Submitted:

28 July 2025

Posted:

29 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- History of Beclin-1 discovery at glance

- 2.

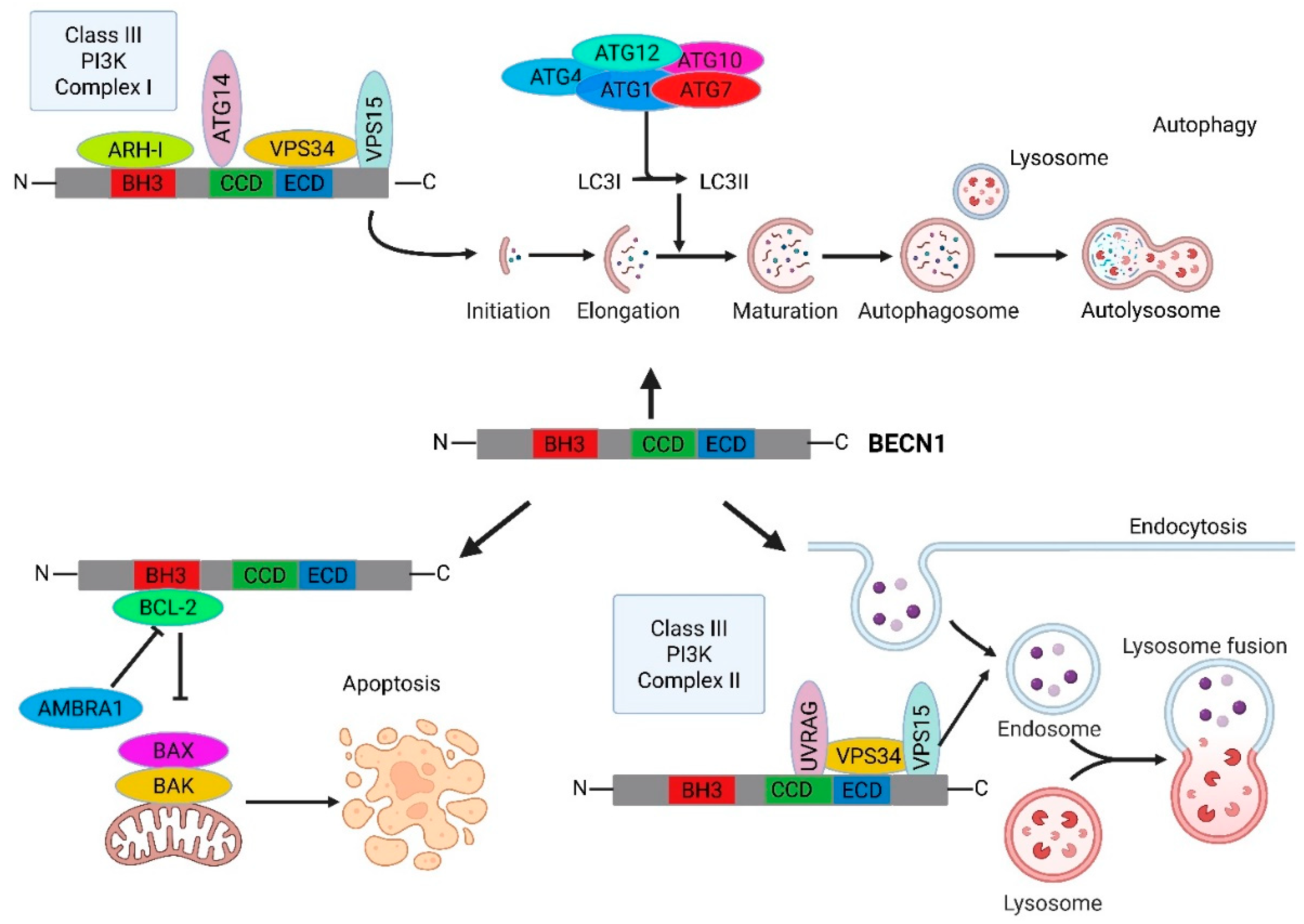

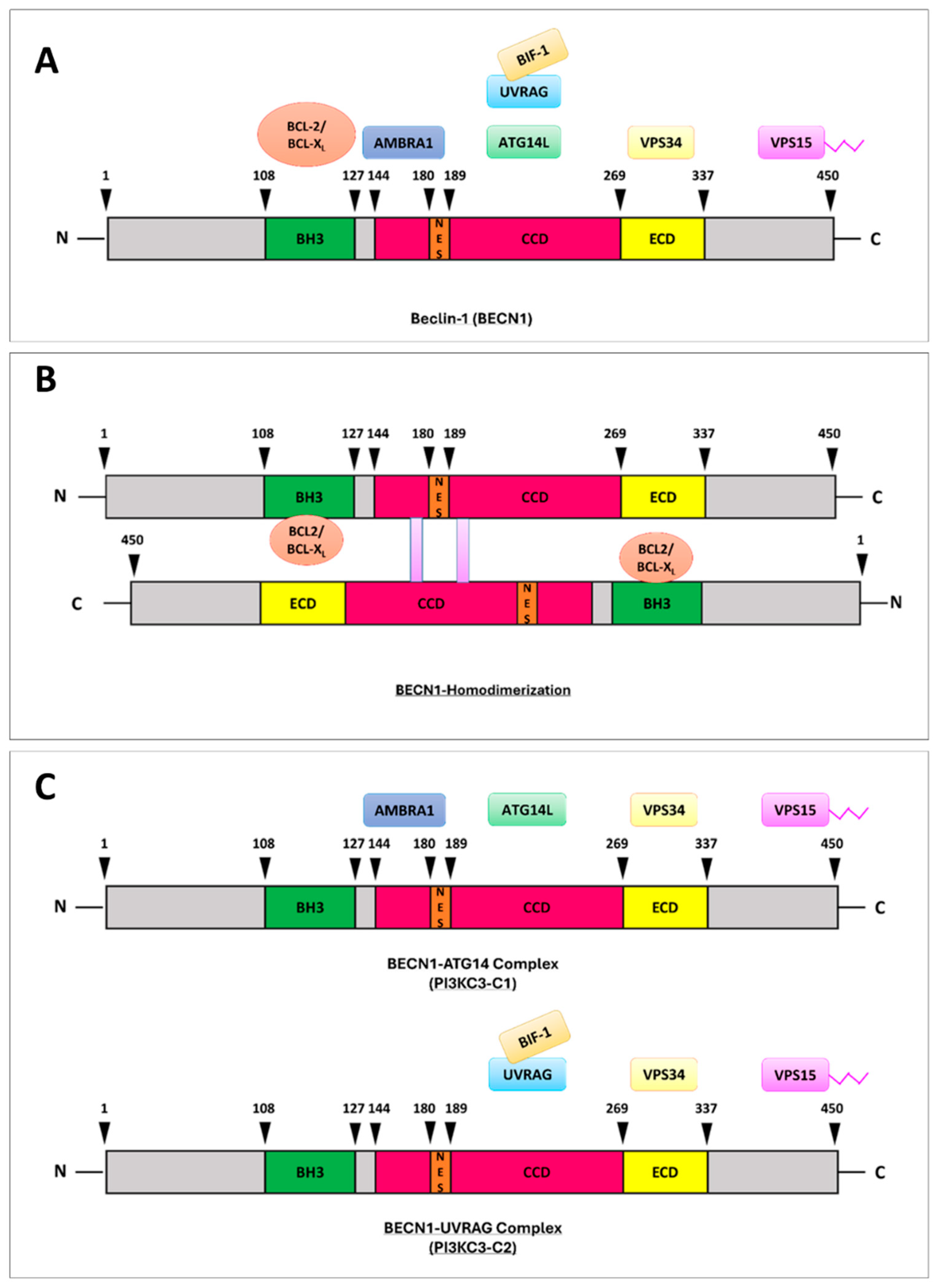

- Molecular Architecture and Interaction Landscape of BECLIN-1

2. Multilayered Regulation of Beclin-1 in Cancer

2.1. Transcriptional Regulation of BECN1

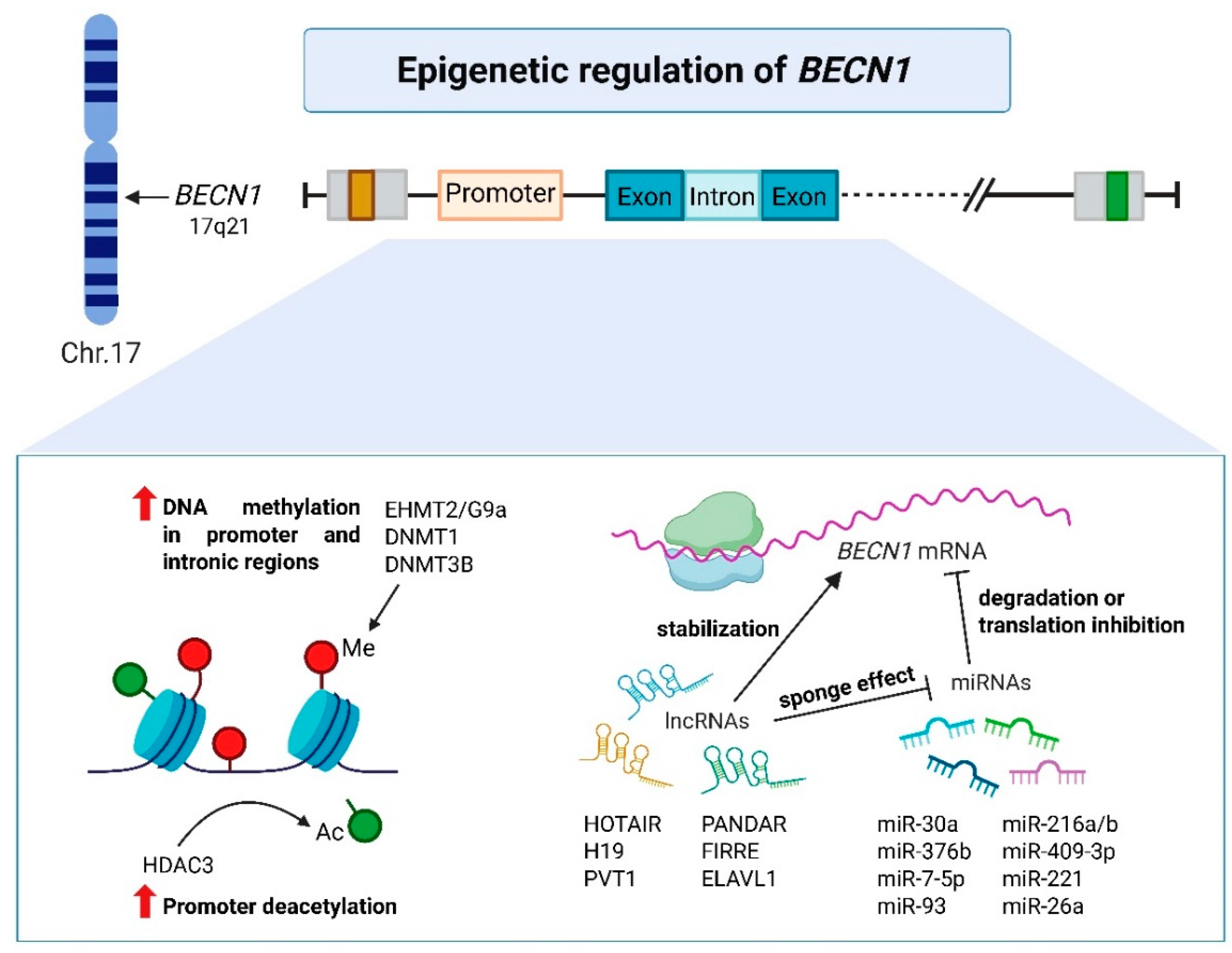

2.2. Epigenetic Modifiers of BECN1

2.3. Post-Transcriptional Control of BECN1 mRNA Translation in Cancer Cells

2.3.2. LncRNAs Targeting BECN1 and Their Impact on Cancer Biology

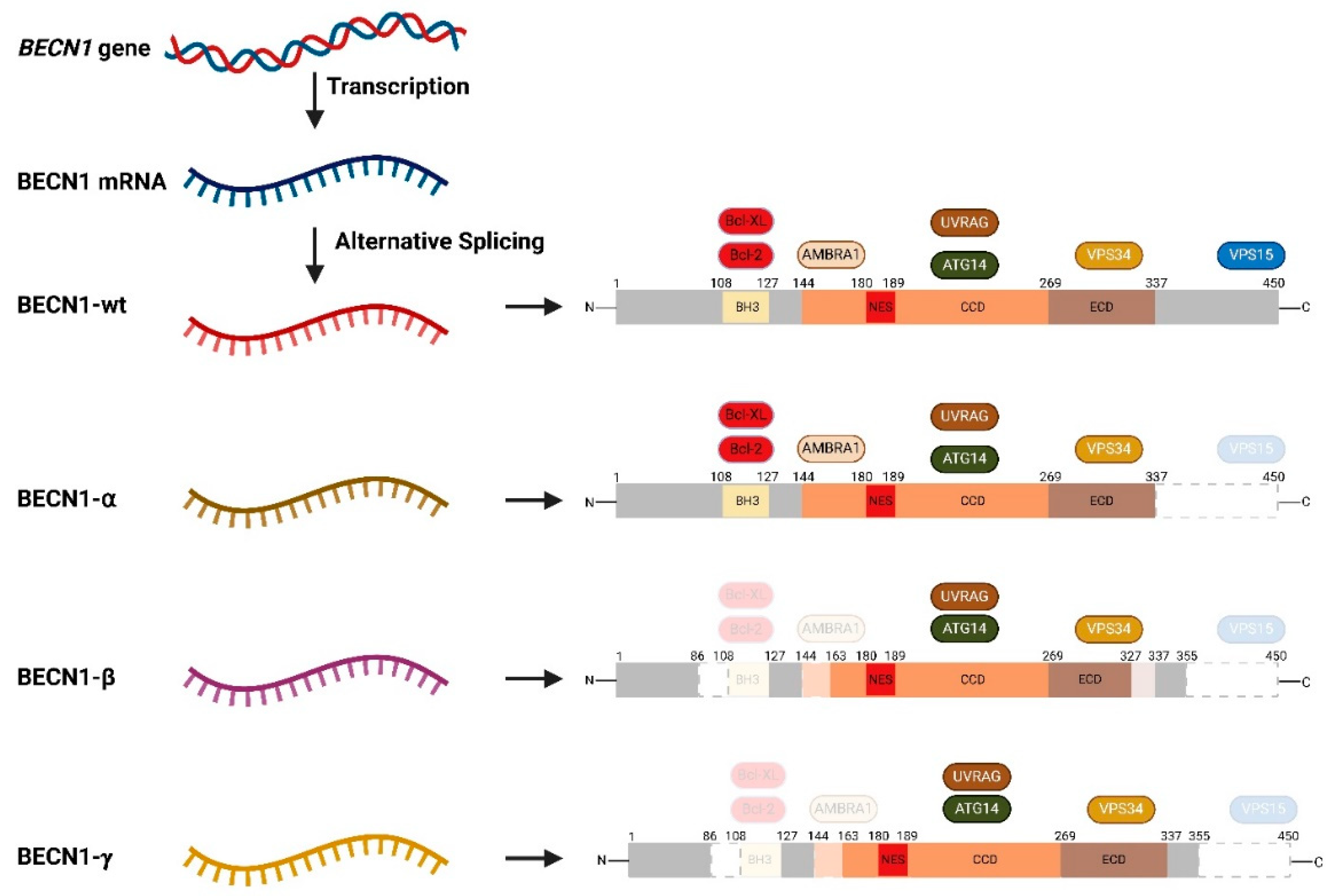

2.3.3. Alternative Splicing of BECN1

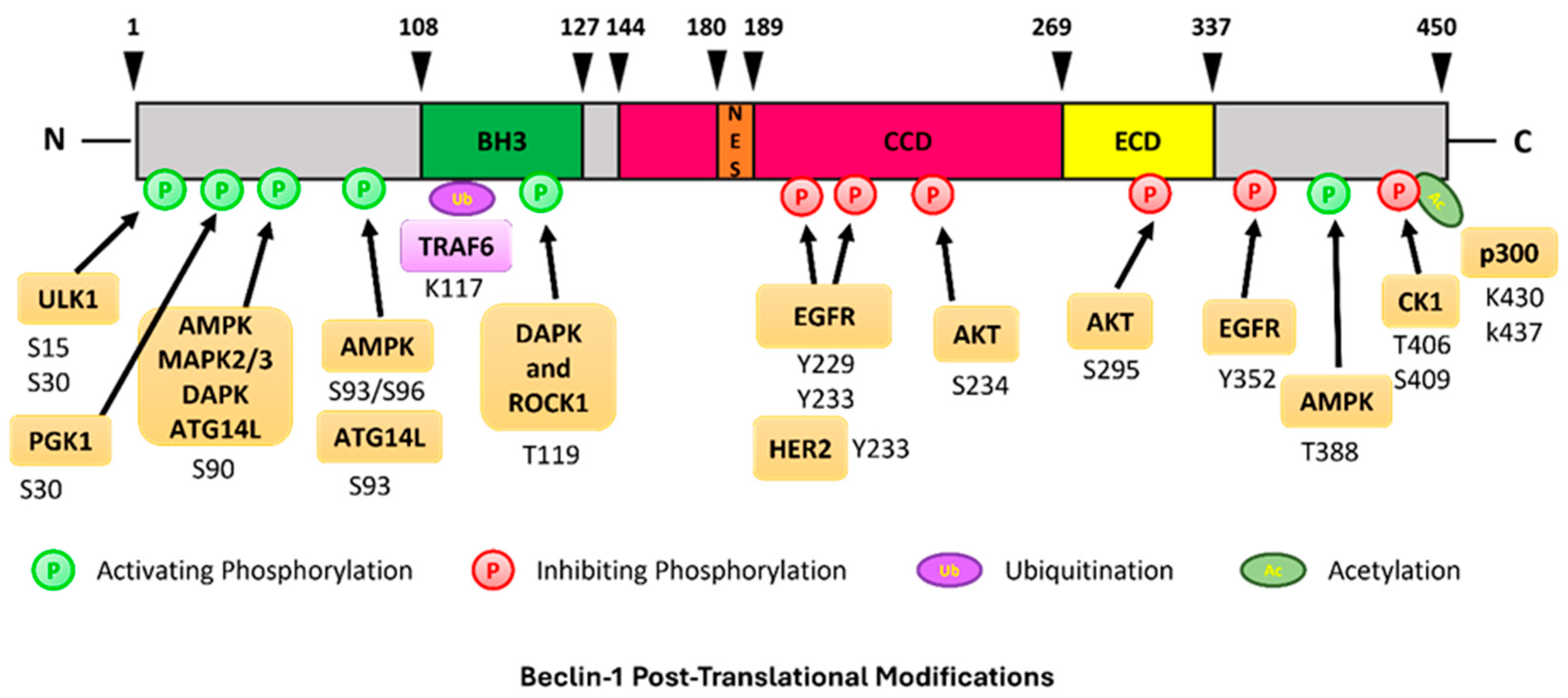

3. Post-Translational Modifications on BECN1

3.1. Ubiquination of BECN1

3.2. Acetylation

3.3. Phosphorylation

4. Functional Role of BECN1 in Cancers

4.1. Pivotal Link Between Autophagy and Apoptosis

4.2. BECLIN-1-Dependent Selective Autophagy

4.3. BECLIN-1 in Endocytotic Trafficking and Receptor Signaling in Cancer

4.4. BECLIN-1 Crosstalk with Other Pathways in Cancer

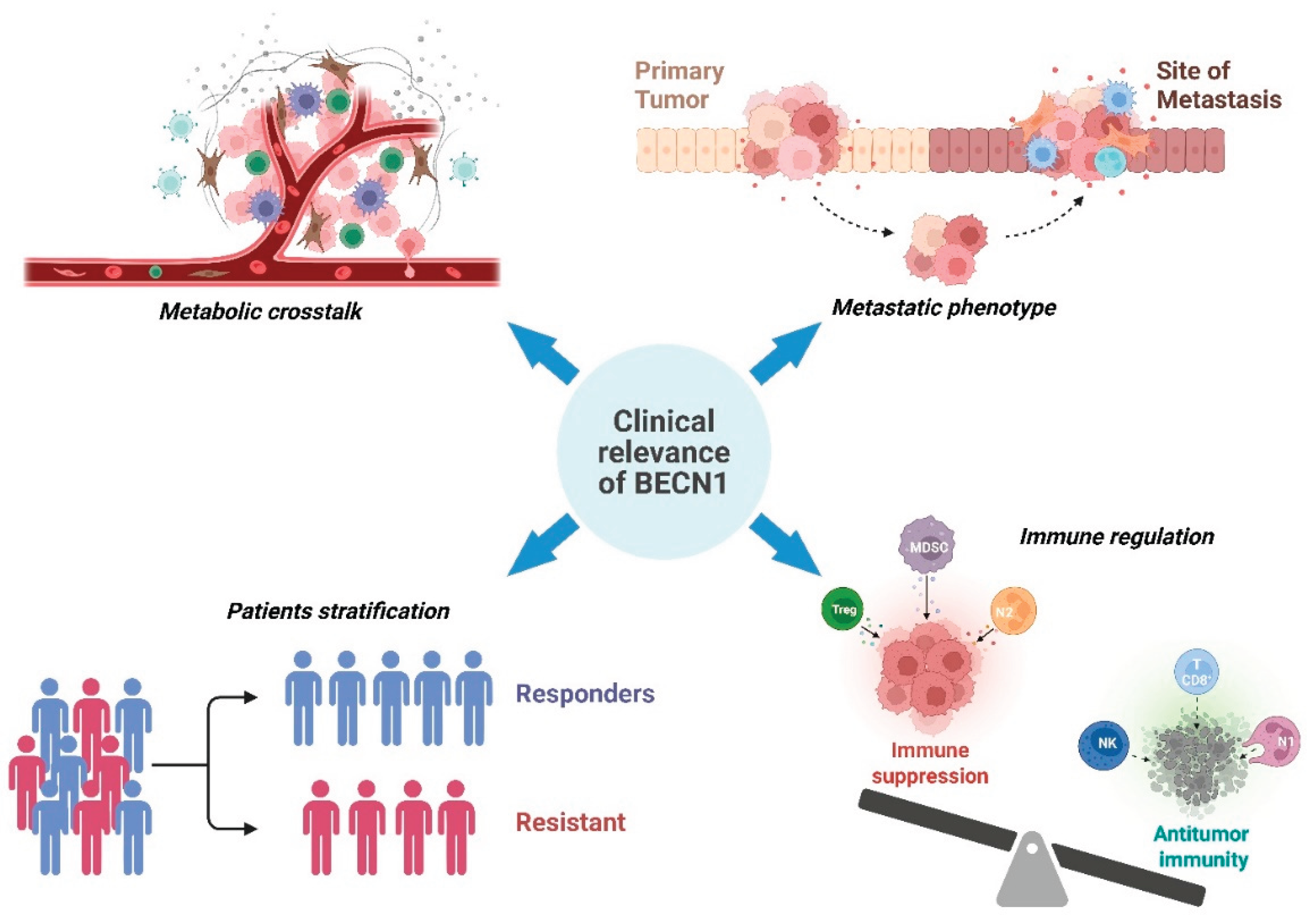

5. Clinical Implications and Biomarker Potential

5.1. Prognostic, Predictive, and Diagnostic Value of BECLIN-1 Across Cancer Types

5.2. Therapeutic Targeting of BECLIN-1 Dependent Pathways

6. Conclusions and Future Prospectives

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix Beclin-2

References

- Klionsky, D.J. Autophagy revisited: A conversation with Christian de Duve. Autophagy 2008, 4, 740–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mizushima, N. A brief history of autophagy from cell biology to physiology and disease. Nat. Cell Biol. 2018, 20, 521–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, X.H.; Kleeman, L.K.; Jiang, H.H.; Gordon, G.; Goldman, J.E.; Berry, G.; Herman, B.; Levine, B. Protection against Fatal Sindbis Virus Encephalitis by Beclin, a Novel Bcl-2-Interacting Protein. J. Virol. 1998, 72, 8586–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mizushima, N.; Levine, B.; Longo, D.L. Autophagy in Human Diseases. New Engl. J. Med. 2020, 383, 1564–1576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Virgilio, L.; Silva-Lucero, M.-D.; Flores-Morelos, D.-S.; Gallardo-Nieto, J.; Lopez-Toledo, G.; Abarca-Fernandez, A.-M.; Zacapala-Gómez, A.-E.; Luna-Muñoz, J.; Montiel-Sosa, F.; Soto-Rojas, L.O.; et al. Autophagy: A Key Regulator of Homeostasis and Disease: An Overview of Molecular Mechanisms and Modulators. Cells 2022, 11, 2262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klionsky, D.J.; Petroni, G.; Amaravadi, R.K.; Baehrecke, E.H.; Ballabio, A.; Boya, P.; Pedro, J.M.B.; Cadwell, K.; Cecconi, F.; Choi, A.M.K.; et al. Autophagy in major human diseases. EMBO J. 2021, 40, e108863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Yao, S.; Yang, H.; Liu, S.; Wang, Y. Autophagy: Regulator of cell death. Cell Death Dis. 2023, 14, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yun, C.W.; Jeon, J.; Go, G.; Lee, J.H.; Lee, S.H. The Dual Role of Autophagy in Cancer Development and a Therapeutic Strategy for Cancer by Targeting Autophagy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 22, 179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akkoc, Y.; Peker, N.; Akcay, A.; Gozuacik, D. Autophagy and Cancer Dormancy. Front. Oncol. 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, Z.; Tian, K.; Ran, Y.; Zhou, H.; Zhou, L.; Ding, Y.; Tang, X. Beclin-1: a therapeutic target at the intersection of autophagy, immunotherapy, and cancer treatment. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15, 1506426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esposito, A.; Ferraresi, A.; Salwa, A.; Vidoni, C.; Dhanasekaran, D.N.; Isidoro, C. Resveratrol Contrasts IL-6 Pro-Growth Effects and Promotes Autophagy-Mediated Cancer Cell Dormancy in 3D Ovarian Cancer: Role of miR-1305 and of Its Target ARH-I. Cancers 2022, 14, 2142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maheshwari, C.; Vidoni, C.; Titone, R.; Castiglioni, A.; Lora, C.; Follo, C.; Isidoro, C. Isolation, Characterization, and Autophagy Function of BECN1-Splicing Isoforms in Cancer Cells. Biomolecules 2022, 12, 1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, X.H.; Jackson, S.; Seaman, M.; Brown, K.; Kempkes, B.; Hibshoosh, H.; Levine, B. Induction of autophagy and inhibition of tumorigenesis by beclin 1. Nature 1999, 402, 672–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aita, V.M.; Liang, X.H.; Murty, V.; Pincus, D.L.; Yu, W.; Cayanis, E.; Kalachikov, S.; Gilliam, T.; Levine, B. Cloning and Genomic Organization of Beclin 1, a Candidate Tumor Suppressor Gene on Chromosome 17q21. Genomics 1999, 59, 59–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, H.; Sebti, S.; Titone, R.; Zhou, Y.; Isidoro, C.; Ross, T.S.; Hibshoosh, H.; Xiao, G.; Packer, M.; Xie, Y.; et al. Decreased BECN1 mRNA Expression in Human Breast Cancer is Associated With Estrogen Receptor-Negative Subtypes and Poor Prognosis. EBioMedicine 2015, 2, 255–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yue, Z.; Jin, S.; Yang, C.; Levine, A.J.; Heintz, N. Beclin 1, an autophagy gene essential for early embryonic development, is a haploinsufficient tumor suppressor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2003, 100, 15077–15082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qu, X.; Yu, J.; Bhagat, G.; Furuya, N.; Hibshoosh, H.; Troxel, A.; Rosen, J.; Eskelinen, E.-L.; Mizushima, N.; Ohsumi, Y.; et al. Promotion of tumorigenesis by heterozygous disruption of the beclin 1 autophagy gene. J. Clin. Investig. 2003, 112, 1809–1820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kihara, A.; Kabeya, Y.; Ohsumi, Y.; Yoshimori, T. Beclin–phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase complex functions at the trans -Golgi network. Embo Rep. 2001, 2, 330–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furuya, N.; Yu, J.; Byfield, M.; Pattingre, S.; Levine, B. The Evolutionarily Conserved Domain of Beclin 1 is Required for Vps34 Binding, Autophagy, and Tumor Suppressor Function. Autophagy 2005, 1, 46–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, C.; Feng, P.; Ku, B.; Dotan, I.; Canaani, D.; Oh, B.-H.; Jung, J.U. Autophagic and tumour suppressor activity of a novel Beclin1-binding protein UVRAG. Nat. Cell Biol. 2006, 8, 688–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Itakura, E.; Kishi, C.; Inoue, K.; Mizushima, N.; Subramani, S. Beclin 1 Forms Two Distinct Phosphatidylinositol 3-Kinase Complexes with Mammalian Atg14 and UVRAG. Mol. Biol. Cell 2008, 19, 5360–5372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noda, N.N.; Kobayashi, T.; Adachi, W.; Fujioka, Y.; Ohsumi, Y.; Inagaki, F. Structure of the Novel C-terminal Domain of Vacuolar Protein Sorting 30/Autophagy-related Protein 6 and Its Specific Role in Autophagy. J. Biol. Chem. 2012, 287, 16256–16266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menon, M.B.; Dhamija, S. Beclin 1 Phosphorylation–at the Center of Autophagy Regulation. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2018, 6, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peña-Martinez, C.; Rickman, A.D.; Heckmann, B.L. Beyond autophagy: LC3-associated phagocytosis and endocytosis. Sci. Adv. 2022, 8, eabn1702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ye, J.; Zhang, J.; Zhu, Y.; Wang, L.; Jiang, X.; Liu, B.; He, G. Targeting autophagy and beyond: Deconvoluting the complexity of Beclin-1 from biological function to cancer therapy. Acta Pharm. Sin. B 2023, 13, 4688–4714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montero-Vergara, J.; Plachetta, K.; Kinch, L.; Bernhardt, S.; Kashyap, K.; Levine, B.; Thukral, L.; Vetter, M.; Thomssen, C.; Wiemann, S.; et al. GRB2 is a BECN1 interacting protein that regulates autophagy. Cell Death Dis. 2024, 15, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Y.; Zhao, Z.; Li, J.; Li, J.; Luo, Y.; Li, W.; You, W.; Zhang, Y.; Li, Z.; Yang, J.; et al. Nuclear Beclin 1 Destabilizes Retinoblastoma Protein to Promote Cell Cycle Progression and Colorectal Cancer Growth. Cancers 2022, 14, 4735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.; Choi, W.; Hu, W.; Mi, N.; Guo, Q.; Ma, M.; Liu, M.; Tian, Y.; Lu, P.; Wang, F.-L.; et al. Crystal structure and biochemical analyses reveal Beclin 1 as a novel membrane binding protein. Cell Res. 2012, 22, 473–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pattingre, S.; Tassa, A.; Qu, X.; Garuti, R.; Liang, X.H.; Mizushima, N.; Packer, M.; Schneider, M.D.; Levine, B. Bcl-2 Antiapoptotic Proteins Inhibit Beclin 1-Dependent Autophagy. Cell 2005, 122, 927–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wyatt, S.; Glover, K.; Dasanna, S.; Lewison, M.; González-García, M.; Colbert, C.L.; Sinha, S.C. Epstein–Barr Virus Encoded BCL2, BHRF1, Downregulates Autophagy by Noncanonical Binding of BECN1. Biochemistry 2023, 62, 2934–2951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Z.; Baquero, M.T.; Yang, H.; Yang, M.; Reger, A.S.; Kim, C.; Levine, D.A.; Clarke, C.H.; Liao, W.S.-L.; Bast, R.C., Jr. DIRAS3 regulates the autophagosome initiation complex in dormant ovarian cancer cells. Autophagy 2014, 10, 1071–1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baek, S.; Chang, J.-W.; Yoo, S.-M.; Choo, J.; Jung, S.; Nah, J.; Jung, Y.-K. TMEM9 activates Rab9-dependent alternative autophagy through interaction with Beclin1. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2024, 81, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, Y.; Wang, Q.J.; Li, X.; Yan, Y.; Backer, J.M.; Chait, B.T.; Heintz, N.; Yue, Z. Distinct regulation of autophagic activity by Atg14L and Rubicon associated with Beclin 1–phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase complex. Nat. Cell Biol. 2009, 11, 468–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levine, B.; Liu, R.; Dong, X.; Zhong, Q. Beclin orthologs: integrative hubs of cell signaling, membrane trafficking, and physiology. Trends Cell Biol. 2015, 25, 533–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsunaga, K.; Saitoh, T.; Tabata, K.; Omori, H.; Satoh, T.; Kurotori, N.; Maejima, I.; Shirahama-Noda, K.; Ichimura, T.; Isobe, T.; et al. Two Beclin 1-binding proteins, Atg14L and Rubicon, reciprocally regulate autophagy at different stages. Nat. Cell Biol. 2009, 11, 385–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diao, J.; Liu, R.; Rong, Y.; Zhao, M.; Zhang, J.; Lai, Y.; Zhou, Q.; Wilz, L.M.; Li, J.; Vivona, S.; et al. ATG14 promotes membrane tethering and fusion of autophagosomes to endolysosomes. Nature 2015, 520, 563–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strappazzon, F.; Vietri-Rudan, M.; Campello, S.; Nazio, F.; Florenzano, F.; Fimia, G.M.; Piacentini, M.; Levine, B.; Cecconi, F. Mitochondrial BCL-2 inhibits AMBRA1-induced autophagy. EMBO J. 2011, 30, 1195–1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tran, S.; Fairlie, W.D.; Lee, E.F. BECLIN1: Protein Structure, Function and Regulation. Cells 2021, 10, 1522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levine, B.; Sinha, S.C.; Kroemer, G. Bcl-2 family members: Dual regulators of apoptosis and autophagy. Autophagy 2008, 4, 600–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Itakura, E.; Kishi, C.; Inoue, K.; Mizushima, N.; Subramani, S. Beclin 1 Forms Two Distinct Phosphatidylinositol 3-Kinase Complexes with Mammalian Atg14 and UVRAG. Mol. Biol. Cell 2008, 19, 5360–5372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, S.; Sil, P.; Martinez, J. Rubicon: LC3-associated phagocytosis and beyond. FEBS J. 2017, 285, 1379–1388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takahashi, Y.; Coppola, D.; Matsushita, N.; Cualing, H.D.; Sun, M.; Sato, Y.; Liang, C.; Jung, J.U.; Cheng, J.Q.; Mul, J.J.; et al. Bif-1 interacts with Beclin 1 through UVRAG and regulates autophagy and tumorigenesis. Nat. Cell Biol. 2007, 9, 1142–1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thoresen, S.B.; Pedersen, N.M.; Liestøl, K.; Stenmark, H. A phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase class III sub-complex containing VPS15, VPS34, Beclin 1, UVRAG and BIF-1 regulates cytokinesis and degradative endocytic traffic. Exp. Cell Res. 2010, 316, 3368–3378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furuya, N.; Yu, J.; Byfield, M.; Pattingre, S.; Levine, B. The Evolutionarily Conserved Domain of Beclin 1 is Required for Vps34 Binding, Autophagy, and Tumor Suppressor Function. Autophagy 2005, 1, 46–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baskaran, S.; Carlson, L.-A.; Stjepanovic, G.; Young, L.N.; Kim, D.J.; Grob, P.; Stanley, R.E.; Nogales, E.; Hurley, J.H. Architecture and dynamics of the autophagic phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase complex. eLife 2014, 3, e05115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rostislavleva, K.; Soler, N.; Ohashi, Y.; Zhang, L.; Pardon, E.; Burke, J.E.; Masson, G.R.; Johnson, C.; Steyaert, J.; Ktistakis, N.T.; et al. Structure and flexibility of the endosomal Vps34 complex reveals the basis of its function on membranes. Science 2015, 350, aac7365–aac7365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mei, Y.; Glover, K.; Su, M.; Sinha, S.C. Conformational flexibility of BECN1: Essential to its key role in autophagy and beyond. Protein Sci. 2016, 25, 1767–1785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fogel, A.I.; Dlouhy, B.J.; Wang, C.; Ryu, S.-W.; Neutzner, A.; Hasson, S.A.; Sideris, D.P.; Abeliovich, H.; Youle, R.J. Role of Membrane Association and Atg14-Dependent Phosphorylation in Beclin-1-Mediated Autophagy. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2013, 33, 3675–3688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, X.H.; Yu, J.; Brown, K.; Levine, B. Beclin 1 contains a leucine-rich nuclear export signal that is required for its autophagy and tumor suppressor function. . 2001, 61, 3443–9. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, F.; Fang, Y.; Yan, L.; Xu, L.; Zhang, S.; Cao, Y.; Xu, L.; Zhang, X.; Xie, J.; Jiang, G.; et al. Nuclear localization of Beclin 1 promotes radiation-induced DNA damage repair independent of autophagy. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, srep45385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laddha, S.V.; Ganesan, S.; Chan, C.S.; White, E. Mutational Landscape of the Essential Autophagy Gene BECN1 in Human Cancers. Mol. Cancer Res. 2014, 12, 485–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.E.; Yi, H.J.; Suh, N.; Park, Y.-Y.; Koh, J.-Y.; Jeong, S.-Y.; Cho, D.-H.; Kim, C.