Submitted:

22 August 2025

Posted:

25 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

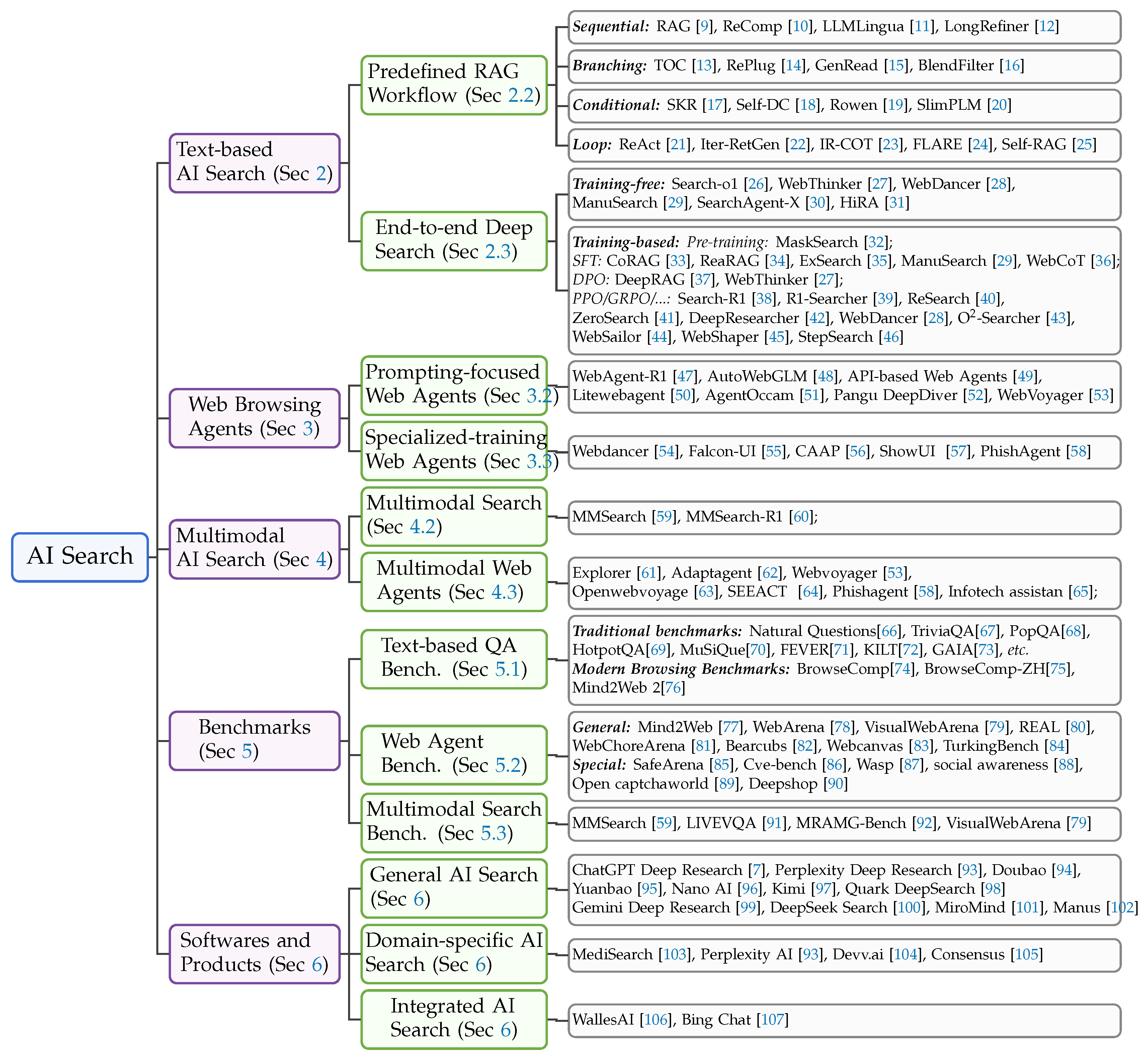

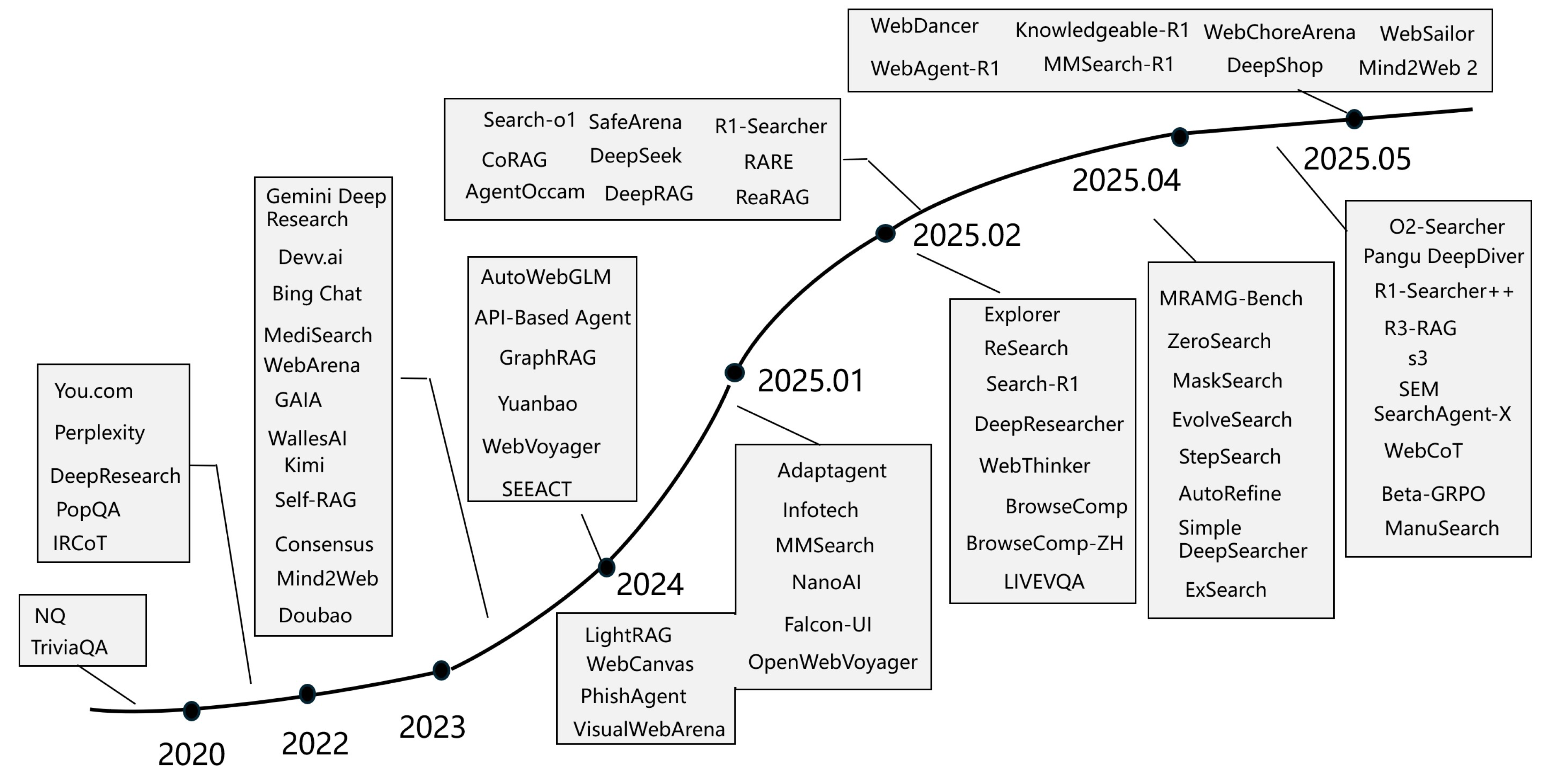

1. Introduction

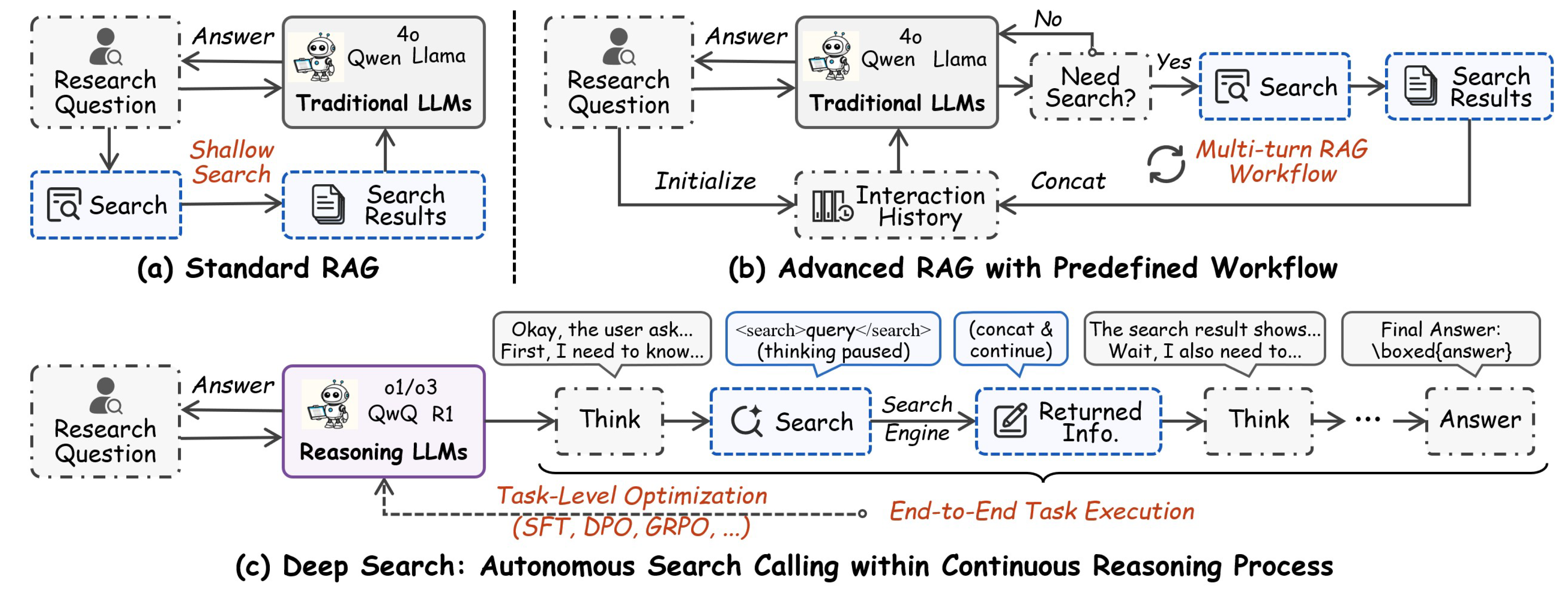

2. Text-Based AI Search

2.1. Traditional Search Engines

Document Retrieval

Post-Ranking

2.2. Retrieval-Augmented Generation with Pre-Defined Workflows

Sequential RAG

Branching RAG

Conditional RAG

Loop RAG

2.3. End-to-End Deep Search Within Reasoning Process

Training-Free Methods

Training-Based Methods

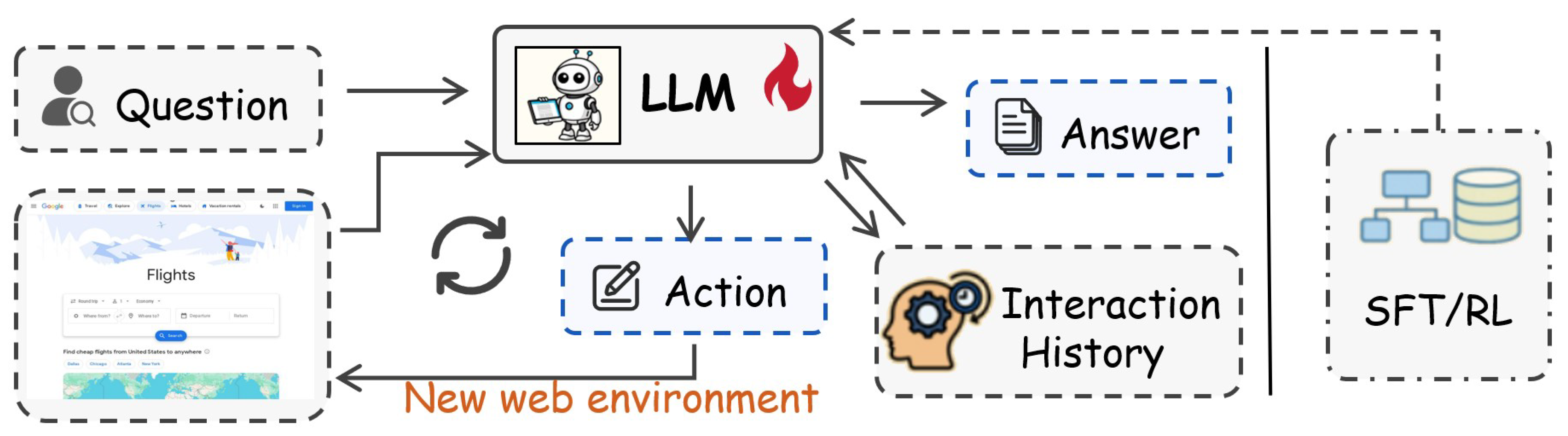

3. Web Browsing Agent

3.1. Agent

3.2. Post-Training-Based Web Agents

Reinforcement Learning

Supervised Fine-Tuning

Joint Training

3.3. Prompt-Based Web Agents

4. Multimodal AI Search

4.1. Multimodal Large Language Models

4.2. Multimodal Search

4.3. Multimodal Web Agents

5. Benchmarks

5.1. Text-Based QA Benchmark

5.2. Web Agent Benchmark

5.3. MM Search Benchmark

6. Softwares and Products

7. Challenges and Future Research

- •

- Methods: More complex problems lead to a prolonged search process and additional actions, resulting in an extended search context. This extended context can limit the effectiveness of AI search methods and the ability of LLMs, causing search performance to degrade as the inference length increases.

- •

- Evaluations: There is a strong need for systematic and standardized evaluation frameworks in AI search. The datasets used for evaluation should be designed to closely resemble real-world scenarios, featuring complex, dynamic, and citation-supported answers.

- •

- Applications: The potential real-world applications of AI Search are significant. Beyond user scenarios, there are numerous applications across various industries. We hope to see the development of more AI search software and products to enhance the interaction between humans and machines.

8. Conclusions

References

- Brin, S.; Page, L. The anatomy of a large-scale hypertextual web search engine. Computer networks and ISDN systems 1998, 30, 107–117.

- Berkhin, P. A survey on PageRank computing. Internet mathematics 2005, 2, 73–120.

