1. Introduction

Water hyacinth (Eichhornia crassipes [Mart.] Solms), native to South America, is now one of the most pervasive invasive species affecting tropical and subtropical aquatic ecosystems across the globe excluding Antarctica [

1]. It thrives in warm, nutrient-rich waters and can double its biomass within weeks under sympathetic conditions [

2,

3]. Its proliferation is driven by eutrophication, high nutrient concentrations (especially total nitrogen and phosphorus), elevated pH, increased temperature, low lake water level, and minimal disturbance of the water body [

4,

5,

6,

7,

8].

Satellite-based remote sensing has become a vital tool for capturing spatial and temporal environmental changes, often caused by natural processes or anthropogenic activities [

9]. Especially in data-scarce or inaccessible regions, remote sensing offers a practical means of monitoring aquatic systems. Since the launch of the Landsat program in the 1970s, remote sensing technologies have evolved significantly, enhancing monitoring frequency, spatial resolution, and thematic scope [

10]. The introduction of multispectral and hyperspectral sensors in the 1980s–1990s expanded their utility in environmental applications, while later advances such as Synthetic Aperture Radar (SAR) enabled effective monitoring under cloud cover and at night. The 2010s saw further enhancements with the use of Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs) and the integration of machine learning algorithms, improving spatial detail and classification accuracy [

11].

Sensor resolution remains critical: MODIS, with coarse resolution (250 m–1 km), has been applied to large-scale assessments [

12,

13], whereas high-resolution sensors such as Landsat 8 OLI and Sentinel-2 MSI enable localized, long-term studies [

14,

15].Landsat sensors including ETM+, OLI, and TIRS have been widely used to monitor water hyacinth distribution and water quality indicators such as chlorophyll-a, turbidity, and suspended solids [

16,

17]. Sentinel-2A/B, offering 10–20 m resolution with a 5-day revisit cycle, is increasingly applied in mapping aquatic vegetation and optically active water quality parameters like algal blooms [

18,

19,

20].

Hyperspectral sensors, especially in the 700–900 nm range, have demonstrated superior performance in differentiating water hyacinth from native vegetation, with methods like the Spectral Angle Mapper (SAM) improving classification accuracy by over 20% [

21]. Similarly, combining Sentinel-2 MSI with UAV imagery and machine learning classifiers such as Random Forest has achieved over 92% accuracy in detecting small-scale infestations [

22].

Spectral indices such as the Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI), the Normalized Difference Water Index (NDWI), and the Enhanced Vegetation Index (EVI) have also been employed to estimate water hyacinth biomass and seasonal changes [

13,

23]. NDVI values >0.6 typically indicate dense mats [

24,

25]. NDWI enhances water-body delineation and, when combined with NDVI, improves vegetation classification [

26,

27].

Traditionally, monitoring inland waters has been challenging due to spatial and temporal limitations. The highly dynamic nature of water hyacinth across time and space makes it difficult to accurately measure its areal coverage and expansion rate. Obtaining reliable spatial and temporal data through conventional methods also requires significant labor and financial resources. Furthermore, assessing water quality using traditional approaches relies on laboratory-based analyses, which are limited in spatial coverage and typically focus on a few selected sampling points [

28].

Remote sensing technologies now enable efficient, large-scale, and near real-time monitoring of aquatic systems [

29]. Despite advancements in remote sensing, a comprehensive synthesis of global applications for monitoring water hyacinth and water quality remains lacking. This gap is increasingly critical given the rapid spread of water hyacinth and worsening pollution in freshwater ecosystems worldwide.

This systematic review is essential for understanding the global impact of water hyacinth and current monitoring practices that incorporate satellite remote sensing. While some regions have established effective monitoring systems, many affected areas particularly in resource-constrained settings still lack consistent and reliable approaches. Existing studies are often fragmented and region-specific, utilizing a wide range of sensors, methodologies, and indices, which limits comparability and knowledge transfer.

Although some regions have implemented effective monitoring systems, many, particularly in resource-constrained settings still lack consistent, scalable, and cost-effective strategies for water hyacinth monitoring [

6,

30,

31]. There remains limited and consolidated knowledge on the most effective monitoring approaches for managing this invasive species. Existing studies are fragmented and highly context-specific, utilizing a range of sensors, methodologies, and indices. This diversity hinders standardization, comparability, and the broader application of monitoring strategies[

27].

Moreover, there is a notable absence of global syntheses that integrate recent advances in satellite remote sensing with machine learning and deep learning techniques, especially across diverse freshwater environments. Few studies have rigorously assessed the adaptability and performance of these algorithms in combination with Earth observation data for detecting water hyacinth and assessing associated water quality parameters [

32,

33]

Therefore, an organized, up-to-date review of current monitoring practices emphasizing the use of advanced satellite platforms and analytical tools are important. Such a synthesis can offer valuable insights for researchers, practitioners, and policymakers, supporting the development of more effective, scalable, and technology-driven solutions for managing aquatic invasive species and protecting water quality.

This systematic review aims to: 1) Categorize trends in remote sensing applications for monitoring water hyacinth and optically active water quality parameters 2) Assess the integration of machine learning algorithms with remote sensing datasets and finally, 3) identify current gaps, challenges, and future directions in the remote sensing-based monitoring of inland water bodies.

2. Materials and Methods

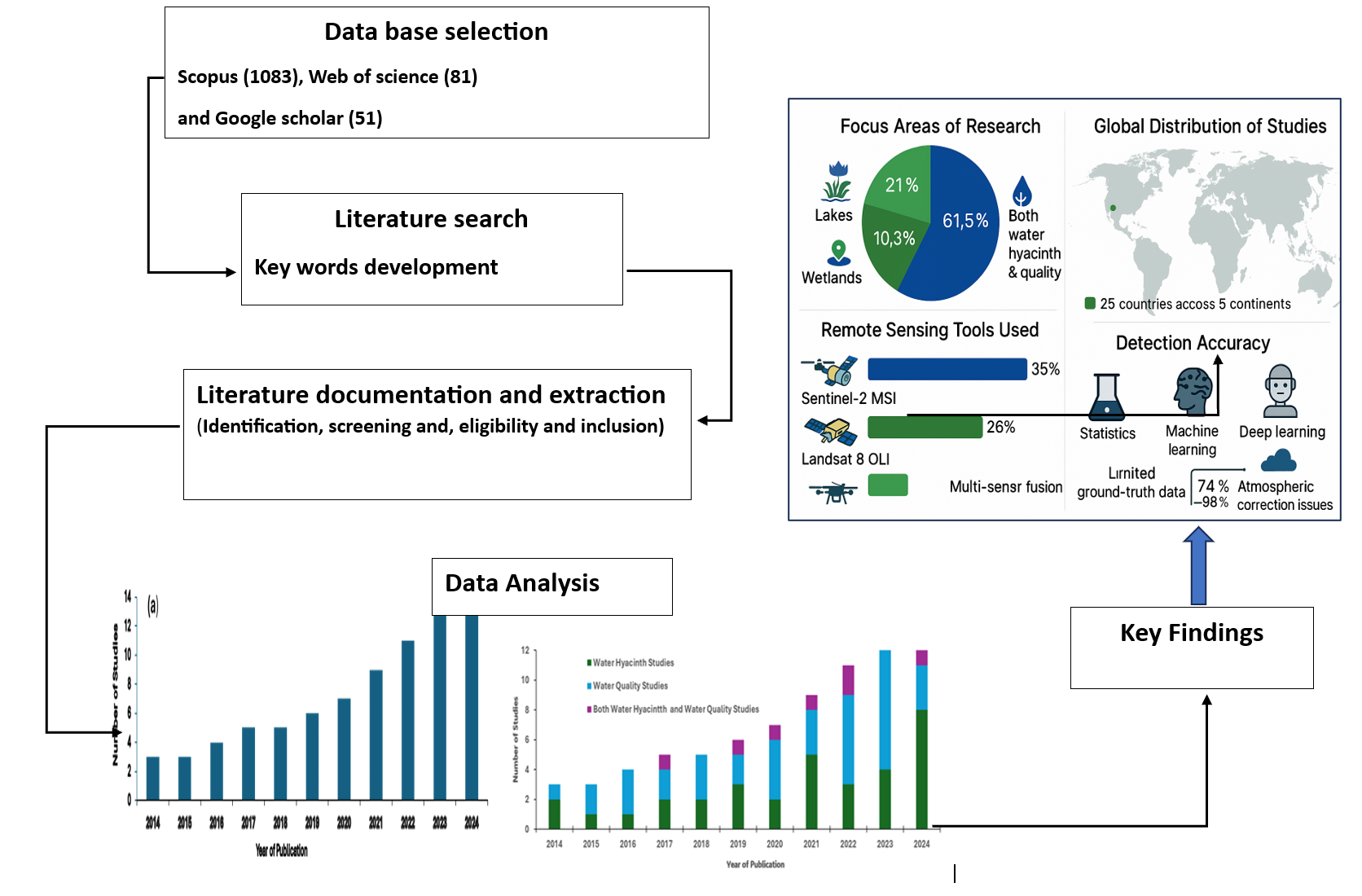

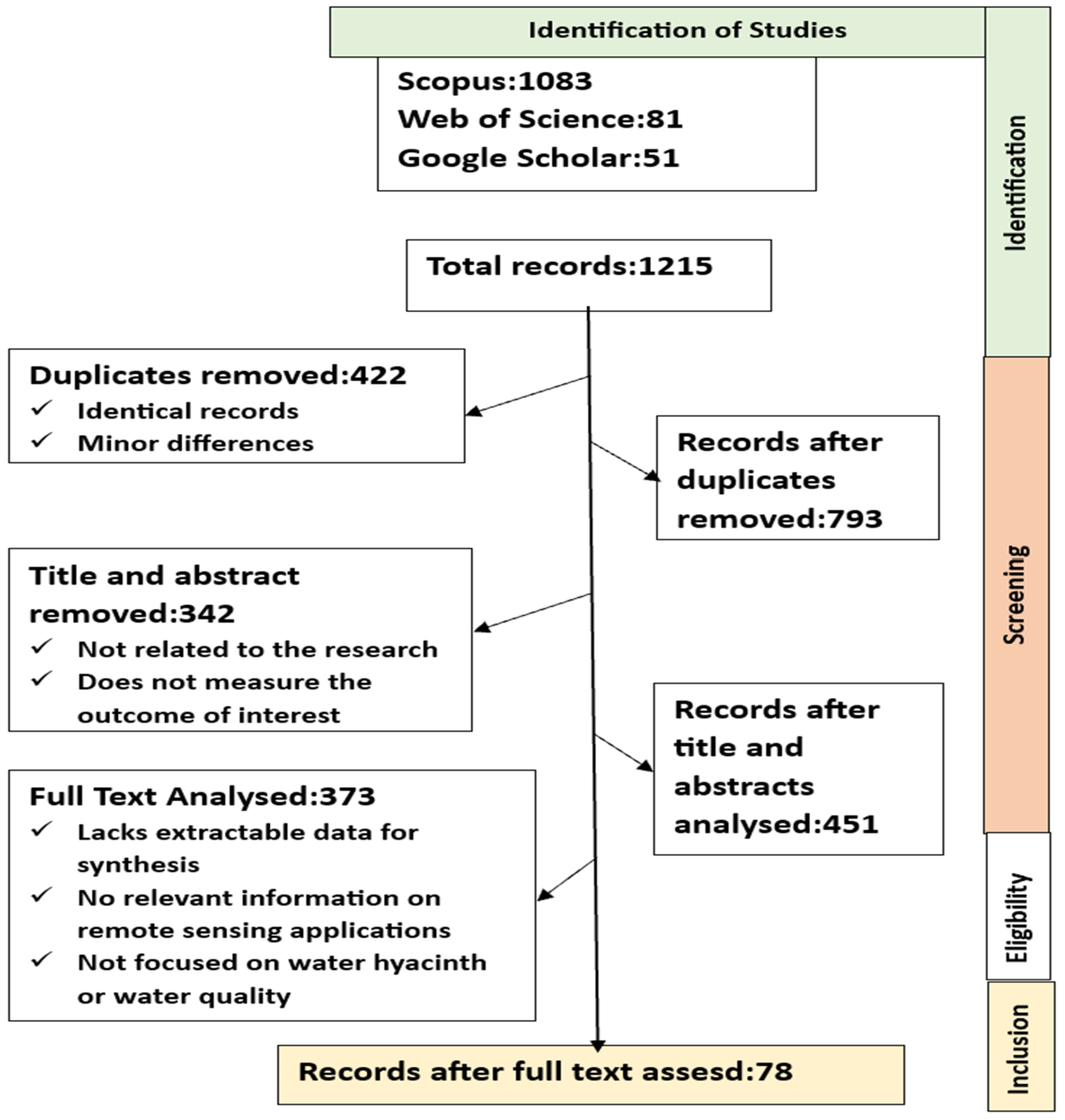

This study employed a systematic literature review to investigate global applications of remote sensing technologies in monitoring water hyacinth and key water quality parameters. The methodological process was structured into three main phases literature identification, screening and selection, and comprehensive data extraction following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines [

34]. These phases supported subsequent bibliometric, thematic, and spatial analyses to synthesize trends and insights from the selected literature.

