Submitted:

25 July 2025

Posted:

30 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

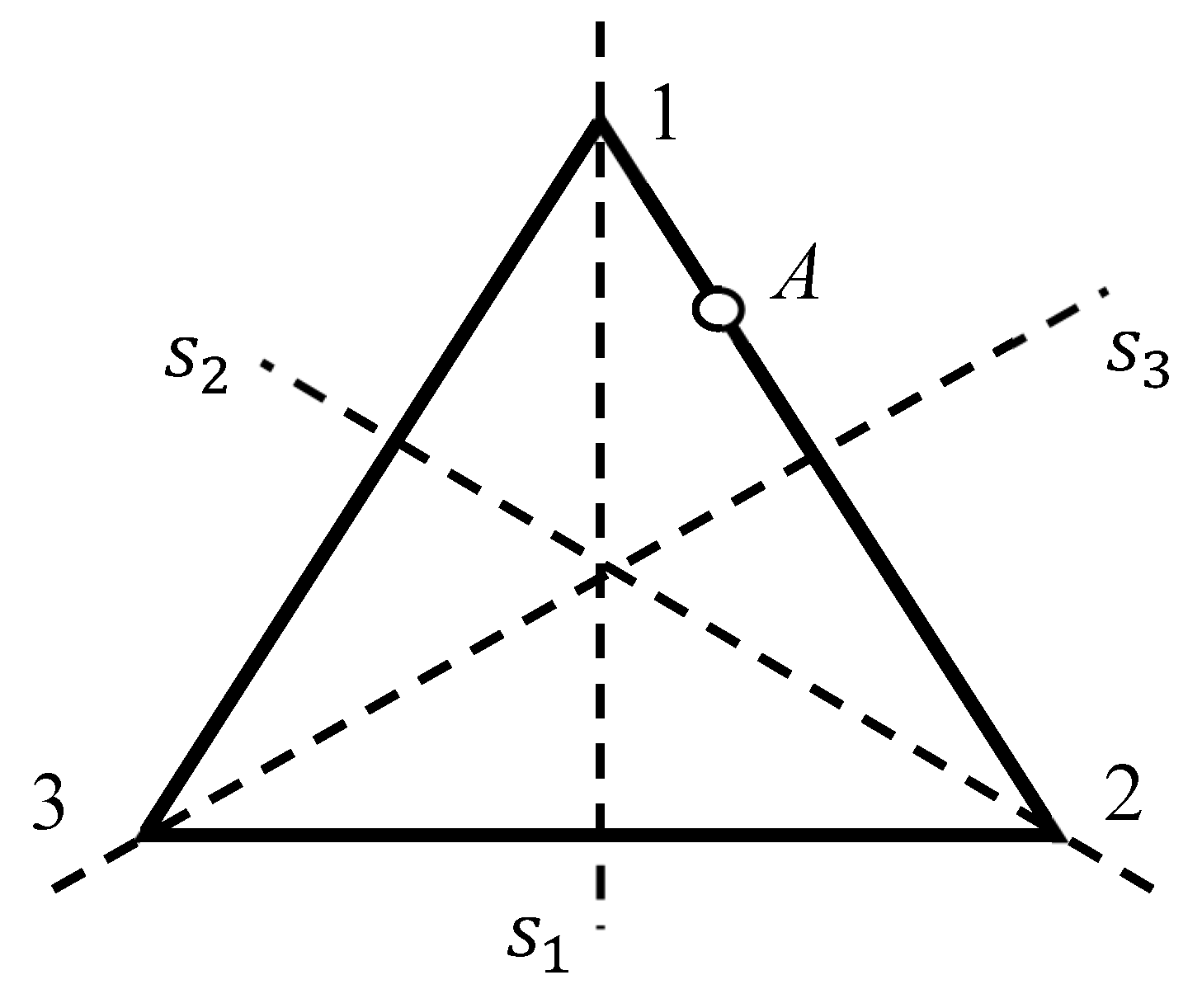

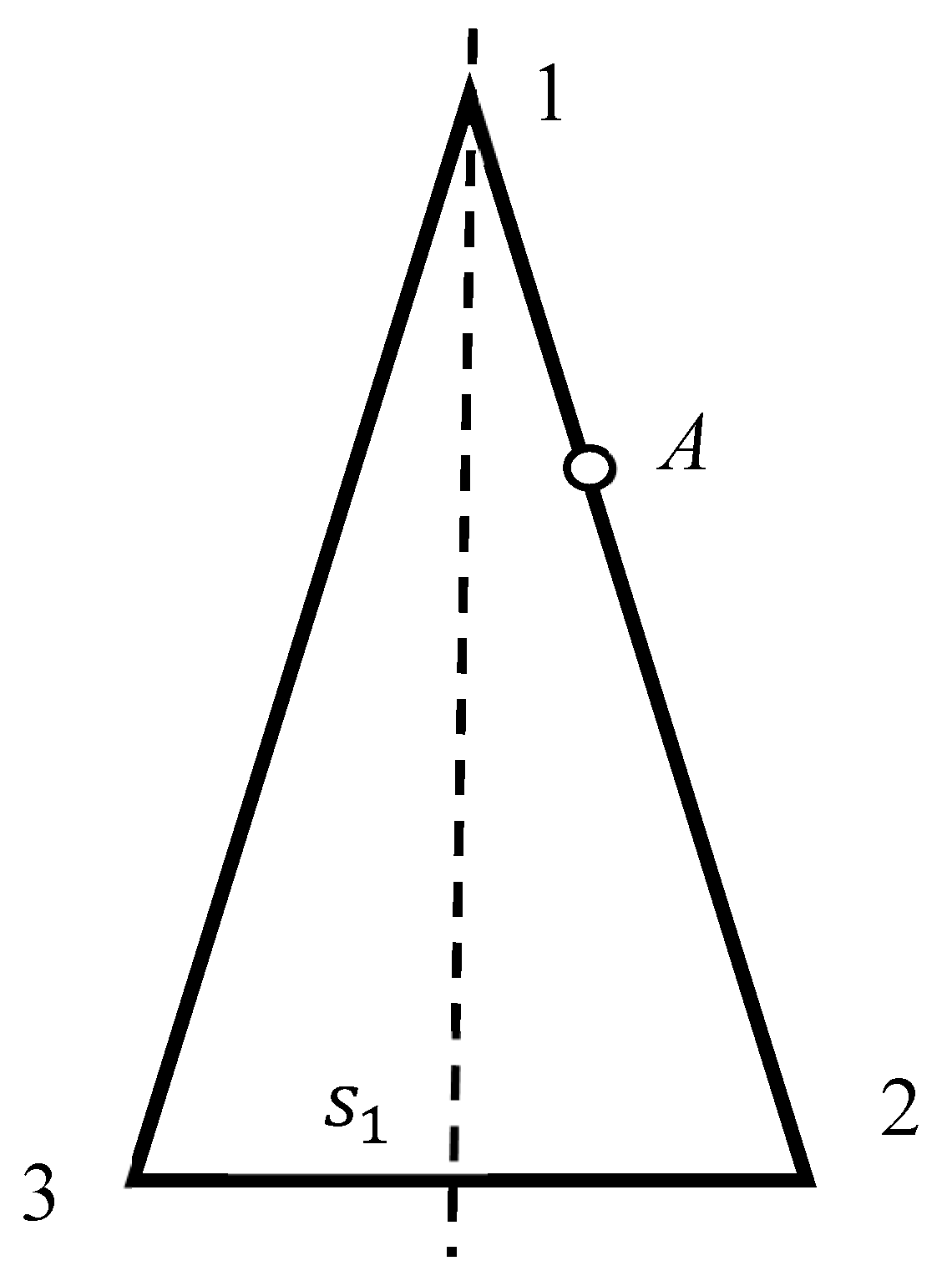

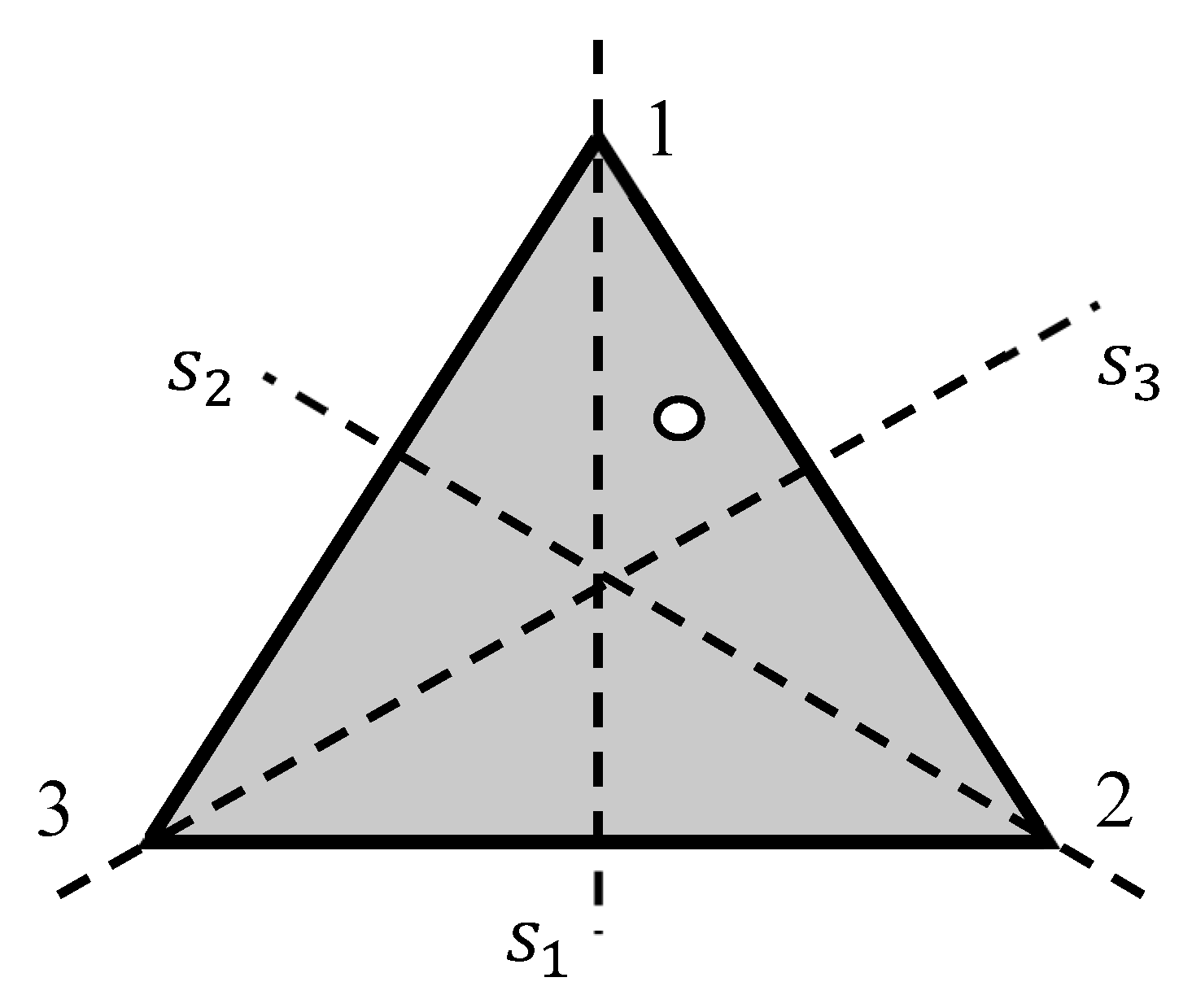

