Submitted:

25 July 2025

Posted:

29 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

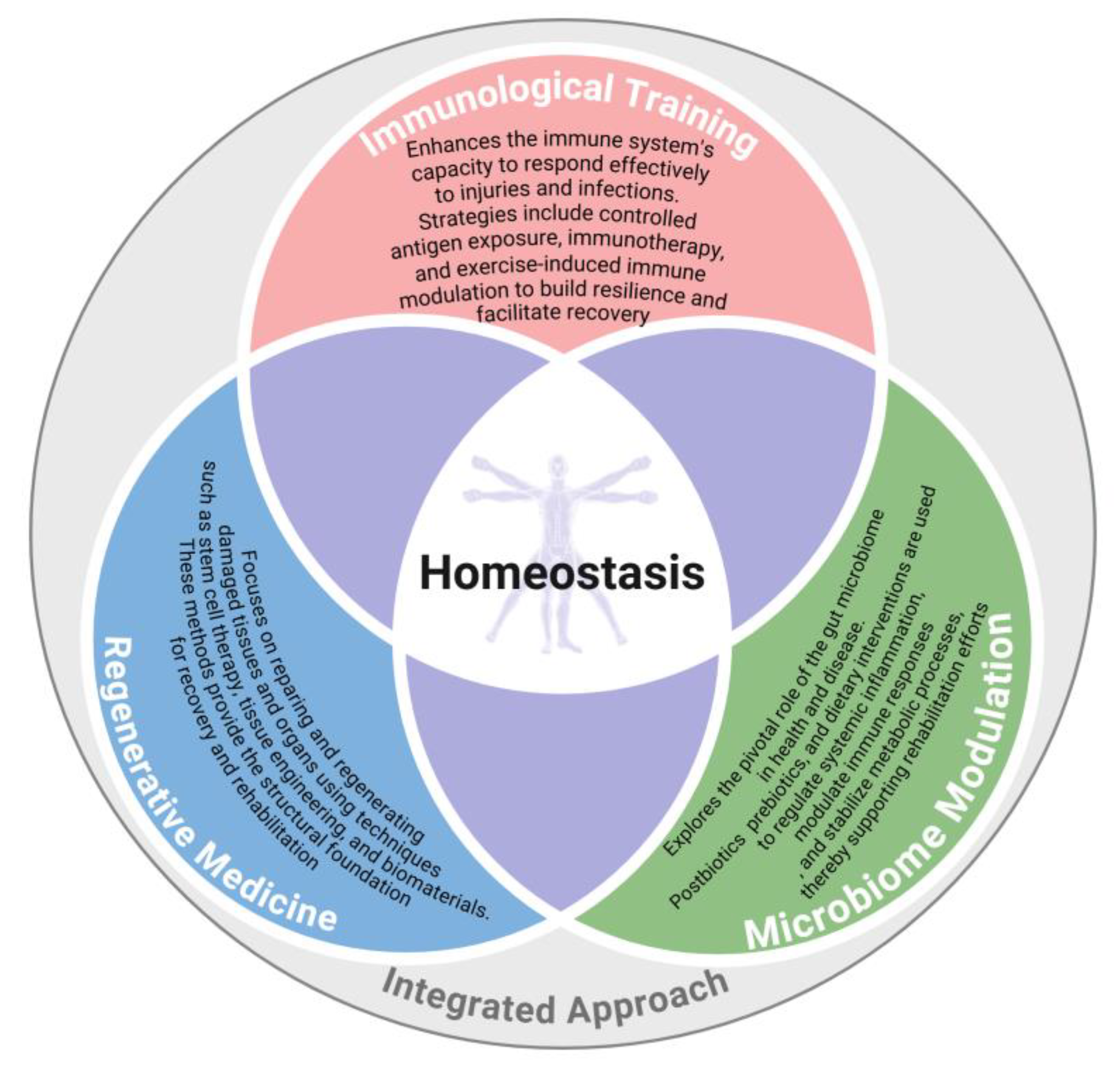

2. A Holistic Framework: From Individual Interventions to Systemic Synergy

- Regenerative Medicine: Building the Foundation

- Homeostatic Interventions: Stabilizing the System

- Immunological Training: Refining Biological Responses

- Microbiome Modulation: The Overlooked Partner

- Interconnected Mechanisms

3. The Role of the Immune System in Rehabilitation and Tissue Regeneration

4. Immunological Training: Refining Biological Responses

- The Immune System as a Driver of Healing

- Enhancing Angiogenesis Through Immune Modulation

- Preventing Chronic Inflammation: The Role of Resolution Mediators

- Adoptive Immune Cell Transfer and Beyond

- Applications in Chronic and Acute Conditions

- Future Directions in Immunological Training

5. Conceptual Link with Microbiome and Homeostasis

- Immune System Interaction: The microbiome interacts with the host's immune system, influencing inflammation and immune responses that are critical for regeneration. This interaction can either promote or inhibit regenerative processes depending on the balance of microbial communities.

- Microbiome and Immune Function

- Prebiotics, Probiotics, and Postbiotics: Restoring Microbial Balance

- Microbiome and Metabolic Homeostasis

- Microbiome Modulation: Indole-Based Postbiotics in Pulmonary Rehabilitation

- The Holistic Health Approach in Rehabilitation

6. Conclusions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| MSCs | mesenchymal stem cells |

| SCFAs | short-chain fatty acids |

| FMT | fecal microbiota transplantation |

| IL-1 | like interleukin-1 |

| TNF-α | tumor necrosis factor-alpha |

| VEGF | vascular endothelial growth factor |

| TGF-β | transforming growth factor-beta |

