Submitted:

26 July 2025

Posted:

28 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Related Work

3. Fundamental Theory

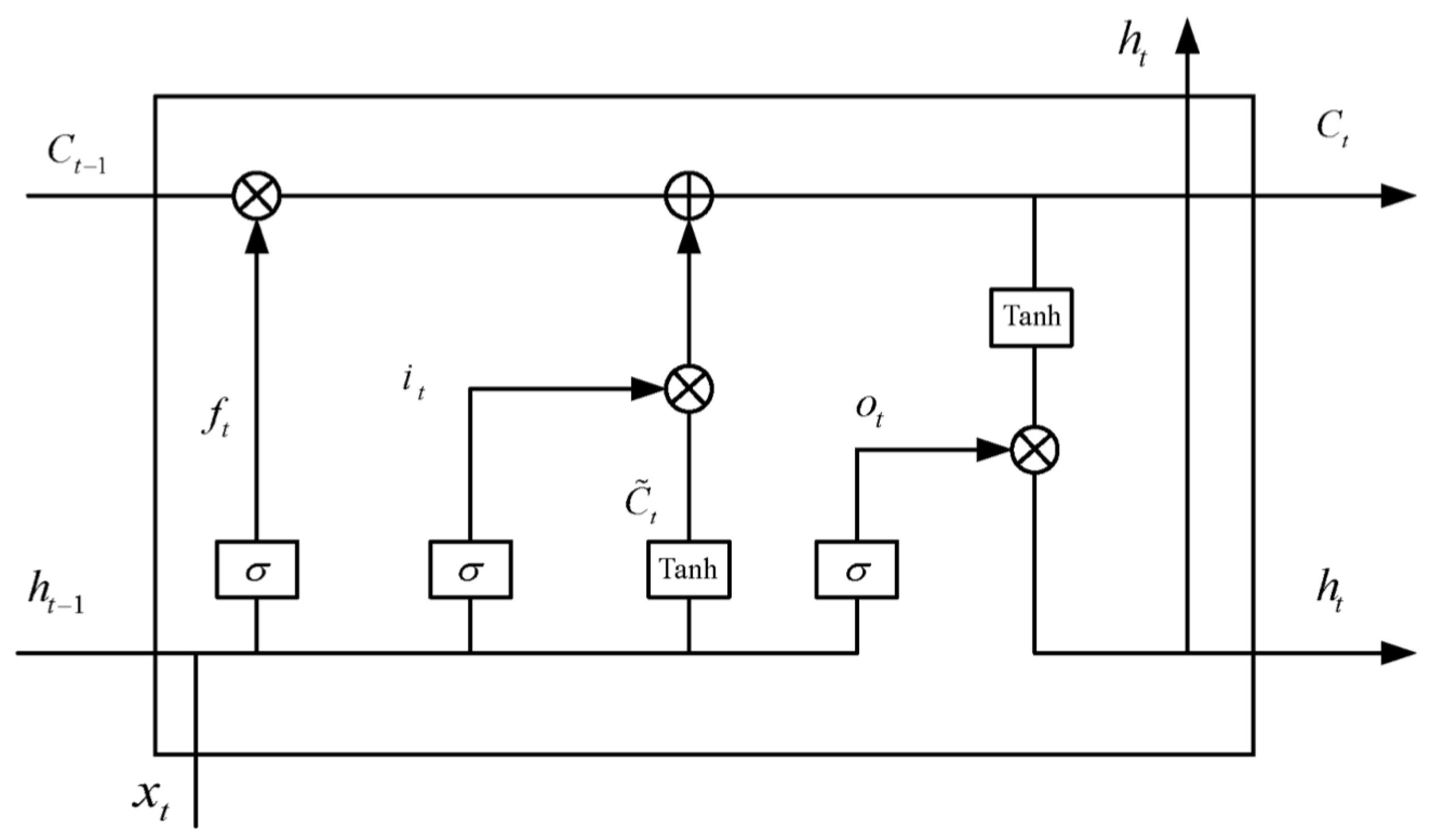

3.1. Bi-LSTM

- : cell state at time t

- : input at time t

- : forget gate

- : input gate

- : output gate

