Introduction

Antibiotic resistance remains a global health threat, with multidrug-resistant (MDR) infections rendering conventional therapies ineffective. In this context, bacteriophages (phages) viruses that infect and lyse bacteria have re-emerged as promising alternatives due to their species-specificity, self-amplification, and microbiome preservation [

1,

2].

Structurally, phages are macromolecular assemblies that function like supramolecular nanomachines. Their infection cycle adsorption, DNA injection, replication, and lysis is governed by precise molecular interactions [

3]. Unlike broad-spectrum antibiotics, phages recognize specific bacterial receptors through evolved tail fibers and baseplate proteins. These interactions mirror ligand-receptor binding in molecular chemistry [

4].

Key to their antibacterial action is the lytic phase, where enzymes such as

endolysins cleave peptidoglycan bonds, while

holins create timed membrane pores that release progeny [

5]. These enzymes exhibit bond-specific catalysis, often relying on conserved catalytic residues or metal ions for function [

6]. Their specificity reduces off-target effects and supports narrow-spectrum therapeutic use.

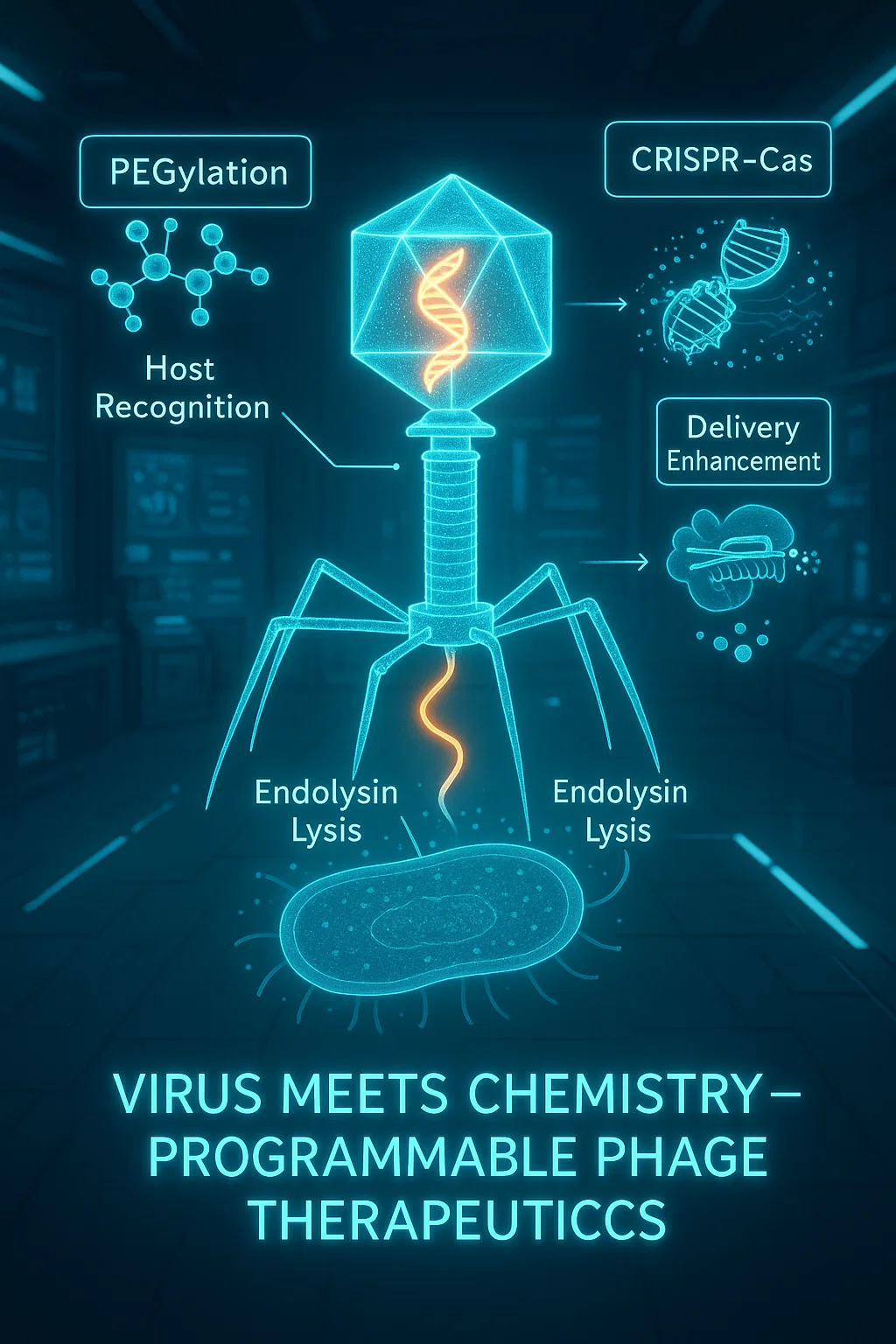

Recent advances in

surface chemistry like PEGylation and ligand conjugation—have enhanced phage pharmacokinetics and targeting ability [

7]. In parallel, genomic sequencing and machine learning now enable rapid phage annotation, host prediction, and personalized therapeutic development [

8,

9].

