Submitted:

23 July 2025

Posted:

23 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Mechanism of Varicella Zoster Virus (VZV) Infection

Genes for Latent Infection

Immune Response to Varicella Zoster Virus (VZV)

Attenuated Live Vaccine Against Varicella Zoster Virus (VZV)

Are Varicella Vaccinees Infectious?

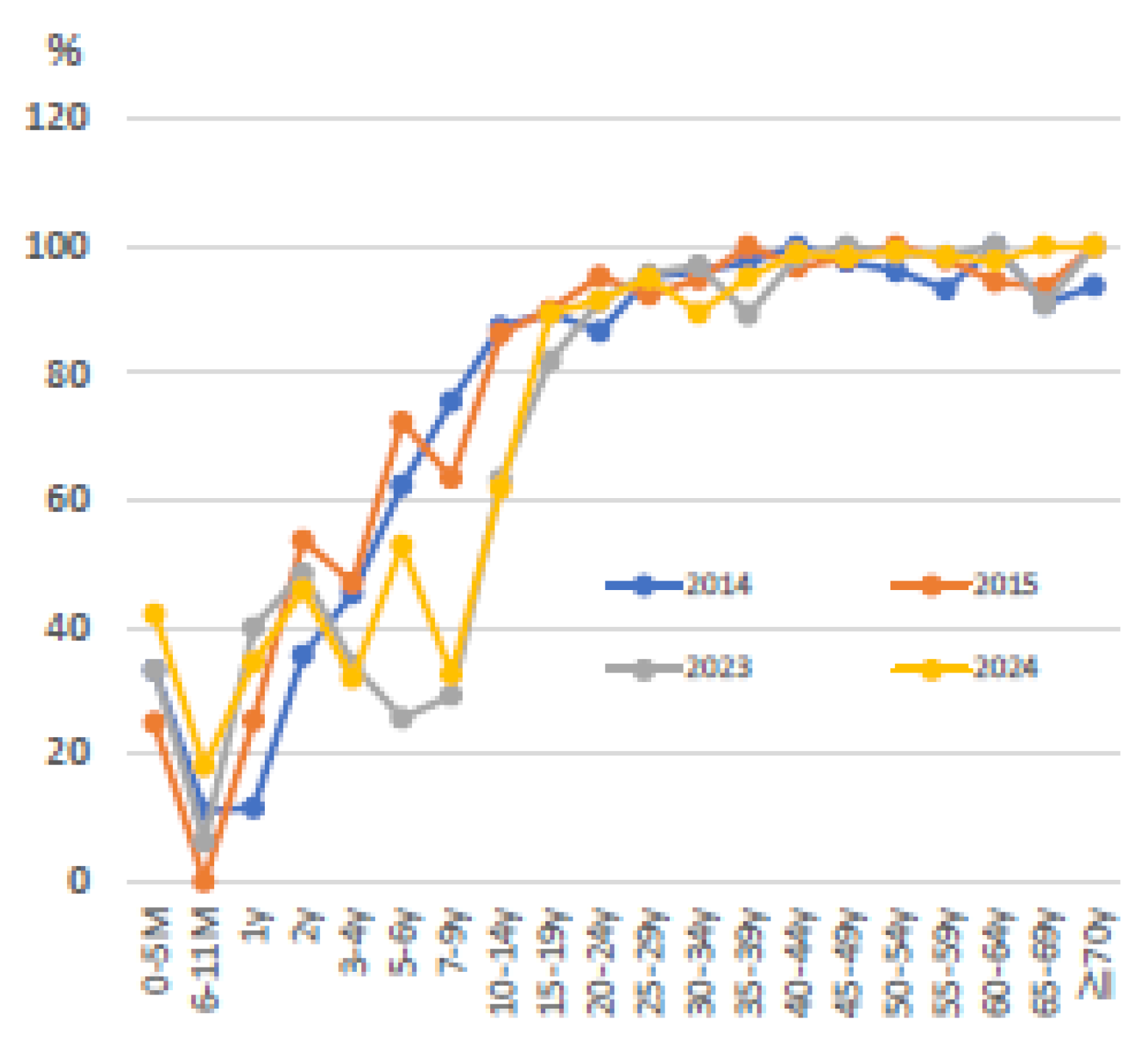

Efficacy of Attenuated Live Varicella Vaccine in Preventing Chickenpox

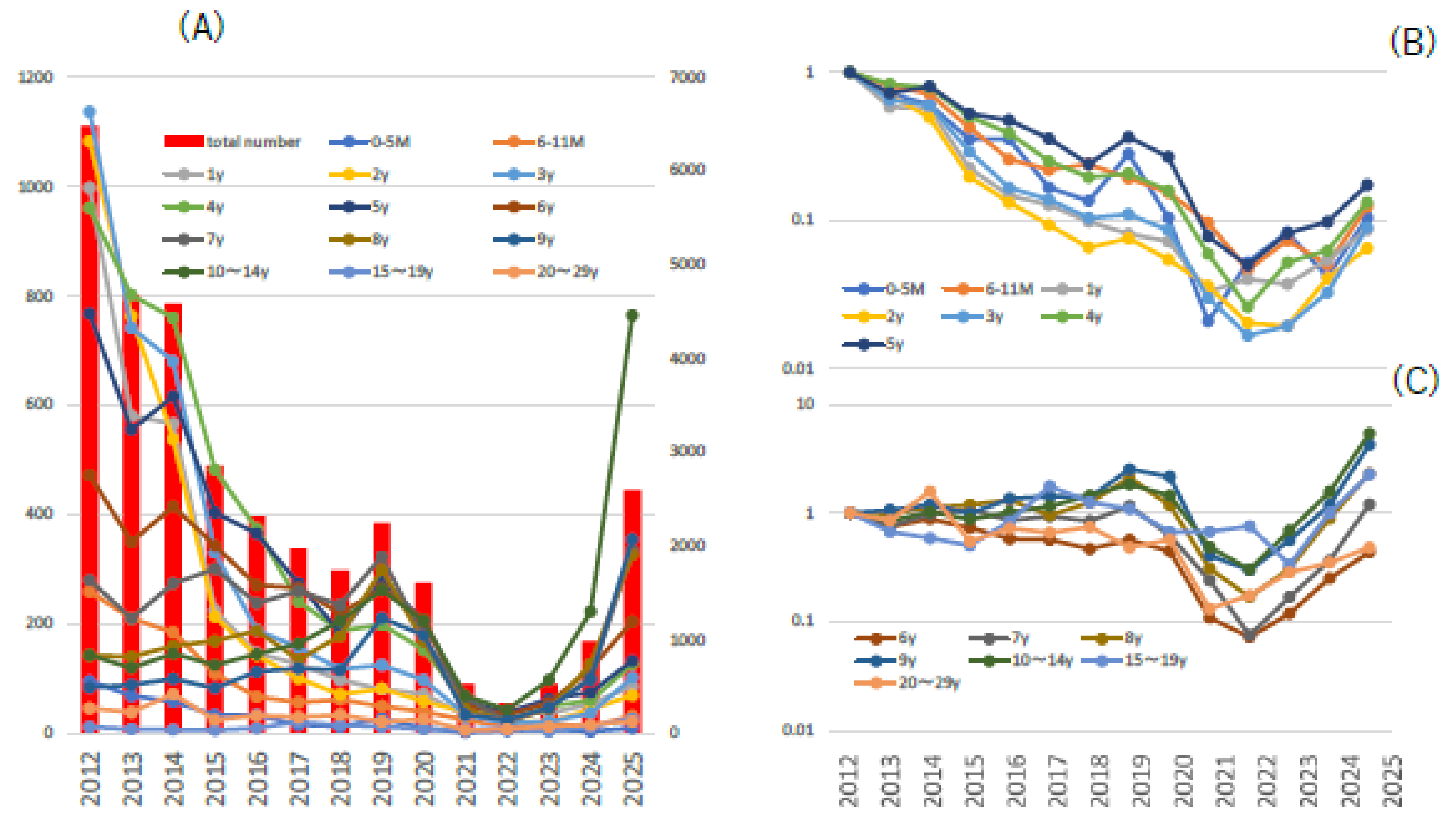

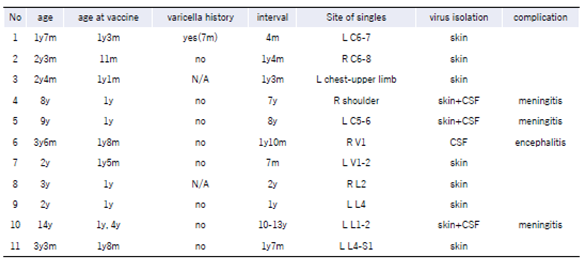

Childhood Shingles

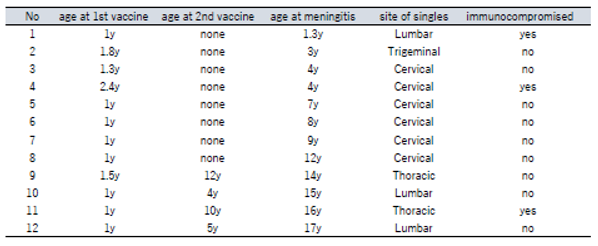

Meningitis Due to Reactivation of Varicella Virus

Maintenance of Immunity to VZV

Problems and Future Challenges with Varicella Attenuated Live Vaccine

<Breakthrough Infection>

<Persistence of Immunity>

<Trends In Shingles Caused by Vaccine Strains>

<Emergence of Mutant Vaccine Strains>

Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Weller TH. Serial propagation in vitro of agents producing inclusion bodies derived from varicella and herpes zoster. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med 1953;83:340-6. [CrossRef]

- Ligon BL. Thomas Huckle Weller MD: Nobel Laureate and research pioneer in poliomyelitis, varicella-zoster virus, cytomegalovirus, rubella, and other infectious diseases. Semin Pediatr Infect Dis 2002;13:55-63.

- Cohen R, Ashman M, Taha MK, Varon E, Angoulvant F, Levy C, Rybak A, Ouldali N, Guiso N, Grimprel E. Pediatric Infectious Disease Group (GPIP) position paper on the immune debt of the COVID-19 pandemic in childhood, how can we fill the immunity gap? Infect Dis Now 2021;51:418-23. [CrossRef]

- Principi N, Autore G, Ramundo G, Esposito S. Epidemiology of Respiratory Infections during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Viruses 2023;15:1160. [CrossRef]

- Yang MC, Su YT, Chen PH, Tsai CC, Lin TI, Wu JR. Changing patterns of infectious diseases in children during the COVID-19 pandemic. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 2023;13:1200617. [CrossRef]

- Nagasawa M. Verification of Immune Debts in Children Caused by the COVID-19 Pandemic from an Epidemiological and Clinical Perspective. Immuno 2025;5:5. [CrossRef]

- https://survey.tmiph.metro.tokyo.lg.jp/epidinfo/epimenu.do. accessed on June 8, 2025.

- Soong W, Schultz JC, Patera AC, Sommer MH, Cohen JI. Infection of human T lymphocytes with varicella-zoster virus: an analysis with viral mutants and clinical isolates. J Virol 2000;74:1864-70.

- Ku CC, Padilla JA, Grose C, Butcher EC, Arvin AM. Tropism of varicella-zoster virus for human tonsillar CD4(+) T lymphocytes that express activation, memory, and skin homing markers. J Virol 2002;76:11425-33.

- Abendroth A, Morrow G, Cunningham AL, Slobedman B. Varicella-zoster virus infection of human dendritic cells and transmission to T cells: implications for virus dissemination in the host. J Virol 2001;75:6183-92.