The literature identification phase involved a structured and comprehensive search of peer-reviewed journal articles published between 2014 and 2024. The focus was on studies that employed remote sensing technologies particularly satellite imagery and unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) to detect and quantify water hyacinth or assess optically active water quality parameters such as chlorophyll-a, turbidity, and total suspended solids (TSS). The search strategy was carefully designed using Boolean operators (“AND” and “OR”) to ensure both precision and breadth, allowing for the retrieval of studies that integrated relevant remote sensing methods with ecological and water quality applications.

Searches were conducted across three major academic databases: Scopus, Web of Science, and Google Scholar. The keyword development process is centered on four major thematic categories. The first involved remote sensing tools and terminology, including terms like “remote sensing,” “satellite imagery,” “UAV,” and “drone.” The second focused on the target invasive species, using keywords such as “water hyacinth” and “Eichhornia crassipes.” The third category addressed water quality parameters, incorporating terms like “chlorophyll-a,” “turbidity,” and “total suspended solids.” The final category included broader contextual and functional descriptors such as “monitoring,” “detection,” “mapping,” “lakes,” “rivers,” “wetlands,” and “global water bodies.”

Table 1.

Summary of Key words used applied for Literature Search.

Table 1.

Summary of Key words used applied for Literature Search.

| Category |

Keywords Used |

| Remote Sensing Technologies |

“Remote sensing”, “satellite imagery”, “UAV”, “drone” |

| Target Species |

“Water hyacinth”, “Eichhornia crassipes” |

| Water Quality Parameters |

“Chlorophyll-a”, “turbidity”, “total suspended solids” |

| Monitoring and Context |

“monitoring”, “detection”, “mapping”, “global water bodies”, “lakes”, “rivers”, “wetlands” |

A representative search string applied during this phase was: TITLE-ABS-KEY ((“remote sensing” OR “satellite imagery” OR “UAV” OR “drone”) AND (“water hyacinth” OR “Eichhornia crassipes”) OR (“water quality” OR “chlorophyll-a” OR “turbidity” OR “total suspended solids”) AND (“monitoring” OR “detection” OR “mapping”) AND (“global water bodies” OR “lakes” OR “rivers” OR “wetlands”)). Through this process, a total of 1,215 unique articles were retrieved from the three databases.

Following literature identification, the next step involved a rigorous screening and selection process. Initially, duplicate entries typically arising from overlapping indexing across databases were identified and removed. This step resulted in the elimination of 422 redundant records. The remaining studies were then subjected to a two-stage relevance screening process.

In the first stage, titles and abstracts were reviewed to assess whether the studies met basic inclusion criteria. Eligible articles were required to be published in English, fall within the 2014–2024 timeframe, and demonstrate the application of remote sensing technologies within aquatic ecosystems. At the conclusion of this stage, 451 articles were retained for full-text evaluation.

The second stage consisted of a detailed full-text review to determine methodological rigor and thematic relevance. Articles were included if they employed remote sensing to monitor water hyacinth, water quality parameters, or both. Additional inclusion criteria required the explicit description of the study’s spatial context and scale, the type of sensor or platform used, and a clearly articulated methodological framework. Studies that lacked transparency in methodology, did not focus on aquatic ecosystems, or failed to incorporate remote sensing as a core analytical component were excluded. After this thorough evaluation, 78 studies were deemed suitable for in-depth analysis (

Figure 1).

Data extraction focused on capturing key bibliometric and methodological attributes from the selected studies. A structured template was developed in Microsoft Excel to standardize metadata, including publication year, author affiliations, journal title, geographic study location, sensor type, and analytical approach. The dataset was carefully cleaned to address formatting inconsistencies and ensure uniform categorization across entries.

Subsequently, a bibliometric analysis was conducted to explore publication trends, sensor usage patterns, disciplinary distribution, and geographic representation. Special attention was given to the types and details of remote sensing platforms employed as well as the types of journals that published these studies. Quantitative trends were visualized using line and bar charts to highlight dominant research trajectories and identify temporal or regional gaps in literature.

In addition to bibliometric characterization, a thematic analysis was conducted to classify the studies based on their research focus and methodological orientation. A deductive colour coding approach was adopted on Microsoft excel, whereby each article was reviewed and categorized into thematic areas based on its objectives and analytical methods.

The thematic classification distinguished between studies focused solely on the detection and mapping of water hyacinth, retrieval of water quality parameters, and integrated studies addressing both topics. Further thematic dimensions included the use of different sensor platforms (e.g., multispectral satellite data, UAV-based imagery), analytical techniques (e.g., empirical method semi empirical method and analytical method), and the specific water body type studied.

The coding process was performed manually through iterative reading of the studies to ensure consistency and validity. Cross-validation of themes was conducted by comparing objectives and conclusions to confirm the accuracy of classifications. This thematic synthesis enabled the identification of methodological innovations, technology integration patterns, and existing research gaps.

To assess the geographic distribution of the reviewed studies, spatial data were extracted from each article and processed using QGIS version 3.34.12. Geocoded study locations were mapped to visualize the global distribution of research activities involving the application of remote sensing technologies for inland water monitoring. This spatial analysis revealed distinct regional clusters of research, particularly in countries with well-established remote sensing infrastructure and technical capacity. These disparities in spatial research coverage underscore uneven access to remote sensing resources and technical expertise. The geographic visualization thus provided critical insights into global imbalances in technological application, informing recommendations for future research investment and capacity-building efforts in data-scarce regions.

Reference management was carried out using Mendeley Desktop, ensuring systematic organization and accurate citation, throughout the review process.

3. Results

3.1. Description of Articles and Publication Trends

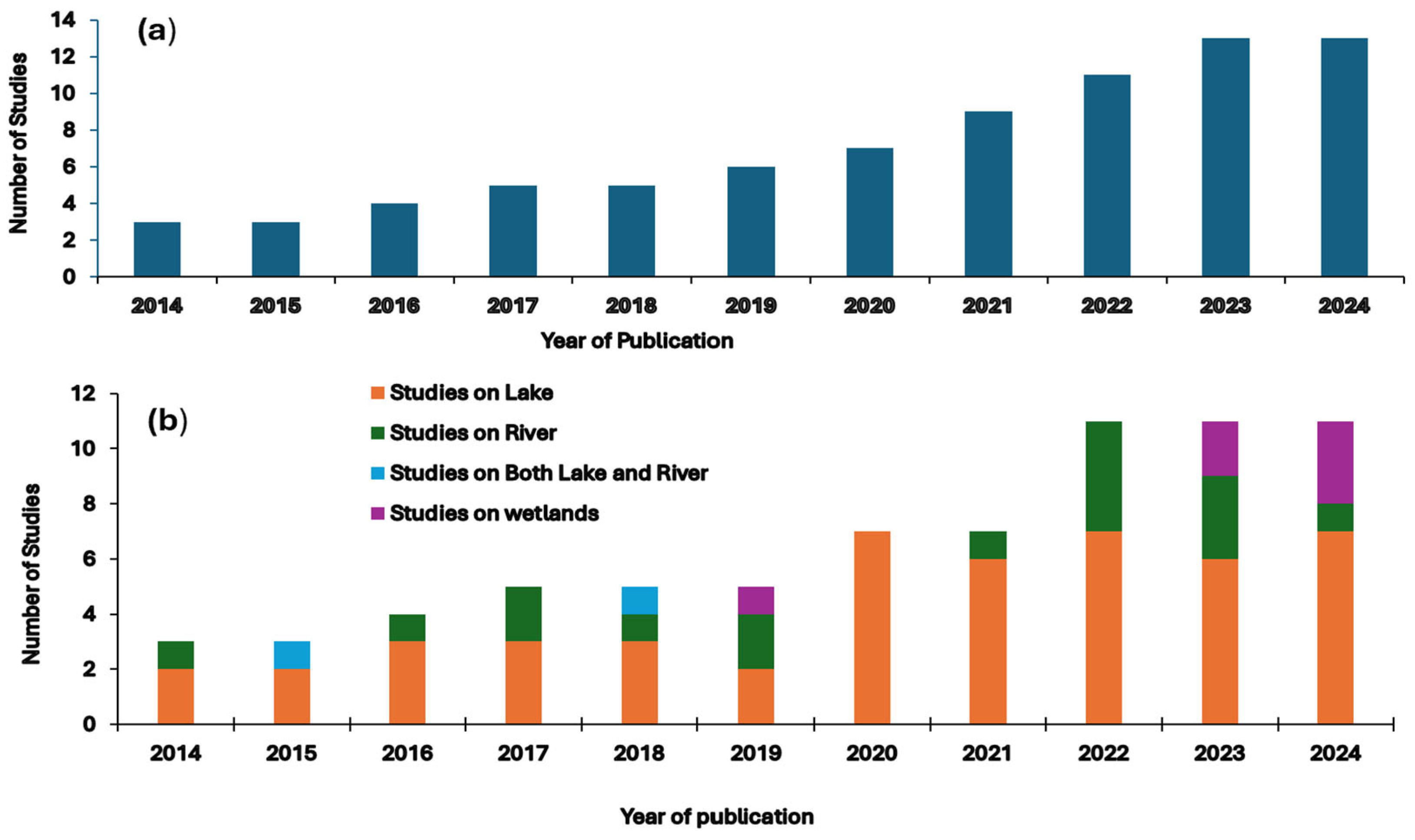

Analysis of publication trends indicates that between 2014 and 2017, the annual number of published articles remained relatively low and stable, ranging from 3 to 5 publications per year. This period coincided with the early phase of the Sentinel-2 mission, which had not yet begun capturing imagery, leaving Landsat 8 OLI as the primary freely accessible multispectral high-resolution sensor in use [

35] . However, beginning in 2019, a marked increase in annual publication output was observed. As shown in

Figure 2a, the number of studies focusing on water hyacinth and water quality monitoring exhibited a steady upward trend from 2018 to 2024.

In terms of the types of water bodies investigated between 2014 and 2024, lakes were the most frequently studied, accounting for 48 studies (61.5%) (

Figure 2b). Rivers followed with 16 studies (21%), while wetlands were the focus of 8 studies (10.3%), primarily published in 2019, 2023, and 2024. A smaller portion of research (6 studies, 7.7%) analyzed both lakes and rivers, reported in 2015 and 2018 publications.