By integrating chemical biology, synthetic engineering, and bioinformatics, phages can now be reframed as programmable nanomachines designed for precision medicine. This review outlines the structural, chemical, and genomic mechanisms that underpin this transformation.

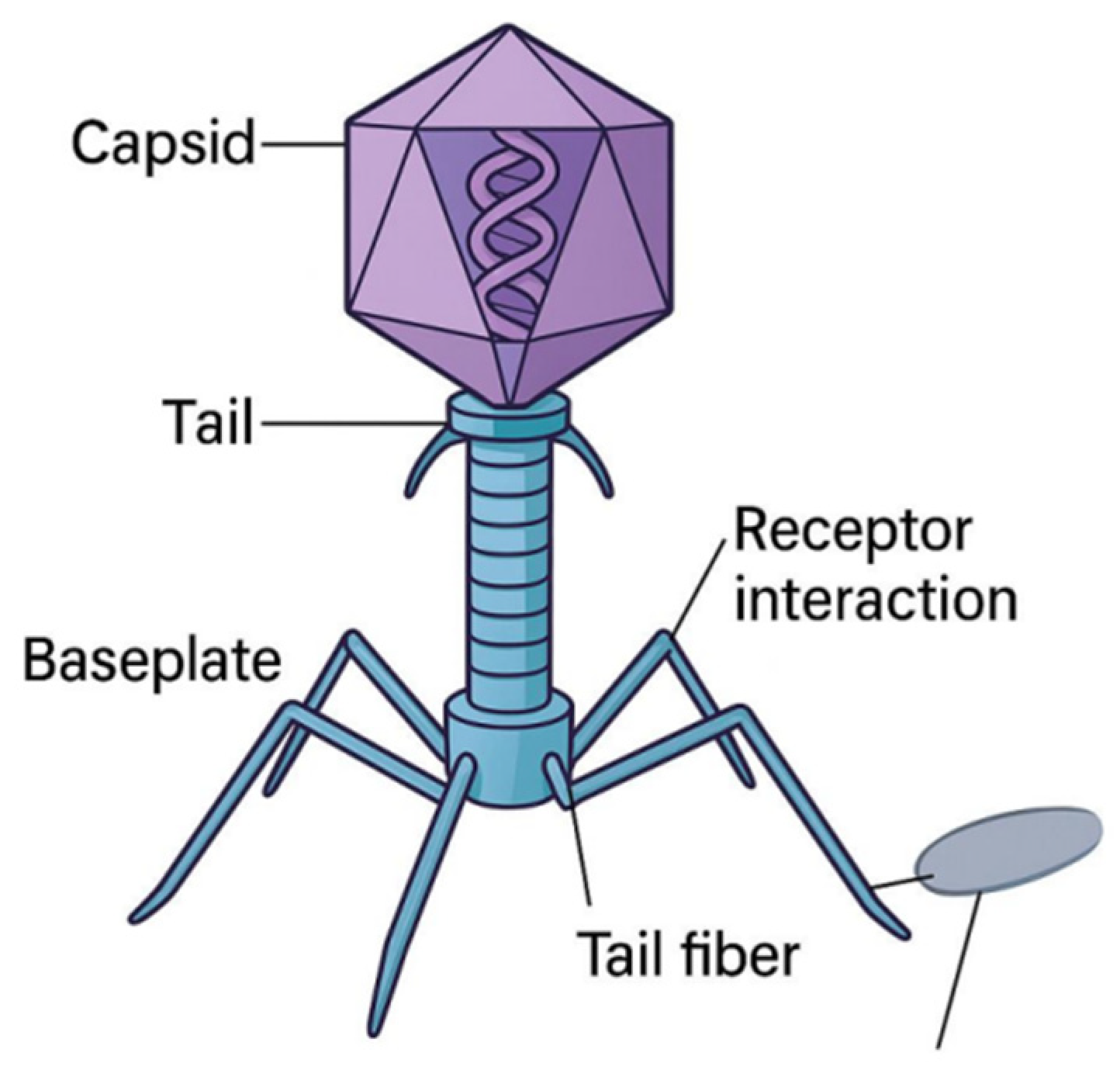

Molecular Architecture of Bacteriophages

Bacteriophages, particularly tailed types within the order

Caudoviricetes, exhibit a conserved modular structure comprising a protein capsid, a tail for genome delivery, and tail fibers or baseplates for host recognition [

10]. These structures are stabilized by non-covalent interactions such as hydrogen bonds, electrostatic forces, and hydrophobic packing mirroring principles of supramolecular chemistry [

11].

The

capsid is typically icosahedral and encloses tightly packed double-stranded DNA. Internal pressures from DNA compaction (~50 atm) drive injection upon infection [

12]. This pressure is stabilized by divalent cations and DNA–protein interactions that protect the genome during extracellular transport [

13].

