Submitted:

24 July 2025

Posted:

25 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Related Work

| Author | Method | Pros | Cons | Gap |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| [31] | ML Survey in CRN, LTE-U | Broad taxonomy; highlights ML potential | Lacks validation; general scope | Need robust ML vs. PUE, SSDF attacks |

| [32] | Multi-scenario ML sharing | Better incentives; fewer collisions | No implementation constraints discussed | Lack of real-world scalability eval |

| [33] | ML (SVM, KNN, RF) for IIoT/IoMT | Higher accuracy; fewer false positives | Missing deployment context | Need deployment analysis for IIoT/IoMT |

| [34] | MLP, SVM, NB vs. detection | MLP balances speed and accuracy | No robustness/scalability analysis | Evaluate in mobile/adversarial settings |

| [35] | DRL for secure sharing | Boosts utilization; security-aware | Theoretical; lacks empirical proof | Empirical DRL-based secure sharing needed |

| [36] | Margin-based online learning | Adapts with minimal labels | Simulation-only; no field test | Real PU behavior-responsive models needed |

| [37] | PPO for RIS in V2X | Fast convergence; better sum-rate | No dense urban/blockage analysis | Test PPO-RIS in obstructed settings |

| [38] | MAPPO for HetNet offloading | Efficient, scalable BS deployment | Multi-agent training complexity ignored | Study MAPPO fairness/scalability under noise |

