Case Study

We report the case of a 74-year-old left-handed male who was previously fully independent and initially presented to the neurology outpatient clinic with episodic sense of disequilibrium and a three-month history of progressive gait decline. Other neurological symptoms included intermittent abnormal paranesthesia in all four limbs, described by the patient as “bubbles popping under his skin,” extending to the trunk. At this stage, he did not report any evident neuropsychiatric symptoms, such as behavioral or emotional changes, confusion, and there were no bulbar symptoms, visual disturbances, or other focal weaknesses.

His past medical history included atrial fibrillation and previous smoking. There was a history of asbestos exposure. He had no history of cancer, cerebrovascular accident (CVA) or type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM). There was no history of alcohol use disorder. His regular medications included apixaban 5 mg BD, rosuvastatin 10 mg daily, pantoprazole 40 mg daily, and metoprolol 50 mg BD. There was no significant neurological family history.

The patient was scheduled for elective admission for further investigation. By the time of admission, he had developed additional neurological signs, including new-onset pyramidal weakness in the left upper limb and opsoclonus. Furthermore, whilst an inpatient undergoing investigation, he experienced rapid neurological deterioration, with worsening gait ataxia and left-sided distal weakness accompanied by an ulnar claw, suggestive of ulnar nerve dysfunction .The patient was admitted for further investigations. By the time of his admission, he demonstrated progression of neurological symptoms, including new pyramidal weakness in the left upper limb and opsoclonus. As an inpatient undergoing investigation, his symptoms further deteriorated, with severe gait ataxia and left-sided distal weakness with an ulnar claw, indicative of ulnar nerve dysfunction.