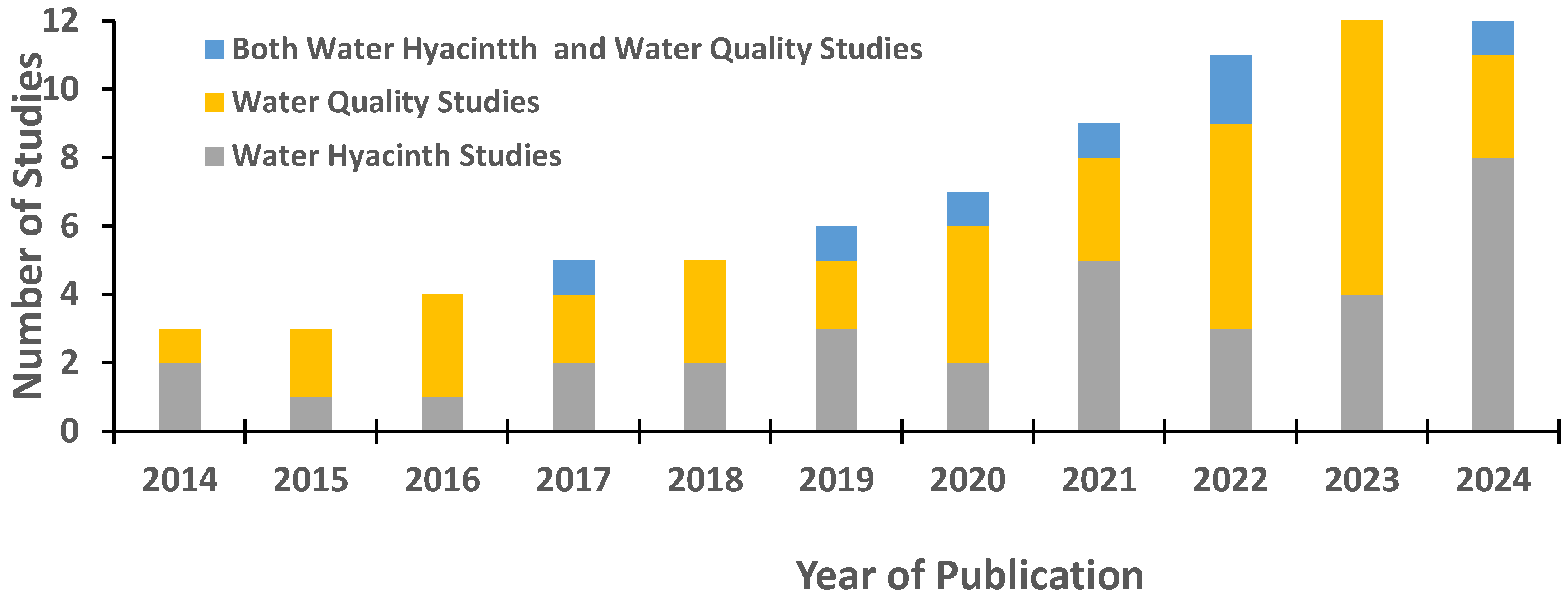

The reviewed studies were further categorized based on their primary focus: water hyacinth mapping, water quality assessment, or both (

Figure 3). Approximately 33 studies (42%) focused on water hyacinth, including biomass estimation and spatiotemporal variability analysis. Meanwhile, 38 studies (49%) addressed water quality parameters. The remaining 7 studies (9%) investigated both water hyacinth and water quality within integrated case studies (

Figure 3).

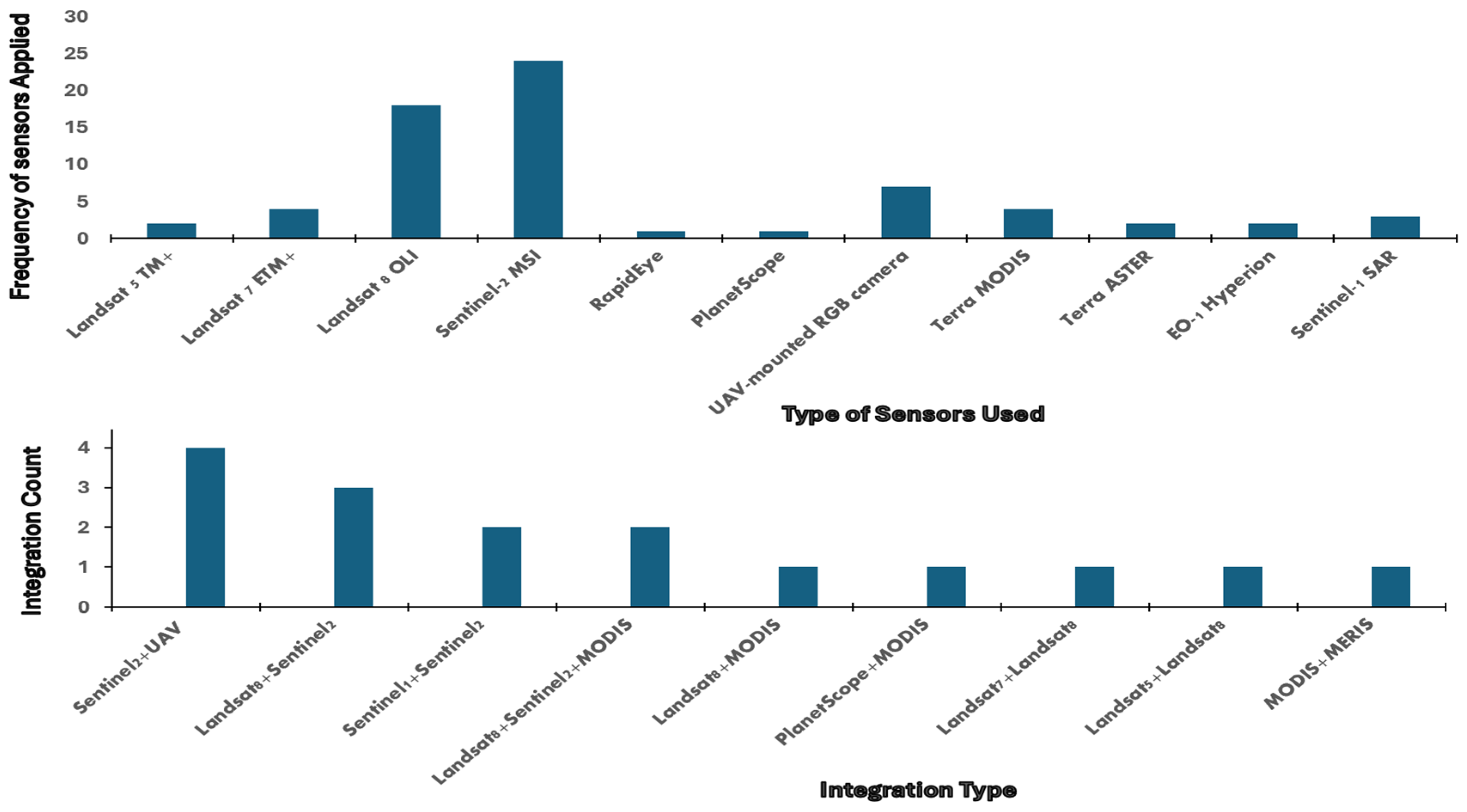

Figure 4a illustrates the application trends of satellite sensors used for monitoring water hyacinth and water quality. Among the sensors analyzed, Sentinel-2 MSI emerged as the most frequently utilized, appearing in 24 studies focused on lakes, rivers, and wetlands. Its usage has notably increased since 2017, both as a standalone dataset and in combination with other sensors.

Irrevocably, the use of unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) equipped with RGB sensor cameras for inland water monitoring has increased in recent years, as evidenced by their application in seven studies reviewed. UAVs were predominantly employed for lake water quality monitoring, owing to their high spatial resolution, operational flexibility, and ability to capture detailed local-scale data.

In parallel, MODIS Terra and Landsat 7 ETM+ were each utilized in four studies within the review period, reflecting their continued relevance in inland water monitoring applications. Additionally, hyperspectral Hyperion EO-1, Terra ASTER, Sentinel-1 SAR, and Landsat 5 TM were each reported in two studies, highlighting their more limited but targeted application in monitoring water hyacinth and water quality in various global water bodies

Figure 4a.

Figure 4b presents the distribution of integrated sensor applications across the reviewed studies. Within the reviewed literature, a total of 16 combined sensor applications were identified. Among these, the integration of Sentinel-2MSI and UAVs equipped with RGB cameras emerged as the most frequently employed multi-sensor approach, reported in four studies (25%).

Additionally, three studies (18.75%) utilized integrated datasets from Landsat 8 OLI and Sentinel-2 MSI to monitor water hyacinth and assess water quality parameters. Both sensors were also widely used individually and in combination for the estimation of chlorophyll-a (Chl-a) concentrations in global lakes. Furthermore, combined applications within the Sentinel satellite series and triple-sensor integrations involving Landsat 8 OLI, Sentinel-2 MSI, and MODIS Terra were each reported in two studies (12.5%), primarily aimed at enhancing temporal resolution and detection accuracy (

Figure 4b).

In contrast, a limited number of studies employed other sensor combinations, such as the integration of Landsat 8 OLI with MODIS, PlanetScope with MODIS, various combinations of the Landsat series, and the fusion of MODIS with MERIS. These approaches showed relatively low adoption in the reviewed literature, indicating more specialized or context-specific applications in inland water monitoring.

3.2. Trends in Journal Publications

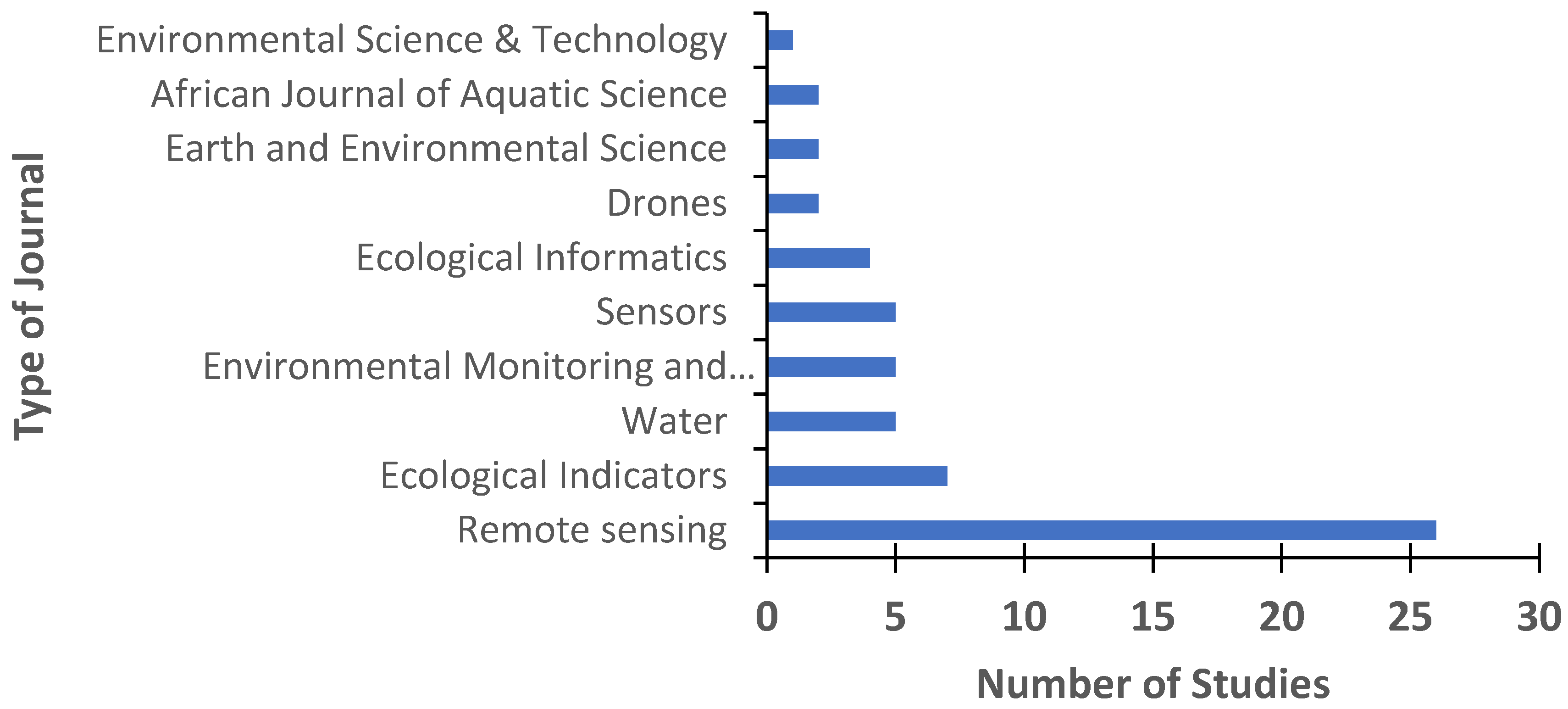

Figure 5 presents the top ten journals that published the articles included in this review. The diversity of journal categories reflects the interdisciplinary nature and broad thematic coverage of the studies, spanning remote sensing, water quality, hydrology, and ecological monitoring. This variety highlights a wide array of suitable publication outlets for research in these domains.

