1. Introduction

Total knee arthroplasty (TKA) has been proven to be highly effective in providing pain relief and improving physical function, thereby enhancing the quality of life of patients [

1,

2]. This surgical procedure can effectively alleviate pain, bone deformity, and joint contracture due to severe arthritis, and can also lead to an improvement in lower limb function. However, postoperative muscle atrophy and neuromuscular deficits may occur [

3], which can negatively impact the ability to perform functional movements, such as climbing stairs and walking. Bade et al. reported that older adults who underwent TKA experienced an 18% decrease in walking speed, a 51% decrease in stair climbing speed, and a 40% reduction in quadriceps femoris strength within a year after surgery compared to older adults who did not undergo the procedure [

4]. Therefore, it is recommended that patients begin exercising as early as possible after TKA to achieve optimal surgical outcomes, including pain relief and improved lower limb function [

5].

The post-surgical rehabilitation program for TKA can vary based on the environment, but it typically focuses on pain and edema management, restoring the range of motion (ROM) of the knee joint, strengthening the lower limbs, achieving a normal walking pattern, and training for functional activities[

6]. Strength training can be categorized into open and closed kinetic chain exercises, depending on whether weight bearing is involved. Open kinetic chain exercises are more effective in isolating muscle groups and promoting concentric muscle contractions [

7]. Closed kinetic chain exercises are reportedly more effective in eliciting a wider range of functional movements and promoting movements in various planes, as well as concentric and eccentric contractions, compared to open kinetic chain exercises. Additionally, closed kinetic chain exercises are beneficial in improving proprioception.

Rehabilitation exercises following joint replacement surgery are currently primarily based on open kinetic chain exercises [

4]. However, these exercises are not considered functional-based due to their lack of similarity to everyday movements, and they may increase shear forces on the artificial joint [

8] [

9]. To improve clinically practical function in patients undergoing TKA, it is necessary to consider closed kinetic chain exercises, which can enhance balance, increase joint pressure to effectively stimulate proprioceptive systems [

7], and improve muscle strength, power, stability, and balance, thus qualifying as functional exercises. However, there is a lack of research on early closed kinetic chain exercises and functional exercises following TKA. Therefore, there is a need for studies to validate these approaches, as changes in rehabilitation methods are not currently supported by sufficient evidence [

8]. This study aimed to examine the effects of 12-week closed kinetic chain exercise programs and open kinetic chain exercise programs on muscle strength, balance, ROM, and functional gait ability in patients who underwent TKA.