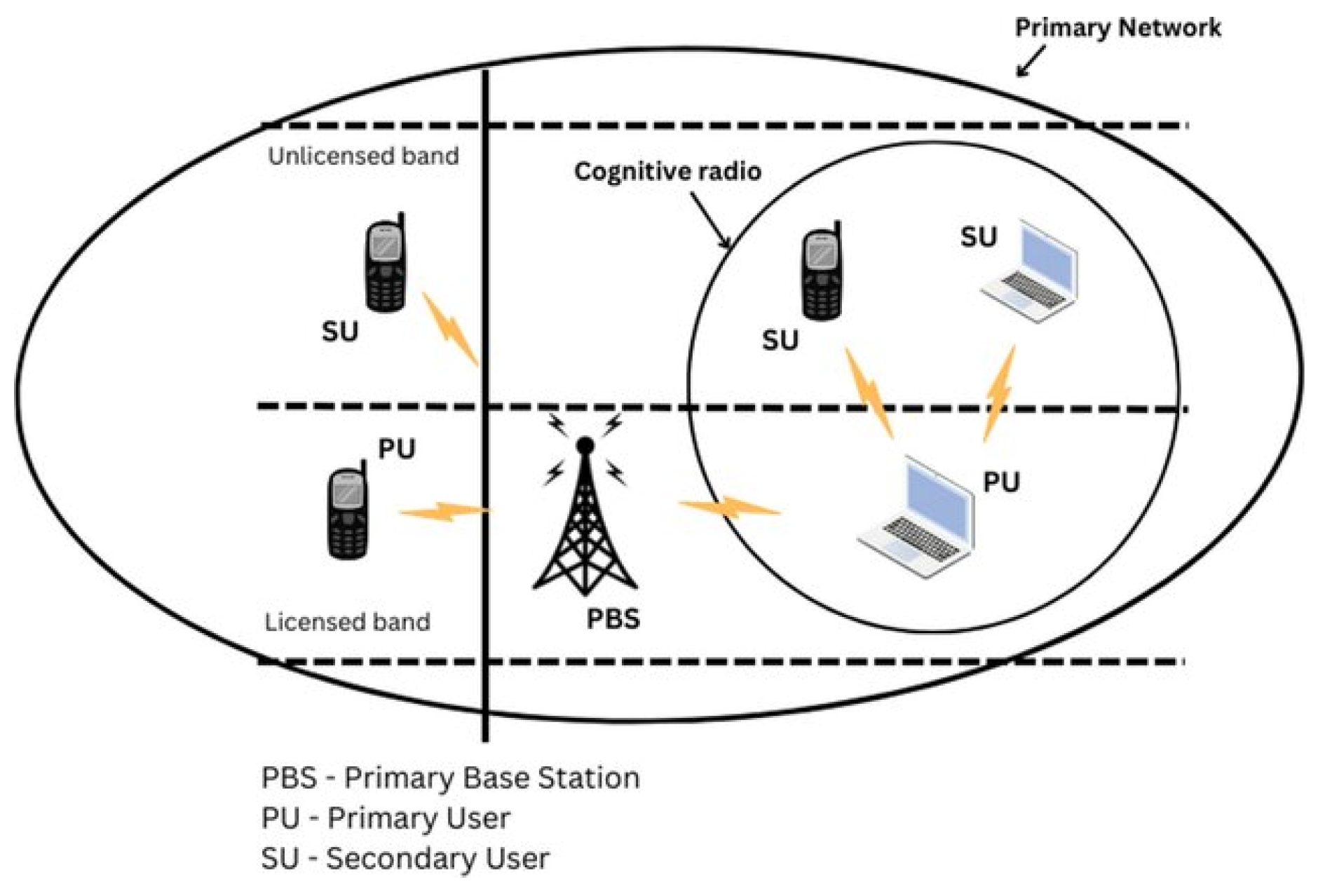

3. System Model

3.1. Multi-Objective Optimisation Problem Formulation

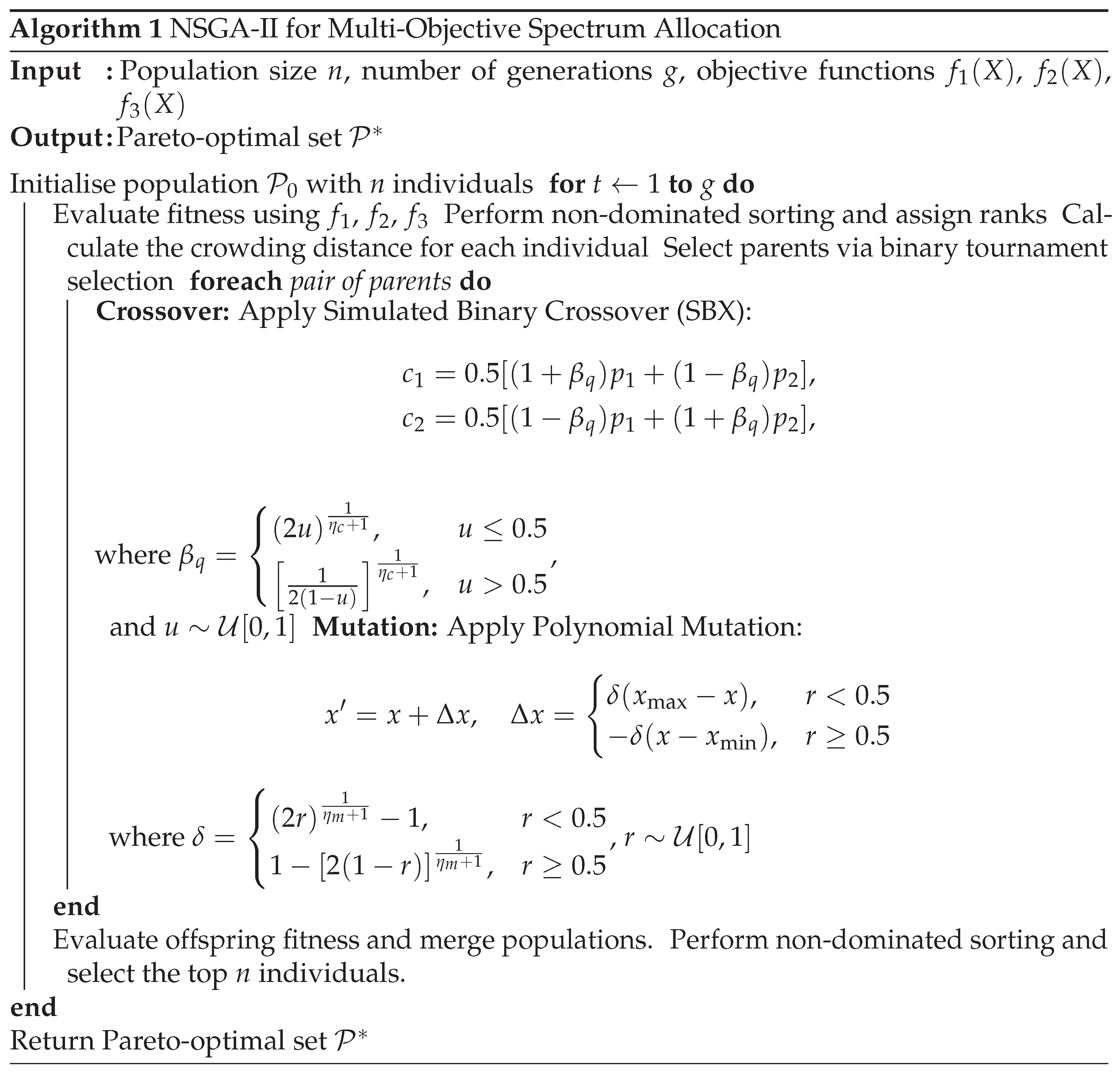

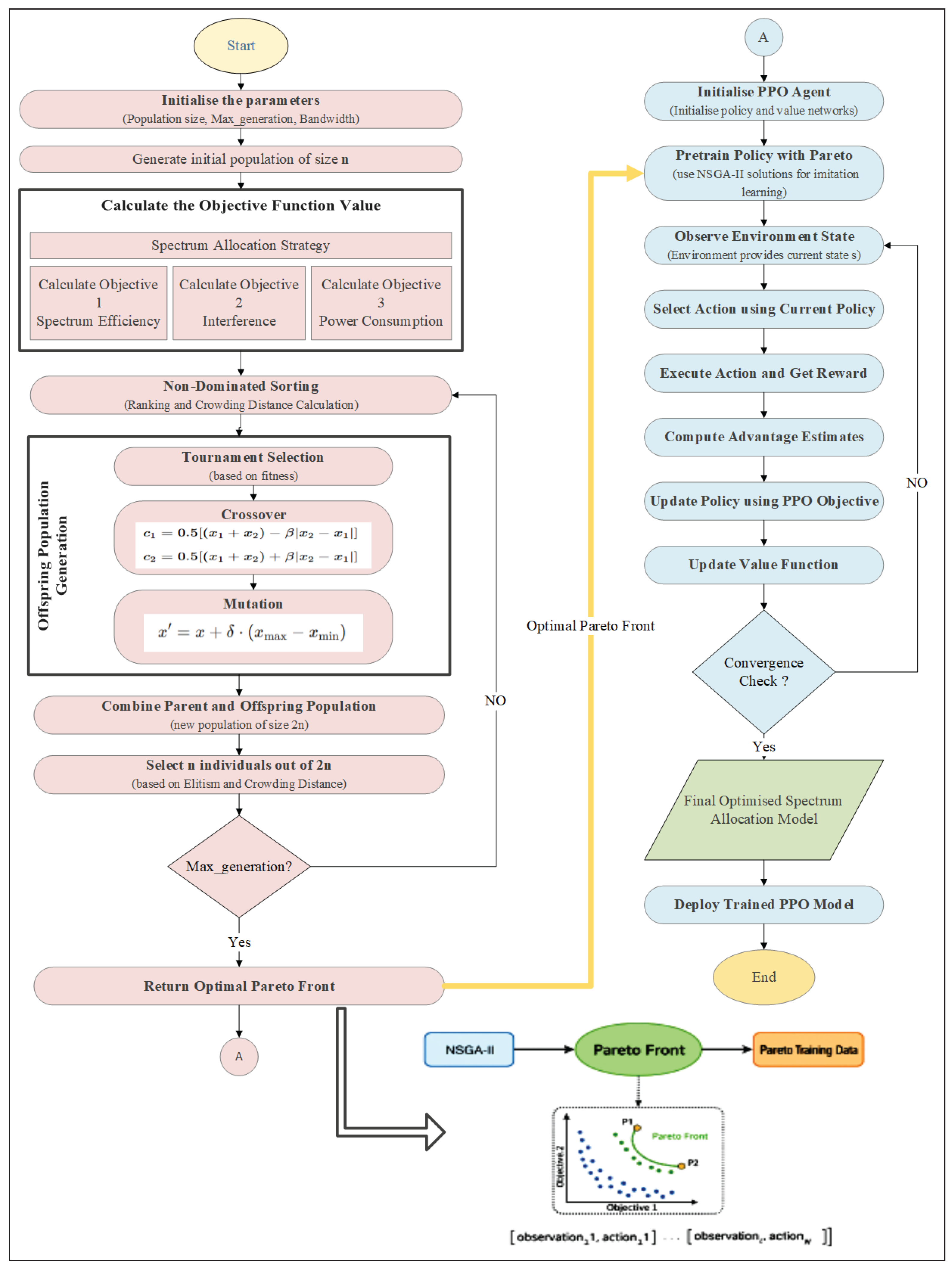

3.2. Hybrid NSGA-II + PPO Framework

- NSGA-II( Evolutionary Search Complexity): Population Dynamics: NSGA-II operates over multiple generations with a sizable population, demanding repeated evaluations of each individual across all objectives. This gives rise to complexity for non-dominated sorting, where n is the population size and M is the number of objectives.

- PPO- Reinforcement Learning Stability: In algorithm ?? policy training leverages Pareto-optimal solutions to bootstrap PPO adds a front-loaded cost due to imitation learning over diverse-action pairs.

4. Evaluation

4.1. Experimental Setup

- Dataset description: Experiments utilised a composite dataset comprising approximately 15,000 samples generated from a Python-based spectrum simulator and the ns-3 network simulator to reflect both synthetic and realistic CRN behaviours.

