1. Introduction

Mesoscale eddy is transient yet intense mesoscale oceanic phenomena, accounting for the majority of kinetic energy in the ocean. They exhibit strong nonlinearity[

1] and play a significant role in the global transport and redistribution of oceanic mass and energy[

2], thereby influencing atmospheric responses[

3], climate variability, and interactions with other oceanic processes. The South China Sea (SCS), the largest and deepest semi-enclosed marginal sea in the western Pacific, is a region with frequent and abundant mesoscale eddy activity[

4], connected to the open ocean and adjacent seas through multiple straits[

5].

Previous studies have extensively investigated the characteristics of mesoscale eddies in the SCS, such as their spatial distribution, radius, amplitude, and other properties, using eddy detection methods based on flow fields and sea surface height data[

6]. However, since satellite altimeters can only capture surface information, analyzing the three-dimensional structure of mesoscale eddies relies on in-situ observations or numerical modeling. Underwater glider, a novel type of autonomous oceanographic instrument, is buoyancy-driven and capable of following preprogrammed paths while equipped with various sensors to collect temperature, conductivity, sound velocity, and other hydrographic data[

7]. They offer advantages such as extensive spatial coverage, long endurance, and high resolution. Currently, underwater gliders have been widely employed in observing mesoscale eddies and analyzing their three-dimensional structures. For instance, Qiu et al.[

8] tracked an anticyclonic eddy (AE) in the northern SCS using three gliders, revealing a lifespan of two months and an average radius of 70 km. Their study found that background currents induced asymmetries in the eddy’s shape, velocity, and heat distribution. Shu et al.[

9] combined glider and CTD data to investigate an AE in the SCS in 2017, demonstrating that its three-dimensional structure was strongly influenced by sloping topography. Qiu et al.[

10] observed an AE in the northern SCS from April to June 2018 using gliders, identifying submesoscale frontal structures ahead of the eddy and using numerical modeling to show that baroclinic processes dominated its deformation. Additionally, Li et al.[

11] designed a coordinated glider observation network to reconstruct the 3D structure of an AE in the northern SCS, analyzing its thermohaline characteristics and suggesting its possible generation through Kuroshio shedding.

The northern SCS is also a region frequently traversed by typhoons. Typhoon specifically refers to a tropical cyclone (TC) generated in the northwest Pacific Ocean, is an intense low-pressure weather system characterized by strong winds, heavy rainfall, and low atmospheric pressure, often causing significant destruction. Its powerful cyclonic wind field injects positive vorticity into the ocean while enhancing upper-ocean mixing[

12]. The intense disturbance induced by typhoons in the upper ocean can substantially influence the generation and evolution of mesoscale eddies, altering their shape, intensity, lifespan, and other properties, with the extent of impact depending on the typhoon’s path and strength[

13]. The effects of typhoons on mesoscale eddies vary depending on the eddy’s nature[

14]. Huang et al.[

15] investigated the impact of a typhoon on a dipole eddy pair and found that the typhoon caused asymmetry in the dipole structure. After the typhoon’s passage, internal interactions within the dipole eddy led to faster stabilization compared to an isolated eddy. When a typhoon interacts with a cyclonic eddy, the eddy tends to intensify[

16]. Post-typhoon, the cyclonic eddy exhibits increased amplitude and rotational speed, resulting in enhanced kinetic energy, an expanded radius, and altered shape[

17]. Vertically, the combined upwelling induced by both the cyclonic eddy and the typhoon strengthens surface cooling and enhances vertical material transport[

18]. In contrast, the influence of typhoons on AEs is generally opposite to that on cyclonic eddies. The changes in upper-ocean currents and density structure induced by typhoons can weaken or even dissipate AEs[

19]. The warm-core anomaly of AEs may intensify passing typhoons, while typhoon-induced upwelling counteracts the eddy’s downward flow, leading to a slight temperature reduction near the eddy. However, stronger AEs can retain their structure, establishing a negative feedback mechanism between the eddy and the typhoon[

20]. In terms of amplitude, absolute vorticity, and radius, AEs generally exhibit weakening trends, accompanied by significant losses in heat[

21] and kinetic energy.

This study primarily employs observational data and numerical modeling to analyze the three-dimensional structural characteristics of an AE generated near the Luzon Strait in June 2017 and its variations under typhoon influence.

Section 1 investigates the evolution process and fundamental characteristics of the AE based on satellite altimeter data.

Section 2 utilizes underwater glider observations to analyze the vertical thermohaline structure of the eddy and its response process to Typhoon Hato.

Section 3 conducts a comparative analysis of the eddy's response under typhoon and non-typhoon conditions using the Regional Ocean Modeling System (ROMS).

4. Conclusions

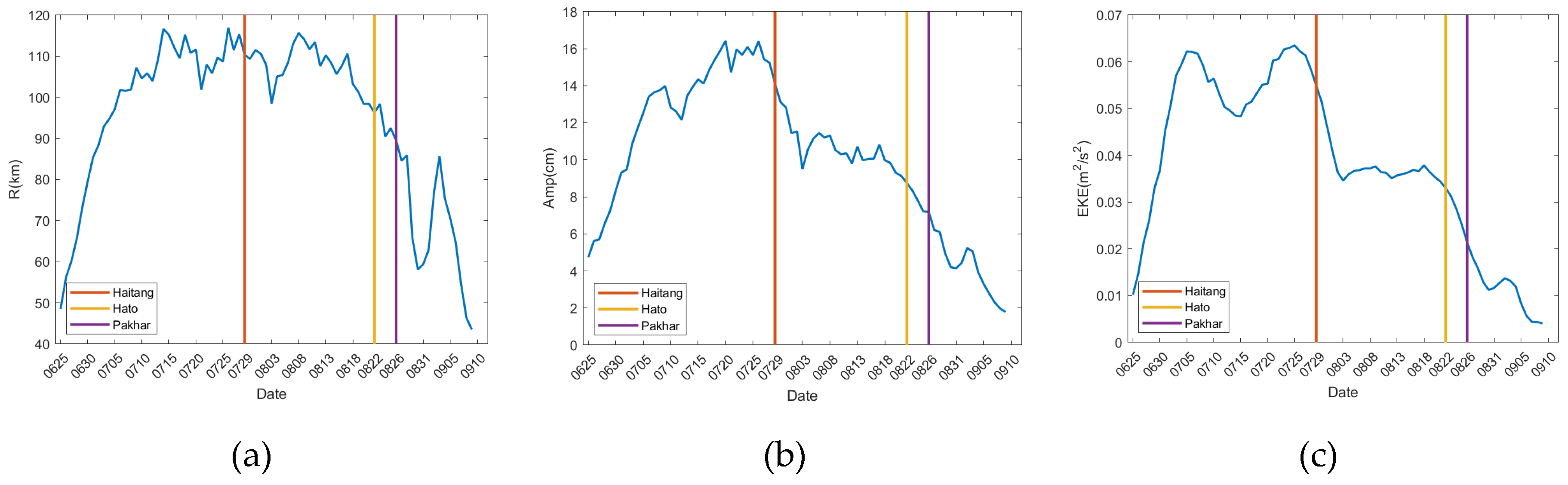

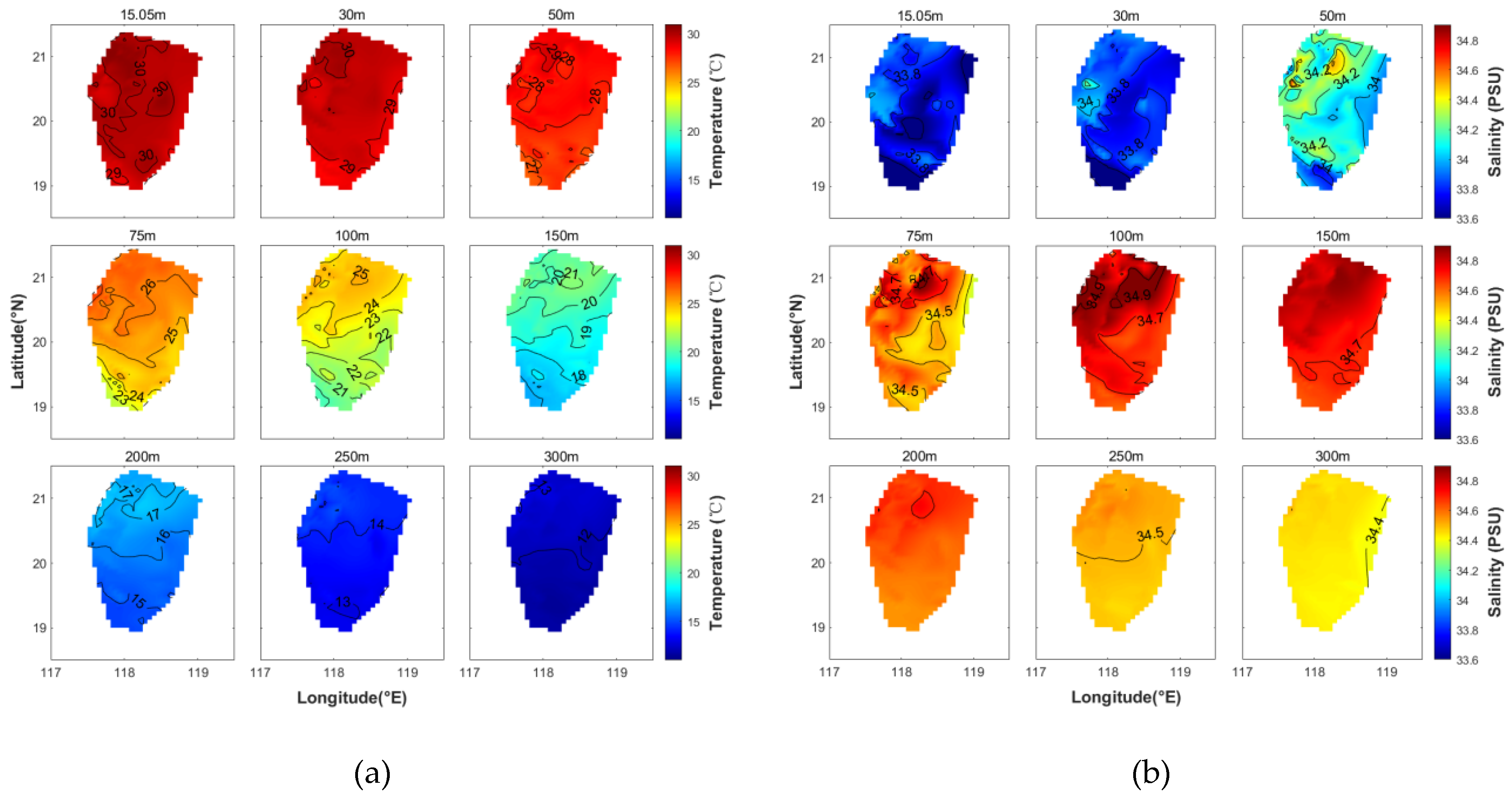

In this study, we identified and analyzed an AE in the northern SCS southwest of Taiwan in August 2017 by combining underwater glider observations with satellite altimetry data. The eddy, which originated at the Luzon Strait on June 25, 2017, was captured by the "Petrel II" underwater glider from August 4 to 29. The glider-derived temperature and salinity data revealed a well-defined high-temperature, high-salinity core near 118.5°E, 20.5°N, consistent with the eddy location identified from satellite altimetry. Vertical profiles showed that the core intensified from the surface to 100 m depth, as indicated by denser isopleths, and gradually weakened below 100 m, though horizontal high-temperature and high-salinity anomalies persisted throughout the eddy. Notably, the maximum temperature (2.86°C) and salinity (0.65 PSU) differences between the eddy center and periphery occurred near 100 m depth rather than at the surface, with a distinct high-salinity zone (>34.7 PSU) embedded within the eddy.

