1. Introduction

1.1. Background

Housing stability is a fundamental determinant of health that impacts virtually every aspect of an individual's life [

1]. Being unstably housed has a greater impact on one’s health, including physical, mental, and overall well-being, compared to the general population [

2,

3,

4]. Housing instability can be broadly defined as the lack of fixed or adequate housing, unstable neighborhoods [

5], and homelessness due to a lack of a nighttime residence [

6]. A person who is unstably housed moves frequently, spends almost all their income on rent, or lives in a shared space that is grossly inadequate [

7]. Homelessness is defined as the lack of a fixed and adequate nighttime residence or a primary nighttime residence designed to provide temporary accommodation to individuals or families, whether privately or publicly operated [

7]. There is an additional layer of homelessness known as unsheltered homelessness, where people who experience this sleep in unconventional places: places that do not qualify for human habitation, like sidewalks, train stations, tents, sheds, and garages [

8]. The United States has a lifetime prevalence of homelessness of approximately 4.2% [

9]. As of January 2023, over 650,000 people in the United States experienced homelessness on a single night, and over 50% of those people were unsheltered [

8]. Out of these numbers, over 12,000 were from the State of Georgia [

8]. Studies have shown that about 1 out of every 3 to 4 people experiencing homelessness use drugs [

9,

10]. People who use drugs (PWUD) and are experiencing homelessness suffer more harmful effects of drug use compared with people who are housed, including drug overdose-related deaths [

11,

12]. Not only is housing a fundamental determinant of an individual's health, but it also imposes a financial as well as logistical burden on the healthcare system [

13]. A study by Kertesz et al. (2020) found that people experiencing homelessness in the program had average annual healthcare costs of

$18,764, compared to

$7,561 for housed Medicaid patients. This is largely due to increased use of emergency departments and outpatient services. Without stable housing, these conditions often go unmanaged, leading to frequent and costly hospital visits. The difference in annual costs between the two groups, about

$4,400 more per year, highlights how increased spending is tied to the financial strain of delayed and inaccessible care. In summary, this study highlights that unstable housing leads to poorer health outcomes, which directly contributes to rising healthcare costs [

14].

1.2. Measure Housing Instability

For this study, we chose the Housing Instability Scale by Farero et al (2022) [

29].

Before the development and validation of the 7–item Housing Instability Score (HIS) by Farero et al. (2022) [

29], researchers employed various scales and measures to evaluate housing conditions across diverse contexts [

29]. Annett et al. (2024) assessed housing insecurity among incarcerated women with opioid use disorder using a brief two-item index based on homelessness and precarious housing in a period of 90 days [

15]. Glynn et al (2024 & 2025) utilized subscales of Economic Hardship to evaluate the financial strain among patients at risk of HIV and emergency department patients, respectively [

16,

17]. Donoghue et al (2025) used an abbreviated four-item version of the HIS among undergraduate students in a Hispanic-serving institution, finding it practical for identifying psychosocial risk [

18]. It, however, failed to explore validated cutoffs. In recent studies, the full seven-item scale has been used in longitudinal studies such as those by Sullivan et al (2023) and Goodman-William et al (2023), who evaluate housing instability over a two-year period among survivors of the Domestic Violence Program [

19,

20].

Despite the diverse application of this scale, there remains a lack of standardized cutoffs and its validation across studies. One of our study aims is to establish a validated HIS cutoff to aid in more coherent findings on housing stability in future research.

The intersection of housing instability and drug use has become increasingly concerning amid the ongoing opioid crisis. Opioid overdose deaths have been on the rise over the past two decades, with over 80,000 deaths recorded in 2022 alone - a surge largely attributed to the proliferation of synthetic opioids like fentanyl [

11,

12,

21]. Infectious diseases like HIV/AIDS and Hepatitis C infections are a major cause of morbidity and mortality among people who inject drugs [

22], and studies have found this association amplified among those experiencing homelessness and the unstably housed [

6]. Up to one-fifth of incident cases of HIV and hepatitis C infections are unstably housed people who inject drugs in countries like the United States, Czech Republic, England, and India [

23].

1.3. Substance Use and Health Outcomes

Individuals with substance use disorders and people who use drugs generally face multiple barriers to securing stable housing, primarily due to drug-related stigma and healthcare inequities [

6,

24]. These disparities have been found to be barriers to health-seeking behaviors like seeking primary care and preventive services among this population [

25]. The population of people experiencing homelessness is also difficult to access and therefore underscores interventions such as HIV treatments, following up on patients with mental illness, and substance use disorder [

26]. Adequate housing has also been found to reduce the number of hospital admissions and emergency room visits [

26]. These challenges extend beyond housing to healthcare access, contributing to elevated rates of infectious diseases (such as Hepatitis C and HIV/AIDS), mental health disorders, and drug overdose deaths within this population [

6,

24,

27]. Despite the apparent connection between housing stability and adverse health outcomes, including overdose deaths, this relationship remains understudied [

2].

While various socioeconomic factors influence housing stability, understanding its direct impact on the health outcomes of PWUD is crucial and needs to be explored [

28]. This research aims to examine this relationship comprehensively, potentially informing evidence-based policies to address healthcare access disparities among this vulnerable population. Understanding this relationship would inform interventions such as building structural institutions, such as housing, in efforts to reduce drug-related morbidity and mortality, which would complement the efforts being made by the government to treat health outcomes such as drug addiction [

12]. This study aims to characterize the housing status of people who use drugs in an urban setting in the Southeastern United States (US), determine a cut-off score of the housing insecurity scale to categorize housing stability [

29], and lastly, examine the relationship between the housing status of people who use drugs and health outcomes, including opioid-related overdose between June and October 2024.

2. Materials and Methods

This study aimed to investigate the relationship between housing stability and drug-related health outcomes among people who use drugs in an urban setting in the Southeastern US.