2. Materials and Methods

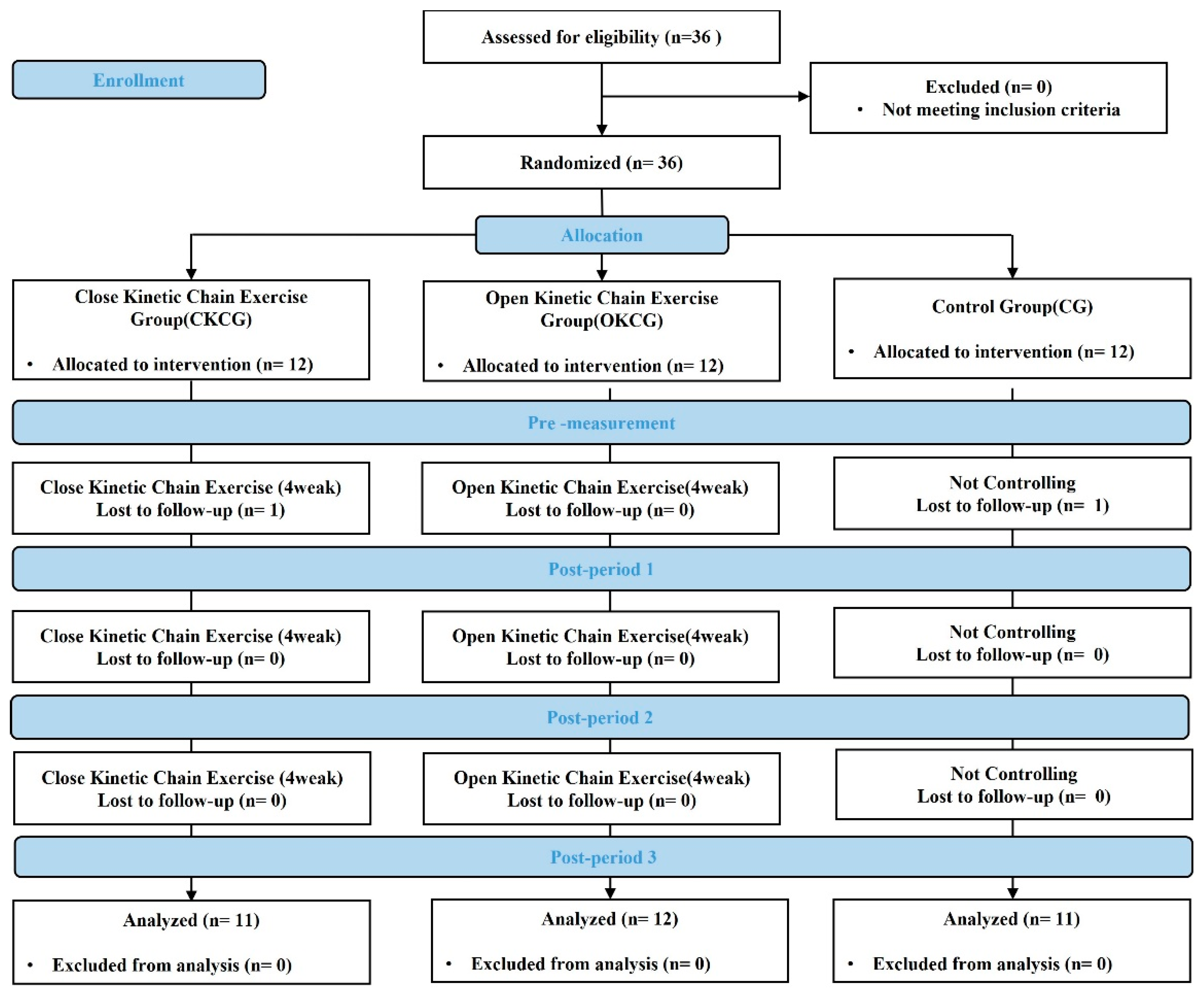

The study enrolled female patients aged 65 to 80 years who underwent TKA at G Hospital in Incheon Metropolitan City. Patients with cognitive impairments, those unable to engage in continuous exercise for three months, and those with a history of lower limb muscle weakness or pathology related to central or peripheral neurological disorders were excluded. The G-power program was used to determine the sample size, with an effect size of .30, a significance level (α) of .05, and a power of .80. This resulted in a sample size of 30 subjects, with a total of 36 subjects being recruited, considering dropout rates. The 36 study subjects were randomly assigned to three groups: the experimental group (CKCG, n=12); the comparison group (OKCG, n=12); and the control group (CG, n=12). During the initial interviews, the randomization was performed by an independent administrator who did not participate in the study, using sealed envelopes. During the study, one participant from the experimental group and one from the control group dropped out, resulting in the exclusion of two subjects. Therefore, the data of 34 participants were analyzed. The general physical characteristics of the participants are presented in

Table 1. Detailed explanations of the study purpose, methods, and procedures were provided to the participants. Written, informed consent was obtained from all participants. The study procedures were approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of G University Hospital (IRB No: GDIRB2022-095);

Figure 1. All surgeries were done by the senior authors using a medial para-patellar approach and using a posterior stabilized, high-flexion flexion designed total knee prostheses (LOSPA Knee System (CORENTEC Co., Ltd., South Korea), Anthem, Smith & Nephew Inc., Vanguard Complete Knee System (Zimmer Biomet, Warsaw, IN)).

Exercise Intervention Programs

The exercise intervention programs were conducted for one hour twice per week for 12 weeks. The experimental group (CKCG) received a program based on closed kinetic chain exercises, and the comparison group (OKCG) received a program based on open kinetic chain exercises. The programs for both groups consisted of 10–15 min of warm-up, 35 min of main exercises, and 10–15 min of cool-down exercises during the 1-h sessions. The control group was not regulated regarding exercises. The warm-up exercises included stretching exercises targeting the hip, knee, and ankle joints. The main exercises were conducted according to each exercise program, gradually increasing the load based on the Rating of Perceived Exertion (RPE). The cool-down exercises included walking exercises and adjusting the walking speed based on the RPE. The exercise intervention programs are described in

Table 2.

1). Closed Kinetic Chain Exercise

The closed kinetic chain exercise program was modified based on previous research findings [

8], and was initiated two weeks after the surgery. During the first four weeks, the main exercises comprised mini squats, standing pelvic lifts, standing ankle raises, and stair climbing exercises. From weeks five to eight, the exercises included semi-squats, mini lunges, stair climbing, and single leg standing exercises. During weeks nine to twelve, participants performed squats, lunges, high stair climbing, and single leg standing exercises. A rest period of 40–60 s was provided between sets, and the intensity of the exercises was gradually increased to an RPE level of 12–15. The height of the stair climbing exercise was adjusted according to the subjects' levels. Similarly, the difficulty of the single leg standing exercise was adjusted according to the subjects' levels by blocking vision and changing the surface conditions. The exercise intervention protocol of the experimental group is outlined in

Table 3.

2). Open Kinetic Chain exercise

The combined kinetic chain exercise program was modified based on previous studies [

8,

10]. The program was administered to study participants two weeks after their surgeries, and was performed according to their improved fitness level. The combined kinetic chain exercise program was conducted for 12 weeks, starting the second week after surgery. From Weeks 1 to 4, the main exercise program consisted of seated knee flexion, seated knee extension, standing ankle raises, and lying leg raises. During Weeks 5 to 8, the exercises included seated knee flexion, seated knee extension, stair climbing, and single leg standing exercises. During Weeks 9 to 12, the participants performed seated knee flexion, seated knee extension, side stair climbing, and single leg standing exercises. The rest period between sets was 40–60 s, and knee flexion and extension exercises were performed using exercise equipment. The exercise intensity was gradually increased to achieve an RPE level of 12–15. The height for stair climbing was adjusted according to the subjects' levels, and the difficulty of the single leg standing exercise was adjusted according to the subjects' levels by blocking vision and changing the surface conditions. The combined kinetic chain exercise program is described in

Table 4.

Measurement Items and Methods

1). Evaluation of Muscle Strength

A portable muscle tester (MicroFET 2, Hoggan Health Industries, UT) was used to measure the patient’s knee flexion and extension strength. Knee flexion was measured by placing the device on the Achilles tendon, while knee extension was assessed at the closest point to the fibula head. The measurements were repeated three times, and the highest value was used in the analysis. The reliability of this test is ICC=0.86–0.94 [

11,

12].

2). Measurement of static balance

To measure single-leg balance ability, participants were instructed to stand on one leg with their eyes open, and maintain the stance with both hands on their hips. The measurement ended when the foot touched the floor, with a maximum duration of 120 s. The measurements were repeated three times, and the maximum value was used. The reliability of the single-leg standing test is ICC=0.75–0.97 [

13].

3). Measurement of dynamic balance

The Timed Up and Go (TUG) test was conducted to measure dynamic balance ability. The participant sat on a chair 50 cm high, and upon hearing the starting signal, stood up, walked to a point 3 meters ahead, turned around, and returned to their seat. The time taken for this task was recorded. The subjects performed this test without assistance from others, at a brisk walking pace, but not running. The test was repeated twice, and the mean value was calculated. The TUG test is a reliable test for quantifying functional improvement after TKA [

14,

15], with a reliability level of ICC=0.91–0.92 [

16].

4). Measurement of range of motion

To measure the ROM of the joints, a digital goniometer (HALO) was utilized as the measuring tool. The subjects took a prone position with the goniometer attached to the ankle. After aligning the zero point, the knee joint was flexed as much as possible, and the angle was measured. The mean value was obtained by repeating the measurement three times to minimize the error between measurements. The maximum flexion angle was set at 135°, and a higher number indicates greater flexibility.