| Tregs | Regulatory T cells |

| M2 | macrophages |

| IL-10 | interleukin-10 |

| Trp | tryptophan |

| AhR | aryl hydrocarbon receptor |

| COPD | chronic obstructive pulmonary disease |

| FOS | fructo-oligosaccharides |

References

- Chua, K.S.G. and C.W.K. Kuah, Innovating With Rehabilitation Technology in the Real World: Promises, Potentials, and Perspectives. Am J Phys Med Rehabil, 2017. 96(10 Suppl 1): p. S150–s156.

- Kannenberg, A. , et al., Editorial: Advances in technology-assisted rehabilitation. Frontiers in Rehabilitation Sciences, 2024. 5.

- McClave, S.A. and R.G. Martindale, Why do current strategies for optimal nutritional therapy neglect the microbiome? Nutrition, 2019. 60: p. 100–105.

- Sinha, A. and S. Roy, Prospective therapeutic targets and recent advancements in the treatment of inflammatory bowel disease. Immunopharmacology and Immunotoxicology, 2024. 46(4): p. 550–563.

- Zhang, N. , et al., Harnessing immunomodulation to combat sarcopenia: current insights and possible approaches. Immunity & Ageing, 2024. 21(1): p. 55.

- Hammerhøj, A. , et al., Organoids as regenerative medicine for inflammatory bowel disease. iScience, 2024. 27(6).

- Cervenka, I., L. Z. Agudelo, and J.L. Ruas, Kynurenines: Tryptophan’s metabolites in exercise, inflammation, and mental health. Science, 2017. 357(6349): p. eaaf9794.

- Shavandi, A. , et al., The role of microbiota in tissue repair and regeneration. Journal of Tissue Engineering and Regenerative Medicine, 2020. 14(3): p. 539–555.

- Ogunrinola, G.A. , et al., The Human Microbiome and Its Impacts on Health. Int J Microbiol, 2020. 2020: p. 8045646.

- Afzaal, M. , et al., Human gut microbiota in health and disease: Unveiling the relationship. Frontiers in Microbiology, 2022. 13.

- Nunzi, E. , et al., Host-microbe serotonin metabolism. Trends Endocrinol Metab, 2025. 36(1): p. 83–95.