The

tail structure varies by phage family:

Myoviridae exhibit contractile tails,

Siphoviridae have flexible tails, and

Podoviridae possess short stubs [

10]. Tail fibers interact with specific bacterial receptors, including lipopolysaccharides, outer membrane proteins, or teichoic acids. These ligand–receptor interactions are chemically selective and determine host range [

14].

Figure 1 presents a schematic representation of a canonical tailed bacteriophage, highlighting its icosahedral capsid encasing double-stranded DNA, a contractile tail sheath, baseplate, and terminal tail fibers. The tail fibers are depicted engaging specific bacterial surface receptors such as lipopolysaccharides or outer membrane proteins demonstrating molecular selectivity akin to ligand–receptor binding interactions in synthetic chemistry.

Phage self-assembly is a chemically guided process involving scaffolding proteins, chaperones, and energy-dependent DNA-packaging motors. The resulting architecture functions as a targeted nanodevice engineered by evolution for delivery precision and stability in harsh conditions [

15].

Understanding this architecture supports rational design of phages with enhanced infectivity, structural stability, or engineered surfaces for therapeutic use.

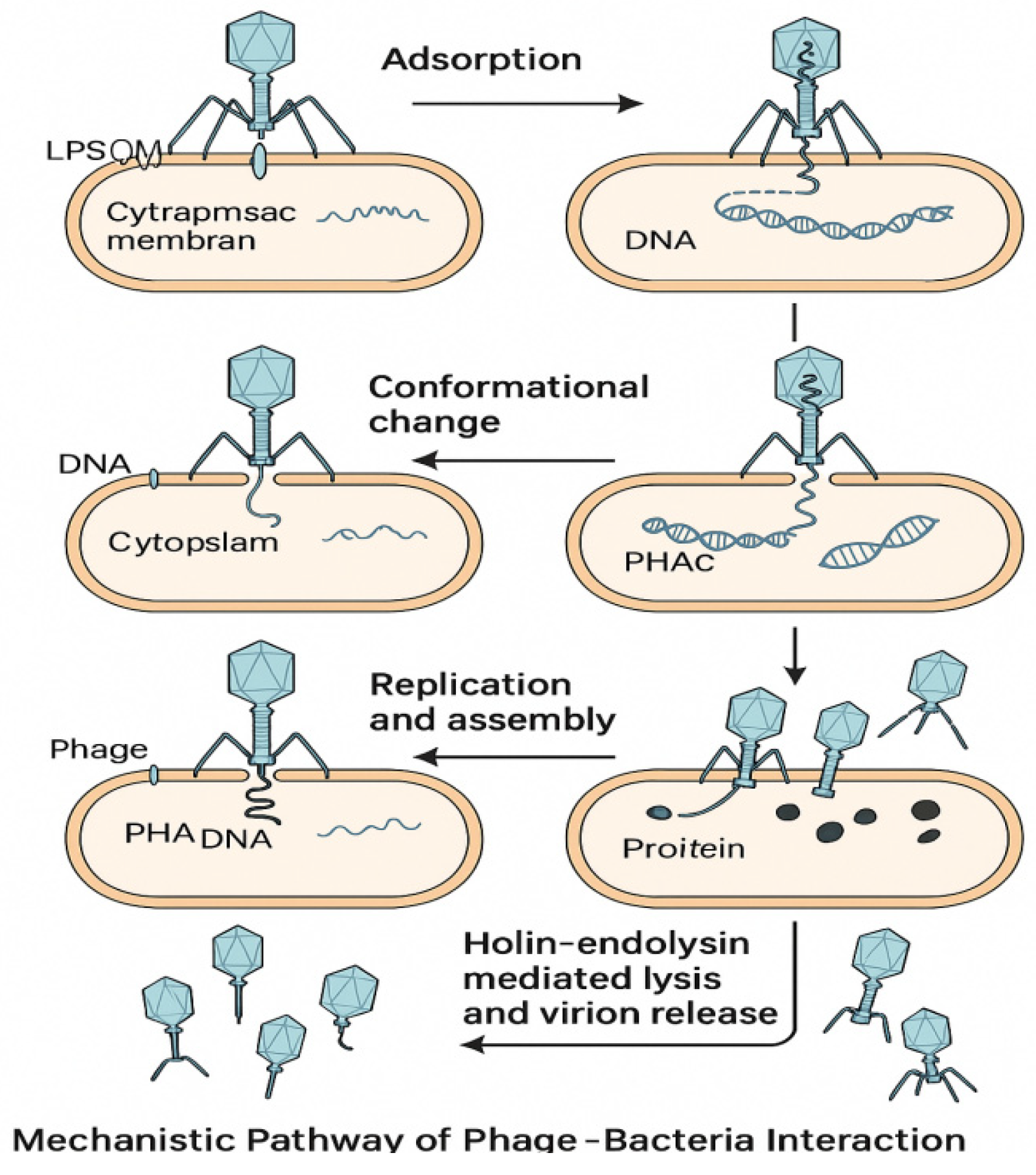

Mechanistic Chemistry of Phage–Bacteria Interaction

Phage–bacteria interaction is a multi-stage process governed by precise chemical recognition and structural transitions. Each step adsorption, DNA injection, replication, and lysis demonstrates fine molecular coordination [

16]. Illustrated in

Figure 2, stepwise chemical and structural processes of phage infection include: (1) host recognition via tail fiber ligand binding; (2) genome injection; (3) replication; (4) enzymatic lysis via holins and endolysins; and (5) phage release. Each stage emphasizes molecular interactions and catalysis.