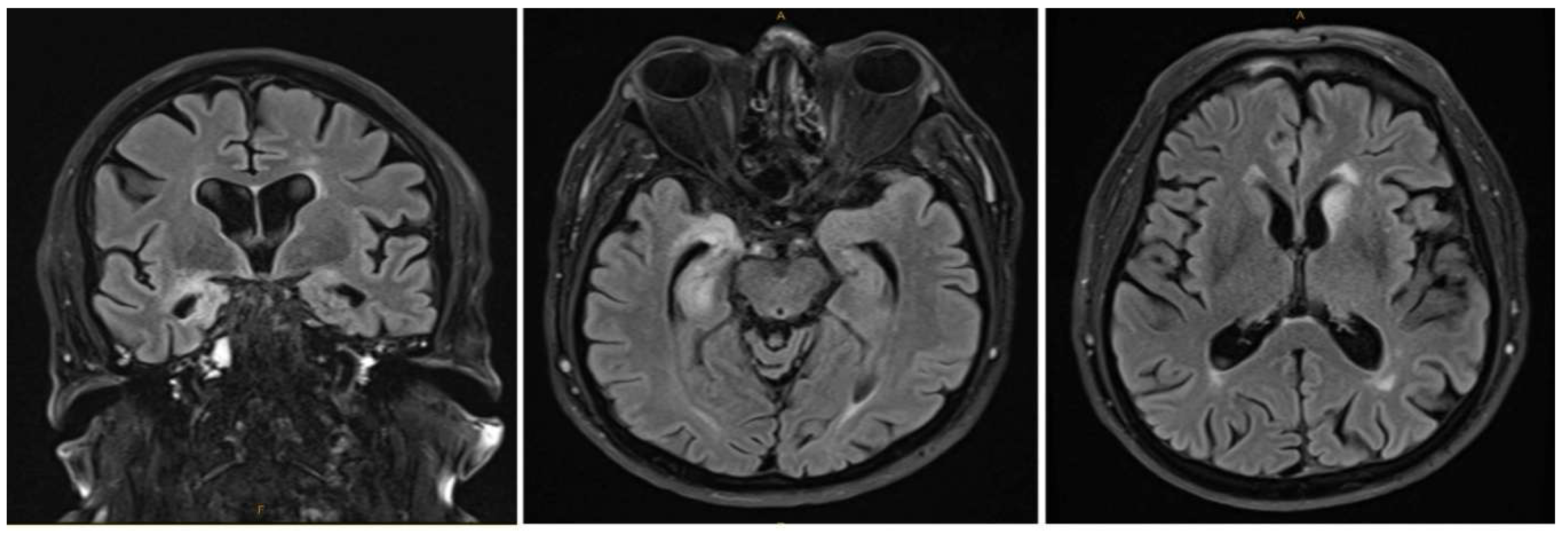

Initial laboratory investigations tests, including a full blood count, electrolytes, liver function tests, and infective serology (including HSV), were within normal limits. The chest X-ray was also unremarkable. normal. Neuroimaging Brain MRI revealed T2/FLAIR signal hyperintensity in the right amygdala and hippocampus, as well as in the left caudate head on MRI-brain (

