1. Introduction

Salt production has kept pace with the evolution of humanity [

1]. Salt is used in a multitude of applications in people’s daily lives. Among the uses of salt for people, it can be highlighted, for example, in direct use as a condiment in food, or as salts for application on the skin in health and wellness treatments (e.g., [

2,

3]).

In terms of salt production, with the evolution of machinery in the middle of the last century, salt extraction became very mechanized, and the market value of raw material reduced considerably [

4,

5]. This phenomenon has meant that only large producers have been able to persist in the market [

6]. It also happened that smaller landowners who could not remain competitive due to the scale of their production, joined or sold their salt pan areas to larger producers [

7].

However, with the appearance of the valued flower of salt (a.k.a.,

fleur de sel in French or

flor de sal in Portuguese), until then consigned to oblivion, there was a change in the production paradigm [

8]. From that moment on, regeneration of the artisanal salt production sector began, thanks to a new and promising market [

9]. In the meantime, several small producers have reappeared.

Traditional marine salt (TMS) production, particularly prominent in southern European regions, represents more than a climatic advantage for salt crystallization [

10,

11,

12]; it is embedded within a long-standing social–ecological system (SES) [

13,

14]. While environmental conditions—such as high summer temperatures, minimal rainfall, and low atmospheric humidity—create an ideal setting for salt formation, the sustainability of TMS depends equally on the adaptive practices and knowledge systems of salt producers [

15]. These producers draw on generations of local ecological knowledge (LEK) to manage tidal flows, evaporation cycles, and seasonal climate variability [

16]. Their ability to read ecological cues and adjust management practices accordingly—such as optimizing pond preparation and timing the harvest of

fleur de sel—demonstrates a co-evolved relationship between humans and the landscape [

9]. Furthermore, traditional forms of social organization, including informal institutions and cooperative labor arrangements, play a crucial role in regulating access, coordinating maintenance, and preserving collective knowledge. As such, TMS production systems exemplify how cultural practices, ecological processes, and local governance intertwine to maintain a dynamic and resilient coastal land-use tradition [

17].

However, this intricate social–ecological balance is increasingly challenged by shifting land-use dynamics, including coastal development, aquaculture expansion, and abandonment of traditional practices [

14]. Such transformations not only alter the conservation of the physical landscape but also disrupt the institutional memory and ecological feedback that have historically sustained TMS systems [

18].

Understanding traditional salt production through the lens of SES and land-use change allows us to examine how cultural heritage, environmental knowledge, and governance interact under conditions of socio-economic and climatic uncertainty. This perspective is essential for assessing the resilience and adaptive capacity of TMS landscapes in the face of global change [

19]. In the last decade, it has been observed that there has been a growing interest in activities in salt pans associated with tourism, which increases the resilience of the socio-ecological system [

9,

16].

This study aims to assess recent land use and conservation in traditional salt pan areas in mainland Portugal, focusing on signs of ecological regeneration or abandonment. By integrating official statistics, satellite imagery, fieldwork, and literature, the research examines how these coastal landscapes function within broader social-ecological systems.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Saltern Land Use in Portugal

In Portugal, traditional sea salt production has shaped coastal land use across key wetland systems such as the Ria de Aveiro, the Mondego and Tagus estuaries, and the Ria Formosa in the Algarve. While regions like the Sado estuary—once the nation’s leading salt producer—have seen a shift to alternative land uses such as rice cultivation, others are witnessing a partial revival of salt pan landscapes (or saltscapes) [

20,

21,

22,

23,

24].

This regeneration reflects a broader land-use change, as abandoned salt pans are repurposed not only for salt extraction but also for cultural and ecological services, including tourism, habitat provision, and recreation [

6,

25,

26]. The spatial demands of traditional salt production—requiring extensive evaporative ponds—alter land cover yet often restore valuable ecological functions [

27,

28]. These managed environments reestablish food webs (e.g.,

Dunaliella spp.,

Artemia spp., waterfowl), reinforcing the multifunctionality of these anthropogenic but biodiverse saltscapes [

29,

30].

The EU’s commitment and responsibility to reverse biodiversity loss is currently underway. By 2030 there is a commitment to restore at least 1/5 of terrestrial and marine habitats [

31]. By 2050 in Europe, it is supposed to rehabilitate up to 90% of all these marine and terrestrial habitats [

32].

In addition to being scarce, most of the literature on the characterization of salterns is related to waterfowl conservation [

25,

33,

34]. These articles usually refer not only to the abundance and description of the species present, but also to which wetlands are important for nesting, feeding habits or wintering areas [

35]. On the production of other studies of a socio-economic nature, literature is also scarce [

36,

37,

38,

39]

.

2.2. Salt Pans as Social–Ecological Systems

Traditional salt pans represent more than an artisanal or industrial heritage—they are embedded within long-standing SES that have historically shaped coastal and inland landscapes [

40]. Salt production, with its deep historical roots and ecological specificity, embodies both tangible and intangible heritage [

19,

41]. In recent decades, the abandonment or transformation of these systems has reflected broader land-use and land-cover changes, driven by shifts in economic priorities, environmental policies, and urban expansion [

42].

In response to these dynamics, several local and territorial governance entities have initiated regeneration projects that revalue the conservation of the salt pans not only as historical landmarks but also as multifunctional landscapes.

In some areas, these spaces no longer serve extractive purposes but have been reactivated as educational and cultural infrastructure, preserving social memory while reshaping land use [

43]. For instance, the restored salt pans of Junqueira in central Portugal now serve primarily pedagogical roles, highlighting historical techniques and ecological interactions [

44].

Elsewhere, hybrid models emerge. The inland salt pans of Rio Maior—located far from the coast—remain in operation while being recognized as national cultural heritage (by Portuguese Decree Law no. 67/97, DR, I Série-B, no. 301, 31-12-1997), blending historical continuity with adaptive land use [

45]. In coastal regions such as Figueira da Foz, where artisanal salt production has been classified as intangible cultural heritage, regenerated salt pans have become embedded in broader service-based economies, including ecotourism and nature-based recreation [

46]. These transformations exemplify how traditional saltscapes are transitioning into multifunctional SES, shaped by heritage values, ecological processes, and emerging demands for sustainable, culturally embedded tourism.

2.3. Entrepreneurial Innovation and Socio-Ecological Transformation in Salt Pans

After overcoming some barriers, the revalorization of fleur de sel in France during the 1970s catalyzed a broader shift across southern Europe and the Mediterranean, where formerly declining saltscapes began to re-emerge as multifunctional socio-ecological systems [

47,

48,

49,

50,

51,

52]. In Portugal, this transformation took place in the 1990s, driven by renewed global demand for artisanal salt and an appreciation for heritage food products. What was once an undervalued byproduct of coastal saltscapes became a premium commodity, triggering both ecological reinvestment and a restructuring of local economies [

53]. In some cultures fleur de sel has been commonly collected by women [

54].

After the introduction of the wheelbarrow in the 1960s [op cit.], a critical innovation in this transformation was the refinement of techniques to harvest fleur de sel—a fragile salt crust that forms on the water surface of crystallizer ponds. Unlike traditional sea salt, which precipitates on the pond bottom, fleur de sel requires careful manual collection to preserve its structure and purity [

55,

56]. This biophysical specificity has not only shaped harvesting practices but has also reinforced the need for skilled labor, LEK, and careful ecological management of the salt pans.

The higher economic returns from fleur de sel production have repositioned salt producers as entrepreneurs and stewards of niche heritage landscapes [

57]. This economic reconfiguration has also prompted significant land-use changes, as abandoned or underutilized salt pans are reactivated not solely for extraction, but also for cultural and tourism purposes. Responding to the growing demand for nature-based and heritage-driven tourism, a new class of cultural entrepreneurs has emerged, integrating salt production with experiential tourism, education, and wellness services [

58,

59,

60]. These innovations demonstrate how socio-ecological regeneration—rooted in both market dynamics and ecological specificity—can drive the adaptive reuse of coastal and peri-urban saltscapes. In the value chain, there are also some risks and side effects to consider, such as unfavorable weather conditions (which may not only limit production but also delay it), coastal pollution (compromising water and production quality), and difficulties related to production factors (namely human resources) [

61].

2.4. Cultural Tourism as a Driver of Socio–Ecological and Land-Use Transformation in Salt Pans

The renewed attention to salt pans—once primarily sites of extractive labor—now reflects their emerging role within dynamic SES. The production of salt, a substance integral to human health and daily life, is increasingly attracting visitors who seek meaningful experiences tied to traditional landscapes and ecological processes [

62]. The interaction between cultural heritage and ecological distinctiveness has positioned salt pans as appealing destinations for nature-based and heritage-driven tourism.

As tourism infrastructure and visitor services are developed, these saltscapes undergo a subtle yet significant land-use shift—from mono-functional production zones to multifunctional areas offering cultural, recreational, and ecological ecosystem services (ES). This transition is particularly evident where environmental enhancement (e.g., trails, signage, interpretive centers) improves visitor accessibility and comfort, reinforcing the saltscape’s social value and leading to positive feedback loops of use, investment, and conservation [

63].

