Submitted:

25 July 2025

Posted:

28 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- −

- Temporal-Enhanced DANN Framework: We introduce a novel architecture that combines DANN with bidirectional LSTM layers to effectively model temporal dependencies in time-series data, enhancing domain alignment.

- −

- Improved Fault Diagnosis Performance: The proposed approach achieves a real-world test accuracy of 86.67%, significantly reducing the sim-to-real gap compared to the baseline DANN and other deep learning models.

- −

- Enhanced Generalization: The model demonstrates improved F1 scores across fault categories, particularly for the healthy state, addressing a key limitation of prior methods.

- −

- Severity Prediction: By incorporating severity prediction, the framework provides a comprehensive solution for fault diagnosis, enabling prioritized maintenance strategies.

2. Related Works

2.1. Digital Twins for Fault Diagnosis

2.2. Domain Adaptation for Fault Diagnosis

2.3. Temporal Modeling in Related Domains

3. Methodology

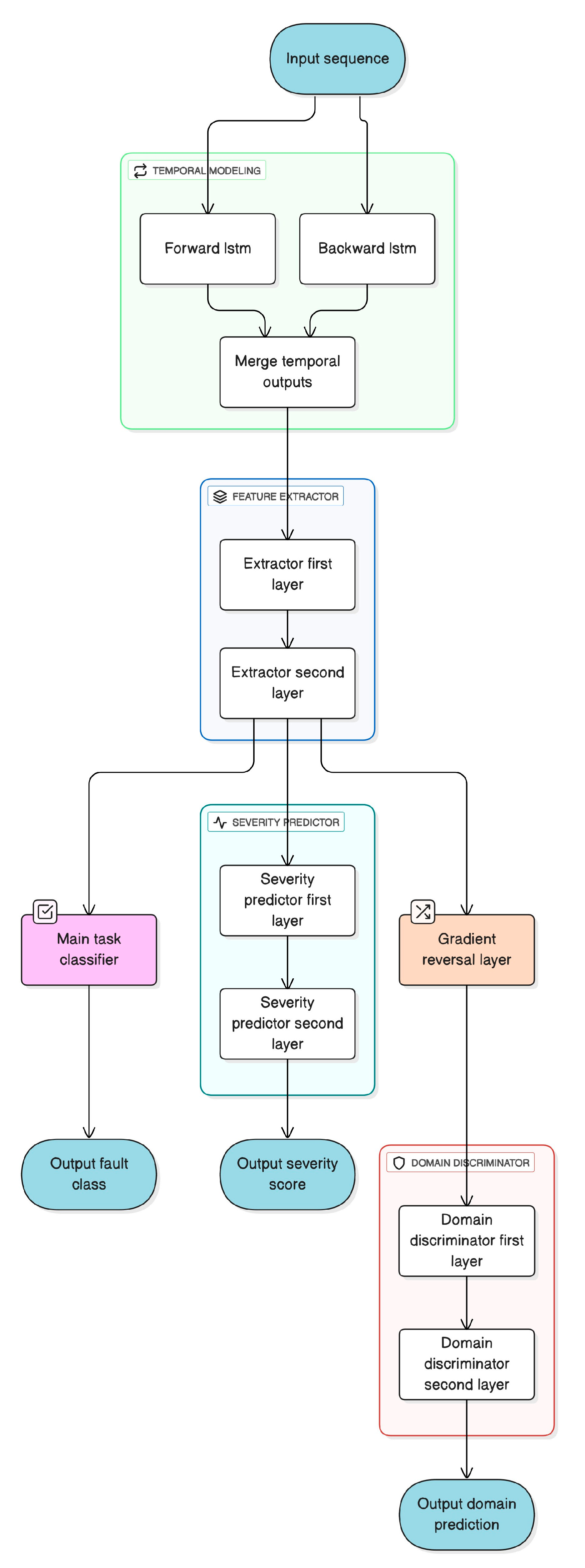

3.1. Proposed Framework: TemporalTwinNet (TTN)

3.2. Framework Overview

3.3. Mathematical Formulation

3.3.1. Feature Extraction with Bidirectional LSTM

3.3.2. Domain Adaptation

3.3.3. Multi-Task Output Layer

3.4. Novelty of the Proposed Framework

- −

- Temporal Modeling with Bidirectional LSTM: Unlike the convolutional feature extractor in traditional DANN, the integration of bidirectional LSTM captures both forward and backward temporal dependencies in time-series data. This is particularly effective for robotics applications where trajectory and residual data exhibit sequential patterns, addressing a gap in prior domain adaptation models that overlook temporal dynamics.

- −

- Multi-Task Learning for Fault Diagnosis: The simultaneous optimization of fault classification and severity prediction through a multi-task output layer enhances the feature extractor’s ability to learn domain-invariant representations that are robust across tasks. This dual-objective approach, absent in single-task DANN frameworks, improves generalization and provides actionable insights for maintenance prioritization

- −

- Adaptive Domain Adaptation: The dynamic adjustment of the domain adaptation weight α based on training progress ensures a balanced alignment of source and target domains, adapting to the model’s learning stage. This refinement over the static weighting in [12] optimizes the adversarial training process for robotics digital twin data.

3.5. Dataset

- −

- Source Domain (Simulated Data): Comprises 3,600 samples representing 9 classes (1 healthy state and 8 fault modes). Each sample has 1,000 time steps with 6 features: desired trajectory coordinates (x, y, z) and residuals. The data is split into 90% training (3,240 samples) and 10% validation (360 samples).

- −

- Target Domain (Real-World Data): Consists of 90 samples collected from a physical robot, used exclusively as the test set.

3.6. Model Architecture: TTN

- −

- Temporal Modeling Layer: A bidirectional LSTM with 2 layers, 64 hidden units, input size 6, and dropout 0.2. Output size: 128.