Adsorption begins with reversible binding between phage tail fibers or receptor-binding proteins (RBPs) and bacterial surface molecules such as lipopolysaccharides (LPS) or outer membrane proteins. These interactions rely on hydrogen bonding, hydrophobic effects, and electrostatic complementarity, mimicking host–ligand specificity in synthetic biology [

17].

Upon irreversible attachment,

conformational changes in the tail structure trigger genome injection. In

Myoviridae, tail sheath contraction propels a hollow tube into the bacterial cell wall. This process is powered by the stored pressure within the capsid and completed in milliseconds [

18].

Following replication, phages initiate

lysis through enzymes that degrade the host envelope. Holins form pores in the cytoplasmic membrane, while endolysins hydrolyze glycosidic or amide bonds in the peptidoglycan. These enzymes exhibit site-specific catalysis, minimizing off-target effects and microbial resistance development [

19].

The chemical choreography of these steps reveals phages as self-contained, time-regulated molecular machines efficient, selective, and programmable for targeted antimicrobial action [

20].

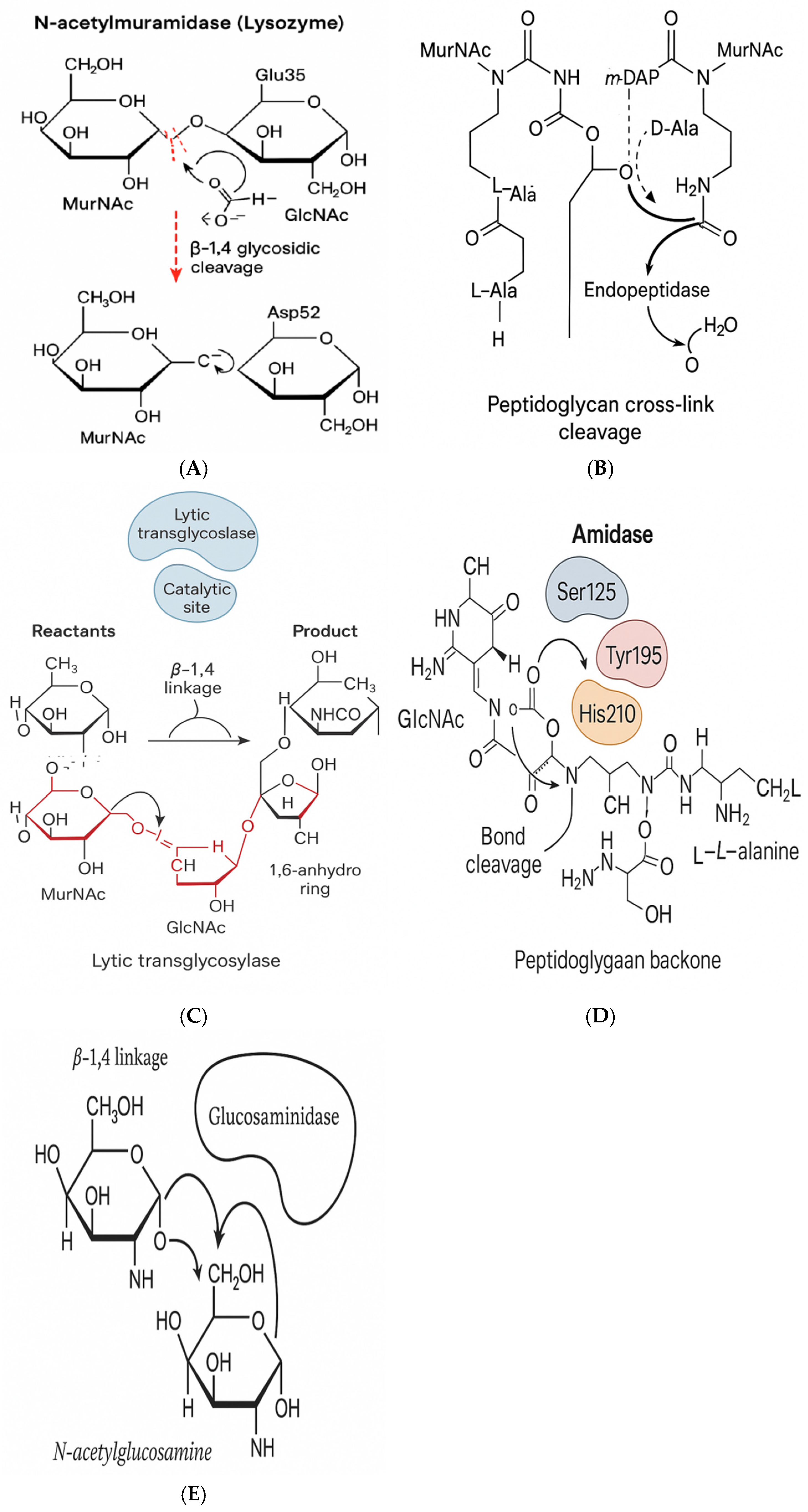

Enzymatic Lysis: Endolysins, Holins, and Catalytic Strategies

Endolysins and holins orchestrate the final step of phage infection host cell lysis. Their enzymatic mechanisms are chemically selective, allowing phages to kill bacteria with surgical precision [

21]. As illustrated in

Figures 3A–3E, endolysins can be classified into at least five distinct enzymatic classes based on their cleavage sites and catalytic modes.

