1. Introduction

Anhedonia as a core symptom of major depressive disorder (MDD) is characterized by a diminished ability to experience pleasure and a reduced responsiveness to pleasurable stimuli. It is a frequently observed active symptom during major depressive episodes [

1,

2] as well as a residual symptom after antidepressant treatment and has shown potential to serve as a predictor of treatment response and brain reward system dysfunction [

3,

4,

5]. Anhedonia also presents a barrier to psychopharmacological interventions. For example, studies indicate that current first-line antidepressant treatments, such as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), show unsatisfactory efficacy in improving difficulties associated with motivation and reward processing [

6,

7]. Recent research indicates that an atypical antidepressant, agomelatine, as an agonist at melatonergic receptors (MT1/MT2) and an antagonist at the postsynaptic serotonin receptor 5-HT2c improves anhedonia as fast as 1-3 weeks after starting treatment [

8,

9,

10,

11]. Further investigation into the neural correlates of anhedonia improvement during agomelatine treatment aids in deciphering the underlying neural mechanisms of anhedonia and further developing novel treatments for depression.

Evidence indicates that MDD patients display dysfunction in the autonomic nervous system (ANS) and may increase the risk of developing cardiovascular disease (CVD). Analysis of heart rate variability (HRV) is widely used for measuring the ANS function and understanding associations between the ANS and affective states/disorders [

12]. HRV refers to the complex beat-to-beat variation in heart rate produced by the interplay of sympathetic and parasympathetic neural activity at the sinus node of the heart. Research has shown that low HRV can predict future adverse cardiovascular events in those without known CVD history [

13]. MDD is comprised of diverse symptoms from different domains. Research indicates that specific symptoms are particularly associated with low HRV. For example, MDD with melancholic features is associated with profoundly low HRV [

14]. Research further indicates that the association between MDD and low HRV found in the literature might be driven by melancholic features [

15]. In the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5), anhedonia is further emphasized as a key item in the diagnosis of MDD with melancholic features. A study in adolescents showed that HRV was strongly associated with anhedonia symptoms [

16]. The aforementioned findings imply that HRV is a candidate used to explore neural correlates associated with anhedonia improvement with antidepressant treatment.

Our previous studies found that HRV in MDD patients was increased following 6-week agomelatine monotherapy [

17,

18]. It remains unknown whether increases or dynamic early changes in HRV are associated with anhedonia improvement following agomelatine monotherapy. In order to address the existing research gap, the present study was designed with two objectives. The primary aim was to examine whether early changes in HRV after 1-week agomelatine treatment can predict anhedonia improvement at the end of treatment. The second was to compare the differences in HRV between unmedicated patients with MDD and healthy controls (HCs) and between MDD patients following 8-week agomelatine monotherapy and HCs.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

Eighty-four unmedicated individuals diagnosed with DSM-5-defined MDD were recruited to participate in a prospective, observational, single-center cohort study where eligible patients received 8-week monotherapy with agomelatine 25 mg per day. The study received approval from the ethics committees of the Tri-Service General Hospital (No. of IRB: B202205019). Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects. The current sample overlaps with the sample mentioned in our published studies reported the data of electroencephalogram (EEG) and functional near-infrared spectroscopy (fNIRS) where the design, methodologies, and recruitment strategies have been detailed [

19,

20,

21]. The aspects relevant to the present study are detailed here. Participants did not receive any antidepressant medication treatment within the 2 weeks prior to inclusion. The inclusion criteria are: 1) patients aged between 20 and 65 years, 2) being competent to consent to participate in the study, 3) having the current major depressive episode with low suicide risk as assessed by the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI) [

22], and 4) the Montgomery Åsberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS) score > 21 on the screening day. The exclusion criteria for this study are as follows: 1) individuals with specific medical conditions, including hepatic failure (such as cirrhosis or active liver disease), any form of transaminase abnormalities, heart failure, sepsis, renal impairment, unstable hypertension, hypotension, and diabetes mellitus with poor glycemic control; 2) individuals with a history of bipolar disorder or schizophrenia-spectrum disorders; 3) individuals with an active substance use disorder, excluding caffeine and tobacco; 4) individuals diagnosed with major neurocognitive disorders, sensory impairments, epilepsy, or brain injuries; 5) individuals who are pregnant or breastfeeding; 6) individuals concurrently using potent CYP1A2 isoenzyme inhibitors (e.g., fluvoxamine, ciprofloxacin); and 7) individuals exhibiting hypersensitivity to agomelatine or its excipients. MDD participants were rated by experienced psychiatrists with the MADRS [

23] and the Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale (HARS). Anhedonia was assessed using the Chinese version of Snaith-Hamilton Pleasure Scale (SHAPS) [

24,

25]. SHAPS is a 14-item self-report questionnaire to assess the subject’s pleasure experience in the “last few days”. It is rated from definitely agree to definitely disagree on a 4-point Likert scale (i.e., scoring from 1 to 4) and the total score ranges from 14 to 56. High scores indicate more severe anhedonia. The self-reported overall severity of depression and anxiety was assessed using the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) [

26], and Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7 (GAD-7) [

27], respectively. The abovementioned clinical outcomes were measured at baseline, at weeks 1, 4, and 8 after agomelatine treatment.

The normal control (HC) group included 143 healthy participants. Recruitment and exclusion processes have been described elsewhere [

20,

28]. In summary, all healthy participants underwent a comprehensive medical evaluation, which encompassed biochemical analyses, blood pressure assessments, electrocardiograms, physical examinations, and thoracic radiographs. None of the participants exhibited any organic diseases, including but not limited to renal or hepatic disorders, cardiovascular diseases, metabolic conditions, neurological disorders, malignancies, or obesity. The participants were determined to be free of mental disorders according to evaluations conducted with the Chinese Version of the MINI [

22] by a qualified research assistant. Furthermore, it was established through self-reporting that none of the participants had been on any medications for a minimum of one month prior to their enrollment in the study. The severity of depression and anxiety among the healthy subjects was evaluated using the BDI-II and the BAI.

