Introduction

Refraction artifacts in ultrasound imaging can produce the appearance of ghost side-by-side structures and, in some cases, spurious color Doppler jets. Similarly, the refraction of light causes a fish to appear farther away than its actual position. These phenomena result from a bent path taken by the sound waves or light rays. This bent path can also be observed when a lifeguard approaches a drowning swimmer: running a longer distance on sand before entering the water at an angle to minimize total rescue time. In all cases—ultrasound waves, light rays, and the lifeguard—the path bends as it crosses media with different propagation speeds, a behavior governed by Snell’s law and Fermat’s principle of least time. This fastest-path problem can be solved analytically by setting the derivative of the total travel time with respect to the point of path bending to zero, yielding a local minimum [Serway et al., 2000, p.1128]. Notably, in the lifeguard-swimmer scenario, minimizing total time does not mean minimizing the swimming distance. The fastest route requires more running and less swimming, but not the minimum swim distance along the perpendicular. In this paper, we present an intuitive geometric proof that shows this path is indeed the shortest combination in terms of distances from the interface to the “wave fronts”, and thus the fastest overall.

Main

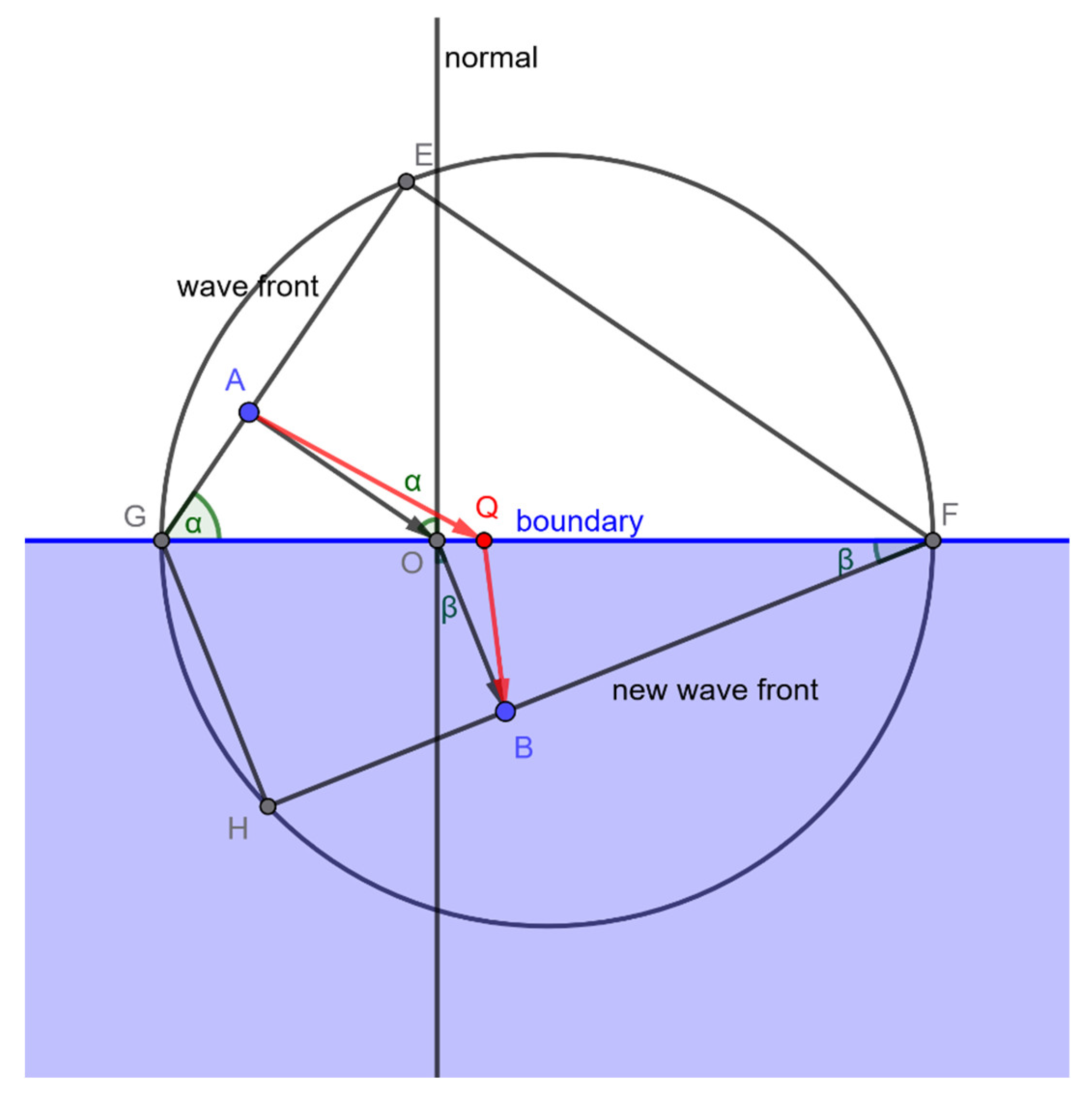

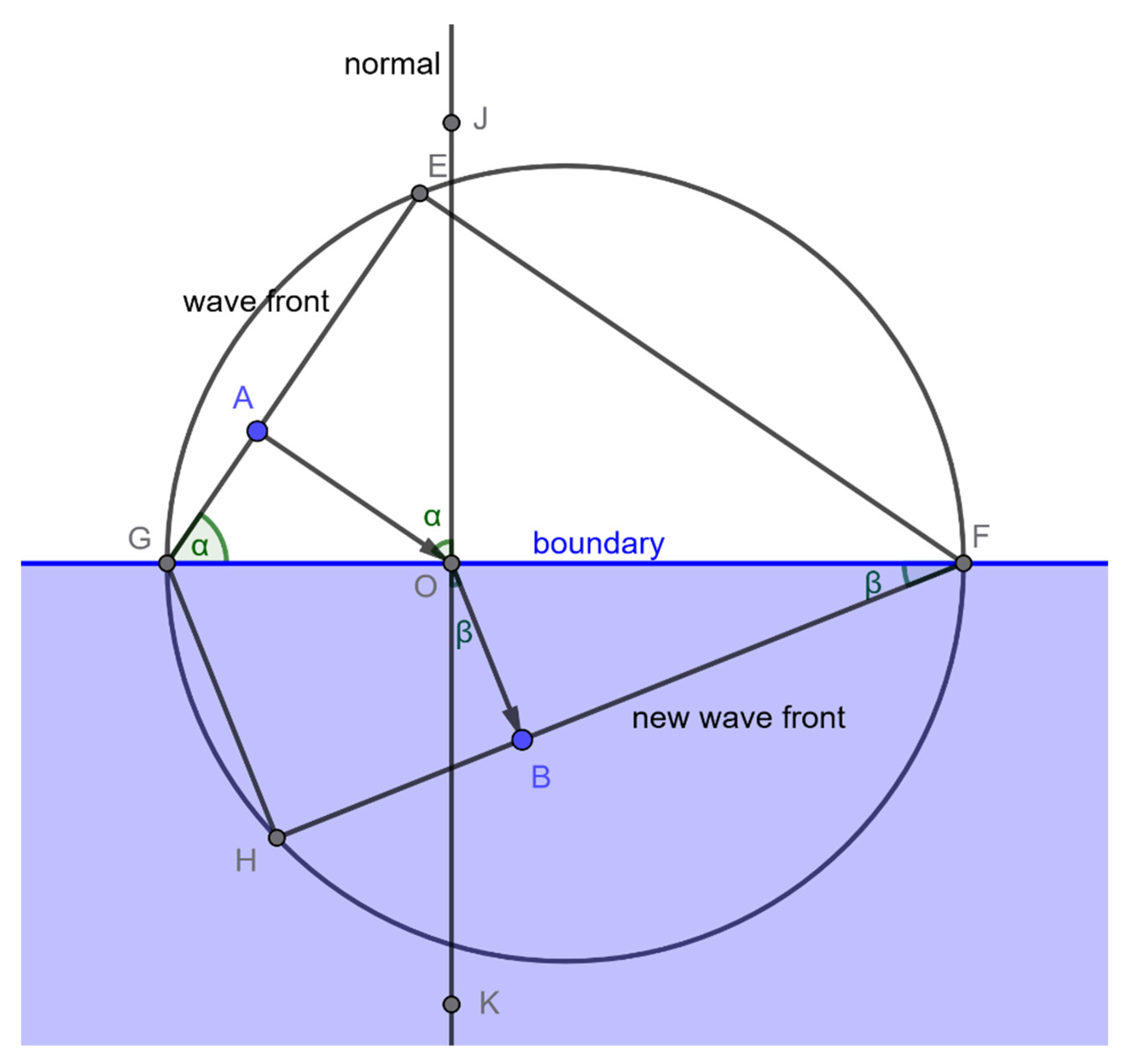

Light Follows the Path AOB

Suppose light travels from point A to point B according to Snell’s law, following the path AOB. We can construct a circle as shown below, with diameter GF, and two right triangles GEF and GHF. Using this construction, we will demonstrate—purely through geometry—that AOB represents the fastest path. In the diagram, the angles of incidence (

) and refraction (

) are determined by Snell’s law:

where

are the propagation speeds in the respective media [Serway et al., 2000, p.1117].

Firstly, we will establish EF and GH are equivalent in terms of the travel time.

The Travel Time Along Paths EF and GH Are Equal

Suppose the propagation speeds in medium 1 and medium 2 are respectively.

In

Figure 1, the following angles are observed:

According to Snell’s Law,

And by trigonometry, we know

Therefore, after substituting the sine terms and cancelling

, we obtain

This implies that the travel time from point E to point F is equal to the travel time from point H to point G.