- −

- Feature Extractor (Gf ): Two fully connected layers with hidden size 128 and ReLU activation.

- −

- Main Task Classifier (Gy): A linear layer predicting one of 9 fault classes.

- −

- Severity Predictor: Two fully connected layers (hidden size 32, output 1) for regression.

- −

- Domain Discriminator (Gd): Two fully connected layers (hidden size 64, output 2) for domain classification.

- −

- Gradient Reversal Layer (GRL): Positioned between Gf and Gd, with gradient scaling factor −λ.

3.7. Training Procedure

3.8. Optimization Objective

3.9. Evaluation Metrics

3.10. Implementation Details

- −

- Data normalized with mean and std; residuals computed for severity.

- −

- Evaluations conducted separately for source and target domains.

- −

- Computation: NVIDIA DGX A100 Station.

4. Results & Discussion

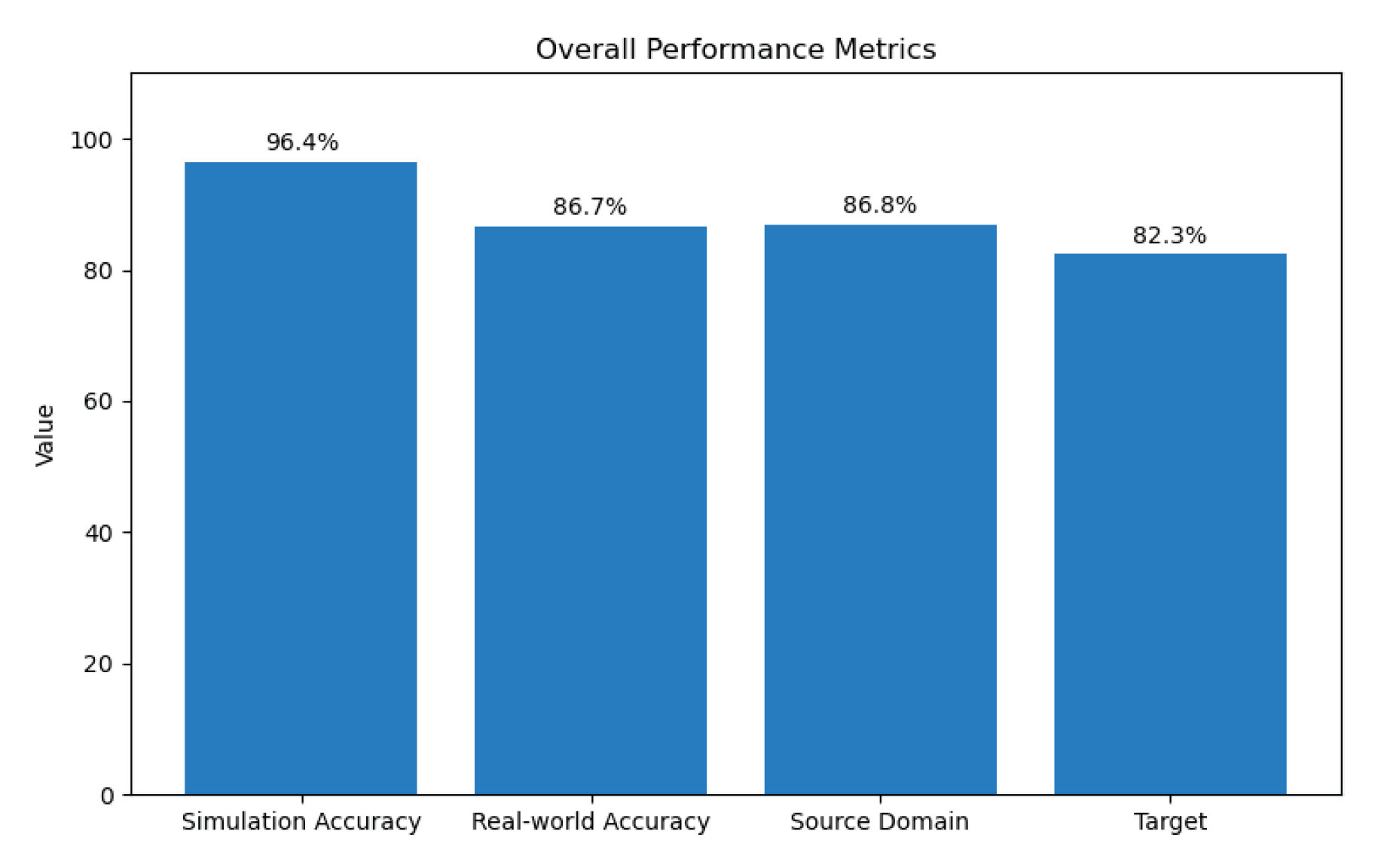

4.1. Quantitative Results

4.1.1. Performance Metrics

- −

- Overall Accuracy: 96.11% ± 0.45%

- −

- F1 Scores: Range from 0.89 (Motor_4_Stuck) to 1.00 (Healthy), with most categories exceeding 0.93 (Table 4).

- −

- Severity Prediction: MSE loss of 0.0641 ± 0.008.

- −

- Real Test Set:

- −

- Overall Accuracy: 86.67% ± 0.62%

- −

- F1 Scores: Range from 0.63 (Healthy) to 1.00 (Motor_1_Stuck), with most categories exceeding 0.85 (Table 4).

- −

- Severity Prediction: MSE loss of 0.0944 ± 0.012.