- Ku CC, Zerboni L, Ito H, Graham BS, Wallace M, Arvin AM. Varicella-zoster virus transfer to skin by T Cells and modulation of viral replication by epidermal cell interferon-alpha. J Exp Med 2004;200:917-25. [CrossRef]

- Levin MJ, Cai GY, Manchak MD, Pizer LI. Varicella-zoster virus DNA in cells isolated from human trigeminal ganglia. J Virol 2003;77:6979-87. [CrossRef]

- Annunziato PW, Lungu O, Panagiotidis C, Zhang JH, Silvers DN, Gershon AA, Silverstein SJ. Varicella-zoster virus proteins in skin lesions: implications for a novel role of ORF29p in chickenpox. J Virol 2000;74:2005-10. [CrossRef]

- Nikkels AF, Debrus S, Sadzot-Delvaux C, Piette J, Rentier B, Pierard GE. Localization of varicella-zoster virus nucleic acids and proteins in human skin. Neurology 1995;45:S47-S9.

- Weigle KA, Grose C. Common expression of varicella-zoster viral glycoprotein antigens in vitro and in chickenpox and zoster vesicles. J Infect Dis 1983;148:630-8. [CrossRef]

- Cole NL, Grose C. Membrane fusion mediated by herpesvirus glycoproteins: the paradigm of varicella-zoster virus. Rev Med Virol 2003;13:207-22.

- Chen JJ, Zhu Z, Gershon AA, Gershon MD. Mannose 6-phosphate receptor dependence of varicella zoster virus infection in vitro and in the epidermis during varicella and zoster. Cell 2004;119:915-26. [CrossRef]

- Li Q, Ali MA, Cohen JI. Insulin degrading enzyme is a cellular receptor mediating varicella-zoster virus infection and cell-to-cell spread. Cell 2006;127:305-16.

- Suenaga T, Satoh T, Somboonthum P, Kawaguchi Y, Mori Y, Arase H. Myelin-associated glycoprotein mediates membrane fusion and entry of neurotropic herpesviruses. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2010;107:866-71. [CrossRef]

- Quarles RH. A hypothesis about the relationship of myelin-associated glycoprotein’s function in myelinated axons to its capacity to inhibit neurite outgrowth. Neurochem Res 2009;34:79-86.

- Cohrs RJ, Barbour M, Gilden DH. Varicella-zoster virus (VZV) transcription during latency in human ganglia: detection of transcripts mapping to genes 21, 29, 62, and 63 in a cDNA library enriched for VZV RNA. J Virol 1996;70:2789-96. [CrossRef]

- Kennedy PG, Grinfeld E, Bell JE. Varicella-zoster virus gene expression in latently infected and explanted human ganglia. J Virol 2000;74:11893-8.

- Cohen JI, Krogmann T, Ross JP, Pesnicak L, Prikhod’ko EA. Varicella-zoster virus ORF4 latency-associated protein is important for establishment of latency. J Virol 2005;79:6969-75. [CrossRef]

- Xia D, Srinivas S, Sato H, Pesnicak L, Straus SE, Cohen JI. Varicella-zoster virus open reading frame 21, which is expressed during latency, is essential for virus replication but dispensable for establishment of latency. J Virol 2003;77:1211-8.

- Cohen JI, Krogmann T, Pesnicak L, Ali MA. Absence or overexpression of the Varicella-Zoster Virus (VZV) ORF29 latency-associated protein impairs late gene expression and reduces VZV latency in a rodent model. J Virol 2007;81:1586-91. [CrossRef]

- Cohen JI, Krogmann T, Bontems S, Sadzot-Delvaux C, Pesnicak L. Regions of the varicella-zoster virus open reading frame 63 latency-associated protein important for replication in vitro are also critical for efficient establishment of latency. J Virol 2005;79:5069-77.

- Depledge DP, Ouwendijk WJD, Sadaoka T, Braspenning SE, Mori Y, Cohrs RJ, Verjans G, Breuer J. A spliced latency-associated VZV transcript maps antisense to the viral transactivator gene 61. Nat Commun 2018;9:1167. [CrossRef]

- Balachandra K, Thawaranantha D, Ayuthaya PI, Bhumisawasdi J, Shiraki K, Yamanishi K. Effects of human alpha, beta and gamma interferons on varicella zoster virus in vitro. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health 1994;25:252-7.

