1. Introduction

A challenge of combustion is a numerical simulation. Combustion research investigated the gas emissions of NOx and CO using 2D axisymmetric burners for methane-air diffusion flame combustion mode [

1] and the numerical analysis of the partially-premixed burner for industrial gas turbine combustion application [

2,

3]. The research used the Eddy Dissipation Model (EDM), a non-premixed and partially premixed flame model, and the simulation of syngas combustion by a non-premixed flame model coupled with the DO approach that showed better agreement than experimental data [

4].

In experimental and numerical investigations on the effect of different air-fuel mixing on the performance of a lean liquid-fueled swirl combustor, the numerical results show different temperatures and species fields predicted for the non-premixed and partially premixed models [

5]. A numerical study applied the flamelet progress variable approach on the local flame structure for the partially premixed Dimethyl Ether (DME)/air flame. This study obtained excellent results for the temperature and the species mass fraction [

6]. Combustion research [

7] conducted a large Eddy simulation (LES) of kerosene spray injection in an aeronautic combustor to assess the capability of an energy deposition model and to reduce the chemical kinetic and global spray injection.

A type of burner, burner moderate and intense low oxygen Dilution (MILD), was tested by the eddy dissipation concept [

8], a numerical study in a non-premixed micro combustor with different fuel inlet velocities [

9], and direct numerical simulation (DNS) in non-premixed MILD combustion. The research investigated auto-ignition, flame propagation, and aspects of the combustion with a lean mixture. Concepts applied preheating and dilution of the reactant mixture to get a higher temperature than the auto-ignition temperature of the used fuel. It utilizes exhaust gas recirculation (EGR) to improve gas emissions and increase combustion efficiency and stability [

10]. However, this method also raised the peak flame temperature and NOx. Inert gases from internal gas recirculation (IGR) have been one strategy to reduce NOx emissions. This method can also minimize oxygen use, known with moderate or intense low oxygen Dilution (MILD) and flameless combustion. Both ways can enhance thermal efficiency and decrease gas emissions [

11].

A combustion strategy was applied again, using two spray flames with diameters of 10.5 mm and 25 mm to outline the effect of mixing models. CO2 mass fraction for the three models had similar trends by the result value ranging from 0.01 to 0.125 [

12]. The mixing model has determined the flame shape, flow, turbulence, temperature, and species compositions. The predictions of the product H2O by different models were similar to predictions on temperature [

13]. The reduction of nozzle diameter is one of the other ways to get an optimum operating condition as carried out by [

11] in premixed cyclone combustion experimentally and numerically. The nozzle diameter of 30 mm and the equivalence ratio of 0.89 can yield better gas emissions and flame temperature. The research observed sizes of the fuel orifice, air orifice, combustor diameter, and tailpipe diameter were 1 mm and 2 mm, 5.9 cm, and 2.7 cm, respectively, with pipes of three different lengths, 25.4 cm, 40.7 cm, and 56 cm [

14].

Making suitable mixtures between reactant flows and surroundings is a technique widely applied by modifying a nozzle geometry. It determines combustion products. Three nozzle types, namely circular, square, and rectangular, were investigated. From the mean velocity contours, using non-circular nozzles can shorten the potential core length by around 33% compared to the circular nozzle [

15]. The rectangular nozzle can produce a centerline velocity decay rate higher than the circular nozzle. However, the slot nozzle produces a centerline velocity decay rate higher than both the rectangular and circular nozzles. The research observed eight different nozzle geometries, such as a round, square, cross, eight-corner start, six-lobe daisy, equilateral triangle, ellipse, and rectangle. The effects of nozzle geometry were significant in mean velocities and turbulent quantities [

12] and determined the diameter size of droplets. The operating conditions at the size of around 20 mm for the gas turbine application generally were carried out. The small droplet sizes can evaporate much faster than bigger droplets [

16].

The heat transfer process inside the burner was analyzed by coupling spray combustion, forced convection on the wall surface, and conduction in the solid with air heated over the wall. The results were that above and below the cone possessed a different behavior. Above the cone, the temperature gradient stimulated a hot flame so that the temperature of fresh air could elevate. However, below the torch, the negative temperature gradient and stable stratification were achieved [

17]. The prediction of wall temperature can use multiphysics simulation with large-eddy simulation (LES), conjugate, and radiative heat transfers. The gas temperatures downstream of the burner chamber were cold. It took place when considering the radiation phenomena, and it were close to the adiabatic temperature when close to the combustion centerline. The maximum temperature remained the same because the sudden temperature increased through the flame front influenced by radiation heat transfer [

18].

A comparative study tested non-premixed and partially premixed combustion models in a realistic Tay model combustor to identify temperature and species concentration [

19]. To reduce gas emissions, a catalyst can also be used to get complete combustion [

20]. The flame stability can be achieved by raising the temperature of reactant species which can also change other combustion characteristics of the flame temperature and the quality of gas emissions. As noted, the smaller geometry size of the combustion chamber can shorten the residence time of the combustion reaction of reactants. For better combustion, the residence time should be longer than the chemical reaction time. The rise of the mixture fraction temperature can shorten the combustion chemical reaction time [

21,

22]. As conducted by a researcher in [

23] applied different chamber geometries to simulate species transport and non-premixed combustion model to determine better chamber design. A combustion technique stabilized the combustion flame using a stoichiometry ratio. The reactant mixtures were acetylene, H

2, and air [

24]. The other ways accelerated combustion chemistry and reduced CO on flame characteristics and chemical kinetics in a swirl gas turbine combustor using Large Eddy Simulation (LES) [

25], used non-premixed combustion model and distributed combustion conditions with the methane as a fuel [

26]. A study performed the combustion research of the H

2/air mixture with CFD modeling for a 3D and 2D computational domain of micro-cylindrical combustor [

27]. That was using the eddy dissipation concept (EDC) and the combustion characteristics of the wall and fluid temperature, hydrogen mass fraction, velocity, and also pressure.

This numerical simulation uses a 2D burner for the diffusion combustion flame. Preheating the mixture fraction of the reactants can widen and change the characteristics of the contours of flame temperature, gas emissions, and flame stability. This work aims to test the combustion performances of the designed geometry burner. Three parameters investigated are fuel and air inlet velocities, inlet temperatures, and oxygen concentrations.

2. Burner and Simulation Setups

The mathematical model has considered several assumptions about the chemical and physical processes to solve and yield results in the combustion study cases. Even though simplifications were performed, perfect setups of mathematical forms have to have similar cases in turbulent flames. The fundamental study of current research is to attend to mathematical tools. This study investigated the turbulence-chemistry interaction of the eddy dissipation model by solving the general transport equations of mass, momentum, energy, and species concentrations.

The combustion chamber for the current work is shown in

Figure 1. The sizes of which are 100 cm in length, 50 cm in diameter, 2 cm in fuel injection, and 3 cm in air injection. The computational grid used triangle methods together with three-edge refinement around fuel and air inlets. The max face size, minimum size, and size function are 2 x 10-3 m, 1.333 x 10-4 m, and curvature, respectively, with which obtained the numbers of 146,973 nodes and 291,830 elements. To simulate the governing equations of mass, momentum, energy, and heat transfer for diffusion combustion flame models that are using FLUENT-ANSYS software. The pressure-velocity coupling uses a SIMPLE algorithm with a second-order upwind scheme to discretize the governing equations. The other solver setting with the gradient evaluation used the least-squares cell method. The momentum and energy use second-order upwind. The turbulent kinetic energy and turbulent dissipation rate use first-order upwind. The scale residuals for convergence are 1 x 10-6 for continuity, energy, and species mass fractions.

The boundary conditions were C

12H

23 as fuel and air as an oxidizer, consisting of 21% oxygen and 79% nitrogen. The inlet magnitude velocities of the fuel tested were 0.01, 0.03, 0.05, 0.075, 0.1, 0.3, 1, 5, and 10 m/s. The constant of the used air was 0.5 m/s. At the exit combustion chamber, a fixed pressure of 0 Pa was specified, and by choosing stainless steel as the combustion chamber material walls. The boundary conditions of the inlet fuel, inlet air, walls, and pressure in the current study are described in more detail in

Table 1. The setup of the simulation is shown in

Table 2. The simulation used an Intel (R) Core (TM) i5-7400 CPU @ 3.00 GHz and an installed RAM of 8 GB.

3. Numerical Combustion Model

Most combustors in industrial applications operate using the concepts of spray and reactive flows within the turbulent regime characterized by high Reynolds numbers. The simulation of multi-component fuel spray requires better treatment concepts to yield good turbulence within both the liquid and gaseous phases [

28]. The oxy/air-fuel flow in many combustion systems is turbulent. The other types are laminar and transition. The transition flow exists between those two regimes. The turbulent flow is more complex mathematically than both of the flows [

29].

3.1. Transport Equation and Chemical Model

The mathematical concept of fluid inside the combustion chamber is described by a set of governing equations (1-4) for mass, momentum, species, and energy in Cartesian coordinates, respectively:

where

is the air-fuel mixture density, u is the velocity vector, and T is the mixture temperature.

is the mass fraction of species

,

is the thermal diffusivity,

is the specific heat at a constant pressure of species

, and

is the heat source terms due to chemical reaction.

is the correction velocity of species i. The sear stress takes place due to a velocity gradient. The stress tensor equation (5) is

where

is the air-fuel dynamic viscosity,

is the identity matrix, and

is the transpose operation. The Lewis number (Eq. 6), the specific heat at a constant pressure of the air-fuel mixture (Eq. 7), and the correction velocity (Eq. 8), respectively, are calculated with the following equations

where

is the local mean molecular weight of the air-fuel mixture,

is the mass diffusivity of species

. The Schmidt number is the ratio between viscosity and diffusion,

. The Prandtl number is the ratio between viscosity and heat transfer,

. The Schmidt and Prandtl numbers are

due to

.

The combustion process in the combustor can influence the flow field through the density parameter. The equation of state for ideal gases expresses the density,

. The local heat release rate (Eq. 9) and the relation between the enthalpy and the temperature (Eq. 10) are

The specific enthalpy of species can be expressed as the sum of formation enthalpy at a reference temperature ,

and the heat capacity of the gas mixture for the temperature range between To and the actual value T.

For the Combustion reaction model, the field of chemistry concerning the reaction rate is called chemical kinetics. The chemical reaction rate, , is the decrement change in concentration of the air-fuel reactant () to the gas emissions as combustion products at the time per time ().

For the combustion process the concentration of the fuel and air as the reactants depends on time. That always decreases with it, and the concentration of the combustion products as reaction results always increases with time. With this, the concentration of reactants always has a negative sign. For complete combustion reactions without involving N

2 and some inert gaseous, the main chemical reaction (Eq. 14) inside the combustion chamber and the fuel consumption rate (Eqs. 15 and 16) can be determined as

The p and q calculated investigated the depending on the initial consumption rate and initial concentrations of Fuel and oxygen. The sum of n and m is as an overall reaction order. Computing the combustion rate constant (Eq. 14) that can use the following Arrhenius equation (13)

where A, z, p are the frequency factor, the collision frequency, the steric factor (p < 1), respectively, and

is the collision fraction at sufficient energy to produce a chemical reaction. Eq. (17) can be rewritten as

Eq. (13) can also be expressed in the logarithmic form (Eq. 15) to find each of the variables

Which is identically a linear equation, Where slope and intercept.

Assuming the chemical equilibrium of gaseous emissions with a complete combustion reaction is occurring without involving N

2 and some inert gases, the equilibrium constant inside the combustion chamber (Eq. 16) is

For the complete reversible reaction, the equilibrium rate constant at the left side, as described in equation (17), is

From the ideal gas,

, the relation between pressure and concentration is

The equilibrium constant equations (19-20) are

where

and

are equilibrium constants in terms of concentrations and partial pressures, respectively.

is the sum of the gas emission coefficients, and

is the sum of the reactant coefficients.

To describe species equations in the governing equations, which can use either mole fraction (X or mass fraction (Y).