Journals such as Environmental Science & Technology, Ecological Indicators, and the Journal of Hydrology served as prominent platforms for high-impact publications. Meanwhile, specialized journals like Remote Sensing and Water were frequently utilized for publishing technical and application-specific research.

Among the identified journals, Remote Sensing emerged as the most prominent outlet, accounting for 26 articles (33.3%) of the reviewed studies. This was followed by Ecological Indicators with 7 articles (9%). Water, Sensors, and Environmental Monitoring and Assessment each published 5 articles (6.4%), while Ecological Informatics contributed 4 articles (5%).

In contrast, Journal of Earth and Environmental Science, Drones, and the African Journal of Aquatic Science each accounted for 2 publications (2.6%). The Environmental Science and Technology appeared least frequently among the top ten, contributing only 1 article (1.3%)

Figure 5.

Table 2 summarizes the journals included in the review, presenting their publishers, Impact Factor (IF), 5-Year IF, quartile rankings, SCImago Journal Rank (SJR), and CiteScore.

3.3. Global Distribution of Studies

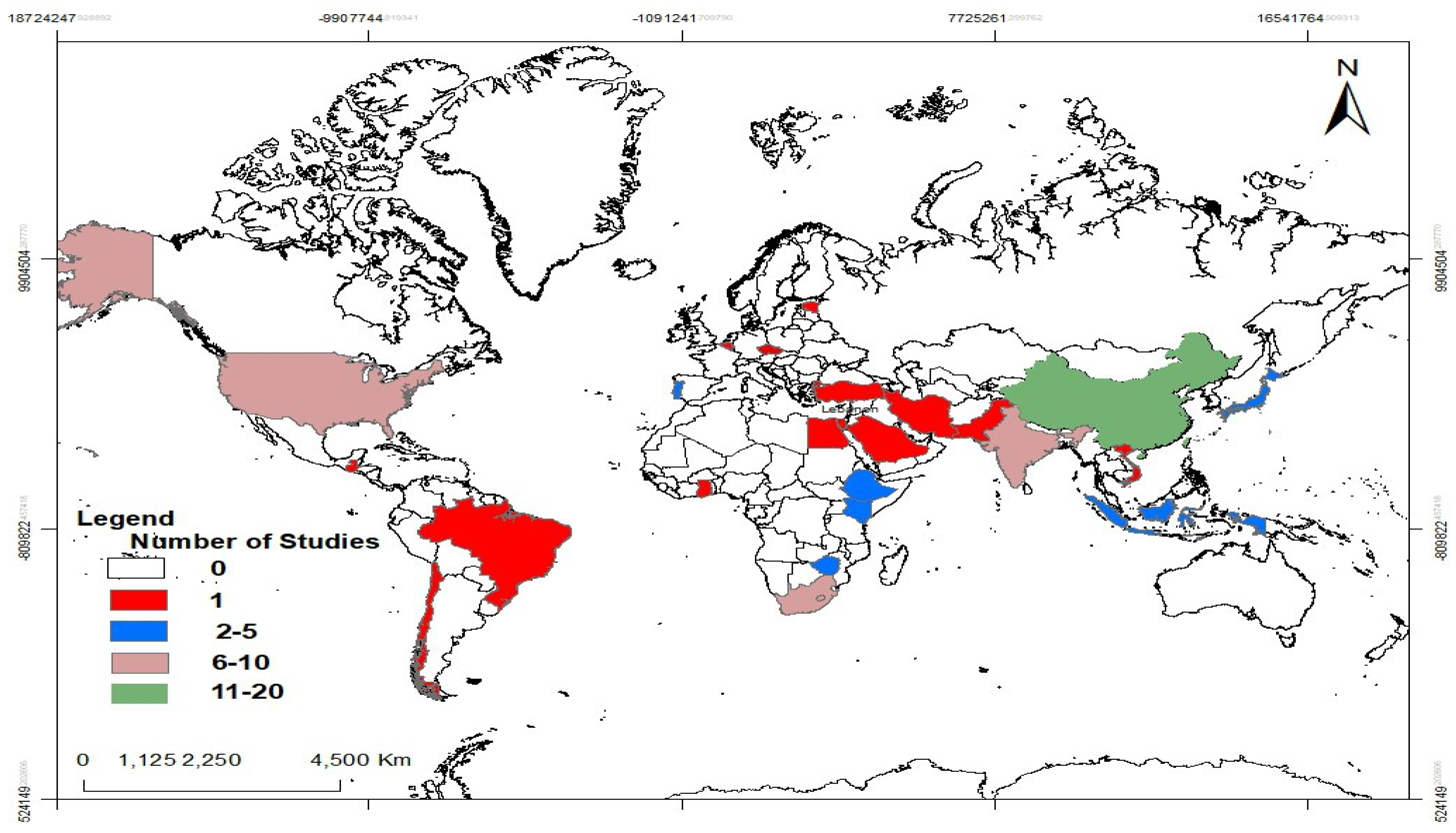

The spatial distribution of research articles on the application of remote sensing technologies for monitoring water hyacinth and water quality, as illustrated in the choropleth map (

Figure 6), reveals notable global patterns. Studies were conducted across five continents Asia, North America, South America, Africa, and Europe, spanning a total of 25 countries.

3.4. Remote Sensing for Water Hyacinth Monitoring

Multispectral sensors have been widely employed in inland water monitoring, offering critical insights into aquatic vegetation and water quality. Operating across visible, near-infrared (NIR), and shortwave infrared (SWIR) bands, these sensors enable effective detection of water hyacinth and related environmental parameters [

36,

37].

Several case studies highlight the application of multispectral data in water hyacinth monitoring. For example, [

25] used Sentinel-2 MSI (bands B3, B4, B8) to map water hyacinth in Lake Tana, Ethiopia, achieving NDVI values between 0.6 and 0.95, indicating dense infestations. Similarly, [

38] identified Sentinel-2 bands 5 to 11 (0.740–1.610 µm) as optimal for detecting water hyacinth in Brazilian reservoirs.[

39] applied Landsat 8 OLI bands 1–3 and 5 to assess inland water quality and vegetation dynamics, successfully delineating water hyacinth presence in Portuguese freshwater systems.

The choice of spectral bands and indices varies by objective, but vegetation indices such as NDVI have proven effective in isolating water hyacinth and turbidity signatures [

2,

13]. More recently, hyperspectral sensors such as Hyperion have enabled finer-scale analysis due to their high spectral resolution (0.4–2.5 µm). [

40] demonstrated Hyperion’s utility in detecting chlorophyll-a concentrations in eutrophic waters, using continuous blue-green band ratios, which also support invasive plant monitoring through pigment analysis.

Modelling Approaches for Water Hyacinth Monitoring

Table 3.

Summery of Methods, Techniques and Overall Accuracy Achieved.

Table 3.

Summery of Methods, Techniques and Overall Accuracy Achieved.

| Method Type |

Techniques |

Accuracy Range |

References |

| Statistical Models |

LR, MLR, LDA |

74% – 95% |

[39,41,42,43,44] |

| Machine Learning |

RF, SVM, CART, KNN, NB |

65% – 98% |

[44,45,46] |

| Deep Learning |

U-Net, Res-U-Net, DeepLabV3+ |

90% – 97% |

[47,48,49,50,51] |

| Hybrid/Index-Based |

DA+PDA, Band Combinations |

82% – 95% |

[50,51] |

3.5. Remote Sensing for Water Quality Assessment

The advancement of remote sensing techniques has significantly increased the number of studies focusing on physical, chemical, and biological water quality parameters across spatial and temporal scales [

35]. In earlier years, multispectral satellite sensors such as MODIS and MERIS were predominantly used for water quality assessment [

35] However, recent findings demonstrate a broader integration of technologies, including multispectral and hyperspectral sensors, unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) equipped with high-resolution cameras, and the application of machine learning algorithms to monitor key water quality parameters.

Among these, Sentinel-2 MSI has been frequently utilized for monitoring three primary water quality indicators.

Table 4 presents the specific water quality parameters investigated during the study period, along with the corresponding satellite sensors employed.

Methods Used for Establishing Inversion Algorithms

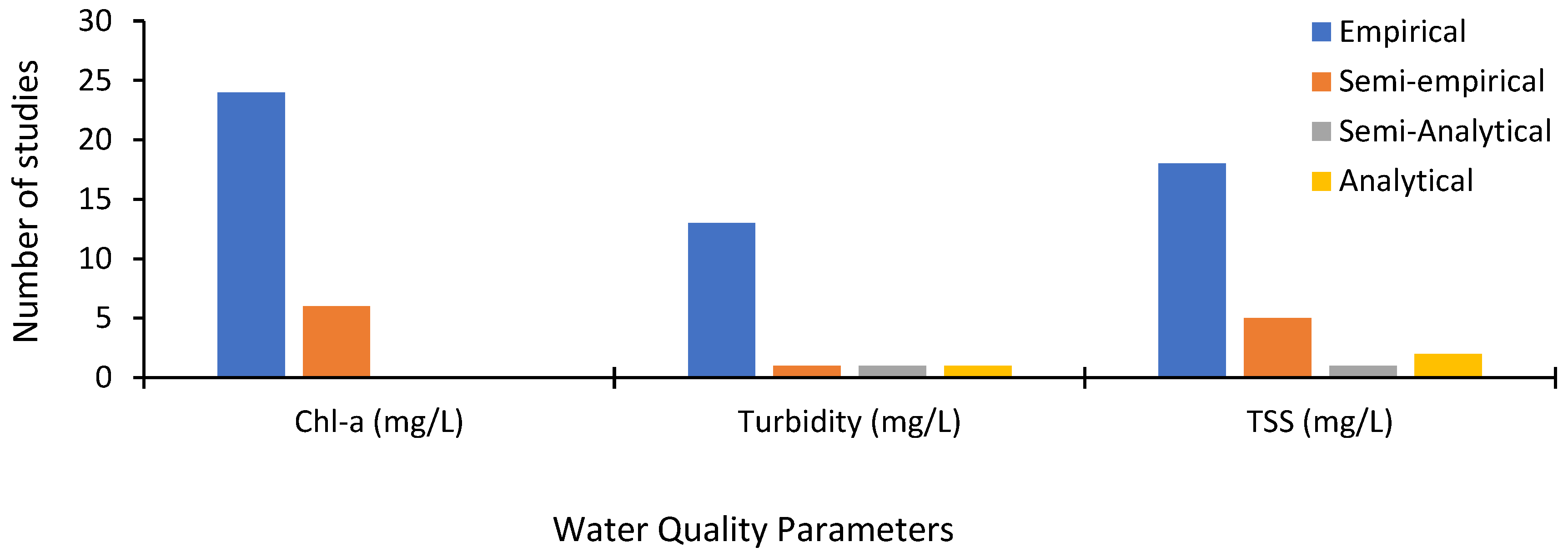

Figure 7 illustrates the number of studies, and the corresponding methods employed to assess water quality parameters. Empirical methods were the most widely used, accounting for 76% of the total studies, followed by semi-empirical methods at 17%. Semi-analytical methods were the least utilized, representing only 3% of the reviewed studies. Analytical and semi-analytical approaches remain relatively rare in water quality research. Instead, a combination of statistical techniques, measured spectral responses, and bio-optical theory has been commonly applied for parameter estimation [

61]. In addition, the review identified that machine learning algorithms have increasingly been used to support empirical approaches, with Random Forest (RF), Support Vector Machine (SVM), Extreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost), and Categorical Boosting (CatBoost) emerging as the most frequently applied models for predicting water quality parameters.

Our review further identified that the empirical method is predominantly applied in the assessment of chlorophyll-a (Chl-a), turbidity, and total suspended solids (TSS). Semi-empirical methods also played a significant role, particularly in studies involving these three parameters. Analytical and semi-analytical methods were occasionally employed, especially in the analysis of turbidity and TSS.

4. Discussion

4.1. Publication Trends

The number of published articles using satellite sensors for inland water monitoring has increased over time. Studies attribute this growth to advancements in remote sensing technology, improved data availability, and enhanced accessibility through cloud-based platforms such as Google Earth Engine (GEE). Additionally, global policy and monitoring initiatives targeting inland water ecosystems have increased interest and led to a significant rise in scholarly publications in water resources monitoring [

32,

62,

63]. Similarly, [

64] reported that the advancement of machine learning techniques has significantly enhanced the classification and modeling capabilities of satellite data, thereby improving the efficiency and effectiveness of inland water monitoring using satellite sensors. As a result, the number of remote sensing-based studies for inland water monitoring has increased in recent years.