5). Gait test

The 6-Minute Walk Test (6MWT) was conducted to evaluate gait ability. The 6MWT is a reliable test for evaluating overall mobility after TKA [

17]. In the 6MWT, the individual is asked to walk as far as possible for 6 min on a flat, solid surface, and the total distance covered during this time is recorded. The fastest walking pace without running achieved for 6 min is also measured.

6). Knee function assessment

The Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index (WOMAC) was used to evaluate physical function. WOMAC is highly reliable and is widely applied in patients who have undergone total arthroplasty. The evaluation involves five items for pain, two for stiffness, and 17 for physical function. The maximum score is 96 points, with higher scores indicating better physical function, whereas lower scores indicate poorer physical function and greater disability.

7). Lower limb pain evaluation

The Visual Analog Scale (VAS) was used to measure pain intensity. Participants were requested to subjectively rate their level of pain using a pain scale ranging from 0 (no pain) to 10 (extreme pain that is difficult to tolerate).

Data Processing

The data collected in this study were analyzed using the SPSS 23.0 statistical software (IBM Corp., Somers, NY, USA). Mean ± standard deviation was calculated and used. The normality was tested using the Shapiro–Wilk test, and the homogeneity of the data was assessed using the independent t-test. A two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with repeated measures was used to assess changes between groups based on the intervention methods. Considering that this study was conducted on patients after surgery, analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) was performed for variables exhibiting significant differences in homogeneity between groups at the pre-test stag. When significant differences were identified, post-hoc comparisons between time points were conducted using the Bonferroni test. Differences between each group were assessed using independent samples t-tests. The significance level for all tests was set at α = .05.

3. Results

3.1. Comparison of Measurement Items Among Three Groups

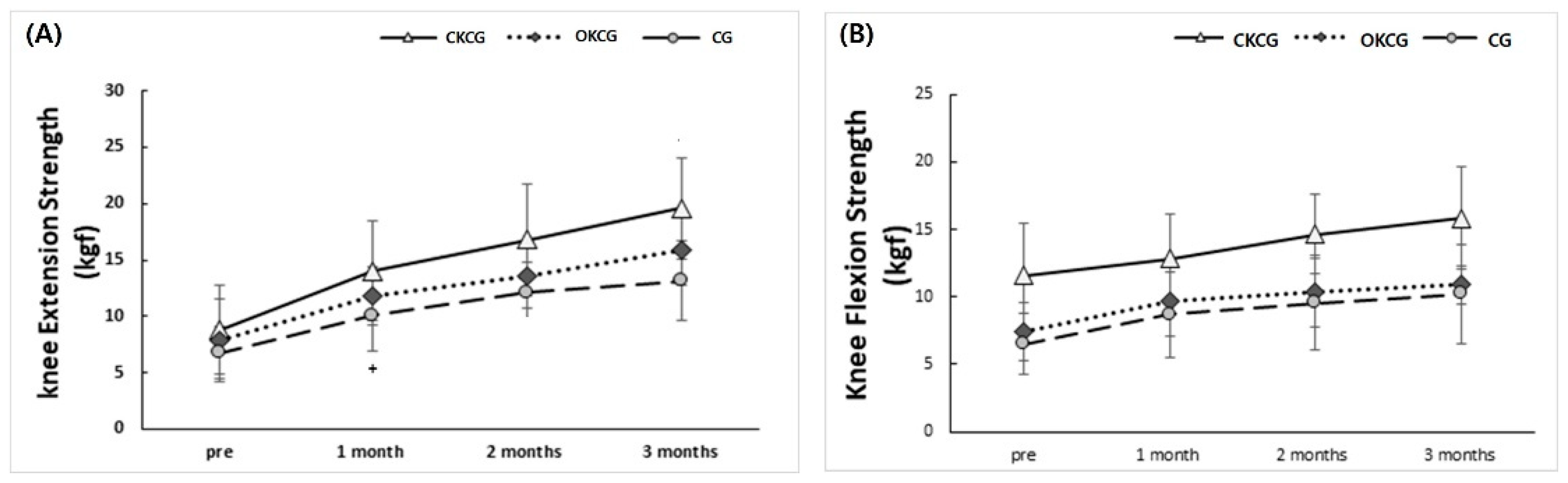

3.1.1. Changes in Knee Extension Strength Subsection

The analysis of the effect of rehabilitation exercises on knee extension strength in participants who underwent TKA showed significant differences according to the measurement time (p < .001) and between groups (p = .013). Post-hoc analysis revealed that in the CKCG group, knee extension strength significantly increased by 122% from baseline (8.80±3.94) at 3 months post-intervention (19.60±4.50) (p < .001). In the OKCG group, knee extension strength increased by 102% from baseline (7.87±3.62) at 3 months post-intervention (15.90±3.10) (p < .001). In the CG group, knee extension strength increased by 97% from baseline (6.75±2.30) at 3 months post-intervention (13.13±3.55) (p < .001) (

Figure 2A). Significant differences were observed between CKCG and OKCG at two month (17.1±4.4 vs. 14.3±3.4, p=0.029) and three months (19.5±4.5 vs. 16.5±3.8, p=0.032) post-intervention. Both of CKCG and OKCG showed significantly higher power than CG at 3 months post-intervention (p = 0.018 and 0.021, respectively).

3.1.2. Changes in Knee Flexion Strength (Figure 2B)

The findings revealed that the pre-test knee flexion strength, which was entered as a covariate, significantly influenced the dependent variable, with F = 25.196 and p < .001. However, there was no statistically significant difference in the interaction between groups and periods (p=.463). Consequently, the results of the main effect analysis indicated that there were no significant differences between groups (p = .213) or over time (p = .096) at the p < .05 level. The analysis of the differences between groups over time revealed that CKCG increased by 36% from baseline (11.6±3.9) at 3 months post-intervention (15.8±3.8), whereas OKCG increased by 46% from baseline (7.4±2.1) at 3 months post-intervention (10.9±1.5). The CG showed a 57% increase from baseline (6.5±2.3) at 3 months post-intervention (10.2±3.7).