From the gas ideal as described in Equations (21-22), the equation becomes

The combustion reactants can also use the mass fraction (Y) (Eqs. 23-24) to symbolize the concentration of species

3.2. Radiation Model

ANSYS Fluent offers five radiation models: the discrete transfer radiation model (DTRM), the P1-radiation model, the Rosseland model, the surface-to-surface (S2S), and the discrete ordinate model (DOM). It allows for including radiation with or without a participating medium in heat transfer simulations. Heating or cooling the surfaces due to radiation or heat sources within the fluid phase is included in one of the above models. Considering the P-1 radiation model, the simplest problem of the more general P-N model, the influence of geometry configuration on the radiative heat transfer, is used as a numerical model in the current study.

Radiative heat transfer should be included in a numerical simulation when the radiant heat flux is large compared to the heat transfer rate due to convection or conduction [

30]. Analysis should consider the radiation model if the combustion temperature is more than 2000 K [

27]. The volumetric radiative heat transfer involving walls and the fluid medium is more prominent in the combustion chamber, where the gas emissions participate as a medium. Gas emissions can absorb and emit radiation [

31]. The radiative transfer equation (25) for an absorbing, emitting, and scattering medium at position

in the direction

is

where

is the scattering direction vector, s is the path length, a is the absorption coefficient. n is the refractive index,

is the scattering coefficient,

is the Stefan-Boltzmann constant (5.669 x 10

-8 W/m

2. K

4), I is the radiation intensity, T is the local temperature,

is the phase function, and

is the solid angle.

3.3. Diffusion Combustion Flame

The combustion research mode consists of diffusion, premixed, and partially premixed flames. The diffusion flame (non-premixed combustion flame) occurs where oxidizer and fuel are not mixed or enter the combustor with distinct streams [

32]. Combustion occurs in the mixing layer, which is very small compared to the combustion system, and the mixing step brings reactants into the mixing zone. Controlling combustion and the chemical reaction is very difficult [

29]. The time required for turbulent mixing to occur through convection and diffusion processes is significantly larger than that for most of the combustion chemical reactions. The turbulent mixing and chemical reactions are the rate-limiting processes [

33].

The combustion process is simplified to a mixing case where transport equations for one or two mixture fractions are solved. In the diffusion model in ANSYS Fluent, the thermochemistry processes of the mixture fraction between fuel and oxidizer are calculated using PDFs [

28]. Applying the diffusion combustion model in ANSYS Fluent, which offers the modeling of secondary stream, empirical secondary stream, and empirical fuel stream. When reactant species of fuel and oxidizer mix in the reaction zone, the chemistry can be determined using the other approaches [

28].

The mixing of fuel and oxygen, and the chemical reaction occur at the same time. Therefore, it is the rate of mixing that controls the combustion rate. Depending on the state of the fuel, there are gaseous diffusion combustion, and liquid spray combustion. Gaseous diffusion consists of laminar and turbulent combustion. Depending on the flow condition of the fuel gas discharge into the combustion chamber. Since the process occurs inside the flame, it is a complicated case. The simplifications of differential equations for diffusion flames are

On the flame surface, fuel and air should mix in a proper ratio. Chemical reactions occur only on the flame surface, and they are instantaneous.

b. The flows of fuel and air are one-dimensional with uniform velocity. The diffusion of the reactants only takes place along the radial directions.

c. The mole number does not change in the combustion reactions. The pressure is the same throughout the whole process.

d. The diffusion of fuel and oxygen in inert gases is regarded as the diffusion of two components. Their diffusion coefficients are equal.

The density and diffusion coefficient (D) of mixed gases do not correlate with temperature, so that both of them are constant in the radial direction .

At constant pressure,

, the diffusion coefficient of the two components is

. Therefore, the effects of temperature on

are small. The value of which is approximated as a constant in the radial direction. According to the above assumptions, the mass fraction conservation equation for component k with the chemical reaction is

Each component as follows

By referring to assumption (b), the parameters are

and

and for a steady-state diffusion combustion process where

, So that the eq. (35) becomes

Note that chemical reaction only takes place on the flame surface by referring to assumption (a), but when the process on the flame surface is not considered,, then by using assumption (d), .

The diffusion velocity

is described in the following Equation (30)

The second term on the right side of equation (26) can be simplified by referring to the forms of (

and

) and assumption (e)

For the case of an axisymmetric diffusion flame with the cylindrical coordinate system are used

is not related to

when it is axisymmetric. By referring to assumption (b) and neglecting the diffusion throughout the z-direction

By substituting Eq. (35) into Eq. (32) is found (Eq. 36)

The diffusion flame equation can be simplified by substituting

and equation (36) into equation (31), as formed in equation (37)

where

is the mass fraction of component

, D is the diffusion coefficient of two components, w is the flow rate of gaseous fuel or oxidizer, z is the distance of a certain plane of the flame from the coordinate of the discharge opening. The concentration fields of fuel

and oxygen

can be determined by the partial differential equation (38), only that the boundary conditions are different (not including the point on the flame surface, because at point

. Thus, two differential equations have to be solved for the distribution of

and

. Adopting the mathematical method by Back and Schumann, a new variable is defined

where

is the radius of the flame surface. The fuel-oxygen ratio

calculated by Equation (39)

The concentration distribution function of the fuel inside the flame and oxidizer outside the flame (on each plane of the flame) can be correlated by the following boundary conditions, as shown in Equations (40-42), where L is the flame height.

4. Results and Discussion

As explained by previous research in [

34], referring to some research conclusions, the spray flame depends on the nozzle, fuel, burner, and operating parameters. The diffusion combustion flame model, coupled with energy, p1 for the radiation model, and k-epsilon for the viscous model, is used to determine the combustion performance of a burner. The contours of the temperature and gas emissions are used as references to evaluate the combustion characteristics of this current work, as performed by previous work in [

3]. For the high combustion temperature, gas emissions react with each other to form emission products. Therefore, the parameters under various conditions are an essential parameter to be investigated

[3,27,28,31,36]. CO

2 indicates complete combustion, whereas HC and CO indicate incomplete combustion [

39]. The temperature of a cone is plotted along the axial axis at the radial axis of the centerline. That confirms the symmetry of the simulation result inside the combustion flame [

17].

Each fuel has limits to burn (called flammability limits), so that the magnitude of velocities chosen in this work must cover the combustible ranges of the used fuel. The flammability limit of fuels depends on parameters such as temperature, pressure, fuel type, ignition source, and others, but that is not absolute. The lower and upper flammability limits of the kerosene are 0.65 and 1.45, respectively [

16].

4.1. Influence of the Velocity Magnitude of Air and Fuel Inlets

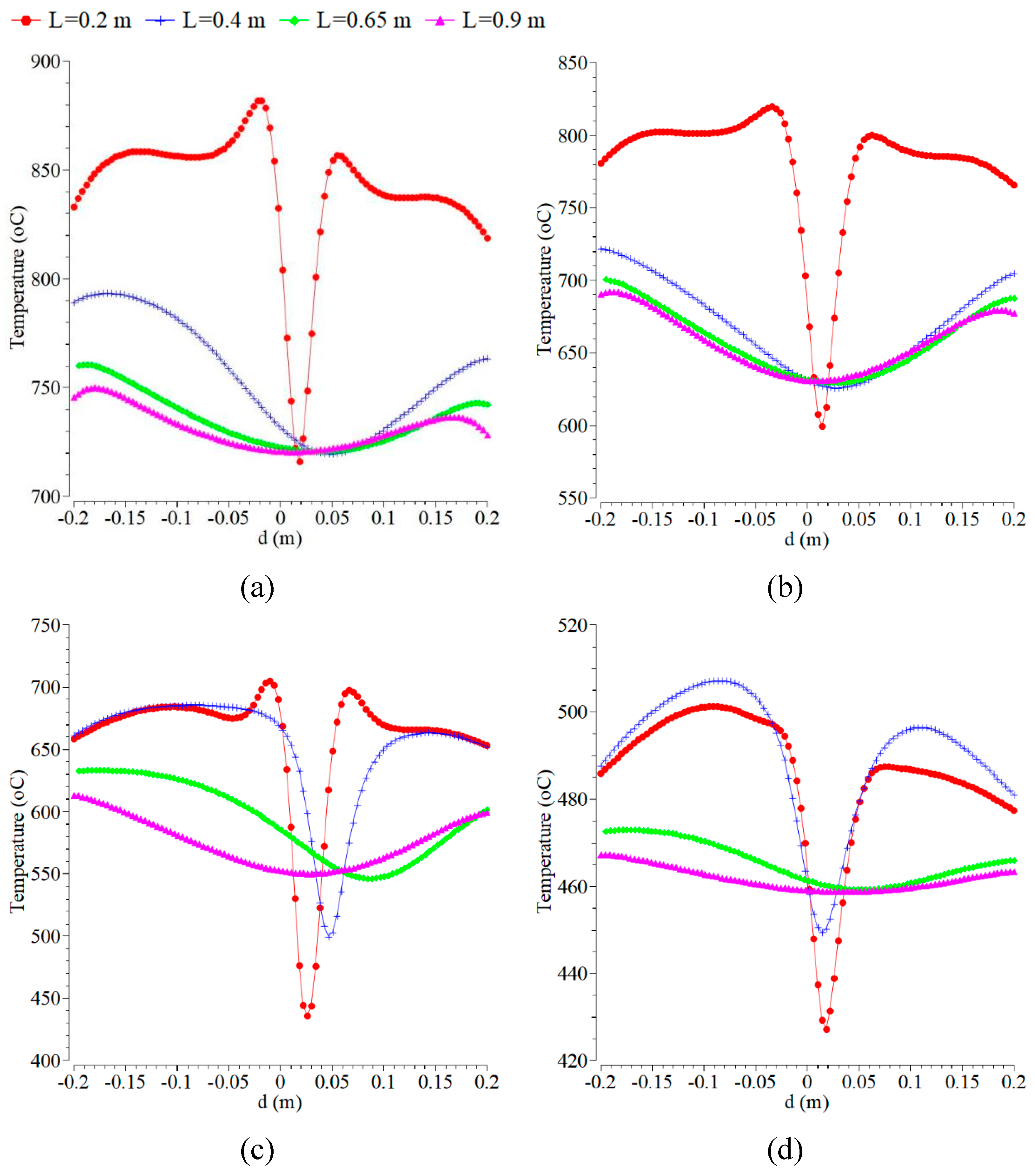

Figure 2 presents the contours of temperature with the inlet temperature, and the mass fraction of oxygen in the inlet flow of fuel and air was kept constant at 300 K and 0.21%. As shown by

Figure 2, the higher contour temperature for the same conditions is taking place at the magnitude velocity of the inlet fuel of 0.05 m/s in comparison to all of the others. As is expected from this measurement, the temperature along the centerline is low and does not show a constant value. It is also shown that the temperatures at axial distances from 0 cm to 50 cm, on the other hand, are more uniform and higher. This result is a little different from the previous research work in [

3], where the temperature along the centerline showed a constant value of 1775 K, indeed at axial distances > 80 mm. The plots of temperature for the reference case in

Figure 2 show that the maximum temperature takes place in the flame zone, namely around the centerline of the combustion chamber, as indicated in [

40].

The temperature along the axial distances at various radial distances shows a constant value of 1200 for the axial distance >200 mm indeed. The flame shape for all cases is predominantly symmetric about the y=0 mm plane with respect to the centerline of the combustion chamber for all axial distances towards the outlet. The results agree with the experiments in [

36,

41]. Some research results have obtained an asymmetric flame shape or disagreed with the symmetric flame, as mentioned in [

3]. The case of the transition from symmetric to asymmetric flame shape is seen in the present simulation of the NO mass fraction. By increasing fuel velocity, which can enhance the entrainment of flue gas, as well as the high velocity, can lead to a large amount of entrainment of flue gas, which can create a lower O

2 concentration [

42]. This result is different from the previous research, where the temperature of the centerline in the combustion zone and preheat zone increased slightly by applying a microporous combustor [

43].