- : input sequence

- : activation function

- : hidden state at time t

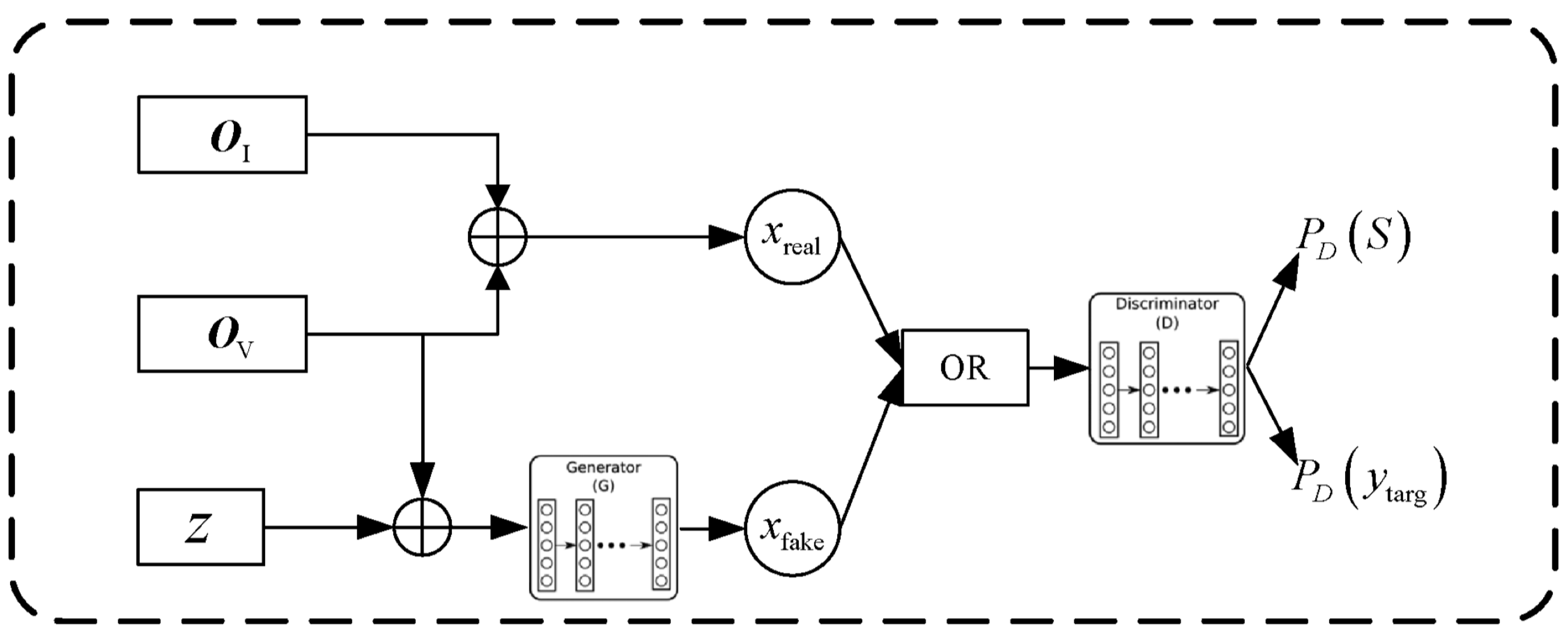

3.2. Generative Adversarial Network and Convolutional Neural Network

- x: real sample,

- z: latent variable,

- P: probability distribution,

- : expectation.