- Desloges N, Rahaus M, Wolff MH. Role of the protein kinase PKR in the inhibition of varicella-zoster virus replication by beta interferon and gamma interferon. J Gen Virol 2005;86:1-6.

- Arvin AM, Kushner JH, Feldman S, Baehner RL, Hammond D, Merigan TC. Human leukocyte interferon for the treatment of varicella in children with cancer. N Engl J Med 1982;306:761-5. [CrossRef]

- Arvin AM, Koropchak CM, Williams BR, Grumet FC, Foung SK. Early immune response in healthy and immunocompromised subjects with primary varicella-zoster virus infection. J Infect Dis 1986;154:422-9.

- Kumagai T, Chiba Y, Wataya Y, Hanazono H, Chiba S, Nakao T. Development and characteristics of the cellular immune response to infection with varicella-zoster virus. J Infect Dis 1980;141:7-13. [CrossRef]

- Burke BL, Steele RW, Beard OW, Wood JS, Cain TD, Marmer DJ. Immune responses to varicella-zoster in the aged. Arch Intern Med 1982;142:291-3.

- Oxman MN, Levin MJ. Vaccination against Herpes Zoster and Postherpetic Neuralgia. J Infect Dis 2008;197 Suppl 2:S228-36.

- Takahashi M, Otsuka T, Okuno Y, Asano Y, Yazaki T. Live vaccine used to prevent the spread of varicella in children in hospital. Lancet 1974;2:1288-90.

- Gomi Y, Sunamachi H, Mori Y, Nagaike K, Takahashi M, Yamanishi K. Comparison of the complete DNA sequences of the Oka varicella vaccine and its parental virus. J Virol 2002;76:11447-59. [CrossRef]

- Gutzeit C, Raftery MJ, Peiser M, Tischer KB, Ulrich M, Eberhardt M, Stockfleth E, Giese T, Sauerbrei A, Morita CT, et al. Identification of an important immunological difference between virulent varicella-zoster virus and its avirulent vaccine: viral disruption of dendritic cell instruction. J Immunol 2010;185:488-97.

- Moffat JF, Stein MD, Kaneshima H, Arvin AM. Tropism of varicella-zoster virus for human CD4+ and CD8+ T lymphocytes and epidermal cells in SCID-hu mice. J Virol 1995;69:5236-42. [CrossRef]

- Moffat JF, Zerboni L, Kinchington PR, Grose C, Kaneshima H, Arvin AM. Attenuation of the vaccine Oka strain of varicella-zoster virus and role of glycoprotein C in alphaherpesvirus virulence demonstrated in the SCID-hu mouse. J Virol 1998;72:965-74.

- Gomi Y, Imagawa T, Takahashi M, Yamanishi K. Oka varicella vaccine is distinguishable from its parental virus in DNA sequence of open reading frame 62 and its transactivation activity. J Med Virol 2000;61:497-503.

- Zerboni L, Hinchliffe S, Sommer MH, Ito H, Besser J, Stamatis S, Cheng J, Distefano D, Kraiouchkine N, Shaw A, et al. Analysis of varicella zoster virus attenuation by evaluation of chimeric parent Oka/vaccine Oka recombinant viruses in skin xenografts in the SCIDhu mouse model. Virology 2005;332:337-46.

- Weibel RE, Neff BJ, Kuter BJ, Guess HA, Rothenberger CA, Fitzgerald AJ, Connor KA, McLean AA, Hilleman MR, Buynak EB, et al. Live attenuated varicella virus vaccine. Efficacy trial in healthy children. N Engl J Med 1984;310:1409-15. [CrossRef]

- Marin M, Leung J, Gershon AA. Transmission of Vaccine-Strain Varicella-Zoster Virus: A Systematic Review. Pediatrics 2019;144(3):e20191305.