2.1. Parent Study

We employed a community-based participatory and concurrent iterative mixed methods design to assess barriers and facilitators to community drug checking in a convenience sample of harm reductionists, workers from a County Board of Health, and people who use drugs in an urban setting in the Southeastern United States. People who use drugs were recruited from syringe exchange sites, community settings (primarily festivals and bars), and by using a snowball sample. Survey data recruitment and collection with people who use drugs spanned a period over five months in 2024. The inclusion criteria for survey participation were 18 years and older and had used at least one unregulated drug (outside of a prescription) in the past 12 months, excluding marijuana. There were no other exclusion criteria. We chose to exclude those who exclusively used marijuana for two reasons; firstly, marijuana is a prevalent drug used outside of a prescription in the urban area, and there is insufficient evidence that marijuana can be tested with drug checking supplies and has been adulterated with drugs that cause harm, e.g., fentanyl and xylazine.

2.2. Project Design

This cross-sectional study used a survey to collect data from people who use drugs to assess current drug use, housing insecurity, and health outcomes. Data was collected from July 2024 to November 2024. This project focused on characterizing housing status, determining cut-off scores of the Housing Instability Scale, and drug-related health outcomes of people who use drugs in an urban setting in the Southeastern US.

2.3. Survey Development

The survey was developed in collaboration with community members with lived and living experiences of drug use and drug-related harm, harm reductionists, and researchers. Co-creation of such surveys is an important step to ensuring community priorities are included in studies [

56] and is frequently seen in programs that involve PWUD [

57,

58]. The survey collected data on demographics, housing status, substance use history in the past 12 months, and drug-related health outcomes. The housing status data were collected using the Housing Instability Scale [

29].

2.4. Measure: The Housing Instability Scale

The Housing Instability Scale (HIS) is a seven-item validated scale that aims to measure housing instability to inform policies and public health interventions [

29]. These seven items serve as indicators, dichotomized into a score of either 0 or 1. The higher the score (0 – 7), the more instability in housing. The specific items of the scale are:

Lived in an undesired or unstable housing situation in the past 6 months

Uncertainty about maintaining current housing for the next 6 months

Stayed with family or friends to avoid homelessness

Experienced difficulty paying for housing (eg. Rent or mortgage)

Faced challenges obtaining stable housing

Low confidence in ability to pay for housing this month

Experienced frequent moving (3 or more times) in the past 6 months

Concurrent and predictive validity were assessed using the time-invariant factor, examining HIS factor scores and relevant concurrent and future variables [

29]. These models were conducted using MPlus version 8 [

30].

2.5. Sample

A convenience sampling approach was used to recruit participants to the study during harm reduction syringe exchange programming, local nightlife events at bars and clubs, at festivals, and via snowball sampling. Inclusion criteria were those aged 18 years and older who had used any unregulated drugs outside prescription in the past 12 months other than marijuana; there were no exclusion criteria. We recruited 180, and of those, N=164 participated in the study with a response rate of 91%.

2.6. Data Management

All data were collected through RedCap [

31] with restricted access to ensure participant confidentiality. Data was de-identified by assigning each participant an ID number to maintain anonymity. Regular audits were conducted periodically to ensure data confidentiality and correctness.

2.7. Data Analysis

All analyses were conducted using R version 4.3.3 [

32]. The following packages were used: dplyr [

33], ggplot2 [

34], corrplot [

35], GGally [

36], car [

37], MASS [

38], tidyr [

39], psych [

40], readr [

41], sjPlot [

42], tableone [

43], flextable [

44], and officer [

45].Descriptive statistics were calculated for demographic variables, housing scores, and patterns of drug use. Means and standard deviations were reported for continuous variables and counts and percentages for categorical variables.