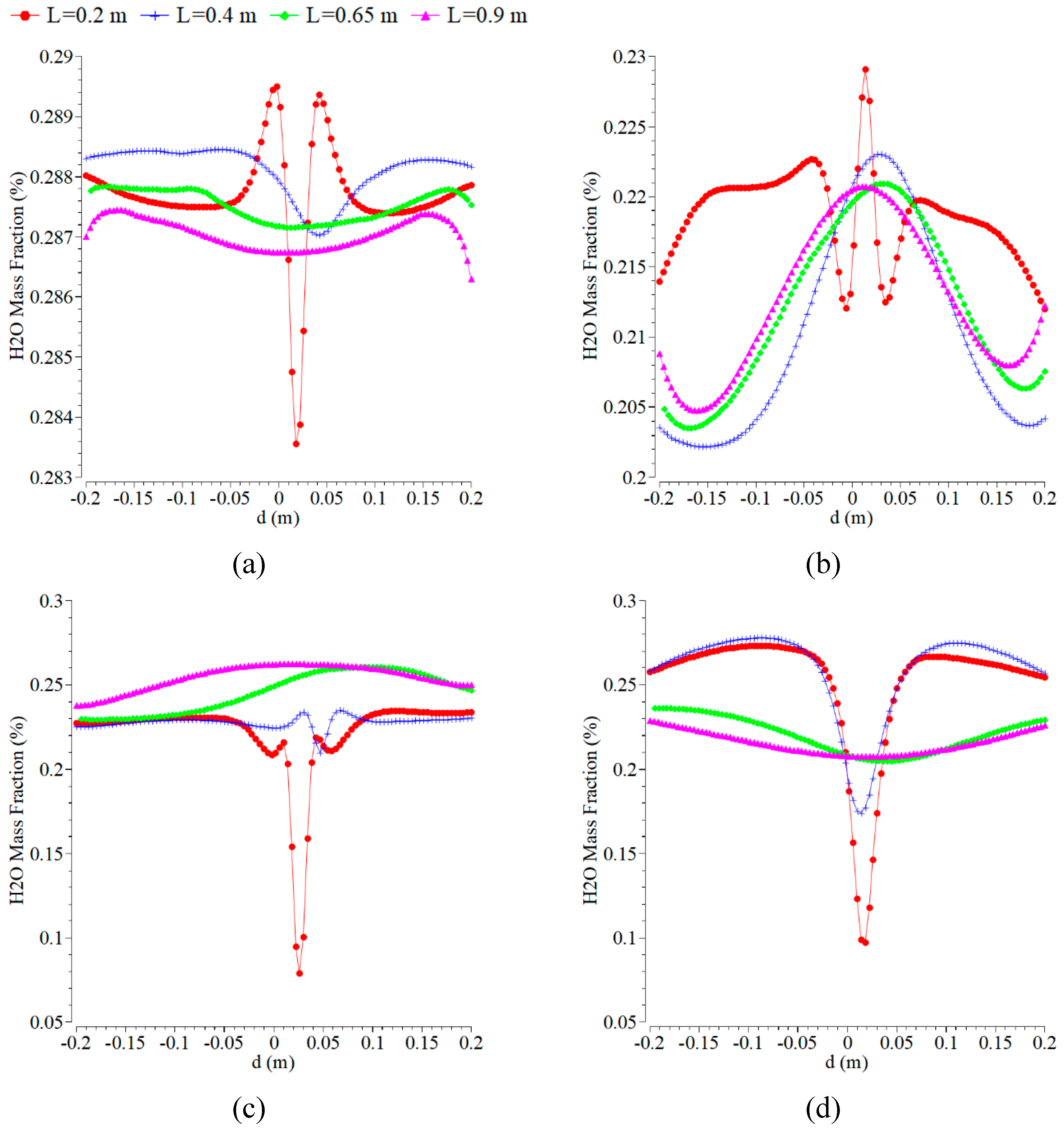

The H

2O contours, as shown in

Figure 3, under various air magnitude velocities, with the fuel velocity magnitude kept constant at 0.5 m/s. The inlet temperature was kept constant at 300 K by using the mass fraction of oxygen of 0.21. The maximum mass fraction of H

2O takes place almost near the inlet air at all of those magnitudes of velocity. The complete combustion requires enough oxygen, which is provided near the air inlet. The location close to the air inlet is in good agreement with the other mass fraction results. A more visible discrepancy is noticed at the far-field location, as explained by the higher predicted temperature. The characteristics of the H

2O flame contour are different at each of the various magnitude velocities and are very lovely at 0.0005 m/s.

The temperature contours inside the combustion chamber are not uniform, so the evaluation of temperature contour uniformity is usually needed by determining the pattern factor (PF). The parameter, which is defined by Eq. (52), is determined by measuring the homogeneity of the combustion chamber temperature and the maximum temperature contour. The value of PF is closer to 1, which indicates that the outlet temperature contour distribution of the combustion chamber is more uniform [

40].

where T

in is the average inlet temperature of both air and fuel,

is the maximum temperature at the combustor outlet, and

is the average temperature contour at the outlet combustion chamber of the burner.

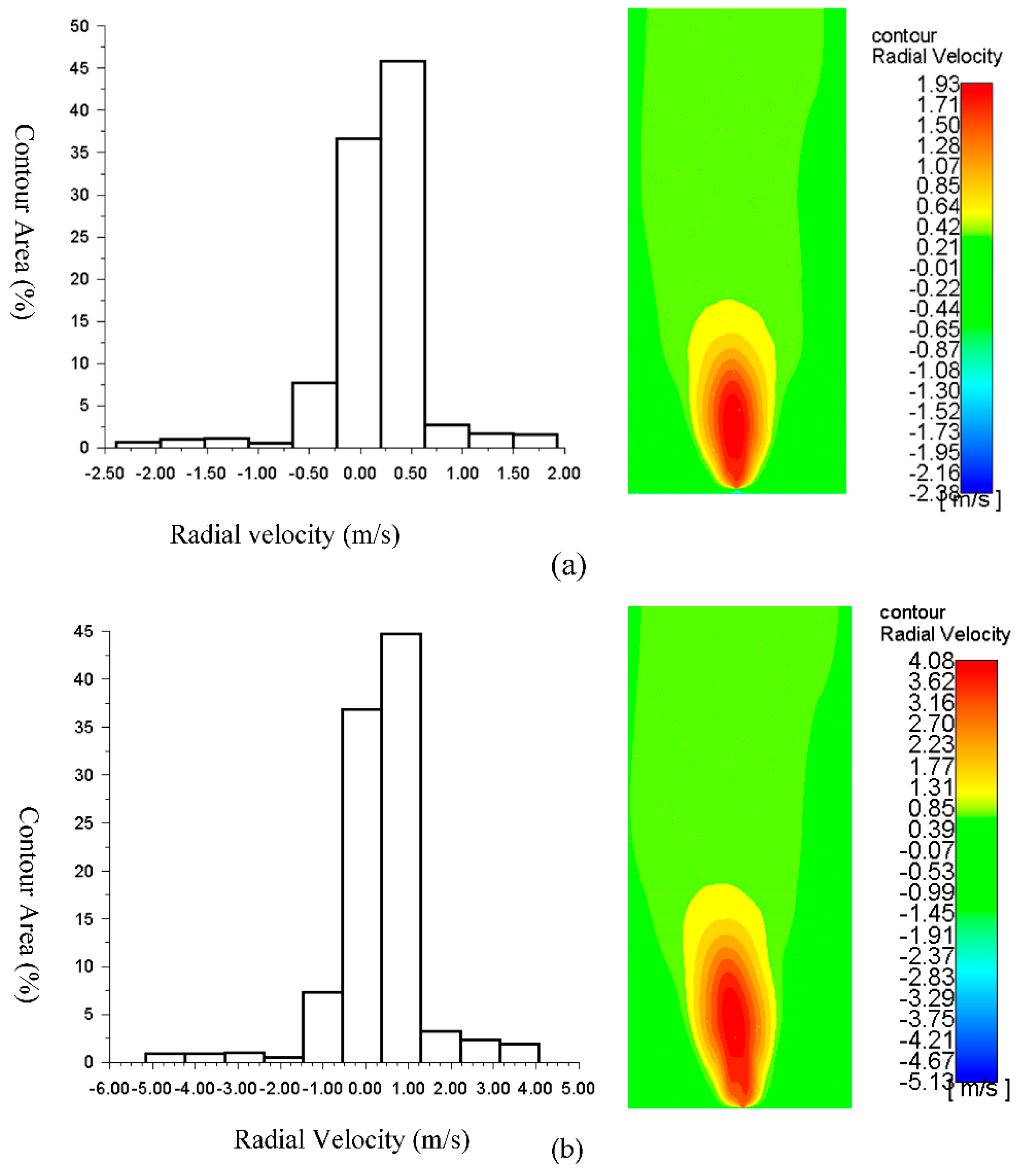

The flame contour area of radial velocity, as displayed in

Figure 4 at a magnitude velocity of 0.1 m/s (inlet temperature =300

oC), is better than the other contour. For the boundary condition at the inlet fuel of 0.01 m/s and temperature of 700 K, the radial velocity of 0.25-0.75 m/s dominates the flame contour with an area of more than 47%, and the maximum radial velocity is 1.93 m/s with the flame contour area of around 2.5%. For the boundary condition at the inlet fuel of 0.1 m/s and temperature of 300 K, the velocity of 0.5-1.4 m/s dominates the contour, with the area about 45% and the radial velocities of 3-4 m/s are about 5% of the flame contour area. The velocity of 0 m/s to 1 m/s dominates the flame contour with an area of more than 70% of the boundary condition at the inlet fuel of 0.1 m/s and temperature of 300 K. The radial velocities of 4 m/s to 5 m/s are around less than 5% of the flame contour area for this condition.

