1. Introduction

Asphalt pavement has been used a lot in the world due to its advantages of comfortable driving, short recuperation time after construction, fast opening to traffic and convenient renovation. In China, nearly 70% of roads have been using asphalt as surface layer, and the utilization rate in high-grade pavement is more than 95%. As an artificial paving material, asphalt pavement is subjected to climatic changes and vehicle loads, which can lead to deterioration and decay of asphalt materials. Since asphalt is a temperature-sensitive material that exhibits viscous-elastic-plastic properties with changes in temperature, changes in temperature can negatively affect asphalt materials during actual use [

1,

2,

3]. In the high temperature environment, the temperature will have a huge impact on asphalt pavement, mainly manifested as: accelerating asphalt aging, inducing pavement deformation, rutting, congestion and other diseases. It is generally believed that asphalt pavement rutting is caused by the lack of shear strength of asphalt mixtures under high temperature conditions, and studies have shown that [

4,

5], when the temperature is higher than 55 ℃. Asphalt mixture rutting will develop at a centimeter rate, therefore, an effective way to control the generation and development of pavement rutting disease is to reduce the pavement temperature, thereby reducing the external environment of the pavement to produce disease; in the low-temperature environment, the low temperature will also have an adverse effect on the pavement, mainly manifested as follows: the low temperature will make the asphalt pavement cracking, reducing the service life of the pavement. In the rain and snow weather, too low a pavement temperature will make the rain and snow can not be quickly eliminated, which will lead to slippery road surface, resulting in traffic accidents such as loss of control of vehicles. Through the regulation of asphalt pavement temperature, so that the pavement temperature is reduced too low at low temperatures is an effective way to reduce cracking and ice condensation. In order to reduce the impact of temperature on asphalt materials, delay the decay rate of asphalt mixture under the action of temperature, in recent years, scholars at home and abroad according to the characteristics of asphalt proposed a number of improvement measures, mainly from two aspects. On the one hand, it is to improve the pavement material resistance to high temperature, low temperature performance, reduce the temperature sensitivity of the material, such as research and development of rutting-resistant asphalt mixture, cracking-resistant asphalt mixture and so on to respond to the temperature change passively, although a certain effect is achieved, but it is not ideal. On the other hand, to improve the temperature field of asphalt pavement, thereby improving the working temperature range of asphalt mixtures, currently available technologies include mainly include heat reflection technology, pavement water retention and cooling technology, thermal resistance pavement technology, pavement energy conversion technology [

6,

7,

8,

9,

10].

With the development of technology, thermoregulation with phase change materials has become a research direction for scholars at home and abroad. At present, Phase Change Materials (PCM) have been widely utilized in aerospace, refrigeration and other fields [

11,

12,

13,

14,

15]. In construction, phase change energy storage was used to treat building materials (such as gypsum board, wallboard and concrete components, etc.) in the 1990s, and then the research and application of PCM in concrete test blocks, gypsum wallboard and other building materials have been booming. In 1999, a new type of building material, solid-liquid eutectic phase change material (PCM), was successfully developed abroad, and this PCM can be poured into wall panels or lightweight precast concrete panels to keep the indoor temperature suitable [

16,

17,

18,

19]. In addition, many companies in Europe and the United States use PCM to produce and sell outdoor communication wiring equipment and power transformer equipment in a special cabin, which can be maintained at a suitable working temperature in both winter and summer. Tseng et al. used paraffin, n-pentadecane and n-octadecane as phase change materials, urea-formaldehyde resin as a wrapping wall material, prepared a microcapsule composite phase change material, the study showed that the microcapsule on the solid-liquid phase change material core samples have a good wrapping, the latent heat of the phase change in the 109J/g or so [

20]. Cho et al. used n-octadecane as the phase change material and prepared microcapsules phase change materials with polyurea walls by interfacial polymerization method, and the results of DSC experiments showed that the phase change temperature range of the microcapsule composite phase change materials was 29-30°C, and the latent heat of the phase change was up to 110 J/g [

21]. Zhang et al. made EG/PEG composite phase change material by adsorbing PEG into the pores in EG by vacuum impregnation method, and the composite was found to have a good encapsulation effect by SEM and Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR) experimental studies when the mass ratio of EG and PEG in the composite phase change material was not less than 1:7 [

22]. Muhammad Rafiq Kakar et al [

23] prepared tetradecane phase change microcapsules and added them to asphalt to obtain a low temperature phase change modified asphalt with a phase change temperature of 5°C and an enthalpy of 35 J/g. Kun et al [

24] synthesized low-temperature polyurethane solid-solid phase change materials with phase change temperatures ranging from -5°C to -12.5°C and an enthalpy of 47 J/g by using the prepolymer method, and the cooling rate of the polyurethane solid-solid phase change-modified asphalt was significantly reduced when compared to the asphalt without the phase change material. Deng et al. proposed a systematic numerical simulation framework to quantify the effect of phase change materials (PCMs) on the early rutting performance of asphalt concrete pavements. The pavement system was characterized and modeled in terms of material, structure, environment and traffic loading. The results showed that the cumulative rutting depth in asphalt concrete with only 3% PEG/SiO2 added was reduced by 4% after the first week of pavement use [

23,

24,

25]. Gao et al. prepared silica composite phase change materials by sol-gel method and developed a finite element heat transfer model by measuring the boundary conditions and predicted and analyzed its conditioning effect [

26]. Amini et al [

27] showed that nano-CuO as a modified asphalt binder can store heat by heat absorption/excretion to prevent sudden temperature increase/decrease, and nano-CuO as a PCM improved the Tmg of the asphalt binder; the Tpc was reduced by a few degrees, and the C-value was reduced by more than 7°C compared to the pure asphalt binder. Cheng et al [

28] showed that with the increase of PPGC phase change material dosing, the immersion Marshall test and residual stability of asphalt mixtures showed a trend of increasing and then decreasing, in addition, the smaller the aggregate particle size of asphalt mixtures, the earlier the maximum value of immersion Marshall appeared, which indicates that the smaller the particle size, the denser the mixture is, the better the energy transfer in the mixture is relatively.

At present, the research and development of dual-phase change thermoregulation materials for asphalt pavement is in the ascendant [

29]. However, the current research on the application of phase change materials in asphalt mixtures mainly explores the thermoregulation effect of composite phase change materials with phase change temperatures on asphalt mixtures through experiments, but experimental research has certain limitations, while simulation can produce the pavement temperature field under different scenarios and assumptions.

Based on the above background, the objectives of this research determines the asphalt mixture material for the study by selecting the composite shaped phase change material suitable for pavement material and asphalt mixture ratio design, and simulates the temperature regulation effect of phase change material by measuring the internal temperature change of asphalt mixture in the process of warming up indoors. On this basis, the means of finite element simulation analysis of asphalt mixture and asphalt pavement structure internal temperature field analysis, and compared with the measured data. The results of the study are of reference significance for the development of phase change materials for pavements and the research and application of asphalt pavement temperature regulation technology.

2. Experimental Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Raw Materials

2.1.1. Selection and Preparation of Phase Change Materials

In view of the application objectives, application scenarios and functional requirements of phase change materials, phase change materials applied to asphalt pavements should meet the following requirements:

(1) Phase transition temperature

This is the first factor to be considered in the selection of phase change materials, according to the specific working environment of the pavement mainly temperature conditions, the selection of suitable phase change materials, so that its phase change working temperature to meet the desired goal of the proposed regulation of temperature, so as to achieve the purpose of regulating the temperature of the pavement.

(2) Good stability of phase change cycle

Phase change heat storage materials in the asphalt pavement service process by repeated traffic loads and natural environmental factors can give full play to the phase change heat storage function, to realize the phase change reversible cycle, generally through the appropriate encapsulation materials and suitable encapsulation process to achieve.

(3) Good thermal stability (no decomposition at 200°C)

To meet the requirements of high temperature mixing and construction of asphalt mixtures, hot mix hot paving asphalt mixtures are usually heated to 150 ℃ ~ 170 ℃ asphalt, mineral aggregate heated to 180 ℃ ~ 190 ℃. Therefore, the thermal stability of the materials used must withstand the high temperature process of hot mixing and hot paving, in its high temperature mixing, paving, rolling process does not occur thermal decomposition and other chemical reactions, which is also realized through the selection of encapsulated materials and phase change materials.