3.1.3. Balancing Test (Single Leg Stance Test for Static Balancing and Timed Up and Go for Dynamic Balancing)

No statistically significant difference was observed in the interaction of groups and periods (p=.348). The analysis of the differences between groups over time revealed that CKCG increased by 202% from baseline (17.67±17.07) at 3 months post-intervention (53.45±44.33), OKCG increased by 215% from baseline (8.44±7.66) at 3 months post-intervention (26.61±28.59), and CG increased by 458% from baseline (4.51±4.33) at 3 months post-intervention (25.21±35.97). Time Up and Go (TUG) change were not different between groups (p=.427) and over time (p=.185) at the p<.05 level. The analysis of the differences between groups over time revealed that CKCG decreased by 35% from baseline (10.47±1.61) at 3 months (6.84±0.44), OKCG decreased by 52% from baseline (16.74±9.49) at 3 months (8.16±2.76), and CG decreased by 40% from baseline (13.26±4.60) at 3 months (8.05±1.17).

3.1.4. Changes in Knee Flexion ROM

All groups showed increased flexion ROM over time (p<.001). However, there was no statistically significant difference in the interaction between groups and periods (p = .299). CKCG increased by 31% from baseline (79.1±12.3) at 3 months post-intervention (103.7±17.7), while OKCG increased by 56% from baseline (58.1±16.6) at 3 months post-intervention (90.7±14.2). CG showed a 45% increase from baseline (65.3±30.7) at 3 months post-intervention (95.2±20.5).