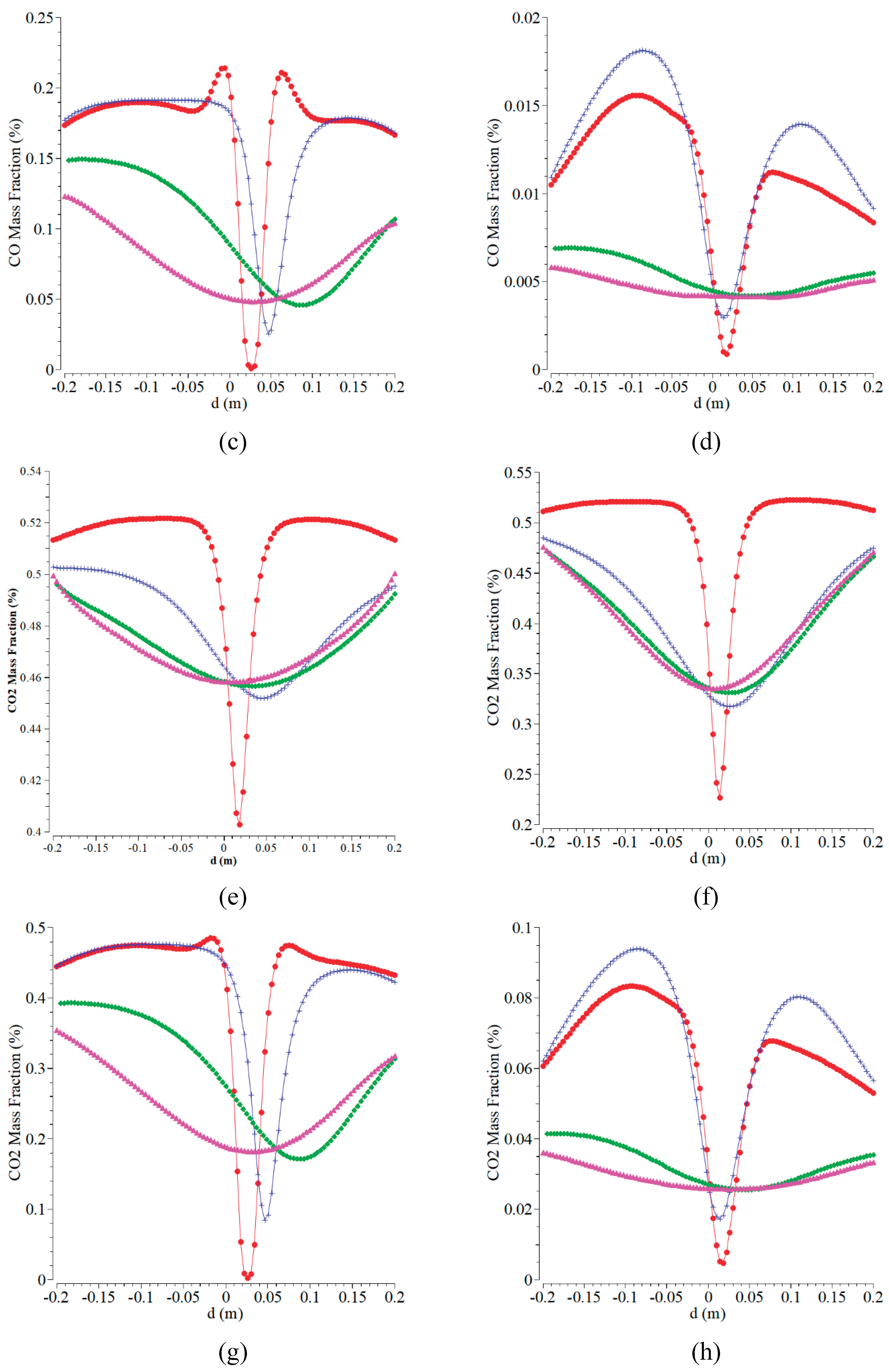

Figure 5(a-5d) are displaying the mass fraction of CO. An asymmetric curve for all the fuel inlets and four axial distances is almost formed. The lowest CO is obtained at the fuel inlet of 1.5 m/s. The concentration of CO is lower than that of the other cases of fuel inlets. At the centerline of radial position, CO gets a significant decrease for all the cases except for the case of B. The lower CO indicates a better combustion process for the operating condition, and it is expected to take place to achieve a higher temperature. CO is an intermediate product of gas emission formed and further oxidized into CO

2. A chemical combustion reaction between air and fuel results in the following products:

and

. CO can be detected in flue gases. It is due to the following reasons, such as not enough residence time for both the air and fuel to react and burn in a combustor. The burner chamber is too cold. The air-fuel ratio is out of stoichiometry (the ideal mixing ratio). The fuel and air in a burner chamber are insufficiently mixed [

34,

35].

Figures (5e-5h) are the CO

2 mass fraction versus radial and axial distances for various boundary conditions of fuel inlet at a constant air inlet of 0.5 m/s. Both the temperature fuel and temperature air inlets are kept at 300 K. The curves for all the fuel inlets and four axial distances form a symmetric curve with a similar trend when the radial distance of 0 m is used as a centerline. The curves obtained almost resemble the CO mass fraction. The highest CO

2 mass fraction is obtained at the fuel inlet of 0.05 m/s by the highest concentration of around 0.52%. With the centerline of radial position, CO

2 shows a significant decrease in all the cases. The higher CO

2 indicates a complete combustion process for the operating condition. The characteristic of the CO

2 contour is close to all of those. CO

2 forms near the oxygen inlet because at this place, where the oxygen provided is more than at the wall and the center of the combustion chamber. This current research agreed with previous work in [

46].

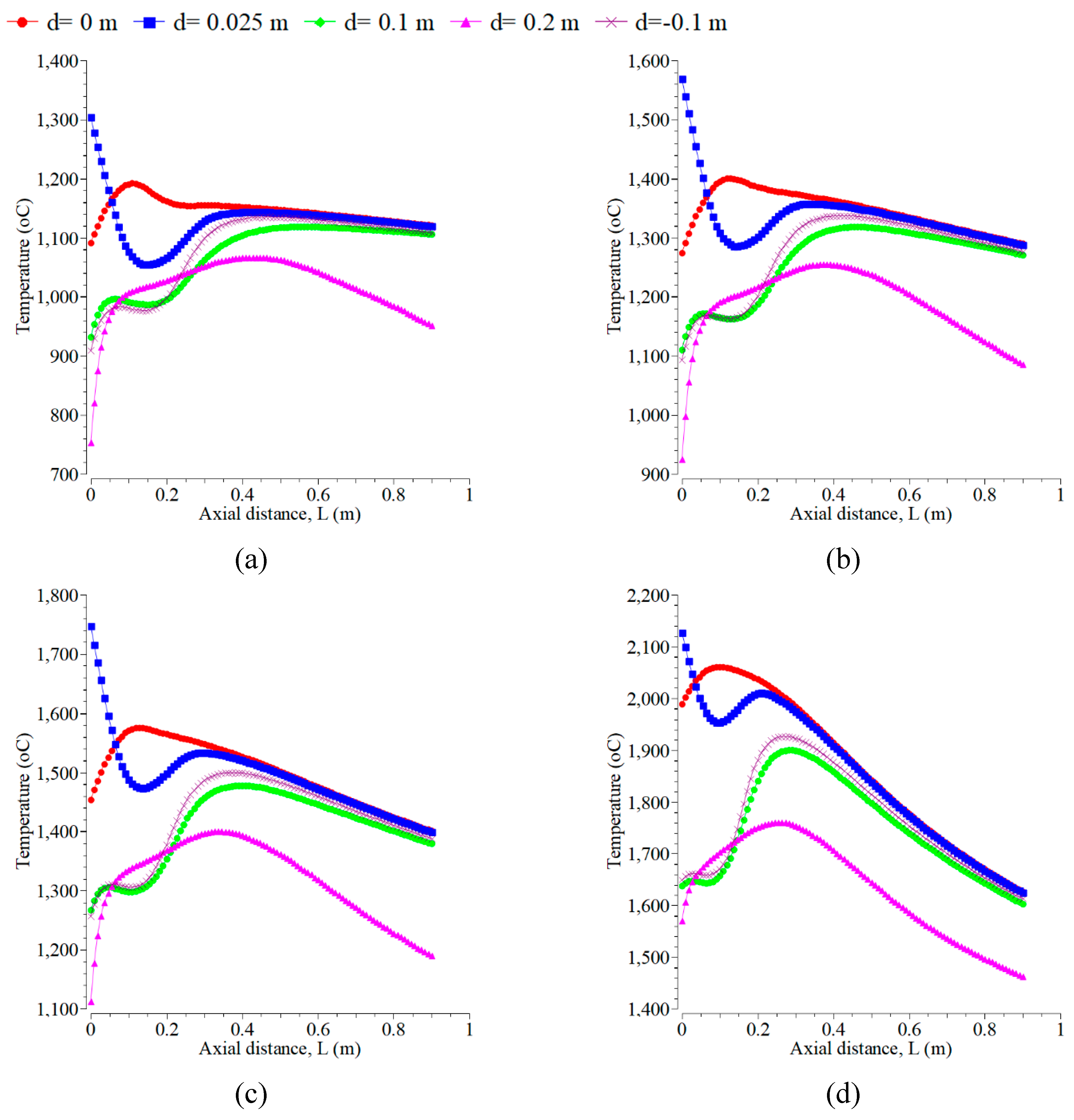

4.2. Influence of Inlet Temperature

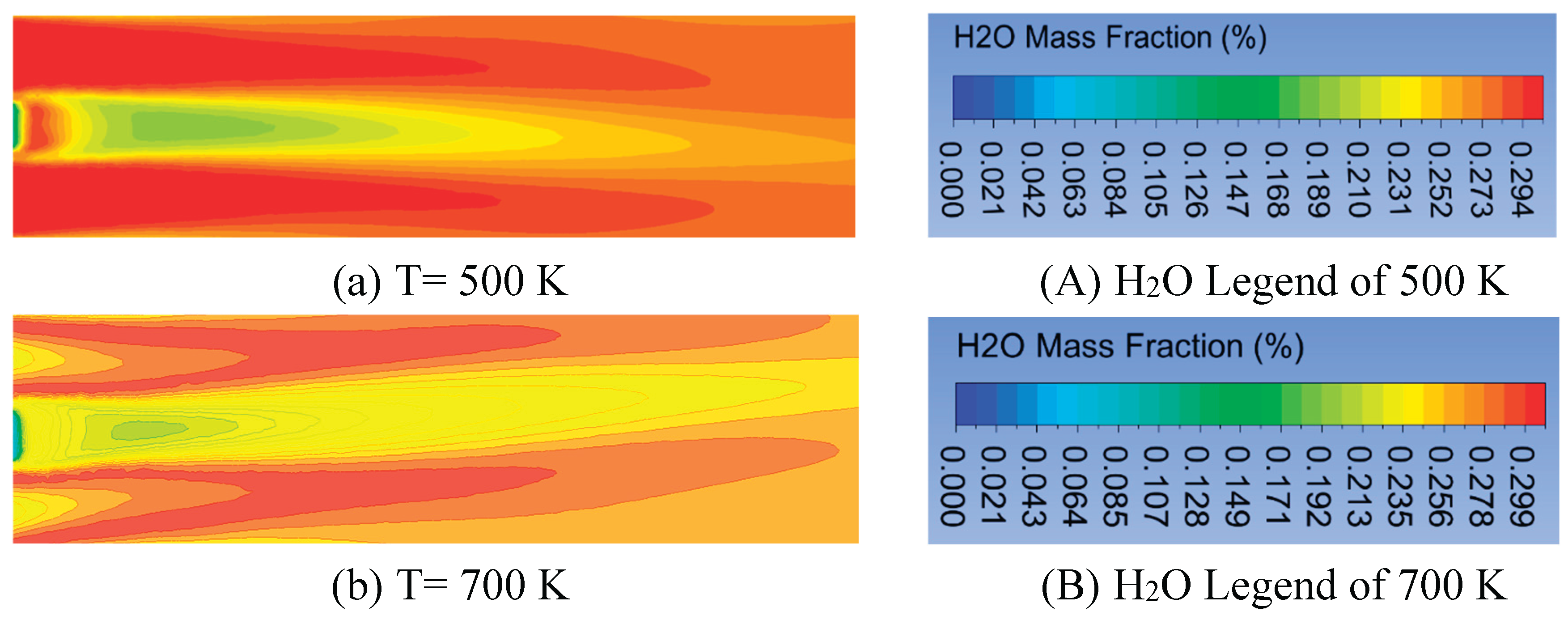

In this section, the volume fraction of oxygen is kept constant at 0.21% with an air velocity of 0.5 m/s. The mass fraction and magnitude velocity of kerosene kept constant are 1% and 0.01 m/s, respectively. The effects of the inlet temperature of fuel and air on temperature distribution inside the combustion chamber at 500 K, 700 K, 900 K, and 1500 K are as shown in

Figure 6. The increase of which can raise the combustion chamber temperature to all the selected radial positions. The maximum temperature occurs at the inlet temperature of 1500 K, followed by 900 K, 700 K, and 500 K. The chemical reaction occurs rapidly at a higher temperature, and the mixing of fuel and oxygen is faster [

32]. The increment of the maximum temperature from 500 K to 900 K is 280 K, from 1573 K to 1853 K. However, it is 170 K from 1853 K to 2023 (lower at 700 K to 900 K). Furthermore, from 900 K to 1500 K, the increment is higher, 375 K from 2023 K to 2398 K. This is due to the higher inlet temperature, which results in more uniform temperature distribution. A similar result is shown in reference [

42]. The configuration of flame forms a symmetry flame, which occurs at the radial positions of 0.1 m and -0.1 m for the temperature inlet. The temperature distributions at the centerline and close to the combustor centerline are hotter for all the inlet temperatures than at other radial positions. However, that is colder when far from the centerline. This yield differs from the research in [

18].