- Burges, C.; Shaked, T.; Renshaw, E.; Lazier, A.; Deeds, M.; Hamilton, N.; Hullender, G. Learning to rank using gradient descent. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 22nd international conference on Machine learning, 2005, pp. 89–96.

- Nadkarni, P.M.; Ohno-Machado, L.; Chapman, W.W. Natural language processing: an introduction. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association 2011, 18, 544–551.

- Kobayashi, M.; Takeda, K. Information retrieval on the web. ACM computing surveys (CSUR) 2000, 32, 144–173.

- Zhao, W.X.; Zhou, K.; Li, J.; Tang, T.; Wang, X.; Hou, Y.; Min, Y.; Zhang, B.; Zhang, J.; Dong, Z.; et al. A survey of large language models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2303.18223 2023, 1.

- Research, C.D. https://openai.com/index/introducing-deep-research, 2022.

- Touvron, H.; Lavril, T.; Izacard, G.; Martinet, X.; Lachaux, M.A.; Lacroix, T.; Rozière, B.; Goyal, N.; Hambro, E.; Azhar, F.; et al. Llama: Open and efficient foundation language models. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2302.13971.

- Lewis, P.S.H.; Perez, E.; Piktus, A.; Petroni, F.; Karpukhin, V.; Goyal, N.; Küttler, H.; Lewis, M.; tau Yih, W.; Rocktäschel, T.; et al. Retrieval-Augmented Generation for Knowledge-Intensive NLP Tasks. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 33: Annual Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems 2020, NeurIPS 2020, December 6-12, 2020, virtual, 2020.

- Xu, F.; Shi, W.; Choi, E. RECOMP: Improving Retrieval-Augmented LMs with Compression and Selective Augmentation. CoRR 2023, abs/2310.04408, [2310.04408]. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.; Wu, Q.; Lin, C.Y.; Yang, Y.; Qiu, L. LLMLingua: Compressing Prompts for Accelerated Inference of Large Language Models. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2023 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing. Association for Computational Linguistics, 2023, pp. 13358–13376. [CrossRef]

- Jin, J.; Li, X.; Dong, G.; Zhang, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Wu, Y.; Li, Z.; Ye, Q.; Dou, Z. Hierarchical Document Refinement for Long-context Retrieval-augmented Generation, 2025, [arXiv:cs.CL/2505.10413].