(4) good chemical compatibility with asphalt

Phase change materials and asphalt mixtures have good chemical compatibility, in the mixing, paving of high-temperature conditions and the use of the process does not occur in the chemical reaction, the material does not deteriorate and maintain the original nature.

Based on the above factors, from the working temperature range of asphalt pavement and asphalt pavement material production, paving and use of the process requirements, comprehensive phase change materials and asphalt compatibility, choose the molecular weight of 1500 polyethylene glycol (PEG1500) as the core material. In order to realize the material's shaping as well as phase change stability and thermal stability, calcium alginate, a reaction product of sodium alginate and calcium chloride, was used as the encapsulation material.

The above core and encapsulation materials were prepared into a composite shaped phase change material by ion substitution. This composite phase change material comprises polyethylene glycol (PEG1500) and calcium alginate. In this material, PEG1500 is used as a phase change core material and is mainly used to regulate the temperature. In contrast, calcium alginate, a reaction product of sodium alginate and calcium chloride, acts as a wall material to encapsulate PEG1500, thus ensuring that the liquid phase does not leak during the phase change process. It also makes the phase change material have certain stability and durability during construction and use. The specific preparation process of the shaped phase change material is as follows:

(1) Sodium alginate powder and calcium chloride were added to deionized water at a temperature of 40° C., respectively, and stirred continuously with a glass rod during the addition process until the sodium alginate powder and calcium chloride particles were fully dissolved to form a 2.5 wt% sodium alginate solution and a 2.5 wt% calcium chloride solution.

(2) Liquid PEG1500 was added to the sodium alginate solution at a temperature of 80° C. The temperature was maintained and stirred at 1000 rpm until homogeneous mixing was achieved to obtain a blend of sodium alginate and PEG1500.

(3) Calcium chloride solution was dropped into the co-mixture of calcium alginate and PEG1500 at a certain rate. It was left to stand for 8 hours to obtain a wet composite phase change material.

(4) The wet composite capsule was cleaned and dried to obtain the dry composite phase change material.

The prepared composite Shaped phase change material is white granular solid as shown in

Figure 1, with hard texture, which can be used as an asphalt additive, and its apparent density is 1.08g/cm

3-1.21g/cm

3.

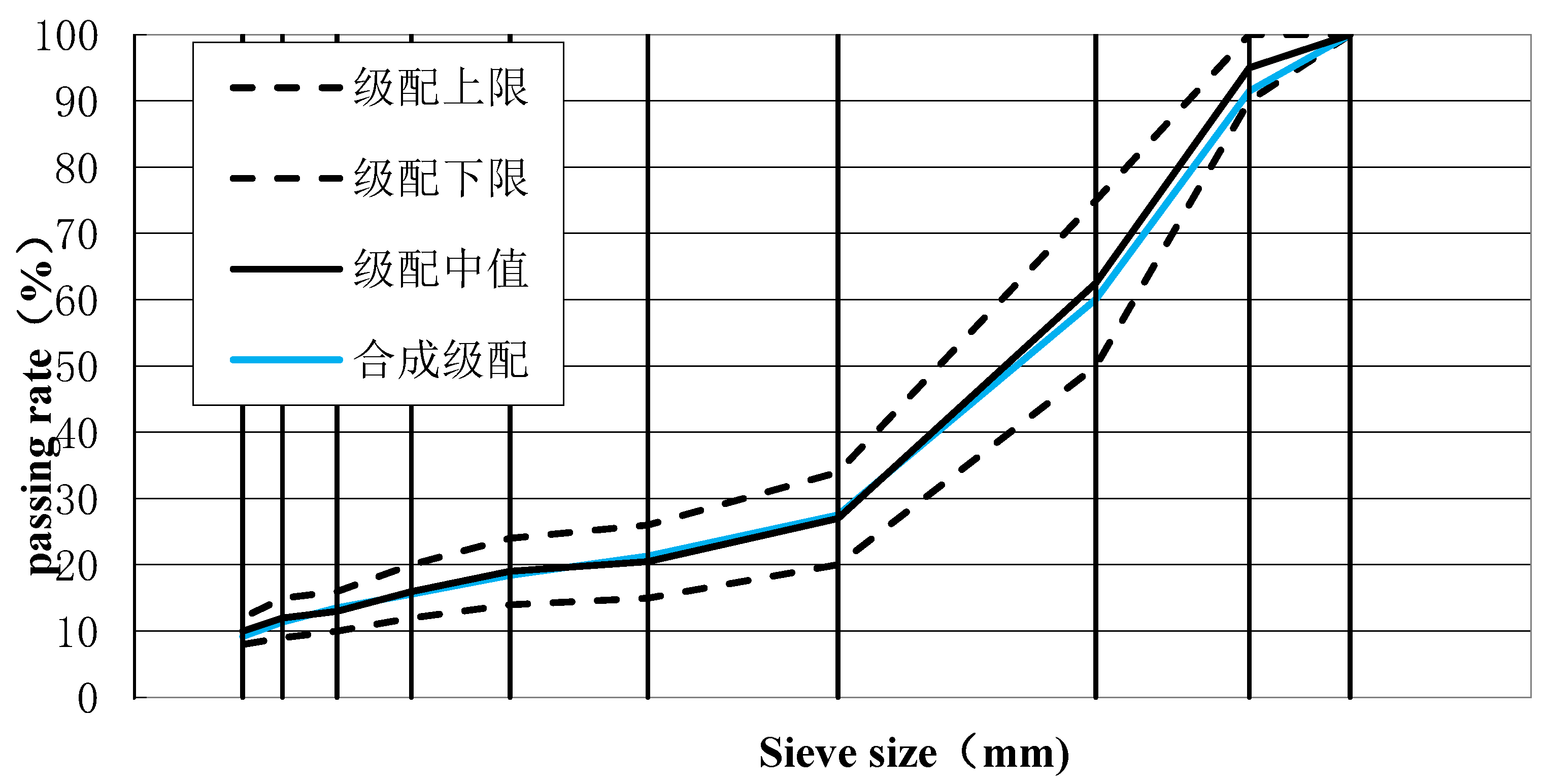

2.1.2. Mineral Gradation

Test with asphalt mixture type selection of asphalt pavement surface layer commonly used SMA-13. Marshall method for asphalt mixture ratio design, according to the SMA-13 range of mineral gradation requirements, mineral ratio debugging, mineral gradation and synthetic gradation table in

Table 1, synthetic gradation in

Figure 2.

2.1.3. The Optimum Asphalt Content SBS Modified Asphalt Was Selected

According to the American Society of Testing Materials (ASTM) standards and China's “Highway Asphalt Pavement Construction Technical Specification” (JTG F40-2004) requirements, in accordance with the “Highway Engineering Asphalt and Asphalt Mixture Testing Procedures” (JTG E20-2011), the asphalt was test, and the results are shown in

Table 2.

Volumetric method for asphalt mixture ratio design, double-sided compaction 50 times to make Marshall specimens, determination of VMA, VCAmix and other indicators, after the asphalt mixture ratio design, to determine the optimal oil-rock ratio of SMA-13 is 6.0%, the results of the ratio design is shown in

Table 3.

The data related to the design of the SMA Marshall test ratios and the corresponding technical requirements are shown in

Table 4.

According to the requirements, the road performance of SMA-13 mixes at the optimum oil/gravel ratio was examined and the results are shown in

Table 5.

As can be seen from

Table 5, its indicators are in line with the “highway asphalt pavement construction technical specifications” (JTG F40-2004), the performance of the designed SMA-13 mixture reaches the road technical requirements, can be used in the road. Follow-up research using the asphalt mixture to add phase change materials for temperature-related experimental studies.

2.2. Experimental Methods

2.2.1. Preparation of phase change asphalt mixture

In the asphalt mixture ratio design to determine the composition of the mixture on the basis of the preparation of phase change asphalt mixture. The development of the shape of the phase change material as an external dopant, according to a certain asphalt mass ratio and mineral powder mixed directly into the asphalt mixture. In order to analyze the influence of the amount of phase change material on the cooling effect, the ratio of admixture to asphalt is used: 10%, 20%, 30% and 40% four mixing amounts. Since the asphalt dosage of SMA-13 asphalt mixture in this paper is 6.0%. Therefore, when the phase change material in the asphalt of 10%, 20%, 30% and 40% of the mass ratio, its asphalt mixture in the dosage of 0.6%, 1.2%, 1.8% and 2.4%, respectively. The process of phase change asphalt mixture preparation is as follows:

(1) Firstly, three kinds of mineral materials with particle size of 10-15mm, 5-10mm and 0-3mm are put into the drying oven at 180℃ and heated for more than 4 hours to dry the moisture completely. The asphalt will be heated in the oven at 165℃±5℃ to the flow state.