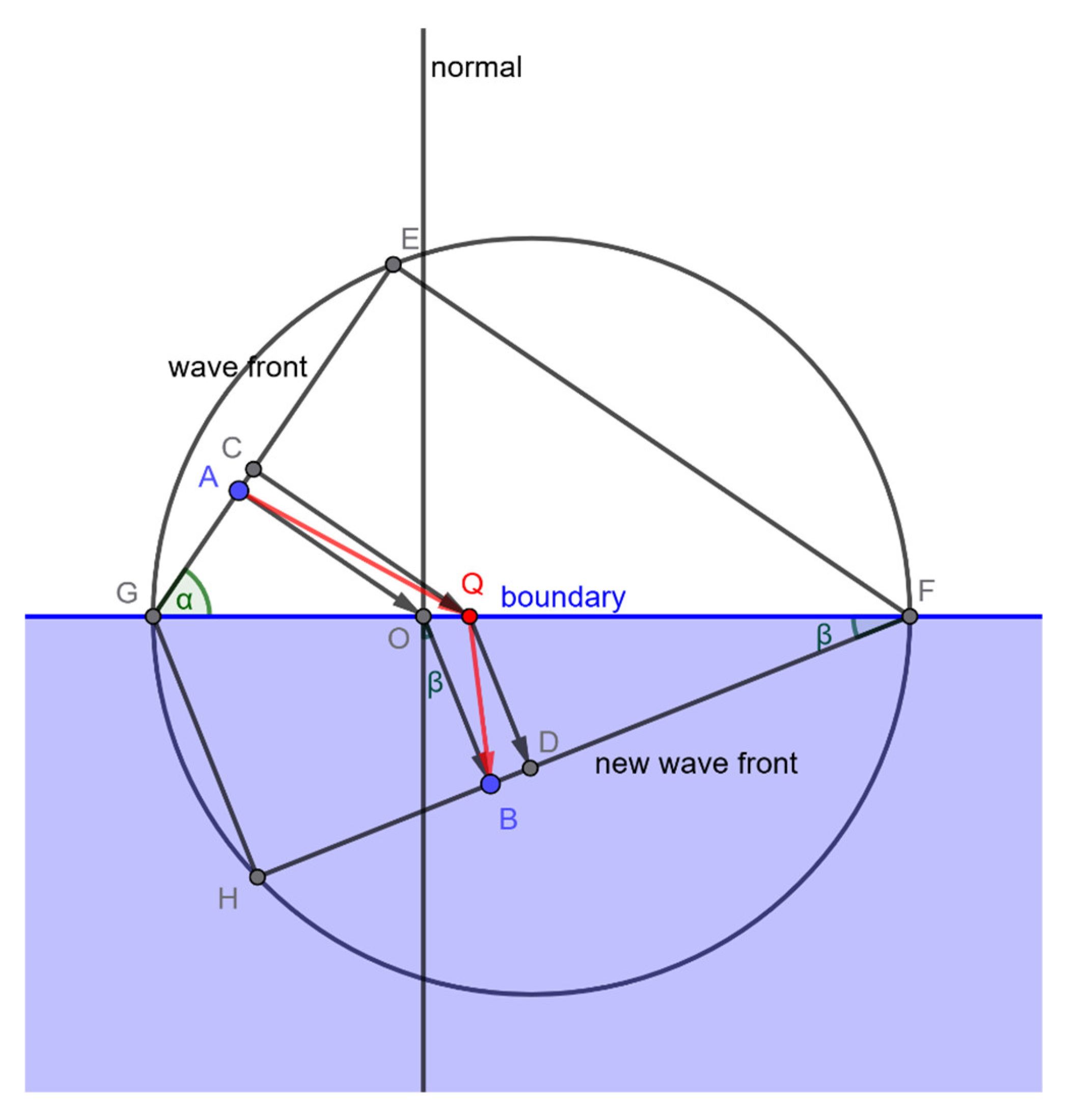

Suppose a Light Ray Takes an Alternative Path AQB

Let Q be any point on the boundary other than O, and suppose a light ray travels along the path AQB. In this scenario, AQ is longer than AO, while BQ is shorter than BO. As a result, it is not immediately evident whether the total path AQB is longer or shorter than AOB. The objective is to demonstrate that the travel time along AQB is greater than that of AOB—in other words, that AOB represents the fastest path.

Figure 2.

Let Q be any point on the boundary other than O. In the diagram, AQ is longer than AO, while BQ is shorter than BO. Consequently, it is not immediately clear whether the total path AQB is longer or shorter than AOB. The aim is to show that the travel time along AQB is greater than that along AOB—that is, AOB represents the fastest path.

Figure 2.

Let Q be any point on the boundary other than O. In the diagram, AQ is longer than AO, while BQ is shorter than BO. Consequently, it is not immediately clear whether the total path AQB is longer or shorter than AOB. The aim is to show that the travel time along AQB is greater than that along AOB—that is, AOB represents the fastest path.

Construct the Path CQD

From point Q, we construct the path CQD such that CQ is perpendicular to GE and QD is perpendicular to FH.

Figure 3.

Find point C such that and point D such that . Of note, and . It is obvious that AQ > CQ and QB > QD since the shortest distance from a point to a line is along the perpendicular.

Figure 3.

Find point C such that and point D such that . Of note, and . It is obvious that AQ > CQ and QB > QD since the shortest distance from a point to a line is along the perpendicular.

Fermat’s principle implies the path obeying Snell’s law is the fattest path. Any other paths will result in longer time. Below is the proof by geometry.

Question to prove: From point A to point B, the path AOB follows Snell’s Law. Q is any other point on the boundary. Prove that the path AQB takes longer to travel than AOB.

1) Path AQB is longer than Path CQD.

From point Q, we can find point C on GE such that CQ is perpendicular to GE. Similarly, we can find point D on HF such that QD is perpendicular to HF. Because the shortest distance from a point to a line is along the perpendicular, therefore AQ > CQ and QB > QD. It follows that AQ + QB > CQ + QD. Thus, AQB is a longer path than CQD.

2) Path CQD and AOB have the same travel time.

By applying the properties of similar triangles, we obtain the following.