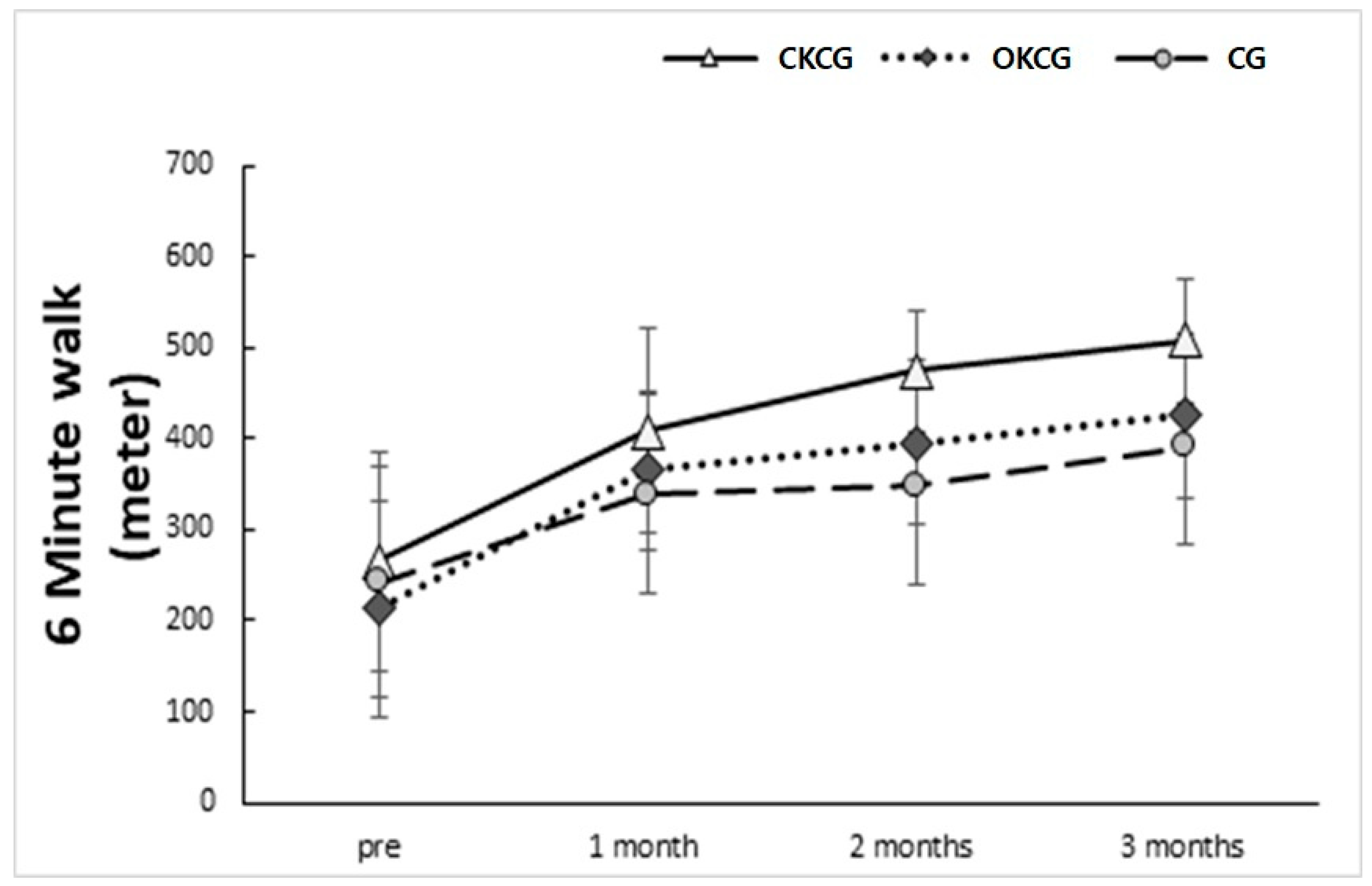

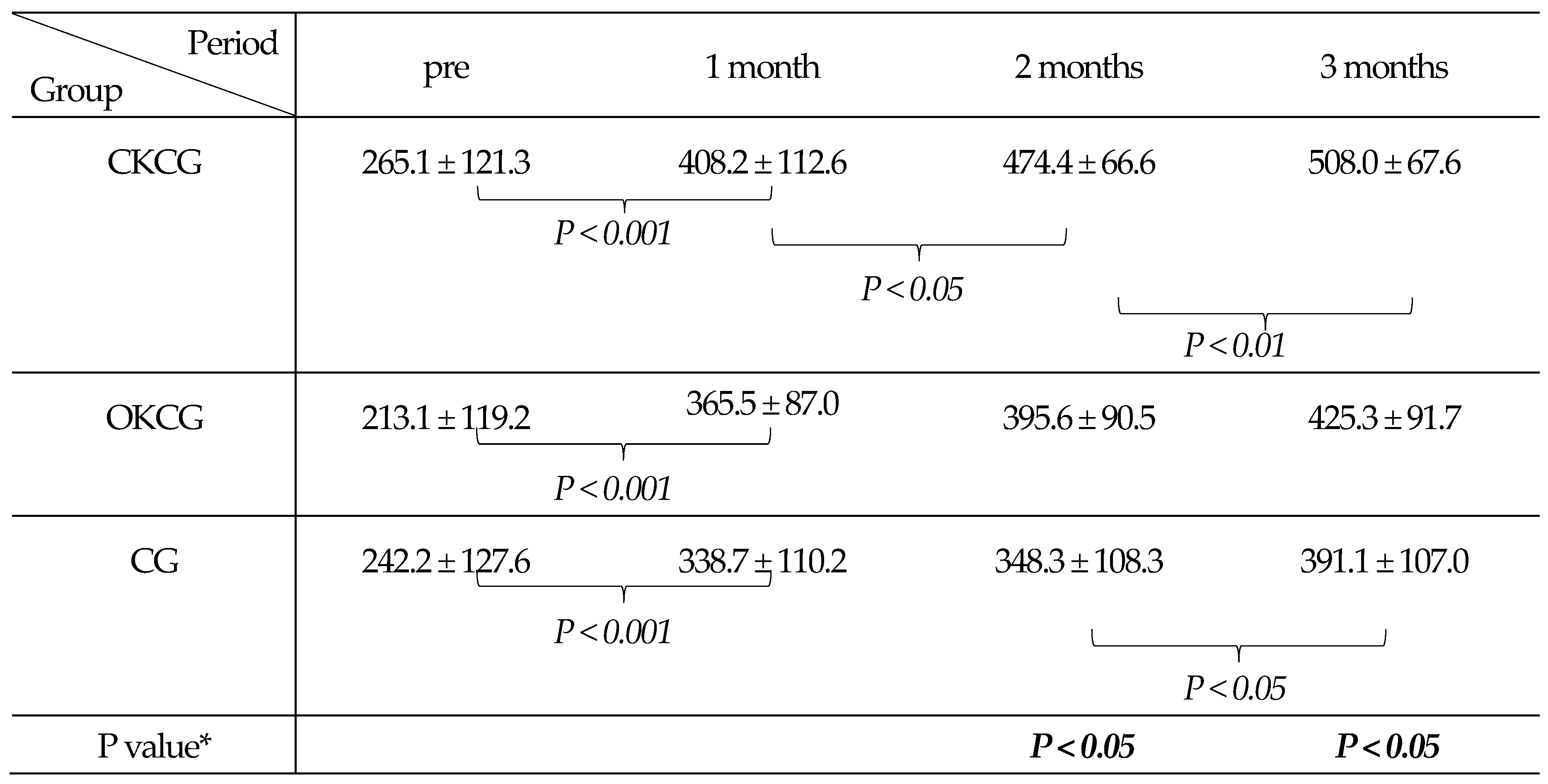

3.1.5. Changes in the 6-Min Walk

Gait performance (6MWT) significantly increased over time across all groups. CKCG group showed significantly increased gait performance at every month, and longer distance than OKCG and CG. Post-hoc analysis revealed that CKCG increased by 91% from baseline (265.1±121.3) at 3 months post-intervention (508.0±67.6) (p<.001), OKCG increased by 99% from baseline (213.1±119.2) at 3 months post-intervention (425.3±91.7) (p<.001), and CG increased by 61% from baseline (242.2±127.6) at 3 months post-intervention (391.1±107.0) (p<.001) (

Table 5). Significant differences were observed between the CKC and OKCG at two months (p=.028) and three months (p=.024). For CKC and CG, significant differences were observed at two months (p=.006) and three months (p=.007). However, no significant differences were observed between OKCG and CG (

Figure 3).

3.1.6. Changes in WOMAC

There was no statistically significant difference in the interaction between groups and periods (p=.092). The main effect analysis results showed no significant differences between groups (p=.876) and over time (p=.140). The analysis of the differences between groups over time revealed that CKCG decreased by 53% from baseline (35.2±15.1) at 3 months post-intervention (16.5±10.0), while OKCG decreased by 45% from baseline (48.5±18.8) at 3 months post-intervention (26.3±17.3). CG showed a 48% decrease from baseline (53.8±17.7) at 3 months post-intervention (28.0±18.9).

3.1.7. Change in VAS

There was no statistically significant difference in the interaction between groups and periods (p = .370).The main effect analysis revealed no significant differences between groups (p=.268) and over time (p=.839). The analysis of the differences between groups over time revealed that CKCG decreased by 64% from baseline (5.18±1.72) at 3 months post-intervention (1.97±1.76), while OKCG decreased by 67% from baseline (6.17±2.21) at 3 months post-intervention

4. Discussion

This primary objective of the study was to investigate the effects of a 12-week closed kinetic chain exercise program and open chain exercise program on muscle strength, balance, ROM, gait, activities of daily living, and pain in older patients who underwent knee arthroplasty. The main findings of the study are as follows. ROM, Static and dynamic balance abilities were improved over time across all groups and no significant difference between groups and periods. Analysis of the knee pain (VAS) and function assessment (WOMAC) showed no statistically significant difference in both groups. But there were significant increases in three groups and over time in knee extension strength, with the CKCG showing the greatest increase (p=0.013). Analysis of gait performance (6MWT) significantly increased over time across all groups.

1. Muscle Strength

After knee arthroplasty, patients with functional limitations in daily life typically exhibit knee extension strength levels that are 30% lower than those of the healthy side, while patients without functional limitations showed an average of 12% lower strength levels [

18]. The more severe the decrease in lower limb muscle strength after TKA, the higher the average pain level [

19]. To address these issues, the goal of the treatment program for patients who undergo TKA is to restore and improve lower limb strength, and functional exercises are important [

20,

21]. Early initiation of strength training after TKA has been shown to reduce knee pain, restore ROM, restore lower limb strength, and prevent knee stiffness [

22]. Wei-Hsiu et al. [

23] reported that a group that received progressive resistance exercises for 12 weeks displayed significant improvements in knee extensor and flexor strength compared to the control group among patients undergoing knee arthroplasty.

