Submitted:

23 July 2025

Posted:

25 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Mathematical Model

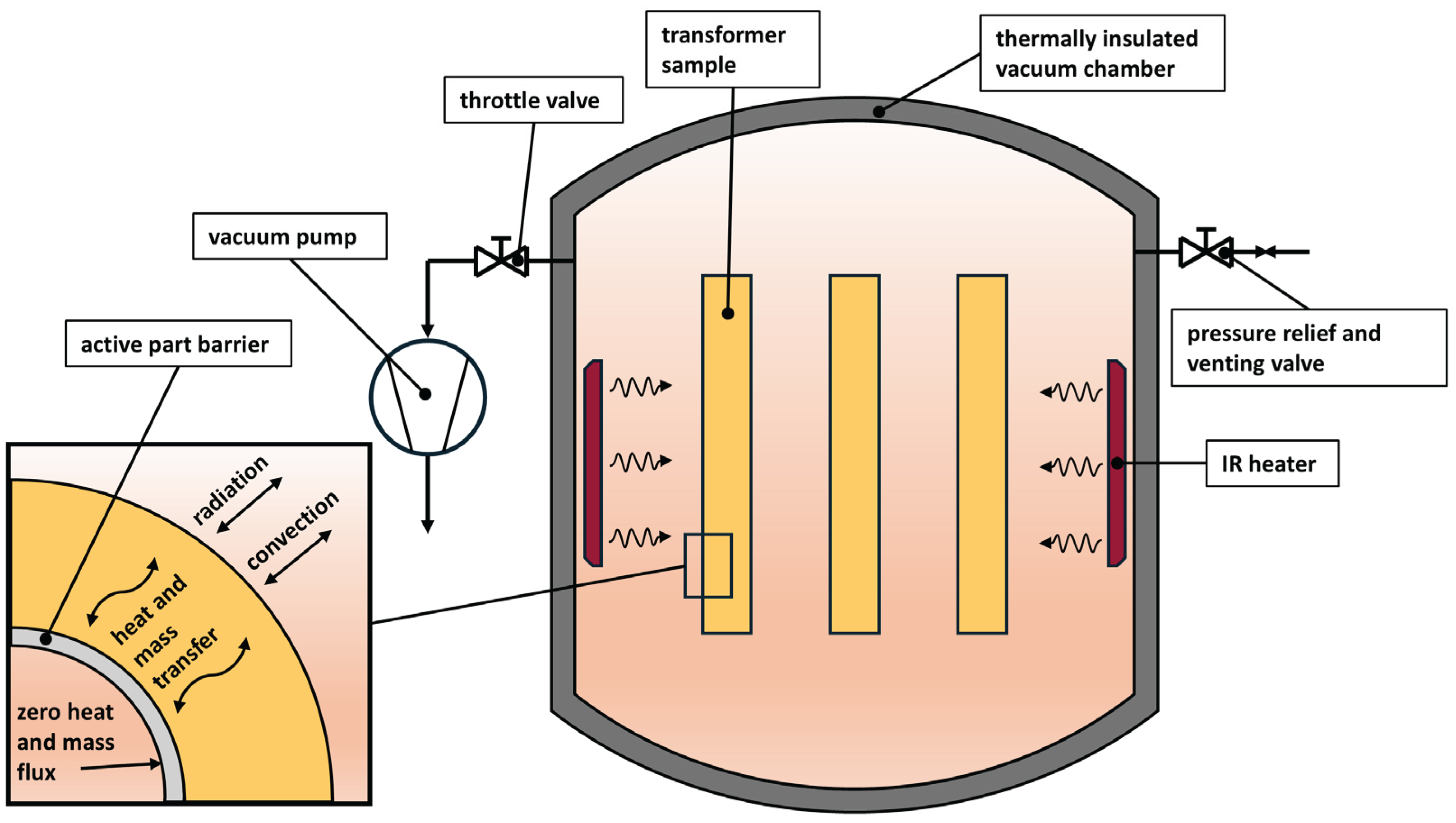

2.1. Drying System Description

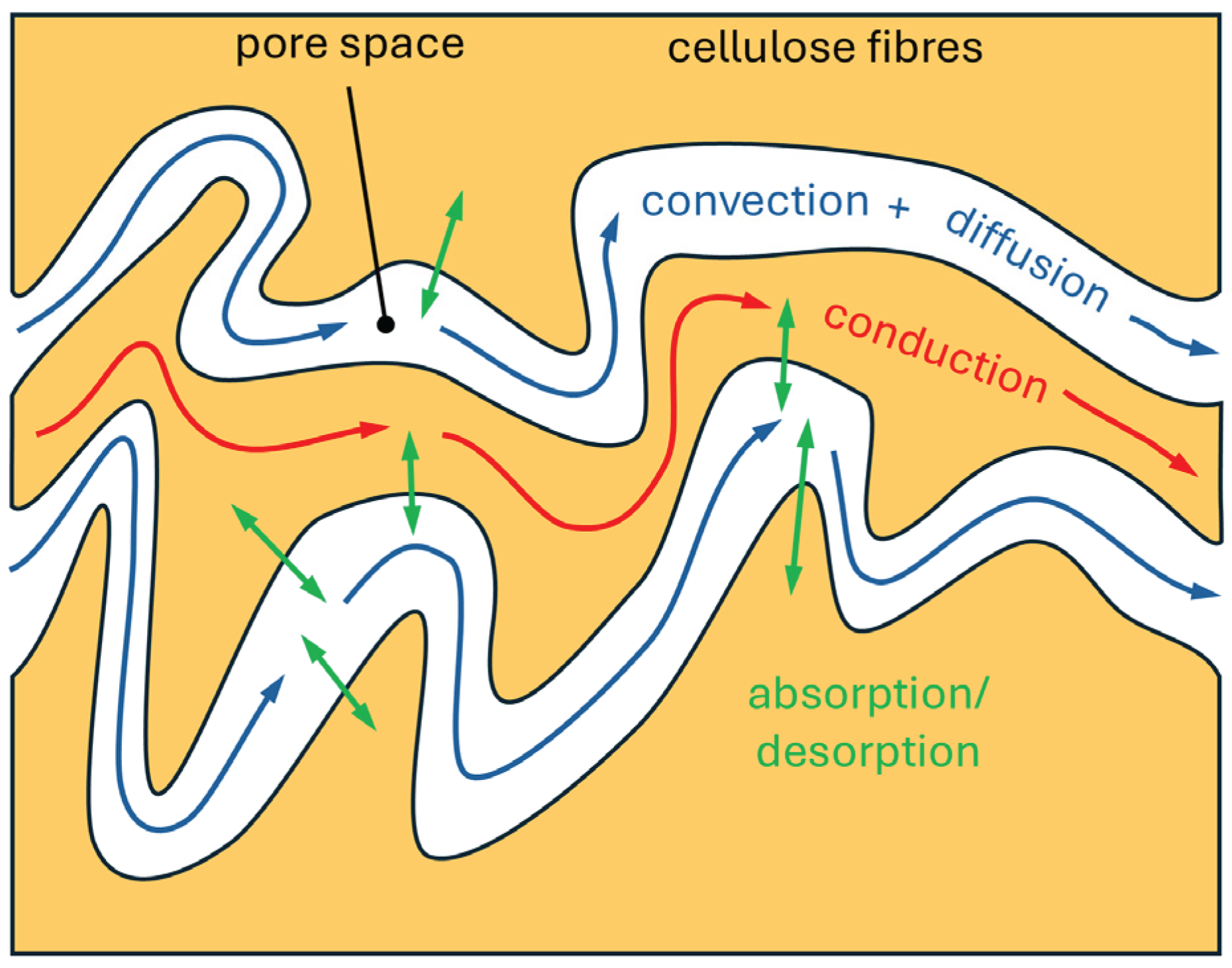

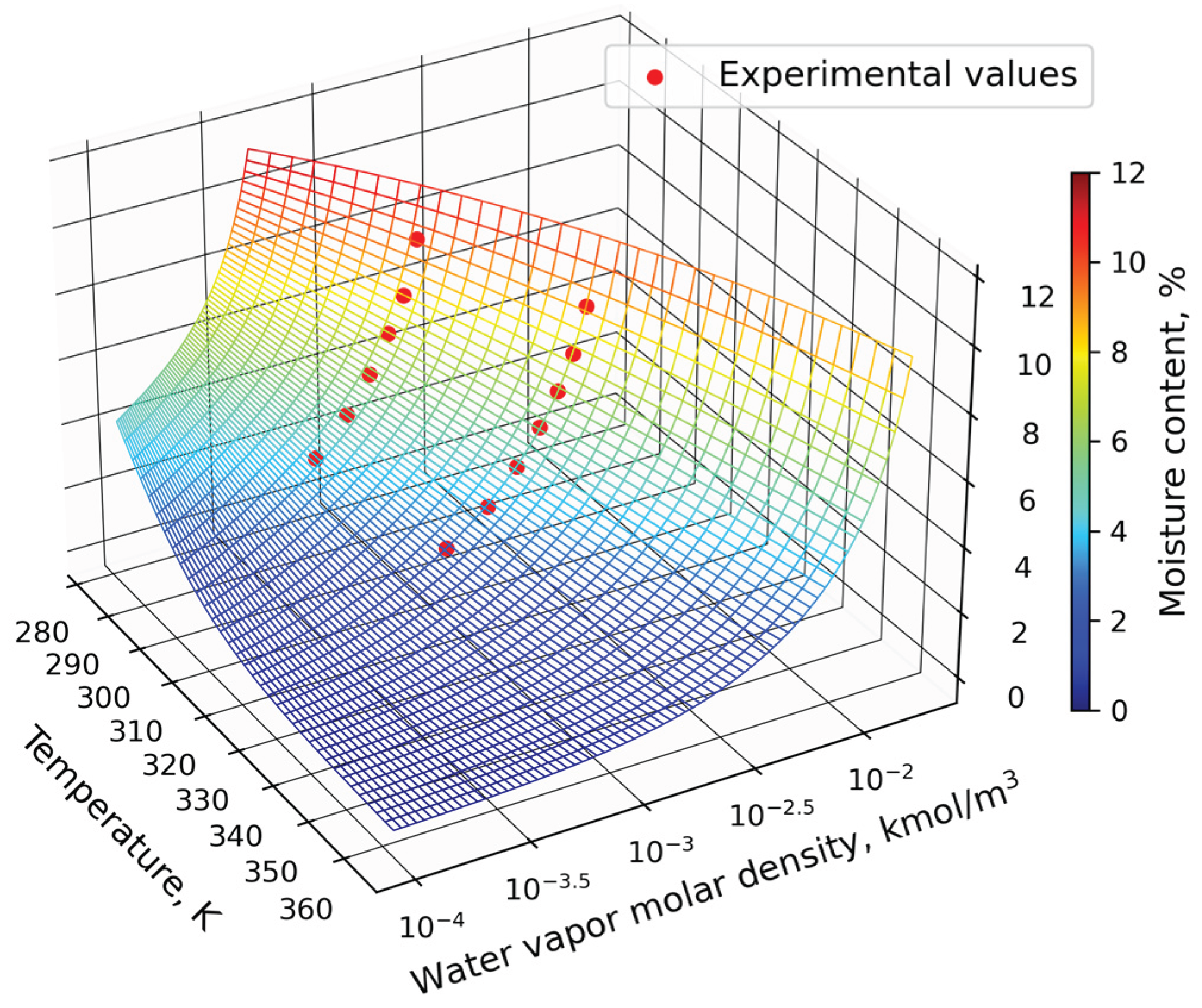

2.2. Governing Equations at the Scale of the Cellulose Insulation

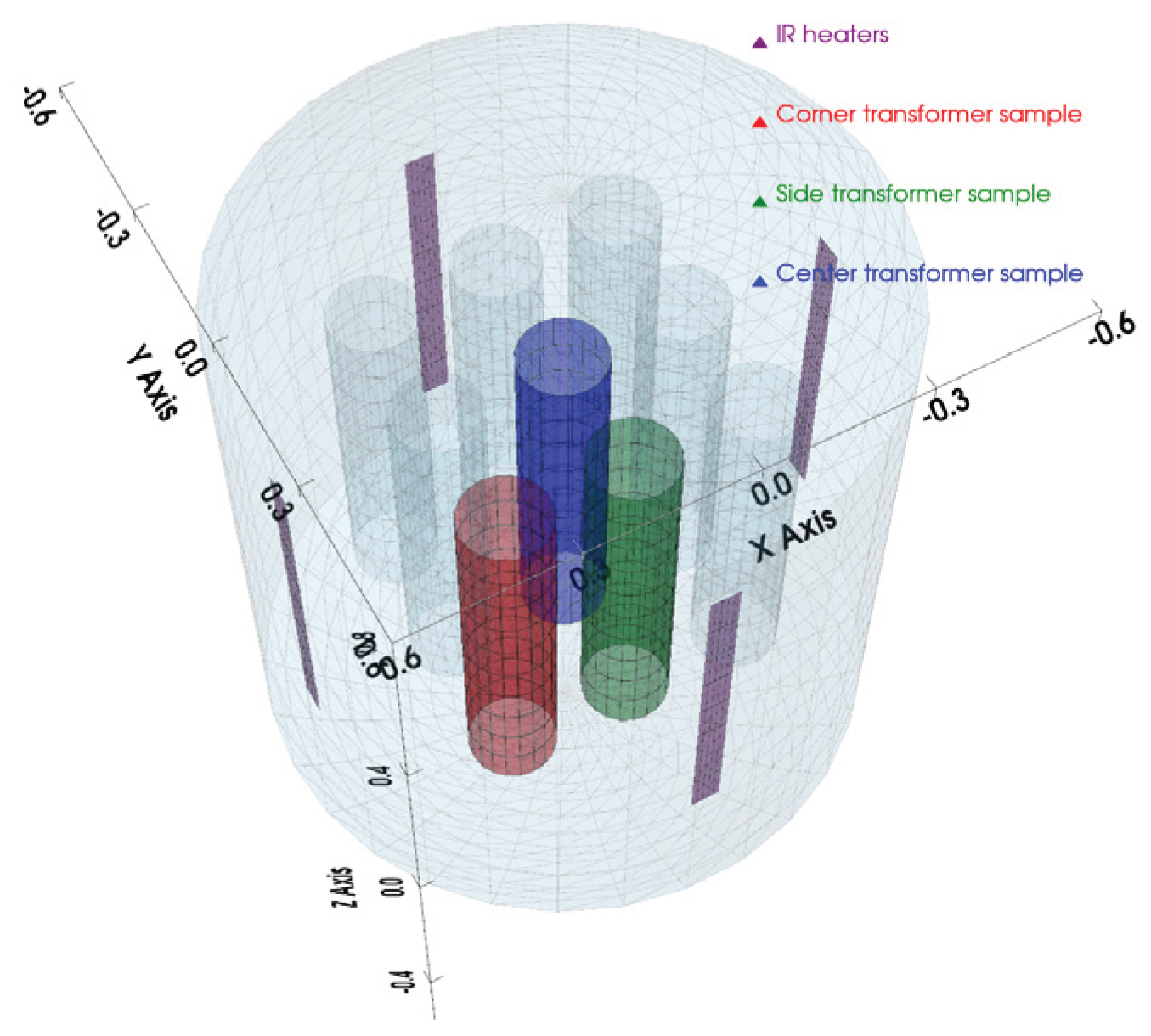

2.3. Governing Equations at the Scale of the Vacuum Chamber

2.3.1. Convective Heat Transfer Coefficients Calculation

2.3.2. Radiative Heat Flow Rates Calculation

2.4. The Interface Between Transformer Cellulose Insulation and Vacuum Chamber Atmosphere

2.5 Initial Conditions

2.5 Numerical Solution Procedure

3. Results and Discussion

- IR heaters (when off, W)

- Vacuum pump (when off, m3/s)

- Venting/pressure relief valve (when off, )

