periodontitis: a randomized controlled clinical trial. Quintessence Int 47, 281–292. [CrossRef]

- Yek, E.C., Cintan, S., Topcuoglu, N., et al., 2010. Efficacy of amoxicillin and metronidazole combination for the management of generalized aggressive periodontitis. J Periodontol 81, 964–974. [CrossRef]

- Mendes, C. L., Assis, P. de, Annibal, H., et al. (2020). Metronidazole and amoxicillin association in aggressive periodontitis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. The Saudi Dental Journal, 32(6), 269–275. [CrossRef]

- Lang N, Bartold P (2018) Periodontal health. J Periodontol 89(S1): S9-S16. [CrossRef]

- Boivin WG, et al. Adjunctive Antimicrobials in Nonsurgical Periodontitis Treatment: A Review of Recent Trials and Indications. J Dental Sci 2025, 10(1): 000411. [CrossRef]

- Mugri MH. Efficacy of Systemic Amoxicillin-Metronidazole in Periodontitis Patients with Diabetes Mellitus: A Systematic Review of Randomized Clinical Trials. Medicina (Kaunas). 2022 Nov 7;58(11):1605. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Borges I, Faveri M, Figueiredo LC, Duarte PM, Retamal-Valdes B, Montenegro SCL, Feres M. Different antibiotic protocols in the treatment of severe chronic periodontitis: A 1-year randomized trial. J Clin Periodontol. 2017 Aug;44(8):822-832. Epub 2017 Jul 26. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feres M, Retamal-Valdes B, Faveri M, et al.; Proposal of a Clinical Endpoint for Periodontal Trials: The Treat-to-Target Approach. J Int Acad Periodontol. 2020 Apr 1;22(2):41-53. [PubMed]

- Castro dos Santos N, Westphal MR, Retamal-Valdes B, et al. Influence of gender on periodontal outcomes: A retrospective analysis of eight randomized clinical trials. J Periodont Res. 2024; 59: 1175-1183. [CrossRef]

- Tavakoli TT, Gholami F, Huang H, et al. Gender differences in immunological response of African-American juveniles with Grade C molar incisor pattern periodontitis. J Periodontol. 2021;1-11. [CrossRef]

- Teughels, W., Feres, M., Oud, V., Martin, C., Matesanz, P., & Herrera, D. (2020). Adjunctive effect of systemic antimicrobials in periodontitis therapy: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Clinical Periodontology, 47(Suppl 22), 257–281. [CrossRef]

- Jockel-Schneider, Y., Pretzl, B., Ehmke, B., & Schlagenhauf, U. (2018). S3-Leitlinie (Kurzversion): Adjuvante systemische Antibiotikagabe bei subgingivaler Instrumentierung im Rahmen der systematischen Parodontitistherapie. Parodontologie, 29, 387–398.

- Pretzl, B., Salzer, S., Ehmke, B., et al. (2019). Administration of systemic antibiotics during non-surgical periodontal therapy-a consensus report. Clinical Oral Investigations, 23, 3073–3085. [CrossRef]

- Benz, L., Winkler, P., Dannewitz, B., et al. (2023). Additional benefit of systemic antibiotics in subgingival instrumentation of stage III and IV periodontitis with Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans: A retrospective analysis. Journal of Clinical Periodontology, 50(5), 684–693. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).