(2) According to the proportion determined by the ratio design of the three minerals and fibers added to the mixing pot dry mixing 90s, add the flowing asphalt and then mix for 90s, and finally mix the mineral powder and the shaped phase change material, together with the pot mixing for 90s.

(3) Marshall specimens were made using the percussion method. The specimens were compacted 50 times on both sides of the standard compactor.

(4) The specimens were maintained at room temperature for 2 days and then demolded.

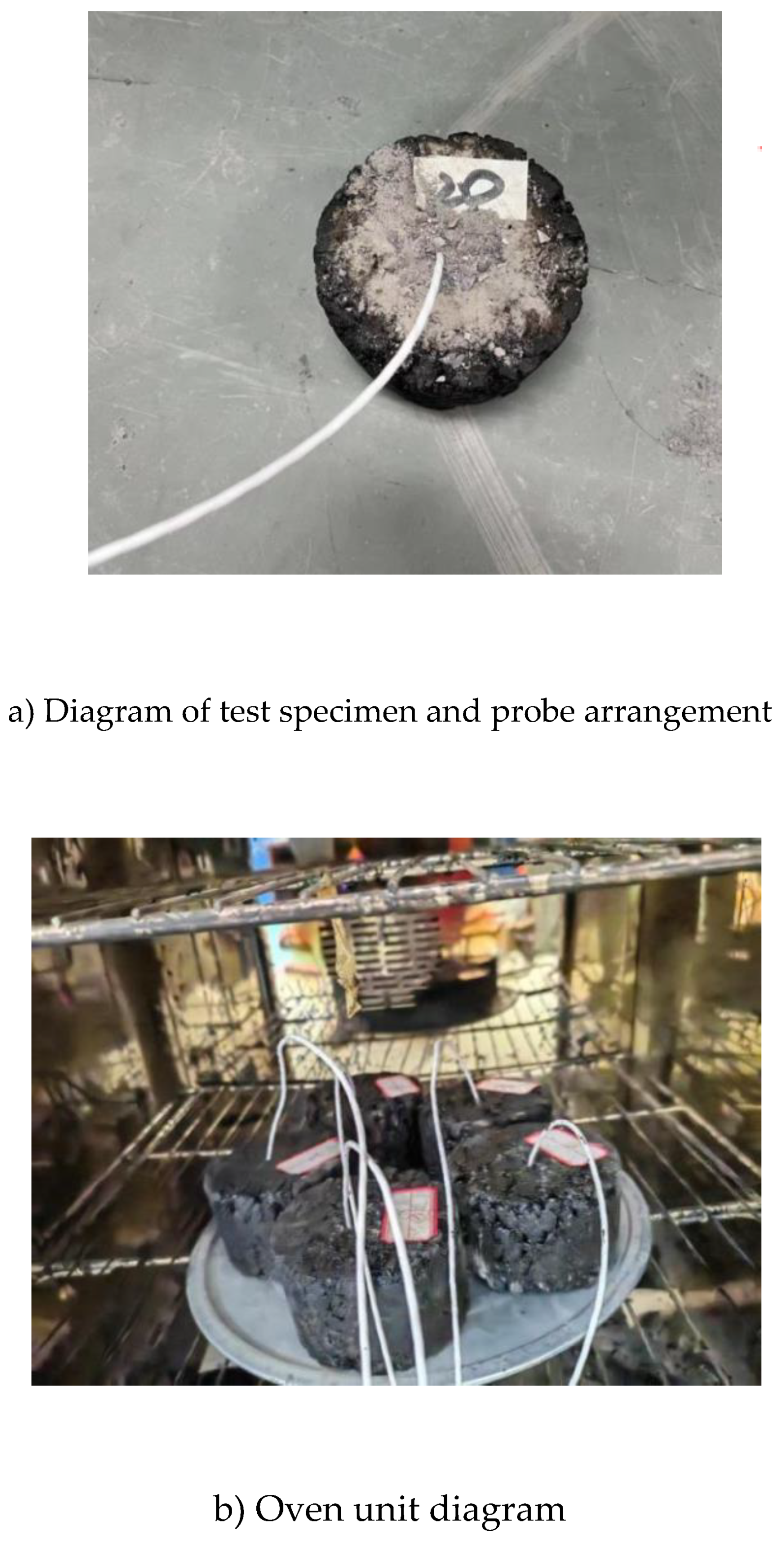

2.2.2. Experimental method of indoor temperature adjustment effect of phase change asphalt mixture

A standard Marshall specimen of asphalt mixture was molded by the compaction method, with a diameter of 101.6 mm and a height of 63.5 mm. In order to accurately measure the temperature change of the asphalt mixture, a temperature sensor was used to test the temperature. The temperature detection point was set at the center of the specimen. The test method is shown in

Figure 3.

(1) In the upper surface of the specimen at the center of the circle of vertical drilling, the depth of about 4.5cm, the length of 2.5cm temperature sensor probe into the drilled holes, backfill compaction with mineral powder, the installation schematic diagram as shown in

Figure 3a).

(2) Put the mixture specimen buried with the temperature sensor into the oven, use the oven to warm it up, and use the temperature recorder connected with the temperature sensor to record the temperature change inside each mixture specimen. The test specimen and the test setup are shown in

Figure 3.

(3) After the temperature of the specimen is stabilized, it is removed from the oven and placed in the room to cool down, and the temperature is recorded.

2.2.3. Simulation Method of Indoor Temperature Regulation Effect of Phase Change Asphalt Mixtures

This paper uses Comsol Multiphisics 6.0 software heat transfer module for transient studies. First of all, the standard Marshall specimen size to establish a geometric model, the model for the radius of 50.8mm, 63.5mm high cylinder, coordinates (0, 0, 0). Then the material parameters are imported and the basic material properties are shown in

Table 6 The density is taken from the density of the Marshall specimen measured in the actual test (

Table 6).

The phase change material module is added to this model.

In practice, PCM is uniformly mixed in the asphalt mixture, and PCM can be regarded as a part of mineral powder. However, in Comsol software, when adding PCM, it will be defaulted that the whole specimen is completely composed of PCM, which is obviously inconsistent with the actual situation, therefore, the latent heat of PCM is converted in this study. The conversion formula is (2-1):

is the converted latent heat of phase change of PCM from phase 1 to phase 2(KJ/Kg);

is the latent heat of phase transition from phase 1 to phase 2 per kilogram of PCM(KJ/Kg);x is the mass of PCM added in the experiment (g)。In this study, phase 1 is the solid phase and phase 2 is the liquid phase. For consistency with the actual experiments, the same proportions of 10%, 20%, 30% and 40% of asphalt mass i.e. 0.6%, 1.2%, 1.8% and 2.4% of asphalt concrete were used on Comsol. The latent heat of phase change for different PCM proportions is shown in

Table 7 below.