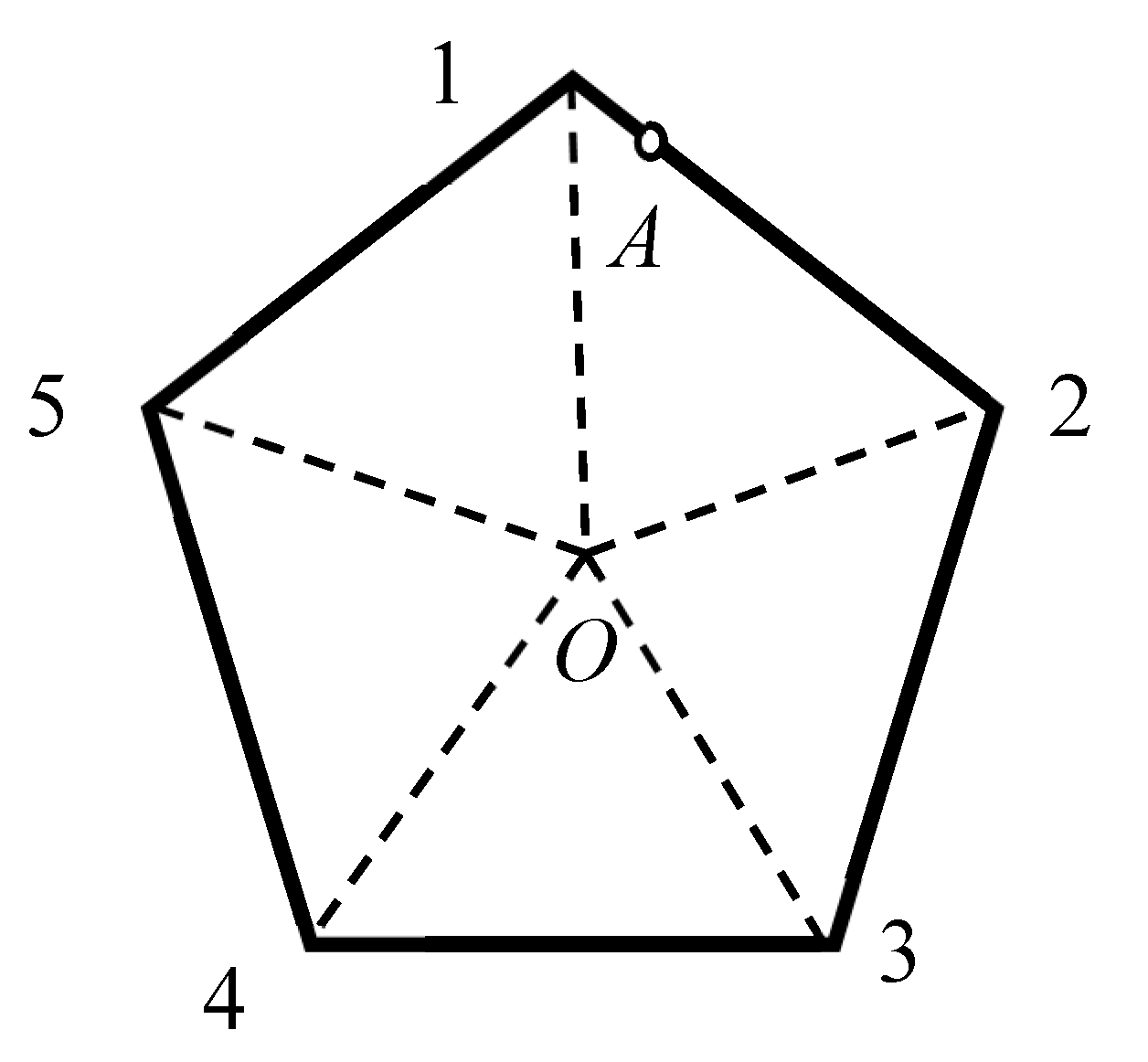

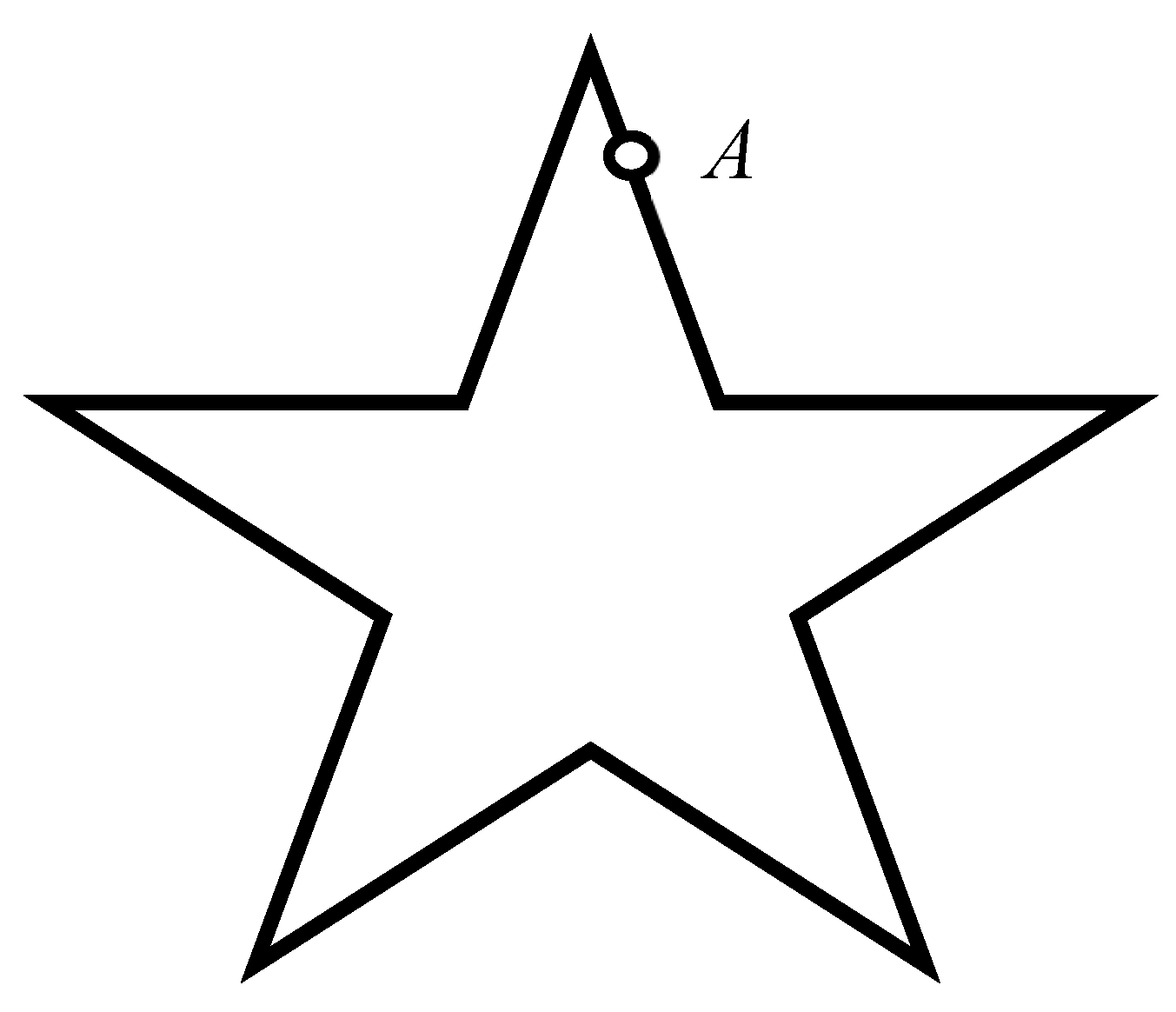

2.1. Breaking the