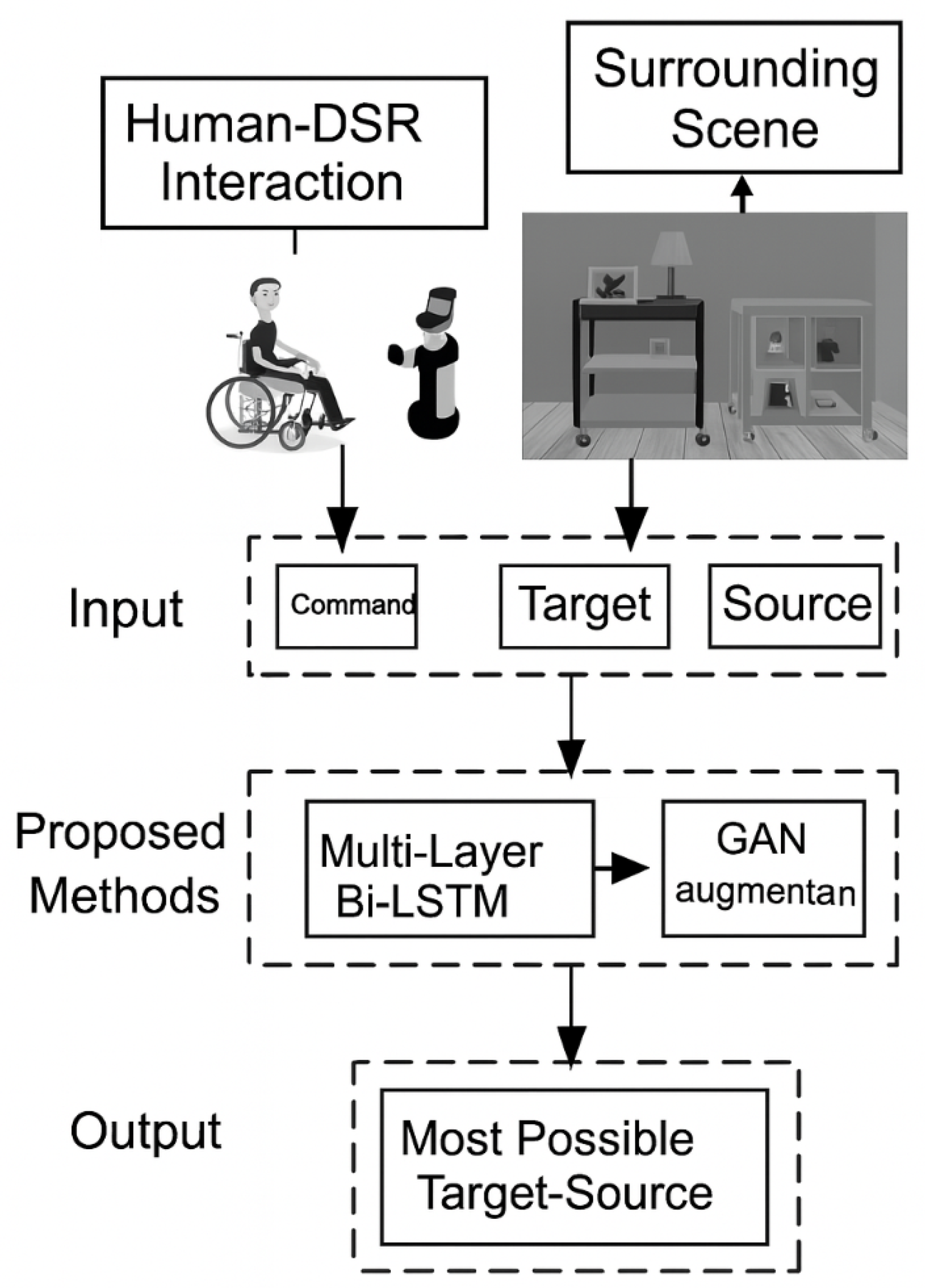

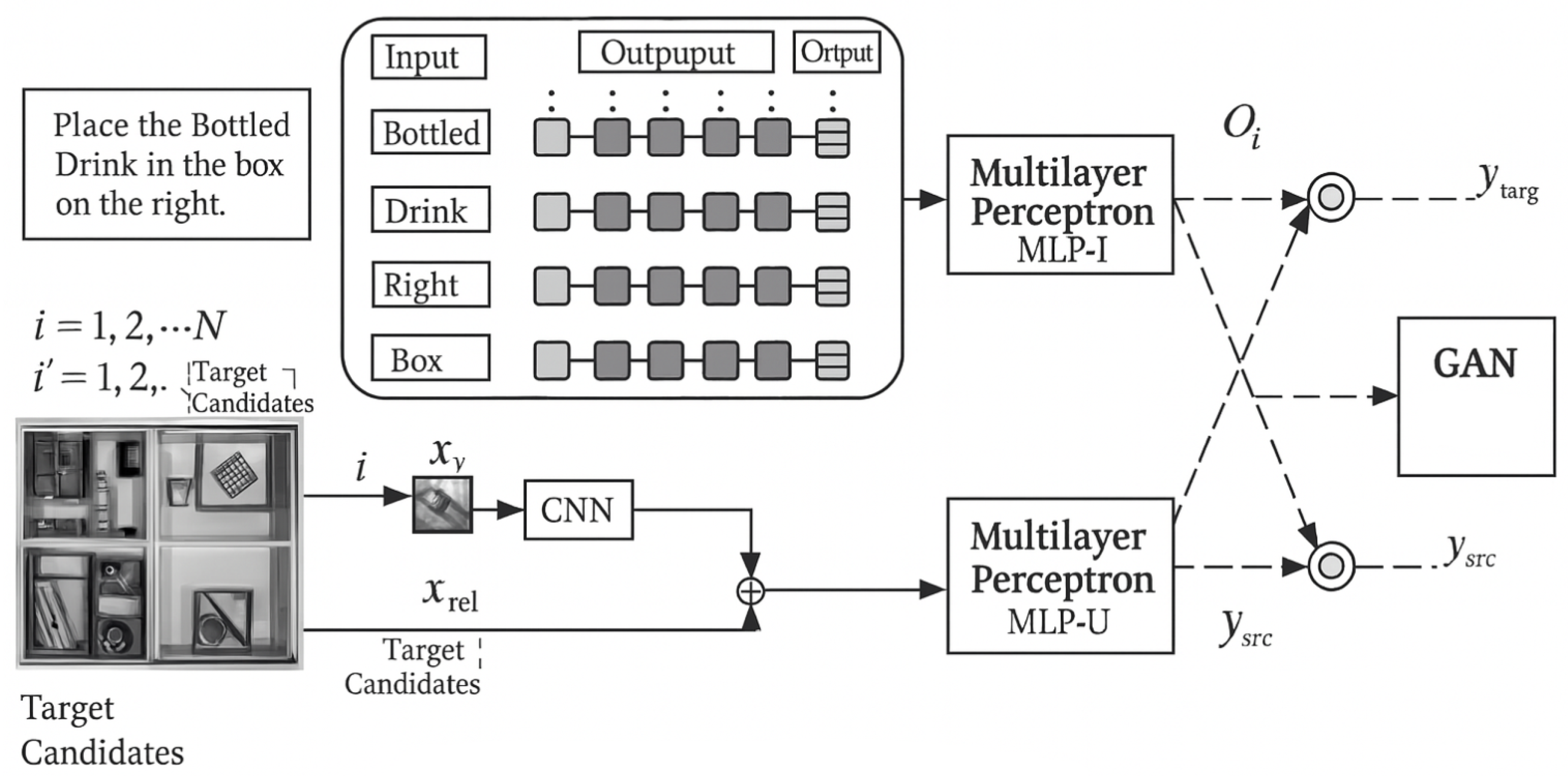

4. Multimodal Natural Language Understanding Method Based on Hybrid Deep Learning

5. Experiments and Result Analysis

5.1. Parameter Settings

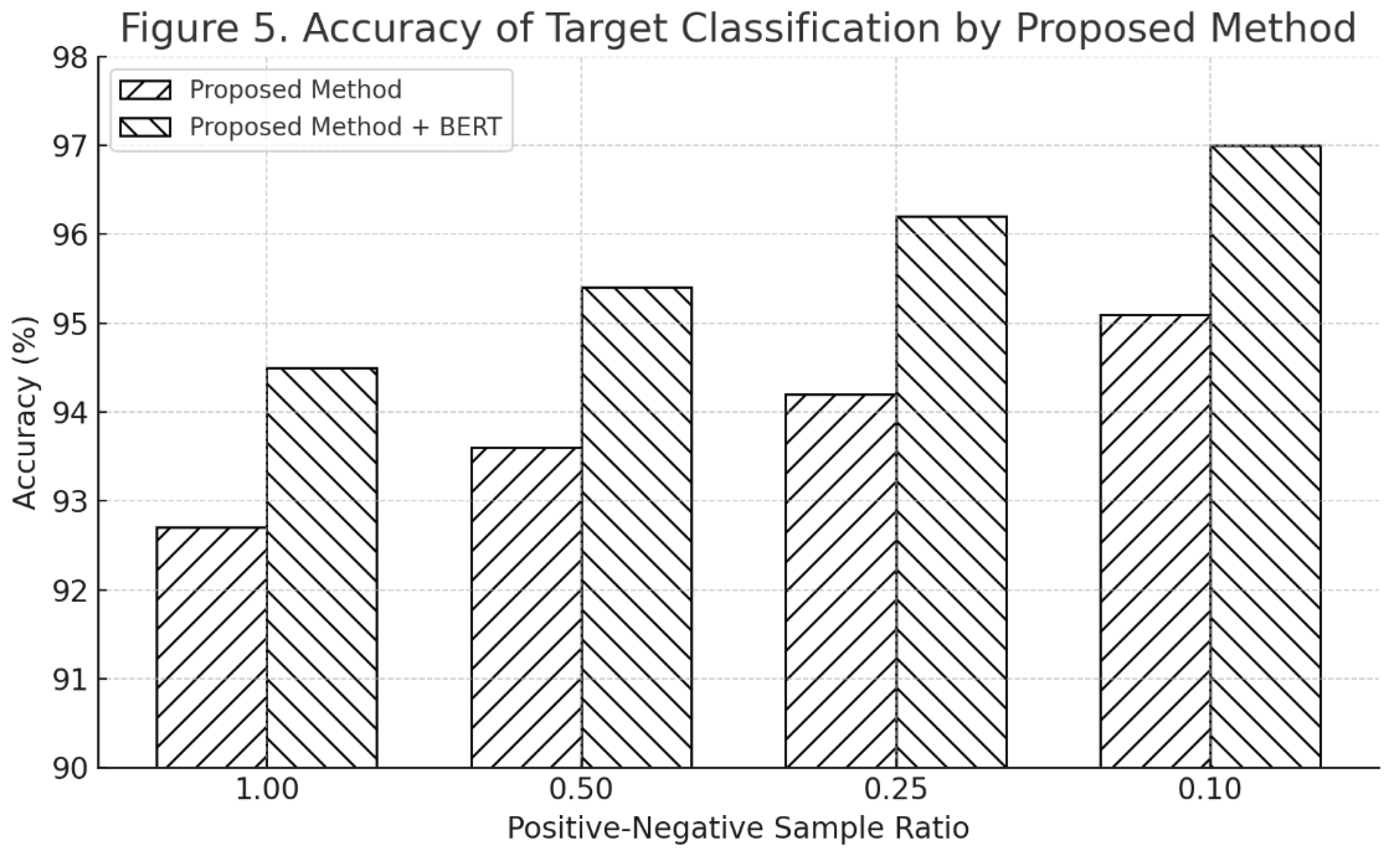

5.2. Evaluation on PFN-PIC Dataset

5.3. Comparison with Baselines

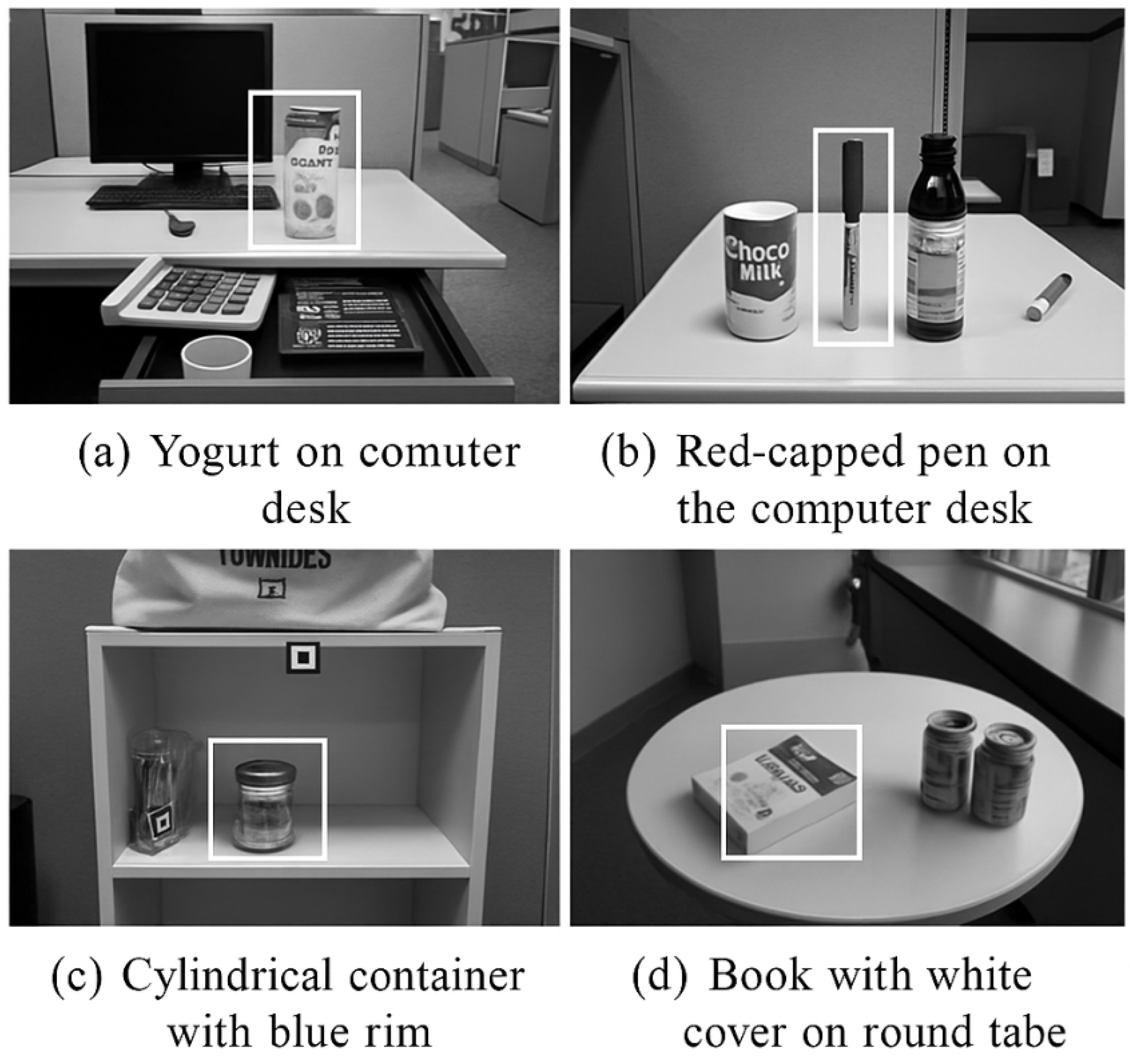

5.4. Prediction Examples and Efficiency

6. Conclusions

References

- Portner, P., Pak, M., & Zanuttini, R. (2019). The speaker-addressee relation at the syntax-semantics interface. Language, 95(1), 1–36. [CrossRef]

- Saini, R., Roy, P. P., & Dogra, D. P. (2018). A segmental HMM based trajectory classification using genetic algorithm. Expert Systems with Applications, 93, 169–181. [CrossRef]

- Li, W., Wen, L., Chang, M. C., et al. (2017). Adaptive RNN tree for large-scale human action recognition. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision (pp. 1444–1452).