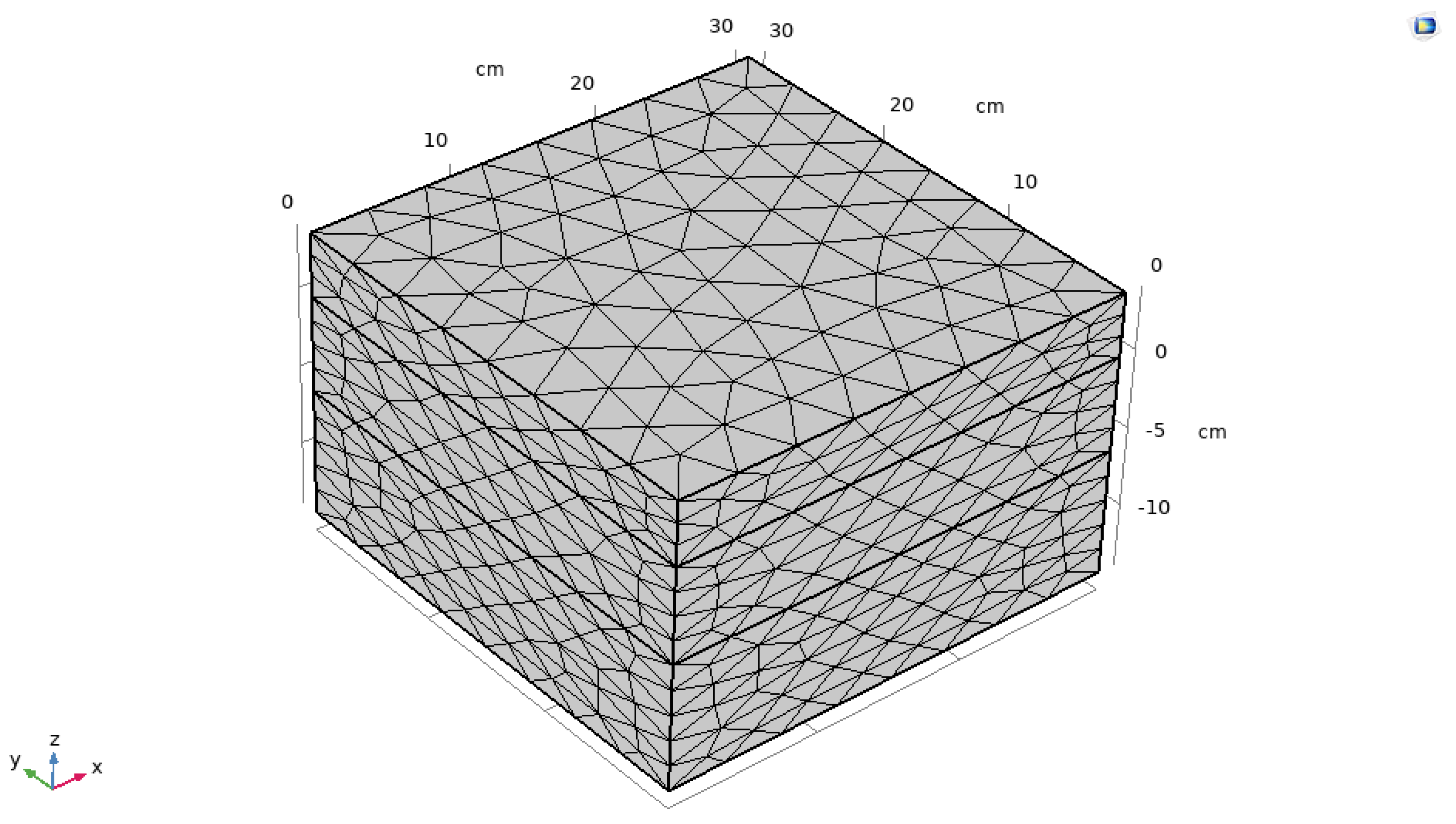

2.2.4. Establishment of Outdoor Temperature Field Model of Phase Change Asphalt Pavement

In order to more realistically simulate the working performance of PCM in practice, this paper chooses to establish a three-layer asphalt pavement structure as the object of study, and its pavement structure consists of: 4cm SMA-13 as the upper layer, 6cm AC-20 medium-grained asphalt concrete as the middle surface layer, 8cm AC-25 coarse-grained asphalt concrete as the lower layer, and the performance of each layer of the material is shown in

Table 8.

After determining the material parameters of each layer, a model with dimensions of 30cm x 30cm x 18cm was created in Comsol. For the convenience of carrying out the study, the simulations were carried out assuming that each asphalt surface layer material is homogeneous and each isotropic. The physical parameters such as density, thermal conductivity, constant pressure heat capacity of the material do not change with the change of temperature, in addition, according to the meteorological data, the heat flux of the sun to the ground is selected to be 800 w/m2. at the same time, the ambient radiant temperature is set to be 35 ℃, and the road test specimens are insulated at the bottom and the side of the road test specimens are insulated to set up, so that it can simulate as much as possible the most unfavorable situation of the test specimens under the sunny and hot weather in summer.

The object of this study is the variation of asphalt pavement with external temperature in three layers, because asphalt pavement transfers heat downward from the pavement during the heat transfer process, it is necessary to control the mesh size manually along the thickness direction to a smaller value when performing the meshing to improve the accuracy of calculating the temperature at different thicknesses. By using a finer mesh, the calculation of the temperature field can be improved to verify the accuracy. For the finite element calculations of the specimen, triangular cells were used for discretization. The maximum cell side length is about 0.01m. The finite element schematic is shown in

Figure 4.

3. Experimental Results and Discussion

3.1. Experimental Results and Simulation Results of Phase Change Asphalt Mixtures Indoor Thermoregulation Performance

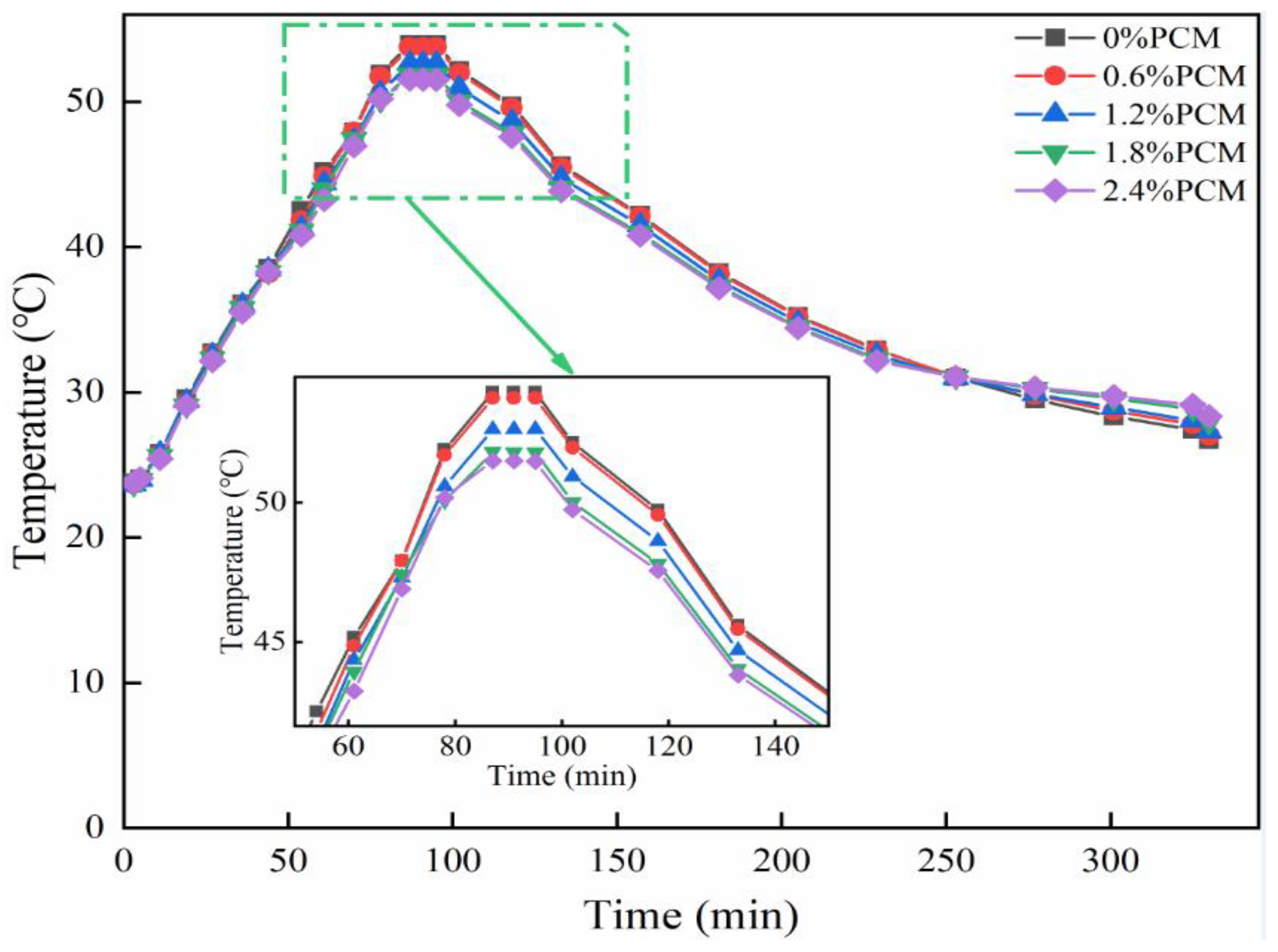

3.1.1. Experimental Results and Analysis of Phase Change Asphalt Mixture Temperature Regulation Performance

In order to simulate the actual situation of asphalt pavement at high temperatures in summer, this study in the test process will be put into the test pieces of each mixture together in the 23 ℃ oven so that the temperature is stable, and then the use of the oven on the mixture specimens 23 ℃ to 60 ℃ warming treatment, simulating the process of asphalt pavement warming. When the sample temperature is stabilized, the warming is stopped; after the warming is finished, the specimen is removed from the oven and cooled naturally in the room at 23℃ to simulate the cooling process of the road surface. The temperature change of the mix specimen is recorded by the temperature recorder during the temperature rise and fall process, and the temperature rise and fall process of 330min is a temperature cycle, and the temperature collection time interval is 1min.

