1. Introduction

Ovarian cancer stands as the primary cause of mortality among women with any gynecological cancers [

1]. The incidence of ovarian cancer displays significant variation worldwide, with higher rates reported in developed countries [

2]. The likelihood of developing ovarian cancer increases with age, predominantly affecting postmenopausal women, highlighting age as a significant risk factor [

3]. There are also other factors, like genetic, environmental, and lifestyle status, that may influence this risk [

4]. Unfortunately, patients with ovarian cancer are frequently diagnosed at advanced stages, which significantly decreases survival rates [

5,

6]. The treatment process usually involves a combination of surgery and chemotherapy [

7]. Surgical procedures aim for complete or optimal debulking (residual disease <1cm), requiring bowel, urinary tract, or liver resection, splenectomy, peritonectomy, diaphragmatic stripping, or pelvic and paraaortic lymphadenectomy, in addition to the standard procedures of hysterectomy, adnexectomy, and omentectomy [

8]. Given the disease characteristics, patient-related factors, and the complexity of surgical interventions, women undergoing debulking surgery for ovarian cancer are often transferred to the intensive care unit (ICU) postoperatively, with reported frequencies ranging from 20% to 48% in the literature [

9,

10].

Unplanned ICU admissions are associated with increased mortality, but in many institutions they may routinely admit patients to the ICU after certain ovarian cancer debulking procedures, including primary debulking or after hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy administration [

11]. However, it is imperative to note that routine ICU admissions may be deemed unnecessary and contribute to increased morbidity [

12]. Therefore, to identify the appropriate candidates for ICU admission, several studies have described different patient characteristics and perioperative factors associated with increased risk for ICU admission after surgery for gynecological malignancies [

13]. Indeed, factors like preoperative nutritional status, advanced age, long operative time, and intestinal resection have been evaluated as predictors of length of ICU stay following surgery for ovarian cancer [

12,

14,

15], with prolonged ICU stay often defined as a duration exceeding 48 hours. These predictors can also serve as proxies for overall hospital length of stay and associated morbidity. Our study seeks to contribute to this ongoing research by delineating a patient profile that allows for predicting those patients who are likely to undergo a prolonged ICU stay after surgery for ovarian cancer.

2. Materials and Methods

A single center retrospective review of patients admitted to the ICU following primary, interval or late debulking surgery for ovarian cancer was conducted at a tertiary institution between January 2004 and December 2023. The types of surgeries performed on patients requiring ICU transfer include cytoreductive surgery, extensive peritoneal resections, and procedures involving major vascular or gastrointestinal interventions. ICU admissions were specifically due to significant perioperative complications, such as hemodynamic instability requiring vasopressor support, respiratory compromise necessitating advanced monitoring or intervention, or major surgical complications, including excessive intraoperative blood loss or the need for complex postoperative care. Ethical approval for this study was obtained from the hospital health ethics committee. All patients underwent surgery performed by two specialized gynecologic oncologists, following the guidelines of the European Society of Gynecological Oncology (ESGO), and always with the maximum effort to achieve no residual disease. The anaesthetic management was carried out by a standard and dedicated team of anesthesiologists with expertise in gynecologic oncology surgeries. The decision to transfer the patient to the ICU was made through a collective agreement among the attending surgeon, anesthesiologist, and intensive care unit medical team, based on the patient’s need for vital support, hemodynamic instability, and respiratory indications..

All data were obtained from the hospital’s computerized patient data system. Patients demographic and clinical characteristics such as age, BMI, preoperative albumin serum levels, American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) classification and intraoperative variables such as ascites, pleural effusion, blood loss, operation duration, bowel resection, intraoperative complications, epidural anesthesia and body temperature at the end of the operation were recorded. The primary outcome measure in the study was the length of ICU stay. The first group consisted of patients that were admitted to the ICU < 48 hours and the second group ≥ 48 hours. The 48-hour cut-off was selected because it has been previously used in similar studies to define prolonged ICU stay [

12,

15]. Furthermore, it was chosen as it represented the median length of stay among the patients in this study.

