1. Introduction

1.1. Problem Statement

Human Action Recognition (HAR) has undergone a significant paradigm shift, evolving from early methods based on handcrafted features to deep learning models capable of learning hierarchical representations directly from data [

1,

2,

3]. More recent methods leverage deep architectures and hybrid models for spatiotemporal representation learning. For instance, deeper two-stream architectures were developed to integrate spatial and temporal cues better, achieving improved performance in surveillance video settings [

4], and refined spatiotemporal fusion strategies have further enhanced feature integration [

5]. Additionally, hybrid models combining Conv-RBM with LSTM and optimized frame selection have demonstrated the flexibility and effectiveness of temporal modeling techniques in HAR [

6]. Recent work demonstrated that augmenting 3D skeleton inputs with spatial–temporal transformations significantly improves HAR robustness and model generalization [

7]. 3D Convolutional Neural Networks (3D-CNNs) such as the Inflated 3D ConvNet (I3D) [

8] and factorized variants like R(2+1)D [

9] set the standard by extending the success of 2D-CNNs into the temporal domain. More recently, Vision Transformers (ViT) have revolutionized the field, with models like VideoMAE [

10] demonstrating that a self-supervised pre-training objective of masked autoencoding can produce powerful, data-efficient learners for video.

Despite these advances, a fundamental "modality gap" persists. Models relying solely on RGB video excel at capturing appearance, texture, and scene context but can be confounded by actions with subtle motion or those performed by individuals with similar appearances. For example, distinguishing "jogging" from "running" may depend more on the cadence and extension of limbs than on the person's visual appearance or background. Conversely, skeletal pose data, which represents the body's kinematics as a set of keypoint coordinates, offers an explicit, viewpoint-invariant representation of motion but lacks the rich contextual information present in RGB frames [

11]. This suggests that the optimal approach lies in the effective fusion of these complementary modalities.

This realization has spurred a recent wave of research into pose-guided action recognition. Methods such as Baradel et al. 2018’s Pose-driven Attention for RGB [

12] and Song et al. 2020’s Modality Compensation Network [

13] leverage pose information to guide a model’s attention toward semantically salient spatiotemporal regions, thereby improving performance on fine-grained and complex action categories. Building on this momentum, our work addresses the critical challenge of best fusing appearance and pose information within a modern Transformer architecture while maintaining computational efficiency. The core of our work is not just the development of a new model, but a demonstration of a compositional methodology: we leverage powerful, off-the-shelf foundation models-VideoMAE for appearance, RT-DETR for person detection [

14], and ViTPose++ for pose estimation[

15]-and focus our innovation on the crucial fusion and efficiency-enhancing layers that connect them. This pragmatic approach reflects a modern research paradigm that intelligently combines existing capabilities to solve new challenges.

This paper presents TransMODAL, a dual-stream architecture designed for effective and efficient pose-guided human action recognition. Our primary contributions are twofold:

A Novel Dual-Stream Architecture (TransMODAL): We propose a compositional, end-to-end trainable model that synergistically fuses two powerful and complementary data streams. The first stream leverages a pre-trained VideoMAE backbone to extract rich, contextual appearance features from RGB video. The second, a dedicated PoseEncoder stream, processes explicit kinematic information from a sequence of 2D skeletal keypoints. This pose data is generated via a state-of-the-art pre-processing pipeline composed of the RT-DETR model for robust person detection and the ViTPose++ model for accurate keypoint estimation. By integrating these specialized foundation models, our architecture focuses its innovation directly on the crucial task of multi-modal fusion.

Adaptive Multi-Modal Fusion and Pruning: We introduce two novel modules that form the technical core of our architecture. The first, CoAttentionFusion, facilitates a deep, iterative dialogue between the two data streams. Through a symmetric cross-attention mechanism, the appearance stream queries the pose stream for kinematic context, while the pose stream simultaneously queries the appearance stream for visual evidence. This allows each modality to enrich its representation with context from the other. The second module, AdaptiveSelector, addresses the challenge of computational efficiency inherent in Transformer models. It is a lightweight module with a learnable scoring mechanism that intelligently identifies and prunes redundant spatiotemporal tokens from the fused representation. This significantly reduces computational overhead and inference latency without compromising classification accuracy.

2. Related Work

Our work is situated at the confluence of three major trends in video understanding: spatiotemporal convolutional networks, Transformer-based video models, and pose-guided recognition systems.

2.1. Spatiotemporal Convolutions for Action Recognition

Spatial–temporal fusion networks combining TSN and Bi-LSTM have been effectively used for HAR in dynamic rescue scenarios [

16]. For several years, 3D-CNNs were the dominant architecture for HAR. A seminal work in this area is the Inflated 3D ConvNet (I3D) by Carreira and Zisserman 2017, which “inflates” 2D filters into 3D to process video volumes and bootstraps weights from ImageNet [

8]. This work also introduced the large-scale Kinetics dataset, quickly becoming the de facto standard for pre-training action recognition models [

17]. I3D achieved state-of-the-art performance on benchmarks like UCF-101 with Kinetics pre-training, reaching 97.9% Top-1 accuracy [

8]. Building on the success of I3D but aiming for greater computational efficiency, Tran et al. 2018 proposed R(2+1)D, which factorizes spatiotemporal convolutions. Instead of a full 3D convolution (e.g., with a kernel of size

t×k×k), R(2+1)D performs a 2D spatial convolution (kernel 1×k×k) followed by a 1D temporal convolution (kernel

t×1×1). This decomposition has two main benefits: it increases the number of nonlinearities for a fixed number of parameters, enhances representational capacity, and simplifies optimization. R(2+1)D also established strong baseline performance, achieving 97.3% Top-1 accuracy on UCF-101 with Kinetics pre-training. These CNN-based models represent the established "old guard" against which new architectures are often measured [

9].