In response to growing demand, tour operators now include salt pan visits in their portfolios as part of a broader effort to diversify experiential offerings [

64]. Simultaneously, cultural entrepreneurs are investing in these traditionally marginal areas—often located at the urban-rural interface—developing activities such as guided tours, wellness services, and artisanal workshops [

65]. This changing pattern of use illustrates a land-cover transition shaped not only by market forces but also by evolving cultural perceptions of landscape value, identity, and function (

Table 1).

3. Methodology

3.1. Conceptual Framework

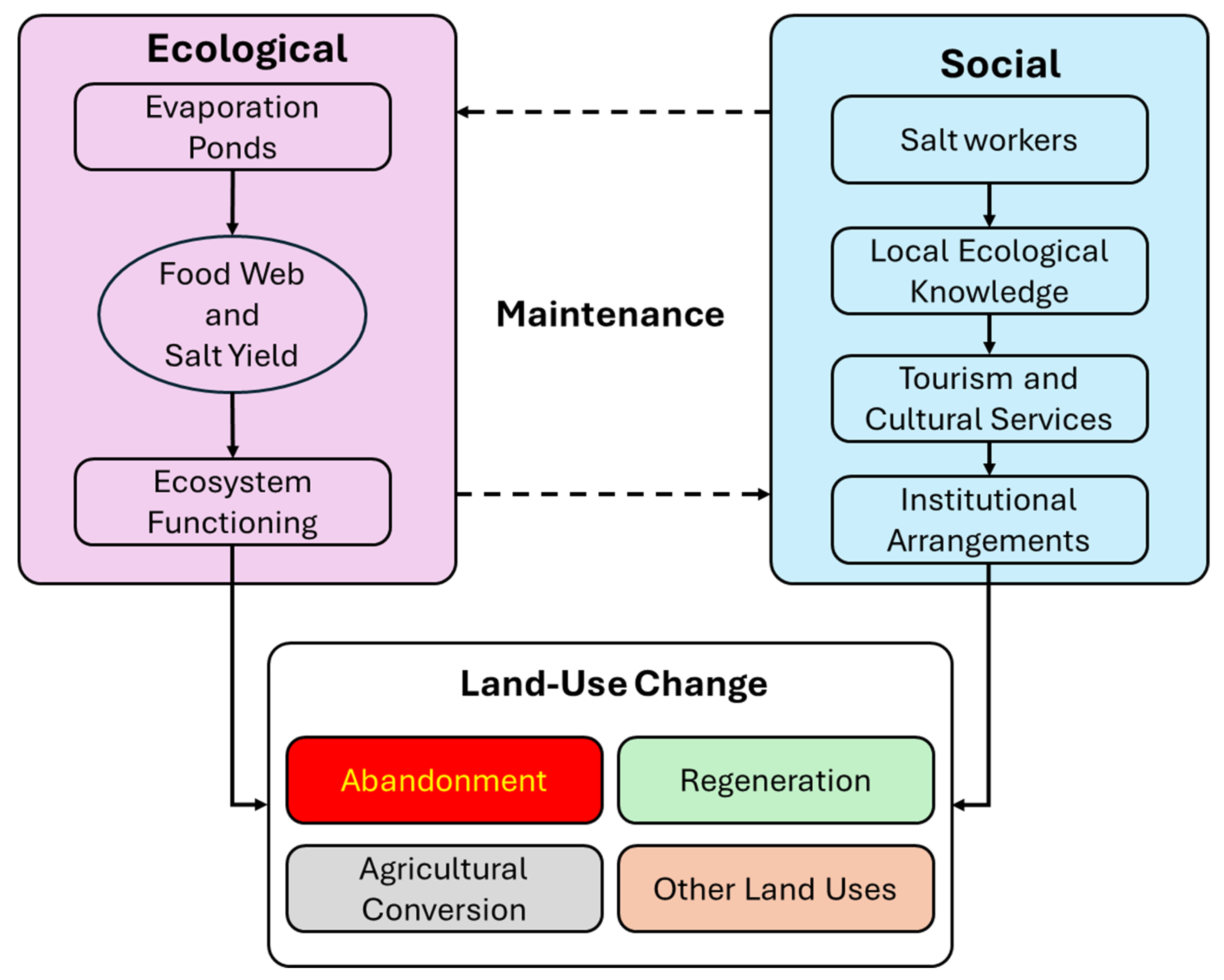

As the purpose of this research is to find out to what extent there is land-use change in traditional salt production sites in Portugal, it is important to identify the steps to be taken in order to obtain reliable data and be able to discern the evolution of these spaces. In this sense, an analysis strategy was developed that consists of a multi-step methodology (

Figure 1).

3.2. Research Question

This study explores whether traditional salt pan areas are experiencing abandonment, regeneration, or transformation, viewed through the lens of social–ecological resilience and land-use dynamics. Rather than focusing solely on production methods, it is assessed how human activities, ecological conditions, and land-use pressures interact to shape the current state of these landscapes.

Briefly, some conditions of the salt pan systems area can be defined. Salt pans maintenance refers to the systematic use of the areas involved for salt production. The repurpose of salt pan areas refers to a more recent economic use other than salt production. The loss of salt pan areas occurs when they become unused and abandoned.

Field observations and literature review inform the seasonal and physical characteristics of salt pan management, particularly the early-season clearing and preparation of crystallizer ponds. This land preparation serves as a proxy for active socio-ecological engagement and land-use continuity [

66]. The central research question asks:

To what extent are traditional salt pan systems being maintained, repurposed, or lost amid shifting social, ecological, and land-cover conditions?

3.3. Data Collection

To assess the transformation of salt pan landscapes within a social–ecological and land-use change framework, this study draws on multiple data sources. Statistical yearbooks serve as a baseline to track the spatial extent, number of active salt pans, and production volumes of traditional sea salt and

fleur de sel across Portuguese regions [

67,

68,

69,

70,

71,

72,

73].

These quantitative records are complemented by qualitative insights from scientific literature and geospatial observations. High-resolution aerial imagery—such as from Google Maps—is used to identify physical signs of abandonment or regeneration (e.g., pond maintenance, infrastructure renewal). These images were identified between April and June 2024, but due to their source, they can be from a few months to about 5 years old and are composite satellite mosaics (i.e., in addition to having temporal discrepancies, they can also come from different satellites). These visual data help assess land-cover status and support analysis of socio-ecological engagement in salt pan landscapes [

74,

75,

76].

3.4. Hypothesis Construction

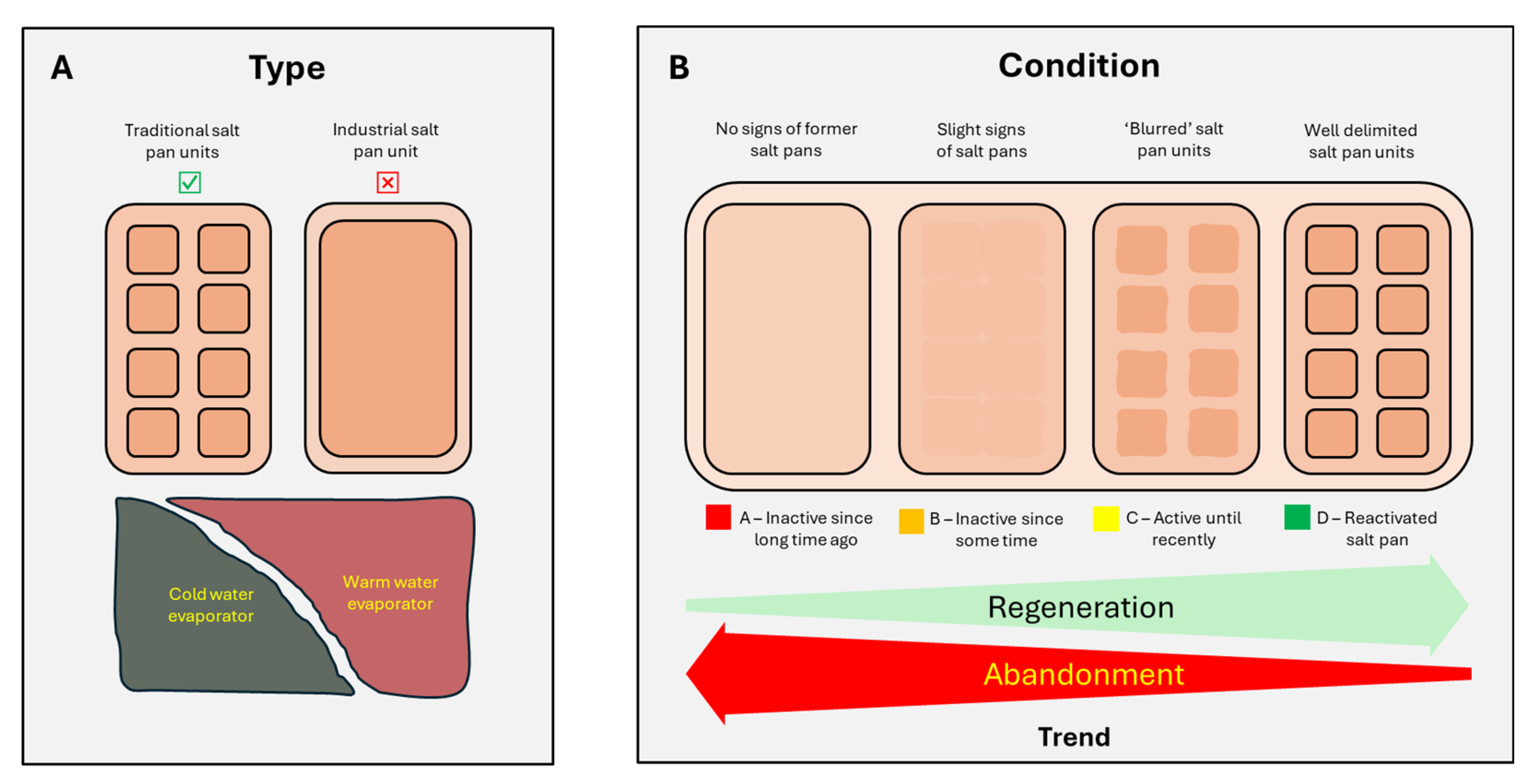

Not all salt production methods are based on evaporation [

12]. However, for processes based on this method, salt pans require pond areas designated by evaporators for the graduation of salt (

Figure 2A). With the research question defined and relevant spatial and statistical data gathered, this study constructs a hypothesis framework to assess the condition of salt pan landscapes as indicators of land-use continuity or decline [

77,

78].