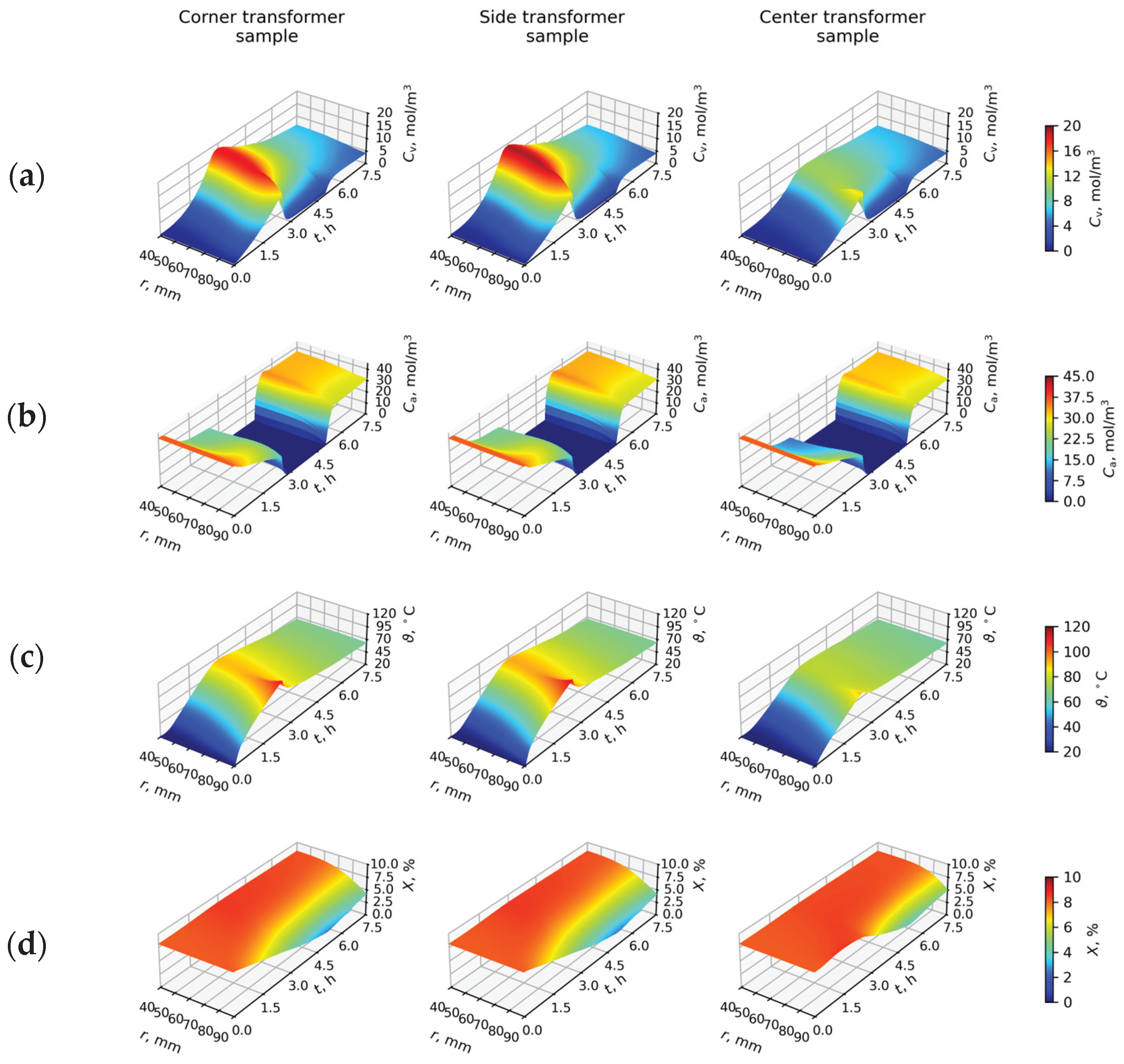

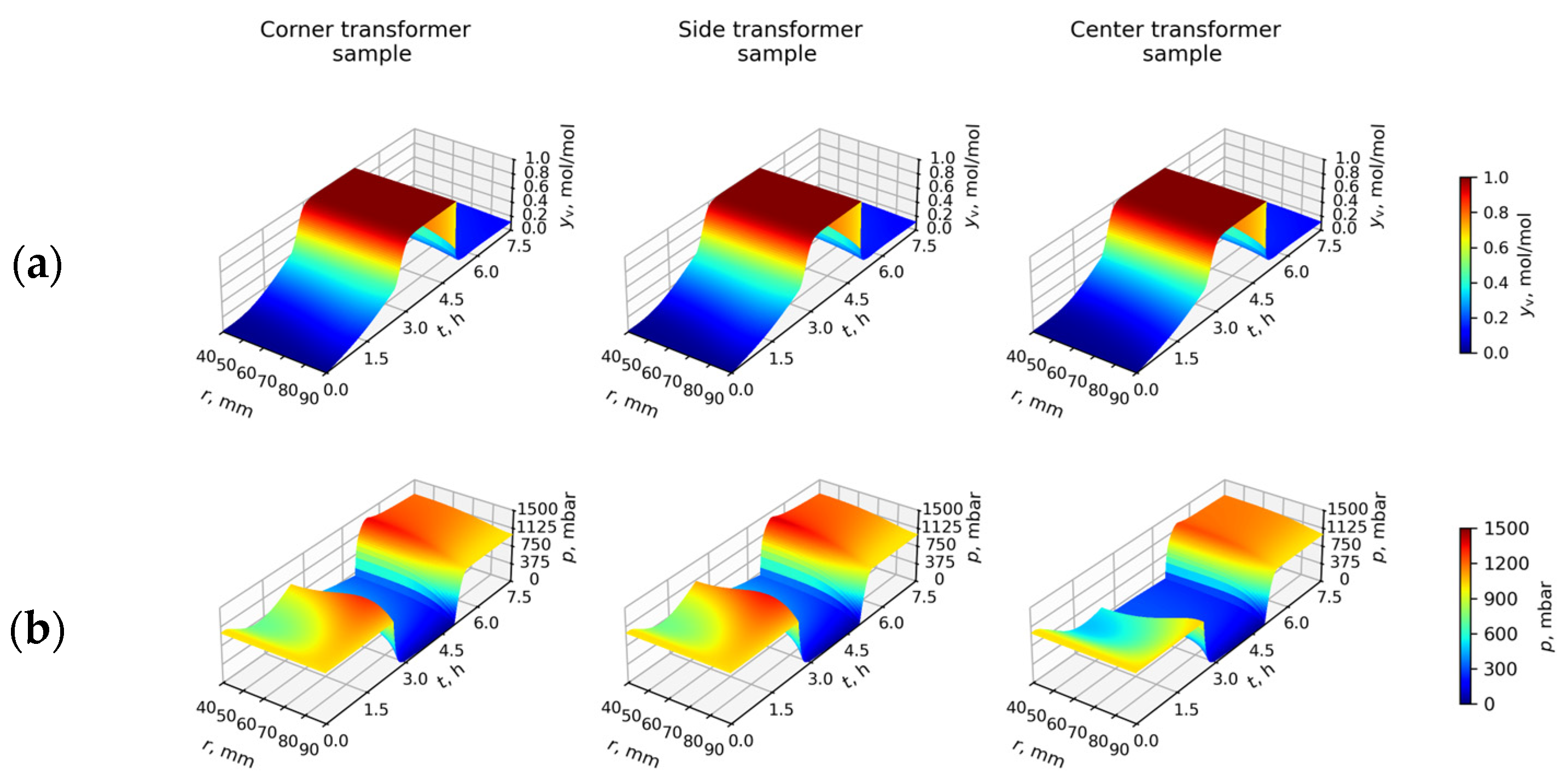

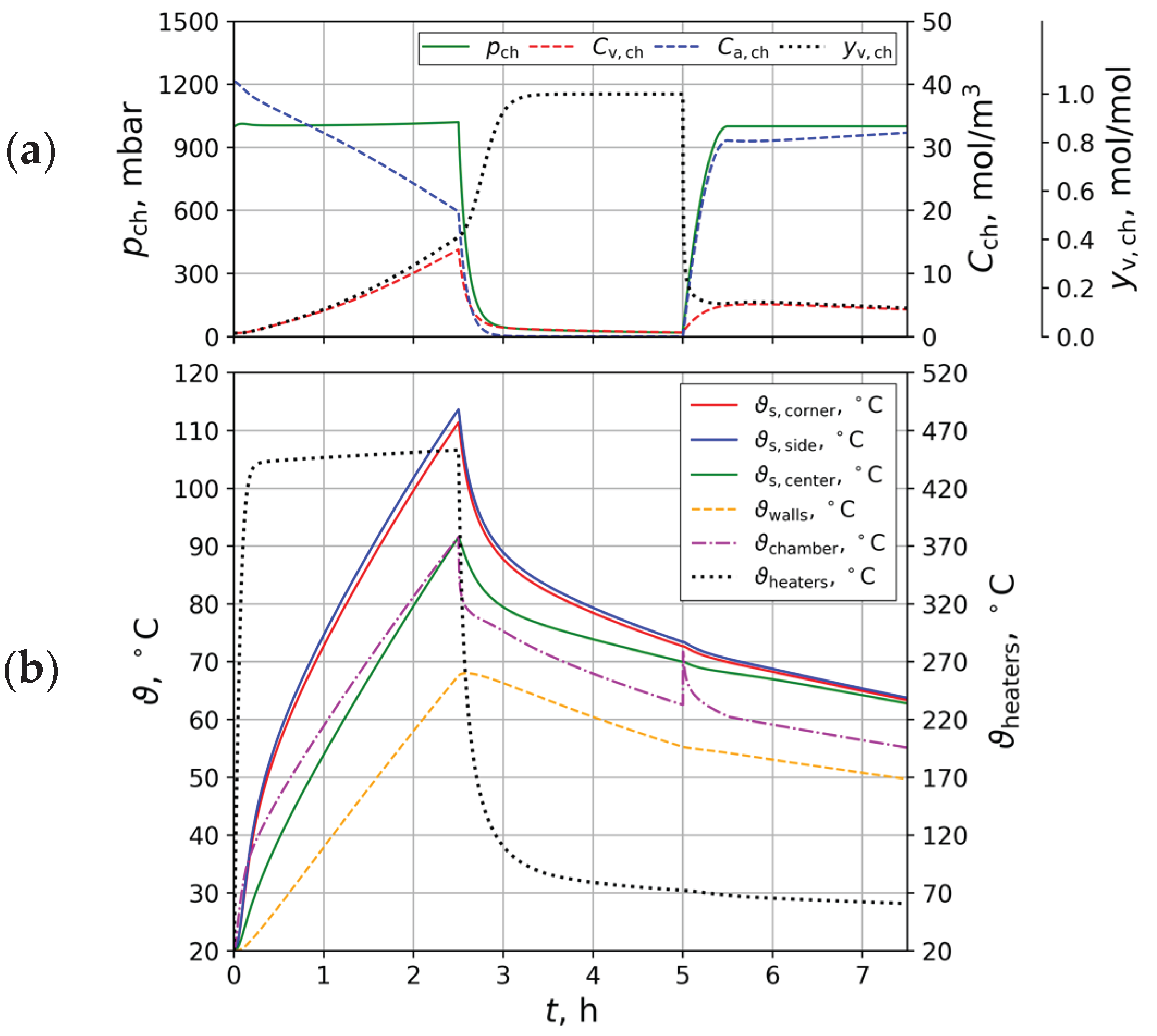

3.1. Test Case Results

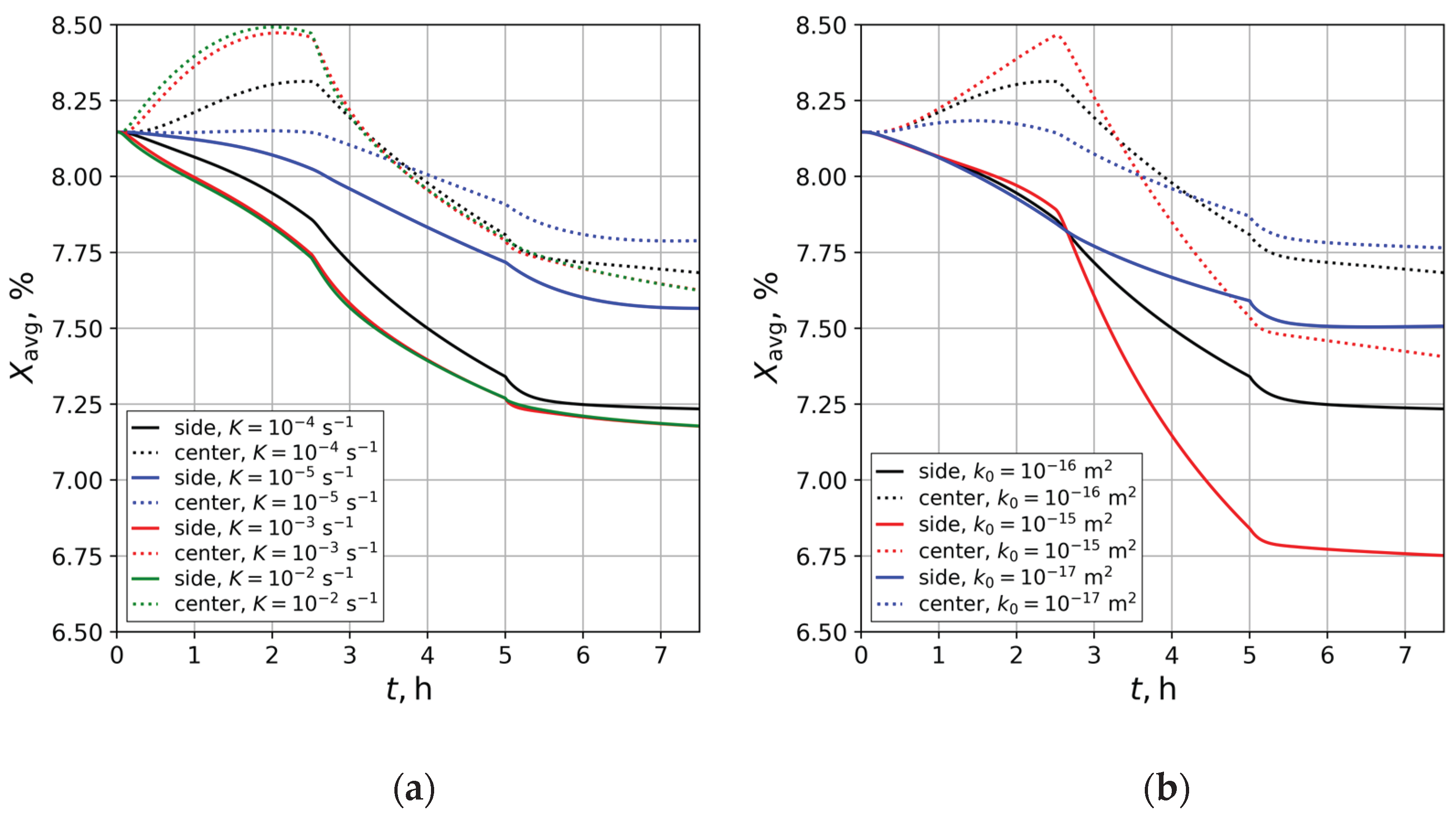

3.2. Impact of the and Parameters

3.3. Drying Case Results

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| GAB | Guggenheim, Anderson and de Boer |

