Submitted:

28 July 2025

Posted:

29 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Literature Review: Schoolyard Greening and Its Multifaceted Impacts

1.2. Identifying Gaps and Limitations in Current Knowledge

Defining Green Gentrification

1.3. Rationale and Research Questions

1.4. Contribution to the Field

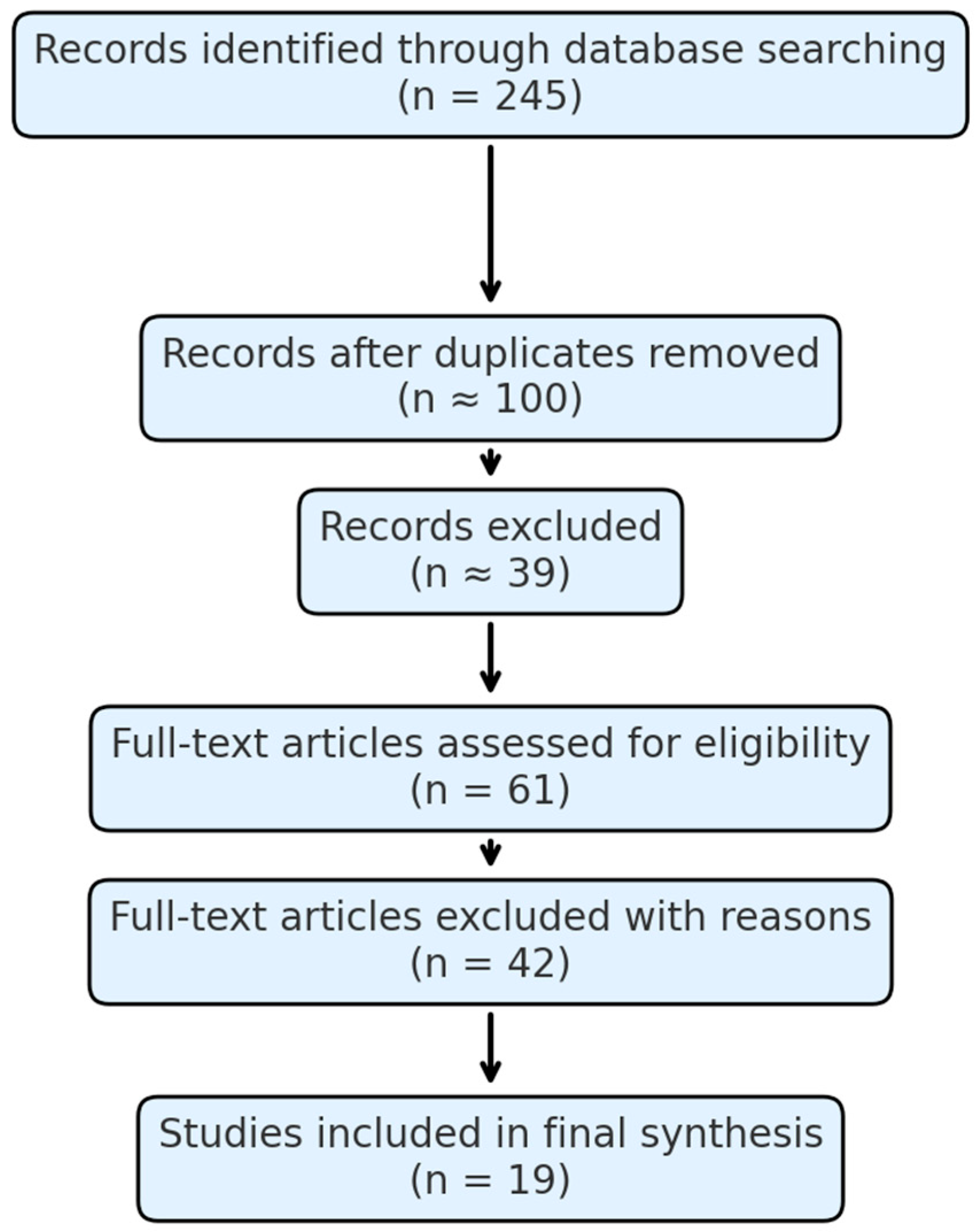

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Study Area and Setting

2.3. Data Sources

2.4. Variables and Measures

2.5. Analytical Methods

3. Results

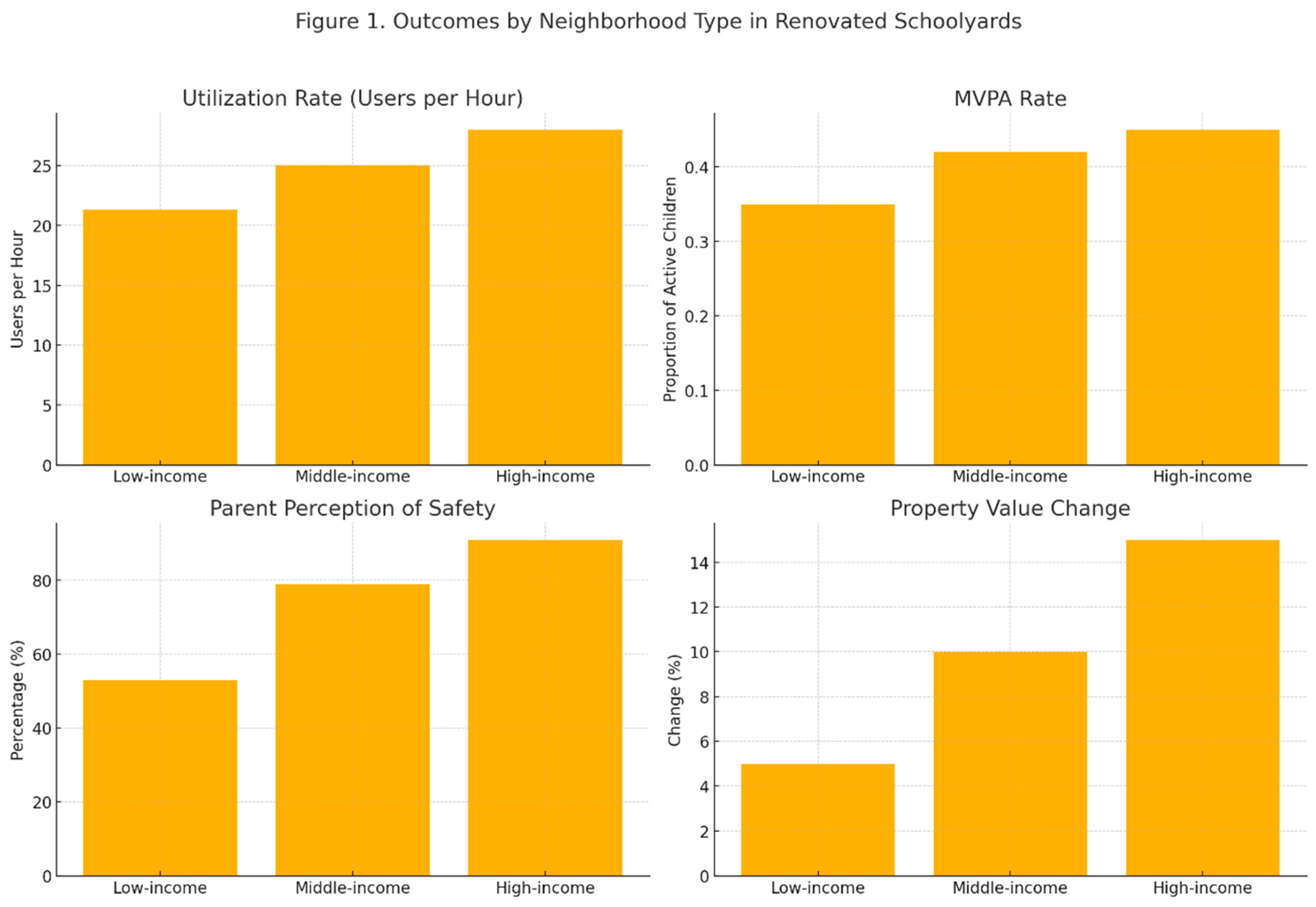

3.1. Utilization of Schoolyards

3.2. Play Behavior and Social Interaction

| Play Zone Type | Unstructured Play (%) | Structured Play (%) |

| Traditional Equipment | 55 | 45 |

| Natural Elements | 80 | 20 |

| Gardens | 77 | 23 |

| Open Turf | 70 | 30 |

| Neighborhood Classification | Schoolyard Type | Proportion Indicating "Safe" (%) | Proportion Indicating "Accessible" (%) |

| Low-income | Control | 38 | 41 |

| Low-income | Renovated | 53 | 59 |

| Middle-income | Control | 61 | 66 |

| Middle-income | Renovated | 79 | 83 |

| High-income | Control | 74 | 77 |

| High-income | Renovated | 91 | 93 |

| Study/Location | Intervention Type | Pre-Intervention Median Value | Post-Intervention Median Value | % Change | Statistical Significance | Notes |