- −

- Training Dynamics:

- −

- Train Loss: 0.0009 ± 0.0001

- −

- Source Domain Loss: 0.6933 ± 0.015

- −

- Target Domain Loss: 0.6932 ± 0.014

- −

- Source Domain Accuracy: 86.8% ± 1.2%

- −

- Target Domain Accuracy: 82.3% ± 1.5%

- −

- Train Severity Loss: 0.0187 ± 0.003

4.1.2. Comparison with Baselines and State-of-the-Art Methods

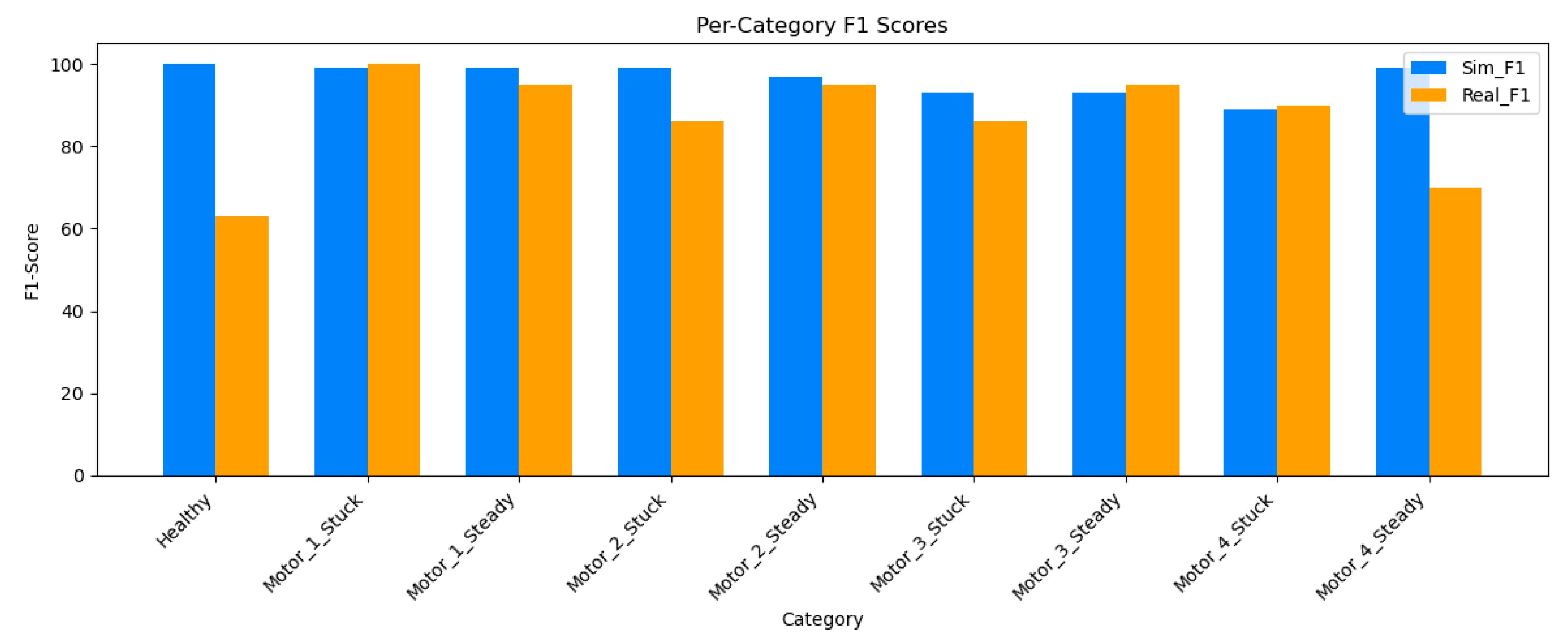

4.1.3. Per-Category Performance

4.1.4. Severity Prediction

4.2. Qualitative Analysis

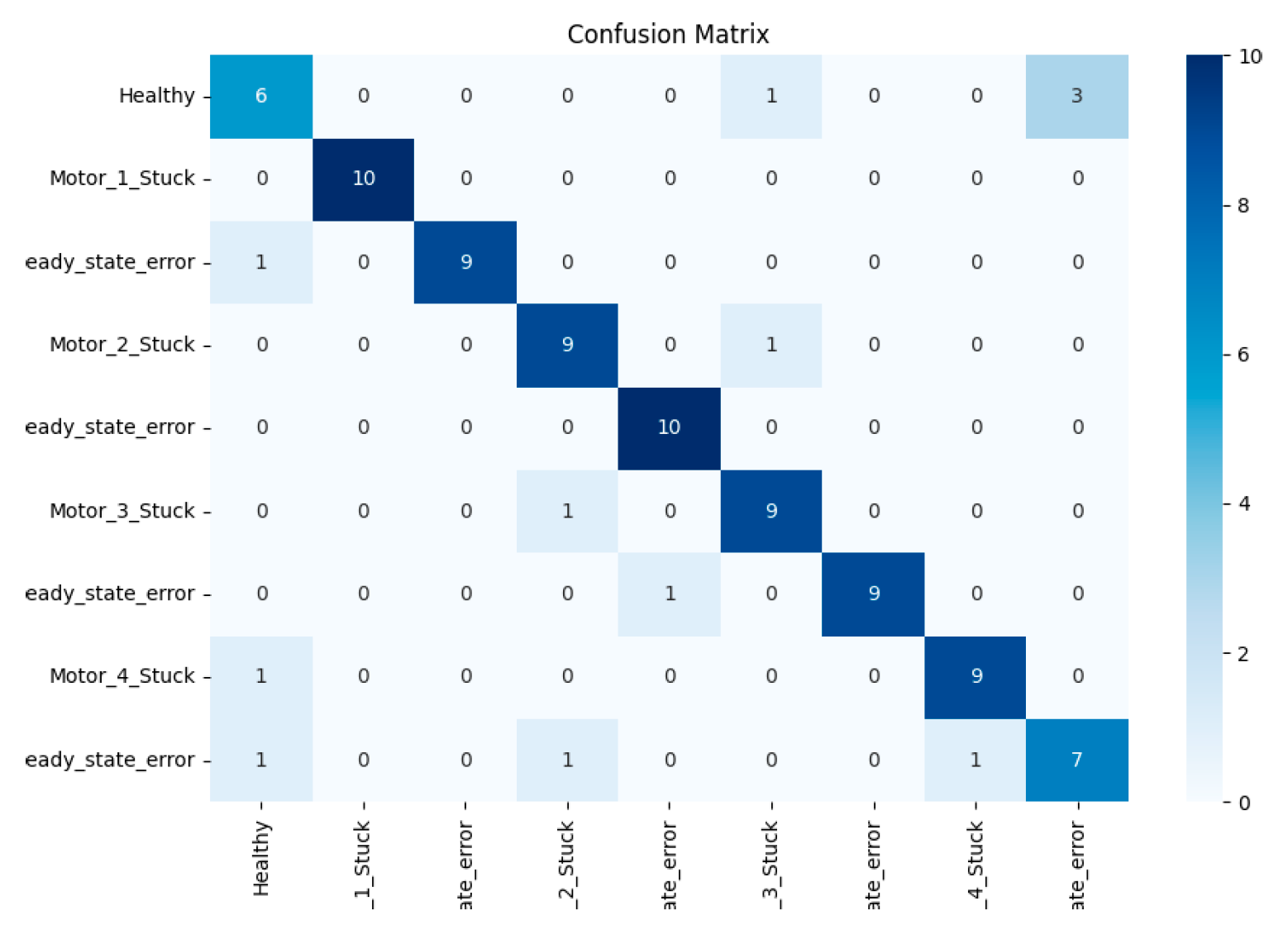

4.2.1. Confusion Matrix for Real Test Set

4.2.2. F1 Score Comparison (Simulation vs. Real)

4.3. Training Dynamics and Convergence Behavior

- 1)

- Classification Loss

- 2)

- Accuracy Trend

- 3)

- Severity Loss

- 4)

- Convergence Speed and Stability

- 5)

- Convergence Speed and Stability

- −

- The model converges quickly.

- −

- Accuracy and loss curves are smooth and stable, especially for training and real test sets.

- −

- Domain adaptation losses (source and target) stabilize early and are well-behaved.

- −

- Second Set (250 Epochs):

- −

- Although training accuracy continues to improve marginally, the domain accuracy (source/target) becomes unstable after ∼150 epochs.

- −

- This suggests overfitting or mode collapse in the domain classifier.

- −

- There is little gain in real test accuracy beyond 100 epochs.

- 6)

- Domain Adaptation Behavior

- −

- After 100-epochs, domain classifier losses (source and target) remain balanced, indicating strong domain-invariant feature learning.

- −

- After 250-epochs, both the source and target domain accuracies fluctuate severely after 150 epochs. This suggests:

- −

- The domain discriminator might be overfitting to one domain (likely the source).

- −

- The adversarial training (via GRL) starts to degrade due to prolonged training.

- 7)

- Severity Prediction

- −

- Across both plots, the severity loss (MSE) for simulated and real test sets stabilizes below 0.1, and shows consistent convergence within the first 30 epochs.

- −

- Extending training beyond 100 epochs does not improve severity estimation, confirming that this sub-task converges quickly and remains stable.

