Submitted:

22 July 2025

Posted:

23 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

Historical Context: Slavery in Early New York

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. The Sample

2.2. Data Collection

2.3. Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ABG | African Burial Ground |

| DEM | Digital elevation model |

| GPR | Ground penetrating radar |

| 1 | The title of this article is also inspired by a Richard Wright haiku (Wright, 2011). |

| 2 | Take, for instance, the bioarchaeologist Aja Lans for a discussion of the dual role of the skeleton as both “object” and “subject” in bioarchaeological research (Lans, 2018). |

| 3 | Wall Street’s eponymous wall, for example, was constructed mainly by enslaved Africans under the ownership of the Dutch West India Company in 1653 (Moore, 2005). |

References

- Anderson, L. (2009). Update on the Schuyler Flatts Burial Ground. Legacy: The Magazine of the New York State Museum, 5(1). https://www.nysm.nysed.gov/research-collections/archaeology/bioarchaeology/research/schuyler-flatts-burial-ground.

- Brückner, M. (2021). Colonial Counter-Mappings and the Cartographic Reformation in Eighteenth-Century America. XVII-XVIII. Revue de La Société d’études Anglo-Américaines Des XVIIe et XVIIIe Siècles, 78, Article 78. [CrossRef]

- Buis, A. M. (2011). Dutch New York Between East & West: The World of Margrieta van Varick. Material Culture Review, 73, 68–77.

- Caratzas, M. D. (2023). Joseph Rodman Drake Park and Enslaved People’s Burial Ground (Designation Report LP-2674). New York City Landmarks Preservation Comission.

- Danylchak, E., & Cothran, J. R. (2018). Grave Landscapes: The Nineteenth-Century Rural Cemetery Movement. University of South Carolina Press. https://muse.jhu.edu/pub/244/monograph/book/57039.

- Diamond, J. E. (2006). Owned in Life, Owned in Death: The Pine Street African and African-American Burial Ground in Kingston, New York. Northeast Historical Archaeology, 35(1), 47–62. [CrossRef]

- Ember, C. R., & Ember, M. (2001). Cross-Cultural Research Methods. Bloomsbury Publishing PLC.

- FABG Remembrance and Redevelopment Task Force. (2021). Bedford-Church Community Engagement Report. New York City Department of Housing Preservation and Development. https://www.nyc.gov/assets/hpd/downloads/pdfs/services/bedford-church-report.pdf.

- Feller, L. J. (2022). Being Indigenous in Jim Crow Virginia: Powhatan People and the Color Line. University of Oklahoma Press. https://muse.jhu.edu/pub/350/oa_monograph/book/101132.

- Frohne, A. E. (2015). The African Burial Ground in New York City: Memory, Spirituality, and Space. Syracuse University Press.

- Goodman, A. H., Jones, J., Reid, J., Mack, M. E., Blakey, M. L., Amarasiriwardena, D., Burton, P., & Coleman, D. (2009). Isotopic and elemental chemistry of teeth: Implications for places of birth, forced migration patterns, nutritional status, and pollution. In M. L. Blakey & L. M. Rankin-Hill (Eds.), The Skeletal Biology of the New York African Burial Ground (Vol. 1, pp. 95–118). Howard University Press.

- Harris, L. M. (2003). Slavery in Colonial New York. In In the shadow of slavery: African Americans in New York City, 1626-1863 (pp. 11–47). Chicago : University of Chicago Press. http://archive.org/details/inshadowofslaver0000harr.

- Harris, L. M. (2004). Slavery, emancipation, and class formation in colonial and early national New York City. Journal of Urban History, 30(3), 339–359. [CrossRef]

- Hodges, G. R. G. (2005). Root and Branch: African Americans in New York and East Jersey, 1613-1863. Univ of North Carolina Press.

- Jackson, F. L., Mayes, A., Mack, M. E., Froment, A., Keita, S. O., Kittles, R. A., George, M., Shujaa, K. J., Blakey, M. L., & Rankin-Hill, L. M. (2009). Origins of the New York African Burial Ground population: Biological evidence of geographical and macroethnic affiliations using craniometric, dental morphology, and preliminary genetic analyses. In M. L. Blakey & L. M. Rankin-Hill (Eds.), The Skeletal Biology of the New York African Burial Ground (Vol. 1, pp. 69–94). Howard University Press.

- Jacobs, J. (2023). The First Arrival of Enslaved Africans in New Amsterdam. New York History, 104(1), 96–114.