- Preethy, S. , et al., Integrating the Synergy of the Gut Microbiome into Regenerative Medicine: Relevance to Neurological Disorders. Journal of Alzheimer's Disease, 2022. 87: p. 1451–1460.

- Golchin, A. , et al., The Role of Probiotics In Tissue Engineering And Regenerative Medicine. Regenerative Medicine, 2023. 18(8): p. 635–657.

- Velikic, G. , et al., Harnessing the Stem Cell Niche in Regenerative Medicine: Innovative Avenue to Combat Neurodegenerative Diseases. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 2024. 25(2): p. 993.

- Mazziotta, C. , et al., Probiotics Mechanism of Action on Immune Cells and Beneficial Effects on Human Health. Cells, 2023. 12(1): p. 184.

- Ji, S. , et al., Cellular rejuvenation: molecular mechanisms and potential therapeutic interventions for diseases. Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy, 2023. 8(1): p. 116.

- Aurora, Arin B. and Eric N. Olson, Immune Modulation of Stem Cells and Regeneration. Cell Stem Cell, 2014. 15(1): p. 14–25.

- Belkaid, Y. and Timothy W. Hand, Role of the Microbiota in Immunity and Inflammation. Cell, 2014. 157(1): p. 121–141.

- Rooks, M.G. and W.S. Garrett, Gut microbiota, metabolites and host immunity. Nature Reviews Immunology, 2016. 16(6): p. 341–352.

- Berthiaume, F., T. J. Maguire, and M.L. Yarmush, Tissue engineering and regenerative medicine: history, progress, and challenges. Annu Rev Chem Biomol Eng, 2011. 2: p. 403–30.

- Hunsberger, J. , et al., Improving patient outcomes with regenerative medicine: How the Regenerative Medicine Manufacturing Society plans to move the needle forward in cell manufacturing, standards, 3D bioprinting, artificial intelligence-enabled automation, education, and training. STEM CELLS Translational Medicine, 2020. 9(7): p. 728–733.

- Saini, G. , et al., Applications of 3D Bioprinting in Tissue Engineering and Regenerative Medicine. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 2021. 10(21): p. 4966.

- de Jongh, D. , et al., Early-Phase Clinical Trials of Bio-Artificial Organ Technology: A Systematic Review of Ethical Issues. Transplant International, 2022. 35.

- Makuku, R. , et al., New frontiers of tendon augmentation technology in tissue engineering and regenerative medicine: a concise literature review. J Int Med Res, 2022. 50(8): p. 3000605221117212.

- Long, Y.C. and J.R. Zierath, AMP-activated protein kinase signaling in metabolic regulation. J Clin Invest, 2006. 116(7): p. 1776–83.

- Mauvais-Jarvis, F., D. J. Clegg, and A.L. Hevener, The Role of Estrogens in Control of Energy Balance and Glucose Homeostasis. Endocrine Reviews, 2013. 34(3): p. 309–338.

- Pillon, N.J. , et al., Metabolic consequences of obesity and type 2 diabetes: Balancing genes and environment for personalized care. Cell, 2021. 184(6): p. 1530–1544.

- Pataky, M.W., W. F. Young, and K.S. Nair. Hormonal and metabolic changes of aging and the influence of lifestyle modifications. in Mayo Clinic Proceedings. 2021. Elsevier.

- Tao, Z. and Z. Cheng, Hormonal regulation of metabolism—recent lessons learned from insulin and estrogen. Clinical Science, 2023. 137(6): p. 415–434.

- Netea, Mihai G., J. Quintin, and Jos W.M. van der Meer, Trained Immunity: A Memory for Innate Host Defense. Cell Host & Microbe, 2011. 9(5): p. 355–361.

- Bindu, S. , et al., Prophylactic and therapeutic insights into trained immunity: A renewed concept of innate immune memory. Human Vaccines & Immunotherapeutics, 2022. 18(1): p. 2040238.