- Kim, G.; Kim, S.; Jeon, B.; Park, J.; Kang, J. Tree of Clarifications: Answering Ambiguous Questions with Retrieval-Augmented Large Language Models. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2023 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, Singapore, 2023; pp. 996–1009. [CrossRef]

- Shi, W.; Min, S.; Yasunaga, M.; Seo, M.; James, R.; Lewis, M.; Zettlemoyer, L.; tau Yih, W. REPLUG: Retrieval-Augmented Black-Box Language Models. CoRR 2023, abs/2301.12652, [2301.12652]. [CrossRef]

- Yu, W.; Iter, D.; Wang, S.; Xu, Y.; Ju, M.; Sanyal, S.; Zhu, C.; Zeng, M.; Jiang, M. Generate rather than retrieve: Large language models are strong context generators. arXiv preprint arXiv:2209.10063 2022.

- Wang, H.; Zhao, T.; Gao, J. BlendFilter: Advancing Retrieval-Augmented Large Language Models via Query Generation Blending and Knowledge Filtering, 2024, [arXiv:cs.CL/2402.11129].

- Wang, Y.; Li, P.; Sun, M.; Liu, Y. Self-knowledge guided retrieval augmentation for large language models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2310.05002 2023.

- Wang, H.; Xue, B.; Zhou, B.; Zhang, T.; Wang, C.; Chen, G.; Wang, H.; Wong, K.f. Self-DC: When to retrieve and When to generate? Self Divide-and-Conquer for Compositional Unknown Questions. arXiv preprint arXiv:2402.13514 2024.

- Ding, H.; Pang, L.; Wei, Z.; Shen, H.; Cheng, X. Retrieve Only When It Needs: Adaptive Retrieval Augmentation for Hallucination Mitigation in Large Language Models, 2024, [arXiv:cs.CL/2402.10612].

- Tan, J.; Dou, Z.; Zhu, Y.; Guo, P.; Fang, K.; Wen, J.R. Small Models, Big Insights: Leveraging Slim Proxy Models To Decide When and What to Retrieve for LLMs. CoRR 2024, abs/2402.12052, [2402.12052]. [CrossRef]

- Yao, S.; Zhao, J.; Yu, D.; Shafran, I.; Narasimhan, K.R.; Cao, Y. ReAct: Synergizing Reasoning and Acting in Language Models. In Proceedings of the NeurIPS 2022 Foundation Models for Decision Making Workshop, 2022.

- Shao, Z.; Gong, Y.; Shen, Y.; Huang, M.; Duan, N.; Chen, W. Enhancing Retrieval-Augmented Large Language Models with Iterative Retrieval-Generation Synergy, 2023, [arXiv:cs.CL/2305.15294].

- Trivedi, H.; Balasubramanian, N.; Khot, T.; Sabharwal, A. Interleaving retrieval with chain-of-thought reasoning for knowledge-intensive multi-step questions. arXiv preprint arXiv:2212.10509 2022.

- Jiang, Z.; Xu, F.F.; Gao, L.; Sun, Z.; Liu, Q.; Dwivedi-Yu, J.; Yang, Y.; Callan, J.; Neubig, G. Active Retrieval Augmented Generation. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2023 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, EMNLP 2023, Singapore, December 6-10, 2023. Association for Computational Linguistics, 2023, pp. 7969–7992.

- Asai, A.; Wu, Z.; Wang, Y.; Sil, A.; Hajishirzi, H. Self-RAG: Learning to Retrieve, Generate, and Critique through Self-Reflection. CoRR 2023, abs/2310.11511, [2310.11511]. [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Dong, G.; Jin, J.; Zhang, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Zhang, P.; Dou, Z. Search-o1: Agentic Search-Enhanced Large Reasoning Models. CoRR 2025, abs/2501.05366, [2501.05366]. [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Jin, J.; Dong, G.; Qian, H.; Zhu, Y.; Wu, Y.; Wen, J.; Dou, Z. WebThinker: Empowering Large Reasoning Models with Deep Research Capability. CoRR 2025, abs/2504.21776, [2504.21776]. [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Li, B.; Fang, R.; Yin, W.; Zhang, L.; Tao, Z.; Zhang, D.; Xi, Z.; Jiang, Y.; Xie, P.; et al. WebDancer: Towards Autonomous Information Seeking Agency, 2025, [arXiv:cs.CL/2505.22648].

- Huang, L.; Liu, Y.; Jiang, J.; Zhang, R.; Yan, J.; Li, J.; Zhao, W.X. ManuSearch: Democratizing Deep Search in Large Language Models with a Transparent and Open Multi-Agent Framework, 2025, [arXiv:cs.CL/2505.18105].

- Yang, T.; Yao, Z.; Jin, B.; Cui, L.; Li, Y.; Wang, G.; Liu, X. Demystifying and Enhancing the Efficiency of Large Language Model Based Search Agents, 2025, [arXiv:cs.AI/2505.12065].

- Jin, J.; Li, X.; Dong, G.; Zhang, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Qian, H.; Dou, Z. Decoupled Planning and Execution: A Hierarchical Reasoning Framework for Deep Search, 2025, [arXiv:cs.AI/2507.02652].

- Wu, W.; Guan, X.; Huang, S.; Jiang, Y.; Xie, P.; Huang, F.; Cao, J.; Zhao, H.; Zhou, J. MaskSearch: A Universal Pre-Training Framework to Enhance Agentic Search Capability, 2025, [arXiv:cs.CL/2505.20285].

- Wang, L.; Chen, H.; Yang, N.; Huang, X.; Dou, Z.; Wei, F. Chain-of-Retrieval Augmented Generation, 2025, [arXiv:cs.IR/2501.14342].

- Lee, Z.; Cao, S.; Liu, J.; Zhang, J.; Liu, W.; Che, X.; Hou, L.; Li, J. ReaRAG: Knowledge-guided Reasoning Enhances Factuality of Large Reasoning Models with Iterative Retrieval Augmented Generation, 2025, [arXiv:cs.CL/2503.21729].

- Shi, Z.; Yan, L.; Yin, D.; Verberne, S.; de Rijke, M.; Ren, Z. Iterative Self-Incentivization Empowers Large Language Models as Agentic Searchers, 2025, [arXiv:cs.CL/2505.20128].

- Hu, M.; Fang, T.; Zhang, J.; Ma, J.; Zhang, Z.; Zhou, J.; Zhang, H.; Mi, H.; Yu, D.; King, I. WebCoT: Enhancing Web Agent Reasoning by Reconstructing Chain-of-Thought in Reflection, Branching, and Rollback, 2025, [arXiv:cs.CL/2505.20013].

- Guan, X.; Zeng, J.; Meng, F.; Xin, C.; Lu, Y.; Lin, H.; Han, X.; Sun, L.; Zhou, J. DeepRAG: Thinking to Retrieve Step by Step for Large Language Models, 2025, [arXiv:cs.AI/2502.01142].

- Jin, B.; Zeng, H.; Yue, Z.; Yoon, J.; Arik, S.; Wang, D.; Zamani, H.; Han, J. Search-R1: Training LLMs to Reason and Leverage Search Engines with Reinforcement Learning, 2025, [arXiv:cs.CL/2503.09516].

- Song, H.; Jiang, J.; Min, Y.; Chen, J.; Chen, Z.; Zhao, W.X.; Fang, L.; Wen, J.R. R1-Searcher: Incentivizing the Search Capability in LLMs via Reinforcement Learning, 2025, [arXiv:cs.AI/2503.05592].

- Chen, M.; Li, T.; Sun, H.; Zhou, Y.; Zhu, C.; Wang, H.; Pan, J.Z.; Zhang, W.; Chen, H.; Yang, F.; et al. ReSearch: Learning to Reason with Search for LLMs via Reinforcement Learning, 2025, [arXiv:cs.AI/2503.19470].

- Sun, H.; Qiao, Z.; Guo, J.; Fan, X.; Hou, Y.; Jiang, Y.; Xie, P.; Zhang, Y.; Huang, F.; Zhou, J. ZeroSearch: Incentivize the Search Capability of LLMs without Searching, 2025, [arXiv:cs.CL/2505.04588].

- Zheng, Y.; Fu, D.; Hu, X.; Cai, X.; Ye, L.; Lu, P.; Liu, P. DeepResearcher: Scaling Deep Research via Reinforcement Learning in Real-world Environments, 2025, [arXiv:cs.AI/2504.03160].