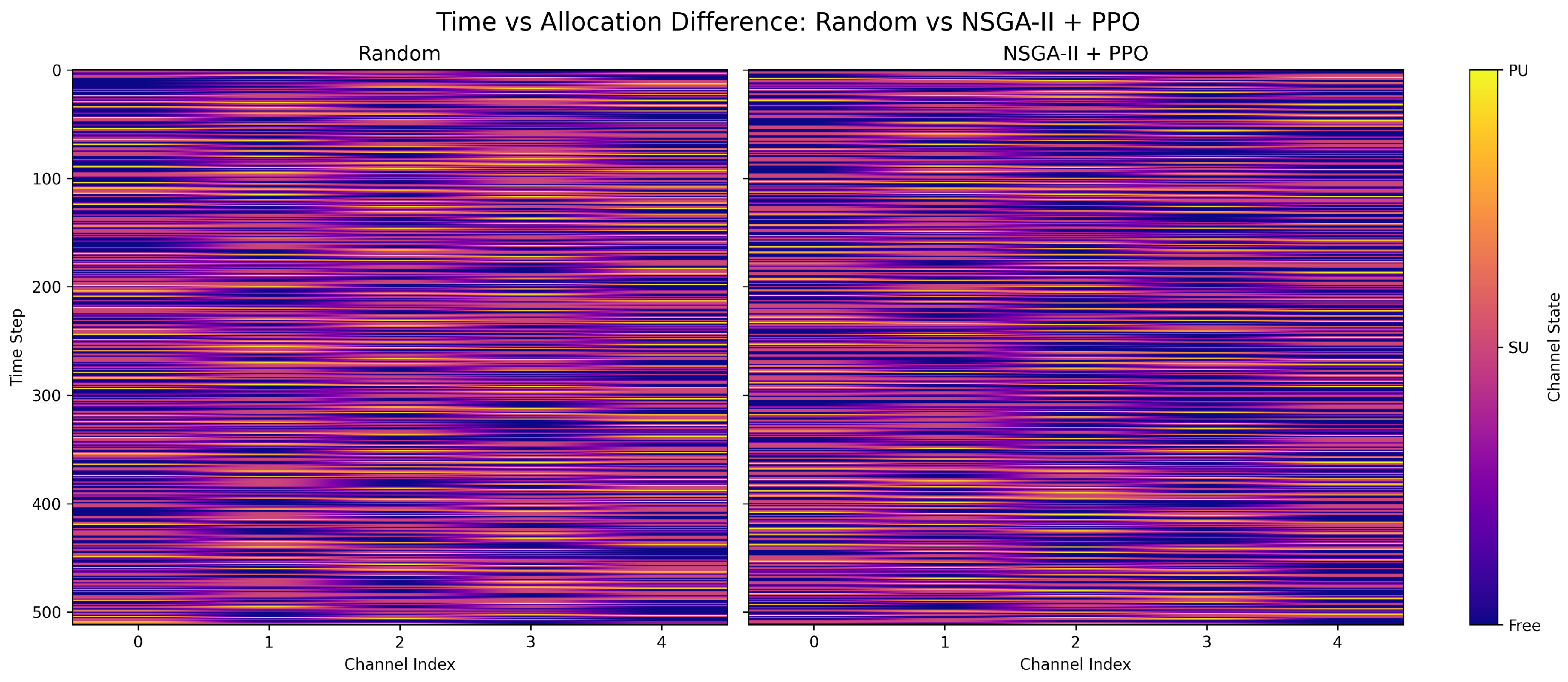

- Generation: The synthetic dataset was generated using a customised Python script to evaluate the proposed model. Each record represents a discrete time slot where three secondary users (Sus) contend for access to five spectrum channels, with the quantity of channels being equivalent to the quantity of primary users (PUs), under varying spatial and interference conditions. The dataset captures PU and SU coordinates, PU activity states, SU access requests, transmission power levels, channel gains, SINR, and interference levels. By modelling diverse network topologies, PU activity patterns, and SU request, it reflects the stochastic spectrum usage of 6G cognitive radio networks, enabling the GA-DRL framework to learn allocation strategies that optimise throughput, mitigate interference, and ensure fairness. The dataset was stored in csv format. Dataset parameters included PU activity, SU requests, SINR, interference levels, channel gain, transmit power, throughput, and energy consumption.

- Training: Training and evaluation were performed using Google Colab Pro with NVIDIA T4 GPUs, leveraging PyTorch for PPO and custom Python implementations for NSGA-II. The environment simulated sub-6 GHz operation across five channels, with dynamic primary and secondary user interactions modelled per time slot. The evaluation consisted of 30 independent episodes of 512 steps each, following 30,000 PPO training timesteps. Baseline comparisons included Random allocation, Greedy heuristics, and standalone PPO. Key hyperparameters are summarised in Table 3.

