1. Introduction

Stroke remains the leading cause of acquired neurological disability worldwide, with gait recovery being a central focus of post-stroke rehabilitation efforts [

1,

2]. Despite advances in therapy, a substantial proportion of survivors retain walking deficits that reduce autonomy and quality of life.

Functional Electrical Stimulation (FES) has been used for decades to improve motor function in individuals with upper motor neuron lesions, including post-stroke patients [

3,

4,

5]. When applied during walking, FES can enhance muscle recruitment, improve gait speed and symmetry, and support neuromuscular plasticity [

6,

7,

8]. However, widespread adoption in clinical practice remains limited. Key barriers include the complexity of device setup, the need for manual electrode placement, and the requirement for advanced expertise to adjust stimulation parameters [

9,

10,

11].

Most commercially available systems are either overly simplistic or highly technical, with steep learning curves and cumbersome workflows. These limitations have contributed to FES being underused in routine rehabilitation.

Recent developments in wearable technologies and Artificial Intelligence (AI) offer an opportunity to overcome these challenges by automating key elements of FES therapy. NeuroSkin® (Kurage, France) is a novel textile-based FES system that integrates embedded dry electrodes, real-time gait analysis using inertial and force sensors, and AI-driven stimulation timing. Unlike traditional FES systems, NeuroSkin® does not require manual electrode placement or parameter tuning, and can deliver multi-muscle, phase-specific stimulation with minimal therapist input.

The aim of this retrospective multicenter feasibility study was to evaluate the integration of NeuroSkin® into real-world post-stroke rehabilitation settings. It does not provide evidence of efficacy, only feasibility and preliminary effectiveness. We assessed its safety, usability, and potential clinical impact on walking function, as a preliminary step toward larger-scale efficacy trials.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

This multicenter retrospective feasibility study aimed to quantify gait improvements in post-stroke patients undergoing Functional Electrical Stimulation (FES) walking therapy as part of their regular rehabilitation routine. The sessions were performed in seven rehabilitation centers in France, Luxembourg and Italy, with inpatients at the early subacute phase of rehabilitation, under the supervision of the local physiotherapists. Standard walking assessments were conducted before and after FES device usage as part of the usual clinical routine. Each center’s physiotherapist completed the System Usability Scale (SUS) questionnaire [

12] post-program.

Ethics compliance and data collection and analysis were carried out in accordance with the MR004 reference methodology. All patients or legal guardians provided informed consent for treatment and use of anonymized data.

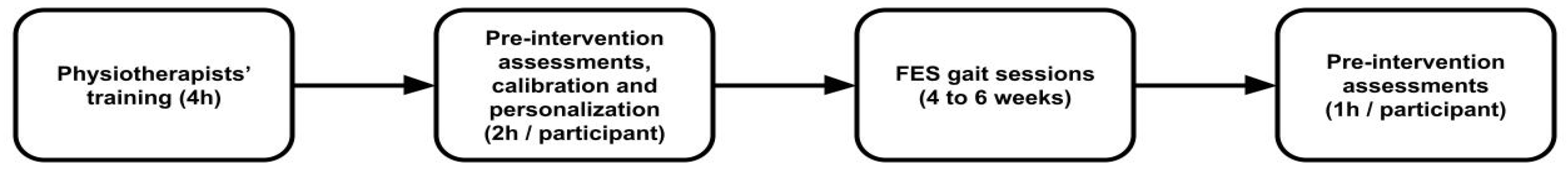

The overall clinical workflow using the NeuroSkin® system is summarized in

Figure 1, from initial training of the physiotherapists to outcome assessment.

First-ever supratentorial ischemic or hemorrhagic stroke;

Subacute stage (≤6 months post-stroke);

Hemiparetic gait requiring assistance with sufficient motor skills to walk with help from a single person or technical aids (0 < NFAC < 5);

Medically stable and able to participate in therapy;

Responsive to FES

Orthopedic or cardiorespiratory contraindications to walking;

Implanted electrical devices;

Cognitive or communication impairments precluding evaluation;

Not responsive to FES.

The intervention consisted of a minimum of 10 FES-gait therapy sessions (maximum: 20; median: 19; standard deviation: 4.27), lasting between 30 to 45 minutes, spread over 6 to 8 weeks, using the NeuroSkin® system. Only the paretic leg was stimulated, and the sessions were supervised by a local physiotherapist.