- (a)

N-acetylmuramidases: cleave β-1,4 bonds between MurNAc and GlcNAc.

- (b)

Amidases: hydrolyze amide bonds between MurNAc and L-Ala.

- (c)

Endopeptidases: target peptide bridges.

- (d)

Transglycosylases: generate 1,6-anhydro rings [

22].

These enzymes often function via acid–base catalysis, utilizing conserved glutamic/aspartic residues, and sometimes metal cofactors (e.g., Zn

2+) for transition state stabilization [

23].

2. Holins are small, membrane-integrating proteins that form pores at a precisely timed phase during phage replication. Their oligomerization enables endolysins to access the peptidoglycan. In Gram-negative hosts, additional proteins like spanins assist in disrupting the outer membrane [

24].

These lytic proteins are being engineered into:

Together, endolysins and holins form a chemically elegant, bond-specific, and temporally regulated antibacterial strategy.

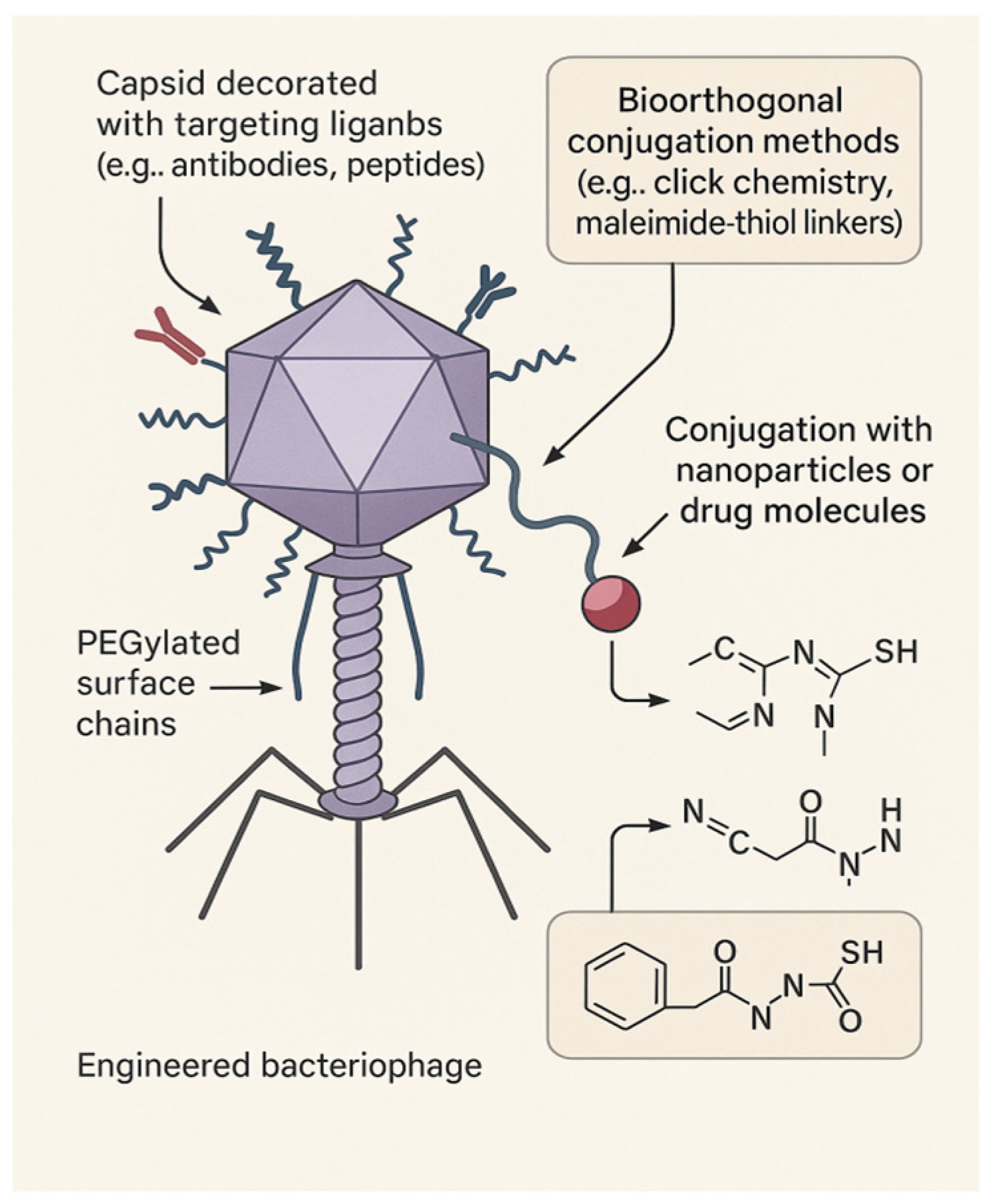

Phage Engineering and Surface Chemistry

Modern chemistry and bioengineering have enabled the reprogramming of phages into customizable delivery platforms.