- Janzen, J. M. (2017). African Religion and Healing in the Atlantic Diaspora. Oxford Research Encyclopedia of African History, 44–65. [CrossRef]

- Kearns, B., & Schneiderman-Fox, F. (2000). Stage 1A Archaeological Assessment, Bath Rivka School, Flatbush, Brooklyn, New York (Archaeological Report 857). New York City Landmarks Preservation Comission. http://s-media.nyc.gov/agencies/lpc/arch_reports/857.pdf.

- Lans, A. (2018). “Whatever Was Once Associated with him, Continues to Bear his Stamp”: Articulating and Dissecting George S. Huntington and His Anatomical Collection. In P. K. Stone (Ed.), Bioarchaeological Analyses and Bodies: New Ways of Knowing Anatomical and Archaeological Skeletal Collections (pp. 11–26). Springer International Publishing. [CrossRef]

- Laterman, K. (2019, June 14). This Empty Lot Is Worth Millions. It’s Also an African-American Burial Ground. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2019/06/14/nyregion/african-american-burial-ground-queens-newtown.html.

- Leach, O. (2020, August 20). Historic African American Cemetery in Montgomery to be Restored. Spectrum News. https://spectrumlocalnews.com/nys/hudson-valley/news/2020/08/20/town-of-montgomery-establishes-committee-to-revitalize-historic-african-american-cemetery.

- Lee, E. J., Anderson, L. M., Dale, V., & Merriwether, D. A. (2009). MtDNA origins of an enslaved labor force from the 18th century Schuyler Flatts Burial Ground in colonial Albany, NY: Africans, Native Americans, and Malagasy? Journal of Archaeological Science, 36(12), 2805–2810. [CrossRef]

- Leitner, J. (2016). Transitions in the Colonial Hudson Valley: Capitalist, Bulk Goods, and Braudelian. Journal of World - Systems Research, 22(1), 214–246. [CrossRef]

- Lepore, J. (2005). The tightening vise: Slavery and freedom in British New York. In I. Berlin & L. M. Harris (Eds.), Slavery in New York (pp. 57–90). The New Press.

- MacLean, J. S., Conyers, L., & Ottman, S. M. (2017). Hunts Point Burial Ground, Drake Park, Bronx, New York (Phase 1A Documentary Study and Ground Penetrating Radar Survey 1744).

- Maika, D. J. (2020). To “experiment with a parcel of negros.” https://doi.org/10.1163/18770703-01001005.

- Matthews, C. N. (2020). Urban Erasures: Historical and Contemporary Archaeologies. Journal for the Anthropology of North America, 23(1), 4–11. [CrossRef]

- Moore, C. P. (2005). A World of Possibilities: Slavery and Freedom in Dutch New Amsterdam. In I. Berlin & L. M. Harris (Eds.), Slavery in New York (pp. 29–55). The New Press.

- Mosterman, A. C. (2021). Spaces of enslavement: A history of slavery and resistance in Dutch New York. Cornell University Press.

- New York Genealogical & Biographical Society. (1982). Kingston, New York, Old Dutch Church: Burials 1810–1815. NYG&B Record, 113. https://www.newyorkfamilyhistory.org/online-records/nygb-record/566-568/9.

- Pappalardo, A. M., & Meade, E. D. (2016). Phase 1B Archaeological Investigation, 126th Street Bus Depot: Block 1803, Lot 1, East Harlem, New York, New York (Phase 1B Archaeological Investigation 15PR02521; p. 156). New York City Economic Development Corp.

- Pearce, S. C., & Lee, R. (2021). Missing Colonies in American Myths of Slavery: Where Is the “Deep North” in Sociology Textbooks? Sociology of Race and Ethnicity, 7(4), 579–593. [CrossRef]

- Radburn, N. (2023). Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade Database. Slave Voyages. https://www.slavevoyages.org/voyage/database.

- Rothschild, N. A., Sutphin, A., Bankoff, H. A., & MacLean, J. S. (2022). Buried Beneath the City: An Archaeological History of New York. Columbia University Press. [CrossRef]

- Sandy, W. (2024). Archaeology of the Montgomery “Colored” Cemetery (p. 6). Walden Juneteenth Celebration.

- Sanjek, R. (2000). The Future of Us All: Race and Neighborhood Politics in New York City. Cornell University Press.