| IR | Infra-red |

| PDE | Partial differential equations |

| ODE | Ordinary differential equations |

| 0D | Zero-dimensional |

| CFD | Computational fluid dynamics |

Nomenclature

| Latin symbols | |

| IR heaters surface area, m2 | |

| Transformer cellulose insulation outer surface area, m2 | |

| water activity, - | |

| vacuum chamber walls surface area, m2 | |

| Klinkenberg parameter, Pa | |

| dry air molar density of the vacuum chamber atmosphere, kmol/m3 | |

| molar density of the vacuum chamber atmosphere, kmol/m3 | |

| water vapor molar density of the vacuum chamber atmosphere, kmol/m3 | |

| dry air molar density, kmol/m3 | |

| gaseous phase molar density, kmol/m3 | |

| water vapor molar density, kmol/m3 | |

| effective binary diffusivity (water vapor and dry air), m2/s | |

| equivalent binary diffusivity (water vapor and dry air), m2/s | |

| Knudsen diffusivity parameter, m2/s | |

| i-th transformer convective heat transfer coefficient, W/(m2∙K) | |

| vacuum chamber walls convective heat transfer coefficient, W/(m2∙K) | |

| IR heaters convective heat transfer coefficient, W/(m2∙K) | |

| i-th transformer outer surface molar flux of dry air, kmol/(m2∙s) | |

| i-th transformer outer surface molar flux of water vapor, kmol/(m2∙s) | |

| internal mass transfer parameter, 1/s | |

| absolute permeability of the cellulose insulation, m2 | |

| effective permeability of the cellulose insulation, m2 | |

| Venting/pressure relief valve flow coefficient, m3/s | |

| pressure of the gaseous phase, Pa | |

| dry air partial pressure in the vacuum chamber atmosphere, Pa | |

| water vapor partial pressure in the vacuum chamber atmosphere, Pa | |

| pressure of the vacuum chamber atmosphere, Pa | |

| pressure at the inlet of the vacuum pump, Pa | |

| convective heat flow rate to vacuum chamber atmosphere, W | |

| radiative heat flow rate from IR heaters surface, W | |

| radiative heat flow rate from the surface of the i-th transformer, W | |

| IR heaters input electrical power, W | |

| radiative heat flow from the surface of vacuum chamber walls, W | |

| vacuum pump inlet pumping speed, m3/s | |

| vacuum pump effective pumping speed, m3/s | |

| volume flow rate through pressure relief valve, m3/s | |

| volume flow rate through venting valve, m3/s | |

| radius of the cellulose insulation, m | |

| universal gas constant, 8314.4 J/(kmol∙K) | |

| time variable, s | |

| cellulose insulation temperature, K | |

| i-th transformer cellulose insulation outer surface temperature, K | |

| ambient temperature, K | |

| vacuum chamber atmosphere temperature, K | |

| IR heaters temperature, K | |

| vacuum chamber walls temperature, K | |

| vacuum chamber atmosphere volume, m3 | |

| Darcy’s velocity of gaseous phase, m/s | |

| dry-basis moisture content of the cellulose fibres, kg/kg | |

| dry-basis average moisture content of the cellulose fibres, kg/kg | |

| dry-basis equilibrium moisture content of the cellulose fibres, kg/kg | |

| Greek symbols | |

| dry air specific heat ratio, - | |

| gaseous phase specific heat ratio, - | |

| water vapor specific heat ratio, - | |

| vacuum chamber thermal insulation thickness, m | |

| fibre volume fraction, - | |

| porosity of the cellulose insulation, - | |

| cellulose insulation effective thermal conductivity, W/(m∙K) | |

| cellulose fibre thermal conductivity, W/(m∙K) | |

| vacuum chamber thermal insulation thermal conductivity, W/(m∙K) | |

| cellulose insulation bulk density, kg/m3 | |

| cellulose fibres density, kg/m3 | |

| cellulose fibre tortuosity, - | |

| pore space tortuosity, - | |

| Stefan-Boltzmann constant, 5.67∙10-8 W/(m2∙K4) | |

| gaseous phase dynamic viscosity, Pa∙s |

Appendix

| Parameter | Value/relation | Unit |

|---|---|---|

| Fibre density, | 1550 [37] | kg/m3 |

| Bulk density, | 1000 | kg/m3 |

| Fibre specific heat capacity, | 1340 [37] | J/(kg∙K) |

| Fibre thermal conductivity, | 0.335 [37] | W/(m∙K) |

| Porosity, | - | |

| Fibre volume fraction, | - | |