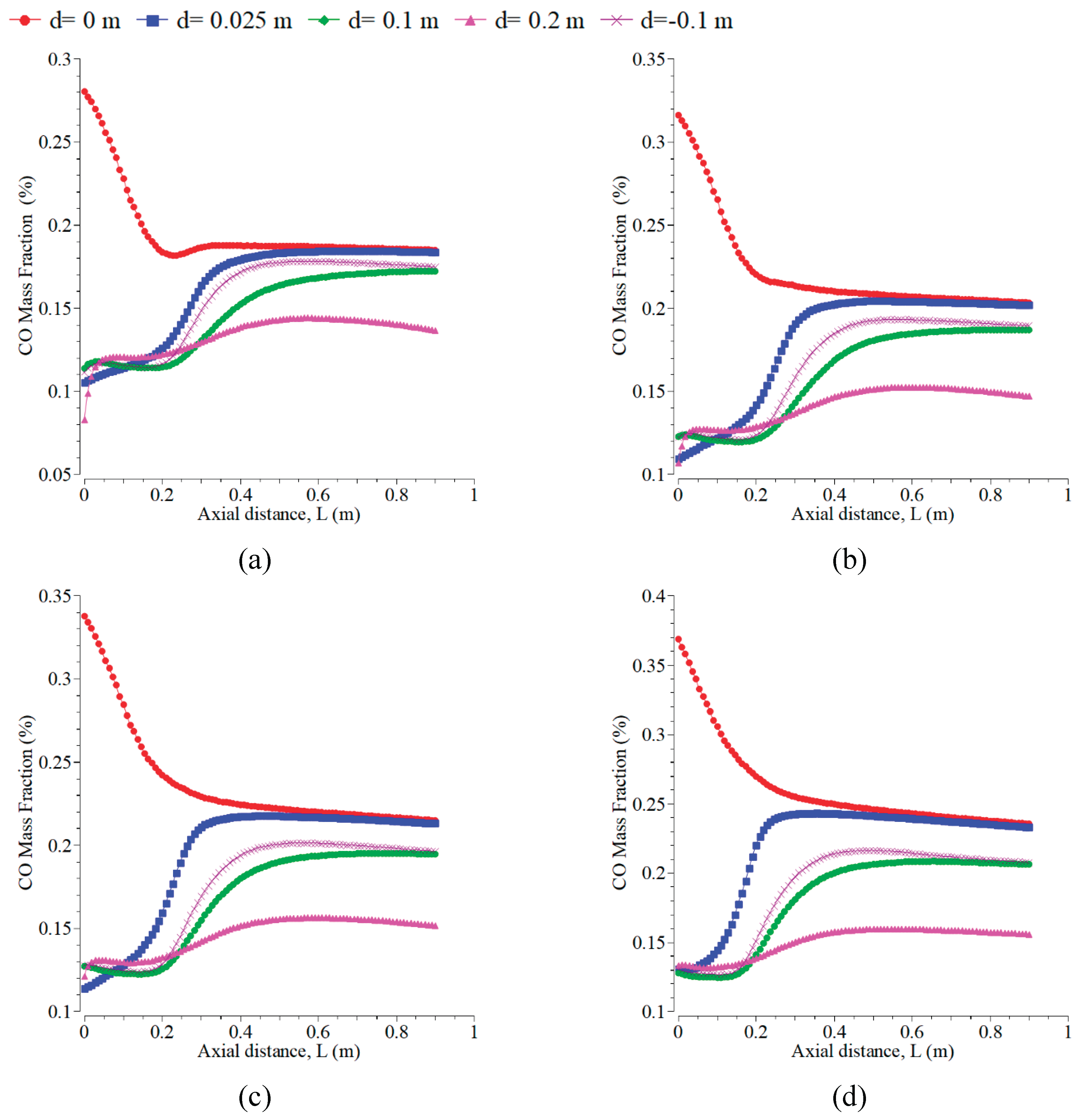

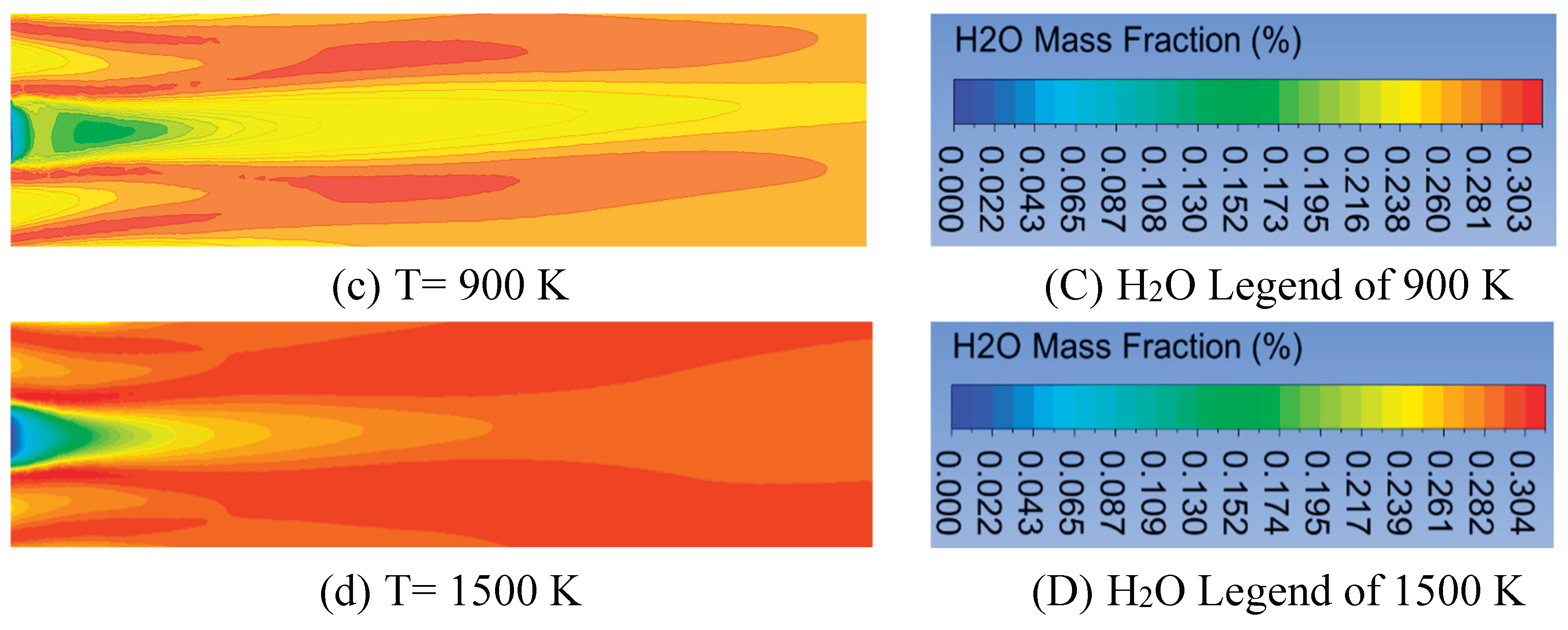

The inlet temperature addition of 500 K to 1500 K can raise the CO mass fraction, as shown in

Figure 7. The trend of the CO curve is very smooth, like taking place on temperature profiles in

Figure 6. CO at the radial position of 0 m is prominent and significantly decreases up to 0.2 m axial distance. However, at the other radial positions, the values increase significantly, occurring for all the inlet temperatures. The levels of CO emission are almost constant at the axial distances > 0.4 m. The temperature range from 300 K to 1800 K corresponded to the prediction of CO, whereas the oxidation of CO dominated at temperatures above 1800 K [

47].

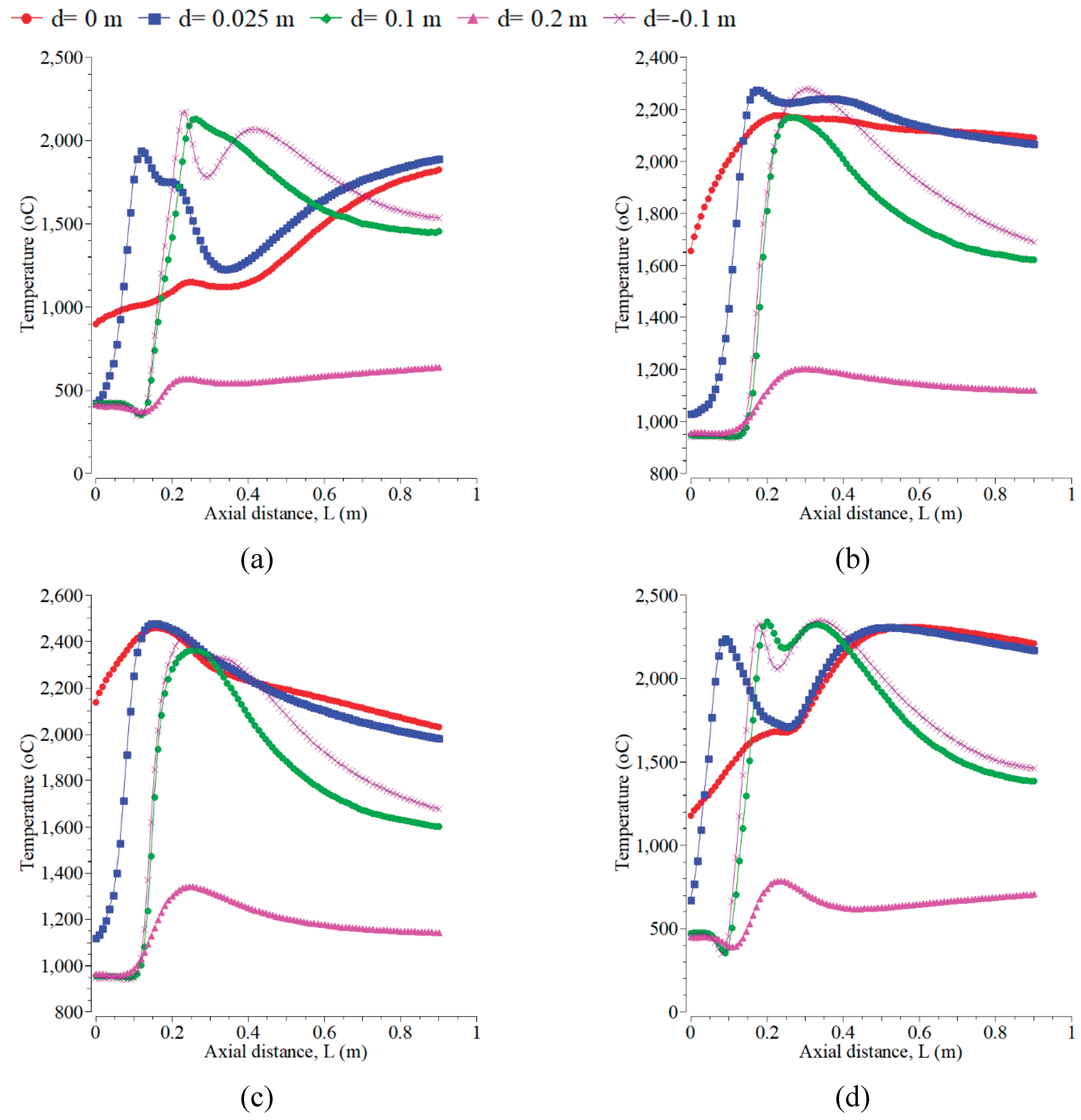

Figure 8 displays CO

2 mass fraction curves versus the axial direction at varying inlet temperatures from 500 K to 1500 K. Increasing inlet temperature can decrease the CO

2 mass fraction for all radial positions. This result differs from the research in [

34,

37]. The trend of the CO

2 curve is almost similar to that of H

2O. The CO

2 decreases in all the radial directions except at d=0 m. The emission of CO

2 is more significant than CO because the concentration of oxygen is more dominant in forming CO

2 than other emissions. The level of CO

2 can change significantly up to the axial distances of 0.2-0.4 m because the oxygen is still more available around the positions. CO

2 is almost constant at the axial distances > 0.4 m for all the cases. The curves of CO

2 for all inlet temperatures under the radial positions of 0.1 m and -0.1 m show slight differences and form a symmetrical flame.