2.2. Heart Rate Variability (HRV) Measurement

The detailed procedures were reported in our previous studies [

17,

18,

29]. Briefly, the participants first sat quietly for 20 min, then a lead I electrocardiogram was recorded for 5 min. To control for fluctuations in the autonomic nervous system over the course of a day, all electrocardiogram recordings were carried out in a quiet and air-conditioned room between 9 and 11 a.m. HC participants were measured only once whereas MDD participants were measured at baseline, at weeks 1, 4, and 8 after agomelatine treatment. The payment was offered to the subjects to reimburse them for the transportation expense of each visit. An HRV analyzer acquired, stored, and processed the electrocardiography signals. Our computer algorithm then identified each QRS complex and rejected each ventricular premature complex or noise according to its likelihood in a standard QRS template. Signals were recorded at a sampling rate of 512 Hz, using an 8-bit analog-to-digital converter. Stationary R-R interval values were re-sampled and interpolated at a rate of 7.11 Hz to produce continuity in the time domain. The standard deviation of NN intervals (SDNN), a time-domain measure of HRV, measures the standard deviation of the time between normal heartbeats (NN intervals) over 5 min. SDNN is calculated by taking the square root of the variance in NN intervals, reflecting all cyclic components responsible for variability during the recording period. It is considered an estimate of overall HRV and the “gold standard” for medical stratification of cardiac risk. A non-parametric fast Fourier transformation was used to perform power spectral analysis. The direct current component was deleted, and a Hamming window was used to attenuate the leakage effect. The power spectrum was subsequently quantified into standard frequency-domain measurements, namely low-frequency power (LF, 0.04–0.15 Hz), high-frequency power (HF, 0.15–0.40 Hz), and the ratio of LF to HF power (LF/HF). Vagal control of HRV is represented by HF, whereas both vagal and sympathetic control of HRV are jointly represented by LF. The LF/HF ratio could mirror sympatho-vagal balance or sympathetic modulation, with a larger LF/HF ratio indicating a greater predominance of sympathetic activity over cardiac vagal control.

2.3. Statistics

Statistical analyses were conducted utilizing IBM SPSS Statistics 24.0 software (IBM SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). All data were checked for deviations from a Gaussian distribution. For the comparisons of continuous variables between the pre-treatment MDD group and the healthy control (HC) group and between the post-treatment MDD group and the HC group, independent t-tests t were used for parametric variables and the Mann-Whitney U tests for nonparametric variables. The χ2 tests were used to examine between-group differences in discrete variables. For the comparisons of continuous variables between baseline and each post-baseline visit, paired t-tests were used for parametric variables and the Wilcoxon Signed-Rank tests for nonparametric variables. Spearman’s correlation analysis was used to investigate the relationship between the change in SDNN from baseline to 1 week after treatment and the change in SHAPS score from baseline to 8 weeks after treatment. Statistical significance was established at p < 0.05 (two-tailed) for the primary outcomes (i.e., the change in SDNN one week after treatment and the change in SHAPS score 8 weeks after treatment as well as their correlation coefficient). To mitigate the increased risk of Type 1 error associated with multiple statistical tests for other secondary outcomes, Bonferroni corrections were applied.

3. Results

This section may be divided by subheadings. It should provide a concise and precise description of the experimental results, their interpretation, as well as the experimental conclusions that can be drawn.

