1. Introduction

Logging is considered to be a dangerous profession due to its specific nature. One of unfavorable factors is working outdoors, when the logger is exposed to a variety of weather conditions, depending on the season and prevailing temperatures: weather conditions can complicate the performance of professional duties, for example, in rain, strong wind, extremely low temperatures in winter and high temperatures in summer [

1]. Noise and vibration are also among the production factors of loggers, which can slow down and complicate mental processes, reducing concentration, which contributes to inaccurate performance of actions [

1,

2,

3]. The introduction of harvester logging has improved safety and reduced the accident rate, but has also led to a risk of musculoskeletal disorders and increased psychological stress [

4], as well as increased concentration and attention of operators over a long period of time [

5]. The factors that make harvesters’ work difficult include heavy lifting, prolonged awkward postures in the lower back, repetitive movements and prolonged periods of time in the same work breaks, which have a negative impact on the musculoskeletal system [

6,

7]. The logging process is complicated by the following professional environment factors: weather conditions, swampy terrain, great remoteness of forest plots (which requires more time for daily delivery of workers to the workplace), insufficient productivity and equipment breakdowns, lack of personnel, etc. [

6,

8]. Long working hours (more than 12) and work requirements increase the likelihood of fatigue and stress in loggers [

9]. Literature data show that working conditions and professional workloads have a negative impact on the functional state of loggers: there is an increase in stress, anxiety, as well as tension in different parts of the body (back, neck, etc.) [

8,

10,

11]. The main occupational groups in logging enterprises are logging equipment operators (harvesters and forwarders) and truck drivers (for timber removal and dump truck drivers) [

8]. The main factors affecting the work of truck drivers are long periods of intense concentration, as well as quick reactions, severe stress and high long-term muscle load [

8,

12]. This leads to adverse effects on the health and psyche of workers and indirectly affects their work productivity [

13,

14]. Logging equipment operators have to work in uncomfortable positions, which leads to overexertion. The main problems of forest machine operators range from the difficulty of maneuvering machines on uneven terrain to variable soil conditions, which affects their productivity [

15]. Increased mental workload is not only associated with discomfort, but can also affect workers’ health and safety: operators with severe fatigue are more likely to make mistakes, and this can lead to injuries or damage [

16].

Loggers carry out their professional activities in conditions of group isolation in small teams (up to 30 people) during a fifteen-day shift period of daily 12-hour work, followed by a rest period of the same duration. Successful performance of professional activities in shift work largely depends on maintaining group cohesion [

17]. Teams need to coordinate their actions, communicate, and collaborate, relying on each other to successfully cope with external challenges [

18]. O. Brown (2019) monitored changes in expedition team cohesion over time [

19]. Isolation, coupled with intense physical exertion, makes it difficult to create and maintain effective teamwork, increases the likelihood of social conflicts, and emphasizes individual differences [

20,

21]. Expeditionary conditions are also characterized by monotonous daily tasks [

22], which increases the risk of conflicts because loggers have to cope with boredom. The paper also provides data from other studies. In a 12-person group that completed a 61-day trek across Alaska, a positive relationship was found between cohesion and communication, perceived fairness in task distribution, and perceived quality of group leader decisions [

22].

A previous study found that there is a discrepancy in the indicators of psychological and psychophysiological parameters of the functional states of loggers during a 15-day shift period [

23]. According to psychophysiological parameters, throughout the entire shift period, employees experienced stress levels above the norm, with the highest risk occurring during the first four days of the shift, as well as the mid-shift changeover period (transition from night to day shift and vice versa) and the end of the shift period, during which a reduced level of performance and an acceptable condition level were observed [

23]. At the same time, according to psychological parameters, positive dynamics of employees’ performance and well-being were established [

23]. The established differences require clarification of the relationships between the psychophysiological and psychological variables describing the functional states of logging company workers at the beginning, middle and end of the shift period. Our previous studies have shown differences in the dynamics of performance and stress, measured using biochemical, psychophysiological and psychological methods, in shift workers of oil and gas production enterprises in the Arctic [

24] and logging workers in the Far North [

23]. These data are also confirmed by a number of studies which established differences in the physiological and perceived levels of stress in shift workers [

25,

26,

27,

28]. The established differences require clarification of how the various parameters of the functional states of workers at a logging enterprise are related at the beginning, middle and end of the shift period. Our present study is relevant because for the first time, the assessment of states was carried out in the summer period, when studying the relationships; data from daily double measurements of the states of workers were taken into account, using new, previously not used on similar samples, psychological testing methods for assessing functional states.

The study aim is identification and description of the relationships between the severity of psychological and psychophysiological parameters of job stress and the working capacity of loggers of various divisions with various socio-psychological characteristics of teams in the north at the beginning, middle and end of the shift period.

Research objectives:

1. To carry out the comparative analysis of socio-psychological characteristics of teams of two logging divisions.

2. To identify and describe the features of professional stress and performance of workers of a logging enterprise of various divisions in the North at the beginning, middle and end of the shift period.

3. To establish and describe the relationship between psychophysiological and psychological parameters of professional stress and performance of logging workers in the North at the beginning, middle and end of the shift period.

Hypotheses:

Main hypothesis: due to a much more stressful character of the adaptation and final stages of shift work, greater consistency of various assessments of professional stress and performance of loggers is expected compared to the more favorable period of the middle of the shift. These differences may indicate intersystemic consolidation of various adaptation methods in more severe conditions and their measured, distributed use in relatively favorable periods.

Special hypothesis: dynamic shifts in the functional states of loggers during the shift period are positively associated with positive socio-psychological characteristics of the logging team.

2. Materials and Methods

The study is longitudinal.

2.1. Procedure

The study was conducted during two scientific expeditions to two separate divisions of a logging enterprise at forest plots (Karpogory village (geographical coordinates 64°00′02″ N, 44°26′42″ E) and Yasny settlement (64°02′08″ N, 44°04′46″ E), Arkhangelsk region of the Russian Federation) simultaneously from July 16 to July 31, 2024 during the entire fifteen-day shift period with daily double measurements (morning and evening) of occupational stress parameters. All the participants took part in the study on a voluntary basis after signing a written voluntary informed consent. All surveyed workers live in the Arkhangelsk region. Work and rest schedule: 12 hours \ 12 hours during the entire shift period without days off.

Due to the fact that both plots are located next to each other, have similar climatic conditions and belong to the same organization, we believe the differences between them can be observed in the socio-psychological characteristics of the teams, which in conditions of group isolation with the shift work method can affect the professional stress and performance of workers. In this regard, these characteristics were assessed and taken into account in the study.

Testing the hypothesis about the relationship between various parameters of professional stress and the performance of employees at various stages of the shift was carried out on a common sample in order to identify general patterns.

2.2. Sample

The study involved 47 loggers aged 26 to 60 years. The sample is representative of the general population of loggers in the Arkhangelsk region of the Russian Federation due to the correspondence of the demographic indicators of the sample to the demographic indicators of the enterprise as a whole and the presence of respondents of different ages, education, experience, positions and structural separate divisions (

Table 1).

All the loggers in the sample live in the Arkhangelsk region, get to the gathering place (v. Karpogory, s. Yasny) by car or rail, from the gathering place to the shift camp they are delivered by bus along a 100 km forest road. In the shift camp, workers live in cabins designed for 4 people, equipped with sleeping places, places for eating and resting, and stove heating. On the territory of the shift camp there is a canteen and a bathhouse.

2.3. Methods

The functional states of loggers were assessed throughout the entire shift period using the following methods:

1) psychophysiological hardware techniques:

the technique of assessing the complex visual-motor reaction ("CVMR") on the UPFT-1/30- "Psychophysiologist" device [

29], which includes 75 red and green signals that randomly appear and suggest the answer "yes" (when a green signal appears) or "no" (when a red signal appears). The speed and correctness of the answers are noted, and the levels of operator performance and sensorimotor reactions are calculated on their basis.

‒ the technique of variational cardiointervalometry ("VCM") on the UPFT-1/30- "Psychophysiologist" device [

29], which allows determining the level of one’s functional state by analyzing 128 cardiocycles (ECG signal, the time of RR intervals and their standard deviation are recorded).

‒ methods for assessing the characteristics of the cardiovascular system using the AngioCode mobile health tracker (ZMT LLC, Izhevsk, Russia) [

30]. This device is included in the program for assessing the functional state of workers due to its active use at various enterprises by psychological services and labor protection services of industrial enterprises.

‒ assessment of arterial pressure and heart rate (HR) using a tonometer with subsequent calculation of the coefficients [

31], presented in

Figure 1.