- Schneiderman-Fox, F., Crist, T., Dickinson, N., Kearns, B., Mascia, S., & Saunders, C. (2001). Stage 1B Archaeological Investigation, P.S. 325-K, Church and Bedfor Avenues, Brooklyn, New York (Archaeological Report 858). New York City Landmarks Preservation Comission.

- Seyfried, M., Chandler, D., & Marks, D. (2011). Long-Term Soil Water Trends across a 1000-m Elevation Gradient. Vadose Zone Journal, 10(4), 1276–1286. [CrossRef]

- Sharples, J. T. (2020). The World That Fear Made: Slave Revolts and Conspiracy Scares in Early America. University of Pennsylvania Press.

- SSURGO Staff, U. (2025). SSURGO [Dataset]. https://websoilsurvey.sc.egov.usda.gov/App/HomePage.htm.

- Stanne, S. P., Panetta, R. G., Forist, B. E., & Niemisto, M. L. (2021). The Hudson: An Illustrated Guide to the Living River (Third). Rutgers University Press. [CrossRef]

- Starr, P. (2023). The Re-Emergence of “People of Color.” Du Bois Review: Social Science Research on Race, 20(1), 1–20. [CrossRef]

- Stiles, H. (2012). History of the City of Brooklyn. Applewood Books.

- The New York City Council - File #: Int 1051-2024, Int No 1051-2024, New York City Council (2024). https://legistar.council.nyc.gov/LegislationDetail.aspx?ID=6874636&GUID=8C163699-6A3D-4733-BB10-90F7118DB2BD&Options=&Search=.

- Tilton, E. (1910). The Reformed Low Dutch Church of Harlem, Organized 1660: Historical Sketch. Consistory.

- U.S. General Services Administration. (1993). New York African Burial Ground (p. 43) [National Register of Historic Places Registration Form]. National Park Serice / General Services Administration. https://npgallery.nps.gov/GetAsset/bd7edd66-f641-4d5f-b0ac-e92077fef27f.

- Wescott, D. J. (2018). Recent advances in forensic anthropology: Decomposition research. Forensic Sciences Research, 3(4), 327–342. [CrossRef]

- White, S. (1995). Slavery in New York State in the Early Republic. Australasian Journal of American Studies, 14(2), 1–29.

- White, S. (2012). Somewhat More Independent: The End of Slavery in New York City, 1770-1810. University of Georgia Press.

- Williams, R. L. (1999). Montgomery, New York. Arcadia Publishing.

- Woods, L. (2019, February 18). Kingston groups hurrying to buy site of 250-year-old African-American cemetery—Hudson Valley One. https://hudsonvalleyone.com/2019/02/18/kingston-groups-hurrying-to-buy-site-of-250-year-old-african-american-cemetery/.

- Wright, R. (2011). Haiku: This Other World. Skyhorse Publishing Company, Incorporated.

- Zoran. (2020, May 1). Visibility index (total viewshed) for QGIS. Landscape Archaeology. https://landscapearchaeology.org/2020/visibility-index/.