3.1. Sample Characteristics

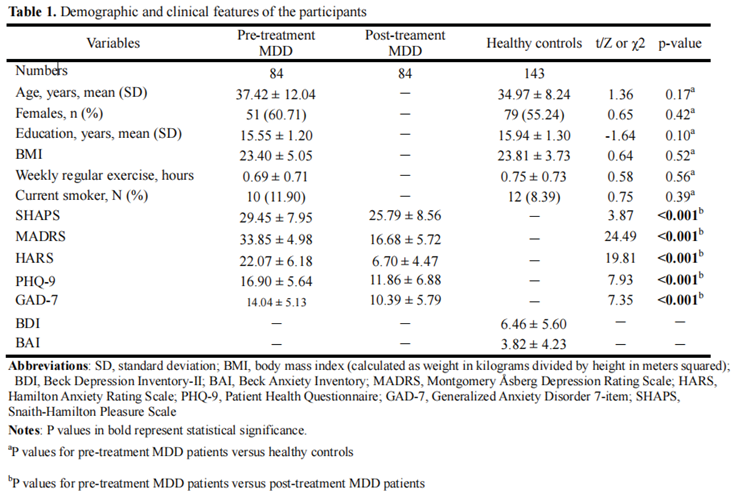

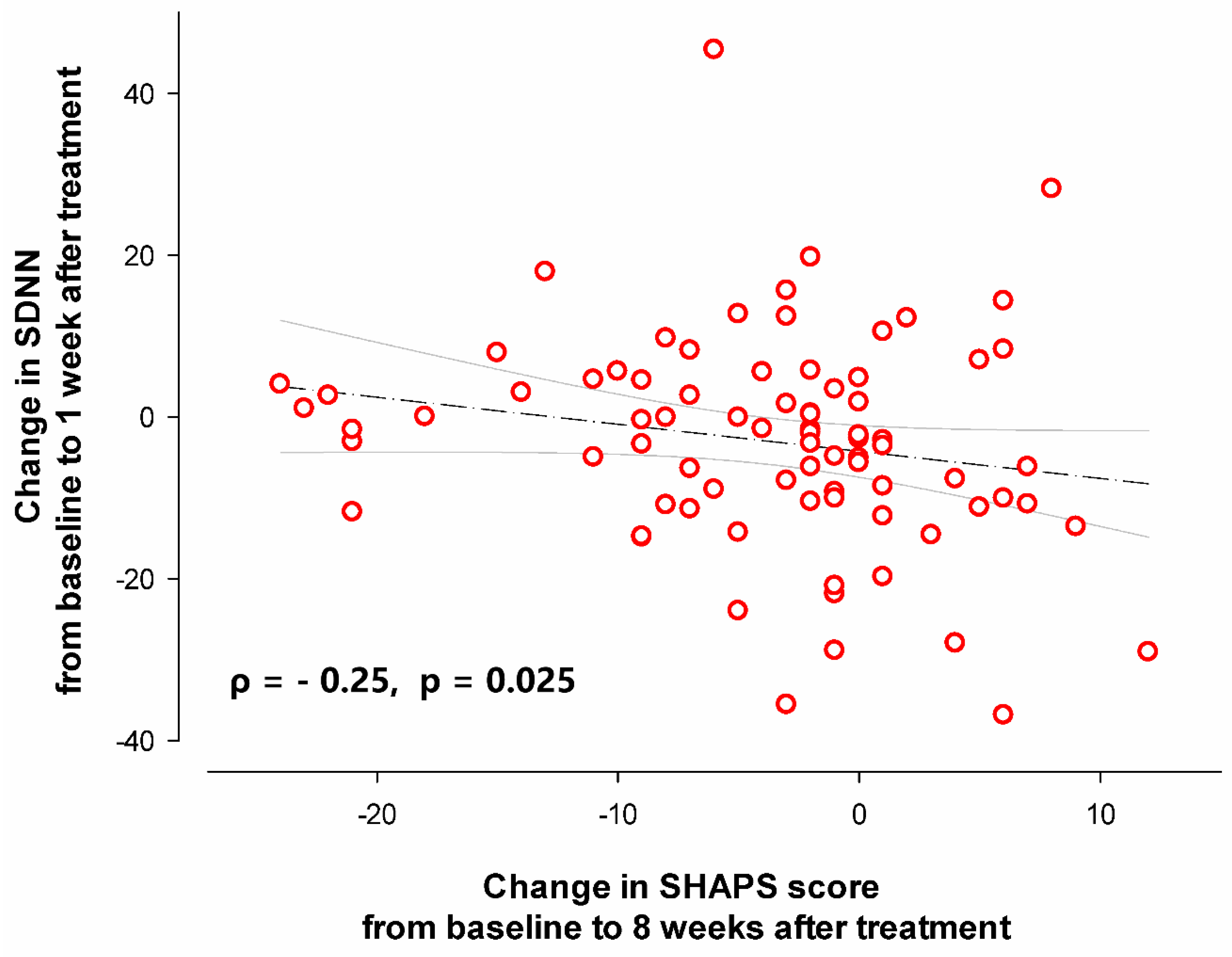

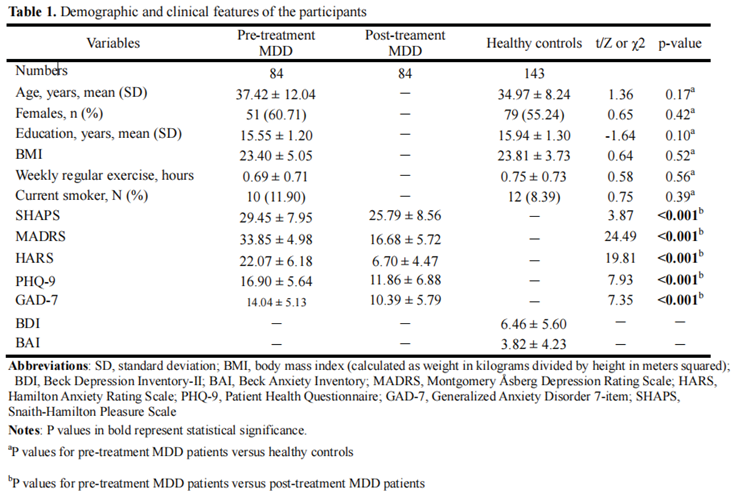

Table 1 presents a summary of the demographic and clinical characteristics of the study participants. There were no significant differences in age, sex, body mass index, exercise levels or smoking status between patients with MDD and HCs (all p values > 0.05). As can be seen in Figure. 1, there was a significant improvement in anhedonia one week after agomelatine monotherapy (Z = -2.86, p = 0.004). The improvement remained 4 weeks (Z = -2.62, p = 0.009) and 8 weeks (Z = -3.9, p < 0.001) after treatment. Depression severity improvement was observed one week (Z = -7.82, p < 0.001), 4 weeks (Z = -7.92, p < 0.001) and 8 weeks after treatment (Z = -7.92, p < 0.001).

Figure 1.

The average improvement in SHAPS and MADRS scores 1 week, 4 weeks, and 8 weeks after agomelatine monontherapy. Error bars represent 95% confidence intervals for the mean. The SHAPS and MADRS scores at baseline versus at each post-baseline assessment were compared using Wilcoxon signed-rank tests. * p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01; *** p < 0.001.

Figure 1.

The average improvement in SHAPS and MADRS scores 1 week, 4 weeks, and 8 weeks after agomelatine monontherapy. Error bars represent 95% confidence intervals for the mean. The SHAPS and MADRS scores at baseline versus at each post-baseline assessment were compared using Wilcoxon signed-rank tests. * p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01; *** p < 0.001.