Endurance coefficient (EC) according to the formula of A. Kvaas: EC = HR*10 / (SBP – DBP).

HR – pulse, SBP – systolic blood pressure, DBP – diastolic blood pressure. An increase in this indicator indicates a weakening, and a decrease indicates an increase in the functional capabilities of the cardiovascular system. The norm is from 12 to 15.

Adaptation potential (AP) or the index of the circulatory system functional state: AP = 0.011 * HR + 0.014 * SBP + 0.008 * DBP + 0.014 * B + 0.009 * BM - 0.009 * P - 0.27,

where HR is pulse in beats per minute, SBP is systolic blood pressure in mm Hg, DBP is diastolic blood pressure in mm Hg,

B is age in years, P is height in cm, BM is body weight in kg.

Adaptation state assessment: Satisfactory state AP < 2.1; Tense adaptation AP 2.1 - 3.3; Unsatisfactory adaptation AP 3.31 - 4.3; Adaptation failure AP > 4.3.

E.A. Pirogova’s physical condition index (PCI):

where HR is pulse in beats/min, SBP is systolic blood pressure in mmHg, DBP is diastolic blood pressure in mmHg,

Age in years, His height in cm, BM is body weight in kg.

The following PCI standards can be used as gradations: Low -- less than 0.375; Below average -- from 0.375 to 0.525; Average -- from 0.526 to 0.675; Above average -- from 0.676 to 0.825; High -- from 0.826 and more.

2) psychological methods:

‒ "State Scale" by E. Grol, M. Heider, adapted by A. B. Leonova. The test consists of 40 questions; the answers of the subjects are assessed using four-point scales (where 1 is "almost never", and 4 is "almost always"), identifying four levels of severity of symptoms of the following mental states: monotony, mental satiety, tension/stress, fatigue [

32,

33,

34].

‒ the brief eight-color test of M. Luscher [

35], using the interpretation coefficients developed by G.A. Aminev [

36]; All coefficients were calculated using the corresponding formulas reflecting a particular combination of colors. A more detailed description of each parameter and its calculation based on the colors choice by the respondent is presented in our previous work [

24]. M. Luscher assessed high performance using green, red and yellow colors, which stand next to each other at the beginning of the row. This parameter is reflected in Aminev’s performance coefficient, varying from 9.1 to 20.9. According to M. Luscher’s theory, stress indicators are the presence of primary active colors in the last positions of the subjects’ choice and the presence of brown, black and gray cards in the first places of the row. The parameter varies from 0 to 41.8. The vegetative balance is calculated by correlating the red and yellow colors with blue and green at the beginning or end of the row and reflects the relationship between the sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous system, that is, between the activating and inhibitory processes in the body. The personal balance is calculated based on the ratio of violet and brown with green and blue at the beginning and end of the row and reflects the relationship between internal (subjective) and external (objective) factors in human behavior. It shows how much a person is focused on their own experiences or on external circumstances. Heteronomy shows how much a person is influenced by the external environment, social norms or other people’s opinions. Aminev’s interpretation coefficients have been repeatedly used in empirical studies and correlate well with other parameters of human functional states [

8,

24].

‒ the method of differentiated assessment of states of reduced performance (DASRWC) by A.B. Leonova, S.B. Velichkovskaya. The method is an adaptation of the BMSII test by H. Plath and R. Richter [

37,

38].

‒ Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Scale (DASS-21) by S. Lovibond and P. Lovibond, adapted by A.A. Zolotareva [

39,

41,

42].

Figure 1 shows the methods used to assess functional states and the parameters measured by them. Diagnostics of the functional states of loggers was carried out daily in the morning and evening using the VCM, CVMR, AngioCode, tonometer, state scale, M. Luscher test and DASS21. The DASRWC method was used every three days due to the content of the questionnaire.

Figure 1.

Methods for diagnosing functional states of loggers and parameters evaluated by them.

Figure 1.

Methods for diagnosing functional states of loggers and parameters evaluated by them.

To describe the socio-psychological characteristics of the two units, the following methods were used five times during the shift period (every three days), and the socio-psychological climate method was used once on the 4th day of the shift:

1) S.E. Seashore’s group cohesion [

43,

44]. Group cohesion was understood as an integral indicator reflecting the degree of emotional attractiveness of the group for its members, the strength of the participants’ desire to maintain membership in the team and the level of unity in achieving common goals. This method allows us to assess the degree of integration of the group, its cohesion into a single whole. It consists of 5 questions, each of which has from 4 to 6 answer options. The final indicator can range from 5 (very unfavorable assessment) to 19 points (very high assessment).

2) F.E. Fiedler’s psychological atmosphere, adapted by Yu. L. Khanin [

45,

46,

47]. The psychological atmosphere in a team was understood as a dynamic emotional-evaluative characteristic of interpersonal relations in a group, reflecting the subjective perception of comfort, trust and general emotional background of interaction by participants. It is based on the semantic differential method. Employees give an assessment of the group according to the proposed bipolar scales according to 10 dichotomies. The final indicator fluctuates from 10 (the most positive assessment) to 80 (the most negative). The lower the coefficient, the more favorable the assessment of the psychological atmosphere in the team.

3) V. A. Rozanova’s group motivation [

48]. Group motivation is an integral indicator reflecting the degree of team members’ involvement, interest and focus on achieving common goals. It is compiled according to the semantic differential type and contains 25 statements with a rating scale from 1 to 7 points. The results are assessed based on the sum of points indicated on the questionnaire form: 25–48 points — the group is negatively motivated; 49–74 points — the group is weakly motivated; 75–125 points — the group is insufficiently motivated to achieve results; 126–151 points — the group is sufficiently motivated to succeed in its activities; 152–175 points — the group is positively motivated to succeed in its activities.

4) Socio-psychological climate by O.S. Mikhalyuk and A.Yu. Shalyto [

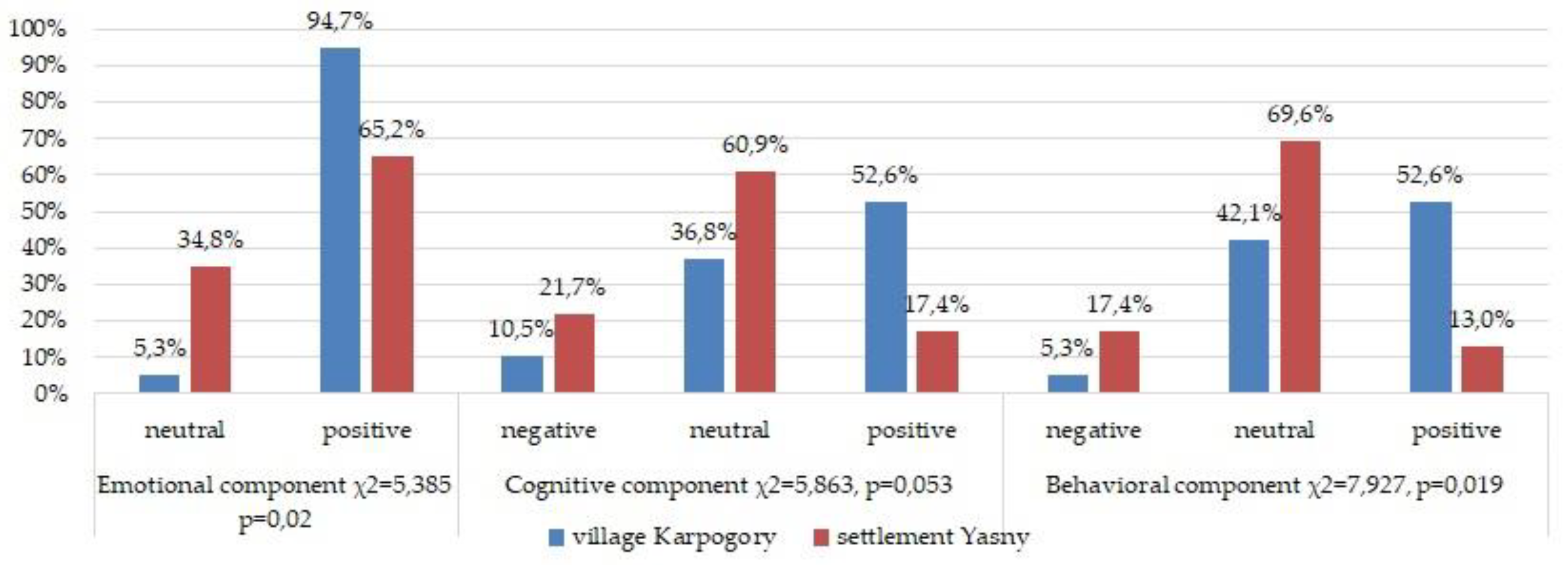

49]. Socio-psychological climate is a qualitative aspect of interpersonal relations in a group, manifested as a set of psychological conditions that contribute to or hinder productive joint activities and comprehensive development of the individual. The diagnostics of the socio-psychological climate is carried out according to three main parameters: the emotional component (satisfaction with relationships); the cognitive component (assessment of the business qualities of colleagues); the behavioral component (readiness for joint activities).