This study identified statistically significant differences in knee extension strength between groups and over time. Among them, significant differences were observed in all periods between CKCG and OKCG, whereas in CG, no significant differences were observed except for the 2-month and 3-month periods. Significant results were not found between the CKCG and OKCG; however, significant differences were observed between CKCG and CG at 1, 2, and 3 months post-intervention. OKCG and CG showed significant differences only in three months post-intervention. Like the findings of Wei-Hsiu et al.[

23], Progressive strength training provided significant increases in knee extension strength, with CKCG demonstrating the greatest improvement. It is suggested that closed kinetic chain exercises may contribute to the improvement of knee extension strength.

In contrast to knee extension strength, no significant differences were found in knee flexion strength. However, at both baseline and after three months, all three groups showed improvements in strength, with CKCG increasing by 36%, OKCG by 46%, and CG by 57%. Although CKCG showed the lowest improvement, its records at three months far surpassed those of the other groups. The lack of significant difference may be attributed to insufficient exercises targeting knee flexion strength in the CKCG exercise program. Therefore, additional exercises to improve knee flexion strength should be considered in the future.

2. Balance

Patients who underwent TKA scored lower on tests of balance and mobility than those who did not undergo surgery [

2,

24]. The ability of the knee joint to provide balance is diminished after TKA, thereby increasing the risk of falls [

12]. Postoperative pain and functional movement impairments, such as balance deficits, can lead to a loss of proprioceptive ability [

25]. Therefore, exercises for postoperative functional recovery are necessary. Balance is generally divided into static and dynamic balance. Static balance refers to maintaining balance while staying still, whereas dynamic balance involves maintaining stability while the body is in motion. Patients who undergone TKA may experience long-term functional impairment, chronic pain, and instability, leading to a progressive deficiency in proprioception. Rätsepsoo et al. [

26] demonstrated that strengthening the extensor muscles of the knee joint increases stability and reduces the fear of falling.

This study evaluated the ability to maintain static balance by performing the single-leg stance test with eyes open. However, statistically significant differences were not observed. However, an analysis of the change in the mean over time revealed that all three groups showed a high level of improvement. Among them, CKCG recorded the highest mean value at three months. This is speculated to be due to the effectiveness of closed kinetic chain exercises on both concentric and eccentric contractions and the significant role of deceleration and control in body movement. In this study, the Timed Up and Go test was performed to evaluate the dynamic balance, but there was no statistically significant difference. However, all three groups demonstrated improvement in the mean values over time. CKCG showed a decrease of 35% from baseline at 3 months, OKCG decreased by 52%, and CG decreased by 40%. CKCG showed the lowest improvement, but the measured results at three months showed an average of less than 6 s. Achieving 6 s or less in the TUG measurement is considered a high level of performance. Therefore, although significant results were not observed in CKCG, it is inferred that there was improvement to a level of normal function. In future research, if homogeneity is ensured in pre-tests and the effectiveness is verified through comparisons between pre-intervention and post-intervention, it is expected that favorable results will be obtained.

3. Range of Motion

The limitation of knee joint flexion is a major factor contributing to mobility impairment in patients with degenerative knee osteoarthritis [

27]. After TKA, severe pain and discomfort make voluntary exercise participation challenging, leading to gradual muscle weakness in the legs and stiffness in the joints. Within one month after surgery, quadriceps femoris strength can decrease by 60%, functional performance by 88%, and 52% of patients report issues with functional activity limitation [

5]. Therefore, it is recommended to initiate exercise as early as possible after TKA to achieve optimal surgical outcomes, alleviate pain, increase joint mobility, and enhance the functional performance of the knee joint [

5]. It has been reported that restoring joint mobility beyond a certain level after surgery is also an important determinant of surgical outcomes [

28].

In this study, there was no statistically significant interaction effect of groups and periods on the ROM of knee flexion, but there was a significant difference over time. All three groups showed improvement over time, but CKC exhibited the lowest improvement. These results suggest that the intervention program applied in this study focused on improving function rather than improving ROM. In the CKCG intervention program, there were no movements where the knee flexion angle exceeded 90º, and it is speculated that higher results were not observed due to the tension of the thigh muscles caused by continuous strength exercises. Furthermore, the ROM measurement in the prone position conducted in this study requires relaxation of the quadriceps femoris and contraction of the hamstrings. Therefore, in future studies, passive and active stretching interventions and changes in measurement methods should be considered to improve the ROM of knee flexion.

4. Gait

Patients with knee arthritis have abnormal walking patterns due to pain, joint instability, and muscle weakness [

29,

30]. Fantozzi et al. [

31] reported a decrease in knee flexion angle and step length during walking after knee arthroplasty, along with simultaneous contraction of the rectus femoris muscle, hamstring, gastrocnemius, and tibialis anterior muscles. The issues with walking after surgery can be expected to improve with the recovery of lower limb strength in the early stages following surgery [

3].

In this study, the 6MWT showed a significant difference over time, and when comparing the baseline and three months post-intervention for all three groups, CKCG showed a 91% increase, OKCG showed a 99% increase, and CG showed a 61% increase. These results are consistent with the report of Kwon et al. [

7], indicating that the intervention program not only led to increased simple muscle strength but also improved joint stability and balance through movements such as single-leg stance and stair climbing, resulting in enhanced proprioception. It is suggested that further research should be conducted to identify exercise movements that can increase walking ability, leading to improvements in walking.

5. Knee Function Evaluation

The analysis of WOMAC in this study did not show any significant differences. Although there was no statistically significant difference, a comparison of WOMAC scores between the baseline and three months post-intervention among three groups showed a 53% reduction in CKCG, a 45% decrease in OKCG, and a 48% decrease in CG, indicating a relatively high reduction in CKCG compared to the other groups. The reason CKCG showed the greatest improvement is attributed to exercises based on daily activities such as sitting and standing up from a chair, climbing stairs, and walking sideways, which enhance joint proprioception in the knee, hip, and ankle joints [

32,

33] and led to improvements in daily life activities. The lack of significant difference in the WOMAC scores in the study may be attributed to subjective factors involved in completing the questionnaire, assistance from caregivers in completing the survey, and daily variations in condition. Therefore, considering the results of this and previous studies, it is expected that additional research will be required in the future.