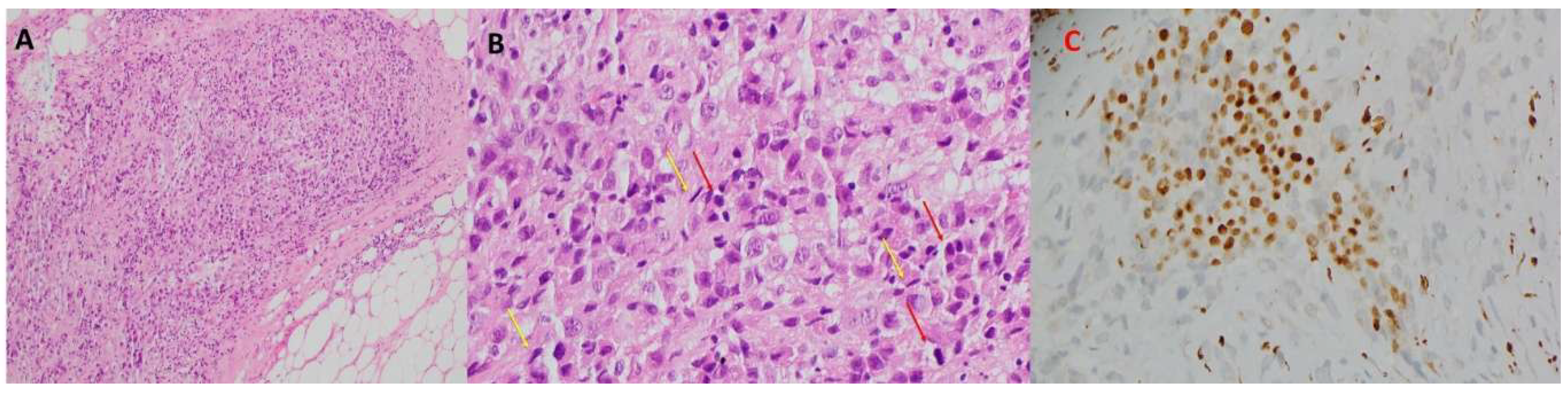

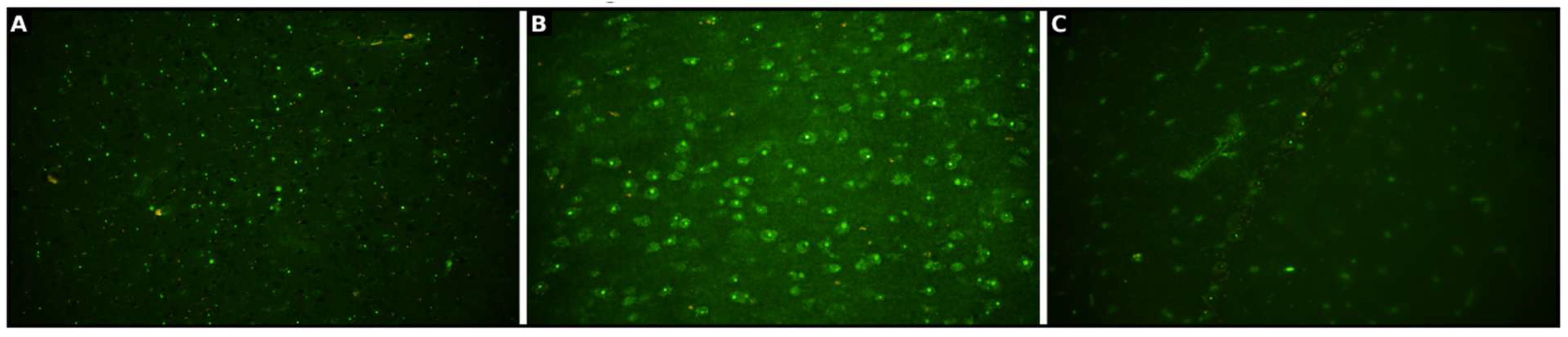

Figure 1). Both serum and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) analysis confirmed the presence of anti-Ma1/Ma2 antibodies (

Figure 2 and

Figure 3).

MRI of the spine demonstrated age-related degenerative changes without evidence of clinically correlating pathology such as cord compression, infarction, or transverse myelitis. MRI of the left brachial plexus showed no abnormalities to suggest brachial plexopathy.

Despite extensive radiological and serum biomarker investigations, including beta-hCG and testicular ultrasound, there were no indications of an underlying malignancy. A PET-CT scan demonstrated only mild and non-specific FDG uptake in the colon and right-sided pulmonary lymph nodes. However, there were no corresponding structural abnormalities on pan-CT that could be biopsied. These findings were discussed at the neuroradiology multidisciplinary team meeting. They were considered non-specific, not amenable to biopsy, and not characteristic of malignancy, given their discrete appearance and anatomically unrelated distribution across separate organ systems. Following the discovery of anti-Ma1/Ma2 antibodies, the patient was initiated on a three-day course of IV methylprednisolone pulse steroid (1g daily), which was subsequently followed by IVIG monthly, steroid-sparing therapy with mycophenolate, and a weaning dose of steroid, along with rituximab.

Background

Paraneoplastic neurological syndromes (PNS) are a group of rare, immune-mediated diseases that arise indirectly due to malignancy. They are believed to be the result of an adaptive immune response against onconeural antigens shared between the tumor and nervous system, with a resulting inflammatory cascade in the central and/or peripheral nervous system (Darnell & Posner, 2003; Graus & Dalmau, 2007). Among the well-characterised PNS antibodies, the anti-Ma family, comprising anti-Ma1 and anti-Ma2 (also known as anti-Ta), is noteworthy due to its heterogeneous clinical presentation and wide spectrum of associated malignancies (Dalmau & Rosenfeld, 2008; Gultekin et al., 2000).

Anti-Ma2 antibodies have been most commonly linked with testicular germ cell tumors in young and middle-aged men but have also been reported in association with lung, breast, gastrointestinal, and less commonly lymphoid neoplasms (Dalmau et al., 2004; Dalmau & Rosenfeld, 2008; Voltz, 2002). Anti-Ma1 antibodies, which may co-occur with anti-Ma2, are seen in a wide range of cancers and have been implicated in both limbic and extra-limbic autoimmune encephalitic processes (Pittock, Kryzer, & Lennon, 2004; Voltz, 2002).

Neurological presentation of anti-Ma1/Ma2 PNS is highly heterogeneous and includes limbic encephalitis, diencephalic and brainstem encephalitis, cerebellar degeneration, opsoclonus-myoclonus syndrome, movement disorders, and peripheral neuropathies (Höftberger, Rosenfeld, & Dalmau, 2015; Kunchok et al., 2022; Lancaster, 2017; Rees, 2004).

Recent epidemiological data indicate that approximately 1 in 300 cancer patients develop a paraneoplastic syndrome, yet their true incidence is likely underestimated because of diagnostic complexity and lack of detectable tumors malignancy at presentation the time of diagnosis (Graus et al., 2021). Clinical red flags for PNS include rapidly progressive neurological syndromes, a multifocal neurological process involving both central and peripheral nervous systems, and poor response to standard symptomatic or immunosuppressive therapy. The diagnostic workup generally includes a meticulous clinical evaluation, neuroimaging (typically MRI with contrast), cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) analysis, paraneoplastic antibody panel test, and comprehensive whole-body tumour screening using various imaging modalities, including PET, with biopsy performed when a suspicious lesion is identified. Additional serological tumour markers often complement imaging (Dalmau et al., 2004; Darnell & Posner, 2003; Graus et al., 2021; Titulaer et al., 2011).