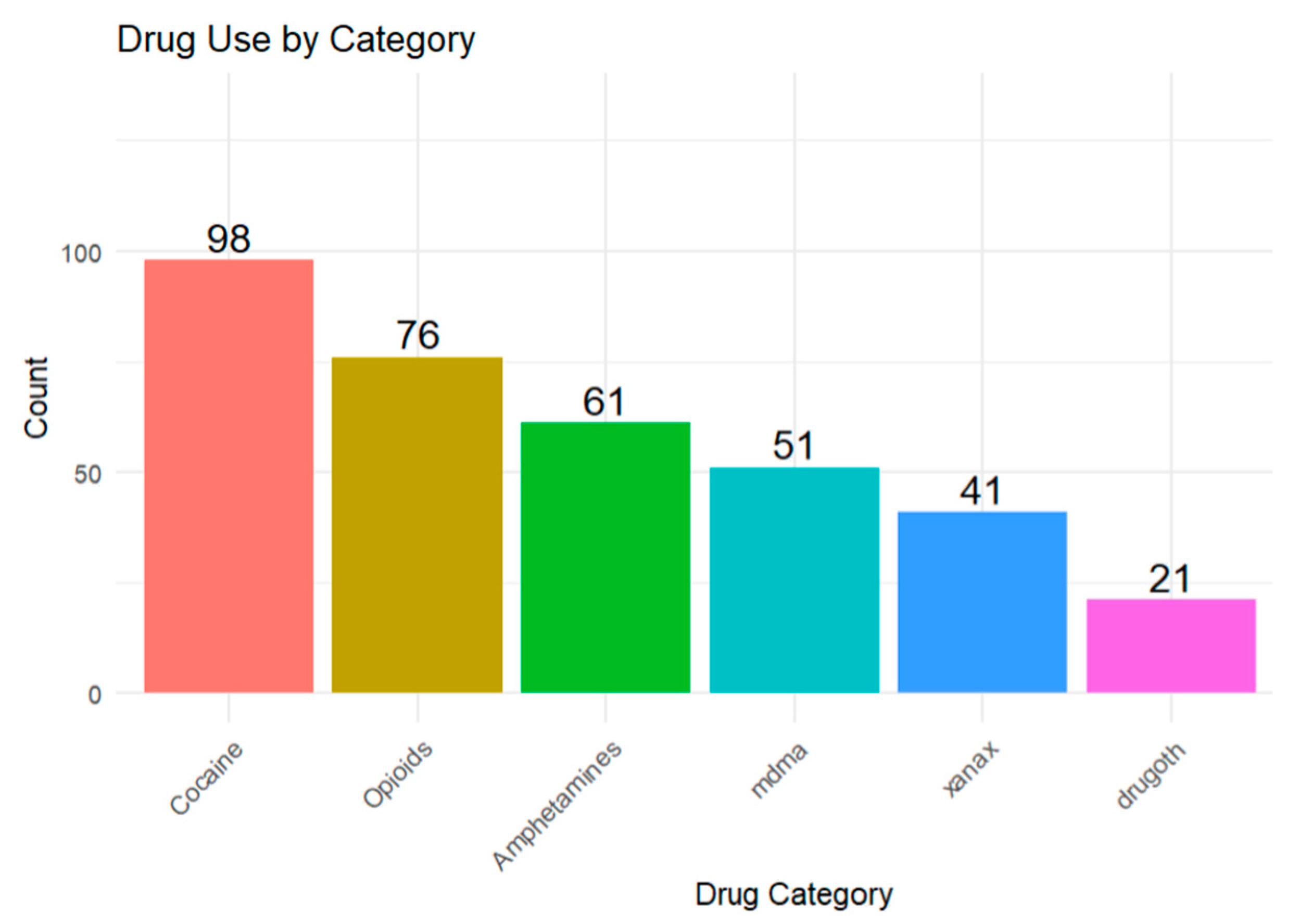

Drugs with similar mechanisms of action were grouped: The group ‘Opioids’ contained drugs like fentanyl, codeine, oxycontin, heroin, and nitazenes. Methamphetamine and Adderall made up the group Amphetamine, while cocaine was used broadly for cocaine and crack use. The Housing Instability Scale (HIS) was used to assess potential housing instability in the sample [

29]. Descriptive statistics were calculated for the housing instability score using the ‘dplyr’ package [

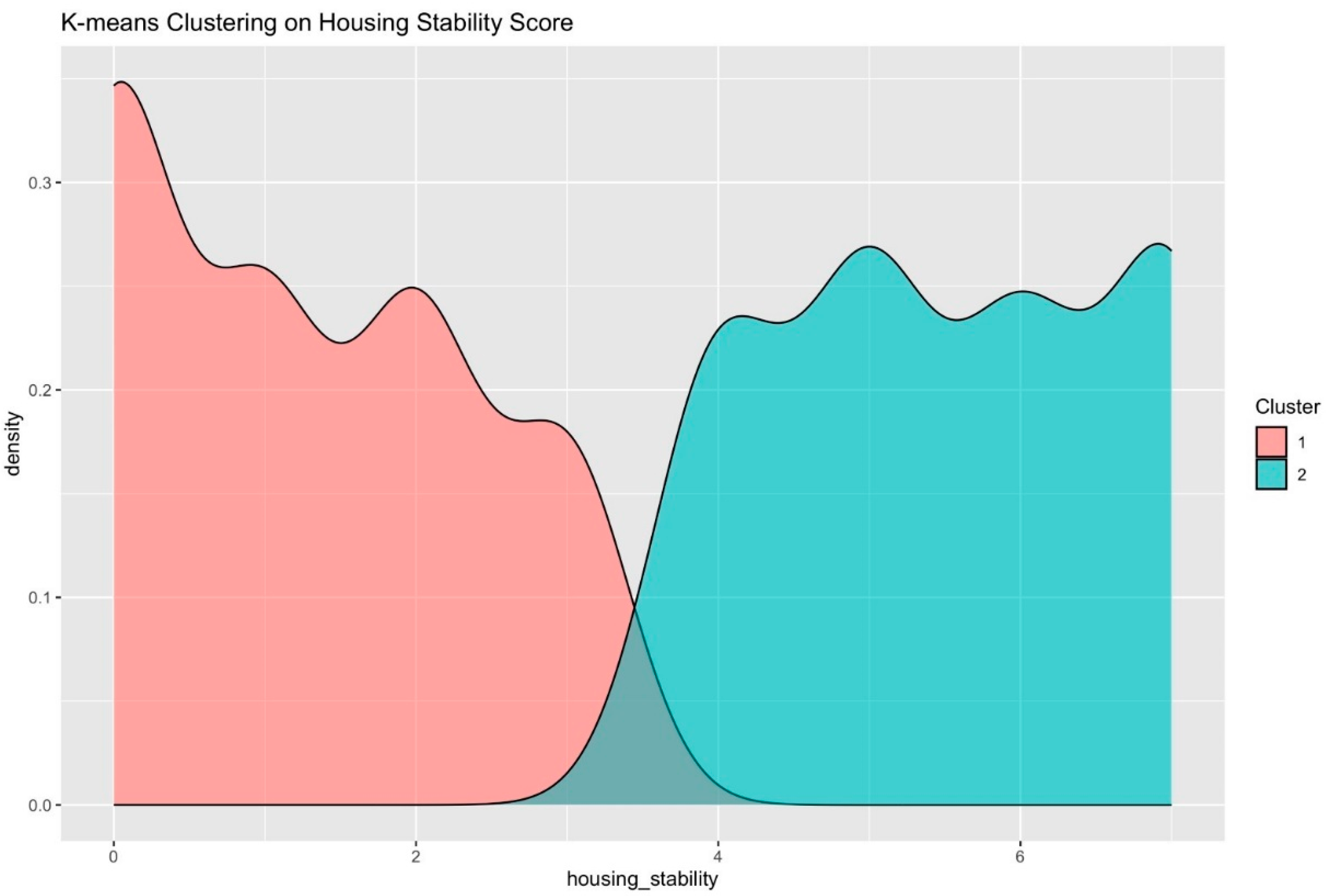

33]. Data visualization was conducted using the ‘ggplot2’ package, in which a bar plot and a kernel density plot were used to assess the shape of the distribution. The density plot was reviewed to assess where natural divisions in the housing instability score occurred [

59]. To prepare the data for cluster analysis, scaling was performed to standardize the score. K-means cluster analysis was performed using base R with k=2 (due to the appearance of two natural clusters in the data) and with 25 random starts to ensure model stability. Cluster assignments were visualized using density plots. As a secondary validation strategy, we applied Gaussian Mixture Modeling (GMM) using the ‘mclust’ package. A two-component model (G=2) was fit to the housing stability scale to estimate probabilistic classifications based on underlying normal distributions. Model fit statistics, including Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC), were reviewed to assess model adequacy. Model summaries and classification plots were generated to visualize the results. All analyses were conducted on a complete-case dataset, excluding participants with missing values on any of the housing stability scale items.