- Mei, J.; Hu, T.; Fu, D.; Wen, L.; Yang, X.; Wu, R.; Cai, P.; Cai, X.; Gao, X.; Yang, Y.; et al. O2-Searcher: A Searching-based Agent Model for Open-Domain Open-Ended Question Answering, 2025, [arXiv:cs.CL/2505.16582].

- Li, K.; Zhang, Z.; Yin, H.; Zhang, L.; Ou, L.; Wu, J.; Yin, W.; Li, B.; Tao, Z.; Wang, X.; et al. WebSailor: Navigating Super-human Reasoning for Web Agent, 2025, [arXiv:cs.CL/2507.02592].

- Tao, Z.; Wu, J.; Yin, W.; Zhang, J.; Li, B.; Shen, H.; Li, K.; Zhang, L.; Wang, X.; Jiang, Y.; et al. WebShaper: Agentically Data Synthesizing via Information-Seeking Formalization. arXiv preprint arXiv:2507.15061 2025.

- Wang, Z.; Zheng, X.; An, K.; Ouyang, C.; Cai, J.; Wang, Y.; Wu, Y. StepSearch: Igniting LLMs Search Ability via Step-Wise Proximal Policy Optimization, 2025, [arXiv:cs.CL/2505.15107].

- Wei, Z.; Yao, W.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, W.; Lu, Q.; Qiu, L.; Yu, C.; Xu, P.; Zhang, C.; Yin, B.; et al. WebAgent-R1: Training Web Agents via End-to-End Multi-Turn Reinforcement Learning, 2025, [arXiv:cs.CL/2505.16421].

- Lai, H.; Liu, X.; Iong, I.L.; Yao, S.; Chen, Y.; Shen, P.; Yu, H.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, X.; Dong, Y.; et al. AutoWebGLM: A Large Language Model-based Web Navigating Agent. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 30th ACM SIGKDD Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, New York, NY, USA, 2024; KDD ’24, p. 5295–5306. [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Xu, F.; Zhou, S.; Neubig, G. Beyond Browsing: API-Based Web Agents, 2025, [arXiv:cs.CL/2410.16464].

- Zhang, D.; Rama, B.; Ni, J.; He, S.; Zhao, F.; Chen, K.; Chen, A.; Cao, J. LiteWebAgent: The Open-Source Suite for VLM-Based Web-Agent Applications, 2025, [arXiv:cs.AI/2503.02950].

- Yang, K.; Liu, Y.; Chaudhary, S.; Fakoor, R.; Chaudhari, P.; Karypis, G.; Rangwala, H. AgentOccam: A Simple Yet Strong Baseline for LLM-Based Web Agents, 2025, [arXiv:cs.AI/2410.13825].

- Shi, W.; Tan, H.; Kuang, C.; Li, X.; Ren, X.; Zhang, C.; Chen, H.; Wang, Y.; Shang, L.; Yu, F.; et al. Pangu DeepDiver: Adaptive Search Intensity Scaling via Open-Web Reinforcement Learning, 2025, [arXiv:cs.CL/2505.24332].

- He, H.; Yao, W.; Ma, K.; Yu, W.; Dai, Y.; Zhang, H.; Lan, Z.; Yu, D. WebVoyager: Building an End-to-End Web Agent with Large Multimodal Models. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 62nd Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 1: Long Papers); Ku, L.W.; Martins, A.; Srikumar, V., Eds., Bangkok, Thailand, 2024; pp. 6864–6890. [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Li, B.; Fang, R.; Yin, W.; Zhang, L.; Tao, Z.; Zhang, D.; Xi, Z.; Jiang, Y.; Xie, P.; et al. WebDancer: Towards Autonomous Information Seeking Agency, 2025, [arXiv:cs.CL/2505.22648].

- Shen, H.; Liu, C.; Li, G.; Wang, X.; Zhou, Y.; Ma, C.; Ji, X. Falcon-UI: Understanding GUI Before Following User Instructions, 2024, [arXiv:cs.CL/2412.09362].

- Cho, J.; Kim, J.; Bae, D.; Choo, J.; Gwon, Y.; Kwon, Y.D. CAAP: Context-Aware Action Planning Prompting to Solve Computer Tasks with Front-End UI Only, 2024, [arXiv:cs.AI/2406.06947].

- Lin, K.Q.; Li, L.; Gao, D.; Yang, Z.; Wu, S.; Bai, Z.; Lei, W.; Wang, L.; Shou, M.Z. ShowUI: One Vision-Language-Action Model for GUI Visual Agent, 2024, [arXiv:cs.CV/2411.17465].

- Cao, T.; Huang, C.; Li, Y.; Huilin, W.; He, A.; Oo, N.; Hooi, B. PhishAgent: A Robust Multimodal Agent for Phishing Webpage Detection. Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence 2025, 39, 27869–27877. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, D.; Zhang, R.; Guo, Z.; Wu, Y.; Qiu, P.; Lu, P.; Chen, Z.; Song, G.; Gao, P.; Liu, Y.; et al. MMSearch: Unveiling the Potential of Large Models as Multi-modal Search Engines. In Proceedings of the The Thirteenth International Conference on Learning Representations.

- Wu, J.; Deng, Z.; Li, W.; Liu, Y.; You, B.; Li, B.; Ma, Z.; Liu, Z. MMSearch-R1: Incentivizing LMMs to Search, 2025, [arXiv:cs.CV/2506.20670].

- Pahuja, V.; Lu, Y.; Rosset, C.; Gou, B.; Mitra, A.; Whitehead, S.; Su, Y.; Awadallah, A. Explorer: Scaling exploration-driven web trajectory synthesis for multimodal web agents. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2502.11357.

- Verma, G.; Kaur, R.; Srishankar, N.; Zeng, Z.; Balch, T.; Veloso, M. AdaptAgent: Adapting Multimodal Web Agents with Few-Shot Learning from Human Demonstrations, 2024, [arXiv:cs.AI/2411.13451].

- He, H.; Yao, W.; Ma, K.; Yu, W.; Zhang, H.; Fang, T.; Lan, Z.; Yu, D. OpenWebVoyager: Building Multimodal Web Agents via Iterative Real-World Exploration, Feedback and Optimization, 2024, [arXiv:cs.CL/2410.19609].

- Zheng, B.; Gou, B.; Kil, J.; Sun, H.; Su, Y. Gpt-4v (ision) is a generalist web agent, if grounded. arXiv preprint arXiv:2401.01614 2024.

- Gadiraju, S.S.; Liao, D.; Kudupudi, A.; Kasula, S.; Chalasani, C. InfoTech Assistant: A Multimodal Conversational Agent for InfoTechnology Web Portal Queries. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE International Conference on Big Data (BigData), 2024, pp. 3264–3272. [CrossRef]

- Kwiatkowski, T.; Palomaki, J.; Redfield, O.; Collins, M.; Parikh, A.; Alberti, C.; Epstein, D.; Polosukhin, I.; Devlin, J.; Lee, K.; et al. Natural questions: a benchmark for question answering research. Transactions of the Association for Computational Linguistics 2019, 7, 453–466.

- Joshi, M.; Choi, E.; Weld, D.S.; Zettlemoyer, L. Triviaqa: A large scale distantly supervised challenge dataset for reading comprehension. arXiv preprint arXiv:1705.03551 2017.

- Mallen, A.; Asai, A.; Zhong, V.; Das, R.; Khashabi, D.; Hajishirzi, H. When not to trust language models: Investigating effectiveness of parametric and non-parametric memories. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2212.10511.

- Yang, Z.; Qi, P.; Zhang, S.; Bengio, Y.; Cohen, W.W.; Salakhutdinov, R.; Manning, C.D. HotpotQA: A dataset for diverse, explainable multi-hop question answering. arXiv preprint arXiv:1809.09600 2018.

- Trivedi, H.; Balasubramanian, N.; Khot, T.; Sabharwal, A. MuSiQue: Multihop Questions via Single-hop Question Composition. Transactions of the Association for Computational Linguistics 2022, 10, 539–554.

- Thorne, J.; Vlachos, A.; Christodoulopoulos, C.; Mittal, A. FEVER: a large-scale dataset for fact extraction and VERification. arXiv preprint arXiv:1803.05355 2018.

- Petroni, F.; Piktus, A.; Fan, A.; Lewis, P.; Yazdani, M.; De Cao, N.; Thorne, J.; Jernite, Y.; Karpukhin, V.; Maillard, J.; et al. KILT: a benchmark for knowledge intensive language tasks. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2009.02252.