2.2. Transformer-Based Video Understanding

More recently, Transformer architectures have emerged as the new state of the art. Our model's appearance stream is built directly upon VideoMAE (Masked Autoencoders for Video) [

10]. Inspired by its counterpart in natural language processing (BERT) and image processing (MAE), VideoMAE is pre-trained using a self-supervised objective: a very high percentage (e.g., 90-95%) of spatiotemporal patches in a video are masked, and the model must reconstruct the missing pixels [

10]. A key finding of the VideoMAE work is that these models are remarkably data-efficient learners; they can achieve high performance on downstream tasks even when pre-trained on relatively small datasets (a few thousand videos) without any external supervised data. This property makes VideoMAE an ideal backbone for our work, providing powerful generic features that can be effectively adapted. The original VideoMAE paper reported strong results of 91.3% on UCF101 and 62.6% on HMDB51 without extra data [

10]. Other influential video transformers, such as TimeSformer by Bertasius et al. 2021 [

18] and ViViT by Arnab et al. 2021 [

19], have also demonstrated the power of attention mechanisms for modeling long-range spatiotemporal dependencies in video.

2.3. Pose-Guided Action Recognition

The third critical area of related work involves leveraging human pose to improve action recognition. The rationale is that pose provides a compact, high-level representation of human motion robust to variations in clothing, background clutter, and viewpoint [

20]. AutoML-based skeleton pipelines have shown promise, such as ‘single-path one-shot’ neural architecture search optimized for depth-camera data [

21]. While early works explored fusing pose with CNN features, recent efforts have focused on integrating pose within Transformer frameworks, an active and promising research direction. For instance, the Pose-Guided Video Transformer (PGVT) uses 2D body joint coordinates to explicitly guide the spatial attention mechanism of a vision transformer, forcing the model to focus on pose-relevant appearance features [

22]. Other approaches have explored multi-task learning, where action and pose are predicted simultaneously [

23], or have used pose features as positional embedding for video tokens [

24].

Our work contributes to this burgeoning area by proposing CoAttentionFusion, a novel and symmetric mechanism for iterative feature exchange between modalities, distinguishing it from prior fusion strategies. TransMODAL thus sits at the intersection of these three research thrusts: it leverages the powerful representations of VideoMAE, incorporates the efficiency lessons from models like R(2+1)D (via our AdaptiveSelector), and introduces a new fusion technique to the field of pose-guided recognition.

3. The TransMODAL Architecture

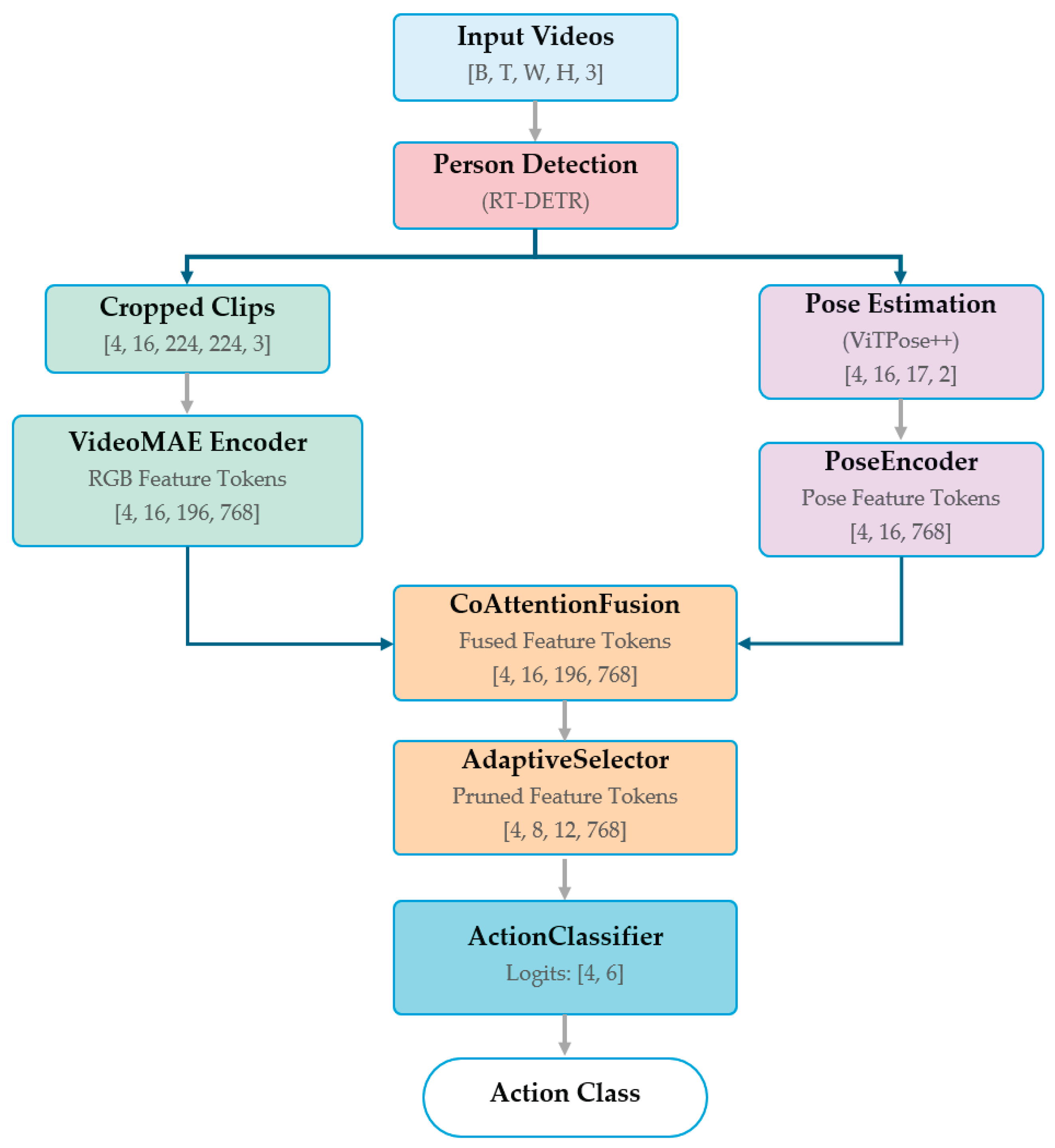

The TransMODAL architecture is a dual-stream network that processes and fuses RGB video and 2D pose sequences for robust action recognition. The overall pipeline, depicted in