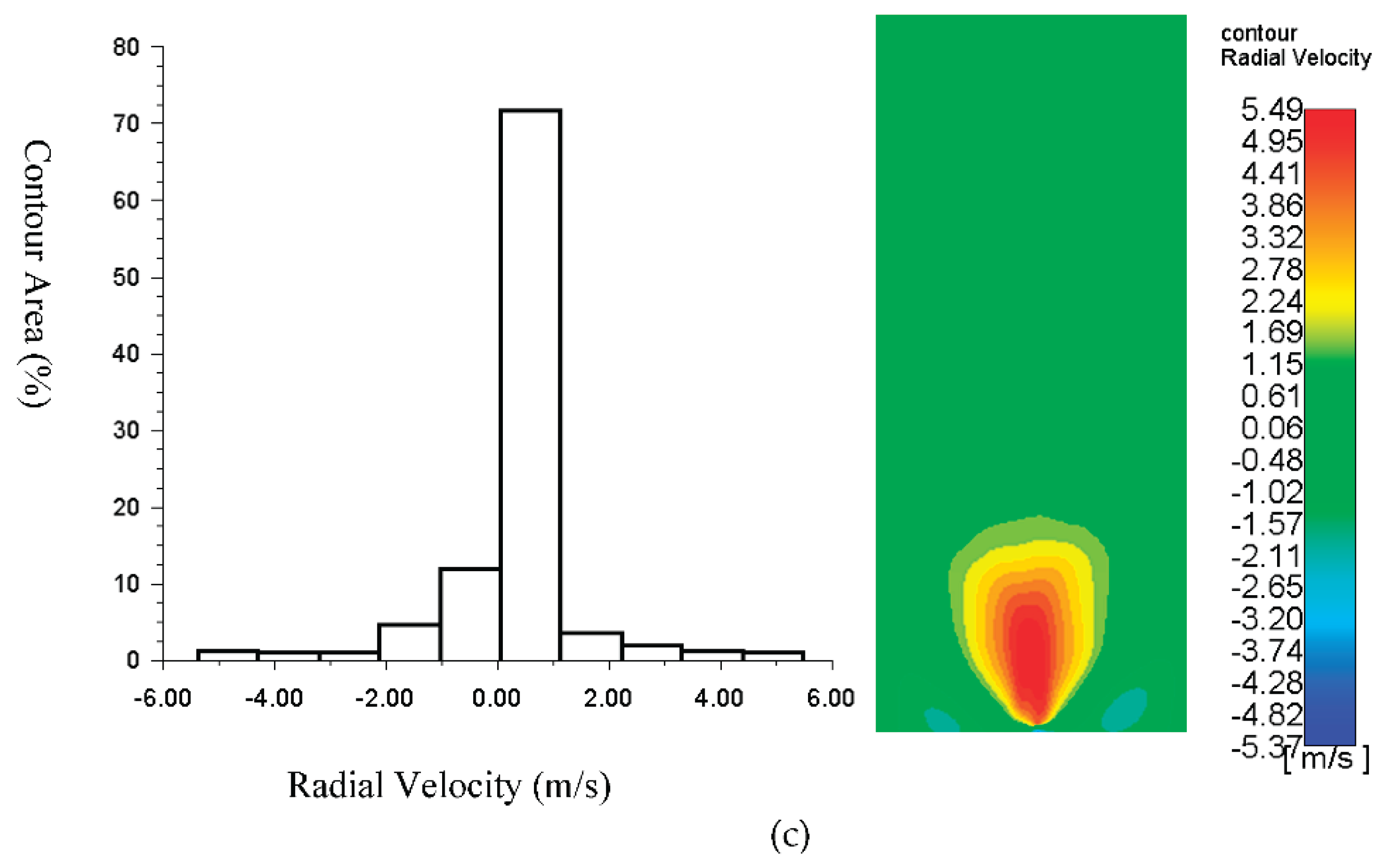

Figure 9 shows the H

2O mass fraction by blowing up air and fuel contours. The H

2O mass fraction almost forms a symmetry flame configuration. The higher H

2O concentration is obtained at the air inlet because forming this gas emission requires enough oxygen. The rise in inlet temperature can increase the CO

2 level, but it is not significant.

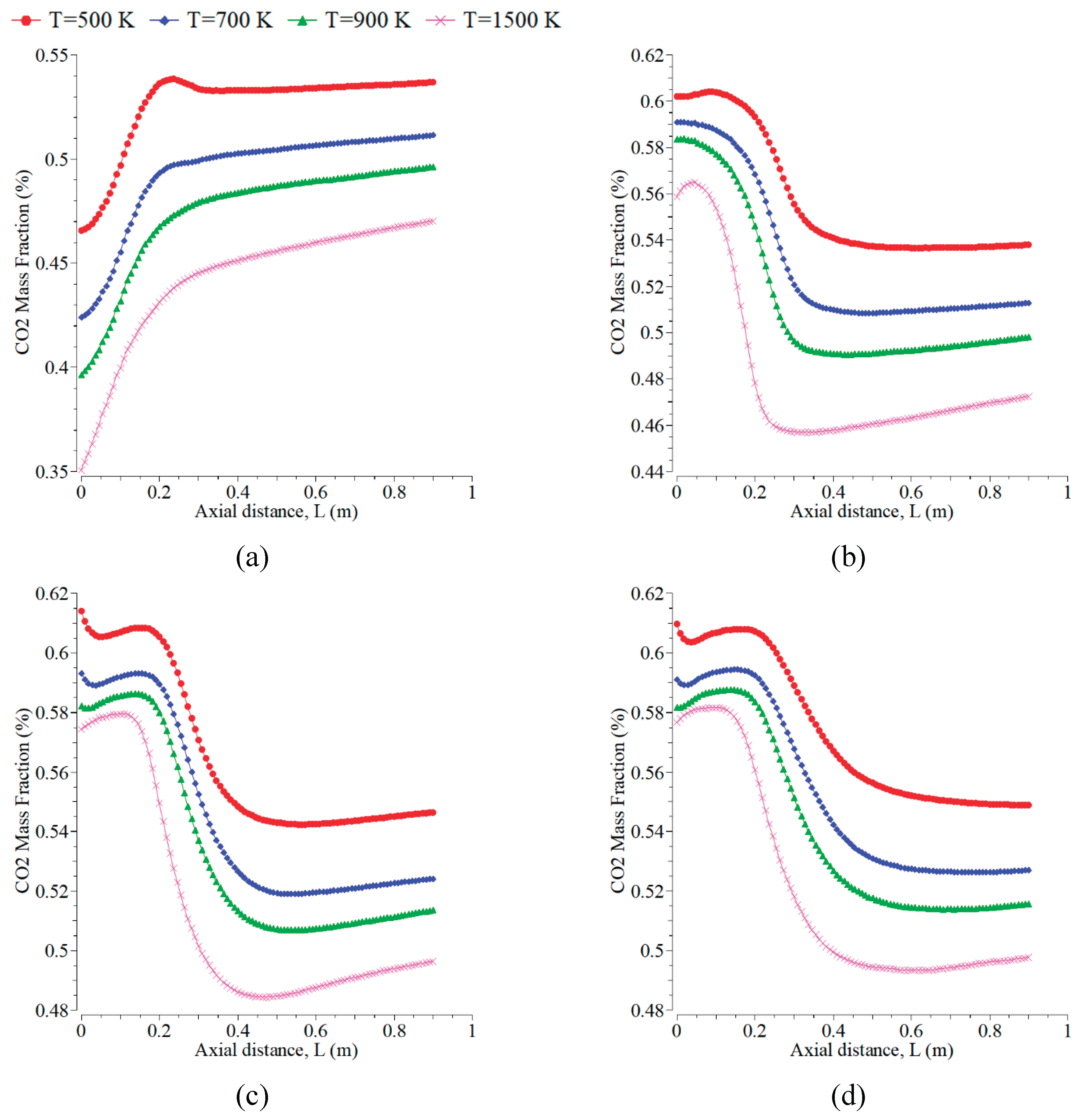

4.3. Influence of Oxygen Mass Fraction

The current analysis compares previous research and simulation results. Results display different study fields of various oxygen mass fractions. The velocity magnitude and inlet temperature of air kept constant are 0.5 m/s and 300 K, respectively. For the fuel inlet, the values provided are kept at 0.01 m/s and 300 K, respectively.

Figure 10 shows the effect of oxygen on temperature distribution inside the combustion chamber under various boundary conditions of the oxygen from 0.21% to 0.8 %. Know that increasing the oxygen concentration can raise contour temperatures. The higher oxygen concentration can result in a more uniform temperature distribution by yielding perfect combustion. The simulation results are similar to reference [

42]. Said that the oxygen reduction can affect the field of temperature as a research in [

26] by applying various oxygen concentrations of 21%, 18%, and 15%. The results agree with a reference [

47] for the temperature contour, with the radial position of 0.2 m closer to the wall temperature.