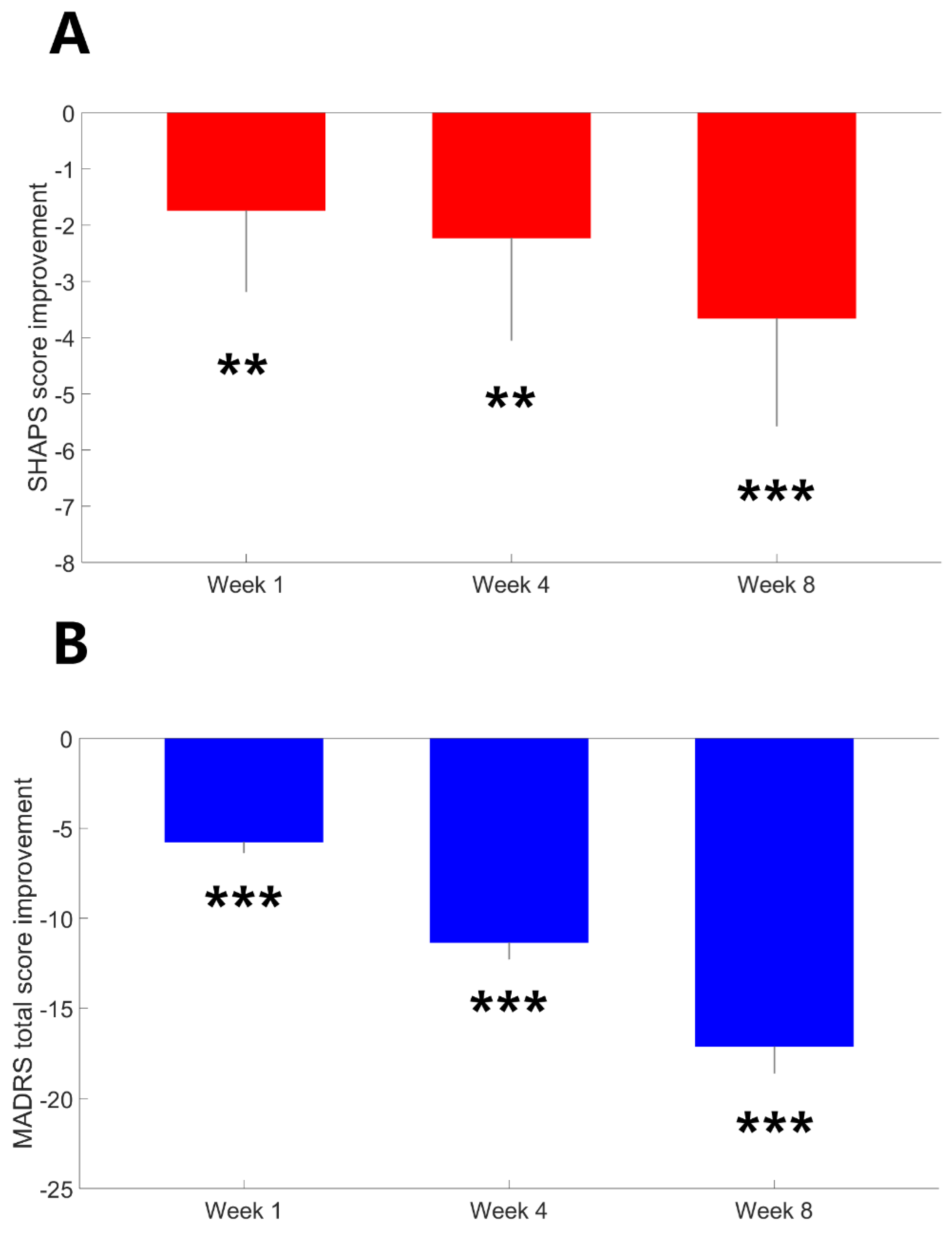

3.2. HRV Metrics Between the Pre-Treatment MDD Cohort and the HC Group

As illustrated in

Figure 2, SDNN (U = -3.63, p < 0.001) and LF (t = -3.66, p < 0.001) were significantly lower in pre-treatment patients with MDD compared to HCs. HF was lower in pre-treatment patients with MDD compared to HCs (t = -2.07, p = 0.04); however, this difference did not achieve the Bonferroni-adjusted threshold for significance. There was no between-group difference in the LF/HF ratio (t = -0.96, p = 0.34).

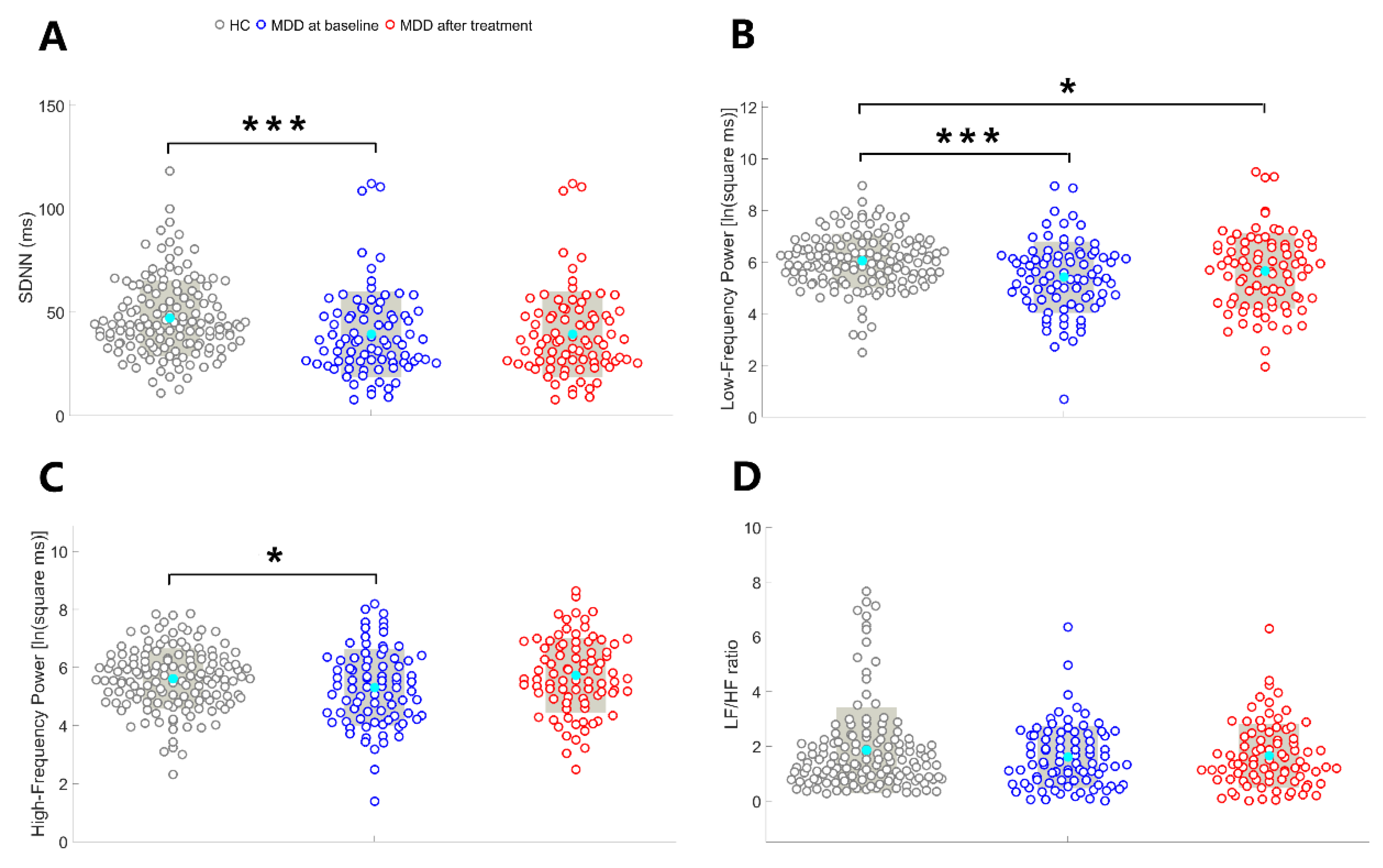

3.3. HRV Metrics from the Baseline to the End of the Treatment

Compared to baseline, there was a significant reduction in SDNN (Z = -7.82, p = 0.026) one week after treatment (

Figure 3.). HF (t = -2.24, p = 0.028) was reduced and LF/HF ratio (Z = 2.15, p = 0.032) was increased from baseline to one week after treatment but this differences did not achieve the Bonferroni-adjusted threshold for significance. SDNN (Z = 3.60, p < 0.001) and HF (t = 3.8, p < 0.001) were significantly increased 8 weeks after treatment. Other results were all nonsignificant.