Figure 1, is a multi-stage process that leverages pre-trained models for initial feature extraction and introduces novel modules for efficient fusion and classification. Bracketed numbers denote the tensor dimensions at each stage, following the format [B: Batch=4, T: Time (clip_length=16), H: Height=224, W: Width=224, N: Tokens=196, K: Keypoints=(17, 2), D: Dimension=768]. The process begins with person detection and pose estimation to generate two parallel input streams. The RGB stream, consisting of person-centric video clips, is encoded by a frozen VideoMAE backbone [

10]. The pose stream, a sequence of 2D skeletal coordinates, is processed by our lightweight PoseEncoder [

20]. The core of our contribution lies in the subsequent stages, where the two feature streams are deeply fused by the CoAttentionFusion module, intelligently pruned by the AdaptiveSelector [

25], and finally passed to a linear classifier to predict the action [

8,

9]. The following subsections detail each of these components.

3.2. Input Modalities and Encoders

3.2.1. RGB Appearance Stream

The primary visual feature extractor is a pre-trained VideoMAE model (MCG-NJU/videomae-base-finetuned-kinetics) with a Vision Transformer (ViT-Base) architecture. The model processes input clips of clip_len=16 frames. The ViT backbone, with an embedding dimension of D=768, converts the video clip into a sequence of spatiotemporal patch embeddings. The parameters of this backbone are frozen during training to leverage its powerful, pre-learned features and to maintain training efficiency.

3.2.2. Pose Kinematics Stream (PoseEncoder)

This stream processes the explicit skeletal information. The input of PoseEncoder is a tensor

, where

B=4 is the batch size,

T=16 is the clip length,

J=17 is the number of joints, and 2 corresponds to the

coordinates of each joint. The PoseEncoder is a simple yet effective module designed to embed this coordinate sequence into the same feature space as the RGB stream. For each frame

t, the joint coordinates

are flattened into a vector

. This vector is projected into the embedding space via a linear layer as 1:

where

and

are learnable weights and biases. The sequence of frame embeddings is then augmented with learnable temporal position embeddings

before being processed by a single Transformer Encoder layer to capture temporal dynamics. The final output is a sequence of pose tokens

.

3.3. Core Fusion and Selection Modules

The primary innovations of TransMODAL lie in how it fuses the two modalities and maintains computational efficiency.

3.3.1. Co-Attention Fusion:

This module performs deep, iterative cross-modal feature exchange. Unlike simple concatenation or late fusion, CoAttentionFusion allows the RGB and pose representations to inform and refine one another mutually. Given the sequence of RGB tokens and pose tokens , where N is the number of tokens and D is the embedding dimension. The module performs two parallel cross-attention operations.

To update the pose features, the queries (

) are derived from

, while the keys (

) and values (

) are derived from

. This allows the pose stream to "

query" the appearance stream for relevant visual context. The updated pose features,

, which is computed as (2):

where

,

,

are learnable projection matrices and

is the dimension of the keys. Concurrently, a symmetric operation is performed where the RGB stream queries the pose stream (

) to focus on kinematically relevant appearance features. This entire block of dual cross-attention, followed by feed-forward networks and residual connections, can be stacked multiple times to facilitate deeper fusion.

3.3.2. Adaptive Feature Selector (AdaptiveSelector):

To mitigate the quadratic complexity of subsequent self-attention layers, the AdaptiveSelector module dynamically prunes the fused feature tokens. This module employs a lightweight, learnable scoring mechanism to operate in two stages:

It then retains only the top_k_tokens=12 with the highest scores from each frame. This process reduces the number of tokens passed to the final classifier from to a fixed size of , significantly reducing computational load while retaining the most discriminative features.

3.4. Implementation and Complexity

The architectural specifics and computational characteristics of the trainable components of TransMODAL are summarized in

Table 1. The VideoMAE backbone parameters are frozen and thus do not contribute to the trainable parameter count.

4. Experimental Evaluation

We conducted a series of experiments to validate the effectiveness of the TransMODAL architecture, compare its performance against relevant baselines, and analyze the contribution of its core components through ablation studies.

4.1. Datasets and Protocol

Our primary evaluation benchmark is the KTH Action Recognition Dataset [

28]. It contains 600 video clips across six action classes: boxing, handclapping, handwaving, jogging, running, and walking. These actions are performed by 25 subjects in four distinct scenarios. The videos are recorded at 25 fps. Following standard protocol, we split the dataset by subject, using subjects 1-16 for training, 17 for validation, and 18-25 for testing [

28]. To test generalization, we use the UCF-101 dataset [

29]. This is a more challenging "in-the-wild" dataset collected from YouTube, comprising 13,320 videos across 101 action classes, also at 25 fps. We also evaluated the HMDB51 dataset [

30], which consists of 6,766 clips from 51 action categories, sourced primarily from movies and web videos. It is known for its challenging camera motion and lower video quality, making it a robust test of model performance.