4.2. Results and Analysis

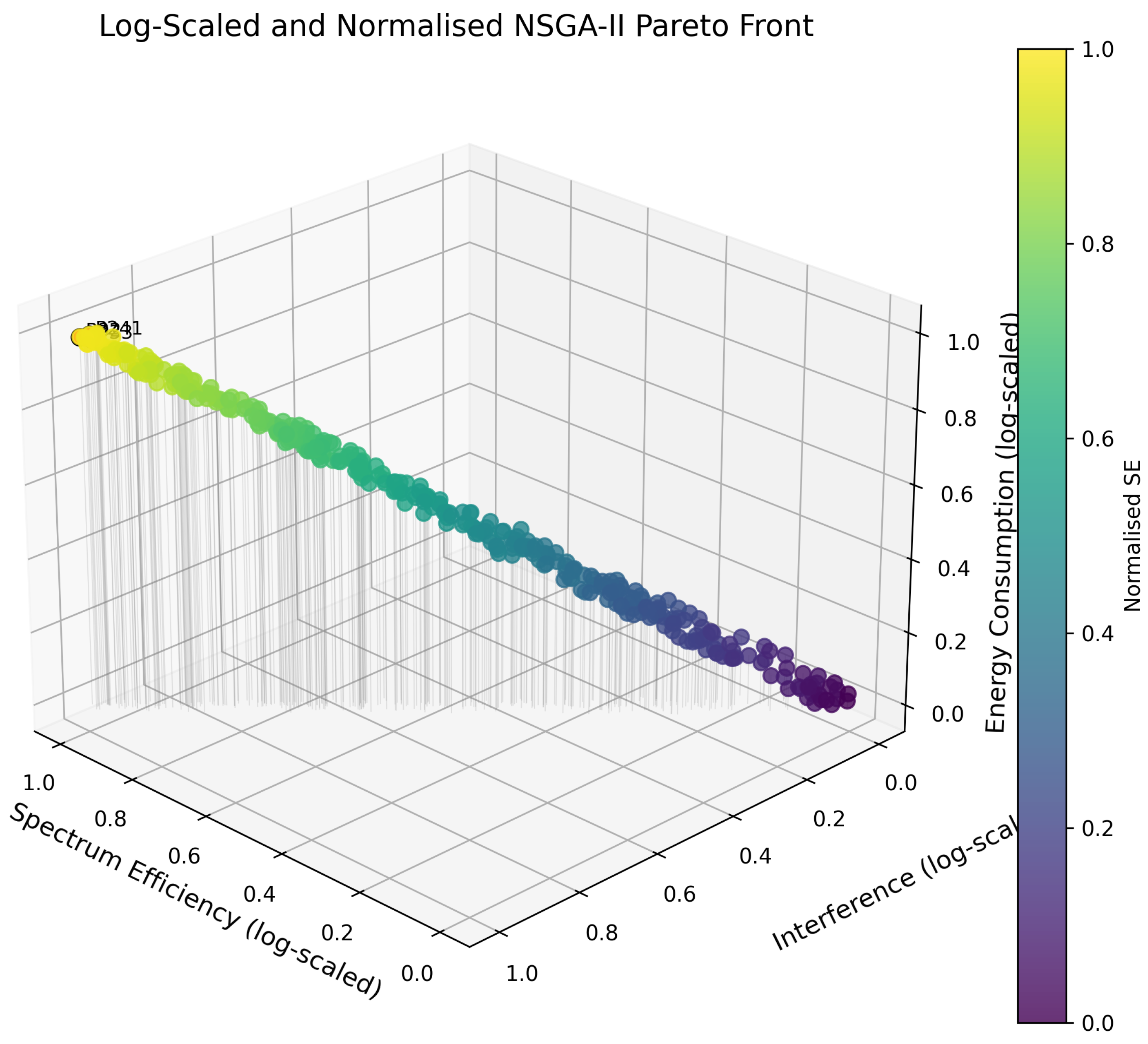

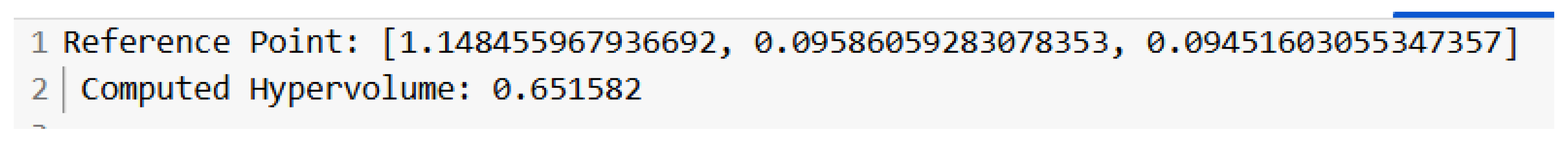

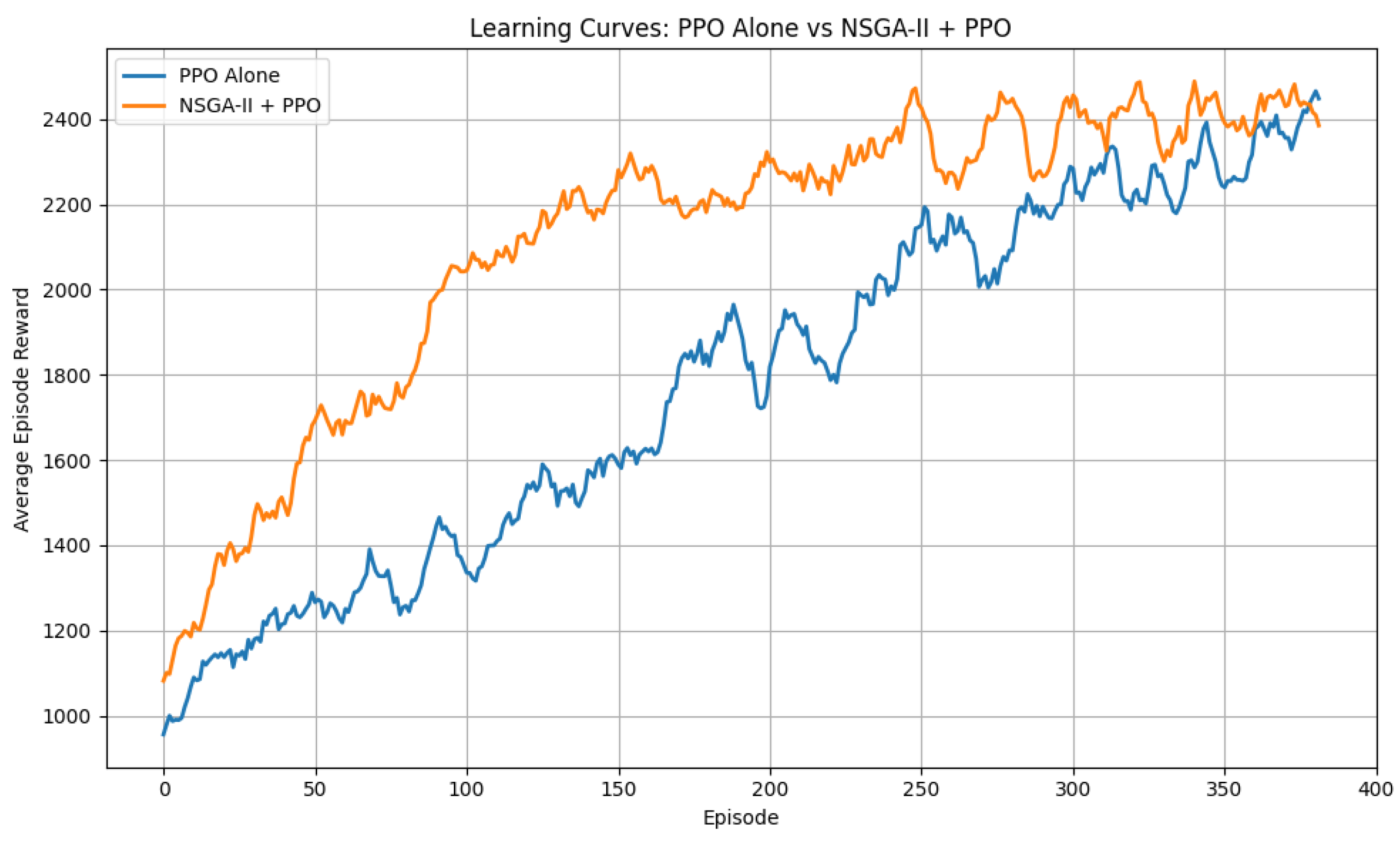

4.2.1. Convergence and Multi-Objective Optimisation

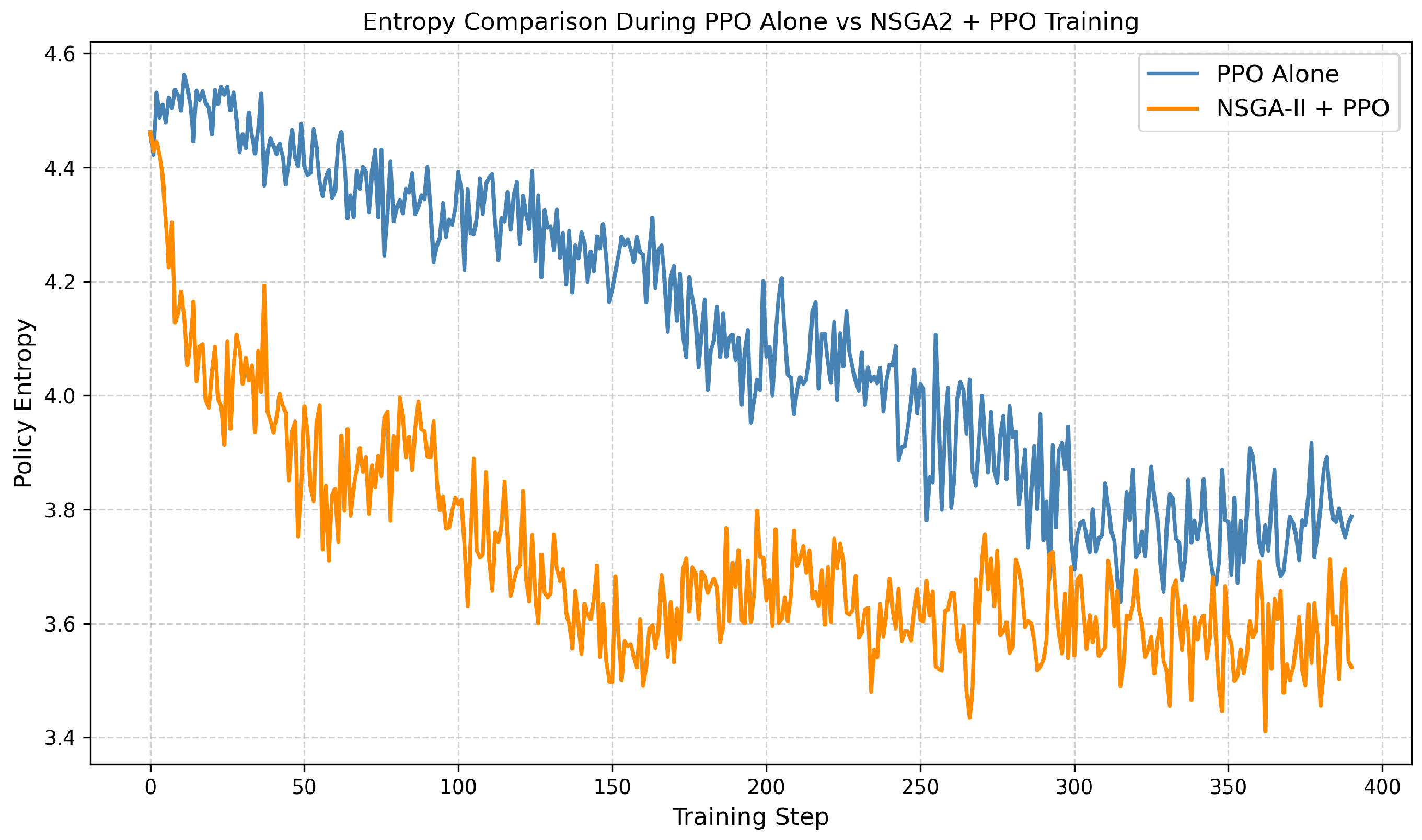

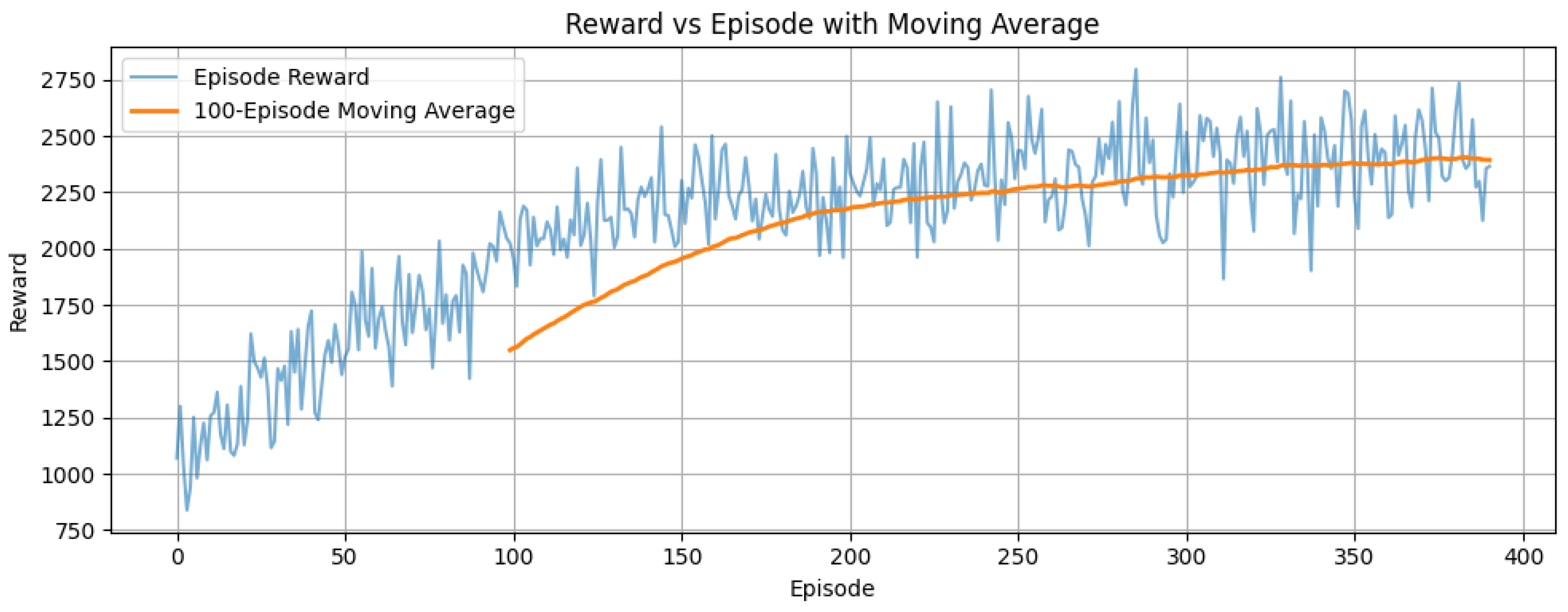

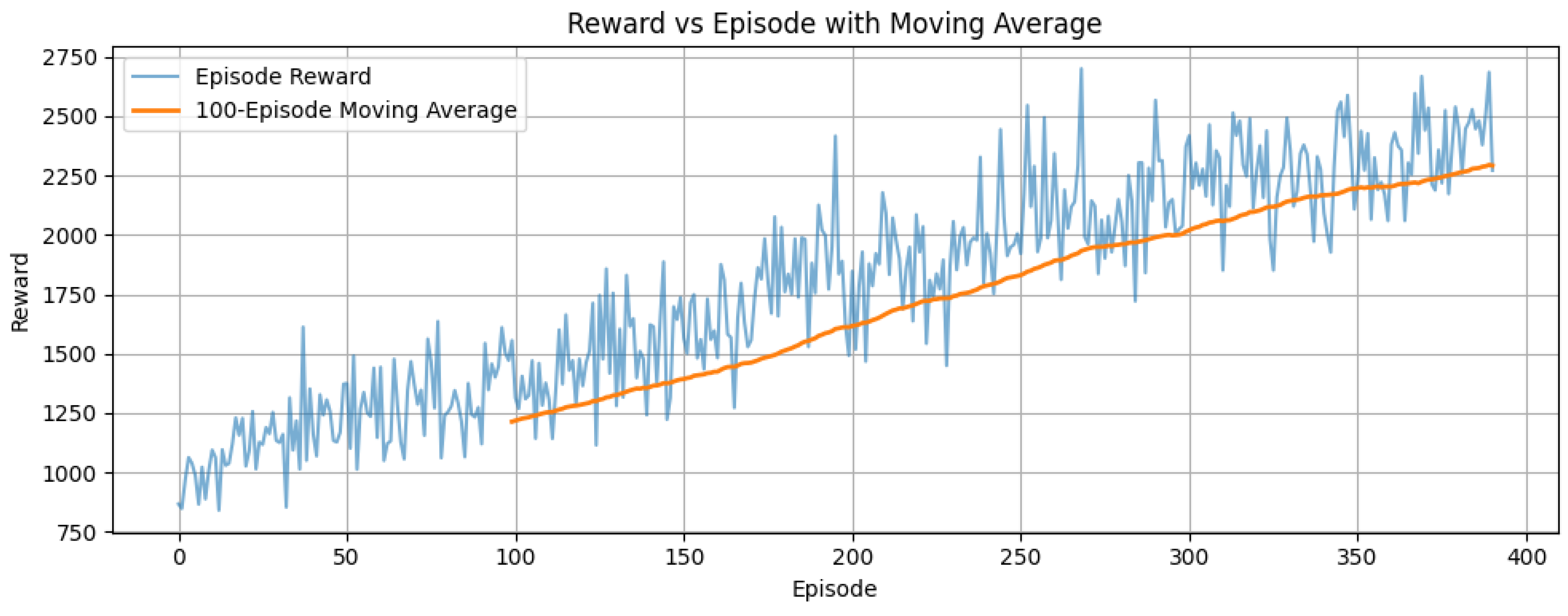

4.2.2. Learning Behaviour and Policy Stability

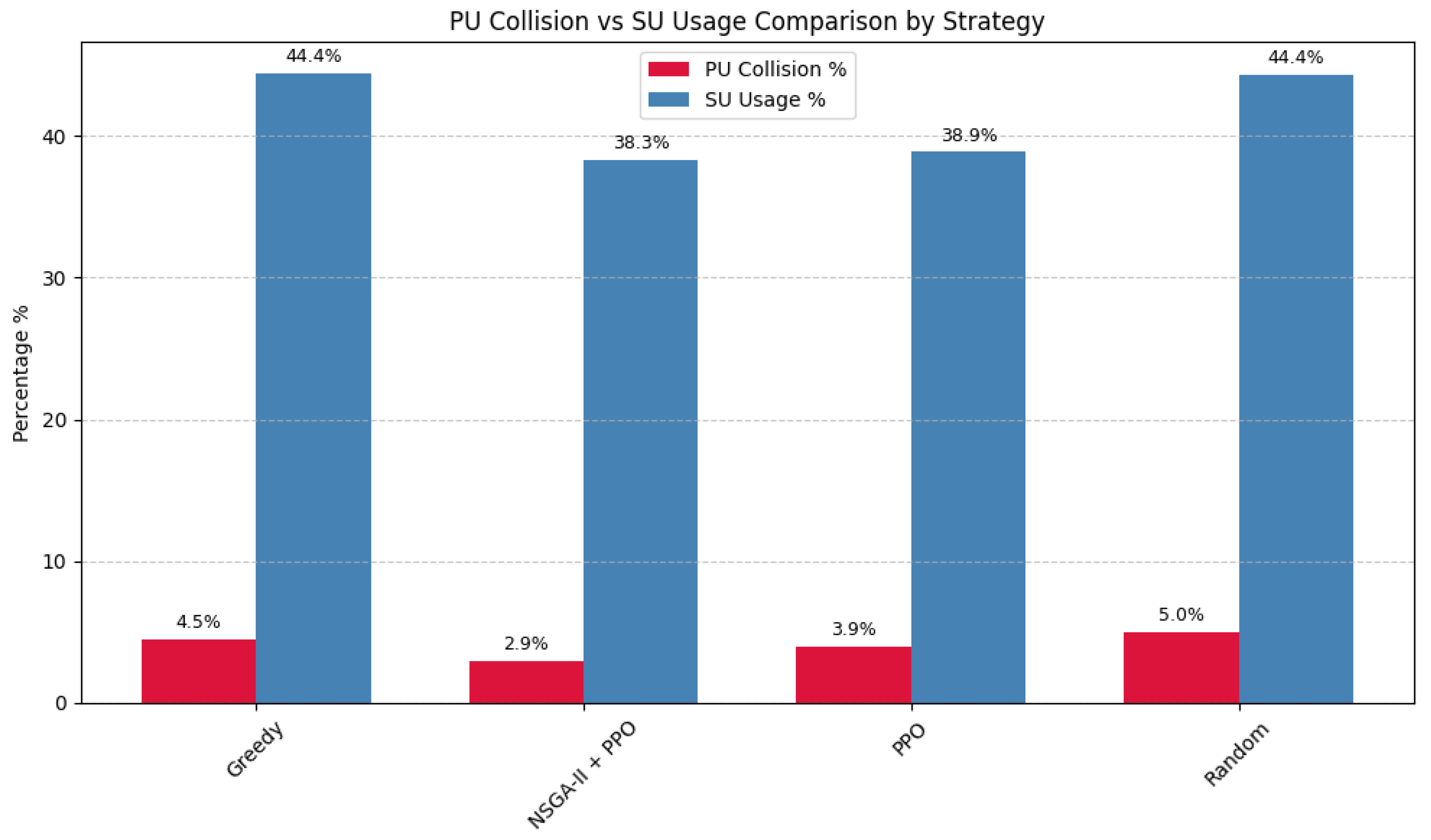

4.2.3. Performance Comparison

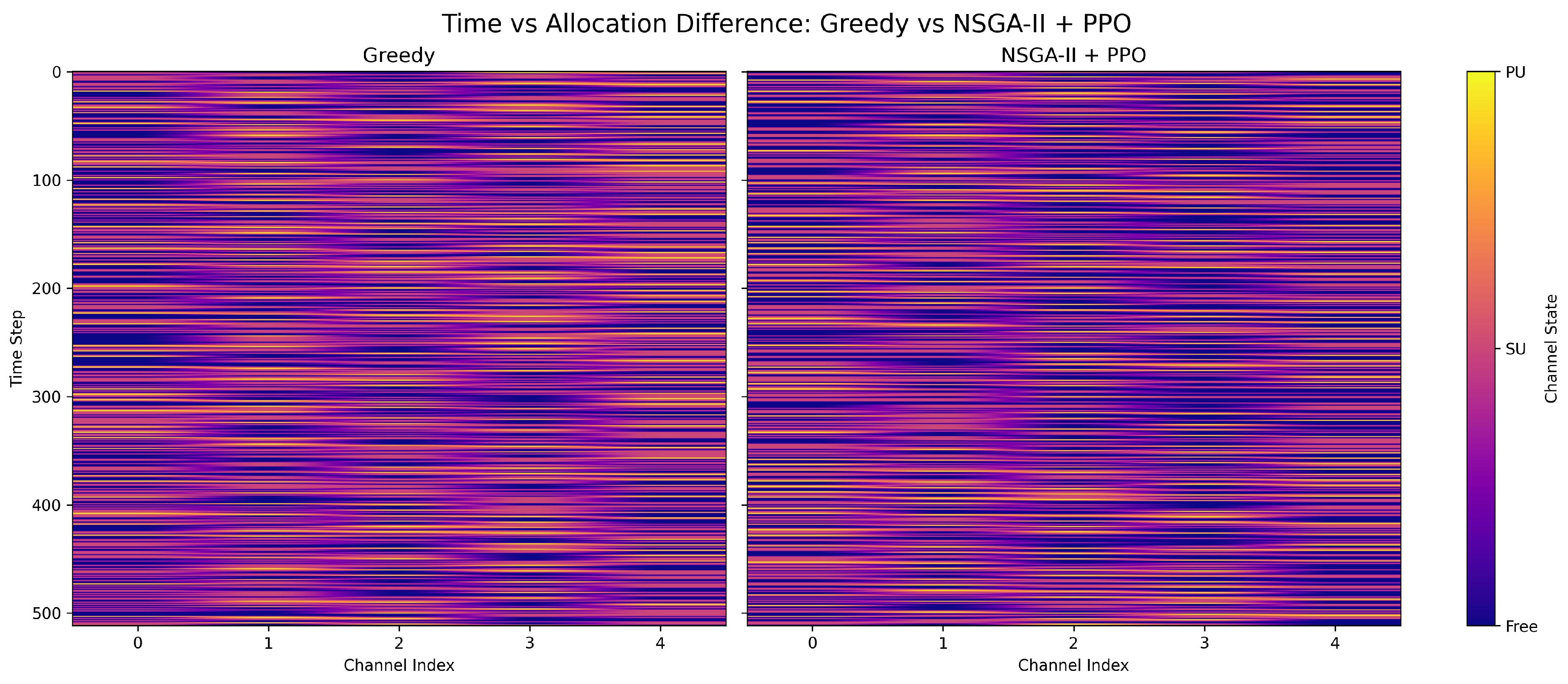

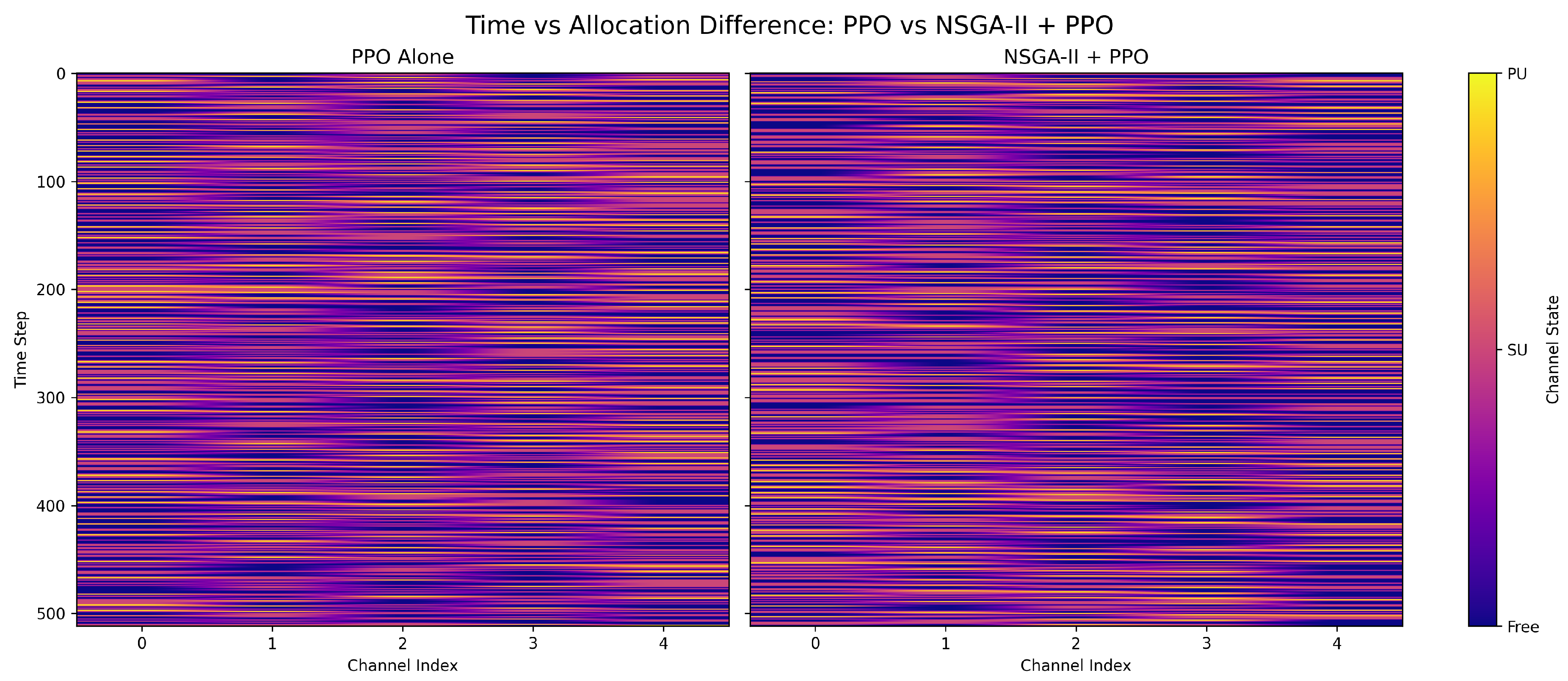

4.2.4. Channel Usage and Fairness

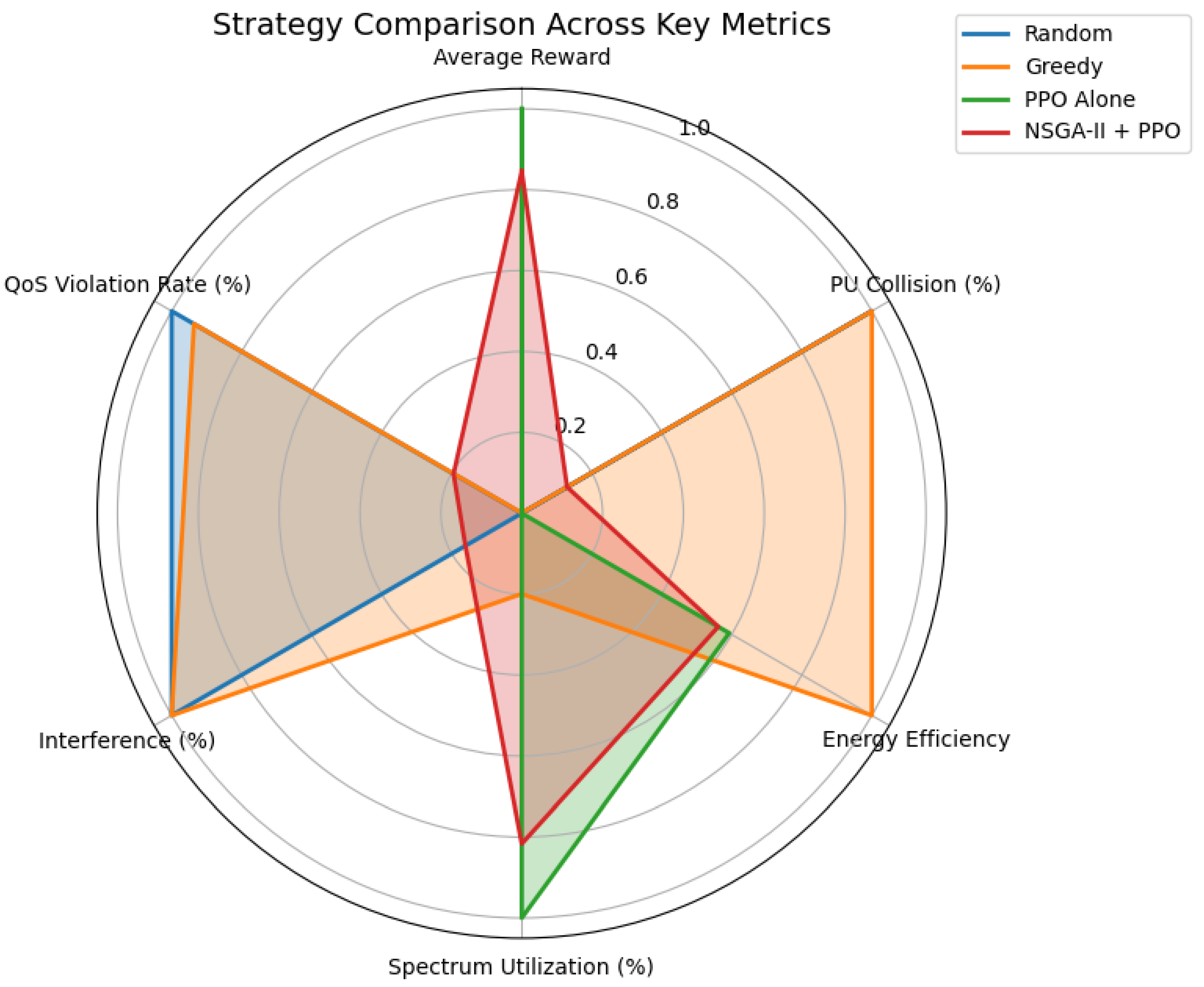

4.2.5. Multi-Metric Visualisation

4.3. Discussion

4.4. Limitations and Future Work

5. Conclusions

Abbreviations

| 6G | Sixth Generation |

| CRN | Cognitive Radio Network |

| NSGA-II | Non-dominated Sorting Genetic Algorithm II |

| PPO | Proximal Policy Optimization |

| IoE | Internet of Everything |

| HT | Holographic Telepresence |

| UAV | Unmanned Aerial Vehicle |

| XR | Extended Reality |

| NTN | Non-Terrestrial Network |

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| ML | Machine Learning |

| QoS | Quality of Service |

| PU | Primary User |

| SU | Secondary User |

| SINR | Signal-to-Interference-plus-Noise Ratio |

| DSA | Dynamic Spectrum Access |

| NOMA | Non-Orthogonal Multiple Access |

| DRL | Deep Reinforcement Learning |

| MADDPG | Multi-Agent Deep Deterministic Policy Gradient |

| MAPPO | Multi-Agent Proximal Policy Optimization |

| RIS | Reconfigurable Intelligent Surface |

| MIMO | Multiple Input Multiple Output |

| D2D | Device-to-Device |

| IoT | Internet of Things |

| CSI | Channel State Information |

| MLP | Multi-Layer Perceptron |