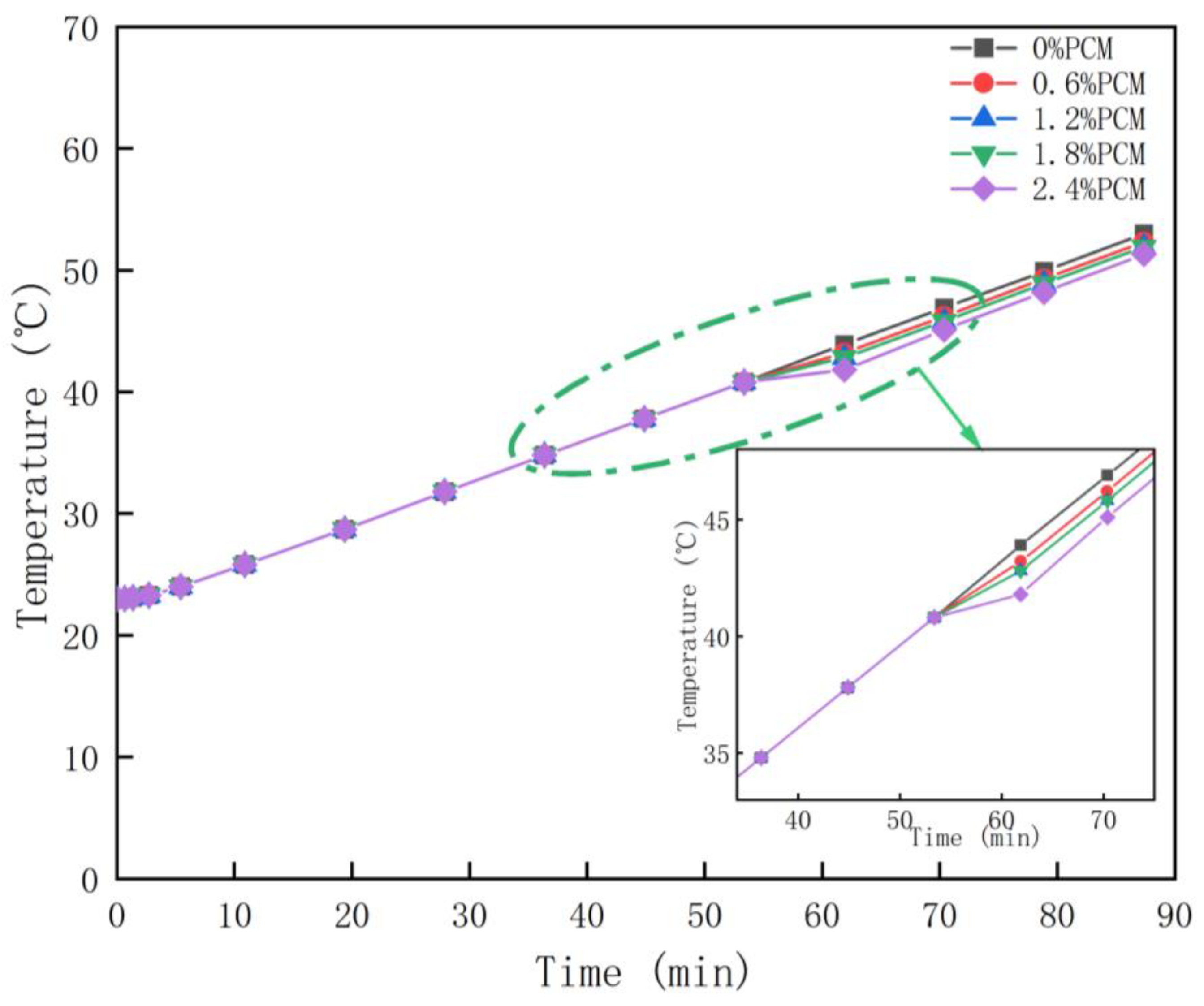

Figure 5 shows the data obtained from a temperature cycle test. As can be seen from the figure, the peak internal temperature of the specimen is about 86min, at which time the specimen without phase change material reached the maximum temperature of 52.9℃, the maximum temperature of the specimen with 0.6% of PCM content is 52.7℃, the temperature of the specimen with 1.2% of PCM content is 51.6℃, and the maximum temperature of the asphalt pavement with the content of 1.8% and 2.4% are 50.8℃ and 50.5℃ respectively. Therefore, PCM doping can reduce the temperature peaks. As the mass ratio of phase change material increases, the temperature peak decreases. The temperature increase rate is shown in

Table 9, the temperature increase rate of the specimens with 0.6% phase change material doping is not much different from the specimens without phase change material doping, whereas in the specimens doped with 1.2% and above mass ratio, the temperature increase rate decreases with the increase of mass ratio. This indicates that the doping of phase change materials not only plays a role in weakening the peak temperature, but also reduces the rate of temperature rise.

It can be seen that when the content of phase change material is small, the content is less than 1.8%, the temperature regulation effect is not obvious. When the phase change material doping reaches a certain level, the peak of high temperature decreases, and with the increase of content, the peak decreases more. This indicates that the phase change material plays a role in the asphalt and absorbs heat. As the content increases, the rate of temperature increase slows down, indicating that the phase change material also slows down the heating and weakens the temperature stress. However, during the actual test, the test can be inaccurate because of various factors, such as the position of the specimen in the oven and the uniformity of the phase change material within the mix specimen. It was shown in [

26] that when PPGC-PCM was added at 7.5%, the maximum temperature of the pavement in summer was reduced by 8.9°C compared with ordinary asphalt pavement, and the warming time was extended by 60 min.

In this experiment, the heating rates of different specimens are different before the temperature reaches the working temperature of PCM, so further temperature field simulation is needed to better investigate the thermoregulation effect of PCM. In addition, in this experiment, the higher content of PEG1500 means the higher content of calcium alginate as the carrier of phase change material. And calcium alginate may affect the warming of the specimen, thus causing the temperature change near the probe to become faster with the increase of the content of phase change composite, so this study needs to take calcium alginate as one of the influencing factors. However, according to

Figure 5, the temperature changes were approximately the same when the temperature did not reach the PEG operating temperature. Therefore, it can be shown that the effect of calcium alginate on the temperature of the specimen is not significant when it is used as a carrier for PCM, and thus the effect of calcium alginate in the subsequent test can be ignored. However, when applying the composite phase change material to asphalt pavement, it is necessary to consider its strength and other properties, so as to ensure that the durability of the pavement will not be damaged due to the incorporation of the phase change material.