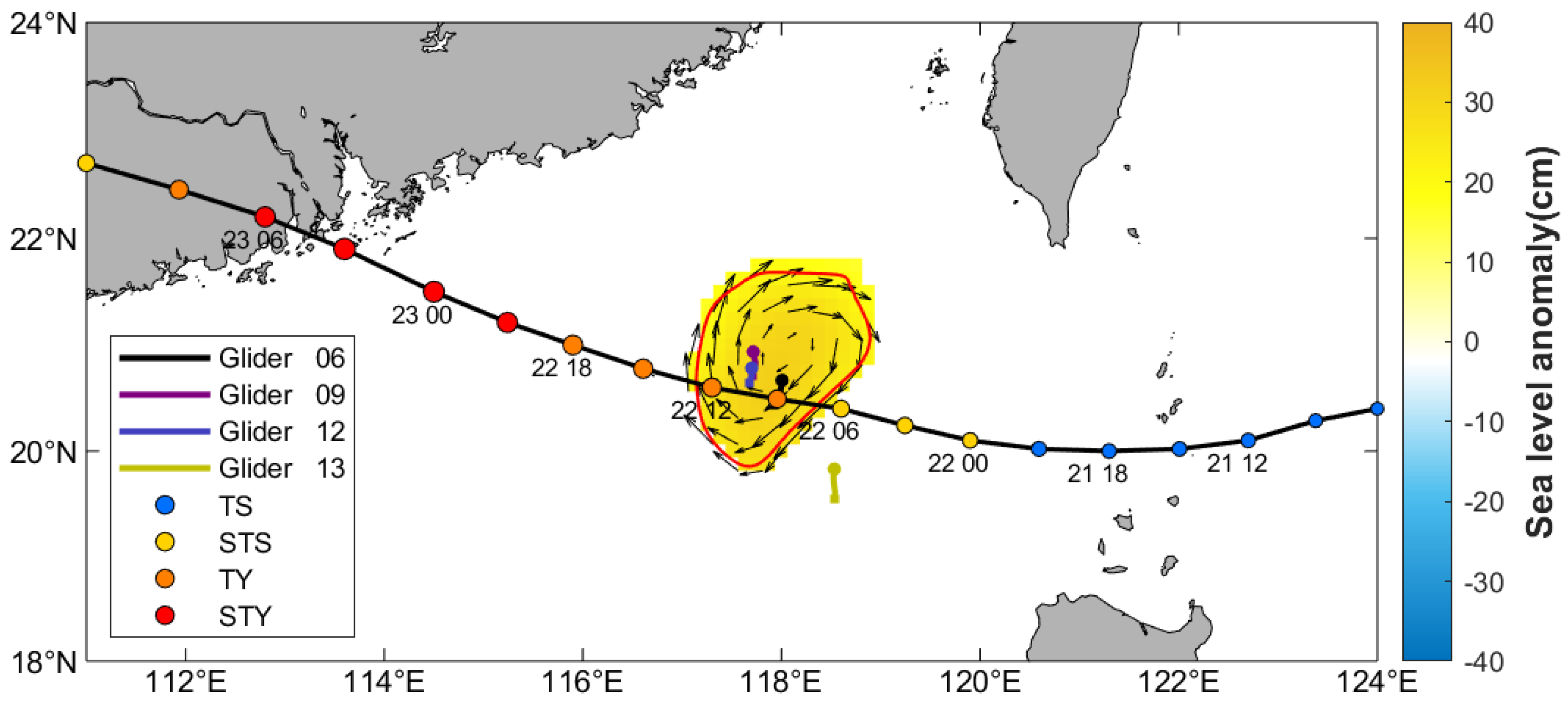

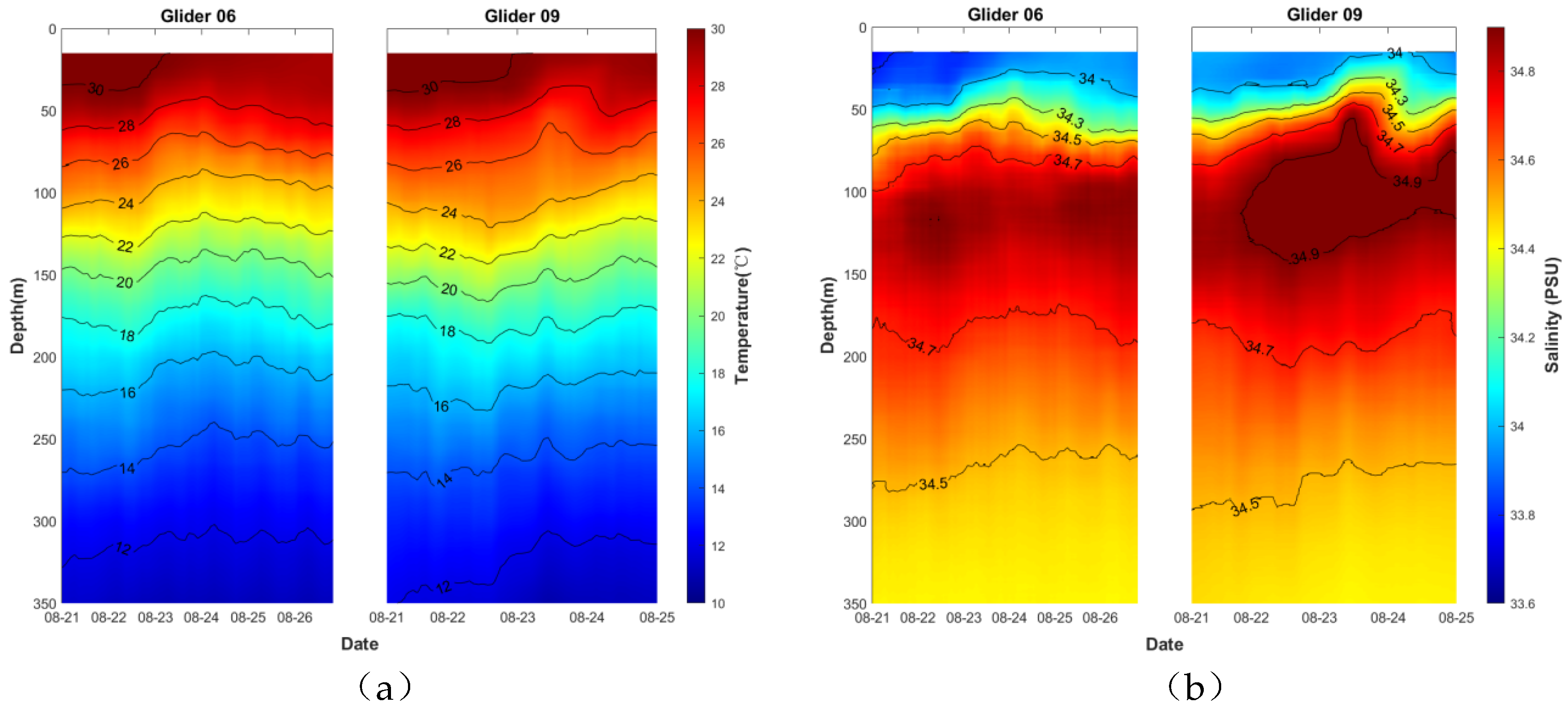

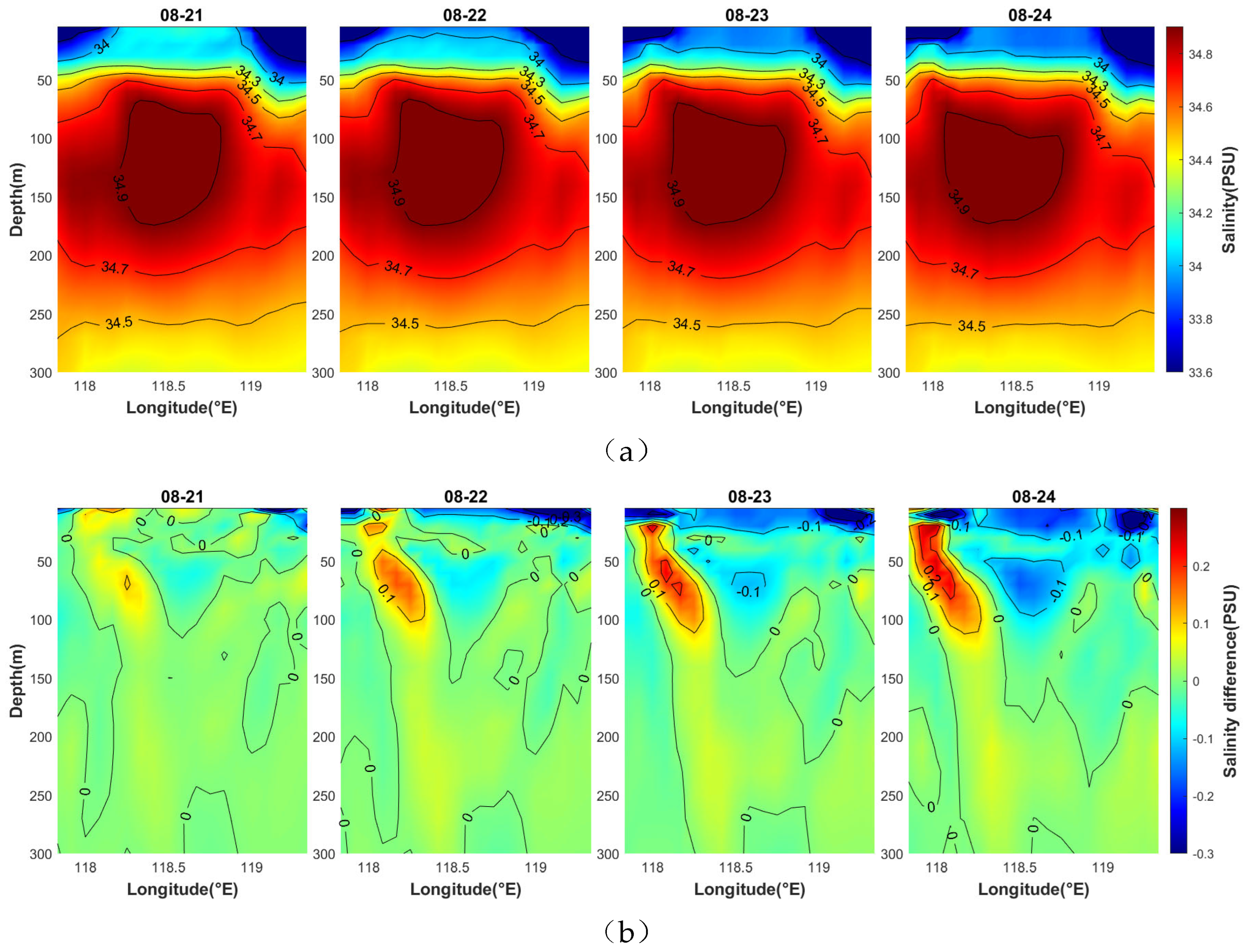

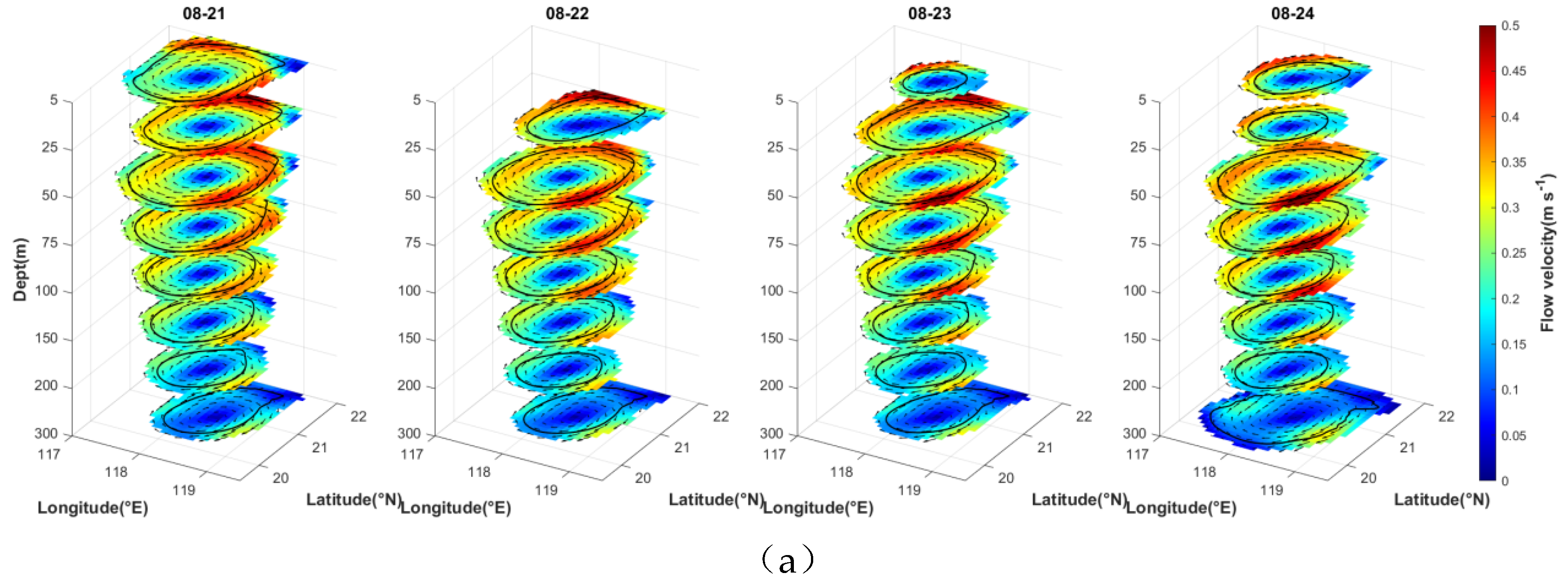

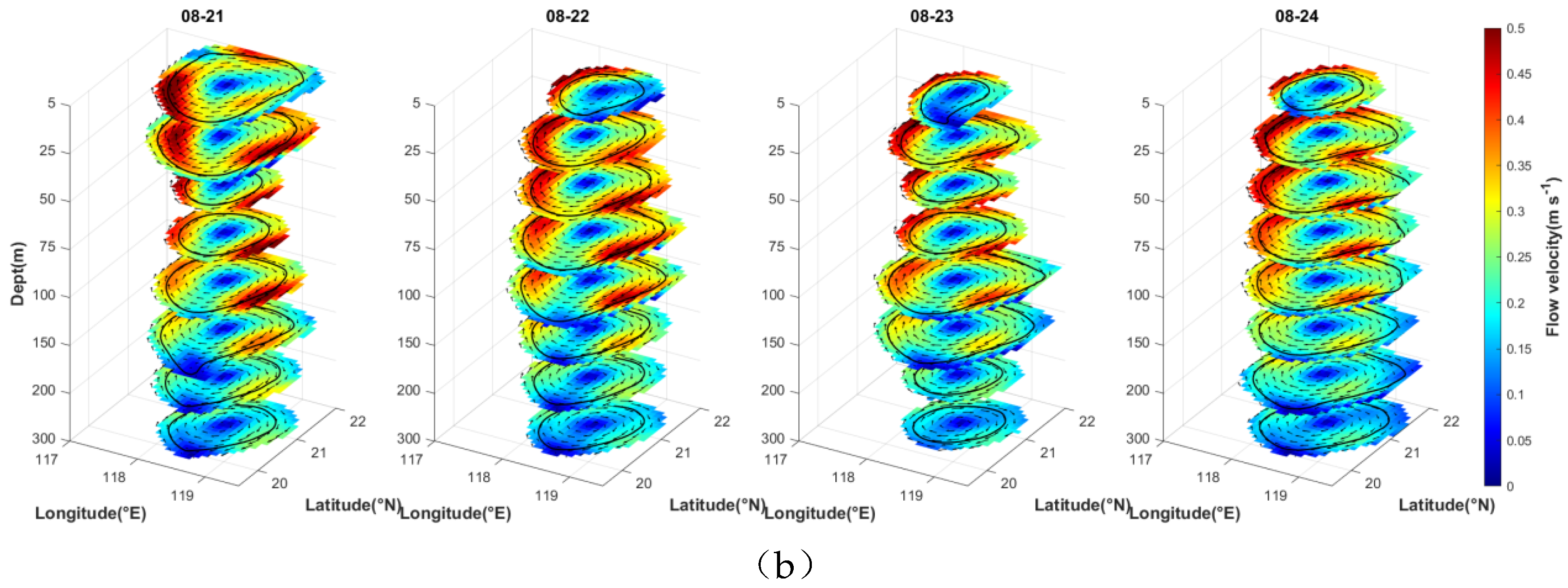

During the passage of Typhoon Hato (August 21–23), Gliders No. 6 and No. 9 recorded significant modifications in the eddy’s thermal-saline structure. Three days prior to the typhoon’s arrival, uplifted isotherms and isohalines indicated typhoon-induced upwelling. Detailed analysis of Glider No. 6 data demonstrated that the most pronounced cooling (>2°C) and salinification (>0.2 PSU) occurred at 50 m depth on the second day after typhoon arrival. While anomalies below ~30 m depth gradually recovered, those in the upper 30 m persisted. By day 5 post-typhoon, the upper layer (0–50 m) exhibited cooler temperatures and higher salinities compared to pre-typhoon conditions, whereas the 50–100 m layer showed warmer temperatures and lower salinities. Below 100 m, conditions largely reverted to pre-typhoon states, accompanied by a significantly deepened mixed layer. These findings highlight a 1–2 day lag in the typhoon’s impact on vertical thermal-saline structure, followed by a 4–5 day recovery period, except for the persistently altered mixed layer.

Numerical experiments using the ROMS model corroborated the observational results. The simulations revealed maximum typhoon-induced cooling at 50–100 m depth, with a 1–2 day delay relative to wind forcing, alongside surface salinification. During typhoon passage, kinetic energy at the eddy initially increased before decreasing, absolute vorticity declined, and upper-layer upwelling intensified abruptly. While the surface anticyclonic flow structure was disrupted, the eddy’s structure below 50 m remained resilient. Post-typhoon, the surface flow gradually reverted to its original state, control experiments confirmed that background winds alone triggered weaker, analogous responses, underscoring the dominant role of typhoon forcing.

This study provides a detailed case analysis of typhoon-eddy interactions, yet the generalizability of these findings requires further investigation. Future work should systematically examine how eddy intensity modulates susceptibility to typhoon-induced disruptions, employing expanded observational datasets and targeted numerical experiments to quantify the mechanistic relationships between typhoon characteristics (e.g., wind speed, translation speed) and eddy responses.