- Fok, W. W. T., Chan, L. C. W., & Chen, C. (2018). Artificial intelligence for sport actions and performance analysis using Recurrent Neural Network (RNN) with Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM). In Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Robotics and Artificial Intelligence (pp. 40–44).

- Kunze, L., Hawes, N., Duckett, T., et al. (2018). Artificial intelligence for long-term robot autonomy: A survey. IEEE Robotics and Automation Letters, 3(4), 4023–4030. [CrossRef]

- Scalise, R., Li, S., Admoni, H., et al. (2018). Natural language instructions for human-robot collaborative manipulation. The International Journal of Robotics Research, 37(6), 558–565. [CrossRef]

- Chao, G. L., Hu, C. C., Liu, B., et al. (2019). Audio-visual TED corpus: Enhancing the TED-LIUM corpus with facial information, contextual text and object recognition. In Proceedings of the 2019 ACM International Joint Conference on Pervasive and Ubiquitous Computing and 2019 ACM International Symposium on Wearable Computers (pp. 468–473).

- Zhu, S., Lan, O., & Yu, K. (2018). Robust spoken language understanding with unsupervised ASR-error adaptation. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP) (pp. 6179–6183).

- Kawahara, T. (2019). Spoken dialogue system for a human-like conversational robot ERICA. In Proceedings of the 9th International Workshop on Spoken Dialogue System Technology (pp. 65–75).

- Gallé, M., Kynev, E., Monet, N., et al. (2017). Context-aware selection of multi-modal conversational fillers in human-robot dialogues. In Proceedings of the 26th IEEE International Symposium on Robot and Human Interactive Communication (RO-MAN) (pp. 317–322).

- Xu, H., Liu, Y., & Sun, Y. (2019). Syntax-aware attention mechanism for neural machine translation. Neurocomputing, 361, 195–205.

- Sun, X., Duan, Y., Deng, Y., Guo, F., Cai, G., & Peng, Y. (2025, March). Dynamic operating system scheduling using double DQN: A reinforcement learning approach to task optimization. In 2025 8th International Conference on Advanced Algorithms and Control Engineering (ICAACE) (pp. 1492–1497). IEEE.

- Xu, T., Xiang, Y., Du, J., & Zhang, H. (2025). Cross-Scale Attention and Multi-Layer Feature Fusion YOLOv8 for Skin Disease Target Detection in Medical Images. Journal of Computer Technology and Software, 4(2).

- Zhang, Y., Liu, J., Wang, J., Dai, L., Guo, F., & Cai, G. (2025). Federated learning for cross-domain data privacy: A distributed approach to secure collaboration. arXiv preprint arXiv:2504.00282.

- Guo, X., Wu, Y., Xu, W., Liu, Z., Du, X., & Zhou, T. (2025). Graph-Based Representation Learning for Identifying Fraud in Transaction Networks.

- Xu, Z., Bao, Q., Wang, Y., Feng, H., Du, J., & Sha, Q. (2025). Reinforcement Learning in Finance: QTRAN for Portfolio Optimization. Journal of Computer Technology and Software, 4(3).

- Peng, Y., Wang, Y., Fang, Z., Zhu, L., Deng, Y., & Duan, Y. (2025, March). Revisiting LoRA: A Smarter Low-Rank Approach for Efficient Model Adaptation. In 2025 5th International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Industrial Technology Applications (AIITA) (pp. 1248–1252). IEEE.