- Gershon AA, LaRussa P, Steinberg S. The varicella vaccine. Clinical trials in immunocompromised individuals. Infect Dis Clin North Am 1996;10:583-94. [CrossRef]

- Willis ED, Woodward M, Brown E, Popmihajlov Z, Saddier P, Annunziato PW, Halsey NA, Gershon AA. Herpes zoster vaccine live: A 10 year review of post-marketing safety experience. Vaccine 2017;35:7231-9.

- Bollaerts K, Riera-Montes M, Heininger U, Hens N, Souverain A, Verstraeten T, Hartwig S. A systematic review of varicella seroprevalence in European countries before universal childhood immunization: deriving incidence from seroprevalence data. Epidemiol Infect 2017;145:2666-77.

- Saito M, Haruyama C, Ohba H, Wada A, Takeuchi Y. [A seroepidemiological study of varicella]. Kansenshogaku Zasshi 1987;61:783-8.

- Varis T, Vesikari T. Efficacy of high-titer live attenuated varicella vaccine in healthy young children. J Infect Dis 1996;174 Suppl 3:S330-4. [CrossRef]

- Gershon AA, Steinberg SP, LaRussa P, Ferrara A, Hammerschlag M, Gelb L. Immunization of healthy adults with live attenuated varicella vaccine. J Infect Dis 1988;158:132-7.

- Shapiro ED, Vazquez M, Esposito D, Holabird N, Steinberg SP, Dziura J, LaRussa PS, Gershon AA. Effectiveness of 2 doses of varicella vaccine in children. J Infect Dis 2011;203:312-5.

- Gershon AA, Gershon MD, Shapiro ED. Live Attenuated Varicella Vaccine: Prevention of Varicella and of Zoster. J Infect Dis 2021;224:S387-S97. [CrossRef]

- Uda K, Okubo Y, Tsuge M, Tsukahara H, Miyairi I. Impacts of routine varicella vaccination program and COVID-19 pandemic on varicella and herpes zoster incidence and health resource use among children in Japan. Vaccine 2023;41:4958-66.

- Guess HA, Broughton DD, Melton LJ, 3rd, Kurland LT. Epidemiology of herpes zoster in children and adolescents: a population-based study. Pediatrics 1985;76:512-7.

- Baba K, Yabuuchi H, Takahashi M, Ogra PL. Increased incidence of herpes zoster in normal children infected with varicella zoster virus during infancy: community-based follow-up study. J Pediatr 1986;108:372-7. [CrossRef]

- Terada K, Kawano S, Yoshihiro K, Miyashima H, Morita T. Characteristics of herpes zoster in otherwise normal children. Pediatr Infect Dis J 1993;12:960-1.

- Lin HC, Chao YH, Wu KH, Yen TY, Hsu YL, Hsieh TH, Wei HM, Wu JL, Muo CH, Hwang KP, et al. Increased risk of herpes zoster in children with cancer: A nationwide population-based cohort study. Medicine (Baltimore) 2016;95:e4037.

- Leung AK, Robson WL, Leong AG. Herpes zoster in childhood. J Pediatr Health Care 2006;20:300-3.

- Weinmann S, Chun C, Schmid DS, Roberts M, Vandermeer M, Riedlinger K, Bialek SR, Marin M. Incidence and clinical characteristics of herpes zoster among children in the varicella vaccine era, 2005-2009. J Infect Dis 2013;208:1859-68. [CrossRef]

- Harpaz R, Leung JW. The Epidemiology of Herpes Zoster in the United States During the Era of Varicella and Herpes Zoster Vaccines: Changing Patterns Among Children. Clin Infect Dis 2019;69:345-7.

- Terada K, Wakabayashi S, Ono S, Tanaka Y, Kato A, Teranishi H, Miyata I, Ogita S, Oishi T, Ohno N, et al. Characteristics of zoster in otherwise healthy children‒ a comparative study between 55 zoster patients between 1990 and 2000.

- (11 years) and 56 from 2001 to 2017 (17 years) ‒. Pediatric Infectious Immunity 2019;31:3-6.