4.2. Implementation Details

The proposed model was implemented using the PyTorch deep learning framework. The experiments were conducted in a high-performance computing environment featuring two NVIDIA Tesla T4 GPUs, each equipped with 15,360 MiB of memory and running on CUDA version 12.2. The system was optimized for deep learning tasks, ensuring efficient GPU memory utilization, with both GPUs initialized with 0 MiB memory usage. This setup provided the computational resources required for training and inference on large-scale video datasets in a reasonable timeframe. We used the AdamW optimizer (torch.optim.AdamW) with a base learning rate of 1×10

−4 and a weight decay 0.05 [

31]. A cosine annealing schedule (torch.optim.lr_scheduler.CosineAnnealingLR) was used to decay the learning rate (SGDR: Stochastic Gradient Descent with Warm Restarts [

32]) over the course of training. Models were trained for 100 epochs with a batch size of 4. For data processing, input videos were uniformly sampled to form clips of 16 frames (

clip_len=16) with a sampling stride of 2 (

frame_rate=2), ensuring consistent temporal coverage across all samples.

4.3. Main Results and Baselines

We compare TransMODAL against established CNN-based, Transformer-based, and hybrid models. To demonstrate the generalizability of our approach, we report results across all three datasets.

Table 2 shows our results on KTH, while

Table 3 and

Table 4 provide a comparative analysis against state-of-the-art methods on UCF101 and HMDB51, respectively.

The results on KTH clearly demonstrate the value of the proposed dual-modal fusion. Our full TransMODAL model achieves a Top-1 accuracy of 98.5%, which is a significant improvement of 1.7 percentage points over the strong unimodal baseline (TransMODAL - No Pose). This confirms that explicitly modeling skeletal kinematics provides complementary information that is crucial for disambiguating actions on this dataset. To further validate our method's effectiveness, we evaluated it on the more diverse UCF101 and HMDB51 datasets, achieving strong Top-1 accuracies of 96.9% and 84.2% (

Table 4), respectively.

4.4. Ablation Studies

To dissect the architecture and validate our design choices on our primary benchmark, we conducted a series of ablation studies on the KTH validation set. The results are summarized in

Table 5.

The ablation results yield several key findings:

Pose is Critical: Removing the pose stream entirely (Row 1) causes the largest drop in accuracy (-1.7%), confirming it as the most impactful component for performance.

AdaptiveSelector is Efficient: Removing the AdaptiveSelector (Row 2) results in a marginal 0.3% drop in accuracy but increases latency by over 46% (from 35.2 ms to 51.5 ms). This demonstrates that our token pruning strategy is highly effective at reducing computational cost with a negligible impact on performance.

top_k_frames Sensitivity: Varying top_k_frames shows a clear trade-off. Reducing it to 4 (Row 3) harms accuracy, suggesting that important temporal information is lost. Increasing it to 12 (Row 4) provides no significant benefit over our default of 8, validating our hyperparameter choice.