2.4. Data Analysis

The statistical processing of the results was carried out using descriptive statistics, Student’s T-test, Mann-Whitney’s U test and correlation analysis using Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient with the help of the IBM SPSS Statistics 26.00 package. The permissible level of the first type of error took into account the multiplicity of hypotheses being tested.

When conducting the correlation analysis, only those factors were taken into account that had statistically significant relationships at a level of p less than 0.04 with the parameters of the functional states of workers (group assessment of the probability of error (I type) using the Bonferroni method modified by Holm).

For the purpose of the study, all professional stress measurements were divided into three groups depending on the stage of the shift period: 1) days 1-3 - the beginning of the shift period (a total of 63 and 98 measurements on the first and second plots, respectively); 2) days 6-8 - the middle of the shift period (79 and 115 measurements); 3) Days 11-13 – the end of the shift period (61 and 103 measurements). Using Student’s T-test (under the assumptions of normal distributions and homogeneity of variances) and the Mann-Whitney U test (if it is necessary to use a non-parametric test), statistically significant differences in the socio-psychological characteristics of the teams (

Table 2), psychophysiological and psychological parameters of the functional states of loggers in the two divisions (

Table 3 and

Table 4) were established.

3. Results

3.1. Social-Psychological Characteristics of Teams of Two Divisions at the Beginning, Middle and End of the Shift Period

Table 2 shows descriptive statistics and the level of significance of differences in the socio-psychological characteristics of the teams of the two divisions at different stages of the shift period.

Table 2.

Socio-psychological characteristics of the teams of the two divisions.

Table 2.

Socio-psychological characteristics of the teams of the two divisions.

Parameter, methodology

|

Beginning of shift period |

Middle of shift period |

End of shift period |

| К |

Ya |

p |

К |

Ya |

p |

К |

Ya |

p |

| Group motivation, V.A. Rozanova |

142.8; 22.00 |

126.5; 21.86 |

0.057 |

139.3; 22.49 |

124.2; 18.89 |

0.047 |

135.3; 26.37 |

124.7; 17.98 |

0.204 |

| Group cohesion, K.E. Seashore |

14.9; 1.78 |

13.9; 2.45 |

0.026 |

14.3; 1.96 |

14.16; 2.39 |

0.947 |

15.0; 1.80 |

14.0; 1.86 |

0.001 |

| Psychological atmosphere, F. Fiedler |

17.7; 10.98 |

25.3; 10.38 |

0.001 |

17.9; 7.03 |

24.5; 9.7 |

0.001 |

19.4; 5.62 |

27.2; 7.91 |

0.001 |

According to

Table 2, statistically significant differences between the subdivisions were established in group motivation in the middle of the shift trip, which was higher among the employees of the plot in the village of Karpogory than in Yasny settlement. At the same time, both subdivisions were sufficiently motivated to work together. Group cohesion differed among the teams of the two subdivisions at the beginning and at the end of the shift period, and was also higher in the subdivision in the village of Karpogory than in Yasny settlement. The psychological atmosphere in the teams differed at all stages of the shift trip and was also higher in the subdivision in the village of Karpogory than in Yasny settlement (the lower the indicator, the more favorable the psychological atmosphere). Using Pearson’s

χ2 for contingency tables, statistically significant differences were established in the distribution of employees of the two subdivisions with respect to the emotional and behavioral components of the socio-psychological climate (

Figure 2). In the Karpogory subdivision more than 94.7% of employees had a positive emotional attitude towards the team and 52.6% expressed a positive attitude and readiness for joint activities, while in Yasny settlement - only 65.2% experienced positive emotions towards the team and 13% were ready to work in such a group.

Thus, based on the analysis of data on group motivation, cohesion and socio-psychological climate in teams, we can conclude that the division of the village of Karpogory is a team with positive socio-psychological characteristics, while the Yasny team has moderate socio-psychological characteristics.

3.2. Peculiarities of Professional Stress in Loggers of Two Divisions at the Beginning, Middle and End of the Shift Period

Table 3 and

Table 4 provide descriptive statistics for those professional stress parameters for which statistically significant differences were established at different stages of the shift period at the beginning, middle and end of the shift.

According to the data in

Table 3 and

Table 4, statistically significant differences were established in the parameters of the functional states of loggers of the two divisions, measured using the DASRWC, DASS-21, CVMR, VCM methods, as well as using the AngioCode device and the coefficients based on arterial pressure.

Table 3.

Psychophysiological parameters of professional stress and performance of loggers of the two divisions at the beginning, middle and end of the shift period.

Table 3.

Psychophysiological parameters of professional stress and performance of loggers of the two divisions at the beginning, middle and end of the shift period.

Condition parameter, methodology

|

Beginning of shift period (M; SD) |

Middle of shift period (M; SD) |

End of shift period (M; SD) |

К

N=63 |

Ya

N=98 |

p |

К

N=79 |

Ya

N=115 |

p |

К

N=61 |

Ya

N=103 |

p |

| Stress level* |

175.9; 269.19 |

180.9; 147.74 |

0.05 |

200.7; 238.01 |

165.2; 194.79 |

0.011 |

159.5; 200.24 |

111.2; 126.27 |

0.016 |

| Systolic pressure** |

131.9; 17.00 |

137;1 7.56 |

- |

127.6; 13.97 |

136.1; 17.71 |

0.001 |

127.4; 14.07 |

129.7; 15.97 |

- |

| Quasa endurance coefficient** |

16.2; 4.51 |

14.5; 3.97 |

0.018 |

17.0; 4.52 |

14.9; 4.53 |

0.001 |

17.1; 4.61 |

15.3; 4.61 |

0.008 |

| Adaptive potential** |

2.8; 0.46 |

3.1; 0.35 |

0.001 |

2.7; 0.41 |

3.1; 0.36 |

0.001 |

2.7; 0.43 |

3.0; 0.37 |

0.001 |

| Physical condition index** |

0.5; 0.20 |

0.6; 0.14 |

0.001 |

0.5; 0.18 |

0.6; 0.15 |

0.001 |

0.5; 0.21 |

0.7; 0.17 |

0.001 |

| Speed*** |

4.3; 1.09 |

3.3; 0.98 |

0.001 |

4.4; 1.08 |

3.3; 1.09 |

- |

4.6; 0.99 |

3.5; 0.97 |

0.001 |

| Operator performance*** |

3.3; 1.44 |

2.5; 0.95 |

0.001 |

3.5; 1.65 |

2.8; 0.89 |

0.003 |

3.8; 1.63 |

2.8; 0.88 |

0.001 |

| Functional capacity level **** |

5.2; 1.7 |

3.7; 1.3 |

0.001 |

5.5; 1.5 |

3.5; 1.26 |

0.001 |

5.0; 1.75 |

3.7; 1.46 |

0.001 |

| Functional condition level **** |

3.2; 1.33 |

4.2; 1.22 |

0.001 |

3.4; 1.23 |

4.0; 1.19 |

0.003 |

3.4; 1.07 |

4.3; 1.49 |

0.001 |

According to

Table 3, the stress level (according to the Angiocode device) is lower among the Karpogory employees at the beginning of the shift, and higher in the middle and at the end of the shift, in comparison with the Yasny team (while their values are below average). Systolic pressure was higher among the Yasny loggers at all stages of the shift. The endurance coefficient (according to Kvaas) corresponded to the norm among the members of Yasny settlement during the entire shift period, and among the Karpogory employees it was slightly higher, which indicates a weakening of the functional capabilities of the cardiovascular system. The adaptive potential was reduced among the employees of both divisions during the shift period, while Yasny was characterized with more intense adaptation. The physical condition indices of the Karpogory loggers were below average during the entire shift period, and in Yasny settlement they were average. However, at the end of the shift period they were above average. The Karpogory workers demonstrated above-average speed in performing a complex visual-motor reaction and were characterized by above-average operator performance throughout the entire shift period, while the representatives of Yasny settlement performed the complex visual-motor reaction more slowly and their operator performance was below average. The level of functional capabilities of the Karpogory loggers was high, and their functional state was acceptable throughout the entire shift period. At the same time, the Yasny loggers had an average level of functional reserves of the cardiovascular system and a more favorable functional state level.