Analysis of thematic trends reveals that water quality was the first focus across the study period. The number of studies addressing water quality increased linearly over time, reflecting growing global concerns over environmental degradation and the need for improved surface water monitoring [

61]. [

65]also highlighted that the deterioration of surface water quality poses a major challenge for water resource managers, emphasizing the urgent need for continuous and detailed water quality assessments. Furthermore, the emergence of new contaminants, including microplastics, has intensified global attention on water quality. This shift aligns with international environmental commitments, initially under the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) and currently within the framework of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) [

66] . In response, remote sensing-based studies on water quality have increased, aiming to address global water quality issues and support sustainable inland water management.

The emphasis on lakes in remote sensing applications is largely due to their relatively larger surface area and spatial continuity, which make them more suitable for satellite-based monitoring. Additionally, the global availability of long-term remote sensing data, along with the ecological importance and relevance of lakes in addressing global environmental challenges, has contributed to their prioritization in scientific research [

67,

68,

69] .

Similarly, water hyacinth-related studies have shown a steady increase and were conducted every year throughout the review period. Water hyacinth, which is now found on every continent except Antarctica, has drawn scientific interest due to its widespread ecological impact [

70]. [

29] demonstrated a linear growth in the number of satellite-based studies

Remote sensing applications for monitoring water hyacinth and water quality have been documented across five continents Asia, North America, South America, Africa, and Europe, covering 25 countries. This global distribution reflects growing recognition of aquatic ecosystem degradation and the value of satellite-based monitoring. In Asia, China, India, Pakistan, and Taiwan are major contributors, with China leading the region. The rise in publications is driven by industrialization, increasing water demand, and policy shifts toward improved resource management [

71] In North America, the United States dominates research output, followed by Guatemala. The U.S. also demonstrates strong international collaborations, particularly with India, advancing shared methods and datasets for global monitoring [

35]. In South America, Brazil and Chile are primary contributors. Brazil, covering much of the Amazon Basin and historically impacted by water hyacinth, has played a key role in developing remote sensing approaches tailored to tropical aquatic systems.

In Africa, South Africa leads, followed by Kenya, Ethiopia, and Zimbabwe. Research is supported by growing use of Landsat and Sentinel data to address pollution, eutrophication, and invasive species in inland waters [

72]. In Europe, studies from Portugal, Belgium, Estonia, Turkey, and Czechia are notable. Portugal utilizes multispectral data from the Copernicus Sentinel-2 program, reflecting the region’s strong engagement with open-access geospatial technologies.

Overall, the research landscape is globally distributed but spatially uneven. While countries like China, the U.S., and South Africa serve as hubs, many regions remain underrepresented. Addressing this imbalance requires targeted investment in research capacity and geospatial infrastructure in low- and middle-income countries. Expanding the geographic reach of remote sensing will support more equitable and comprehensive monitoring of freshwater ecosystems.

4.2. Satellite Sensors used for Monitoring

This growing adoption is primarily attributed to Sentinel-2 MSI’s design tailored for environmental monitoring, offering high spatial resolution (10 m), frequent revisit times, and advanced capabilities for water quality assessment, aquatic vegetation detection, and mapping the extent of water bodies [

73,

74,

75] . Similarly, [

52] successfully demonstrated the suitability of Sentinel-2 MSI imagery for monitoring inland water quality, highlighting its potential for application in various freshwater systems globally.

On the other hand, Landsat 8 OLI was the second most used satellite sensor, appearing in 18 studies during the review period (

Figure 4a). Its widespread application is largely attributed to its extensive historical archive, moderate spatial resolution (30 meters), and freely accessible, open-source data, making it a valuable resource for researchers around the world. The sensor provides global coverage every 16 days, allowing for consistent monitoring of inland water bodies. Landsat 8 OLI is equipped with key spectral bands Blue, Green, Red, NIR, and SWIR which are particularly effective for detecting water hyacinth and retrieving important water quality parameters such as chlorophyll-a (Chl-a), turbidity, and total suspended solids (TSS). According to [

76] , the long-term use of Landsat 8 has played a critical role in inland water monitoring, primarily due to its moderate spatial resolution and consistent, long-term data availability. As a result, Landsat 8 OLI has become a widely trusted data source for researchers, particularly in regions with limited or inconsistent ground-based observations. Its openly accessible archive allows for retrospective analysis, enabling the study of temporal trends and long-term ecological changes [

22].

Achieving enhanced spatial and temporal resolution is essential for supporting environmental decision-making and advancing research in inland water monitoring [

77]. To address the limitations of individual sensors such as coarse spatial resolution, low revisit frequency, and cloud interference researchers have increasingly adopted image fusion techniques. These approaches combine datasets from multiple sensors to produce composite imagery with improved spatial and temporal detail [

74,

78].

These methods were primarily implemented in Asian inland water bodies, particularly in China, for the retrieval of key water quality parameters and to support water resource management and policy development decisions [

36,

79,

80] . The combined application of UAV imagery and Sentinel-2 MSI enables the generation of high-resolution, multi-scale datasets, facilitating more detailed and accurate assessments of inland aquatic environments.

4.3. Trends in Journal Publications

Overall, the distribution of publications underscores the expanding application of remote sensing technologies in environmental research, particularly in geospatial data analysis. The predominance of Remote Sensing as a leading publication place reflects the growing emphasis on spatial and temporal analysis in the study of inland and global water bodies

The diversity of journals highlights the interdisciplinary nature of the field, spanning environmental science, remote sensing, hydrology, and ecological monitoring.

Among the highest-ranking outlets, Nature stood out with an exceptional IF of 69.0 and SJR of 18.786, reflecting its status as a premier multidisciplinary journal. Environmental Science & Technology (IF = 11.3, SJR = 2.625, CiteScore = 14.8) and Marine Pollution Bulletin (IF = 8.0, SJR = 1.748, CiteScore = 9.1) were also identified as leading Q1 journals, frequently publishing high-impact research on water quality and environmental pollution.

Journals such as Ecological Indicators (IF = 7.4), Journal of Hydrology (IF = 5.9), and Drones (IF = 4.8) were consistently ranked in Q1, emphasizing their relevance in ecological assessment, hydrological analysis, and remote sensing applications. Their strong CiteScores (6.0–8.6) indicate sustained scholarly engagement.

Remote Sensing (MDPI) emerged as a major open-access platform (IF = 4.2, CiteScore = 5.1, Q1), widely used for publishing studies with spatial and temporal focus. Other MDPI journals such as Water (IF = 3.0), Sensors (IF = 3.5), Plants (IF = 4.1), and Sustainability (IF = 2.6) provided accessible outlets with moderate to high impact and relatively faster publication timelines, primarily in Q1–Q2 categories.

Additional journals included Ecological Informatics (IF = 5.0, Q1), focused on ecological modelling, and the Egyptian Journal of Remote Sensing and Space Sciences (IF = 4.1, Q2), which supports regionally focused studies. Lower-level journals like Environmental Monitoring and Assessment (IF = 2.5, Q3), Desalination and Water Treatment (IF = 1.0, Q4), and Invasive Plant Science & Management (IF = 1.5, Q2) were also present but contributed fewer citations (

Table 2).

In comparison, Elsevier and Springer journals consistently ranked higher in terms of SJR and CiteScore, indicating stronger academic influence, while MDPI journals offered wider accessibility and faster dissemination.

4.4. Spatial and Temporal Variability of Water Hyacinth Expansion

The spatial and temporal coverage of water hyacinth (Eichhornia crassipes) varies considerably across regions and seasons, driven by both environmental and anthropogenic factors growth [

45,

70,

81]. Despite decades of control efforts, remote sensing evidence indicates that water hyacinth infestations in freshwater ecosystems are not only persisting but expanding globally [

2,

5].

Water hyacinth coverage has shown significant seasonal and interannual variability across freshwater systems. In Vietnam’s Saigon River, the weed occupied up to 24% of the river surface in upstream sections during the dry season [

82]. In Ethiopia’s Lake Tana, infestation expanded sharply from less than 10,000 hectares in 2011 to nearly 50,000 hectares by 2017 [

83,

84], with localized growth from 112.1 ha in 2013 to 1,512 ha by 2017 [

85]. The northern part of the lake, previously unaffected in 2010, reached over 1,360 ha by 2019, growing at an average rate of 136 ha per year [

86]. Short-term assessments using MODIS data revealed rapid fluctuations, with increases of 14 ha/day between August and November 2017, followed by a decline of 6 ha/day during subsequent removal efforts [

81].

Sentinel-2 observations captured similar dynamics in Lake Tana, showing an increase from 278 ha in February 2015 to over 2,050 ha by December 2019 [

87]. These fluctuations highlight the influence of seasonal variability, cloud cover, acquisition timing, and the plant’s mobility.

Environmental drivers such as eutrophication, water level changes, and temperature regimes play a central role in the weed’s proliferation [

87,

88]. Optimal growth has been reported at surface water temperatures of 28–30 °C and nighttime air temperatures of 13–19 °C [

8,

81] though persistence has been observed at lower temperatures, down to 12 °C [

39], indicating a broader thermal tolerance.

Lake morphology and water quality further influence infestation dynamics. Shallow systems (<6 m depth) are particularly vulnerable, with seasonal variation linked to pH levels (6.5–8.5), nitrate concentrations (5.5–20 mg/L), phosphate (1.66–3 mg/L), and potassium levels up to 55 mg/L [

4].

Advancements in remote sensing technologies, particularly when integrated with machine learning algorithms, have enhanced the capacity to detect, map, and monitor water hyacinth infestations with high spatial and temporal resolution. These tools offer critical support for developing data-driven management strategies [

51,

89,

90,

91].

4.4.1. Modelling Approaches for Water Hyacinth Monitoring

Traditional statistical methods have long been used in the classification of water hyacinth due to their simplicity and interpretability. Techniques such as Linear Regression (LR), Multiple Linear Regression (MLR), and Linear Discriminant Analysis (LDA) rely on assumptions of linearity and statistical independence. LR has been successfully applied in remote sensing contexts, with [

81] reporting 91% overall accuracy and [

41] achieving 95% using MODIS and Sentinel-2 data, respectively. MLR, using Landsat 8 imagery, yielded an 85% accuracy in [

42]. LDA, used by [

92] and [

43], produced comparatively lower accuracies ranging from 74% to 81%, likely due to its assumption of equal class covariances. While computationally efficient and easily interpretable, these methods are often limited in complex environments where nonlinear relationships dominate, and they can be sensitive to multicollinearity and outliers [

93,

94].

Machine learning (ML) methods have gained significant traction due to their ability to model complex, non-linear patterns without relying on strict statistical assumptions. Among the most widely used is the Random Forest (RF) classifier, which has demonstrated accuracies between 90% and 98% in water hyacinth classification tasks [

44]. RF is known for its robustness to overfitting and ability to handle high-dimensional, multivariate datasets [

90,

95]. Support Vector Machines (SVM) have also been employed effectively, with reported accuracies ranging from 65% to 94%, depending on kernel selection and data properties [

7,

39]. Other ML approaches such as Classification and Regression Trees (CART), K-Nearest Neighbors (KNN), and Naive Bayes (NB) have shown moderate performance, with accuracies between 83% and 87% [

39]. Although simple to implement, KNN and NB tend to underperform on large-scale or noisy datasets due to their basic conceptual frameworks.

Deep learning (DL) techniques have recently been adopted in water hyacinth mapping to improve classification precision. Convolutional neural network architectures, including U-Net, Res-U-Net, and DeepLabV3+, have achieved remarkable results. For instance, [

47] applied U-Net to multispectral images from a self-assembled sensor system, achieving 97% accuracy. Similarly, Res-U-Net applied to Sentinel-2 data reached 90% accuracy [

96], while DeepLabV3+ using MODIS and MERIS datasets attained 95% accuracy [

49]. These models are particularly effective in capturing spatial and spectral features but require large, annotated datasets and substantial computational resources [

32].