3.4. HRV Metrics Between the Post-Treatment MDD Cohort and the HC Group

As illustrated in

Figure 2, no between-group differences were identified in the SDNN (U = -1.07, p = 0.29), HF (t = -0.69, p = 0.49), and LF/HF ratio (t = -0.84, p = 0.40). LF was lower in post-treatment patients with MDD compared to HCs (t = -2.18, p = 0.03); however, this difference did not achieve the Bonferroni-adjusted threshold for significance.

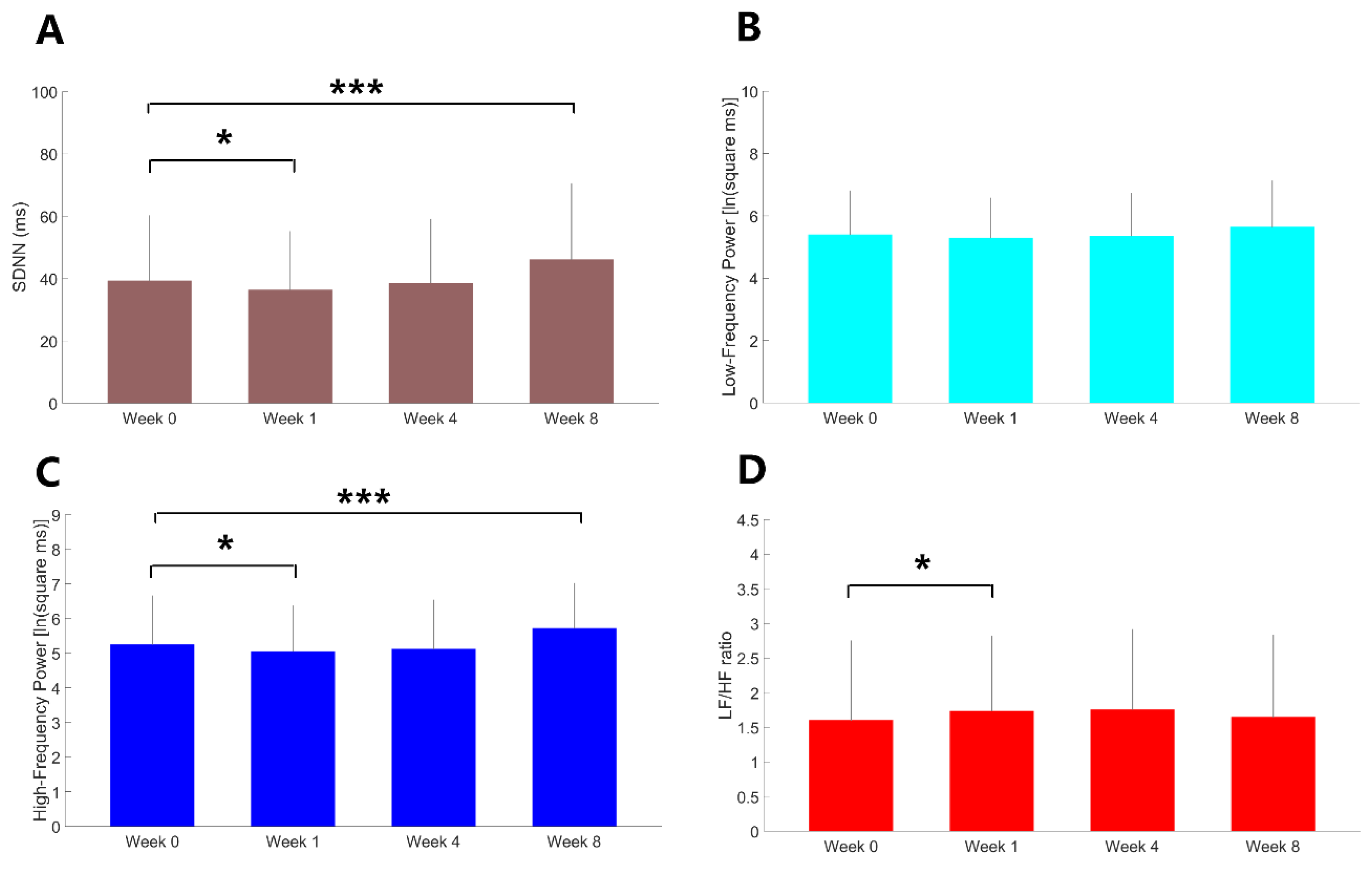

3.5. Correlation Analyses

Correlation analysis showed that the change in SDNN from baseline to 1 week after treatment exhibited a negative correlation with the change in SHAPS score from baseline to 8 weeks after treatment (ρ = - 0.25, p = 0.025,

Figure 4). Specifically, a less reduction in SDNN at 1 week after treatment predicted greater anhedonia improvement following 8-week treatment with agomelatine.

4. Discussion

In line with our primary hypothesis, we found that early HRV change at one week after treatment onset was associated with anhedonia improvement following 8-week agomelatine monotherapy. The study also found that unmedicated patients with MDD exhibited significantly lower HRV (particularly LF-HRV) as compared to HCs. The difference was no longer statistically significant following 8-week agomelatine monotherapy.

Consistent with recent research [

8,

9,

10,

11], significant anhedonia improvement was found soon after starting agomelatine monotherapy and remained all the way to the end of the 8-week treatment. Anhedonia symptoms in MDD patients are known to correlate with functional aberrance in the reward circuit [

30], a neural network with a compact distribution of dopaminergic neurons [

31]. A growing body of evidence supports a link between anhedonia and disorganized melatonin circadian rhythms in MDD. For example, a recent cross-sectional study in MDD patients showed that the peak phase of melatonin circadian rhythms was negatively correlated with anhedonia severity [

32]. Depressed mice showed an increase in the expression of dopamine-related proteins after being treated with melatonin [

33]. It is speculated that normalization of circadian rhythm modulation, e.g. by melatonin treatment, may improve anhedonia by affecting the dopaminergic system. Agomelatine is known for its unique mode of action of synergy between melatonergic receptor activation and 5-HT2c receptor antagonism [

34]. Its exhibition of indirect dopaminergic properties through modulating melatonin rhythms and antagonizing neocortical postsynaptic 5-HT2c receptor plays an important role in rapidly and effectively improving anhedonia symptoms in MDD patients.