- Liu, J. (2025, March). Global Temporal Attention-Driven Transformer Model for Video Anomaly Detection. In 2025 5th International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Industrial Technology Applications (AIITA) (pp. 1909–1913). IEEE.

- Lou, Y., Liu, J., Sheng, Y., Wang, J., Zhang, Y., & Ren, Y. (2025, March). Addressing Class Imbalance with Probabilistic Graphical Models and Variational Inference. In 2025 5th International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Industrial Technology Applications (AIITA) (pp. 1238–1242). IEEE.

- Cheng, Y. (2025). Multivariate time series forecasting through automated feature extraction and transformer-based modeling. Journal of Computer Science and Software Applications, 5(5).

- Duan, Y. (2024). Continuous Control-Based Load Balancing for Distributed Systems Using TD3 Reinforcement Learning. Journal of Computer Technology and Software, 3(6).

- Dai, L., Zhu, W., Quan, X., Meng, R., Chai, S., & Wang, Y. (2025). Deep Probabilistic Modeling of User Behavior for Anomaly Detection via Mixture Density Networks. arXiv preprint arXiv:2505.08220.

- Lou, Y. (2024). Capsule Network-Based AI Model for Structured Data Mining with Adaptive Feature Representation. Transactions on Computational and Scientific Methods, 4(9).

- Zhan, J. (2024). MobileNet Compression and Edge Computing Strategy for Low-Latency Monitoring. Journal of Computer Science and Software Applications, 4(4).

- Peng, Y. (2024). Structured Knowledge Integration and Memory Modeling in Large Language Systems. Transactions on Computational and Scientific Methods, 4(10).

- Lou, Y. (2024). RT-DETR-Based Multimodal Detection with Modality Attention and Feature Alignment. Journal of Computer Technology and Software, 3(5).

- Liu, J. (2025). Reinforcement Learning-Controlled Subspace Ensemble Sampling for Complex Data Structures.

- Liu, X., Xu, Q., Ma, K., Qin, Y., & Xu, Z. (2025). Temporal Graph Representation Learning for Evolving User Behavior in Transactional Networks.

- Wei, M., Xin, H., Qi, Y., Xing, Y., Ren, Y., & Yang, T. (2025). Analyzing data augmentation techniques for contrastive learning in recommender models.

- Liu, X., Qin, Y., Xu, Q., Liu, Z., Guo, X., & Xu, W. (2025). Integrating Knowledge Graph Reasoning with Pretrained Language Models for Structured Anomaly Detection.

- Ma, Y., Cai, G., Guo, F., Fang, Z., & Wang, X. (2025). Knowledge-Informed Policy Structuring for Multi-Agent Collaboration Using Language Models. Journal of Computer Science and Software Applications, 5(5).

- He, Q., Liu, C., Zhan, J., Huang, W., & Hao, R. (2025). State-Aware IoT Scheduling Using Deep Q-Networks and Edge-Based Coordination. arXiv preprint arXiv:2504.15577.

- Jiang, N., Zhu, W., Han, X., Huang, W., & Sun, Y. (2025). Joint Graph Convolution and Sequential Modeling for Scalable Network Traffic Estimation. arXiv preprint arXiv:2505.07674.

- Wang, Y., Tang, T., Fang, Z., Deng, Y., & Duan, Y. (2025). Intelligent Task Scheduling for Microservices via A3C-Based Reinforcement Learning. arXiv preprint arXiv:2505.00299.

- Xing, Y., Wang, Y., & Zhu, L. (2025). Sequential Recommendation via Time-Aware and Multi-Channel Convolutional User Modeling. Transactions on Computational and Scientific Methods, 5(5).

- Han, X., Sun, Y., Huang, W., Zheng, H., & Du, J. (2025). Towards Robust Few-Shot Text Classification Using Transformer Architectures and Dual Loss Strategies. arXiv preprint arXiv:2505.06145.

- Zhang, T., Shao, F., Zhang, R., Zhuang, Y., & Yang, L. (2025). DeepSORT-Driven Visual Tracking Approach for Gesture Recognition in Interactive Systems. arXiv preprint arXiv:2505.07110.

- Wu, Y., Qin, Y., Su, X., & Lin, Y. (2025). Transformer-Based Risk Monitoring for Anti-Money Laundering with Transaction Graph Integration.

- Yang, T. (2024). Transferable Load Forecasting and Scheduling via Meta-Learned Task Representations. Journal of Computer Technology and Software, 3(8).

- Wei, M. (2024). Federated Meta-Learning for Node-Level Failure Detection in Heterogeneous Distributed Systems. Journal of Computer Technology and Software, 3(8).