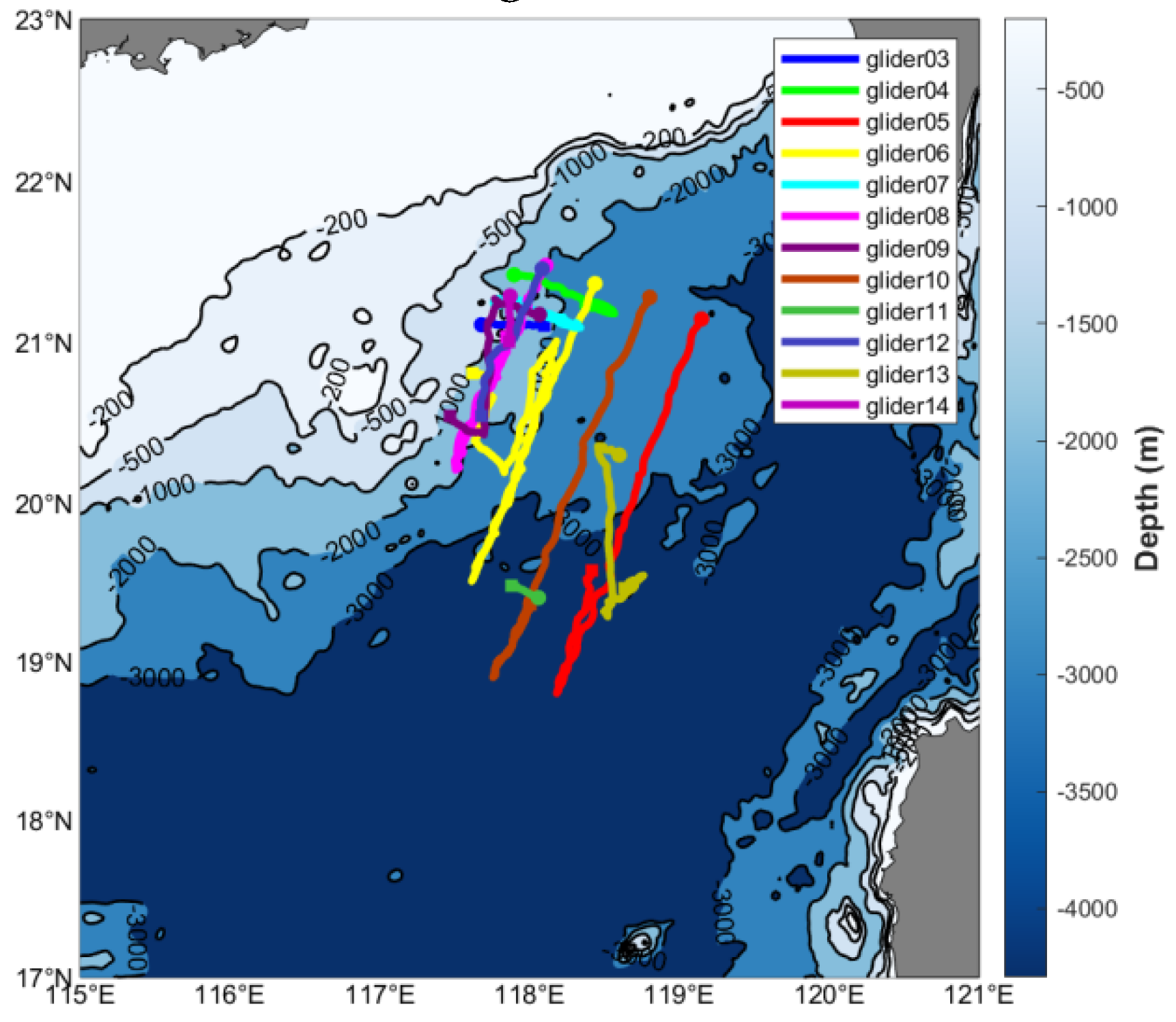

Figure 1.

Study region and trajectories of underwater gliders. The background shading represents water depth, while the colored curves indicate the movement paths of individual gliders.

Figure 1.

Study region and trajectories of underwater gliders. The background shading represents water depth, while the colored curves indicate the movement paths of individual gliders.

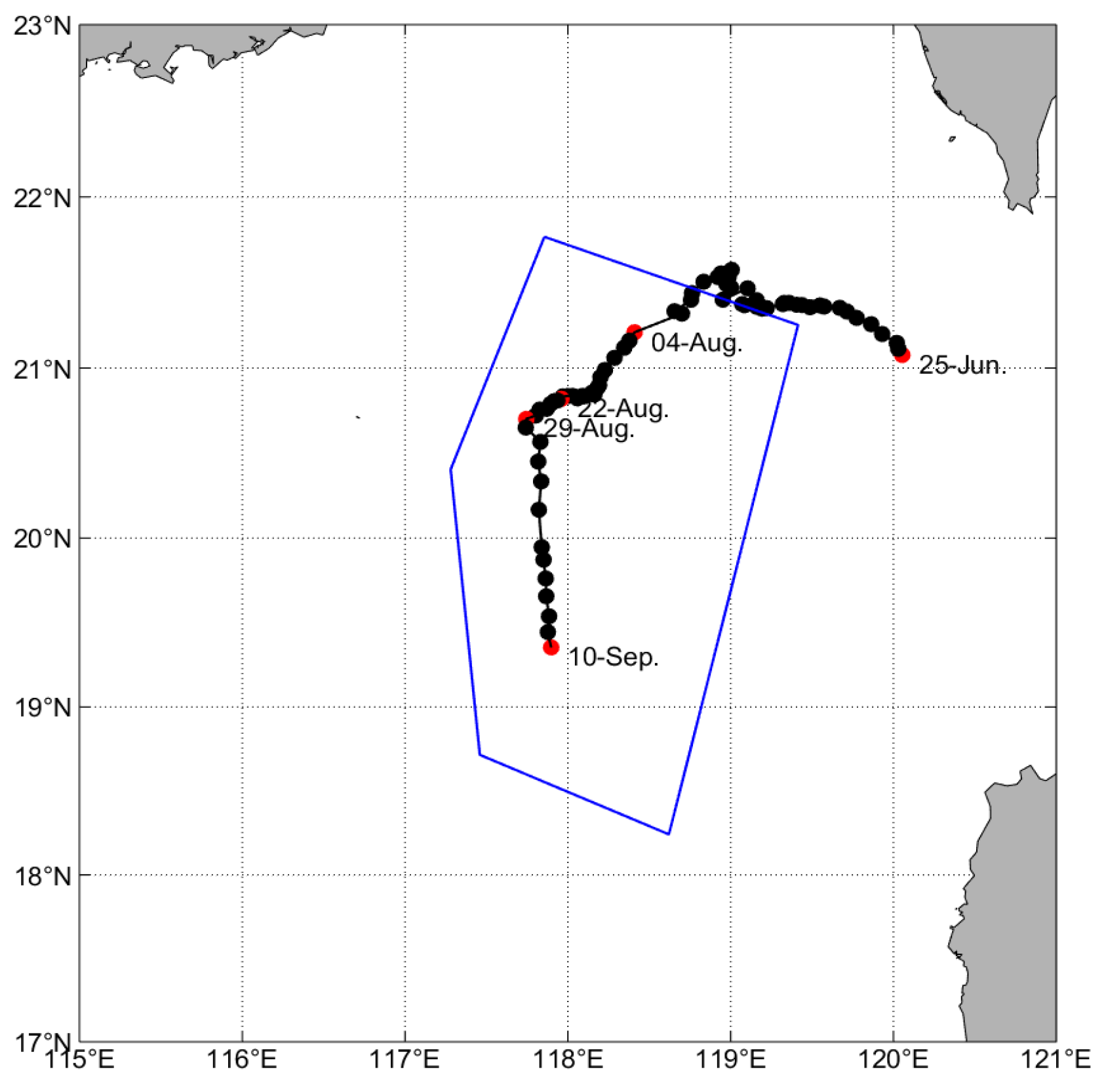

Figure 2.

The movement trajectory of the AE, with black dots representing the daily positions of the eddy center. Critical events including the eddy's generation time, the operational period of underwater gliders, the typhoon passage time, the completion of glider missions, and the eddy's dissipation time are all marked by distinct red dots.

Figure 2.

The movement trajectory of the AE, with black dots representing the daily positions of the eddy center. Critical events including the eddy's generation time, the operational period of underwater gliders, the typhoon passage time, the completion of glider missions, and the eddy's dissipation time are all marked by distinct red dots.