6. Pain

No significant reduction in VAS score was observed in this study. However, when comparing the pre and post-intervention of the three groups, CKCG showed a decrease of 64%, OKCG decreased by 67%, and CG decreased by 42%. Compared to CKCG and OKCG, CG exhibited a lower reduction in pain intensity. This suggests that increased ROM, muscle strength, and functional movement in the exercise groups may have accelerated the reduction in pain intensity. The lack of significant difference may be because the exercise program could not be tailored to the pain level of each individual, and the muscle soreness experienced during exercise may have influenced the results..

5. Conclusions

Closed and open kinetic chain exercises for 12 weeks are effective in improving lower limb strength, ROM, Static and dynamic balance abilities in older women who underwent TKA. Closed kinetic chain exercises were particularly effective in enhancing knee extension strength and gait performance.

Author Contributions

MH Kim, KS Kim and KJ Kim reviewed the clinical datae. JA Sim conceived of the presented idea and reviewed paper in clinical aspect. MH Kim researched data and supported writing the paper. BH Lee oversaw this study and was the final approver of the overall review and manuscript writing. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Priority Research Centers Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF), funded by the Ministry of Education, Science, and Technology (2017R1A6A1A03015562), and supported by the Ministry of Trade, Industry, and Energy (MOTIE), Korea, under the “Infrastructure program for industrial innovation (reference number P0025775)” supervised by the Korea Institute for Advancement of Technology (KIAT). This work was supported by the Gachon University research fund of 2024 (GCU-202410300001).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study protocol was approved by Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Gachon University Hospital (IRB No: GDIRB2022-095), and the trial was registered with the Clinical Research Information Service (CRiS) of the Republic of Korea (CRiS Registration No. KCT0009533).

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent has been obtained from the patient(s) to publish this paper.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to acknowledge Corentec, an implant specialist company, for the technical guidance in accurate surgical technique associated with the device. The support did not influence the scientific content, results, or conclusions of this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors affirm that we have no financial affiliation (including research funding) or involvement with any commercial organization that has a direct financial interest in any matter included in this manuscript, except as disclosed and cited in the manuscript. Any other conflict of interest (i.e., personal associations or involvement as a director, officer, or expert witness) is also disclosed and cited in the manuscript.

Abbreviations

| ANCOVA |

Analysis of covariance |

| ANOVA |

A two-way analysis of variance |

| CKCG |

Closed kinetic chain exercises group |

| CT |

Computed Tomography |

| CG |

Control group |

| MRI |

Magnetic Resonance Imaging |

| OKCG |

Open kinetic chain exercises group |

| ROM |

Range of motion |

| RPE |

Rating of Perceived Exertion |

| 6MWT |

6-Minute Walk Test |

| TKA |

Total Knee Arthroplasty |

| TUG |

Time Up and Go |

| VAS |

Visual Analog Scale |

| WOMAC |

Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index |

References

- Crowninshield, R.D.; Rosenberg, A.G.; Sporer, S.M. Changing demographics of patients with total joint replacement. Clinical orthopaedics and related research 2006, 443, 266-272. [CrossRef]

- Levinger, P.; Menz, H.B.; Wee, E.; Feller, J.A.; Bartlett, J.R.; Bergman, N.R. Physiological risk factors for falls in people with knee osteoarthritis before and early after knee replacement surgery. Knee surgery, sports traumatology, arthroscopy : official journal of the ESSKA 2011, 19, 1082-1089. [CrossRef]

- Meier, W.; Mizner, R.L.; Marcus, R.L.; Dibble, L.E.; Peters, C.; Lastayo, P.C. Total knee arthroplasty: muscle impairments, functional limitations, and recommended rehabilitation approaches. The Journal of orthopaedic and sports physical therapy 2008, 38, 246-256. [CrossRef]

- Bade, M.J.; Kohrt, W.M.; Stevens-Lapsley, J.E. Outcomes before and after total knee arthroplasty compared to healthy adults. The Journal of orthopaedic and sports physical therapy 2010, 40, 559-567. [CrossRef]

- Yun, J.Y.; Lee, J.K. [Effects of a Thera-Band Exercise Program on Pain, Knee Flexion ROM, and Psychological Parameters Following Total Knee Arthroplasty]. Journal of Korean Academy of Nursing 2015, 45, 823-833. [CrossRef]

- Pozzi, F.; Snyder-Mackler, L.; Zeni, J. Physical exercise after knee arthroplasty: a systematic review of controlled trials. European journal of physical and rehabilitation medicine 2013, 49, 877-892.

- Kwon, Y.J.; Park, S.J.; Jefferson, J.; Kim, K. The effect of open and closed kinetic chain exercises on dynamic balance ability of normal healthy adults. Journal of physical therapy science 2013, 25, 671-674. [CrossRef]

- Abbas, C.; Daher, J. Pilot study: Post-operative rehabilitation pathway changes and implementation of functional closed kinetic chain exercise in total hip and total knee replacement patient. Journal of bodywork and movement therapies 2017, 21, 823-829. [CrossRef]

- Olagbegi, O.M.; Adegoke, B.O.; Odole, A.C. Effectiveness of three modes of kinetic-chain exercises on quadriceps muscle strength and thigh girth among individuals with knee osteoarthritis. Archives of physiotherapy 2017, 7, 9. [CrossRef]

- Thonga, T.; Stasi, S.; Papathanasiou, G. The Effect of Intensive Close-Kinetic-Chain Exercises on Functionality and Balance Confidence After Total Knee Arthroplasty. Cureus 2021, 13, e18965. [CrossRef]

- Bohannon, R.W. Test-retest reliability of hand-held dynamometry during a single session of strength assessment. Physical therapy 1986, 66, 206-209. [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.S.; Yun, D.H.; Yoo, S.D.; Kim, D.H.; Jeong, Y.S.; Yun, J.S.; Hwang, D.G.; Jung, P.K.; Choi, S.H. Balance control and knee osteoarthritis severity. Annals of rehabilitation medicine 2011, 35, 701-709. [CrossRef]