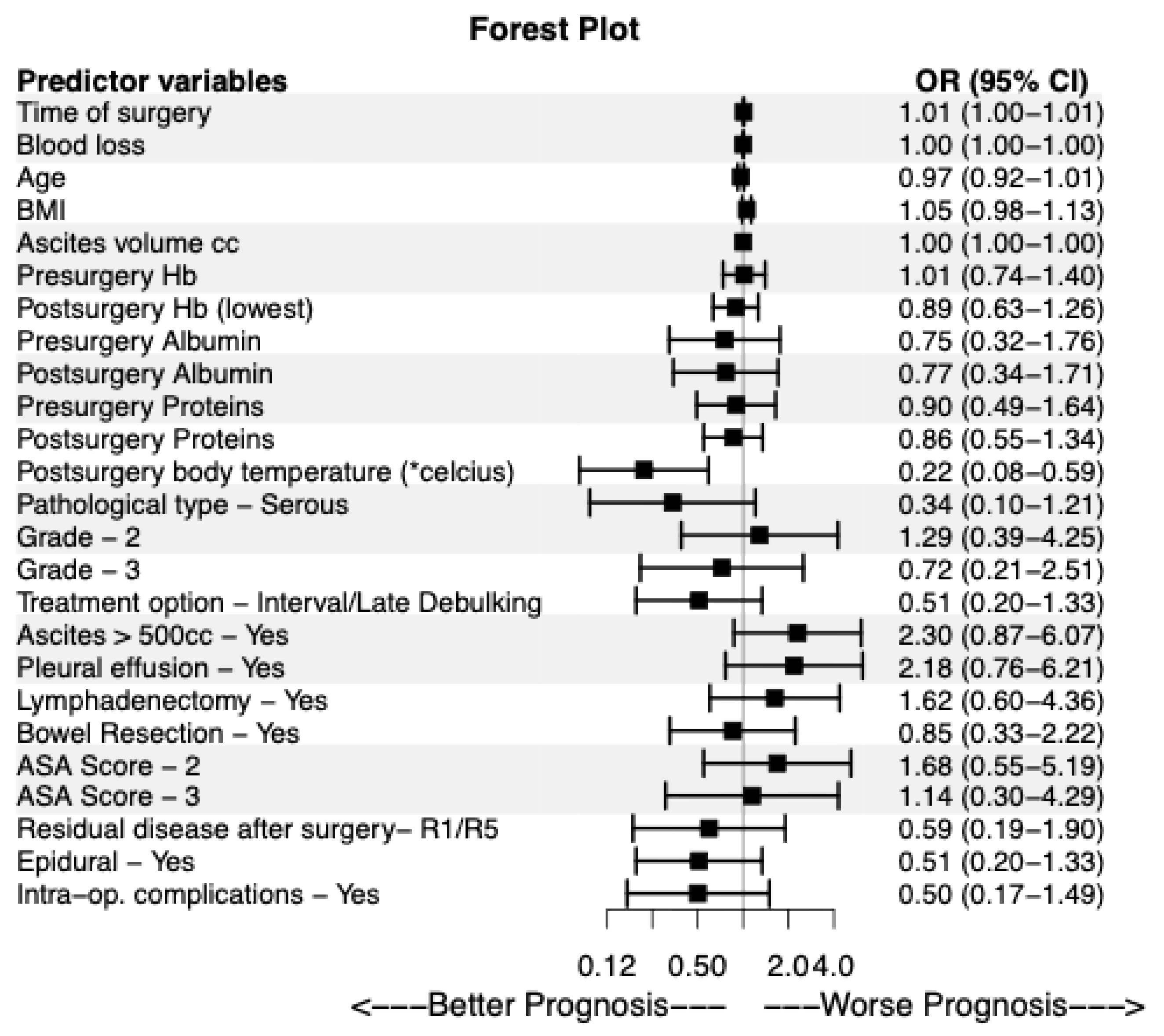

Continuous variables are presented with mean and standard deviation (SD). Group comparisons for continuous variables were made using the t-test for independent samples. For categorical variables group comparisons were made using the chi-squared test. Univariable and multivariable binary logistic regression analysis was performed to assess the independent predictors of prolonged ICU stay (0: <48 hours, 1: ≥ 48 hours). The multivariable binary logistic regression model included all predictor variables that exhibited a p-value less than 0.200 in the univariable binary logistic regression analysis. For visualization purposes a forest plot was employed to display the results of the univariable binary logistic regression using the R package “forestplot”. The level of statistical significance was set at a=0.05. The analyses were conducted using the SPSS software (version 22.0) and the R programming language (version 4.4.1).