4.4. Overall Performance Evaluation

4.5. Analysis

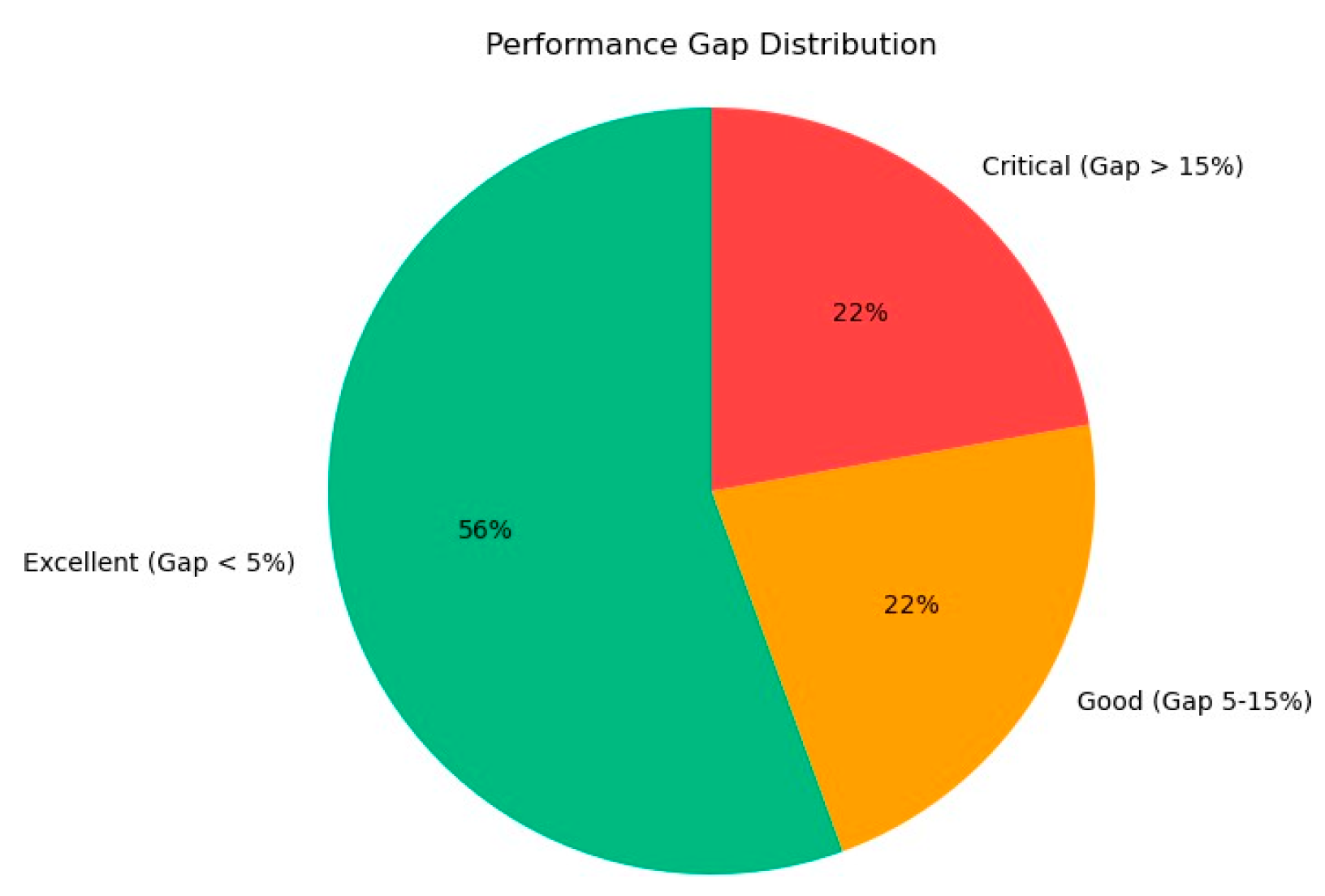

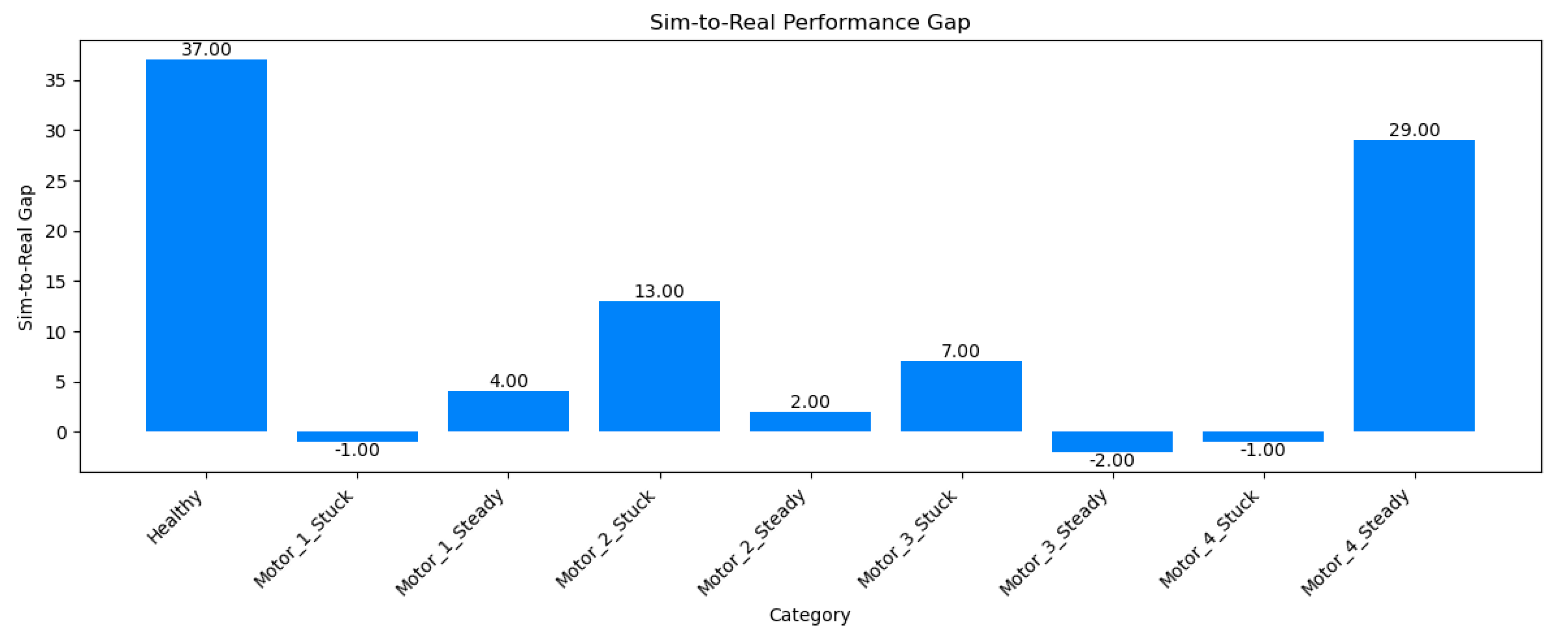

4.5.1. Sim-to-Real Gap

- −

- Temporal Modeling: Bidirectional LSTM captures sequential patterns, aligning simulated and real trajectories effectively.

- −

- Domain Adaptation: Adversarial training ensures domain-invariant features, as seen in the domain adaptation accuracy plot (Figure 6).

- −

- Severity Prediction: Enhances feature robustness, improving generalization.

4.5.2. Key Improvements

- −

- −

- Fault Categories: Most categories achieve F1 scores >0.85, with Motor_1_Stuck reaching 1.00, as confirmed by the confusion matrix (Figure 3).

- −

- Efficiency: Training time (2.52 seconds/epoch) is efficient, with stable convergence (loss curves chart, Figure 5).

- −

- Severity Prediction: Low MSE losses (0.0944 real test) enable accurate fault characterization.

4.5.3. Areas of Concern

- −

- −

- Motor_4_Steady_state_error: A gap of 0.29 indicates challenges in simulation fidelity, also evident in the visualizations.