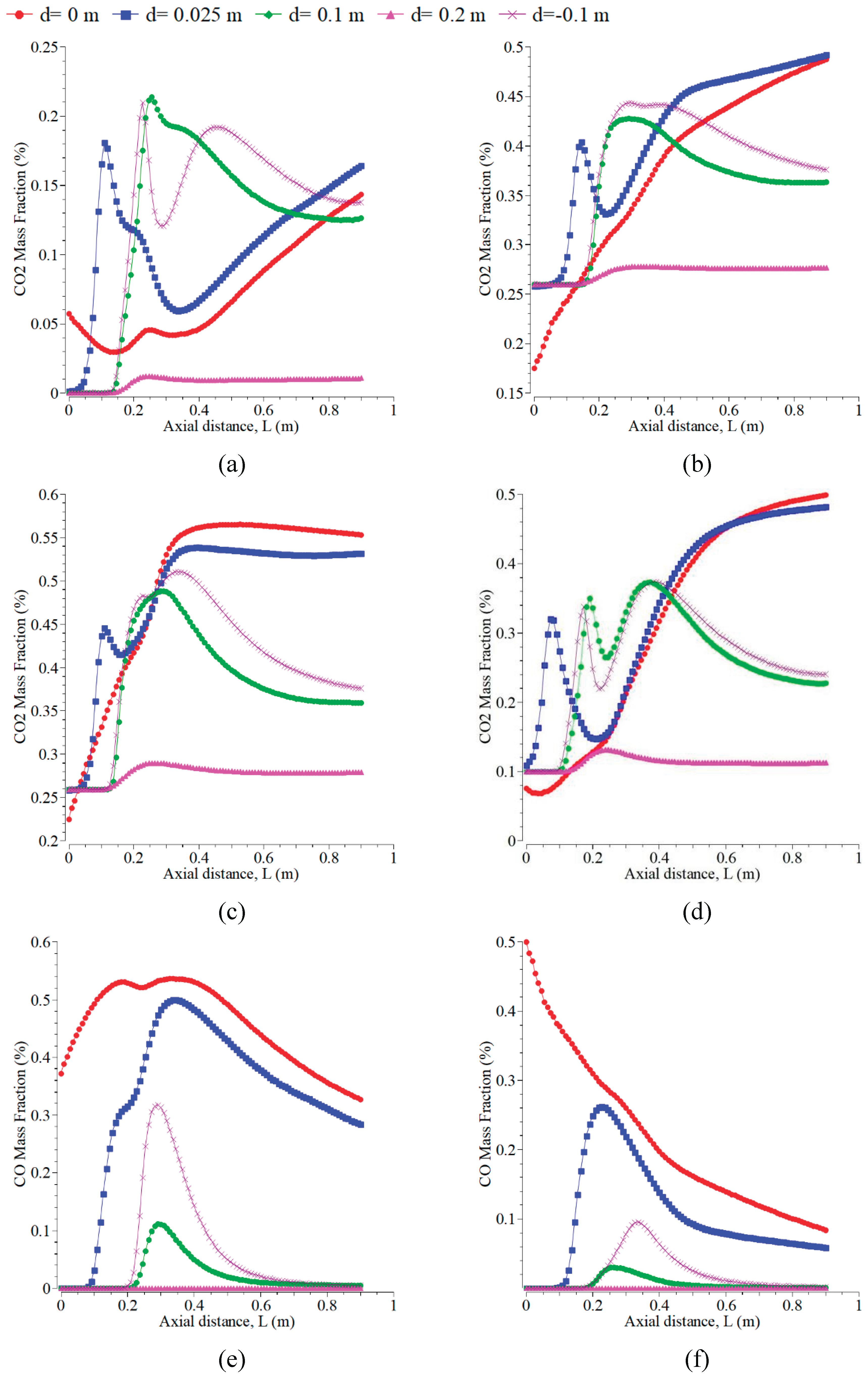

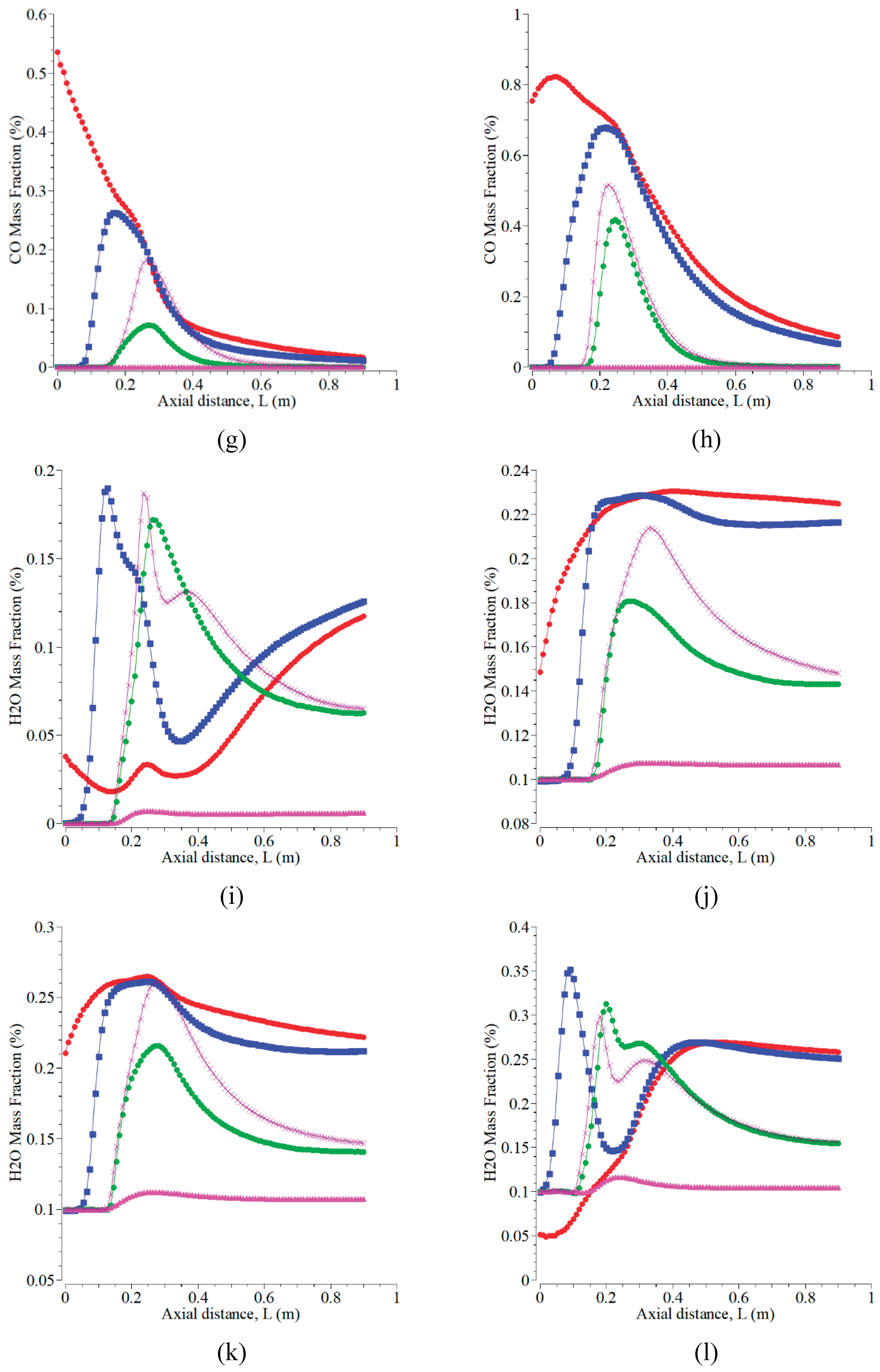

This simulation not only provides the flame temperature distribution contours as a result of the combustion process, but also provides the gas emissions, as presented in

Figure 10 and

Figure 11. The effects of oxygen are that the emissions of H

2O and CO

2 increase, while the emissions of CO and NO decrease. The predicted gas emission results agree well with theory. The addition of oxygen level forms CO decreases, and CO

2 increases because the perfect combustion takes place with enough oxygen [

44,

48]. The rise of temperature and oxygen for a stoichiometric burning can increase the amount of CO

2 [

39]. The results of NO

x and CO decreased up to nearly zero, but CO

2 increased slightly under the oxygen concentrations of 18% and 15% by volume [

26]. The formation of NOx depends upon reaction duration, inlet temperature, and oxygen availability in the combustor [

49]. NOx is reduced by dual-stage low premixed (DLF) flame technology because DLF controls combustion temperature by limiting the use of the equivalence ratio of premixed gas [

50]. The level of NOx is dependent on the oxygen concentrations, and the CO emission is dependent on the air-fuel ratio [

51].

Carbon monoxide (CO) is available in combustion gas as a result of the partial oxidation of carbon content in fuel. The presence of which in gas emission is an indication of low combustion efficiency because it is not completely oxidized to CO

2. The form of which can reduce the thermal combustion efficiency, of course, which can increase fuel consumption. CO is present more when the combustion process is carried out with too little air than required stoichiometry, and therefore, the oxygen is insufficient for completing carbon oxidation reactions. The combustion process occurs with excess air/oxygen higher than the stoichiometric requirement [

52].

The geometric size of the combustion chamber influences gas emissions. The emission of CO is higher for a small combustion chamber than for a large combustion chamber [

48]. The higher temperature of the flame, which appears in forming H

2O and CO

2, is more dominant because the synthesis of the emissions yields an enthalpy of the combustion reaction higher than that of CO. Oxygen provided must be more than required to increase fuel conversion efficiency to gas emissions. The emissions of CO

2 and H

2O, as shown in

Figures 11 (a-d), generally increase with the addition of the oxygen mass fraction at all the selected lines, except in the case of

Figure 11d. The highest CO

2 and H

2O emissions take place for the cases of

Figures 11C and 11L, respectively. Those cases describe the complete combustion for these operating conditions and can be used in the real application, as proved by the flame temperature in

Figure 10. The flame configuration of CO

2 and H

2O almost forms a symmetrical shape, especially when the axial position is less than 0.25 m. The values of CO

2 range from more than 0 to 0.6, which are more similar to the results in [

12].

For an excellent understanding,

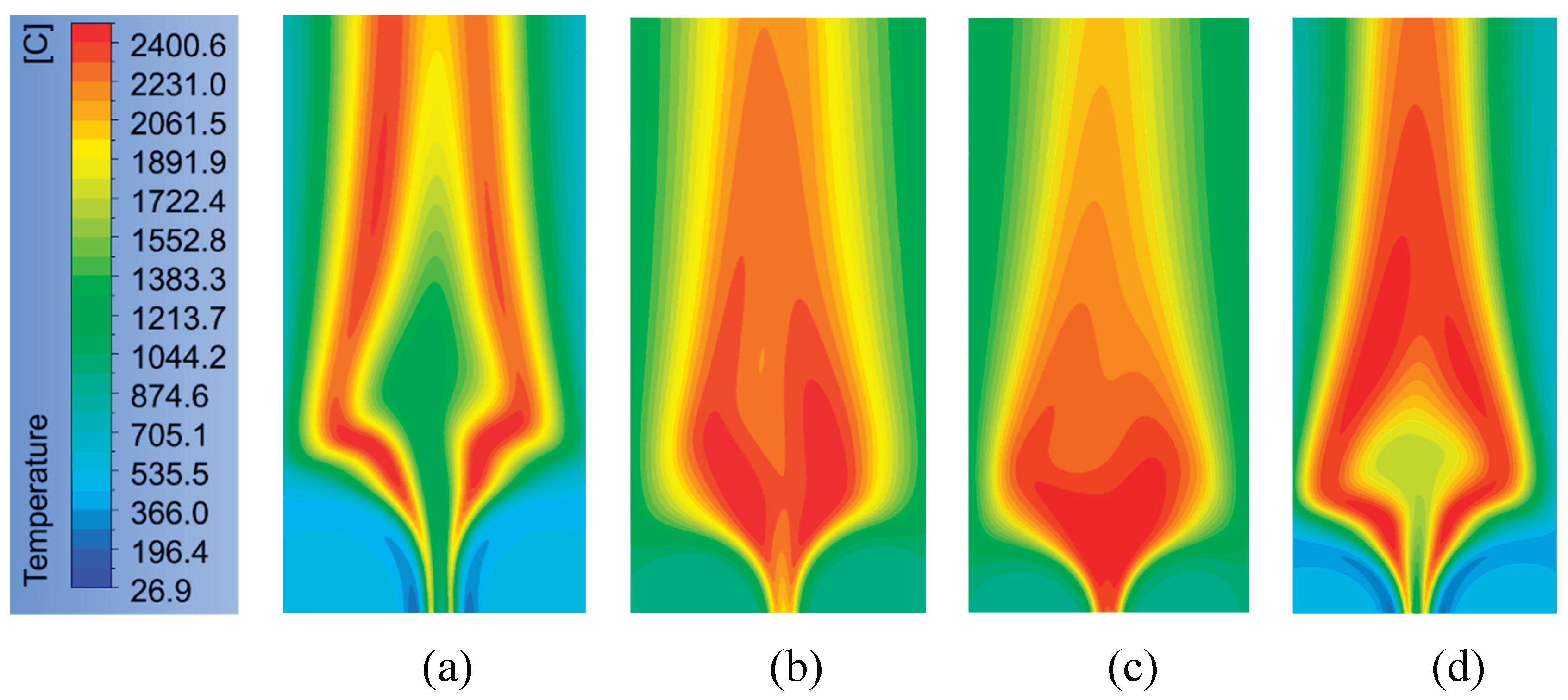

Figure 12 displays the flame temperature contours at various oxygen mass fractions. The addition of oxygen mass fraction can increase the flame temperature in the combustion chemical reaction. That can change contour form, contour area, and flame stability of temperature. For the same oxygen concentration, as shown in

Figure 12 (a-b), it is obvious that both have sharp differences. Saying the temperature contour in

Figure 12b gives better results with the area of 2061 to 2400

oC, which is wider than those of

Figure 12a. The condition, as shown in

Figure 12b, involves an inert gas of CO that can react with enough oxygen to form CO

2. Another reason for this case is to predict the effect of the transport direction of O

2 species on the near fuel distribution by an Injector.

The perfect combustion is more serious, taking place near the fuel injector area. The explanations proved, as shown in

Figure 12c, are forming a sharp difference when the presence of CO is neglected in the case of

Figure 12d. The condition in the case of

Figure 12d just only involves CO

2 and H

2O, so that the temperature contour shows enough difference compared with the cases of

Figure 12 (b-c). Displaying also that temperatures near the fuel inlet are more significant than the air inlet. The temperatures near the nozzle are generally higher for both axial and radial temperature profiles; those results agree well with previous research in [

3].

5. Conclusions

The simulation results of operating conditions of various inlet temperatures, magnitude of velocity, and the mass fraction of oxygen are compared with the prior research results. The given tests to the combustion chamber using kerosene fuel have resulted in better performance when applying inlet velocity magnitudes for fuel=0.01 m/s and air=0.5 m/s. The flame shape for all the cases of inlet velocity is predominantly symmetric about the y=0 mm for all the axial distances towards the outlet. The maximum mass fraction of H2O takes place almost near the inlet air at all of those magnitudes of velocity. The characteristics of the H2O flame contour are different at each of the various magnitude velocities and very lovely at 0.0005 m/s. An asymmetric curve for all the fuel inlets and four axial distances forms on the mass fraction of CO, with the lowest CO mass fraction obtained at the fuel inlet of 1.5 m/s. The curves obtained are almost similar to the CO mass fraction. The highest CO2 mass fraction is obtained at the fuel inlet of 0.05 m/s by the highest concentration of around 0.52%. The curves for all the fuel inlets and four axial distances form a symmetric curve with a similar trend when the radial distance of 0 m is the centerline.