Our study showed that HRV was reduced in unmedicated patients with MDD and was significantly increased 8 weeks after agomelatine monotherapy. The HRV improvement mainly derived from a significant increase in parasympathetic activity as indexed by HF-HRV. The result is consistent with previous studies showing that HRV was lower in MDD than in healthy controls [

35] whereas agomelatine monotherapy for at least 6 weeks was associated with increased parasympathetic activity [

17,

18]. Furthermore, the HRV in our depressed patients following 8-week agomelatin monotherapy nearly returned to a normal level which is seldom observed among depressed patients being treated with antidepressants other than agomelatine [

36,

37]. We expected that the melatonergic receptor agonistic effect and 5-HT2c receptor antagonistic effect of agomelatine would increase cardiac vagal activity and decrease sympathetic activity for some potential explanations as below. First, a previous study in healthy men showed that cardiac vagal tone was increased and sympathetic tone was decreased 60 minutes after administration of a single dose of 2 mg melatonin [

38]. Animal research indicated that chronic melatonin treatment decreased heart rate by inhibiting sympathetic activity [

39]. Finally, basic research also indicates that activation of serotonergic 5-HT2c receptors in the nucleus tractus solitarius neurons plays an important role in inhibiting cardiac vagal activity whereas a selective 5-HT2c receptor antagonist prevented the inhibition [

40,

41].

However, in contrary to our expectation early HRV changes were characterized by a significant reduction one week after agomelatine monotherapy. The reduction may derive from a trend-level reduction in parasympathetic tone as indexed by HF-HRV and a trend-level increase in sympathetic modulation as indexed by LF/HF ratio. Evidence suggests that disorganized circadian rhythms (e.g., changes in melatonin levels and core body temperature) play a role in the pathophysiology of MDD and HRV is a good indicator for estimating an individual’s circadian rhythm [

34,

42]. A recent study showed that the circadian rhythm of HRV oscillation (SDNN) of drug-free MDD patients reached the peak time in the morning around 06 a.m. and the trough time in the evening around 06 p.m. [

42]. Agomelatine is known to produce a phase advance in the circadian changes in melatonin levels and core body temperature and advance the timing of the daily decrease in heart rate [

34]. Repeated activation of melatonin receptors has been reported to phase-advance HRV indices by altering the timing of the endogenous circadian rhythms of HRV [

43]. Since it was known to take at least 6 weeks for 25mg agomelatine per day to significantly and stably increase HRV in MDD patients [

17,

18], the HRV phase-advancing effect of agomelatine at the early stage of treatment may explain the reduction in HRV one week after treatment as compared to baseline. Normalization of circadian rhythm modulation by agomelatine may have a positive effect on dopaminergic neurons in the reward circuit and thereby improve anhedonia symptoms in the short run as well as in the long run.

Earlier evidence indicated HRV as a potential biomarker for predicting response to serotonergic antidepressant medications [

44]. Our study is the first to demonstrate the early HRV change as a biomarker to predict anhedonia improvement with the melatonergic antidepressant. HRV is considered a valuable proxy for assessing circadian disruptions in MDD patients and previous research has found a correlation between anhedonia and HRV (particularly vagal modulation of HRV) [

14,

15,

16]. It seems difficult to comprehend why a lower reduction in HRV at the end of one-week treatment predicted more anhedonia improvement following 8-week agomelatine monotherapy, at first glance. However, it is plausible that patients showing a lower reduction in HRV following one-week treatment were those who also had a rapid and mild HRV increase in response to agomelatine’s vagotonic effect [

17,

18] in addition to agomelatine’s phase-advancing effect. The early HRV increase as a response to one-week agomelatine treatment might have mitigated the observed HRV reduction stemming from the phase-advancing effect of agomelatine with both factors having beneficial effects on anhedonia improvement. Taken together, we speculate that early changes and dynamics of HRV can serve as a biomarker to predict anhedonia improvement with agomelatine treatment in depressed patients. To further corroborate our speculation, further experiments will be necessary to explore the neurobiological mechanisms between circadian rhythm modulation in HRV and anhedonia in MDD and whether circadian rhythm modulation in HRV can be a clinically useful biomarker to predict anhedonia improvement in MDD patients.

The present study has several significant limitations. First, this is a prospective observational cohort study where only complete HRV and clinical data were analyzed, giving rise to potential selection bias. Second, the clinical implications of agomelatine-associated changes in HRV should be interpreted cautiously. These changes might reflect a therapeutic process associated with improvement in both ANS dysregulation and depression. Third, the changes over time in short-term HRV results reported herein should be considered preliminary because they might have been interfered with the effect of agomelatine in phase-advancing circadian rhythm modulation. Future studies using continuous 24-H Holter electrocardiogram (ECG) recording and circadian rhythm analyses of HRV should be carried out to confirm the effect of agomelatine on HRV in depressed patients.

5. Conclusions

Our studies showed a reduced HRV in unmedicated patients with MDD as compared to normal controls. The reduction in HRV was normalized and anhedonia was significantly improved after 8-week agomelatine monotherapy. Early HRV changes at one week predicted more anhedonia improvement following 8-week agomelatine monotherapy.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.M.; methodology, H.C. and C.C.; software, C.Y., W.C.; validation, A.T.S., H.C. and C.C.; formal analysis, H.C. and C.C.; data curation, H.C.; writing: original draft preparation, C.M.; manuscript editing, A.T.S., H.C. and C.C; visualization, W.C.; supervision, A.T.S., H.C. and C.C.; project administration, H.C.; funding acquisition, H.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported in part by grants from Advanced National Defense Technology & Research Program, National Science and Technology Council of Taiwanese Government (NSTC-112-2314-B-016-017-MY3), Tri-Service General Hospital (TSGH_D_114143 and TSGH-B-114024), Medical Affairs Bureau, Ministry of National Defense, Taipei, Taiwan (MND-MAB-D-114127 and MND-MAB-D-114125), Servier (Suresnes, France). ATS received funding from the Dutch Research Council (NWO). This publication is part of the project "Towards Personalized Neuromodulation in Mental Health – a non-invasive avenue of network research into dynamic brain circuits and their dysfunction" with file number 406.20.GO.004 of the research programme Open Competition.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Tri-Service General Hospital, Taipei, Taiwan (code: B202205019 and date of approval: Feb 15, 2022).