- Terrén, I. , et al., Cytokine-Induced Memory-Like NK Cells: From the Basics to Clinical Applications. Front Immunol, 2022. 13: p. 884648.

- Li, F. , et al., Nanomedicine for T-Cell Mediated Immunotherapy. Advanced Materials, 2024. 36(22): p. 2301770.

- Zelante, T. , et al., Tryptophan catabolites from microbiota engage aryl hydrocarbon receptor and balance mucosal reactivity via interleukin-22. Immunity, 2013. 39(2): p. 372–85.

- Martyniak, A. , et al., Prebiotics, Probiotics, Synbiotics, Paraprobiotics and Postbiotic Compounds in IBD. Biomolecules, 2021. 11(12): p. 1903.

- Liu, Y., J. Wang, and C. Wu, Modulation of Gut Microbiota and Immune System by Probiotics, Pre-biotics, and Post-biotics. Frontiers in Nutrition, 2022. 8.

- de Sire, A. , et al., Role of dietary supplements and probiotics in modulating microbiota and bone health: the gut-bone axis. Cells, 2022. 11(4): p. 743.

- López-Otín, C. and G. Kroemer, Hallmarks of Health. Cell, 2021. 184(1): p. 33–63.

- Zelante, T. , et al., Regulation of host physiology and immunity by microbial indole-3-aldehyde. Curr Opin Immunol, 2021. 70: p. 27–32.

- Medzhitov, R. , Origin and physiological roles of inflammation. Nature, 2008. 454(7203): p. 428–435.

- Tonnesen, M.G., X. Feng, and R.A. Clark, Angiogenesis in wound healing. J Investig Dermatol Symp Proc, 2000. 5(1): p. 40–6.

- Wynn, T.A. and L. Barron, Macrophages: master regulators of inflammation and fibrosis. Semin Liver Dis, 2010. 30(3): p. 245–57.

- Serhan, C.N. , Pro-resolving lipid mediators are leads for resolution physiology. Nature, 2014. 510(7503): p. 92–101.

- Mantovani, A. , et al., Macrophage plasticity and polarization in tissue repair and remodelling. J Pathol, 2013. 229(2): p. 176–85.

- Nathan, C. and A. Ding, Nonresolving inflammation. Cell, 2010. 140(6): p. 871–82.

- Fang, Y. , et al., Granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor enhances wound healing in diabetes via upregulation of proinflammatory cytokines. British Journal of Dermatology, 2010. 162(3): p. 478–486.

- McInnes, I.B. and E.M. Gravallese, Immune-mediated inflammatory disease therapeutics: past, present and future. Nature Reviews Immunology, 2021. 21(10): p. 680–686.

- Song, Y., J. Li, and Y. Wu, Evolving understanding of autoimmune mechanisms and new therapeutic strategies of autoimmune disorders. Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy, 2024. 9(1): p. 263.

- Stratos, I. , et al., Inhibition of TNF-α Restores Muscle Force, Inhibits Inflammation, and Reduces Apoptosis of Traumatized Skeletal Muscles. Cells, 2022. 11(15).

- Livia, C. , et al., Infliximab Limits Injury in Myocardial Infarction. J Am Heart Assoc, 2024. 13(9): p. e032172.

- Carmeliet, P. and R.K. Jain, Molecular mechanisms and clinical applications of angiogenesis. Nature, 2011. 473(7347): p. 298–307.

- Chu, H. and Y. Wang, Therapeutic angiogenesis: controlled delivery of angiogenic factors. Ther Deliv, 2012. 3(6): p. 693–714.

- Shimamura, M. , et al., Progress of Gene Therapy in Cardiovascular Disease. Hypertension, 2020. 76(4): p. 1038–1044.

- Li, W. , et al., Macrophage regulation in vascularization upon regeneration and repair of tissue injury and engineered organ transplantation. Fundamental Research, 2024.