| Pore tortuosity, | [38] | - |

| Fibre tortuosity, | [38] | - |

| Klinkenberg parameter, | [39] | Pa |

| Knudsen diffusivity parameter, | 10-5 | m2/s |

| Emissivity, | 0.9 | - |

| GAB isotherm parameter, | 0.05128 [23] | kg/kg |

| GAB isotherm parameter, | 0.716 [23] | - |

| GAB isotherm parameter, | 6.1446 [23] | - |

| GAB isotherm parameter, | 323.15 [23] | K |

| GAB isotherm parameter, | 19319.76 [23] | kJ/kmol |

| Parameter | Value/relation | Unit |

|---|---|---|

| Vacuum chamber walls specific heat capacity, | 461 (stainless steel) | J/(kg∙K) |

| Vacuum chamber walls emissivity, | 0.1 | - |

| Vacuum chamber walls thermal insulation conductivity, | W/(m∙K) | |

| IR heaters specific heat capacity, | 800 (ceramics) | J/(kg∙K) |

| IR heaters emissivity, | 0.95 | - |

| Parameter | Value/relation | Unit |

|---|---|---|

| Transformer inner radius, | 40 | mm |

| Transformer cellulose insulation thickness, | 50 | mm |

| Transformer outer radius, | mm | |

| Transformer height, | 0.8 | m |

| Transformer surface area, | m2 | |

| Number of transformers in the vacuum chamber, | 9 | - |

| Spacing between transformers | 0.08 | m |

| Vacuum chamber walls mass, | 370.389 | kg |

| Vacuum chamber atmosphere volume, | 1.7567 | m2 |

| Vacuum chamber walls surface area, | 7.86388 | m2 |

| Vacuum chamber shell height, | 1.21 | m |

| Vacuum chamber thermal insulation thickness, | 32 | mm |

| IR heater width, | 62.5 | mm |

| IR heater height, | 0.75 | m |

| IR heaters number, | 4 | - |

| IR heaters total mass, | 2.7 | kg |

| IR heaters total electrical power, | 3000 | W |

| Vacuum pump nominal pumping speed | 65 (Leybold VD65) | m3/h |

| Vacuum pump inlet pumping speed, | linearly interpolated from the data for Leybold VD65 (gas ballast valve closed) | m3/s |

| Suction line conductance, | 0.01 | m3/s |

| Venting/pressure relief valve flow coefficient, | 0.00005 | - |

| Parameter | Value/relation | Unit |

|---|---|---|

| Dry air molar mass, | 28.96 | kg/kmol |

| Water vapor molar mass, | 18 | kg/kmol |

| Gaseous phase molar mass, | kg/kmol | |

| Universal gas constant, | 8314.4 | J/(kmol∙K) |

| Stefan-Boltzmann constant, | 5.6703∙10-8 | W/(m2∙K4) |

| Water specific evaporation heat, | 2.5∙106 | J/kg |

| Dry air constant pressure specific heat capacity*, | [40] | J/(kg∙K) |

| Water vapor constant pressure specific heat capacity*, | [40] | J/(kg∙K) |

| Gaseous phase constant pressure specific heat capacity*, | J/(kg∙K) | |

| Dry air constant pressure molar heat capacity, | J/(kmol∙K) | |

| Water vapor constant pressure molar heat capacity, | J/(kmol∙K) | |

| Gaseous phase constant pressure molar heat capacity, | J/(kmol∙K) | |

| Water vapor dynamic viscosity, | [40] | Pa∙s |

| Dry air dynamic viscosity, | [40] | Pa∙s |

| Gaseous phase dynamic viscosity, | Pa∙s | |

| Water vapor saturation pressure, | calculated for given temperature according to IAPWS 95 [26] | Pa |

| Gaseous phase density*, | kg/m3 | |

| Water vapor thermal conductivity*, | [40] | W/(m∙K) |

| Dry air thermal conductivity*, | [40] | W/(m∙K) |

| Water vapor thermal conductivity*, | W/(m∙K) |

References

- Liang, Z.; Fang, Y.; Cheng, H.; Sun, Y.; Li, B.; Li, K.; Zhao, W.; Sun, Z.; Zhang, Y. Innovative Transformer Life Assessment Considering Moisture and Oil Circulation. Energies (Basel) 2024, 17. [CrossRef]

- Tazhibayev, A.; Amitov, Y.; Arynov, N.; Shingissov, N.; Kural, A. Experimental Investigation and Evaluation of Drying Methods for Solid Insulation in Transformers: A Comparative Analysis. Results in Engineering 2024, 23. [CrossRef]

- Brahami, Y.; Betie, A.; Meghnefi, F.; Fofana, I.; Yeo, Z. Development of a Comprehensive Model for Drying Optimization and Moisture Management in Power Transformer Manufacturing. Energies (Basel) 2025, 18. [CrossRef]

- Du, Y. Measurement and Modeling of Moisture Diffusion Processes in Transformer Insulation Using Interdigital Dielectrometry Sensors. Ph.D. Thesis, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 1999.