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent has been obtained from the patients to publish this paper.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We appreciate all the patients who have participated in this study. The authors also acknowledge the PET-MRI support from the Department of Radiology at Tri-Service General Hospital.

Conflicts of Interest

Hsin-An Chang has disclosed receiving honoraria for presentations at conferences and advisory roles from several pharmaceutical companies, including Chen Hua Biotech, Eisai, Janssen, Lundbeck, Lotus, Otsuka, Pfizer, Servier, Sanofi-Aventis, Sumitomo Dainippon Pharma, and Viatris. ATS is director of the Academy of Brain Stimulation (

www.brainstimulation-academy.com) and the International Clinical TMS Certification Course (

www.tmscourse.eu), receiving equipment support from MagVenture, MagStim, Deymed, Yingchi, Brainsway. He also serves as scietific advisor for Platoscince Medical and Alpha Brain Technologies. Other authors declared no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Xiang, Y.-T.; Wang, G.; Hu, C.; Guo, T.; Ungvari, G.S.; Kilbourne, A.M.; et al. Demographic and clinical features and prescribing patterns of psychotropic medications in patients with the melancholic subtype of major depressive disorder in China. PloS one. 2012, 7, e39840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, N.; Li, Y.; Cai, Y.; Chen, J.; Shen, Y.; Sun, J.; et al. A COMPARISON OF MELANCHOLIC AND NONMELANCHOLIC RECURRENT MAJOR DEPRESSION IN HAN CHINESE WOMEN. Depression and Anxiety. 2012, 29, 4–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunlop, K.; Rizvi, S.J.; Kennedy, S.H.; Hassel, S.; Strother, S.C.; Harris, J.K.; et al. Clinical, behavioral, and neural measures of reward processing correlate with escitalopram response in depression: a Canadian Biomarker Integration Network in Depression (CAN-BIND-1) Report. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2020, 45, 1390–1397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geugies, H. ; Mocking RJT, Figueroa, C. A.; Groot PFC, Marsman, J.C.; Servaas, M.N.; et al. Impaired reward-related learning signals in remitted unmedicated patients with recurrent depression. Brain. 2019, 142, 2510–2522. [Google Scholar]

- Nierenberg, A.A. Residual symptoms in depression: prevalence and impact. J Clin Psychiatry. 2015, 76:e1480. [CrossRef]

- Price, J.; Cole, V.; Goodwin, G.M. Emotional side-effects of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors: qualitative study. Br J Psychiatry. 2009, 195, 211–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCabe, C.; Mishor, Z.; Cowen, P.J.; Harmer, C.J. Diminished neural processing of aversive and rewarding stimuli during selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor treatment. Biol Psychiatry. 2010, 67, 439–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Xie, X.M.; Lyu, N.; Fu, B.B.; Zhao, Q.; Zhang, L.; et al. Agomelatine in the treatment of anhedonia, somatic symptoms, and sexual dysfunction in major depressive disorder. Front Psychiatry. 2023, 14, 1115008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gargoloff, P.D.; Corral, R.; Herbst, L.; Marquez, M.; Martinotti, G.; Gargoloff, P.R. Effectiveness of agomelatine on anhedonia in depressed patients: an outpatient, open-label, real-world study. Hum Psychopharmacol. 2016, 31, 412–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, P.; Xu, Y.; Lv, L.; Feng, M.; Fang, Y.; Huang, W.Q.; et al. A multicenter, randomized controlled study on the efficacy of agomelatine in ameliorating anhedonia, reduced motivation, and circadian rhythm disruptions in patients with major depressive disorder (MDD). Ann Gen Psychiatry. 2023, 22, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Giannantonio, M.; Di Iorio, G.; Guglielmo, R.; De Berardis, D.; Conti, C.M.; Acciavatti, T.; et al. Major depressive disorder, anhedonia and agomelatine: an open-label study. J Biol Regul Homeost Agents. 2011, 25, 109–114. [Google Scholar]

- Gullett, N.; Zajkowska, Z.; Walsh, A.; Harper, R.; Mondelli, V. Heart rate variability (HRV) as a way to understand associations between the autonomic nervous system (ANS) and affective states: A critical review of the literature. Int J Psychophysiol. 2023, 192, 35–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hillebrand, S.; Gast, K.B.; de Mutsert, R.; Swenne, C.A.; Jukema, J.W.; Middeldorp, S.; et al. Heart rate variability and first cardiovascular event in populations without known cardiovascular disease: meta-analysis and dose-response meta-regression. Europace. 2013, 15, 742–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kemp, A.H.; Quintana, D.S.; Quinn, C.R.; Hopkinson, P.; Harris, A.W. Major depressive disorder with melancholia displays robust alterations in resting state heart rate and its variability: implications for future morbidity and mortality. Front Psychol. 2014, 5, 1387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borrione, L.; Brunoni, A.R.; Sampaio-Junior, B.; Aparicio, L.M.; Kemp, A.H.; Bensenor, I.; et al. Associations between symptoms of depression and heart rate variability: An exploratory study. Psychiatry Res. 2018, 262, 482–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vazquez, L.; Blood, J.D.; Wu, J.; Chaplin, T.M.; Hommer, R.E.; Rutherford, H.J.; et al. High frequency heart-rate variability predicts adolescent depressive symptoms, particularly anhedonia, across one year. J Affect Disord. 2016, 196, 243–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yeh, T.C.; Kao, L.C.; Tzeng, N.S.; Kuo, T.B.; Huang, S.Y.; Chang, C.C.; et al. Heart rate variability in major depressive disorder and after antidepressant treatment with agomelatine and paroxetine: Findings from the Taiwan Study of Depression and Anxiety (TAISDA). Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2016, 64, 60–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, C.C.; Tzeng, N.S.; Yeh, C.B. ; Kuo TBJ, Huang, S. Y.; Chang, H.A. Effects of depression and melatonergic antidepressant treatment alone and in combination with sedative-hypnotics on heart rate variability: Implications for cardiovascular risk. World J Biol Psychiatry. 2018, 19, 368–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.E.; Chen, L.F.; Chung, C.H.; Chang, C.C.; Chang, H.A. Resting EEG source-level connectivity pattern to predict anhedonia improvement with agomelatine treatment in patients with major depression. J Affect Disord. 2025. [CrossRef]