The increase of inlet temperature can raise the combustion chamber temperature to all the selected radial positions, and the maximum temperature takes place at the inlet temperature of 1500 K, followed by 900 K, 700 K, and 500 K, respectively. The CO2 curve trend is almost similar to H2O. The increase in the inlet temperature of air and fuel can raise the CO mass fraction, but can decrease CO2. Higher oxygen levels leading to a higher peak temperature in the flame, which can reduce fuel consumption. The inert gas, CO, can widen peak temperature areas. Adding the mass fraction of oxygen can raise the combustion flame temperature and can change the contour form, contour area, and flame stability with temperature. The inert gaseous concentrations can influence gas temperatures and the emissions of CO2, CO, and H2O in the combustion chemical reaction. Adding oxygen, the emissions of H2O and CO2 increase, while the emission of CO decreases. The predicted gas emission results agree well with theory. The highest CO2 and H2O emissions occurs for the cases of C and L, respectively. Those cases can be selected in real applications, as proved by the flame temperature. The emissions of CO2 and H2O form a symmetry flame when the axial position is less than 0.25 m.

Figure 1.

Diffusion burner.

Figure 1.

Diffusion burner.

Figure 2.

Radial temperature profile at the axial positions of 0.2, 0.4, 0.65, and 0.9 m with the velocity magnitude of the air inlet of 0.5 m/s and various fuel inlets of: (a) 0.05 m/s; (b) 0.1 m/s; (c) 0.3 m/s; and (d) 1.5 m/s.

Figure 2.

Radial temperature profile at the axial positions of 0.2, 0.4, 0.65, and 0.9 m with the velocity magnitude of the air inlet of 0.5 m/s and various fuel inlets of: (a) 0.05 m/s; (b) 0.1 m/s; (c) 0.3 m/s; and (d) 1.5 m/s.

Figure 3.

Comparison of the contour of mass fraction of H2O at the axial positions of 0.2, 0.4, 0.65, and 0.9 m with the velocity magnitude of the air inlet of 0.5 m/s and various fuel inlets: (a) 0.0005 m/s; (b) 0.1 m/s; (c) 0.3 m/s; and (d) 1.5 m/s.

Figure 3.

Comparison of the contour of mass fraction of H2O at the axial positions of 0.2, 0.4, 0.65, and 0.9 m with the velocity magnitude of the air inlet of 0.5 m/s and various fuel inlets: (a) 0.0005 m/s; (b) 0.1 m/s; (c) 0.3 m/s; and (d) 1.5 m/s.

Figure 4.

Contours of radial velocity at the velocity magnitude of the air inlet of 0.5 m/s and the fuel inlets of: (a) 0.01 m/s, Tin= 700 K; (b) 0.01 m/s, Tin= 300 K; and (c) 0.1 m/s, Tin= 300 K.

Figure 4.

Contours of radial velocity at the velocity magnitude of the air inlet of 0.5 m/s and the fuel inlets of: (a) 0.01 m/s, Tin= 700 K; (b) 0.01 m/s, Tin= 300 K; and (c) 0.1 m/s, Tin= 300 K.

Figure 5.

The mass fraction contours of CO, CO2, and HCO at the axial positions of 0.2, 0.4, 0.65, and 0.9 m with the velocity magnitude of the air inlet of 0.5 m/s and varying the fuel inlets: (a) 0.05 m/s; (b) 0.1 m/s; (c) 0.3 m/s; (d) 1.5 m/s; (e) 0.05 m/s; (f) 0.1 m/s; (g) 0.3 m/s; (h) 1.5 m/s; (i) 0.05 m/s; (j) 0.1 m/s; (k) 0.3 m/s; and (l) 1.5 m/s.

Figure 5.

The mass fraction contours of CO, CO2, and HCO at the axial positions of 0.2, 0.4, 0.65, and 0.9 m with the velocity magnitude of the air inlet of 0.5 m/s and varying the fuel inlets: (a) 0.05 m/s; (b) 0.1 m/s; (c) 0.3 m/s; (d) 1.5 m/s; (e) 0.05 m/s; (f) 0.1 m/s; (g) 0.3 m/s; (h) 1.5 m/s; (i) 0.05 m/s; (j) 0.1 m/s; (k) 0.3 m/s; and (l) 1.5 m/s.

Figure 6.

The temperature distribution at the radial positions of 0, 0.025, -0.1, 0.1, and 0.2 m with the velocity magnitudes of the air inlet of 0.5 m/s and the fuel inlet of 0.01 m/s. The inlet temperatures of air and fuel are A. 500 K, B. 700 K, C. 900 K, D. 1500 K.

Figure 6.

The temperature distribution at the radial positions of 0, 0.025, -0.1, 0.1, and 0.2 m with the velocity magnitudes of the air inlet of 0.5 m/s and the fuel inlet of 0.01 m/s. The inlet temperatures of air and fuel are A. 500 K, B. 700 K, C. 900 K, D. 1500 K.

Figure 7.

CO mass fractions at the radial positions of 0, 0.025, -0.1, 0.1, and 0.2 m with the velocity magnitudes of the air inlet of 0.5 m/s and the fuel inlet of 0.01 m/s. The inlet temperatures of air and fuel are: (a) 500 K; (b) 700 K; (c) 900 K; (d) 1500 K.

Figure 7.

CO mass fractions at the radial positions of 0, 0.025, -0.1, 0.1, and 0.2 m with the velocity magnitudes of the air inlet of 0.5 m/s and the fuel inlet of 0.01 m/s. The inlet temperatures of air and fuel are: (a) 500 K; (b) 700 K; (c) 900 K; (d) 1500 K.

Figure 8.

CO2 mass fraction with the velocity magnitudes of the air inlet of 0.5 m/s and the fuel inlet of 0.01 m/s. The radial positions are: (a) 0 m; (b) 0.025 m; (c) 0.1 m; and (d) -0.1 m.

Figure 8.

CO2 mass fraction with the velocity magnitudes of the air inlet of 0.5 m/s and the fuel inlet of 0.01 m/s. The radial positions are: (a) 0 m; (b) 0.025 m; (c) 0.1 m; and (d) -0.1 m.

Figure 9.

Air and fuel contours of H2O mass fraction at the velocity magnitude of the air inlet of 0.5 m/s and the fuel inlet of 0.01 m/s with various inlet temperatures of air and fuel.

Figure 9.

Air and fuel contours of H2O mass fraction at the velocity magnitude of the air inlet of 0.5 m/s and the fuel inlet of 0.01 m/s with various inlet temperatures of air and fuel.

Figure 10.

Axial temperature profile at the radial positions of 0, 0.025, -0.1, 0.1, and 0.2 m with the velocity magnitude of the air inlet of 0.5 m/s and the fuel inlet of 0.01 m/s, using various oxygen mass fractions: (a) O2= 0.5%, N2= 0.5%; (b) O2= 0.5%, N2= 0.2%, CO2= 0.1%, CO= 0.1%, and H2O= 0.1%; (c) O2= 0.7%, CO2= 0.1%, CO= 0.1%, and H2O= 0.1%; (d) O2= 0.8%, CO2= 0.1%, and H2O= 0.1%.

Figure 10.

Axial temperature profile at the radial positions of 0, 0.025, -0.1, 0.1, and 0.2 m with the velocity magnitude of the air inlet of 0.5 m/s and the fuel inlet of 0.01 m/s, using various oxygen mass fractions: (a) O2= 0.5%, N2= 0.5%; (b) O2= 0.5%, N2= 0.2%, CO2= 0.1%, CO= 0.1%, and H2O= 0.1%; (c) O2= 0.7%, CO2= 0.1%, CO= 0.1%, and H2O= 0.1%; (d) O2= 0.8%, CO2= 0.1%, and H2O= 0.1%.

Figure 11.

The mass fractions of CO2, CO, and H2O at the radial positions of 0, 0.025, -0.1, 0.1, and 0.2 m with the velocity magnitudes of the air inlet of 0.5 m/s and the fuel inlet of 0.01 m/s, using various oxygen concentrations: (a; e; i) O2= 0.5%, N2= 0.5%; (b; f; j) O2= 0.5%, N2= 0.2%, CO2= 0.1%, CO= 0.1%, and H2O= 0.1%; (c; g; k). O2= 0.7%, CO2= 0.1%, CO= 0.1%, and H2O= 0.1%; (d; h; l). O2= 0.8%, CO2= 0.1%, and H2O= 0.1%.

Figure 11.

The mass fractions of CO2, CO, and H2O at the radial positions of 0, 0.025, -0.1, 0.1, and 0.2 m with the velocity magnitudes of the air inlet of 0.5 m/s and the fuel inlet of 0.01 m/s, using various oxygen concentrations: (a; e; i) O2= 0.5%, N2= 0.5%; (b; f; j) O2= 0.5%, N2= 0.2%, CO2= 0.1%, CO= 0.1%, and H2O= 0.1%; (c; g; k). O2= 0.7%, CO2= 0.1%, CO= 0.1%, and H2O= 0.1%; (d; h; l). O2= 0.8%, CO2= 0.1%, and H2O= 0.1%.

Figure 12.

Temperature contour at the velocity magnitudes of the air inlet of 0.5 m/s and the fuel inlet of 0.01 m/s with various concentrations of oxygen: (a) O2= 0.5%, N2= 0.5%; (b) O2= 0.5%, N2= 0.2%, CO2= 0.1%, CO= 0.1%, and H2O= 0.1%; (c) O2= 0.7%, CO2= 0.1%, CO= 0.1%, and H2O= 0.1%; (d) O2= 0.8%, CO2= 0.1%, and H2O= 0.1%.

Figure 12.

Temperature contour at the velocity magnitudes of the air inlet of 0.5 m/s and the fuel inlet of 0.01 m/s with various concentrations of oxygen: (a) O2= 0.5%, N2= 0.5%; (b) O2= 0.5%, N2= 0.2%, CO2= 0.1%, CO= 0.1%, and H2O= 0.1%; (c) O2= 0.7%, CO2= 0.1%, CO= 0.1%, and H2O= 0.1%; (d) O2= 0.8%, CO2= 0.1%, and H2O= 0.1%.

Table 1.

Boundary conditions of inlet fuel, inlet air, wall, and pressure.

Table 1.

Boundary conditions of inlet fuel, inlet air, wall, and pressure.

| Boundary conditions |

Parameters |

Values |

| Inlet air |

|

|

| Momentum |

Velocity (m/s) |

0.5 |

| |

Hydraulic diameter (m) |

0.03 |

| |

Turbulent intensity (%) |

10 |

| Thermal |

Temperature (K) |

300 |

| Species |

Oxygen (mass fraction) |

0.21 |

| Inlet fuel |

|

|

| Momentum |

Velocities (m/s) |

0.01, 0.03, 0.05, 0.075,

0.1, 0.3, 1, 5 and 10 |

| |

Hydraulic diameter (m) |

0.02 |

| |

Turbulent intensity (%) |

10 |

| Thermal |

Temperature (K) |

300 |

| Species |

Kerosene (mass fraction) |

1 |

| Walls |

Wall slip |

0 |

| |

Material |

Steel |

| |

Thermal condition |

Mixed |

| |

Heat transfer convection (W/m2.K) |

0 |

| Outlet pressure |

Gauge pressure |

0 |

| |

Hydraulic diameter (m) |

0.5 |

| |

Turbulent intensity (%) |

10 |

Table 2.

Setup of simulation.

Table 2.

Setup of simulation.

| Models |

Parameters |

| Viscous model |

K-e Standard |

| Radiation model |

P1 |

| Combustion model |

Diffusion combustion flame |

| Mixture properties |

Kerosene (C12H23)-air |

| Turbulence chemistry interaction |

Eddy dissipation model (EDM) |

| Reaction |

Volumetric |

| NOx |

Thermal and prompt NOx |