Thus, according to the psychophysiological parameters measured using a tonometer and the coefficients calculated on its basis, the Karpogory loggers had less favorable conditions, characterized by weakened endurance and an average index of physical condition; however, according to other methods (CVMR, VCM, AngioCode) -- more positive indicators: above average speed of visual-motor reactions, average operator performance, above average level of functional capabilities and low stress level. The Yasny employees, on the contrary, had a higher endurance (average level), an average level of physical condition, but they felt tense adaptation more acutely, their speed and operator performance were below average, and their level of functional capabilities of the cardiovascular system was average.

Table 4.

Psychological parameters of job stress, work capacity and labor productivity of loggers of two divisions at the beginning, middle and end of the shift period.

Table 4.

Psychological parameters of job stress, work capacity and labor productivity of loggers of two divisions at the beginning, middle and end of the shift period.

Condition parameter, methodology

|

Beginning of shift period (M; SD) |

Middle of shift period (M; SD) |

End of shift period (M; SD) |

К

N=63 |

Ya

N=98 |

p |

К

N=63 |

Ya

N=98 |

p |

К

N=63 |

Ya

N=98 |

p |

| Psychological parameters of stress and working capacity |

| Vegetative balance* |

4.8; 4.32 |

5.8; 3.75 |

- |

3.8; 5.12 |

5.3; 3.87 |

- |

2.9; 5.28 |

6.1; 3.22 |

0.001 |

| Subjective comfort** |

53.8; 8.88 |

52.8; 8.55 |

- |

54.7; 8.68 |

53.4; 9.7 |

- |

55.7; 9.02 |

51.8; 9.95 |

0.03 |

| Fatigue*** |

16.9; 3.86 |

15.3; 2.62 |

0.004 |

17; 3.67 |

15.6; 3.5 |

0.005 |

17.2; 3.71 |

16.6; 3.71 |

- |

| Monotony*** |

17.9; 2.35 |

17.1; 2.38 |

0.046 |

18.3; 2.76 |

18.1; 2.53 |

- |

18.1; 2.89 |

18.7; 2.48 |

- |

| Satiety*** |

18.9; 4.2 |

17; 3.38 |

0.004 |

18.2; 4.36 |

17.8; 3.52 |

- |

19.8; 4.85 |

18.3; 4.64 |

- |

| Stress*** |

17.8; 3.6 |

18.6; 3.42 |

- |

17.5; 3.07 |

18; 2.73 |

- |

17.7; 3.24 |

19.7; 2.42 |

0.001 |

| Depression**** |

1.1; 1.69 |

2.4; 2.18 |

0.001 |

0.3; 0.79 |

2.3; 2.29 |

0.001 |

0.2; 0.52 |

2.4; 2.71 |

0.001 |

| Anxiety**** |

1.7; 3.07 |

1.8; 1.82 |

0.05 |

0.4; 1.04 |

1.7; 1.67 |

0.001 |

0.2; 0.64 |

1.9; 1.7 |

0.001 |

| Stress**** |

2.1; 3.11 |

3.9; 2.66 |

0.001 |

1.2; 1.81 |

3.8; 2.97 |

0.001 |

0.6; 1.59 |

4.2; 3.18 |

0.001 |

| Labor productivity |

| Volume of timber per shift |

144.2; 52.92 |

144.9; 38.75 |

- |

97.7; 52.23 |

174.9; 48.87 |

0.001 |

145.5; 37.4 |

195.7; 60 |

0.003 |

The employees of the Karpogory subdivision were characterized by moderate fatigue, satiety, and monotony, which were higher than those of the representatives of the other subdivision. The stress level measured by DASRWC and DASS-21 was characterized by higher values for the employees of the Yasny subdivision. Depressive and anxious states were uncharacteristic for the Karpogory loggers, while in their colleagues from Yasny they were manifested only slightly. It should be noted that despite higher professional stress, the employees of Yasny showed higher labor productivity - in the middle and at the end of the shift period, they statistically harvested more wood than their colleagues from Karpogory.

3.3. The Relationship Between Psychophysiological and Psychological Parameters of Professional Stress in Loggers in the Far North at the Beginning, Middle and End of the Shift Period

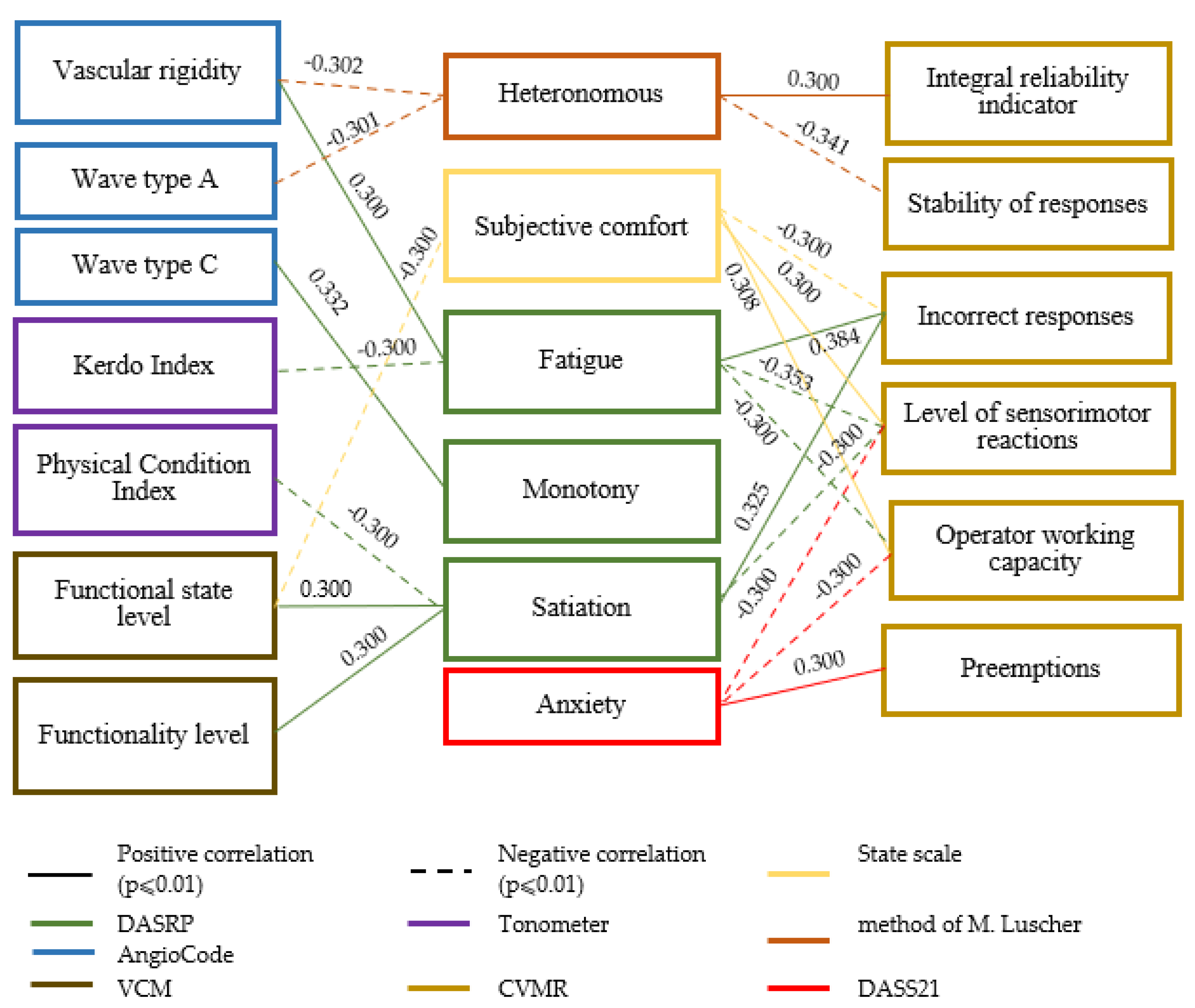

At the next stage of the study, to identify the relationship between the psychophysiological and psychological parameters of professional stress in loggers in the Far North at the beginning, middle and end of the shift period, we used correlation analysis (the Spearman coefficient). Based on its results three correlation pleiades were compiled for those parameters that have statistically significant relationships (

Figure 3,

Figure 4 and

Figure 5). In the correlation pleiad, only those factors are noted that have statistically significant relationships with a strength of 0.3 and at p≤0.001 (group error probability assessment (I type) according to the Bonferroni method in the Holm modification).