Neuroimaging in anti-Ma1/Ma2 PNS most typically demonstrates bilateral or asymmetric T2-weighted and FLAIR sequence signal hyperintensities affecting the limbic system, diencephalon, and brainstem. These may be accompanied by mild atrophy and, less commonly, contrast enhancement (Höftberger et al., 2015; Linke, Schroeder, Helmberger, & Voltz, 2004). CSF analysis would typically reveal mild to moderate lymphocytic pleocytosis, elevated protein levels, an increased IgG index, and, in many cases, the presence of oligoclonal bands (Graus et al., 2004). Diagnosis is confirmed by detection of anti-Ma1/Ma2 antibodies in serum and/or CSF, but this must be interpreted in the context of concomitant clinical and imaging features, as false positives and cross-reactive antibodies have been reported (Archer, Panopoulou, Bhatt, Edey, & Giffin, 2014; Kunchok et al., 2022).

The search for a underlying malignancy should be thorough and investigated, as initial imaging is negative in a high percentage of cases. Fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography-computed tomography (FDG PET-CT) is far more sensitive for tumor detection compared to CT alone, with one series reporting up to 90% sensitivity for occult tumors in PNS (Tada et al., 2023; Titulaer et al., 2011).

Despite the use of advanced multimodal imaging, certain malignancies, particularly rare or indolent tumors, may evade early detection, highlighting the importance of ongoing periodic surveillance in seropositive patients with neurological symptoms consistent with probable PNS. The association between anti-Ma1/Ma2 PNS and malignant mesothelioma is exceedingly rare, with only a few well-documented case reports and small series available in the literature (Archer et al., 2014; Ortega Suero, Sola-Valls, Escudero, Saiz, & Graus, 2018; Vogrig et al., 2015).

In all reported cases, neurological symptoms emerged after the diagnosis of mesothelioma, sometimes by several months or even years. The pathophysiology in such instances has been thought to involve aberrant expression of onconeural antigens by mesothelial tumour cells, eliciting a systemic immune response with concurrent involvement of nervous system (Dalmau et al., 2007; Vogrig et al., 2015).

Discussion

This case underscores the rare association between anti-Ma1/Ma2 PNS and mesothelioma, emphasising the necessity for vigilant surveillance even if initial extensive screening for malignancy yielded no results. Only three similar cases have been reported to our knowledge, with mesothelioma diagnosis emerging usually after few months to years of clinic and radiological surveillance.

Three case studies have previously examined this association. In one case, PNS was diagnosed three years after the diagnosis of mesothelioma, with both CSF and serum testing positive for anti-Ma1 and Ma2 antibodies. In the other two cases PNS was diagnosed within a few months of mesothelioma detection (Archer et al., 2014; Tada et al., 2023; Vogrig et al., 2015).

The typical manifestations can include paraneoplastic cerebellar degeneration, opsoclonus-myoclonus and limbic encephalitis. Two clinical features shared by most paraneoplastic neurological syndromes are the rapid symptom progression and signs of inflammation in the CSF (Dalmau & Rosenfeld, 2008).

Recommended first-line investigations for malignancy include MRI with contrast, cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) analysis, and whole-body imaging using CT and PET-CT. Identifying an underlying malignancy remains central to management. While immunosuppressive therapies, such as corticosteroids, IVIG, or rituximab, may provide temporary clinical benefit, they are not considered definitive treatments. Optimising prognosis and minimising further neurological deterioration depend on timely detection and treatment of the underlying malignancy. Indeed, PNS typically respond poorly to immunosuppression alone, particularly when the primary tumour remains undiagnosed or untreated (Dalmau et al., 2004).