The physiotherapists received training consisting of a 90-minute course about the basics of FES, followed by a 2h hands-on workshop on how to use the NeuroSkin® system, where they would try the device on themselves. The workshop’s objective was to teach physiotherapists how to adapt the stimulation parameters, especially intensities and timings, in order to help correct specific gait deficits often encountered in post-stroke population, like knee hyperextension, drop foot or equinovarus deformity. Given that the device is designed for single-operator use, each center assigned one therapist, yielding a total of seven therapists across all sites.

Session protocols were not harmonized. Given the wide diversity of post-stroke patients' specificities, the physiotherapists were instructed to tailor the sessions to the needs of the patients, relying on their own expertise. While this introduces inter-site variability, it reflects real-world implementation and reinforces the generalizability of the findings. Physiotherapists were instructed to train the participant at the maximum comfortable intensity, in order to maximize the muscle tone benefits induced by the electrical stimulation; and to look out for specific gait deficits that could be corrected using FES, as trained during the workshop.

2.2. The Neuroskin System

NeuroSkin® is a CE-marked Class IIa medical device. It’s a therapeutic device and real-time gait monitoring platform designed to enhance the walking ability of the user by delivering electrical stimulation to the lower limbs at optimal moments (see

Figure 2). It integrates the following components:

a lower-extremity garment with embedded FES dry electrodes targeting the six following muscle groups: Gluteus Maximus, Quadriceps, Hamstrings, Tibialis Anterior, Fibularis, and Gastrocnemius;

a set of sensors: 7 Inertial Measurement Units (IMU) placed on the pelvis, upper and lower leg segments, and feet; 8 Ground Reaction Force (GRF) sensors integrated into the insoles of the shoes;

an AI-driven real-time gait phase detector incorporated into a microcomputer positioned on the back of a vest worn by the patient;

a MotiMove (3F-Fit Fabricando Faber, Belgrade, Serbia) electrical stimulator [

13];

an application allowing therapists to manage individual patient profiles, including stimulation parameters;

a remote controller used to regulate the overall intensity of stimulation during the sessions.