3. Results

A total of 74 out of 1045 patients who underwent surgery for ovarian cancer were admitted postoperatively to the ICU. Forty-seven patients (63.5%) had an ICU stay of less than 48-hours (Group A) and 27 (36.5%) stayed at least 48-hours (Group B) in the ICU (

Table 1). Stage III (67.6%) and IV (29.7%) represented the majority of the cases, while only one case was stage I (1.4%) and one case was stage V (1.4%) (

Table 1). Thirty - four patients (45.9%) required support due to hemodynamic instability, 39 patients (52.7%) required mechanical ventilation, and 1 patient (1.4%) required renal replacement therapy (

Table 1).

Comparing group A and group B regarding both the preoperative and intraoperative variables revealed that the preoperative variables did not exhibit significant differences between the two groups, except for the number of neoadjuvant chemotherapy (NACT) cycles, which showed a significant difference among patients who underwent interval/late debulking surgery (

Table 2).

On the other hand, among the intraoperative variables, the time of surgery exhibited significant differences between the two groups (

Table 2) with a mean value of 312.13 (SD =77.09) in group A and a statistically significantly larger mean of 363.15 (SD =91.35) in group B (p=0.013). In addition, the postsurgery body temperature obtained mean 35.87 (SD=0.59) in group A and a statistically significantly smaller mean of 35.06 (SD=0.94) in group B (p<0.001). Of note, the intraoperative blood loss was marginally not statistically significantly different between the two groups (p=0.162), exhibiting a mean of 757.96 (SD=626.91) in group A and a much large mean value of 969.23 (SD=561.26) in group B (

Table 2).

Similar results were obtained in the case of the univariable binary logistic regression analysis (

Table 3). In particular, the time of surgery exhibited a statistically significant odds ratio (OR) of 1.007 (95% Confidence Interval (CI): 1.001-1.013, p=0.016), namely, the odds of ICU stay ≥ 48 hours were 1.007 times greater compared to ICU stay <48 hours, for each increase of the surgery time by one. In other words, as the time of surgery increased, the patient was more likely to belong in group B. Τhe postsurgery body temperature obtained an OR of 0.220 (95% CI: 0.082-0.589, p=0.003), namely as the postsurgery body temperature increased, the patient was more likely to belong in group A. The results of this analysis are visually displayed as well in

Figure 1. All variables with a p-value less than 0.200 in the univariable binary logistic regression were included in the multivariable model (

Table 3). In the multivariable analysis, three factors exhibited statistical significance, the time of surgery (OR: 1.017, 95% CI: 1.002-1.033, p=0.025), and the BMI (OR: 1.215, 95% CI: 1.021-1.446, p=0.028), were associated with increased risk for admission to the ICU for ≥ 48h, while higher postsurgery body temperature (OR: 0.082, 95% CI: 0.013-0.507, p=0.007) significantly decreased the likelihood of prolonged ICU stay (

Table 3).

4. Discussion

Prolonged staying in the intensive care unit (ICU) after ovarian cancer surgery constitutes a critical element in delivering optimal patient care. The identification of factors influencing prolonged ICU stay enables healthcare providers to judiciously allocate resources and formulate strategies for minimizing complications, thereby enhancing recovery of patients after debulking surgery for ovarian cancer. Effectively managing and mitigating these factors in routine clinical practice is imperative to streamline patient care and diminish extended ICU utilization after ovarian cancer surgery. The implementation of enhanced perioperative care protocols (Enhanced Recovery After Surgery - ERAS) and attentive monitoring systems empowers healthcare providers to proactively identify individuals at increased risk for prolonged ICU stays. However, this potential impact requires further study to better understand its role and effectiveness in different clinical settings.

In our study, the most common indications for ICU admission were mechanical ventilation support after major surgery and hemodynamic instability. Extensive traumatic surgical procedures aimed at achieving optimal debulking result in higher rates of significant blood loss, intraoperative complications, and anesthesia-related challenges, highlighting the need for meticulous fluid management and mechanical respiratory support. Approximately 21-36% of these patients require postoperative ICU admission [

15]. In addition to patients' age, comorbidities, and nutritional status, which play a pivotal role in determining ICU admission, the type and duration of surgery also contribute significantly to the decision-making process. [

13].