-S.; Hwang, J.J. Inhibition of EHMT2/G9a epigenetically increases the transcription ofBeclin-1via an increase in ROS and activation of NF-κB. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 39796–39808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Chen, B.; Wu, Y.; Jin, F.; Xia, Y.; Liu, X. Genetic and epigenetic silencing of the beclin 1gene in sporadic breast tumors. BMC Cancer 2010, 10, 98–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambrosio, S.; Saccà, C.D.; Amente, S.; Paladino, S.; Lania, L.; Majello, B. Lysine-specific demethylase LSD1 regulates autophagy in neuroblastoma through SESN2-dependent pathway. Oncogene 2017, 36, 6701–6711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, F.; Xiao, H.; Li, Q.-N.; Ren, X.-S.; Liu, Z.-G.; Hu, B.-W.; Wang, H.-S.; Wang, H.; Jiang, G.-M. Epigenetic and post-translational modifications in autophagy: biological functions and therapeutic targets. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2023, 8, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidoni, C.; Ferraresi, A.; Secomandi, E.; Vallino, L.; Dhanasekaran, D.N.; Isidoro, C. Epigenetic targeting of autophagy for cancer prevention and treatment by natural compounds. Semin. Cancer Biol. 2020, 66, 34–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polager, S.; Ofir, M.; Ginsberg, D. E2F1 regulates autophagy and the transcription of autophagy genes. Oncogene 2008, 27, 4860–4864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusama, Y.; Sato, K.; Kimura, N.; Mitamura, J.; Ohdaira, H.; Yoshida, K. Comprehensive analysis of expression pattern and promoter regulation of human autophagy-related genes. Apoptosis 2009, 14, 1165–1175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Ling, S.; Lin, W.-C.; Jin, D.-Y. 14-3-3τ Regulates Beclin 1 and Is Required for Autophagy. PLOS ONE 2010, 5, e10409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, R.; Zeh, H.J.; Lotze, M.T.; Tang, D. The Beclin 1 network regulates autophagy and apoptosis. Cell Death Differ. 2011, 18, 571–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Copetti, T.; Bertoli, C.; Dalla, E.; Demarchi, F.; Schneider, C. p65/RelA Modulates BECN1 Transcription and Autophagy. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2009, 29, 2594–2608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, C.-W.; Chang, H.-T.; Wu, C.-S.; Chen, C.-H.; Wu, S.; Chang, H.-W.; Kuo, S.-Y.; Fu, E.; Liu, P.-F.; Hsieh, Y.-D.; et al. RelA-Mediated BECN1 Expression Is Required for Reactive Oxygen Species-Induced Autophagy in Oral Cancer Cells Exposed to Low-Power Laser Irradiation. PLOS ONE 2016, 11, e0160586–e0160586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, F.; Ghislat, G.; Luo, S.; Renna, M.; Siddiqi, F.; Rubinsztein, D.C. XIAP and cIAP1 amplifications induce Beclin 1-dependent autophagy through NFκB activation. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2015, 24, 2899–2913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, T.; Guo, M.; Gan, M.; Yu, B.; Tian, X.; Wang, J.-B. TRIM59 regulates autophagy through modulating both the transcription and the ubiquitination of BECN1. Autophagy 2018, 14, 2035–2048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, W.; Swaminathan, G.; Plowey, E.D. GA binding protein augments autophagy via transcriptional activation ofBECN1-PIK3C3complex genes. Autophagy 2014, 10, 1622–1636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamurcu, Z.; Delibaşı, N.; Nalbantoglu, U.; Sener, E.F.; Nurdinov, N.; Tascı, B.; Taheri, S.; Özkul, Y.; Donmez-Altuntas, H.; Canatan, H.; et al. FOXM1 plays a role in autophagy by transcriptionally regulating Beclin-1 and LC3 genes in human triple-negative breast cancer cells. J. Mol. Med. 2019, 97, 491–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, J.; Zhang, H.-B.; Shi, Q.; Yang, C.; Ma, J.-B.; Jin, B.; Wang, X.; He, D.; Guo, P. KLF5 downregulation desensitizes castration-resistant prostate cancer cells to docetaxel by increasing BECN1 expression and inducing cell autophagy. Theranostics 2019, 9, 5464–5477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miao, L.-J.; Huang, F.-X.; Sun, Z.-T.; Zhang, R.-X.; Huang, S.-F.; Wang, J. Stat3 inhibits Beclin 1 expression through recruitment of HDAC3 in nonsmall cell lung cancer cells. Tumor Biol. 2014, 35, 7097–7103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, H.; Wu, H.; Liu, X.; Li, B.; Chen, Y.; Ren, X.; Liu, C.-G.; Yang, J.-M. Regulation of autophagy by a beclin 1-targeted microRNA, miR-30a, in cancer cells. Autophagy 2009, 5, 816–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korkmaz, G.; le Sage, C.; Tekirdag, K.A.; Agami, R.; Gozuacik, D. miR-376b controls starvation and mTOR inhibition-related autophagy by targeting ATG4C and BECN1. Autophagy 2012, 8, 165–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, W.; Song, L.; Zhao, Y.; Liu, Q.; Zhang, S. Inhibition of Beclin-1-Mediated Autophagy by MicroRNA-17-5p Enhanced the Radiosensitivity of Glioma Cells. Oncol. Res. Featur. Preclin. Clin. Cancer Ther. 2017, 25, 43–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comincini, S.; Allavena, G.; Palumbo, S.; Morini, M.; Durando, F.; Angeletti, F.; Pirtoli, L.; Miracco, C. microRNA-17 regulates the expression of ATG7 and modulates the autophagy process, improving the sensitivity to temozolomide and low-dose ionizing radiation treatments in human glioblastoma cells. Cancer Biol. Ther. 2013, 14, 574–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, T.; Wan, X.; Alvarez, A.A.; James, C.D.; Song, X.; Yang, Y.; Sastry, N.; Nakano, I.; Sulman, E.P.; Hu, B.; et al. MIR93(microRNA -93) regulates tumorigenicity and therapy response of glioblastoma by targeting autophagy. Autophagy 2019, 15, 1100–1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Shi, H.; Lin, S.; Ba, M.; Cui, S. MicroRNA-216a enhances the radiosensitivity of pancreatic cancer cells by inhibiting beclin-1-mediated autophagy. Oncol. Rep. 2015, 34, 1557–1564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, A.; Chattopadhyay, D.; Chakrabarti, G.; Mari, B. miR-17-5p Downregulation Contributes to Paclitaxel Resistance of Lung Cancer Cells through Altering Beclin1 Expression. PLOS ONE 2014, 9, e95716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, C.; Zou, J.; Zheng, G.; Chu, J. MiR-30a Decreases Multidrug Resistance (MDR) of Gastric Cancer Cells. Med Sci. Monit. 2016, 22, 4509–4515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, X.; Bai, F.; Xu, Y.; Chen, Y.; Chen, L. Intensified Beclin-1 Mediated by Low Expression of Mir-30a-5p Promotes Chemoresistance in Human Small Cell Lung Cancer. Cell. Physiol. Biochem. 2017, 43, 1126–1139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zou, Z.; Wu, L.; Ding, H.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, X.; Chen, X.; Zhang, C.-Y.; Zhang, Q.; Zen, K. MicroRNA-30a Sensitizes Tumor Cells to cis-Platinum via Suppressing Beclin 1-mediated Autophagy. J. Biol. Chem. 2012, 287, 4148–4156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Li, Z.; Liu, H.; Jiang, S.; Wang, G.; Sun, L.; Li, J.; Wang, X.; Yu, S.; Huang, J.; et al. MicroRNA-30a targets BECLIN-1 to inactivate autophagy and sensitizes gastrointestinal stromal tumor cells to imatinib. Cell Death Dis. 2020, 11, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Yang, L.; Zhao, M.; Zhu, S.; Kang, R.; Vernon, P.; Tang, D.; Cao, L. Targeting microRNA-30a-mediated autophagy enhances imatinib activity against human chronic myeloid leukemia cells. Leukemia 2012, 26, 1752–1760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, S.; Shi, H.; Ba, M.; Lin, S.; Tang, H.; Zeng, X.; Zhang, X. miR-409-3p sensitizes colon cancer cells to oxaliplatin by inhibiting Beclin-1-mediated autophagy. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2016, 37, 1030–1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Han, X.; Hu, Z.; Chen, L. The PVT1/miR-216b/Beclin-1 regulates cisplatin sensitivity of NSCLC cells via modulating autophagy and apoptosis. Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol. 2019, 83, 921–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, M.; Wu, L.; Zhang, K.; Wang, H.; Wu, S.; O'Connell, D.; Gao, T.; Zhong, H.; Yang, Y. miR-216b enhances the efficacy of vemurafenib by targeting Beclin-1, UVRAG and ATG5 in melanoma. Cell. Signal. 2018, 42, 30–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pradhan, A.K.; Talukdar, S.; Bhoopathi, P.; Shen, X.-N.; Emdad, L.; Das, S.K.; Sarkar, D.; Fisher, P.B. mda-7/IL-24 Mediates Cancer Cell–Specific Death via Regulation of miR-221 and the Beclin-1 Axis. Cancer Res. 2017, 77, 949–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Chen, X.; Wang, D.; Gan, L.; Qiao, Y. Effects of miR-26a on the expression of Beclin 1 in retinoblastoma cells. Genet. Mol. Res. 2016, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, F.; Wang, B.; Long, H.; Yu, J.; Li, F.; Hou, H.; Yang, Q. Decreased miR-124-3p Expression Prompted Breast Cancer Cell Progression Mainly by Targeting Beclin-1. Clin. Lab. 2016, 62, 1139–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nadhan, R.; Isidoro, C.; Song, Y.S.; Dhanasekaran, D.N. Signaling by LncRNAs: Structure, Cellular Homeostasis, and Disease Pathology. Cells 2022, 11, 2517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Xie, S.; Yang, J.; Xiong, H.; Jia, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Chen, Y.; Ying, X.; Chen, C.; Ye, C.; et al. The long noncoding RNA H19 promotes tamoxifen resistance in breast cancer via autophagy. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2019, 12, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, L.; Han, X.; Hu, Z.; Chen, L. The PVT1/miR-216b/Beclin-1 regulates cisplatin sensitivity of NSCLC cells via modulating autophagy and apoptosis. Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol. 2019, 83, 921–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Li, C.; Chen, Y.; Teng, L.; Cao, Y.; Wang, W.; Pan, H.; Xu, Y.; Yang, D. LncRNA HOTAIR induces sunitinib resistance in renal cancer by acting as a competing endogenous RNA to regulate autophagy of renal cells. Cancer Cell Int. 2020, 20, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Wang, Y.; Xia, S.; Yang, L.; Wu, D.; Zhou, Y.; Lu, J. Long noncoding RNA PANDAR inhibits the development of lung cancer by regulating autophagy and apoptosis pathways. J. Cancer 2020, 11, 4783–4790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, N.; Wen, K. The role of lncRNA binding to RNA-binding proteins to regulate mRNA stability in cancer progression and drug resistance mechanisms (Review). Oncol. Rep. 2024, 52, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Li, Z.; Xu, S.; Li, W.; Chen, M.; Jiang, M.; Fan, X. LncRNA FIRRE functions as a tumor promoter by interaction with PTBP1 to stabilize BECN1 mRNA and facilitate autophagy. Cell Death Dis. 2022, 13, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Zhong, X.; Sun, X.; Fan, J. The RNA-binding protein ELAVL1 promotes Beclin1-mediated cellular autophagy and thus endometrial cancer development by affecting LncRNA-neat stability. Cancer Biol. Ther. 2025, 26, 2469927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, B.; Xu, A.; Qiao, M.; Wu, Q.; Wang, W.; Mei, Y.; Wu, M. BECN1s, a short splice variant of BECN1, functions in mitophagy. Autophagy 2015, 11, 2048–2056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niu, Y.-N.; Liu, Q.-Q.; Zhang, S.-P.; Yuan, N.; Cao, Y.; Cai, J.-Y.; Lin, W.-W.; Xu, F.; Wang, Z.-J.; Chen, B.; et al. Alternative Messenger RNA Splicing of Autophagic Gene Beclin 1 in Human B-cell Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia Cells. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 2014, 15, 2153–2158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hill, S.M.; Wrobel, L.; Rubinsztein, D.C. Post-translational modifications of Beclin 1 provide multiple strategies for autophagy regulation. Cell Death Differ. 2018, 26, 617–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, S.; Tian, S.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, C.; Xie, W.; Xia, X.; Cui, J.; Wang, R. USP19 modulates autophagy and antiviral immune responses by deubiquitinating Beclin-1. EMBO J. 2016, 35, 866–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, J.; Wu, S.; Zhao, S.; Wang, L.; Wu, Y.; Song, L.; Sun, C.; Liu, Y.; Liu, Z.; Zhu, R.; et al. USP24 promotes autophagy-dependent ferroptosis in hepatocellular carcinoma by reducing the K48-linked ubiquitination of Beclin1. Commun. Biol. 2024, 7, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Wang, Y.; Luo, Y.; Liu, Y.; Yi, Y.; Li, J.; Pan, Y.; Li, W.; You, W.; Hu, Q.; et al. USP5-Beclin 1 axis overrides p53-dependent senescence and drives Kras-induced tumorigenicity. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Xia, H.; Kim, M.; Xu, L.; Li, Y.; Zhang, L.; Cai, Y.; Norberg, H.V.; Zhang, T.; Furuya, T.; et al. Beclin1 Controls the Levels of p53 by Regulating the Deubiquitination Activity of USP10 and USP13. Cell 2011, 147, 223–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rong, Y.; Fan, J.; Ji, C.; Wang, Z.; Ge, X.; Wang, J.; Ye, W.; Yin, G.; Cai, W.; Liu, W. USP11 regulates autophagy-dependent ferroptosis after spinal cord ischemia-reperfusion injury by deubiquitinating Beclin 1. Cell Death Differ. 2021, 29, 1164–1175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Z.; Rao, S.; Song, C.; Zhu, M.; Zhao, H.; Yuan, S.; Peng, B.; Xu, X. Ubiquitin carboxyl-terminal hydrolase 11 promotes autophagy by de-ubiquitinating and stabilizing Beclin-1. Genome Instab. Dis. 2022, 3, 47–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, D.; Shan, B.; Sun, H.; Xiao, J.; Zhu, K.; Xie, X.; Li, X.; Liang, W.; Lu, X.; Qian, L.; et al. USP14 regulates autophagy by suppressing K63 ubiquitination of Beclin 1. Genes Dev. 2016, 30, 1718–1730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, L.; Liu, X.; Jiang, X.; Zhang, K.; Wang, Y.; Li, X.; Jiang, S.; Han, T. USP10 as a Potential Therapeutic Target in Human Cancers. Genes 2022, 13, 831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Yang, K.-B.; Chen, W.; Mai, J.; Wu, X.-Q.; Sun, T.; Wu, R.-Y.; Jiao, L.; Li, D.-D.; Ji, J.; et al. CUL3 (cullin 3)-mediated ubiquitination and degradation of BECN1 (beclin 1) inhibit autophagy and promote tumor progression. Autophagy 2021, 17, 4323–4340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, C.; Feng, K.; Zhao, X.; Huang, S.; Cheng, Y.; Qian, L.; Wang, Y.; Sun, H.; Jin, M.; Chuang, T.-H.; et al. Regulation of autophagy by E3 ubiquitin ligase RNF216 through BECN1 ubiquitination. Autophagy 2014, 10, 2239–2250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, C.