Hybrid models offer a compromise between model complexity and practicality. For example, [

50] applied a combined Discriminant Analysis (DA) and Partial Discriminant Analysis (PDA) approach to Landsat 8 data, achieving 95% accuracy. Simpler two-band index combinations using Sentinel-2 imagery also demonstrated effectiveness, yielding up to 82% accuracy [

51].

Overall, the literature reveals a clear trend toward more sophisticated classification models, from statistical techniques to machine and deep learning. While advanced models generally offer higher accuracy, they also demand greater computational power, larger datasets, and technical expertise [

46,

97]. Therefore, the choice of classification method should consider the specific project context, including target accuracy, data availability, and computational constraints [

98]. Although machine learning and deep learning approaches are currently the most accurate, traditional and hybrid methods remain valuable, particularly in resource-limited settings or where training data are scarce [

99]. Continued research is needed to advance adaptive, ensemble, and hybrid frameworks that balance performance with accessibility and scalability across diverse ecological monitoring scenarios [

47].

4.5. Remote Sensing for Water Quality Assessment

4.5.1. Chlorophyll-a

Chlorophyll-a (Chl-a) is a widely used indicator for assessing the trophic status of freshwater bodies, as its concentration reflects phytoplankton biomass and overall water quality [

100,

101]. Elevated Chl-a levels are often linked to harmful algal blooms that can deplete dissolved oxygen, release toxins, and pose significant risks to aquatic ecosystems and public health [

35] .

Remote sensing platforms such as Sentinel-2 MSI and Landsat 8 OLI are particularly effective for Chl-a detection due to their spectral bands in the blue (430–450 nm) and red (660–670 nm) wavelengths [

100,

102]. For instance, [

103] recorded a Chl-a concentration of 292.2 mg/L in the Poteran Islands (Indonesia), while [

104] reported 94 mg/L in a lake in Czechia, with corresponding model performances (R²) of 0.58 and 0.90. In Lake Peipsi (Estonia), [

52] reported 23.4 mg/L with an R² of 0.83.

Conversely, significantly lower Chl-a concentrations have been reported in post-rainy season studies using Sentinel-2 MSI. These include values of 0.001 mg/L, 0.004 mg/L, and 0.06 mg/L with strong model performances (R² = 0.86, 0.97, and 0.75, respectively) [

63,

105,

106]. In China’s Karst wetlands, [

98] applied deep learning models integrating multi-sensor, multi-platform remote sensing data and found a mean Chl-a concentration of 0.26 mg/L (R² = 0.93). The study noted that 32.66% of the water surface exceeded the pollution threshold of 0.06 mg/L, indicating significant water quality concerns.

Spatial heterogeneity can affect remote sensing accuracy. For example, [

105] reported an underestimation of Chl-a (26 µg/L) in Lake Taihu, China, due to its complex spatial structure. In Turkey’s Borabey Dam, hyperspectral imagery produced a Chl-a estimate of 0.9 mg/L with a high model fit (R² = 0.96), highlighting the value of red-edge bands and high-resolution sensors [

107]. Similarly, [

108] reported 1.54 mg/L in Utah Lake (USA) using a combined approach with Landsat 8 OLI, Sentinel-2 MSI, and MODIS Terra.

In Lake Sergoit, Kenya, [

22] used a combined Sentinel-2 and Landsat 8 approach and reported a Chl-a concentration of 2.56 mg/L, though with modest model performance (R² = 0.51). In Ethiopia’s Lake Tana, [

25] applied Sentinel-2A/B imagery and reported a mean Chl-a value of 8.5 mg/L with a strong fit (R² = 0.85), confirming the sensor’s suitability for inland water quality monitoring when appropriate atmospheric corrections are applied.

Therefore, the selection of satellite imagery for Chlorophyll-a estimation depends on factors such as spatial and temporal resolution requirements, the size and heterogeneity of the water body, specific research objectives, and resource availability [

109]. Sentinel-2 MSI and Landsat 8 OLI offer a practical balance between spatial resolution and coverage, making them well-suited for both routine monitoring and large-scale water quality assessment [

110].

4.5.2. Turbidity

Turbidity is one of the most frequently assessed parameters in inland water monitoring using satellite remote sensing [

22] . It represents the extent to which light penetrates the water column and is closely associated with the presence of suspended particulates, including silt, clay, organic matter, algae, and microorganisms [

60]. As a key water quality indicator, turbidity influences underwater light availability, which in turn affects photosynthesis, thermal structure, and the overall ecological integrity of aquatic systems [

111,

112].

Optically, turbid waters exhibit heightened reflectance in the visible spectrum, particularly in the green (~550 nm) and red (~660 nm) wavelengths due to increased backscattering from suspended solids. With rising turbidity, reflectance in the near-infrared (NIR) region also increases, driven by stronger scattering effects [

113] .

In Ethiopia’s Lake Tana, [

81] reported a maximum turbidity value of 348 NTU in the northern basin, though model performance was modest (R² = 0.27). In contrast, a study in India’s Chilika Lake using a spectral similarity approach and multispectral sensors recorded 178 NTU with stronger model accuracy (R² = 0.80) [

112] . Multiple studies in China reported varying turbidity values 150 NTU [

113], 121 NTU [

114], 60 NTU [

115] , 18.07 NTU [

79] , and 16.9 NTU [

116] highlighting spatial heterogeneity. The highest values were derived from Sentinel-2 MSI and UAV-mounted RGB imagery, emphasizing the role of sensor type and spatial resolution in turbidity estimation.

Lower turbidity levels were also observed in other contexts. For example, [

98] reported a minimum value of 1.31 NTU in Turkey using RapidEye imagery, while [

60] recorded 3.66 NTU in Florida using high-resolution multispectral sensors and empirical modeling.

Overall, the use of multispectral and hyperspectral sensors has enabled effective turbidity monitoring across diverse aquatic environments from small rivers and wetlands to large lakes. However, turbidity values vary significantly across regions and seasons, primarily influenced by environmental drivers such as rainfall, sediment influx, and nutrient loading.

4.5.3. Total Suspended Solids

The spectral response of Total Suspended Solids (TSS) varies across different regions of the electromagnetic spectrum, particularly in the blue (400–495 nm), green (495–570 nm), red (620–750 nm), and near-infrared (>750 nm) wavelengths [

117] . These variations are influenced by particle size, concentration, and composition.

Among reviewed studies, the highest TSS concentration 2511 mg/L was recorded in India using Sentinel-2 MSI and semi-empirical methods [

33] . Similarly,[

113] reported 416 mg/L, in Taiwanese river using the same sensor and empirical methods while [

118] recorded 71.2 mg/L using hyperspectral sensors and semi-empirical models. Notably, [

33] applied a novel approach integrating Google Earth Engine (GEE) and spectral indices to estimate TSS post-rainy season, highlighting the potential of user-oriented visualization tools for environmental monitoring. Extremely high TSS values, up to 2627 mg/L, have been reported in global studies across lakes, rivers, and estuaries [

119,

120]. indicating the variable nature of TSS influenced by hydrological and seasonal dynamics.

Overall, findings from this review indicate significant spatial and temporal variability in TSS concentrations, emphasizing the influence of local environmental conditions. The integration of emerging technologies particularly machine learning enhances the retrieval accuracy and predictive capacity of satellite-based TSS monitoring.

4.5.4. Spatiotemporal Variability of Water Quality Parameters

Understanding the spatial and temporal variability of water quality is critical for the sustainable management of freshwater systems that support drinking water supply, irrigation, hydropower, and recreational activities. Declining water quality poses serious ecological, health, and environmental risks, often limiting the suitability of water bodies for these uses [

35]. Variability in water quality is primarily influenced by climatic conditions and anthropogenic activities such as land use change, urbanization, and agricultural runoff.

In Ethiopia’s Lake Tana, remote sensing observations during the dry season revealed that elevated temperatures were associated with increased concentrations of chlorophyll-a (Chl-a) and suspended matter, indicating strong seasonal influences on water quality dynamics [

121]. Similarly, a long-term analysis of the Yangtze River Basin in China (2006–2018) using Landsat ETM+ imagery found a significant relationship between land use patterns and water quality parameters, underscoring the impact of watershed development on aquatic conditions [

122] . Sensor selection has also been shown to affect detection accuracy; for example, [

108] demonstrated that choosing appropriate sensors was critical to capturing spatiotemporal variability in Utah Lake and the Great Salt Lake, USA.

In Sri Lanka, [

123] developed a remote sensing-based water quality index for Beira Lake, successfully tracking changes between 2016 and 2023 using multispectral imagery. In Turkey, [

124] reported higher Chl-a concentrations in the northern region of Lake Burdur, attributing these spatial patterns to land use alterations in the surrounding watershed. Likewise, in Chile, [

125] integrated in situ data with Landsat 8 OLI imagery to monitor eutrophication processes in an urban lake, highlighting the value of combined data approaches.

A recent study on Lake Koka in Ethiopia using Sentinel-2 MSI imagery illustrated pronounced spatial and seasonal variation in key water quality indicators [

126]. Monthly Chl-a concentrations ranged from 59.69 to 144.25 µg/L, turbidity from 79.67 to 115.39 NTU, and total suspended solids (TSS) from 38.46 to 368.97 mg/L. Spatially, the highest Chl-a levels were observed in the southern and southeastern zones of the lake, while turbidity and TSS peaked along the western shoreline, reflecting the heterogeneous nature of water quality in the system.

These findings collectively emphasize the importance of integrating spatial and temporal perspectives in remote sensing-based water quality monitoring. Such approaches improve the ability to detect trends, assess the impact of land and climate dynamics, and support more informed management and policy decisions across diverse aquatic environments.

4.6. Challenges and Gaps of Remote Sensing Applications

Remote sensing has emerged as a powerful tool for monitoring inland water bodies, offering broad spatial coverage and temporal consistency. However, several challenges and research gaps continue to constrain its full potential in water quality and aquatic vegetation assessments. One prominent issue is the limited understanding and inconsistent application of sensor-specific characteristics and image processing protocols, particularly atmospheric correction procedures [

127,

128]. Many reviewed studies applied differing correction methods, while others relied solely on top-of-atmosphere (TOA) reflectance without performing atmospheric correction. Such inconsistencies can introduce significant errors in the estimation of water quality indices, compromising the reliability of results.

Another critical limitation is the insufficient validation of remote sensing outputs. Approximately 10% of the reviewed studies lacked proper validation through in situ ground-truth data. This shortfall is often attributed to challenges such as limited field access, adverse seasonal weather conditions, and the unavailability of reliable ground-based measurements. The absence of validation reduces the credibility of remote sensing–derived estimates and hampers their integration into management frameworks.

Furthermore, research has disproportionately focused on large water bodies such as lakes, reservoirs, and major rivers, while ecologically significant small water bodies including ponds, wetlands, and small rivers remain underrepresented in remote sensing studies. These smaller systems, despite their importance for biodiversity and local water supply, are often overlooked due to limitations in sensor resolution and methodological design.

In summary, while remote sensing holds significant promise for water hyacinth mapping and inland water quality monitoring, its broader application is constrained by methodological inconsistencies, limited data availability, inadequate validation procedures, and under exploration of small water bodies and optically inactive parameters.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, the global application of remote sensing technologies for monitoring water hyacinth and water quality in inland aquatic ecosystems has expanded considerably. Of the studies reviewed, 61.5% focused on lakes, 21% on rivers, 10.3% on wetlands, and 7.7% addressed both lakes and rivers. Nearly half (49%) of the studies targeted water quality assessment, while 42% focused on mapping water hyacinth and estimating its biomass while the remaining 9% examined both.

Spatial distribution analysis revealed that China, India, South Africa, and the United States lead in the application of remote sensing technologies for aquatic monitoring. Sentinel-2 MSI emerged as the most widely used satellite sensor, followed by Landsat 8 OLI and UAV-mounted RGB cameras for the whole review period. Notably, the combination of UAV-mounted RGB sensors with Sentinel-2 MSI was the most frequently employed setup used for chlorophyll-a (Chl-a) retrieval. Sentinel-2 MSI and Landsat 8 OLI have also been extensively used to detect Chl-a, turbidity, and water hyacinth infestations.