- Livshits, G. and A. Kalinkovich, Resolution of Chronic Inflammation, Restoration of Epigenetic Disturbances and Correction of Dysbiosis as an Adjunctive Approach to the Treatment of Atopic Dermatitis. Cells, 2024. 13(22).

- Clark, M. , et al., Attenuation of adipose tissue inflammation by pro-resolving lipid mediators. Curr Opin Endocr Metab Res, 2024. 36: p. 100539.

- Kattamuri, L. , et al., Safety and efficacy of CAR-T cell therapy in patients with autoimmune diseases: a systematic review. Rheumatol Int, 2025. 45(1): p. 18.

- Netea, M.G. , et al., Defining trained immunity and its role in health and disease. Nature Reviews Immunology, 2020. 20(6): p. 375–388.

- Vuscan, P. , et al., Trained immunity: General and emerging concepts. Immunological Reviews, 2024. 323(1): p. 164–185.

- Salauddin, M. , et al., Trained immunity: a revolutionary immunotherapeutic approach. Animal Diseases, 2024. 4(1): p. 31.

- Clemente-Suárez, V.J. , et al., New Insights and Potential Therapeutic Interventions in Metabolic Diseases. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 2023. 24(13): p. 10672.

- Chen, Y. and J.-Y. Fang, The role of colonic microbiota amino acid metabolism in gut health regulation. Cell Insight, 2025: p. 100227.

- Liu, H.X. , et al., Implications of microbiota and bile acid in liver injury and regeneration. J Hepatol, 2015. 63(6): p. 1502–10.

- Zheng, Z. and B. Wang, The gut-liver axis in health and disease: The role of gut microbiota-derived signals in liver injury and regeneration. Frontiers in immunology, 2021. 12: p. 775526.

- Yin, Y. , et al., Gut microbiota promote liver regeneration through hepatic membrane phospholipid biosynthesis. J Hepatol, 2023. 78(4): p. 820–835.

- Zheng, D., T. Liwinski, and E. Elinav, Interaction between microbiota and immunity in health and disease. Cell Research, 2020. 30(6): p. 492–506.

- Blander, J.M. , et al., Regulation of inflammation by microbiota interactions with the host. Nature Immunology, 2017. 18(8): p. 851–860.

- Williams, K.B. , et al., Regulation of axial and head patterning during planarian regeneration by a commensal bacterium. Mechanisms of Development, 2020. 163: p. 103614.

- Tung, A. and M. Levin, Extra-genomic instructive influences in morphogenesis: A review of external signals that regulate growth and form. Developmental biology, 2020. 461(1): p. 1–12.

- Tran, S. , et al., Microbial pattern recognition suppresses de novo organogenesis. Development, 2023. 150(9).

- Kobayashi, T., S. Naik, and K. Nagao, Choreographing Immunity in the Skin Epithelial Barrier. Immunity, 2019. 50(3): p. 552–565.

- Piipponen, M., D. Li, and N.X. Landén, The Immune Functions of Keratinocytes in Skin Wound Healing. Int J Mol Sci, 2020. 21(22).

- Wang, G. , et al., Bacteria induce skin regeneration via IL-1β signaling. Cell Host Microbe, 2021. 29(5): p. 777–791.e6.

- Uberoi, A. , et al., Commensal microbiota regulates skin barrier function and repair via signaling through the aryl hydrocarbon receptor. Cell Host Microbe, 2021. 29(8): p. 1235–1248.e8.

- Kim, C.H. , Complex regulatory effects of gut microbial short-chain fatty acids on immune tolerance and autoimmunity. Cell Mol Immunol, 2023. 20(4): p. 341–350.

- Virk, M.S. , et al., The Anti-Inflammatory and Curative Exponent of Probiotics: A Comprehensive and Authentic Ingredient for the Sustained Functioning of Major Human Organs. Nutrients, 2024. 16(4).

- Rau, S. , et al., Prebiotics and Probiotics for Gastrointestinal Disorders. Nutrients, 2024. 16(6): p. 778.