- −

- Small Real Dataset: The 90-sample real test set limits robustness, necessitating larger datasets for validation.

4.6. Discussion

5. Conclusions and Future Directions

5.1. Conclusions

5.2. Future Directions

- Improving Simulation Fidelity: The significant sim-to-real gaps for the Healthy state and Motor_4_Steady_state_error suggest that the digital twin model requires refinement. Future work should focus on enhancing the simulation’s ability to capture normal operation and complex fault dynamics, potentially by incorporating more realistic noise models [37], environmental variations [38], or advanced physics-based simulations [39]. Techniques like generative adversarial networks (GANs) [40] could be explored to synthesize more representative simulated data.

- Expanding the Real-World Dataset: The limited size of the real-world dataset (90 samples) constrains the model’s generalizability and robustness. Future research should prioritize collecting a larger and more diverse real-world dataset [41], covering a broader range of operating conditions and fault severities. This would enable more comprehensive training and evaluation, potentially reducing the sim-to-real gap further and improving performance on challenging categories.

- Advanced Temporal Modeling: While the bidirectional LSTM improved temporal modeling, categories like Motor_4_Steady_state_error showed slower convergence, as seen in the per-category accuracy trends chart. Future work could explore alternative architectures, such as attention mechanisms or temporal transformers [42], to better capture long-range dependencies and complex temporal patterns in time-series data [43]. These approaches may enhance the model’s ability to generalize across domains.

- Multi-Modal Data Integration: The current framework relies solely on trajectory and residual data. Integrating multi-modal data [44], such as vibration signals, thermal imaging, or acoustic data, could provide a more holistic view of the robot’s health, potentially improving fault diagnosis accuracy and severity prediction [45]. This would require extending the TTN to handle heterogeneous data sources, possibly through multi-branch architectures.

- Explainability and Interpretability: While the qualitative charts provide insights into the model’s behavior, future work should incorporate explainability techniques, such as SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) [46] or attention visualization [47], to better understand the features driving the model’s predictions. This would enhance trust in the system, particularly for safety-critical applications like robotics fault diagnosis.

6. Declarations

- Ethics approval: N/A

- Consent for Publishing: YES

- Availability of data: N/A

Funding

Acknowledgements

Conflict of Interest

References

- Ameer H Sabry and Ungku Anisa Bte Ungku Amirulddin. A review on fault detection and diagnosis of industrial robots and multi- axis machines. Results in Engineering, page 102397, 2024.

- Md Muzakkir Quamar and Ali Nasir. Review on fault diagnosis and fault-tolerant control scheme for robotic manipulators: Recent advances in ai, machine learning, and digital twin. arXiv preprint arXiv:2402.02980, 2024. arXiv:2402.02980, 2024.

- Yuvin Chinniah. Analysis and prevention of serious and fatal accidents related to moving parts of machinery. Safety science, 75:163–173, 2015.

- Denis Leite, Emmanuel Andrade, Diego Rativa, and Alexandre MA Maciel. Fault detection and diagnosis in industry 4.0: A review on challenges and opportunities. Sensors (Basel, Switzerland), 25(1):60, 2024.

- Cheng Qian, Xing Liu, Colin Ripley, Mian Qian, Fan Liang, and Wei Yu. Digital twin—cyber replica of physical things: Architecture, applications and future research directions. Future Internet, 14(2), 2022.

- Zhikun Wang and Shiyu Zhao. Sim-to- real transfer in reinforcement learning for maneuver control of a variable-pitch mav. IEEE Transactions on Industrial Electronics, 2025.

- Cheng Qian, Xing Liu, Colin Ripley, Mian Qian, Fan Liang, and Wei Yu. Digital twin—cyber replica of physical things: Architecture, applications and future research directions. Future Internet, 14(2):64, 2022.

- Jinjiang Wang, Lunkuan Ye, Robert X Gao, Chen Li, and Laibin Zhang. Digital twin for rotating machinery fault diagnosis in smart manufacturing. International Journal of Production Research, 57(12):3920–3934, 2019.

- Chao Yang, Baoping Cai, Qibing Wu, Chenyushu Wang, Weifeng Ge, Zhiming Hu, Wei Zhu, Lei Zhang, and Longting Wang. Digital twin-driven fault diagnosis method for composite faults by combining virtual and real data. Journal of Industrial Information Integration, 33:100469, 2023.

- Tianwen Zhu, Yongyi Ran, Xin Zhou, and Yonggang Wen. A survey of predictive maintenance: Systems, purposes and approaches. arXiv preprint arXiv:1912.07383, 2019.

- Killian Mc Court, Xavier Mc Court, Shijia Du, and Zhiguo Zeng. Use digital twins to support fault diagnosis from system-level condition- monitoring data. In 2025 IEEE 22nd International Multi-Conference on Systems, Signals & Devices (SSD), pages 1064–1069. IEEE, 2025.

- Zhenling Chen, Haiwei Fu, and Zhiguo Zeng. A domain adaptation neural network for digital twin-supported fault diagnosis. arXiv preprint arXiv:2505.21046, 2025.

- Jessy Lauer, Mu Zhou, Shaokai Ye, William Menegas, Steffen Schneider, Tanmay Nath, Mohammed Mostafizur Rahman, Valentina Di Santo, Daniel Soberanes, Guoping Feng, et al. Multi-animal pose estimation, identification and tracking with deeplabcut. Nature Methods, 19(4):496–504, 2022.

- Jinhao Lei, Chao Liu, and Dongxiang Jiang. Fault diagnosis of wind turbine based on long short-term memory networks. Renewable energy, 133:422–432, 2019s.