- Mialon, G.; Fourrier, C.; Wolf, T.; LeCun, Y.; Scialom, T. Gaia: a benchmark for general ai assistants. In Proceedings of the The Twelfth International Conference on Learning Representations, 2023.

- Wei, J.; Sun, Z.; Papay, S.; McKinney, S.; Han, J.; Fulford, I.; Chung, H.W.; Passos, A.T.; Fedus, W.; Glaese, A. Browsecomp: A simple yet challenging benchmark for browsing agents. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2504.12516.

- Zhou, P.; Leon, B.; Ying, X.; Zhang, C.; Shao, Y.; Ye, Q.; Chong, D.; Jin, Z.; Xie, C.; Cao, M.; et al. Browsecomp-zh: Benchmarking web browsing ability of large language models in chinese. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2504.19314.

- Gou, B.; Huang, Z.; Ning, Y.; Gu, Y.; Lin, M.; Qi, W.; Kopanev, A.; Yu, B.; Gutiérrez, B.J.; Shu, Y.; et al. Mind2Web 2: Evaluating Agentic Search with Agent-as-a-Judge, 2025, [arXiv:cs.AI/2506.21506].

- Deng, X.; Gu, Y.; Zheng, B.; Chen, S.; Stevens, S.; Wang, B.; Sun, H.; Su, Y. Mind2Web: Towards a Generalist Agent for the Web. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems; Oh, A.; Naumann, T.; Globerson, A.; Saenko, K.; Hardt, M.; Levine, S., Eds. Curran Associates, Inc., 2023, Vol. 36, pp. 28091–28114.

- Zhou, S.; Xu, F.F.; Zhu, H.; Zhou, X.; Lo, R.; Sridhar, A.; Cheng, X.; Ou, T.; Bisk, Y.; Fried, D.; et al. WebArena: A Realistic Web Environment for Building Autonomous Agents, 2024, [arXiv:cs.AI/2307.13854].

- Koh, J.Y.; Lo, R.; Jang, L.; Duvvur, V.; Lim, M.; Huang, P.Y.; Neubig, G.; Zhou, S.; Salakhutdinov, R.; Fried, D. VisualWebArena: Evaluating Multimodal Agents on Realistic Visual Web Tasks. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 62nd Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 1: Long Papers); Ku, L.W.; Martins, A.; Srikumar, V., Eds., Bangkok, Thailand, 2024; pp. 881–905. [CrossRef]

- Garg, D.; VanWeelden, S.; Caples, D.; Draguns, A.; Ravi, N.; Putta, P.; Garg, N.; Abraham, T.; Lara, M.; Lopez, F.; et al. REAL: Benchmarking Autonomous Agents on Deterministic Simulations of Real Websites, 2025, [arXiv:cs.AI/2504.11543].

- Miyai, A.; Zhao, Z.; Egashira, K.; Sato, A.; Sunada, T.; Onohara, S.; Yamanishi, H.; Toyooka, M.; Nishina, K.; Maeda, R.; et al. WebChoreArena: Evaluating Web Browsing Agents on Realistic Tedious Web Tasks, 2025, [arXiv:cs.CL/2506.01952].

- Song, Y.; Thai, K.; Pham, C.M.; Chang, Y.; Nadaf, M.; Iyyer, M. BEARCUBS: A benchmark for computer-using web agents, 2025, [arXiv:cs.AI/2503.07919].

- Pan, Y.; Kong, D.; Zhou, S.; Cui, C.; Leng, Y.; Jiang, B.; Liu, H.; Shang, Y.; Zhou, S.; Wu, T.; et al. WebCanvas: Benchmarking Web Agents in Online Environments, 2024, [arXiv:cs.CL/2406.12373].

- Xu, K.; Kordi, Y.; Nayak, T.; Asija, A.; Wang, Y.; Sanders, K.; Byerly, A.; Zhang, J.; Van Durme, B.; Khashabi, D. TurkingBench: A Challenge Benchmark for Web Agents. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2025 Conference of the Nations of the Americas Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies (Volume 1: Long Papers); Chiruzzo, L.; Ritter, A.; Wang, L., Eds., Albuquerque, New Mexico, 2025; pp. 3694–3710. [CrossRef]

- Tur, A.D.; Meade, N.; Lù, X.H.; Zambrano, A.; Patel, A.; Durmus, E.; Gella, S.; Stańczak, K.; Reddy, S. SafeArena: Evaluating the Safety of Autonomous Web Agents, 2025, [arXiv:cs.LG/2503.04957].

- Zhu, Y.; Kellermann, A.; Bowman, D.; Li, P.; Gupta, A.; Danda, A.; Fang, R.; Jensen, C.; Ihli, E.; Benn, J.; et al. CVE-Bench: A Benchmark for AI Agents’ Ability to Exploit Real-World Web Application Vulnerabilities, 2025, [arXiv:cs.CR/2503.17332].

- Evtimov, I.; Zharmagambetov, A.; Grattafiori, A.; Guo, C.; Chaudhuri, K. WASP: Benchmarking Web Agent Security Against Prompt Injection Attacks, 2025, [arXiv:cs.CR/2504.18575].

- Qiu, H.; Fabbri, A.; Agarwal, D.; Huang, K.H.; Tan, S.; Peng, N.; Wu, C.S. Evaluating Cultural and Social Awareness of LLM Web Agents. In Proceedings of the Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: NAACL 2025; Chiruzzo, L.; Ritter, A.; Wang, L., Eds., Albuquerque, New Mexico, 2025; pp. 3978–4005. [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Li, Z.; Liu, J.; Cui, J.; Zhao, X.; Shen, Z. Open CaptchaWorld: A Comprehensive Web-based Platform for Testing and Benchmarking Multimodal LLM Agents, 2025, [arXiv:cs.AI/2505.24878].

- Lyu, Y.; Zhang, X.; Yan, L.; de Rijke, M.; Ren, Z.; Chen, X. DeepShop: A Benchmark for Deep Research Shopping Agents, 2025, [arXiv:cs.IR/2506.02839].

- Fu, M.; Peng, Y.; Liu, B.; Wan, Y.; Chen, D. LiveVQA: Live Visual Knowledge Seeking. arXiv preprint arXiv:2504.05288 2025.

- Yu, Q.; Xiao, Z.; Li, B.; Wang, Z.; Chen, C.; Zhang, W. MRAMG-Bench: A BeyondText Benchmark for Multimodal Retrieval-Augmented Multimodal Generation. arXiv preprint arXiv:2502.04176 2025.

- Research, P.D. https://www.perplexity.ai, 2022.

- Doubao. https://www.doubao.com, 2023.

- Yuanbao. https://yuanbao.tencent.com, 2024.

- AI, N. https://www.n.cn, 2025.

- Kimi. https://www.kimi.com, 2023.

- DeepSearch, Q. https://quark.sm.cn, 2025.

- Research, G.D. https://gemini.google/overview/deep-research, 2023.

- DeepSeek. https://www.deepseek.com, 2025.

- Team, M.A. MiroThinker: An open-source agentic model series trained for deep research and complex, long-horizon problem solving. https://github.com/MiroMindAI/MiroThinker, 2025.

- Manus. https://manus.im/, 2025.

- MediSearch. https://medisearch.io, 2023.

- Devv.ai. https://devv.ai/zh, 2023.

- Consensus. https://consensus.app, 2022.

- walles.ai. https://walles.ai/, 2023.

- Chat, B. http://bing.com, 2023.

- Gao, Y.; Xiong, Y.; Gao, X.; Jia, K.; Pan, J.; Bi, Y.; Dai, Y.; Sun, J.; Guo, Q.; Wang, M.; et al. Retrieval-Augmented Generation for Large Language Models: A Survey, 2024, [arXiv:cs.CL/2312.10997].

- Zhu, Y.; Yuan, H.; Wang, S.; Liu, J.; Liu, W.; Deng, C.; Chen, H.; Liu, Z.; Dou, Z.; Wen, J.R. Large language models for information retrieval: A survey. arXiv preprint arXiv:2308.07107 2023.

- Ramos, J.; et al. Using tf-idf to determine word relevance in document queries. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the first instructional conference on machine learning. Citeseer, 2003, Vol. 242, pp. 29–48.

- Robertson, S.E.; Zaragoza, H. The Probabilistic Relevance Framework: BM25 and Beyond. Found. Trends Inf. Retr. 2009, 3, 333–389. [CrossRef]

- Karpukhin, V.; Oguz, B.; Min, S.; Lewis, P.; Wu, L.; Edunov, S.; Chen, D.; Yih, W.t. Dense Passage Retrieval for Open-Domain Question Answering. In Proceedings of the EMNLP, 2020, pp. 6769–6781.