Age has been identified as an independent predictor for prolonged ICU stay after surgery for gynecologic cancer according to several studies [

12,

14,

16,

17]. In our study age was not significantly different between the groups of patients. Malnutrition is prevalent among oncologic patients and is correlated with a variety of postoperative complications [

12,

14]. Serum albumin levels above 3.5 g/dl, as a proxy for nutritional status, have been associated with a reduced risk of prolonged ICU stay [

12]. However, in our study there was no significant difference in preoperative albumin levels between the two groups. Among other patient characteristics, BMI was associated with increased risk for ICU admission for ≥48h. Obesity has been associated with an increased risk of postoperative complications after ovarian cancer surgery, particularly wound complications, infections and coagulopathy [

18,

19]. From literature review, Wolfberg et al. [

20] found a correlation between a BMI greater than 30 and an elevated rate of ICU admission, while Yao et al. [

9] linked BMI with ICU admission within 30 days postoperatively. In our study, we observed that for each increase in BMI grade, the odds of prolonged ICU stay ≥48 hours increased by 21.5%. Different scoring systems have been developed to classify patients based on comorbidities and performance status, aiming to identify those who may require more intensive postoperative care [

21]. In our study, we utilized the American Society of Anesthesiologists physical status (ASA) classification [

22], to assess the medical comorbidities and estimate likelihood of disease, but we did not observe any significant difference between the two groups. In the last few years, frailty has emerged as a predictor of adverse outcomes following ovarian cancer surgery [

23]. Frailty is a condition in which the individual is in a vulnerable state at increased risk of adverse health outcomes and/or dying when exposed to a stressor [

24]. Yao et al. demonstrated that frailty remained an independent predictor of 30-day ICU admission postoperatively [

9]. Frailty is common among patients with advanced epithelial ovarian cancer and correlated with increased rates of perioperative morbidity and mortality [

23]. Although it is age-related, it does not necessarily follow a linear progression with increasing age [

23].

Regarding intraoperative outcomes, prolonged surgical procedures were found to increase the likelihood of extended ICU admissions. A longer duration of surgery often indicates more complex procedures, a higher risk of intraoperative complications, and the necessity for administering larger and more prolonged doses of anesthetic agents. This makes the recovery process more challenging for these patients and significantly increases the likelihood of their transfer to the ICU. Indeed, the estimated duration of surgery differed significantly between the two groups in our study. Furthermore, epidural anesthesia has been shown to improve survival in ovarian cancer patients, likely due to its ability to reduce the stress response [

25,

26]. In our study, we observed that epidural anesthesia was associated with a reduction in ICU stay, although this finding was not statistically significant. This effect may be attributed to decreased requirements for sedative drugs and enhanced pain management, which could facilitate more efficient patient resuscitation after surgery and promote a smoother recovery from anesthesia.

Hypothermia has been associated with early postoperative complications and mortality among women underwent cytoreductive surgery for ovarian cancer [

27]. Visceral exposure and anesthesia-induced dysfunction of thermoregulatory control are primary factors contributing to intraoperative hypothermia [

28]. Neuraxial anesthesia prevents vaso-constriction and shivering in blocked areas [

29]. Therefore, unwarmed patients become hypothermic. Hypothermia has been shown to have detrimental effects on various physiological processes, including coagulation, susceptibility to infections, drug metabolism and vasoconstriction [

29]. Kaufner et al. demonstrated that prewarming patients undergoing ovarian cancer cytoreductive surgery to 43° C using a forced air warming gown connected to a forced air warmer, during epidural catheter placement and induction of anesthesia, correlated with reduced drop in core temperature and the maintenance of normothermia throughout the surgery [

30]. On the contrary, Long et al. [31] showed that although hypothermia is common among such patients, it was not correlated with increased postoperative complications. In our study, the risk of prolonged admission to the ICU for ≥ 48h was decreased among patients with higher temperature at the end of operation.

The robustness of this investigation is grounded in the execution of all primary procedures within a certified gynecological oncological center with accreditation for advanced ovarian cancer surgery and by two proficient gynecological oncology surgeons. Additionally, the anesthetic interventions were administered by three experienced anesthesiologists well-versed in radical cytoreductive surgeries. Also, the ICU is a referral center for the broader region’s critical cases. However, certain constraints merit attention in our study. Notably, the limited sample size and infrequent occurrences may have hindered the identification of more predictors. Moreover, the data on the kind of epidural drugs used on the operative day were not consistently recorded, and the nature of our analysis is retrospective and from a single center. For this reason, there is a need for more extensive and larger studies involving multiple gynecologic oncology centers.

5. Conclusions

Specific perioperative criteria can predict whether a patient with ovarian cancer may require a prolonged ICU stay. These findings facilitate appropriate preoperative counseling and empower gynecologic-oncologists to identify these patients, that will benefit the most from postoperative ICU admission, contributing to improved resource management in favor of patients.