In terms of modelling approaches, linear regression (LR), multiple linear regression (MLR), and linear discriminant analysis (LDA) achieved mapping accuracies ranging from 74% to 95%. Machine learning algorithms such as random forest (RF), support vector machine (SVM), classification and regression trees (CART), k-nearest neighbours (KNN), and naive Bayes (NB) demonstrated a broader accuracy range of 65% to 98%. More recently, deep learning architectures, including U-Net, ResU-Net, and DeepLabV3, have enhanced mapping accuracy up to 97% in water hyacinth studies.

However, around 10% of the reviewed studies did not apply appropriate validation techniques or atmospheric correction procedures, which compromise the accuracy and reliability of their results. To address this gap, future research should focus more on underrepresented small and medium-sized inland water bodies and broaden the scope of remote sensing applications to include optically inactive water quality parameters, such as nutrients and dissolved oxygen.

As a final remark, the integration of multi-source datasets particularly UAV-based observations with advanced machine learning and deep learning models holds substantial promise for enhancing the accuracy of remote sensing analyses. This approach could also serve as a reliable ground-truthing mechanism to validate and support satellite-based water quality and vegetation monitoring. Expanding the search to include additional databases such as Dimensions, Microsoft Academic, ProQuest, and grey literature from institutional repositories would improve coverage. Moreover, while this review focused on selected key optically active water quality parameters, future studies should consider both optically active and non-optically active parameters to better capture global water quality dynamics. Finally, incorporating non-English language publications would help include valuable regional studies often overlooked in global syntheses.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org, Table S1: Summary of multispectral sensors and their characteristics; Table S2: Summary of Studies on Chl-a with Methods and Sensors Applied; Table S3: Summary of Studies on Turbidity with Methods and Sensors Applied; Table S4: Summary of Studies on TSS with Methods and Sensors Applied.

Author Contributions

Lakachew Y. Alemneh: Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal analysis, Writing—original draft, Visualization; Daganchew Aklog: Supervision, Data interpretation, Writing—review and editing, Validation, Final approval; Ann van Griensven: Supervision, Writing—review and editing, Validation, Final approval; Goraw Goshu: Supervision, Project administration, Writing—review and editing; Seleshi Yalew: Methodology, Supervision, Project administration, Writing—review and editing; Wubneh Belete: Writing—review and editing, Critical revision of the manuscript for intellectual content; Mnichyl G. Dersseh: Data curation, Supervision, Writing—review and editing; Demesew A. Mhiret: Methodology, Software, Spatial analysis, Drafting of figures. Claire Mikhailovsky: Funding acquisition, Writing—review and editing, Critical revision for intellectual content; Selamawit Damtew: Data analysis, Writing—review and editing and Sisay Asress: Formal analysis, Writing—review and editing.

All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Water and Development Partnership Program (WDPP) under the large-scale project Remote Sensing for Community-driven Applications: from WA+ to Co-learning (RS-4C), grant number 111362. The article processing charge (APC) was supported by IHE Delft Institute for Water Education, Westvest 7, 2611 AX Delft, The Netherlands.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/supplementary material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the Bahir Dar Institute of Technology, Bahir Dar University, and the Blue Nile Water Institute for providing institutional guidance and support. Special thanks are extended to the IHE Delft Institute for Water Education for its valuable support in training and capacity building related to this work. Finally, sincere gratitude is expressed to Mr. Bantesew Muluye for his unwavering support and continuous encouragement throughout the study

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Hill, M.P.; Coetzee, J.A. Integrated Control of Water Hyacinth in Africa. EPPO Bulletin 2008, 38, 452–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabir, H.; Juthi, T.; Islam, M.T.; Rahman, M.W.; Khan, R. WaterHyacinth: A Comprehensive Image Dataset of Various Water Hyacinth Species from Different Regions of Bangladesh. Data Brief 2024, 52, 109872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, J.; Jiao, C.; Mekonnen, M.; Legesse, S.A.; Ishikawa, K.; Wondie, A.; Sato, S. Water Hyacinth Infestation in Lake Tana, Ethiopia: A Review of Population Dynamics. Limnology (Tokyo) 2023, 24, 51–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaikwad, R.P.; Gavande, S. Major Factors Contributing Growth of Water Hyacinth in Natural Water Bodies. International Journal of Engineering Research 2017, 6, 304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiyemba, H.; Barasa, B.; Asaba, J.; Makoba Gudoyi, P.; Akello, G. Water Hyacinth’s Extent and Its Implication on Water Quality in Lake Victoria, Uganda. Scientific World Journal 2023, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitan, N.M.M. Water Hyacinth: Potential and Threat. Mater Today Proc 2019, 19, 1408–1412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukarugwiro, J.A.; Newete, S.W.; Adam, E.; Nsanganwimana, F.; Abutaleb, K.A.; Byrne, M.J. Mapping Distribution of Water Hyacinth (Eichhornia Crassipes) in Rwanda Using Multispectral Remote Sensing Imagery. Afr J Aquat Sci 2019, 44, 339–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dersseh, M.G.; Melesse, A.M.; Tilahun, S.A.; Abate, M.; Dagnew, D.C. Water Hyacinth: Review of Its Impacts on Hydrology and Ecosystem Services-Lessons for Management of Lake Tana; Elsevier Inc., 2019; Vol. 1824; ISBN 9780128159989.

- Whitehead, K.; Hugenholtz, C.H.; Myshak, S.; Brown, O.; Leclair, A.; Tamminga, A.; Barchyn, T.E.; Moorman, B.; Eaton, B. Remote Sensing of the Environment with Small Unmanned Aircraft Systems (Uass), Part 2: Scientific and Commercial Applications. J Unmanned Veh Syst 2014, 2, 86–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toth, C.; Jóźków, G. Remote Sensing Platforms and Sensors: A Survey. ISPRS Journal of Photogrammetry and Remote Sensing 2016, 115, 22–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaywant, S.A.; Arif, K.M. Remote Sensing Techniques for Water Quality Monitoring: A Review. Sensors 2024, 24, 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishida, H.; Oishi, Y.; Morita, K.; Moriwaki, K.; Nakajima, T.Y. Development of a Support Vector Machine Based Cloud Detection Method for MODIS with the Adjustability to Various Conditions. Remote Sens Environ 2018, 205, 390–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gitelson, A.A.; Peng, Y.; Huemmrich, K.F. Relationship between Fraction of Radiation Absorbed by Photosynthesizing Maize and Soybean Canopies and NDVI from Remotely Sensed Data Taken at Close Range and from MODIS 250m Resolution Data. Remote Sens Environ 2014, 147, 108–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lymburner, L.; Botha, E.; Hestir, E.; Anstee, J.; Sagar, S.; Dekker, A.; Malthus, T. Landsat 8: Providing Continuity and Increased Precision for Measuring Multi-Decadal Time Series of Total Suspended Matter. Remote Sens Environ 2016, 185, 108–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thamaga, K.H.; Dube, T. Understanding Seasonal Dynamics of Invasive Water Hyacinth (Eichhornia Crassipes) in the Greater Letaba River System Using Sentinel-2 Satellite Data. GIsci Remote Sens 2019, 56, 1355–1377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medina-Lopez, E.; McMillan, D.; Lazic, J.; Hart, E.; Zen, S.; Angeloudis, A.; Bannon, E.; Browell, J.; Dorling, S.; Dorrell, R.M.; et al. Satellite Data for the Offshore Renewable Energy Sector: Synergies and Innovation Opportunities. Remote Sens Environ 2021, 264, 112588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moges, M.A.; Schmitter, P.; Tilahun, S.A.; Ayana, E.K.; Ketema, A.A.; Nigussie, T.E.; Steenhuis, T.S. Water Quality Assessment by Measuring and Using Landsat 7 ETM+ Images for the Current and Previous Trend Perspective: Lake Tana Ethiopia. J Water Resour Prot 2017, 09, 1564–1585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, B.; Lao, Z.; Liang, Y.; Sun, J.; He, X.; Deng, T.; He, W.; Fan, D.; Gao, E.; Hou, Q. Evaluating Optically and Non-Optically Active Water Quality and Its Response Relationship to Hydrometeorology Using Multi-Source Data in Poyang. 2022, 145. [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Zhang, Y.; Shi, K.; Zhang, Y.; Li, N.; Wang, W.; Huang, X.; Qin, B. Monitoring Water Quality Using Proximal Remote Sensing Technology. Science of the Total Environment 2022, 803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dapke, P.P.; Quadri, S.A.; Nagare, S.M.; Bandal, S.B.; Baheti, M.R. A Literature Review on Watershed Management Using Remote Sensing And. International Journal of Computer Science and Information Security (IJCSIS) 2024, 22, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Hestir, E.L.; Khanna, S.; Andrew, M.E.; Santos, M.J.; Viers, J.H.; Greenberg, J.A.; Rajapakse, S.S.; Ustin, S.L. Identification of Invasive Vegetation Using Hyperspectral Remote Sensing in the California Delta Ecosystem. Remote Sens Environ 2008, 112, 4034–4047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouma, Y.O.; Noor, K.; Herbert, K. Modelling Reservoir Chlorophyll- a, TSS, and Turbidity Using Sentinel-2A MSI and Landsat-8 OLI Satellite Sensors with Empirical Multivariate Regression. J Sens 2020, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerardo, R.; de Lima, I.P. Assessing the Potential of Sentinel-2 Data for Tracking Invasive Water Hyacinth in a River Branch. J Appl Remote Sens 2022, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sari, D.N.; Wismoyo, G.S. Spatio-Temporal Analysis of Water Hyacinth Density (Eichhornia Crassipes) in Lake Rawa Pening 2019 - 2023 Using NDVI Algorithm on Google Earth Engine (GEE). IOP Conf Ser Earth Environ Sci 2024, 1406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tadesse Mucheye Water Quality and Water Hyacinth Monitoring with The. remote sensing Article 2022.

- Belayhun, M.; Chere, Z.; Abay, N.G.; Nicola, Y.; Asmamaw, A. Spatiotemporal Pattern of Water Hyacinth (Pontederia Crassipes) Distribution in Lake Tana, Ethiopia, Using a Random Forest Machine Learning Model. 2024, 1–13. [CrossRef]

- Singh, G.; Reynolds, C.; Byrne, M.; Rosman, B. A Remote Sensing Method to Monitor Water, Aquatic Vegetation, and Invasive Water Hyacinth at National Extents. Remote Sens (Basel) 2020, 12, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, T.; Zounemat-Kermani, M.; Scholz, M. Climate Change, Water Quality and Water-Related Challenges: A Review with Focus on Pakistan. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2020, 17, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thamaga, K.H.; Dube, T. Remote Sensing of Invasive Water Hyacinth (Eichhornia Crassipes): A Review on Applications and Challenges. Remote Sens Appl 2018, 10, 36–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Worku, M.; Sahile, S. Impact of Water Hyacinth, Eichhornia Crassipes (Martius) (Pontederiaceae) in Lake Tana Ethiopia: A Review. J Aquac Res Dev 2017, 09. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Photocatalysis, V. Sustainable Development of ZnO Nanostructure Doping with Water Hyacinth-Derived Activated Carbon For. 2024, 1–14.