Logistic regression models were used to examine the association between housing stability and health outcomes. Both crude and adjusted models were estimated as follows:

Crude models included housing stability as the sole predictor.

Adjustment models controlled for relevant confounders such as SSP use, employment status, and use of specific drug classes (example: opioids, amphetamines).

Model results were presented as Odds Ratios (OR) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs), along with corresponding p-values. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Demographic Characteristics

A total of 164 participants who use drugs in an urban setting in the Southeastern US, participated in this study. The average age of participants was 41.17 (SD = 13.8), with a bimodal distribution in age groups. The minimum age was 18 and the maximum was 72. Of the 164 participants, 63.4% (n=104) identified as male, 34.8% (n=57) identified as female, and 1.8% (n=3) chose neither. The majority of participants (79.9%, n=131) were Black or African American, followed by White participants (15.9%, n=26), while other racial groups constituted 4.2% (n=7). Among participants, 35.3% (n=49) were unemployed, 21.9% (n=36) were fully employed, and 18.2% (n=30) were self-employed. Additionally, 13.4% (n=22) reported part-time employment, and 11.2% (n=18) constituted other sources of income. The majority of participants (34.8%, n=57) had completed high school or obtained a GED, followed by 23.8% (n=39) who had some college education. Additionally, 17.7% (n=29) had some high school education, and other levels of education constituted 11.6% (n=19). 37 of the 164 participants (22.6%) reported using a syringe services program (SSP), while 76.4% (n = 124) of the study population did not. 3 (1.8%) individuals did not answer this question. Details are illustrated in

Table 1.

3.2. Reported Drug Use

The most commonly used drug was cocaine (59.8%, n = 98), followed by opioids (46.3%, n = 76). 37.2% (n = 61) of people used amphetamines, while about 31% (n = 51) used MDMA. 25% (n = 41) used Xanax, and about 13% (n = 21) of participants used drugs other than the ones mentioned above. The ‘other drugs’ category consists of drugs like buprenorphine, nitazene, methadone, ketamine, etc. Details are illustrated in

Figure 1.

3.3. Housing Instability Scale Cut-Off

HIS scores range between 0 and 7, with higher scores indicating greater housing instability. The mean housing score overall for this study was 3.23 (SD = 2.43); SSP users had higher score with a mean of 4.57 (SD = 2.34).

The k-means cluster analysis revealed two distinct clusters, cluster 1, representing those with scores of 0-3 (stably housed/stability) on the housing instability scale, and cluster 2, representing those with scores of 4-7 (unstably housed/instability) on the housing instability scale (

Figure 2) which was corroborated by the density plot (

Figure A1). Similar results were found using GMM methodology, with two distinct classifications. Cluster 1, representing those with scores of 0-3 on the housing instability scale, and cluster 2, representing those with scores of 4-7 on the housing instability scale (

Figure A2).

3.4. Housing Stability and Health Outcomes

Multivariate logistic regression analyses were conducted to examine associations between housing stability and various health outcomes among participants. Details are illustrated in

Table 2.

3.4.1. Overdose

Housing stability was not significantly associated with overdose after adjustment (adjusted OR = 1.17, 95% CI: 0.94-1.48, p = 0.178). However, SSP use was significantly associated with higher odds of overdose (adjusted OR = 4.04, 95% CI: 1.42-11.76, p = 0.009).

3.4.2. Infections

Housing instability was significantly associated with higher odds of reporting infections (adjusted OR = 1.55, 95% CI: 1.16-2.21, p = 0.0064). SSP use (adjusted OR = 3.92, 95% CI: 1.18-13.88, p = 0.0273) and opioid use (adjusted OR = 15.03, 95% CI: 2.67-284.90, p = 0.0121) were also found to be significantly associated with increased odds of infections.

3.4.3. Wounds

Though an association was found between housing instability and wounds, it was non-significant (adjusted OR = 1.28, 95% CI: 0.99 - 1.69, p = 0.0667). SSP was significantly associated with wounds (adjusted OR = 4.50, 95% CI: 1.38-15.80, p = 0.0142), whereas opioid use was not significantly associated (adjusted OR = 1.77, 95% CI: 0.50-7.24, p = 0.392).

3.4.4. Blackouts

Housing instability was significantly associated with increased odds of blackouts (adjusted OR = 1.47, 95% CI: 1.05 - 2.29, p = 0.0457). SSP use (adjusted OR = 4.89, 95% CI: 0.74-98.00, p = 0.161) and receiving unemployment benefits (AOR = 4.89, CI = 0.74–98.00, p = 0.161) were not statistically significant.

3.4.5. Seizures

Both housing instability (adjusted OR = 1.54, 95% CI: 1.09-2.37, p = 0.0257) and Xanax use (adjusted OR = 8.03, 95% CI: 1.84-43.35, p = 0.0078) were significantly associated with increased odds of seizures. Opioid use was also found to be marginally associated with the odds of reporting seizures (adjusted OR = 6.77, 95% CI: 1.19 - 65.16, p = 0.0530)

4. Discussion

This study aimed to characterize the housing status of people who use drugs in an urban setting in the Southeastern US, to examine the cut-off score for the HIS, and to examine the relationship between housing status and health outcomes, like infections, opioid-related overdoses, wounds, seizures, and blackouts. Our findings revealed significant associations between housing instability and the abovementioned adverse health outcomes. When confounders were adjusted for, housing status was not a strong predictor of overdose risk. However, it had a positively significant association with the others: infections, wounds, seizures, and blackout risks.

Housing is an independent determinant of health across all populations, regardless of drug use status [

60,

61,

62]. Unstable housing has been associated with several adverse health outcomes, including obesity, cardiovascular diseases [

61], mental disorders [

63], infectious diseases like HIV, viral hepatitis [

6,

64], and limited healthcare access [

65]. Identifying individuals who are unstably housed or at imminent risk of homelessness is critical in implementing timely and effective interventions.