Null hypothesis (H₀): If traditional salt pan landscapes are in decline, aerial evidence will reveal fragmented, deteriorated, or erased salt pan units, indicating abandonment or land-use change.

Alternative hypothesis (Hₐ): If traditional salt pan landscapes are being regenerated as socio-ecological systems, aerial imagery will show well-defined, maintained infrastructure and active land use.

To evaluate these conditions, it is applied a classification scale with four observable states, reflecting the degree of physical integrity and maintenance visible from aerial imagery (

Figure 2B). These categories serve as proxies for socio-ecological activity and land-cover dynamics—ranging from fully active and maintained to entirely degraded or repurposed.

It is worth noting that this categorization was empirical, based solely on satellite imagery and literature and documentary film excerpts. There are no real indicators of degradation, other than the characteristics of the saltscapes mentioned above. Although there is cartography relating to the uses of these areas and official entities that manage them. This study did not involve these entities in the classification, relying solely on the literature and visits to some of these areas.

This framework enables us to spatially analyze the transformation of salt pans not merely as production zones but as dynamic landscapes where heritage, ecological function, and human use intersect or unravel.

3.5. Testing the Hypothesis

To evaluate the spatial dynamics of salt pan regeneration or abandonment, each site associated with traditional salt production was geolocated using satellite imagery (e.g., Google Maps). The physical condition of the salt pan units—based on visible features such as structural delineation, water presence, and maintenance—was used as a proxy for land use activity and socio-ecological engagement.

Each site was categorized along a gradient from active regeneration to visible abandonment. This classification enabled a comparative assessment of land-use change across regions and provided insight into broader socio-ecological trends, such as the loss or revival of ecosystem services, and cultural landscapes.

A simple spatial index was calculated to estimate the proportion of area under each regeneration condition, informing the selection of representative case studies for further analysis. Below is the generic equation to determine the degree of regeneration that should be applied for each site:

Where:

Ai is the area with the degree of regeneration i.

At is the total area.

Pi is the proportion of the total area that has the degree of regeneration

i (expressed as a value between 0 and 1). From

Figure 2 the Condition is according to the following: 0≤A<0.25 (red) , 0.25≤B<0.5 (orange), 0.5≤C<0.75 (yellow) and 0.75≤D<1 (green).

Because there are varying degrees of regeneration, all areas must be added together to ensure that they cover the total area:

3.6. Data Analysis and SES–Saltscape Interpretation

Satellite imagery was analyzed with attention to seasonality and recency, as these factors affect the visibility of land-use features. Salt pan conditions were classified along a regeneration–abandonment continuum, serving as a proxy for social–ecological engagement and land-cover change.

To interpret the images, it was defined that salt pans were considered well-maintained when satellite images showed a clear delineation between production units. Conversely, salt pans with deteriorated structures were defined as those in which the former production units had vaguely defined contours, sometimes even no longer showing any contours. Validation of the interpretation of the satellite images was performed by visiting the sites in midsummer to verify their use (or abandonment) for salt production purposes (which implies the restoration of the salt pans).

These observations were interpreted within the broader SES context—highlighting links between land-use activity, habitat condition, and sustainable management practices. The analysis informs whether salt pan landscapes are undergoing ecological revitalization or socio-economic decline, and whether these trends signal resilience, transitions, or opportunities (e.g., eco-tourism, habitat restoration).

4. Results

4.1. Trends in Salt Pan Dynamics and Land Use Transitions

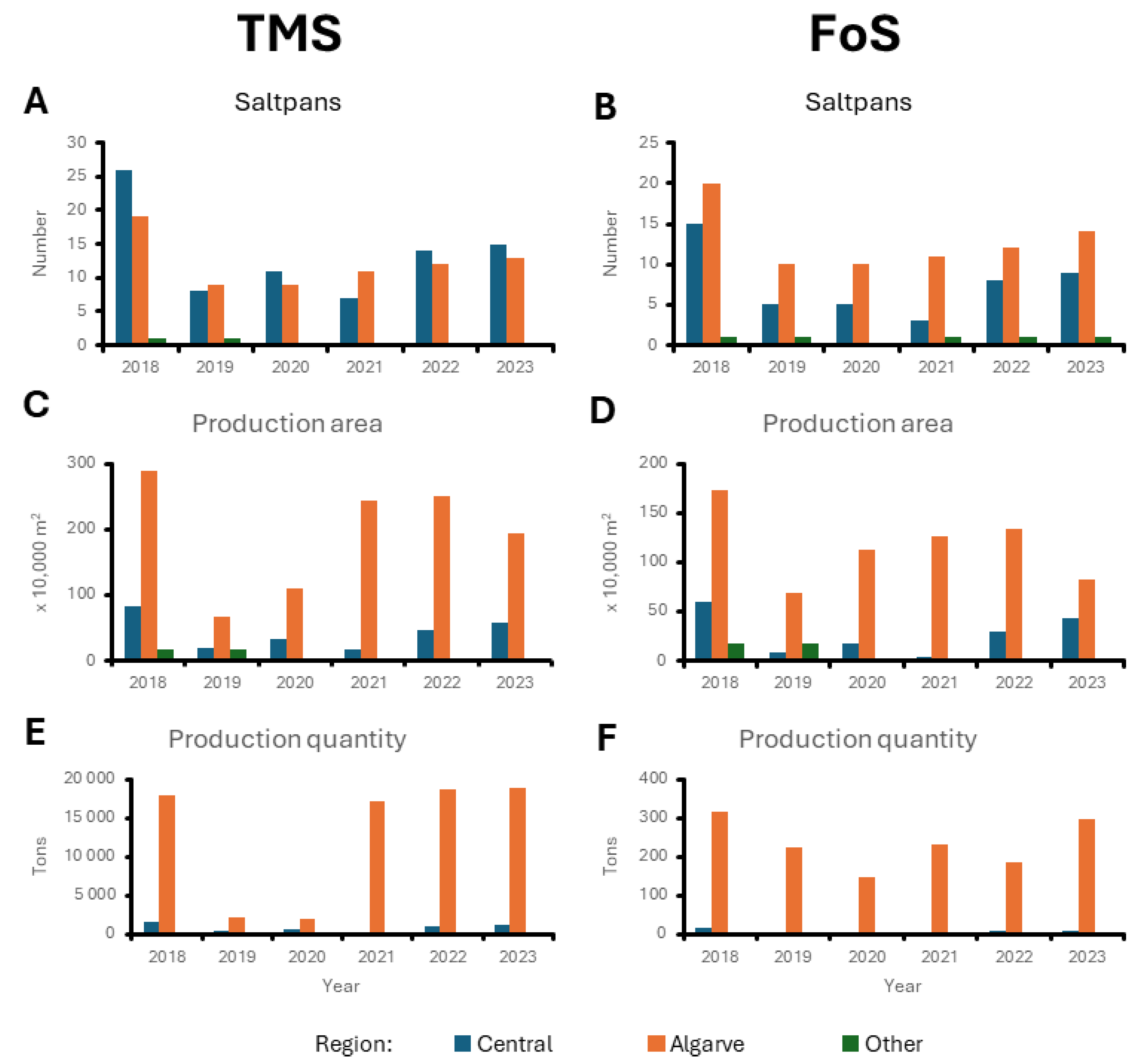

The data indicate a notable contraction in active salt pan areas between 2018 and 2019, reflecting a temporary decline in land use intensity. However, a gradual recovery followed, particularly in the Central and Algarve regions—suggesting regionally differentiated social–ecological resilience (

Figure 3A,B).

In terms of land cover, the Algarve shows consistently larger and more stable production zones, especially for fleur de sel (FoS), signaling a transition from abandonment to multifunctional use (e.g., production + tourism). Meanwhile, central Portugal exhibited fluctuating trends, highlighting sensitivity to socio-economic and environmental pressures (

Figure 3C,D).

The Algarve’s dominance in both production area and output—particularly for FoS—suggests a stronger feedback loop between ecological maintenance and market-driven service diversification. The results point to an ongoing but uneven landscape transition, shaped by human investment, ecosystem viability, and evolving land use practices (

Figure 3E,F).