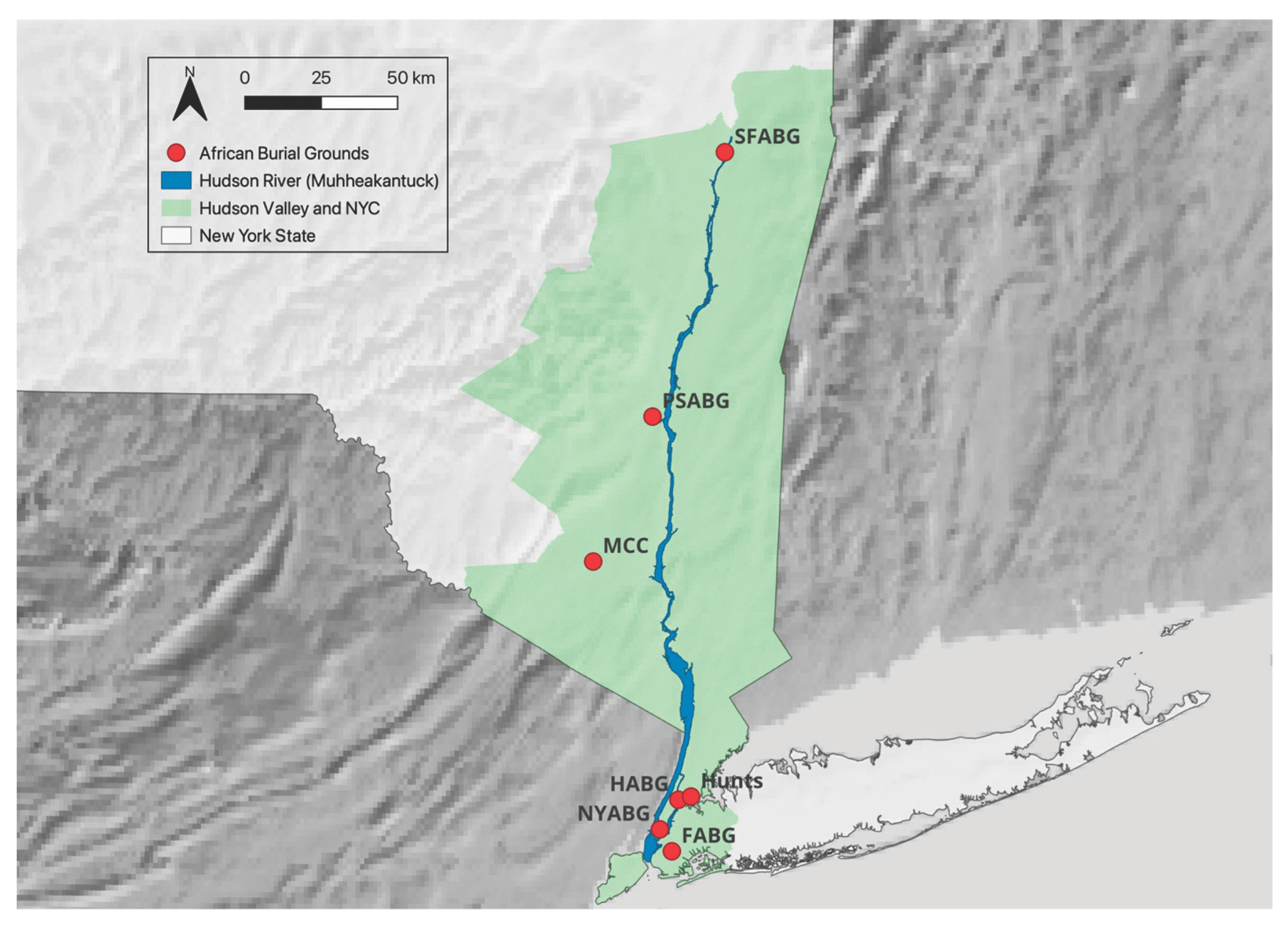

| Site | Estimated Date of First Interment | Location | State of Archaeological Preservation |

Legal Protections |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Flatbush African Burial Ground (FABG) |

1780s | Kings County (Brooklyn) |

Disturbed (some excavation) |

None |

| Harlem African Burial Ground (HABG) | 1660s | East Harlem | Disturbed (some excavation) |

None |

| Hunts Point Enslaved African Burial Ground |

1729 | The Bronx | Disturbed (not excavated) | None |

| Montgomery “Colored Cemetery” (MCC) |

1756 | Orange County | Undisturbed (surveyed but not excavated) | National Register of Historic Places |