Given that no single investigation offers 100% sensitivity for malignancy detection, this case highlights the potential limitations of conventional imaging alone. In retrospect, the FDG-avid area in the right hilar region was initially interpreted as nonspecific, with no corresponding structural lesion visible; however, it may have reflected lymphadenopathy associated with mesothelial pathology. Although biopsy was not feasible at the time, this theoretical possibility reinforces the importance of incorporating PET-CT early in the diagnostic workup of seropositive PNS to identify a primary malignancy (Linke et al., 2004).

Anti-Ma1/Ma2 PNS often exhibit clinical features of diencephalitis, with brain MRI typically showing symmetrical T2/FLAIR hyperintensity of the diencephalon, medial thalami, midbrain, pons, and mesial temporal lobes. These unique MRI features should prompt clinicians to assess for paraneoplastic syndrome and possible underlying malignancy, especially when infectious causes, such as HSV, are excluded (Kunchok et al., 2022).

In our case, the patient did not develop cognitive impairment or seizure. However, he demonstrated opsoclonus, upper limb weakness, and imaging-confirmed encephalitic changes. Notably, opsoclonus later developed into vertical nystagmus, reflecting the brainstem involvement and evolving pathophysiology of PNS when untreated.

It is crucial to distinguish between Ma1 and Ma2 antibodies, as they do differ in their spectrum of tumour association and prognosis;anti-Ma2-associated PNS is often linked to testicular germ cell tumours and is thought to carry a relatively better prognosis compared to Anti-Ma1 or concurrent Ma1/Ma2 antibodies(Ortega Suero et al., 2018). Raising awareness among clinicians about PNS is vital, given 1 of 300 patients with cancer develop PNS.

Conclusion

This case highlights the importance of recognising mesothelioma as a potential, albeit rare, underlying malignancy responsible for triggering anti-Ma1/Ma2 paraneoplastic neurological syndromes (PNS), even when initial cancer screening yields negative results. Given the often limited and transient response of PNS to standard immunosuppressive therapy, early identification and treatment of the underlying malignancy is critical. This case also reinforces the need for ongoing, structured multimodal surveillance in seropositive patients presenting with neurological syndromes suggestive of PNS, as delayed tumour detection may adversely impact clinical outcomes.

Ethical Approval and Patient Consent

Written and verbal informed consent for publication of this case report and any accompanying images and data were obtained from the patient, using the Nepean Hospital Local Health District process and the BMJ Author Hub consent form. All potentially identifying information has been anonymized to protect the patient’s privacy. This case report was prepared in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, ICMJE, and COPE ethical standards. No experimental interventions were performed, and institutional review was not required as per local policy.

Funding

No funding was received for the preparation of this case report.

Acknowledgement

We would like to express our sincere gratitude to our colleagues from the NSW Pathology Service, particularly Janice Sideroudakis and Suzanne Culican (NSW Health Pathology scientists), for their valuable insights and for generously sharing the slides that significantly contributed to this research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Archer, H. A., Panopoulou, A., Bhatt, N., Edey, A. J., & Giffin, N. J. (2014). Mesothelioma and anti-Ma paraneoplastic syndrome; heterogeneity in immunogenic tumours increases. Pract Neurol, 14(1), 33-35. [CrossRef]

- Dalmau, J., Graus, F., Villarejo, A., Posner, J. B., Blumenthal, D., Thiessen, B.,... Rosenfeld, M. R. (2004). Clinical analysis of anti-Ma2-associated encephalitis. Brain, 127(Pt 8), 1831-1844. [CrossRef]

- Dalmau, J., & Rosenfeld, M. R. (2008). Paraneoplastic syndromes of the CNS. Lancet Neurol, 7(4), 327-340. [CrossRef]

- Dalmau, J., Tüzün, E., Wu, H. Y., Masjuan, J., Rossi, J. E., Voloschin, A.,... Lynch, D. R. (2007). Paraneoplastic anti-N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor encephalitis associated with ovarian teratoma. Ann Neurol, 61(1), 25-36. [CrossRef]