4.2. Main Social–Ecological Saltscapes in Portugal

The spatial distribution of fleur de sel (FoS) and marine salt production in Portugal reveals three major coastal regions. These regions are undergoing dynamic land use and land cover transitions within coupled social–ecological systems (

Table 2).

In the central region (e.g., Aveiro, Figueira da Foz), historical saltscapes near urban centers are being reconfigured for tourism and cultural services, often adjacent to restored wetlands. Rio Maior represents an inland exception, where rock salt extraction contributes to a unique socio-environmental niche.

In the Lisbon region, marginal but persistent activity continues in the Alcochete saltmarsh, embedded in a peri-urban landscape. Here, conservation, cultural heritage, and ES provisioning increasingly shape land-use practices.

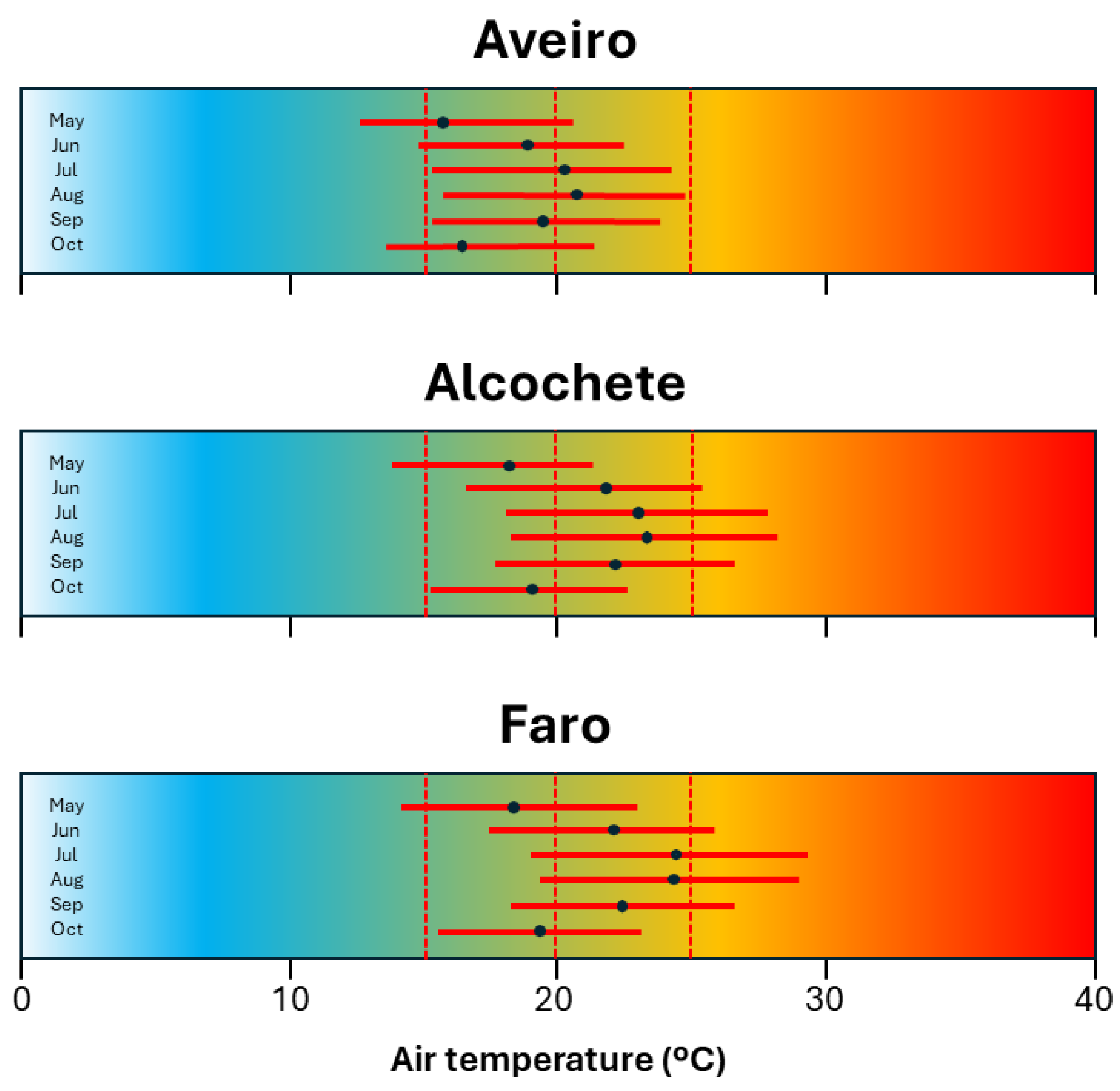

The Algarve remains the most active and ecologically resilient zone, driven by favorable climatic conditions (

Figure 4) and entrepreneurial regeneration of salt pans. Land use in this region reflects an adaptive trajectory, where production, tourism, and biodiversity conservation increasingly co-evolve.

4.3. Assessing Regeneration Through Social–Ecological and Land Use–Land Cover Change Indicators

The hypothesis was evaluated through a spatial cross-analysis of aerial imagery and national statistical datasets on salt production. Results reveal evidence of landscape-scale regeneration in multiple salt-producing areas, with observable changes in land cover configuration and social–ecological function.

In most regions analyzed—particularly in the Central region (e.g., Aveiro, Figueira da Foz) and the Algarve—salt pans show visible signs of maintenance, water management infrastructure, and active crystallization ponds, indicating ongoing or revitalized use (

Figure 5). These land cover patterns, verified against production statistics, suggest not just physical regeneration but reintegration into local economic and ecological systems, including tourism, heritage interpretation, and biodiversity conservation.

Contrastingly, the Alcochete saltmarsh complex, despite being within a protected area and adjacent to urban centers, shows limited regeneration. Only one active salt pan remains, and aerial imagery indicates broader saltscape degradation and encroachment by vegetation, suggesting reduced social engagement and declining management effort. This highlights how socio-institutional factors—such as ownership models, proximity to cultural circuits, and tourism investments—play a pivotal role in the conservation status of saltscapes.

Overall, the regeneration observed reflects a shift from abandonment toward multifunctional land use: combining niche salt production, cultural ecosystem service delivery, and habitat management. These patterns provide empirical support for interpreting salt pans as evolving social–ecological systems influenced by feedback between governance, land management, and environmental change.

4.4. Data Analysis

The integration of aerial imagery and statistical data reveals varying degrees of land use continuity and regeneration across Portugal’s salt pan landscapes. Despite methodological uncertainties inherent to visual classification, a general pattern emerges: several coastal areas show active regeneration, while others reflect stagnation or abandonment (

Figure 6).

Classifying salt pan conditions from aerial imagery involves uncertainties, particularly in distinguishing between active, abandoned, and repurposed uses. For example, industrial salt or aquaculture sites can resemble traditional pans without careful interpretation. Visible indicators such as aeration systems in aquaculture help differentiate these land uses, but classification errors remain possible.

One of the main limitations concerns the analysis of images from Google Maps, which are composite satellite mosaics (i.e., taken from different satellites). As such, there may be a temporal discrepancy of up to about 5 years, meaning they do not reflect the saltscapes’ more recent states. Another potential bias, more related to the exact dimensions of the saltscapes under analysis, is that the areas and proportions of the polygons were estimated visually without the use of GIS software.

Despite these challenges, aerial data confirm that Castro Marim hosts the largest concentration of salt pan landscapes in Portugal. In this low-population municipality, the extensive saline infrastructure appears to function as a key socio-economic and ecological asset, contributing significantly to local land use dynamics and identity (

Table 3).

In Aveiro, approximately one-third of former salt pans show renewed activity, likely linked to eco-tourism and heritage valorization, as seen in lagoon tours and saline spas (

Figure 7A).

In Figueira da Foz, another third of the pans are regenerating, situated at the transitional freshwater–saltwater interface. Rio Maior, although not coastal, represents an inland regeneration effort motivated by cultural heritage preservation, indicating a different social driver.

Alcochete, in contrast, exhibits widespread abandonment post-urban infrastructure development (e.g., Vasco da Gama Bridge), with minimal regeneration efforts maintained by an environmental foundation.

The Algarve region—i.e., Castro Marim, Olhão, Tavira, and Faro—shows the most robust regeneration, where salt pans have been revitalized for both production and nature-based tourism (

Figure 7B,C). These areas benefit from favorable hydrological conditions (e.g., Ria Formosa’s multiple tidal inlets) and a growing interest in integrating economic activity with habitat conservation. Castro Marim stands out with the largest extent of active salt pans, where regeneration appears closely tied to local livelihoods and ecological function, reflecting a strong social-ecological dependency.

These patterns reflect broader land use–land cover changes shaped by intersecting environmental, cultural, and economic dynamics.

5. Discussion

5.1. Salt Pan Landscapes as Social-Ecological Systems

Regardless of their geographic location and for various factors, saltscapes are subject to wear and tear over time, with the less maintenance they undergo, the greater the wear. In saltscapes where industrial or traditional salt production continues, clear signs of maintenance can be detected. In this regard, satellite imagery is a valuable tool for analyzing saltscapes and signs of maintenance in salt production areas (or other types of production, such as aquaculture). However, the differences between the two types of salt production are quite marked. While industrial production generally requires a considerable amount of machinery and little labor, artisanal/traditional production uses much less machinery, but requires much greater labor to maintain the production areas.