- Xiong, L.; Xiong, C.; Li, Y.; Tang, K.F.; Liu, J.; Bennett, P.N.; Ahmed, J.; Overwijk, A. Approximate Nearest Neighbor Negative Contrastive Learning for Dense Text Retrieval. In Proceedings of the ICLR, 2020.

- Wang, L.; Yang, N.; Huang, X.; Jiao, B.; Yang, L.; Jiang, D.; Majumder, R.; Wei, F. Text Embeddings by Weakly-Supervised Contrastive Pre-training. CoRR 2022, abs/2212.03533, [2212.03533]. [CrossRef]

- Xiao, S.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, P.; Muennighoff, N.; Lian, D.; Nie, J.Y. C-Pack: Packed Resources For General Chinese Embeddings, 2024, [arXiv:cs.CL/2309.07597].

- Li, X.; Jin, J.; Zhou, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, P.; Zhu, Y.; Dou, Z. From matching to generation: A survey on generative information retrieval. ACM Transactions on Information Systems 2025, 43, 1–62.

- Tay, Y.; Tran, V.; Dehghani, M.; Ni, J.; Bahri, D.; Mehta, H.; Qin, Z.; Hui, K.; Zhao, Z.; Gupta, J.P.; et al. Transformer Memory as a Differentiable Search Index. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 35: Annual Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems 2022, NeurIPS 2022, New Orleans, LA, USA, November 28 - December 9, 2022, 2022.

- Wang, Y.; Hou, Y.; Wang, H.; Miao, Z.; Wu, S.; Chen, Q.; Xia, Y.; Chi, C.; Zhao, G.; Liu, Z.; et al. A neural corpus indexer for document retrieval. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2022, 35, 25600–25614.

- Li, X.; Dou, Z.; Zhou, Y.; Liu, F. Corpuslm: Towards a unified language model on corpus for knowledge-intensive tasks. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 47th International ACM SIGIR Conference on Research and Development in Information Retrieval, 2024, pp. 26–37.

- Liu, T.Y.; et al. Learning to rank for information retrieval. Foundations and Trends® in Information Retrieval 2009, 3, 225–331.

- Khattab, O.; Zaharia, M. ColBERT: Efficient and Effective Passage Search via Contextualized Late Interaction over BERT. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 43rd International ACM SIGIR conference on research and development in Information Retrieval, SIGIR 2020, Virtual Event, China, July 25-30, 2020. ACM, 2020, pp. 39–48. [CrossRef]

- Sun, W.; Yan, L.; Ma, X.; Wang, S.; Ren, P.; Chen, Z.; Yin, D.; Ren, Z. Is ChatGPT Good at Search? Investigating Large Language Models as Re-Ranking Agents. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2023 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, EMNLP 2023, Singapore, December 6-10, 2023; Bouamor, H.; Pino, J.; Bali, K., Eds. Association for Computational Linguistics, 2023, pp. 14918–14937. [CrossRef]

- Izacard, G.; Grave, E. Leveraging passage retrieval with generative models for open domain question answering. arXiv preprint arXiv:2007.01282 2020.

- Guu, K.; Lee, K.; Tung, Z.; Pasupat, P.; Chang, M. Retrieval augmented language model pre-training. In Proceedings of the International conference on machine learning. PMLR, 2020, pp. 3929–3938.

- Borgeaud, S.; Mensch, A.; Hoffmann, J.; Cai, T.; Rutherford, E.; Millican, K.; van den Driessche, G.; Lespiau, J.B.; Damoc, B.; Clark, A.; et al. Improving Language Models by Retrieving from Trillions of Tokens. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning, ICML 2022, 17-23 July 2022, Baltimore, Maryland, USA. PMLR, 2022, Vol. 162, Proceedings of Machine Learning Research, pp. 2206–2240.

- Ma, X.; Gong, Y.; He, P.; Zhao, H.; Duan, N. Query Rewriting in Retrieval-Augmented Large Language Models. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2023 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, Singapore, 2023; pp. 5303–5315. [CrossRef]

- Ram, O.; Levine, Y.; Dalmedigos, I.; Muhlgay, D.; Shashua, A.; Leyton-Brown, K.; Shoham, Y. In-context retrieval-augmented language models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2302.00083 2023.

- Yu, Z.; Xiong, C.; Yu, S.; Liu, Z. Augmentation-adapted retriever improves generalization of language models as generic plug-in. arXiv preprint arXiv:2305.17331 2023.

- Zhang, P.; Xiao, S.; Liu, Z.; Dou, Z.; Nie, J.Y. Retrieve Anything To Augment Large Language Models. CoRR 2023, abs/2310.07554, [2310.07554]. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Yu, Y.; Wang, K.; Zhang, C. ARL2: Aligning Retrievers for Black-box Large Language Models via Self-guided Adaptive Relevance Labeling, 2024, [arXiv:cs.CL/2402.13542].

- Liu, N.F.; Lin, K.; Hewitt, J.; Paranjape, A.; Bevilacqua, M.; Petroni, F.; Liang, P. Lost in the Middle: How Language Models Use Long Contexts, 2023. arXiv:2307.03172.

- Cuconasu, F.; Trappolini, G.; Siciliano, F.; Filice, S.; Campagnano, C.; Maarek, Y.; Tonellotto, N.; Silvestri, F. The Power of Noise: Redefining Retrieval for RAG Systems, 2024, [arXiv:cs.IR/2401.14887].

- Yang, H.; Li, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, J.; Cheng, N.; Li, M.; Xiao, J. PRCA: Fitting Black-Box Large Language Models for Retrieval Question Answering via Pluggable Reward-Driven Contextual Adapter. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2023 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, EMNLP 2023, Singapore, December 6-10, 2023. Association for Computational Linguistics, 2023, pp. 5364–5375.

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, T.; Chen, S.; Wang, K.; Zeng, X.; Lin, H.; Han, X.; Sun, L.; Lu, C. ARise: Towards Knowledge-Augmented Reasoning via Risk-Adaptive Search. arXiv preprint arXiv:2504.10893 2025.

- Press, O.; Zhang, M.; Min, S.; Schmidt, L.; Smith, N.; Lewis, M. Measuring and Narrowing the Compositionality Gap in Language Models. In Proceedings of the Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: EMNLP 2023, Singapore, 2023; pp. 5687–5711. [CrossRef]

- Yoran, O.; Wolfson, T.; Ram, O.; Berant, J. Making Retrieval-Augmented Language Models Robust to Irrelevant Context, 2023, [arXiv:cs.CL/2310.01558].

- Huang, Y.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, H.; Li, K.; Fang, M.; Yang, L.; Li, X.; Shang, L.; Xu, S.; Hao, J.; et al. Deep Research Agents: A Systematic Examination And Roadmap, 2025, [arXiv:cs.AI/2506.18096].

- Zhang, W.; Li, Y.; Bei, Y.; Luo, J.; Wan, G.; Yang, L.; Xie, C.; Yang, Y.; Huang, W.C.; Miao, C.; et al. From Web Search towards Agentic Deep Research: Incentivizing Search with Reasoning Agents, 2025, [arXiv:cs.IR/2506.18959].

- Xu, R.; Peng, J. A Comprehensive Survey of Deep Research: Systems, Methodologies, and Applications, 2025, [arXiv:cs.AI/2506.12594].

- Sun, S.; Song, H.; Wang, Y.; Ren, R.; Jiang, J.; Zhang, J.; Bai, F.; Deng, J.; Zhao, W.X.; Liu, Z.; et al. SimpleDeepSearcher: Deep Information Seeking via Web-Powered Reasoning Trajectory Synthesis, 2025, [arXiv:cs.CL/2505.16834].

- Rafailov, R.; Sharma, A.; Mitchell, E.; Ermon, S.; Manning, C.D.; Finn, C. Direct Preference Optimization: Your Language Model is Secretly a Reward Model, 2024, [arXiv:cs.LG/2305.18290].

- Schulman, J.; Wolski, F.; Dhariwal, P.; Radford, A.; Klimov, O. Proximal Policy Optimization Algorithms, 2017, [arXiv:cs.LG/1707.06347].

- Shao, Z.; Wang, P.; Zhu, Q.; Xu, R.; Song, J.; Bi, X.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, M.; Li, Y.K.; Wu, Y.; et al. DeepSeekMath: Pushing the Limits of Mathematical Reasoning in Open Language Models, 2024, [arXiv:cs.CL/2402.03300].