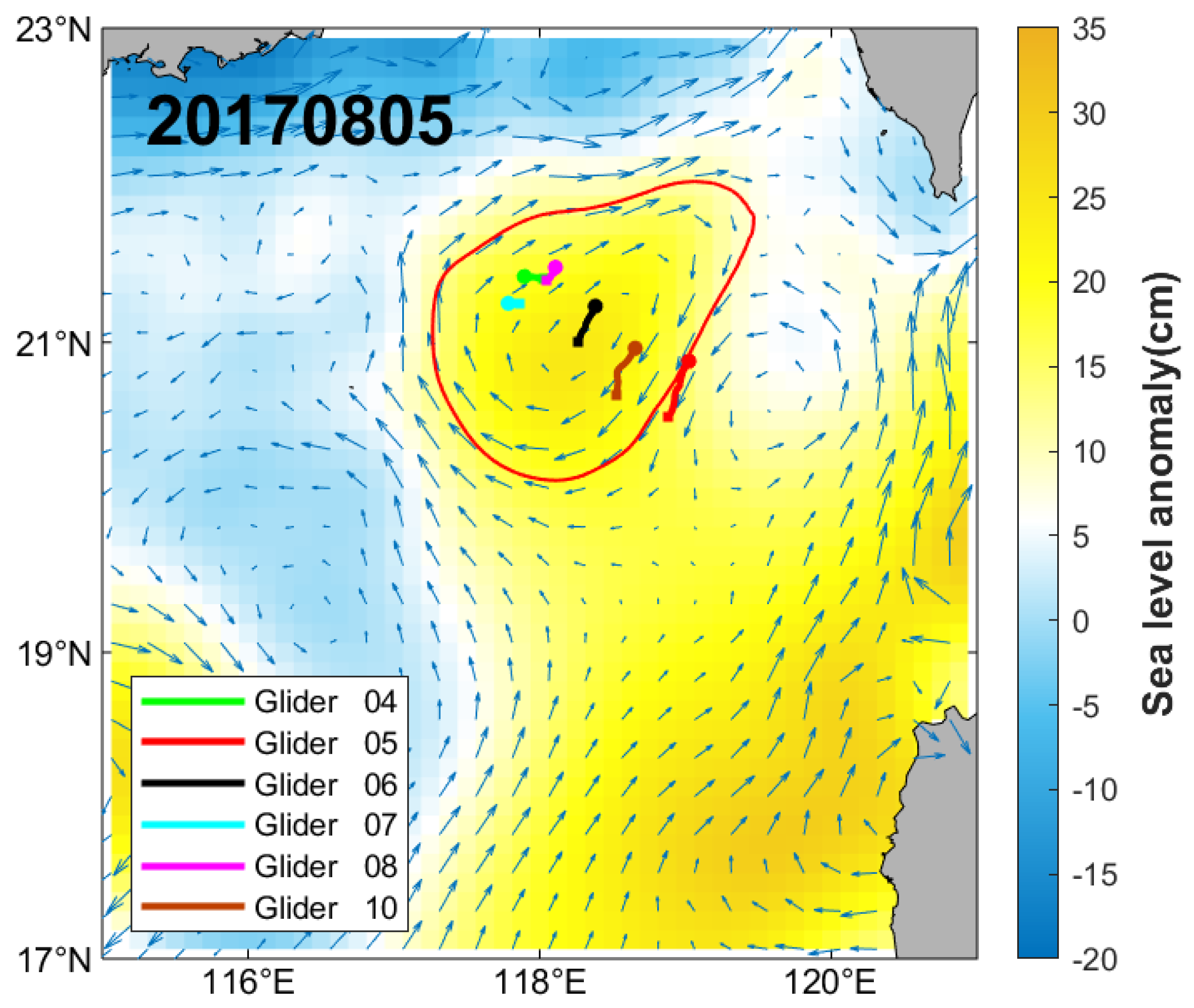

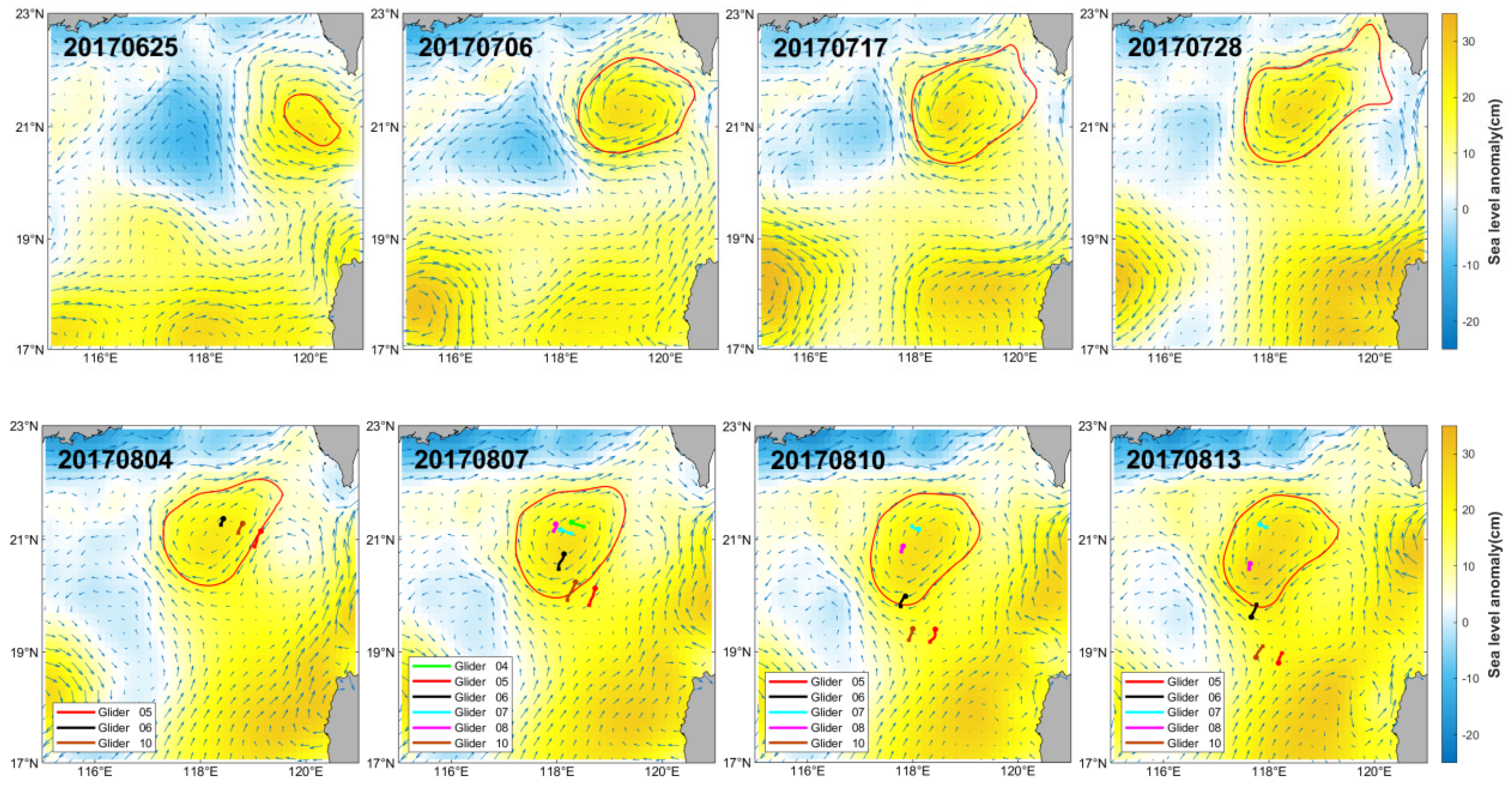

Figure 3.

The development of the AE, with the background representing SSHA and geostrophic current fields derived from satellite altimeter data. The red closed contour indicates the boundary of the AE identified using the WA method.

Figure 3.

The development of the AE, with the background representing SSHA and geostrophic current fields derived from satellite altimeter data. The red closed contour indicates the boundary of the AE identified using the WA method.

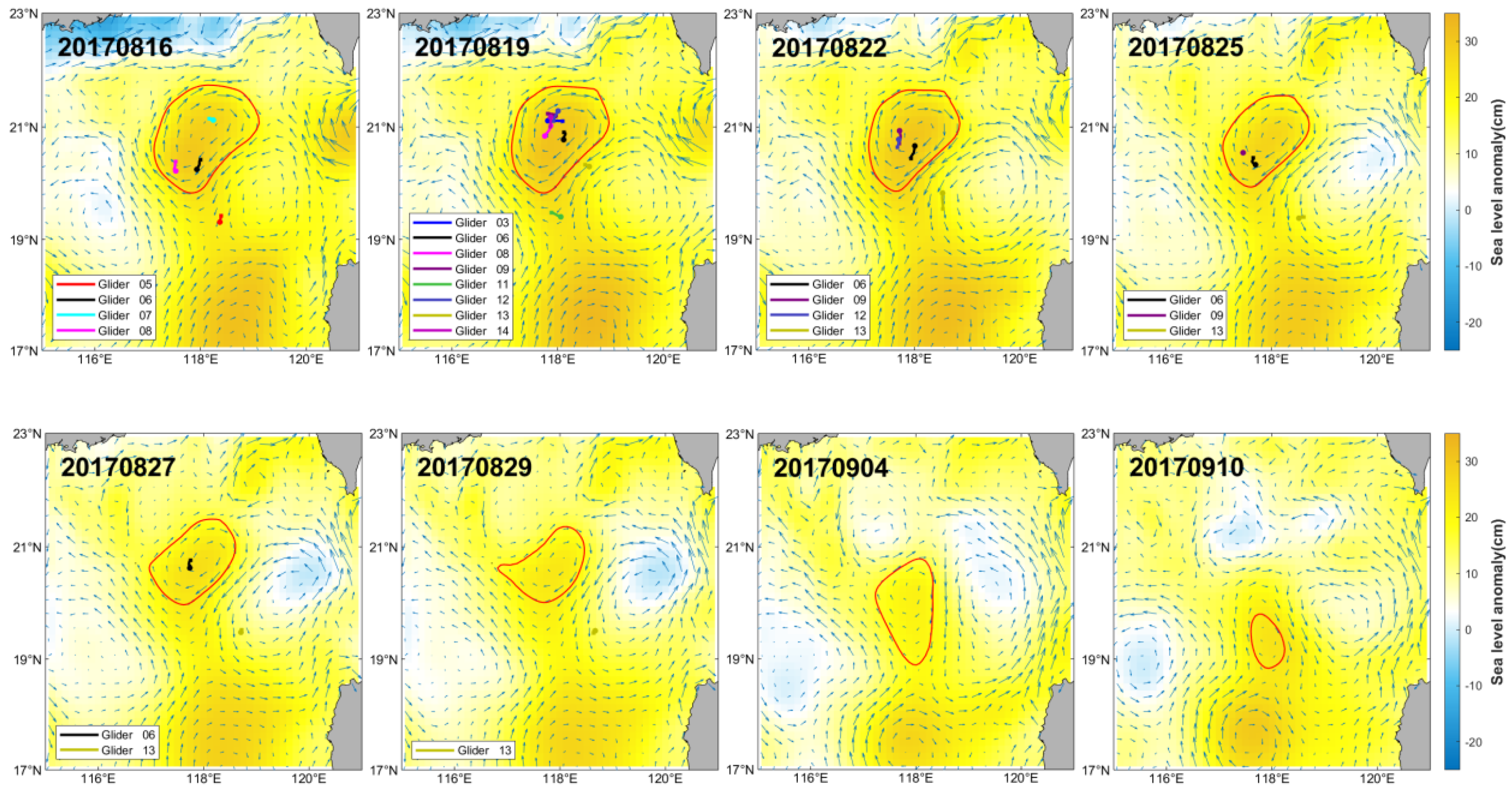

Figure 4.

Temporal evolution of the AE's properties, with vertical line segments indicating the timing of typhoon passages near the eddy: (a) eddy radius; (b) eddy amplitude; (c) eddy kinetic energy.

Figure 4.

Temporal evolution of the AE's properties, with vertical line segments indicating the timing of typhoon passages near the eddy: (a) eddy radius; (b) eddy amplitude; (c) eddy kinetic energy.

Figure 5.

Horizontal distribution of (a) temperature and (b) salinity across depth layers synthesized from all underwater glider observations.

Figure 5.

Horizontal distribution of (a) temperature and (b) salinity across depth layers synthesized from all underwater glider observations.