Figure 3.

The relationship between psychological and psychophysiological parameters of the functional state of loggers at the beginning of a shift (1-3 days, N=160).

Figure 3.

The relationship between psychological and psychophysiological parameters of the functional state of loggers at the beginning of a shift (1-3 days, N=160).

As can be seen in

Figure 3, a greater number of connections at the beginning of the shift period were established between the psychophysiological parameters of the CVMR method and the psychological parameters of the DASRWC, DASS21 and subjective comfort methods. At the same time, opposite trends were revealed: the more unfavorable the functional state (according to the VCM) is according to the hardware characteristics, the higher the workers rated their subjective comfort, and the higher their operator performance was according to the CVMR. This indicates, on the one hand, a compensatory reaction (increased performance due to a positive psychological attitude), and, on the other hand, the inadequacy of using only subjective-evaluation methods when monitoring the state. Employees strive to perform their work efficiently even with a decrease in their internal resources, which is explained by the peculiarity of the polar tension syndrome, when unfavorable changes are realized later than they manifest themselves at the body level [

23]. The agreement in the assessments of the state according to the DASRWC questionnaire with the hardware method of the CVMR and the parameters measured based on arterial pressure indicates its prognostic value. It is interesting to note that the higher the level of functional capabilities and functional state according to the VCM, the more pronounced is the satiety in workers. Also, the more dominant is the type of wave C according to AngioCode, which is more typical for young people under 30, the more pronounced is the monotony.

With sufficient internal resources at the beginning of the shift period, monotony and satiety develop more intensively. Perhaps, these employees need variety in work, which is impossible to implement in these work positions.

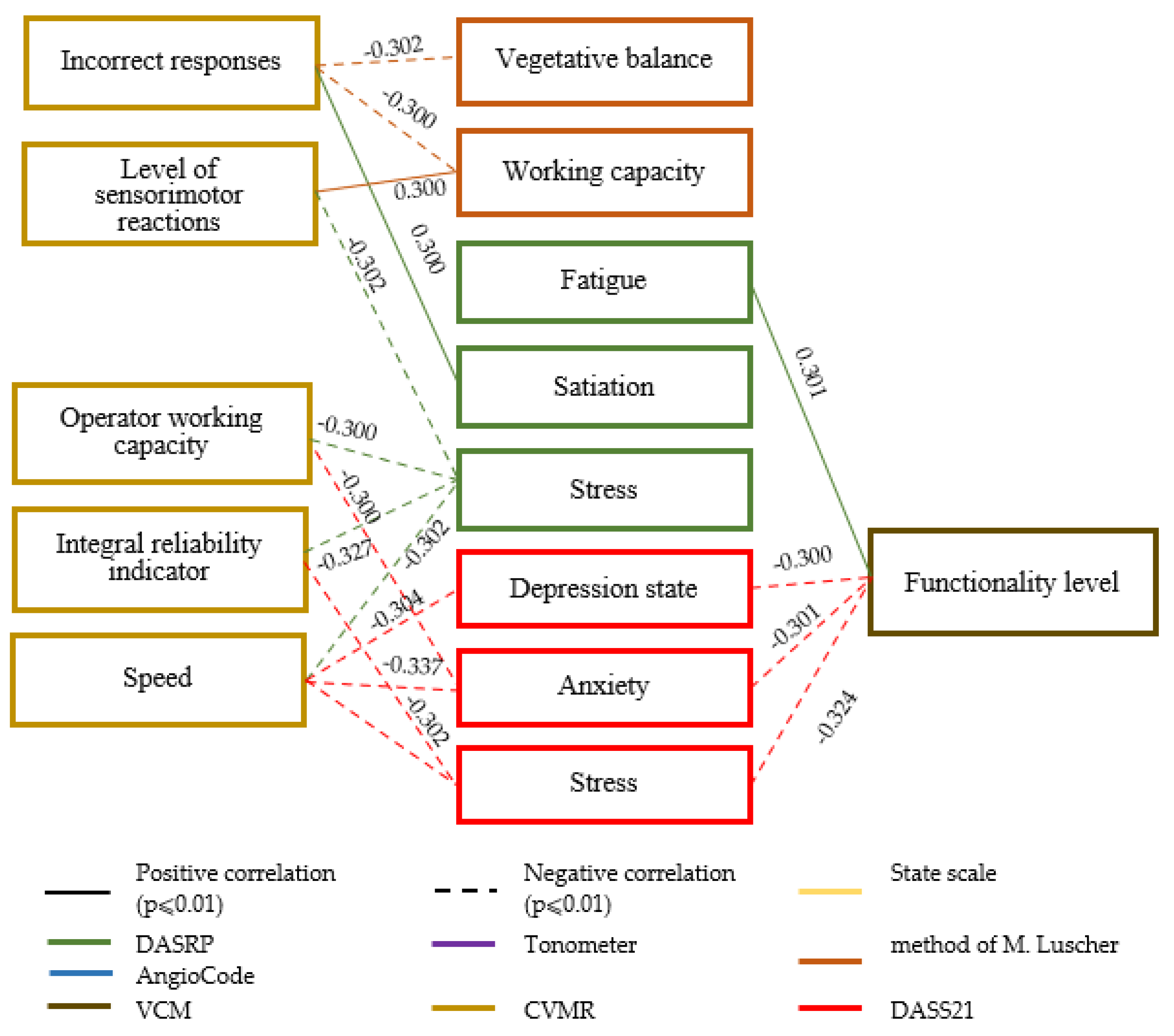

Figure 4.

The relationship between psychological and psychophysiological parameters of the functional state of loggers at the beginning of the shift (6-8 days, N = 188).

Figure 4.

The relationship between psychological and psychophysiological parameters of the functional state of loggers at the beginning of the shift (6-8 days, N = 188).

In the middle of the shift period (

Figure 4), statistically significant relationships were established between the parameters of the DASRWC and CVMR methods: the higher the stress, the lower the operator performance, the higher the satiety, the more errors in performing CVMR. The lower the level of functional capabilities according to the VCM, the more anxiety, stress and depressive states were manifested according to DASS21. This indicates consistency in the assessments of the psychological and psychophysiological parameters of the functional states of employees. At the same time, the higher the level of functional capabilities, the more fatigue is expressed in loggers. As indicated earlier, in the middle of the shift period there is a shift change, which is an additional stress factor. However, if there are internal reserves, workers cope with this, experiencing fatigue, but an insufficient level of resources leads to the development of stress, anxiety and depressive states during this period.