- Suez, J. and E. Elinav, The path towards microbiome-based metabolite treatment. Nat Microbiol, 2017. 2: p. 17075.

- Consortium, H.M.P. , Structure, function and diversity of the healthy human microbiome. Nature, 2012. 486(7402): p. 207–14.

- Agus, A., K. Clément, and H. Sokol, Gut microbiota-derived metabolites as central regulators in metabolic disorders. Gut, 2021. 70(6): p. 1174–1182.

- Takeuchi, T., Y. Nakanishi, and H. Ohno, Microbial Metabolites and Gut Immunology. Annu Rev Immunol, 2024. 42(1): p. 153–178.

- Du, Y. , et al., The Role of Short Chain Fatty Acids in Inflammation and Body Health. Int J Mol Sci, 2024. 25(13).

- Kumar, P., J. H. Lee, and J. Lee, Diverse roles of microbial indole compounds in eukaryotic systems. Biol Rev Camb Philos Soc, 2021. 96(6): p. 2522–2545.

- Roager, H.M. and T.R. Licht, Microbial tryptophan catabolites in health and disease. Nat Commun, 2018. 9(1): p. 3294.

- Agus, A., J. Planchais, and H. Sokol, Gut Microbiota Regulation of Tryptophan Metabolism in Health and Disease. Cell Host Microbe, 2018. 23(6): p. 716–724.

- Hubbard, T.D. , et al., Adaptation of the human aryl hydrocarbon receptor to sense microbiota-derived indoles. Sci Rep, 2015. 5: p. 12689.

- Li, S. , Modulation of immunity by tryptophan microbial metabolites. Front Nutr, 2023. 10: p. 1209613.

- Mafe, A.N. , et al., Probiotics and Food Bioactives: Unraveling Their Impact on Gut Microbiome, Inflammation, and Metabolic Health. Probiotics and Antimicrobial Proteins, 2025.

- Ma, T. , et al., Targeting gut microbiota and metabolism as the major probiotic mechanism - An evidence-based review. Trends in Food Science & Technology, 2023. 138: p. 178–198.

- Du, T. , et al., The Beneficial Role of Probiotic Lactobacillus in Respiratory Diseases. Frontiers in Immunology, 2022. 13.

- Shen, H.-T. , et al., A Lactobacillus Combination Ameliorates Lung Inflammation in an Elastase/LPS—induced Mouse Model of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. Probiotics and Antimicrobial Proteins, 2024.

- Melo-Dias, S. , et al., Responsiveness to pulmonary rehabilitation in COPD is associated with changes in microbiota. Respir Res, 2023. 24(1): p. 29.

- Puccetti, M. , et al., Turning Microbial AhR Agonists into Therapeutic Agents via Drug Delivery Systems. Pharmaceutics, 2023. 15(2).

- Hijová, E. , Postbiotics as Metabolites and Their Biotherapeutic Potential. Int J Mol Sci, 2024. 25(10).

- Ye, X. , et al., Dual Role of Indoles Derived From Intestinal Microbiota on Human Health. Front Immunol, 2022. 13: p. 903526.

- Hoseinzadeh, A. , et al., A new generation of mesenchymal stromal/stem cells differentially trained by immunoregulatory probiotics in a lupus microenvironment. Stem Cell Res Ther, 2023. 14(1): p. 358.

- Wang, Y., T. Gao, and B. Wang, Application of mesenchymal stem cells for anti-senescence and clinical challenges. Stem Cell Research & Therapy, 2023. 14(1): p. 260.

- Kim, Y.C., K. H. Sohn, and H.R. Kang, Gut microbiota dysbiosis and its impact on asthma and other lung diseases: potential therapeutic approaches. Korean J Intern Med, 2024. 39(5): p. 746–758.

- Chotirmall, S.H. , et al., Therapeutic Targeting of the Respiratory Microbiome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med, 2022. 206(5): p. 535–544.