Identifying a cutoff score for the HIS allows for meaningful interpretation of the scale to quantify housing as an independent determinant of health in research, like other screening tools, such as how the PHQ-9 is used as a screening tool for depression [

66]. In the context of this study, clinicians would benefit from having meaningful cutoff scores for the Housing Instability Scale (HIS) [

29] to identify unstably housed patients, which would, in turn, help them understand disease patterns and curate preventive and targeted interventions for their patients based on housing insecurity. This is one of many reasons why establishing a validated cutoff score for the HIS is essential in the field of research, healthcare, and public health. Our study identified the cutoff scores for the HIS as 0-3 (stably housed/stability) and 4-7 (unstably housed/instability). Cutoff validation of HIS should be replicated in other studies.

4.1. Housing Instability and Health Outcomes

The relationship between housing stability and adverse health outcomes is well-documented. Housing instability is significantly associated with several health outcomes. A study conducted in Chicago found a significant positive association between housing instability and increased lifetime overdose count among people who inject drugs (PWID) [

46]. This highlights the critical role that stable housing plays in protecting the health of vulnerable populations such as PWUD [

47]. To be specific, higher housing instability scores were associated with increased odds of infections (Adjusted OR: 1.55, 95% CI: 1.16 – 2.21, p = 0.0064), blackouts (AOR: 1.47, 95% CI: 1.05 – 2.29, p = 0.0457), and seizures (AOR: 1.54, 95% CI: 1.09 – 2.37, p = 0.0257) in our sample. Chiang et al. (2022) found that PWID who are unstably housed have an increased risk of infections, particularly HIV and HCV [

48]. A systematic review conducted by Arum et al. (2021) also shows that PWUD who are unstably housed or experienced homelessness are 39% more likely to be diagnosed with HIV and have a 65% chance of HCV infection due to high-risk behaviors [

6]. A global modeling study estimates that 17.2% and 19.4% of new cases of HIV and HCV, respectively, among PWID in high-income countries such as the U.S. are unstably housed [

23]. It also suggests that individuals experiencing housing instability may be at elevated risk of engaging in health-compromising behaviors or experiencing conditions that predispose them to these adverse outcomes [

6,

49]. Beyond physical health, housing instability exposes individuals to increased risk of victimization, compounding mental health issues, which can further aggravate substance use outcomes [

6].

Although housing instability had a crude association with overdose (Crude OR: 1.34), the adjusted model revealed no statistically significant relationship (AOR: 1.17, p = 0.178). This suggests that other variables, such as SSP use or unemployment, may also be at play. Cano et al. (2023) found that states with higher homelessness rates had higher overdose mortality rates across the United States [

50]. Another study in Boston revealed that the leading cause of death among adults experiencing homelessness was overdose, with synthetic opioids accounting for 91% of those deaths [

2].

Similarly, while the association with wounds was not statistically significant (AOR: 1.28, p = 0.0667), it approached significance and may warrant further investigation with a larger sample.

4.1.1. Role of SSP Use

Syringe Service Program (SSP) use emerged as a strong and consistent predictor in our sample across multiple health outcomes. Individuals who patronized SSP had significantly increased odds of experiencing overdoses (AOR: 4.04, 95% CI: 1.42 – 11.76), infections (AOR: 3.92, 95% CI: 1.18 – 13.88), and wounds (AOR: 4.50, 95% CI: 1.38 – 15.80). This supports the notion that SSP users represent a high-risk subgroup of PWUD, some of whom may have started patronizing this service after experiencing complications such as infections from unsafe drug injection practices [

51]. A study on a syringe service organization in Washington DC showed that 67% of its users were either homeless or unstably housed, with about a third reporting that their housing conditions impact their access to primary health care [

52]. A systematic review conducted by Mackey KM et al. (2023) highlights the fact that syringe exchange programs do not increase drug injection frequency but play a vital role in reducing the incidence of infections such as HIV and HCV, increasing naloxone education and possession, and linkage to care when necessary [

53]. While SSP effectively reduces the risk of HIV and hepatitis C, expanding the services to include wound care and the management of other skin infections would help address this gap [

49].

4.1.2. Substance Use as a Confounder

Certain drug use behaviors also contributed to adverse health outcomes. Opioid use was significantly associated with infections (AOR: 15.03, p = 0.0121), and marginally associated with seizures (AOR: 6.77, p = 0.0530) in our study, highlighting opioid use’s role in driving adverse health outcomes. This aligns with existing literature, which suggests that PWUD who are unstably housed are more likely to suffer from infections due to their limited access to healthcare, lack of water for personal hygiene, and care of injection-related wounds [

47,

54]. Additionally, Xanax use was strongly associated with seizures (AOR: 8.03, p = 0.078) in our sample. This is biologically plausible as the abrupt withdrawal of benzodiazepines like alprazolam (Xanax) has been found to induce seizures, especially when combined with opioids [

55].

4.1.3. Public Health Impact

These study findings highlight the urgent need for housing support among PWUD. The housing-first approach, which offers people housing regardless of their drug-use history, has been found to be effective in reducing substance use and its health-related outcomes among PWUD [

6,

47]. Researchers, clinicians, and policy makers should support housing-first approaches when designing programs with PWUD due to the approach’s success in reducing negative health effects due to substance use. Secondly, syringe service programs can expand to include primary healthcare, including wound care, to reduce the transmission and complications of infections, overdose education, and mental health services [

49]. Lastly, this study indicated that unemployment was a strong predictor of an overdose. Economic empowerment through job training and integration could help address the root cause of drug-related harm and unstable housing. Implementing these comprehensive interventions that combine housing support and health services is crucial in improving health outcomes among this population.