-S.; Kehrl, J.H. TRAF6 and A20 Regulate Lysine 63–Linked Ubiquitination of Beclin-1 to Control TLR4-Induced Autophagy. Sci. Signal. 2010, 3, ra42–ra42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, P.; Wang, S.; Du, Y.; Zhao, Z.; Shi, L.; Sun, L.; Huang, G.; Ye, B.; Li, C.; Dai, Z.; et al. WASH inhibits autophagy through suppression of Beclin 1 ubiquitination. EMBO J. 2013, 32, 2685–2696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Platta, H.W.; Abrahamsen, H.; Thoresen, S.B.; Stenmark, H. Nedd4-dependent lysine-11-linked polyubiquitination of the tumour suppressor Beclin 1. Biochem. J. 2011, 441, 399–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, C.; Liu, J.; Hsu, L.; Luo, Y.; Xiang, R.; Chuang, T. Functional interaction of heat shock protein 90 and Beclin 1 modulates Toll-like receptor-mediated autophagy. FASEB J. 2011, 25, 2700–2710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, T.; Li, X.; Zhang, P.; Chen, W.-D.; Zhang, H.-L.; Li, D.-D.; Deng, R.; Qian, X.-J.; Jiao, L.; Ji, J.; et al. Acetylation of Beclin 1 inhibits autophagosome maturation and promotes tumour growth. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 7215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Liu, X.; Tong, H.; Yin, H.; Li, T.; Zhu, J.; Chen, J.; Wu, L.; Zhang, X.; Gou, X.; et al. SIRT1 Promotes Cisplatin Resistance in Bladder Cancer via Beclin1 Deacetylation-Mediated Autophagy. Cancers 2023, 16, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, R.C.; Tian, Y.; Yuan, H.; Park, H.W.; Chang, Y.-Y.; Kim, J.; Kim, H.; Neufeld, T.P.; Dillin, A.; Guan, K.-L. ULK1 induces autophagy by phosphorylating Beclin-1 and activating VPS34 lipid kinase. Nat. Cell Biol. 2013, 15, 741–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Shaha, C. SESN2 facilitates mitophagy by helping Parkin translocation through ULK1 mediated Beclin1 phosphorylation. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qian, X.; Li, X.; Cai, Q.; Zhang, C.; Yu, Q.; Jiang, Y.; Lee, J.-H.; Hawke, D.; Wang, Y.; Xia, Y.; et al. Phosphoglycerate Kinase 1 Phosphorylates Beclin1 to Induce Autophagy. Mol. Cell 2017, 65, 917–931.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, Y.; An, Z.; Zou, Z.; Sumpter, R.; Su, M.; Zang, X.; Sinha, S.; Gaestel, M.; Levine, B.; Center, U.S.M.; et al. The stress-responsive kinases MAPKAPK2/MAPKAPK3 activate starvation-induced autophagy through Beclin 1 phosphorylation. eLife 2015, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujiwara, N.; Usui, T.; Ohama, T.; Sato, K. Regulation of Beclin 1 Protein Phosphorylation and Autophagy by Protein Phosphatase 2A (PP2A) and Death-associated Protein Kinase 3 (DAPK3). J. Biol. Chem. 2016, 291, 10858–10866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Wu, X.-Q.; Deng, R.; Li, D.-D.; Tang, J.; Chen, W.-D.; Chen, J.-H.; Ji, J.; Jiao, L.; Jiang, S.; et al. CaMKII-mediated Beclin 1 phosphorylation regulates autophagy that promotes degradation of Id and neuroblastoma cell differentiation. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, Q.; Wang, S.; Zhang, S.; Xu, H.; Li, X.; Guan, Y.; Yi, F.; Zhou, T.; Jiang, B.; Bai, N.; et al. ATM - CHK 2-Beclin 1 axis promotes autophagy to maintain ROS homeostasis under oxidative stress. EMBO J. 2020, 39, e103111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Kim, Y.C.; Fang, C.; Russell, R.C.; Kim, J.H.; Fan, W.; Liu, R.; Zhong, Q.; Guan, K.-L. Differential Regulation of Distinct Vps34 Complexes by AMPK in Nutrient Stress and Autophagy. Cell 2013, 152, 290–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zalckvar, E.; Berissi, H.; Mizrachy, L.; Idelchuk, Y.; Koren, I.; Eisenstein, M.; Sabanay, H.; Pinkas-Kramarski, R.; Kimchi, A. DAP-kinase-mediated phosphorylation on the BH3 domain of beclin 1 promotes dissociation of beclin 1 from Bcl-XL and induction of autophagy. Embo Rep. 2009, 10, 285–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maejima, Y.; Kyoi, S.; Zhai, P.; Liu, T.; Li, H.; Ivessa, A.; Sciarretta, S.; Del Re, D.P.; Zablocki, D.K.; Hsu, C.-P.; et al. Mst1 inhibits autophagy by promoting the interaction between Beclin1 and Bcl-2. Nat. Med. 2013, 19, 1478–1488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A Ciechomska, I.; Goemans, G.C.; Skepper, J.N.; Tolkovsky, A.M. Bcl-2 complexed with Beclin-1 maintains full anti-apoptotic function. Oncogene 2009, 28, 2128–2141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Y.; Sinha, S.C.; Levine, B. Dual Role of JNK1-mediated phosphorylation of Bcl-2 in autophagy and apoptosis regulation. Autophagy 2008, 4, 949–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zalckvar, E.; Berissi, H.; Eisenstein, M.; Kimchi, A. Phosphorylation of Beclin 1 by DAP-kinase promotes autophagy by weakening its interactions with Bcl-2 and Bcl-XL. Autophagy 2009, 5, 720–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiloh, R.; Gilad, Y.; Ber, Y.; Eisenstein, M.; Aweida, D.; Bialik, S.; Cohen, S.; Kimchi, A. Non-canonical activation of DAPK2 by AMPK constitutes a new pathway linking metabolic stress to autophagy. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 1759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurkar, A.U.; Chu, K.; Raj, L.; Bouley, R.; Lee, S.-H.; Kim, Y.-B.; Dunn, S.E.; Mandinova, A.; Lee, S.W. Identification of ROCK1 kinase as a critical regulator of Beclin1-mediated autophagy during metabolic stress. Nat. Commun. 2013, 4, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, F.; Song, D.; Yan, Y.; Huang, C.; Shen, C.; Lan, J.; Chen, Y.; Liu, A.; Wu, Q.; Sun, L.; et al. IL-6 regulates autophagy and chemotherapy resistance by promoting BECN1 phosphorylation. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Wang, W.; Sun, X.; Xu, D.; Wang, C.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, H.; Luo, W.; Chen, Y.; Chen, H.; et al. AMPK regulates autophagy by phosphorylating BECN1 at threonine 388. Autophagy 2016, 12, 1447–1459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Y.; Zou, Z.; Becker, N.; Anderson, M.; Sumpter, R.; Xiao, G.; Kinch, L.; Koduru, P.; Christudass, C.S.; Veltri, R.W.; et al. EGFR-Mediated Beclin 1 Phosphorylation in Autophagy Suppression, Tumor Progression, and Tumor Chemoresistance. Cell 2013, 154, 1269–1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.; Hou, W.; Lu, C.; Goldstein, L.A.; Stolz, D.B.; Watkins, S.C.; Rabinowich, H. Interaction between Her2 and Beclin-1 Proteins Underlies a New Mechanism of Reciprocal Regulation. J. Biol. Chem. 2013, 288, 20315–20325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levine, B.; Liu, R.; Dong, X.; Zhong, Q. Beclin orthologs: integrative hubs of cell signaling, membrane trafficking, and physiology. Trends Cell Biol. 2015, 25, 533–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, C.; Gorantla, S.P.; Müller-Rudorf, A.; Müller, T.A.; Kreutmair, S.; Albers, C.; Jakob, L.; Lippert, L.J.; Yue, Z.; Engelhardt, M.; et al. Phosphorylation of BECLIN-1 by BCR-ABL suppresses autophagy in chronic myeloid leukemia. Haematologica 2019, 105, 1285–1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.C.; Wei, Y.; An, Z.; Zou, Z.; Xiao, G.; Bhagat, G.; White, M.; Reichelt, J.; Levine, B. Akt-Mediated Regulation of Autophagy and Tumorigenesis Through Beclin 1 Phosphorylation. Science 2012, 338, 956–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phadngam, S.; Castiglioni, A.; Ferraresi, A.; Morani, F.; Follo, C.; Isidoro, C. PTEN dephosphorylates AKT to prevent the expression of GLUT1 on plasmamembrane and to limit glucose consumption in cancer cells. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 84999–85020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prerna, K.; Dubey, V.K. Beclin1-mediated interplay between autophagy and apoptosis: New understanding. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2022, 204, 258–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wirawan, E.; Vande Walle, L.; Kersse, K.; Cornelis, S.; Claerhout, S.; Vanoverberghe, I.; Roelandt, R.; De Rycke, R.; Verspurten, J.; Declercq, W.; et al. Caspase-mediated cleavage of Beclin-1 inactivates Beclin-1-induced autophagy and enhances apoptosis by promoting the release of proapoptotic factors from mitochondria. Cell Death Dis. 2010, 1, e18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Zhao, L.; Liu, L.; Gao, P.; Tian, W.; Wang, X.; Jin, H.; Xu, H.; Chen, Q. Beclin 1 cleavage by caspase-3 inactivates autophagy and promotes apoptosis. Protein Cell 2010, 1, 468–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Wang, P.; Yu, J.; Zhang, L. Cleaving Beclin 1 to suppress autophagy in chemotherapy-induced apoptosis. Autophagy 2011, 7, 1239–1241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddiqui, M.A.; Mukherjee, S.; Manivannan, P.; Malathi, K. RNase L Cleavage Products Promote Switch from Autophagy to Apoptosis by Caspase-Mediated Cleavage of Beclin-1. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2015, 16, 17611–17636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, F.; Li, G.; Huang, C.; Hou, Z.; Yang, X.; Luo, X.; Feng, Y.; Wang, G.; Hu, J.; Cao, Z. The autophagy-independent role of BECN1 in colorectal cancer metastasis through regulating STAT3 signaling pathway activation. Cell Death Dis. 2020, 11, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’dOnovan, T.R.; O’sUllivan, G.C.; McKenna, S.L. Induction of autophagy by drug-resistant esophageal cancer cells promotes their survival and recovery following treatment with chemotherapeutics. Autophagy 2011, 7, 509–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vargas, J.N.S.; Hamasaki, M.; Kawabata, T.; Youle, R.J.; Yoshimori, T. The mechanisms and roles of selective autophagy in mammals. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2022, 24, 167–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.V.; Mills, J.; Lapierre, L.R. Selective Autophagy Receptor p62/SQSTM1, a Pivotal Player in Stress and Aging. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2022, 10, 793328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashrafi, G.; Schwarz, T.L. The pathways of mitophagy for quality control and clearance of mitochondria. Cell Death Differ. 2012, 20, 31–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saraste, M. Oxidative Phosphorylation at the fin de siècle. Science 1999, 283, 1488–1493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallace, D.C. A Mitochondrial Paradigm of Metabolic and Degenerative Diseases, Aging, and Cancer: A Dawn for Evolutionary Medicine. Annu. Rev. Genet. 2005, 39, 359–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parsons, M.J.; Green, D.R.; Brown, G.C.; Murphy, M.P. Mitochondria in cell death. Essays Biochem. 2010, 47, 99–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazarou, M.; Jin, S.M.; Kane, L.A.; Youle, R.J. Role of PINK1 Binding to the TOM Complex and Alternate Intracellular Membranes in Recruitment and Activation of the E3 Ligase Parkin. Dev. Cell 2012, 22, 320–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narendra, D.P.; Jin, S.M.; Tanaka, A.; Suen, D.-F.; Gautier, C.A.; Shen, J.; Cookson, M.R.; Youle, R.J.; Green, D.R. PINK1 Is Selectively Stabilized on Impaired Mitochondria to Activate Parkin. PLOS Biol. 2010, 8, e1000298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Narendra, D.; Tanaka, A.; Suen, D.-F.; Youle, R.J. Parkin is recruited selectively to impaired mitochondria and promotes their autophagy. J. Cell Biol. 2008, 183, 795–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.; Gao, F.; Li, B.; Wang, H.; Xu, Y.; Zhu, C.; Wang, G. Parkin Mono-ubiquitinates Bcl-2 and Regulates Autophagy. J. Biol. Chem. 2010, 285, 38214–38223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michiorri, S.; Gelmetti, V.; Giarda, E.; Lombardi, F.; Romano, F.; Marongiu, R.; Nerini-Molteni, S.; Sale, P.; Vago, R.; Arena, G.; et al. The Parkinson-associated protein PINK1 interacts with Beclin1 and promotes autophagy. Cell Death Differ. 2010, 17, 962–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choubey, V.; Cagalinec, M.; Liiv, J.; Safiulina, D.; A Hickey, M.; Kuum, M.; Liiv, M.; Anwar, T.; Eskelinen, E.-L.; Kaasik, A. BECN1 is involved in the initiation of mitophagy. Autophagy 2014, 10, 1105–1119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gelmetti, V.; De Rosa, P.; Torosantucci, L.; Marini, E.S.; Romagnoli, A.; Di Rienzo, M.; Arena, G.; Vignone, D.; Fimia, G.M.; Valente, E.M. PINK1 and BECN1 relocalize at mitochondria-associated membranes during mitophagy and promote ER-mitochondria tethering and autophagosome formation. Autophagy 2017, 13, 654–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quiles, J.M.; Najor, R.H.; Gonzalez, E.; Jeung, M.; Liang, W.; Burbach, S.M.; Zumaya, E.A.; Diao, R.Y.; Lampert, M.A.; Gustafsson, Å.B. Deciphering functional roles and interplay between Beclin1 and Beclin2 in autophagosome formation and mitophagy. Sci. Signal. 2023, 16, eabo4457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Humbeeck, C.; Cornelissen, T.; Vandenberghe, W. Ambra1. Autophagy 2011, 7, 1555–1556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadopoulos, C.; Kravic, B.; Meyer, H. Repair or Lysophagy: Dealing with Damaged Lysosomes. J. Mol. Biol. 2020, 432, 231–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, S.; Chauhan, S.; Jain, A.; Ponpuak, M.; Choi, S.W.; Mudd, M.; Peters, R.; Mandell, M.A.; Johansen, T.; Deretic, V. Galectins and TRIMs directly interact and orchestrate autophagic response to endomembrane damage. Autophagy 2017, 13, 1086–1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chauhan, S.; Kumar, S.; Jain, A.; Ponpuak, M.; Mudd, M.H.; Kimura, T.; Choi, S.W.; Peters, R.; Mandell, M.; Bruun, J.-A.; et al. TRIMs and Galectins Globally Cooperate and TRIM16 and Galectin-3 Co-direct Autophagy in Endomembrane Damage Homeostasis. Dev. Cell 2016, 39, 13–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimura, T.; Jain, A.; Choi, S.W.; Mandell, M.A.; Schroder, K.; Johansen, T.; Deretic, V. TRIM-mediated precision autophagy targets cytoplasmic regulators of innate immunity. J. Cell Biol. 2015, 210, 973–989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baek, S.; Chang, J.-W.; Yoo, S.-M.; Choo, J.; Jung, S.; Nah, J.; Jung, Y.-K. TMEM9 activates Rab9-dependent alternative autophagy through interaction with Beclin1. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2024, 81, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sigismund, S.; Lanzetti, L.; Scita, G.; Di Fiore, P.P. Endocytosis in the context-dependent regulation of individual and collective cell properties. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2021, 22, 625–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raiborg, C.; Schink, K.O.; Stenmark, H. Class III phosphatidylinositol 3–kinase and its catalytic product PtdIns3P in regulation of endocytic membrane traffic. FEBS J. 2013, 280, 2730–2742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McKnight, N.C.; Zhong, Y.; Wold, M.S.; Gong, S.; Phillips, G.R.; Dou, Z.; Zhao, Y.; Heintz, N.; Zong, W.-X.; Yue, Z.; et al. Beclin 1 Is Required for Neuron Viability and Regulates Endosome Pathways via the UVRAG-VPS34 Complex. PLOS Genet. 2014, 10, e1004626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruck, A.; Attonito, J.; Garces, K.T.; Nuñez, L.; Palmisano, N.J.; Rubel, Z.; Bai, Z.; Nguyen, K.C.; Sun, L.; Grant, B.D.; et al. The Atg6/Vps30/Beclin 1 ortholog BEC-1 mediates endocytic retrograde transport in addition to autophagy inC. elegans. Autophagy 2011, 7, 386–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawe, D.C.; Chawla, A.; Merithew, E.; Dumas, J.; Carrington, W.; Fogarty, K.; Lifshitz, L.; Tuft, R.; Lambright, D.; Corvera, S. Sequential Roles for Phosphatidylinositol 3-Phosphate and Rab5 in Tethering and Fusion of Early Endosomes via Their Interaction with EEA1. J. Biol. Chem. 2002, 277, 8611–8617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonard, D.; Hayakawa, A.; Lawe, D.; Lambright, D.; Bellve, K.D.; Standley, C.; Lifshitz, L.M.; Fogarty, K.E.; Corvera, S. Sorting of EGF and transferrin at the plasma membrane and by cargo-specific signaling to EEA1-enriched endosomes. J. Cell Sci. 2008, 121, 3445–3458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A Rohatgi, R.; Janusis, J.; Leonard, D.; Bellvé, K.D.; E Fogarty, K.; Baehrecke, E.H.; Corvera, S.; Shaw, L.M. Beclin 1 regulates growth factor receptor signaling in breast cancer. Oncogene 2015, 34, 5352–5362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Lu, Y.; Zhang, T.; Yu, X.; Wang, Q.; Chi, Y.; Jin, S.; Cheng, G. CMTM7 as a novel molecule of ATG14L-Beclin1-VPS34 complex enhances autophagy by Rab5 to regulate tumorigenicity. Cell Commun. Signal. 2021, 19, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Su, Y.; Li, T.; Yuan, W.; Mo, X.; Li, H.; He, Q.; Ma, D.; Han, W. CMTM7 knockdown increases tumorigenicity of human non-small cell lung cancer cells and EGFR-AKT signaling by reducing Rab5 activation. Oncotarget 2015, 6, 41092–41107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Backer, J.M. The intricate regulation and complex functions of the Class III phosphoinositide 3-kinase Vps34. Biochem. J. 2016, 473, 2251–2271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Law, F.; Rocheleau, C.E. Vps34 and the Armus/TBC-2 Rab GAPs: Putting the brakes on the endosomal Rab5 and Rab7 GTPases. Cell. Logist. 2017, 7, e1403530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pei, Y.; Lv, S.; Shi, Y.; Jia, J.; Ma, M.; Han, H.; Zhang, R.; Tan, J.; Zhang, X. RAB21 controls autophagy and cellular energy homeostasis by regulating retromer-mediated recycling of SLC2A1/GLUT1. Autophagy 2022, 19, 1070–1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bakker, J.; Spits, M.; Neefjes, J.; Berlin, I. The EGFR odyssey – from activation to destruction in space and time. J. Cell Sci. 2017, 130, 4087–4096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthew-Onabanjo, A.N.; Janusis, J.; Mercado-Matos, J.; Carlisle, A.E.; Kim, D.; Levine, F.; Cruz-Gordillo, P.; Richards, R.; Lee, M.J.; Shaw, L.M. Beclin 1 Promotes Endosome Recruitment of Hepatocyte Growth Factor Tyrosine Kinase Substrate to Suppress Tumor Proliferation. Cancer Res. 2020, 80, 249–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wijshake, T.; Zou, Z.; Chen, B.; Zhong, L.; Xiao, G.; Xie, Y.; Doench, J.G.; Bennett, L.; Levine, B. Tumor-suppressor function of Beclin 1 in breast cancer cells requires E-cadherin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2021, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, S.; Juliani, J.; Harris, T.J.; Evangelista, M.; Ratcliffe, J.; Ellis, S.L.; Baloyan, D.; Reehorst, C.M.; Nightingale, R.; Luk, I.Y.; et al. BECLIN1 is essential for intestinal homeostasis involving autophagy-independent mechanisms through its function in endocytic trafficking. Commun. Biol. 2024, 7, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, X.; Thapa, N.; Sun, Y.; Anderson, R.A. A Kinase-Independent Role for EGF Receptor in Autophagy Initiation. Cell 2015, 160, 145–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, X.; Ma, H.; Du, Y. Role and mechanism of action of LAPTM4B in EGFR-mediated autophagy (Review). Oncol. Lett. 2022, 23, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eden, E.R.; White, I.J.; Tsapara, A.; Futter, C.E. Membrane contacts between endosomes and ER provide sites for PTP1B–epidermal growth factor receptor interaction. Nat. Cell Biol. 2010, 12, 267–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wen, T.; Thapa, N.; Cryns, V.L.; Anderson, R.A. Regulation of Phosphoinositide Signaling by Scaffolds at Cytoplasmic Membranes. Biomolecules 2023, 13, 1297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caldieri, G.; Barbieri, E.; Nappo, G.; Raimondi, A.; Bonora, M.; Conte, A.; Verhoef, L.G.G.C.; Confalonieri, S.; Malabarba, M.G.; Bianchi, F.; et al. Reticulon 3–dependent ER-PM contact sites control EGFR nonclathrin endocytosis. Science 2017, 356, 617–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, R.; Jin, R.; Wu, L.; Ye, X.; Yang, Y.; Luo, K.; Wang, W.; Wu, D.; Ye, X.; Huang, L.; et al. Reticulon 3 attenuates the clearance of cytosolic prion aggregates via inhibiting autophagy. Autophagy 2011, 7, 205–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, X.; Lee, D.-H.; Dilly, A.-K.; Lee, Y.-S.; Choudry, H.A.; Kwon, Y.T.; Bartlett, D.L.; Lee, Y.J. Crosstalk Between Apoptosis and Autophagy Is Regulated by the Arginylated BiP/Beclin-1/p62 Complex. Mol. Cancer Res. 2018, 16, 1077–1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jian, M.; Yunjia, Z.; Zhiying, D.; Yanduo, J.; Guocheng, J. Interleukin 7 receptor activates PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling pathway via downregulation of Beclin-1 in lung cancer. Mol. Carcinog. 2018, 58, 358–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Liu, L.; Ling, Y.; Zheng, J. Polypeptide LTX-315 reverses the cisplatin chemoresistance of ovarian cancer cells via regulating Beclin-1/PI3K/mTOR signaling pathway. J. Biochem. Mol. Toxicol. 2021, 35, e22853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, C.; Zhang, X.; Mo, X.; Yu, Y.; Xiao, Z.; Wu, J.; Ding, L.; Lei, C.; Zhu, Y.; Zhang, H. Xie-Bai-San increases NSCLC cells sensitivity to gefitinib by inhibiting Beclin-1 mediated autophagosome formation. Phytomedicine 2024, 125, 155351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, B.; Yang, C.; Yan, X.; Shi, Z.; Xiao, H.; Wei, X.; Jiang, N.; Wu, Z. LETM1 Knockdown Promotes Autophagy and Apoptosis Through AMP-Activated Protein Kinase Phosphorylation-Mediated Beclin-1/Bcl-2 Complex Dissociation in Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Front. Oncol. 2021, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, X. , Zhu, S., Chen, P., Hou, W., Wen, Q., Liu, J., Xie, Y., Liu, J., Klionsky, D. J., Kroemer, G., Lotze, M. T., Zeh, H. J., Kang, R., & Tang, D. (2018). AMPK-Mediated BECN1 Phosphorylation Promotes Ferroptosis by Directly Blocking System Xc- Activity. Current biology : CB, 28(15), 2388–2399.e5. [CrossRef]