- Druszczynska, M. , et al., The Intriguing Connection Between the Gut and Lung Microbiomes. Pathogens, 2024. 13(11): p. 1005.

| Technique | Description | Clinical Applications | Outcomes |

| Stem Cell Therapy | Utilization of stem cells to regenerate or repair damaged tissues. | Musculoskeletal injuries, neurodegenerative disorders, cardiac repair. | Promotes tissue repair, reduces inflammation, enhances functional recovery. |

| Tissue Engineering | Development of bioengineered tissues using scaffolds, cells, and growth factors. | Skin grafts, organ reconstruction, cartilage repair. | Enables anatomical restoration, improves structural integrity, and accelerates healing. |

| 3D Bioprinting | Layer-by-layer printing of biomaterials to create complex tissue structures. | Bone repair, vascular grafts, organ models for testing. | Offers precise structural replication and reduces reliance on donor tissues. |

| Gene Therapy | Introduction of genetic material to correct or modify cellular dysfunctions. | Genetic disorders, cancer, immunodeficiencies. | Corrects genetic mutations, enhances targeted therapies, and improves cellular functionality. |

| Immunomodulatory Agents | Use of agents to regulate immune responses and promote healing. | Autoimmune diseases, chronic inflammation, transplant medicine. | Balances immune responses, prevents complications, and supports tissue regeneration. |

| Component | Role | Mechanisms | Benefits |

| Probiotics | Live beneficial bacteria administered to restore microbial balance. | Compete with pathogens, produce bioactive compounds, and enhance immune cell activity. | Supports immune modulation, improves digestion, and accelerates recovery. |

| Prebiotics | Nutritional compounds that promote the growth of beneficial bacteria. | Fermented by gut microbiota to produce bioactive metabolites. | Enhances gut microbiota diversity, supports nutrient absorption, and stabilizes homeostasis. |

| Postbiotics | Bioactive compounds produced by probiotics, such as SCFAs, indole derivatives or peptides. | Directly influence host physiology through anti-inflammatory and antioxidant effects and promoting gut barrier integrity. | Reduces oxidative stress, systemic inflammation, promotes tissue healing and systemic homeostasis. |

| Step | Description | Actions | Expected Benefits |

| 1. Baseline Assessment | Evaluate the patient’s microbiome profile and overall health status. | Conduct gut microbiota analysis, assess dietary habits, and identify dysbiosis or imbalances. | Personalized insights into microbiome health and targeted intervention planning. |

| 2. Targeted Nutritional Plan | Design a dietary strategy to support microbial diversity and SCFA production. | Incorporate prebiotics (e.g., inulin, fructo-oligosaccharides; FOS) and fiber-rich foods into the patient’s diet. | Enhances gut microbiota diversity, supports metabolic homeostasis, and improves recovery. |

| 3. Probiotic Supplementation | Introduce beneficial live bacteria tailored to individual needs. | Prescribe specific probiotic strains based on identified deficiencies (e.g., Lactobacillus, Bifidobacterium). | Restores microbial balance, reduces inflammation, and boosts immune resilience. |

| 4. Postbiotic Integration | Incorporate bioactive metabolites produced by beneficial bacteria into the therapy plan. | Use SCFA supplements or postbiotic formulations to enhance systemic and localized recovery. | Strengthens gut barrier integrity, modulates immunity, and accelerates tissue healing. |

| 5. Monitor and Adjust | Regularly assess microbiome-related health outcomes to refine the rehabilitation plan. | Perform follow-up microbiota analyses and adapt dietary or supplementation strategies. | Ensures sustained microbiome health and optimizes long-term rehabilitation outcomes. |

| 6. Gut-Health Education | Empower patients with knowledge about maintaining a healthy microbiome. | Provide guidance on diet, lifestyle, and probiotic use to prevent dysbiosis. | Promotes long-term health resilience and prevents recurrence of imbalances. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).