Figure 3.

Catalytic mechanisms of phage-derived enzymes. (A) Muramidase cleaving β-1,4 glycosidic bonds between GlcNAc and MurNAc. (B) Endopeptidase breaking peptide cross-links in peptidoglycan. (C) Transglycosylase forming 1,6-anhydro rings via cyclization.

Figure 3.

Catalytic mechanisms of phage-derived enzymes. (A) Muramidase cleaving β-1,4 glycosidic bonds between GlcNAc and MurNAc. (B) Endopeptidase breaking peptide cross-links in peptidoglycan. (C) Transglycosylase forming 1,6-anhydro rings via cyclization.

Capsid Engineering

Using click chemistry (e.g., CuAAC, SPAAC), amide coupling, or thiol–maleimide conjugation, researchers have functionalized capsid and tail proteins with targeting ligands, imaging agents, or stimuli-responsive moieties [

26].

PEGylation

PEGylation enhances pharmacokinetics by extending circulation time, reducing immune clearance, and improving tissue diffusion, all while retaining infectivity [

27].

Phage Display

By fusing peptides or proteins to capsid coat proteins (typically pIII or pVIII), phage display allows the identification and presentation of ligands targeting specific bacterial strains or tumor cells [

28].

Phage–Nanoparticle Hybrids

Hybrid constructs merge phages with synthetic materials:

- ⮚

Gold–phage: For photo-thermal ablation of biofilms.

- ⮚

Magnetic–phage: For guided drug delivery.

- ⮚

Drug–phage: Co-deliver antibiotics and matrix-degrading enzymes [

29].

- ⮚

Synthetic Phages

De-novo synthesis of phage genomes and structural proteins has enabled the design of synthetic phages with enhanced host specificity, reduced immunogenicity, and customized payloads [

30].

These developments showcase phages as chemically programmable platforms, bridging nanotechnology and targeted medicine, as shown in

Figure 4 above.

Therapeutic Applications and Challenges

Phages are gaining traction in clinical settings, particularly against multidrug-resistant pathogens.

Infectious Disease

Phage therapy has demonstrated success in treating sepsis, cystic fibrosis lung infections, and non-healing wounds. Case studies support the use of personalized cocktails tailored to the patient’s bacterial isolate [

31].

Biofilm Disruption

Phages produce depolymerases and matrix-degrading enzymes that penetrate biofilms, kill metabolically dormant cells, and prevent recolonization. They are being formulated in hydrogels, coatings, and wound dressings [

32].

Targeted Drug and Gene Delivery

Engineered phages deliver:

Challenges

Barriers include:

Solutions under development include PEGylation, susceptibility-matched libraries, and AI-guided phage selection tools.

Phages are positioned to become front-line therapeutics—adaptable, evolvable, and precision-guided.