4.1.4. Limitations

There were several limitations in this study. Firstly, it was a cross-sectional study in a single urban area; therefore, causality cannot be determined. Repeating this study in other urban areas with PWUD and people who do not use drugs will help to further validate the HIS cutoff proposed here and the associations between housing and negative health outcomes due to substance use. Secondly, self-reported data on substance use may be subject to recall and social desirability bias. In future studies, the use of biomarkers to validate substance use and infections would enhance data accuracy. Thirdly, another limitation in this study is the sample size. The small sample size likely contributed to the wide confidence intervals observed in the analysis. Increasing the sample size in future research would enhance the precision of estimates, narrow confidence intervals, and improve the generalizability of findings.

5. Conclusions

This study highlights the complex interaction between housing stability and health outcomes among PWUD in an urban setting. While housing instability was strongly associated with health outcomes such as infections, wounds, blackouts, and seizures, other predictors such as SSP use and unemployment were found to be strong predictors. This underscores the multifaceted nature of the problem that requires a multifaceted approach to intervention. Some of these approaches include housing support, employment workshops for this population, and the expansion of syringe service programs to include primary healthcare. Addressing these structural determinants of health is essential for reducing disparities and improving health outcomes among PWUD in urban settings.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, F.S., S.F.C., D.J.S., B.K, and S.Z.; methodology, F.S., S.F.C., D.J.S., and S.Z.; formal analysis, F.S., S.F.C., D.J.S., and V.L.; data curation F.S., S.F.C., S.Z., E.R., R.M., and B.K; writing—original draft preparation, F.S., DJS., N.C., and L.V; writing—review and editing, F.S., S.F.C., D.J.S., N.C, S.Z., E.R., M.Z., and H.H.; visualization, F.S., D.J.S., and L.V; supervision, S.F.C, and D.J.S; project administration, F.S., S.F.C., and D.J.S; funding acquisition, S.F.C, B.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by The Injury Prevention Research Center at Emory (IPRCE) Core’s Pilot Research Program (PReP), CDC-funded: Funding source is R49CE003072; Emory award ID: 0000047964. Author DJS is currently supported by the National Institutes of Health/National Institutes of Nursing Research under award K01NR021272.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of Emory University IRB STUDY00006583 approved this study, date of approval October 16, 2023

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. Written informed consent has been obtained from the participants to publish this paper.

Data Availability Statement

Data will not be shared publicly due to the sensitive nature of data collected from people who use drugs.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the community of harm reductionists, public health practitioners, and people with lived and living experience who contributed to the study with their knowledge, time, and passion for keeping people who use drugs safer from the unregulated drug supply.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| United States |

US |

| PWID |

People who inject drugs |

| PWUD |

People Who Use Drugs |

| SSP |

Syringe Services Program |

| HIS |

Housing Instability Scale |

| AOR |

Adjusted Odds Ratio |

| OR |

Odds Ratio |

| CI |

Confidence Interval |

| MD |

Doctor of Medicine |

| PhD |

Doctor of Philosophy |

| GED |

General Educational Development |

| R |

R Programming Language (Statistical Computing) |

| GMM |

Gaussian Mixture Modeling |

| BIC |

Bayesian Information Criterion |

| MPlus |

MPlus Statistical Software |

| mclust |

Model-based Clustering R Package |

| HCV |

Hepatitis C Virus |

| HIV |

Human Immunodeficiency Virus |

| IRB |

Institutional Review Board |

Appendix A

Figure A1.

Density Plot of Housing Scale (0-7).

Figure A1.

Density Plot of Housing Scale (0-7).

Figure A2.

Classification of Housing Instability Scores Based on Gaussian Mixture Modeling. Cluster 1 represents those with low housing instability (scores 0-3) and cluster 2 represents those with high housing instability (scores 4-7).

Figure A2.

Classification of Housing Instability Scores Based on Gaussian Mixture Modeling. Cluster 1 represents those with low housing instability (scores 0-3) and cluster 2 represents those with high housing instability (scores 4-7).

References

- Goldshear, J.L.; Corsi, K.F.; Ceasar, R.C.; et al. Housing and Displacement as Risk Factors for Negative Health Outcomes Among People Who Inject Drugs in Los Angeles, CA, and Denver, CO, USA. Preprint Res Sq. 17 August 4758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fine, D.R.; Dickins, K.A.; Adams, L.D.; et al. Drug Overdose Mortality Among People Experiencing Homelessness, 2003 to 2018. JAMA Netw. Open 2022, 5, e2142676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnold, E.M.; Strenth, C.R.; Hedrick, L.P.; et al. Medical Comorbidities and Medication Use Among Homeless Adults Seeking Mental Health Treatment. Community Ment Health J. 2020, 56, 885–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldridge, R.W.; Story, A.; Hwang, S.W.; et al. Morbidity and mortality in homeless individuals, prisoners, sex workers, and individuals with substance use disorders in high-income countries: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Lancet. 2018, 391, 241–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meckstroth, J.A. Ancillary Services to Support Welfare to Work; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation: Washington, DC, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Arum, C.; Fraser, H.; Artenie, A.A.; et al. Homelessness, unstable housing, and risk of HIV and hepatitis C virus acquisition among people who inject drugs: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Lancet Public Health. 2021, 6, e309–e323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. Housing instability: Healthy People 2030. Available online: https://health.gov/healthypeople/objectives-and-data/social-determinants-health/literature-summaries/housing-instability (accessed on February 6, 2025).

- National Alliance to End Homelessness. State of Homelessness: 2023 Edition. Available online: https://endhomelessness.org/homelessness-in-america/homelessness-statistics/state-of-homelessness/ (accessed on December 3, 2024).

- Tsai, J. Lifetime and 1-year prevalence of homelessness in the US population: Results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions-III. J. Public Health (Oxf). 2018, 40, 65–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Coalition for the Homeless. Substance Use and Homelessness; Bringing America Home: Washington, DC, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Baldwin, G.T.; Seth, P.; Noonan, R.K. Continued Increases in Overdose Deaths Related to Synthetic Opioids: Implications for Clinical Practice. JAMA 2021, 325, 1151–1152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doran, K.M.; Fockele, C.E.; Maguire, M. Overdose and Homelessness-Why We Need to Talk About Housing. JAMA Netw Open. 202, 5, e2142685. Published on . https://doi/org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.42685. 4 January.