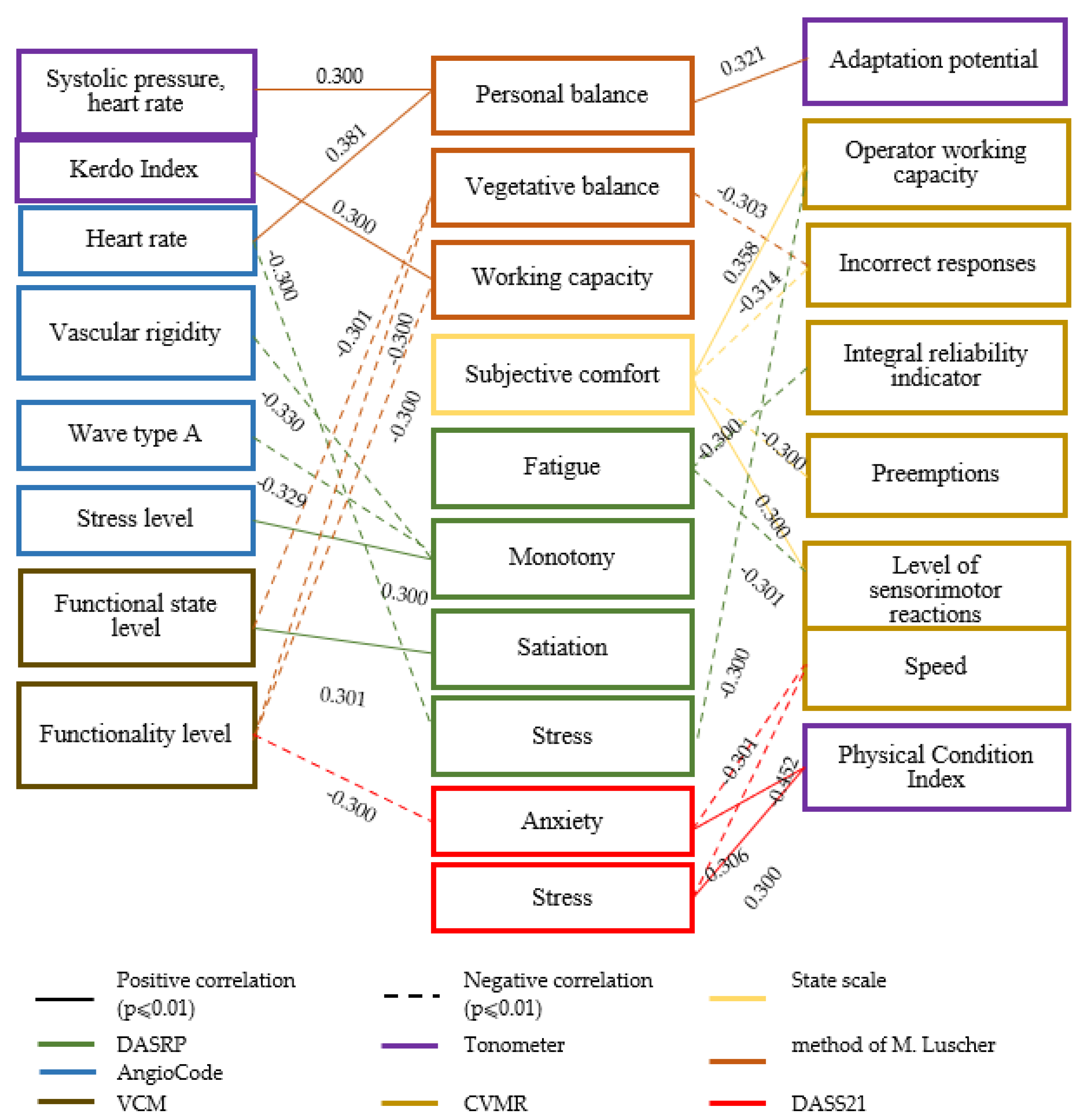

Figure 5.

Interrelationship between psychological and psychophysiological parameters of the functional state of loggers at the end of the shift (11-13 days, N=164).

Figure 5.

Interrelationship between psychological and psychophysiological parameters of the functional state of loggers at the end of the shift (11-13 days, N=164).

According to the data in

Figure 5, at the end of the shift period, as well as at the beginning, a greater number of statistically significant relationships were established between the psychological and psychophysiological parameters of the functional state of loggers. Significant relationships were found between the parameters measured using the DASRWC method and the VCM, CVMR and Angiocode methods. The higher the monotony, the higher the stress level and the more elastic the vessels (Angiocode); the higher the fatigue, the lower the level of sensorimotor reactions; the higher the stress, the lower the operator performance of loggers at the end of the shift period; the lower the level of functional capabilities, the higher the anxiety. The opposite trend was found between the parameters of M. Luscher’s and VCM methods: the lower the level of functional capabilities, the higher the performance (according to the projective indicator). As at the beginning of the shift period, such trends indicate the active inclusion of mechanisms of psychological regulation of functional states. The results obtained are partially consistent with foreign researchers who found that levels of perceived stress are not associated with levels of physiological stress [

8,

50]. Hjortskov and colleagues found that at low and medium levels of perceived stress, physiological stress may not occur, and when perceived stress is high, an increase in physiological stress may be observed [

50].

4. Discussion

The results of this study made it possible to determine the specifics of the functional states of loggers at different stages of the summer shift, which are consistent with the data obtained in another expedition in December 2020 at a forest plot near the village of Karpogory [

23]. The following general trends were established: throughout the shift period, favorable functional states and a high level of functional capabilities were observed (in this study, workers had a close to optimal state and above average functional capabilities); operator performance (OP) below average; high performance and low stress (according to M. Luscher’s method and G.A. Aminev’s coefficients ); well-being, activity and mood (WAM) at a high level (in this study, subjective comfort at a moderate level). At the same time, a number of authors have found that logging is more difficult and less productive in summer than in winter. One of the reasons for this is hot weather (from 35° to 37°C), which contributes to overheating of equipment and more frequent cleaning of air filters when working near dusty roads, as well as more equipment problems. Hot weather leads to increased operator fatigue, which affects their productivity. [

51]. In addition, in summer, trees need to be passed 4 or 5 times through the harvester head for better debarking of logs, and in winter 1-2 passes are enough. Operator fatigue and equipment problems in summer are increased by long shifts, which leads to a decrease in average productivity per shift of up to 34% [

51]. E. Lagerstrom et al. found that there are more accidents in summer [

52]. The present study did not establish such links regarding more unfavorable conditions in the summer compared to the winter. Numerous studies have found that levels of perceived stress are not related to levels of physiological stress [

53,

54] etc. Hjortskov et al. believe that average levels of perceived stress may not cause a response in the form of physiological stress. However, when perceived stress is high, this can contribute to an increase in physiological stress [

50]. Other authors have also found that people with low levels of perceived stress do not have a connection between perceived and physiological stress levels [

53,

54].

The form of perceived stress is also important and can influence the level of physiological stress. Stress experiences associated with uncertainty, novelty, distress, anxiety, helplessness, or lack of control trigger physiological stress reactions more often than other forms of stress (e.g., habitual or ordinary stress) [

50,

55]. The relationships between age and stress level, as well as length of service and fatigue in employees, obtained in the study, are consistent with the results of other authors. A study by H. Kymalainen et al. found a decrease in performance with age in forest machine operators in Finland [

56]. In the present study, the beginning and end of the shift were characterized by a higher level of stress reaction in older forest harvesters. Moreover, psychological methods demonstrate a connection with the length of service of workers only at the beginning of the shift, which, in our opinion, is associated with an orienting reaction - an attempt to assess the upcoming difficulties and prepare to overcome them. This is not true for less experienced loggers because of their lack of a differentiated image of the labor object during the shift. The influence of experience on the functional state of employees demonstrates the opposite nature of the relationship between stress and age in the middle of the shift, which confirms the completion of the orienting stage for professionals, in contrast to beginners, against the background of resources that have not yet been spent. The hypothesis of the study was confirmed: due to the greater stressfulness of the adaptation and completion stages of the shift, a greater consistency of various assessments of the functional states of loggers is expected compared to the more favorable period in the middle of the shift. Consistent relationships between objective (CVMR) and projective (the Luscher method) parameters were established, as well as multidirectional relationships between subjective comfort and objective parameters of the functional state of loggers, which is consistent with the results of our previous study conducted on a sample of shift workers in the oil and gas production industry in the Arctic [

24]. In our previous study, the maximum number of relationships was established between objective indicators of cortisol in saliva (stress), CVMR indicators (operator working capacity), VCM (level of functionality) and interpretation coefficients (performance, stress, vegetative balance) according to the Luscher′ test in shift personnel [

24]. The present study has revealed a greater number of statistically significant relationships between the parameters of functional states measured using the following methods: 1) DASRWC, CVMR methods and coefficients based on blood pressure measurements; 2) subjective comfort methods and parameters of the AngioCode device; 3) G.A. Aminev’s interpretation coefficients for the Luscher test and the CVMR method parameters.

The addition of the DASRWC, DASS21 questionnaires to the study design and the calculation of pressure-based coefficients made it possible to establish the specifics of changes in the functional states of shift workers of a logging company and use these data in practical work at enterprises. Due to the fact that blood pressure is measured during pre-shift examinations at logging sites, the calculation of additional indicators based on it and correlation of individual results with the obtained links with other parameters of workers’ states will allow giving feedback to workers about their condition and recommendations for its optimal maintenance during the shift. The obtained reliable statistically significant links between the equipment parameters and the results of the DASRWC and DASS21 questionnaires substantiate the adequacy of their use separately from psychophysiological testing. Such comprehensive monitoring of the functional state of workers will ensure control and timely intervention of psychologists and labor physiologists in order to correct them for the purpose of maintaining the health and professional longevity of workers.

The hypothesis that dynamic shifts in the functional states of loggers during the shift period are positively associated with positive socio-psychological characteristics of the logging team was partially confirmed. Loggers working in a team with positive socio-psychological characteristics are distinguished by a more favorable level of functional state during the shift period.

Communication in a team is important not only in terms of productivity, but also in terms of mental health. Team members experience greater stress when they cannot discuss personal problems with their peers [

57].

Even when there are no overt conflicts, team performance may decline with prolonged exposure to the environment. Palinkas et al. in his study of multinational crews at Antarctic research stations found that the percentage and number of crew members seeking interaction declined over the course of the mission (8 months) [

20].