| SVM | Support Vector Machine |

| KNN | K-Nearest Neighbors |

| RF | Random Forest |

| NB | Naive Bayes |

| IIoT | Industrial Internet of Things |

| IoMT | Internet of Medical Things |

References

- Huawei. 6G: The Next Horizon White Paper. Technical report, Huawei, 2022. Accessed on June 16, 2025.

- De Alwis, C.; Kalla, A.; Pham, Q.V.; Kumar, P.; Dev, K.; Hwang, W.J.; Liyanage, M. Survey on 6G frontiers: Trends, applications, requirements, technologies and future research. IEEE Open Journal of the Communications Society 2021, 2, 836–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nleya, S.M.; Velempini, M.; Gotora, T.T. Beyond 5G: The Evolution of Wireless Networks and Their Impact on Society. In Advanced Wireless Communications and Mobile Networks-Current Status and Future Directions; IntechOpen, 2025.

- Hassan, I.M.; Maijama’a, I.S.; Adamu, A.; Abubakar, S.B. Exploring the Social and Economic Impacts of 6G Networks and Their Potential Benefits to Society. International Journal of Science, Engineering and Technology 2025, 13. Open Access under Creative Commons Attribution License. [Google Scholar]

- Bhadoriya, R.; Garg, N.K.; Dadoria, A.K. Chapter 18 - Future opportunities toward importance of emerging technologies with 6G technology. In Human-Centric Integration of 6G-Enabled Technologies for Modern Society; Tyagi, A.K.; Tiwari, S., Eds.; Academic Press, 2025; pp. 267–281.

- ITU-R. IMT Traffic Estimates for the Years 2020 to 2030. Technical report, International Telecommunication Union (ITU), 2015. Report M.2370-0.