3.1.2. Simulation Results and Analysis of Phase Change Asphalt Mixture Temperature Regulation Performance

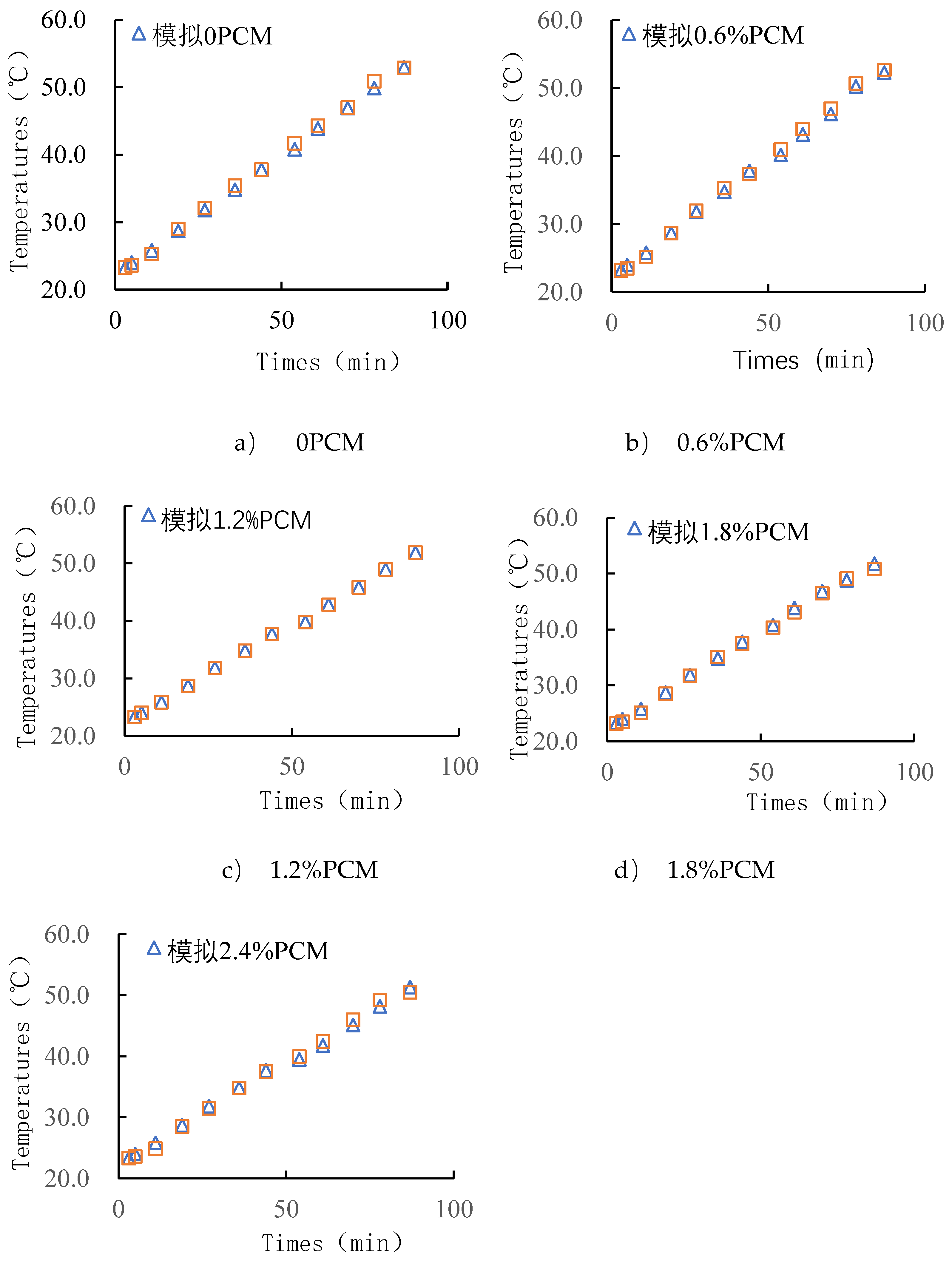

According to the data of phase change temperature interval and latent heat of phase change and other data for transient calculations, the obtained probe temperature is shown in

Figure 6. From

Figure 6, it can be seen that the warming trend of specimens containing different proportions of PCM is basically the same. Before the specimens reached 41°C, i.e., the period from the beginning of heating to 45 minutes, all groups had the same rate of warming. However, in the 2.4% PCM group, it can be clearly seen that the rate of warming starts to decrease slowly from 41°C onwards. In the 0.6% and 1.2% specimens, the decrease in the rate of warming was not significant. In the test group containing 1.8% PCM, there was a slight decrease in the rate of warming. At a specimen temperature of 43°C, the warming rate slowly returned to its original level until the end of the 85-minute warming period. At the end of the warming period, the final temperatures of the different groups were not very different, although they were different. The specimens without phase change material had a final temperature of 52.0°C, while the specimens with 2.4% PCM had a final temperature of 50.2°C. The final temperature of the specimens with 2.4% PCM was 50.2°C.

Comparing the results of the actual test (

Figure 5) with those of the simulation test (

Figure 6), the results of the two are more consistent, and the pattern of the probe temperature change with the ambient temperature is basically the same for both tests. PCM does play a role in absorbing heat and then slowing down the warming, and this effect becomes more and more obvious with the increase of the doping amount. However, in the final temperature, the cooling effect is not obvious, and there is only a 1.8°C difference between the specimen without phase change material and the specimen with 2.4% phase change material. Compared with other temperature reduction measures, PEG1500 as phase change material in SMA-13 asphalt mixture specimens was not effective for indoor high temperature conditioning. It is noteworthy that in the 2.4% PCM group, the warming rate returned to its original level at 42°C, which indicates that the PCM stopped cooling at that point. However, the phase transition temperature interval of PEG1500 is 41℃-46℃. Theoretically, the rate of heating should return to the level before the phase transition at 46℃. Therefore, it can be inferred that all the PCMs in the specimen have completed the phase change heat absorption process when the temperature reaches 42℃. The reason could be the low content of phase change material. Therefore, on the basis of not affecting the road performance, the doping amount of the composite phase change material can be increased so as to realize a better cooling effect.

3.1.3. Comparative Analysis of Experimental Results and Simulation Results of Phase Change Asphalt Mixture Temperature Regulation Performance

Figure 7 for the 87min test results and Comsol probe temperature numerical calculation of different time temperature control table, from which can be seen that the finite element calculation results and the actual test results of the temperature difference of the maximum value of 1.4 ℃, the temperature difference of 1 ℃ or less accounted for 93.3% of the total number of finite element calculations for accurate results. Comparison of the results of this test and simulation can also prove that the subsequent simulation results for the actual working conditions have a high degree of confidence.