A. G. Shchurov points out that the "Group Cohesion Index of K. E. Sishor’s" [

58] method can be used to study a ship’s crew group cohesion. The study yielded data indicating a fairly high level of group cohesion.

V. I. Lebedev interprets group isolation as the forced presence of a group of people in a limited space, with a minimum of sensory stimuli and constant contact with the same people [

59]. There are several negative impacts on members of such groups: the nervous system becomes weaker, which is expressed in increased irritability and emotional outbursts in conflict situations; exhaustion from lack of information; the need for constant self-control and concealment of true emotions due to the constant presence of other people; the feeling of loneliness caused by the inability to choose one’s social circle; the impact of work schedule at some enterprises on the general condition of employees. These features of social interaction can lead to unfavorable functional states and decreased work efficiency [

59]. D. K. Sharipov conducted a study to assess the adaptation of the body in conditions of low temperature and isolated environment of Antarctica [

60].

Limitations of the study. The limitation of the study was the inclusion in the sample of the study of only representatives of three professional groups (logging equipment operators, truck drivers and maintenance workers). Also, the study was conducted in one of the regions of the Russian Federation, which can be clarified when conducting research in other regions with different climatic conditions and terrain specifics. The results obtained are based on the methods of interviews, questionnaires, psychophysiological and psychological testing.

5. Conclusions

Statistically significant relationships were established between the psychophysiological and psychological parameters of the functional states of loggers in the Arctic zone of the Russian Federation at the beginning, middle, and end of the 15-day shift period. Due to the greater stressfulness of the adaptation and fatigue stages at the end of the shift, a greater consistency of various assessments of the functional states of loggers at the beginning and end of the shift period was revealed compared to the more favorable period in the middle of the shift. At the same time, at the beginning and end of the shift period, separate multidirectional trends were established in the assessments of the level of functional state and subjective comfort at the beginning of the period and the level of functional capabilities and performance (M. Luscher’s method, G.A. Aminev’s coefficient) at the end of the period, which may indicate mechanisms of psychological mobilization (maintaining the functional state due to a positive self-perception) of workers.

The obtained reliable statistically significant relationships between the equipment parameters and the results of the DASRWC questionnaire substantiate the adequacy of its use separately from psychophysiological testing. Such comprehensive monitoring of the functional state of workers will ensure control and timely intervention of psychologists and labor physiologists in order to correct them with the aim of maintaining the health and professional longevity of workers.

Loggers working in a team with positive socio-psychological characteristics are distinguished by a more favorable level of functional state during the shift period. They are characterized by moderate fatigue, satiety, monotony and stress, average operator working capacity, above average level of functional capabilities and the maximum permissible level of functional state (according to the VCM). This may also be associated with a higher level of adaptive abilities, flexibility as a regulatory quality and communicative potential. Loggers working in a team with moderate socio-psychological characteristics were characterized by a higher level of stress, below-average operator performance, an average level of functional capabilities, and an acceptable functional state level (according to the VCM). This may be due to the fact that their adaptive abilities are expressed at a level below average, and their communicative potential is low.

The indicator of the volume of timber harvested in the middle and at the end of the shift period is higher for employees from the group with moderate socio-psychological characteristics of the team. This may be due to their greater moral normativity, adherence to the standards adopted in the organization, and the desire to reach performance targets.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.K. and N.S. (Natalia Simonova); Data curation, Y.K. and N.S.; Formal analysis, Y.K. and N.S. (Natalia Simonova); Funding acquisition, Y.K.; Methodology, Y.K.; Supervision, Y.K. and N.S. (Natalia Simonova); Validation, Y.K. and N.S. (Natalia Simonova); Visualization, Y.K.; Writing—original draft, Y.K.; Writing—review & editing, N.S. (Natalia Simonova) and Y.K.. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Russian Science Foundation, grant number 24-28-00117.

Data Availability Statement

Certificate of registration of the database 2021621449, 07/05/2021. Application No. 2021621307 dated 06/24/2021. Dynamic study of the functional states of workers of a logging enterprise in the Far North during a rotational race.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Pecyna, A.; Buczaj, A.; Lachowski, S.; Choina, P. Occupational hazards in opinions of forestry employees in Poland. Ann. Agric. Environ. Med. 2019, 26, 242–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonseca, A.; Aghazadeh, F.; de Hoop, C.; Ikuma, L.; Al-Qaisi, S. Effect of noise emitted by forestry equipment on workers’ hearing capacity. Int J Ind Ergon. 2015, 46, 105–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poje, A.; Spinelli, R.; Magagnotti, N.; Mihelic, M. Exposure to noise in wood chipping operations under the conditions of agro-forestry. Int J Ind Ergon. 2015, 50, 151–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naskrent, B.; Grzywiński, W.; Polowy, K.; Tomczak, A.; Jelonek, T. Eye-Tracking in Assessment of the Mental Workload of Harvester Operators. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 5241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jankovský, M.; Messingerová, V.; Ferenčík, M.; Allman, M. Objective and subjective assessment of selected factors of the work environment of forest harvesters and forwarders. J. For. Sci. 2016, 62, 8–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masci, F.; Spatari, G.; Bortolotti, S.; Giorgianni, C.M.; Antonangeli, L.M.; Rosecrance, J.; Colosio, C. Assessing the Impact of Work Activities on the Physiological Load in a Sample of Loggers in Sicily (Italy). Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 7695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choina, P.; Solecki, L.; Goździewska, M.; Buczaj. A. Assessment of musculoskeletal system pain complaints reported by forestry workers. Ann Agric Environ Med. 2018, 25(2), 338–344. [CrossRef]

- Korneeva, Y.; Shadrina, N.; Simonova, N.; Trofimova, A. Job stress, working capacity, professional performance and safety of shift workers at forest harvesting in the North of Russian Federation. Forests 2024, 15, 2056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monsey, L. M.; Harrington, M.; Clonch, A.; Spector, J.; Vignola, E. F.; Baker, M.G. Exploring barriers and facilitators to well-being among logging industry workers: a mixed methods study. International Journal of Forest Engineering 2025, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lotfalian, M.; Emadian, S.F.; Riahi, F.N.; Salimi, M.; Sheikhmoonesi, F. EPA-0056 - Occupational Stress Impact on Mental Health Status of Forest Workers. European Psychiatry 2014, 29(S1), 1–1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Postolache, R.-G.; Timofte, A.I. Considerations on the health status of loggers in summer and winter working conditions. Annals of the University of Oradea, Fascicle: Environmental Protection 2024, 2, 105–108. [Google Scholar]

- Škvor, P.; Jankovský, M.; Natov, P.; Dvořák, J. Evaluation of stress loading for logging truck drivers by monitoring changes in muscle tension during a work shift. Silva Fennica 2023, 57, 1, 10709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wasmund, W.L.; Westrholm, E.C.; Watenpaugh, D.E.; Wasmund, S.L.; Smith, M.L. Interactive effects of mental and physical stress on cardiovascular control. J Appl Physiol 2002, 92, 1828–1834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuzewicz, K.; Roman-Liu, D.; Konarska, M.; Bartuzi, P.; Matusiak, K.; Korczak, D.; Guzek, M. Heart rate variability (HRV) and muscular system activity (EMG) in cases of crash threat during simulated driving of a passenger car. Int J Occup Med Env. 2013, 26, 710–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jodłowski, K.; Kalinowski, M. Current Possibilities of Mechanized Logging in Mountain Areas. Forest Research Papers 2018, 79, 365–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spinelli, R.; Magagnotti, N.; Labelle, E.R. The Effect of New Silvicultural Trends on Mental Workload of Harvester Operators. Croatian journal of forest engineering 2020, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Driskell, J.E.; Driskell, T.; & Salas, E. Teams in Extreme Environments: Alterations in Team Development and Team Functioning In: Team Dynamics Over Time (Research on Managing Groups and Teams, Vol. 18). Editors: E. Salas, W.B. Vessey, A.X. Estrada. Publisher: Emerald Publishing, 2017 Pages: 161-185. [CrossRef]

- Bishop, SL. Team dynamics analysis of the Huautla cave diving expedition: a case study. Journal of Human Performance in Extreme Environments 1998, 3, 37–41. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, O. Monitoring changes in cohesion over time in expedition teams; the role of daily events and team composition. 14th International Naturalistic Decision-Making Conference At: San Francisco, USA, 2019; Mode of access : https://www.researchgate.net/publication/341407404_Monitoring_changes_in_cohesion_over_time_in_expedition_teams_the_role_of_daily_events_and_team_composition, free access (10.03.2025). [Google Scholar]

- Palinkas, L.A. & Suedfeld, P. Psychological effects of polar expeditions. The Lancet 2008, 371(9607), 153–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stuster, J. Behavioral Issues Associated with Isolation and Confinement: Review and Analysis of Astronaut Journals. NASA Technical Report (NASA/TM-2011-216146)* Publisher: NASA Ames Research Center, 2011, Pages: 1-192 URL: https://ntrs.nasa. 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leon, G.R.; Kanfer, R.; Hoffman, R.G.; Dupre, L. Group processes and task effectiveness in a Soviet-American expedition team. Environment and Behavior 1994, 26(2), 149–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korneeva, Ya.A.; Simonova, N.N.; Korneeva, A.V.; Trofimova, A.A. Functional states of workers in the logging industry in the Far North during the shift period. Acta Biomedica Scientifica 2022, 7(4), 138–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korneeva, Y.; Simonova, N. Job stress and working capacity among fly-in-fly-out workers in the oil and gas extraction industries in the Arctic. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 7759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parkes, K.R. Psychosocial aspects of work and health in the north. sea oil and gas industry: summaries of reports published 1996–2001. Norwich, UK Health Safety Executive: 2002, 98.