Salt pans can be characterized as being in “good” condition when there are clear signs of annual cyclical maintenance of the areas assigned to this function, ensuring the production of this commodity for the market. This maintenance not only allows for the reestablishment of good salt production, due to the adequate control of the lagoons to store waters with different saline levels, which, by establishing suitable habitats for some organisms that thrive in high salinities, are also useful for the conservation of the surrounding biodiversity, particularly the birdlife typical of these areas.

Salt production areas—especially salt marshes and salt pans—extend beyond their economic function as extraction sites. Though industrial sea salt accounts for the vast majority of production in Portugal (83%) [

64], the spatial context of saltscapes makes them increasingly relevant in land use transitions. These areas are often embedded in ecologically rich and protected zones such as wetlands, estuaries, and natural parks, creating unique intersections between ecological integrity, cultural value, and land use demand.

Despite low labor intensity in industrial salt operations, salt pan landscapes are under growing pressure and opportunity for alternative uses. Their ecological setting supports diverse biodiversity and ES, including bird habitats and carbon sequestration, while also offering potential for low-impact recreational and educational uses. As such, they represent evolving social-ecological systems where traditional extractive practices are being complemented—or replaced—by multifunctional land uses that integrate conservation, tourism, and environmental education.

5.2. Reactivation and Adaptive Reuse of Saltscapes

The regeneration of abandoned or underused salt pan areas is part of broader land use and ecological restoration dynamics in coastal Portugal [

81]. While abandonment can lead to habitat degradation or spontaneous rewilding, reactivation—especially when ecologically sensitive—can enhance ecosystem function and social value [

82,

83,

84].

Preparing these salterns for production requires labor. In the particular case of traditional salt pans, human activity takes precedence over machinery for reasons of greater sustainability and conservation [

64].

Field observations from this study reveal distinct regional patterns of land cover change, with some areas—particularly in the Algarve and Central regions—undergoing ecological or functional regeneration. These processes are increasingly being supported by hybrid models of use, such as eco-tourism, environmental education, and small-scale artisanal production. In these cases, reactivated salt pans are not merely production landscapes but become platforms for integrated ES and sustainable local economies.

Although developing ecotourism activities in saltscapes requires human resources with some specialization and education, regardless of gender, the most demanding manual labor activities are generally restricted to men. These men are often members of immigrant communities from countries with lower GDPs than Portugal, and due to a lack of resources, they resort to these types of more demanding labor activities as a source of income [

9].

5.3. Cultural-Ecological Value and the Role of Tourism

Regenerated saltscapes are often embedded with cultural heritage and environmental narratives that increase their attractiveness to visitors and planners alike [

85,

86]. Unlike industrial sites, which generally lack aesthetic and historical appeal, traditional salt pans—especially those situated in scenic or historically rich regions—offer experiences tied to both nature and culture. This makes them points of interest for local tourism and cultural interpretation [

58,

87].

To make all this work, traditional salt producers employ attractive strategies that leverage the cultural values of salt production and the surrounding ecological diversity, enhancing supporting activities, especially those related to leisure and tourism. These values, inherent in salt-derived products, can be found worldwide due to the effects of globalization. This effect also helps attract more tourists interested in these saltscapes.

Tourism-oriented reuse of salt pans—such as saline spas, nature trails, and educational programs—has emerged as a viable strategy to support multifunctional land uses [

88]. These activities not only enhance visitor engagement but also contribute to the conservation of traditional practices and local identity. When planned carefully, they serve as catalysts for socio-economic revitalization while maintaining or even improving ecosystem function.

6. Conclusions

This study examined whether the saltscapes historically associated with traditional salt production in mainland Portugal are showing signs of abandonment or regeneration, within a broader framework of social-ecological transformation and land use–land cover change (LULCC).

Using a combination of official statistical sources and spatial analysis through Google Maps imagery, it was possible to assess the condition of salt pan areas and categorize their trajectories across the country. Despite some limitations related to aerial image interpretation, this approach proved effective for identifying patterns of use, disuse, and reactivation. Another limitation that was also found was the lack of studies in social sciences.

Findings indicate a heterogeneous picture across regions, with notable evidence of regeneration, particularly in coastal areas with favorable climate and ecological value. In these contexts, salt pan areas are transitioning from single-function production zones to multifunctional landscapes. These shifts are driven by an interplay of environmental, economic, and social factors—such as protected area designation, tourism interest, cultural heritage value, and changing land use demands.

Key insights include:

- -

Saltscapes represent dynamic social-ecological systems, often situated at the intersection of natural conservation, heritage preservation, and land-based livelihoods.

- -

Their reactivation is frequently supported by multifunctional uses—including eco-tourism, environmental education, and artisanal salt production—which contribute to rural resilience and adaptive land management.

- -

Spatial and seasonal dependencies are important to consider because in more temperate northern latitudes, reactivation efforts are often constrained by climatic limitations, while southern regions show more consistent regeneration linked to tourism flows and environmental planning.

Overall, salt pans in Portugal are increasingly becoming sites of ecological and cultural revalorization, rather than strictly production-oriented spaces. Their evolving land use reflects broader LULCC processes where environmental, heritage, and socio-economic dimensions converge.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank three anonymous reviewers for the useful comments provided to improve an earlier version of the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| FoS |

Flower of salt |

| ES |

Ecosystem service(s) |

| LEK |

Local ecological knowledge |

| SES |

Social–ecological system |

| TMS |

Traditional marine salt |

| TSP |

Traditional salt production area(s) |

References

- Harding, A. (2013). Salt in prehistoric Europe. Sidestone Press.

- MacGregor, G. A., & De Wardener, H. E. (1998). Salt, diet and health. Cambridge University Press. [CrossRef]

- Sandu, I., Poruciuc, A., Alexianu, M., Curca, R. G., & Weller, O. (2010). Salt and human health: science, archaeology, ancient texts and traditional practices of Eastern Romania. Mankind Quarterly, 50(3), 225.

- Sousa, C. A., Cunha, M. E., & Ribeiro, L. (2020). Tracking 130 years of coastal wetland reclamation in Ria Formosa, Portugal: Opportunities for conservation and aquaculture. Land Use Policy, 94, 104544. [CrossRef]

- Calvert, A. F. (2023). Salt and the salt industry. Good Press.

- de Melo Soares, R. H. R., de Assunção, C. A., de Oliveira Fernandes, F., & Marinho-Soriano, E. (2018). Identification and analysis of ecosystem services associated with biodiversity of saltworks. Ocean & coastal management, 163, 278-284. [CrossRef]

- Diniz, M. T. M., Vasconcelos, F. P., & Martins, M. B. (2015). Inovação tecnológica na produção brasileira de sal marinho e as alterações sócioterritoriais dela decorrentes: uma análise sob a ótica da teoria do empreendedorismo de Schumpeter. Sociedade & Natureza, 27, 421-437. [In Portuguese]. [CrossRef]

- Dufossé, L., Donadio, C., Valla, A., Meile, J. C., & Montet, D. (2013). Determination of speciality food salt origin by using 16S rDNA fingerprinting of bacterial communities by PCR–DGGE: An application on marine salts produced in solar salterns from the French Atlantic Ocean. Food Control, 32(2), 644-649. [CrossRef]

- Ramos, J. (2023). Tourism and work environment in sea salt pans. Journal of Heritage Tourism, 18(6), 828-845. [CrossRef]

- Davy, A. J., Bakker, J. P., & Figueroa, M. E. (2009). Human modification of European salt marshes. Human impacts on salt marshes: a global perspective. University of California Press, Berkeley, California, USA, 311-336.

- Quilez, J., & Salas-Salvado, J. (2012). Salt in bread in Europe: potential benefits of reduction. Nutrition reviews, 70(11), 666-678. [CrossRef]

- Bawahab, M., Faqeha, H., Ve, Q. L., Faghih, A., Date, A., & Akbarzadah, A. (2019). Industrial heating application of a salinity gradient solar pond for salt production. Energy Procedia, 160, 231-238. [CrossRef]

- Ostrom, E. (2009). A general framework for analyzing sustainability of social-ecological systems. Science, 325(5939), 419-422. [CrossRef]

- De Andrés, M., Barragán, J. M., & Sanabria, J. G. (2018). Ecosystem services and urban development in coastal Social-Ecological Systems: The Bay of Cádiz case study. Ocean & Coastal Management, 154, 155-167. [CrossRef]

- Ramos, J., Rosová, V., & Campos, A. C. (2019). Sunny, windy, muddy and salty creative tourism experience in a salt pan. Revista Portuguesa de Estudos Regionais, (51), 41-53.