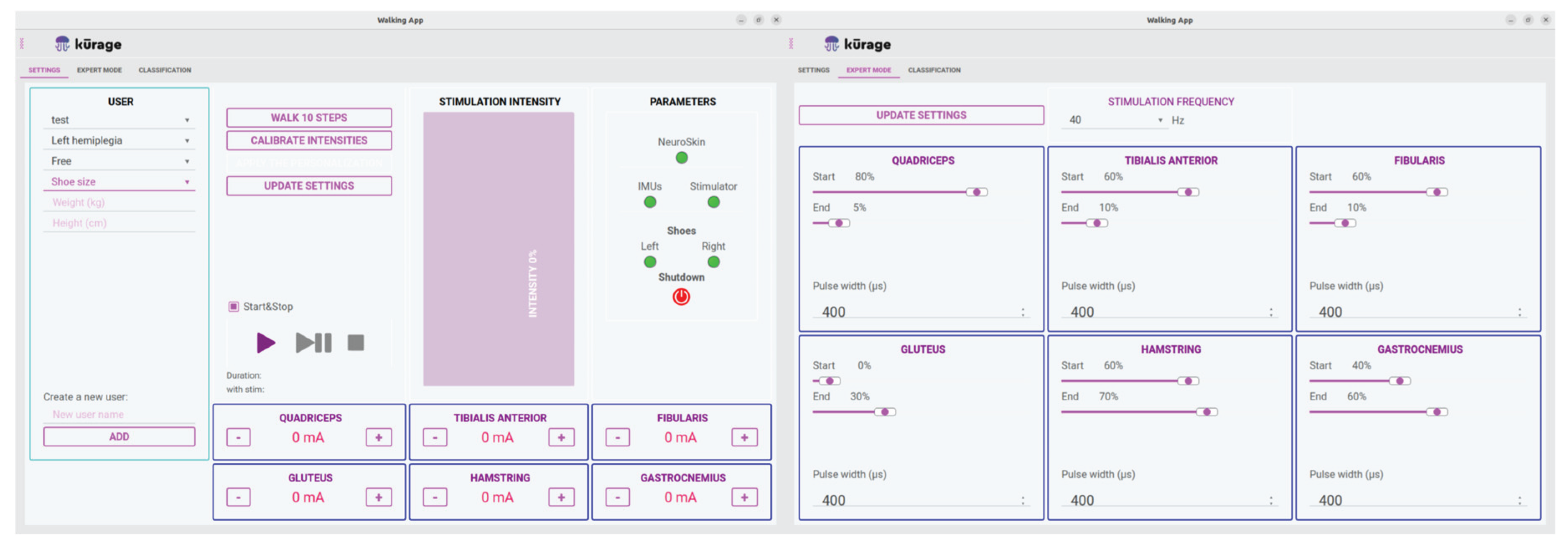

The NeuroSkin® hardware is controlled through a tablet application featuring two main screens: the Global Settings screen and the Expert Settings screen, as displayed in

Figure 3. The Global Settings screen allows the operator to oversee multiple patient profiles, including demographic information, paretic side and maximum allowed intensities for each muscle group. Additionally, it facilitates monitoring of hardware connections and controls session initiation, pause, and termination. The Expert Settings screen provides access to more advanced parameters, such as global frequency for all channels, as well as pulse widths and timings (as a percentage of the gait cycle), for each channel.

NeuroSkin The data incoming from the sensors is processed in real time to determine a gait percentage used to trigger electrical pulses based on pre-defined rules tailored to the patient’s gait pattern classification [

14]. A general gait model, based on deep learning over a database of 32 healthy and post-stroke hemiplegic walking patterns, is refined following an additional personalization phase, involving the patient walking 20 steps without stimulation. The next section provides more details about the AI model and personalization process.

Before starting the first session, both personalization and calibration procedures had to be performed. Personalization involved using gait data from the patient walking approximately 20 steps without stimulation to partially retrain the model with the individual's specific gait pattern, to improve the accuracy of gait phase classification for stimulation control. Calibration consisted of determining the maximum stimulation intensity tolerable by the patient for each muscle. The system was then configured to prevent stimulation beyond these maximum values. These intensity limits could later be adjusted during any session, depending on the patient’s needs—for example, to compensate for habituation or fatigue.

These two procedures were only required before the first session and did not need to be repeated throughout the rest of the intervention. However, they could be repeated if the therapist deemed it necessary to account for substantial progress in the patient’s walking ability.

2.3. AI Model and Personalization Procedure

The gait phase estimation algorithm embedded in the NeuroSkin® system is based on a deep neural network architecture comprising successive 1D convolutional layers with residual connections [

15]. It processes 500 ms windows of real-time gyroscope signals from inertial measurement units (IMUs), to predict the continuous gait phase as a percentage of the stride cycle. The model was trained on a database of gait recordings from 10 healthy and 22 post-stroke hemiparetic individuals. The model outputs the gait phase as a sine-cosine pair representing the phase angle within the gait cycle. Accuracy is measured using the mean squared error (MSE) between predicted and reference values.

To adapt the model to individual patients, a transfer learning procedure is employed. After an initial recording of approximately 20 steps, only the final fully connected layer is retrained using the patient-specific data, while the feature extraction layers remain fixed. This approach strikes a balance between generalization and patient-specific adaptation, allowing the model to capture unique gait features such as asymmetry, low speed, variable terrain adaptation, or fatigue. The personalized model is then compressed and deployed for real-time use.

3. Results

Fifteen patients (average age 60.60 ± 12.65; ⅓ female and ⅔ male) were included in the study across seven centers. The average time since stroke was 61.67 ± 28.92 days.

Table 1 summarizes their baseline demographic and clinical characteristics.

The following clinical outcomes were assessed at baseline and after the intervention: 10MWT, 6MWT, TUG, and NFAC. The values of pre- and post-intervention outcomes were investigated for statistical analysis. To confirm the assumption of normality, the Shapiro-Wilk test was applied to the distribution of the difference vectors for corresponding parameters in the tests performed before and after the intervention. If the p-value was greater than 0.05 (indicating normality), the two-tailed paired t-test (parametric) was employed to identify any differences. Otherwise, the Wilcoxon signed-rank test (non-parametric) was applied. The p-values and d-values (Cohen’s d) were used to indicate the significance and effect size of parametric tests, respectively. For non-parametric tests, the p-values and r-values (Z-score divided by the square root of the sample size) were used for the same purposes. In this study, a p-value lower than 0.05 indicates statistical significance. Normality and significance are summarized in Table 34. All outcome measures showed statistically significant improvements, as displayed in

Table 2.