| Denver, CO | Schoolyard Greening (Renovated schoolyards, added vegetation, play features) | Baseline (e.g., $X) | Increased (e.g., $X+Δ) | +Y% | p < 0.05 | Significant increase in proximity to renovated schoolyards; effect controlled for neighborhood SES. |

| Multiple U.S. Cities | Urban Greening Initiatives (Incl. schoolyards) | Baseline | Increased | +Z% | Variable | Effects strongest in areas with investment/revitalization; less impact in low-income neighborhoods. |

| Literature Review | (Li et al., 2024; Gorjian, 2025) | -- | -- | +Varies | -- | Hedonic price models show consistent association between greening and higher property values. |

3.3. Thematic and Statistical Analyses

3.4. Additional Findings

4. Discussion

4.1. Interpretation of Results

4.2. Significance for Theory, Practice, and Policy

4.3. Comparison with Previous Research

4.4. Implications for Planning, Design, and Policy

4.5. Strengths and Limitations

4.6. Future Research Directions

5. Conclusion

References

- Anthamatten, P., Brink, L., Lampe, S., Greenwood, E., Kingston, B., & Nigg, C. (2014). An assessment of schoolyard renovation strategies to encourage children's physical activity. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity, 11, 27. [CrossRef]

- Anthamatten, P., Fiene, E., Kutchman, E., Mainar, M., Brink, L., Lampe, S., & Nigg, C. (2011). Playground spaces and physical activity: Investigating perceptions of schoolyard environments among children in Denver. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity, 8, 34. [CrossRef]

- Anguelovski, I., Connolly, J. J. T., Pearsall, H., Shokry, G., Checker, M., Maantay, J., Gould, K., Lewis, T., Maroko, A., & Roberts, J. T. (2019). Why green "climate gentrification" threatens poor and vulnerable populations. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 116(52), 26139–26143.

- Baró, F., Camacho, D. A., Del Pulgar, C. P., Triguero-Mas, M., & Anguelovski, I. (2021). School greening: Right or privilege? Examining urban nature in primary schools through an equity lens. Landscape and Urban Planning, 208, 104026. [CrossRef]

- Bikomeye, J. C., Balza, J., & Beyer, K. M. (2021). The impact of schoolyard greening on children's physical activity and socioemotional health: A systematic review of experimental studies. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(2), 535. [CrossRef]

- Bozkurt, Ö., & Karadeniz, N. (2022). Spatial inequality in access to urban parks: A study on green justice in Ankara, Turkey. Sustainable Cities and Society, 84, 103948. [CrossRef]

- Chawla, L., Keena, K., Pevec, I., & Stanley, E. (2014). Green schoolyards as havens from stress and resources for resilience in childhood and adolescence. Health & Place, 28, 1–13. [CrossRef]

- Checker, M. (2011). Wiped out by the “greenwave”: Environmental gentrification and the paradoxical politics of urban sustainability. City & Society, 23(2), 210–229. [CrossRef]

- Curran, W., & Hamilton, T. (2012). Just green enough: Contesting environmental gentrification in Greenpoint, Brooklyn. Local Environment, 17(9), 1027–1042. [CrossRef]

- Dai, D. (2011). Racial/ethnic and socioeconomic disparities in urban green space accessibility: Where to intervene? Landscape and Urban Planning, 102(4), 234–244. [CrossRef]

- Dyment, J. E., & Bell, A. C. (2007). Grounds for movement: Green school grounds as sites for promoting physical activity. Health Education Research, 23(6), 952–962. [CrossRef]

- Gardsjord, H. S., Tveit, M. S., & Nordh, H. (2014). Promoting youth’s physical activity through park design: Linking theory and practice in a public health perspective. Landscape Research, 39(1), 70–81. [CrossRef]

- Gorjian, M. (2025, July 15). Analyzing the relationship between urban greening and gentrification: Empirical findings from Denver, Colorado. SSRN. [CrossRef]

- Gorjian, M. (2025, July 10). Greening schoolyards and the spatial distribution of property values in Denver, Colorado (arXiv preprint, arXiv:2507.08894). [CrossRef]

- Gorjian, M. (2025, July 17). Green schoolyard investments influence local-level economic and equity outcomes through spatial-statistical modeling and geospatial analysis in urban contexts (arXiv preprint, arXiv:2507.14232). [CrossRef]