- Ahmed, M.; Waqqas, F.; Fatima, M.; Khan, A.M.; Naz, M.A.; Ahmed, M. Enabling 6G Networks for Advances Challenges and Traffic Engineering for Future Connectivity. VFAST Transactions on Software Engineering 2024, 12, 326–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akbar, M.S.; Hussain, Z.; Ikram, M.; Sheng, Q.Z.; Mukhopadhyay, S. On challenges of sixth-generation (6G) wireless networks: A comprehensive survey of requirements, applications, and security issues. Journal of Network and Computer Applications 2024, 233, 104040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- E-SPIN Group. Next 6G: Key Features, Use Cases, and Challenges of Tomorrow’s Wireless Revolution. https://www.e-spincorp.com/blogs/next-6g-key-features-use-cases-and-challenges-of-tomorrows-wireless-revolution/, 2023. Accessed: [Date Accessed, e.g., 2025-06-18].

- Sabir, B.; Yang, S.; Nguyen, D.; Wu, N.; Abuadbba, A.; Suzuki, H.; Lai, S.; Ni, W.; Ming, D.; Nepal, S. Systematic Literature Review of AI-enabled Spectrum Management in 6G and Future Networks. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2407.10981. [Google Scholar]

- Ghafoor, U.; Siddiqui, A.M. Enhancing 6G Network Security Through Cognitive Radio and Cluster-Assisted Downlink Hybrid Multiple Access. In Proceedings of the 2024 International Conference on Frontiers of Information Technology (FIT). IEEE, 2024, pp. 1–6.

- Saravanan, K.; Jaikumar, R.; Devaraj, S.A.; Kumar, O.P. Connected map-induced resource allocation scheme for cognitive radio network quality of service maximization. Scientific Reports 2025, 15, 14037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Digital Regulation Platform. Spectrum management: Key applications and regulatory considerations driving the future use of spectrum. Digital Regulation Platform 2025.