- Gent, V.M. The impacts of fly-in/fly-out work on well-being and work-life satisfaction. master’s thesis, school of psychology. Perth, Australia: Murdoch University, 2004.

- Gallegos, D. Fly-In Fly-Out Employment: Managing the Parenting Transitions. Summary and Key Findings. Perth, Australia: Ngala & Meerilinga, 2006.

- Clifford, S. The Effects of Fly-In/Fly-Out Commute Arrangements and Extended Working Hours on the Stress, Lifestyle, Relationship and Health Characteristics of Western Australian Mining Employees and their Partners: Report of Research Findings. Master’s Thesis, . Crawley, Australia: School of Anatomy and Human Biology, The University of Western Australia, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- NPKF “Medicom MTD”. Methodological Guide A_2556-05_MS. Psychophysiological Testing Device UPFT-1/30—"Psychophysiologist”; NPKF “Medicom MTD”: Taganrog, Russia, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Health tracker AngioCode-301. User manual. [Electronic resource] https://angiocode.ru/files/RU/AngioCodePersonal/SFX/AC-301_Device_Manual.pdf.

- Gliko, L.I.; Reshetnev, V.G.; Reshetneva, E.M. Mathematical method for assessing individual indicators of human hemodynamics. Series: Diagnostic hemodynamics. Issue 3. Clinical diagnostic criteria of the mathematical method. St. Petersburg, Russia: 1 Central Research Institute of the Ministry of Defense of the Russian Federation, 1996; 20.

- Leonova, A. B.; Kapitsa, M. S. Methods for assessing mental performance and functional states. Bulletin of Moscow University. Series 14. Psychology 1998, 2. [Google Scholar]

- Bullinger, M.; Morfeld, M.; Hoppe-Tarnowski, D. POMS. Profile of Mood States. In: Schumacher J, Klaiberg A, Braehler E (Hrsg) Diagnostische Verfahren zu Lebensqualität und Wohlbefinden. Hogrefe, Göttingen, 2003, 262–264.

- Zerssen, von D.; Koeller, D.M. Die Befindlichkeits-Skala. Parallelformen Bf-S und Bf-SI aus: Klinische Selbstbeurteilungs-Skalen (Ksb-S) aus dem Münchener Psychiatrischen Informations-System (PSYCHIS München). Beltz, Weinheim. 1976.

- Luscher, M. The Luscher Colour Test; Sydney, L., Ed.; Pocket Books: New York, NY, USA. 1983.

- Aminev, G.A. Mathematical Methods in Engineering Psychology; Bashkir State University: Ufa, Russia, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Leonova, A.B.; Velichkovskaya, S.B. Differential diagnostics of states of reduced performance. In Psychology of Mental States: Dedicated to the 200th Anniversary of Kazan University; Center for Innovation Technologies: Kazan, Russia, 2002; pp. 326–343. [Google Scholar]

- Plath, H.; Richter, P. Ermüdung, Monotonie, Sättigung, Stress: Verfahren zur skalierten Erfassung erlebter Beanspruchungsfolgen; BMS Psychodiagnostisches Zentrum: Berlin, Germany, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Lovibond, P.F.; Lovibond, S.H. The structure of negative emotional states: Comparison of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS) with the Beck Depression and Anxiety Inventories. Behaviour Research and Therapy 1995, 33, 335–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lovibond, S.H. , & Lovibond, P.F. Manual for the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (2nd ed. Sydney: Psychology Foundation of Australia. 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Ruzhenkova, V. V.; Ruzhenkov, V. A.; Khamskaya, I. S. Russian-language adaptation of the DASS-21 test for screening diagnostics of depression, anxiety and stress. Bulletin of Neurology, Psychiatry and Neurosurgery 2019, 10, 39–46. [Google Scholar]

- Zolotareva, A.A. Psychometric assessment of the russian-language version of the depression, anxiety, and stress scale (DASS-21). Psychological journal 2021, 42, 5, 80–88. [Google Scholar]

- Seashore, S.E. Group cohesiveness in the industrial work group. Ann Arbor (USA): University of Michigan, 1954.

- Dontsov, A.I. Psychology of the collective. Moscow: Publishing house of Moscow University, 1984.

- Fiedler, F. E. A theory of leadership effectiveness. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1967.

- Fiedler, F. E. The contingency model and the dynamics of the leadership process. University Of Washington, Seattle. Washington, 1978.

- Khanin, Yu.L. Psychology of Communication in Sports. Moscow: Physical Education and Sport. 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Rozanova, V. A. Psychology of Management: a tutorial. Moscow: Alfa-Press Publishing House, 2007.

- Mikhalyuk, O. S.; Shalyto, A. Yu. Social and psychological climate of the team and personality. Psychological problems of social regulation of behavior, Moscow: Science. 1976; 300–312. [Google Scholar]

- Hjortskov, N.; Garde, A.H.; Ørbæk, P.; Hansen, A.M. Evaluation of salivary cortisol as a biomarker of self-reported mental stress in field studies. Stress Health 2004, 20, 91–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Passicot, P.; Murphy, G.E. Effect of work schedule design on productivity of mechanised harvesting operations in Chile. N. Z. J. For. Sci. 2013, 43, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lagerstrom, E.; Magzamen, S.; Rosecrance, J. A mixed-methods analysis of logging injuries in Montana and Idaho. Am. J. Ind. Med. 2017, 60, 1077–1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Eck, M.; Berkhof, H.; Nicolson, N.; Sulon, J. The effects of perceived stress, traits, mood states, and stressful daily events on salivary cortisol. Psychosom. Med. 1996, 58, 447–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pruessner, J.C.; Hellhammer, D.H.; Kirschbaum, C. Burnout, perceived stress, and cortisol responses to awakening. Psychosom. Med. 1999, 61, 197–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frankenhaeuser, M. A Psychobiological Framework for Research on Human Stress and Coping. In Dynamics of Stress; Appley, M.H., Trumbull, R., Eds.; New York, NY, USA: Plenum, 1986; pp. 101–106. [Google Scholar]

- Kymalainen, H.; Laitila, J.; Väätäinen, K.; Malinen, J. Workability and well-being at work among cut-to-length forest machine operators. Croatian journal of forest engineering, 2021, 42. [CrossRef]

- Kjærgaard, A.; Leon, G. R.; Fink, B.A. Personal challenges, communication processes, and team effectiveness in military special patrol teams operating in a polar environment. Environment and Behavior 2015, 47(6), 644–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shchurov, A. G.; Lobzha, M. T.; Koshkarev, P. V.; Tikhonov, S. Yu. Formation of cohesion of the crew of a surface ship as one of the specific tasks of physical training. Psychological, pedagogical and medical-biological support of physical education and sports 2020, 4, 183–186. [Google Scholar]

- Lebedev, V. I. Psychology and psychopathology of loneliness and group isolation: a textbook for students of the psychological faculties of medical and humanitarian institutes, cadets of transport schools, Unity-Dana: Moscow, 2002.

- Sharipov, D. K. Adaptation of the human body in conditions of aggressively low temperature and isolated environment of Antarctica. Bulletin of KazNMU 2017, 1. Access mode: https://cyberleninka.ru/article/n/adaptatsiya-chelovecheskogo-organizma-v-usloviyah-agressivno-nizkoy-temperatury-i-izolirovannoy-sredy-antarktidy.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).