- Wiens, K.; Nisenbaum, R.; Sucha, E.; et al. Does Housing Improve Health Care Utilization and Costs? A Longitudinal Analysis of Health Administrative Data Linked to a Cohort of Individuals with a History of Homelessness. Med. Care 2021, 59, S110–S116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koh, K.A.; Racine, M.; Gaeta, J.M.; et al. Health Care Spending and Use Among People Experiencing Unstable Housing In The Era of Accountable Care Organizations. Health Aff (Millwood). 2020, 39, 214–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Annett, J.; Dickson, M.; Tillson, M.; Leukefeld, C.; Webster, J.M.; Staton, M. Selected Resource Insecurities and Abstinence Self-Efficacy Among Urban and Rural Incarcerated Women with Opioid Use Disorder. J. Health Care Poor Underserved 2024, 35, 1068–1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glynn, T.R.; Khanna, S.S.; Hasdianda, M.A.; et al. Informing Acceptability and Feasibility of Digital Phenotyping for Personalized HIV Prevention among Marginalized Populations Presenting to the Emergency Department. Proc. Annu. Hawaii Int. Conf. Syst Sci. 2024, 57, 3192–3200. [Google Scholar]

- Glynn, T.R.; Khanna, S.S.; Hasdianda, M.A.; O'Cleirigh, C.; Chai, P.R. Characterizing syndemic HIV risk profiles and mHealth intervention acceptability among patients in the emergency department. Psychol. Health Med. 2025, 30, 30–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donoghue, C.; Reinschmidt, R.S.; Chow, L. Sense of belonging in a majority-minority Hispanic Serving Institution. J. Latinos Educ. 2024, 24, 235–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, C.M.; Simmons, C.; Guerrero, M.; et al. Domestic Violence Housing First Model and Association With Survivors' Housing Stability, Safety, and Well-being Over 2 Years. JAMA Netw. Open 2023, 6, e2320213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodman-Williams, R.; Simmons, C.; Chiaramonte, D.; et al. Domestic violence survivors' Housing Stability, safety, and Well-Being Over Time: Examining the Role of Domestic Violence Housing First, Social Support, and Material Hardship. Am. J. Orthopsychiatry 2023, 93, 402–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Compton, P. The United States opioid crisis: Big pharma alone is not to blame. Prev. Med. 2023, 177, 107777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Degenhardt, L.; Peacock.; Colledge, S.; et al. Global Prevalence of Injecting Drug Use and Sociodemographic Characteristics and Prevalence of HIV, HBV, and HCV in people Who Inject Drugs: A Multistage Systematic Review. Lancet Glob. Health 2017, 5, e1192–e1207. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2214-109X(17)30375-3. Correction in Lancet Glob. Health 2018, Jan, 6, e36. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2214-109X(17)30446-1.

- Stone, J.; Artenie, A.; Hickman, M.; et al. The Contribution of Unstable Housing to HIV and Hepatitis C Virus Transmission Among People Who Inject Drugs Globally, Regionally, and at Country Level: A Modelling Study. Lancet Public Health. 2022, 7, e136–e145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jose, R.; D'Amico, E.J.; Klein, D.J.; Rodriguez, A.; Pedersen, E.R.; Tucker, J.S. In Flux: Associations of Substance Use with Instability in Housing, Employment, and Income Among Young Adults Experiencing Homelessness. PLoS ONE. 2024, 19, e0303439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miler, J.A.; Carver, H.; Masterton, W.; et al. What treatment and services are effective for people who are homeless and use drugs? A systematic 'Review of Reviews'. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0254729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luchenski, S.; Maguire, N.; Aldridge, R.W.; et al. What Works in Inclusion Health: Overview of Effective Interventions for Marginalised and Excluded Populations. Lancet 2018, 391, 266–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wooditch, A.; Mbaba, M.; Kiss, M.; Lawson, W.; Taxman, F.; Altice, F.L. Housing Experiences Among Opioid-Dependent, Criminal Justice-Involved Individuals in Washington, D.C. J. Urban Health. 2018, 95, 61–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baxter, A.J.; Tweed, E.J.; Katikireddi, S.V.; Thomson, H. Effects of Housing First Approaches on Health and Well-Being of Adults Who Are Homeless or at Risk of Homelessness: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2019, 73, 379–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farero, A.; Sullivan, C.M.; López-Zerón, G.; et al. Development and Validation of The Housing Instability Scale. J. Soc. Distress Homeless 2024, 33, 142–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muthen, L.K.; Muthen, B.O. Mplus User's Guide: Statistical Analysis with Latent Variables: User's Guide; Muthen: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Harris, P.A.; Taylor, R.; Minor, B.L.; Elliot, V.; Fernandez, M.; O'Neal, L.; McLeod, L.; Delacqua, G.; Delacqua, F.; Kirby, J.; Duda, S.N.; REDCap Consortium. The REDCap Consortium: Building an International Community of Software Platform Partners. J. Biomed. Inform. 2019, 95, 103208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- RStudio Team. RStudio: Integrated Development Environment for R (Version 2023.09.1); Posit Software, PBC: Boston, MA, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Wickham, H.; Francois, R. , Henry, L.; Muller, K. dplyr: A Grammar of Data Manipulation (Version 1.1.4), 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Wickham, H.; Francois, R.; Henry, L.; Muller, K. ggplot2: Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, T.; Simko, V. coorplot: Visualization of a Correlation Matrix (Version 0.92), 2021. Available online: https://CRAN.R-project.org/pakage=corrplot.

- Schloerke, B.; Crowley, J.; Cook, D.; Hofmann, H.; Wickham, H.; Briatte, F.; Marbach, M.; Gleason, K. GGally: Extension to 'ggplot2' (Version 2.2.1), 2024. Available online: https://CRAN.R-project.org/pakage=GGally.

- Fox, J.; Weisberg, S. An R Companion to Applied Regression, 3rd ed.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Venables, W.N.; Ripley, B.D. Modern Applied Statistics with S, 4th ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Wickham, H.; Girlich, M. tidyr: Tidy Messy Data (Version 1.3.1). 2024. Available online: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=tidyr.