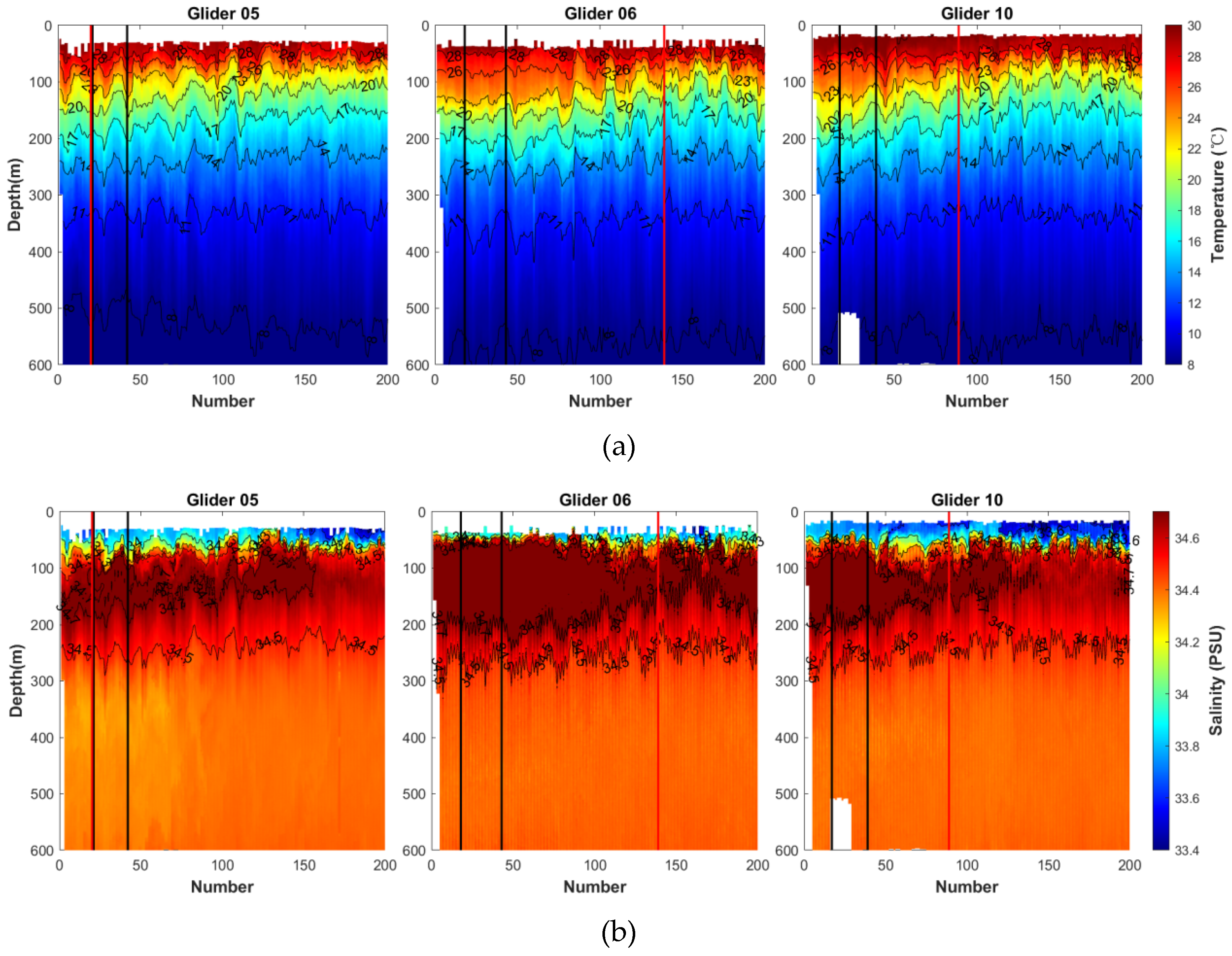

Figure 7.

(a) Temperature and (b) salinity profiles from Gliders 05, 06, and 10. The horizontal axis represents profile sequence numbers along each glider's trajectory, with data collected on August 5 bounded between two black vertical line segments. The red vertical line marks each glider's crossing of the eddy boundary (left: eddy interior; right: exterior).

Figure 7.

(a) Temperature and (b) salinity profiles from Gliders 05, 06, and 10. The horizontal axis represents profile sequence numbers along each glider's trajectory, with data collected on August 5 bounded between two black vertical line segments. The red vertical line marks each glider's crossing of the eddy boundary (left: eddy interior; right: exterior).

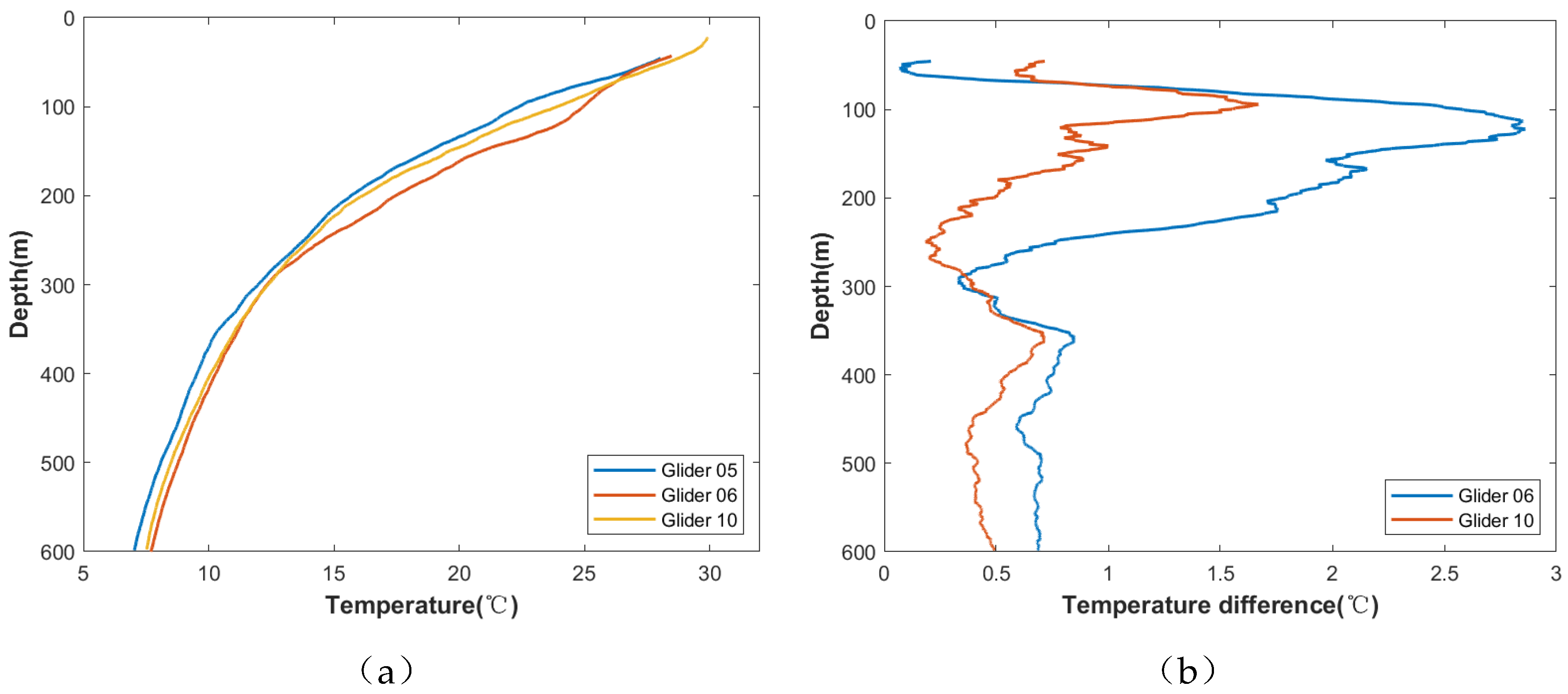

Figure 8.

Comparative analysis of temperature and salinity profiles from Gliders 05, 06, and 10 on August 5: (a) temperature-depth profiles ; (b) temperature differences (ΔT) between Gliders 06, 10 and Glider 05; (c) salinity-depth profiles ; (d) salinity differences (ΔS).

Figure 8.

Comparative analysis of temperature and salinity profiles from Gliders 05, 06, and 10 on August 5: (a) temperature-depth profiles ; (b) temperature differences (ΔT) between Gliders 06, 10 and Glider 05; (c) salinity-depth profiles ; (d) salinity differences (ΔS).

Figure 9.

Trajectory of Typhoon Hato (black curve) with annotated numbers indicating date and hour, superimposed on SSHA (background). The red contour denotes the AE boundary on 22 August. Typhoon intensity classification follows China Meteorological Administration standards, represented by point size and color (see legend). Operational glider numbers are annotated with corresponding typhoon intensity abbreviations during the observation period.

Figure 9.

Trajectory of Typhoon Hato (black curve) with annotated numbers indicating date and hour, superimposed on SSHA (background). The red contour denotes the AE boundary on 22 August. Typhoon intensity classification follows China Meteorological Administration standards, represented by point size and color (see legend). Operational glider numbers are annotated with corresponding typhoon intensity abbreviations during the observation period.

Figure 10.

Thermohaline structure within the AE during typhoon passage, derived from filtered glider profiles to remove high-frequency fluctuations: (a) temperature and (b) salinity distributions from Glider 06 (21-26 August) and Glider 09 (21-25 August).

Figure 10.

Thermohaline structure within the AE during typhoon passage, derived from filtered glider profiles to remove high-frequency fluctuations: (a) temperature and (b) salinity distributions from Glider 06 (21-26 August) and Glider 09 (21-25 August).

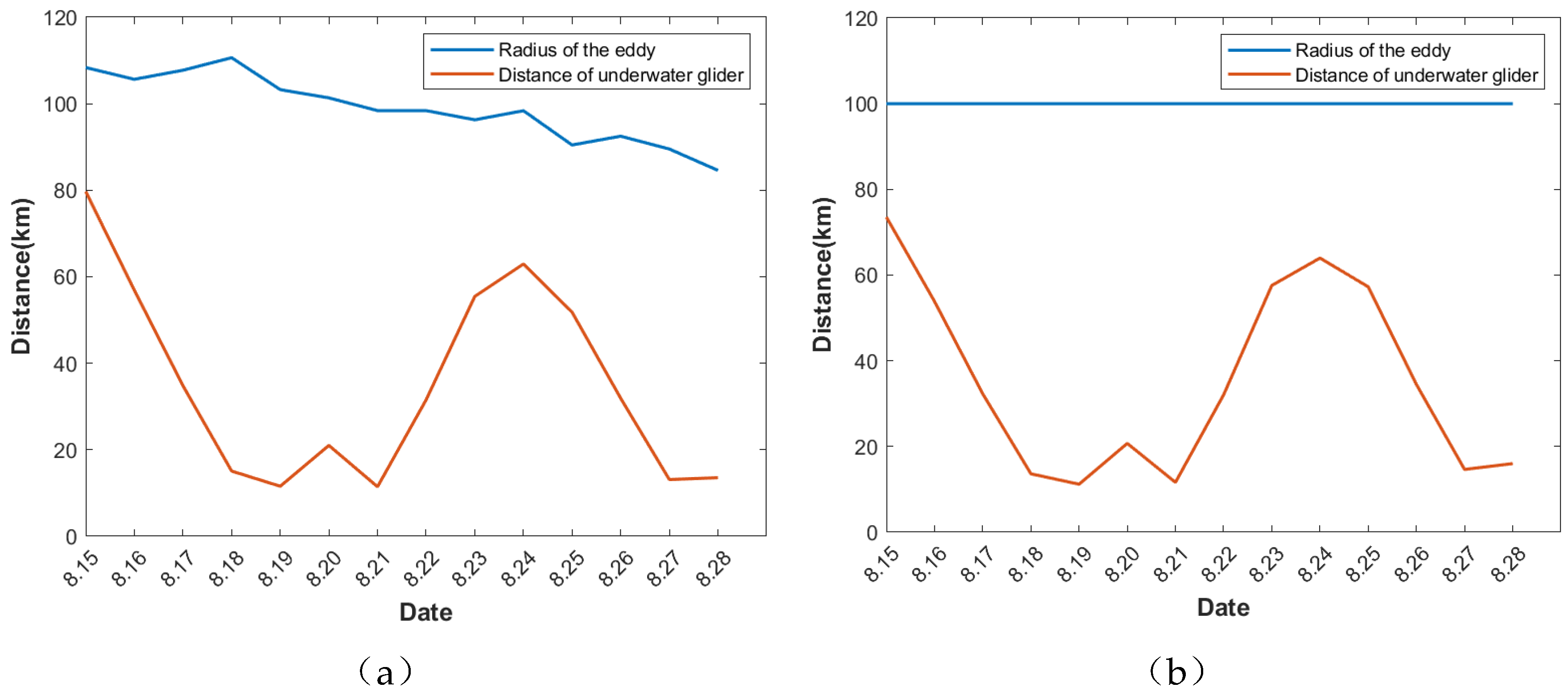

Figure 11.