- Hu, J.; Liu, J.K.; Shen, W. REINFORCE++: An Efficient RLHF Algorithm with Robustness to Both Prompt and Reward Models, 2025, [arXiv:cs.CL/2501.03262].

- Li, K.; Zhang, Z.; Yin, H.; Zhang, L.; Ou, L.; Wu, J.; Yin, W.; Li, B.; Tao, Z.; Wang, X.; et al. WebSailor: Navigating Super-human Reasoning for Web Agent, 2025, [arXiv:cs.CL/2507.02592].

- Shi, W.; Tan, H.; Kuang, C.; Li, X.; Ren, X.; Zhang, C.; Chen, H.; Wang, Y.; Shang, L.; Yu, F.; et al. Pangu DeepDiver: Adaptive Search Intensity Scaling via Open-Web Reinforcement Learning, 2025, [arXiv:cs.CL/2505.24332].

- Shi, Y.; Li, S.; Wu, C.; Liu, Z.; Fang, J.; Cai, H.; Zhang, A.; Wang, X. Search and Refine During Think: Autonomous Retrieval-Augmented Reasoning of LLMs, 2025, [arXiv:cs.CL/2505.11277].

- Dong, G.; Chen, Y.; Li, X.; Jin, J.; Qian, H.; Zhu, Y.; Mao, H.; Zhou, G.; Dou, Z.; Wen, J.R. Tool-Star: Empowering LLM-Brained Multi-Tool Reasoner via Reinforcement Learning, 2025, [arXiv:cs.CL/2505.16410].

- Lin, C.; Wen, Y.; Su, D.; Sun, F.; Chen, M.; Bao, C.; Lv, Z. Knowledgeable-r1: Policy Optimization for Knowledge Exploration in Retrieval-Augmented Generation, 2025, [arXiv:cs.CL/2506.05154].

- Qian, H.; Liu, Z. Scent of Knowledge: Optimizing Search-Enhanced Reasoning with Information Foraging, 2025, [arXiv:cs.CL/2505.09316].

- Li, Y.; Luo, Q.; Li, X.; Li, B.; Cheng, Q.; Wang, B.; Zheng, Y.; Wang, Y.; Yin, Z.; Qiu, X. R3-RAG: Learning Step-by-Step Reasoning and Retrieval for LLMs via Reinforcement Learning, 2025, [arXiv:cs.CL/2505.23794].

- Zhang, D.; Zhao, Y.; Wu, J.; Li, B.; Yin, W.; Zhang, L.; Jiang, Y.; Li, Y.; Tu, K.; Xie, P.; et al. EvolveSearch: An Iterative Self-Evolving Search Agent, 2025, [arXiv:cs.CL/2505.22501].

- Sha, Z.; Cui, S.; Wang, W. SEM: Reinforcement Learning for Search-Efficient Large Language Models, 2025, [arXiv:cs.CL/2505.07903].

- Wu, P.; Zhang, M.; Zhang, X.; Du, X.; Chen, Z.Z. Search Wisely: Mitigating Sub-optimal Agentic Searches By Reducing Uncertainty, 2025, [arXiv:cs.CL/2505.17281].

- Jiang, P.; Xu, X.; Lin, J.; Xiao, J.; Wang, Z.; Sun, J.; Han, J. s3: You Don’t Need That Much Data to Train a Search Agent via RL, 2025, [arXiv:cs.AI/2505.14146].

- Zhang, C.; He, S.; Qian, J.; Li, B.; Li, L.; Qin, S.; Kang, Y.; Ma, M.; Liu, G.; Lin, Q.; et al. Large Language Model-Brained GUI Agents: A Survey. Transactions on Machine Learning Research 2025.

- Ning, L.; Liang, Z.; Jiang, Z.; Qu, H.; Ding, Y.; Fan, W.; yong Wei, X.; Lin, S.; Liu, H.; Yu, P.S.; et al. A Survey of WebAgents: Towards Next-Generation AI Agents for Web Automation with Large Foundation Models, 2025, [arXiv:cs.AI/2503.23350].

- Wang, L.; Ma, C.; Feng, X.; Zhang, Z.; Yang, H.; Zhang, J.; Chen, Z.; Tang, J.; Chen, X.; Lin, Y.; et al. A survey on large language model based autonomous agents. Frontiers of Computer Science 2024, 18. [CrossRef]

- Hong, S.; Zhuge, M.; Chen, J.; Zheng, X.; Cheng, Y.; Wang, J.; Zhang, C.; Wang, Z.; Yau, S.K.S.; Lin, Z.; et al. MetaGPT: Meta Programming for A Multi-Agent Collaborative Framework. In Proceedings of the The Twelfth International Conference on Learning Representations, 2024.

- Zhang, H.; Du, W.; Shan, J.; Zhou, Q.; Du, Y.; Tenenbaum, J.B.; Shu, T.; Gan, C. Building Cooperative Embodied Agents Modularly with Large Language Models. In Proceedings of the The Twelfth International Conference on Learning Representations, 2024.

- Zhu, X.; Chen, Y.; Tian, H.; Tao, C.; Su, W.; Yang, C.; Huang, G.; Li, B.; Lu, L.; Wang, X.; et al. Ghost in the Minecraft: Generally Capable Agents for Open-World Environments via Large Language Models with Text-based Knowledge and Memory, 2023, [arXiv:cs.AI/2305.17144].

- Chen, W.; Su, Y.; Zuo, J.; Yang, C.; Yuan, C.; Chan, C.M.; Yu, H.; Lu, Y.; Hung, Y.H.; Qian, C.; et al. AgentVerse: Facilitating Multi-Agent Collaboration and Exploring Emergent Behaviors, 2023, [arXiv:cs.CL/2308.10848].

- Furuta, H.; Lee, K.H.; Nachum, O.; Matsuo, Y.; Faust, A.; Gu, S.S.; Gur, I. Multimodal Web Navigation with Instruction-Finetuned Foundation Models. In Proceedings of the The Twelfth International Conference on Learning Representations, 2024.

- Tang, X.; Kim, K.; Song, Y.; Lothritz, C.; Li, B.; Ezzini, S.; Tian, H.; Klein, J.; Bissyandé, T.F. CodeAgent: Autonomous Communicative Agents for Code Review. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2024 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing; Al-Onaizan, Y.; Bansal, M.; Chen, Y.N., Eds., Miami, Florida, USA, 2024; pp. 11279–11313. [CrossRef]

- Alam, M.A.; Mahmud, S.; Mamun-or Rashid, M.; Khan, M.M. Optimizing node selection in search based multi-agent path finding. Autonomous Agents and Multi-Agent Systems 2025, 39, 1–24.

- Dorri, A.; Kanhere, S.S.; Jurdak, R. Multi-agent systems: A survey. Ieee Access 2018, 6, 28573–28593.

- Cao, Y.; Yu, W.; Ren, W.; Chen, G. An Overview of Recent Progress in the Study of Distributed Multi-Agent Coordination. IEEE Transactions on Industrial Informatics 2013, 9, 427–438. [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Yin, W.; Jiang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Xi, Z.; Fang, R.; Zhang, L.; He, Y.; Zhou, D.; Xie, P.; et al. WebWalker: Benchmarking LLMs in Web Traversal, 2025, [arXiv:cs.CL/2501.07572].

- Qi, Z.; Liu, X.; Iong, I.L.; Lai, H.; Sun, X.; Zhao, W.; Yang, Y.; Yang, X.; Sun, J.; Yao, S.; et al. WebRL: Training LLM Web Agents via Self-Evolving Online Curriculum Reinforcement Learning, 2025, [arXiv:cs.CL/2411.02337].

- Zhuang, Y.; Jin, D.; Chen, J.; Shi, W.; Wang, H.; Zhang, C. WorkForceAgent-R1: Incentivizing Reasoning Capability in LLM-based Web Agents via Reinforcement Learning, 2025, [arXiv:cs.CL/2505.22942].

- Shao, Z.; Wang, P.; Zhu, Q.; Xu, R.; Song, J.; Bi, X.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, M.; Li, Y.K.; Wu, Y.; et al. DeepSeekMath: Pushing the Limits of Mathematical Reasoning in Open Language Models, 2024, [arXiv:cs.CL/2402.03300].

- Yu, Q.; Zhang, Z.; Zhu, R.; Yuan, Y.; Zuo, X.; Yue, Y.; Dai, W.; Fan, T.; Liu, G.; Liu, L.; et al. DAPO: An Open-Source LLM Reinforcement Learning System at Scale, 2025, [arXiv:cs.LG/2503.14476].