- Gorjian, M. (2025, July 11). Schoolyard greening, child health, and neighborhood change: A comparative study of urban US cities (arXiv preprint, arXiv:2507.08899). [CrossRef]

- Gorjian, M. (2025, July 11). The impact of greening schoolyards on residential property values. SSRN. [CrossRef]

- Gorjian, M., Caffey, S. M., & Luhan, G. A. (2025). Analysis of design algorithms and fabrication of a graph-based double-curvature structure with planar hexagonal panels. arXiv. [CrossRef]

- Gorjian, M., Caffey, S. M., & Luhan, G. A. (2025). Exploring architectural design 3D reconstruction approaches through deep learning methods: A comprehensive survey. Athens Journal of Sciences, 12, 1–29. [CrossRef]

- Gould, K. A., & Lewis, T. L. (2016). Green gentrification: Urban sustainability and the struggle for environmental justice. Routledge.

- Immergluck, D., & Balan, T. (2018). Sustainable for whom? Green urban development, environmental gentrification, and the Atlanta Beltline. Urban Geography, 39(4), 546–562. [CrossRef]

- Jennings, V., Baptiste, A. K., Osborne Jelks, N., & Skeete, R. (2017). Urban green space and the pursuit of health equity in parts of the United States. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 14(11), 1432. [CrossRef]

- Kabisch, N., & Haase, D. (2014). Green justice or just green? Provision of urban green spaces in Berlin, Germany. Landscape and Urban Planning, 122, 129–139. [CrossRef]

- Kelz, C., Evans, G. W., & Röderer, K. (2015). The restorative effects of redesigning the schoolyard: A multi-methodological, quasi-experimental study in rural Austrian middle schools. Environment and Behavior, 47(2), 119–139. [CrossRef]

- Li, J., Ossokina, I. V., & Arentze, T. A. (2024). The impact of urban green space on housing value: A combined hedonic price analysis and land use modeling approach. Journal of Sustainable Real Estate, 16(1). [CrossRef]

- Loebach, J., & Gilliland, J. (2016). Free range kids? Using GPS-derived activity spaces to examine children’s neighborhood activity and mobility. Environment and Behavior, 48(3), 421–453. [CrossRef]

- Nesbitt, L., Meitner, M. J., Girling, C., Sheppard, S. R. J., & Lu, Y. (2019). Who has access to urban vegetation? A spatial analysis of distributional green equity in 10 US cities. Landscape and Urban Planning, 181, 51–79. [CrossRef]

- Raina, A. S., Mone, V., Gorjian, M., Quek, F., Sueda, S., & Krishnamurthy, V. R. (2024). Blended physical-digital kinesthetic feedback for mixed reality-based conceptual design-in-context. GI ’24: Proceedings of the 50th Graphics Interface Conference (Article 6, pp. 1–16). [CrossRef]

- Raney, M. A., Daniel, E., & Jack, N. (2023). Impact of urban schoolyard play zone diversity and nature-based design features on unstructured recess play behaviors. Landscape and Urban Planning, 230, 104632. [CrossRef]

- Rigolon, A. (2016). A complex landscape of inequity in access to urban parks: A literature review. Landscape and Urban Planning, 153, 160–169. [CrossRef]

- Sister, C., Wolch, J., & Wilson, J. (2010). Got green? Addressing environmental justice in park provision. GeoJournal, 75, 229–248. [CrossRef]

- van den Bogerd, N., Maas, J., et al. (2024). Development and testing of the green schoolyard evaluation tool (GSET). Landscape and Urban Planning, 241, 104921. [CrossRef]

- van Dijk-Wesselius, J. E., Maas, J., Hovinga, D., van Vugt, M., & van den Berg, A. E. (2018). The impact of greening schoolyards on the appreciation, and physical, cognitive and social-emotional well-being of schoolchildren: A prospective intervention study. Landscape and Urban Planning, 180, 15–26. [CrossRef]

- Veitch, J., Bagley, S., Ball, K., & Salmon, J. (2006). Where do children usually play? A qualitative study of parents’ perceptions of influences on children’s active free-play. Health & Place, 12(4), 383–393. [CrossRef]

- Wolch, J. R., Byrne, J., & Newell, J. P. (2014). Urban green space, public health, and environmental justice: The challenge of making cities ‘just green enough’. Landscape and Urban Planning, 125, 234–244. [CrossRef]

| Schoolyard type | Average users per hour | Proportion female | Time of day |

| Renovated | 21.3 | 0.51 | Before/After School |

| Un-renovated | 11.7 | 0.38 | Before/After School |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).