- Amani, M.; Ghorbanian, A.; Ahmadi, S.A.; Kakooei, M.; Moghimi, A.; Mirmazloumi, S.M.; Moghaddam, S.H.A.; Mahdavi, S.; Ghahremanloo, M.; Parsian, S.; et al. Google Earth Engine Cloud Computing Platform for Remote Sensing Big Data Applications: A Comprehensive Review. IEEE J Sel Top Appl Earth Obs Remote Sens 2020, 13, 5326–5350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, S.; Nandi, D.; Thakur, R.R.; Bera, D.K.; Behera, D.; Đurin, B.; Cetl, V. A Novel Approach for Ex Situ Water Quality Monitoring Using the Google Earth Engine and Spectral Indices in Chilika Lake, Odisha, India. ISPRS Int J Geoinf 2024, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; Mckenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 Statement: An Updated Guideline for Reporting Systematic Reviews Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses. Research Center for Eco-environmental Sciences, 2021, II, 7–16. [CrossRef]

- Ngwenya, N.; Bangira, T.; Sibanda, M.; Kebede Gurmessa, S.; Mabhaudhi, T. Trends in Remote Sensing of Water Quality Parameters in Inland Water Bodies: A Systematic Review. Geocarto Int 2025, 40, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro, C.C.; Gómez, J.A.D.; Martín, J.D.; Sánchez, B.A.H.; Arango, J.L.C.; Tuya, F.A.C.; Díaz-Varela, R. An UAV and Satellite Multispectral Data Approach to Monitor Water Quality in Small Reservoirs. Remote Sens (Basel) 2020, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papa, A. A Versatile Constellation of Microsatellites with Electric Propulsion for Earth Observation: Mission Analysis and Platform Design. jouranal of sustaianeble regional initiative 2021, 3, 4–13. [Google Scholar]

- Mouta, N.; Silva, R.; Pinto, E.M.; Vaz, A.S.; Alonso, J.M.; Gonçalves, J.F.; Honrado, J.; Vicente, J.R. Sentinel-2 Time Series and Classifier Fusion to Map an Aquatic Invasive Plant Species along a River—The Case of Water-Hyacinth. Remote Sens (Basel) 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pádua, L.; Antão-Geraldes, A.M.; Sousa, J.J.; Rodrigues, M.Â.; Oliveira, V.; Santos, D.; Miguens, M.F.P.; Castro, J.P. Water Hyacinth (Eichhornia Crassipes) Detection Using Coarse and High-Resolution Multispectral Data. Drones 2022, 6, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, T.; Zhang, D.; Li, X.; Huang, Y.; Zhang, L.; Zhu, Z.; Sun, X.; Lan, Z.; Guo, W. Hyperspectral Remote Sensing Technology for Water Quality Monitoring: Knowledge Graph Analysis and Frontier Trend. Front Environ Sci 2023, 11, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jinxiang, Shen; He, P.; Sun, X.; Shen, Z.; Xu, R. Impact Eichhornia Crassipes Cultivation on Water Quality in the Caohai Region of Dianchi Lake Using Multi-Temporal. Remote Sens (Basel) 2023, i.

- Sunder, S.; Ramsankaran, R.; Ramakrishnan, B. Inter-Comparison of Remote Sensing Sensing-Based Shoreline Mapping Techniques at Different Coastal Stretches of India. Environ Monit Assess 2017, 189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghoussein, Y.; Nicolas, H.; Haury, J.; Fadel, A.; Pichelin, P.; Hamdan, H.A.; Faour, G. Multitemporal Remote Sensing Based on an FVC Reference Period Using Sentinel-2 for Monitoring Eichhornia Crassipes on a Mediterranean River. Remote Sens (Basel) 2019, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ade, C.; Khanna, S.; Lay, M.; Ustin, S.L.; Hestir, E.L. Genus-Level Mapping of Invasive Floating Aquatic Vegetation Using Sentinel-2 Satellite Remote Sensing. Remote Sens (Basel) 2022, 14, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pádua, L.; Duarte, L.; Antão-Geraldes, A.M.; Sousa, J.J.; Castro, J.P. Spatio-Temporal Water Hyacinth Monitoring in the Lower Mondego (Portugal) Using Remote Sensing Data. Plants 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nassar, M.; Salah, K.; ur Rehman, M.H.; Svetinovic, D. Blockchain for Explainable and Trustworthy Artificial Intelligence. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Data Min Knowl Discov 2020, 10, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrera Ollachica, D.A.; Asiedu Asante, B.K.; Imamura, H. Advancing Water Hyacinth Recognition: Integration of Deep Learning and Multispectral Imaging for Precise Identification. Remote Sens (Basel) 2025, 17, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Li, X.; Gao, T. The Multifaceted Function of Water Hyacinth in Maintaining Environmental Sustainability and the Underlying Mechanisms: A Mini Review. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2022, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Chen, J.; Yue, Y.; Lan, Y.; Ling, M.; Li, X.; You, H.; Han, X.; Zhou, G. Tradeoffs among Multi-Source Remote Sensing Images, Spatial Resolution, and Accuracy for the Classification of Wetland Plant Species and Surface Objects Based on the MRS_DeepLabV3+ Model. Ecol Inform 2024, 81, 102594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chawira, M.; Dube, T.; Gumindoga, W. Remote Sensing Based Water Quality Monitoring in Chivero and Manyame Lakes of Zimbabwe. Physics and Chemistry of the Earth 2013, 66, 38–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajora, K.; Tyagi, S.; Jena, R. Evaluation of Water Hyacinth Utility through Geospatial Mapping and in Situ Biomass Estimation Approach: A Case Study of Deepor Beel (Wetland), Assam, India. Environ Monit Assess 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toming, K.; Kutser, T.; Laas, A.; Sepp, M.; Paavel, B.; Nõges, T. First Experiences in Mapping Lakewater Quality Parameters with Sentinel-2 MSI Imagery. Remote Sens (Basel) 2016, 8, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elhag, M.; Gitas, I.; Othman, A.; Bahrawi, J.; Gikas, P. Assessment of Water Quality Parameters Using Temporal Remote Sensing Spectral Reflectance in Arid Environments, Saudi Arabia. Water (Switzerland) 2019, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kupssinskü, L.S.; Guimarães, T.T.; De Souza, E.M.; Zanotta, D.C.; Veronez, M.R.; Gonzaga, L.; Mauad, F.F. A Method for Chlorophyll-a and Suspended Solids Prediction through Remote Sensing and Machine Learning. Sensors (Switzerland) 2020, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anand, V.; Oinam, B.; Wieprecht, S. Machine Learning Approach for Water Quality Predictions Based on Multispectral Satellite Imageries. Ecol Inform 2024, 84, 102868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leggesse, E.S.; Zimale, F.A.; Sultan, D.; Enku, T.; Srinivasan, R.; Tilahun, S.A. Predicting Optical Water Quality Indicators from Remote Sensing Using Machine Learning Algorithms in Tropical Highlands of Ethiopia. Hydrology 2023, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trisakti, B.; Suwargana, N.; Cahyono, J.S. Monitoring of Lake Ecosystem Parameter Using Landsat Data (a Case Study: Lake Rawa Pening). International Journal of Remote Sensing and Earth Sciences (IJReSES) 2017, 12, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, B.; Lao, Z.; Liang, Y.; Sun, J.; He, X.; Deng, T.; He, W.; Fan, D.; Gao, E.; Hou, Q. Evaluating Optically and Non-Optically Active Water Quality and Its Response Relationship to Hydrometeorology Using Multi-Source Data in Poyang. 2022, 145. [CrossRef]

- Adjovu, G.; Stephen, H.; James, D.; Ahmad, S. Measurement of Total Dissolved Solids and Total Suspended Solids in Water Systems. Remote Sens (Basel) 2023, 15, 1–43. [Google Scholar]

- Gholizadeh, M.H.; Melesse, A.M. Study on Spatiotemporal Variability of Water Quality Parameters in Florida Bay Using Remote Sensing. Journal of Remote Sensing & GIS 2017, 06. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Yang, W. Water Quality Monitoring and Evaluation Using Remote-Sensing Techniques in China: A Systematic Review. Ecosystem Health and Sustainability 2019, 5, 47–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirmazloumi, S.M.; Moghimi, A.; Ranjgar, B.; Mohseni, F.; Ghorbanian, A.; Ahmadi, S.A.; Amani, M.; Brisco, B. Status and Trends of Wetland Studies in Canada Using Remote Sensing Technology with a Focus on Wetland Classification: A Bibliographic Analysis. Remote Sens (Basel) 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Wang, S.; Zou, D.; Chen, H.; Zhong, R.; Li, H.; Zhou, W.; Yan, K. Social Network and Bibliometric Analysis of Unmanned Aerial Vehicle Remote Sensing Applications from 2010 to 2021. Remote Sens (Basel) 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Du, Y.; Zhao, H.; Chen, F. Water Quality Chl-a Inversion Based on Spatio-Temporal Fusion and Convolutional Neural Network. Remote Sens (Basel) 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilonzo, F.; Masese, F.O.; Van Griensven, A.; Bauwens, W.; Obando, J.; Lens, P.N.L. Spatial-Temporal Variability in Water Quality and Macro-Invertebrate Assemblages in the Upper Mara River Basin, Kenya. Physics and Chemistry of the Earth 2014, 67–69, 93–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Guo, W.; Ngo, H.H.; Nghiem, L.D.; Hai, F.I.; Zhang, J.; Liang, S.; Wang, X.C. A Review on the Occurrence of Micropollutants in the Aquatic Environment and Their Fate and Removal during Wastewater Treatment. Science of the Total Environment 2014, 473–474, 619–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latwal, A.; Rehana, S.; Rajan, K.S. Detection and Mapping of Water and Chlorophyll-a Spread Using Sentinel-2 Satellite Imagery for Water Quality Assessment of Inland Water Bodies. Environ Monit Assess 2023, 195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verpoorter, C.; Kutser, T.; Seekell, D.A.; Tranvik, L.J. A Global Inventory of Lakes Based on High-Resolution Satellite Imagery. Geophys Res Lett 2014, 41, 6396–6402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmer, M.A.; Reidy Liermann, C.A.; Nilsson, C.; Flörke, M.; Alcamo, J.; Lake, P.S.; Bond, N. Climate Change and the World’s River Basins: Anticipating Management Options. Front Ecol Environ 2008, 6, 81–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukarugwiro, J.A.; Newete, S.W.; Abutaleb, E.A.F.N.K.; Byrne, M.J. Mapping Spatio - Temporal Variations in Water Hyacinth (Eichhornia Crassipes) Coverage on Rwandan Water Bodies Using Multispectral Imageries. International Journal of Environmental Science and Technology 2021, 18, 275–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sachan, A.; Pradhan, A.K.; Mohindra, V.; Menegaki, A. A Bibliometric Analysis of Key Drivers, Trends, and Research Collaboration on Environmental Degradation. Discover Sustainability 2025, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalky, A.; Altawalbih, M.; Alshanik, F.; Khasawneh, R.A.; Tawalbeh, R.; Al-Dekah, A.M.; Alrawashdeh, A.; Quran, T.O.; ALBashtawy, M. Global Research Trends, Hotspots, Impacts, and Emergence of Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning in Health and Medicine: A 25-Year Bibliometric Analysis. Healthcare (Switzerland) 2025, 13, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drusch, M.; Del Bello, U.; Carlier, S.; Colin, O.; Fernandez, V.; Gascon, F.; Hoersch, B.; Isola, C.; Laberinti, P.; Martimort, P.; et al. Sentinel-2: ESA’s Optical High-Resolution Mission for GMES Operational Services. Remote Sens Environ 2012, 120, 25–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pahlevan, N.; Sarkar, S.; Franz, B.A.; Balasubramanian, S. V.; He, J. Sentinel-2 MultiSpectral Instrument (MSI) Data Processing for Aquatic Science Applications: Demonstrations and Validations. Remote Sens Environ 2017, 201, 47–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pekel, J.F.; Cottam, A.; Gorelick, N.; Belward, A.S. High-Resolution Mapping of Global Surface Water and Its Long-Term Changes. Nature 2016, 540, 418–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wulder, M.A.; Loveland, T.R.; Roy, D.P.; Crawford, C.J.; Masek, J.G.; Woodcock, C.E.; Allen, R.G.; Anderson, M.C.; Belward, A.S.; Cohen, W.B.; et al. Current Status of Landsat Program, Science, and Applications. Remote Sens Environ 2019, 225, 127–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lian, Z.; Zhan, Y.; Zhang, W.; Wang, Z.; Liu, W.; Huang, X. Recent Advances in Deep Learning-Based Spatiotemporal Fusion Methods for Remote Sensing Images. Sensors 2025, 25, 1–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, S.; Zhu, X.; Deng, H.; Lei, Z.; Deng, L.-J. FusionMamba: Efficient Image Fusion with State Space Model. 2024, 1–15. [CrossRef]

- Ying, H.; Xia, K.; Huang, X.; Feng, H.; Yang, Y.; Du, X.; Huang, L. Evaluation of Water Quality Based on UAV Images and the IMP-MPP Algorithm. Ecol Inform 2021, 61, 101239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, F.; Zhang, W.; Yuan, T.; Ji, Z.; Cao, Z.; Xu, B.; Lu, L.; Zou, S. UAV Quantitative Remote Sensing of Riparian Zone Vegetation for River and Lake Health Assessment: A Review. Remote Sens (Basel) 2024, 16, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]