- Sridevi Kakolu and Muhammad Ashraf Faheem. Autonomous robotics in field operations: A data-driven approach to optimize performance and safety. Iconic Research And Engineering Journals, 7(4):565– 578, 2023.

- Jianbo Yu and Yue Zhang. Challenges and opportunities of deep learning-based process fault detection and diagnosis: a review. Neural Computing and Applications, 35(1):211–252, 2023.

- Mohd Javaid, Abid Haleem, and Rajiv Suman. Digital twin applications toward industry 4.0: A review. Cognitive Robotics, 3:71–92, 2023.

- Zelong Song, Huaitao Shi, Xiaotian Bai, and Guowei Li. Digital twin-assisted fault diagnosis system for robot joints with insufficient data. Journal of Field Robotics, 40(2):258–271, 2023.

- Jared Flowers and Gloria Wiens. A spatio- temporal prediction and planning framework for proactive human–robot collaboration. Journal of Manufacturing Science and Engineering, 145(12):121011, 2023.

- Shuai Ma, Jiewu Leng, Pai Zheng, Zhuyun Chen, Bo Li, Weihua Li, Qiang Liu, and Xin Chen. A digital twin-assisted deep transfer learning method towards intelligent thermal error modeling of electric spindles. Journal of Intelligent Manufacturing, 36(3):1659–1688, 2025.

- an Xu, Yanming Sun, Xiaolong Liu, and Yonghua Zheng. A digital-twin-assisted fault diagnosis using deep transfer learning. Ieee Access, 7:19990–19999, 2019.

- Longchao Da, Justin Turnau, Thirulogasankar Pranav Kutralingam, Alvaro Velasquez, Paulo Shakarian, and Hua Wei. A survey of sim-to-real methods in rl: Progress, prospects and challenges with foundation models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2502.13187, 2025.

- Aidar Shakerimov, Tohid Alizadeh, and Huseyin Atakan Varol. Efficient sim- to-real transfer in reinforcement learning through domain randomization and domain adaptation. IEEE Access, 11:136809–136824, 2023.

- Abhishek Ranjan, Shreenabh Agrawal, Aayush Jain, Pushpak Jagtap, Shishir Kolathaya, et al. Barrier functions inspired reward shaping for reinforcement learning. In 2024 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), pages 10807–10813. IEEE, 2024.

- Yongchao Zhang, JC Ji, Zhaohui Ren, Qing Ni, Fengshou Gu, Ke Feng, Kun Yu, Jian Ge, Zihao Lei, and Zheng Liu. Digital twin- driven partial domain adaptation network for intelligent fault diagnosis of rolling bearing. Reliability Engineering & System Safety, 234:109186, 2023.

- Jisen Li, Dongqi Zhao, Liang Xie, Ze Zhou, Liyan Zhang, and Qihong Chen. Spatial– temporal synchronous fault feature extraction and diagnosis for proton exchange membrane fuel cell systems. Energy Conversion and Management, 315:118771, 2024.

- Bo Yang, Weishan Long, Yucheng Zhang, Zerui Xi, Jian Jiao, and Yufeng Li. Multivariate time series anomaly detection: Missing data handling and feature collaborative analysis in robot joint data. Journal of Manufacturing Systems, 75:132– 149, 2024.

- Pranjal Kumar, Siddhartha Chauhan, and Lalit Kumar Awasthi. Human pose estimation using deep learning: review, methodologies, progress and future research directions. International Journal of Multimedia Information Retrieval, 11(4):489–521, 2022.

- Tao Yang, Yu Cheng, Yaokun Ren, Yujia Lou, Minggu Wei, and Honghui Xin. A deep learning framework for sequence mining with bidirectional lstm and multi-scale attention. arXiv preprint arXiv:2504.15223, 2025.

- Yeqiang Liu, Weiran Li, Xue Liu, Zhenbo Li, and Jun Yue. Deep learning in multiple animal tracking: A survey. Computers and Electronics in Agriculture, 224:109161, 2024.

- Eric Tzeng, Judy Hoffman, Ning Zhang, Kate Saenko, and Trevor Darrell. Deep domain confusion: Maximizing for domain invariance. arXiv preprint arXiv:1412.3474, 2014.

- Eric Tzeng, Judy Hoffman, Kate Saenko, and Trevor Darrell. Adversarial discriminative domain adaptation. In Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, pages 7167–7176, 2017.

- Jun-Yan Zhu, Taesung Park, Phillip Isola, and Alexei A Efros. Unpaired image-to-image translation using cycle-consistent adversarial networks. In Proceedings of the IEEE international conference on computer vision, pages 2223–2232, 2017.

- Mingsheng Long, Zhangjie Cao, Jianmin Wang, and Michael I Jordan. Conditional adversarial domain adaptation. Advances in neural information processing systems, 31, 2018.

- Sinno Jialin Pan, Ivor W Tsang, James T Kwok, and Qiang Yang. Domain adaptation via transfer component analysis. IEEE transactions on neural networks, 22(2):199– 210, 2010.

- Yaroslav Ganin and Victor Lempitsky. Unsupervised domain adaptation by backpropagation. In International conference on machine learning, pages 1180–1189. PMLR, 2015.

- Fabrizio Pancaldi, Luca Dibiase, and Marco Cocconcelli. Impact of noise model on the performance of algorithms for fault diagnosis in rolling bearings. Mechanical Systems and Signal Processing, 188:109975, 2023.

- Xiaofeng Liu, Zheng Zhao, Fan Yang, Fuyuan Liang, and Lin Bo. Environment adaptive deep reinforcement learning for intelligent fault diagnosis. Engineering Applications of Artificial Intelligence, 151:110783, 2025.