4.5. Qualitative Analysis

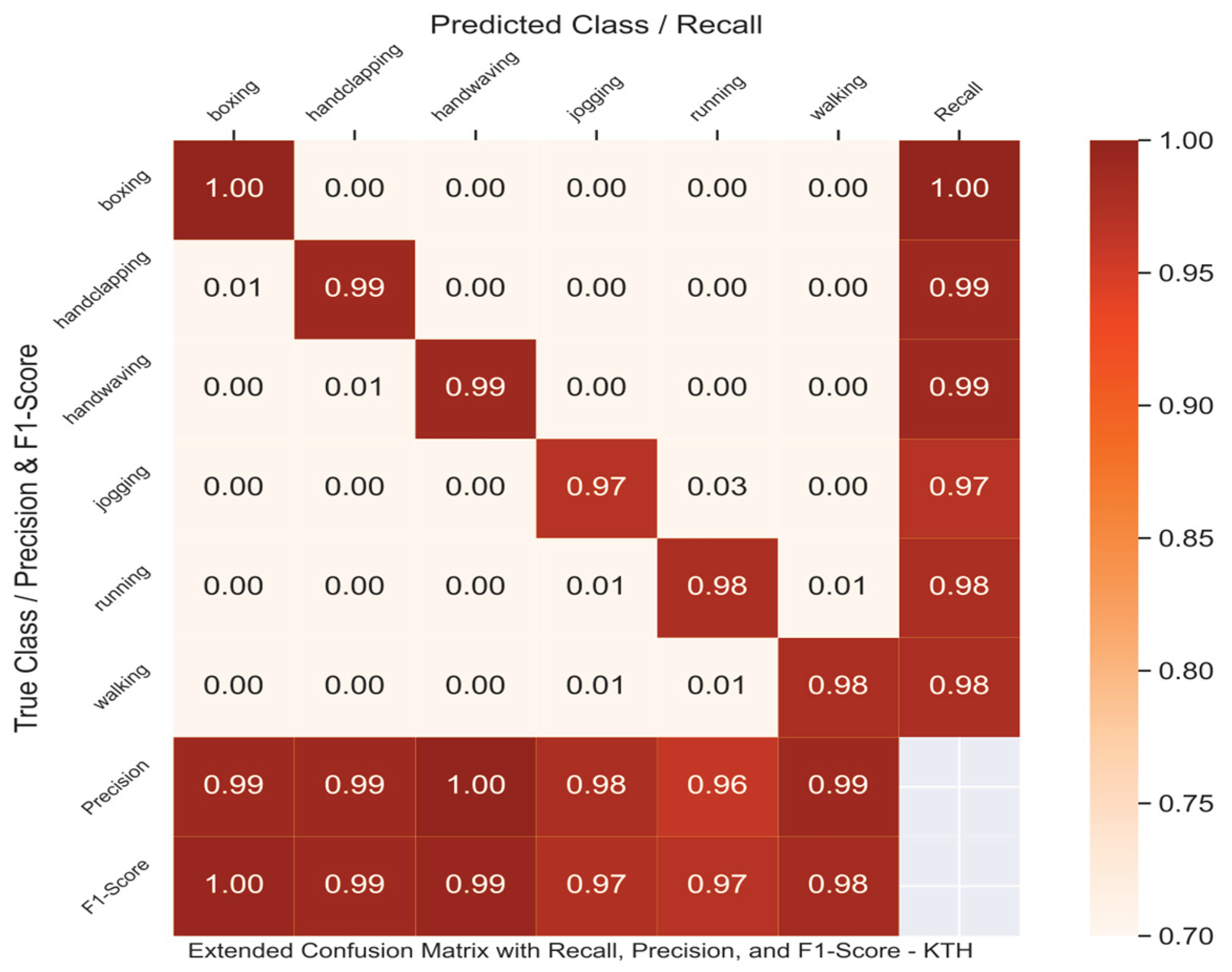

To gain a deeper, qualitative understanding of the model's behavior, we analyzed its predictions and failure modes. The confusion matrix in

Figure 2 shows excellent performance and high discriminative power for the TransMODAL model on the KTH test set, achieving an overall accuracy of 98.50%. The matrix is strongly diagonal, indicating that the vast majority of samples for each class are correctly classified. Classes with highly distinct motion patterns, such as boxing, handclapping, and handwaving, are recognized with near-perfect precision (1.00, 0.99, and 0.99) and recall (1.00, 0.99, and 0.99). The most frequent confusion, as is common for this dataset, occurs between jogging and running due to their high visual and kinematic similarity. Even so, the model effectively distinguishes them, misclassifying only 3% of jogging instances as running and maintaining high F1-scores for both classes (0.97 and 0.97). This demonstrates that even when actions lie on a motion continuum, the dual-modal fusion of appearance and explicit pose data provides sufficient information for robust classification.

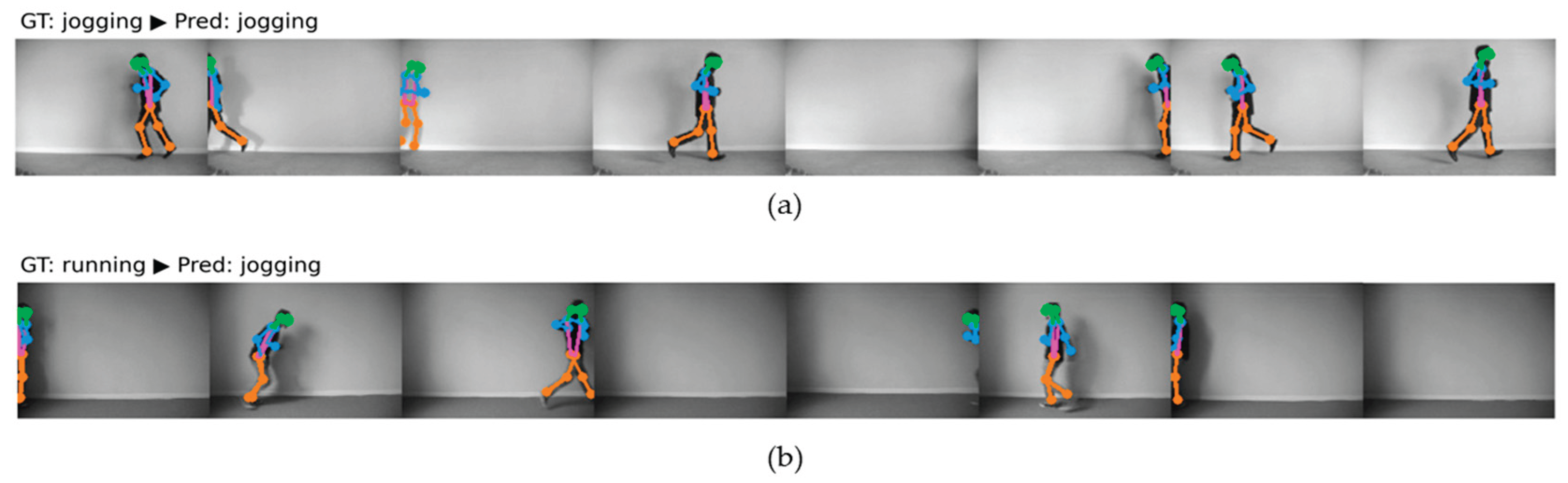

To further investigate the model's behavior, particularly concerning the confusion between kinematically similar actions, we provide qualitative examples from the KTH test set in

Figure 3. The top panel (a) shows a sequence correctly classified as "jogging." In this example, the ViTPose++ pipeline produces a clean and consistent pose track, where the gait and limb movements are clearly defined. This stable pose sequence provides a strong, unambiguous signal to the PoseEncoder, allowing the model to make a confident and accurate prediction. Conversely, the bottom panel (b) illustrates a common failure case where a "running" sequence is misclassified as "jogging." While the actions are visually similar, the pose estimations in this clip appear less stable, especially in the later frames where motion blur is more pronounced. The slight degradation in keypoint accuracy, combined with the inherent kinematic similarity between a slow run and a fast jog, likely introduces enough ambiguity for the model to err on the side of the more common "jogging" class. This highlights the model's sensitivity to the quality of the upstream pose estimation and underscores the challenge of distinguishing actions that lie on a motion continuum.