- Ericsson. 6G - Follow the journey to the next generation networks. https://www.ericsson.com/en/5g/6g, 2024. Accessed: June 17, 2025.

- Mukherjee, A.; Patro, S.; Geyer, J.; Kumar, S.; Paikrao, P.D. The Convergence of Cognitive Radio and 6G: Opportunities, Applications, and Technical Considerations. In Proceedings of the 2025 8th International Conference on Electronics, Materials Engineering & Nano-Technology (IEMENTech). IEEE; 2025; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Jagatheesaperumal, S.K.; Ahmad, I.; Höyhtyä, M.; Khan, S.; Gurtov, A. Deep learning frameworks for cognitive radio networks: Review and open research challenges. Journal of Network and Computer Applications 2024, 104051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samsung Electronics. AI-Native & Sustainable Communication. White paper, Samsung, 2025. 15 June 2025.

- NVIDIA. NVIDIA and Telecom Industry Leaders to Develop AI-Native Wireless Networks for 6G. https://nvidianews.nvidia.com/news/nvidia-and-telecom-industry-leaders-to-develop-ai-native-wireless-networks-for-6g, 2025. Accessed: 16 June 2025.

- You, X. 6G extreme connectivity via exploring spatiotemporal exchangeability. Science China Information Sciences 2023, 66, 130306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uusitalo, M.A.; Rugeland, P.; Boldi, M.R.; Calvanese Strinati, E.; Demestichas, P.; Ericson, M.; Fettweis, G.P.; Filippou, M.C.; Gati, A.; Hamon, M.H.; et al. 6G Vision, Value, Use Cases and Technologies from European 6G Flagship Project Hexa-X. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 160004–160020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ericsson. 6G Use cases: Beyond communication by 2030. Ericsson White Paper 2021.