- Teemu Mäkiaho, Kari T Koskinen, and Jouko Laitinen. Improving deep learning anomaly diagnostics with a physics-based simulation model. Applied Sciences, 14(2):800, 2024.

- Tongyang Pan, Jinglong Chen, Tianci Zhang, Shen Liu, Shuilong He, and Haixin Lv. Generative adversarial network in mechanical fault diagnosis under small sample: A systematic review on applications and future perspectives. ISA transactions, 128:1–10, 2022.

- Amirmasoud Kiakojouri and Ling Wang. A generalized convolutional neural network model trained on simulated data for fault diagnosis in a wide range of bearing designs. Sensors, 25(8):2378, 2025.

- Haixin Lv, Jinglong Chen, Tongyang Pan, Tianci Zhang, Yong Feng, and Shen Liu. Attention mechanism in intelligent fault diagnosis of machinery: A review of technique and application. Measurement, 199:111594, 2022.

- Cheng Cheng, Xiaoyu Liu, Beitong Zhou, and Ye Yuan. Intelligent fault diagnosis with noisy labels via semisupervised learning on industrial time series. IEEE Transactions on Industrial Informatics, 19(6):7724–7732, 2023.

- Yongchao Zhang, Jinliang Ding, Yongbo Li, Zhaohui Ren, and Ke Feng. Multi-modal data cross-domain fusion network for gearbox fault diagnosis under variable operating conditions. Engineering Applications of Artificial Intelligence, 133:108236, 2024.

- Ali Saeed, Muazzam A. Khan, Usman Akram, Waeal J. Obidallah, Soyiba Jawed, and Awais Ahmad. Deep learning based approaches for intelligent industrial machinery health management and fault diagnosis in resource- constrained environments. Scientific Reports, 15(1):1114, 2025.

- Joseph Cohen, Xun Huan, and Jun Ni. Shapley-based explainable ai for clustering applications in fault diagnosis and prognosis. Journal of Intelligent Manufacturing, pages 1– 16, 2024.

- Yasong Li, Zheng Zhou, Chuang Sun, Xuefeng Chen, and Ruqiang Yan. Variational attention-based interpretable transformer network for rotary machine fault diagnosis. IEEE transactions on neural networks and learning systems, 2022.

| Component | Description |

|---|---|

| Temporal Modeling Feature Extractor (Gf ) Main Task Classifier (Gy ) Severity Predictor Domain Discriminator (Gd) Gradient Reversal Layer |

BiLSTM (2 layers, 64 units, input 6, dropout 0.2) 2 FC layers (input 128, hidden 128, ReLU, dropout) 1 linear layer (output: 9 classes) 2 FC layers (hidden 32, output 1) 2 FC layers (hidden 64, output 2) Reverses gradient for domain adaptation |

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| Learning Rate Batch Size Epochs Optimizer Scheduler Alpha Adjustment |

0.001 32 250 Adam ReduceLROnPlateau (factor=0.1, patience=100) α = 1+ 2 − 1 e−10p |

| Method | Train Acc. (%) | Val. Acc. (%) | Real Test Acc. (%) | Sim-to-Real Gap (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CNN | 99.94 ± 0.05 | 96.78 ± 0.32 | 70.00 ± 1.1 | 29.94 |

| LSTM | 96.06 ± 0.42 | 92.22 ± 0.55 | 56.00 ± 1.3 | 40.06 |

| Transformer | 97.73 ± 0.38 | 75.94 ± 0.71 | 48.44 ± 1.5 | 49.29 |

| TCN | 87.96 ± 0.61 | 67.67 ± 0.82 | 44.22 ± 1.7 | 43.74 |

| DANN [12] | 99.29 ± 0.07 | 95.28 ± 0.39 | 80.22 ± 0.85 | 19.07 |

| DDC [31] | 98.50 ± 0.10 | 94.10 ± 0.45 | 75.33 ± 1.2 | 18.77 |

| ADDA [32] | 99.10 ± 0.08 | 93.85 ± 0.50 | 78.89 ± 0.90 | 14.96 |

| CycleGAN [33] | 98.75 ± 0.12 | 94.50 ± 0.40 | 76.67 ± 1.0 | 17.83 |

| CDAN [34] | 99.15 ± 0.09 | 94.20 ± 0.48 | 79.44 ± 0.95 | 14.76 |

| TCA [35] | 98.20 ± 0.15 | 93.50 ± 0.55 | 72.22 ± 1.3 | 21.28 |

| DANN-GR [36] | 99.35 ± 0.06 | 95.10 ± 0.42 | 81.11 ± 0.88 | 14.99 |

| TemporalTwinNet(TTN) | 99.94±0.04 | 96.11±0.45 | 86.67±0.62 | 9.44 |

| Category | Simulation F1 | Real F1 | Gap |

|---|---|---|---|

| Healthy | 1.00 ± 0.00 | 0.63 ± 0.05 | 0.37 |

| Motor_1_Stuck | 0.99 ± 0.01 | 1.00 ± 0.00 | -0.01 |

| Motor_1_Steady_state_error | 0.99 ± 0.01 | 0.95 ± 0.02 | 0.04 |

| Motor_2_Stuck | 0.99 ± 0.01 | 0.86 ± 0.03 | 0.13 |

| Motor_2_Steady_state_error | 0.97 ± 0.02 | 0.95 ± 0.02 | 0.02 |

| Motor_3_Stuck | 0.93 ± 0.03 | 0.86 ± 0.03 | 0.07 |

| Motor_3_Steady_state_error | 0.93 ± 0.03 | 0.95 ± 0.02 | -0.02 |

| Motor_4_Stuck | 0.89 ± 0.04 | 0.90 ± 0.03 | -0.01 |

| Motor_4_Steady_state_error | 0.99 ± 0.01 | 0.70 ± 0.04 | 0.29 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).