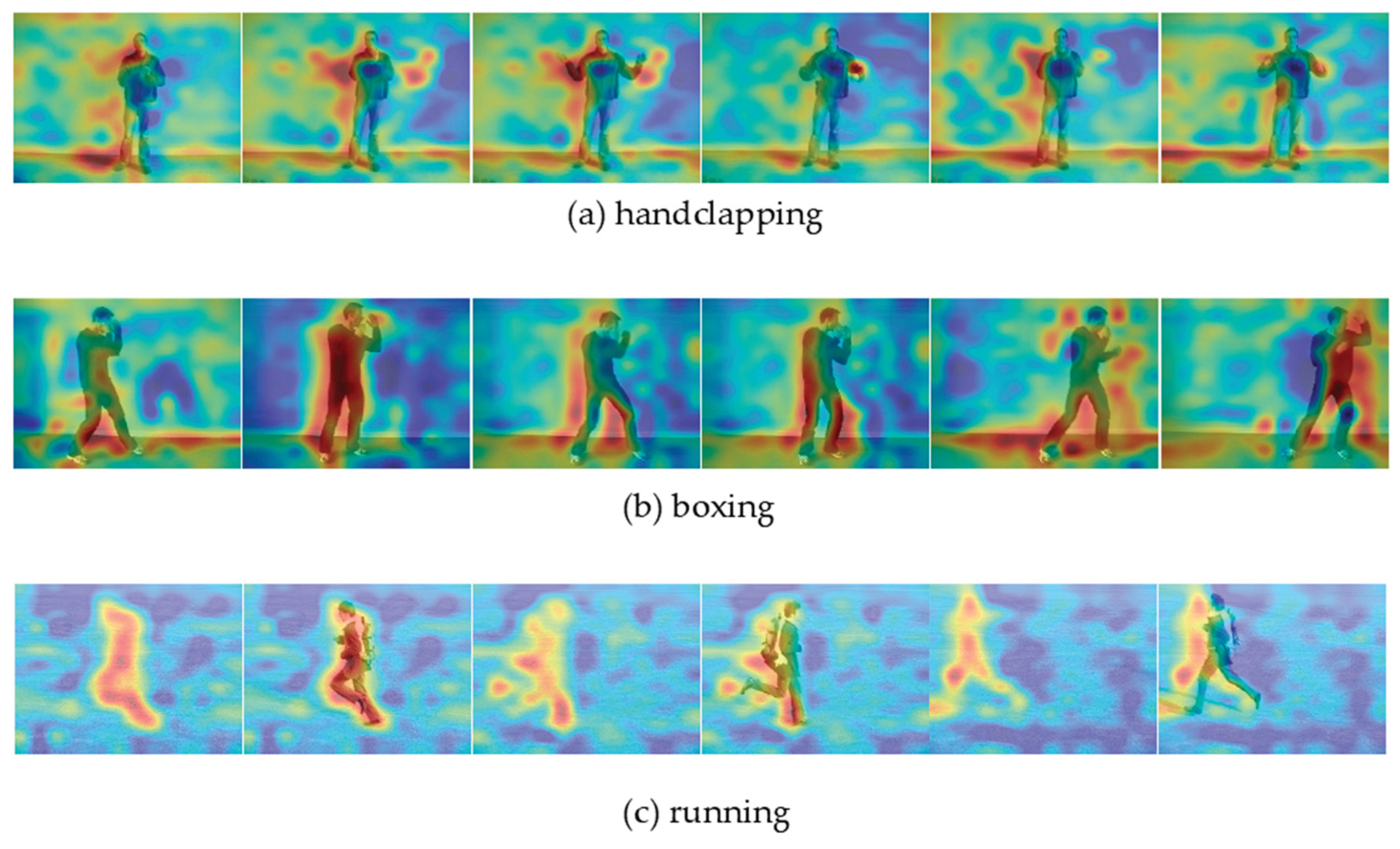

To further probe the model's internal reasoning and identify which spatiotemporal regions contribute most to its predictions, we visualized attention heatmaps for several action classes. As shown in

Figure 4, these visualizations reveal that TransMODAL has successfully learned to focus on semantically relevant body parts and track their motion over time. For "handclapping" (a), the model's attention is consistently concentrated on the hands and upper torso, correctly identifying the area of action. In the "boxing" sequence (b), the heatmaps highlight the upper body, with the most intense focus tracking the fists and arms as they perform the punching motion. For the full-body action of "running" (c), the model's attention is appropriately distributed across the legs and torso, capturing the dynamics of the running gait. These heatmaps provide strong evidence that the dual-modal fusion mechanism effectively guides the model to learn class-discriminative and spatiotemporally relevant features, rather than relying on spurious background correlations.

5. Analysis and Discussion

The experimental results provide strong evidence for the effectiveness of the TransMODAL architecture. The quantitative lift of 1.7% in Top-1 accuracy from adding the pose stream on KTH (

Table 2) underscores the value of multi-modal fusion. While the RGB stream captures appearance, the pose stream provides an explicit, disentangled representation of the human form's dynamics, which is critical for distinguishing kinematically similar actions like "jogging" and "running."

The results on UCF101 and HMDB51 (

Table 3 and

Table 4) demonstrate the model's strong generalization capabilities. On UCF101, TransMODAL's 96.9% accuracy is competitive, though it does not surpass two-stream models like I3D (97.9%) that utilize computationally expensive optical flow. However, our model significantly outperforms the RGB-only VideoMAE baseline (91.3%), showing the clear benefit of pose fusion over a single modality. Most notably, on the challenging HMDB51 dataset, TransMODAL achieves a highly competitive accuracy of 84.2%. While this does not surpass the larger, state-of-the-art VideoMAE V2-g model (88.7%), it is important to note that our model significantly outperforms the standard VideoMAE baseline (62.6%) and other strong methods like PERF-Net (83.2%). This demonstrates that for datasets with high intra-class variation and potential video quality issues, the explicit structural guidance from pose is particularly beneficial, allowing a more compact model like TransMODAL to achieve performance in the same tier as much larger, state-of-the-art architectures.