- Darnell, R. B., & Posner, J. B. (2003). Paraneoplastic syndromes involving the nervous system. N Engl J Med, 349(16), 1543-1554. [CrossRef]

- Graus, F., & Dalmau, J. (2007). Paraneoplastic neurological syndromes: diagnosis and treatment. Curr Opin Neurol, 20(6), 732-737. [CrossRef]

- Graus, F., Delattre, J. Y., Antoine, J. C., Dalmau, J., Giometto, B., Grisold, W.,... Voltz, R. (2004). Recommended diagnostic criteria for paraneoplastic neurological syndromes. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry, 75(8), 1135-1140. [CrossRef]

- Graus, F., Vogrig, A., Muñiz-Castrillo, S., Antoine, J. G., Desestret, V., Dubey, D.,... Honnorat, J. (2021). Updated Diagnostic Criteria for Paraneoplastic Neurologic Syndromes. Neurol Neuroimmunol Neuroinflamm, 8(4). [CrossRef]

- Gultekin, S. H., Rosenfeld, M. R., Voltz, R., Eichen, J., Posner, J. B., & Dalmau, J. (2000). Paraneoplastic limbic encephalitis: neurological symptoms, immunological findings and tumour association in 50 patients. Brain, 123 ( Pt 7), 1481-1494. [CrossRef]

- Höftberger, R., Rosenfeld, M. R., & Dalmau, J. (2015). Update on neurological paraneoplastic syndromes. Curr Opin Oncol, 27(6), 489-495. [CrossRef]

- Kunchok, A. C., Ontaneda, D., Lee, J., Rae-Grant, A., Foldvary-Schaefer, N., Cohen, J. A., & Jones, S. E. (2022). MRI Features of Anti-Ma1/Ma2 Paraneoplastic Neurologic Syndrome. Neurology, 99(20), 900-902. [CrossRef]

- Lancaster, E. (2017). Paraneoplastic Disorders. Continuum (Minneap Minn), 23(6, Neuro-oncology), 1653-1679. [CrossRef]

- Linke, R., Schroeder, M., Helmberger, T., & Voltz, R. (2004). Antibody-positive paraneoplastic neurologic syndromes: value of CT and PET for tumor diagnosis. Neurology, 63(2), 282-286. [CrossRef]

- Ortega Suero, G., Sola-Valls, N., Escudero, D., Saiz, A., & Graus, F. (2018). Anti-Ma and anti-Ma2-associated paraneoplastic neurological syndromes. Neurologia (Engl Ed), 33(1), 18-27. [CrossRef]

- Pittock, S. J., Kryzer, T. J., & Lennon, V. A. (2004). Paraneoplastic antibodies coexist and predict cancer, not neurological syndrome. Ann Neurol, 56(5), 715-719. [CrossRef]

- Rees, J. H. (2004). Paraneoplastic syndromes: when to suspect, how to confirm, and how to manage. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry, 75 Suppl 2(Suppl 2), ii43-50. [CrossRef]

- Tada, A., Kuribayashi, K., Kitajima, K., Nakamura, A., Yuki, M., Kanemura, S.,... Kijima, T. (2023). Sarcomatoid malignant pleural mesothelioma associated with anti-Ma2-related paraneoplastic neurological syndrome: A case report. Current Problems in Cancer: Case Reports, 11, 100244. [CrossRef]

- Titulaer, M. J., Soffietti, R., Dalmau, J., Gilhus, N. E., Giometto, B., Graus, F.,... Verschuuren, J. J. (2011). Screening for tumours in paraneoplastic syndromes: report of an EFNS task force. Eur J Neurol, 18(1), 19-e13. [CrossRef]

- Vogrig, A., Ferrari, S., Tinazzi, M., Manganotti, P., Vattemi, G., & Monaco, S. (2015). Anti-Ma-associated encephalomyeloradiculopathy in a patient with pleural mesothelioma. J Neurol Sci, 350(1-2), 105-106. [CrossRef]

- Voltz, R. (2002). Paraneoplastic neurological syndromes: an update on diagnosis, pathogenesis, and therapy. Lancet Neurol, 1(5), 294-305. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).