- Ramos, J., & Puertas, R. R. (2023). Deactivated Saltpans: What Are the Consequences for Nature and Tourism Behavior? In Cases on Traveler Preferences, Attitudes, and Behaviors: Impact in the Hospitality Industry (pp. 54-72). IGI Global. [CrossRef]

- Serra, P., Pons, X., & Saurí, D. (2008). Land-cover and land-use change in a Mediterranean landscape: a spatial analysis of driving forces integrating biophysical and human factors. Applied geography, 28(3), 189-209. [CrossRef]

- Tan, L., Ge, Z., Ji, Y., Lai, D. Y., Temmerman, S., Li, S., ... & Tang, J. (2022). Land use and land cover changes in coastal and inland wetlands cause soil carbon and nitrogen loss. Global Ecology and Biogeography, 31(12), 2541-2563. [CrossRef]

- Hueso-Kortekaas, K., & Carrasco-Vayá, J. F. (2024). The Patrimonialization of Traditional Salinas in Europe, a Successful Transformation from a Productive to a Services-Based Activity. Land, 13(6), 772. [CrossRef]

- Sainz-López, N. (2017). Comparative analysis of traditional solar saltworks and other economic activities in a Portuguese protected estuary. Boletín de Investigaciones Marinas y Costeras-INVEMAR, 46(1), 171-189. [CrossRef]

- Costa, S., Oliveira, E., Coelho, C., & Lopes, M. P. (2011). Erosion and deposition rates in estuaries–the saltpans area of Aveiro Lagoon, Portugal. Journal of Coastal Research, 1472-1476.

- Balsas, C. J. L. (2019). Revaluing saltscapes in Portugal: Ecotourism, ecomuseums, and environmental education. In Global trends, practices, and challenges in contemporary tourism and hospitality management (pp. 31-57). IGI Global. [CrossRef]

- Freitas, D., Gomes, J., Luis, T. S., Madruga, L., Marques, C., Baptista, G., ... & Santos-Reis, M. (2007). Otters and fish farms in the Sado estuary: ecological and socio-economic basis of a conflict. Hydrobiologia, 587, 51-62. [CrossRef]

- Vieira, N., & Bio, A. (2011). Spatial and temporal variability of water quality and zooplankton in an artisanal salina. Journal of Sea Research, 65(2), 293-303. [CrossRef]

- Athearn, N. D., Takekawa, J. Y., Bluso-Demers, J. D., Shinn, J. M., Arriana Brand, L., Robinson-Nilsen, C. W., & Strong, C. M. (2012). Variability in habitat value of commercial salt production ponds: implications for waterbird management and tidal marsh restoration planning. Hydrobiologia, 697(1), 139-155. [CrossRef]

- Sousa, L. P., Lillebø, A. I., Gooch, G. D., Soares, J. A., & Alves, F. L. (2013). Incorporation of local knowledge in the identification of Ria de Aveiro lagoon ecosystem services (Portugal). Journal of Coastal Research, (65), 1051-1056. [CrossRef]

- Saccò, M., White, N. E., Harrod, C., Salazar, G., Aguilar, P., Cubillos, C. F., ... & Allentoft, M. E. (2021). Salt to conserve: a review on the ecology and preservation of hypersaline ecosystems. Biological Reviews, 96(6), 2828-2850. [CrossRef]

- Almeida, D., Neto, C., Esteves, L. S., & Costa, J. C. (2014). The impacts of land-use changes on the recovery of saltmarshes in Portugal. Ocean & Coastal Management, 92, 40-49. [CrossRef]

- Carlos, D. M., Pereira, M., Costa, S., Pinho-Lopes, M., & Coelho, C. (2011). Walls of the saltpans of the Aveiro Lagoon, Portugal–current status and proposed new solutions using geosynthetics. Journal of Coastal Research, 1467-1471.

- Rodrigues, C. M., Bio, A., Amat, F., & Vieira, N. (2011). Artisanal salt production in Aveiro/Portugal-an ecofriendly process. Saline systems, 7, 1-14. [CrossRef]

- Borràs-Pentinat, S. (2024). The 2030 Biodiversity Strategy: The EU’s international commitment and responsibility to reverse the biodiversity loss 1. In Deploying the European Green Deal (pp. 52-76). Routledge.

- Mammides, C., Zotos, S., & Martini, F. (2024). Quantifying the amount of land lost to artificial surfaces in European habitats: A comparison inside and outside Natura 2000 sites using a quasi-experimental design. Biological Conservation, 293, 110556. [CrossRef]

- Davis, J. B., Guillemain, M., Kaminski, R. M., Arzel, C., Eadie, J. M., & Rees, E. C. (2014). Habitat and resource use by waterfowl in the northern hemisphere in autumn and winter. Wildfowl, 17-69.

- Zadereev, E., Lipka, O., Karimov, B., Krylenko, M., Elias, V., Pinto, I. S., ... & Fischer, M. (2020). Overview of past, current, and future ecosystem and biodiversity trends of inland saline lakes of Europe and Central Asia. Inland waters, 10(4), 438-452. [CrossRef]

- Morgado, R., Nobre, M., Ribeiro, A., Puga, J., & Luís, A. (2009). The importance of the Salgado for the management of wintering shorebirds in the Ria de Aveiro (Portugal). Journal of Integrated Coastal Zone Management, 9(3), 79-93.

- Knowles, J. M., Garrett, G. S., Gorstein, J., Kupka, R., Situma, R., Yadav, K., ... & Team, U. S. I. C. S. (2017). Household coverage with adequately iodized salt varies greatly between countries and by residence type and socioeconomic status within countries: results from 10 national coverage surveys. The Journal of nutrition, 147(5), 1004S-1014S. [CrossRef]

- Delbos, G. (1982). Les paludiers de Guérande et la météo. Ethnologie Française, 261-274.

- Geslin, P. (2002). L’amitié respectueuse, production de sel et préservation des mangroves de Guinée. Bois & Forets des Tropics, 273, 55-67. [CrossRef]

- Hocquet, J. C. (2006). Travailler aux mines de sel. Revue Historique, 640(4), 779-811. [CrossRef]

- Renard, M. C., & Thomé, H. (2016). Cultural heritage and food identity: The pre-Hispanic salt of Zapotitlán Salinas, Mexico. Culture & History Digital Journal, 5(1). [CrossRef]

- del Valle, L. (2023). Safeguarding intangible cultural heritage for sustainable development. The case of traditional salt activity. Journal of Cultural Heritage Management and Sustainable Development. [CrossRef]

- Moreno, J. M., & Ortiz, I. L. (2008). From industrial activity to cultural and environmental heritage: The Torrevieja and La Mata lagoons (Alicante). Boletín de la Asociación de Geógrafos Españoles, (47), 311-331.

- Lageard, J. G., & Drew, I. B. (2015). Evaporating legacies: industrial heritage and salt in Cheshire, UK. Industrial Archaeology Review, 37(1), 48-61. [CrossRef]

- Matias, P. S. S. (2012). A importância da atividade turística associada às Salinas de Rio Maior para a sustentabilidade do território (Doctoral dissertation, Instituto Politecnico de Leiria (Portugal)). [In Portuguese].

- Eggenkamp, H. G. M., Marques, J. M., & Graça, H. (2013). Application of stable chlorine isotopes to develop a conceptual model for the origin of the ground water circulating near the” salinas” at Rio Maior (Central Portugal). Comunicaçõe Geológicas, 100(1).

- Hueso, K., & Petanidou, T. (2011). Cultural aspects of Mediterranean salinas. In T. Papayannis & D. E. Pritchard (Eds.), Culture and wetlands in the Mediterranean: An evolving story (pp. 213226). Athens, Greece: Med-INA.

- Lemonnier, P., & Héral, M. (1975). Une Approche de la perception, par les paludiers guérandais, des facteurs en jeu dans la production du sel. Penn ar Bed, 10(83), 207-219.

- Perraud, C. (2005). La renaissance du sel marin de l’Atlantique en France (1970–2004). I Seminário Internacional Sobre o Sal Portugués; Amorim, I., Ed, 423-430.

- Donadio, C., Bialecki, A., Valla, A., & Dufossé, L. (2011). Carotenoid-derived aroma compounds detected and identified in brines and speciality sea salts (fleur de sel) produced in solar salterns from Saint-Armel (France). Journal of Food Composition and Analysis, 24(6), 801-810. [CrossRef]

- Kortekaas, K. H., & Vaya, J. F. C. (2009). Biodiversity of inland saltscapes of the Iberian Peninsula. Natural Resources and Environmental Issues, 15(1), 30.

- Gauci, R., Schembri, J. A., & Inkpen, R. (2017). Traditional use of shore platforms: a study of the artisanal management of salinas on the Maltese Islands (Central Mediterranean). Sage Open, 7(2), 2158244017706597. [CrossRef]

- Herbert, R. J., Broderick, L. G., Ross, K., Moody, C., Cruz, T., Clarke, L., & Stillman, R. A. (2018). Artificial coastal lagoons at solar salt-working sites: A network of habitats for specialised, protected and alien biodiversity. Estuarine, coastal and shelf science, 203, 1-16. [CrossRef]

- Ramos, J. (2022). Fleur de sel: How Does a Pinch of Suitable Choice Practices Value This Sustainable Natural Resource? Resources, 11(7), 63. [CrossRef]

- Cardoso, A. R., & Morin, L. P. (2025). Male labor scarcity, technology adoption and female labor market integration: A quantitative and qualitative study of Portugal. Economics Letters, 112347. [CrossRef]

- Sainz-López, N., Boski, T., & Sampath, D. M. R. (2019). Fleur de sel composition and production: analysis and numerical simulation in an artisanal saltern. Journal of Coastal Research, 35(6), 1200-1214. [CrossRef]

- Galvis-Sánchez, A. C., Lopes, J. A., Delgadillo, I., & Rangel, A. O. (2013). Sea salt. In Comprehensive Analytical Chemistry (Vol. 60, pp. 719-740). Elsevier.