3.2. Simulation Results and Analysis of Outdoor Temperature Field of Phase Change Asphalt Pavement

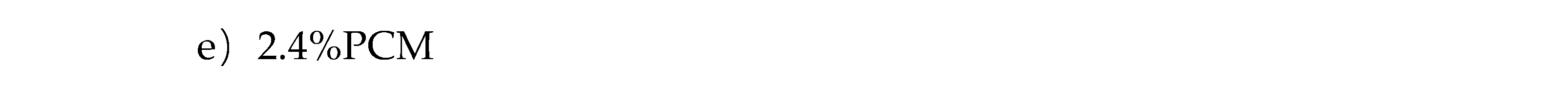

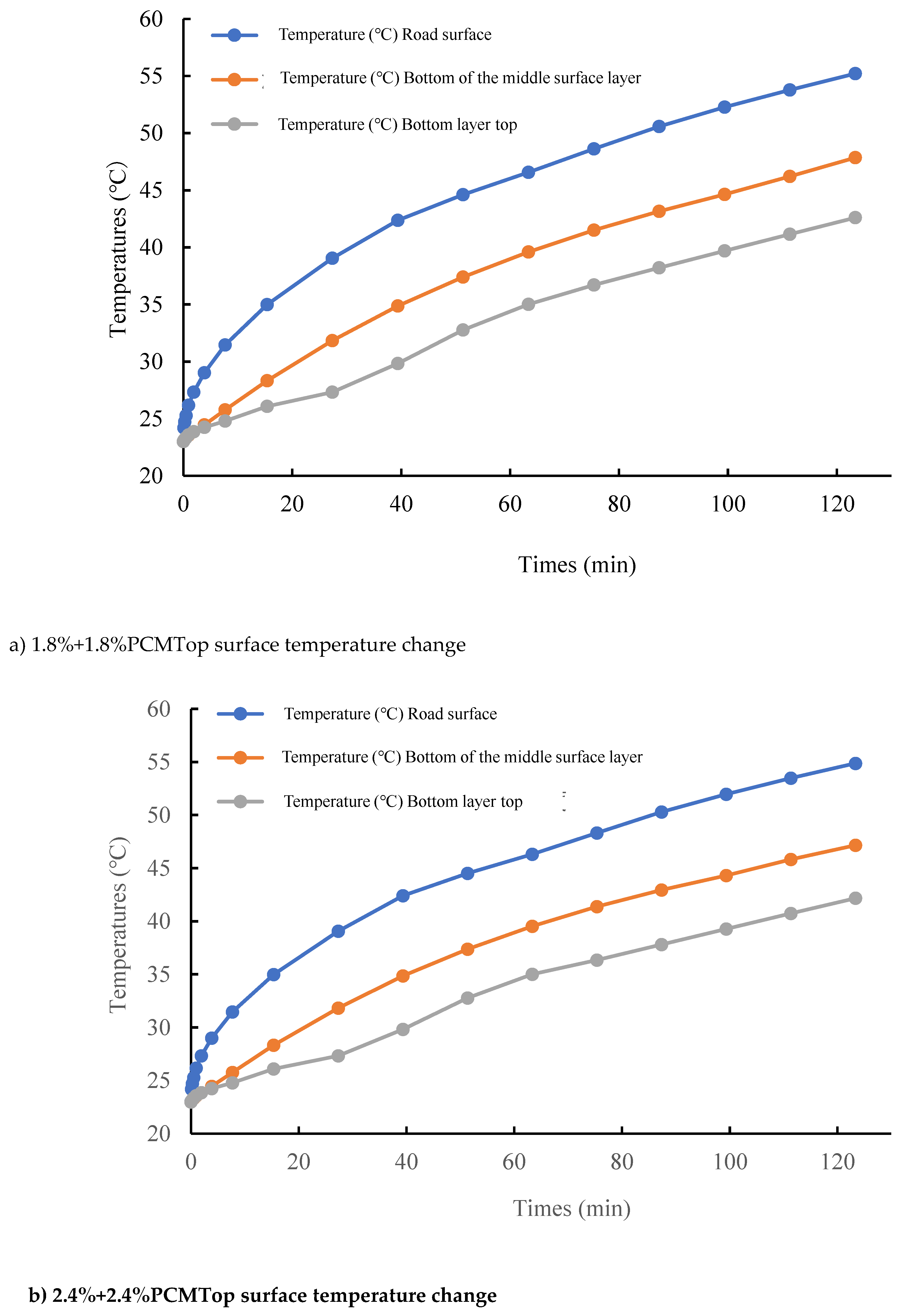

Using Comsol Multiphisics 6.0 software heat transfer module to establish the transient study finite element model, the surface layers without adding phase change material and different phase change material doping of the surface layers were compared and analyzed, and the temperature of the top surface of each layer as the main object of concern, the reason is that the heat is transmitted vertically downward on the different layers, and the top surface is the first to receive the heat and has the highest temperature, which can better understand the most unfavorable location of each layer. The simulation results are shown in

Figure 8.

When no phase change material is added, the road surface temperature can reach up to 56°C. At this point, the dynamic stability of the SBS asphalt starts to plummet and aggravates the aging, which leads to a decrease in the durability of the asphalt pavement. Not only does the top layer lose durability, but the middle layer is also within the range of the asphalt's sudden drop in dynamic stability. Therefore, it is necessary to add phase change materials to temper the upper and middle surface layers, while the third layer has a lower temperature and is not considered for tempering for the time being.

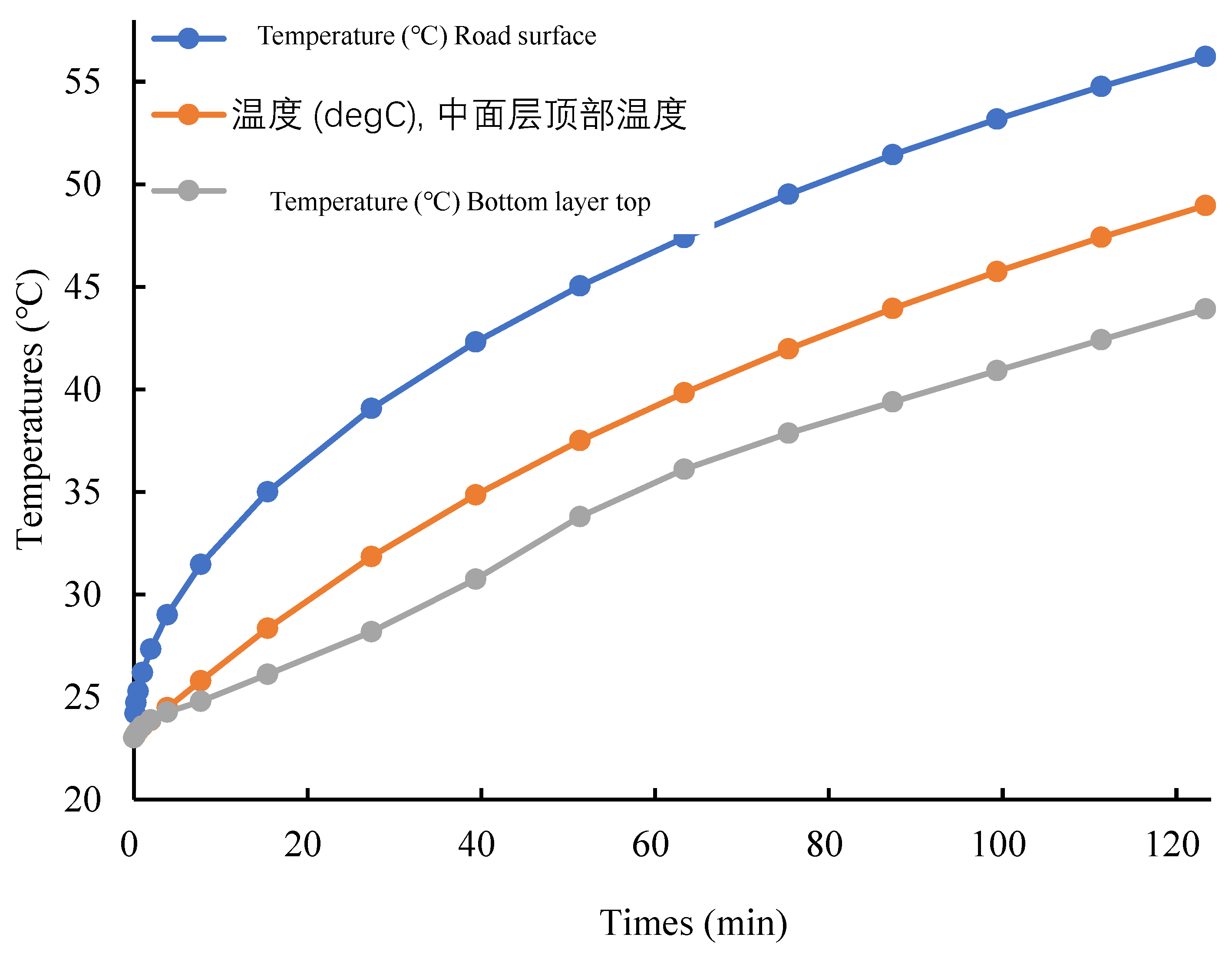

According to the results of the indoor high temperature test, the specimens with the content of PCM of 1.8% or less do not have a significant thermoregulation effect. Therefore, in the outdoor simulation, this study chooses to add PCM with 1.8% or 2.4% content in different layers to explore the appropriate dosage for optimal thermoregulation effect. The surface temperatures of asphalt pavements after adding 1.8% and 2.4% phase change materials to the upper and middle layers are shown in

Figure 9.

According to

Figure 9, it can be seen that after adding 1.8% PCM to the top layer, the maximum temperature is 55.2°C at 123 minutes, which is about 1°C lower compared with the specimen without phase change material. However, it is still in the range of sudden drop of dynamic stability, so the temperature regulation effect of asphalt pavement with 1.8% PCM doping is not ideal. Therefore, the phase change material content of the top layer was increased to 2.4% and the simulated values are shown in

Figure 9b). At 123 min, the maximum temperature of 54.8°C is outside the range of sudden drop in dynamic stability, so the PCM at this doping level has a certain thermoregulatory effect on phase change asphalt pavement.

The final temperature of the middle surface layer was about 1°C lower than that without the phase change material after the phase change material was added, and 1.8°C lower at 2.4% doping. It can be seen that the phase change material plays the role of temperature regulation, reduces the maximum temperature of the pavement and slows down the rate of warming, and the temperature regulation effect is better when the dosage is 2.4%.

4. Conclusions and Outlook

Asphalt mixture as a temperature-sensitive materials, its performance, service life and pavement disease are closely related to temperature conditions, this paper through the material selection and mix design, indoor testing and numerical analysis to carry out the composite phase change material cooling mechanism and cooling characteristics of the study, the following main conclusions.