Genomics, Bioinformatics, and the Future of Precision Phage Therapeutics

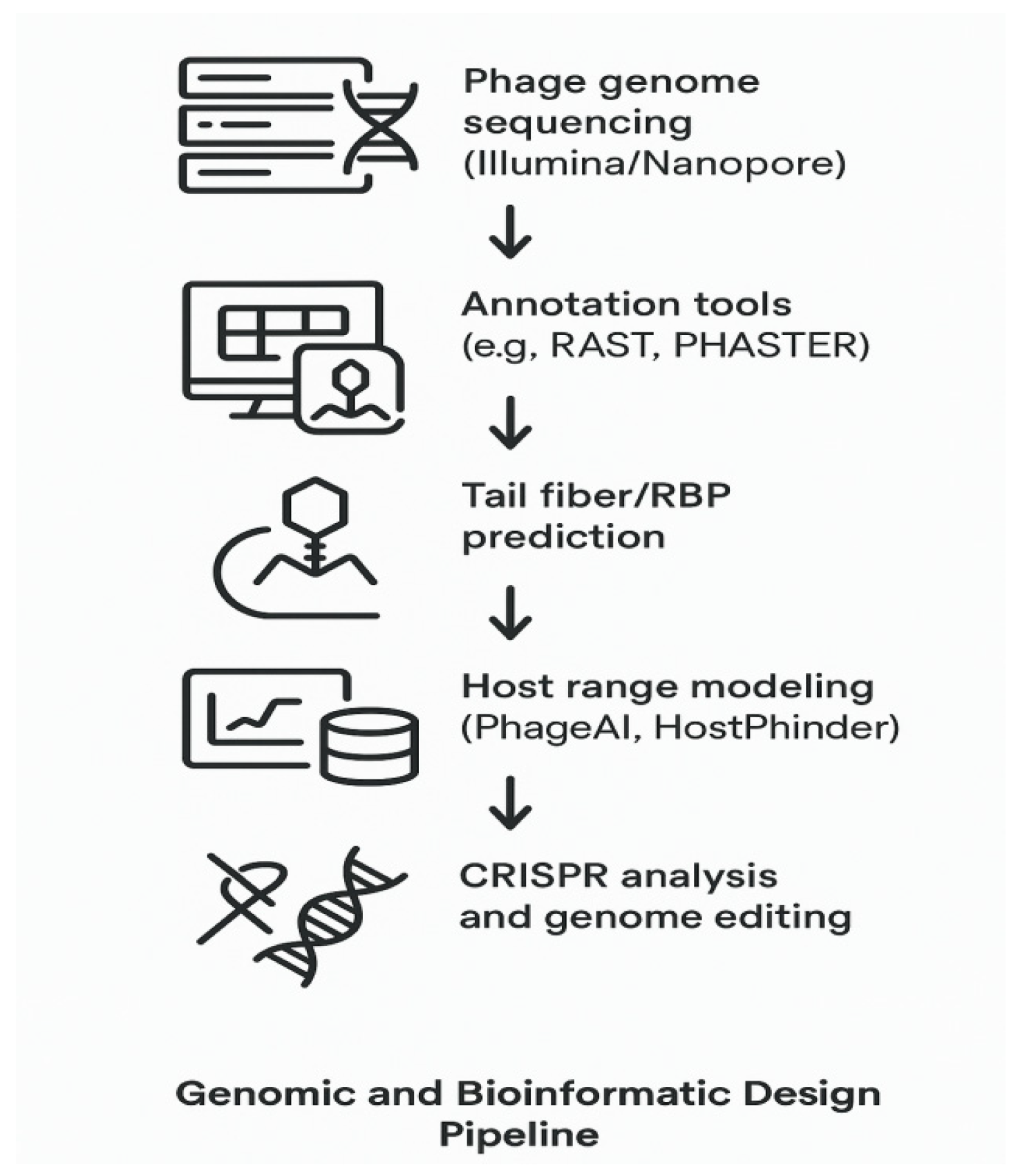

Genomic tools have transformed phage discovery and design into a rational, data-driven process.

Genome Sequencing and Annotation

Platforms like RAST, Prokka, and PHASTER rapidly annotate phage genomes, identifying capsid genes, tail fibers, lytic enzymes, and lysogeny-related genes. Phages selected for therapy are strictly lytic to avoid horizontal gene transfer [

35].

Figure 5 expresses

Genomics-Informed Precision Phage Therapy Pipeline

Comparative Genomics and Host Range Prediction

Tools like PhageAI and HostPhinder predict host range by analyzing tail fiber genes, codon usage, and structural motifs. These methods accelerate candidate phage identification without lengthy wet-lab screening [

36].

CRISPR–Phage Co-Evolution

Bacterial CRISPR arrays serve as memory banks of prior phage infections. In turn, phages evolve via target mutations or acquire anti-CRISPR (Acr) proteins to evade immunity [

37].

Synthetic Genome Engineering

Using lambda red recombineering and CRISPR-based editing, researchers can reprogram phages by deleting lysogeny genes, inserting payloads, or altering host tropism [

38].

Toward Personalization

A growing clinical pipeline allows for patient-specific pathogen sequencing, phage matching, and treatment in under a week. This forms the basis for scalable, precision phage therapy [

39].

Conclusion and Outlook

Bacteriophages are no longer just biological oddities—they are chemically programmable tools engineered for precision. Their modular architecture, catalytic enzymes, and genetic tractability support the development of targeted, resistance-proof therapies.

This review has demonstrated how modern chemistry, structural biology, and genomics converge to position phages as next-generation antimicrobials.

Recommendations:

Prioritize collaboration between chemists, structural biologists, and microbiologists.

Frame phage therapy as a modular chemical approach—not a fallback.

Build curated libraries of phage structures and enzyme domains.

Push for regulatory pathways tailored to customizable biologics.

Integrate AI-driven selection and genomic matching into therapy design.

Phages offer a promising solution in the fight against antimicrobial resistance-precise, programmable, and personalized.

References

- Lee JH, Shin H, Ryu S. Bacteriophage-based antimicrobials and their potential use against multidrug-resistant bacteria. J Microbiol. 2022;60(2):91–98.

- Oduor JMO, Mabrouk MS, Elbadawy HM, et al. Bacteriophage therapy: a promising alternative in the age of antimicrobial resistance. Front Pharmacol. 2022;13:872816.

- Lu TK, Chan BK, Sahay G. Advances in the engineering of phages and their applications in medicine. Trends Biotechnol. 2023;41(1):24–38.

- Li X, Li X, Bai X, et al. Tail fiber engineering of phages to alter host specificity. Biotechnol Adv. 2023;62:108061.

- Witte AK, Fieseler L. Lysis mechanisms of bacteriophages. Viruses. 2023;15(3):726.

- Alsaadi EA, Alsaedi MH, Almalki MA, et al. Structural insights into endolysin–peptidoglycan interactions. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23(9):5106.