The data analysis of this retrospective study revealed that, in addition to factors contributing to extended ICU utilization, such as increased BMI and prolonged surgery duration, an additional factor was identified that could reduce this likelihood: a higher body temperature at the end of the operation.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, V.T., G.G. and D.T.; methodology, V.T. and D.T.; software, V.T.; validation, V.T., K.K., I.T., K.C and D.T.; formal analysis, V.T., T.M.; investigation, V.T., K.K., P.T., A.D., D.Z., C.A., F.S.; data curation, V.T., K.K.; writing original draft preparation, V.T, K.K., I.T., T.M.; writing review and editing, V.T., D.T., G.G., E.K.; visualization, V.T. and D.T.; supervision, V.T., G.G.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. As a retrospective review of anonymized patient data, this study did not receive formal ethical approval from the Institutional Review Board of General Hospital of Thessaloniki "Papageorgiou" Greece.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study during their hospitalization for anonymous use of their data for scientific research.

Data Availability Statement

We confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available upon request. However, due to privacy concerns and in accordance with ethical standards and regulations, the data will be provided in a deidentified format to ensure patient anonymity. Requests for data should be directed to the corresponding author via email at theodoulidisvasilis@yahoo.gr

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interests.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ICU |

Intensive Care Unit |

| BMI |

Body Mass Index |

| ESGO |

European Society of Gynecological Oncology |

| SD |

Standard Deviation |

| ASA |

American Society of Anesthesiologists |

| NACT |

NeoAdjuvant ChemoTherapy |

| OR |

Odds Ratio |

| CI |

Confidence Interval |

| ERAS |

Enhanced Recovery After Surgery |

References

- PDQ Adult Treatment Editorial Board. PDQ Cancer Information Summaries [Internet]. National Cancer Institute (US); Bethesda (MD): Mar 14, 2023. Ovarian Epithelial, Fallopian Tube, and Primary Peritoneal Cancer Treatment (PDQ®): Health Professional Version.

- Cabasag CJ, Fagan PJ, Ferlay J, et al. Ovarian cancer today and tomorrow: A global assessment by world region and Human Development Index using GLOBOCAN 2020. Int J Cancer. 2022;151(9):1535-1541. [CrossRef]

- Chan J, Urban R, Cheung M, et al. Ovarian cancer in younger vs older women: a population-based analysis. Br J Cancer. 2006;95(10):1314. [CrossRef]

- Momenimovahed Z, Tiznobaik A, Taheri S, Salehiniya H. Ovarian cancer in the world: epidemiology and risk factors. Int J Womens Health. 2019;11:287-299.

- Ries LAG, Eisner MP, Kosary BK, et al. Editors. SEER cancer statistics review, 1975–2001, National Cancer Institute, Bethesda, MD. Bethesda, MD: http://www.seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2001/.

- Arora T, Mullangi S, Lekkala MR. Ovarian Cancer. [Updated 2023 Jun 18]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2023 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK567760/.

- Coleridge SL, Bryant A, Kehoe S, Morrison J. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy before surgery versus surgery followed by chemotherapy for initial treatment in advanced ovarian epithelial cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2021;7(7):CD005343. Published 2021 Jul 30. [CrossRef]

- Querleu D, Planchamp F, Chiva L, Fotopoulou C, Barton D, Cibula D, Aletti G, Carinelli S, Creutzberg C, Davidson B, Harter P, Lundvall L, Marth C, Morice P, Rafii A, Ray-Coquard I, Rockall A, Sessa C, van der Zee A, Vergote I and duBois A: European Society of Gynaecological Oncology (ESGO) Guidelines for ovarian cancer surgery. Int J Gynecol Cancer 27(7): 1534-1542, 2017. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yao T, DeJong SR, McGree ME, Weaver AL, Cliby WA, Kumar A. Frailty in ovarian cancer identified the need for increased postoperative care requirements following cytoreductive surgery. Gynecol Oncol. 2019;153(1):68-73. [CrossRef]

- Davidovic-Grigoraki M, Thomakos N, Haidopoulos D, Vlahos G and Rodolakis A: Do critical care units play a role in the management of gynaecological oncology patients? The contribution of gynaecologic oncologist in running critical care units. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl) 26(2), 2017. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ross MS, Burriss ME, Winger DG, Edwards RP, Courtney-Brooks M, Boisen MM. Unplanned postoperative intensive care unit admission for ovarian cancer cytoreduction is associated with significant decrease in overall survival. Gynecol Oncol. 2018;150(2):306-310. [CrossRef]