Eddy-glider spatial relationship analysis: (a) Absolute distances showing temporal variations in eddy radius (blue curve) and Glider 06's distance from eddy center (orange curve) during 15-28 August. (b) Normalized relative distance (glider distance/eddy radius) revealing consistent sampling positions within the eddy's dynamic framework.

Figure 11.

Eddy-glider spatial relationship analysis: (a) Absolute distances showing temporal variations in eddy radius (blue curve) and Glider 06's distance from eddy center (orange curve) during 15-28 August. (b) Normalized relative distance (glider distance/eddy radius) revealing consistent sampling positions within the eddy's dynamic framework.

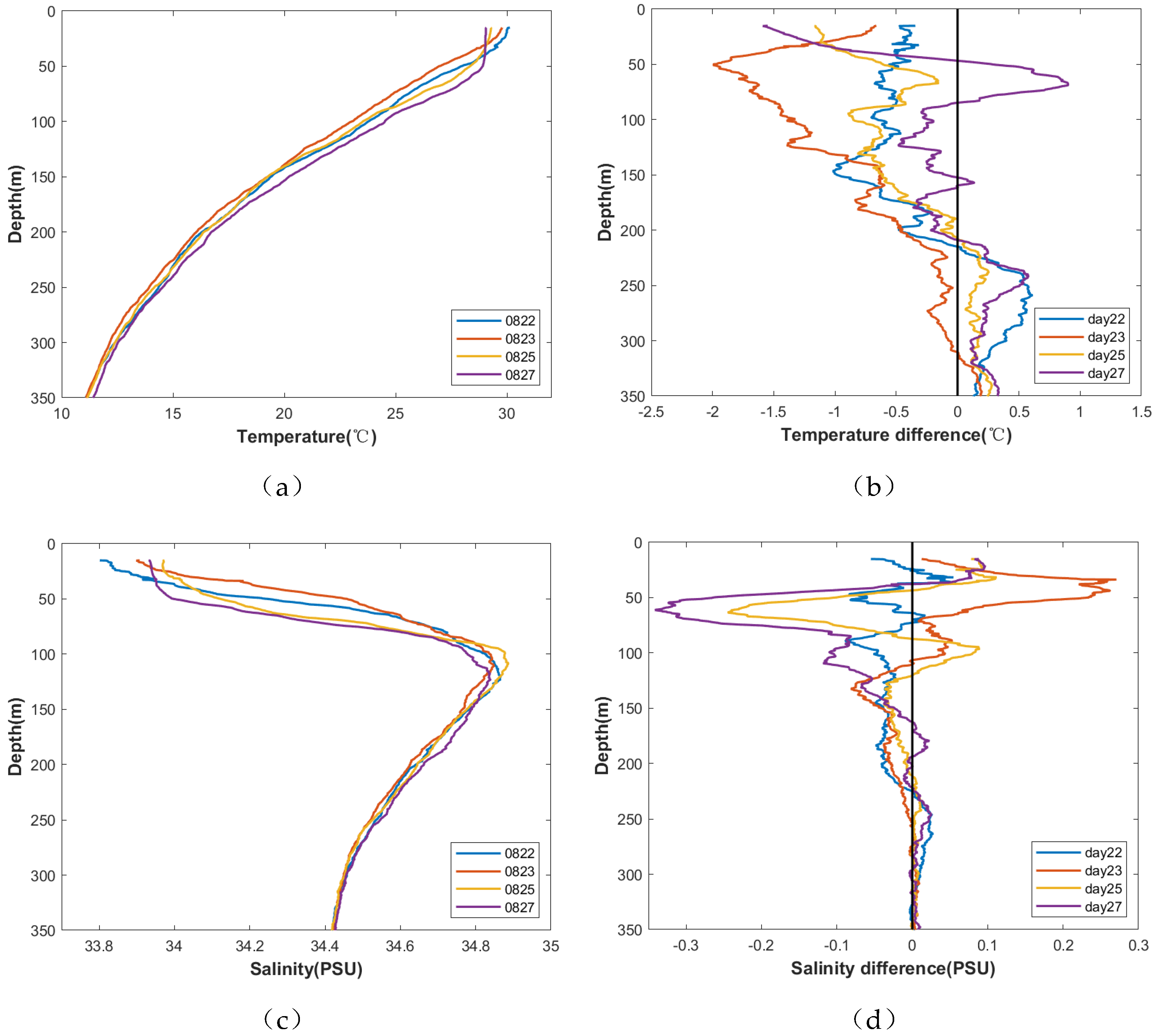

Figure 12.

Thermohaline evolution observed by Glider 06 during Typhoon Hato's passage and recovery phases: (a) Temperature-depth profiles on key dates (22, 23, 25, 27 August); (b) Temperature anomalies relative to position-matched control days (22 vs 17 August, 23/25 vs 16 August, 27 vs 18 August); (c) Salinity-depth profiles; (d) Salinity anomalies.

Figure 12.

Thermohaline evolution observed by Glider 06 during Typhoon Hato's passage and recovery phases: (a) Temperature-depth profiles on key dates (22, 23, 25, 27 August); (b) Temperature anomalies relative to position-matched control days (22 vs 17 August, 23/25 vs 16 August, 27 vs 18 August); (c) Salinity-depth profiles; (d) Salinity anomalies.

Figure 13.

Comparative wind fields on 22 August from dual numerical experiments: (a) Original ERA5 reanalysis data incorporating Typhoon Hato's complete wind structure; (b) Modified typhoon-free wind field where the typhoon-affected zone was replaced with the average wind in the SCS on that day, while preserving peripheral synoptic patterns.

Figure 13.

Comparative wind fields on 22 August from dual numerical experiments: (a) Original ERA5 reanalysis data incorporating Typhoon Hato's complete wind structure; (b) Modified typhoon-free wind field where the typhoon-affected zone was replaced with the average wind in the SCS on that day, while preserving peripheral synoptic patterns.

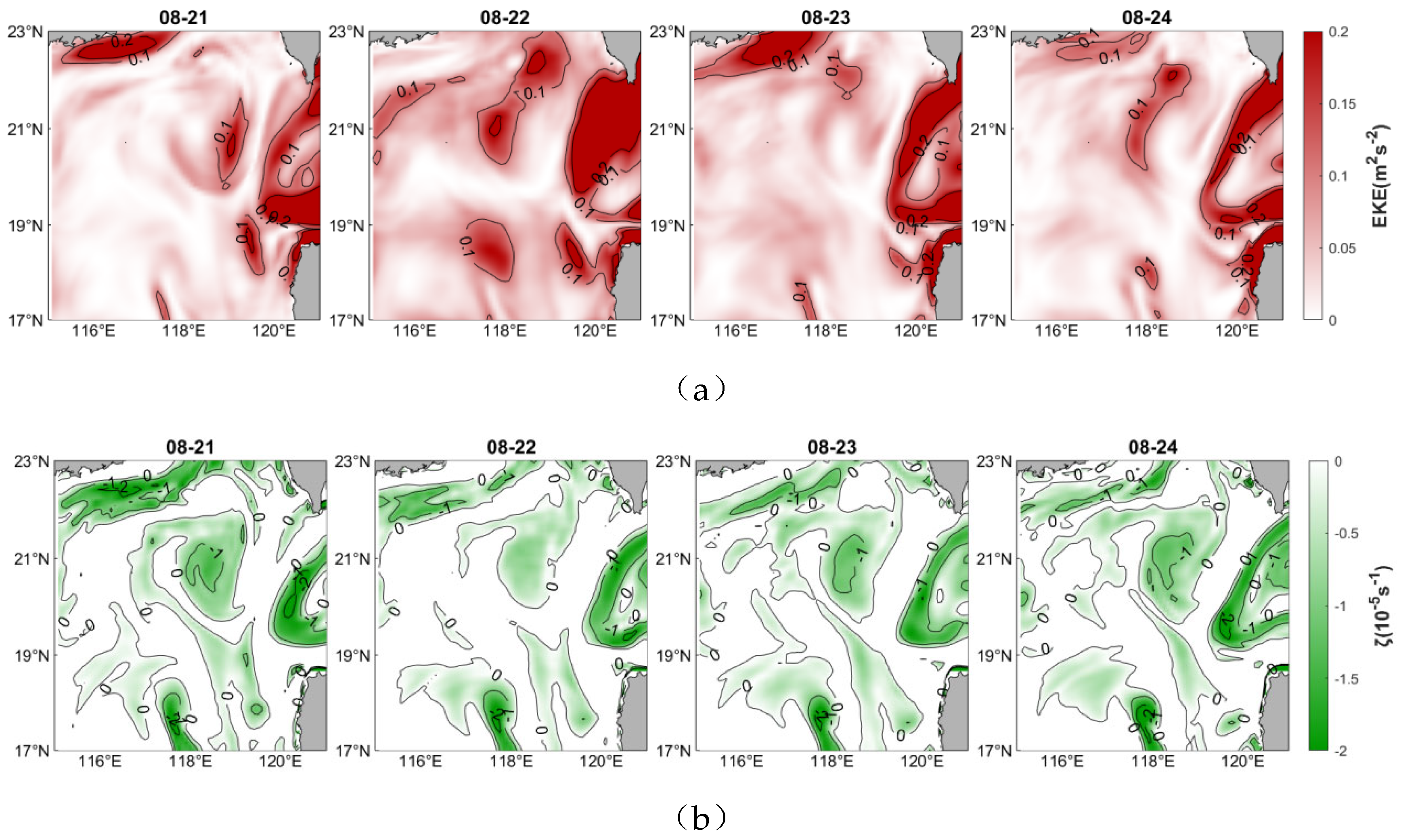

Figure 15.