- Nogueira, C., Pinto, H., & Guerreiro, J. (2014). Innovation and tradition in the valorisation of endogenous resources: the case of salt flower in Algarve. Journal of Maritime Research, 11(1), 45-52.

- Wu, T. C. E., Xie, P. F., & Tsai, M. C. (2015). Perceptions of attractiveness for salt heritage tourism: A tourist perspective. Tourism Management, 51, 201-209. [CrossRef]

- Jamhawi, M. M., & Hajahjah, Z. A. (2017). A bottom-up approach for cultural tourism management in the old city of As-Salt, Jordan. Journal of Cultural Heritage Management and Sustainable Development, 7(1), 91-106. [CrossRef]

- Kimic, K., Smaniotto Costa, C., & Negulescu, M. (2021). Creating tourism destinations of underground built heritage—The cases of salt mines in Poland, Portugal, and Romania. Sustainability, 13(17), 9676. [CrossRef]

- Van, K. T., Nguyen, A. T., & Tuyen, V. V. (2025). Prioritizing Risks in Production Activities: A Study of Salt Processing Enterprises in the Central Region of Vietnam. International Journal of Safety & Security Engineering, 15(2). [CrossRef]

- Martins, F., Pedrosa, A., da Silva, M. F., Fidélis, T., Antunes, M., & Roebeling, P. (2020). Promoting tourism businesses for “Salgado de Aveiro” rehabilitation. Journal of Outdoor Recreation and Tourism, 29, 100236. [CrossRef]

- Silva, P., & Carneiro, M. J. (2023). A experiência turística associada ao sal. Revista Turismo & Desenvolvimento (RT&D)/Journal of Tourism & Development, (43). [In Portuguese].

- Ramos, J., Pinto, P., Pintassilgo, P., Resende, A., & Cancela da Fonseca, L. (2022). Activating an artisanal saltpan: tourism crowding in or waterbirds crowding out? International Journal of Culture, Tourism and Hospitality Research, 16(1), 294-305. [CrossRef]

- Balsas, C. (2016). Mediterranean Saltscapes: The need to enhance fragile ecological and cultural resources in Portugal. ZARCH, (7). [CrossRef]

- Rojon, C., & Saunders, M. N. (2012). Formulating a convincing rationale for a research study. Coaching: An International Journal of Theory, Research and Practice, 5(1), 55-61. [CrossRef]

- INE (2018). Instituto Nacional de Estatística - Estatísticas da Pesca : 2017. Lisboa : INE, 2018. Available at: <url:https://www.ine.pt/xurl/pub/320384843>.. ISSN 0377-225-x. ISBN 978-989-25-0393-6.

- INE (2019). Instituto Nacional de Estatística - Estatísticas da Pesca : 2018. Lisboa : INE, 2019. Available at: <url:https://www.ine.pt/xurl/pub/358627638>. ISSN 0377-225-x. ISBN 978-989-25-0489-6.

- INE (2020). Instituto Nacional de Estatística - Estatísticas da Pesca : 2019. Lisboa : INE, 2020. Available at: <url:https://www.ine.pt/xurl/pub/435690295>. ISSN 0377-225-X. ISBN 978-989-25-0540-4.

- INE (2021). Instituto Nacional de Estatística - Estatísticas da Pesca : 2020. Lisboa : INE, 2021. Available at: <url:https://www.ine.pt/xurl/pub/280980980>. ISSN 0377-225-X. ISBN 978-989-25-0566-4.

- INE (2022). Instituto Nacional de Estatística - Estatísticas da Pesca : 2021. Lisboa : INE, 2022. Available at: <url:https://www.ine.pt/xurl/pub/36828280>. ISSN 0377-225-X. ISBN 978-989-25-0602-9.

- INE (2023). Instituto Nacional de Estatística - Estatísticas da Pesca : 2022. Lisboa : INE, 2023. Available at: <url:https://www.ine.pt/xurl/pub/66322600>. ISSN 0377-225-X. ISBN 978-989-25-0643-2.

- INE (2024). Instituto Nacional de Estatística - Estatísticas da Pesca : 2023. Lisboa : INE, 2024. Available at: <url:https://www.ine.pt/xurl/pub/439542305>. ISSN 0377-225-X. ISBN 978-989-25-0679-1.

- Imai, H. (2013). The liminal nature of alleyways: Understanding the alleyway roji as a ‘Boundary’ between past and present. Cities, 34, 58-66. [CrossRef]

- Quagliarini, E., Bernardini, G., Romano, G., & D’Orazio, M. (2023). Users’ vulnerability and exposure in Public Open Spaces (squares): A novel way for accounting them in multi-risk scenarios. Cities, 133, 104160. [CrossRef]

- Castel’Branco, R., & da Costa, A. R. (2024). From maximum urban porosity to city’s disaggregation: Evidence from the Portuguese case. Cities, 148, 104836. [CrossRef]

- Kent, J. (2022). Can urban fabric encourage tolerance? Evidence that the structure of cities influences attitudes toward migrants in Europe. Cities, 121, 103494. [CrossRef]

- Marchesani, F., Masciarelli, F., & Doan, H. Q. (2022). Innovation in cities a driving force for knowledge flows: Exploring the relationship between high-tech firms, student mobility, and the role of youth entrepreneurship. Cities, 130, 103852. [CrossRef]

- INE (n.d.). Censos 2021. Divulgação dos Resultados Provisórios. Lisboa: Instituto Nacional de Estatística. Available at: <https://www.ine.pt/>.

- IPMA (n.d.). Instituto Português do Mar e da Atmosfera. Climate monitoring. Available at: <https://www.ipma.pt/en/oclima/monitorizacao/>.

- Santos, E. S., Salazar, M., Mendes, S., Lopes, M., Pacheco, J., & Marques, D. (2017). Rehabilitation of abandoned areas from a Mediterranean nature reserve by Salicornia crop: Influence of the salinity and shading. Arid land research and management, 31(1), 29-45. [CrossRef]

- Lai, F. (2013). Nature and the city: the salt-works park in the urban area of Cagliari (Sardinia, Italy). Journal of Political Ecology, 20(1), 329-341. [CrossRef]

- Perino, A., Pereira, H. M., Navarro, L. M., Fernández, N., Bullock, J. M., Ceaușu, S., ... & Wheeler, H. C. (2019). Rewilding complex ecosystems. Science, 364(6438), eaav5570. [CrossRef]

- Mutillod, C., Buisson, É., Mahy, G., Jaunatre, R., Bullock, J. M., Tatin, L., & Dutoit, T. (2024). Ecological restoration and rewilding: two approaches with complementary goals?. Biological Reviews, 99(3), 820-836. [CrossRef]

- Zerbe, S. (2022). Types of traditional cultural landscapes throughout the world. In Restoration of Multifunctional Cultural Landscapes: Merging Tradition and Innovation for a Sustainable Future (pp. 19-76). Cham: Springer International Publishing. [CrossRef]

- Hueso-Kortekaas, K., & Iranzo-García, E. (2022). Salinas and “Saltscape” as a Geological Heritage with a Strong Potential for Tourism and Geoeducation. Geosciences, 12(3), 141. [CrossRef]

- Gordon, J. E. (2018). Geoheritage, geotourism and the cultural landscape: Enhancing the visitor experience and promoting geoconservation. Geosciences, 8(4), 136. [CrossRef]

- Nistoreanu, P., Aluculesei, A. C., & Dumitrescu, G. C. (2024). A bibliometric study of the importance of tourism in Salt landscapes for the sustainable development of rural areas. Land, 13(10), 1703. [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Conceptual framework for analyzing socio-ecological systems (SES) of saltscapes facing land use change.

Figure 1.

Conceptual framework for analyzing socio-ecological systems (SES) of saltscapes facing land use change.

Figure 2.

Conceptual representation of salt pan systems as land use units within a dynamic social-ecological landscape. A) Schematic distinction between smaller-scale, historically embedded salt pans and larger-scale industrial salt production units. This study focuses exclusively on the traditional-type salt pans due to their relevance in understanding land use transitions, ecological resilience, and multifunctional value. The coloration of evaporation surfaces was derived from actual Google Maps imagery to reflect spatial legibility and texture in saltscape assessments. B) Categorization of salt pan areas based on visible indicators of ecological or functional regeneration versus abandonment, supporting a spatial typology of land use status across coastal and estuarine zones.

Figure 2.

Conceptual representation of salt pan systems as land use units within a dynamic social-ecological landscape. A) Schematic distinction between smaller-scale, historically embedded salt pans and larger-scale industrial salt production units. This study focuses exclusively on the traditional-type salt pans due to their relevance in understanding land use transitions, ecological resilience, and multifunctional value. The coloration of evaporation surfaces was derived from actual Google Maps imagery to reflect spatial legibility and texture in saltscape assessments. B) Categorization of salt pan areas based on visible indicators of ecological or functional regeneration versus abandonment, supporting a spatial typology of land use status across coastal and estuarine zones.

Figure 3.