The ablation study on the AdaptiveSelector module (

Table 5, Row 2) reveals a crucial insight into the trade-off between performance and efficiency. Removing the selector and processing all tokens results in a marginal

0.3% drop in accuracy (from 98.5% to 98.2%) but causes a significant 46% increase in inference latency (from 35.2 ms to 51.5 ms). This demonstrates that a large portion of the spatiotemporal tokens are redundant for the final classification task. The AdaptiveSelector's lightweight, learnable scoring mechanism provides an effective method for identifying and pruning these less informative tokens, making the model substantially more efficient with a negligible impact on its predictive power.

Our error analysis, informed by the high overall accuracy shown in the confusion matrix (

Figure 2), indicates that the model's primary challenge lies in distinguishing between actions with very similar kinematics. The qualitative example in

Figure 3 provides a clear illustration of this limitation: a "running" sequence is misclassified as "jogging." The attention heatmaps in

Figure 4(c) confirm that the model is correctly focusing on the legs and torso, which are the most discriminative regions for this action. However, the failure case in

Figure 3(b) suggests that even when the model attends to the correct body parts, severe motion blur can degrade the quality of the underlying keypoint estimates from the ViTPose++ pipeline. This introduces ambiguity, causing the model to default to the kinematically similar "jogging" class. This "garbage-in, garbage-out" phenomenon, where noisy input from an upstream module limits performance, points to the main weakness of a two-stage approach. A promising direction for future work is therefore the exploration of end-to-end trainable models, where the pose estimator is fine-tuned alongside the action recognition head to make it more robust to such real-world video artifacts.

12

6. Conclusion and Future Work

This paper introduced TransMODAL, a dual-stream Transformer architecture for human action recognition that effectively fuses RGB appearance features with skeletal pose kinematics. We demonstrated that it is possible to build a highly performant and efficient system by composing powerful pre-trained foundation models (VideoMAE, RT-DETR, ViTPose++) and focusing innovation on the fusion and efficiency layers. Our key contributions, the CoAttentionFusion and AdaptiveSelector modules, enable deep cross-modal feature exchange while dynamically pruning redundant tokens to reduce computational cost. TransMODAL demonstrates strong performance and generalization across multiple benchmarks, achieving 98.5% on KTH, 96.9% on UCF101, and a state-of-the-art 84.2% on HMDB51. These results validate our design choices and establish a new, reproducible benchmark for efficient dual-modal action recognition.

Our work opens several avenues for future research. First, while our results are strong, evaluation on even larger-scale datasets such as Kinetics-400 [

17] and Something-Something V2 [

35] is needed to test its scalability fully. Second, exploring more sophisticated fusion mechanisms-such as those that model causal relationships between pose and appearance-could yield further improvements. Third, incorporating complementary modalities (e.g., sensor-based data) may enhance robustness; for example, recent studies using smartphone accelerometer and gyroscope signals processed via ensemble learning suggest valuable insights for multimodal HAR [

36]. Finally, transitioning from the current two-stage pipeline to an end-to-end trainable system, where the pose-estimation backbone is fine-tuned jointly with the action-recognition head, could improve robustness to noisy inputs and potentially lead to a more holistic spatiotemporal representation.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.J.; methodology, M.J.; software, M.J. and M.I.; validation, M.J., M.I., and H.R.A.; formal analysis, M.J. and M.I.; investigation, M.J.; resources, M.J.; data curation, M.I.; writing-original draft preparation, M.J.; writing-review and editing, M.J. and H.R.A.; visualization, M.I.; supervision, H.R.A.; project administration, M.J.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Dong, Y.; Zhou, R.; Zhu, C.; Cao, L.; Li, X. Hierarchical activity recognition based on belief functions theory in body sensor networks. IEEE Sensors J. 2022, 22, 15211–15221. [CrossRef]

- Joudaki, M.; Ebrahimpour Komleh, H. Introducing a new architecture of deep belief networks for action recognition in videos. JMVIP. 2024, 11, 1, 43-58.

- Teng, Q.; Wang, K.; Zhang, L.; He, J. The layer-wise training convolutional neural networks using local loss for sensor-based human activity recognition. IEEE Sensors J. 2020, 20, 7265–7274. [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.; Zhang, P.; Zhuo, T.; Huang, W.; Zhang, Y. Going Deeper with Two-Stream ConvNets for Action Recognition in Video Surveillance. Pattern Recognit. Lett. 2018, 107, 83–90. [CrossRef]

- Abdelbaky, A.; Aly, S. Two-Stream Spatiotemporal Feature Fusion for Human Action Recognition. Vis. Comput. 2021, 37, 1821–1835. [CrossRef]

- Joudaki, M.; Imani, M.; Arabnia, H.R. A New Efficient Hybrid Technique for Human Action Recognition Using 2D Conv-RBM and LSTM with Optimized Frame Selection. Technologies 2025, 13, 53. [CrossRef]

- Xin, C.; Kim, S.; Cho, Y.; Park, K.S. Enhancing Human Action Recognition with 3D Skeleton Data: A Comprehensive Study of Deep Learning and Data Augmentation. Electronics 2024, 13, 747. [CrossRef]

- Carreira, J.; Zisserman, A. Quo vadis, action recognition? A new model and the Kinetics dataset. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), USA, 2017; pp. 6299–6308. [CrossRef]

- Tran, D.; Wang, H.; Torresani, L.; Ray, J.; LeCun, Y.; Paluri, M. A closer look at spatiotemporal convolutions for action recognition. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), USA, 2018; pp. 6450–6459. [CrossRef]

- Tong, Z.; Song, Y.; Wang, J.; Wang, L. VideoMAE: Masked autoencoders are data-efficient learners for self-supervised video pre-training. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2022, 35, 10078–10093.