| New York African Burial Ground (NYABG) |

1690s | Lower Manhattan |

Excavated (salvage excavation) |

National monument |

| Pine Street African Burial Ground (PSABG) |

1660s* | Ulster County | Largely undisturbed (unexcavated) |

Land trust (conservation easement) |

| Schuyler Flatts African Burial Ground (SFABG) |

1690s* | Albany County | Excavated (salvage excavation) |

None |

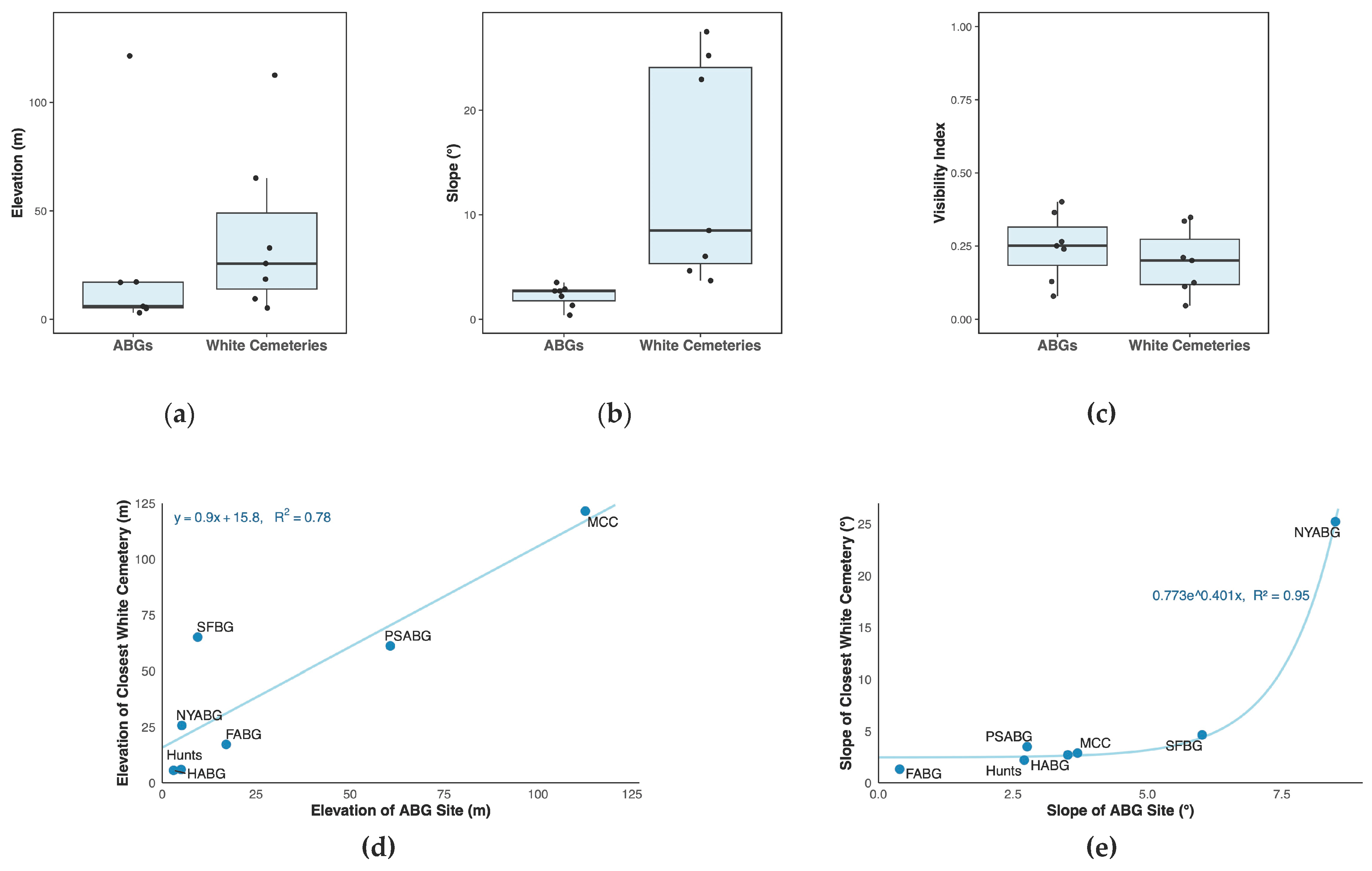

| Site | Mean Elevation (masl) | Mean Slope (°) | Mean Visibility Index (0 ≤ x̄ ≤ 1) |

AWS to 150 cm Depth (cm3) | Mean Annual Precipitation (mm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FABG (Nearest white cemetery) |

17.2 (113) |

1.33 (3.70) |

0.365 (0.211) |

7.07 (7.07) |

1196 (1196) |

| HABG (Nearest white cemetery) |

17.0 (25.7) |

0.393 (25.2) |

0.129 (0.125) |

4.92 (7.07) |

1196 (1196) |

| Hunts Point ABG (Nearest white cemetery) |

5.57 (18.5) |

2.71 (23.0) |

0.240 (0.348) |

0.81 (9.38) |

1196 (1196) |

| MCC (Nearest white cemetery) |

3.00 (32.9) |

3.52 (27.5) |

0.251 (0.201) |

31.6 (10.33) |

1080 (1168) |

| NYABG (Nearest white cemetery) |

6.00 (5.20) |

2.20 (8.49) |

0.0788 (0.0463) |

4.92 (4.92) |

1196 (1196) |

| PSABG (Nearest white cemetery) |

5.00 (65.10) |

2.71 (4.64) |

0.401 (0.335) |

14.46 (14.46) |

1168 (1168) |

| SFABG (Nearest white cemetery) |

121 (9.44) |

2.88 (6.01) |

0.265 (0.112) |

13.7 (24.33) |

965 (965) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).