- Fu, Y.; Wang, X.; Fang, F. Multi-objective multi-dimensional resource allocation for categorized QoS provisioning in beyond 5G and 6G radio access networks. IEEE Transactions on Communications 2023, 72, 1790–1803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lozano, A.; Rangan, S. Spectral versus energy efficiency in 6G: Impact of the receiver front-end. IEEE BITS the Information Theory Magazine 2023, 3, 41–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semba Yawada, P.; Trung Dong, M. Tradeoff analysis between spectral and energy efficiency based on sub-channel activity index in wireless cognitive radio networks. Information 2018, 9, 323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.P.; Kumar, N.; Kumar, G.; Balusamy, B.; Bashir, A.K.; Al-Otaibi, Y.D. A hybrid multi-objective optimisation for 6G-enabled Internet of Things (IoT). IEEE Transactions on Consumer Electronics 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Sarah Lee. Optimizing Networks with Multiple Objectives. https://www.numberanalytics.com/blog/optimizing-networks-with-multiple-objectives, 2025. Accessed: 2025-07-02.

- Liu, D.; Shi, G.; Hirayama, K. Vessel scheduling optimization model based on variable speed in a seaport with one-way navigation channel. Sensors 2021, 21, 5478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pattanaik, A.; Ahmed, Z.; et al. Exploring Spectrum Sharing Algorithms for 6G Cellular Communication Networks. In Proceedings of the 2024 15th International Conference on Computing Communication and Networking Technologies (ICCCNT). IEEE; 2024; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Ndiaye, M.; Saley, A.M.; Raimy, A.; Niane, K. Spectrum resource sharing methodology based on CR-NOMA on the future integrated 6G and satellite network: Principle and Open researches. In Proceedings of the 2022 International Conference on Smart Technologies and Systems for Next Generation Computing (ICSTSN). IEEE; 2022; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, X.; Lam, K.Y.; Li, F.; Zhao, J.; Wang, L.; Durrani, T.S. Spectrum sharing for 6G integrated satellite-terrestrial communication networks based on NOMA and CR. IEEE Network 2021, 35, 28–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Sun, H.; Hu, R.Q.; Bhuyan, A. When machine learning meets spectrum sharing security: Methodologies and challenges. IEEE Open Journal of the Communications Society 2022, 3, 176–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frahan, N.; Jawed, S. Dynamics Spectrum Sharing Environment Using Deep Learning Techniques. European Journal of theoretical and Applied Sciences 2023, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahmoud, H.; Baiyekusi, T.; Daraz, U.; Mi, D.; He, Z.; Lu, C.; Guan, M.; Wang, Z.; Chen, F. Machine Learning-based Spectrum Allocation using Cognitive Radio Networks. In Proceedings of the 2024 International Joint Conference on Neural Networks (IJCNN). IEEE; 2024; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Tavares, C.H.A.; Marinello, J.C.; Proenca Jr, M.L.; Abrao, T. Machine learning-based models for spectrum sensing in cooperative radio networks. IET Communications 2020, 14, 3102–3109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Hu, R.Q.; Qian, Y. Secure Spectrum Sharing with Machine Learning: An Overview. In 5G and Beyond Wireless Communication Networks; Wiley-IEEE Press, 2024; pp. 115–134.

- Praveen Kumar, K.; Lagunas, E.; Sharma, S.K.; Vuppala, S.; Chatzinotas, S.; Ottersten, B. Margin-Based Active Online Learning Techniques for Cooperative Spectrum Sharing in CR Networks. In Proceedings of the Cognitive Radio-Oriented Wireless Networks: 14th EAI International Conference, CrownCom 2019, Poznan, Poland, June 11–12, 2019, Proceedings 14. Springer, 2019, pp. 140–153.

- Saikia, P.; Pala, S.; Singh, K.; Singh, S.K.; Huang, W.J. Proximal policy optimisation for RIS-assisted full duplex 6G-V2X communications. IEEE Transactions on Intelligent Vehicles 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Lotfolahi, A.; Ferng, H.W. A multi-agent proximal policy optimised joint mechanism in mmwave hetnets with comp toward energy efficiency maximisation. IEEE Transactions on Green Communications and Networking 2023, 8, 265–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, M.; Mughal, D.M.; Kim, S.H.; Chung, M.Y. Deep Reinforcement Learning Assisted Multi-Operator Spectrum Sharing in Cell-Free MIMO Networks. IEEE Communications Letters 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Yang, Y.; Gao, Z.; He, D.; Ng, D.W.K. Dynamic spectrum access for D2D-enabled Internet of Things: A deep reinforcement learning approach. IEEE Internet of Things Journal 2022, 9, 17793–17807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Pan, C.; Zhang, C.; Yang, F.; Song, J. Dynamic spectrum sharing based on deep reinforcement learning in mobile communication systems. Sensors 2023, 23, 2622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khaf, S.; Kaddoum, G.; Evangelista, J.V. Partially cooperative RL for hybrid action CRNs with imperfect CSI. IEEE Open Journal of the Communications Society 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, A.; Du, C.; Ng, S.X.; Liang, W. A cooperative spectrum sensing with multi-agent reinforcement learning approach in cognitive radio networks. IEEE Communications Letters 2021, 25, 2604–2608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; He, X.; Lee, J.; He, D.; Li, Y. Collaborative deep reinforcement learning in 6G integrated satellite-terrestrial networks: paradigm, solutions, and trends. IEEE Communications Magazine 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, P.; Liu, X.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, K.; Huang, Z.; Chen, Y. Distributed Q-learning-enabled multi-dimensional spectrum sharing security scheme for 6G wireless communication. IEEE Wireless Communications 2022, 29, 44–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dašić, D.; Ilić, N.; Vučetić, M.; Perić, M.; Beko, M.; Stanković, M.S. Distributed spectrum management in cognitive radio networks by consensus-based reinforcement learning. Sensors 2021, 21, 2970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Si, J.; Huang, R.; Li, Z.; Hu, H.; Jin, Y.; Cheng, J.; Al-Dhahir, N. When spectrum sharing in cognitive networks meets deep reinforcement learning: Architecture, fundamentals, and challenges. IEEE Network 2023, 38, 187–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, A.; Kumar, K. A reinforcement learning-based evolutionary multi-objective optimisation algorithm for spectrum allocation in cognitive radio networks. Physical Communication 2020, 43, 101196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hlophe, M.C.; Maharaj, B.T. AI meets CRNs: A prospective review on the application of deep architectures in spectrum management. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 113954–113996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Author | Method | Domain | Pros | Cons |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| [39] | DRL at APs for coordination | Cell-Free MIMO, multi-operator | Low signalling, scalable | Dense MNOs not addressed |

| [40] | Autonomous DRL access | D2D IoT | High throughput, no rule dependency | No scalability/user dynamics |

| [41] | DRL for access | CRNs with SU optimization | Fewer collisions, higher reward | No robustness to mobility/interference |

| [42] | Hybrid DRL (discrete-continuous) | Energy-aware CRNs | 99.4% optimal throughput | No scalability or hybrid RL benchmarks |

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| NSGA-II Population Size | 150 |

| NSGA-II Generations | 100 |

| NSGA-II Crossover Probability | 0.9 |

| NSGA-II Mutation Probability | 0.1 |

| PPO Learning Rate | 0.0003 |

| PPO Discount Factor () | 0.99 |

| PPO Clip Range () | 0.2 |

| PPO Epochs | 10 |

| PPO Batch Size | 64 |

| Strategy | Avg Reward | Fairness | Energy Efficiency (bits/J) | Interference (%) | Spectrum Utilisation (%) | PU Collisions (%) | Hypervolume (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Random | 1.47 | 1.00 | 65.96 | 8.00 | 13.00 | 2.67 | – |

| Greedy | 3.70 | 1.00 | 132.58 | 8.00 | 24.00 | 2.67 | – |

| PPO Alone | 4024.45 | 1.00 | 118.64 | 26.78 | 56.82 | 26.78 | – |

| NSGA-II + PPO | 3433.73 | 1.00 | 120.23 | 22.88 | 48.83 | 22.88 | 65.2 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).