- Nam KH, Kim MS, Lee K, et al. PEGylation improves pharmacokinetics and therapeutic efficacy of phage-based therapies. Pharmaceutics. 2022;14(5):980.

- Akello J, Udaondo Z, Ross A, et al. Genomic insights into phage–host specificity. Microorganisms. 2022;10(4):679.

- Abdelkader K, Knecht LE, Bayer A, et al. Machine learning for personalized bacteriophage therapy. Nat Biotechnol. 2023;41(4):464–475.

- Shen Y, Wang D, Zhao Y, et al. Modular architecture and structural diversity of tailed bacteriophages. Microbiol Spectr. 2022;10(6):e01633–22.

- Persson T, Leung CY, O’Connell K, et al. Supramolecular principles in phage capsid assembly. ACS Nano. 2023;17(1):131–142.

- Batra H, Konieczny A. Internal pressure in viral capsids: lessons from phage DNA packaging. Viruses. 2022;14(9):1994.

- Vos M, Louwen R, Kropinski AM, et al. Phage tail contraction and genome injection mechanisms. Trends Microbiol. 2023;31(5):389–398.

- Ogilvie LA, Jones BV. Host recognition strategies in phage infection. Curr Opin Virol. 2022;54:101237.

- Ceyssens PJ, Lavigne R. Phage structural protein scaffolding and self-assembly. Front Microbiol. 2022;13:865229.

- Li F, Zhou W, Liang Y, et al. Phage–bacteria interface: binding, injection, and beyond. Microbiol Res. 2022;261:127042.

- Niu Y, Xu M, Liu Y, et al. Molecular modeling of phage tail fiber interactions. Comput Struct Biotechnol J. 2023;21:2223–2233.

- Murthy D, Podgorski J, Grayson P, et al. Mechanics of phage DNA injection under high pressure. Biophys J. 2022;121(4):785–793.

- Zhang Y, Wang Y, Zhu Z, et al. Catalytic profiling of phage endolysins. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2022;603:104–110.

- Doss J, Culbertson K, Hahn D, Camacho J. Chemical insights into timed lysis in phage therapy. Antibiotics. 2022;11(7):920.

- Gu J, Xu W, Lei L, et al. Advances in engineering lytic enzymes. Viruses. 2023;15(2):456.

- Lopes A, Oliveira H, Melo LDR, et al. Domain-specific activity of bacteriophage-derived endolysins. Microorganisms. 2022;10(3):521.

- Turner D, Topka G, Haggard-Ljungquist E. Structure–function of lytic phage enzymes. Front Microbiol. 2022;13:852323.

- Yin Y, Liu X, Zhao J, et al. Holins and spanins in Gram-negative lysis. Viruses. 2023;15(4):766.

- Ghosh D, Bhattacharya D. Synthetic holins and peptide analogues. ACS Synth Biol. 2023;12(2):317–325.

- Chen Y, Zhang C, Ma Y, et al. Chemical modification of phage capsids for precision delivery. ACS Chem Biol. 2023;18(3):524–534.

- Arndt D, Suh JW, Ryu J. PEGylation enhances phage longevity in systemic circulation. Nanomedicine. 2022;40:102504.

- Derda R, Tang SKY, Whitesides GM. Phage display for bacterial targeting. Bioconjug Chem. 2023;34(1):78–86.

- Ramesh N, Haldar S, Pillai S, et al. Phage–nanoparticle hybrids for antimicrobial applications. J Nanobiotechnology. 2022;20(1):248.

- Fernández-Ruiz I, Brown R, Marwick C, et al. Synthetic phages for targeted bacterial killing. Nat Chem Biol. 2024;20(2):142–152.

- Law N, Logan C, Yung G, et al. Clinical evidence for personalized phage therapy. Clin Infect Dis. 2023;76(8):1367–1375.

- Baker JL, Ma L, Kim M, et al. Anti-biofilm phage hydrogels and delivery systems. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2023;15(7):9333–9345.

- Kim S, Jung J, Kim M, et al. Targeted phage delivery of CRISPR and antibiotics. Mol Ther. 2022;30(9):3119–3132.

- Tan D, Zhang Y, Ruan L, et al. Regulatory outlook on phage therapeutics. Trends Biotechnol. 2023;41(6):707–719.

- Jahn M, Bunk B, Schildkraut J, et al. Genomic annotation and biosafety of therapeutic phages. Microbiol Spectr. 2022;10(4):e00284-22.

- Rhoads DD, Wolcott RD, Kuskowski MA, et al. Host range prediction using AI-assisted phage tools. NPJ Biofilms Microbiomes. 2023;9(1):30.

- Díaz-Muñoz SL, Koskella B. Phage–CRISPR coevolution in the wild. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2022;66:25–31.

- Pinto R, Silva YJ, Costa L, et al. Genome editing and lysogeny control in synthetic phages. Viruses. 2022;14(11):2395.

- Kutter E, Debarbieux L. Toward precision phage therapy in the clinic. Microbiol Spectr. 2023;11(1):e03538-22.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).