Evolution of surface EKE and ζ derived from surface current fields during typhoon passage (21-24 August). (a) EKE distribution; (b) ζ fields documenting the injection of positive vorticity.

Figure 15.

Evolution of surface EKE and ζ derived from surface current fields during typhoon passage (21-24 August). (a) EKE distribution; (b) ζ fields documenting the injection of positive vorticity.

Figure 16.

Surface EKE and distributions under typhoon-free conditions (21-24 August), derived from numerical simulations with climatological wind forcing. (a) EKE distribution; (b) ζ fields documenting the injection of positive vorticity.

Figure 16.

Surface EKE and distributions under typhoon-free conditions (21-24 August), derived from numerical simulations with climatological wind forcing. (a) EKE distribution; (b) ζ fields documenting the injection of positive vorticity.

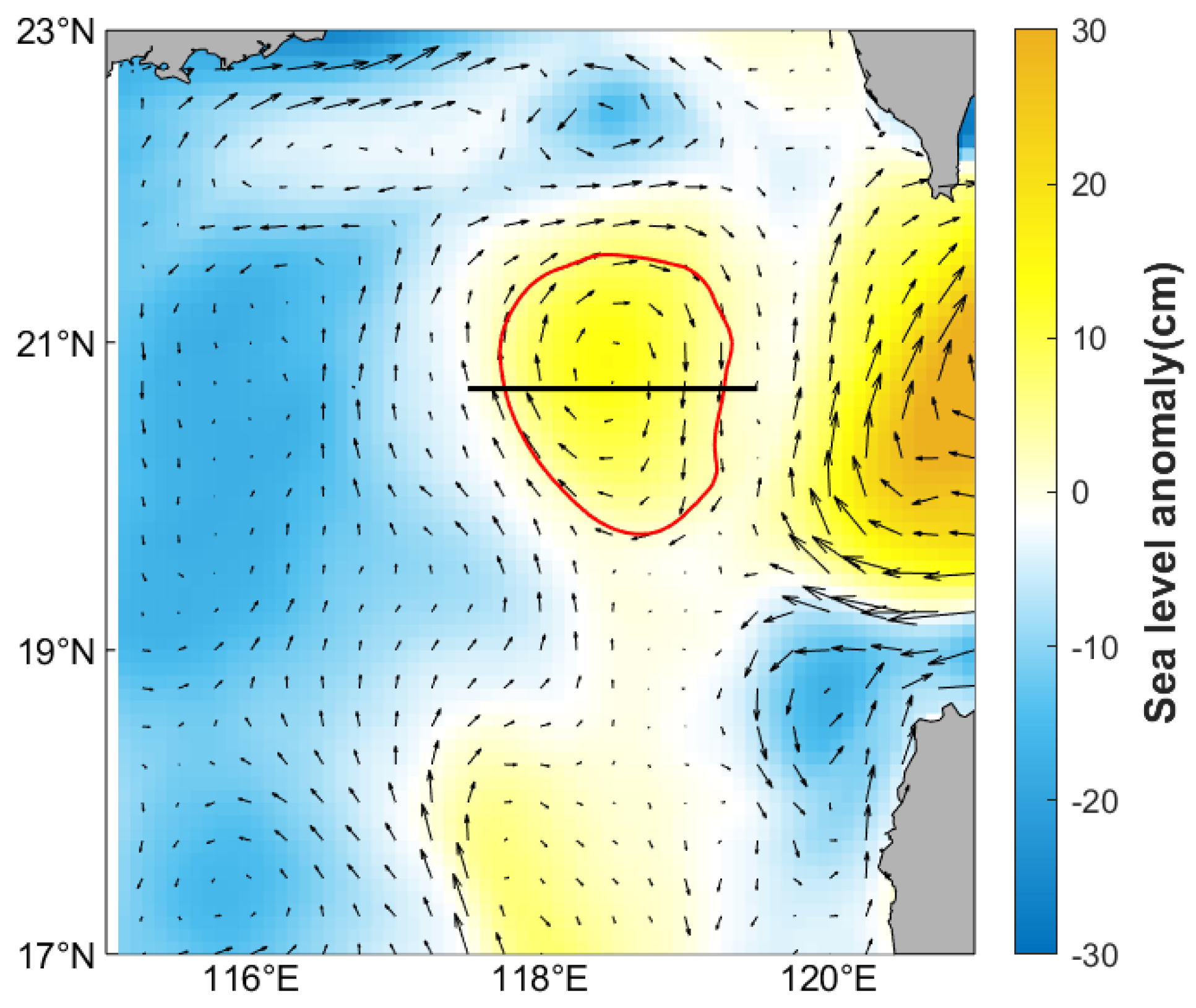

Figure 17.

Simulated SSHA and AE structure on 20 August (pre-typhoon baseline). The black transect line, aligned latitudinally through the eddy center at (118.5°E, 20.7°N), defines the reference section for analyzing subsequent vertical thermohaline changes.

Figure 17.

Simulated SSHA and AE structure on 20 August (pre-typhoon baseline). The black transect line, aligned latitudinally through the eddy center at (118.5°E, 20.7°N), defines the reference section for analyzing subsequent vertical thermohaline changes.

Figure 18.

Simulated vertical velocity cross-sections through the AE center (along 20.7°N), comparing typhoon-forced (a) and background (b) conditions during 21-24 August. Positive values (yellow) indicate upwelling, negative (blue) downwelling.

Figure 18.

Simulated vertical velocity cross-sections through the AE center (along 20.7°N), comparing typhoon-forced (a) and background (b) conditions during 21-24 August. Positive values (yellow) indicate upwelling, negative (blue) downwelling.

Figure 19.

Simulated temperature evolution in the typhoon experiment along the AE's central transect (aligned with 20 August eddy center position). (a) Temperature profiles from 21-24 August; (b) temperature anomalies relative to 20 August.

Figure 19.

Simulated temperature evolution in the typhoon experiment along the AE's central transect (aligned with 20 August eddy center position). (a) Temperature profiles from 21-24 August; (b) temperature anomalies relative to 20 August.

Figure 20.

Simulated temperature evolution in the typhoon-free control experiment along the AE's central transect (identical to

Figure 19's spatial coordinates). (

a) Temperature profiles from 21-24 August; (

b) temperature anomalies relative to 20 August.

Figure 20.

Simulated temperature evolution in the typhoon-free control experiment along the AE's central transect (identical to

Figure 19's spatial coordinates). (

a) Temperature profiles from 21-24 August; (

b) temperature anomalies relative to 20 August.

Figure 21.

Simulated salinity evolution in the typhoon experiment along the AE's central transect (aligned with 20 August eddy center position). (a) Salinity profiles from 21-24 August; (b) salinity anomalies relative to 20 August.

Figure 21.

Simulated salinity evolution in the typhoon experiment along the AE's central transect (aligned with 20 August eddy center position). (a) Salinity profiles from 21-24 August; (b) salinity anomalies relative to 20 August.

Figure 22.

Simulated salinity evolution in the typhoon-free control experiment along the AE's central transect (identical to

Figure 19's spatial coordinates). (

a) Salinity profiles from 21-24 August; (

b) salinity anomalies relative to 20 August.

Figure 22.

Simulated salinity evolution in the typhoon-free control experiment along the AE's central transect (identical to

Figure 19's spatial coordinates). (

a) Salinity profiles from 21-24 August; (

b) salinity anomalies relative to 20 August.

Figure 23.

Vertical structure and current velocity distribution of the AE from 21-24 August, with background colors indicating flow velocity magnitude and eddy identification via the WA method (missing depth layers indicate failed eddy detection). (a) Results from the typhoon-forced simulation; (b) results from the typhoon-free simulation.

Figure 23.

Vertical structure and current velocity distribution of the AE from 21-24 August, with background colors indicating flow velocity magnitude and eddy identification via the WA method (missing depth layers indicate failed eddy detection). (a) Results from the typhoon-forced simulation; (b) results from the typhoon-free simulation.

Table 1.

Distance between underwater gliders and the AE center on 5 August 2017.

Table 1.

Distance between underwater gliders and the AE center on 5 August 2017.

| Glider ID |

Distance from Eddy Center (km) |

Relative Position |

| 05 |

78.5 |

Eddy boundary |

| 06 |

9.8 |

Near eddy core |

| 10 |

46.7 |

Intermediate transition zone |

Table 2.

Maximum temperature and salinity differences between Gliders 06, 10 and Glider 05, with corresponding depths.

Table 2.

Maximum temperature and salinity differences between Gliders 06, 10 and Glider 05, with corresponding depths.

| Glider Pair |

Max ΔT (°C) |

Depth (m) |

Max ΔS (PSU) |

Depth (m) |

| Glider 06 vs. 05 |

2.86 |

122 |

0.65 |

61 |

| Glider 10 vs. 05 |

1.67 |

94 |

0.14 |

61 |

Table 3.

Maximum temperature and salinity differences below 300 m depth.

Table 3.

Maximum temperature and salinity differences below 300 m depth.

| Glider Pair |

Max ΔT (°C) |

Depth (m) |

Max ΔS (PSU) |

Depth (m) |

| Glider 06 vs. 05 |

0.85 |

358 |

0.09 |

350 |

| Glider 10 vs. 05 |

0.72 |

361 |

0.07 |

347 |

Table 4.

Comparative analysis of temperature reduction characteristics within the eddy core during the typhoon-affected period for both experimental scenarios.

Table 4.

Comparative analysis of temperature reduction characteristics within the eddy core during the typhoon-affected period for both experimental scenarios.

| Date |

08-21 |

08-22 |

08-23 |

08-24 |

| (TC)Max ΔT (°C) |

0.31 |

1.15 |

1.22 |

1.68 |

| (TC)Depth(m) |

70 |

60 |

60 |

70 |

| (No TC)Max ΔT (°C) |

0.25 |

0.36 |

0.51 |

0.66 |

| (No TC)Depth(m) |

50 |

70 |

60 |

50 |