- Wei, J.; Wang, X.; Schuurmans, D.; Bosma, M.; ichter, b.; Xia, F.; Chi, E.; Le, Q.V.; Zhou, D. Chain-of-Thought Prompting Elicits Reasoning in Large Language Models. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems; Koyejo, S.; Mohamed, S.; Agarwal, A.; Belgrave, D.; Cho, K.; Oh, A., Eds. Curran Associates, Inc., 2022, Vol. 35, pp. 24824–24837.

- Jia, B.; Manocha, D. Sim-to-Real Brush Manipulation using Behavior Cloning and Reinforcement Learning, 2023, [arXiv:cs.RO/2309.08457].

- Luo, H.; Kuang, J.; Liu, W.; Shen, Y.; Luan, J.; Deng, Y. Browsing Like Human: A Multimodal Web Agent with Experiential Fast-and-Slow Thinking. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 63rd Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 1: Long Papers); Che, W.; Nabende, J.; Shutova, E.; Pilehvar, M.T., Eds., Vienna, Austria, 2025; pp. 14232–14251. [CrossRef]

- Hu, M.; Fang, T.; Zhang, J.; Ma, J.; Zhang, Z.; Zhou, J.; Zhang, H.; Mi, H.; Yu, D.; King, I. WebCoT: Enhancing Web Agent Reasoning by Reconstructing Chain-of-Thought in Reflection, Branching, and Rollback, 2025, [arXiv:cs.CL/2505.20013].

- Pal, K.K.; Kashihara, K.; Anantheswaran, U.; Kuznia, K.C.; Jagtap, S.; Baral, C. Exploring the Limits of Transfer Learning with Unified Model in the Cybersecurity Domain, 2023, [arXiv:cs.CL/2302.10346].

- Dosovitskiy, A.; Beyer, L.; Kolesnikov, A.; Weissenborn, D.; Zhai, X.; Unterthiner, T.; Dehghani, M.; Minderer, M.; Heigold, G.; Gelly, S.; et al. An Image is Worth 16x16 Words: Transformers for Image Recognition at Scale. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Learning Representations, 2021.

- Jiang, W.; Zhuang, Y.; Song, C.; Yang, X.; Zhou, J.T.; Zhang, C. AppAgentX: Evolving GUI Agents as Proficient Smartphone Users, 2025, [arXiv:cs.AI/2503.02268].

- Alabastro, Z.M.; Ilagan, J.B.; To, L.A.; Ilagan, J.R. Applied Optical Character Recognition and Large Language Models in Augmenting Manual Business Processes for Data Analytics in Traditional Small Businesses with Minimal Digital Adoption. In Proceedings of the Artificial Intelligence in HCI; Degen, H.; Ntoa, S., Eds., Cham, 2025; pp. 267–276.

- Wang, X.; Chen, Y.; Zhu, W. A Survey on Curriculum Learning. IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence 2022, 44, 4555–4576. [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Koenig, S.; Dilkina, B. Reprompt: Planning by automatic prompt engineering for large language models agents. arXiv preprint arXiv:2406.11132 2024.

- Samarasekara, I.; Bandara, M.; Rabhi, F.; Benatallah, B.; Meymandpour, R. LLM driven approach for capability modelling with context-enriched prompt engineering 2024.

- Gangi Reddy, R.; Mukherjee, S.; Kim, J.; Wang, Z.; Hakkani-Tür, D.; Ji, H. Infogent: An Agent-Based Framework for Web Information Aggregation. In Proceedings of the Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: NAACL 2025; Chiruzzo, L.; Ritter, A.; Wang, L., Eds., Albuquerque, New Mexico, 2025; pp. 5745–5758. [CrossRef]

- Koh, J.Y.; McAleer, S.; Fried, D.; Salakhutdinov, R. Tree Search for Language Model Agents, 2024, [arXiv:cs.AI/2407.01476].

- Achiam, J.; Adler, S.; Agarwal, S.; Ahmad, L.; Akkaya, I.; Aleman, F.L.; Almeida, D.; Altenschmidt, J.; Altman, S.; Anadkat, S.; et al. Gpt-4 technical report. arXiv preprint arXiv:2303.08774 2023.

- Jin, Y.; Li, J.; Liu, Y.; Gu, T.; Wu, K.; Jiang, Z.; He, M.; Zhao, B.; Tan, X.; Gan, Z.; et al. Efficient multimodal large language models: A survey. arXiv preprint arXiv:2405.10739 2024.

- OpenAI. Hello GPT-4o, 2024.

- Anthropic. Claude 3.5 Sonnet, 2024.

- Dai, W.; Li, J.; Li, D.; Tiong, A.M.H.; Zhao, J.; Wang, W.; Li, B.; Fung, P.N.; Hoi, S. Instructblip: Towards general-purpose vision-language models with instruction tuning. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2024, 36.

- Li, J.; Li, D.; Savarese, S.; Hoi, S. Blip-2: Bootstrapping language-image pre-training with frozen image encoders and large language models. In Proceedings of the International conference on machine learning. PMLR, 2023, pp. 19730–19742.

- Liu, H.; Li, C.; Wu, Q.; Lee, Y.J. Visual Instruction Tuning. In Proceedings of the NeurIPS, 2023.

- Liu, H.; Li, C.; Li, Y.; Lee, Y.J. Improved baselines with visual instruction tuning. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 2024, pp. 26296–26306.

- Bai, S.; Chen, K.; Liu, X.; Wang, J.; Ge, W.; Song, S.; Dang, K.; Wang, P.; Wang, S.; Tang, J.; et al. Qwen2. 5-vl technical report. arXiv preprint arXiv:2502.13923 2025.

- Team, G.; Anil, R.; Borgeaud, S.; Wu, Y.; Alayrac, J.B.; Yu, J.; Soricut, R.; Schalkwyk, J.; Dai, A.M.; Hauth, A.; et al. Gemini: a family of highly capable multimodal models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2312.11805 2023.

- Chen, Z.; Wu, J.; Wang, W.; Su, W.; Chen, G.; Xing, S.; Muyan, Z.; Zhang, Q.; Zhu, X.; Lu, L.; et al. Internvl: Scaling up vision foundation models and aligning for generic visual-linguistic tasks. arXiv preprint arXiv:2312.14238 2023.

- Sun, Q.; Cui, Y.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, F.; Yu, Q.; Luo, Z.; Wang, Y.; Rao, Y.; Liu, J.; Huang, T.; et al. Generative multimodal models are in-context learners. arXiv preprint arXiv:2312.13286 2023.

- Li, J.; Lu, W.; Fei, H.; Luo, M.; Dai, M.; Xia, M.; Jin, Y.; Gan, Z.; Qi, D.; Fu, C.; et al. A survey on benchmarks of multimodal large language models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2408.08632 2024.

- Geng, X.; Xia, P.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, X.; Wang, Q.; Ding, R.; Wang, C.; Wu, J.; Zhao, Y.; Li, K.; et al. WebWatcher: Breaking New Frontiers of Vision-Language Deep Research Agent. arXiv preprint arXiv:2508.05748 2025.

- Xie, J.; Chen, Z.; Zhang, R.; Wan, X.; Li, G. Large Multimodal Agents: A Survey, 2024, [arXiv:cs.CV/2402.15116].

- Hong, W.; Wang, W.; Lv, Q.; Xu, J.; Yu, W.; Ji, J.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Dong, Y.; Ding, M.; et al. Cogagent: A visual language model for gui agents. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 2024, pp. 14281–14290.

- He, H.; Yao, W.; Ma, K.; Yu, W.; Dai, Y.; Zhang, H.; Lan, Z.; Yu, D. WebVoyager: Building an end-to-end web agent with large multimodal models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2401.13919 2024.

- Vibhute, M.; Gutierrez, N.; Radivojevic, K.; Brenner, P. Multimodal Web Agents for Automated (Dark) Web Navigation.

- Ho, X.; Nguyen, A.K.D.; Sugawara, S.; Aizawa, A. Constructing a multi-hop qa dataset for comprehensive evaluation of reasoning steps. arXiv preprint arXiv:2011.01060 2020.

- Fernández-Pichel, M.; Pichel, J.C.; Losada, D.E. Evaluating Search Engines and Large Language Models for Answering Health Questions. arXiv preprint arXiv:2407.12468 2024.

- You.com. https://you.com, 2021.

- Yang, A.; Li, A.; Yang, B.; Zhang, B.; Hui, B.; Zheng, B.; Yu, B.; Gao, C.; Huang, C.; Lv, C.; et al. Qwen3 technical report. arXiv preprint arXiv:2505.09388 2025.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).