Histograms representing traditional marine salt (TMS) and flower of salt (FoS) data from the official annual statistics yearbook INE (2018-2024) [

58,

59,

60,

61,

62,

63,

64].

Figure 3.

Histograms representing traditional marine salt (TMS) and flower of salt (FoS) data from the official annual statistics yearbook INE (2018-2024) [

58,

59,

60,

61,

62,

63,

64].

Figure 4.

Comparison of the highest average temperatures for some cities located in each of the three traditional sea salt producing regions in Portugal. Source: IPMA [

80].

Figure 4.

Comparison of the highest average temperatures for some cities located in each of the three traditional sea salt producing regions in Portugal. Source: IPMA [

80].

Figure 5.

Central map illustrates the spatial distribution of active and formerly active salt pan landscapes across mainland Portugal, identified as part of broader land use–land cover transformations. Surrounding panels provide detailed views of these sites, classified by a four-tiered color code indicating the state of landscape change: green represents ecologically and socially regenerated areas with active land management; red marks complete abandonment with no visible maintenance or use. Yellow and orange indicate transitional stages of partial reactivation or degradation. This classification reflects degrees of social-ecological integration and land use continuity. Source: Adapted from satellite imagery (Google Maps) and overlaid with field-informed classifications.

Figure 5.

Central map illustrates the spatial distribution of active and formerly active salt pan landscapes across mainland Portugal, identified as part of broader land use–land cover transformations. Surrounding panels provide detailed views of these sites, classified by a four-tiered color code indicating the state of landscape change: green represents ecologically and socially regenerated areas with active land management; red marks complete abandonment with no visible maintenance or use. Yellow and orange indicate transitional stages of partial reactivation or degradation. This classification reflects degrees of social-ecological integration and land use continuity. Source: Adapted from satellite imagery (Google Maps) and overlaid with field-informed classifications.

Figure 6.

Aerial imagery illustrates varying land use conditions of salt pan landscapes, highlighting different stages of abandonment, regeneration, and reconfiguration. A) Highly degraded salt pans with long-term abandonment alongside recently reactivated units, reflecting land-use transition dynamics. Location: Olhão. B) Persistent inactivity in former saline landscapes, with limited ecological or productive function. Location: Alcochete. C) Salt pans showing signs of recent but discontinued use, suggesting ongoing pressure from social and economic drivers. Location: Castro Marim. D) Seasonally reactivated units indicating adaptive land use based on environmental and economic conditions. Dry, structured pans (right) contrast with flooded ones (left), pointing to spatial variability in management. Location: Olhão. E) Large-scale industrial salt extraction infrastructure, distinguishable by scale and surrounding transport networks (e.g., highway). Location: Alcochete. Source: The aerial images were adapted from Google Maps.

Figure 6.

Aerial imagery illustrates varying land use conditions of salt pan landscapes, highlighting different stages of abandonment, regeneration, and reconfiguration. A) Highly degraded salt pans with long-term abandonment alongside recently reactivated units, reflecting land-use transition dynamics. Location: Olhão. B) Persistent inactivity in former saline landscapes, with limited ecological or productive function. Location: Alcochete. C) Salt pans showing signs of recent but discontinued use, suggesting ongoing pressure from social and economic drivers. Location: Castro Marim. D) Seasonally reactivated units indicating adaptive land use based on environmental and economic conditions. Dry, structured pans (right) contrast with flooded ones (left), pointing to spatial variability in management. Location: Olhão. E) Large-scale industrial salt extraction infrastructure, distinguishable by scale and surrounding transport networks (e.g., highway). Location: Alcochete. Source: The aerial images were adapted from Google Maps.

Figure 7.

Tourism and recreational activities as emerging land use practices in regenerated salt pan areas, reflecting broader social-ecological transformations. A) Salt pan-based wellness facility (saline spa) in Aveiro, representing adaptive reuse of historical landscapes. Source: Frame from a report aired on national public television. B) Eco-tourism infrastructure integrated into a reactivated salt landscape in Olhão. Source: Photo courtesy of Veronika Rosová. C) Educational and interpretative visit to a salt pan site, illustrating community engagement with multifunctional land use. Source: Photo by the author.

Figure 7.

Tourism and recreational activities as emerging land use practices in regenerated salt pan areas, reflecting broader social-ecological transformations. A) Salt pan-based wellness facility (saline spa) in Aveiro, representing adaptive reuse of historical landscapes. Source: Frame from a report aired on national public television. B) Eco-tourism infrastructure integrated into a reactivated salt landscape in Olhão. Source: Photo courtesy of Veronika Rosová. C) Educational and interpretative visit to a salt pan site, illustrating community engagement with multifunctional land use. Source: Photo by the author.

Table 1.

Entrepreneurial Innovation in saltscapes and its socio–ecological and land-use impacts.

Table 1.

Entrepreneurial Innovation in saltscapes and its socio–ecological and land-use impacts.

| Innovation/Practice |

Social–Ecological Component |

Land-Use / Land-Cover Change Impact |

| - Harvesting techniques for fleur de sel

|

- Requires local ecological knowledge (LEK) for surface collection and ecological timing |

- Reactivation of crystallizer ponds for production management |

| - Revalorization of artisanal salt products |

- Cultural valorization of traditional foods; reconnection to heritage production systems |

- Conversion of disused salt pans into heritage-linked productive land use |

| - Higher income from premium products |

- Economic incentive for producers to remain in or return to traditional livelihoods |

- Prevents abandonment; promotes continued or expanded salt production |

| - Tourism and cultural entrepreneurship |

- Integration of ecosystem services (recreation, education, well-being) with extractive use |

- Creation of multifunctional landscapes blending production and tourism |

| - Infrastructure for tourism (e.g., trails, spas) |

- Involvement of new stakeholders; diversification of service-based land use |

- Physical transformation of salt pan surroundings for public access and services |

| - Cultural recognition (e.g., intangible heritage status) |

- Institutional support for maintaining traditional practices |

- Long-term land-use conservation; reduced risk of conversion to urban or intensive agriculture |

Table 2.

Quantitative data related to traditional salt production areas (TSP) in Portugal. Sources: INE [

67,

68,

69,

70,

71,

72,

73,

79]. Notes: n.a. stands for non-available data. Jobs were estimated through contact with the managers of some production units.

Table 2.

Quantitative data related to traditional salt production areas (TSP) in Portugal. Sources: INE [

67,

68,

69,

70,

71,

72,

73,

79]. Notes: n.a. stands for non-available data. Jobs were estimated through contact with the managers of some production units.

| Region and municipality |

Inhabitants

(2021)

|

Municipality area (km2) |

People density (Pop/km2) |

TSP area

(ha)

|

Estimated TSP jobs

(No. workers)

|

| Centre |

|

|

|

|

|

| + Aveiro |

80,880 |

198 |

408 |

~270 |

100-150 |

| + Figueira da Foz |

62,125 |

379 |

164 |

~300 |

n.a. |

| Lisbon and Tagus |

|

|

|

|

|

| + Rio Maior |

21,192 |

273 |

78 |

2.7 |

20-30 |

| + Alcochete |

17,569 |

128 |

137 |

~360 |

n.a. |

| Algarve |

|

|

|

|

|

| + Faro |

60,995 |

203 |

300 |

~200 |

n.a. |

| + Olhão |

45,396 |

131 |

347 |

~400 |

50-70 |

| + Tavira |

26,167 |

607 |

43 |

~290 |

n.a. |

| + Castro Marim |

6,747 |

301 |

22 |

~540 |

200-250 |

Table 3.

Spatial distribution of key salt pan landscapes by region and municipality across mainland Portugal. The table presents an assessment of land use conditions based on aerial imagery (Google Maps) and a simplified classification system (from Equations 1 and 2), estimating the proportion of salt pan areas in different stages of ecological regeneration (Categories PA to PD). This evaluation reflects broader patterns of landscape transformation, abandonment, and reactivation within coastal social-ecological systems.

Table 3.

Spatial distribution of key salt pan landscapes by region and municipality across mainland Portugal. The table presents an assessment of land use conditions based on aerial imagery (Google Maps) and a simplified classification system (from Equations 1 and 2), estimating the proportion of salt pan areas in different stages of ecological regeneration (Categories PA to PD). This evaluation reflects broader patterns of landscape transformation, abandonment, and reactivation within coastal social-ecological systems.

| Region/municipality |

TSP area (ha)* |

Condition |

| PA |

PB |

PC |

PD |

| Centre |

|

|

|

|

|

| + Aveiro |

~270 |

0.5 |

0.15 |

0.05 |

0.3 |

| + Figueira da Foz |

~300 |

0.05 |

0.25 |

0.4 |

0.3 |

| Lisbon and Tagus |

|

|

|

|

|

| + Rio Maior** |

2.7 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

| + Alcochete |

~360 |

0 |

0.9 |

0.09 |

0.01 |

| Algarve |

|

|

|

|

|

| + Faro |

~200 |

0.19 |

0.01 |

0.05 |

0.75 |

| + Olhão |

~400 |

0.05 |

0.05 |

0.1 |

0.8 |

| + Tavira |

~290 |

0 |

0.25 |

0.5 |

0.25 |

| + Castro Marim |

~540 |

0.05 |

0 |

0.05 |

0.9 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).