As shown earlier, by the definition of Snell’s law,

. Therefore,

Thus,

Similarly, we can derive

:

As we know,

Thus,

From (1) and (2), we derive

That is, AOB and CQD have equal travel time.

3) Path AQB requires more time to travel than path AOB.

As established in (1), the path AQB is longer than the path CQD. Since AOB and CQD have equal travel time, it follows that AQB requires more time to travel than AOB.

Q.E.D.

Discussion

The intuition. The above proof can be further simplified by considering the behavior of light. While AO and OB represent the directions of propagation, GE and FH are wavefronts perpendicular to those paths. Since all points on a wavefront advance simultaneously, when point E reaches F, point C reaches D, A reaches B, and G reaches H. This implies that paths AOB and CQD are equivalent in terms of travel time. In contrast, AQB is visibly longer than CQD, and therefore must also be “longer” than AOB.

Lifeguard and swimmer. Given the lifeguard’s running speed on land and swimming speed in water, and any fixed positions A and B for the lifeguard and the drowning swimmer, a corresponding circle can be constructed. In every case, it can be shown in the same fashion that the path AOB is indeed the fastest route.

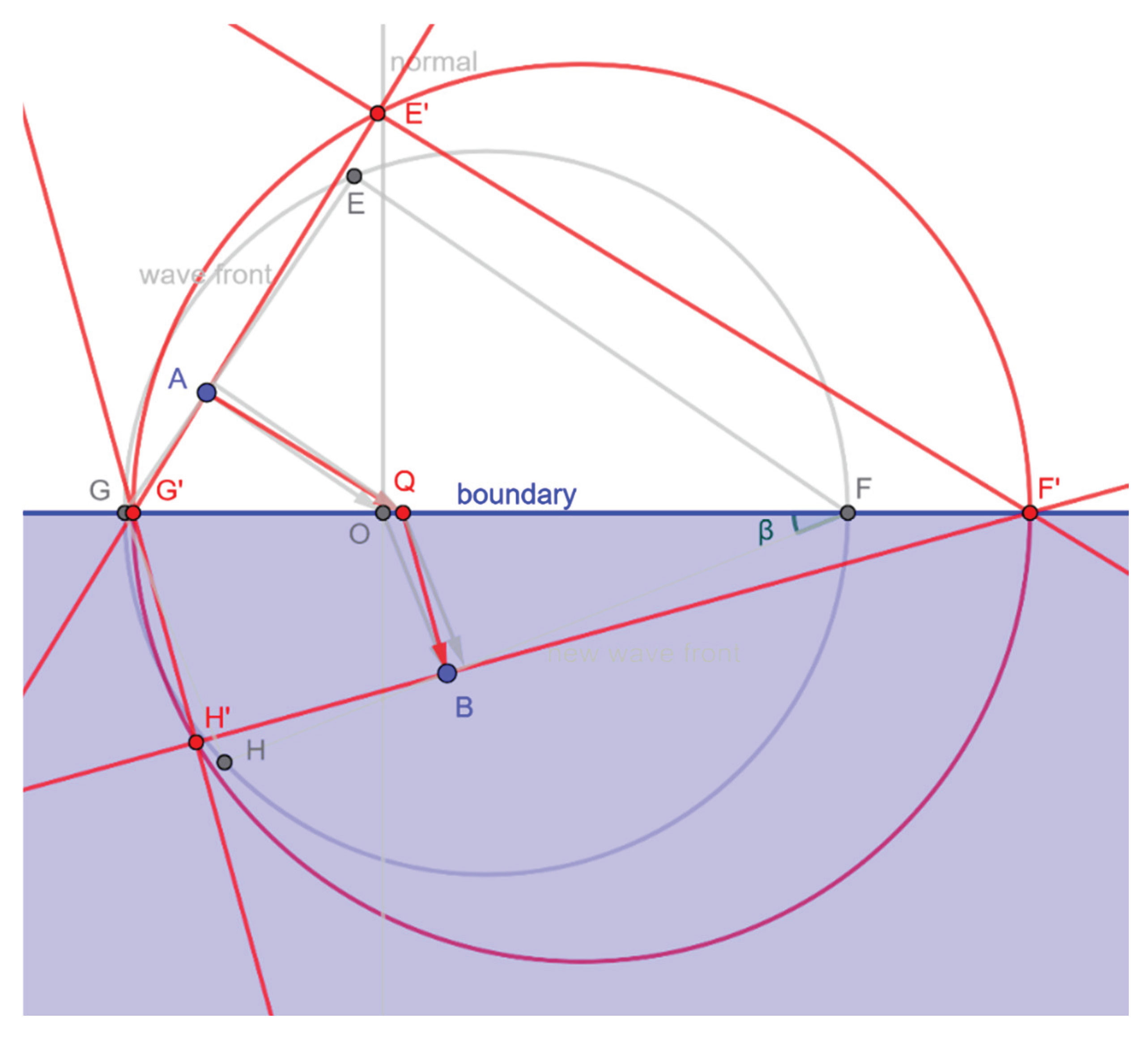

Point of refraction by geometry. Given points A and B, we initially do not know the exact point at which the path should refract. To begin, we randomly select a point Q on the boundary between A and B. For some different propagation speed ratio , this path AQB will be the fastest one. As established during the proving process, we know . If , like this case, then Q must lie to the right of O, suggesting that a slower swimmer will aim to minimize swimming distance. This insight guides us to test another point Q located further to the left. By iteratively adjusting the position of point Q and recalculating the ratio , we will eventually converge on point O, which corresponds to the path of least time.

Figure 4.

From an arbitrary point Q on the boundary, a new circle can be constructed with G′F′ as the diameter and E′F′ and G′H′ as the new opposite sides. The ratio E′F′/G′H′ is clearly greater than EF/GH, indicating that the path AQB involves more running and less swimming. This implies that point Q lies to the right of point O.

Figure 4.