Physiotherapists also completed the SUS questionnaire post-program, as reported in Table 3. The mean SUS score was 84.6, indicating excellent usability. No adverse events or device-related complications were reported.

Table 3

| Operator |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

AVG |

| SUS |

87.5 |

90 |

90 |

82.5 |

90 |

62.5 |

90 |

84.6 |

4. Discussion

This feasibility study demonstrates that NeuroSkin® can be safely and effectively deployed in routine clinical settings without disrupting workflow. Patients exhibited improvements in gait speed, endurance, balance, and ambulation category, and therapists rated the system as highly usable. These findings align with prior work supporting FES for post-stroke mobility recovery [

6,

16]. This integration of AI-driven automation with therapist-guided clinical care demonstrates the potential for neurotechnology to scale safely and meaningfully into routine practice.

Unlike traditional FES systems, NeuroSkin® automates key configuration steps, potentially facilitating broader clinical implementation. The AI-controlled, phase-specific stimulation closely mimics physiological muscle recruitment patterns [

6,

7]. Since the study spans France, Luxembourg, and Italy, this diversity supports cross-cultural clinical feasibility, increasing external validity.

Limitations include the retrospective nature of the study, lack of a control group, and inter-site protocol variability. Nonetheless, the consistency of results across centers strengthens their clinical relevance and supports future trials. These results provide a foundation for designing prospective, multicenter randomized controlled trials, with harmonized protocols and long-term follow-up, to confirm efficacy and guide implementation strategies.

5. Conclusions

NeuroSkin® is a clinically feasible and well-tolerated wearable FES system that was associated with improved gait performance in subacute post-stroke patients when used in real-world clinical settings. These findings warrant further investigation in prospective controlled trials to confirm efficacy and implementation strategies.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: A.M., L.P-M., J.D.M.; investigation: A.M., J.D.M.; methodology: P.S.; data curation & formal analysis: A.M.; writing—original draft preparation: A.M.; writing—review and editing: L.P-M., P.S., J.D.M.; supervision: A.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was partially supported by the Serbian Ministry of Science and Research under the contract number 451-03-136/2025-03/200175.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Authorization to use the data was obtained from the National Commission for Data Protection and Privacy (CNIL: 22451530, MR-004). Ethics compliance and data collection and analysis were carried out in accordance with the MR004 reference methodology.

Informed Consent Statement

All patients or legal guardians provided informed consent for treatment and use of anonymized data.

Data Availability Statement

All the data has been provided in the article.

Acknowledgments

Louise Vergnes-Blanquer: data collection, on-site assistance; Baptiste Moreau: Designed the NeuroSkin® AI algorithm and software; Romaric Nollot: Designed the NeuroSkin® hardware and embedded systems; Nicolas Feppon: Conducted testing and debugging of the NeuroSkin® hardware and software, provided on-site assistance; The physiotherapists and participants at: SMR Marguerite BOUCICAUT, SMR Val Rosay, SMR Domaine Saint Alban, Hôpital Rothschild AP-HP, Centre National de Rééducation Fonctionnelle et de Réadaptation Rehazenter, CRF l’Espoir, ICS Maugeri.

Conflicts of Interest

Amine Metani, Lana Popović-Maneski and Perrine Seguin are employed by the company Kurage, which manufacture and commercializes the Neuroskin® device.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AI |

Artificial Intelligence |

| CE |

Conformité Européenne (European Conformity) |

| CNIL |

Commission Nationale de l’Informatique et des Libertés (N ational Commission on Informatics and Liberty) |

| CNN |

Convolutional Neural Network |

| d |

Cohen’s d (effect size measure |

| FES |

Functional Electrical Stimulation |

| GRF |

Ground Reaction Force |

| IMU |

Inertial Measurment Unit |

| MSE |

Mean Squared Error |

| NFAC |

New Functional Ambulation Classification |

| SUS |

System Usability Scale |

| TUG |

Timed Up and Go test |

| 6MWT |

6-Minute Walk Test |

| 10MWT |

10-Meter Walk Test |

References

- Feigin, Valery L., et al. “World Stroke Organization (WSO): Global Stroke Fact Sheet 2022.” International Journal of Stroke, vol. 17, no. 1, Jan. 2022, pp. 18–29. DOI.org (Crossref). [CrossRef]