- Seo, J.; Seong, D.; Nam, Y.W.; Hwang, C.H.; Lee, S.R.; Lee, C.-S.; Jin, Y.; Lee, H.-W.; Oh, D.-B.; Vandenabeele, P.; et al. Beclin 1 functions as a negative modulator of MLKL oligomerisation by integrating into the necrosome complex. Cell Death Differ. 2020, 27, 3065–3081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, H.-E.; Lin, J.-F.; Tsai, T.-F.; Lin, Y.-C.; Chou, K.-Y.; Hwang, T.I.-S. Allyl Isothiocyanate Induces Autophagy through the Up-Regulation of Beclin-1 in Human Prostate Cancer Cells. Am. J. Chin. Med. 2018, 46, 1625–1643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, M.; Wan, X.-B.; Yuan, Z.Y.; Wei, L.; Fan, X.J.; Wang, T.-T.; Lv, Y.C.; Li, X.; Chen, Z.-H.; Chen, J.; et al. Low expression of Beclin 1 and elevated expression of HIF-1α refine distant metastasis risk and predict poor prognosis of ER-positive, HER2-negative breast cancer. Med Oncol. 2013, 30, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minamoto, T.; Nakayama, K.; Nakamura, K.; Katagiri, H.; Sultana, R.; Ishibashi, T.; Ishikawa, M.; Yamashita, H.; Sanuki, K.; Iida, K.; et al. Loss of beclin 1 expression in ovarian cancer: A potential biomarker for predicting unfavorable outcomes. Oncol. Lett. 2017, 15, 1170–1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Sun, Y.; Wang, B.; Wang, H. Prognostic significance of autophagy-related genes Beclin1 and LC3 in ovarian cancer: a meta-analysis. J. Int. Med Res. 2020, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.; Li, D.-D.; Wang, L.-L.; Deng, R.; Zhu, X.-F. Decreased expression of autophagy-related proteins in malignant epithelial ovarian cancer. Autophagy 2008, 4, 1067–1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, W.; Yue, C.; Deng, J.; Hu, R.; Xu, J.; Feng, L.; Lan, Q.; Zhang, W.; Ji, D.; Wu, J.; et al. Autophagic Protein Beclin 1 Serves as an Independent Positive Prognostic Biomarker for Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. PLOS ONE 2013, 8, e80338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, H.; Chen, L.; Luo, F.; Chen, X.; Li, Y.; Cheng, Q. Beclin-1 expression is associated with prognosis in a Bcl-2-dependent manner in non-small cell lung cancer. Oncol. Lett. 2020, 20, 1–1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, L.-W.; Hou, Y.-J.H.; Tan, Y.-X.; Tang, L.; Pan, Y.-F.; Wang, M.; Wang, H.-Y. Prognostic significance of Beclin 1 in intrahepatic cholangiocellular carcinoma. Autophagy 2011, 7, 1222–1229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.-T.; Cao, Q.-H.; Chen, M.-Y.; Xia, Q.; Fan, X.-J.; Ma, X.-K.; Lin, Q.; Jia, C.-C.; Dong, M.; Ruan, D.-Y.; et al. Beclin 1 Deficiency Correlated with Lymph Node Metastasis, Predicts a Distinct Outcome in Intrahepatic and Extrahepatic Cholangiocarcinoma. PLOS ONE 2013, 8, e80317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, H.-C.; Zhao, S.; Xue, H.; Zhao, E.-H.; Jiang, H.-M.; Hao, C.-L. The Roles of Beclin 1 Expression in Gastric Cancer: A Marker for Carcinogenesis, Aggressive Behaviors and Favorable Prognosis, and a Target of Gene Therapy. Front. Oncol. 2020, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Yang, M.; Zhao, B. Beclin 1 and LC3 as predictive biomarkers for metastatic colorectal carcinoma. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 59058–59067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, L.; Ma, B.; Liang, Y.; Liu, H.; Zheng, G.; Zhang, T.; Chu, M.; Xu, P.; Su, Y.; Liao, G. High expression of the autophagy gene Beclin-1 is associated with favorable prognosis for salivary gland adenoid cystic carcinoma. J. Oral Pathol. Med. 2012, 41, 621–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, W.-H.; Tang, F.; Xu, J.; Wu, X.; Yang, S.-B.; Feng, Z.-Y.; Ding, Y.-G.; Wan, X.-B.; Guan, Z.; Li, H.-G.; et al. Low expression of Beclin 1, associated with high Bcl-xL, predicts a malignant phenotype and poor prognosis of gastric cancer. Autophagy 2012, 8, 389–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicotra, G.; Mercalli, F.; Peracchio, C.; Castino, R.; Follo, C.; Valente, G.; Isidoro, C. Autophagy-active beclin-1 correlates with favourable clinical outcome in non-Hodgkin lymphomas. Mod. Pathol. 2010, 23, 937–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valente, G.; Morani, F.; Nicotra, G.; Fusco, N.; Peracchio, C.; Titone, R.; Alabiso, O.; Arisio, R.; Katsaros, D.; Benedetto, C.; et al. Expression and Clinical Significance of the Autophagy Proteins BECLIN 1 and LC3 in Ovarian Cancer. BioMed Res. Int. 2014, 2014, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salwa, A.; Ferraresi, A.; Secomandi, E.; Vallino, L.; Moia, R.; Patriarca, A.; Garavaglia, B.; Gaidano, G.; Isidoro, C. High BECN1 Expression Negatively Correlates with BCL2 Expression and Predicts Better Prognosis in Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma: Role of Autophagy. Cells 2023, 12, 1924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giatromanolaki, A.; Koukourakis, M.I.; Koutsopoulos, A.; Chloropoulou, P.; Liberis, V.; Sivridis, E. High Beclin 1 expression defines a poor prognosis in endometrial adenocarcinomas. Gynecol. Oncol. 2011, 123, 147–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- I Koukourakis, M.; Giatromanolaki, A.; Sivridis, E.; Pitiakoudis, M.; Gatter, K.C.; Harris, A.L. Beclin 1 over- and underexpression in colorectal cancer: distinct patterns relate to prognosis and tumour hypoxia. Br. J. Cancer 2010, 103, 1209–1214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, J.M.; Huang, S.; Wu, T.-T.; Foster, N.R.; Sinicrope, F.A. Prognostic impact of Beclin 1, p62/sequestosome 1 and LC3 protein expression in colon carcinomas from patients receiving 5-fluorouracil as adjuvant chemotherapy. Cancer Biol. Ther. 2013, 14, 100–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salwa, A.; Ferraresi, A.; Vallino, L.; Maheshwari, C.; Moia, R.; Gaidano, G.; Isidoro, C. High Mitophagy and Low Glycolysis Predict Better Clinical Outcomes in Acute Myeloid Leukemias. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 11527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thongchot, S.; Ferraresi, A.; Vidoni, C.; Salwa, A.; Vallino, L.; Kittirat, Y.; Loilome, W.; Namwat, N.; Isidoro, C. Preclinical evidence for preventive and curative effects of resveratrol on xenograft cholangiocarcinogenesis. Cancer Lett. 2023, 582, 216589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El Shayeb, A.; Deghedy, A.; Bedewy, E.S.; Badawy, S.; Abdeen, N. Serum Beclin 1 and autophagy-related protein-5 and the risk of hepatocellular carcinoma among cirrhotic hepatitis C patients. Egypt. Liver J. 2021, 11, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Y.-Z.; Liang, Q.; Tomchick, D.R.; De Brabander, J.K.; Rizo, J. Structural insights for selective disruption of Beclin 1 binding to Bcl-2. Commun. Biol. 2023, 6, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, P.; He, L.; Xing, C.; Mao, J.; Yu, X.; Zhu, M.; Diao, L.; Han, L.; Zhou, Y.; You, J.M.; et al. Myeloid loss of Beclin 1 promotes PD-L1hi precursor B cell lymphoma development. J. Clin. Investig. 2019, 129, 5261–5277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noman, M.Z.; Berchem, G.; Janji, B. Targeting autophagy blocks melanoma growth by bringing natural killer cells to the tumor battlefield. Autophagy 2018, 14, 730–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, M.J.; Park, S.; Won, K.Y. Expression of Beclin-1, an autophagy-related protein, is associated with tumoral FOXP3 expression and Tregs in gastric adenocarcinoma: The function of Beclin-1 expression as a favorable prognostic factor in gastric adenocarcinoma. Pathol. - Res. Pr. 2020, 216, 152927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akhtar, A.; Shakir; Ansari, M. S.; Divya; Faizan, I.; Chauhan, V.; Singh, A.; Alam, R.; Azmi, I.; Sharma, S.; et al. Bioengineering the metabolic network of CAR T cells with GLP-1 and Urolithin A increases persistence and long-term anti-tumor activity. Cell Rep. Med. 2025, 6, 102021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vega-Rubin-de-Celis, S.; Zou, Z.; Fernandez, A.F.; Ci, B.; Kim, M.; Xiao, G.; Xie, Y.; Levine, B. Increased autophagy blocks HER2-mediated breast tumorigenesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2018, 115, 4176–4181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kona, S.V.; Kalivendi, S.V. The USP10/13 inhibitor, spautin-1, attenuates the progression of glioblastoma by independently regulating RAF-ERK mediated glycolysis and SKP2. Biochim. et Biophys. Acta (BBA) - Mol. Basis Dis. 2024, 1870, 167291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.-C.; Zhao, C.-J.; Jin, Z.-F.; Zheng, J.; Ma, L.-T. Targeted therapy based on ubiquitin-specific proteases, signalling pathways and E3 ligases in non-small-cell lung cancer. Front. Oncol. 2023, 13, 1120828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maiuri, M.C.; Criollo, A.; Tasdemir, E.; Vicencio, J.M.; Tajeddine, N.; Hickman, J.A.; Geneste, O.; Kroemer, G. BH3-Only Proteins and BH3 Mimetics Induce Autophagy by Competitively Disrupting the Interaction between Beclin 1 and Bcl-2/Bcl-XL. Autophagy 2007, 3, 374–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maiuri, M.C.; Le Toumelin, G.; Criollo, A.; Rain, J.-C.; Gautier, F.; Juin, P.; Tasdemir, E.; Pierron, G.; Troulinaki, K.; Tavernarakis, N.; et al. Functional and physical interaction between Bcl-XL and a BH3-like domain in Beclin-1. EMBO J. 2007, 26, 2527–2539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oltersdorf, T.; Elmore, S.W.; Shoemaker, A.R.; Armstrong, R.C.; Augeri, D.J.; Belli, B.A.; Bruncko, M.; Deckwerth, T.L.; Dinges, J.; Hajduk, P.J.; et al. An inhibitor of Bcl-2 family proteins induces regression of solid tumours. Nature 2005, 435, 677–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yao, X.; Li, X.; Zhang, D.; Xie, Y.; Sun, B.; Li, H.; Sun, L.; Zhang, X. B-cell lymphoma 2 inhibitor ABT-737 induces Beclin1- and reactive oxygen species-dependent autophagy in Adriamycin-resistant human hepatocellular carcinoma cells. Tumor Biol. 2017, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, N.; Zhang, X.; Chen, J.; Gao, S.; Wang, L.; Zhao, Y. Perturbation of Autophagy by a Beclin 1-Targeting Stapled Peptide Induces Mitochondria Stress and Inhibits Proliferation of Pancreatic Cancer Cells. Cancers 2023, 15, 953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Yue, C.; Chen, H.; Chen, Y.; Li, G. Metformin Promotes Beclin1-Dependent Autophagy to Inhibit the Progression of Gastric Cancer. OncoTargets Ther. 2020, ume 13, 4445–4455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, H.; Tai, X.-J.; Cheng, W.; Wu, Y.; He, D.; Wang, L.-F.; Liu, H.; Zhang, S.-Y.; Sun, Y.-T.; Liu, H.-Z.; et al. Metformin inhibits the growth of SCLC cells by inducing autophagy and apoptosis via the suppression of EGFR and AKT signalling. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, A.; Chai, P.; Wang, S.; Zuo, S.; Yu, J.; Jia, S.; Ge, S.; Jia, R.; Zhou, Y.; Shi, W.; et al. Metformin promotes histone deacetylation of optineurin and suppresses tumour growth through autophagy inhibition in ocular melanoma. Clin. Transl. Med. 2022, 12, e660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Lin, C.; Lu, C.; Wang, Y.; Han, R.; Li, L.; Hao, S.; He, Y. Metformin-sensitized NSCLC cells to osimertinib via AMPK-dependent autophagy inhibition. Clin. Respir. J. 2019, 13, 781–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, C.; Wei, Y.; Sun, K.; Li, B.; Dong, X.; Zou, Z.; Liu, Y.; Kinch, L.N.; Khan, S.; Sinha, S.; et al. Beclin 2 Functions in Autophagy, Degradation of G Protein-Coupled Receptors, and Metabolism. Cell 2013, 154, 1085–1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, C.; Wei, Y.; Sun, K.; Li, B.; Dong, X.; Zou, Z.; Liu, Y.; Kinch, L.N.; Khan, S.; Sinha, S.; et al. Beclin 2 Functions in Autophagy, Degradation of G Protein-Coupled Receptors, and Metabolism. Cell 2013, 154, 1085–1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yue, Z.; Jin, S.; Yang, C.; Levine, A.J.; Heintz, N. Beclin 1, an autophagy gene essential for early embryonic development, is a haploinsufficient tumor suppressor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2003, 100, 15077–15082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, M.; Deng, G.; Tan, P.; Xing, C.; Guan, C.; Jiang, C.; Zhang, Y.; Ning, B.; Li, C.; Yin, B.; et al. Beclin 2 negatively regulates innate immune signaling and tumor development. J. Clin. Investig. 2020, 130, 5349–5369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, G.; Li, C.; Chen, L.; Xing, C.; Fu, C.; Qian, C.; Liu, X.; Wang, H.Y.; Zhu, M.; Wang, R.-F. BECN2 (beclin 2) Negatively Regulates Inflammasome Sensors Through ATG9A-Dependent but ATG16L1- and LC3-Independent Non-Canonical Autophagy. Autophagy 2021, 18, 340–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quiles, J.M.; Najor, R.H.; Gonzalez, E.; Jeung, M.; Liang, W.; Burbach, S.M.; Zumaya, E.A.; Diao, R.Y.; Lampert, M.A.; Gustafsson, Å.B. Deciphering functional roles and interplay between Beclin1 and Beclin2 in autophagosome formation and mitophagy. Sci. Signal. 2023, 16, eabo4457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, M.; Li, Y.; Wyborny, S.; Neau, D.; Chakravarthy, S.; Levine, B.; Colbert, C.L.; Sinha, S.C. BECN2 interacts with ATG14 through a metastable coiled-coil to mediate autophagy. Protein Sci. 2017, 26, 972–984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).