- Shang BS, Hung CJ, Lue KH. Herpes Zoster in an Immunocompetent Child without a History of Varicella. Pediatr Rep 2021;13:162-7.

- Ishikawa H, Tamai K, Mibou K, Tunoda T, Sawamura D, Umeki K, Sugawara T, Yajima H, Sasaki C, Kumano T, et al. A multicenter, joint annual statistical analysis of herpes zoster (April 2000-March 2001). The Japanese Journal of Dermatology 2003;113:1229-39.

- Takahashi M, Baba K, Horiuchi K, Kamiya H, Asano Y. A live varicella vaccine. Adv Exp Med Biol 1990;278:49-58.

- Hardy I, Gershon AA, Steinberg SP, LaRussa P. The incidence of zoster after immunization with live attenuated varicella vaccine. A study in children with leukemia. Varicella Vaccine Collaborative Study Group. N Engl J Med 1991;325:1545-50. [CrossRef]

- Galea SA, Sweet A, Beninger P, Steinberg SP, Larussa PS, Gershon AA, Sharrar RG. The safety profile of varicella vaccine: a 10-year review. J Infect Dis 2008;197 Suppl 2:S165-9.

- Goulleret N, Mauvisseau E, Essevaz-Roulet M, Quinlivan M, Breuer J. Safety profile of live varicella virus vaccine (Oka/Merck): five-year results of the European Varicella Zoster Virus Identification Program (EU VZVIP). Vaccine 2010;28:5878-82.

- Yoshikawa T, Ando Y, Nakagawa T, Gomi Y. Safety profile of the varicella vaccine (Oka vaccine strain) based on reported cases from 2005 to 2015 in Japan. Vaccine 2016;34:4943-7. [CrossRef]

- Petursson G, Helgason S, Gudmundsson S, Sigurdsson JA. Herpes zoster in children and adolescents. Pediatr Infect Dis J 1998;17:905-8.

- Amaral V, Shi JZ, Tsang AM, Chiu SS. Primary varicella zoster infection compared to varicella vaccine reactivation associated meningitis in immunocompetent children. J Paediatr Child Health 2021;57:19-25.

- Barry R, Prentice M, Costello D, O’Mahony O, DeGascun C, Felsenstein S. Varicella Zoster Reactivation Causing Aseptic Meningitis in Healthy Adolescents: A Case Series And Review Of The Literature. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2020;39:e278-e82.

- Kawamura Y, Suzuki D, Kono T, Miura H, Kozawa K, Mizuno H, Yoshikawa T. A Case of Aseptic Meningitis Without Skin Rash Caused by Oka Varicella Vaccine. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2022;41:78-9. [CrossRef]

- Heusel EH, Grose C. Twelve Children with Varicella Vaccine Meningitis: Neuropathogenesis of Reactivated Live Attenuated Varicella Vaccine Virus. Viruses 2020;12(10):1078.

- https://id-info.jihs.go.jp/surveillance/nesvpd/graph/YearComparison/vzv2024/2024/20250602154218.html. accessed on June 8, 2025.

- https://www.mhlw.go.jp/topics/bcg/other/5.html. accessed on June 8, 2025.

- Gershon AA, LaRussa P, Steinberg S, Mervish N, Lo SH, Meier P. The protective effect of immunologic boosting against zoster: an analysis in leukemic children who were vaccinated against chickenpox. J Infect Dis 1996;173:450-3. [CrossRef]

- Hope-Simpson RE. THE NATURE OF HERPES ZOSTER: A LONG-TERM STUDY AND A NEW HYPOTHESIS. Proc R Soc Med 1965;58:9-20.

- Mehta SK, Cohrs RJ, Forghani B, Zerbe G, Gilden DH, Pierson DL. Stress-induced subclinical reactivation of varicella zoster virus in astronauts. J Med Virol 2004;72:174-9.

- White CJ. Clinical trials of varicella vaccine in healthy children. Infect Dis Clin North Am 1996;10:595-608. [CrossRef]

- Gaillat J, Gajdos V, Launay O, Malvy D, Demoures B, Lewden L, Pinchinat S, Derrough T, Sana C, Caulin E, et al. Does monastic life predispose to the risk of Saint Anthony’s fire (herpes zoster)? Clin Infect Dis 2011;53:405-10.