- Chu, C.S.; Lin, Y.Y.; Huang, C.C.; Chung, Y.A.; Park, S.Y.; Chang, W.C.; et al. Altered electroencephalography-based source functional connectivity in drug-free patients with major depressive disorder. J Affect Disord. 2025, 369, 1161–1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.F.; Lin, C.E.; Chung, C.H.; Chung, Y.A.; Park, S.Y.; Chang, W.C.; et al. The association between anhedonia and prefrontal cortex activation in patients with major depression: a functional near-infrared spectroscopy study. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2025. [CrossRef]

- Sheehan, D.V.; Lecrubier, Y.; Sheehan, K.H.; Amorim, P.; Janavs, J.; Weiller, E.; et al. The Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (M.I.N.I.): the development and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10. J Clin Psychiatry. 1998, 59 Suppl 20, 22-33;quiz 4-57.

- Montgomery, S.A.; Åsberg, M. A new depression scale designed to be sensitive to change. The British journal of psychiatry. 1979, 134, 382–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snaith, R.P.; Hamilton, M.; Morley, S.; Humayan, A.; Hargreaves, D.; Trigwell, P. A scale for the assessment of hedonic tone the Snaith-Hamilton Pleasure Scale. Br J Psychiatry. 1995, 167, 99–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.H.; Wang, L.Z.; Zhu, Y.H.; Li, M.H.; Chan, R.C. Clinical utility of the Snaith-Hamilton-Pleasure scale in the Chinese settings. BMC Psychiatry. 2012, 12, 184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chung, T.H.; Hanley, K.; Le, Y.-C.; Merchant, A.; Nascimento, F.; De Figueiredo, J.M.; et al. A validation study of PHQ-9 suicide item with the Columbia Suicide Severity Rating Scale in outpatients with mood disorders at National Network of Depression Centers. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2023, 320, 590–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toussaint, A.; Hüsing, P.; Gumz, A.; Wingenfeld, K.; Härter, M.; Schramm, E.; et al. Sensitivity to change and minimal clinically important difference of the 7-item Generalized Anxiety Disorder Questionnaire (GAD-7). Journal of Affective Disorders. 2020, 265, 395–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, H.A.; Fang, W.H.; Liu, Y.P.; Tzeng, N.S.; Shyu, J.F.; Wan, F.J.; et al. BDNF Val(6)(6)Met polymorphism to generalized anxiety disorder pathways: Indirect effects via attenuated parasympathetic stress-relaxation reactivity. J Abnorm Psychol. 2020, 129, 237–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, H.A.; Chang, C.C.; Kuo, T.B.; Huang, S.Y. Distinguishing bipolar II depression from unipolar major depressive disorder: Differences in heart rate variability. World J Biol Psychiatry. 2015, 16, 351–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitton, A.E.; Treadway, M.T.; Pizzagalli, D.A. Reward processing dysfunction in major depression, bipolar disorder and schizophrenia. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2015, 28, 7–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haber, S.N.; Knutson, B. The reward circuit: linking primate anatomy and human imaging. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2010, 35, 4–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Yu, J.; Jiang, S.; Fang, L.; Li, Y.; Ma, S.; et al. Circadian rhythms of melatonin and its relationship with anhedonia in patients with mood disorders: a cross-sectional study. BMC Psychiatry. 2024, 24, 165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefanovic, B.; Spasojevic, N.; Jovanovic, P.; Dronjak, S. Melatonin treatment affects changes in adrenal gene expression of catecholamine biosynthesizing enzymes and norepinephrine transporter in the rat model of chronic-stress-induced depression. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 2019, 97, 685–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guardiola-Lemaitre, B.; De Bodinat, C.; Delagrange, P.; Millan, M.J.; Munoz, C.; Mocaer, E. Agomelatine: mechanism of action and pharmacological profile in relation to antidepressant properties. Br J Pharmacol. 2014, 171, 3604–3619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koch, C.; Wilhelm, M.; Salzmann, S.; Rief, W.; Euteneuer, F. A meta-analysis of heart rate variability in major depression. Psychol Med. 2019, 49, 1948–1957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, M.X.; Milaneschi, Y.; Lamers, F.; Nolte, I.M.; Snieder, H.; Dolan, C.V.; et al. The association of depression and anxiety with cardiac autonomic activity: The role of confounding effects of antidepressants. Depress Anxiety. 2019, 36, 1163–1172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carney, R.M.; Freedland, K.E. Depression and coronary heart disease. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2017, 14, 145–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishiyama, K.; Yasue, H.; Moriyama, Y.; Tsunoda, R.; Ogawa, H.; Yoshimura, M.; et al. Acute effects of melatonin administration on cardiovascular autonomic regulation in healthy men. Am Heart J. 2001, 141:E9.

- Girouard, H.; Chulak, C.; LeJossec, M.; Lamontagne, D.; de Champlain, J. Chronic antioxidant treatment improves sympathetic functions and beta-adrenergic pathway in the spontaneously hypertensive rats. J Hypertens. 2003, 21, 179–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sevoz-Couche, C.; Spyer, K.M.; Jordan, D. Inhibition of rat nucleus tractus solitarius neurones by activation of 5-HT2C receptors. Neuroreport. 2000, 11, 1785–1790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordan, D. Vagal control of the heart: central serotonergic (5-HT) mechanisms. Exp Physiol. 2005, 90, 175–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, Y.; Zhang, H.; Wang, Z.; Song, Y.; Shi, K.; Fan, J.; et al. Circadian rhythm modulation in heart rate variability as potential biomarkers for major depressive disorder: A machine learning approach. J Psychiatr Res. 2025, 184, 340–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandewalle, G.; Middleton, B.; Rajaratnam, S.M.; Stone, B.M.; Thorleifsdottir, B.; Arendt, J.; et al. Robust circadian rhythm in heart rate and its variability: influence of exogenous melatonin and photoperiod. J Sleep Res. 2007, 16, 148–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kircanski, K.; Williams, L.M.; Gotlib, I.H. Heart rate variability as a biomarker of anxious depression response to antidepressant medication. Depress Anxiety. 2019, 36, 63–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).