- García, D.F.; García, B.; Burgos, J.C.; García-Hernando, N. Determination of Moisture Diffusion Coefficient in Transformer Paper Using Thermogravimetric Analysis. Int J Heat Mass Transf 2012, 55, 1066–1075. [CrossRef]

- Villarroel, R.; Garcia, D.; Garcia, B.; Burgos, J. Diffusion Coefficient in Transformer Pressboard Insulation Part 1: Non Impregnated Pressboard. IEEE Transactions on Dielectrics and Electrical Insulation 2014, 21, 360–368. [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Zhou, L.; Wang, L.; Guo, L.; Liao, W. Modified Expression of Moisture Diffusion Factor for Non-Oil-Immersed Insulation Paper. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 41315–41323. [CrossRef]

- Krabbenhoft, K.; Damkilde, L. A Model for Non-Fickian Moisture Transfer in Wood. Mater Struct 2004, 37, 615–622. [CrossRef]

- Perre, P. The Proper Use of Mass Diffusion Equation in Drying Modelling: From Simple Configurations to Non-Fickian Behaviours. In Proceedings of the 19th International Drying Symposium (IDS 2014); 2018.

- Perré, P.; Rémond, R.; Almeida, G.; Augusto, P.; Turner, I. State-of-the-Art in the Mechanistic Modeling of the Drying of Solids: A Review of 40 Years of Progress and Perspectives. Drying Technology 2023, 41, 1–26. [CrossRef]

- Garcia, D.F.; Villarroel, R.D.; Garcia, B.; Burgos, J.C. Effect of the Thickness on the Water Mobility Inside Transformer Cellulosic Insulation. IEEE Transactions on Power Delivery 2016, 31, 955–962. [CrossRef]

- Kang, M.; Yang, L.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, K.; He, Y. Diffusion Behavior of Free Water and Bound Water in Insulation Paper Based on Langmuir Model. Cellulose 2024, 31, 3275–3287. [CrossRef]

- Przybylek, P. A New Concept of Applying Methanol to Dry Cellulose Insulation at the Stage of Manufacturing a Transformer. Energies (Basel) 2018, 11. [CrossRef]

- Siddiqui, T.; Pattiwar, J.T.; Paranjape, A.P. Statistical Analysis of the Influence of Various Temperatures on the Drying Time of Transformer Insulation in Vacuum Drying Process. 4th International Conference for Convergence in Technology (I2CT) 2018.

- Perré, P.; Rémond, R.; Colin, J.; Mougel, E.; Almeida, G. Energy Consumption in the Convective Drying of Timber Analyzed by a Multiscale Computational Model. Drying Technology 2012, 30, 1136–1146. [CrossRef]

- Torres, S.S.; Jomaa, W.; Puiggali, J.R.; Avramidis, S. Multiphysics Modeling of Vacuum Drying of Wood. Appl Math Model 2011, 35, 5006–5016. [CrossRef]

- Zadin, V.; Kasemägi, H.; Valdna, V.; Vigonski, S.; Veske, M.; Aabloo, A. Application of Multiphysics and Multiscale Simulations to Optimize Industrial Wood Drying Kilns. Appl Math Comput 2015, 267, 465–475. [CrossRef]

- Jomaa, W.; Baixeras, O. Discontinuous Vacuum Drying of Oak Wood: Modelling and Experimental Investigations. Drying Technology 1997, 15, 2129–2144. [CrossRef]

- Rasetto, V.; Marchisio, D.L.; Fissore, D.; Barresi, A.A. On the Use of a Dual-Scale Model to Improve Understanding of a Pharmaceutical Freeze-Drying Process. J Pharm Sci 2010, 99, 4337–4350. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Gan, H.; Xue, H.; Jiang, Q. Numerical Simulation of an Experimental Study on Structure Optimization for Compartment Dryers. Transactions of FAMENA 2024, 48, 95–110. [CrossRef]

- Lienhard J. H. IV; Lienhard J. H. V A Heat Transfer Textbook; 6th ed.; Phlogiston Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2024.

- Ashrafi Moghadam, A.; Chalaturnyk, R. Expansion of the Klinkenberg’s Slippage Equation to Low Permeability Porous Media. Int J Coal Geol 2014, 123, 2–9. [CrossRef]

- Przybylek, P. Water Saturation Limit of Insulating Liquids and Hygroscopicity of Cellulose in Aspect of Moisture Determination in Oil-Paper Insulation. IEEE Transactions on Dielectrics and Electrical Insulation 2016, 23, 1886–1893. [CrossRef]

- Fessler, W.A.; Rouse, T. 0; Member, S. A Refined Mathematical Model for Prediction of Bubble Evolution in Transformers. IEEE Transactions on Power Delivery 1989, 4, 391–404. [CrossRef]

- Du, Y.; Zahn, M.; Lesieutre, B.C.; Mamishev, A.V.; Lindgren, S.R. Moisture Equilibrium in Transformer Paper-Oil Systems. IEEE Electrical Insulation Magazine 1999, 15, 11–20. [CrossRef]

- Wagner, W.; Pruß, A. The IAPWS Formulation 1995 for the Thermodynamic Properties of Ordinary Water Substance for General and Scientific Use. J Phys Chem Ref Data 2002, 31, 387–535. [CrossRef]

- Staudt, P.B.; Tessaro, I.C.; Marczak, L.D.F.; Soares, R. de P.; Cardozo, N.S.M. A New Method for Predicting Sorption Isotherms at Different Temperatures: Extension to the GAB Model. J Food Eng 2013, 118, 247–255. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J. Thermodynamics and Particle Formation during Vacuum Pump Down. Ph.D. dissertation, Unv. Minnesota: Minneapolis, 1990.

- González-Bárcena, D.; Martínez-Figueira, N.; Fernández-Soler, A.; Torralbo, I.; Bayón, M.; Piqueras, J.; Pérez-Grande, I. Experimental Correlation of Natural Convection in Low Rayleigh Atmospheres for Vertical Plates and Comparison between CFD and Lumped Parameter Analysis. Int J Heat Mass Transf 2024, 222, 125140. [CrossRef]

- Howell, J.R.; Pinar Mengüç, M.; Daun, K.; Siegel, R. Thermal Radiation Heat Transfer; 7th ed.; Taylor & Francis Group, LLC, 2021; ISBN 978-0-367-34707-9.