- Ghislieri, M.; Knaflitz, M.; Labanca, L.; Barone, G.; Bragonzoni, L.; Benedetti, M.G.; Agostini, V. Muscle Synergy Assessment During Single-Leg Stance. IEEE transactions on neural systems and rehabilitation engineering : a publication of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society 2020, 28, 2914-2922. [CrossRef]

- Boonstra, M.C.; De Waal Malefijt, M.C.; Verdonschot, N. How to quantify knee function after total knee arthroplasty? The Knee 2008, 15, 390-395. [CrossRef]

- Botolfsen, P.; Helbostad, J.L.; Moe-Nilssen, R.; Wall, J.C. Reliability and concurrent validity of the Expanded Timed Up-and-Go test in older people with impaired mobility. Physiotherapy research international : the journal for researchers and clinicians in physical therapy 2008, 13, 94-106. [CrossRef]

- Nordin, E.; Rosendahl, E.; Lundin-Olsson, L. Timed "Up & Go" test: reliability in older people dependent in activities of daily living--focus on cognitive state. Physical therapy 2006, 86, 646-655.

- Crosbie, J.; Naylor, J.M.; Harmer, A.R. Six minute walk distance or stair negotiation? Choice of activity assessment following total knee replacement. Physiotherapy research international : the journal for researchers and clinicians in physical therapy 2010, 15, 35-41. [CrossRef]

- Valenzuela, P.L.; Martín-Candilejo, R.; Sánchez-Martínez, G.; Bouzas Marins, J.C.; de la Villa, P.; Sillero-Quintana, M. Ischemic Preconditioning and Muscle Force Capabilities. Journal of strength and conditioning research 2021, 35, 2187-2192. [CrossRef]

- Furu, M.; Ito, H.; Nishikawa, T.; Nankaku, M.; Kuriyama, S.; Ishikawa, M.; Nakamura, S.; Azukizawa, M.; Hamamoto, Y.; Matsuda, S. Quadriceps strength affects patient satisfaction after total knee arthroplasty. Journal of orthopaedic science : official journal of the Japanese Orthopaedic Association 2016, 21, 38-43. [CrossRef]

- Basques, B.A.; Bell, J.A.; Sershon, R.A.; Della Valle, C.J. The Influence of Patient Gender on Morbidity Following Total Hip or Total Knee Arthroplasty. The Journal of arthroplasty 2018, 33, 345-349. [CrossRef]

- Jacobs, H.; Seeber, G.H.; Allers, K.; Hoffmann, F. Utilisation of outpatient physiotherapy in patients following total knee arthroplasty - a systematic review. BMC musculoskeletal disorders 2021, 22, 711. [CrossRef]

- Labraca, N.S.; Castro-Sánchez, A.M.; Matarán-Peñarrocha, G.A.; Arroyo-Morales, M.; Sánchez-Joya Mdel, M.; Moreno-Lorenzo, C. Benefits of starting rehabilitation within 24 hours of primary total knee arthroplasty: randomized clinical trial. Clinical rehabilitation 2011, 25, 557-566. [CrossRef]

- Hsu, W.H.; Hsu, W.B.; Shen, W.J.; Lin, Z.R.; Chang, S.H.; Hsu, R.W. Twenty-four-week hospital-based progressive resistance training on functional recovery in female patients post total knee arthroplasty. The Knee 2019, 26, 729-736. [CrossRef]

- Scott, C.E.; Bugler, K.E.; Clement, N.D.; MacDonald, D.; Howie, C.R.; Biant, L.C. Patient expectations of arthroplasty of the hip and knee. The Journal of bone and joint surgery. British volume 2012, 94, 974-981. [CrossRef]

- Knoop, J.; Steultjens, M.P.; van der Leeden, M.; van der Esch, M.; Thorstensson, C.A.; Roorda, L.D.; Lems, W.F.; Dekker, J. Proprioception in knee osteoarthritis: a narrative review. Osteoarthritis and cartilage 2011, 19, 381-388. [CrossRef]

- Rätsepsoo, M.; Gapeyeva, H.; Sokk, J.; Ereline, J.; Haviko, T.; Pääsuke, M. Leg extensor muscle strength, postural stability, and fear of falling after a 2-month home exercise program in women with severe knee joint osteoarthritis. Medicina (Kaunas, Lithuania) 2013, 49, 347-353.

- Steultjens, M.P.; Dekker, J.; van Baar, M.E.; Oostendorp, R.A.; Bijlsma, J.W. Range of joint motion and disability in patients with osteoarthritis of the knee or hip. Rheumatology (Oxford, England) 2000, 39, 955-961. [CrossRef]

- Lee, T.Q. Biomechanics of hyperflexion and kneeling before and after total knee arthroplasty. Clinics in orthopedic surgery 2014, 6, 117-126. [CrossRef]

- Astephen, J.L.; Deluzio, K.J.; Caldwell, G.E.; Dunbar, M.J. Biomechanical changes at the hip, knee, and ankle joints during gait are associated with knee osteoarthritis severity. Journal of orthopaedic research : official publication of the Orthopaedic Research Society 2008, 26, 332-341. [CrossRef]

- Kaufman, K.R.; Hughes, C.; Morrey, B.F.; Morrey, M.; An, K.N. Gait characteristics of patients with knee osteoarthritis. Journal of biomechanics 2001, 34, 907-915. [CrossRef]

- Fantozzi, S.; Benedetti, M.G.; Leardini, A.; Banks, S.A.; Cappello, A.; Assirelli, D.; Catani, F. Fluoroscopic and gait analysis of the functional performance in stair ascent of two total knee replacement designs. Gait & posture 2003, 17, 225-234. [CrossRef]

- Jadelis, K.; Miller, M.E.; Ettinger, W.H., Jr.; Messier, S.P. Strength, balance, and the modifying effects of obesity and knee pain: results from the Observational Arthritis Study in Seniors (oasis). Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 2001, 49, 884-891. [CrossRef]

- Moutzouri, M.; Gleeson, N.; Billis, E.; Panoutsopoulou, I.; Gliatis, J. What is the effect of sensori-motor training on functional outcome and balance performance of patients' undergoing TKR? A systematic review. Physiotherapy 2016, 102, 136-144. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).