- Xin, H., & Pan, R. (2025). Unsupervised anomaly detection in structured data using structure-aware diffusion mechanisms. Journal of Computer Science and Software Applications, 5(5).

- Cheng, Y. (2024). Selective Noise Injection and Feature Scoring for Unsupervised Request Anomaly Detection. Journal of Computer Technology and Software, 3(9).

- Wu, Y., Lin, Y., Xu, T., Meng, X., Liu, H., & Kang, T. (2025). Multi-Scale Feature Integration and Spatial Attention for Accurate Lesion Segmentation.

- Gao, D. (2025). Deep Graph Modeling for Performance Risk Detection in Structured Data Queries. Journal of Computer Technology and Software, 4(5).

- Guo, F., Zhu, L., Wang, Y., & Cai, G. (2025). Perception-Guided Structural Framework for Large Language Model Design. Journal of Computer Technology and Software, 4(5).

- Zhu, L., Cui, W., Xing, Y., & Wang, Y. (2024). Collaborative Optimization in Federated Recommendation: Integrating User Interests and Differential Privacy. Journal of Computer Technology and Software, 3(8).

- Wang, S., Zhuang, Y., Zhang, R., & Song, Z. (2025). Capsule Network-Based Semantic Intent Modeling for Human-Computer Interaction. arXiv preprint arXiv:2507.00540.

- Wu, Q. (2024). Task-Aware Structural Reconfiguration for Parameter-Efficient Fine-Tuning of LLMs. Journal of Computer Technology and Software, 3(6).

- Zou, Y., Qi, N., Deng, Y., Xue, Z., Gong, M., & Zhang, W. (2025). Autonomous Resource Management in Microservice Systems via Reinforcement Learning. arXiv preprint arXiv:2507.12879.

- Gong, M. (2025). Modeling Microservice Access Patterns with Multi-Head Attention and Service Semantics. Journal of Computer Technology and Software, 4(6).

- Quan, X. (2024). Layer-Wise Structural Mapping for Efficient Domain Transfer in Language Model Distillation. Transactions on Computational and Scientific Methods, 4(5).

- Ren, Y. (2024). Deep Learning for Root Cause Detection in Distributed Systems with Structural Encoding and Multi-modal Attention. Journal of Computer Technology and Software, 3(5).

- Wang, H. (2024). Causal Discriminative Modeling for Robust Cloud Service Fault Detection. Journal of Computer Technology and Software, 3(7).

- Xu, T., Deng, X., Meng, X., Yang, H., & Wu, Y. (2025). Clinical NLP with Attention-Based Deep Learning for Multi-Disease Prediction. arXiv preprint arXiv:2507.01437.

- Meng, X., Wu, Y., Tian, Y., Hu, X., Kang, T., & Du, J. (2025). Collaborative Distillation Strategies for Parameter-Efficient Language Model Deployment. arXiv preprint arXiv:2507.15198.

- Lyu, S., Deng, Y., Liu, G., Qi, Z., & Wang, R. (2025). Transferable Modeling Strategies for Low-Resource LLM Tasks: A Prompt and Alignment-Based. arXiv preprint arXiv:2507.00601.

- Zhang, X., & Wang, X. (2025). Domain-Adaptive Organ Segmentation through SegFormer Architecture in Clinical Imaging. Transactions on Computational and Scientific Methods, 5(7).

| Method | Parameters |

|---|---|

| Bi-LSTM | 3 layers, 1024 cells |

| MLP (MLP-I, MLP-V) | 1024, 1024, 1024 nodes |

| MLP (MLP-U) | 2048, 1024, 128 nodes |

| GAN | Learning rate: 0.0002, |

| Generator G: 100, 100, 100, 100 nodes | |

| Discriminator D: 100, 200, 400, 1000 nodes | |

| Batch size: 64 |

| Method | Target Accuracy (%) | Source Accuracy (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1.0 | 0.5 | 0.25 | 0.1 | 0.05 | ||

| Ref [12] | 93.3 | 94.1 | 94.8 | 95.7 | – | 97.9 |

| Ref [13] | 92.5 | 93.1 | 93.8 | 94.7 | – | – |

| Ref [14] | 92.9 | 93.4 | 94.3 | 95.1 | – | – |

| Ours + BERT | 94.5 | 95.4 | 96.1 | 96.9 | – | 99.8 |

| Method | Time (s) |

|---|---|

| Ref [12] | 117.61 |

| Ref [13] | 97.96 |

| Ref [14] | 128.03 |

| Ours + BERT | 147.12 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).