- Brisson M, Gay NJ, Edmunds WJ, Andrews NJ. Exposure to varicella boosts immunity to herpes-zoster: implications for mass vaccination against chickenpox. Vaccine 2002;20:2500-7.

- Harpaz R. Do varicella vaccination programs change the epidemiology of herpes zoster? A comprehensive review, with focus on the United States. Expert Rev Vaccines 2019;18:793-811.

- Oxman MN, Levin MJ, Johnson GR, Schmader KE, Straus SE, Gelb LD, Arbeit RD, Simberkoff MS, Gershon AA, Davis LE, et al. A vaccine to prevent herpes zoster and postherpetic neuralgia in older adults. N Engl J Med 2005;352:2271-84. [CrossRef]

- Zussman J, Young L. Zoster vaccine live for the prevention of shingles in the elderly patient. Clin Interv Aging 2008;3:241-50.

- Mbinta JF, Nguyen BP, Awuni PMA, Paynter J, Simpson CR. Post-licensure zoster vaccine effectiveness against herpes zoster and postherpetic neuralgia in older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Healthy Longev 2022;3:e263-e75.

- Lal H, Cunningham AL, Godeaux O, Chlibek R, Diez-Domingo J, Hwang SJ, Levin MJ, McElhaney JE, Poder A, Puig-Barberà J, et al. Efficacy of an adjuvanted herpes zoster subunit vaccine in older adults. N Engl J Med 2015;372:2087-96.

- Cunningham AL, Lal H, Kovac M, Chlibek R, Hwang SJ, Díez-Domingo J, Godeaux O, Levin MJ, McElhaney JE, Puig-Barberà J, et al. Efficacy of the Herpes Zoster Subunit Vaccine in Adults 70 Years of Age or Older. N Engl J Med 2016;375:1019-32. [CrossRef]

- Racine É, Gilca V, Amini R, Tunis M, Ismail S, Sauvageau C. A systematic literature review of the recombinant subunit herpes zoster vaccine use in immunocompromised 18-49 year old patients. Vaccine 2020;38:6205-14.

- Huang L, Zhao T, Zhao W, Shao A, Zhao H, Ma W, Gong Y, Zeng X, Weng C, Bu L, et al. Herpes zoster mRNA vaccine induces superior vaccine immunity over licensed vaccine in mice and rhesus macaques. Emerg Microbes Infect 2024;13:2309985. [CrossRef]

- Scheifele DW, Halperin SA, Diaz-Mitoma F. Three-year follow-up of protection rates in children given varicella vaccine. Can J Infect Dis 2002;13:382-6.

- Vessey SJ, Chan CY, Kuter BJ, Kaplan KM, Waters M, Kutzler DP, Carfagno PA, Sadoff JC, Heyse JF, Matthews H, et al. Childhood vaccination against varicella: persistence of antibody, duration of protection, and vaccine efficacy. J Pediatr 2001;139:297-304. [CrossRef]

- Takayama N, Minamitani M, Takayama M. High incidence of breakthrough varicella observed in healthy Japanese children immunized with live attenuated varicella vaccine (Oka strain). Acta Paediatr Jpn 1997;39:663-8.

- Kuter B, Matthews H, Shinefield H, Black S, Dennehy P, Watson B, Reisinger K, Kim LL, Lupinacci L, Hartzel J, et al. Ten year follow-up of healthy children who received one or two injections of varicella vaccine. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2004;23:132-7. [CrossRef]

- Cohen JI. Varicella-zoster vaccine virus: evolution in action. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2007;104:7-8.

- Quinlivan ML, Gershon AA, Al Bassam MM, Steinberg SP, LaRussa P, Nichols RA, Breuer J. Natural selection for rash-forming genotypes of the varicella-zoster vaccine virus detected within immunized human hosts. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2007;104:208-12. [CrossRef]

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).