- Díaz-Montes TP, Zahurak ML, Bristow RE. Predictors of extended intensive care unit resource utilization following surgery for ovarian cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2007;107(3):464-468. [CrossRef]

- Thomakos N, Prodromidou A, Haidopoulos D, Machairas N, Rodolakis A. Postoperative Admission in Critical Care Units Following Gynecologic Oncology Surgery: Outcomes Based on a Systematic Review and Authors' Recommendations. In Vivo. 2020;34(5):2201-2208. [CrossRef]

- Amir M, Shabot MM, Karlan BY. Surgical intensive care unit care after ovarian cancer surgery: an analysis of indications. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1997;176(6):1389-1393. [CrossRef]

- Collins A, Spooner S, Horne J, et al. Peri-operative Variables Associated With Prolonged Intensive Care Stay Following Cytoreductive Surgery for Ovarian Cancer. Anticancer Res. 2021;41(6):3059-3065. [CrossRef]

- Brooks SE, Ahn J, Mullins CD, Baquet CR. Resources and use of the intensive care unit in patients who undergo surgery for ovarian carcinoma. Cancer. 2002;95(7):1457-1462. [CrossRef]

- Ruskin R, Urban RR, Sherman AE, et al. Predictors of intensive care unit utilization in gynecologic oncology surgery. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2011;21(8):1336-1342. [CrossRef]

- Cai B, Li K, Li G. Impact of Obesity on Major Surgical Outcomes in Ovarian Cancer: A Meta-Analysis. Front Oncol. 2022;12:841306. Published 2022 Feb 9. [CrossRef]

- Smits A, Lopes A, Das N, et al. Surgical morbidity and clinical outcomes in ovarian cancer - the role of obesity. BJOG. 2016;123(2):300-308. [CrossRef]

- Wolfberg AJ, Montz FJ, Bristow RE. Role of obesity in the surgical management of advanced-stage ovarian cancer. J Reprod Med. 2004;49(6):473-476.

- Sobol JB, Wunsch H. Triage of high-risk surgical patients for intensive care. Crit Care. 2011;15(2):217. [CrossRef]

- Pedrosa E, Silva M, Lobo A, Barbosa J, Mourao J. Is the ASA Classification Universal?. Turk J Anaesthesiol Reanim. 2021;49(4):298-303. [CrossRef]

- Kumar A, Langstraat CL, DeJong SR, et al. Functional not chronologic age: Frailty index predicts outcomes in advanced ovarian cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2017;147(1):104-109. [CrossRef]

- Walston J, Hadley EC, Ferrucci L, et al. Research agenda for frailty in older adults: toward a better understanding of physiology and etiology: summary from the American Geriatrics Society/National Institute on Aging Research Conference on Frailty in Older Adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2006;54(6):991-1001. [CrossRef]

- Shen H, Pang Q, Gao Y, Liu H. Effects of epidural anesthesia on the prognosis of ovarian cancer-a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Anesthesiol. 2023;23(1):390. Published 2023 Nov 29. [CrossRef]

- Tseng JH, Cowan RA, Afonso AM, et al. Perioperative epidural use and survival outcomes in patients undergoing primary debulking surgery for advanced ovarian cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2018;151(2):287-293. [CrossRef]

- Moslemi-Kebria M, El-Nashar SA, Aletti GD, Cliby WA. Intraoperative hypothermia during cytoreductive surgery for ovarian cancer and perioperative morbidity. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;119(3):590-596. [CrossRef]

- Xiong J, Kurz A, Sessler DI, et al. Isoflurane produces marked and nonlinear decreases in the vasoconstriction and shivering thresholds. Anesthesiology. 1996;85(2):240-245. [CrossRef]

- Sessler, DI. Perioperative thermoregulation and heat balance. Lancet. 2016;387(10038):2655-2664. [CrossRef]

- Kaufner L, Niggemann P, Baum T, et al. Impact of brief prewarming on anesthesia-related core-temperature drop, hemodynamics, microperfusion and postoperative ventilation in cytoreductive surgery of ovarian cancer: a randomized trial. BMC Anesthesiol. 2019;19(1):161. Published 2019 Aug 22. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).