Symmetry of Regular Polygons

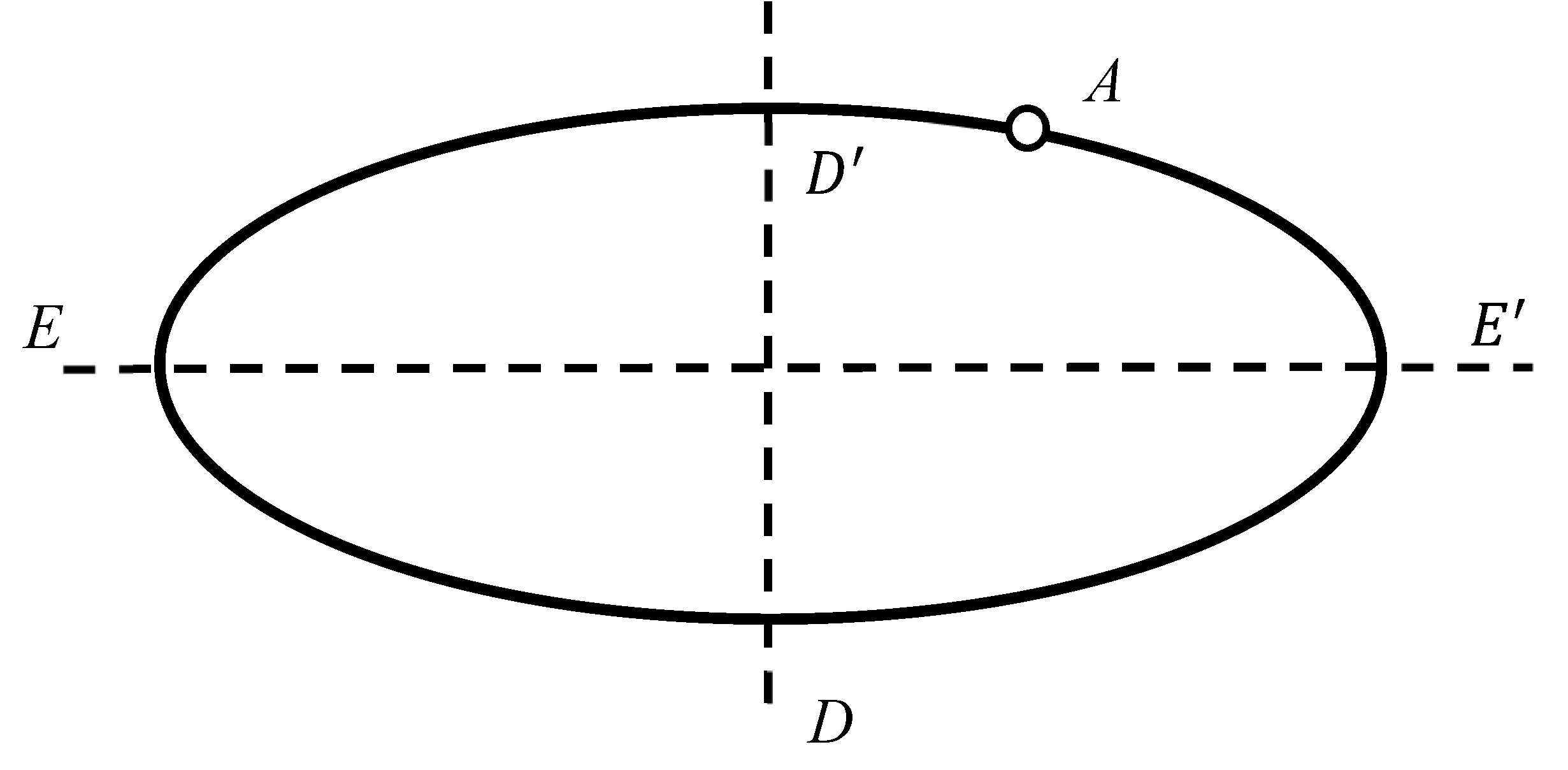

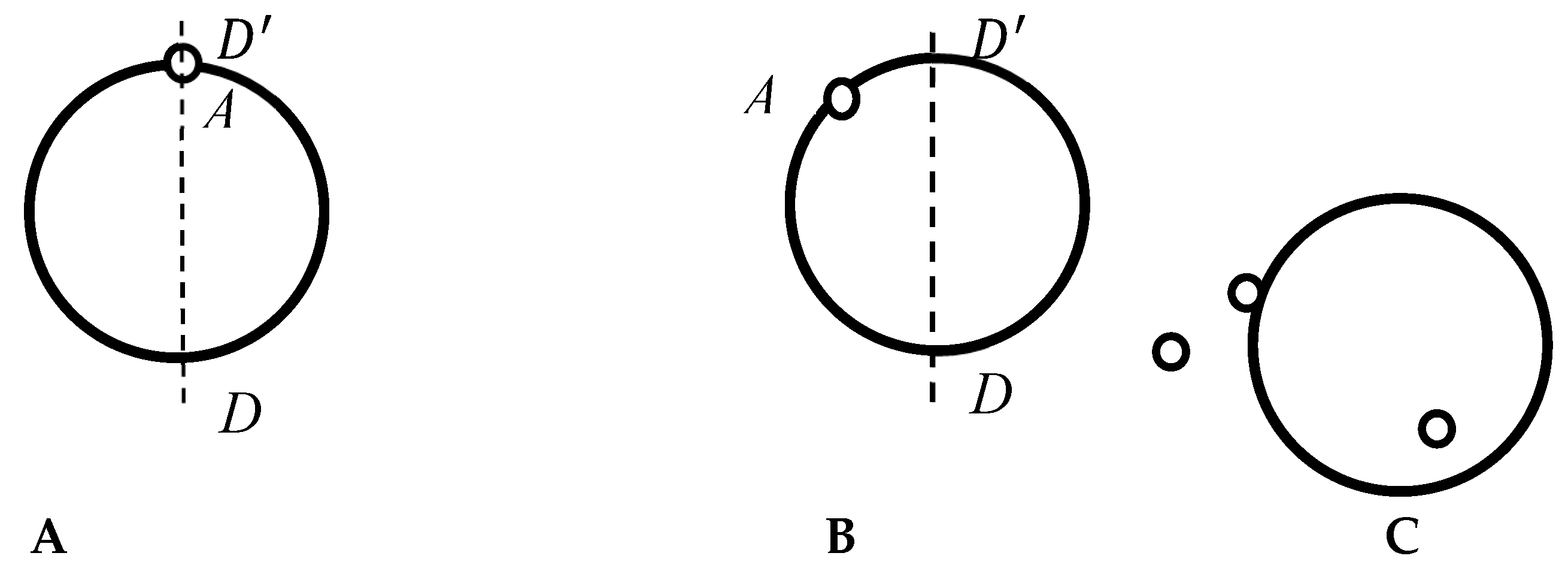

2.2. Breaking the Symmetry of the Curves

- (i)

- Circles, which is symmetry is reduced to the trivial group by removing of a triad of non-symmetrical points. The same is true for solid and open circles.