- Virtanen, P.; Gommers, R.; Oliphant, T.E.; Haberland, M.; Reddy, T.; Cournapeau, D.; Burovski, E.; Peterson, P.; Weckesser, W.; Bright, J.; et al. SciPy 1.0: Fundamental Algorithms for Scientific Computing in Python. Nat Methods 2020, 17, 261–272. [CrossRef]

- Filipov, S.M.; Hristov, J.; Avdzhieva, A.; Faragó, I. A Coupled PDE-ODE Model for Nonlinear Transient Heat Transfer with Convection Heating at the Boundary: Numerical Solution by Implicit Time Discretization and Sequential Decoupling. Axioms 2023, 12. [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, C.; Kaszynski, A. PyVista: 3D Plotting and Mesh Analysis through a Streamlined Interface for the Visualization Toolkit (VTK). J Open Source Softw 2019, 4, 1450. [CrossRef]

- Bogdan, M.; Walther, E.; Alecian, M.; Normale Supérieure Paris-Saclay, É. Calcul Des Facteurs de Forme Entre Polygones-Application à La Thermique Urbaine et Aux Études de Confort; 2022;

- Oksana, M.; Alexander, D. Comparative Analysis of Transformer Solid Insulation Drying Methods. 2022 IEEE Electrical Insulation Conference, EIC 2022 2022, 385–389. [CrossRef]

- Przybylek, P.; Gielniak, J. The Use of Methanol Vapour for Effective Drying of Cellulose Insulation. Energies (Basel) 2023, 16. [CrossRef]

- Nilsson, J.; Stenström, S. Modelling of Heat Transfer in Hot Pressing and Impulse Drying of Paper. Drying Technology 2001, 19, 2469–2485. [CrossRef]

- Foss, W.R.; Bronkhorst, C.A.; Bennett, K.A. Simultaneous Heat and Mass Transport in Paper Sheets during Moisture Sorption from Humid Air. Int J Heat Mass Transf 2003, 46, 2875–2886. [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, R.; Zhu, H.; Li, F.; Yang, D.; Jiao, Y. Radio Frequency Drying Behavior in Porous Media: A Case Study of Potato Cube with Computer Modeling. Foods 2022, 11. [CrossRef]

- Alexandersson, M.; Ristinmaa, M. Coupled Heat, Mass and Momentum Transport in Swelling Cellulose Based Materials with Application to Retorting of Paperboard Packages. Appl Math Model 2021, 92, 848–883. [CrossRef]

| View factor/ surface |

IR heaters | Vacuum chamber walls | Corner transformer sample |

Side transformer sample |

Center transformer sample |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fheaters - i | 0.0000 | 0.4102 | 0.2604 | 0.3295 | 0.0000 |

| Fwalls - i | 0.0098 | 0.7060 | 0.1533 | 0.1125 | 0.0183 |

| Fcorner t - i | 0.0271 | 0.6667 | 0.0000 | 0.2406 | 0.0657 |

| Fside t - i | 0.0343 | 0.4892 | 0.2406 | 0.1313 | 0.1046 |

| Fcenter t - i | 0.0000 | 0.3189 | 0.2626 | 0.4185 | 0.0000 |

| Order | Component status | Duration | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IR heaters | Vacuum pump |

Venting/ pressure relief valve |

||

| 1 | on | off | on | 2.5 h |

| 2 | off | on | off | 2.5 h |

| 3 | off | off | on | 2.5 h |

| Order | Controlled variable |

Component status | Duration1 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IR heaters | Vacuum pump | Venting/ pressure relief valve |

|||

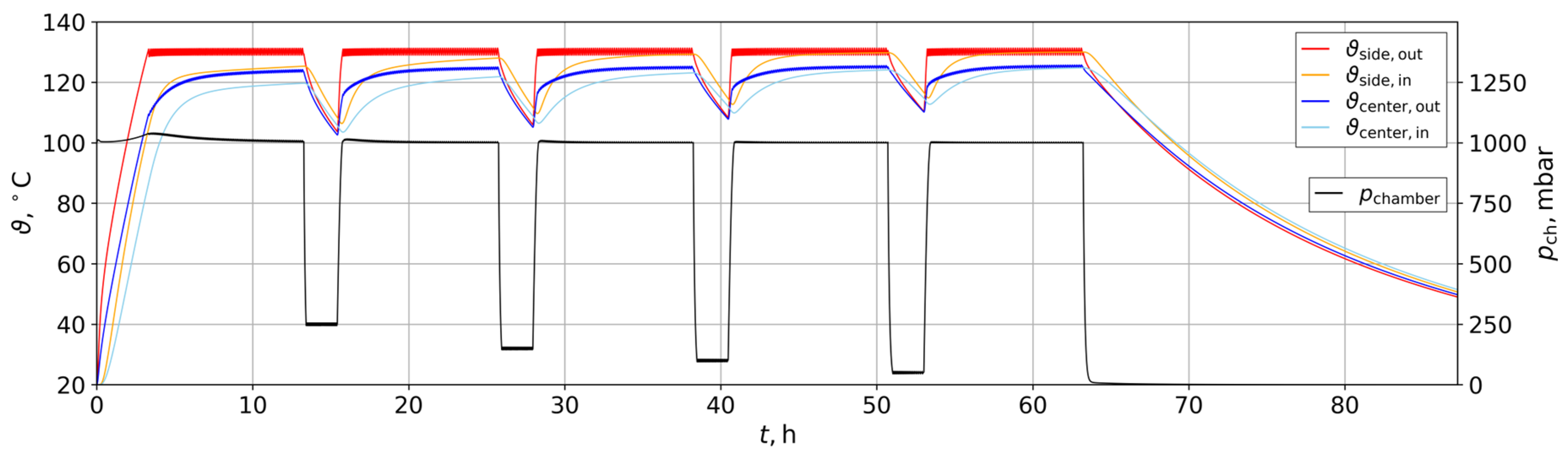

| 1 | 130 ± 1 ⁰C | on/off | off | on | 10 h |

| 2 | 25 ± 0.5 kPa | off | on/off | off | 2 h |

| 3 | 130 ± 1 ⁰C | on/off | off | on | 10 h |

| 4 | 15 ± 0.5 kPa | off | on/off | off | 2 h |

| 5 | 130 ± 1 ⁰C | on/off | off | on | 10 h |

| 6 | 10 ± 0.5 kPa | off | on/off | off | 2 h |

| 7 | 130 ± 1 ⁰C | on/off | off | on | 10 h |

| 8 | 5 ± 0.5 kPa | off | on/off | off | 2 h |

| 9 | 130 ± 1 ⁰C | on/off | off | on | 10 h |

| 10 | min. pressure | off | on | off | 30 h |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).