- Dobkin, Bruce H. “Rehabilitation after Stroke.” New England Journal of Medicine, vol. 352, no. 16, Apr. 2005, pp. 1677–84. DOI.org (Crossref). [CrossRef]

- Popović, Dejan B., and Lana Popović-Maneski. “Neuroprosthesis and Functional Electrical Stimulation (Peripheral).” Handbook of Neuroengineering, Springer, Singapore, 2022, pp. 1–40. link.springer.com. [CrossRef]

- Bogataj, Uroš, et al. “Restoration of Gait During Two to Three Weeks of Therapy with Multichannel Electrical Stimulation.” Physical Therapy, vol. 69, no. 5, May 1989, pp. 319–27. DOI.org (Crossref), 19 May. [CrossRef]

- Kralj, A. and Grobelnik, S. (1973). Functional electrical stimulation of paraplegic patients-a feasibility study. Bul. Pros. Res., BPR 10-2O, Fall 1973, 75-102.

- Sheffler, Lynne R., and John Chae. “Neuromuscular Electrical Stimulation in Neurorehabilitation.” Muscle & Nerve, vol. 35, no. 5, May 2007, pp. 562–90. DOI.org (Crossref). [CrossRef]

- De Kroon, J. R. , et al. “Therapeutic Electrical Stimulation to Improve Motor Control and Functional Abilities of the Upper Extremity after Stroke: A Systematic Review.” Clinical Rehabilitation, vol. 16, no. 4, Jun. 2002, pp. 350–60. DOI.org (Crossref). [CrossRef]

- Pomeroy, Valerie M., et al. “Electrostimulation for Promoting Recovery of Movement or Functional Ability after Stroke.” Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, edited by Cochrane Stroke Group, Apr. 2006. DOI.org (Crossref). [CrossRef]

- Stanič U, Trnkoczy A, Kljajić M, Bajd T. Optimal stimulating sequences to normalize hemiplegic's gait. In 3rd Conference on Bioengineering, Budapest 1974.

- Stanič U, Acimović-Janezic R, Gros N, Trnkoczy A, Bajd T, Kljajić M. Multichannel electrical stimulation for correction of hemiplegic gait. Methodology and preliminary results. Scand J Rehabil Med. 1978;10(2):75-92. [PubMed]

- Chaplin, E. Functional neuromuscular stimulation for mobility in people with spinal cord injuries. The Parastep I System. J Spinal Cord Med. 1996 Apr;19(2):99-105. [PubMed]

- Brooke, J. (1996). SUS—A Quick and Dirty Usability Scale. In P. W. Jordan, B. Thomas, B. A. Weerdmeester, & I. L. McClelland (Eds.), Usability Evaluation in Industry (pp. 189-194). London: Taylor & Francis.

- Popović-Maneski, Lana, and Sébastien Mateo. “MotiMove: Multi-purpose Transcutaneous Functional Electrical Stimulator.” Artificial Organs, vol. 46, no. 10, Oct. 2022, pp. 1970–79. DOI.org (Crossref). [CrossRef]

- Chantraine, Frédéric, et al. “Proposition of a Classification of Adult Patients with Hemiparesis in Chronic Phase.” PLOS ONE, edited by Randy D Trumbower, vol. 11, no. 6, Jun. 2016, p. e0156726. DOI.org (Crossref). [CrossRef]

- Kang, Inseung, et al. “Real-Time Gait Phase Estimation for Robotic Hip Exoskeleton Control During Multimodal Locomotion.” IEEE Robotics and Automation Letters, vol. 6, no. 2, Apr. 2021, pp. 3491–97. DOI.org (Crossref). [CrossRef]

- Kottink, Anke I. R., et al. “The Orthotic Effect of Functional Electrical Stimulation on the Improvement of Walking in Stroke Patients with a Dropped Foot: A Systematic Review.” Artificial Organs, vol. 28, no. 6, Jun. 2004, pp. 577–86. DOI.org (Crossref). [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).