2.3. Extension for Symmetrical Jordan Curves

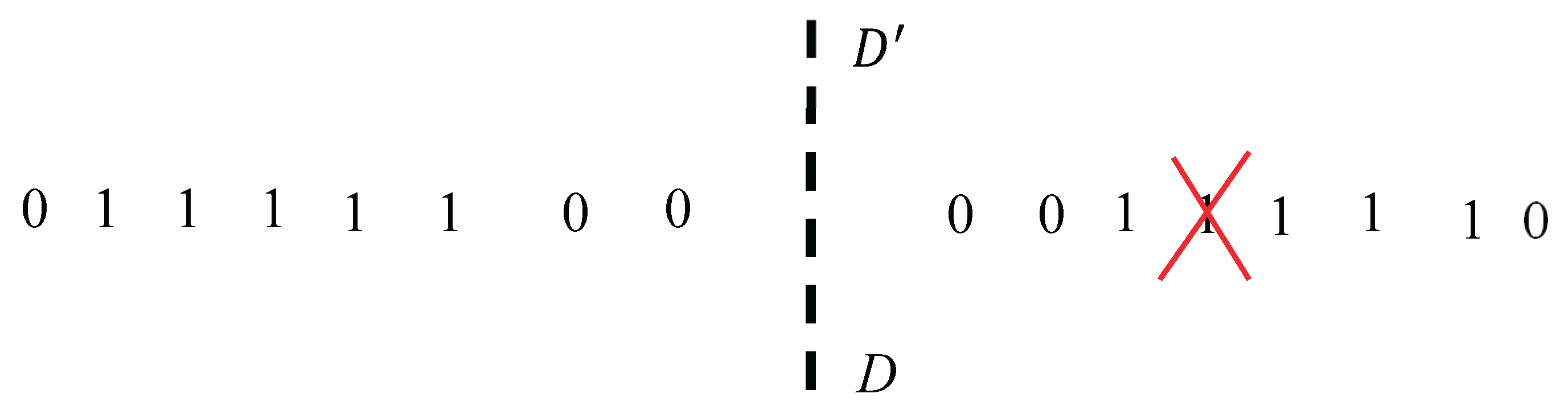

2.4. Informational Interpretation of the Suggested Approach: Erasure of the Single Bit Enables Breaking Symmetry of the Entire String Program

3. Discussion

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Strocchi, F. Symmetry Breaking; Volume 732 of Lecture Notes in Physics; Springer Verlag: Berlin, Germany, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Nambu, Y. Nobel lecture: spontaneous symmetry breaking in particle physics: a case of cross fertilization. Rev. Mod. Phys. 2009, 81, 1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgs, P.W. Spontaneous Symmetry Breakdown without Massless Bosons. Phys. Rev. 1966, 145, 1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgs, P. W Broken symmetries and the masses of gauge bosons. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1964, 13, 508–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trenkwalder, A.; Spagnolli, G.; Semeghini, G.; Coop, S.; Landini, M.; Castilho, P.; Pezzè, L.; Modugno, G.; Induscio, M.; Smerzi, I.A.; Fattori, M. Quantum phase transitions with parity-symmetry breaking and hysteresis. Nature Phys. 2016, 12, 826–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanada, M.; Robinson, B. Partial-symmetry-breaking phase transitions. Phys. Rev. D 2020, 102, 096013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izyumov, Y.A.; Syromyatnikov, V.N. Phase Transitions and Crystal Symmetry; Kluwer, Academic Publishers: Boston, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Landau, L.D.; Lifshitz, E.M. Statistical Physics, 3rd ed.; Course of Theoretical Physics; Elsevier: Oxford, UK, 2011; Volume 5. [Google Scholar]