(1) Based on the asphalt pavement materials and use requirements, based on the phase change characteristics of phase change materials, PEG1500 as the core material, calcium alginate as the wall material to prepare a microencapsulated composite phase change materials used in asphalt mixtures. The results show that the highest temperature of the specimen with 0.6% PCM content is 52.7℃, and the temperature of the specimen with 1.2% PCM content is 51.6℃. While the maximum temperatures of asphalt pavements with 1.8% and 2.4% contents were 50.8°C and 50.5°C, respectively, and the increase in PCM dosing helped to reduce the temperature peaks. In addition, the blending of PCM can also reduce the heating rate of the material, which is beneficial to asphalt mixtures in the summer high temperature season. the higher the content of PCM, the better the cooling effect.

(2) The composite phase change material is applied in asphalt pavement as a thermoregulation material, and when the doping amount is 2.4%, its cooling effect can reach 1.5℃, and at the same time, it can effectively reduce the warming rate of asphalt pavement.

(3) Through the establishment of indoor Marshall specimen warming test model in Comsol, it can be seen that the test results are almost the same as the simulation results, so it is feasible to simulate the subsequent asphalt pavement test on Comsol, and it can effectively save resources and costs.

(4) By establishing the outdoor asphalt pavement temperature field simulation in comsol, it is known. Without the addition of phase change materials, the road surface temperature will reach 56℃, SBS modified asphalt temperature is in the dynamic stability of the sudden drop range, at this time will exacerbate the aging of asphalt pavement. After adding 1.8% phase change material in the upper layer and the middle surface layer, the temperature is still in the range of dynamic stability drop; after adding 2.4% composite phase change material in the upper layer and the middle surface layer, the pavement temperature is reduced to 54℃, and slowed down the rate of warming.

Overall, the incorporation of phase change materials can be effective, but the cooling effect of PCM is not ideal at high temperatures for reasons that may be related to the errors generated by the phase change materials, the selection of wall materials, and the effects of temperature in the experiments. Therefore, in the future, it is recommended to carry out interdisciplinary cooperation among aerospace, chemistry, and architecture to expand the promotion of the application range of PCM, with the aim of obtaining a PCM with better thermoregulation effect.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.Y. and X.C.; methodology Y.Q.; data curation, M.G.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.Y.; writing—review and editing, S.S.; visualization, X.K.; supervision, F.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by Gansu Provincial Science and Technology Plan (23YFGA0019,23JRRA1375) and Lanzhou Youth Science and Technology Talent Inno-vation Project(2023-QN-102), National Natural Science Foundation of China (52478429, 52078018), the National Key R&D Program of China (2022YFE0137300).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Guo, M.; Zhang, R.; Du, X.; Liu, P. A State-of-the-Art Review on the Functionality of Ultra-Thin Overlays Towards a Future Low Carbon Road Maintenance. Engineering 2023, 32, 82–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, M.; Xie, X.; Du, X.; Sun, C.; Sun, Y. Study on the multi-phase aging mechanism of crumb rubber modified asphalt binder. Int. J. Pavement Eng. 2025, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, M.; Liang, M.; Jiao, Y.; Zhao, W.; Duan, Y.; Liu, H. A review of phase change materials in asphalt binder and asphalt mixture. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, M.; Liang, M.; Jiao, Y.; Zhao, W.; Duan, Y.; Liu, H. A review of phase change materials in asphalt binder and asphalt mixture. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen Y, Wang H, You Z, et al. Application of phase change material in asphalt mixture–A review[J]. Construction and Building Materials, 2020, 263, 120219.

- Montoya, M.A.; Rahbar-Rastegar, R.; Haddock, J.E. Incorporating phase change materials in asphalt pavements to melt snow and ice. Int. J. Pavement Eng. 2022, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirzanamadi, R.; Johansson, P.; Grammatikos, S.A. Thermal properties of asphalt concrete: A numerical and experimental study. Constr. Build. Mater. 2018, 158, 774–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, M.; Wang, S.; Deng, J.; Gao, Z.; Liu, Z. Study on the Cooling Effect of Asphalt Pavement Blended with Composite Phase Change Materials. Materials 2022, 15, 3208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Zhang, X.; Zhou, X.; Liu, B.; Wang, X.; Lin, X. Research and Exploration of Phase Change Materials on Solar Pavement and Asphalt Pavement: A review. J. Energy Storage 2021, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Wan, L.; Lin, J. Effect of Phase-Change Materials on Thermal and Mechanical Properties of Asphalt Mixtures. J. Test. Evaluation 2012, 40, 746–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, W.; Liu, Z.; Yang, Y.; Zhou, C.; Lei, J. Preparation and characterizations of asphalt/lauric acid blends phase change materials for potential building materials. Constr. Build. Mater. 2017, 152, 568–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phan T M, Park D W, Le T H M. Improvement on rheological property of asphalt binder using synthesized micro-encapsulation phase change material[J]. Construction and Building Materials, 2021, 287: 123021.

- Zhang, D.; Chen, M.; Wu, S.; Riara, M.; Wan, J.; Li, Y. Thermal and rheological performance of asphalt binders modified with expanded graphite/polyethylene glycol composite phase change material (EP-CPCM). Constr. Build. Mater. 2019, 194, 83–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Ma, B.; Li, S.; Si, W.; Wei, K.; Zhang, H.; Zhou, X.; Fang, Y.; Kang, X.; Shi, W. Review on application of phase change materials in asphalt pavement. J. Traffic Transp. Eng. (English Ed. 2023, 10, 185–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarier, N.; Onder, E. Organic phase change materials and their textile applications: An overview. Thermochim. Acta 2012, 540, 7–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kemp D, Ebert D, Danielson R, et al. Use of otoacousticemission phase change to evaluate countermeasures for spaceflight-associated neuro-ocular syndrome[R]. 2020.

- Kenisarin, M.; Mahkamov, K. Solar energy storage using phase change materials☆. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2007, 11, 1913–1965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asgharian, H.; Baniasadi, E. A review on modeling and simulation of solar energy storage systems based on phase change materials. J. Energy Storage 2019, 21, 186–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souayfane, F.; Fardoun, F.; Biwole, P.-H. Phase change materials (PCM) for cooling applications in buildings: A review. Energy Build. 2016, 129, 396–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tseng, Y.-H.; Fang, M.-H.; Tsai, P.-S.; Yang, Y.-M. Preparation of microencapsulated phase-change materials (MCPCMs) by means of interfacial polycondensation. J. Microencapsul. 2005, 22, 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, J.-S.; Kwon, A.; Cho, C.-G. Microencapsulation of octadecane as a phase-change material by interfacial polymerization in an emulsion system. Colloid Polym. Sci. 2002, 280, 260–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Chen, M.; Wu, S.; Riara, M.; Wan, J.; Li, Y. Thermal and rheological performance of asphalt binders modified with expanded graphite/polyethylene glycol composite phase change material (EP-CPCM). Constr. Build. Mater. 2019, 194, 83–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Y.; Shi, X.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, J. Numerical modelling of rutting performance of asphalt concrete pavement containing phase change material. Eng. Comput. 2021, 39, 1167–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, K.; Wang, X.; Ma, B.; Shi, W.; Duan, S.; Liu, F. Study on rheological properties and phase-change temperature control of asphalt modified by polyurethane solid–solid phase change material. Sol. Energy 2019, 194, 893–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kakar, M.R.; Refaa, Z.; Worlitschek, J.; Stamatiou, A.; Partl, M.N.; Bueno, M. Effects of aging on asphalt binders modified with microencapsulated phase change material. Compos. Part B: Eng. 2019, 173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Jin, J.; Xiao, T.; Liu, M.; Liu, S.; Liu, R.; Pan, J.; Qian, G.; Liu, X. Study of temperature-adjustment asphalt mixtures based on silica-based composite phase change material and its simulation. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amini N, Hayati P. Effects of CuO nanoparticles as phase change material on chemical, thermal and mechanical properties of asphalt binder and mixture[J]. Construction and Building Materials, 2020, 251: 118996.

- Cheng, C.; Cheng, G.; Gong, F.; Fu, Y.; Qiao, J. Performance evaluation of asphalt mixture using polyethylene glycol polyacrylamide graft copolymer as solid–solid phase change materials. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, C.; Liu, J.; Gong, F.; Fu, Y.; Cheng, X.; Qiao, J. Performance and evaluation models for different structural types of asphalt mixture using shape-stabilized phase change material. Constr. Build. Mater. 2023, 383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).