- Sun, Z.; Ke, Q.; Rahmani, H.; Bennamoun, M.; Wang, G.; Liu, J. Human action recognition from various data modalities: A review. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2022, 45, 3200–3225. [CrossRef]

- Baradel, F.; Wolf, C.; Mille, J. Human activity recognition with pose-driven attention to RGB. In Proceedings of the 29th British Machine Vision Conference (BMVC), UK, September 2018; pp. 1–14.

- Song, S.; Liu, J.; Li, Y.; Guo, Z. Modality compensation network: Cross-modal adaptation for action recognition. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2020, 29, 3957–3969. [CrossRef]

- Carion, N.; Massa, F.; Synnaeve, G.; Usunier, N.; Kirillov, A.; Zagoruyko, S. End-to-end object detection with transformers. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV), Cham, Switzerland, August 2020; pp. 213–229. [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, Q.; Tao, D. ViTPose++: Vision transformer for generic body pose estimation. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2023, 46, 1212–1230. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Guo, Q.; Du, Z.; Wu, A. Human Action Recognition for Dynamic Scenes of Emergency Rescue Based on Spatial-Temporal Fusion Network. Electronics 2023, 12, 538. [CrossRef]

- Kay, W.; Carreira, J.; Simonyan, K.; Zhang, B.; Hillier, C.; Vijayanarasimhan, S.; Viola, F.; Green, T.; Back, T.; Natsev, P.; Suleyman, M. The Kinetics human action video dataset. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1705.06950. [CrossRef]

- Bertasius, G.; Wang, H.; Torresani, L. Is space-time attention all you need for video understanding? In Proceedings of ICML, USA, July 2021; pp. 4.

- Arnab, A.; Dehghani, M.; Heigold, G.; Sun, C.; Lučić, M.; Schmid, C. ViViT: A video vision transformer. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Canada, 2021; pp. 6836–6846. [CrossRef]

- Fang, H.-S.; Xie, S.; Tai, Y.-W.; Lu, C. RMPE: Regional multi-person pose estimation. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), USA, 2017; pp. 2334–2343. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Yu, S.; Wang, T.; Sun, Z.; Wang, S. Skeleton-Based Human Action Recognition Based on Single Path One-Shot Neural Architecture Search. Electronics 2023, 12, 3156. [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Tan, S.; Zhen, X.; Xu, S.; Zheng, F.; He, Z.; Shao, L. Deep 3D human pose estimation: A review. Comput. Vis. Image Underst. 2021, 210, 103225. [CrossRef]

- Bevilacqua, A.; MacDonald, K.; Rangarej, A.; Widjaya, V.; Caulfield, B.; Kechadi, T. Human activity recognition with convolutional neural networks. In Proceedings of ECML PKDD, Cham, Switzerland, September 2018; pp. 541–552. [CrossRef]

- Reilly, D.; Chadha, A.; Das, S. Seeing the pose in the pixels: Learning pose-aware representations in vision transformers. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2306.09331. [CrossRef]

- Rao, Y.; Zhao, W.; Liu, B.; Lu, J.; Zhou, J.; Hsieh, C.J. DynamicViT: Efficient vision transformers with dynamic token sparsification. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2021, 34, 13937–13949.

- Ahn, D.; Kim, S.; Hong, H.; Ko, B.C. STAR-Transformer: A spatio-temporal cross attention transformer for human action recognition. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Winter Conference on Applications of Computer Vision (WACV), USA, January 2023; pp. 3330–3339. [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Ho, C.M. MM-ViT: Multi-modal video transformer for compressed video action recognition. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Winter Conference on Applications of Computer Vision (WACV), USA, January 2022; pp. 1910–1921. [CrossRef]

- Schuldt, C.; Laptev, I.; Caputo, B. Recognizing human actions: A local SVM approach. In Proceedings of the 17th International Conference on Pattern Recognition (ICPR), USA, August 2004; 3, pp. 32–36. [CrossRef]

- Soomro, K.; Zamir, A.R.; Shah, M. Ucf101: A dataset of 101 human action classes from videos in the wild. arXiv 2012, arXiv:1212.0402. [CrossRef]

- Kuehne, H.; Jhuang, H.; Garrote, E.; Poggio, T.; Serre, T. HMDB: A large video database for human motion recognition. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), USA, November 2011; pp. 2556–2563. [CrossRef]

- Loshchilov, I.; Hutter, F. Decoupled weight decay regularization. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1711.05101. [CrossRef]

- Loshchilov, I.; Hutter, F. SGDR: Stochastic gradient descent with warm restarts. arXiv 2016, arXiv:1608.03983. [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Lu, Z.; Xiong, X.; Huang, J. PERF-Net: Pose empowered RGB-Flow Net. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Winter Conference on Applications of Computer Vision (WACV), USA, January 2022; pp. 513–522. [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Huang, B.; Zhao, Z.; Tong, Z.; He, Y.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Qiao, Y. VideoMAE v2: Scaling video masked autoencoders with dual masking. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), USA, 2023; pp. 14549–14560. [CrossRef]

- Goyal, R.; Ebrahimi Kahou, S.; Michalski, V.; Materzynska, J.; Westphal, S.; Kim, H.; Haenel, V.; Freund, I.; Yianilos, P.; Mueller-Freitag, M.; Hoppe, F. The “Something Something” video database for learning and evaluating visual common sense. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), USA, October 2017; pp. 5842–5850. [CrossRef]

- Tan, T.-H.; Wu, J.-Y.; Liu, S.-H.; Gochoo, M. Human Activity Recognition Using an Ensemble Learning Algorithm with Smartphone Sensor Data. Electronics 2022, 11, 322. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).