- Tipeev, A.O.; Schmelzer, J.W.P.; Zanotto, E.D. On thermodynamic and kinetic spinodals in supercooled liquids. Chemical Physics Letters 2024, 836, 141051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abyzov, A.S.; Schmelzer, J.W.P. Nucleation versus spinodal decomposition in confined binary solutions. J. Chem. Physics 2007, 127, 114504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bormashenko, E. Ramsey theory of the phase transitions of the second order. Pramana - J Phys 2025, 99, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafi, Q.; Vilenkin, A. Spontaneously broken global symmetries and cosmology. Phys. Rev. D 1984, 29, 1870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, L.; Hasan, T.; Castellanos-Gomez, A.; Liu, G.-B.; Yao, Y.; Lau, C.N.; Sin, Z. Engineering symmetry breaking in 2D layered materials. Nat. Rev. Phys. 2021, 3, 193–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Zhao, J.; Luo, L.; Du, J.; Zeng, J. Symmetry-Breaking Sites for Activating Linear Carbon Dioxide Molecules. Acc. Chem. Res. 2021, 54, 1454–1464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korenić, A.; Perović, S.; Ćirković, M.M.; Miquel, P.-A. Symmetry breaking and functional incompleteness in biological systems. Progress Biophysics Molecular Biology 2020, 150, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McManus, I.C. Symmetry and asymmetry in aesthetics and the arts. European Review 2005, 13, 157–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landauer, R. Minimal energy requirements in communication. Science 1996, 272, 1914–1918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrera, L. The mass of a bit of information and the Brillouin’s principle. Fluctuation Noise Letters 2014, 13, 1450002-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bérut, A.; Arakelyan, A.; Petrosyan, A.; Ciliberto, S.; Dillenschneider, R.; Lutz, E. Experimental verification of Landauer’s principle linking information and thermodynamics. Nature 2012, 483, 187–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piechocinska, B. Information erasure. Phys. Rev. A 2000, 61, 062314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parrondo, J.M.R.; Horowitz, J.M.; Sagawa, T. Thermodynamics of information. Nature Phys. 2015, 11, 131–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, J.G. Events as Elements of Physical Observation: Experimental Evidence. Entropy 2024, 26, 255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vopson, M. The mass-energy-information equivalence principle. AIP Advances 2019, 9, 095206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bormashenko, Ed (Ed.) Landauer Bound in the Context of Minimal Physical Principles: Meaning, Experimental Verification, Controversies and Perspectives. Entropy 2024, 26, 423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Witkowski, K.; Brown, S.; Truong, K. On the Precise Link between Energy and Information. Entropy 2024, 26, 203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chattopadhyay, P.; Misra, A.; Pandit, T.; Paul, G. Landauer principle and thermodynamics of computation. Reports Progress Physics 2025, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diamantini, M.C. Landauer Bound and Continuous Phase Transitions. Entropy 2023, 25, 984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imrich, W.; Klavžar, S. Distinguishing Cartesian powers of graphs. J. Graph Theory 2006, 53, 250–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alper, J.; Halpern-Leistner, D.; Heinloth, J. Existence of moduli spaces for algebraic stacks. Invent. Math. 2023, 234, 949–1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beekman, A.J.; Rademaker, L.; van Wezel, J. An introduction to spontaneous symmetry breaking. SciPost Phys. Lect. Notes 2019, 11, 1–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.-Y.; Chiang, H.-W.; Patel, A. Resonant orbits of rotating black holes beyond circularity: Discontinuity along a parameter shift. Phys. Rev. D 2023, 108, 064016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez, N. Crystal Defects. In Materials Science: Theory and Engineering; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Venkataiah, G.; Prasad, V.; Reddy, P.V. Influence of A-site cation mismatch on structural, magnetic and electrical properties of lanthanum manganites. J. Alloys Compounds 2007, 429, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simpkins, B.S.; Dunkelberger, A.D.; Vurgaftman, I. Control, Modulation, and Analytical Descriptions of Vibrational Strong Coupling. Chem. Rev. 2023, 123, 5020–5048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, P.; Fan, W.; Chen, Y.; Feng, J.; Sareh, P. Structural symmetry recognition in planar structures using Convolutional Neural Networks. Engineering Structures 2022, 260, 114227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fomin, P.I.; Gusynin, V.P.; Miransky, V.A.; Sitenko, Y.A. Dynamical symmetry breaking and particle mass generation in gauge field theories. Riv. Nuovo Cim. 1983, 6, 1–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tozzi, A.; Peters, J.F. Symmetries, Information and Monster Groups before and after the Big Bang. Information 2016, 7, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).