- Revelle, W. psych: Procedures for Psychological, Psychometric, and Personality Research (Version 2.4.2); Northwestern University: Evanston, IL, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Wickham, H.; Hester, J. , Bryan, J. readr: Read Rectangular Text Data (Version 2.1.4). 2023. Available online: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=readr.

- Ludecke, D. sjPlot: Data Visualization for Statistics in Social Science (version 2.8.14). 2023. Available online: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=sjPlot.

- Yoshida, K.; Bohn, J.; Schuster, T. tableone: Create 'Table 1' to Describe Baseline Characteristics (Version 0.13.2). 2024. Available online: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=tableone.

- Gohel, D. flextable: Functions for Tabular Reporting (Version 0.0.5). 2024. Available online: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=flexable.

- Gohel, D. Officer: Manipulation of Microsoft Word and PowerPoint Documents (Version 0.6.6). 2024. Available online: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=officer.

- Kristensen, K.; Williams, L.D.; Kaplan, C.; et al. A Novel Index Measure of Housing-Related Risk as a Predictor of Overdose Among Young People Who Inject Drugs and Injection Networks. Preprint. Res Sq. 26 June 3083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballard, A.M.; Kesich, Z.; Crane, H.M.; et al. Rural Houselessness Among People Who Use Drugs in the United States: Results from the National Rural Opioid Initiative. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2025, 266, 112498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiang, J.C.; Bluthenthal, R.N.; Wenger, L.D.; Auerswald, C.L.; Henwood, B.F.; Kral, A.H. Health Risk Associated with Residential Relocation Among People Who Inject Drugs in Los Angeles and San Francisco, CA: A Cross-Sectional study. BMC Public Health 2022, 22, 823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cahn, B.A.; Bartholomew, T.S.; Patel, H.P.; Pastar, I.; Tookes, H.E.; Lev-Tov, H. Correlates of injection-related wounds and skin infections amongst persons who inject drugs and use a syringe service programme: A single Center Study. Int. Wound J. 2021, 18, 701–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cano, M.; Oh, S. State-level Homelessness and Drug Overdose Mortality: Evidence from US panel data. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2023, 250, 110910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartholomew, T.S.; Tookes, H.E.; Bullock, C.; Onugha, J.; Forrest, D.W.; Feaster, D.J. ; Examining Risk Behavior and Syringe Coverage Among People Who Inject Drugs Accessing a Syringe Services Program: A Latent Class Analysis. Int. J. Drug Policy 2020, 78, 102716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz, M.S.; Williams, A.; O'Rourke, A.; MacIntosh, E.; Moné, S.; Clay, C. ; The Impact of Housing Insecurity on Access to Care and Services Among People Who Use Drugs in Washington, DC. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 7561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mackey, K.M.; Beech, E.H.; Williams, B.E.; et al. Effectiveness of Syringe Service Programs: A systematic Review; Department of Veterans Affairs (US): Washington, DC, USA, 2023; Available online: https://ncbi.nlm.nij.gov/books/NBK598959/ (accessed on July 2,2025).

- Barocas, J.A.; Eftekhari Yazdi, G.; Savinkina, A.; et al. Long-Term Infective Endocarditis Mortality Associated With Injection Opioid Use in the United States: A Modeling Study. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2021, 73, e3661–e3669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballard, A.M.; Falk, D.; Greenwood, H.; et al. Houselessness and Syringe Service Program Utilization Among People Who Inject Drugs in Eight Rural Areas Across the USA: A Cross-Sectional Analysis. Harm Reduct. J. 2023, 20, 157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelley, A.; Piccione, C.; Fisher, A.; Matt, K.; Adreini, M.; Bingham, D. Survey Development: Community Involvement in the Design and Implementation Process. J. Public Health Manag. Pract. 2019, 25 (Suppl. 5), S77–S83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilson, J.D.; Klipp, S.P.; Leon, K.; Liebschutz, J.M.; Merlin, J.; Murray-Krezan, C.; Nolette, S.; Phillips, K.T.; Stein, M.; Weinstock, N.; Hamm, M. “To Not Feel Fake, It Can’t Be Fake”: Co-Creation of a Harm Reduction, Peer-Delivered, Health-System Intervention for People Who Use Drugs. Harm Reduct. J. 2025, 22, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feld, H.; Byard, J.; Elswick, A.; Fallin-Bennett, A. The Co-Creation and Evaluation of a Recovery Community Center Bundled Model to Build Recovery Capital through the Promotion of Reproductive Health and Justice. Addict. Res. Theory 2024, 32, 455–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Qian, J.; Hassan, M.; Zhang, T.; Yang, C.; Zhou, X.; Jia, F. Density Peak Clustering Algorithms: A Review on the Decade 2014-2023. Expert Syst. Appl. 2024, 238, 121860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Lancet. Housing: An Overlooked Social Determinant of Health. Lancet 2024, 403, 1723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sims, M.; Kershaw, K.N.; Breathett, K.; Jackson, E.A.; Lewis, *!!! REPLACE !!!*; Mujahid, M.S.; Suglia, S.F.; on behalf of the American Heart Association Council of Epidemiology and Prevention and Council on Quality of Care and Outcomes Research. Importance of Housing and Cardiovascular Health and Well-Being: A Scientific Statement from the American Heart Association. Circ. Cardiovasc. Qual. Outcomes 2020, 13, e000089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rolfe, S.; Garnham, L.; Godwin, J.; et al. Housing as a Social Determinant of Health and Wellbeing: Developing an Empirically-Informed Realist Theoretical Framework. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 1138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- arXIV. [CrossRef]

- Aadell, C.J.; Saldana, C.S.; Schoonveld, M.M.; et al. Infectious Diseases Among People Experiencing Homelessness: A Systematic Review of the Literature in the United States and Canada, 2003-2022. Public Health Rep. 2024, 139, 532–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

-

Soc. Sci. Med. [CrossRef]

- Constantin, L.; Pasquarella, C.; Odone, A.; et al. Screening for Depression in Primary Care with Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9): A Systematic Review. J. Affect. Disord. 2021, 279, 473–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).