From an arbitrary point Q on the boundary, a new circle can be constructed with G′F′ as the diameter and E′F′ and G′H′ as the new opposite sides. The ratio E′F′/G′H′ is clearly greater than EF/GH, indicating that the path AQB involves more running and less swimming. This implies that point Q lies to the right of point O.

Ants and food. Although ants do not understand physics or calculus, studies have shown that they can approximate Snell’s law when crossing different surfaces and follow the faster path to a food source [Oettler et al., 2013]. Such geometric intuition is likely the result of millions of years of evolution

Refraction artifacts in ultrasound imaging. Refraction artifacts can produce misleading side-by-side structures or color doppler jets in ultrasound imaging [Hadzik et al., 2017; Naganuma et al. 2021, Ochi et al., 2020]. A clear understanding of the underlying physics and geometry of these artifacts can aid in making an accurate diagnosis.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Generative AI

During the preparation of this work, we used ChatGPT to edit English writing and grammar. After using ChatGPT, we reviewed and edited the content as needed and take full responsibility for the content of the publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest

References

- Hadzik R, Bombiński P, Brzewski M. Double aorta artifact in sonography - a diagnostic challenge. J Ultrason. 2017 Mar;17(68):36-40. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naganuma H, Ishida H, Uno A, Nagai H, Ogawa M, Kamiyama N. Refraction artifact on abdominal sonogram. J Med Ultrason (2001). 2021 Jul;48(3):273-283. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ochi Y, Yamasaki N, Baba Y, Kawaguchi J, Nakashima Y, Ueta M, Hirota T, Kubo T, Kitaoka H. A single atrial septal defect masquerading as multiple defects due to a refraction artifact - A cautionary note. J Cardiol Cases. 2020 Apr 27;22(2):55-58. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oettler J, Schmid VS, Zankl N, Rey O, Dress A, Heinze J. Fermat’s principle of least time predicts refraction of ant trails at substrate borders. PLoS One. 2013;8(3):e59739. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Serway R, Beichner R, Jewett J. Physics for Scientists and Engineers with Modern Physics. 5th edition., Sounders College Publishing; 2000.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).